95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 01 February 2018

Sec. Virology

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00101

This article is part of the Research Topic Genome Invading RNA Networks View all 17 articles

We examine the hypothesis that de novo template-free RNAs still form spontaneously, as they did at the origins of life, invade modern genomes, contribute new genetic material. Previously, analyses of RNA secondary structures suggested that some RNAs resembling ancestral (t)RNAs formed recently de novo, other parasitic sequences cluster with rRNAs. Here positive control analyses of additional RNA secondary structures confirm ancestral and de novo statuses of RNA grouped according to secondary structure. Viroids with branched stems resemble de novo RNAs, rod-shaped viroids resemble rRNA secondary structures, independently of GC contents. 5′ UTR leading regions of West Nile and Dengue flavivirid viruses resemble de novo and rRNA structures, respectively. An RNA homologous with Megavirus, Dengue and West Nile genomes, copperhead snake microsatellites and levant cotton repeats, not templated by Mimivirus' genome, persists throughout Mimivirus' infection. Its secondary structure clusters with candidate de novo RNAs. The saltatory phyletic distribution and secondary structure of Mimivirus' peculiar RNA suggest occasional template-free polymerization of this sequence, rather than noncanonical transcriptions (swinger polymerization, posttranscriptional editing).

Diverse numbers of simple organic compounds spontaneously self-organized at life's origins. This system crystallized around the ribonucleic-protein system forming the main organizational building blocks of known organisms (Szostak, 2009; Ruiz-Mirazo et al., 2014). Then presumably the tRNA-rRNA information-storage/translation apparatus developed (Fox, 2010; Root-Bernstein and Root-Bernstein, 2015, 2016) through segment accretion (Di Giulio, 1992, 1994, 1995, 1999, 2008, 2009, 2012, 2013; Widmann et al., 2005; Branciamore and Di Giulio, 2011, 2012; Seligmann, 2014; Petrov et al., 2015). Presumably, self-replicating systems evolved, producing/parasitized by molecules lacking self-replication capacities (Bansho et al., 2012). The system potentially stabilized by evolving molecular cooperation between molecules with replicating capacities (Penny, 2015) and others lacking this capacity but contributing otherwise to the system's persistence (Higgs and Lehman, 2015). This process would have produced the modern translation/replication system(s).

Other molecules (short parasitic repeats, frequently forming stem-loop hairpins, viroids, viruses, etc.) presumably subsisted mainly as parasites and occasionally contributing new, sometimes functional parts. Persistence of the cooperative system implies integrating new molecules with new functions, while channeling most resources to critical components such as ribosomes. Nowadays, ribosomes compete with parasitic elements that hijack the cell's integrated cooperative system (Xie and Scully, 2017). Viruses frequently mimic cellular processes (Hiscox, 2007), including the cell's replication/transcription compartments (Chaikeeratisak et al., 2017). Hence when life began, ribosomal RNAs had virus-like properties. This arms race might explain why >95% of the cell's transcriptome consists of ribosomal RNA (Peano et al., 2013). Here we hypothesize that new RNAs still spontaneously emerge and integrate molecular cooperative systems of organisms.

We use several analyses, including comparisons among RNA secondary structures, to detect and test for de novo RNA emergence.

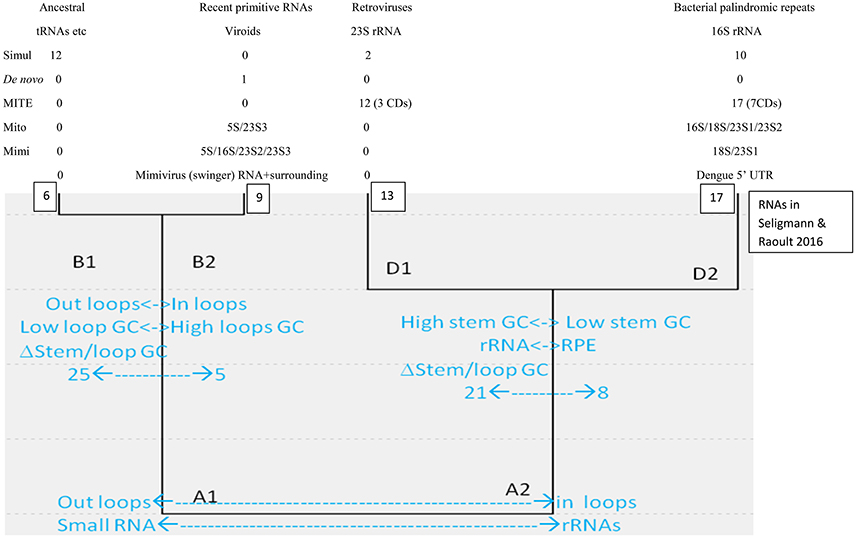

Classical sequence homology between linear sequences is inefficient at reconstructing ancient evolution because sequences evolve relatively fast. Structures, rather than sequences, are conserved for longer periods. For example, analyses considering structural homology among proteins suggest a common cellular ancestry for modern cells and viruses (Nasir and Caetano-Anollés, 2015). Similarly, analyses using simple properties of secondary structures formed by diverse RNAs detect two main clusters (A1 and A2, small vs. complex RNAs), each subdivided into two main groups (A1:B1-B2; A2:D1-D2), schematized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Hierarchical cluster of secondary structures formed by diverse RNA molecules, adapted from Seligmann and Raoult (2016).

Cluster B1 is the functionally most diverse group and includes several presumably ancestral RNAs, such as replication origin, tRNA and some ribozymes. Its “sister” cluster B2 includes diverse, probably more derived/recent molecules (i.e., the only known protein-encoding viroid, AbouHaidar et al., 2014). Clusters D1 and D2 are characterized by rRNA subunits, associated with parasitic RNAs: D1 includes all six 23S rRNA subunits and retroviruses; and D2 groups all 16S rRNA subunits and most families of RPEs, rickettsial palindromic elements, which infest specifically Rickettsia genomes (Amiri et al., 2002; Gillespie et al., 2012). Secondary structure similarities between parasitic and ribosomal RNAs underscore virus-like rRNA properties (Figure 1), presumably due to the assumed arms race between rRNAs and parasitic RNAs.

Cluster D2 includes half of the secondary structures formed by tRNA sequences. Hence B1–D2 would represent organic life's main tRNA-rRNA axis of molecular evolution, where simple ancestral tRNA-like RNAs complexified into rRNA-like RNAs (Bloch et al., 1983, 1984, 1989). This interpretation is in line with detections of candidate tRNA genes within mitochondrial 16S rRNA of chaetognath mitogenomes that otherwise would lack tRNAs (Barthélémy and Seligmann, 2016).

Here we analyze additional types of RNAs and explore their similarities with clusters B1-2/D1-2. Additional viroids, are analyzed to explore the possibility that some viroids date from the precellular world (Bussière et al., 1995; Diener, 1996) and others emerged de novo recently (Koonin and Dolja, 2013; Seligmann and Raoult, 2016), potentially solving the conundrum about primordial/recent de novo viroid origins (Diener, 2016). Two RNA types function as controls to confirm the statuses of putative ancestral/de novo clusters B1 and B2. The remaining RNAs originate from giant viruses and test putative evolutionary links between giant viruses and rRNAs.

