- 1Department of Microbiology, National Veterinary Research Institute, Puławy, Poland

- 2Department of Omics Analyses, National Veterinary Research Institute, Puławy, Poland

- 3Research Group for Genomic Epidemiology, European Union Reference Laboratory for Antimicrobial Resistance, WHO Collaborating Centre for Antimicrobial Resistance in Foodborne Pathogens and Genomics, National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark

- 4Statens Serum Institute, Copenhagen University, Copenhagen, Denmark

- 5Department of Epidemiology, National Veterinary Research Institute, Puławy, Poland

The emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance (mcr genes) threatens the effectiveness of polymyxins, which are last-resort drugs to treat infections by multidrug- and carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Based on the occurrence of colistin resistance the aims of the study were to determine possible resistance mechanisms and then characterize the mcr-positive Escherichia coli. The research used material from the Polish national and EU harmonized antimicrobial resistance (AMR) monitoring programs. A total of 5,878 commensal E. coli from fecal samples of turkeys, chickens, pigs, and cattle collected in 2011–2016 were screened by minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination for the presence of resistance to colistin (R) defined as R > 2 mg/L. Strains with MIC = 2 mg/L isolated in 2014–2016 were also included. A total of 128 isolates were obtained, and most (66.3%) had colistin MIC of 2 mg/L. PCR revealed mcr-1 in 80 (62.5%) isolates recovered from 61 turkeys, 11 broilers, 2 laying hens, 1 pig, and 1 bovine. No other mcr-type genes (including mcr-2 to -5) were detected. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of the mcr-1–positive isolates showed high diversity in the multi-locus sequence types (MLST) of E. coli, plasmid replicons, and AMR and virulence genes. Generally mcr-1.1 was detected on the same contig as the IncX4 (76.3%) and IncHI2 (6.3%) replicons. One isolate harbored mcr-1.1 on the chromosome. Various extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (blaSHV–12, blaCTX–M–1, blaCTX–M–15, blaTEM–30, blaTEM–52, and blaTEM–135) and quinolone resistance genes (qnrS1, qnrB19, and chromosomal gyrA, parC, and parE mutations) were present in the mcr-1.1–positive E. coli. A total of 49 sequence types (ST) were identified, ST354, ST359, ST48, and ST617 predominating. One isolate, identified as ST189, belonged to atypical enteropathogenic E. coli. Our findings show that mcr-1.1 has spread widely among production animals in Poland, particularly in turkeys and appears to be transferable mainly by IncX4 and IncHI2 plasmids spread across diverse E. coli lineages. Interestingly, most of these mcr-1–positive E. coli would remain undetected using phenotypic methods with the current epidemiological cut-off value (ECOFF). The appearance and spread of mcr-1 among various animals, but notably in turkeys, might be considered a food chain, and public health hazard.

Introduction

The worldwide increase in the occurrence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and prevalence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae challenge our ability to treat infections in humans and animals, thus resulting in a renewed interest in old drugs such as polymyxins. Colistin (polymyxin E), which has been used in veterinary practice for decades mainly for treating Gram-negative bacteria infections of the gastrointestinal tract in pigs, poultry and cattle, is nowadays considered a last-resort drug to treat human infections by multidrug-, and carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Together with third, fourth, and fifth generation cephalosporins, glycopeptides, quinolones, and macrolides, polymyxins are among the critically important antimicrobials (CIA) for human medicine (World Human Organization [WHO], 2017) and should be mainly used for treating the severest human infections to preserve their effectiveness. Antimicrobials are used in hospitals and care facilities as well as in veterinary clinics and on farms. Extensive use of antimicrobials is recognized as the most important factor selecting for AMR in bacteria (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2013). According to the European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption (ESVAC) report, sales of veterinary antimicrobial agents in 2016 varied from 0.7 to 2,726.5 tons in the 30 participating countries (European Medicine Agency [EMA] and European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption [ESVAC], 2018). Notably, polymyxins were the fifth most sold group of antimicrobials in 2015–2016 (European Medicine Agency [EMA] and European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption [ESVAC], 2017, 2018). In Poland, colistin sales increased by 35% from 2011 to 2016, reaching their highest value of 5.94 mg per population correction unit (PCU) in 2015 and exceeding the recommended maximum sale target of 5 mg/PCU for this antimicrobial (European Medicine Agency [EMA] and European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption [ESVAC], 2016, 2017, 2018). Currently, there are 26 veterinary medicinal products containing colistin (Colistini sulfas or colistinum) registered in Poland as powders for oral solution, with six registered only in 20171.

In Enterobacteriaceae, resistance to polymyxines was theorized to be regulated by the two-component systems PhoP/PhoQ and PmrA/PmrB involved in LPS modifications (Olaitan et al., 2014). The emergence and spread of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance (the mcr-1 gene), first described in China in 2015 (Liu et al., 2016), and poses a threat to the effectiveness of colistin. The mcr-1 gene has been detected in several bacterial species (Li et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2017; Torpdahl et al., 2017) in association with different plasmid types such as IncI2, IncHI2, IncP, IncFIP, and IncX4 and also inserted into the bacterial chromosome (Liu et al., 2016; Zurfluh et al., 2016; Hadjadj et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2018). New mcr genes and their variants have also been identified: mcr-2 (Xavier et al., 2016), mcr-3 (Yin et al., 2017), mcr-4 (Carattoli et al., 2017), mcr-5 (Borowiak et al., 2017), mcr-6 (Abuoun et al., 2017), mcr-7 (Yang et al., 2018), mcr-8 (Wang et al., 2018), and mcr-9 (Carroll et al., 2019).

Little is known about the prevalence of colistin resistance and the occurrence of mcr genes in livestock in Poland. In 2015, a single case of mcr-1–positive Escherichia coli was described from a human patient with a urinary tract infection (Izdebski et al., 2016). This might be the first evidence from Poland that mcr-mediated colistin resistance from animals has spread to humans, which would validate concerns over foodborne transfer of colistin-resistant bacteria to humans (Grami et al., 2016). Based on investigation of the occurrence of colistin resistance among E. coli isolated from food-producing animals in Poland over a 6-year period, the aim of the study was to determine the resistance mechanisms among the colistin-resistant isolates. Whole genome sequence analysis of the mcr-1–positive E. coli strains was made to elucidate the pathways of dissemination of mcr-1 in food-producing animals in Poland and highlight possible animal and public health threats.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Isolates

A total of 5,878 commensal E. coli isolates were obtained from individual fecal samples collected from turkeys, chickens, pigs and cattle in 2011–2016, and tested for antimicrobial susceptibility by minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination (Sensititre, TREK Diagnostic; EUMVS2 and EUVSEC plates). The isolates were screened to confirm the presence of microbiological resistance (R) to colistin (R > 2 mg/L). Additionally, available isolates with MIC = 2 mg/L (wild-type isolates) from 2014 to 2016 were included in the study because they represented colistin MIC values one dilution step from those considered as non-wild type (NWT). Isolates were collected as part of the multiannual national program (2011–2016) and the EU harmonized AMR monitoring program carried out in 2014–2016 (Decision 2013/652/EU). Those programs are based on isolation of commensal E. coli from the cecal content of samples collected from random animals at slaughter. The sampling was carried out by veterinary officers on a by-slaughterhouse basis proportionally to the annual capacity of the slaughterhouse and at intervals distributed over the 6-year period. The antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) for ampicillin, azithromycin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, colistin, nalidixic acid, meropenem, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, tigecycline, and trimethoprim was interpreted according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) criteria describing epidemiological cut-off values (ECOFFs) for antimicrobials. The selected isolates were subjected to PCR targeting the mcr-1 and mcr-2 genes (Cavaco et al., 2016). Subsequently, resistant isolates were whole-genome sequenced (WGS) as detailed below. PCR-negative strains were re-tested phenotypically to confirm the MIC to colistin and screened for the presence of mcr-1, -2, -3, -4, and -5 using PCR (Rebelo et al., 2018).

Whole Genome Sequencing

DNA from bacterial cells of the 80 mcr-1–positive isolates was extracted from nutrient agar plate cultures using a Genomic Mini Kit (A&A Biotechnology) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Sequencing libraries were prepared with the Nextera XT DNA Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing of the strains was performed using Illumina MiSeq 2 bp × 250 bp and 2 bp × 300 bp reads or Illumina HiSeq 2 bp × 150 bp reads, generating on average 398 Mb per sample (176–673 Mb), which corresponds to average coverage of 80× (35–135×) in a 5 Mb genome. The raw reads were processed using bbmerge v36.62 (Bushnell, 2018) to merge overlapping reads and Trimmomatic v0.36 (Bolger et al., 2014) to trim adapters and low quality reads. Merged reads and trimmed unmerged pairs were used to generate assembly contigs and scaffolds using SPAdes 3.9.0 (Bankevich et al., 2012). The mean N50 of assemblies was 178 kb (77–433 kb) and the average number of contigs longer than 1 kb was 102 (40–364). Six isolates where the mcr gene was not located on the same contig as a plasmid replicon were subjected to additional Pacific Biosciences long-read sequencing, three samples per SMRTcell. The raw PacBio reads were de-multiplexed to subreads using lima 1.0.0 (Pacific Biosciences) (Topfer, 2018) yielding on average 225 Mb per sample (72–390 Mb), which translates to average 45× coverage (14.4–78×) of a 5 Mbps genome. The mean subread length was 3,555 bp (3,183–3,929 bp) and mean basepair quality 13.1 (12.95–13.22). Subreads were used in a hybrid SPAdes assembly together with raw short Illumina reads. Assembly analysis with QUAST 4.5 (Gurevich et al., 2013) reported 8–13 contigs longer than 10 kb per sample and 2.1 Mb average N50 (0.91–3.9 Mb). The DNA sequences (reads) from the isolates were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) under project number PRJEB23993. Specific sequence numbers are included in Supplementary Table S1. E. coli strains which codes start from “U” were gathered within antimicrobial resistance monitoring according to 2013/652/EC and they are included in the annual EFSA/ECDC reports.

Bioinformatic Data Analysis

Sequences were analyzed for the presence of AMR genes, virulence genes and plasmid replicons by using the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (CGE)2 ResFinder 3.1.0 (with database updated on September 10, 2018) (Zankari et al., 2012), VirulenceFinder 1.5 (February 18, 2016) (Joensen et al., 2014), PlasmidFinder 1.3 (December 15, 2017) (Carattoli et al., 2014), and pMLST v1.4 (December 15, 2017) (Carattoli et al., 2014) web-based tools for typing of IncHI2 plasmids. The criteria for these tools were: 90% threshold for identity with the reference and minimum 60% coverage of the gene length. Multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) of strains was performed using MLST 1.8 (Carattoli et al., 2014). The phylogenetic tree of 80 isolates was constructed by complete linkage clustering using a sequence similarity distance matrix. The distance matrix was generated by global pairwise MUMmer 3.23 (Kurtz et al., 2004) alignments between samples’ scaffolds, automated by CONCOCT 0.4.0 (Alneberg et al., 2014). A phylogenetic tree of IncX4 plasmids was created in a similar way, using contigs carrying the IncX4 replicon and the mcr-1 gene. The mcr-1 carrying contigs were identified using BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) and mcr-1 sequence AKF16168.1. The iTol web-based tool (Letunic and Bork, 2016) was used to visualize the trees.

