- 1Laboratório de Protozoologia, Programa de Pós-graduação em Comportamento e Biologia Animal, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora, Juiz de Fora, Brazil

- 2Instituto de Recursos Naturais Renováveis, Universidade Federal de Itajubá, Itajubá, Brazil

The gastrointestinal tracts of most herbivorous mammals are colonized by symbiotic ciliates of the subclass Trichostomatia, which form a well-supported monophyletic group, currently composed by ∼1,000 species, 129 genera, and 21 families, distributed into three orders, Entodiniomorphida, Macropodiniida, and Vestibuliferida. In recent years, trichostomatid ciliates have been playing a part in many relevant functional studies, such as those focusing in host feeding efficiency optimization and those investigating their role in the gastrointestinal methanogenesis, as many trichostomatids are known to establish endosymbiotic associations with methanogenic Archaea. However, the systematics of trichostomatids presents many inconsistencies. Here, we stress the importance of more taxonomic works, to improve classification schemes of this group of organisms, preparing the ground to proper development of such relevant applied works. We will present a historical review of the systematics of the subclass Trichostomatia highlighting taxonomic problems and inconsistencies. Further on, we will discuss possible solutions to these issues and propose future directions to leverage our comprehension about taxonomy and evolution of these symbiotic microeukaryotes.

Introduction

The gastrointestinal tracts of most herbivorous mammals are colonized by symbiotic ciliates of the subclass Trichostomatia Bütschli, 1889 (Supplementary Video S1). These play a central role for the efficient fermentative process in the host intestinal tract and also contribute to the degradation process of proteins, lipids, nitrogen compounds and carbohydrates, such as cellulose, hemicellulose and starch (Dehority, 1986; Wright, 2015). These microeukaryotes form a well-supported monophyletic group, currently composed of ∼1,000 species, 129 genera, and 21 families (Supplementary Material S1) that are distributed across three orders: Entodiniomorphida Reichenow, in Doflein & Reichenow, 1929, including species with ciliary zones restricted to tufts or bands, and infraciliatures organized as polybrachykineties, Macropodiniida Lynn, 2008 and Vestibuliferida de Puytorac et al., 1974, including ciliates all covered by cilia and with a densely ciliated vestibulum (Lynn, 2008; Cedrola et al., 2015; Gao et al., 2016). In recent years, trichostomatid ciliates have been playing a part in many relevant functional studies, such as those focusing on host feed efficiency optimization (Newbold et al., 2015) and those investigating their role in gastrointestinal methanogenesis, as many trichostomatids are known to establish endosymbiotic associations with methanogenic Archaea (Embley et al., 2003). Methanogenesis from ciliate associated methanogens may account for up to 60% of methane emissions into the Earth’s atmosphere (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC], 2019; Malmuthuge and Guan, 2017). However, the systematics of trichostomatids presents many inconsistencies. Here, we stress the importance of more taxonomic works, to improve classification schemes of this group of microorganisms. This will provide a sound basis for ciliate community structure assessment. We present a historical review of the systematics of the subclass Trichostomatia highlighting taxonomic problems and inconsistencies. We also discuss possible solutions and propose future directions to broaden our understanding of the taxonomy and evolution of these symbiotic microeukaryotes.

Past

Trichostomatid ciliates were discovered in the first half of the 19th century by Gruby and Delafond (1843). However, the authors, presented only a brief and succinct report about high densities of “animaculous” inhabiting the stomach and intestine of domestic cattle and horses. The first illustrations of trichostomatid ciliates are attributed to Colin (1854) while the author studied domestic mammals. G. Colin performed live observations of many species, possibly including members of the genera Blepharocorys Bundle, 1895, Bundleia da Cunha and Muniz, 1928, Cycloposthium Bundle, 1896, Diplodinium Schuberg, 1888 and Entodinium Stein, 1859. The first author to publish a formal taxonomic work on trichostomatid ciliates was F. Stein (1858) describing, although superficially, species of the genera Entodinium, Isotricha, and Ophryoscolex and the family Ophryoscolecidae. Following, several novel species were described from many geographic locations and from different host species. In this period, beginning with the work of F. Stein (1858) until the late 1970s, more than 400 species were described, indicating that trichostomatid ciliates may constitute a diverse group of microorganisms (Fiorentini, 1889; Bundle, 1895; Poche, 1913; Da Cunha, 1914a, b; Gassovsky, 1919; Buisson, 1923a,b,c, 1924; Crawley, 1923; Dogiel,1925a,b, 1926a,b, 1927, 1928, 1932, 1934, 1935; Fantham, 1926; Becker and Talbot, 1927; Hsiung, 1930, 1935a,b, 1936; Kofoid and MacLennan, 1930, 1932, 1933; Jirovec, 1933; Kofoid and Christenson, 1933; Kofoid, 1935; Wertheim, 1935; Fonseca, 1939; Moriggi, 1941; Sládeček, 1946; Bush and Kofoid, 1948; Lubinsky, 1957a,1958a,b; Latteur, 1966a,b, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970; Wolska, 1967b, 1968, 1969). Most of these studies were done based only on live observations and by using simple ciliatological techniques, such as hematoxylin and iodine staining methods, which were the available tools at that time. Nevertheless, many morphological characters, such as skeletal plates (Dogiel, 1923; Schulze, 1924, 1927; Dogiel and Fedorowa, 1925), contractile vacuoles (Kraschnninikow, 1929; MacLennan, 1933), concretion vacuoles (Dogiel, 1929), and paralabial organelles (Bretschneider, 1962) could be clearly characterized, allowing the inclusion of these microeukaryotes into the phylum Ciliophora, orders Entodiniomorphida and Vestibuliferida (for history of classification, see Supplementary Material S2). In this same period, the first studies appeared that proposed hypotheses on the evolution of this group of microorganisms. According to Dogiel (1947) and Lubinsky (1957a, b, c), within the family Ophryoscolecidae, subfamily Entodiniinae could be considered ancestral due to its characteristic single ciliary zone, single contractile vacuole, poorly developed caudal spines and lack of skeletal plates. The Ophryoscolecinae is considered to be the most recent group for presenting two ciliary zones, large number of vacuoles and skeletal plates, and developed caudal projections. Diplodiniinae is considered an intermediate group.

The development of silver impregnation techniques in 1930s (Bodian, 1936, 1937), which can reveal in details infraciliary and other argentophilic structures patterns, represented a great revolution in the systematics of Ciliophora (Lynn, 2008). They were initially applied to trichostomatids by Noirot-Timothée (1956a, b) where the infraciliary band patterns of Epidinium Crawley, 1923 and Ophryoscolex Stein, 1858 were described. Further studies were performed by several authors and contributed to our understanding of infraciliary band patterns in various trichostomatid ciliate species (Noirot-Timothée, 1960; Grain, 1962, 1963a,b, 1964, 1965; Batisse, 1966). However, the greatest contribution was achieved by M. Wolska in a series of seminal works (Wolska, 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966a,b, 1967a,b, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971a,b, 1978a,b,c,d, 1979, 1985, 1986), which described infraciliary band patterns and morphogenetic processes in ciliates of the families Buetschliidae Poche, 1913, Blepharocorythidae Hsiung, 1929, Spirodiniidae Strelkow, 1939, Pseudoentodiniidae Wolska, 1985 (Entodiniomorphida), Isotrichidae Bütschli, 1889 and Paraisotrichidae Da Cunha, 1915 (Vestibuliferida). As a result of these detailed investigations, a hypothesis on the evolutionary relationship within the Trichostomatia was proposed by Wolska (1971b). According to the descriptions there are several patterns of infraciliary bands in Trichostomatia in which are composed by at least one of these bands: adoral polybrachykinety, dorsal polybrachykinety, dorso-adoral polybrachykinety, kinety loop, paralabial kineties, vestibular polybrachykinety, and vestibular kineties (Supplementary Figure S1).

