- 1Life Sciences and Technology, Microbiology, Beuth University of Applied Sciences, Berlin, Germany

- 2Institute of Biology, University Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany

- 3Institute of Biomedical Problems (IBMP), RAS, Moscow, Russia

The International Space Station (ISS) is a closed habitat in a uniquely extreme and hostile environment. Due to these special conditions, the human microflora can undergo unusual changes and may represent health risks for the crew. To address this problem, we investigated the antimicrobial activity of AGXX®, a novel surface coating consisting of micro-galvanic elements of silver and ruthenium along with examining the activity of a conventional silver coating. The antimicrobial materials were exposed on the ISS for 6, 12, and 19 months each at a place frequently visited by the crew. Bacteria that survived on the antimicrobial coatings [AGXX® and silver (Ag)] or the uncoated stainless steel carrier (V2A, control material) were recovered, phylogenetically affiliated and characterized in terms of antibiotic resistance (phenotype and genotype), plasmid content, biofilm formation capacity and antibiotic resistance transferability. On all three materials, surviving bacteria were dominated by Gram-positive bacteria and among those by Staphylococcus, Bacillus and Enterococcus spp. The novel antimicrobial surface coating proved to be highly effective. The conventional Ag coating showed only little antimicrobial activity. Microbial diversity increased with increasing exposure time on all three materials. The number of recovered bacteria decreased significantly from V2A to V2A-Ag to AGXX®. After 6 months exposure on the ISS no bacteria were recovered from AGXX®, after 12 months nine and after 19 months three isolates were obtained. Most Gram-positive pathogenic isolates were multidrug resistant (resistant to more than three antibiotics). Sulfamethoxazole, erythromycin and ampicillin resistance were most prevalent. An Enterococcus faecalis strain recovered from V2A steel after 12 months exposure exhibited the highest number of resistances (n = 9). The most prevalent resistance genes were ermC (erythromycin resistance) and tetK (tetracycline resistance). Average transfer frequency of erythromycin, tetracycline and gentamicin resistance from selected ISS isolates was 10−5 transconjugants/recipient. Most importantly, no serious human pathogens such as methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE) were found on any surface. Thus, the infection risk for the crew is low, especially when antimicrobial surfaces such as AGXX® are applied to surfaces prone to microbial contamination.

Introduction

The International Space Station is an isolated habitat in a hostile environment. Microgravity, solar and cosmic radiation alter the immune-regulatory responses of the crew rendering them more susceptible to bacterial infections (Sonnenfeld, 2005; Crucian et al., 2008; Guéguinou et al., 2009). The microorganisms in the spaceship are human-derived; they originate from the crew and helpers who prepare the mission. The spaceship provides a special environmental niche for microorganisms, which directly or indirectly affect the health, safety or performance of the crew (Taylor, 2015). Microgravity can affect the virulence (Nickerson et al., 2004; Wilson et al., 2007; Rosenzweig et al., 2010; Crabbé et al., 2011), growth kinetics (Klaus et al., 1997; Kacena et al., 1999; Nickerson et al., 2004) and biofilm formation of microorganisms (Mauclaire and Egli, 2010). To assess the risk microorganisms pose to astronauts, the composition and properties of microbial communities in spaceships were analyzed. Two hundred and thirty-four bacterial and fungal species were found on the MIR space station, among those strong biofilm formers. Staphylococcus spp., followed by Bacillus spp. and Corynebacterium spp. were abundant in air as well as in surface samples (Novikova, 2004; Novikova et al., 2006). Schiwon et al. (2013) analyzed ISS samples from air and crewmembers in-flight and post-flight. Bacillus spp., Staphylococcus spp. and Enterococcus spp. were the most prevalent. 75.8% of the isolates exhibited resistance to one or more antibiotics. Corresponding resistance genes were found in 86% of the antibiotic-resistant bacteria. In 86.2% of the isolates horizontal transfer genes were detected. Eighty-three percent of the isolates were able to form biofilms (Schiwon et al., 2013).

Under spaceflight conditions, bacteria were shown to exhibit enhanced secondary metabolite and extracellular polysaccharide production as well as enhanced biofilm formation (Mauclaire and Egli, 2010; Vukanti et al., 2012). In space, the cell wall of S. aureus was significantly thicker than in the same strain grown on Earth (Novikova et al., 2006; Taylor, 2015). Various bacteria exhibited enhanced virulence, increased antibiotic resistance and differential gene expression under space conditions (Horneck et al., 2010; Yamaguchi et al., 2014; Taylor, 2015). Thus, these bacteria could spread their virulence and/or antibiotic resistance genes through horizontal gene transfer (HGT) and turn harmless bacteria into potential pathogens.

HGT is mediated by mobile genetic elements (MGEs), such as conjugative plasmids, conjugative transposons, integron-specific gene cassettes, or phages that are able to facilitate their own transfer. Plasmid-mediated HGT plays a primordial role in the emergence of new pathogens (Frost et al., 2005; Garbisu et al., 2018). Schiwon et al. (2013) found conjugative plasmids in bacterial isolates from the ISS and could demonstrate that some of these strains were able to transfer their antibiotic resistance genes to other bacteria. The HGT rate was shown to be higher in microbial biofilms than in planktonic cultures (Holmes et al., 2015). Biofilms represent a protected mode of microbial growth and confer significant survival advantages in hostile environments (Li et al., 2007; Thallinger et al., 2013). Thus, biofilm forming organisms show increased resistance to antibiotics, either due to decreased penetration of the antibiotic through the biofilm matrix or due to expression of more complex biofilm-specific resistance mechanisms.

Multiple antibiotic resistant and strong biofilm forming Staphylococcus and Enterococcus isolates detected on the ISS could pose an increased health risk on the crew (Schiwon et al., 2013). Several studies report, that bacteria from astronauts in-flight were more resistant to antibiotics due to enhanced biofilm formation or changes in cell morphology, e.g., thicker cell walls than isolates obtained from the same individuals either pre- or post-flight. As medical aid on the ISS is restricted, there is an urgent need for new antimicrobial materials, which can be used there to prevent infections by multi-resistant biofilm forming bacteria.

Heavy metals, e.g., copper and silver, have been known for a long time to possess antimicrobial activity. Silver was officially approved as an antimicrobial agent in the twentieth century (Chopra, 2007; Schäberle and Hack, 2014; Guridi et al., 2015; Vaishampayan et al., 2018). However, after the discovery of antibiotics the use of metals to combat bacterial infections has declined (Chopra, 2007; Grass et al., 2011). Later on, due to the increased occurrence of antibiotic resistant pathogens, silver and copper have again found widespread use, both in medicine and in everyday life (Maillard and Hartemann, 2012; Warnes and Keevil, 2013; Schäberle and Hack, 2014). These metals are easy to use as coatings on a variety of substrates and have a lethal effect on bacteria and fungi via the so-called contact killing (Grass et al., 2011). Silver is one of the best-studied bactericidal agents in water supplies (Russell and Hugo, 1994; Rohr et al., 1999; Vonberg et al., 2008; Vaishampayan et al., 2018). However, as occurred with antibiotics, bacteria have also developed resistance mechanisms against silver (Gupta et al., 1999). Like the excessive use of antibiotics, the extended use of silver is questioned due to its toxicity to the environment as well as to the human body (Landsdown, 2010). Plain ruthenium is not applied as antibacterial agent, but antibacterial activity has been demonstrated for ruthenium(II) polypyridyl complexes (Bolhuis et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011, 2015).

Due to the increasing resistance of bacteria to both antibiotics and commonly used antimicrobial metals, there is an urgent need to develop new approaches to combat bacterial infections. A new antimicrobial surface coating is AGXX® consisting of micro-galvanic elements of the two noble metals, silver and ruthenium, surface-conditioned with ascorbic acid (Vaishampayan et al., 2018). Both metals can be galvanically applied to diverse surfaces such as stainless steel, plastics, or cellulose fibers. The coating proved to be active against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, but also against filamentous fungi, yeasts and some viruses (Guridi et al., 2015; Landau et al., 2017a,b; Vaishampayan et al., 2018). Recently, we demonstrated that it efficiently inhibits the growth of MRSA (Vaishampayan et al., 2018). The postulated mode of action is based on the formation of reactive oxygen species, particularly superoxide anions (Meyer, C., personal communication), which affect biomolecules, such as nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids. AGXX® has self-regenerating activity based on two coupled redox reactions taking place on the micro-galvanic silver and ruthenium elements on the surface of the material. They result in effective regeneration of the coating (Clauss-Lendzian et al., 2018).

In this study, we investigated the long-term antimicrobial effect of two different antimicrobial coatings. Three sets of V2A steel samples (uncoated, silver-coated, AGXX®-coated) were exposed and analyzed after six, 12, and 19 months on the ISS. Seventy-eight human pathogenic bacteria, which survived on the antimicrobial coatings or on the uncoated steel carrier (control) were phylogenetically affiliated and further characterized. The number of human pathogenic isolates decreased from V2A steel (n = 39) to V2A-Ag (n = 31) to V2A-AGXX® (n = 8). After 6 months of exposure, no bacteria survived on AGXX®, whereas six human pathogens were obtained after 12 and two after 19 months. From all materials, predominantly staphylococci and bacilli were isolated. Multi-antibiotic resistant, plasmid harboring staphylococcal and enterococcal ISS isolates transferred erythromycin, gentamicin and tetracycline resistance with average transfer frequencies of 10−5 transconjugants/recipient.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Antimicrobial Metal Sheets

The material was provided by Largentec GmbH, Berlin, Germany. V2A (DIN ISO 1.4301) stainless steel sheets were used as reference material and as base material for Ag and AGXX® coatings. The coatings were prepared as described in detail in Clauss-Lendzian et al. (2018). Prior to use in the experiments, the metal sheets (coated and uncoated) were autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min. The metal sheets had a size of 4 cm2 each and were placed on the door to the bathroom of the ISS. Three sets of test sheets, one for each time point, - time points 12 and 19 months thus representing a cumulative bacterial load—were exposed on the ISS.