Results

Occurrence of Colistin Resistance and mcr-1

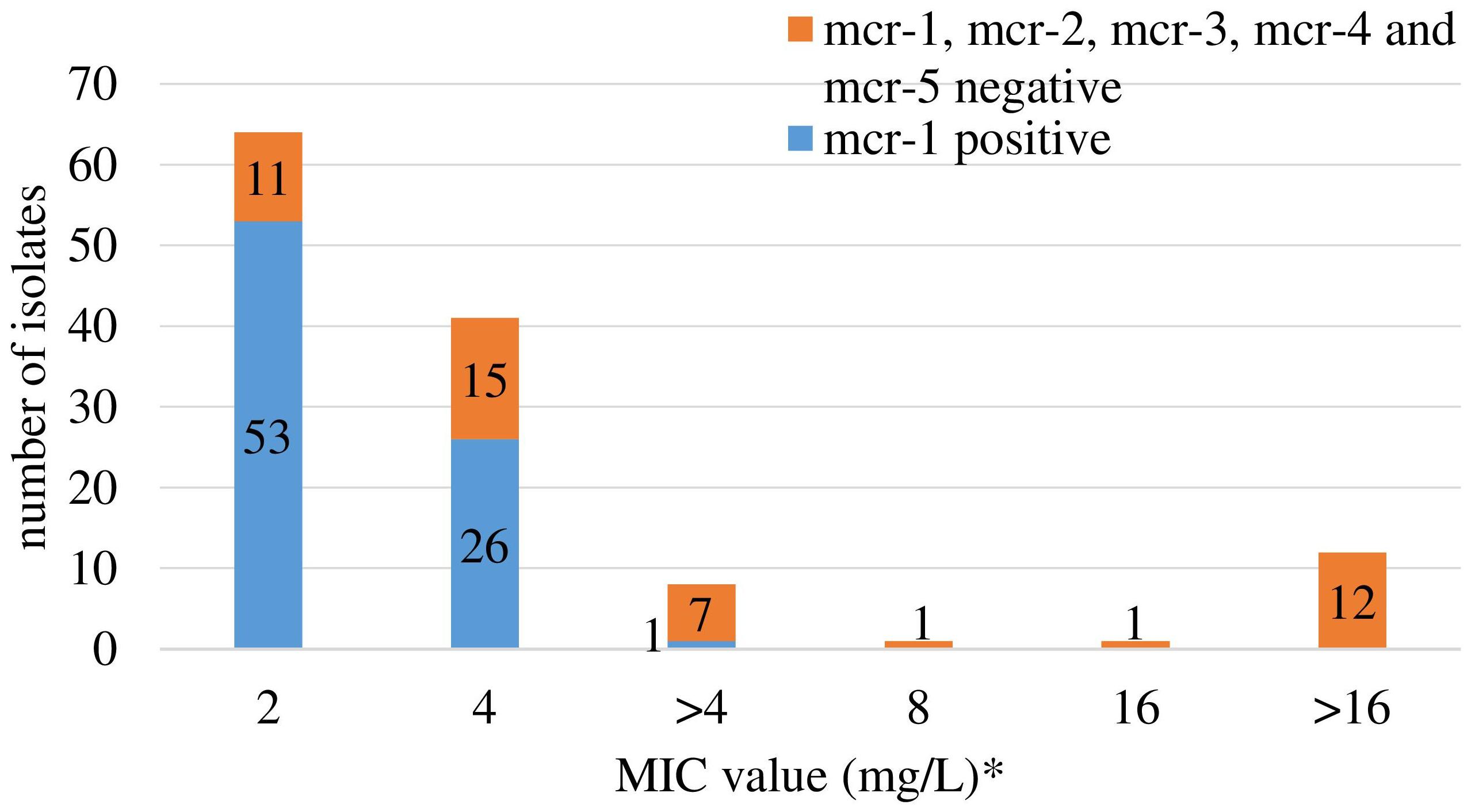

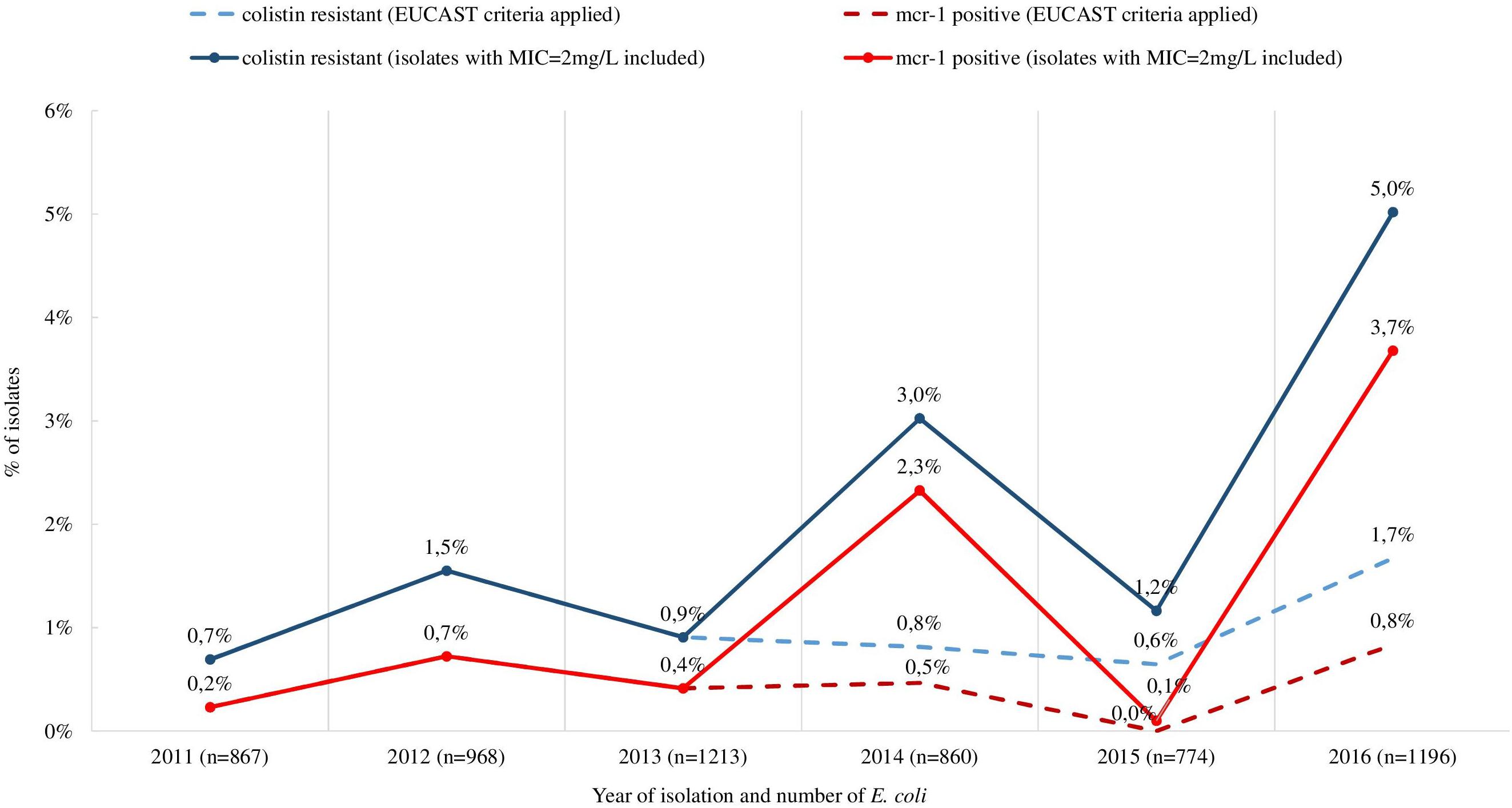

Retrospective analysis of MIC data revealed a total of 128 (2.2%) out of 5,878 commensal E. coli fulfilling the selection criteria with colistin MICs ranging from 2 to 16 mg/L (Figure 1). They originated mostly from turkeys (63%) and chickens (23%). A slight temporal increase of microbiological resistance to colistin from very low to low (0.7–1.7%) was observed when considering all E. coli isolates detected in samples from 2011 to 2016 taken from Polish food-producing animals irrespective of their origin (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Colistin MIC distribution and occurrence of the mcr-1 and mcr-2 gene among 128 Escherichia coli selected based on colistin MIC > 2 mg/L (2011–2013) and ≥2 mg/L (2014–2016). ∗ only isolates with MICcolistin ≥ 2 mg/L were tested for mcr-1 and mcr-2 genes. Different MIC values (>4 and 8, 16, and >16) are result of changed MIC panel in plates. EUMVS2 plate (2–4 mg/L) was used in 2011–2013, EUVSEC plate (1–16 mg/L) in 2014–2016.

Figure 2. Occurrence of isolates meeting the selection criteria (MIC > 2 mg/L for isolates in 2011–2013 and MIC ≥ 2 mg/L for isolates in 2014–2016) and mcr-1 positive commensal and ESBL/ampC producing E. coli from all tested sources (turkeys, chickens, pigs, and cattle), 2011–2016. The occurrence of colistin resistant and mcr-1 positive isolates when using exclusively EUCAST ECOFF was included (dashed line).