Ultrastructural works also impacted the systematics of trichostomatid ciliates. Bonhomme (1989), after collecting data on the ultrastructure of many Entodiniomorphina (order Entodiniomorphida) representatives, suggested that this suborder could be classified into two groups, according to their cortex ultrastructure information. The first is composed of ciliates with the cortex lacking dense longitudinal cords (genus Cycloposthium Bundle, 1895; Ophryoscolecidae Stein, 1859 and Troglodytellidae Corliss, 1979), and the second is composed of ciliates with dense longitudinal cords (genus Tripalmaria and Spirodiniidae Strelkow, 1939).

Further, based on a compilation of structural and ultrastructural data, Small and Lynn (1981) proposed Trichostomatia as a subclass of the class Litostomatea, and as a sister group of the subclass Haptoria Corliss, 1974.

Over the last 30 years, after a long period of scarce taxonomic data being produced, many taxonomic inventories of trichostomatids isolated from several mammalian host species, domestic and wild, from different geographic locations (Supplementary Table S1) started to appear in the literature, leading to the characterization of a series of novel species, including trichostomatids inhabiting the gastrointestinal tracts of Australian marsupials (Dehority, 1996; Cameron et al., 2000a,b, 2001a,b, 2002, 2003; Cameron and O’Donoghue, 2001, 2002a,b, 2002c,2003a,b,c, 2004a,b). These ciliates present several exclusive morphological features among trichostomatids. For this reason, Lynn (2008) proposed the creation of a new order to include them, Macropodiniida. This period was also characterized by the establishment of new silver impregnation techniques for trichostomatid ciliates, such as the adaptations of ammoniacal silver carbonate impregnation proposed by Ito and Imai (1998) and Rossi et al. (2016) and the adaption of Protargol’s impregnation for vestibuliferids proposed by Ito and Imai (2000). These techniques allowed the development of several studies describing the infraciliature and morphogenetic process in different trichostomatid species (Ito et al., 1997, 2001, 2002, 2006, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2014, 2017, 2018; Ito and Imai, 1998, 2003, 2005, 2006; Gürelli and Ito, 2014; Cedrola et al., 2016, Cedrola et al., 2017a, b, 2018a,b; Gürelli and Akman, 2016; Gürelli, 2018, 2019; Ito and Tokiwa, 2018), which were very important to understand the evolutionary relationships within the Trichostomatia.

A novel view on the systematics of trichostomatid ciliates emerged in the late 1990s with the advent of molecular techniques. The first molecular phylogenies (Wright and Lynn, 1997a,b,c; Wright et al., 1997) corroborated the initial morphological studies placing trichostomatids as a monophyletic group within the Litostomatea. Starting from early 2000s and with the increasing availability of 18S rRNA gene sequences of members of the subclass Trichostomatia in public repositories (Cameron et al., 2001a, 2003; Cameron and O’Donoghue, 2004b; Strüder-Kypke et al., 2007; Ito et al., 2010, 2014; Pomajbíková et al., 2010, 2013; Snelling et al., 2011; Chistyakova et al., 2014; Moon-Van der Staay et al., 2014; Grim et al., 2015; Kittelmann et al., 2015; Rossi et al., 2015; Bardele et al., 2017; Cedrola et al., 2017, 2019), the internal phylogenetic relationships within the subclass began to be elucidated. This caused a revolution in their systematics and revealed several taxonomic incongruences, mainly with respect to Entodiniomorphida and Vestibuliferida, for which the grouping based on morphological features does not seem to hold.

