95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 28 May 2018

Sec. Evolutionary and Genomic Microbiology

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00895

This article is part of the Research Topic Horizontal Gene Transfer and Genetic Diversity in Bacteria View all 20 articles

In Agrobacterium-mediated transformation (AMT) of plants, a single-strand (ss) T-DNA covalently linked with a VirD2 protein moves through a bacterial type IV secretion channel called VirB/D4. This transport system originates from conjugal plasmid transfer systems of bacteria. The relaxase VirD2 and its equivalent protein Mob play essential roles in T-DNA transfer and mobilizable plasmid transfer, respectively. In this study, we attempted to transfer a model T-DNA plasmid, which contained no left border but had a right border sequence as an origin of transfer, and a mobilizable plasmid through the VirB/D4 apparatus to Escherichia coli, Agrobacterium and yeast to compare VirD2-driven transfer with Mob-driven one. AMT was successfully achieved by both types of transfer to the three recipient organisms. VirD2-driven AMT of the two bacteria was less efficient than Mob-driven AMT. In contrast, AMT of yeast guided by VirD2 was more efficient than that by Mob. Plasmid DNAs recovered from the VirD2-driven AMT colonies showed the original plasmid structure. These data indicate that VirD2 retains most of its important functions in recipient bacterial cells, but has largely adapted to eukaryotes rather than bacteria. The high AMT efficiency of yeast suggests that VirD2 can also efficiently bring ssDNA to recipient bacterial cells but is inferior to Mob in some process leading to the formation of double-stranded circular DNA in bacteria. This study also revealed that the recipient recA gene was significantly involved in VirD2-dependent AMT, but only partially involved in Mob-dependent AMT. The apparent difference in the recA gene requirement between the two types of AMT suggests that VirD2 is worse at re-circularization to complete complementary DNA synthesis than Mob in bacteria.

The T-DNA transfer system is derived from bacterial conjugal plasmid DNA transfer systems (Lawley et al., 2004), which exchange genetic material between bacterial species. There are convincing similarities between the T-DNA and bacterial conjugal transfer systems (Lessl and Lanka, 1994). Agrobacterium VirD2 relaxase, in collaboration with VirD1, makes a nick at the right border (RB) and left border (LB) sequences and covalently attaches to the 5′ end of the resulting single-stranded (ss) T-DNA (Ward and Barnes, 1988; De Vos and Zambryski, 1989; Vogel and Das, 1992; Scheiffele et al., 1995). Essentially the same reaction takes place in bacterial conjugation. TraI encoded in the F plasmid binds to and makes a nick at the origin of transfer (oriT) with assistance by the TraY protein (Ippen-Ihler and Skurray, 1993). MobA encoded in the mobilizable plasmid RSF1010 recognizes oriT as its DNA substrate (Scholz et al., 1989). The TraI and MobA relaxases produce a nick at oriT and covalently attach to the 5′ end of the resulting ssDNA of the respective plasmids (Pansegrau and Lanka, 1991; Scherzinger et al., 1993; Bohne et al., 1998; Fullner, 1998). The complexes between the relaxase and ssDNA from each plasmid DNA are transported through a T4SS into recipient cells (Frey and Bagdasarian, 1989; Zambryski, 1992; Firth et al., 1996; Alvarez-Martinez and Christie, 2009; Wong et al., 2012).

The large operon virB in Ti plasmids (Suzuki et al., 2009) harbors 11 genes for the formation of a T4SS, called the VirB/D4 channel (Alvarez-Martinez and Christie, 2009). A similar set of genes is dedicated to the construction of a T4SS for the transfer of F and RP4/RK2 plasmids (Lawley et al., 2003; Christie et al., 2014). Transfer via the T4SS requires another factor called a coupling protein, e.g., VirD4 for the T-DNA of Ti plasmids and TraD for F. Specifically, the coupling proteins recognize nucleo-protein substrates and then pass appropriate substrates to the T4SS membrane-spanning channel, and therefore are also called the gatekeepers of the channel (Lawley et al., 2003; Christie et al., 2014).

Conjugal plasmid transfer among Gram-negative bacteria is generally recognized as the integration of four steps, namely the formation and inter-cellular transfer of ssDNA, re-circularization of the transferred DNA and completion of the complementary lagging strand DNA synthesis in recipient bacterial cells (Bhattacharjee and Meyer, 1991). The ssDNAs emerging in the recipient bacterial cytoplasm would bind to SSBs and probably to RecA before the completion of the re-circularization and complementary DNA synthesis. Conjugal transfer is quite similar to T-DNA transfer but has several differences, not only of the relaxases, but also their processes in recipient cells. During T-DNA transfer, VirD2 at the 5′-end of the ssT-DNA should remain intact in the eukaryotic recipient cytoplasm (Gelvin, 2012), while rapid re-circularization in recipient bacterial cells would be required for a high yield of plasmid transconjugants. The ssDNA binding protein VirE2 is essential for plant tumorigenesis by agrobacteria and AMT (Zupan et al., 1996), whereas the significance of plasmid-encoded SSBs remains obscure in conjugal plasmid transfer (Lanka and Pansegrau, 1999).

T-DNA transfer by Agrobacterium tumefaciens can genetically transform a broad range of eukaryotic organisms including fungi and mammalian cells under laboratory conditions (Lacroix et al., 2006). This wide transfer range suggests that the factors provided by recipient cells are so conserved that they can associate well with those from Agrobacterium. Such exotic combinations of donor and recipient organisms or T4SS and substrate DNAs could give insights into the mechanisms involved. Mobilizable plasmids are delivered through conjugation, though they possess no gene for any membrane-spanning channel (Smillie et al., 2010). Such plasmids employ a carrier T4SS supplied by a conjugative plasmid, e.g., RP4/RK2. Several mobilizable plasmids can also be transferred by the Agrobacterium VirB/D4 T4SS, e.g., RSF1010 and pTF-FC2 to plant cells (Bravo-Angel et al., 1999; Dube et al., 2004) and RSF1010 to other Agrobacterium cells (Beijersbergen et al., 1992).

At present, little is known about T-DNA transfer to bacteria. Only one paper, by Kelly and Kado (2002), has reported T-DNA transfer to a Gram-positive bacterium, Streptomyces lividans. Extensive investigation of T-DNA transfer to bacteria might reveal the differences between the processes of T-DNA transfer and conjugative transfer and how T-DNA transfer evolved to adapt to eukaryotic recipients.

In this study, we constructed a model T-DNA plasmid that contained an RB, and attempted VirD2-mediated transfer of this plasmid to bacteria and compared the results with transfer to yeast and with Mob-mediated transfer of a mobilizable plasmid. In the VirD2-driven transport experiments, the recipient E. coli exhibited much lower efficiency than yeast. Inversely, in Mob-driven transport, the recipient E. coli showed higher efficiency than yeast. These results indicate that the T-DNA transfer system retains the features of conjugal transfer, but has a functional inclination toward eukaryotes.

The bacterial and yeast strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli strain BW25113 and a set of knockout mutant derivatives of BW25113 (Baba et al., 2006) were supplied by the National BioResource Project (National Institute of Genetics, Japan). The recAΔ mutant in the set was endowed with streptomycin resistance by spontaneous mutation and a kanamycin resistance gene cassette was removed by site-specific recombination using FLP recombinase according to Baba et al. (2006). Yeast cells were cultured in liquid YPD medium at 28°C, while E. coli and Agrobacterium strains were grown in liquid LB medium at 37°C and 28°C, respectively. Co-cultivation for yeast AMT was performed as described in our previous papers (Kiyokawa et al., 2009, 2012; Ohmine et al., 2016), and is briefly explained below. Co-cultivation for AMT of bacteria was carried out essentially following that for the yeast AMT, with some modifications as mentioned in the corresponding subsection.

The plasmids and primers used in this study are listed in Tables 1, 2, respectively. The binary plasmid pSRK-R316 was constructed as follows. pSRKKm (Khan et al., 2008) was digested with Csp45I and the resulting 4.1-kbp DNA fragment lacking the lacIq and lacZ genes was self-ligated to produce pSRK-Csp. A 3.0-kbp DNA fragment, lacking the mob gene, was amplified using the primers pSRKKm-rep-fw2 and pSRKKm-Km-rv with pSRK-Csp as a template. The resulting 3.0-kbp PCR product was digested with SpeI and then self-ligated to form the plasmid pSRK-KR. A 2.9-kbp fragment was amplified by PCR using the primers pSRK-C-fwS and pSRK-KR-rv from the plasmid pSRK-KR. In addition, a 0.2-kbp fragment, containing the RB and overdrive sequences, was amplified using the primers pBIN19-RB-fw and pBIN19-RB-rv from the binary vector pBIN19 (Bevan, 1984). The resulting 2.9-kbp and 0.2-kbp PCR products were digested with BamHI and SacII, and then ligated to each other to construct the 3.1-kbp plasmid pSRK-RB. A 3.7-kbp DNA was amplified by PCR using pRS316-fwB and pRS316-rvB from the yeast–E. coli shuttle vector pRS316 (Sikorski and Hieter, 1989). The PCR product and the plasmid pSRK-RB were digested with BamHI and then ligated together to produce pSRK-R316.