Secondary structure predictions follow previous analyses (Seligmann and Raoult, 2016). Four variables are estimated from the optimal secondary structure predicted by Mfold (Zuker, 2003): 1. overall nucleotide percentage not involved in self-hybridization (loops); 2. percentage of nucleotides in closed loops at stem extremity among all nucleotides in loops (external loops); and 3. GC contents in loops, and 4. in stems. RNA size is not included among these variables.

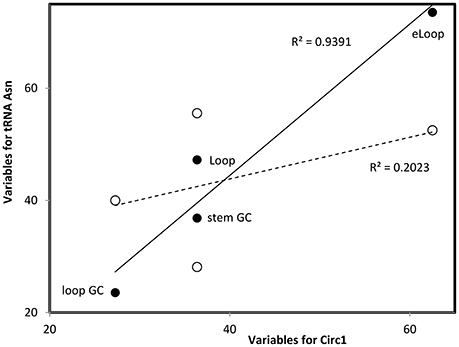

Table 1 presents these variables for sequences analyzed here. They are compared with corresponding data from a previous collection of RNA sequences (Seligmann and Raoult, 2016, therein Table 1 and Figure 2) that defined clusters in Figure 1. Comparisons use Pearson's correlation coefficient r as a similarity estimate, setting statistically significant similarity at r = 0.95 (one tailed P = 0.05). Correlation analyses plot each of the four variables 1–4 of Y for one of the new RNAs analyzed here as a function of corresponding variables 1–4 of X for each of previously analyzed RNAs (Seligmann and Raoult, 2016, therein Table 1). Correlation coefficients estimate similarities between X and Y according to variables 1–4 (example in Figure 2). Results of statistical analyses presented here are validated also by the Benjamini-Hochberg correction method for false discovery rates which accounts for multiple tests (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995; methodology detailed for unrelated analyses in Seligmann and Warthi, 2017). This test, unlike the classical Bonferroni approach that minimizes false positive detection rates and misses numerous positive results (Perneger, 1998) optimizes between false negative and false positive detection rates (Käll et al., 2007). The method is not affected by lack of independence between observations, and accounts for multiple testing. These additional analyses confirm classical statistics and therefore are not detailed in Results.

Figure 2. Multivariate comparisons between estimates of secondary structure variables for theoretical sequence Circ1 (from Table 1, x-axis) with corresponding variables for the cloverleaf (filled symbols, continous line) and OL-like (empty symbols, interrupted line) structures formed by the human mitochondrial tRNA Asn. Pearson correlation coefficients r = 0.969, P = 0.0; and r = 0.450, P < 0.05, respectively (values in the figure indicate the square of r). Such comparisons are calculated for each pair of secondary structures that are compared, RNAs are classified into secondary structure clusters (Figure 1) according to highest r.

Mimivirus' transcriptome (public data available at http://sra.dnanexus.com/studies/SRP001690/experiments; Legendre et al., 2010) are analyzed using CLCgenomicswb7. Reads are mapped on Mimivirus' reference genome NC_014649, according to the following criteria: at least half of the read maps to the reference genome, with at least 80% identity.

Previous analyses produced the classification scheme of secondary structures formed by RNAs in Figure 1. Secondary structures formed by selected RNAs are analyzed to test this scheme. We classified the secondary structures of 24 sequences produced in silico by Demongeot and Moreira (2007). These RNAs were generated by simulations designed to reconstruct likely short primordial genes. Simulations were constrained to produce circular RNAs with codons coding for all 20 amino acids and a stop codon, and to form a stem-loop hairpin. The resulting theoretical RNAs have consensual tRNA sequence properties (Demongeot and Moreira, 2007).

Optimal secondary structures of these 24 theoretical RNAs (Circ1-24, Table 1) are compared with optimal secondary structures formed by RNAs used previously (Seligmann and Raoult, 2016, therein Table 1) as shown for Circ1, in Figure 2. The secondary structure of Circ1 resembles the cloverleaf structure of tRNA Asn, and much less the OL-like structure formed by that tRNA sequence. Mitochondrial tRNAs form secondary structures that resemble mitochondrial light strand replication origins (OL), presumably function as OLs in OL absence (Desjardins and Morais, 1990; Seligmann and Labra, 2014).

Half of the 24 theoretical RNAs designed by simulations cluster with B1. Ten cluster with D2 (as shown in Figure 2), and the remaining two with D1. There are 24 × 6 = 144 comparisons between the 24 simulation-generated RNAs and the six RNAs in B1. Of these comparisons, 19 (13.2%) have Pearson correlation coefficients r with P < 0.05. Among the 24 × 17 = 408 comparisons with D2, 10 (2.45%) have P < 0.05. There are 24 × 13 = 312 comparisons with D1; only two (0.64%) have P < 0.05. No comparison between the 24 simulation-generated RNAs with D2 has P < 0.05. Hence our interpretation of B1 as representing secondary structures formed by ancestral RNAs agrees with the independent approach developed by Demongeot and Moreira (2007).

The fact that secondary structures formed by the 24 simulation-generated, presumably ancestral-like RNAs of Demongeot and Moreira (2007) preferentially cluster with B1 confirms the ancestral status of these theoretical RNAs and of cluster B1. The observation that translation/genetic code properties converge with tRNA sequence properties (Demongeot and Moreira, 2007) is also congruent with analyses of tRNAs along the principles of the natural circular code (Michel, 2012, 2013; El Soufi and Michel, 2014, 2015): a set of 20 codons overrepresented in coding vs. other frames of protein coding genes (Arquès and Michel, 1996), which enable coding frame retrieval (Ahmed et al., 2007, 2010; Michel and Seligmann, 2014). Results also fit a model of evolution of secondary structures into sequence signals such as codons (El Houmami and Seligmann, 2017).

Simulation-generated sequences such as those in the previous section are suboptimal to confirm the ancestral/de novo status of clusters B1/B2. We analyze the predicted optimal secondary structure formed by a short sequence that is synthesized template-free by a combination of three archaeal enzymes, including DNA polymerase PolB (Béguin et al., 2015). This sequence is by definition “de novo.” Its secondary structure properties most resemble those of an exceptional, protein-encoding viroid in cluster B2 (one tailed P = 0.034). This result is statistically significant also after considering multiple testing, using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction for false discovery rates that accounts for the number of tests done (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). This strengthens the status of cluster B2 as recent spontaneously generated RNAs.