Present

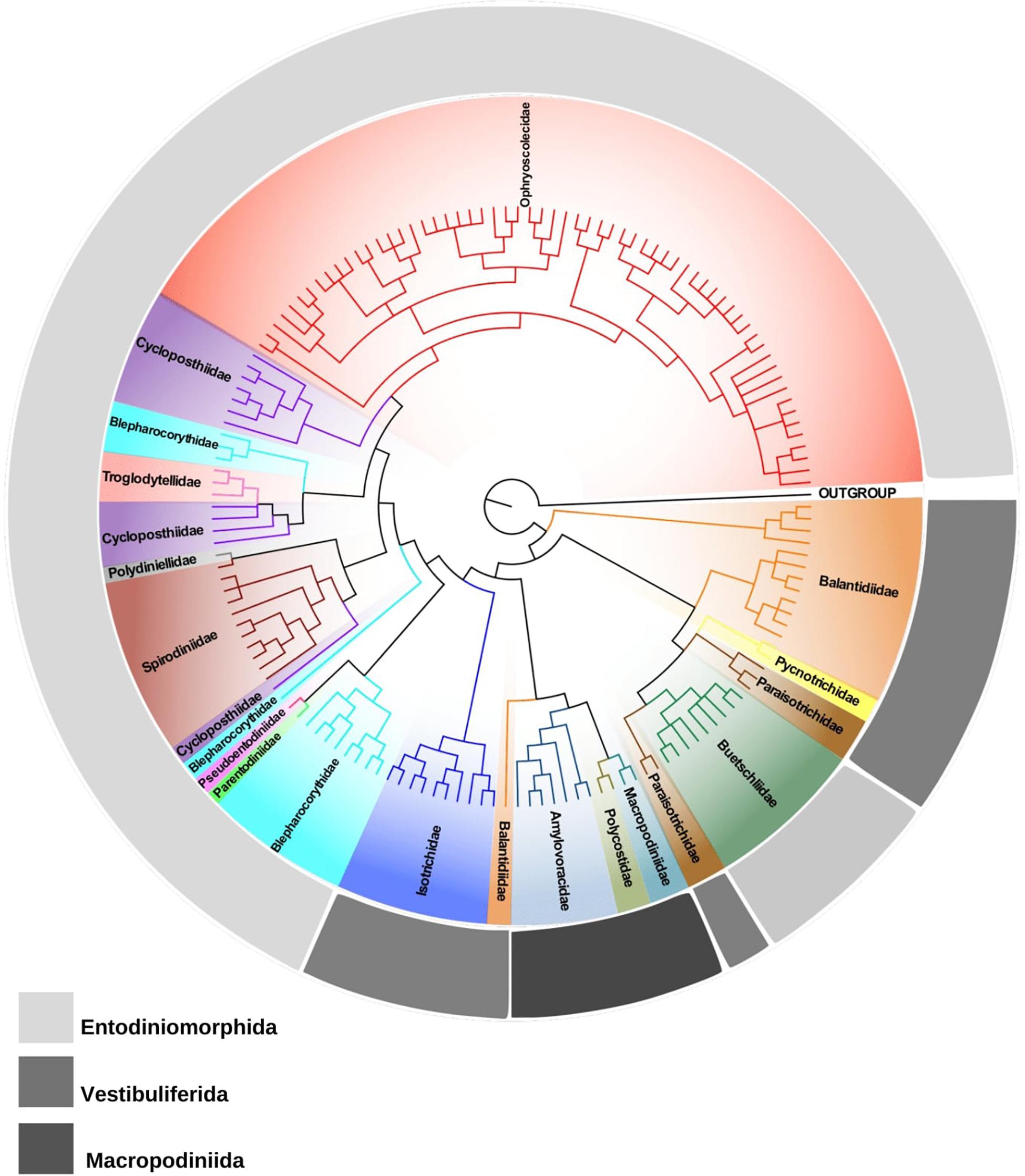

Currently, the subclass Trichostomatia consists of three major orders, Entodiniomorphida, Macropodiniida, and Vestibuliferida. Macropodiniida is the only group for which multidisciplinary taxonomic approaches were applied (Cameron and O’Donoghue, 2001, 2002a,b,c, 2003a,b,c, 2004a,b; Cameron et al., 2000a,b,2001a,b, 2002, 2003). Their representatives are distributed in three monophyletic families all with well-supported internal nodes (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S2). However, most of the species diversity of Trichostomatia occurs within the Entodiniomorphida and Vestibuliferida, which are extremely neglected groups concerning taxonomic studies. According to 18S rRNA gene reconstructions (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S2; Ito et al., 2014; Kittelmann et al., 2015), the order Entodiniomorphida is not monophyletic, emerging in the tree as two independent clades, one containing representatives of the families Blepharocorythidae Hsiung, 1929, Parentodiniidae Ito et al., 2002, Pseudoentodiniidae Wolska, 1986, Cycloposthiidae Poche, 1913, Spirodiniidae Strelkow, 1939, Polydiniellidae Corliss, 1960, Troglodytellidae Corliss, 1979, and Ophrysocolecidae Stein, 1859; and another containing members of the family Buetschliidae Poche, 1913. Moreover, many of these families do not constitute natural groups, such as Blepharocorythidae, Cycloposthiidae, and Spirodiniidae; and for those that are monophyletic, such as Ophryoscolecidae, the internal branching is poorly supported, as detected in previous works (Ito et al., 2014; Kittelmann et al., 2015; Rossi et al., 2015; Cedrola et al., 2017). Many inconsistencies can also be observed in the order Vestibuliferida with representatives distributed in three distinct clades (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S2; Ito et al., 2014; Kittelmann et al., 2015), in which the families Balantididae and Paraisotrichidae do not constitute natural groups. Moreover, 18S rRNA gene sequences are only available from representatives of 16 out of the 21 currently recognized families of Trichostomatia. The families with no molecular data are: Gilchristinidae (Ito et al., 2014), Rhinozetidae Van Hoven et al., 1988, Telamonididae Latteur and Dufey, 1967 (Entodiniomorphida), Protocaviellidae Grain and Corliss, 1979, Protohallidae Cunha and Muniz, 1927 (Vestibuliferida). Still, many of the existing families of which molecular data are available, such as Polydiniellidae Corliss, 1960, Troglodytellidae Corliss, 1979 (Entodiniomorphida) and Pycnotrichidae Poche, 1913 (Vestibuliferida) have only one representative with its 18S rRNA gene sequenced, limiting the power of phylogenetic reconstructions within the whole group. The scarcity and absence of consistent morphological data from many trichostomatid groups is also of concerns, for example, there are no structural (infraciliary pattern and morphogenesis) and ultrastructural data described for many cycloposthiids, troglodytelids, and spirodinids, which makes it impossible to establish homology hypotheses on trichostomatids. Moreover, the lack of detailed morphological data contributes to taxonomic inconsistencies and hinders the development of novel classifications schemes that reflect evolutionary divergences.

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree of trichostomatid ciliates (Ciliophora, Litostomatea, and Trichostomatia) estimated by Bayesian Inference and based on 18S rRNA gene data. Spathidium papilliferum was chosen as out group.

Future

Despite the great advances obtained after implementing silver staining, ultrastructural and molecular methods, it is clear that huge gaps are still preventing a cohesive systematic scheme of Trichostomatia, especially when we compare the existing data with other Ciliophora groups (Warren et al., 2017). In the forthcoming years, we need to invest more in detailed descriptions and redescriptions of infraciliary band patterns and morphogenesis, on 18S rRNA gene sequencing, and in depth ultrastructure characterizations. Using these methods, we need to study trichostomatids from a wide variety of hosts especially in so far neglected geographical regions such as, e.g., neotropical areas, with emphasis on Entodiniomorphida and Vestibuliferida. We should further expand this work to trichostomatid families such as the Protocaviellidae and Protohallidae from domestic and wild rodents and Gilchristinidae, Rhinozetidae, and Telamonididae from elephants, rhinos and wild pigs, respectively. Moreover, improvements to trichostomatid cultivation techniques, which are still poorly developed (Williams and Coleman, 1992; Dehority and Wright, 2014; Newbold et al., 2015; Belzecki et al., 2016), would be of great importance to obtain suitable samples for morphology and molecular characterization approaches. Collectively, this information will contribute to develop more robust phylogenetic hypotheses, to elaborate taxonomic reformulations, contributing to elucidate the many taxonomic incongruences presented above and to establish new classification schemes that reflect evolutionary divergences within Trichostomatia.

Apart from 18S rRNA genes, it is time to obtain data on other informative loci from pure/axenic cultures, such as the internal transcribed spacer region and 28S ribosomal RNA genes, to further improve our understanding of the phylogenetic relationships within the Litostomatea (Rajter and Vd’ačný, 2017). In addition, it is possible to identify new macronuclear regions, using genomic information of Trichostomatia representatives (Park et al., 2018), and to obtain hydrogenosomal sequences, such as those from 16S and Fe-Hydrogenase. Also, it is possible to use the next generation sequencing techniques to perform phylogenomic reconstruction, as done for other Ciliophora groups within the last decade (Feng et al., 2015; Gentekaki et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2019). This data could be used in macro-evolutionary approaches to reveal divergence times and the mode of evolution in trichostomatid ciliates. The timescale and evolutionary dynamics of these symbiotic ciliates are yet to be determined (Newbold et al., 2015). Molecular dating studies are restricted to Wright and Lynn (1997c) and Vd’ačný (2015, 2018), which employed different molecular dating methods, taxon sampling and calibration data, using mostly the fossil record of hosts and the posterior ages estimated from previous studies as calibration priors for ciliates time tree. Baele et al. (2006) provided evidence for the presence of numerous heterotachous sites (sites in which its substitution rates can vary with time) within the 18S rRNA gene of ciliates, which may result in the introduction of bias. Thus, further improvements to the calculation and resolution of trichostomatid phylogenies are needed through the use of evolutionary models, such as, for example, the mixture of branch lengths (MBL) (Zhou et al., 2007).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for the phylogenetic analyses are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

FC, PF, and MD collected the data. FC, MS, and RD participated in the conception of the study. FC, MS, and MR participated in the manuscript writing. FC, MR, and PF prepared the figures and supplementary material. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) (403336/2016-3), and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG). CNPq provided the research grant to MD and RD (Bolsa de Produtividade PQ), CAPES to MS and PF, and FAPEMIG to FC.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02967/full#supplementary-material

FIGURE S1 | Oral infraciliary bands pattern of Trichostomatid ciliates. A–D. Order Vestibuliferida. A, Isotrichidae; B, Paraisotrichidae; C, Protocaviellidae; D, Protohallidae; E–L, Order Entodiniomorphida; E, Buetschliidae; F, Blepharocorythidae; G, Cycloposthiidae; H, Gichristinidae; I, Ophryoscolecidae; J, Parentodiniidae; K, Pseudoentodiniidae; L, Spirodiniidae; M–O, Order Macropodiniida; M, Amylovoracidae; N, Polycostidae; O, Macropodiniidae; AP, adoral polybrachykinety; CB, cytopharyngeal basket; DAP, dorso-adoral polybrachykinety; PVP, perivestibular polybrachykinety, and VK, vestibular kineties.

FIGURE S2 | Phylogenetic tree of trichostomatid ciliates (Ciliophora, Litostomatea, and Trichostomatia) based on 18S rRNA gene data. Spathidium papilliferum was chosen as out group. The black dots in the nodes indicate bootstrap (ML) or posterior probability (BI) values >80/0.8. The scale bar corresponds to four substitutions per 100 nucleotides positions.

TABLE S1 | Hosts where Trichostomatia ciliates were registered.

MATERIAL S1 | Trichostomatid families and genera.