The plasmid pSRK-R316ΔRB was prepared as follows. A 5.5-kbp DNA fragment, lacking the RB sequence, was amplified using the primers pSRK-C-fwEH and pRS316-fwKH from pSRK-R316. The resulting 5.5-kbp PCR product was digested with HindIII and then self-ligated, resulting in the RB-free plasmid pSRK-R316ΔRB.

Plasmids for targeted gene deletion were created by seamless fusion (Motohashi, 2015; Okegawa and Motohashi, 2015) between the EcoRI/PstI-digested pK18mobsacB and two DNAs located upstream and downstream of the ORF, which were amplified by PCR using the primer sets virD2Bo542-del-Fw1 and virD2Bo542-del-Rv1, and virD2Bo542-del-Fw2 and virD2Bo542-del-Rv2 to form an 8.8-kbp plasmid, pK18msΔBovirD2; and virE2Bo542-del-Fw1 and virE2Bo542-del-Rv1, and virE2Bo542-del-Fw2 and virE2Bo542-del-Rv2 to form an 8.8-kbp plasmid, pK18msΔBovirE2.

Targeted gene replacement in vivo by HR was carried out as described previously (Kiyokawa et al., 2012).

Amplification by PCR was carried out using KOD Plus NEO DNA polymerase (TOYOBO, Osaka) for plasmid DNA construction and DNA preparation for transformation.

AMT of the yeast strain was performed as described in our previous papers (Kiyokawa et al., 2009, 2012; Ohmine et al., 2016). In short, Agrobacterium donor cells were pre-treated with liquid AB induction medium containing 100 μM AS at 28°C for 24 h, and then co-cultivated with recipient yeast cells on solid AB mating medium containing 100 μM AS for 24 h at 22°C. Yeast AMT transformants were selected using a solid SD selective medium (without uracil) containing 200 μg/ml cefotaxime.

AMT of Gram-negative bacteria was performed as follows. Aliquots of 50 μl of donor cell suspension (1.2 × 1010 cells/ml) and recipient cell suspension (2.4 × 109 cells/ml) were mixed and then spotted on solid AB induction medium containing AS. After co-cultivation for 24 h at 22°C, the cell mixture was resuspended in AB medium (pH 7.0) and then spread on solid LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 400 μg/ml streptomycin to select for AMT transformant colonies. The AMT efficiency was calculated by dividing the AMT transformant colony number by the output recipient cell number.

Circular and linear DNAs, namely intact pSRK-R316 and its PCR product amplified using the primers pBIN19-RB-fw and pRS316-fwKH (the PCR product was a linear double-stranded DNA containing approximately the whole plasmid sequence), were transformed into E. coli strains by electroporation as described previously (Sawahel et al., 1993; Yamamoto et al., 2007).

The transferred pSRK-R316 plasmids were extracted from each transformant colony. The region around the RB sequence was amplified by PCR using the primers T-circle-fw and T-circle-rv. The PCR products were applied to sequencing reactions and analyzed with a Genetic Analyzer 3130XL (Applied Biosystems).

All experiments in this study were independently repeated at least three times. Each datum shown in figures and tables represents a mean with a standard deviation. Statistical analyses were carried out using the R program version 3.3.3 and its expansion packages1. Individual methods for statistical comparisons are described in each table and figure. Data of no AMT colony were excluded from the statistical analyses.

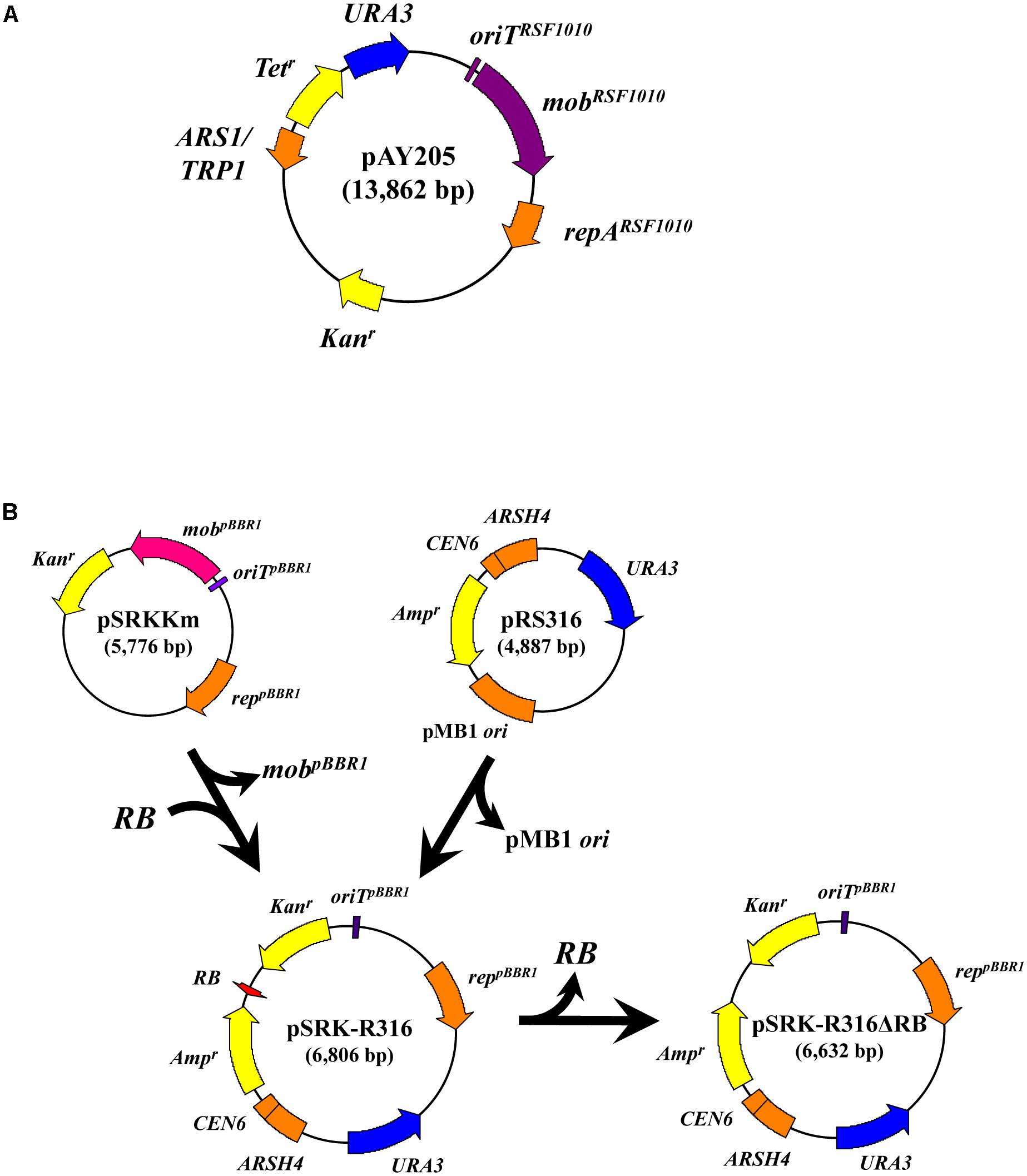

We performed AMT using Agrobacterium strain C58m and two E. coli strains, LE392sm and BW25113sm, as recipients. In this experiment, the donor Agrobacterium strain EHA105 was loaded with two types of plasmids. As shown in Figure 1A, the IncQ plasmid pAY205, which is a derivative of the broad-host-range plasmid RSF1010, encodes the mob gene and oriT of RSF1010 (mobRSF1010 gene and oriT RSF1010) (Nishikawa et al., 1992). The broad-host-range plasmid pSRKKm (Figure 1B) is a pBBR1-based plasmid and encodes the mob gene and oriT of pBBR1 (mobpBBR1 gene and oriT pBBR1) (Khan et al., 2008). The new plasmid pSRK-R316 (Figure 1B) is a pSRKKm-derivative plasmid. pSRK-R316 lacks the mob gene but contains an RB and overdrive sequence set derived from the binary plasmid pBIN19 (Bevan, 1984). The RB and overdrive sequence set is abbreviated to RB in this paper. Therefore, pSRK-R316 was expected to be recognized by VirD2 and transported through the VirB/D2 channel.

FIGURE 1. Construction of the binary plasmid pSRK-R316 and its RB-less derivative. (A) Schematic map of pAY205. (B) Most of pSRKKm excluding the mobpBBR1 gene was PCR amplified and ligated with an RB fragment derived from pBIN19 as described in the Section “Materials and Methods.” The resulting plasmid was ligated with the yeast autonomous-type vector pRS316 to produce pSRK-R316. pSRK-R316ΔRB is pSRK-R316 but lacks the RB.