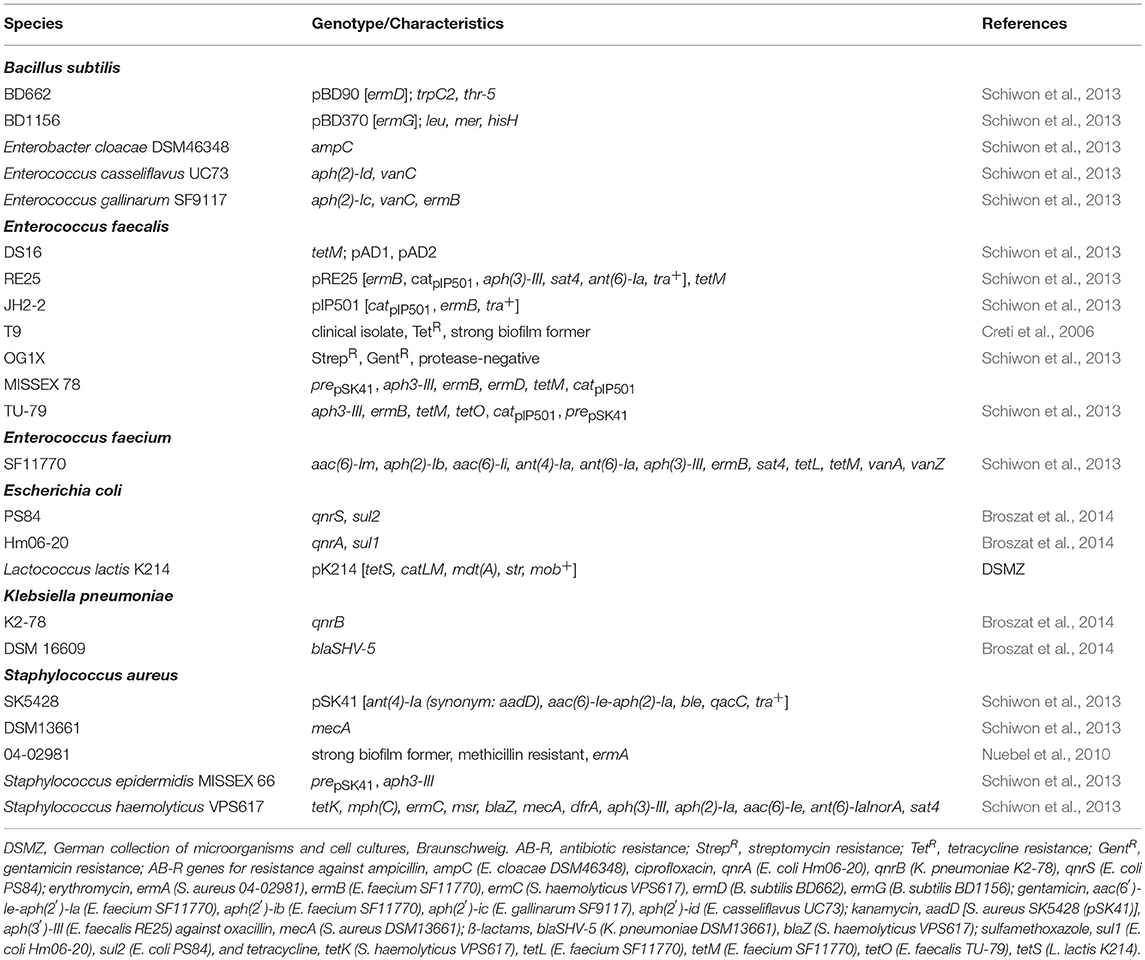

Reference Strains

Bacterial strains used as reference in biofilm formation assays and PCRs or as recipients in mating experiments are listed in Table 1. Staphylococcus and Enterococcus strains were grown in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB, Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Munich, Germany) or Brain Heart Infusion broth (Carl Roth GmbH & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany) at 37°C with shaking. Bacillus strains were grown in Lysogeny Broth (LB, Carl Roth GmbH & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany) at 30°C with shaking.

Table 1. Bacterial species used as references for AB-R-screening, biofilm formation, plasmid isolation, and in biparental mating.

Bacteria Isolation and Phylogenetic Affiliation

Bacteria were isolated from V2A steel surfaces (uncoated, Ag-coated, AGXX®-coated) exposed on the ISS for 6, 12 and 19 months, respectively. The bacteria were detached from the surfaces by rinsing with Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) followed by cultivation in Reasoner's 2A broth (R2A, Lab M Limited, Heywood, England) at 25° and 37°C under shaking. Appropriate dilutions of the cultures were passaged several times onto R2A agar until pure isolates were obtained. Isolates were phylogenetically affiliated by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS, Bruker Daltonics MALDI Biotyper system) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Bruker Daltonics). Mass spectra were compared with the MALDI-BDAL Database (Version 3.1, 7311rntries). If identification with MALDI-TOF MS failed, the isolate was sent for 16S rRNA gene sequencing (SMB Ruedersdorf, Germany). Analysis of the 16S rDNA sequences was performed with BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastn&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome) and ChromasPro (Version 2.1.8). The isolates are denominated according to following scheme (i) the material they were isolated from, (ii) the exposure time on the ISS in months, and (iii) the order of isolation, e.g., E. faecalis V2A-12-03 was isolated from uncoated V2A steel after 12 months exposure, and it is the third isolate obtained from this material at this time-point.

Biofilm Screening Assay

Biofilm formation test was carried out according to Vaishampayan et al. (2018). E. faecalis T9 and S. aureus 04-02981, both strong biofilm formers, were used as positive controls (Schiwon et al., 2013; Vaishampayan et al., 2018). For Staphylococcus spp., TSB, for E. faecalis, BHI medium was used as negative control (Schiwon et al., 2013). Biofilm formation was measured in EnSpire Multimode Plate Reader 2300-0000 (Perkin Elmer, Turku, Finland) at 570 nm (OD570). The assays were performed in triplicates. Normalized biofilm formation was calculated by dividing the biofilm measure at OD570 by the bacterial growth at OD600. Biofilm classification criteria were applied according to Nyenje et al. (2013).

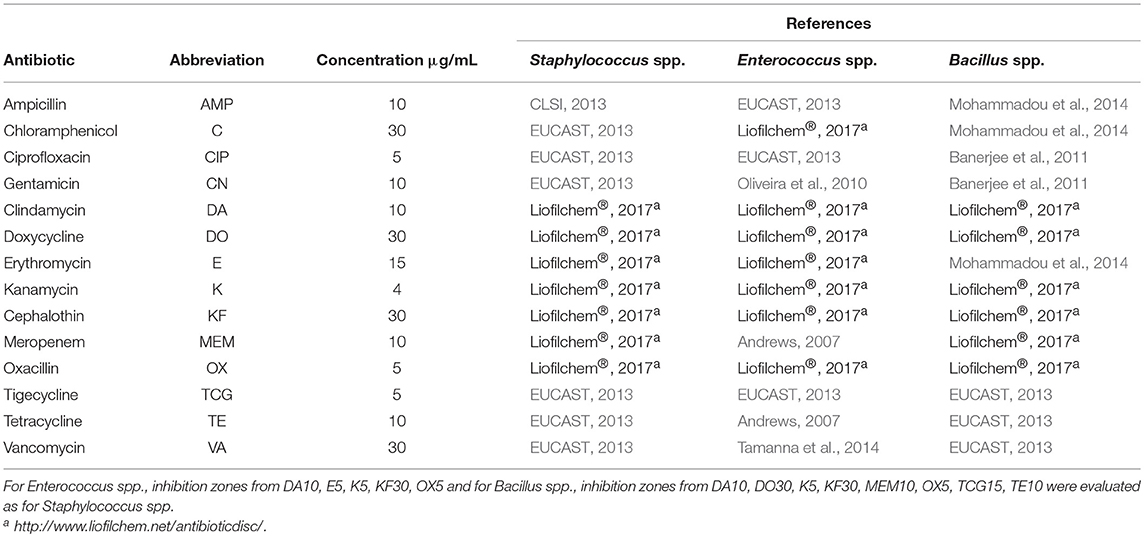

Antibiotic Disc Diffusion Method

Antibiotic resistance of the isolates toward 15 different antibiotics was analyzed with the disc diffusion method (discs from Oxoid, Wesel, Germany) on Mueller Hinton agar (Sifin diagnostic GmbH, Berlin, Germany) according to the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, (CLSI, 2013). Details are given in Table 2. Each test was performed in triplicates. For sulfamethoxazole (RL25), no comparable data were found for Staphylococci, Enterococci and Bacilli. Thus, isolates lacking an inhibition zone were classified as resistant, those without inhibition zone were classified as susceptible.