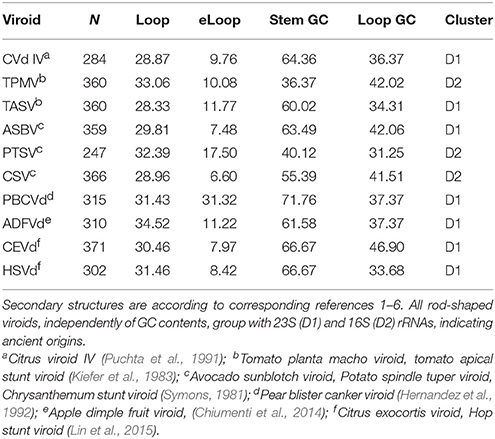

Evidence for recent vs. precellular origins of viroids are equivocal. Potentially, results of previous classifications of viroid secondary structures might be biased by including in analyses viroids with high GC contents and forming complex branching secondary structures. Analyses here include ten viroids forming rod-like secondary structures with GC contents ranging from 35 to 61%. All cluster with D1 and D2 (seven and three viroids, respectively, Table 2). No comparison with B1 and B2 has P < 0.05. Among 130 and 170 comparisons of these 10 rod-shaped viroids with secondary structures belonging to D1 and D2, 47 and 8 (36.2 and 4.7%, respectively), have P < 0.05.

Table 2. Secondary structure variables and classification of 10 viroids forming rod-shaped secondary structures.

Hence rod-shaped viroids belong to the ancestral tRNA-rRNA axis of molecular evolution. Viroids with more complex branching patters clustered with B2 according to previous analyses (Seligmann and Raoult, 2016). This suggests that viroid ‘survival’ requires evolutionary secondary structure simplification, perhaps because endonucleases target secondary branching (Fujishima et al., 2011). Results are compatible with mixed evidence for ancient precellular origins and recent de novo emergence of viroids.

Genomes of giant viruses include many inverted repeats forming stem-loop hairpins regulating transcription (Byrne et al., 2009; Claverie and Abergel, 2009), reminiscent of mitochondrial posttranscriptional tRNA punctuation (Ojala et al., 1981). These include miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements, MITEs (Fattash et al., 2013). The MITE family submarine in the giant virus Pandoravirus salinus presumably invaded that genome relatively recently (Sun et al., 2015).

We classified optimal secondary structures formed by these 29 MITE submarine sequences with clusters in Figure 1. No submarine MITE clusters within B1 or B2, but 12 cluster within D1 [11 among 377 comparisons (2.9%) with P < 0.05] and 17 cluster within D2 [30 among 493 comparisons (6.1%) with P < 0.05]. The 10 submarine MITE sequences integrated in Pandoravirus' protein coding genes cluster slightly more frequently with D2 than D1, as compared to the remaining submarine MITEs (difference not statistically significant). Hence most Pandoravirus submarine MITEs cluster with D2 (characterized by bacterial RPEs and 16S rRNA subunits), resembling RNAs from the main tRNA-rRNA axis. Under this scenario, similarities with D1 (characterized by retroviruses and 23S rRNA subunits) would result from chance or secondary convergences. However, this interpretation does not account for additional lateral transfers: many genes of giant viruses originate from lateral transfers, mainly from bacteria sharing their habitat in their amoeban host (Moliner et al., 2010; Georgiades and Raoult, 2012).

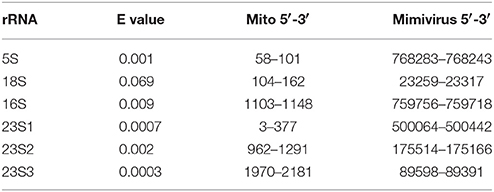

We used blastn (Altschul et al., 1997) to explore putative links between ribosomal RNAs and giant virus genomes. For that purpose we extracted rRNA sequences from Acanthamoeba castellanii's complete mitochondrial genome (NC_001637) and aligned these with Acanthamoeba polyphaga Mimivirus' complete genome (NC_014649). The amoeba's mitogenome includes four rRNA genes—5S, 16S, and 18S rRNAs—and a 23S-like sequence (Burger et al., 1995). Blastn alignment criteria were set at the shortest word size (7), the weakest match/mismatch scores (1/−1) and gap costs (existence 0; extension 2). For each rRNA we chose the alignment with the lowest (best) e value among the alignments detected by blastn between these mitochondrial rRNA genes and Mimivirus' genome (Table 3).

Table 3. Sequences aligned between Acanthamoeba castellani's mitochondrial rRNA genes and Acanthamoeba polyphaga Mimivirus' genome.

For 23S-like rRNA, three alignments are considered because they represent similarities with different Mimivirus sequences and the alignments have low e values. Secondary structures formed by four of the six rRNA sequences aligning with Mimivirus sequences cluster best with D2 and two sequences cluster best with B2 (Figure 1). Hence these rRNA sequences most resemble the cluster that includes bacterial 16S rRNA subunits.

These rRNA sequences aligned with sequences from the Mimivirus genome. These Mimivirus sequences also form secondary structures which cluster differently in Figure 1 than their putative amoeban mitochondrial rRNA homologs. Optimal secondary structures formed by four of the six corresponding Mimivirus DNA sequences cluster best with B2 and the remaining two with D2. Very few of the r coefficients used for these classifications have P < 0.05. Hence these results must be considered as tentative.

Differences in clustering by secondary structures formed by mitochondrial rRNA sequences vs. Mimivirus' genome for aligning sequence pairs suggest that alignments are frequently due to convergences between rRNAs and viral sequences. A possible interpretation of these clustering results (Table 1) is that viruses tend to create de novo rRNA-like sequences, though some of the alignments might suggest regular homology due to common ancestry. Lateral transfers between the host and Mimivirus is also a reasonable explanation. Independently of lateral transfers, this putative mitochondrial rRNA-Mimivirus homology is in line with common ancestry between Megavirales and a cellular ancestor of mitochondria, as suggested by homologies between polymerases of these organisms (Kempken et al., 1992; Rohe et al., 1992; Kapitonov and Jurka, 2006; Yutin et al., 2013; Krupovic and Koonin, 2016; Koonin and Krupovic, 2017) and above noted similar regulations of posttranscriptional processing (vertebrate mitochondria, Ojala et al., 1981; Claverie and Abergel, 2009; Mimivirus, Byrne et al., 2009). Hence secondary structure analyses apparently strengthen the hypothesis that mitochondria share a common ancestor with Megavirales.

Analysis of conserved secondary structures formed by 3′ and 5′ RNA structures in four flavivirid viruses [Dengue (DENV), West Nile (WNV), Japanese encephalitis (JEV) and tick-borne encephalitis (YFV) viruses, Brinton and Basu, 2015; therein Figure 1B, secondary structure variables here in Table 1] show that these structures cluster with D1 (characterized by 23S rRNA subunits). Hence these Flavivirus sequences crucial to replication form structures that resemble 23S rRNA, as observed for most rod-shaped viroids (section Ancient and de novo Viroids). Most Pandoravirus MITE sequences resemble D2, characterized by 16S rRNA (section Pandoravirus' Miniature Inverted-Repeat Transposable Elements, Mite) and some Mimivirus sequences resembling mitochondrial rRNAs cluster within D2 (section Ribosomal RNA-Like Mimivirus Sequences). Overall results indicate the hypothesized link between viral RNAs and rRNAs.