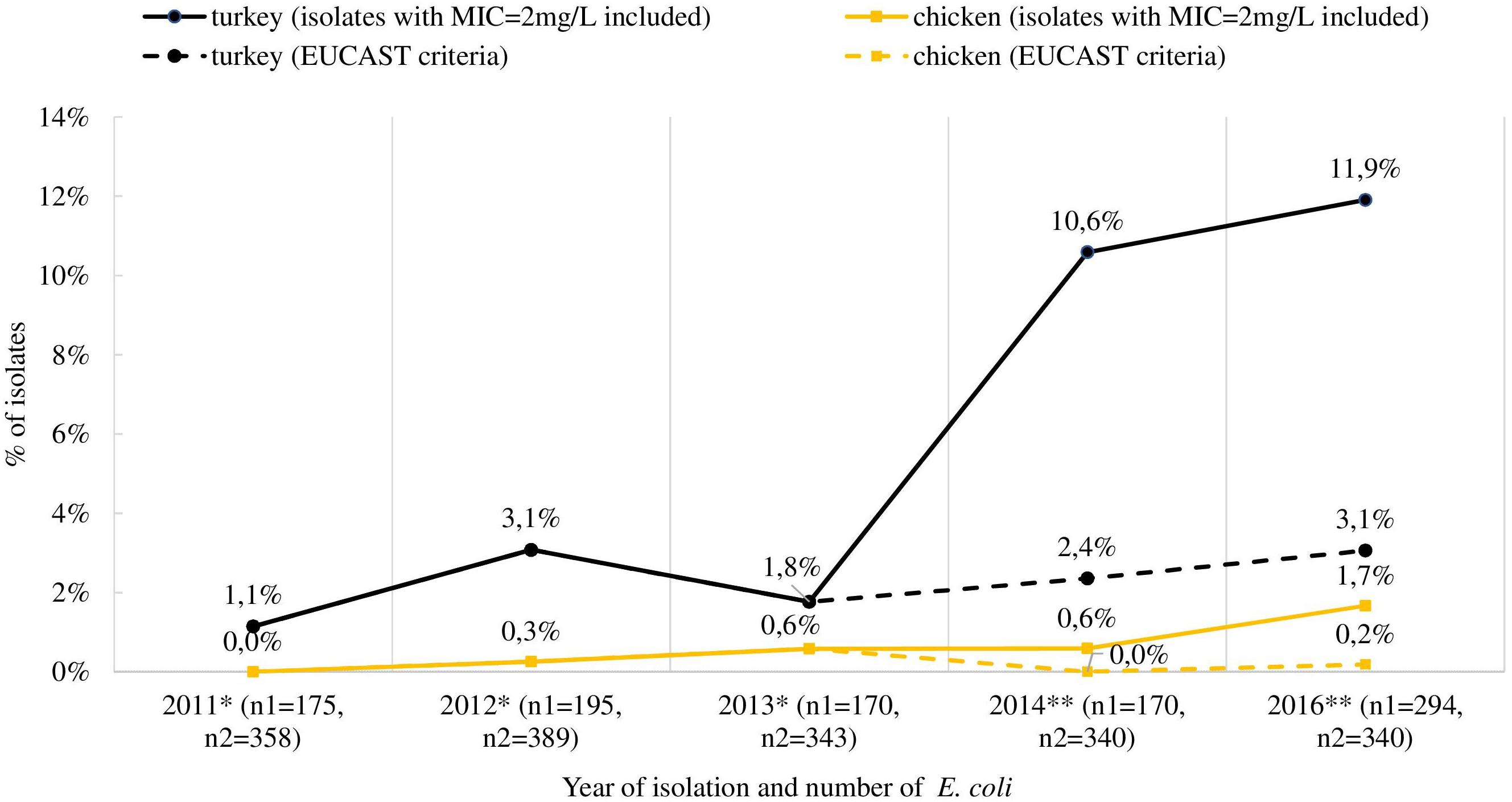

The mcr-1 gene was detected in 80 (62.5%) out of the selected 128 isolates, deriving from 76 fecal samples recovered from turkeys (n = 61), broilers (n = 11), laying hens (n = 2), pigs (n = 1), and cattle (n = 1). Most of the mcr-1–positive E. coli originated from individual samples, but in four samples from turkeys (n = 3) and broilers (n = 1), two different isolates per sample were identified (Supplementary Table S1). An increase in occurrence of the mcr-1–positive E. coli was noted in turkey and chicken samples, respectively from 1.1 and 0.0% in 2011 to 11.6 and 1.7% in 2016 (Figure 3). The CGE ResFinder tool confirmed the presence of the mcr-1.1 gene in all PCR-confirmed isolates. No mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4, or mcr-5 was identified either from PCR or the genome analysis in mcr-1–positive isolates. Noteworthily, the mcr-1.1 was mostly found (n = 53; 66.3%) in isolates with colistin MIC = 2 mg/L which is the EUCAST ECOFF and regarded as that of the wild-type population. Most of these (n = 41; 77.4%) were sampled from turkeys. Additionally, a mutation in the chromosomal pmrB gene (Val161→Gly) was detected in one mcr-1.1–positive isolate with MIC = 2 mg/L.

Figure 3. Occurrence of mcr-1-positive E. coli in Poland isolated from turkey and chicken fecal samples. ∗ isolates collected in multiannual governmental programs (according to of the Council of Ministers Decisions), ∗∗ isolates deriving from official monitoring according to Decision 2013/652/EC and thus not encompassing samples from turkeys and broilers in 2015; n1 and n2 indicate the total number of isolates tested for MIC determination from turkeys and chickens (both broiler and laying hens), respectively. The occurrence of mcr-1 positive strains when using exclusively EUCAST ECOFF during selection of isolates was also included (dashed line).