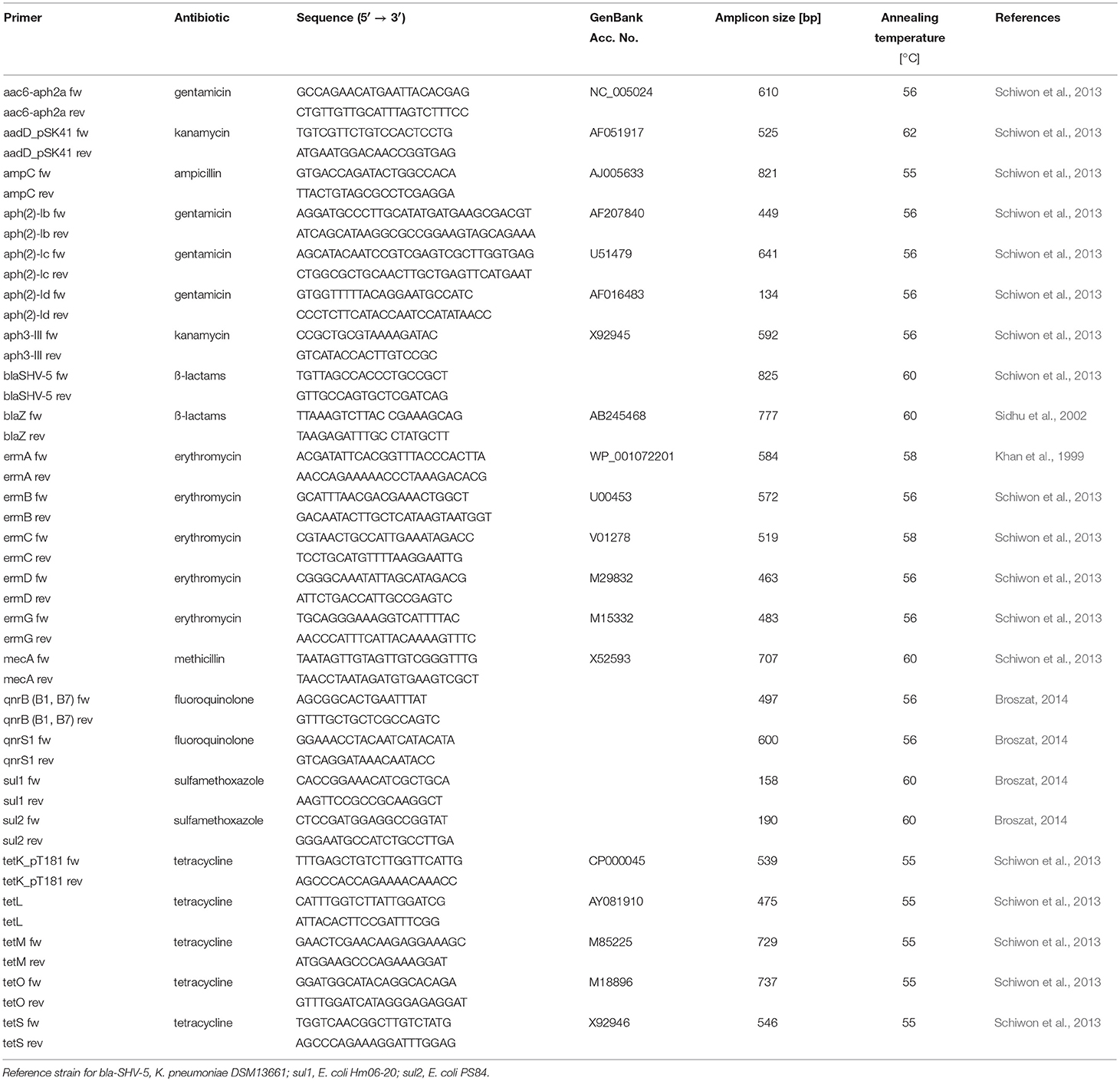

PCR Assays

For the PCR assays, cell lysates prepared from 100 μL overnight cultures were used. Cell pellets were re-suspended in 20 μL lysis buffer (50 mM NaOH, 0.25% sodium dodecyl sulfate) and incubated at 95°C for 20 min. Prior to use in PCR, they were diluted 1:10 with distilled water. Twenty-five microliter PCR reactions contained 0.125 μL Taq-Polymerase (5 U/μL), 2.5 μL 1x PCR buffer, 0.2 μM of each primer (Table 3), 0.5 μL of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (200 μM) and 1 μL template DNA (lysate). DNA amplifications were carried out in a Biometra T3 Thermocycler (Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany). The temperature profiles are given in Supplementary Table 1.

Plasmid DNA Isolation

Plasmid DNA from Staphylococci was extracted as described in Schiwon et al. (2013) with some minor modifications. After washing the plasmid DNA with 70% ethanol, 1 μL of RNase A (10 μg/mL; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt) and 3 μL of Proteinase K (20 mg/mL; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt) were added, followed by 1 h incubation at room temperature. Plasmid DNA extraction from Enterococci was performed as described in (Schiwon et al., 2013).

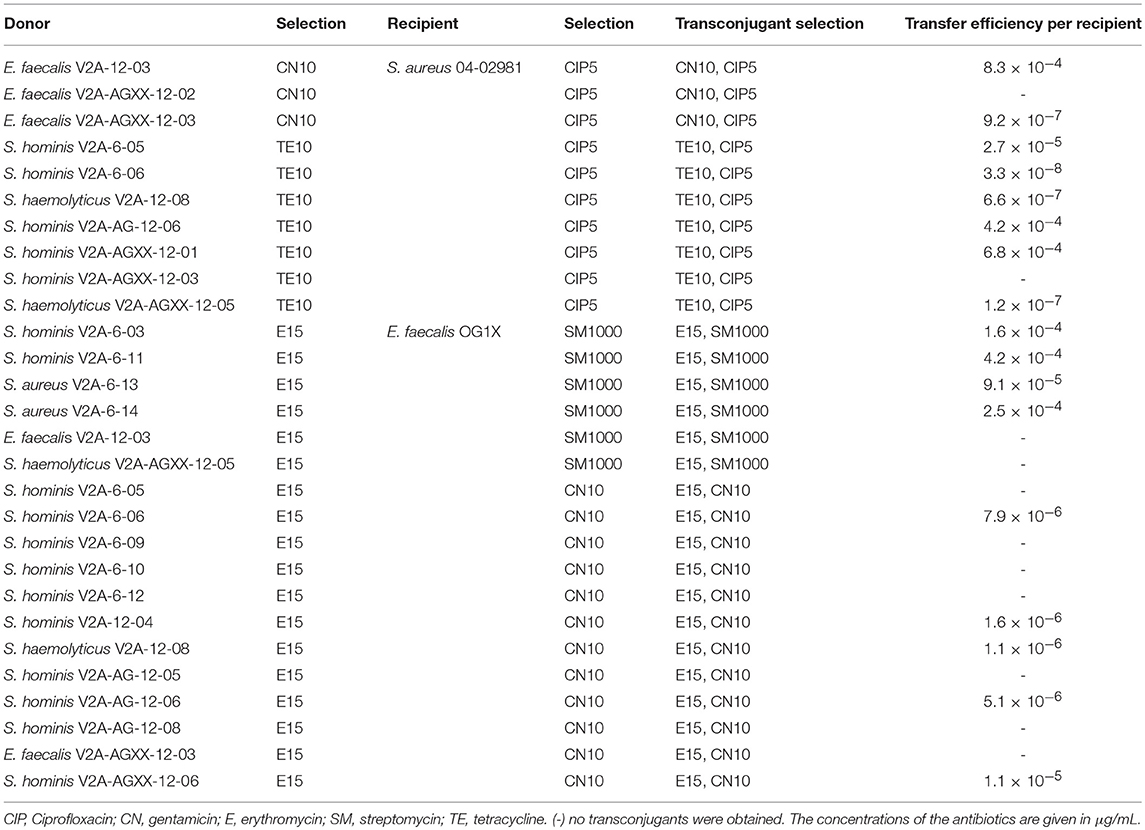

Mating Assays

On basis of multiple antibiotic resistance and occurrence of plasmids >20 kbp, ISS isolates were selected as donors for biparental matings. As recipients, the methicillin resistant clinical isolate, S. aureus 04-02981 and the E. faecalis lab strain OG1X were selected. Details on all of the matings are given in Table 4. Overnight cultures of Staphylococci were diluted 1:5 in TSB medium, overnight cultures of Enterococci 1:5 in BHI medium containing the appropriate antibiotics (Table 4) and grown until OD600 = 0.5. Donors and recipients were washed with PBS prior to mixing in 1:10 ratio, spotted onto a TSA plate for Staphylococcus recipients, on a BHI plate for Enterococcus recipients and incubated for 16 h at 37°C. Cells were recovered in 1 mL PBS, serial dilutions were incubated at 37°C on TSA/BHI plates for 16 h to enumerate transconjugants. The number of recipients was also determined after 16 h at 37°C. Transfer frequencies are given as number of transconjugants/recipient.

Table 4. Efficiency of gentamicin, erythromycin, and tetracycline resistance transfer from ISS-isolates to S. aureus 04-02981 and E. faecalis OG1X.