Mimivirus' transcriptome [data from (Legendre et al., 2010), available at: http://sra.dnanexus.com/studies/SRP001690/experiments] includes numerous short RNAs that are not homologous to Mimivirus' genome. Here we focus on a 42-nucleotide-long sequence (5′-GAGACACGCAACAGGGGATAGGCAAGGCACACAGGGGATAGG-3′) because this sequence also occurs according to Blastn in diverse taxa: Megavirus, Dengue and West Nile genomes, copperhead snake microsatellites and levant cotton repeats. This Mimivirus RNA matches the giant virus Megavirus terra1 (KF527229, positions 903759-903800) and some (not all) genomes of Dengue and West Nile viruses (both are Flaviviridae). In these Flaviviridae, the sequence is inserted in (or close to) the 5′ UTR leading region. The e value of alignments between Mimivirus' RNA and the flavivirid 5′ UTR sequences is 2 × 10−11. This RNA is detected by Blastn (word size 7; Match/Mismatch scores 1,−1; Gap costs, existence 1, extension 1) in Mimivirus' transcriptome throughout amoeban infection: −15, 0, 90, 180, 360a,b, 540, and 720 min after infection. This RNA does not map on any region of Mimivirus' genome.

This RNA not templated by Mimivirus' genome might originate from accidental contamination. However, three arguments suggest less conventional hypotheses. Firstly, this RNA is repeatedly detected throughout the virus' infection cycle, hence in different sequencing events. Secondly, the exact same RNA is detected each time in terms of sequence and length. Thirdly, this exact sequence occurs in the genome of another giant virus, Megavirus terra1. These arguments suggest that the occurrence of this RNA in Mimivirus' transcriptome is not circumstantial.

This RNA could originate from (a) de novo creation, as suggested for some short stem-loop hairpin RNAs (Seligmann and Raoult, 2016) and analyses in previous sections, (b) pools of vertically transmitted RNAs originating from horizontal transfers (Stedman, 2013) forming quasi species groups (Villarreal, 2015, 2016), or (c) noncanonical transcriptions of genomic DNA, such as RDDs [RNA-DNA differences, which result from posttranscriptional nucleotide substitutions (Li et al., 2011) or indels (insertions/deletions, Chen and Bundschuh, 2012)]. In addition, this RNA might result from a peculiar type of transcription, which produces transcripts matching genomes only if one assumes that transcription systematically exchanges nucleotides over the whole length of the transcript, which is called swinger transcription. There are 23 possible nucleotide exchange rules, 9 are symmetric exchanges of type X<->Y and 14 are asymmetric exchanges of the type X->Y->Z->X. These 23 transformations are each separately applied in silico to Mimivirus' genome to produce 23 swinger-transformed versions of that genome which are used for further analyses. Current information on systematic nucleotide exchanges is reviewed by Seligmann (2017), with further references therein (see also Seligmann, 2013; Michel and Seligmann, 2014).

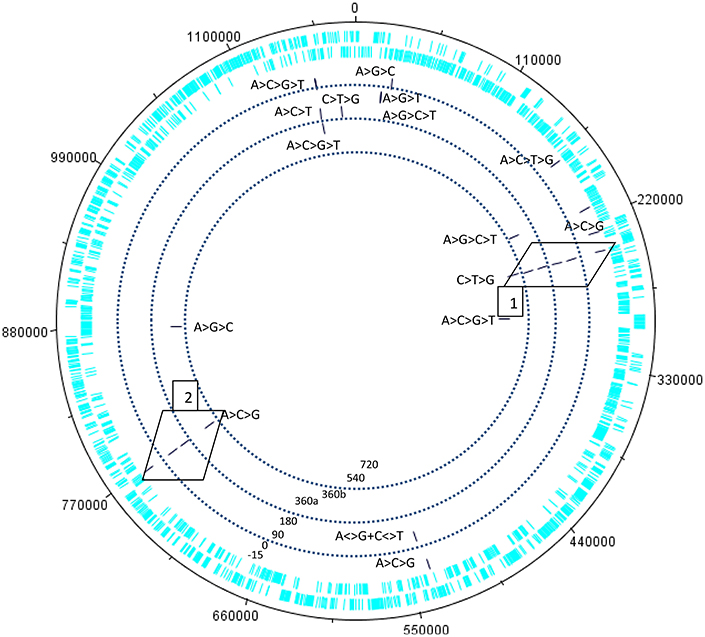

Our preliminary explorations of the kinetic data of the transcriptome of the giant virus Mimivirus (Raoult et al., 2004; Legendre et al., 2010, 2011) detected putative swinger RNAs among RNAs that do not match the regular genome sequence, after excluding regular RNAs by mapping on the regular genome (Figures 3–5). Table 4 compares abundances and mean lengths of detected putative swinger RNAs among transcriptomic data produced by 454 and SOLID massive sequencing techniques (SOLID data unpublished, available in our laboratory). Results by both techniques are comparable. Abundances estimated from 454 sequencing correlate positively with those produced by SOLID (Spearman rank nonparametric correlation rs = 0.323, one tailed P = 0.066). Similarly, mean lengths of swinger reads correlate positively for data produced by 454 and SOLID (rs = 0.394, one tailed P = 0.082). Combining P-values from these two tests using Fisher's method for combining P values (Fisher, 1950), which sums −2 × ln(Pi) where i ranges from 1 to k tests (here k = 2) yields a chisquare statistic with 2 × k degrees of freedoms with a combined P = 0.034. Hence results from both sequencing methods are overall congruent, swinger RNAs are not artifacts resulting from massive sequencing technologies.

Figure 3. Kinetics of the swinger transcriptome (asymmetric nucleotide exchanges) of Mimivirus. Concentric circles indicate different periods in the cycle of Mimivirus. Bars indicate swinger RNAs detected for a given genomic region, the swinger transformation rule is indicated next to the bar. Swinger RNAs in boxes 1 and 2 are the exact inverse complements of each other, and correspond to the 5′ UTR leading region of Dengue and West Nile viruses.

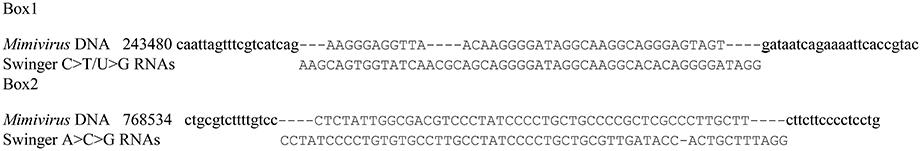

Within 454 data, two swinger RNAs (boxes in Figure 4, primary and secondary structures in Figures 4, 5) were detected throughout most of the viral cycle, corresponding to genomic sequences at positions 243499-243537 (C->T->G->C swinger rule, box 1 in Figure 3) and 768549-768596 (A->C->G->A swinger rule, box 2 in Figure 4). These two genomic positions are each other's inverse complement. This is also the case for the corresponding swinger RNA reads. These reads correspond to the aforementioned template-free RNA and are homologous with Megavirus terra1 (KF527229: positions 903764-903800). This candidate swinger RNA aligns only with swinger transformed versions of Mimivirus' genomic sequence, but its similarity with the swinger transformed genome is also low.

Figure 4. Alignment between sequence in Boxes 1 and 2 (Figure 3) and homologous sequences: Mimivirus reference genome sequence.Underlined are the detected swinger RNA sequences. Small caps indicate neighboring sequences that are not transformed by nucleotide exchange.