MATERIAL S2 | History of classification of subclass Trichostomatia.

VIDEO S1 | Trichostomatid domestic cattle rumen ciliates under live observation.

References

Baele, G., Raes, J., Van der Peer, Y., and Vansteelandt, S. (2006). An improved statistical method for detecting heterotachy in nucleotide sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 1397–1405. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl006

Bardele, C. F., Schultheib, S., Wright, A.-D. G., Dominguez-Bello, M. G., and Obispo, N. E. (2017). Aviistricha hoazini n. gen., n. sp., the morphology and molecular phylogeny of an anaerobic ciliate from the crop of the hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin), the cow among the birds. Protist 168, 335–351. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2017.02.002

Batisse, A. (1966). Quelques infusoires holotriches parasites du coecum de l’hydrochaire (Hydrocheirus capybara, L.). Protist 2, 39–52.

Becker, E. R., and Talbot, M. (1927). The protozoan fauna of the rumen and reticulum of American cattle. Iowa State Coll. J. Sci. 1, 345–371.

Belzecki, G., Miltko, R., Michalowski, T., and McEwan, N. R. (2016). Methods for the cultivation of ciliated protozoa from the large intestine of horses. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 363, 1–4. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnv233

Bodian, D. (1936). The new ethod for staining nerve fibers and nerve endings in mounted paraffin sections. Anat. Rec. 69, 153–162.

Bodian, D. (1937). The staining of paraffin sections of nervous tissues with activated protargol. The role of fixatives. Anat. Rec. 70, 153–162. doi: 10.1002/ar.1090690205

Bonhomme, A. (1989). Etude ultrastructurale de Troglodytella gorillae, cilié de l’intestin des gorilles. Eur. J. Protistol. 24, 225–237. doi: 10.1016/s0932-4739(89)80059-8

Bretschneider, L. H. (1962). Das Paralabialorgan der Ophryoscoleciden. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Amsterdam 65, 423–452.

Buisson, J. (1923a). Infusoires nouveux parasites d’antilopes africaines. C. R. Séances Soc. Biol. 89, 1217–1219.

Buisson, J. (1923b). Les Infusoires Ciliés du Tube Digestif de L’homme et des Mammifères. Ph. D. Thèse. Paris Le Gall: Paris.

Buisson, J. (1923c). Sur quelques infusoires nouveux ou peu connus parasites de mammifères. Ann. Par. Hum. Comp. 1, 209–246. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2019003

Buisson, J. (1924). Quelques infusoires parasites d’antilopes africaines. Ann. Par. Hum. Comp. 2, 155–160. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1924022155

Bush, M., and Kofoid, C. A. (1948). Ciliates from the Sierra Nevada bighorn (Ovis canadensis sierra Grinnell). Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 53, 237–261.

Cameron, S., O’Donoghue, P., and Adlard, R. (2000a). First record of Cycloposthium edentatum Strelkow, 1928 from the black-striped wallaby, Macropus dorsalis. Parasitol. Res. 86, 158–162. doi: 10.1007/s004360050025

Cameron, S. L., O’donoghue, P. J., and Adlard, R. D. (2000b). Novel isotrichid ciliates endosymbiotic in Australian macropodid marsupials. Syst. Parasitol. 46, 45–57. doi: 10.1023/a:1006208802110

Cameron, S. L., and O’Donoghue, P. J. (2001). Stomatogenesis in the ciliate genus Macropodinium Dehority, 1996 (Litostomatea: Macropodiniidae). Eur. J. Protistol. 37, 199–206. doi: 10.1078/0932-4739-00819

Cameron, S. L., and O’Donoghue, P. J. (2002a). The ultrastructure of Amylovorax dehorityi comb. nov. and erection of the Amylovoracidae fam. nov. (Ciliophora: Trichostomatia). Eur. J. Protistol. 38, 29–44. doi: 10.1078/0932-4739-00841

Cameron, S. L., and O’Donoghue, P. J. (2002b). The ultrastructure of Macropodinium moiri and revised diagnosis of the Macropodiniidae (Litostomatea: Trichostomatia). Eur. J. Protistol. 38, 179–194. doi: 10.1078/0932-4739-00861

Cameron, S. L., and O’Donoghue, P. J. (2002c). Trichostome ciliates from Australian marsupials. I. Bandia gen. nov. (Litostomatea: Amylovoracidae). Eur. J. Protistol. 38, 405–429. doi: 10.1078/0932-4739-00889

Cameron, S. L., and O’Donoghue, P. J. (2003a). Trichostome ciliates from Australian marsupials. II. Polycosta gen. nov. (Litostomatea: Polycostidae fam. nov.). Eur. J. Protistol. 39, 83–99. doi: 10.1078/0932-4739-00890

Cameron, S. L., and O’Donoghue, P. J. (2003b). Trichostome ciliates from Australian marsupials. III. Megavestibulum gen. nov.(Litostomatea: Macropodiniidae). Eur. J. Protistol. 39, 123–137. doi: 10.1078/0932-4739-00891

Cameron, S. L., and O’Donoghue, P. J. (2003c). Trichostome ciliates from Australian marsupials. IV. Distribution of the ciliate fauna. Eur. J. Protistol. 39, 139–147. doi: 10.1078/0932-4739-00892

Cameron, S. L., and O’Donoghue, P. J. (2004a). Morphometric and cladistic analyses of the phylogeny of Macropodinium (Ciliophora: Litostomatea: Macropodiniidae). Acta Protozool. 43, 43–53.

Cameron, S. L., and O’Donoghue, P. J. (2004b). Phylogeny and biogeography of the “Australian” trichostomes (Ciliophora: Litostomata). Protist 155, 215–235. doi: 10.1078/143446104774199600

Cameron, S. L., Adlard, R. D., and O’Donoghue, P. J. (2001a). Evidence for an independent radiation of endosymbiotic litostome ciliates within Australian marsupial herbivore. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 20, 302–310. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2001.0986

Cameron, S. L., O’donoghue, P. J., and Adlard, R. D. (2001b). Four new species of Macropodinium (Ciliophora: Litostomatea) from Australian wallabies and pademelons. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 48, 542–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2001.tb00190.x

Cameron, S. L., O’Donoghue, P. J., and Adlard, R. D. (2002). Species diversity within Macropodinium (Litostomatea: Trichostomatia): endosymbiotic ciliates from Australian macropodid marsupials. Mem. Queensl. Mus. 48, 49–69.

Cameron, S. L., Wright, A. D. G., and O’Donoghue, P. J. (2003). An expanded phylogeny of the Entodiniomorphida (Ciliophora: Litostomatea). Acta Protozool. 42, 1–6.

Cedrola, F., Dias, R. J. P., Martinele, I., and D’Agosto, M. (2017a). Description of Diploplastron dehorityi sp. nov. (Entodiniomorphida, Ophryoscolecidae), a new rumen ciliate from Brazilian sheep. Zootaxa 4258, 581–585. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4258.6.8

Cedrola, F., Dias, R. J. P., Martinele, I., and D’Agosto, M. (2017b). Polymorphism and inconsistencies in the taxonomy of Diplodinium anisacanthum da Cunha, 1914 (Ciliophora, Entodiniomorphida, Ophryoscolecidae) and taxonomic notes on the genus Diplodinium. Zootaxa 4306, 249–260.

Cedrola, F., Fregulia, P., D’Agosto, M., and Dias, R. J. P. (2018a). Intestinal ciliates of Brazilian capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris L.). Acta Protozool. 57, 61–67.