Results

Bacterial Isolates From V2A, V2A-Ag and V2A-AGXX® Surfaces

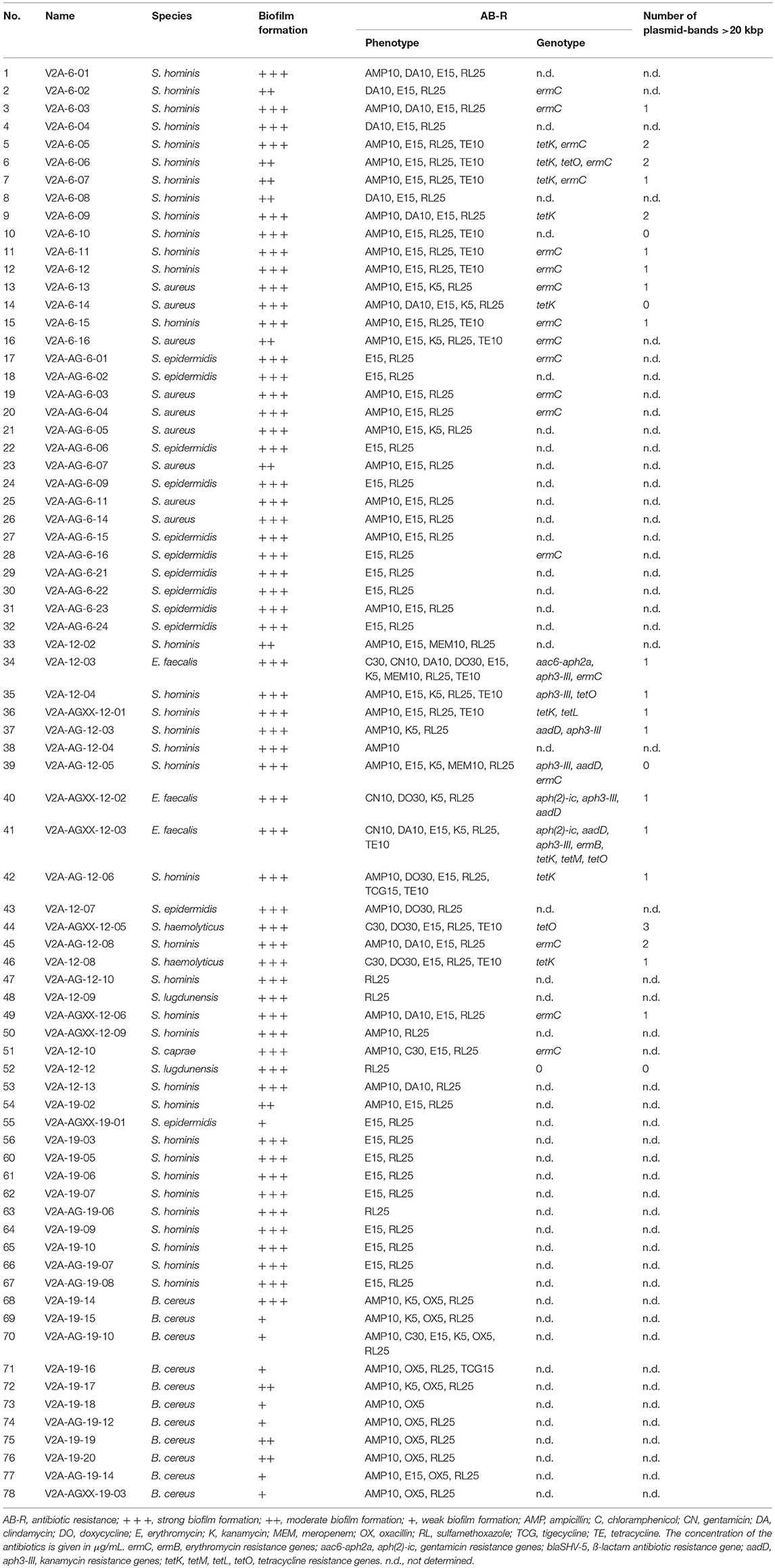

A total number of 112 bacterial isolates were recovered from the different materials after the three time intervals (6, 12, and 19 months). 73.6% of the isolates are human pathogens. All isolates were identified to species level by MALDI-TOF biotyping or 16S rRNA gene sequencing. In total, 49 isolates were obtained after 6 months, 51 after 12 months and 22 after 19 months exposure of the antimicrobial materials on the ISS. The non-human pathogenic bacteria include Bacillus spp. (n = 20; B. astrophaeus, B. infantis, B. korlensis, B. licheniformis, B. megaterium, B. niacini, B. pumilus, B. tequilensis, and B. thuringiensis), Enhydrobacter aerosaccus (n = 2), Micrococcus yunannensis (n = 1), Paenibacillus polymyxa (n = 1), Pseudomonas psychrotolerans (n = 1), and Staphylococcus capitis (n = 9). To assess the infection risk for the crew, only the human-pathogenic bacteria (n = 78) were characterized in terms of biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance profile. Three Moraxella osloensis strains obtained from V2A (n = 1) and V2A-Ag (n = 2) after 19 months were the only Gram-negative human-pathogenic bacteria. Seventy-five Gram-positive human pathogenic bacteria were selected for the study: 32 from 6 months, 21 from 12 months, and 22 isolates from 19 months exposure.

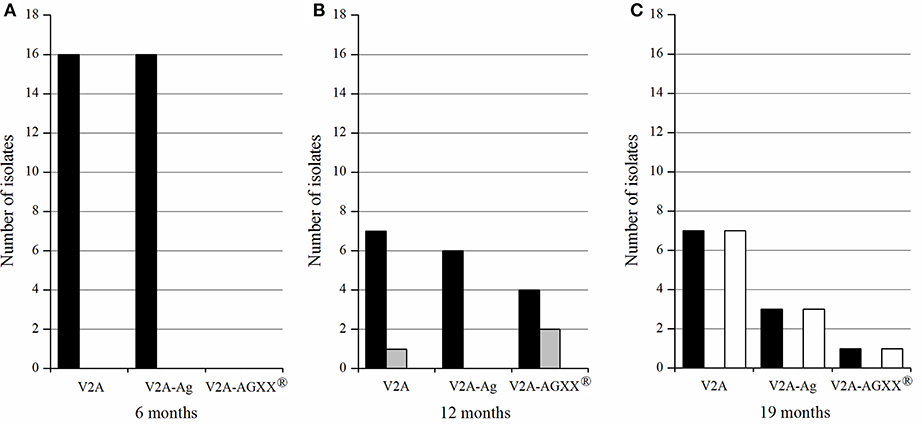

The longer the exposure time of the three materials, the higher was the bacterial diversity on the materials (Figure 1 and Table 5). All pathogenic isolates recovered from V2A and V2A-Ag after six months belonged to the genus Staphylococcus. No bacteria were recovered from AGXX® after 6 months. In total, 17 Staphylococci and three E. faecalis were detected after 12 months: Seven Staphylococci and one E. faecalis strain from V2A, six Staphylococci from V2A-Ag and four Staphylococci and two E. faecalis strains from AGXX®. After 19 months, seven Staphylococci and seven B. cereus strains were recovered from V2A and three Staphylococci and three B. cereus strains from V2A-Ag. Only one B. cereus and one S. epidermidis strain were isolated from AGXX® after 19 months exposure. In summary, a considerably lower bacterial number survived on AGXX® than on the other two surfaces. Nevertheless, the silver coating also showed a slight antimicrobial effect.

Figure 1. Number of Gram-positive pathogenic bacteria recovered from the different materials (V2A, V2A-Ag, V2A-AGXX®), after 6 months (A), 12 months (B), and 19 months (C) exposure on the ISS. In black, Staphylococcus spp.; gray, E. faecalis; white, B. cereus.

Biofilm Formation of Pathogenic ISS-Isolates

Biofilm formation of pathogenic isolates was determined by crystal violet staining, biofilms were classified according to Nyenje et al. (2013). The data are summarized in Table 5. Twenty-six V2A-isolates showed strong (66.7% of all pathogenic isolates from V2A-steel), ten moderate (25.5%) and three weak (7.8%) biofilm formation. Twenty-one isolates from V2A-Ag were strong biofilm formers (91.3% of all pathogenic isolates from V2-Ag), one isolate showed moderate (4.3%), one isolate weak (4.3%) biofilm formation. Of the eight AGXX®-isolates, six had strong (75.0% of all pathogenic isolates from V2A-AGXX®) and two (25%) weak biofilm formation ability. Interestingly, 43 Staphylococci (52 pathogenic Staphylococci in total) formed strong biofilms (82.7%), eight Staphylococci (15.4%) were moderate biofilm formers and one Staphylococcus isolate (1.9%) formed only weak biofilms. Of the B. cereus isolates (11 in total), one showed strong (9.1%), three moderate (27.3%), and seven (63.6%) showed only weak biofilm formation capacity. In contrast, all three E. faecalis isolates were classified as strong biofilm formers.

Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistances in the Pathogenic Isolates

Antibiotic sensitivity testing of the isolates showed that 32.0% of the pathogenic isolates were resistant to <3 of the tested antibiotics (15 antibiotics in total were tested), 68.0% were resistant to three or more antibiotics. Eighteen isolates had three antibiotic resistances (24.0% of the isolates), 23 isolates were resistant to four antibiotics (30.7% of the isolates), six isolates were resistant to five antibiotics (8.0%) and three isolates had six different antibiotic resistances (4.0%). E. faecalis V2A-12-03 (from V2A steel after 12 months) had the highest number of resistances. It was resistant to nine different antibiotics, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, clindamycin, doxycycline, erythromycin, kanamycin, meropenem, sulfamethoxazole, and tetracycline.

In total, 97.3% of the pathogenic Gram-positive isolates were resistant to 25 μg sulfamethoxazole, 74.7% were resistant to 15 μg erythromycin and 61.3% were resistant to 10 μg ampicillin. Interestingly, these resistances were found with similar prevalence on all three surfaces, irrespective of the exposure time. No oxacillin resistant Staphylococcus was detected, whereas all B. cereus isolates (all of the 11 isolates after 19 months) were resistant to oxacillin. One B. cereus (V2A-AG-19-10) isolate showed resistances against six different antibiotics (AMP10, C30, E15, K5, OX5, RL25).

None of the isolates was resistant to vancomycin or cephalothin. Two E. faecalis (V2A-AGXX-12-02,-03) isolates were resistant to six antibiotics (CN10, DA10, E15, K5, RL25, TE10) and one E. faecalis isolate (V2A-12-03) was resistant to nine antibiotics (C30, CN10, DA10, DO30, E15, K5, MEM10, RL25, TE10). Meropenem resistance was detected in three strains, E. faecalis V2A-12-03, S. hominis V2A-12-04, and S. hominis V2A-AG-12-05.

To identify the resistance genes in the isolates resistant to three or more antibiotics (68.0% of the pathogenic isolates), gene-specific PCRs were performed. Gentamicin [aac6-aph2a (n = 1), aph(2)-ic (n = 2)], kanamycin [aadD (n = 4), aph3-III (n = 5)], erythromycin [ermC (n = 19), ermB (n = 1)], and tetracycline [tetK (n = 9), tetL (n = 1), tetM (n = 1)] resistance genes were detected in the number of isolates indicated in parentheses (Table 5). ermC and tetK were the most prevalent resistance genes. No sulfamethoxazole (sul1, sul2) resistance gene was found in any of the isolates.

Plasmid Profiles of ISS-Isolates

Exemplarily, plasmid DNA profiles of 20 out of total 45 staphylococcal isolates resistant to three or more antibiotics forming moderate or strong biofilms were obtained (Table 5). All isolates contained plasmids <20 kbp, the number of plasmid bands varied from one to seven. Interestingly, 17 isolates harbored plasmids >20 kbp likely able to self-transfer. Plasmid DNA profiles were also obtained from the three E. faecalis isolates; all of them were multi-drug resistant and strong biofilm formers. All, E. faecalis V2A 12-03, E. faecalis V2A-AGXX-12-02 and E. faecalis V2A-AGXX-12-03 harbored putative conjugative plasmids >20 kbp. Interestingly, E. faecalis V2A 12-03 showed additionally three small plasmid bands in the size range between 3 and 1.5 kbp.