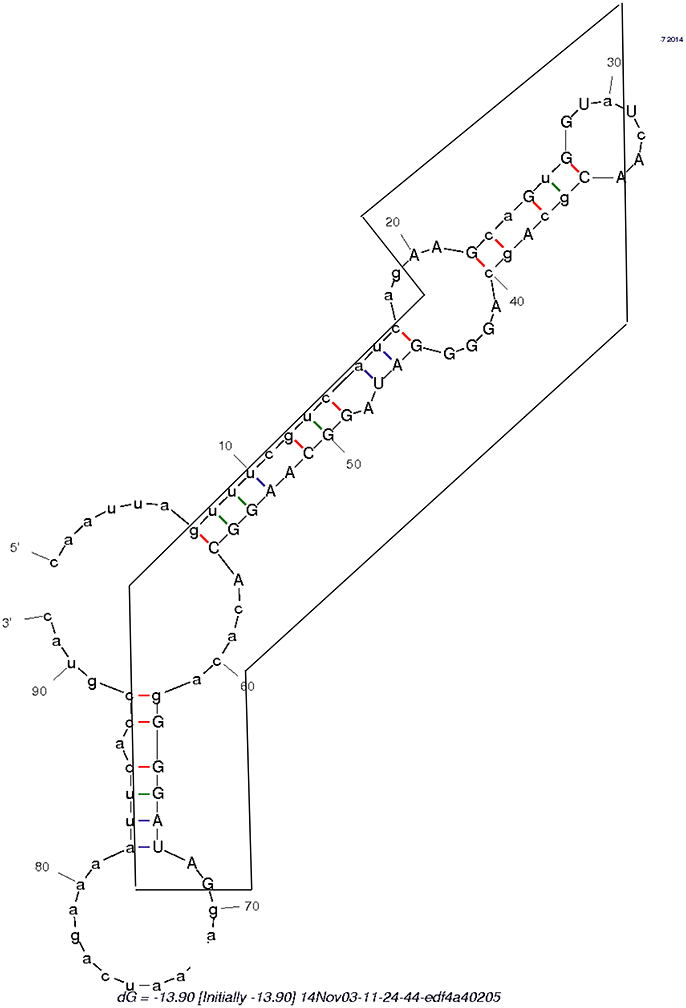

Figure 5. Secondary structure formed by the swinger C>T/U>G RNA (in box) and its untransformed neighboring regions.

Putatively, some genomic sequences in Mimivirus could originate from horizontal transfers from other viruses, suggesting a potential implication in the horizontal transfer of the Sputnik virophage that infests Mimivirus (La Scola et al., 2008). This is in line with the chimeric origin of most Mimivirus genes (originating from eukaryotic hosts and bacterial co-parasites of the eukaryotic host, Moreira and Brochier-Armanet, 2008; Jeudy et al., 2012), and confirms horizontal transfer of other viral sequences (Yutin et al., 2013), via swinger transformations.

Analyses that integrate molecular structure information are surprisingly successful at resolving various biological problems, notably of ancient evolution (for example the presumed monophyletic cellular origin of viruses, Nasir and Caetano-Anollés, 2015). However, techniques enabling this remain relatively inaccessible, notably for RNAs. This situation is particularly true if analyzes are supposed to integrate nonequilibrium dynamics of folding during the synthesis of the molecule [proteins: cotranslational folding, (Holtkamp et al., 2015; Seligmann and Warthi, 2017); RNAs: cotranscriptional folding, Gong et al., 2017]. Indeed, most RNAs fold during their syntheses, the new fold appearing after a new stretch of nucleotides is added to the elongating RNA (Schroeder et al., 2002). Each new fold is partially constrained by the previous one, which renders prediction algorithms more complex (Zhao et al., 2010; Frieda and Block, 2012).

The approach used here does not require any special computational skills. It could be adapted to dynamical contexts, and to include information on groups of closely related, suboptimal secondary structures, when these are only slightly more unstable than the optimal structure. Previous analyses (Seligmann and Raoult, 2016) included such special cases, for mitochondrial tRNAs in their classical cloverleaf fold, and in their replication origin (OL)-like fold. Analyzes separating different folds with similar stabilities for structures formed by the same sequence, such as cloverleaf vs. OL-like tRNA structures, yield sometimes different results in classifications such as that in Figure 1 (see Seligmann and Raoult, 2016, therein Figure 2).

In addition, molecules with very similar estimates for all variables may form very different structures, or similar structures of very different sizes (the variables do not include sequence length). Hence the simple approach used here could be applied to study closely related clouds of secondary structures formed by a given RNA. It could also be adapted to discriminate further between similar secondary structures by including additional variables, such as GC contents in internal vs. external loops, and angular rotation between stem branches.

Overall our results indicate that the versatility of RNA structures enable for functional novelties. Their physicochemical properties are also compatible with this role in primitive protolife organic conditions.

Interpretations of a previous classification of RNA secondary structures formed by a variety of RNAs (Seligmann and Raoult, 2016) were tested by classifying specific RNAs of special interest. For example, circular RNAs generated by simulations presumably mimicking ancestral RNAs cluster mainly, as expected, with cluster B1, a presumed group of ancestral RNAs (Figure 1).

Cluster B2 was previously interpreted as representing de novo emerged RNAs because it grouped short simple RNAs from very different functional types (tRNAs, ribozymes, viroids, etc.). Secondary structures formed by a sequence synthesized template free (hence de novo) cluster with B2.

Rodshaped viroids from a wide range of GC contents belong independently of GC contents to D1 and D2, two clusters characterized by rRNAs and parasitic sequences. Viroids forming secondary structures characterized by more complex branching patterns belong to cluster B2 (putative de novo RNAs). Hence results suggest that some viroids are recent, rodshaped ones are presumably ancient RNAs.

Presumed parasitic palindromic sequences from Pandoravirus (MITE submarine family) resemble cluster D2. D2 is characterized by16S rRNA subunits and Rickettsial palindromic elements that parasitize Rickettsia genomes. This fits previous grouping of secondary structures formed by parasitic sequences with 23S and 16S rRNAs (clusters D1 and D2).

Mimivirus sequences that align with amoeaban mitochondrial rRNA genes also strengthen suspected evolutionary links between rRNA and viral sequences. Mitochondrial rRNA sequences aligning with Mimivirus sequences cluster as expected with D2, characterized by bacterial 16S rRNA. Interestingly, secondary structures formed by Mimivirus sequences with which the mitochondrial rRNAs align, cluster mainly with B2, suggesting recent de novo origins for viral sequences resembling rRNAs. These results are based on relatively weak similarities and hence can only be considered as preliminary. Nevertheless, they suggest that viruses produce rRNA-like sequences, in line with the prediction that the study of giant viruses will ‘change current conceptions of life, diversity and evolution’ (Abrahao et al., 2014).

The secondary structure formed by the 5′ UTR leading region of flavivirid viruses clusters also with D2, hence it is a further viral, rRNA-like sequence. An RNA persisting throughout Mimivirus' infection cycle and lacking homology with Mimivirus' genome occurs also in some flavivirus genomes, Megavirus, in copperhead snakes and levant cotton. This saltatory phylogenetic distribution is compatible with repeated spontaneous, template free synthesis by polymerases deterministically producing specific sequences, as observed in Archaea (Béguin et al., 2015). Indeed, this RNA, embedded in the surrounding regular 5′ and 3′ sequences (Table 1 and Figure 5), forms a secondary structure that clusters with B2. This would suggest de novo emergence of this unusual RNA.