Cedrola, F., Rossi, M. F., Martinele, I., D’Agosto, M., and Dias, R. J. P. (2018b). Morphology and description of infraciliary bands pattern in four Metadinium Awerinzew and Mutafowa, 1914 species (Ciliophora, Entodiniomorphida, Ophryoscolecidae) with taxonomic notes on the genus. Zootaxa 4500, 574–580. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4500.4.6

Cedrola, F., Martinele, I., Dias, R. J. P., and D’Agosto, M. (2016). Rumen ciliates in Brazilian sheep (Ovis aries) and redescription of Entodinium contractum (Ciliophora, Entodiniomorphida, Ophryoscolecidae). Zootaxa 4088, 292–300. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4088.2.10

Cedrola, F., Rossi, M. F., Dias, R. J. P., Martinele, I., and D’Agosto, M. (2015). Methods for taxonomic study of rumen ciliates (Alveolata, Ciliophora): a brief review. Zool. Sci. 32, 8–15. doi: 10.2108/zs140125

Cedrola, F., Senra, M. V. X., D’Agosto, M., and Dias, R. J. P. (2017). Phylogenetic analyses support validity of genus Eodnium. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 64, 242–247. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12355

Cedrola, F., Senra, M. V. X., D’Agosto, M., and Dias, R. J. P. (2019). Helmet-shaped body of entodiniomorphid ciliates (Ciliophora, Entodiniomorphida), a synapomorphy or a homoplasy? J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 0, 1–4. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12749

Chistyakova, L. V., Kostygov, A. Y., Kornilova, O. A., and Yurchenko, V. (2014). Reisolation and description of Balantidium duodeni Stein, 1867 (Litostomatea, Trichostomatia). Parasitol. Res. 113, 4207–4215. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-4096-1

Colin, G. (1854). Traité de Physiologie Comparée des Animaux; Considérée dans ses Rapports Avec les Sciences Naturelles, la Médecine, la Zootechnie, et L’économie Rurale. Paris: Baillière.

Crawley, H. (1923). Evolution in the family Ophryoscolecidae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 75, 393–412.

Da Cunha, A. M. (1914a). Sobre os ciliados do estomago dos ruminantes no Brasil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 6, 58–69.

Da Cunha, A. M. (1914b). Sobre os ciliados intestinaes dos mammiferos. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 7, 139–145. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761915000200001

Dehority, B. A. (1986). Protozoa of the digestive tract of herbivorous mammals. Insect Sci. Appl. 7, 279–296. doi: 10.1017/s1742758400009346

Dehority, B. A. (1996). A new family of Entodiniomorph protozoa from the marsupial forestomach, with descriptions of a new genus and five new species. J. Protozool. 4, 285–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1996.tb03991.x

Dehority, B. A., and Wright, A.-D. (2014). Studies on the in vitro cultivation of ciliate protozoa from the kagaroo forestomach. Eur. J. Protistol. 50, 395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2014.04.001

Dogiel, V. A. (1923). Cellulose ais Bestandteil des Skeletts bei einigen infusioren. Biol. Zent. Bl. 43, 289–291.

Dogiel, V. A. (1925a). Neue parasitische infusorien aus dem Magen des Renntiers (Rangifer tarandus). Rusk Arkh Protist. 4, 43–65.

Dogiel, V. A. (1925b). Nouveaux infusoires de la famille des ophryoscolécidés parasites d’antilopes africaines. Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 15, 116–142. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1925032116

Dogiel, V. A. (1926a). Sur quelques infusoires nuveaux habitant l’estomac du dromedaire (Camelus dromedarius). Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 4, 241–271. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1926043241

Dogiel, V. A. (1926b). Une nouvelle espèce du genre Blepharocorys, B. bovis n. sp. habitant l’estomac do boeuf. Ann. Parasitol. Hum. Comp. 4, 61–64. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1926041061

Dogiel, V. A. (1928). La faune d’infusoires inhabitant l’estomac du buffle et du dromedaire. Ann. Parasitol. 6, 323–338. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1928063323

Dogiel, V. A. (1929). Die sog. “Konkrementenvakuole” der infusoiren al eine statocyste 11 betrachtet. Arch. Protistenk. 63, 319–348.

Dogiel, V. A. (1932). Bueschreibung einiger neuer vertreter der familie Ophryoscolecidae aus afrikanishen Antilopen nebst. Revision der infusioren fauna afrikanischer wiederkäuer. Arch. Protistenkd. 77, 92–107.

Dogiel, V. A. (1934). Angaben ber die Ophryoscolecidae des wildchafs aus kamtschatka des elches und des yaks, nebst deren zoogeographischen verwertung. Arch. Protistenkd. 82, 144–148.

Dogiel, V. A. (1935). Eine notiz ber die infusioren des renntiermagens. Trans. Arct. Inst. 24, 144–148.

Dogiel, V. A. (1947). The phylogeny of the stomach-infusorians of ruminants in the light of palaeontological and parasitological data. Q. J. Microsc. Sci. 88, 337–342.

Dogiel, V. A., and Fedorowa, T. (1925). Uber den Bau und die Funktion des inneren Skeletts der Ophryoscolesciden. Zool. Anz. 62, 97–107.

Embley, T. M., van der Giezen, M., Horner, D. S., Dyal, P. L., Bell, S., and Foster, P. G. (2003). Hydrogenosomes, mitochondria and early eukaryotic evolution. Life 55, 387–395. doi: 10.1080/15216540310001592834

Feng, J. M., Jiang, C. Q., Warren, A., Tian, M., Cheng, J., Liu, G. L., et al. (2015). Phylogenomic analyses reveal subclass Scuticociliata as the sister group of subclass Hymenostomatia within class Olygohymenophorea. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 90, 104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2015.05.007

Fonseca, F. (1939). Ciliado gigante, Muniziella cunhai, gen. n., sp. n., parasite de Hydrochoerus capybara (Holotricha, Pycnothrichidae). Mem. Inst. Butantan. 12, 165–173.

Gao, F., Warren, A., Zhang, Q., Gong, J., Miao, M., Sun, P., et al. (2016). The all-data-based evolutionary hypothesis of ciliated protists with a revised classification of the phylum Ciliophora (Eukaryota, Alveolata). Sci. Rep. 6:24874. doi: 10.1038/srep24874

Gassovsky, G. (1919). On the microfauna of the intestine of the horse. Travaux de la Soc. des Naturalistes de Pétrograd. 48, 20–37.

Gentekaki, E., Kolisko, M., Gong, Y., and Lynn, D. (2017). Phylogenomics solves a long-standing evolutionary puzzle in the ciliate world: the subclass Peritrichia is monophyletic. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 106, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.09.016

Grain, J. (1962). L’infraciliature d’Isotricha intestinalis Stein, cilié trichostome de la panse des ruminants. C. R. Acad. Sci. 254, 2221–2223.

Grain, J. (1963a). L’infraciliature d’Isotricha prostoma Stein, cilié trichostome de la panse des ruminants. C. R. Acad. Sci. 256, 3885–3888.

Grain, J. (1963b). Sur Dasytricha ruminantium Schuberg, cilié de la panse des ruminants. Arch. Zool. Exp. Gen. 102, 183–188.

Grain, J. (1964). La stomatogenèse chez les ciliés trichostomes Isotricha intestinalis et Paraisotricha colpoidea. Arch. Zool. Exp. Gen. 104, 85–93.

Grain, J. (1965). Premières observtions sur les systèmes fibrillaires chez quelques ciliés des ruminants et des equidés. Arch. Zool. Exp. Gen. 105, 185–190.

Grim, N., Jirku-Pomajbíková, J., and Ponce-Gordo, F. (2015). Light microscopic morphometrics, ultrastructure, and molecular phylogeny of the putative pycnotrichid ciliate, Buxtonella sulcata. Eur. J. Protistol. 51, 425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2015.06.003

Gruby, D., and Delafond, O. (1843). Recherches sur des animalcules se développant en grand nombre dans l’estomac et dans l’intestin, pendant la digestion des animaux herbivores et carnivores. C. R. Acad. Sci. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. 17, 1304–1308.