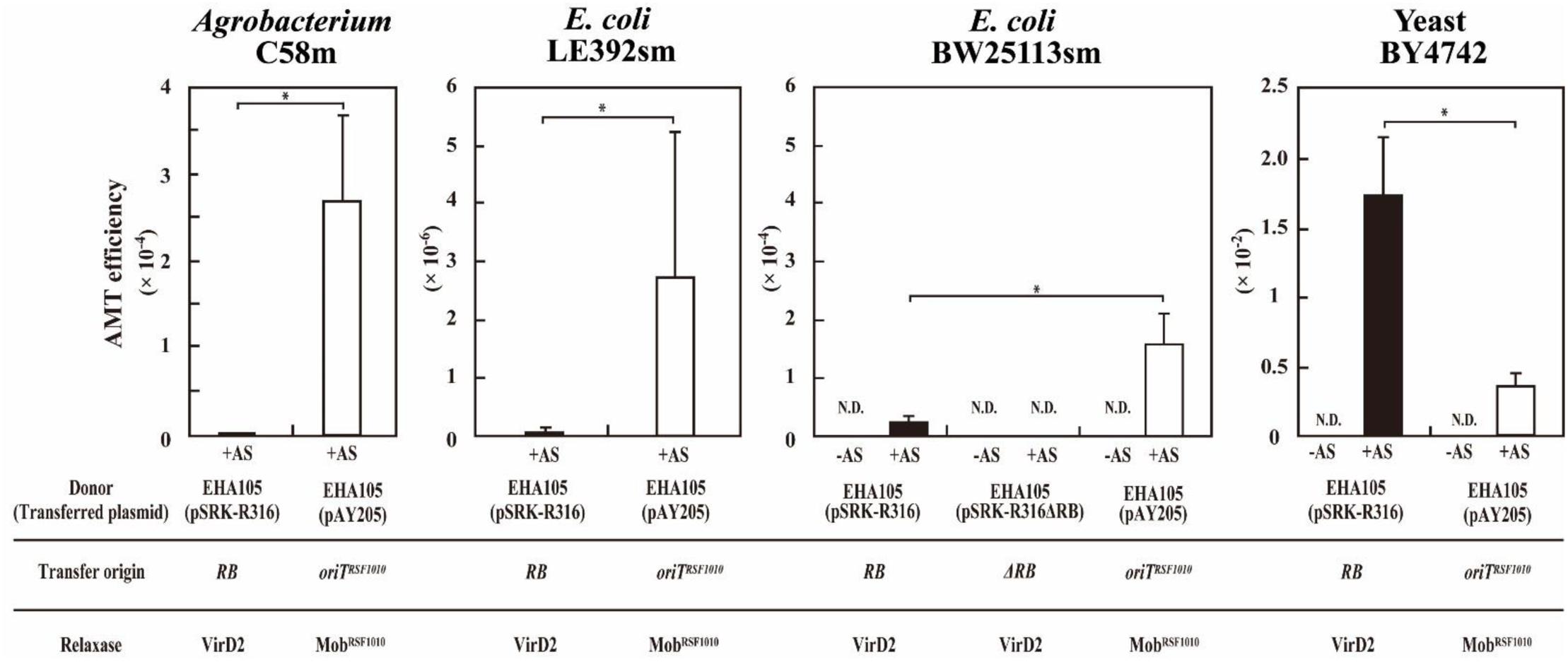

In the test of DNA transfer to bacteria, mobilization of pAY205 to Agrobacterium strain C58m occurred at high efficiency (2.7 × 10-4) (Table 3A). However, when incubated with the donor Agrobacterium containing pSRK-R316, C58m produced only a few offspring colonies at an efficiency of 2.3 × 10-7 (Figure 2 and Table 3A). Similar results with lower efficiencies were obtained when E. coli strain LE392sm was employed as a recipient (Figure 2 and Table 3A), whereas the experiment using E. coli strain BW25113sm as a recipient produced many more transformant colonies than that using LE392sm. The AMT efficiency of BW25113sm for pSRK-R316 reached an order of 10-5 (2.4 × 10-5) (Figure 2 and Table 3A).

FIGURE 2. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of a yeast and two bacteria. Recipient cells were co-cultivated with Agrobacterium strain EHA105 (pSRK-R316) (filled bar) and with EHA105 (pAY205) (open bar). The AMT efficiency was defined as the number of AMT transformants divided by the number of output recipient cells. Recipient strains included A. tumefaciens strain C58m, E. coli strains LE392sm and BW25113sm, and yeast strain BY4742. Single asterisks indicate significant difference (P < 0.05) by Student’s t-test.

Next, we tested the AMT ability of the plasmids pSRK-R316 and pAY205 using yeast as a eukaryotic recipient. As shown in Figure 2, high AMT efficiencies were achieved not only with pAY205 but also pSRK-R316. pSRK-R316 exhibited a fivefold higher efficiency (1.7 × 10-2) than pAY205 did (3.6 × 10-3) (Figure 2 and Table 3A).

The AMT efficiency of the Mob-driven transfer (pAY205) was 6-fold and 46-fold higher than that of the VirD2-driven transfer (pSRK-R316) when the recipient cells were E. coli BW25113sm and LE392sm, respectively (Table 3A). These AMT data of the bacterial recipients were contrary to the AMT data of the yeast strain (Figure 2 and Table 3A). The AMT efficiency of Mob-driven transfer (pAY205) was fivefold less than that of VirD2-driven transfer (pSRK-R316) when the recipient cells were yeast. When the VirD2-mediated AMT efficiency was normalized by dividing by the Mob-mediated AMT efficiency in each recipient species, VirD2-mediated AMT of yeast was superior by 33-fold to that of E. coli BW25113sm. AMT of Agrobacterium strain C58sm was inferior by more than 100-fold to that of BW25113sm.

In this study, AMT efficiency was calculated by dividing the AMT transformant colony number by the output recipient cell number. To confirm the reliability of the formulas used to evaluate the VirD2 and Mob relaxases, we repeated the above experiments but measured input cell numbers and output donor cell numbers in addition to the output recipient cell number. As shown in Table 4, calculations using other denominator factors including the square root of (donor number × recipient number) (Simonsen et al., 1990) consistently demonstrated the preference of VirD2-driven transport for yeast, similar to calculations using the standard formulas.

Consequently, we conclude that VirD2 is superior to Mob in AMT of yeast, and vice versa Mob is better than VirD2 in AMT of bacteria.

The AMT of E. coli strains depended on Vir proteins because no transformant colonies appeared when the inducer chemical AS for expression of vir genes was omitted from the co-cultivation medium (Table 3A). Although pSRK-R316 lacked a mob pBBR1 gene, it still contained an oriT pBBR1 in addition to an RB. The region around the oriT site was required for the stable replication of pSRK-R316 in the Agrobacterium cells (data not shown); thus, the site could not be eliminated. To confirm whether pSRK-R316 was genuinely transferred in an RB-dependent manner, we constructed pSRK-R316ΔRB, which was pSRK-R316 lacking the RB but retaining oriTpBBR1. When pSRK-R316ΔRB was used in the transfer experiment to the E. coli BW25113sm strain, no transformant colony appeared (Table 3A). Furthermore, a virD2Δ mutant and a virE2Δ mutant were used in the AMT test to determine whether the T-complex component proteins VirD2 and VirE2 are important for AMT to bacteria as well as AMT to yeast. As expected, the virD2Δ mutation in the donor Agrobacterium cells resulted in inability to transform E. coli using pSRK-R316, while the same mutation had a negligible effect (20% reduction) on AMT with pAY205 (Table 3B). These results demonstrated that AMT of E. coli by pSRK-R316 requires RB on the plasmid and VirD2 protein. In addition, the AMT of E. coli with pSRK-R316 and pAY205 occurred in a completely AS-dependent manner (Table 3A). These data demonstrated that the two plasmids were mobilized through the VirB/D4 T4SS not only in the transfer to yeast but also to E. coli, and that the transfer of pSRK-R316 was driven not by MobpBBR1, but by VirD2, while that of pAY205 was executed by MobRSF1010.

As shown above, MobRSF1010-driven transfer was apparently less efficient than VirD2-driven transfer to the yeast recipient (Figure 2 and Table 3). Conversely, the AMT efficiency of MobRSF1010-driven transfer was obviously higher than that of VirD2-driven transfer to bacterial recipients (Table 3A). One feasible explanation for the lower efficiency of VirD2-driven AMT than Mob-driven AMT of yeast is suppression of VirE2 protein export to recipients by RSF1010-derived plasmids in the donor Agrobacterium cells (Binns et al., 1995; Stahl et al., 1998; Bravo-Angel et al., 1999). Supply of VirE2 is required for efficient AMT of yeast (Bundock et al., 1995; Kiyokawa et al., 2012), and a prerequisite for AMT of plants (Binns et al., 1995). Therefore, the RSF1010-derived plasmid pAY205 might decrease its own MobA-driven AMT efficiency of yeast due to decreased VirE2 transport.