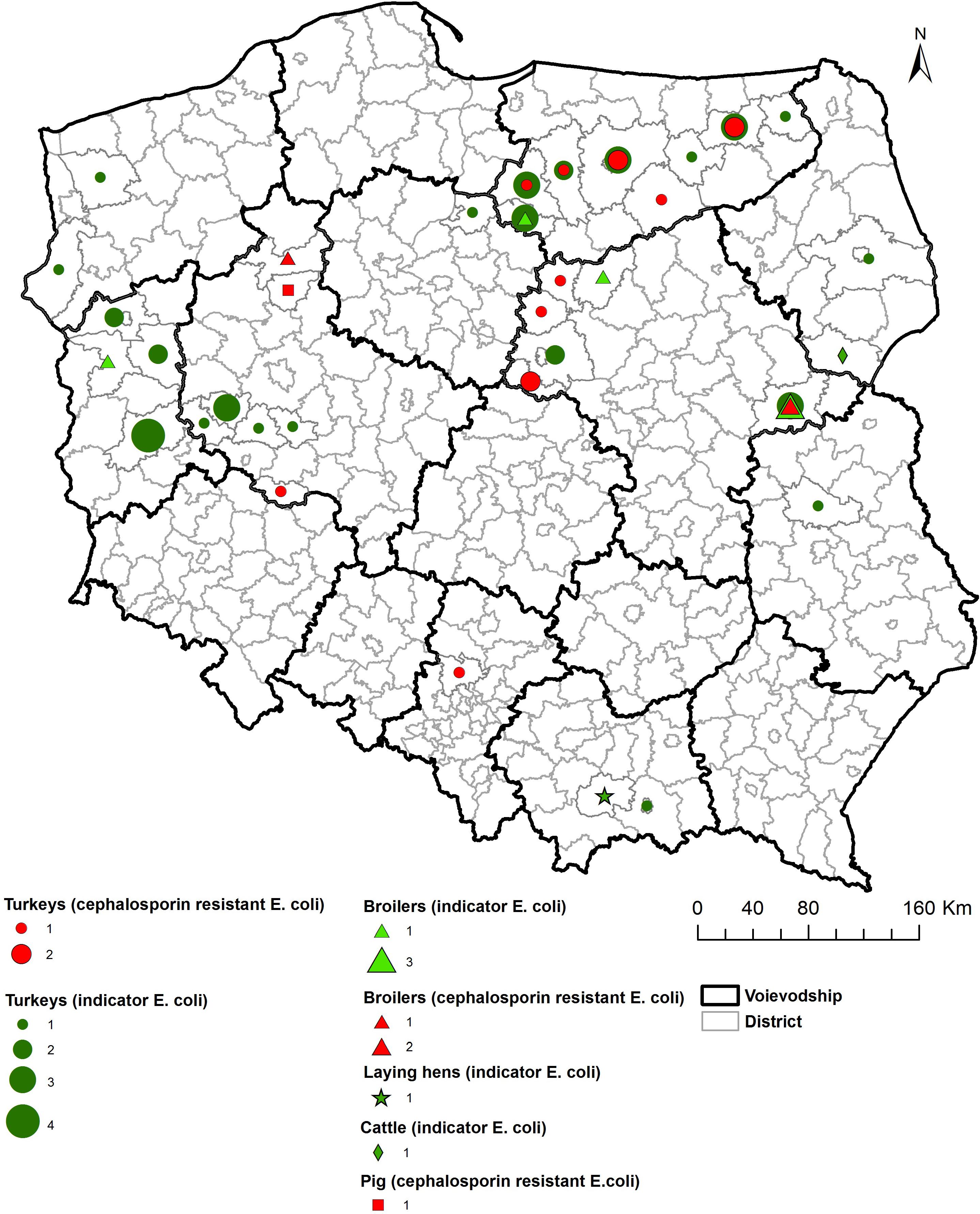

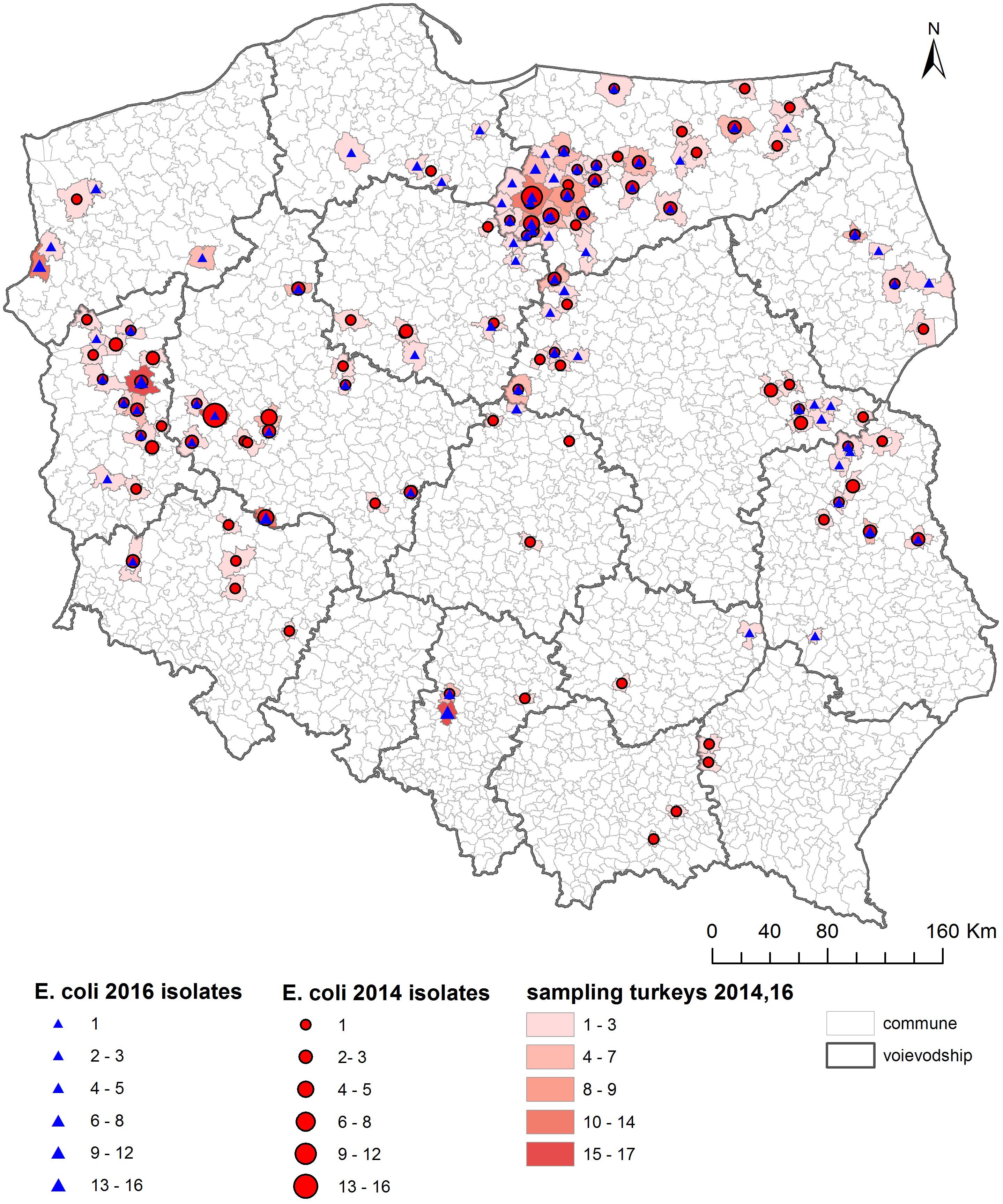

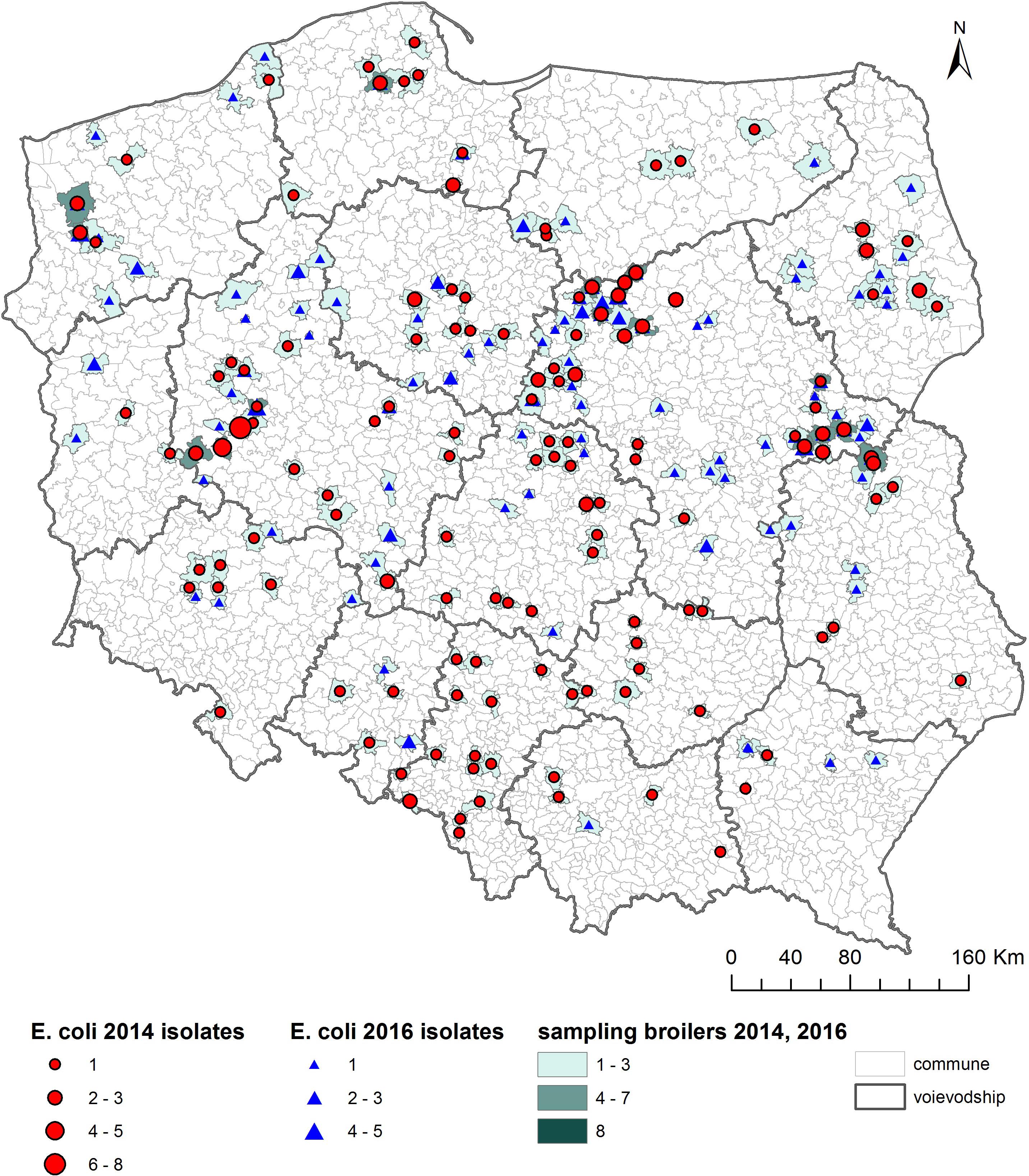

As shown on the maps of the farm locations from which mcr-1–positive E. coli was isolated, the colonized farms were distributed over the country with no specific regional trend (Figures 4–6).

Figure 4. Geographical distribution (commune level) of turkey sampling. Single turkey caeca was collected at slaughter and farm of origin was retrieved for verification of randomization of samples used for isolation of indicator E. coli in 2014 and 2016.

Figure 5. Geographical distribution (commune level) of broiler sampling. Single broiler caeca was collected at slaughter and farm of origin was retrieved for verification of randomization of samples used for isolation of indicator E. coli in 2014 and 2016.

An MIC ≥ 2 mg/L for colistin could not be confirmed in any of the re-tested 48 isolates initially suspected but found negative for mcr-1 and mcr-2, and none of the mcr-1, -2, -3, -4, or -5 genes were identified by PCR. They were not investigated further as we considered them either false positives in the initial testing, or to have eventually lost the mechanisms over prolonged storage or handling.

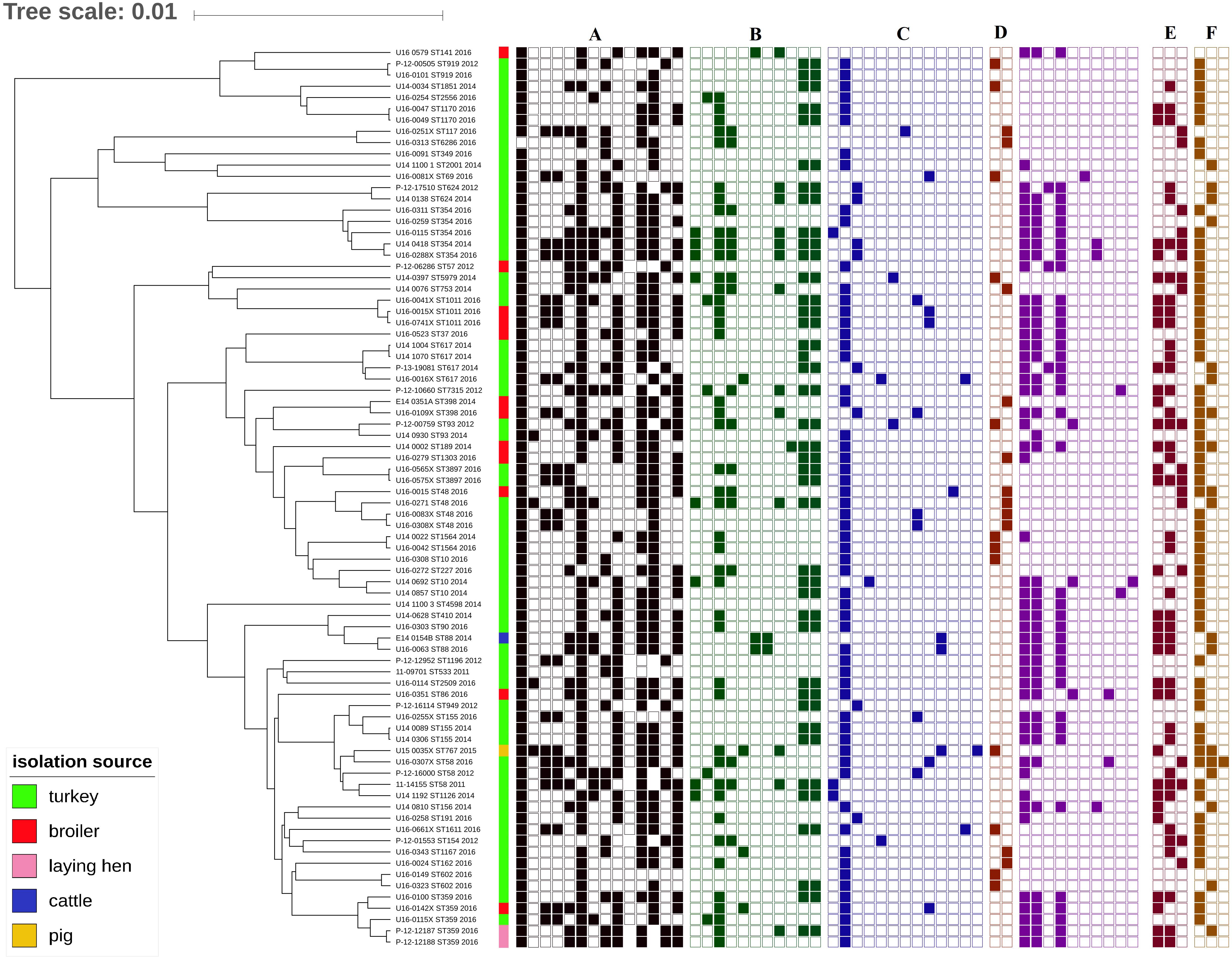

Phylogeny and Epidemiology

The MLST revealed 49 ST among the sequenced isolates. In 64 E. coli from turkeys, 41 STs were identified, as were 10 in 14 chicken isolates. The most common types were ST354 and ST359, which were observed in five isolates each, ST48 and ST617 which were identified in four isolates each, and ST10, ST58, ST155, and ST1011 which were represented by three isolates each. Single isolates represented 32 ST (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Phylogeny of mcr-1-positive E. coli (sequence types, year and source of isolation, and map of phenotypic resistance and resistance genes). Full and empty square mean presence and absence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) gene, respectively, whereas empty space means non-defined or not tested. (A) Resistance profiles (black): ampicillin, azithromycin, cefuroxime, ceftazidime, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, colistin, nalidixic acid, meropenem, sulphonamides, tetracycline, tigecycline, and trimethoprim (Sensititre EUSVEC MIC panel). (B) Aminoglycoside resistance genes (green): aac(3)-IIa, aac(3)-IId, aadA1, aadA2, aadA5, aadA24, aadB, aph(3′)-Ia, aph(3′)-Ic, aph(3″)-Ib, and aph(6)-Id. (C) Beta-lactam resistance genes (blue): blaTEM–1A, blaTEM–1B, blaTEM–1C, blaTEM–30, blaTEM–135, blaTEM–52C, blaCMY–2, blaSHV–12, blaOXA-1,blaCARB-2, and blaCTX–M–1. (D) Quinolone resistance genes: plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR, brown): qnrS1, qnrB19; mutations in quinolone resistance determining regions (QRDR, violet): gyrA S83L, gyrA D87N, gyrA D87Y, parC S80I, parC S80R, parC S57T, parC E84G, parC E84K, parE L416F, and parE L460D. (E) Sulphonamide resistance genes (dark brown): sul1, sul2, and sul3. (F) Tetracycline resistance genes (light brown): tet(A), tet(B), and tet(M).