Mating Experiments

Antibiotic resistance transfer of selected ISS-isolates was studied in biparental matings (Laverde et al., 2017). Isolates resistant to tetracycline, gentamicin or erythromycin and harboring a plasmid >20 kbp were selected as donors, plasmid-free S. aureus 04-02981 and E. faecalis OG1X were used as recipients. The results of all of the matings are summarized in Table 4. Gentamicin resistance transfer to S. aureus 04-02981 was successful from E. faecalis V2A-12-03 (aac6-aph2a-encoded gentamicin resistance) with a transfer frequency of 8.3 × 10−4 transconjugants/recipient and from E. faecalis V2A-AGXX-12-03 (aph(2)-ic-encoded gentamicin resistance) with a transfer frequency of 9.2 × 10−7 transconjugants/recipient.

Erythromycin resistance transfer of six Staphylococcus donors harboring the ermC resistance gene and of three Staphylococcus donors harboring an unknown erythromycin resistance gene to E. faecalis OG1X was successful with transfer frequencies in the range of 1.1 × 10−6 to 4.2 × 10−4 transconjugants/recipient. Tetracycline resistance transfer from four S. hominis strains and two S. haemolyticus strains to S. aureus 04-02981 was successful. Three of the staphylococci harbored only the tetK resistance gene, one only tetO. One S. hominis strain harbored tetK and tetO, while another harbored the resistance genes tetK and tetL. Tetracycline resistance transfer frequencies varied considerably ranging from 3.3 × 10−8 to 6.8 × 10−4 transconjugants/recipient.

Ten out of the 17 successful matings were randomly chosen for plasmid DNA isolation of the transconjugants. In nine of the ten matings large plasmid bands comparable in size to those of the donors were detected in the transconjugants (data not shown).

Discussion

We proved that the novel antimicrobial coating AGXX® strongly reduced the bacterial load on surfaces on the ISS particularly prone to microbial contamination. However, over time—with exposure times >6 months—some nosocomial pathogens survived even on the novel antimicrobial coating. Moreover, an interesting shift in the composition of the microbial communities was observed over time.

Bacterial Survivors Isolated From V2A, V2A-Ag and V2A-AGXX® Surfaces

The bacterial community isolated from the surfaces was always dominated by Staphylococcus spp. (63.4% of 112 isolates) and Bacillus spp. (24.1%) irrespective of the exposure time. 46.4% of the Staphylococci are affiliated to the coagulase-negative Staphylococci, including pathogens such as S. epidermidis, S. lugdunensis, S. haemolyticus, S. hominis, and S. caprae. Coagulase-positive Staphylococci such as S. aureus (8.9% of all isolates) were only found on V2A and V2A-Ag surfaces after 6 months exposure. B. cereus (9.8% of all isolates) was the only pathogenic Bacillus. Only three E. faecalis (2.7% of all isolates) were recovered from V2A and V2A-AGXX® surfaces after 12 months. Schiwon et al. reported that predominantly S. hominis, S. aureus, and S. epidermidis were detected on crew-members and in air-filters on the ISS (Schiwon et al., 2013). S. hominis and S. epidermidis were the most prevalent Staphylococci associated with debris collected from the crew's quarters on the ISS (Venkateswaran et al. (2014). In addition, 13 E. faecalis and eight B. cereus strains were isolated from the crew and air-filters on the ISS (Schiwon et al., 2013). Taking the data of this study and others together (Van Houdt et al., 2012; Schiwon et al., 2013; Venkateswaran et al., 2014; Mayer et al., 2016) it can be concluded that the bacteria that survived on the different surfaces were predominantly human-associated.

Microbial diversity on the test materials increased over time. After 6 months only Staphylococci and Bacilli were found, after 12 months Staphylococci, Bacilli, E. faecalis and one P. polymyxa strain were isolated while after 19 months, Staphylococci, Bacilli, E. aerosaccus, M. osloensis, M. yunnanensis, and P. psychrotolerans were recovered. Novikova (2004) reported a similar diversity on surfaces on the MIR station including Staphylococci, Bacilli, Micrococcus, Moraxella, and Pseudomonas.

A decline of the number of Gram-positive human-pathogens recovered from V2A (n = 39) to V2A-Ag (n = 28) to V2A-AGXX® (n = 8) was observed. In total, only 12 bacteria were recovered from AGXX®-coated surfaces after 12 and 19 months exposure. AGXX® showed a pronounced antimicrobial effect, it reduced the microbial load by 79.5%. Silver also had a slight antimicrobial effect, it reduced the microbial load by 28.2%.

The antimicrobial test-materials are static surfaces, where dead cells, dust particles and cell debris can deposit. These deposits might interfere with the direct contact between the antimicrobial surface and the bacteria, which is required for effective antimicrobial activity of contact catalysts, such as Ag and AGXX®. Over time the deposits might have grown in size and thickness resulting in increasing interference with the antimicrobial activity. Possibly, this effect could explain that after 6 months no bacteria were recovered from AGXX®, whereas with prolonged exposure time a few bacteria escaped the antimicrobial action.

Strong Biofilm Forming ISS Isolates

Biofilms provide microbes shelter from antimicrobials and the host immune system (Foulquié Moreno et al., 2006; Chen and Wen, 2011; Rafii, 2015; Qi et al., 2016; Hall and Mah, 2017). Bacterial biofilms have been associated with diseases such as cystic fibrosis, periodontitis, and nosocomial infections on catheters and prosthetic heart valves (Storti et al., 2005; Delle Bovi et al., 2011). Eradication of biofilms is difficult due to impaired penetration of antibiotics and the decreased host immune response. Thus, they can pose a health risk to immunosuppressed people, such as the crew on the ISS.

Most Staphylococcus and all Enterococcus isolates from this study formed strong biofilms. B. cereus isolates were more diverse in terms of biofilm formation: Seven isolates produced a weak, three a moderate and only one produced a strong biofilm. The fact that all bacterial isolates were able to form biofilms could be due to the long exposure to adverse space conditions.

Prevalence of Antibiotic Resistances in Human Pathogenic Isolates

Astronauts have a suppressed immune response in-flight and as a consequence they are more susceptible to bacterial infections (Van Houdt et al., 2012; Taylor, 2015). The potential infection by pathogenic Staphylococci and Enterococci increases with duration of the mission (Schiwon et al., 2013). Therefore, treatability of bacterial infections on the ISS and on even longer space missions with limited amounts of antimicrobial drugs available is a health concern which has to be tackled.

In this study, all Gram-positive pathogenic isolates were resistant to at least one antibiotic. 68.0%, mostly Staphylococci, were multidrug resistant (resistant to more than three antibiotics). After 12 months exposure, also multi-resistant Enterococci occurred, one E. faecalis strain from V2A steel and two E. faecalis strains from V2A-AGXX®. E. faecalis V2A-12-03 had with nine resistances the largest number of resistances.

In total, the isolates were tested against 15 different antibiotics. Seven different antibiotic resistances were found after 6 months, 13 after 12 months and after 19 months, the number of resistances equalled the number after 6 months. This could be partly due to the fact, that the number of resistances in the Staphylococci declined after 19 months (most isolates had only one or two resistances), while Bacillus strains with more than three resistances came up.

All Staphylococci had similar antibiotic resistance profiles. The B. cereus isolates after 19 months exposure also showed similar resistance profiles. Most Bacilli and Staphylococci were resistant to ampicillin and erythromycin. Gentamicin resistance only occurred in E. faecalis isolates. Interestingly, all of them were also resistant to kanamycin. E. faecalis strains are known to be intrinsically resistant to low-level aminoglycosides (gentamicin, kanamycin) or have acquired high-level aminoglycoside resistance e.g., by uptake of aac6-aph2a or aph(2)-ic (Chow, 2000; Wendelbo et al., 2003; Dadfarma et al., 2013). As E. faecalis V2A-12-03 encodes aac6-aph2a and E. faecalis V2A-AGXX-12-02 and−03 encode aph(2)-ic, they are likely high level gentamicin resistant. aac6-aph2a was found on plasmids pSK41, pGO1, pLW1043, pSK1, pTEF1, on Tn4001-like transposons and on the chromosome (Schiwon, 2011). aph(2)-ic was found on conjugative plasmid pYN134 (Hollenbeck and Rice, 2012) in E. gallinarum but was shown to readily transfer to E. faecalis (Chow et al., 1997). Therefore, it is likely that gentamicin resistance spreads via these conjugative plasmids (Chow et al., 1997).

Most ISS-isolates were resistant to sulfamethoxazole, which interferes with bacterial synthesis of folic acid. It could be speculated that changes in the thickness of the cell wall due to exposure to space conditions might be involved in resistance to sulfamethoxazole by inhibiting the uptake of the antibiotic.

Most abundant resistance genes in the ISS-isolates were ermC and tetK coding for erythromycin and tetracycline resistance, respectively. Both genes are plasmid-borne and have been detected in Staphylococci of human origin (Schiwon et al., 2013). ermC was found on pSK41-like conjugative plasmid pUSA03 isolated from the community-acquired MRSA strain USA300 (Grohmann et al., 2003; Smillie et al., 2010; Schiwon et al., 2013). A pSK41-like plasmid could have spread ermC among the S. aureus strains V2A-6-13 and V2A-6-16, and between V2A-AG-6-03 and V2A-AG-6-04 isolated from the same material. Indeed, from S. aureus V2A-6-16 a plasmid >20 kbp was isolated. ermB is another plasmid-encoded erythromycin resistance gene. It is one of the 33 erythromycin resistance genes found in Staphylococci (Schiwon et al., 2013). However, ermB is not abundant in Staphylococci. No ISS-isolate from crew and air-filters harbored ermB (Zmantar et al., 2011; Schiwon et al., 2013). Also in this study, only E. faecalis V2A-AGXX-12-03 encoded ermB. De Leener et al. (2005) reported that ermB is present on Tn1545-like elements and that is likely associated with the occurrence of the tetracycline-resistance gene tetM. Interestingly, E. faecalis V2A-AGXX-12-03 harbored tetM along with ermB.

tetK is found on small mobilizable plasmids, which can be integrated into the Staphylococcus chromosome or into larger staphylococcal plasmids (Gillespie et al., 1987; Needham et al., 1994; Roberts, 2005). tetO and tetK can be found on pT181-like small mobilizable plasmids (Khan and Novick, 1983; Chopra and Roberts, 2001). S. hominis V2A-AGXX-12-01 (tetK, tetO) and S. haemolyticus V2A-AGXX-12-05 (tetK) likely carry pT181-like plasmids as small plasmid bands in the range of 2000–6000 bp were observed on the gel (data not shown). Both strains were isolated from the same material after the same time-period. Thus, the resistance genes might have spread via HGT among them. Along with tetK, pT181-like plasmids can carry tetL as well (Chopra and Roberts, 2001). Both genes were found in S. hominis V2A-AGXX-12-01.