Gürelli, G. (2018). Infraciliature of Eudiplodinium maggi, E. dolobum, and E. rostratum. Comm. J. Biol. 2, 16–18.

Gürelli, G. (2019). New entodiniomorphid ciliates, Buetschlia minuta n. sp., B. cirrata n. sp., Charonina elephanti n. sp., from Asian elephants of Turkey. Zootaxa 4545, 419–433. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4545.3.6

Gürelli, G., and Akman, F. T. B. (2016). Rumen ciliate biota of domestic cattle (Bos taurus taurus) in Stambul, Turkey and infraciliature of Metadinium medium (Entodiniomorphida, Ophryoscolecidae). Acta Protozool. 53, 173–182. doi: 10.5152/tpd.2012.55

Gürelli, G., and Ito, A. (2014). Intestinal ciliated protozoa of the Asian elephant Elaphas maximus Linnaeus, 1758 with the description of Triplumaria izmirae n. sp. Eur. J. Protistol. 50, 25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2013.10.002

Hsiung, T.-S. (1930). A monograph on the protozoa of the large intestine of the horse. Iowa State Coll. J. Sci. 4, 359–423.

Hsiung, T.-S. (1935a). Notes on the known species of Triadinium with the description of a new species. Bull. Fan Mem. Inst. Biol. 6, 21–32.

Hsiung, T.-S. (1935b). On some new species from the mule, with the description of a new genus. Bull. Fan Mem. Inst. Biol. 6, 81–94.

Hsiung, T.-S. (1936). A survey of the ciliates of Chinese equines. Bull. Fan Mem. Inst. Biol. 6, 289–304.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC] (2019). Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Geneva: IPCC.

Ito, A., Arai, N., Tsutsumi, Y., and Imai, S. (1997). Ciliate protozoa in the rumen of sassaby antelope, Damaliscus lunatus lunatus, including the description of a new species and form. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 44, 586–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1997.tb05964.x

Ito, A., Eckardt, W., Stoinski, T. S., Gillespie, T. R., and Tokiwa, T. (2017). Gorilloflasca africana n. g., n. sp., (Entodiniomorphida) from wild habituated Virunga mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) in Rwanda. Eur. J. Protistol. 60, 68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2017.06.002

Ito, A., Eckardt, W., Stoinski, T. S., Gillespie, T. R., and Tokiwa, T. (2018). Three new Troglodytella and a new Gorilloflasca ciliates (Entodiniomorphida) from mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei) in Rwanda. Eur. J. Protistol. 65, 42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2018.05.002

Ito, A., Honma, H., Gürelli, G., Göçmen, B., Mishima, T., Nakai, Y., et al. (2010). Redescription of Triplumaria selenica Latteur et al., 1970 (Ciliophora, Entodiniomorphida) and its phylogenetic position based on the infraciliary bands and 18SSU rRNA gene sequence. Eur. J. Protistol. 46, 180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2010.01.005

Ito, A., and Imai, S. (1998). Infraciliary bands in the rumen Ophryoscolecid ciliate Ostracodinium gracile (Dogiel, 1925), observed by light microscopy. J. Eukariot. Microbiol. 45, 628–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1998.tb04559.x

Ito, A., and Imai, S. (2000). Ciliates from the cecum of capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) in Bolivia 1. The families Hydrochoerellidae n. fam., Protohallidae, and Pycnotrichidae. Eur. J. Protistol. 36, 53–84. doi: 10.1016/s0932-4739(00)80023-1

Ito, A., and Imai, S. (2003). Light microscopical observation of infraciliary bands of Eodinium posterovesiculatum in comparison with Entodinium bursa and Diplodinium dentatum. J. Eukariot. Microbiol. 50, 34–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2003.tb00103.x

Ito, A., and Imai, S. (2005). Infraciliature and morphogenesis in three rumen Diplodinium ciliates, Diplodinium polygonale, Diplodinium leche, and Diplodinium nanum, observed by light microscopy. J. Eukariot. Microbiol. 52, 44–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.3312r.x

Ito, A., and Imai, S. (2006). Infraciliary band pattern of rumen ophryoscolecid ciliates. Endocytobiosis Cell Res. 17, 103–110.

Ito, A., Mishima, T., Nataami, K., Ike, K., and Imai, S. (2011). Infraciliature of eight Triplumaria species (Ciliophora, Entodiniomorphida) from Asian elephants with the description of six new species. Eur. J. Protistol. 47, 256–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2011.06.002

Ito, A., Ishihara, M., and Imai, S. (2014). Bozasella gracilis n. sp. (Ciliophora, Entodiniomorphida) from Asian elephant and phylogenetic analysis of entodiniomorphids and vestibuliferids. Eur. J. Protistol. 50, 134–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2014.01.003

Ito, A., Miyazaki, Y., and Imai, S. (2001). Light microscopic observations of infraciliature and morphogenesis in six species of rumen Ostracodinium ciliates. J. Eukariot. Microbiol. 48, 440–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2001.tb00177.x

Ito, A., Miyazaki, Y., and Imai, S. (2002). Descriptions of new Parentodinium ciliates in the family Parentodiniidae n. fam. From Hippopotamus amphibius in comparison with some entodiniomorphs from horses and cattle. Eur. J. Protistol. 37, 405–426. doi: 10.1078/0932-4739-00828

Ito, A., and Tokiwa, T. (2018). Infraciliature of Opisthotrichum janus, Epidinium ecaudatum, and Ophryoscolex purkynjei (Ciliophora, Entodiniomorphida). Eur. J. Protistol. 62, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2017.10.001

Ito, A., Van Hoven, W., Miyazaki, Y., and Imai, S. (2006). New entodiniomorphid ciliates from the intestine of the wild African white rhinoceros belong to a new family, the Gilchristidae. Eur. J. Protistol. 42, 297–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2006.07.006

Ito, A., Van Hoven, W., Miyazaki, Y., and Imai, S. (2008). Two new entodiniomorphid Triplumaria ciliates from the intestine of the wild African white rhinoceros. Eur. J. Protistol. 44, 149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2007.11.003

Jiang, C. Q., Wang, G. Y., Xiong, J., Yang, W. T., Sun, Z. Y., Feng, J. M., et al. (2019). Insights into the origin and evolution of Peritrichia (Oligohymenophorea, Ciliophora) based on analyses of morphology and phylogenomics. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 132, 25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2018.11.018

Jirovec, O. (1933). Beobachtungen über die fauna des rinderpansen. Z. Parasitenkd. 5, 584–591. doi: 10.1007/bf02121364

Kittelmann, S., Devente, S. R., Kirk, M. R., Seedorf, H., Dehority, B. A., and Janssen, P. H. (2015). Phylogeny of intestinal ciliates, including Charonina ventriculi, and comparison of microscopy and 18S rRNA gene pyrosequencing for rumen ciliate community structure analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 2433–2444. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03697-14

Kofoid, C. A. (1935). Two remarkable ciliate protozoa from the caecum of the Indian elephant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 21, 501–506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.21.7.501

Kofoid, C. A., and Christenson, J. F. (1933). Ciliates from Bos-gaurus H. Smith. Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 39, 341–391.

Kofoid, C. A., and MacLennan, R. F. (1930). Ciliates from Bos indicus Linn. I. The genus Entodinium. Stein. Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 33, 471–544.

Kofoid, C. A., and MacLennan, R. F. (1932). Ciliates from Bos indicus Linn. II. A revision of Diplodinium Schuberg. Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 37, 53–152.