To check the validity of the above presumption, we examined the effect of a null mutation in the virE2 gene. As shown in Table 3B, however, virE2Δ mutation in the donor Agrobacterium strain barely affected AMT of E. coli BW25113 in either of the two types of transfer. Conversely, the same mutation decreased the AMT efficiency of yeast to one-third in both types of transfer.

Even in the absence of VirE2, therefore, replacement of the yeast recipient with a bacterial one increased the AMT efficiency of Mob-driven transfer and decreased the efficiency of VirD2-driven transfer (Table 3B). In conclusion, the decreased VirE2 supply due to the presence of the RSF1010-derived plasmid in the donor cells has little effect, if any, on AMT of bacteria and a limited effect on AMT of yeast.

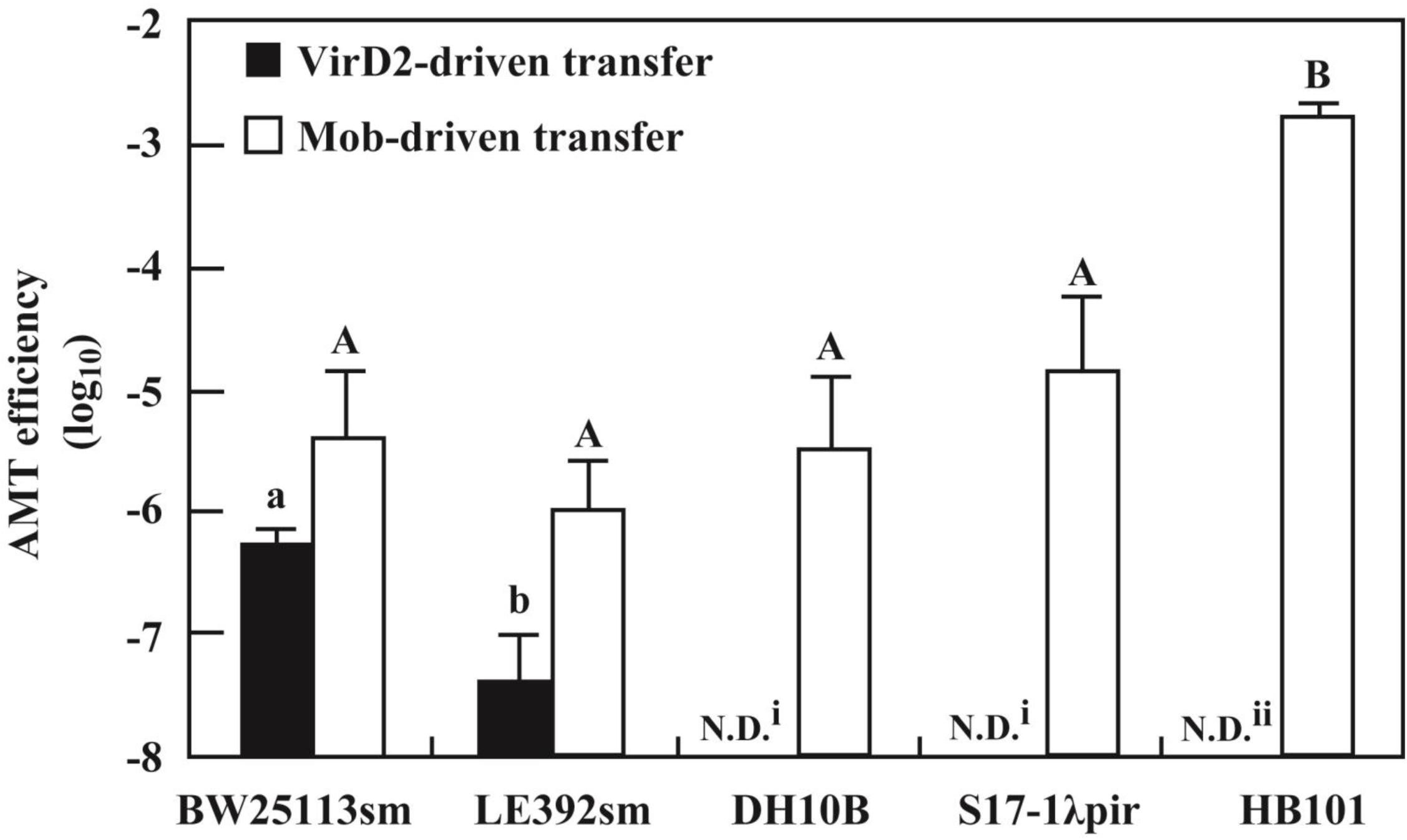

As shown above, E. coli strains BW25113sm and LE392sm were competent to receive pSRK-R316 from the Agrobacterium donor. However, the AMT efficiencies of the two strains differed by more than 10-fold. Therefore, we applied the VirD2-driven transfer system to other E. coli strains. As shown in Figure 3, the DH10B strain was incompetent for AMT of pSRK-R316. As DH10B is a recA-deficient mutant, and BW25113 and LE392 are recA+, the trial was extended to two more recA- mutant strains, S17-1bbbpir and HB101. Similar to DH10B, both strains were apparently unsuitable as recipients for VirD2-driven AMT (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Variation of AMT efficiency among E. coli laboratory strains. AMT was applied to five E. coli laboratory strains as shown in Figure 2. The donor strains used were EHA105 (pSRK-R316) (filled bar) and EHA105 (pAY205) (open bar). N.D. means no transformed offspring were detected (i < 1 × 10-8, ii < 4 × 10-6). Different letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05) by the Tukey–Kramer test.

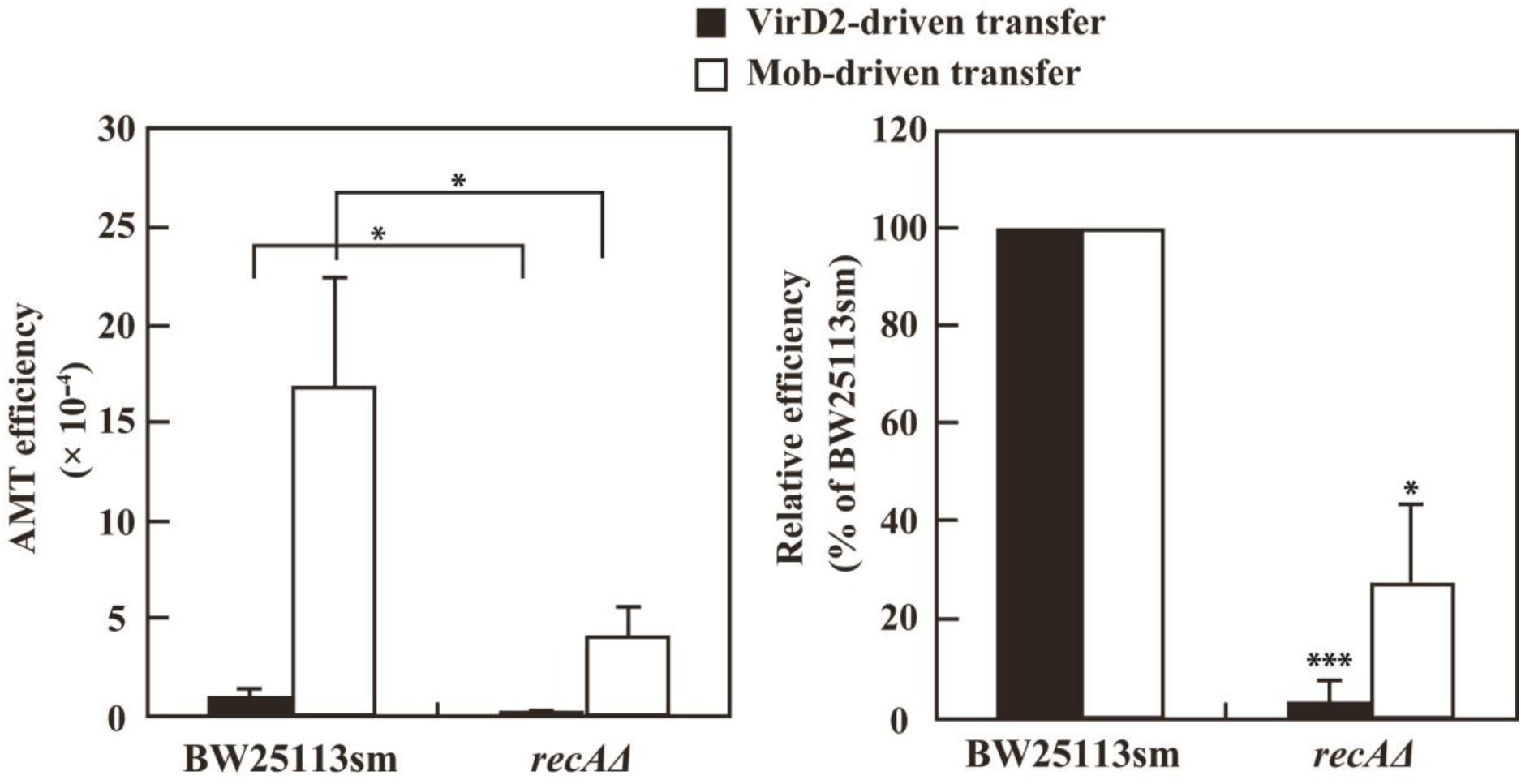

The defectiveness of the recA- strains suggested the involvement of the recA gene in recipient cells for VirD2-driven AMT in E. coli. This idea was confirmed by experiments using a recAΔ derivative of the BW25113 strain. As indicated in Figure 4, VirD2-driven AMT was 32-fold less efficient in the recAΔ strain than in BW25113sm.