Kanamycin resistance occurred both in Staphylococci and Enterococci. The kanamycin-resistance gene aph3-III was found in S. hominis V2A-12-04, S. hominis V2A-AG-12-05 and E. faecalis V2A-12-03, E. faecalis V2A-AGXX-12-02, and E. faecalis V2A-AGXX-12-03, all isolated from V2A and the two antimicrobial surfaces after 12 months. aph3-III is located on transposons of the Tn916-Tn1545 type encoding a broad spectrum of resistances, toward tetracycline, macrolides, lincosamides, streptogramins, and kanamycin (Fons et al., 1997; Soge et al., 2008; Roberts and Mullany, 2011). The kanamycin-resistance gene aadD was detected in S. hominis V2A-AG-12-03, V2A-AG-12-05 and in E. faecalis V2A-AGXX-12-02 and V2A-AGXX-12-03. aadD is encoded on S. aureus plasmid pUB110 (4548 bp) (McKenzie et al., 1986; Allignet et al., 1998). As the two S. hominis and two E. faecalis strains were isolated from the same materials, V2A-Ag and V2A-AGXX®, respectively, transfer of the aadD gene might have taken place. S. hominis V2A-AG-12-05 showed plasmid-bands in the range of 2000-3000 bp and around 7000 bp likely indicating the presence of pUB110-like plasmids (data not shown). Occurrence of aph3-III and aadD genes in Staphylococcus and Enterococcus isolates from the ISS has already been reported (Schiwon et al., 2013).

Antibiotic Resistance Transfer of the ISS-Isolates

Plasmids are the key players in HGT of antibiotic resistances (Kohler et al., 2018). Twenty multidrug-resistant, biofilm forming human-pathogenic staphylococcal isolates obtained from the three different materials after 6, 12, and 19 months were applied to plasmid DNA isolation. All isolates harbored plasmids <20 kbp and 17 of them also harbored plasmids >20 kbp. Commonly, S. aureus strains contain one or more plasmids ranging in size from <2000 bp to >60 kbp (Kwong et al., 2008).

Fourteen of the 17 Staphylococcus isolates with large plasmids were applied as donors to biparental matings to test the transferability of tetracycline and erythromycin resistance. In total, six out of seven tetracycline resistance transfer experiments (S. hominis V2A-6-05, S. hominis V2A-6-06, S. haemolyticus V2A-12-08, S. hominis V2A-AG-12-06, S. hominis V2A-AGXX-12-01, and S. haemolyticus V2A-AGXX-12-05) were successful whereas nine out of 18 erythromycin resistance transfer experiments (S. hominis V2A-6-03, S. hominis V2A-6-06, S. hominis V2A-6-11, S. aureus V2A-6-13, S. aureus V2A-6-14, S. hominis V2A-12-04, S. haemolyticus V2A-12-08, S. hominis V2A-AG-12-06, and S. hominis V2A-AGXX-12-06) were successful. Thus, these nine isolates likely harbor conjugative elements encoding erythromycin resistance. Indeed, in E. faecalis OG1X transconjugants of four of these matings large plasmids similar in size to those of the donors were found. pSK41 (46.4 kbp) and pUSA03 (37 kbp) are well known staphylococcal conjugative plasmids. Both carry ermC (Berg et al., 1998; Kennedy et al., 2010; Smillie et al., 2010) which was also detected in five of the successful donors.

Tetracycline resistance transfer frequencies from S. hominis V2A-6-05 (tetK), S. hominis V2A-6-06 (tetK, tetO), S. haemolyticus V2A-12-08 (tetK), S. hominis V2A-AG-12-06 (tetK), S. hominis V2A-AGXX-12-01 (tetK, tetL), S. haemolyticus V2A-AGXX-12-05 (tetO) to S. aureus 04-02891 ranged from 1.2 × 10−7 to 6.8 × 10−4 transconjugants/recipient. tetK is only rarely found on large staphylococcal plasmids. It is rather encoded on small mobilizable staphylococcal plasmids in the size range of 4.4 to 4.7 kbp, such as pT181 (Chopra and Roberts, 2001). Thus, in the successful matings with donors harboring tetO or tetK mobilizable pT181-like plasmids might have played a role in the transmission of the resistance to S. aureus 04-02981. As pT181 is non self-transmissible another conjugative element has participated in the transfer of the tetracycline resistance. All donors that were successful in the tetracycline resistance matings contained in addition to plasmid-bands <20 kbp at least one plasmid-band >20 kbp, which could represent the conjugative plasmid. Thus, it is likely that the successful donors harbor a pT181-like plasmid which was transferred by the help of a conjugative plasmid. Indeed, in S. aureus 04-02981 transconjugants from all of those matings large plasmids similar in size to those of the donors were detected. In addition, small plasmids in the size range of pT181-like plasmids were found in transconjugants of three of these matings.

Transfer frequency of gentamicin resistance (8.3 × 10−4 transconjugants/recipient) from E. faecalis V2A-12-03 (aac6-aph2a) to S. aureus 04-02891 was higher than from E. faecalis V2A-AGXX-12-03 (aph(2)-ic) to the same recipient (9.2 × 10−7 transconjugants/recipient). aac6-aph2a can be found on conjugative plasmids, such as pSK41, pGO1, pLW1043, pSK1, pTEF1, Tn4001-like transposons but also on the chromosome (Schiwon, 2011). The uptake of aac6-aph2a by S. aureus 04-02891 indicates that E. faecalis V2A-12-03 likely harbors one of these conjugative elements. Indeed, this observation was corroborated by isolation of a plasmid >20 kbp from E. faecalis V2A-12-03. aph(2)-ic was found on the 34-kbp conjugative plasmid pYN134 (Chow et al., 1997; Hollenbeck and Rice, 2012). The uptake of aph(2)-ic by S. aureus 04-02891 suggests that E. faecalis V2A-AGXX-12-03 likely harbors a pYN134-like plasmid. This argument was corroborated by the observation of a plasmid band >20 kbp for E. faecalis V2A-AGXX-12-03.

The data of this study confirm erythromycin and tetracycline resistance transfer in ISS-isolates from air-filters and the crew as reported by Schiwon et al. (2013). Further transfer studies between ISS-isolates could deepen our knowledge in the transmissibility of antibiotic resistances. However, no methicillin resistant Staphylococci and no vancomycin resistant enterococci were found. Thus, the generation of serious multi-resistant pathogens by horizontal transfer is unlikely.

Further Applications of the Antimicrobial Surface

AGXX® proved to be a long-term efficient antimicrobial, even under the harsh conditions on the ISS. The antimicrobial coating has been also successfully applied against other Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens. It also strongly reduced the bacterial load of Legionella and the highly pathogenic Shiga toxin-producing E. coli O104:H4 strain (Guridi et al., 2015). It is available in diverse application forms, such as powders, thin sheets, as coating on diverse plastic materials and on cellulose fleece and will be recently tested in the 4 months SIRIUS isolation study for future lunar flights.

Data Availability

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the supplementary files.

Author Contributions

EG designed the project and supervised all the experiments. L-YS, KR, JF, WS, PO, and AV performed the experiments. L-YS, KR, and EG wrote the manuscript and designed the figures and tables. NN provided us access to the BIORISK experiment on the ISS and contributed with insightful discussions on the experimental design. All authors read and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the Russian Academy of Science (Topic # 65.5).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank U. Landau and C. Meyer from Largentec GmbH, Berlin, for providing us with the antimicrobial materials and for helpful discussions. We thank Zeliha Kaban, Ghazoua Cheibi and Maxim Gabor Bogisch for their help with the strain collection and Ali Younes for helping with plasmid DNA isolations. Funding by DLR, German Aerospace Center (grants 50WB1166 and 50WB1466 to EG) is acknowledged.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00543/full#supplementary-material

References

Allignet, J., Liassine, N., and El Solh, N. (1998). Characterization of a staphylococcal plasmid related to pUB110 and carrying two novel genes, vatC and vgbB, encoding resistance to streptogramins A and B and similar antibiotics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 42, 1794–1798. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.7.1794

Andrews, J. M. (2007). BSAC standardized disc susceptibility testing method (version 6). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60, 20–41. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm110

Banerjee, M., Nair, G. B., and Ramamurthy, T. (2011). Phenotypic & genetic characterization of Bacillus cereus isolated from acute diarrhoeal patients. Ind. J. Med. Res. 113, 88–95.

Berg, T., Firth, N., Apisiridej, S., Hettiaratchi, A., Leelarporn, A., and Skurray, R. A. (1998). Complete nucleotide sequence of pSK41: evolution of staphylococcal conjugative multiresistance plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 180, 4350–4359.

Bolhuis, A., Handa, L., Marshalla, J. E., Richards, A. D., Rodger, A., and Aldrich-Wright, J. (2011). Antimicrobial activity of ruthenium-based intercalators. Eur. J. Pharmaceut. Sci. 42, 313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.12.004

Broszat, M. (2014). Verbreitung von Antibiotikaresistenzen und pathogenen Bakterien sowie Untersuchungen zu horizontalem Gentransfer in Abwasserrieselfeldern des Mezquital Valley in Mexiko. dissertation thesis, Albert-Ludwigs-University, Freiburg im Breisgau.