The analysis showed high heterogeneity of mcr-1–positive E. coli independent of source and year of isolation. Isolates deriving from animals from 27 farms and slaughtered in 27 slaughterhouses (Supplementary Table S2) were clustered according to their ST. The majority of isolates belonging to the most numerous STs (i.e., ST48, ST88, ST359, and ST1011) derived from different animal species (Figure 7) slaughtered in different slaughterhouses (Supplementary Table S1) and originating from different farms or flocks (data not shown). In cases where the same ST was found in animals from the same slaughterhouse and/or farm, the mcr localization and plasmid profile were often different, as for example with ST354 observed exclusively in turkeys where two isolates deriving from the same farm but slaughtered in different places had mcr localized on IncX4 (U16_0311), and chromosome (U16_0259) (Supplementary Table S1). In a few cases, the same ST (i.e., ST354, ST359, ST919, and ST1564) was present among strains isolated in different years.

Phenotypic and Genetic Traits of Microbiological Resistance to Additional Antimicrobials

The mcr-1–positive strains showed resistance to at least two and up to seven different classes of antimicrobials and had different resistance gene contents. Seventy-eight (97.5%) mcr-1-positive E. coli were classified as MDR isolates. Seventy-nine (98.8%) were resistant to ampicillin and 22 (27.5%) to cefotaxime and ceftazidime. Resistance to ciprofloxacin was confirmed in 70 (87.5%), to tetracycline in 61 (76.3%), to nalidixic acid in 50 (62.5%), to chloramphenicol in 27 (33.8%), to gentamicin in 16 (20.0%), and to tigecycline in 12 (15.0%). Four of the isolates had an azithromycin MIC ≥ 16 mg/L, which can be interpreted as resistance according to the tentative ECOFF for this antimicrobial. The strains were susceptible to meropenem and presented no resistance genes to carbapenems.

The whole-genome sequencing data revealed the occurrence of blaTEM–1 in the majority (n = 73; 92.4%) of the ampicillin-resistant isolates. The genes encoding extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) and AmpC-type cephalosporinases were identified in 18 (22.5%) E. coli belonging to 14 STs: blaSHV–12 was present in five isolates (ST58, ST69, ST359, and ST1011), blaCTX–M–1, blaTEM–30, and blaTEM–135 in two each (respectively, ST617, ST1611, ST154, ST617, ST93, and ST5979), single isolates carried blaCTX–M–15 (ST767), or blaTEM–52C (ST117) and blaCMY–2 was present in six strains (ST48, ST58, ST155, ST398, and ST1011) (Figure 7). Fifteen isolates carried extended-spectrum cephalosporin (ESC) resistance gene in combination with blaTEM–1. Two isolates, U15_0035X (ST767) and U16_0016X (ST617), possessed simultaneously two ESC resistance genes, respectively, blaCTX–M–15 with blaCMY–2 and blaCTX–M–1 with blaTEM–30. The swine isolate (U15_0035X) was the only one carrying the blaCTX–M–15 gene.

Analysis of the genetic background of resistance to quinolones showed chromosomal mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of topoisomerase genes in 63.8% (n = 51) isolates, resulting in amino acid substitutions in the gyrA subunit [Ser83→Leu (n = 48); Asp87→Ans (n = 40), Asp87→Tyr (n = 2)], parC [Ser80→Ile (n = 37), Ser80→Arg (n = 4); Ser57→Thr (n = 1); Glu84→Gly (n = 3), Glu84→Lys (n = 2)], and parE [Leu416→Phe (n = 2), Leu460→Asp (n = 1)]. The gyrB gene remained unaltered. Several silent mutations irrelevant for quinolone resistance were also noted. Different patterns combining up to four simultaneous amino acid substitutions were noted among tested isolates with a combination of mutations in gyrA S83L, gyrA D87N, and parC S80I being the most frequent (n = 30) (Figure 7). Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) genes were detected in 23 isolates, namely qnrS1 (n = 12) and qnrB19 (n = 11) (Figure 7). Four of the PMQR carriers also harbored QRDR chromosomal mutations. Eight isolates carried both ESBL/AmpC and PMQR determinants. The aac(6′)Ib-cr gene, conferring resistance to both quinolones and aminoglycosides, was identified in two strains, occurring along with qnrS1 (U15_0035X), or the set of mutations in gyrA (S83L and D87N) and parC (S80I and E84G) (U14_0810). A 21.3% portion of the isolates carrying quinolone resistance mechanisms were also confirmed as ESBL- or AmpC-producers.

A variety of gentamicin resistance genes was identified. The sequences revealed genes coding N-acetyltransferases catalyzing acetyl CoA-dependent acetylation of an amino group, like aac(3′)-IIa (n = 8) and aac(3′)-IId (n = 5), and O-phosphotransferases (APH) catalyzing ATP-dependent phosphorylation of a hydroxyl group, namely aph(3′)-Ia (n = 14) (Supplementary Table S1). Overall, there was 93.8% genotype–phenotype correlation for gentamicin resistance. The presence of genes coding adenyltransferases [aadA1, aadA2, aadA5, aadA24, and ant(2”)-Ia] was identified in 50 isolates (Supplementary Table S1). WGS data showed the occurrence of three genes responsible for macrolide resistance: mph(B), mph(A), and msr(E)-mph(E) in single isolates with MICs equal to 8, 16, and 32 mg/L, respectively. Sixty isolates were resistant to sulfonamides due to sul1 (n = 32), sul2 (n = 39), or sul3 (n = 18). In 5 isolates all three genes occurred simultaneously, while in 23 a set of two genes was found with sul1 and sul2 being the most frequent (n = 19). Of the 49 trimethoprim-resistant E. coli, 45 harbored at least one of the following genes: dfrA1 (n = 33), dfrA12 (n = 2), dfrA14 (n = 5), dfrA15 (n = 1), dfrA16 (n = 1), and dfrA17 (n = 5).

At least one of the tetracycline resistance genes tet(A) or tet(B) was carried by 73 isolates, these genes being found, respectively in 60 and 18 E. coli. In five isolates both genes were detected and tet(M) was additionally identified in one of them. Overall, there was 100% genotype–phenotype correlation for tetracycline resistance. In 31 isolates the presence of catA1 (n = 13), catB3 (n = 2), cmlA1 (n = 18), and floR (n = 10) was confirmed. In four isolates the resistance genes were present despite a lack of phenotypic resistance to chloramphenicol. Two of them possessing the cmlA1 gene had MIC = 16 mg/L, one isolate had two point mutations in cmlA1 and in the last case a fragment of the catB3 gene was missing (short contig length).

Plasmids and Location of the mcr-1 Gene

Escherichia coli positive for mcr-1 carried a wide variety of plasmid incompatibility group replicons in different proportions and ranging from 4 up to 11 replicons per strain (Supplementary Table S1). The most frequent were: IncFIB (AP001918) (n = 64), ColRNAI (n = 47), Col (MG828) (n = 43), IncFII (n = 40), IncI1 (n = 30), p0111 (n = 24), IncFIC (FII) (n = 21), Col156 (n = 17), IncX1 (n = 17), IncHI2A (n = 16), IncQ1 (n = 14), and IncN (n = 9). Plasmid replicons of all other identified plasmids are noted in Supplementary Table S1.