Kofoid, C. A., and MacLennan, R. F. (1933). Ciliates from Bos indicus Linn. 3. Epidinium Crawley, Epiplastron gen. nov., and Ophryoscolex Stein. Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 39, 1–34.

Kraschnninikow, S. (1929). Zur frage des lipoidenexkretionsapparats einiger infusorienarten aus der familie Ophryoscolecidae. Z. F. Zellforsch. Mikr. Anat. 8, 470–483. doi: 10.1007/bf00587501

Latteur, B. (1966a). Diplodinium archon n. sp. Ciliate Ophryoscolecidae du rumen de l’antelope Tragelaphus scriptus Pallas. Ann. Soc. Belge Med. Trop. 46, 727–740.

Latteur, B. (1966b). Epidinium dactylodonta n. sp. Ciliate Ophryoscolecidae du rumen de l’antelope Tragelaphus scriptus Pallas. Bull. Inst. R. Sci. Nat. Bel. 42, 1–27.

Latteur, B. (1967). Helicozoster indicus n. gen., n. sp., ciliate holotriche du caecum de l’elephant des indes. Acta Zool. Pat. Ant. 43, 93–106.

Latteur, B. (1968). Revision systematique de la famille des Ophryoscolecidae Stein, 1858: sous-Famille des Entodiniinae Lubinsky, 1957. Genre Entodinium Stein, 1858. Ann. Soc. R. Zool. de Belgique 98, 1–41.

Latteur, B. (1969). Revision systematique de la famille des Ophryoscolecidae Stein, 1858: sous-famille des Epidiniinae Lubinsky, 1957. Genre Epidinium Stein, 1958. Ann. Soc. R. Zool. de Belgique 99, 3–25.

Latteur, B. (1970). Revision systematique de la famille des Ophryoscolecidae Stein, 1858: sous-famille des Diplodiniinae Lubinsky, 1957. Genre Diplodinium (Schuberg, 1888). sensu novo. Ann. Soc.R. Zool. de Belgique 100, 275–312.

Lubinsky, G. (1957a). Studies on the evolution of the Ophryoscolecidae (Ciliata: Oligotricha) I. A new species of Entodinium with “caudatum”, “loboso-spinosum”, and “dubardi” forms, and some evolutionary trends in the genus Entodinium. Can. J. Zool. 35, 111–133. doi: 10.1139/z57-007

Lubinsky, G. (1957b). Studies on the evolution of the Ophryoscolecidae (Ciliata: Oligotricha) II. On the origin of the higher Ophryoscolecidae. Can. J. Zool. 35, 135–140. doi: 10.1139/z57-008

Lubinsky, G. (1957c). Studies on the evolution of the Ophryoscolecidae (Ciliata: Oligotricha) III. Phylogeny of the Ophryoscolecidae based on their comparative morphology. Can. J. Zool. 35, 141–159. doi: 10.1139/z57-009

Lubinsky, G. (1958a). Ophryoscolecidae (Ciliata: Entodiniomorphida) of reindeer (Rangifer tarandus L.) from the Canadian Arctic. I. Entodiniinae. Can. J. Zool. 36, 819–835. doi: 10.1139/z58-068

Lubinsky, G. (1958b). Ophryoscolecidae (Ciliata: Entodiniomorphida) of reindeer (Rangifer tarandus L.) from the Canadian Arctic. II. Diplodiniinae. Can. J. Zool. 36, 937–959. doi: 10.1139/z58-080

Lynn, D. H. (2008). The Ciliated Protozoa. Characterization, Classification, and Guide to the Literature. Dordrecht: Springer.

MacLennan, R. F. (1933). The pulsatory cycle of the contractile vacuoles in the Ophryoscolecidae, ciliates from the stomach of cattle. Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 39, 205–249.

Malmuthuge, N., and Guan, L. L. (2017). Understand the gut microbiome of dairy calves: opportunities to improve early-life gut health. J. Dairy Sci. 100, 5996–6005. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-12239

Moon-Van der Staay, S. Y., Van Der Staay, G. W. M., Michalowski, T., Jouany, J.-P., Pristas, P., Javorsky, P., et al. (2014). The symbiotic intestinal ciliates and the evolution of their hosts. Eur. J. Protistol. 50, 166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2014.01.004

Newbold, C. J., de la Fuente, G., Belanche, A., Ramos-Morales, E., and McEwan, N. R. (2015). The role of ciliate protozoa in the rumen. Front. Microbiol. 6:1313. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01313

Noirot-Timothée, C. (1956a). Les structures infraciliaires chez les Ophryoscolecidae. I. Étude du genre Epidinium Crawley. C. R. Acad. Sci. 242, 1076–1078.

Noirot-Timothée, C. (1956b). Les structures infraciliaires chez les Ophryoscolecidae. II. Étude du genre Ophryoscolex Stein. Ibid. 242, 2865–2867.

Noirot-Timothée, C. (1960). Etude d’une famille de ciliés: les Ophryoscolecidae. Structures et ultrastructures. Ann. Sci. Nat. Zool. Biol. An. 2, 527–718.

Park, T., Wijeratne, S., Meulia, T., Firkins, J., and Yu, Z. (2018). Draft macronuclear genome sequence of the ruminal ciliate Entodinium caudatum. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 7, 1–2. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00826-18

Pomajbíková, K., Oborník, M., Hórak, A., Petrzelková, K. L., Grim, J. N., and Levecke, B. (2013). Novel insights into the genetic diversity of Balantidium and Balantidium-like cyst-forming ciliates. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7:3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002140

Pomajbíková, K., Petrzelkova, K. J., Profousova, I., and Modry, D. (2010). Discrepancies in the occurrence of Balantidium coli between wild and captive African great apes. J. Parasitol. 96, 1139–1144. doi: 10.1645/GE-2433.1

Rajter, L., and Vd’ačný, P. (2017). Constrains on phylogenetic interrelationships among four free-living Litostomatean lineages inferred from 18S rRNA gene-ITS region sequences and secondary structure of the ITS2 molecule. Acta Protozool. 56, 255–281.

Rossi, M., Dias, R. J. P., Senra, M. V. X., Martinele, I., Soares, C. A. G., and D’Agosto, M. (2015). Molecular phylogeny of the family Ophryoscolecidae (Ciliophora, Litostomatea) inferred from 18S rDNA sequences. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 62, 584–590. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12211

Rossi, M. F., Cedrola, F., Dias, R. J. P., Martinele, I., and D’Agosto, M. (2016). Improved silver carbonate impregnation for rumen ciliate protozoa. Rev. Bras. Zooc. 17, 33–40.

Schulze, P. (1924). Der nachweiss und die verbreitung des chitins mit einem anhang über das komplizierte verdauungsystem der ophryoscoleciden. Z. Morphol. Okol. Tiere 2, 643–666. doi: 10.1007/bf01254877

Sládeček, F. (1946). Ophryoscolecidae z bachoru jelena (Cervus elaphus L.), dan’ka (Dama dama L.) a srnce (Capreolus capreolus L.). Vestnik Ceskoslovenske Zoologicke Spolecnosti. 10, 201–231.

Small, E. B., and Lynn, D. H. (1981). A new macrosystem for the Phylum Ciliophora Doflein, 1901. BioSystems 14, 387–401. doi: 10.1016/0303-2647(81)90045-9

Snelling, T., Pinloche, E., Worgan, H. J., Newbold, J., and McEwan, N. R. (2011). Molecular phylogeny of Spirodinium equi, Triadinium caudatum and Blepharocorys sp. from the equine hindgut. Acta Protozool. 50, 319–326.

Stein, F. (1858). Über mehrere neue im pansen der wiederkäuer lebende infusionstiere. Abhandlungen der k. Böhmischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften 10, 69–70.