Analyses assuming different scenarios based on noncanonical transcriptions do not reach clear-cut conclusions on the origin of that RNA that does not map to the Mimivirus genome. Though contamination cannot be totally excluded, other hypotheses seem plausible. Indeed, this RNA maps imperfectly on Mimivirus' swinger-transformed genome (Mimivirus' transcriptome includes numerous swinger RNAs, results from each 454 and SOLID massive sequencing methods are congruent). Overall, results hint that parasitic RNAs form rRNA-like secondary structures, and template free polymerizations apparently enrich genomes with new RNA/DNA sequences.

HS and DR designed the study and analyses.

This study was supported by Méditerranée Infection and the National Research Agency under the program “Investissements d'avenir,” reference ANR-10-IAHU-03 and the A*MIDEX project (no ANR-11-IDEX-0001-02). We thank Thi Tien Nguyen for technical help.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

AbouHaidar, M. G., Venkataraman, S., Golshani, A., Liu, B., and Ahmad, T. (2014). Novel coding, translation, and gene expression of a replicating covalently closed circular RNA of 220 nt. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 14542–14547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402814111

Abrahao, J. S., Dornas, F. P., Silva, L. C., Almeida, G. M., Boratto, P. V., Colson, P., et al. (2014). Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus and other giant viruses: an open field to outstanding discoveries. Virol. J. 11:120. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-120

Ahmed, A., Frey, G., and Michel, C. J. (2007). Frameshift signals in genes associated with the circular code. In Silico Biol. 7, 155–168.

Ahmed, A., Frey, G., and Michel, C. J. (2010). Essential molecular functions associated with the circular code evolution. J. Theor. Biol. 264, 613–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.02.006

Altschul, S. F., Madden, T. L., Schaeffer, A. A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., et al. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389

Amiri, H., Alsmark, C. M., and Anderson, S. G. (2002). Proliferation and deterioration of Rickettsia palindromic elements. Mol. Evol. Biol. 19, 1234–1243. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004184

Arquès, D. G., and Michel, C. J. (1996). A complementary circular code in the protein coding genes. J. Theor. Biol. 182, 45–58. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1996.0142

Bansho, Y., Ichihashi, N., Kazuta, Y., Matsuura, T., Suzuki, H., and Yomo, T. (2012). Importance of parasite RNA species repression for prolonged translation-coupled RNA self-replication. Chemistry Biol. 19, 478–487. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.01.019

Barthélémy, R. M., and Seligmann, H. (2016). Cryptic tRNAs in chaetognath mitochondrial genomes. Comput. Biol. Chem. 62, 119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2016.04.007

Béguin, P., Gill, S., Charpin, N., and Forterre, P. (2015). Synergistic template-free synthesis of dsDNA by Thermococcus nautili primase PolpTN2, DNA polymerase PolB, and pTN2 helicase. Extremophiles 19, 69–76. doi: 10.1007/s00792-014-0706-1

Benjamini, Y., and Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B 27, 289–300.

Bloch, D. P., McArthur, B., Guimaraes, R. C., Smith, J., and Staves, M. P. (1989). tRNA-rRNA sequence matches inter- and intraspecies comparisons suggest common origins for the two RNAs. Braz. J. Med. Biol. 22, 931–944.

Bloch, D. P., McArthur, B., Widdowson, R., Spector, D., Guimaraes, R. C., and Smith, J. (1983). tRNA-rRNA sequence homologies: evidence for a common evolutionary origin? J. Mol. Evol. 19, 420–428. doi: 10.1007/BF02102317

Bloch, D. P., McArthur, B., Widdowson, R., Spector, D., Guimaraes, R. C., and Smith, J. (1984). tRNA-rRNA sequence homologies: a model for the origin of a common ancestral molecule, and prospects for its reconstruction. Orig. Life 14, 571–578. doi: 10.1007/BF00933706

Branciamore, S., and Di Giulio, M. (2011). The presence in tRNA molecule sequences of the double hairpin, an evolutionary stage through which the origin of this molecule is thought to have passed. J. Mol. Evol. 72, 352–363. doi: 10.1007/s00239-011-9440-9

Branciamore, S., and Di Giulio, M. (2012). The origin of the 5s ribosomal RNA molecule could have been caused by a single inverse duplication: strong evidence from its sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 74, 170–186. doi: 10.1007/s00239-012-9497-0

Brinton, M. A., and Basu, M. (2015). Functions of the 3′ and 5′ genome regions of members of the genus Flavivirus. Virus Res. 206, 108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.02.006

Burger, G., Plante, I., Lonergan, K. M., and Gray, M. W. (1995). The mitochondrial DNA of the amoeboid protozoon, Acanthamoeba castellanii: complete sequence, gene content and genome organization. J. Mol. Biol. 245, 522–537. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.0043

Bussière, F., Lafontaine, D., Côté, F., Beaudry, D., and Perreault, J. P. (1995). Evidence for a model ancetsral viroid. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1995, 143–144.

Byrne, D., Grzela, R., Larigue, A., Audic, S., Chenivesse, S., Encinas, S., et al. (2009). The polyadelynaton site of Mimivirus transcripts obeys a stringent “hairpin rule”. Genome Res. 19, 1233–1242. doi: 10.1101/gr.091561.109

Chaikeeratisak, V., Nguyen, K., Khanna, K., Brilot, A. F., Erb, M. L., Coker, J. K. C., et al. (2017). Assembly of a nucleus-like structure during viral replication in bacteria. Science 355, 194–197. doi: 10.1126/science.aal2130

Chen, C., and Bundschuh, R. (2012). Systematic investigation of insertional and deletional RNA–DNA differences in the human transcriptome. BMC Genomics 13:616. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-616

Chiumenti, M., Torchetti, E. M., Di Serio, F., and Minafra, A. (2014). Identification and characterization of a viroid resembling apple dimple fruit viroid in fig (Ficus carica L.) by next generation sequencing of small RNAs. Virus Res. 188, 54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.03.026

Claverie, J. M., and Abergel, C. (2009). Mimivirus and its virophage. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 49–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134255

Demongeot, J., and Moreira, A. (2007). A possible circular RNA at the origin of life. J. Theor. Biol. 249, 314–324. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2007.07.010

Desjardins, P., and Morais, R. (1990). Sequence and gene organization of the chicken mitochondrial genome. A novel gene order in higher vertebrates. J. Mol. Biol. 2012, 599–634. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90225-B

Di Giulio, M. (1992). The evolution of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, the biosynthetic pathways of amino acids and the genetic code. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 22, 309–319. doi: 10.1007/BF01810859

Di Giulio, M. (1994). The phylogeny of tRNA molecules and the origin of the genetic code. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 24, 425–434. doi: 10.1007/BF01582018