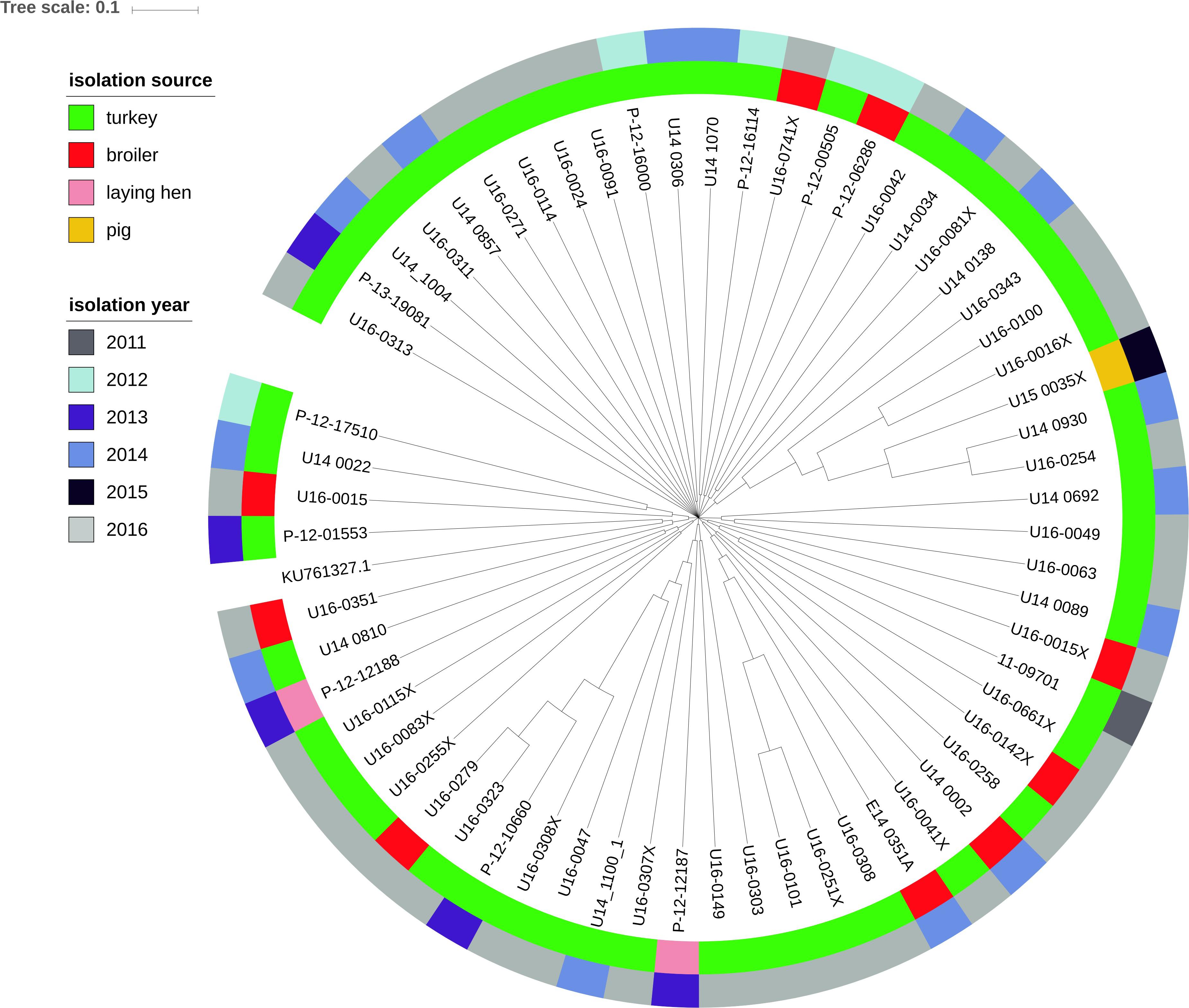

Sixty-one isolates out of the 80 mcr-1–positive E. coli (76.3%) harbored plasmids of the IncX4 group with the replicon located on the same contig of the mcr-1 gene (hereafter IncX4–mcr-1 contigs). In most cases, the mcr-1 gene was the only resistance gene found on IncX4–mcr-1 contigs, which ranged in size from 10772 to 39252 bp. The isolates U16_0149 and U16_0323 also contained the qnrS1 and blaTEM–1 genes and IncX1 replicon located on the IncX4–mcr-1 contig (contig sizes 76785 bp and 69841 bp, respectively). IncX4–mcr-1 contigs were of high sequence similarity and clustered independently of the sample isolation source and sampling year (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Phylogenetic relationship of contigs with mcr-1 and IncX4 plasmid replicon extracted from the genomes of 61 E. coli isolates by source and year of E. coli isolation. Complete sequence of IncX4 plasmid with accession number KU761327.1 from GenBank was used as the reference.

In five of the mcr-1–positive E. coli isolates (6.3%), IncHI2 plasmids were found to be mcr-1 carriers. In 4 out of 5 cases the mcr-carrying plasmid was identified using PacBio data as it was not possible to link the plasmid replicon with the mcr-1 gene using only short Illumina reads. All the IncHI2–mcr-1 plasmids were subtyped as pST4. On the IncHI2–mcr-1 contig (234213 bp) of the U16_0565X isolate additional resistance genes were identified as follows: aadA1, aadA2, blaTEM–1B, catA1, cmlA1, sul1, and tet(A). This isolate possessed the blaTEM–52C gene located on the other contig (8917 bp). On the IncHI2–mcr-1 contig (235356 bp) of U16_0288X, aac(3)-IIa, aadA1, aadA2, blaTEM–1C, sul1, cmlA1, dfrA1, tet(A), aph(3″)-Ib, and aph(6)-Id were also found. The presence of the aph(3′)-Ia gene was confirmed on the relevant contig (201917 bp) of U16_0579. No other plasmid replicons except IncHI2 were annotated on those contigs.

Three isolates (3.7%) possessed both the IncHI2 and IncX4 replicons, but mcr-1 was associated with IncX4. In one strain (U16_0259) a chromosomal location of the mcr-1 gene was confirmed (data not shown). In 15.0% (n = 12) of isolates no plasmid replicons were found on contigs carrying the mcr-1 gene (ranging in size from 2587 to 57048 bp) but the presence of the IncX4 or IncHI2 replicon in the assembly was confirmed. A curiosity is that in two E. coli (ID U16_0115 and U16_0115X) isolated from the same sample, the mcr-1 genes were located on different incompatibility group plasmids (IncX4 or IncHI2).

Virulence Genes

The virulence genes were variable among isolates (Supplementary Table S1). Of the 80 E. coli sequences, six contained one virulence gene, whereas the remainder carried up to 10 virulence genes. The most common were: gad (n = 72), iss (n = 62), iroN (n = 56), lpfA (n = 41), cma (n = 28), mchF (n = 25), astA (n = 19), air (n = 15), eilA (n = 13), and tsh (n = 10), whereas cba, celb, ireA, vat, capU, iha, and mcmA were found in single isolates. We found no correlation of virulence genes with sample source or sampling year. Isolates were characterized with different sets of virulence genes. Notably, one isolate (U14_0002) presented a unique set of virulence genes (cif, eae, espA, espB, espF, nleB, tccP, and tir) that designated it as atypical enteropathogenic E. coli (aEPEC) group (Supplementary Table S1).

Discussion

Based on screening of colistin MIC values in E. coli derived from various monitoring programs on AMR in 2011–2016, we collected extensive information about the occurrence of the mcr-1 gene in E. coli isolated from food-producing animals in Poland. Detailed characterization of mcr-1–positive isolates from several hosts, different geographical locations, and a range of sampling years included analysis of the phenotypic AMR to a broad range of antimicrobials and its genetic background, the presence of virulence genes, plasmid replicons, and ST identification.

Many European countries reported the occurrence of colistin resistance in E. coli deriving from both humans and animals (Hasman et al., 2015; Irrgang et al., 2016; Malhotra-Kumar et al., 2016; Perrin-Guyomard et al., 2016; Carattoli et al., 2017; Duggett et al., 2017; Hartl et al., 2017; Kawanishi et al., 2017; Apostolakos and Piccirillo, 2018). In Poland, we observed a slight increase in colistin resistance in E. coli and also in the prevalence of mcr-positive isolates originating from healthy livestock from 0.7 to 1.7% and 0.2 to 3.7%, respectively in the analyzed time frame, irrespective of the animal of origin. The overall occurrence of colistin resistance in turkeys was higher than in chickens but it still remained low compared to data from some European countries (European Food Safety Authority [EFSA], 2018).

Escherichia coli totaling 53 mcr-positive E. coli were identified after including isolates with MICcolistin = 2 mg/L, which is the EUCAST epidemiological cut-off delimiting the wild-type population. Applying this criterion, the prevalence was 3.7% mcr-1–positive E. coli rather than 0.8% in Poland in 2016. Detection of the mcr gene in wild-type isolates was reported (Fernandes et al., 2016; Lentz et al., 2016; Hadjadj et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017) and might result from a non-functional mcr-1 gene (Terveer et al., 2017). Some reports indicate the possibility of deactivation of mcr-1 by insertion of an IS1294b element and its reactivation by the loss of that element under colistin selection pressure (Zhou et al., 2018). In the current study, all of the mcr-1 had the typical sequence of the mcr-1.1 gene. In some cases, the wild-type concentration MICcolistin = 2 mg/L could result from a limitation in the MIC determination method where one dilution step difference is permissible. It should therefore be considered during selection of suspected isolates. Except for one isolate, the presence of mcr-1 was not associated with a high level of resistance (MIC > 4 mg/L) to colistin and the presence of a chromosomal resistance mechanism in one of the isolates did not lead to elevated colistin MIC values either (MIC = 2 mg/L). There was a noted presence in Brazil of the mcr-1 gene in wild type isolates derived from poultry confirmed as never exposed to polymyxin during their entire lives (Lentz et al., 2016).

In some cases the lack of genotype–phenotype correlation in isolates with resistance genes but without phenotypic resistance to chloramphenicol could result from the limitation of the MIC method. In others the reason could be substitutions found in the relevant gene. In an isolate carrying the catB3 gene the lack of genotype–phenotype correlation could not be identified due to lack of a fragment gene at one end of the contig.

Despite several mcr-types and their variants being described in isolates from animals across Europe (Rebelo et al., 2018), our study suggests only mcr-1.1 being present in Polish livestock, the first cases dating back to 2011. For yet unknown reasons, but in concordance with data from Germany and France, the highest occurrence of mcr-1–positive E. coli was detected in turkeys (Irrgang et al., 2016; Perrin-Guyomard et al., 2016). We speculate it could be related to the longer life span of these animals compared to chickens, and consequently to a longer length of exposure to selective pressure favoring antibiotic resistance. Colistin is used for treatment of gastrointestinal infections in animals, but in some countries low doses may be used as a growth promoter (Kempf et al., 2013; Fernandes et al., 2016). However, this practice is not allowed in Poland or the other EU countries (European Medicine Agency [EMA] and European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption [ESVAC], 2017). The proliferation of mcr-1–carrying E. coli, only occasionally found in 2011 but reaching a case count of several dozen by 2016, raises the question of the effects of excessive colistin use in animal husbandry. Worth noting is that in Poland, unlike other animal species, most of the turkey population is raised from imported one-day-old poults or hatching eggs and it might be an additional way for resistant isolates to be introduced to Polish farm environments. Some research indicates that the introduction of resistant bacteria may have been through imported breeding animals (Mo et al., 2014).

Horizontal transfer via plasmids plays an important role in the dissemination of antibiotic resistance genes. The IncX4 plasmid is considered one of the most prevalent carriers of the mcr-1 gene in Enterobacteriaceae (Johnson et al., 2012; Matamoros et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2017). Our study showed that mcr-1 was associated with IncX4 plasmids in the vast majority (76.3%) of isolates, and with IncHI2 plasmids, another well-known mcr-1 vector (Matamoros et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2018) in a few (6.3%) isolates. The fact that in one sample two different E. coli were found with mcr-1 located on different plasmids (IncX4 and IncHI2) might evidence a parallel route of resistance spread but we cannot exclude transfer across the plasmids. Furthermore, occurrence of the mcr-1 gene on the chromosome shows that plasmid-mediated colistin resistance genes might become fixed into specific E. coli populations and spread vertically.

Most of the tested isolates were genetically unrelated, which has also been observed in other reports on mcr-1–positive E. coli (Veldman et al., 2016). One of the reported E. coli ST 10, identified in 3 isolates, has been previously described in relation to mcr-1 (Yang et al., 2017), and is considered a reservoir of this gene (Matamoros et al., 2017). The STs exhibited genetic diversity and were not related to animal source, geographic area, or isolation year. The identification of the same ST (i.e., ST919, ST354, and ST1564) in strains deriving from the same animal source but isolated in different years, or even in strains isolated from different species and in some cases harboring the mcr-1 gene on different plasmids proves the wide dissemination of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance over the whole country. The study shows, in the light of the ESVAC data on colistin sales (European Medicine Agency [EMA] and European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption [ESVAC], 2017), that the phenomenon is probably a result of wide colistin selection pressure and plasmid dissemination, and not due to the spread of specific bacterial clones (El Garch et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017). In Poland, sales of colistin still remain above the maximum sale target (European Medicine Agency [EMA] and European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption [ESVAC], 2018). External introduction, transmission of plasmids, and dissemination under selection pressure create the potential for the mcr-1 gene to become established in Polish food-producing animals.