FIGURE 4. AMT efficiency of a recAΔ mutant derivative of the E. coli BW25113 strain. BW25113sm (recA+) and its recAΔ mutant strain were subjected to AMT. (Left) AMT efficiency. Single asterisks indicate significant difference (P < 0.05) by either Welch’s t-test (for pSRK-R316 as the transferred substrate) or Student’s t-test (for pAY205 as the transferred substrate). (Right) Relative efficiency calculated using the AMT efficiency of BW25113sm as a benchmark. Single and triple asterisks indicate that the averages of the relative efficiencies were not 100% (P < 0.05, P < 0.001, respectively) by one-sample t-test.

In contrast to the large variation among the laboratory E. coli strains due to the recA-dependence of VirD2-driven transfer, all five E. coli strains were apparently competent for Mob-driven AMT (Figure 3). All strains except HB101 exhibited efficiencies ranging from 10-6 to 10-5. HB101 showed a much higher efficiency that reached 10-3 (Figure 3).

As shown in Figure 4, the recAΔ mutant of the BW25113 strain showed a threefold lower Mob-driven AMT efficiency than the wild type strain. The ratio was much lower than that (32-fold) of VirD2-driven AMT, but still apparent. This finding suggests some role for the RecA protein even in Mob-driven AMT.

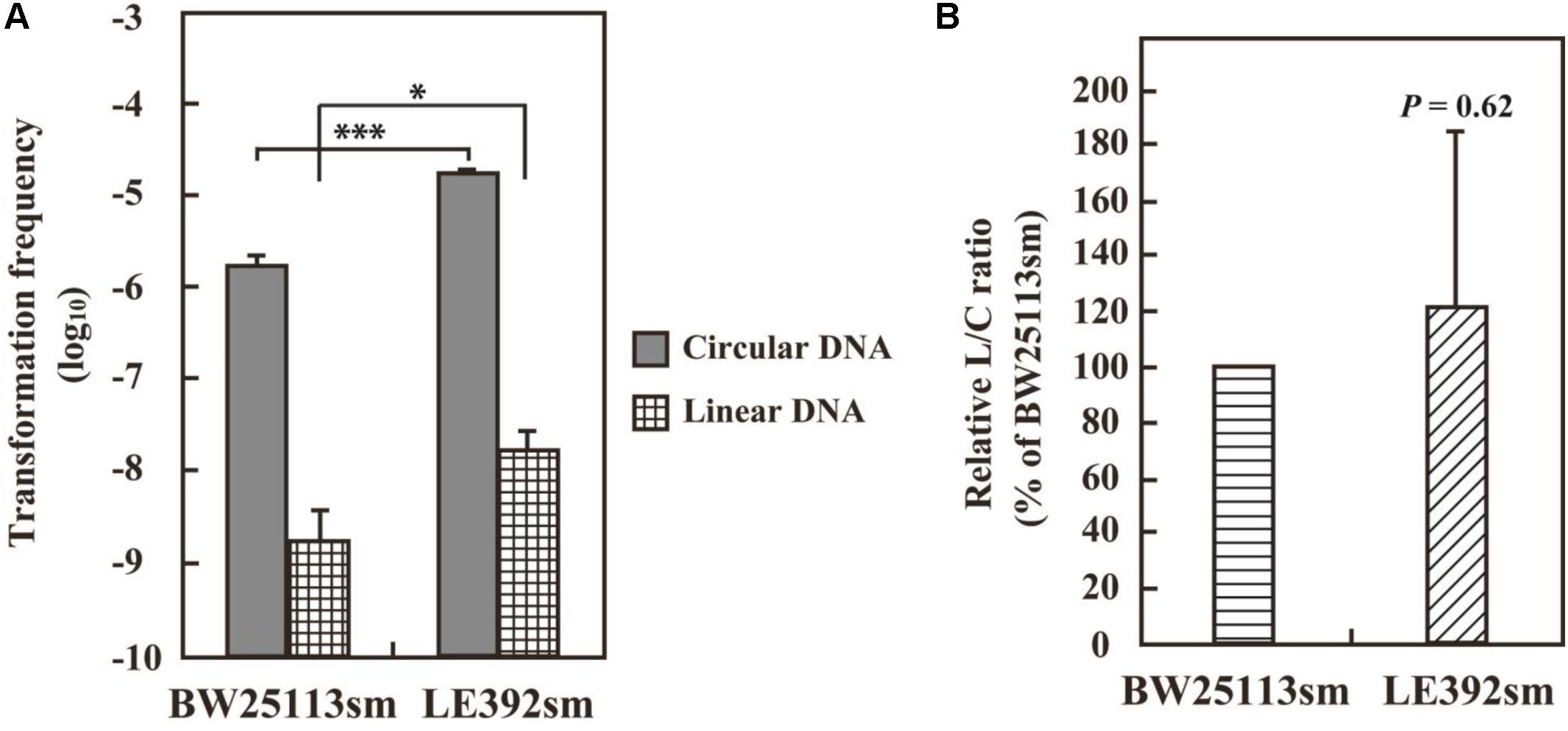

VirD2-driven AMT was successfully carried out using E. coli strain BW25113sm. Apparent, but less efficient, AMT was observed when BW25113sm was replaced with LE392sm. According to their genotypes (Table 1), there was no difference in genes that might affect DNA and cellular processes such as DNA repair and modification. Their plasmid DNA transformation ability was measured to see whether the two strains had any difference in their ability to block foreign DNAs. Electroporation was carried out using intact pSRK-R316 and its PCR product as circular and linear DNA substrates, respectively. The latter was a blunt-ended dsDNA containing almost the entire plasmid sequence. As shown in Figure 5, the transformation frequency of LE392sm was approximately 10-fold higher than that of BW25113sm for both DNA substrates. When the transformation frequency of the linear DNA substrate (L) was normalized to that of the circular DNA substrate (C), the resulting linear versus circular (L/C) ratio was comparable between the two strains (Figure 5), demonstrating that there was no difference in the ability to circularize double-stranded DNA between the strains. These data suggest that the high AMT ability of the BW25113sm strain was specific for VirD2-driven transfer.

FIGURE 5. DNA transformation frequencies of E. coli strains BW25113sm and LE392sm. E. coli cells were electroporated with 50 ng circular pSRK-R316 and linear pSRK-R316 DNA fragments amplified by PCR. Transformation frequency (A) is defined as the number of transformants per μg DNA divided by the viable cell number. Single and triple asterisks indicate significant difference (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively) by Welch’s t-test. (B) The L/C transformation ratio was expressed as the ratio of the transformation frequency obtained with the linearized plasmid (L) divided by that using the circular plasmid (C). Statistical analysis was carried out using one-sample t-test against 100%.

The structure of pSRK-R316 after its AMT transfer to recipient E. coli cells was examined as demonstrated in Figure 6. VirD2-driven transfer was performed on BW25113sm, and then the plasmid DNAs were extracted from eight colonies. Restriction enzyme digestion of the plasmid DNAs suggested that the transferred plasmid DNAs retained their native structures (Figures 6A,B). Further analysis of the extracted plasmids confirmed that the nucleotide sequence at/around the RB was identical to that of pSRK-R316 (Figure 6C).

FIGURE 6. Structure of T-DNA circles extracted from E. coli transformant colonies. E. coli AMT offspring were obtained by co-cultivation with the donor strain EHA105 (pSRK-R316) and the recipient BW25113sm. (A) Physical map of pSRK-R316 showing the locations of two NcoI sites. (B) Extracted plasmid DNAs were digested by NcoI and separated by gel electrophoresis. Lane C: pSRK-R316, lanes 1 – 8: AMT colonies. (C) Alignment of RB junction sequences of plasmids extracted from the eight transformant colonies. The nucleotide sequence at the RB is shaded in light green.

T-DNA was transmitted to a Gram-positive bacterium, Streptomyces lividans, from Agrobacterium via the VirB/D4 system (Kelly and Kado, 2002), and derivatives of the RSF1010 plasmid were mobilized to Agrobacterium (Beijersbergen et al., 1992). This paper has shown that two Gram-negative bacteria, E. coli and A. tumefaciens, are capable of receiving the model T-DNA plasmid pSRK-R316 from Agrobacterium. These data suggest that the VirB/D4 transfer apparatus has the fundamental potential to cover the domain Bacteria as the recipient range in AMT.