Di Giulio, M. (1995). Was it an ancient gene codifying for a hairpin RNA that, by means of direct duplication, gave rise to the primitive tRNA molecule? J. Theor. Biol. 177, 95–101. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5193(05)80007-4

Di Giulio, M. (1999). The non-monophyletic origin of the tRNA molecule. J. Theor. Biol. 197, 403–414. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1998.0882

Di Giulio, M. (2008). The split genes of Nanoarchaeum equitans are an ancestral character. Gene 421, 20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.06.010

Di Giulio, M. (2009). Formal proof that the split genes of tRNAs of Nanoarchaeum equitans are an ancestral character. J. Mol. Evol. 69, 505–511. doi: 10.1007/s00239-009-9280-z

Di Giulio, M. (2012). The ‘recently’ split transfer RNA genes may be close to merging the two halves of the tRNA rather than having just separated them. J. Theor. Biol. 310, 1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.06.022

Di Giulio, M. (2013). A polyphyletic model for the origin of tRNAs has more support than a monophyletic model. J. Theor. Biol. 318, 124–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.11.012

Diener, T. O. (1996). Origin and evolution of viroids and viroid-like satellite RNAs. Virus Genes 11, 119–131. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1407-3_5

Diener, T. O. (2016). Viroids: “living fossils” of primordial RNAs? Biol. Direct 11, 15. doi: 10.1186/s13062-016-0116-7

El Houmami, N., and Seligmann, H. (2017). Evolution of nucleotide punctuation marks: from structural to linear signals. Front. Genet. 8:36. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2017.00036

El Soufi, K., and Michel, C. J. (2014). Circular code motifs in the ribosome decoding center. Comput. Biol. Chem. 52, 9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2014.08.001

El Soufi, K., and Michel, C. J. (2015). Circular code motifs near the ribosome decoding center. Comput. Biol. Chem. 59A, 158–176. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2015.07.015

Fattash, I., Rooke, R., Wong, A., Hui, C., Luu, T., Bhardwaj, P., et al. (2013). Miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements: discovery, distribution, and activity. Genome 56, 475–486. doi: 10.1139/gen-2012-0174

Fox, G. E. (2010). Origin and evolution of the ribosome. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2:a003483. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003483

Frieda, K. L., and Block, S. M. (2012). Direct observation of cotranscriptional folding in an adenine riboswitch. Science 338, 397–400. doi: 10.1126/science.1225722

Fujishima, K., Sugihara, J., Miller, C. S., Baker, B. J., Di Giulio, M., Takesue, K., et al. (2011). A novel three-unit tRNA splicing endonuclease found in ultrasmall Archaea possesses broad substrate specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 9695–9704. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr692

Gale, M., Tan, S. L., and Katze, M. G. (2000). Translational control of viral gene expression in eukaryotes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 239–280. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.2.239-280.2000

Georgiades, K., and Raoult, D. (2012). How microbiology helps defined the rhizome of life. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2:60. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00060

Gillespie, J. J., Joardar, V., Williams, K. P., Driscoll, T., Hostetler, J. B., Nordberg, E., et al. (2012). A Rickettsia genome overrun by mobile genetic elements provides insight into the acquisition of genes characteristic of an obligate intracellular lifestyle. J. Bacteriol. 194, 376–394. doi: 10.1128/JB.06244-11

Gong, S., Wang, Y., Wang, Z., and Zhang, W. (2017). Computational methods for modeling aptamers and designing riboswitches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18:2442. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112442

Hernandez, C., Elena, S. F., Moya, A., and Flores, R. (1992). Pear blister canker viroid is a member of the apple scar skin subgroup (apscaviroids) and also has sequence homology with viroids from other subgroups. J. Gen. Virol. 73, 2503–2507. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-10-2503

Higgs, P. G., and Lehman, N. (2015). The RNA world: molecular cooperation at the origins of life. Nat. Rev. Genet. 16, 7–17. doi: 10.1038/nrg3841

Hiscox, J. A. (2007). RNA viruses: hijacking the dynamic nucleolus. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 5, 119–127. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1597

Holtkamp, W., Kokic, G., Jäger, M., Mittelstaet, J., Komar, A. A., and Rodnina, M. V. (2015). Cotranslational protein folding on the ribosome monitored in real time. Science 350, 1104–1107. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0344

Jeudy, S., Abergel, C., Claverie, J. M., and Legendre, M. (2012). Translation in giant viruses: a unique mixture of bacterial and eukaryotic termination schemes. PLoS Genet. 8:e1003122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003122

Käll, L., Storey, J. D., MacCoss, M. J., and Noble, W. S. (2007). Posterior error probabilities and false discovery rates: two sides of the same coin. J. Prot. 7, 40–44. doi: 10.1021/pr700739d

Kapitonov, V. V., and Jurka, J. (2006). Self-synthesizing DNA transposons in eukaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 4540–4545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600833103

Kempken, F., Hermanns, J., and Osiewacz, H. D. (1992). Evolution of linear plasmids. J. Mol. Evol. 35, 502–513. doi: 10.1007/BF00160211

Kiefer, M. C., Owens, R. A., and Diener, T. O. (1983). Structural similarities between viroids and transposable genetic elements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80, 6234–6238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.20.6234

Koonin, E. V., and Dolja, V. V. (2013). A virocentric perspective on the evolution of life. Curr. Opin. Virol. 3, 546–557. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.06.008

Koonin, E. V., and Krupovic, M. (2017). Polintons, virophages and transpovirons: a tangled web linking viruses, transposons and immunity. Curr. Opin. Virol. 25, 7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2017.06.008

Krupovic, M., and Koonin, E. V. (2016). Self-synthesizing transposons: unexpected key players in the evolution of viruses and defense systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 31, 25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.01.006

La Scola, B., Desnues, C., Pagnier, I., Robert, C., Barrassi, L., Fournous, G., et al. (2008). The virophage as a unique parasite of the giant Mimivirus. Nature 455, 100–104. doi: 10.1038/nature07218

Legendre, M., Audic, S., Poirot, O., Hingamp, P., Seltzer, V., Byrne, D., et al. (2010). mRNA deep sequencing reveals 75 new genes and a complex transcriptional landscape in Mimivirus. Genome Res. 20, 664–674. doi: 10.1101/gr.102582.109

Legendre, M., Santini, S., Rico, A., Abergel, C., and Claverie, J. M. (2011). Breaking the 1000-gene barrier for Mimivirus using ultra-deep genome and transcriptome sequencing. Virol. J. 8:99. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-99

Li, M., Wang, I. X., Li, Y., Bruzel, A., Richards, A. L., and Tug, J. M. (2011). Widespread RNA and DNA sequence differences in the human transcriptome. Science 333, 53–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1207018

Lin, C. Y., Wu, M. L., Shen, T. L., Yeh, H. H., and Hung, T. H. (2015). Multiplex detection, distribution, and genetic diversity of Hop stunt viroid and Citrus exocortis viroid infecting citrus in Taiwan. Virol. J. 12, 11. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0247-y

Michel, C. J. (2012). Circular code motifs in transfer and 16S ribosomal RNAs: a possible translation code in genes. Comput. Biol. Chem. 37, 24–37. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2011.10.002