Broszat, M., Nacke, H., Blasi, R., Siebe, C., Hübner, J., Daniel, R., et al. (2014). Amplicon sequencing and resistance gene pool of bacterial communities from wastewater-irrigation fields in the Mezquital Valley, Mexico. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 5282–5291. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01295-14

Chen, L., and Wen, Y. (2011). The role of bacterial biofilm in persistent infections and control strategies. Int. J. Oral Sci. 3, 66–73. doi: 10.4248/IJOS11022

Chopra, I. (2007). The increasing use of silver-based products as antimicrobial agents: a useful development or a cause for concern? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 59, 587–590. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm006

Chopra, I., and Roberts, M. (2001). Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65, 232–260. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.65.2.232-260.2001

Chow, J. W. (2000). Aminoglycoside resistance in enterococci. Clin. Infect. Dis. 31, 586–589. doi: 10.1086/313949

Chow, J. W., Zervos, M. J., Lerner, S. A., Thal, L. A., Donabedian, S. M., Jaworski, D. D., et al. (1997). A novel gentamicin resistance gene in Enterococcus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41, 511–514. doi: 10.1128/AAC.41.3.511

Clauss-Lendzian, E., Vaishampayan, A., de Jong, A., Landau, U., Meyer, C., Kok. J, et al. (2018). Stress response of a clinical Enterococcus faecalis isolate subjected to a novel antimicrobial surface coating. Microbiol. Res. 207, 53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2017.11.006

CLSI (2013). M100-S23 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Third Informational Supplement. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 487.

Crabbé, A., Schurr, M. J., Monsieurs, P., Morici, L., Schurr, J., Wilson, J. W., et al. (2011). Transcriptional and proteomic responses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 to spaceflight conditions involve Hfq regulation and reveal a role for oxygen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 1221–1230. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01582-10

Creti, R., Koch, S., Fabretti, F., Baldassarri, L., and Huebner, J. (2006). Enterococcal colonization of the gastro-intestinal tract: role of biofilm and environmental oligosaccharides. BMC Microbiol. 6:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-60

Crucian, B. E., Stowe, R. P., Pierson, D. L., and Sams, C. F. (2008). Immune system dysregulation following short- vs long-duration spaceflight. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 79, 835–843. doi: 10.3357/ASEM.2276.2008

Dadfarma, N., Imani Fooladi, A. A., Oskoui, M., and Mahmoodzadeh Hosseini, H. (2013). High level of gentamicin resistance (HLGR) among Enterococcus strains isolated from clinical specimens. J. Infect. Public Health. 6, 202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2013.01.001

De Leener, E., Martel, A., Decostere, A., and Haesebrouck, F. (2005). Distribution of erm(B) gene, tetracycline resistance genes, and Tn1524-like transposons in macrolide- and lincosamide-resistant enterococci from pigs and humans. Microb. Drug Resist. 10, 341–345. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2004.10.341

Delle Bovi, R. J., Smits, A., and Pylypiw, H. M. (2011). Rapid method for the determination of total monosaccharide in Enterobacter cloacae strains using fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Am. J. Anal. Chem. 2, 212–216. doi: 10.4236/ajac.2011.22025

EUCAST (2013). European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Available online at: http://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUC

Fons, M., Hégé, T., Ladiré, M., Raibaud, P., Ducluzeau, R., and Maguin, E. (1997). Isolation and characterization of a plasmid from Lactobacillus fermentum conferring erythromycin resistance. Plasmid. 37, 199–203. doi: 10.1006/plas.1997.1290

Foulquié Moreno, M. R., Sarantinopoulos, P., Tsakalidou, E., and De Vuyst, L. (2006). The role and application of enterococci in food and health. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 106, 1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.06.026

Frost, L. S., Leplae, R., Summers, A. O., and Toussaint, A. (2005). Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat. Rev. Microb. 3, 722–732. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1235

Garbisu, C., Garaiyurrebaso, O., Lanzén, A., Álvarez-Rodríguez, I., Arana, L., Blanco, F., et al. (2018). Mobile genetic elements and antibiotic resistance in mine soil amended with organic wastes. Sci. Total Environ. 621, 725–733. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.221

Gillespie, M. T., Lyon, B. R., Loo, L. S. L, Matthews, P. R., Stewart, P. R., and Skurray, R. A. (1987). Homologous direct repeat sequences associated with mercury, methicillin, tetracycline and trimethoprim resistance determinants in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 43, 165–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1987.tb02117.x

Grass, G., Rensing, C., and Solioz, M. (2011). Metallic copper as an antimicrobial surface. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 1541–1547. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02766-10

Grohmann, E., Muth, G., and Espinosa, M. (2003). Conjugative plasmid transfer in gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67, 277–301. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.2.277-301.2003

Guéguinou, N., Huin-Schohn, C., Bascove, M., Bueb, J. L., Tschirhart, E., Legrand-Frossi, C., et al. (2009). Could spaceflight-associated immune system weakening preclude the expansion of human presence beyond Earth's orbit? J. Leukocyte Biol. 86, 1027–1038. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0309167

Gupta, A., Matsui, K., Lo, J.-F., and Silver, S. (1999). Molecular basis for resistance to silver cations in Salmonella. Nat. Med. 5, 183–188. doi: 10.1038/5545

Guridi, A., Diederich, A. K., Aguila-Arcos, S., Garcia-Moreno, M., Blasi, R., Broszat, M., et al. (2015). New antimicrobial contact catalyst killing antibiotic resistant clinical and water borne pathogens. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 50, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2015.01.080

Hall, C. W., and Mah, T. F. (2017). Molecular mechanisms of biofilm-based antibiotic resistance and tolerance in pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 41, 276–301. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux010

Hollenbeck, B. L., and Rice, L. B. (2012). Intrinsic and acquired resistance mechanisms in Enterococcus. Virulence. 3, 421–433. doi: 10.4161/viru.21282

Holmes, A. H., Moore, L. S. P., Sundsfjord, A., Steinbakk, M., Regmi, S., Karkey, A., et al. (2015). Understanding the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet 387, 176–187. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00473-0

Horneck, G., Klaus, D. M., and Mancinelli, R. L. (2010). Space microbiology. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 121–156. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-09

Kacena, M. A., Merrell, G. A., Manfredi, B., Smith, E. E., Klaus, D. M., and Todd, P. (1999). Bacterial growth in space flight: logistic growth curve parameters for Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 51, 229–234. doi: 10.1007/s002530051386

Kennedy, A. D., Forcella, S. F., Martens, C., Whitney, A. R., Braughton, K. R., Chen, L., et al. (2010). Complete nucleotide sequence analysis of plasmids in strains of Staphylococcus aureus clone USA300 reveals a high level of identity among isolates with closely related core genome sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48, 4504–4511. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01050-10

Khan, S. A., Nawaz, M. S., Khan, A. A., and Cerniglia, C. E. (1999). Simultaneous detection of erythromycin-resistant methylase genes ermA and ermC from Staphylococcus spp. by multiplex-PCR. Mol. Cell Probes. 13, 381–387. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1999.0265

Khan, S. A., and Novick, R. F. (1983). Complete nucleotide sequence of pT181, a tetracycline-resistance plasmid from Staphylococcus aureus. Plasmid 10, 251–259. doi: 10.1016/0147-619X(83)90039-2

Klaus, D., Simske, S., Todd, P., and Stodieck, L. (1997). Investigation of space flight effects on Escherichia coli and a proposed model of underlying physical mechanisms. Microbiology 143, 449–455. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-2-449

Kohler, V., Vaishampayan, A., and Grohmann, E. (2018). Broad-host-range Inc18 plasmids: occurrence, spread and transfer mechanisms. Plasmid 99, 11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2018.06.001

Kwong, S. M., Lim, R., LeBard, R. J., Skurray, R. A., and Firth, N. (2008). Analysis of the pSK1 replicon, a prototype from the staphylococcal multiresistance plasmid family. Microbiology 154, 3084–3094. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/017418-0

Landau, U., Meyer, C., and Grohmann, E. (2017a). AGXX – Beitrag der Oberflächentechnik zur Vermeidung von Biofilmen (Teil 1). Galvanotechnik 108, 885–890.

Landau, U., Meyer, C., and Grohmann, E. (2017b). AGXX – Beitrag der Oberflächentechnik zur Vermeidung von Biofilmen (Teil 2). Galvanotechnik 108, 1110–1121.

Landsdown, A. B. G. (2010). A pharmacological and toxicological profile of silver as an antimicrobial agent in medical devices. Adv. Pharmacol. Sci. 2010:910686. doi: 10.1155/2010/910686

Laverde, D., Probst, I., Romero-Saavedra, F., Kropec, A., Wobser, D., Keller, W., et al. (2017). Targeting type IV secretion system proteins to combat multidrug-resistant Gram-positive pathogens. J. Infect. Dis. 215, 1836–1845. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix227

Li, F., Collins, J. G., and Keene, F. R. (2015). Ruthenium complexes as antimicrobial agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 2529–2542. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00343H

Li, F., Mulyana, Y., Feterl, M., Warner, J. M., Collins, J. G., and Keene, F. R. (2011). The antimicrobial activity of inert oligonuclear polypyridylruthenium(II) complexes against pathogenic bacteria, including MRSA. Dalton Trans. 40, 5032–5038. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10250h

Li, X. Z., Hauer, B., and Rosche, B. (2007). Single-species microbial biofilm screening for industrial applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 76, 1255–1262. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1108-4

Maillard, J., and Hartemann, P. (2012). Silver as an antimicrobial: facts and gap in knowledge. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 39, 373–383. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.713323

Mauclaire, L., and Egli, M. (2010). Effect of simulated microgravity on growth and production of exopolymeric substances of Micrococcus luteus space and earth isolates. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 59, 350–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00683.x

Mayer, T., Blachowicz, A., Probst, A. J., Vaishampayan, P., Checinska, A., Swarmer, T., et al. (2016). Microbial succession in an inflated lunar/Mars analog habitat during a 30-day human occupation. Microbiome 4, 1–17. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0167-0

McKenzie, T., Hoshino, T., Tanaka, T., and Sueoka, N. (1986). The nucleotide sequence of pUB110: some salient features in relation to replication and its regulation. Plasmid 15, 93–103. doi: 10.1016/0147-619X(86)90046-6

Mohammadou, B., Le Blay, G., Mbofung, C. M., and Barbier, G. (2014). Antimicrobial activities, toxinogenic potential and sensitivity to antibiotics of Bacillus strains isolated from Mbuja, a Hibiscus sabdariffa fermented seeds from Cameroon. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 13, 3617–3627. doi: 10.5897/AJB2014.13907

Needham, C., Rahman, M., Dyke, K. G. H., and Noble, W. C. (1994). An investigation of plasmids from Staphylococcus aureus that mediate resistance to mupirocin and tetracycline. Microbiology 40, 2577–2583.