Strüder-Kypke, M. C., Kornilova, O. A., and Lynn, D. H. (2007). Phylogeny of trichostome ciliates (Ciliophora, Litostomatea) endosymbiotic in the Yakut Horse (Equus caballus). Eur. J. Protistol. 43, 319–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2007.06.005

Vd’ačný, P. (2015). Estimation of divergence times in litostomatean ciliates (Ciliophora: Intramacronucleata), using Bayesian relaxed clock and 18S rRNA gene. Eur. J. Protistol. 51, 321–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ejop.2015.06.008

Vd’ačný, P. (2018). Evolutionary associations of endosymbiotic ciliates shed light on the timing of Marsupial-Placental split. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1757–1769. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy071

Warren, A., Patterson, D. J., Dunthorn, M., Clamp, J. C., Achiles-Day, U. E. M., Aescht, E., et al. (2017). Beyond the “code”: a guide to the description and documentation of biodiversity in ciliated protists (Alveolata, Ciliophora). J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 64, 539–554. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12391

Wertheim, P. (1935). A new ciliate, Entodinium bovis n. sp., from the stomach of Bos taurus L. with the revision of Entodinium exiguum, E. nanellum, E. simplex, E. dubardi dubardi and E. parvum. Parasitology. 27, 226–230. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000015092

Wolska, M. (1963). Morphology of the buccal apparatus in Balantidium coli (Malmsten, 1857). Acta Protozool. 1, 147–152.

Wolska, M. (1964). Infraciliature of Didesmis ovalis Fior. and Blepharozoum trizonum (Hsiung) - fam. Buetschliidae (Ciliata, Rhabdophorina). Acta Protozool. 2, 153–157.

Wolska, M. (1965). Studies on the representatives of the family Paraistrochidae Da Cunha (Ciliata, Trichostomata). III. Division morphogenesis in the genus Paraisotricha Fior. and Rhizotricha Wolska. Acta Protozool. 3, 27–36.

Wolska, M. (1966a). Application of the ammonium-silver impregnation method to the investigation of ciliates from the rumen. Acta Protozool. 4, 105–108.

Wolska, M. (1966b). Study on the family Blepharocorythidae Hsiung I. Preliminary remarks. Acta Protozool. 4, 97–103.

Wolska, M. (1967a). Study on the family Blepharocorythidae Hsiung II. Charonina ventriculi (Jamenson). Acta Protozool. 4, 279–284.

Wolska, M. (1967b). Study on the family Blepharocorythidae Hsiung III. Raabena bella gen. nov., sp. n. from the intestine of the Indian elephant. Acta Protozool. 4, 284–294.

Wolska, M. (1968). Study on the family Blepharocorythidae Hsiung IV. Pararaabena dentata gen. n., sp. n. from the intestine of Indian elephant. Acta Protozool. 5, 219–225.

Wolska, M. (1969). Triadinium minimum Gassovsky. Its phylogenetic significance. Rev. Soc. Mex. Hist. Nat. 30, 65–78.

Wolska, M. (1970). Spirocorys indicus Wolska, 1969 ciliate holotriche from the intestine of Indian elephant, its systematic position. Acta Protozool. 8, 143–148.

Wolska, M. (1971a). Studies on the family Blepharocorythidae Hsiung. V. A review of genera and species. Acta Protozool. 9, 23–43.

Wolska, M. (1971b). Studies on the family Blepharocorythidae Hsiung VI. Phylogenesis of the family and description of the new genus Circodinium gen. n. with the species C. minimum (Gassovsky, 1918). Acta Protozool. 9, 170–195.

Wolska, M. (1978a). Light and electron microscope studies on Ochoterenaia appendiculata Chavarria (Ciliata, Blepharocorythina). Acta Protozool. 17, 483–492.

Wolska, M. (1978b). Triadinium caudatum Fiorent. Electron microscope observations. Acta Protozool. 17, 445–454.

Wolska, M. (1978c). Tripalmaria dogieli Gass., 1928 (Ciliata, Entodiniomorphida) structure and ultrastructure. Part I. Light-microscope investigations. Acta Protozool. 17, 13–20.

Wolska, M. (1978d). Tripalmaria dogieli Gasso., 1928 (Ciliata, Entodiniomorphida). Structure and ultrastructure. Part II. Electron-microscope investigations. Acta Protozool. 17, 21–30.

Wolska, M. (1979). Circodinium minimum (Gassovsky, 1918), electron-microscope investigations. Acta Protozool. 18, 223–229.

Wolska, M. (1985). A study of the genus Spirodinium Fiorentini. Ciliata, Entodiniomorphida. Acta Protozool. 24, 1–11.

Wolska, M. (1986). Pseudoentodinium elephantis gen. nov., sp. n. from the order Entodiniomorphida. Proposition of the new family Pseudoentodiniidae. Acta Protozool. 25, 139–146.

Wright, A. D. (2015). “Rumen protozoa,” in Rumen Microbiology: From Evolution to Revolution, eds A. K. Punyia, R. Singh, and D. N. Kamra, (Cham: Springer), 113–120. doi: 10.1007/978-81-322-2401-3_8

Wright, A. D., Dehority, B. A., and Lynn, D. H. (1997). Phylogeny of the rumen ciliates Entodinium, Epidinium and Polyplastron (Litostomatea, Entodiniomorphida) inferred from small subunit ribosomal RNA sequences. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 44, 61–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1997.tb05693.x

Wright, A. D. J., and Lynn, D. H. (1997a). Maximum ages of ciliate lineages estimated using a small subunit rRNA molecular clock, crown eukaryotes date back to the paleoproterozoic. Arch. Protist. 148, 329–341. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9365(97)80013-9

Wright, A. D., and Lynn, D. H. (1997b). Monophyly of the trichostome ciliates (Phylum Ciliophora: Class Litostomatea) tested using new 18S rRNA sequences from vestibuliferids, Isotricha intestinalis and Dasytricha ruminantium and haptorian Didinium nasutum. Eur. J. Protistol. 33, 305–315. doi: 10.1016/s0932-4739(97)80008-9

Wright, A. D., and Lynn, D. H. (1997c). Phylogenetic analysis of the rumen ciliate family Ophryoscolecidae based on 18S ribosomal RNA sequences, with new sequences from Diplodinium, Eudiplodinium and Ophryoscolex. Can. J. Zool. 75, 963–970. doi: 10.1139/z97-117

Keywords: Entodiniomorphida, integrative taxonomy, Macropodiniida, symbiotic ciliates, Vestibuliferida

Citation: Cedrola F, Senra MVX, Rossi MF, Fregulia P, D’Agosto M and Dias RJP (2020) Trichostomatid Ciliates (Alveolata, Ciliophora, Trichostomatia) Systematics and Diversity: Past, Present, and Future. Front. Microbiol. 10:2967. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02967

Received: 27 June 2019; Accepted: 09 December 2019;

Published: 15 January 2020.

Edited by:

Sandra Kittelmann, National University of Singapore, SingaporeReviewed by:

Peter Vdacny, Comenius University, SlovakiaSvetlana Kišidayová, Slovak Academy of Sciences (SAS), Slovakia

Copyright © 2020 Cedrola, Senra, Rossi, Fregulia, D’Agosto and Dias. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Roberto Júnio Pedroso Dias, cmp1bmlvZGlhc0Bob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Franciane Cedrola

Franciane Cedrola Marcus Vinicius Xavier Senra1,2

Marcus Vinicius Xavier Senra1,2 Mariana Fonseca Rossi

Mariana Fonseca Rossi Priscila Fregulia

Priscila Fregulia Marta D’Agosto

Marta D’Agosto Roberto Júnio Pedroso Dias

Roberto Júnio Pedroso Dias