Of significance is that almost all mcr-1.1–positive isolates were MDR including the compounds considered CIA (World Human Organization [WHO], 2017). They carried a range of genes encoding resistance to cephalosporins and quinolones. Some reports have demonstrated the presence of the mcr-1 gene together with ESBL genes (Robin et al., 2017; Yamaguchi et al., 2018). Therefore mcr-1–positive E. coli should be considered a reservoir not only of the colistin resistance gene, but also of those of PMQR, and ESBL or sets of other resistance genes carried along with mcr-1 on some plasmids. This is supported by our finding of the genes encoding for resistance to beta-lactams, including cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, or sulphonamides located on the same contig as mcr-1.1 and IncHI2 replicon. This is a serious concern for veterinary medicine and also for human health since direct transmission of resistant isolates from animals to humans has been confirmed (Marshall and Levy, 2011). The genes found in the current study did not differ from the ones identified previously in E. coli occurring in the healthy animal population (Wasyl, 2014; Lalak et al., 2016). The blaCTX–M–15 gene, which occurs in isolates responsible for nosocomial infections in Poland (Empel et al., 2008) was found in this study in only a single pig isolate.

The aEPEC (atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli) isolates are a cause of diarrhea in both humans and animals (Afset et al., 2004; Almeida et al., 2012). Here, in the collection of non-clinical E. coli isolates from healthy animals, we identified mcr-1.1 in a single chicken strain surprisingly carrying several virulence determinants of the aEPEC phenotype, namely EAST1, cell cycle inhibiting factor, intimin adherence protein Eae, secreted proteins EspA, EspB, and EspF type III secretion system effector NleB, Tir-cytoskeleton coupling protein, and translocated intimin receptor Tir. The strain carried also additional AMR genes combining to afford resistance to 4 classes. Since the mcr-1.1–positive, multidrug resistant aEPEC should be considered a vector of both resistance determinants and pathogens, this finding is worrisome for successive treatment of animals or humans.

Conclusion

The results highlight that poultry, especially turkeys, can be an important reservoir of mcr-1.1–carrying E. coli strains in Poland. Our findings indicate an increasing occurrence of mcr-1.1 in E. coli from turkeys and, to a lesser extent, chickens in Poland from 2011 to 2016, whereas cases in pigs and cattle appear to be sporadic in the study period. The mcr-1.1 gene occurred mainly on the IncX4 and IncHI2 plasmids in a wide diversity of E. coli harboring multiple resistance genes, virulence genes, and various plasmid replicons. Thus, dissemination of mcr-positive plasmids is a probable pathway for plasmid-mediated colistin resistance to spread in food-producing animals. The impressive genetic diversity of isolates as well as the association of colistin resistance with particularly relevant phenotypes (e.g., third-generation cephalosporin and fluoroquinolone resistance as well as aEPEC) call for urgent reduction in the use of colistin to avoid further selection of co-resistance in E. coli in animal production and possible animal and public health consequences. Definitely excluding isolates that are currently considered wild-type might contribute to silent dissemination of the mcr-positive ones. Great attention should be given to continuous phenotypic and genotypic surveillance of AMR and data collection in both human and veterinary settings, thus enabling intervention to counteract any rapid dissemination of mcr-1.1–positive E. coli.

Author Contributions

MZ and DW designed the experiments. MZ, PS, DW, and AZ-B analyzed the resistance and genotypic data. MZ, PS, and AZ-B prepared the tables and figures. MZ, PS, and DW prepared the manuscript. All authors discussed the results, reviewed and edited the manuscript, read, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the ENGAGE project (Grant No. GP/EFSA/AFSCO/2015/01/CT1).

Disclaimer

The conclusions, findings and opinions expressed in this scientific paper reflect only the view of the authors and not the official position of the European Food Safety Authority.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Aleksandra Giza, Arkadiusz Bomba, Ewelina Iwan, Magdalena Skarżyńska, Diana Soleniec, and Aleksandra Śmiałowska-Wȩglińska for their excellent technical assistance and numerous people involved in the field sampling and laboratory analyses performed over the years to gather materials for current study.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01753/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ http://bip.urpl.gov.pl/pl/biuletyny-i-wykazy/produkty-lecznicze-weterynaryjne

- ^ https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/

References

Abuoun, M., Stubberfield, E. J., Duggett, N. A., Kirchner, M., Dormer, L., Nunez-Garcia, J., et al. (2017). Mcr-1 and mcr-2 variant genes identified in Moraxella species isolated from pigs in great britain from 2014 to 2015. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 2745–2749. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx286

Afset, J. E., Bevanger, L., Romundstad, P., and Bergh, K. (2004). Association of atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) with prolonged diarrhoea. J. Med. Microbiol. 53, 1137–1144. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45719-0

Almeida, P. M. P., Arais L. R., Andrade, J. R. C., Prado, E. H. R. B., Irino, K., and Cerqueira, A. D. M. F. (2012). Characterization of atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (aEPEC) isolated from dogs. Vet. Microbiol. 158, 420–424, doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.02.021

Alneberg, J., Bjarnason, B. S., de Bruijn, I., Schirmer, M., Quick, J., Ijaz, U. Z., et al. (2014). Binning metagenomic contigs by coverage and composition. Nat. Methods 11, 1144–1146. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3103

Altschul, S. F., Gish W., Webb Miller W., Myers E. W., and Lipman D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

Apostolakos, I., and Piccirillo A. (2018). A review on the current situation and challenges of colistin resistance in poultry production, Avian Pathol. 47, 546–558. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2018.1524573

Bankevich, A., Nurk, S., Antipov, D., Gurevich, A. A., Dvorkin, M., Kulikov, A. S., et al. (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M., and Usadel, B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170

Borowiak, M., Fischer, J., Hammerl, J. A., Hendriksen, R. S., Szabo, I., and Malorny, B. (2017). Identification of a novel transposon-associated phosphoethanolamine transferase gene, mcr-5, conferring colistin resistance in d-tartrate fermenting Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar paratyphi B. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 3317–3324. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx327

Bushnell, B. (2018). BBTools. Available at: https://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/bbtools/ (accessed March 28, 2018).

Carattoli, A., Villa, L., Feudi, C., Curcio, L., Orsini, S., Luppi, A., et al. (2017). Novel plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mcr-4 gene in salmonella and Escherichia coli, Italy 2013, Spain and Belgium, 2015 to 2016. Eur. Surveill. 22:30589. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.31.30589

Carattoli, A., Zankari, E., Garcia-Fernandez, A., Voldby Larsen, M., Lund, O., Villa, L., et al. (2014). In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14

Carroll L. M., Gaballa A., Guldimann C., Sullivan G., Henderson L. O., and Wiedmann M. (2019). Identification of novel mobilized colistin resistance gene mcr-9 in a multidrug-resistant, colistin-susceptible Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium isolate. mBio 10:e00853-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00853-19

Cavaco L. M., Mordhorst H., Hendriksen R. S. (2016). PCR for Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance Genes: mcr-1 and mcr-2 (Multiplex). Denmark: Protocol optimized at National Food Institute.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2013). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States. Available at: https://www.statnews.com/2018/12/31/science-medicine-2019/ (accessed December 31, 2018).

Duggett, N. A., Sayers, E., AbuOun, M., Ellis, R. J., Nunez-Garcia, J., Randall, L., et al. (2017). Occurrence and characterization of mcr-1-harbouring Escherichia coli isolated from pigs in Great Britain from 2013 to 2015. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 691–695. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw477

European Food Safety Authority [EFSA] (2018). European Food safety authority, european centre for disease prevention and control. The european union summary report on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2016. EFSA J. 16:5182. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5182

El Garch,M., Hocquet, D., Lechaudee, D., Woehrle, F., and Bertrand, X. (2017). Mcr-1 is borne by highly diverse Escherichia coli isolates since 2004 in food-producing animals in Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 23, e51–e54. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.08.033

Empel, J., Baraniak, A., Literacka, E., Mrowka, A., Fiett, J., Sadowy, E., et al. (2008). Molecular survey of beta-lactamases conferring resistance to newer beta-lactams in Enterobacteriaceae isolates from Polish hospitals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 2449–2454. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00043-08

European Medicine Agency [EMA] and European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption [ESVAC] (2016). European Medicine Agency, European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption Updated Advice on the use of Colistin Products in Animals within the European Union: Development of Resistance and Possible Impact on Human and Animal Health. (EMA/CVMP/CHMP/231573/2016). Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2016/07/WC500211080.pdf (accessed July 2016).

European Medicine Agency [EMA] and European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption [ESVAC] (2017). European Medicine Agency, European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption. Sales of Veterinary Antimicrobial agents in 30 European Countries in 2015. Trends from 2010 to 2015. Seventh ESVAC report. (EMA/184855/2017). Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2017/10/WC500236750.pdf (accessed October 2017).

European Medicine Agency [EMA] and European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption [ESVAC] (2018). European Medicine Agency, European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption. Sales of Veterinary Antimicrobial agents in 30 European Countries in 2016. Trends from 2010 to 2016. Eighth ESVAC report. (EMA/275982/2018). Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/report/sales-veterinary-antimicrobial-agents-30-european-countries-2016-trends-2010-2016-eighth-esvac_en.pdf (accessed September 27, 2018).