The model T-DNA plasmid pSRK-R316 contains an RB but no LB, just like conjugative and mobilizable plasmids including pAY205 possess an oriT. The transfer of pSRK-R316 depended strictly on VirD2 (Figures 2–4 and Table 3B), and the plasmid DNA showed the same structure after transfer as the original plasmid DNA (Figure 6). These results suggest that the VirD2-driven transfer system retains the functionality of the ancestral conjugal transfer system.

The strain BW25113sm was the best recipient for VirD2-driven transfer of the model T-DNA plasmid among the E. coli strains we examined in this study. Various tools are available in the strain BW25113. Notably, systematic resources including mutants have been constructed using BW25113 and its near identical strain W3110 (Baba et al., 2006; Rajagopala et al., 2010), and their phenotypes in several conditions have been described. Such resources would assist the study of the molecular processes of DNA transfer in recipient cells.

This study indicated that the fitness of Mob-driven AMT (transfer of pAY205) to recipient organisms is inverse to that of VirD2-driven AMT (transfer of pSRK-R316) (Figure 2 and Table 3). High and very low frequencies of VirD2-driven AMT were observed in the transfer to yeast and bacterial strains, respectively. This result is reasonable if we consider that plants are the native target recipients for VirD2 and yeast belongs to the domain Eukaryota as do plants. Based on the high frequency of Mob-driven AMT of bacteria and the high frequency of VirD2-driven AMT of yeast via the same T4SS, we speculate that pSRK-R316 is transferred more abundantly to bacterial cells than was estimated based on the VirD2-driven AMT frequencies for bacterial recipient strains (Table 3A). The difference of AMT output productivity depending on host types is primarily attributable to the properties of the two relaxase proteins, and second to differences in the processes and interactions of the relaxases with recipient factors.

All data in this study show the superiority of Mob over VirD2 for plasmid transfer in bacteria. Though VirD2 has evolved from the relaxase for conjugation, we presume that VirD2 has adapted to function in plants so much that it has become weak at interacting with bacterial proteins.

It is noteworthy that in this study recAΔ mutation caused a 32-fold decrease in VirD2-driven AMT in E. coli, while the same mutation caused a threefold decrease in Mob-driven AMT. Though the latter value is tiny compared with the large decrease in VirD2-driven AMT, the value one-third of the wild type level might reflect a short transient exposure of the ssDNA to the recipient cytoplasm during Mob-driven transfer, and some role played by RecA.

RecA plays multiple roles in bacteria (Bell and Kowalczykowski, 2016). Primarily, RecA binds to single-stranded portions of damaged DNA and directs its repair, and upon binding to ssDNAs triggers the expression of a set of genes for DNA repair and recombination. RecA also plays a role in accepting exogenous ssDNA in competent Bacillus subtilis. The protein binds to a competency protein, GomGA, that is localized at the cell pole and imports exogenous DNAs (Kidane and Graumann, 2005; Kidane et al., 2012). RecA also associates with RecN, which attaches to the 3′-OH of ssDNA and might sequester the extreme end of the ssDNA within nucleoid structures (Sanchez and Alonso, 2005). The behavior of RecA in B. subtilis could represent a step in transformation for the inclusion of exogenous DNA into recipient genomic DNAs through recombination, and also suggest a role in conjugation.

Interestingly, the recipient yeast genes central to the HR process are also involved in AMT of yeast using a similar but different set of T-DNA plasmids. Rolloos et al. (2014) and Ohmine et al. (2016) performed yeast AMT using similar but different sets of model T-DNA plasmids having RB and LB borders. T-DNA circles were formed in the recipient yeast at high frequency. The yeast RAD51 gene is a homolog of the bacterial recA gene (Shinohara et al., 1992; Krogh and Symington, 2004), and Rad52 helps Rad51 to perform strand exchange in yeast (Shinohara and Ogawa, 1998). The AMT efficiency is decreased by rad51Δ and rad52Δ (Rolloos et al., 2014; Ohmine et al., 2016). The defect caused by these mutations seems to not be in simple HR because the hyper HR mutation srs2Δ does not increase but decreases AMT as seriously as rad52Δ (Ohmine et al., 2016). We have data that show the yeast srs2Δ mutation also has a similar apparent negative effect on the transfer of pSRK-R316 (Kiyokawa, personal communication).

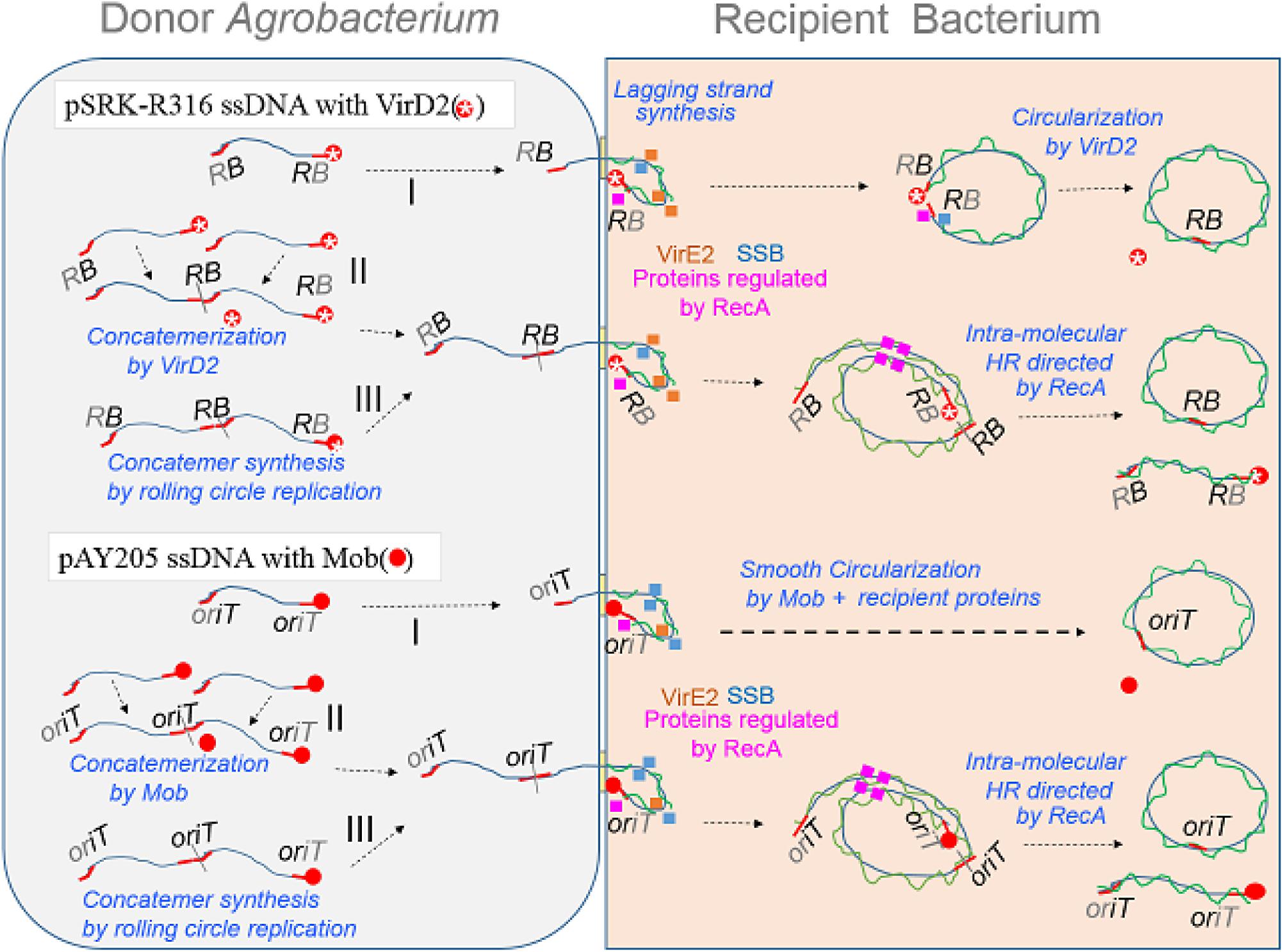

We suppose that the ssDNAs from donor cells are bound by RecA and by some proteins whose expression requires RecA (Fernandez De Henestrosa et al., 2000), and that these proteins help VirD2 and Mob to re-circularize the ssDNAs (Figure 7 pathway I). Because VirD2-driven yeast AMT and Mob-driven E. coli AMT were efficient, it is likely that the model T-DNA plasmid is easily transferred to E. coli cells. A plausible explanation for the low AMT efficiency in E. coli is that the plasmid circularization process that occurs through the DNA-joining activity of VirD2 (Pansegrau et al., 1993) proceeds only slowly in recipient E. coli cells, probably because of VirD2’s inability to associate with E. coli proteins, and therefore most transferred DNA molecules are degraded in the bacteria. In contrast, Mob can interact with recipient bacterial proteins better, and therefore perform AMT of bacteria efficiently, even though the in vitro ssDNA ligase ability of VirD2 (Pansegrau et al., 1993) looks much higher than that of Mob (Bhattacharjee and Meyer, 1991). Conversely, VirD2 is superior to Mob for yeast AMT, because VirD2 can interact well with several yeast proteins that are conserved among eukaryotes including plants.