Michel, C. J. (2013). Circular code motifs in transfer RNAs. Comput. Biol. Chem. 45, 17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2013.02.004

Michel, C. J., and Seligmann, H. (2014). Bijective transformation circular codes and nucleotide exchanging RNA transcription. Biosystems 118, 39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2014.02.002

Moliner, C., Fournier, P. E., and Raoult, D. (2010). Genome analysis of microorganisms living in amoebae reveals a melting pot of evolution. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34, 281–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00209.x

Moreira, D., and Brochier-Armanet, C. (2008). Giant viruses, giant chimeras: the multiple evolutionary histories of Mimivirus genes. BMC Evol. Biol. 8:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-12

Nasir, A., and Caetano-Anollés, G. (2015). A phylogenomic data-driven exploration of viral origins and evolution. Science Adv. 1:e1500527. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500527

Ojala, D., Montoya, J., and Attardi, G. (1981). tRNA punctuation model of RNA processing in human mitochondria. Nature 290, 470–474. doi: 10.1038/290470a0

Peano, C., Pietrelli, A., Consolandi, C., Rossi, E., Petiti, L., Tagliabue, L., et al. (2013). An efficient rRNA removal method for RNA sequencing in GC-rich bacteria. Microb. Inform. Exp. 3:1. doi: 10.1186/2042-5783-3-1

Penny, D. (2015). Cooperation and selfishness both occur during molecular evolution. Biol. Direct 10:26. doi: 10.1186/s13062-014-0026-5

Perneger, T. V. (1998). What's wrong with Bonferroni adjustments? BMJ 318:1236. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1236

Petrov, A. S., Gulen, B., Norris, A. M., Kovaxs, N. A., Berbier, C. R., Lanier, K. A., et al. (2015). History of the ribosome and the origin of translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 15396–15401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509761112

Puchta, H., Ramm, K., Luckinger, R., Hadas, R., Bar-Joseph, M., and Saenger, H. L. (1991). Primary and secondary structure of citrus viroid IV (CVd IV), a new chimeric viroid present in dwarfed grapefruit in Israel. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:6640. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.23.6640

Raoult, D., Audic, S., Robert, C., Abergel, C., Renesto, P., Ogata, H., et al. (2004). The 1.2-megabase genome sequence of Mimivirus. Science 305, 1344–1350. doi: 10.1126/science.1101485

Rohe, M., Schründer, J., Tudzynski, P., and Meinhardt, F. (1992). Phylogenetic relationships of linear, protein-primed replicating genomes. Curr. Genet. 21, 173–176. doi: 10.1007/BF00318478

Root-Bernstein, M., and Root-Bernstein, R. (2015). The ribosome as a missing link in the evolution of life. J. Theor. Biol. 367, 130–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.11.025

Root-Bernstein, R., and Root-Bernstein, M. (2016). The ribosome as a missing link in prebiotic evolution II: ribosomes encode ribosomal proteins that bind to common regions of their own mRNAs and rRNAs. J. Theor. Biol. 397, 115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2016.02.030

Ruiz-Mirazo, K., Briones, C., and de la Escosura, A. (2014). Prebiotic systems chemistry: new perspectives for origins of life. Chem. Rev. 114, 285–366. doi: 10.1021/cr2004844

Schroeder, R., Grossberger, R., Pichler, A., and Waldsich, C. (2002). RNA folding in vivo. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12, 296–300. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(02)00325-1

Seligmann, H. (2013). Polymerization of non-complementary RNA: systematic symmetric nucleotide exchanges mainly involving uracil produce mitochondrial RNA transcripts coding for cryptic overlapping genes. Biosystems 111, 156–174. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2013.01.011

Seligmann, H. (2014). Putative anticodons in mitochondrial tRNA sidearm loops: pocketknife tRNAs? J. Theor. Biol. 340, 155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2013.08.030

Seligmann, H. (2017). Natural mitochondrial proteolysis confirms transcription systematically exchanging/deleting nucleotides, peptides coded by expanded codons. J. Theor. Biol. 414, 76–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2016.11.021

Seligmann, H., and Labra, A. (2014). The relation between hairpin formation by mitochondrial WANCY tRNAs and the occurrence of the light strand replication origin in Lepidosauria. Gene 542, 248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.02.021

Seligmann, H., and Raoult, R. (2016). Unifying view of stem–loop hairpin RNA as origin of current and ancient parasitic and non-parasitic RNAs, including in giant viruses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 31, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.11.004

Seligmann, H., and Warthi, G. (2017). Genetic code optimization for cotranslational protein folding: codon directional asymmetry correlates with antiparallel betasheets, tRNA synthetase classes. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 15, 412–424. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2017.08.001

Stedman, K. (2013). Mechanisms for RNA capture by ssDNA viruses: grand theft RNA. J. Mol. Evol. 76, 359–364. doi: 10.1007/s00239-013-9569-9

Sun, C., Feschotte, C., Wu, Z., and Mueller, R. L. (2015). DNA transposons have colonized the genome of the giant virus Pandoravirus salinus. BMC Biol. 15:38. doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0145-1

Symons, R. H. (1981). Avocado sunblotch viroid: primary sequence and proposed secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 9, 6527–6537. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.23.6527

Szostak, J. W. (2009). Origins of life: systems chemistry on Earth. Nature 459, 171–172. doi: 10.1038/459171a

Villarreal, L. P. (2015). Force for ancient and recent life: viral and stem-loop RNA consortia promote life. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1341, 25–34. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12565

Villarreal, L. P. (2016). Persistent virus and addiction modules: an engine of symbiosis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 31, 70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.03.005

Widmann, J., Di Giulio, M., Yarus, M., and Knight, R. (2005). tRNA creation by hairpin duplication. J. Mol. Evol. 61, 524–530. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0315-1

Xie, A., and Scully, R. (2017). Hijacking the DNA damage response to enhance viral replication: γ-herpesevirus 68 orf36 phosphorylates histone H2AX. Mol. Cell 27, 178–179. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.005

Yutin, N., Raoult, D., and Koonin, E. V. (2013). Virophages, polintons, and transpovirons: a complex evolutionary network of diverse selfish genetic elements with different reproduction strategies. Virol. J. 10, 158. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-10-158

Zhao, P., Zhang, W.-B., and Chen, S.-J. (2010). Predicting secondary structural folding kinetics for nucleic ccids. Biophys. J. 98, 1617–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4319

Keywords: systematic nucleotide exchange, swinger DNA polymerization, invertase, 3′-to-5′ polymerization, transcription, Acanthamoeba castellanii

Citation: Seligmann H and Raoult D (2018) Stem-Loop RNA Hairpins in Giant Viruses: Invading rRNA-Like Repeats and a Template Free RNA. Front. Microbiol. 9:101. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00101

Received: 18 August 2017; Accepted: 16 January 2018;

Published: 01 February 2018.

Edited by:

Guenther Witzany, Independent Researcher, Salzburg, AustriaReviewed by:

Cristina Romero-López, Institute of Parasitology and Biomedicine “López-Neyra” (CSIC), SpainCopyright © 2018 Seligmann and Raoult. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hervé Seligmann, cG9kYXJjaXNzaWN1bGFAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.