Fernandes, M. R., Moura Q., Sartori L., Silva K. C., Cunha M. P. V., Esposito F., et al. (2016). Silent dissemination of colistin-resistant Escherichia coli in South America could contribute to the global spread of the mcr-1 gene. Eur. Surveill. 21:30214. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.17.30214

Grami R., Mansour W., Mehri W., Bouallegue O., Boujaafar N., Madec J. Y., et al. (2016). Impact of food animal trade on the spread of mcr-1-mediated colistin resistance, tunisia, July 2015. Eur. Surveill. 21:30144. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.8.30144

Gurevich, A., Saveliev, V., Vyahhi, N., and Tesler, G. (2013). QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29, 1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086

Hadjadj, L., Riziki, T., Zhu, Y., Li, J., Diene, S. M., and Rolain, J. M. (2017). Study of mcr-1 gene-mediated colistin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae isolated from humans and animals in different countries. Genes 8:E394. doi: 10.3390/genes8120394

Hartl, R., Kerschner, H., Lepuschitz, S., Ruppitsch, W., Allerberger, F., and Apfalter, P. (2017). Detection of the mcr-1 gene in a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolate from an austrian patient. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:AAC.2623-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02623-16

Hasman, H., Hammerum, A., Hansen, F., Hendriksen, R., Olesen, B., Agersø, Y., et al. (2015). Detection of mcr-1 encoding plasmid-mediated colistin-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from human bloodstream infection and imported chicken meat, Denmark 2015. Euro. Surveill. 20:30085. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.49.30085

Irrgang, A., Roschanski, N., Tenhagen, B. A., Grobbel, M., Skladnikiewicz-Ziemer, T., Thomas, K., et al. (2016). Prevalence of mcr-1 in E. coli from livestock and food in Germany, 2010-2015. PLoS One 11:e0159863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159863

Izdebski, R., Baraniak, A., Bojarska, K., Urbanowicz, P., Fiett, J., Pomorska-Wesolowska, M., et al. (2016). Mobile MCR-1-associated resistance to colistin in Poland. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71, 2331–2333. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw261

Joensen, K. G., Scheutz, F., Lund, O., Hasman, H., Kaas, R. S., Nielsen, E. M., et al. (2014). Real-time whole-genome sequencing for routine typing, surveillance, and outbreak detection of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 1501–1510. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03617-13

Johnson, T. J., Bielak, E. M., Fortini, D., Hansen, L. H., Hasman, H., Debroy, C., et al. (2012). Expansion of the IncX plasmid family for improved identification and typing of novel plasmids in drug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Plasmid 68, 43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2012.03.001

Lalak, A., Wasyl, D., Zając, M., Skarżyńska, M., Hoszowski, A., Samcik, I., et al. (2016). Mechanisms of cephalosporin resistance in indicator Escherichia coli isolated from food animals. Vet. Microbiol. 2, 69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.01.023

Lentz, S. A. M, de Lima-Morales, D., Cuppertino, V. M. L, de S Nunes, L., da Motta, A. S., Zavascki, A. P., et al. (2016). Letter to the editor: Escherichia coli harbouring mcr-1 gene isolated from poultry not exposed to polymyxins in Brazil. Eur. Surveill. 21, 1–2. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.26.30267

Letunic, I., and Bork, P. (2016). Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W242-W245. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw290

Li, X. P., Fang, L. X., Jiang, P., Pan, D., Xia, J., Liao, X. P., et al. (2017). Emergence of the colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in Citrobacter freundii. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 49, 786–787. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.04.004

Liu, Y. -Y., Wang, Y., Walsh, T. R., Yi, L. -X., Zhang, R., Spencer, J., et al. (2016). Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7

Kawanishi, M., Abo, H., Ozawa, M., Uchiyama, M., Shirakawa, T., Suzuki, S., et al. (2017). Prevalence of colistin resistance gene mcr-1 and absence of mcr-2 in Escherichia coli isolated from healthy food-producing animals in Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:e2057-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02057-16

Kempf, I., Fleury, M. A., Drider, D., Bruneau, M., Sanders, P., Chauvin, C., et al. (2013). What do we know about resistance to colistin in Enterobacteriaceae in avian and pig production in Europe? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents, 42, 379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.06.012

Kurtz, S., Phillippy, A., Delcher, A. L., Smoot, M., Shumway, M., Antonescu, C., et al. (2004). Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 5:R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12

Malhotra-Kumar, S., Xavier, B. B., Das, A. J., Lammens, C., Butaye, P., and Goossens, H. (2016). Colistin resistance gene mcr-1 harboured on a multidrug resistant plasmid. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 283–284. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00012-8

Marshall, B. M., and Levy S. B. (2011). Food animals and antimicrobials: impacts on human health. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 24, 718–733. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00002-11

Matamoros, S., van Hattem, J. M., Arcilla, M. S., Willemse, N., Melles, D. C., Penders, J., et al. (2017). Global phylogenetic analysis of Escherichia coli and plasmids carrying the mcr-1 gene indicates bacterial diversity but plasmid restriction. Sci. Rep. 7:15364. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15539-7

Mo, S. S., Norström, M., Slettemeås, J. S., Løvland, A., Urdahl, A. M., and Sunde, M. (2014). Emergence of AmpC-producing Escherichia coli in the broiler production chain in a country with a low antimicrobial usage profile. Vet. Microbiol. 171, 315–320. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2014.02.002

Olaitan, A. O., Morand S., and Rolain J. M. (2014). Mechanisms of polymyxin resistance: acquired and intrinsic resistance in bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 5:643. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00643

Perrin-Guyomard, A., Bruneau, M., Houee, P., Deleurme, K., Legrandois, P., Poirier, C., et al. (2016). Prevalence of mcr-1 in commensal Escherichia coli from French livestock, 2007 to 2014. Eur. Surveill. 21:30135. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.6.30135

Rebelo, A. R., Bortolaia, V., Kjeldgaard, J. S., Pedersen, S. K., Leekitcharoenphon, P., Hansen, I. M., et al. (2018). Multiplex PCR for detection of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance determinants, mcr-1, mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-4 and mcr-5 for surveillance purposes. Eur. Surveill. 23, 00617–00672. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.6.17-00672

Robin, F, Beyrouthy, R, Colot, J, Saint-Sardos, P, Berger-Carbonne, A, Dalmasso, G, Delmas, J, Bonnet, R. (2017). Mcr-1 in ESBL-producing Escherichia coli responsible for human infections in New Caledonia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 72, 946–947. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw508

Sun, J., Fang, L. X., Wu, Z., Deng, H., Yang, R. S., Li, X. P., et al. (2017). Genetic analysis of the IncX4 plasmids: implications for a unique pattern in the mcr-1 acquisition. Sci. Rep. 7:424. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00095-x

Sun, J., Li, X. P., Fang, L. X., Sun, R. Y., He, Y. Z., Lin, J., et al. (2018). Co-occurence of mcr-1 in the chromosome and incHI2 plasmid: persistence of colistin resistance in Escherichia coli. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 51, 842–847 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.01.007

Terveer, E. M., Nijhuis, R. H. T., Crobach, M. J. T., Knetsch, C. W., Veldkamp, K. E., Gooskens, J., et al. (2017). Prevalence of colistin resistance gene (mcr-1) containing Enterobacteriaceae in feces of patients attending a tertiary care hospital and detection of a mcr-1 containing, colistin susceptible E. coli. PLoS One 2:e0178598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178598

Tian, G. B., Doi, Y., Shen, J., Walsh, T. R., Wang, Y., Zhang, R., et al. (2017). MCR-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae outbreak in China. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17:577. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30266-9

Topfer, A. (2018). Lima - The PacBio Barcode Demultiplexer. Available at: https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/barcoding (accessed January 25, 2018).

Torpdahl, M., Hasman, H., Litrup, E., Skov, R. L., Nielsen, E. M., and Hammerum, A. M. (2017). Detection of mcr-1-encoding plasmid-mediated colistin-resistant Salmonella isolates from human infection in Denmark. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 49, 261–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.11.010

Veldman, K., van Essen-Zandbergen, A., Rapallini, M., Wit, B., Heymans, R., van Pelt, W., et al. (2016). Location of colistin resistance gene mcr-1 in Enterobacteriaceae from livestock and meat. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71, 2340–2342. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw181

Wang, Q., Sun, J., Li, J., Ding, Y., Li, X. P., Lin, J., et al. (2017). Expanding landscapes of the diversified mcr-1-bearing plasmid reservoirs. Microbiome 5:70. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0288-0

Wang, X., Wang, Y., Zhou, Y., Li, J., Yin, W., and Wang, S. (2018). Emergence of a novel mobile colistin resistance gene, mcr-8, in NDM-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Emerg. Microbes. Infect. 7:122. doi: 10.1038/s41426-018-0124-z

Wasyl, D. (2014). Prevalence and characterization of quinolone resistance mechanisms in commensal Escherichia coli isolated from slaughter animals in Poland, 2009-2012. Microb. Drug Resist. 20, 544–549. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2014.0061

World Human Organization [WHO] (2017). Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine. 5th Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization 1–48

Xavier, B. B., Lammens, C., Ruhal, R., Kumar-Singh, S., Butaye, P., Goossens, H., et al. (2016). Identification of a novel plasmid-mediated colistin-resistance gene, mcr-2, in Escherichia coli, Belgium. Eur. Surveill. 21:30280. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.27.30280

Yamaguchi, T., Kawahara, R., Harada, K., Teruya, S., Nakayama, T., Motooka, D., et al. (2018). The presence of colistin resistance gene mcr-1 and -3 in ESBL producing Escherichia coli isolated from food in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 365:fny100. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fny100

Yang, Y. Q., Li, Y. X., Song, T., Yang, Y. X., Jiang, W., Zhang, A. Y., et al. (2017). Colistin resistance gene mcr-1 and its variant in Escherichia coli isolates from chickens in China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e1204-e1216. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01204-16

Yang, Y. Q., Li, Y. X., Lei, C. W., Zhang, A. Y., and Wang, H. N. (2018). Novel plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-7.1 in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 73, 1791–1795. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky111

Yin, W., Li, H., Shen, Y., Liu, Z., Wang, S., Shen, Z., et al. (2017). Novel plasmid-mediated colistin resistance gene mcr-3 in Escherichia coli. mBio, 8:e543-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00543-17

Zankari, E., Hasman, H., Cosentino, S., Vestergaard, M., Rasmussen, S., Lund, O., et al. (2012). Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 2640–2644. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks261

Zhou, K., Luo, Q., Wang, Q., Huang, C., Lu, H., Rossen, J. W. A., et al. (2018). Silent transmission of an IS1294b-deactivated mcr-1 gene with inducible colistin resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 51, 822–828. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.01.004

Zhou, H. W., Zhang, T., Ma, J. H., Fang, Y., Wang, H. Y., Huang, Z. X., et al. (2017). Occurrence of plasmid- and chromosome-carried mcr-1 in waterborne Enterobacteriaceae in China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:AAC.00017-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00017-17

Keywords: WGS, mcr-1, colistin resistance, aEPEC, food animal, IncX4, IncHI2

Citation: Zając M, Sztromwasser P, Bortolaia V, Leekitcharoenphon P, Cavaco LM, Ziȩtek-Barszcz A, Hendriksen RS and Wasyl D (2019) Occurrence and Characterization of mcr-1-Positive Escherichia coli Isolated From Food-Producing Animals in Poland, 2011–2016. Front. Microbiol. 10:1753. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01753

Received: 29 November 2018; Accepted: 15 July 2019;

Published: 08 August 2019.

Edited by:

Rustam Aminov, University of Aberdeen, United KingdomReviewed by:

Ilias Apostolakos, University of Padua, ItalyJosé Luis Capelo, New University of Lisbon, Portugal

Copyright © 2019 Zając, Sztromwasser, Bortolaia, Leekitcharoenphon, Cavaco, Ziȩtek-Barszcz, Hendriksen and Wasyl. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Magdalena Zając, bWFnZGFsZW5hLnphamFjQHBpd2V0LnB1bGF3eS5wbA==

Magdalena Zając

Magdalena Zając Paweł Sztromwasser2

Paweł Sztromwasser2 Valeria Bortolaia

Valeria Bortolaia Pimlapas Leekitcharoenphon

Pimlapas Leekitcharoenphon Lina M. Cavaco

Lina M. Cavaco Rene S. Hendriksen

Rene S. Hendriksen