Nickerson, C. A., Mark Ott, C., Wilson, J. W., Ramamurthy, R., and Pierson, D. L. (2004). Microbial responses to microgravity and other low-shear environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 345–361. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.345-361.2004

Novikova, N., De Boever, P., Poddubko, S., Deshevaya, E., Polikarpov, N., Rakova, N., et al. (2006). Survey of environmental biocontamination on board the International Space Station. Res. Microbiol. 157, 5–12. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2005.07.010

Novikova, N. D. (2004). Review of the knowledge of microbial contamination of the Russian manned spacecraft. Microb. Ecol. 47, 127–132. doi: 10.1007/s00248-003-1055-2

Nuebel, U., Dordel, J., Kurt, K., Strommenger, B., Westh, H., Shukla, S. K., et al. (2010). A timescale for evolution, population expansion, and spatial spread of an emerging clone of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000855. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000855

Nyenje, M. E., Green, E., and Ndip, R. N. (2013). Evaluation of the effect of different growth media and temperature on the suitability of biofilm formation by Enterobacter cloacae strains isolated from food samples in South Africa. Molecules 18, 9582–0593. doi: 10.3390/molecules18089582

Oliveira, M., Santos, V., Fernandes, A., Nunes, S. F., and Bernardo, F. (2010). “Pitfalls of antimicrobial susceptibility testing of enterococci isolated from farming broilers by the disk diffusion method,” in Current Research, Technology and Education Topics in Applied Microbiology and Microbial Biotechnology, ed A. Méndez-Vilas (Badajoz: Formatex Research Center), 415–418.

Qi, L., Li, H., Zhang, C., Liang, B., Li, J., Wang, L., et al. (2016). Relationship between antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation, and biofilm-specific resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Front Microbiol. 7:483. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00483

Rafii, F. (2015). Antimicrobial resistance in clinically important biofilms. World J. Pharmacol. 4, 31–46. doi: 10.5497/wjp.v4.i1.31

Roberts, A. P., and Mullany, P. (2011). Tn916-like genetic elements: a diverse group of modular mobile elements conferring antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 856–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00283.x

Roberts, M. C. (2005). Update on acquired tetracycline resistance genes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 245, 195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.02.034

Rohr, U., Senger., M., Selenka, F., Turley, R., and Wilhelm, M. (1999). Four years of experience with silver-copper ionization for control of legionella in a German university hospital hot water plumbing system. Clin. Infect. Dis. 29, 1507–1511. doi: 10.1086/313512

Rosenzweig, J. A., Abogunde, O., Thomas, K., Lawal, A., Nguyen, Y. U., Sodipe, A., et al. (2010). Spaceflight and modeled microgravity effects on microbial growth and virulence. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 85, 885–891 doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2237-8

Russell, A. D., and Hugo, W. B. (1994). Antimicrobial activity and action of silver. Med. Chem. 31, 351–370. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6468(08)70024-9

Schäberle, T. F., and Hack, I. M. (2014). Overcoming the current deadlock in antibiotic resistance. Trends Microbiol. 22, 165–167. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2013.12.007

Schiwon, K. (2011). Charakterisierung von Gram-positiven Isolaten aus der Antarktis Forschungsstation Concordia, der Internationalen Raumstation (ISS) und türkischen Lebensmitteln bezüglich Antibiotikaresistenzen, Gentransfer und Biofilmbildung. dissertation thesis, Technical University Berlin, Berlin.

Schiwon, K., Arends, K., Rogowski, K. M., Fürch, S., Prescha, K., Sakinc, T., et al. (2013). Comparison of antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation and conjugative transfer of Staphylococcus and Enterococcus isolates from International Space Station and Antarctic Research Station Concordia. Microbial. Ecol. 65, 638–651. doi: 10.1007/s00248-013-0193-4

Sidhu, M. S., Heir, E., Leegaard, T., Wiger, K., and Holck, A. (2002). Frequency of disinfectant resistance genes and genetic linkage with β-lactamase transposon Tn552 among clinical staphylococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 2797–2803. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.2797-2803.2002

Smillie, C., Garcillan-Barcia, M. P., Francia, M. V., Rocha, E. P. C., and de la Cruz, F. (2010). Mobility of Plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 434–452. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-10

Soge, O. O., Beck, N. K., White, T. M., No, D. B., and Roberts, M. C. (2008). A novel transposon, Tn6009, composed of a Tn916 element linked with a Staphylococcus aureus mer operon. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62, 674–680. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn255

Sonnenfeld, G. (2005). The immune system in space, including earth-based benefits of space-based research. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 6, 343–349. doi: 10.2174/1389201054553699

Storti, A., Pizzolitto, A. C., and Loschchaign-Pizzolitto, E. (2005). Detection of mixed microbial biofilms on central venous catheters removed from intensive care unit patients. Braz. J. Microbiol. 36, 275–280. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822005000300013

Tamanna, S., Barai, L., Ahmed, A., and Haq, J. A. (2014). High level gentamicin resistance and susceptibility to vancomycin in enterococci in a tertiary care hospital of Dhaka City. Ibrahim Med. Coll. J. 7, 28–31. doi: 10.3329/imcj.v7i2.20103

Taylor, P. W. (2015). Impact of space flight on bacterial virulence and antibiotic susceptibility. Infect. Drug Resist. 8, 249–262. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S67275

Thallinger, B., Prasetyo, E. N., Nyanhongo, G. S., and Guebitz, G. M. (2013). Antimicrobial enzymes: an emerging strategy to fight microbes and microbial biofilms. J. Biotechnol. 8, 97–109. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200313

Vaishampayan, A., de Jong, A., Wight, D. J., Kok, J., and Grohmann, E. (2018). A novel antimicrobial coating represses biofilm and virulence-related genes in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 9:221. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00221

Van Houdt, R., Mijnendonckx, K., and Leys, N. (2012). Microbial contamination monitoring and control during human space mission. Planet. Space Sci. 60, 115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.pss.2011.09.001

Venkateswaran, K., Vaishampayan, P., Cisneros, J., Pierson, D. L., Rogers, S. O., and Perry, J. (2014). International Space Station environmental microbiome - microbial inventories of ISS filter debris. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 6453–6466. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5650-6

Vonberg, R. P., Sohr, D., Bruderek, J., and Gastmeier, P. (2008). Impact of a silver layer on the membrane of tap water filters on the microbiological quality of filtered water. BMC Infect. Dis. 8:133. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-133

Vukanti, R., Model, M. A., and Leff, L. G. (2012). Effect of modeled reduced gravity conditions on bacterial morphology and physiology. BMC Microbiol. 12:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-4

Warnes, S. L., and Keevil, C. W. (2013). Inactivation of Norovirus on dry copper alloy surfaces. PLoS ONE. 8:9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075017

Wendelbo, Ø., Jureen, R., Eide, G. E., Digranes, A., Langeland, N., and Harthug, S. (2003). Outbreak of infection with high-level gentamicin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis (HLGRE) in a Norwegian hospital. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 9, 662–669. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00668.x

Wilson, J. W., Ott, C. M., Höner zu Bentrup, K., Ramamurthy, R., Quick, R. L., Porwollik, S., et al. (2007). Space flight alters bacterial gene expression and virulence and reveals a role for global regulator Hfq. Nat. Acad. Sci. 104, 16299–16304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707155104

Yamaguchi, N., Roberts, M., Castro, S., Oubre, C., Makimura, K., and Leys, N. (2014). Microbial monitoring of crewed habitats in space - current status and future perspectives. Microb. Environ. 29, 250–260. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME14031

Keywords: antimicrobial surface, gram-positive human-pathogenic bacteria, antibiotic resistance, biofilm, conjugative transfer, International Space Station, hostile environment

Citation: Sobisch L-Y, Rogowski KM, Fuchs J, Schmieder W, Vaishampayan A, Oles P, Novikova N and Grohmann E (2019) Biofilm Forming Antibiotic Resistant Gram-Positive Pathogens Isolated From Surfaces on the International Space Station. Front. Microbiol. 10:543. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00543

Received: 30 November 2018; Accepted: 01 March 2019;

Published: 19 March 2019.

Edited by:

José Luis Capelo, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, PortugalReviewed by:

Atte Von Wright, University of Eastern Finland, FinlandJose Ruben Morones-Ramirez, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Mexico

Copyright © 2019 Sobisch, Rogowski, Fuchs, Schmieder, Vaishampayan, Oles, Novikova and Grohmann. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elisabeth Grohmann, ZWxpc2FiZXRoLmdyb2htYW5uQGJldXRoLWhvY2hzY2h1bGUuZGU=

Lydia-Yasmin Sobisch

Lydia-Yasmin Sobisch Katja Marie Rogowski

Katja Marie Rogowski Jonathan Fuchs

Jonathan Fuchs Wilhelm Schmieder2

Wilhelm Schmieder2 Ankita Vaishampayan

Ankita Vaishampayan Elisabeth Grohmann

Elisabeth Grohmann