FIGURE 7. Schematic models of AMT of bacteria with an emphasis on the DNA structure of transfer intermediates, relaxase and ssDNA binding proteins (SSB and VirE2). ssDNA covalently linked with a relaxase protein, either Mob (filled red circle) or VirD2 (red circle marked with a star), is formed by the action of the relaxase on its target plasmid DNA. Rolling circle replication produces a monomer (I) molecule with a relaxase at each 5′-terminus. The nucleoprotein is mobilized via a VirB/D4 channel to a recipient bacterium. Upon entry of the nucleoprotein molecule, DNA polymerase starts lagging strand synthesis. Simultaneously, ssDNA portions are bound by ssDNA binding proteins, namely VirE2 from the donor, recipient SSB, RecA and proteins whose expression is enhanced by RecA. Mob catalyzes re-circularization at high efficiency, while VirD2 re-circularizes less efficiently in the recipient bacterial cell. The nucleoprotein molecule in the donor cell can also participate in another process that was previously proposed for yeast AMT (Rolloos et al., 2014). Two molecules are merged to form a concatemer linked with a relaxase (II); this reaction releases a relaxase molecule. Rolling circle replication sometimes produces a concatemer (III) molecule having a relaxase at each 5’-terminus. The concatemers (II,III) enter the recipient bacterium and finally produce monomeric circles through HR directed by RecA.

In parallel with pathway I, which employs VirD2 and Mob proteins for the re-circularization in recipient cells, two other pathways are pictured in Figure 7. Figure 7 pathway II involves concatemer formation through merging two monomers by VirD2 and Mob in donor Agrobacterium cells, and then circularization by HR in recipient cells, as proposed by Rolloos et al. (2014). The last model (Figure 7 pathway III) involves no DNA-joining activity by any relaxase. In the formation of ssDNA, the cycle of monomeric ssDNA formation sometimes does not terminate and therefore generates multimeric forms of ssDNA, which could be turned into a monomer in recipient cells by HR.

YO conceived the study, performed most of the experiments, and wrote the draft manuscript. KK designed the study, performed most of the experiments, analyzed statistically, and finalized the manuscript. KY constructed plasmids, established and performed plasmid transfer experiments. SY provided strains and source plasmids, instructed the experiments, and finalized the manuscript. KM instructed the experiments, and finalized the manuscript. KS designed and instructed the whole body of the study. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

This work was financially supported in part by Grant-in-aids for scientific research from JSPS/MEXT (#15H04479 and 17K19240).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We are grateful to Hiroshi Ide at our school for discussion on the roles of Rec/Rad proteins. The E. coli recAΔ mutant in the Keio collection and its parental strain BW25113 were provided by the National BioResource Project Japan based on a material-transfer agreement.

AMT, Agrobacterium-mediated transformation; AS, acetosyringone; HR, homologous recombination; LB, left border of T-DNA; RB, right border of T-DNA; ss, single-strand; SSB, single-stranded DNA binding protein; T-DNA, transfer DNA region of Ti plasmids; T4SS, type IV secretion system; VirB/D4, channel composed of VirB proteins and VirD4 protein.

Alvarez-Martinez, C. E., and Christie, P. J. (2009). Biological diversity of prokaryotic type IV secretion systems. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73, 775–808. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00023-09

Baba, T., Ara, T., Hasegawa, M., Takai, Y., Okumura, Y., Baba, M., et al. (2006). Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050

Beijersbergen, A., Dulk-Ras, A. D., Schilperoort, R. A., and Hooykaas, P. J. (1992). Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Science 256, 1324–1327. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5061.1324

Bell, J. C., and Kowalczykowski, S. C. (2016). RecA: regulation and mechanism of a molecular search engine. Trends Biochem. Sci. 41, 491–507. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.04.002

Bevan, M. (1984). Binary Agrobacterium vectors for plant transformation. Nucleic Acids Res. 12, 8711–8721. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.22.8711

Bhattacharjee, M. K., and Meyer, R. J. (1991). A segment of a plasmid gene required for conjugal transfer encodes a site-specific, single-strand DNA endonuclease and ligase. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 1129–1137. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.5.1129

Binns, A. N., Beaupre, C. E., and Dale, E. M. (1995). Inhibition of VirB-mediated transfer of diverse substrates from Agrobacterium tumefaciens by the IncQ plasmid RSF1010. J. Bacteriol. 177, 4890–4899. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.17.4890-4899.1995

Bohne, J., Yim, A., and Binns, A. N. (1998). The Ti plasmid increases the efficiency of Agrobacterium tumefaciens as a recipient in virB-mediated conjugal transfer of an IncQ plasmid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7057–7062. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7057

Boyer, H. W., and Roulland-Dussoix, D. (1969). A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 41, 459–472. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90288-5

Brachmann, C. B., Davies, A., Cost, G. J., Caputo, E., Li, J., Hieter, P., et al. (1998). Designer deletion strains derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288C: a useful set of strains and plasmids for PCR-mediated gene disruption and other applications. Yeast 14, 115–132. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980130)14:2<115::AID-YEA204>3.0.CO;2-2

Bravo-Angel, A. M., Gloeckler, V., Hohn, B., and Tinland, B. (1999). Bacterial conjugation protein MobA mediates integration of complex DNA structures into plant cells. J. Bacteriol. 181, 5758–5765.

Bundock, P., den Dulk-Ras, A., Beijersbergen, A., and Hooykaas, P. J. (1995). Trans-kingdom T-DNA transfer from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 14, 3206–3214.

Christie, P. J., Whitaker, N., and Gonzalez-Rivera, C. (2014). Mechanism and structure of the bacterial type IV secretion systems. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1843, 1578–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.12.019

De Vos, G., and Zambryski, P. (1989). Expression of Agrobacterium nopaline-specific VirD1, VirD2, and VirC1 proteins and their requirement for T-strand production in E. coli. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2, 43–52. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-2-043

Dube, T., Kovalchuk, I., Hohn, B., and Thomson, J. A. (2004). Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of plants by the pTF-FC2 plasmid is efficient and strictly dependent on the MobA protein. Plant Mol. Biol. 55, 531–539. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-1159-1

Fernandez De Henestrosa, A. R., Ogi, T., Aoyagi, S., Chafin, D., Hayes, J. J., Ohmori, H., et al. (2000). Identification of additional genes belonging to the LexA regulon in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 35, 1560–1572. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01826.x

Firth, N., Ippen-Ihler, K., and Skurray, R. (1996). “Structure and function of the F factor and mechanism of conjugation,” in Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology, 2nd Edn, ed. F. C. Neidhardt (Washington, DC: ASM Press), 2377–2401.

Frey, J., and Bagdasarian, M. (1989). “The molecular biology of the IncQ plasmids,” in Promiscuous Plasmids of Gram Negative Bacteria, ed. C. M. Thomas (London: Academic Press), 79–94.

Fullner, K. J. (1998). Role of Agrobacterium virB genes in transfer of T complexes and RSF1010. J. Bacteriol. 180, 430–434.

Gelvin, S. B. (2012). Traversing the cell: Agrobacterium T-DNA’s journey to the host genome. Front. Plant Sci. 3:52. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2012.00052

Grant, S. G., Jessee, J., Bloom, F. R., and Hanahan, D. (1990). Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 4645–4649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4645

Hood, E. E., Murphy, J. M., and Pendleton, R. C. (1993). Molecular characterization of maize extensin expression. Plant Mol. Biol. 23, 685–695. doi: 10.1007/BF00021524

Ippen-Ihler, K., and Skurray, R. A. (1993). “Genetic organization of transfer-related determinants on the sex factor F and related plasmids,” in Bacterial Conjugation, ed. D. B. Clewell (New York, NY: Springer), 23–52.

Kelly, B. A., and Kado, C. I. (2002). Agrobacterium-mediated T-DNA transfer and integration into the chromosome of Streptomyces lividans. Mol. Plant Pathol. 3, 125–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2002.00104.x

Khan, S. R., Gaines, J., Roop, R. M., and Farrand, S. K. (2008). Broad-host-range expression vectors with tightly regulated promoters and their use to examine the influence of TraR and TraM expression on Ti plasmid quorum sensing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5053–5062. doi: 10.1128/Aem.01098-08

Kidane, D., Ayora, S., Sweasy, J. B., Graumann, P. L., and Alonso, J. C. (2012). The cell pole: the site of cross talk between the DNA uptake and genetic recombination machinery. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 47, 531–555. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2012.729562

Kidane, D., and Graumann, P. L. (2005). Intracellular protein and DNA dynamics in competent Bacillus subtilis cells. Cell 122, 73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.036

Kiyokawa, K., Yamamoto, S., Sakuma, K., Tanaka, K., Moriguchi, K., and Suzuki, K. (2009). Construction of disarmed Ti plasmids transferable between Escherichia coli and Agrobacterium species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 1845–1851. doi: 10.1128/Aem.01856-08

Kiyokawa, K., Yamamoto, S., Sato, Y., Momota, N., Tanaka, K., Moriguchi, K., et al. (2012). Yeast transformation mediated by Agrobacterium strains harboring an Ri plasmid: comparative study between GALLS of an Ri plasmid and virE of a Ti plasmid. Genes Cells 17, 597–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2012.01612.x

Krogh, B. O., and Symington, L. S. (2004). Recombination proteins in yeast. Annu. Rev. Genet. 38, 233–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.091500

Lacroix, B., Tzfira, T., Vainstein, A., and Citovsky, V. (2006). A case of promiscuity: Agrobacterium’s endless hunt for new partners. Trends Genet. 22, 29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.10.004

Lanka, W., and Pansegrau, W. (1999). “Genetic exchange between microorganisms,” in Biology of the Prokaryotes, eds J. W. Lengeler, G. Drews, and H. G. Schlegel (Stuutgart: Georg Thieme Verlag), 386–415.

Lawley, T., Frost, L., and Wilkins, B. M. (2004). “Bacterial conjugation in Gram-negative bacteria,” in Plasmid Biology, eds B. Funnell and G. Phillips (Washington, DC: ASM Press), 203–226.

Lawley, T. D., Klimke, W. A., Gubbins, M. J., and Frost, L. S. (2003). F factor conjugation is a true type IV secretion system. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 224, 1–15. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00430-0

Lessl, M., and Lanka, E. (1994). Common mechanisms in bacterial conjugation and Ti-mediated T-DNA transfer to plant cells. Cell 77, 321–324. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90146-5

Motohashi, K. (2015). A simple and efficient seamless DNA cloning method using SLiCE from Escherichia coli laboratory strains and its application to SLiP site-directed mutagenesis. BMC Biotechnol. 15:47. doi: 10.1186/s12896-015-0162-8

Nishikawa, M., Suzuki, K., and Yoshida, K. (1992). DNA integration into recipient yeast chromosomes by trans-kingdom conjugation between Escherichia coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 21, 101–108. doi: 10.1007/BF00318467

Ohmine, Y., Satoh, Y., Kiyokawa, K., Yamamoto, S., Moriguchi, K., and Suzuki, K. (2016). DNA repair genes RAD52 and SRS2, a cell wall synthesis regulator gene SMI1, and the membrane sterol synthesis scaffold gene ERG28 are important in efficient Agrobacterium-mediated yeast transformation with chromosomal T-DNA. BMC Microbiol. 16:58. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0672-0

Okegawa, Y., and Motohashi, K. (2015). Evaluation of seamless ligation cloning extract preparation methods from an Escherichia coli laboratory strain. Anal. Biochem. 486, 51–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.06.031

Pansegrau, W., and Lanka, E. (1991). Common sequence motifs in DNA relaxases and nick regions from a variety of DNA transfer systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:3455. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.12.3455

Pansegrau, W., Schoumacher, F., Hohn, B., and Lanka, E. (1993). Site-specific cleavage and joining of single-stranded DNA by VirD2 protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmids: analogy to bacterial conjugation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 11538–11542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11538

Rajagopala, S. V., Yamamoto, N., Zweifel, A. E., Nakamichi, T., Huang, H. K., Mendez-Rios, J. D., et al. (2010). The Escherichia coli K-12 ORFeome: a resource for comparative molecular microbiology. BMC Genomics 11:470. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-470

Rolloos, M., Dohmen, M. H., Hooykaas, P. J., and van der Zaal, B. J. (2014). Involvement of Rad52 in T-DNA circle formation during Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 91, 1240–1251. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12531

Sanchez, H., and Alonso, J. C. (2005). Bacillus subtilis RecN binds and protects 3′-single-stranded DNA extensions in the presence of ATP. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 2343–2350. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki533

Sawahel, W., Sastry, G., Knight, C., and Cove, D. (1993). Development of an electro-transformation system for Escherichia coli DH10B. Biotechnol. Tech. 7, 261–266. doi: 10.1007/Bf00150895

Schäfer, A., Tauch, A., Jäger, W., Kalinowski, J., Thierbach, G., and Pühler, A. (1994). Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145, 69–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90324-7

Scheiffele, P., Pansegrau, W., and Lanka, E. (1995). Initiation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens T-DNA processing. Purified proteins VirD1 and VirD2 catalyze site- and strand-specific cleavage of superhelical T-border DNA in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 1269–1276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1269

Scherzinger, E., Kruft, V., and Otto, S. (1993). Purification of the large mobilization protein of plasmid RSF1010 and characterization of its site-specific DNA-cleaving/DNA-joining activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 217, 929–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18323.x

Scholz, P., Haring, V., Wittmann-Liebold, B., Ashman, K., Bagdasarian, M., and Scherzinger, E. (1989). Complete nucleotide sequence and gene organization of the broad-host-range plasmid RSF1010. Gene 75, 271–288. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90273-4

Shinohara, A., Ogawa, H., and Ogawa, T. (1992). Rad51 protein involved in repair and recombination in S. cerevisiae is a RecA-like protein. Cell 69, 457–470. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90447-K

Shinohara, A., and Ogawa, T. (1998). Stimulation by Rad52 of yeast Rad51-mediated recombination. Nature 391, 404–407. doi: 10.1038/34943

Sikorski, R. S., and Hieter, P. (1989). A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122, 19–27.

Simon, R., Priefer, U., and Pühler, A. (1983). A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 1, 784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784

Simonsen, L., Gordon, D. M., Stewart, F. M., and Levin, B. R. (1990). Estimating the rate of plasmid transfer: an end-point method. J. Gen. Microbiol. 136, 2319–2325. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-11-2319

Smillie, C., Garcillan-Barcia, M. P., Francia, M. V., Rocha, E. P., and de la Cruz, F. (2010). Mobility of plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 434–452. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-10

Stahl, L. E., Jacobs, A., and Binns, A. N. (1998). The conjugal intermediate of plasmid RSF1010 inhibits Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulence and VirB-dependent export of VirE2. J. Bacteriol. 180, 3933–3939.

Suzuki, K., Tanaka, K., Yamamoto, S., Kiyokawa, K., Moriguchi, K., and Yoshida, K. (2009). “Ti and Ri plasmids,” in Microbial Megaplasmids, ed. E. Schwartz (Heidelberg: Springer Verlag), 133–147.

Vogel, A. M., and Das, A. (1992). Mutational analysis of Agrobacterium-tumefaciens virD2: tyrosine 29 is essential for endonuclease activity. J. Bacteriol. 174, 303–308. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.303-308.1992

Ward, E. R., and Barnes, W. M. (1988). VirD2 protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens very tightly linked to the 5′ end of T-strand DNA. Science 242, 927–930. doi: 10.1126/science.242.4880.927

Wong, J. J., Lu, J., and Glover, J. N. (2012). Relaxosome function and conjugation regulation in F-like plasmids - a structural biology perspective. Mol. Microbiol. 85, 602–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08131.x

Yamamoto, S., Uraji, M., Tanaka, K., Moriguchi, K., and Suzuki, K. (2007). Identification of pTi-SAKURA DNA region conferring enhancement of plasmid incompatibility and stability. Genes Genet. Syst. 82, 197–206. doi: 10.1266/ggs.82.197

Zambryski, P. C. (1992). Chronicles from the Agrobacterium-plant cell DNA transfer story. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 43, 465–490. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.43.060192.002341

Keywords: horizontal DNA transfer, conjugation, recA, T-DNA transfer, type 4 secretion system, Agrobacterium, relaxase, plasmid transfer

Citation: Ohmine Y, Kiyokawa K, Yunoki K, Yamamoto S, Moriguchi K and Suzuki K (2018) Successful Transfer of a Model T-DNA Plasmid to E. coli Revealed Its Dependence on Recipient RecA and the Preference of VirD2 Relaxase for Eukaryotes Rather Than Bacteria as Recipients. Front. Microbiol. 9:895. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00895

Received: 31 January 2018; Accepted: 18 April 2018;

Published: 28 May 2018.

Edited by:

Peng Luo, South China Sea Institute of Oceanology (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Francisco Dionisio, Universidade de Lisboa, PortugalCopyright © 2018 Ohmine, Kiyokawa, Yunoki, Yamamoto, Moriguchi and Suzuki. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Katsunori Suzuki, a3N1enVraUBoaXJvc2hpbWEtdS5hYy5qcA==

†Co-first author

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.