- 1Paul G. Allen School for Global Animal Health, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, United States

- 2Institute of Marine Biology, College of Oceanography, Hohai University, Nanjing, China

- 3Department of Food Science and Technology, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, United States

The Escherichia coli quorum sensing (QS) signal molecule, autoinducer-2 (AI-2), reaches its maximum concentration during mid-to-late growth phase after which it quickly degrades during stationary phase. This pattern of AI-2 concentration coincides with the up- then down-regulation of a recently described microcin PDI (mccPDI) effector protein (McpM). To determine if there is a functional relationship between these systems, a prototypical mccPDI-expressing strain of E. coli 25 was used to generate ΔluxS, ΔlsrACDBFG (Δlsr), and ΔlsrR mutant strains that are deficient in AI-2 production, transportation, and AI-2 transport regulation, respectively. Trans-complementation, RT-qPCR, and western blot assays were used to detect changes of microcin expression and synthesis under co-culture and monoculture conditions. Compared to the wild-type strain, the AI-2-deficient strain (ΔluxS) and -uptake negative strain (Δlsr) were >1,000-fold less inhibitory to susceptible bacteria (P < 0.05). With in trans complementation of luxS, the AI-2 deficient mutant reduced the susceptible E. coli population by 4-log, which was within 1-log of the wild-type phenotype. RT-qPCR and western blot results for the AI-2 deficient E. coli 25 showed a 5-fold reduction in mcpM transcription with an average 2-h delay in McpM synthesis. Furthermore, overexpression of sRNA micC and micF (both involved in porin protein regulation) was correlated with mcpM regulation, consistent with a possible link between QS and mcpM regulation. This is the direct first evidence that microcin regulation can be linked to quorum sensing in a Gram-negative bacterium.

Introduction

Bacteria can regulate specific cellular functions through quorum sensing (QS), which is a density-dependent, cell-to-cell communication system (Papenfort and Bassler, 2016). In response to changes in cell density, QS allows bacteria to alter behavior and regulate global gene expression collectively through the accumulation of threshold concentrations of small, diffusible autoinducer (AI) signal molecules (Papenfort and Bassler, 2016). Both Gram-negative and -positive bacterial species can produce QS signaling molecules such as autoinducer-2 (AI-2), which in some bacterial species can affect inter- and intra-specific behavior (Sun et al., 2004; Federle, 2009; Xue et al., 2009). For example, AI-2 contributes to gene regulation for E. coli O157:H7 including regulation of virulence gene expression (Sperandio et al., 2002), type III secretion (Sperandio et al., 1999), flagellar synthesis, motility, and chemotaxis (Sperandio et al., 2001). Moreover, at high cell density, E. coli AI-2 can bind to cellular receptors that subsequently regulate protein production and biofilm formation (DeLisa et al., 2001). During the mid-to-late exponential growth phase, AI-2 reaches its maximum concentration followed by degradation during the stationary phase (Surette and Bassler, 1998; Ren et al., 2004). This temporal pattern of AI-2 concentration coincides with the up- and down-regulation of the recently described microcin PDI (mccPDI) in E. coli (Eberhart et al., 2012).

MccPDI was first described from a cattle E. coli isolate 25 (E. coli 25) and it inhibits a diversity of E. coli strains including enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) serotypes O157:H7 and O26 (Eberhart et al., 2012, 2014; Zhao et al., 2015). The inhibitory phenotype was characterized as “proximity-dependent inhibition” (PDI) due to the apparent need for the producing strain to be in close proximity to inhibit susceptible cells (Sawant et al., 2011; Eberhart et al., 2012). Zhao et al. (2017) previously showed that in the presence of low osmolarity conditions, synthesis of the mccPDI effector protein (McpM) is upregulated via a two-component regulatory system, EnvZ/OmpR (Zhao et al., 2017). Maximal inhibition from PDI occurs during the mid-to-late exponential growth phase, but declines rapidly during stationary phase despite continuing low-osmolarity conditions in the growth media. The fact that temporal expression of microcin PDI coincides with the maximum concentration of AI-2 at mid-to-late-exponential growth phase and degradation of AI-2 in stationary phase suggests the possibility that AI-2 QS plays a role in the PDI regulation. Consequently, we hypothesized that bacteria's ability to detect cell-to-cell density through AI-2 QS contributes to regulation of the mccPDI phenotype. Through a series of gene knockout and complementation experiments, we found that a PDI-positive strain that was deficient in the QS system was also defective for inhibition of susceptible bacteria (E. coli K-12 BW25113), mcpM transcription, and delayed McpM synthesis in comparison to the wild-type strain. These findings highlight the complexity of microcin PDI regulation and contribute to the understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of Class IIa microcins in E. coli.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

Unless otherwise stated, the E. coli strains used in this study (Table 1) were grown in LB -Lennox (LB broth) medium (Difco) or in M9 minimal defined medium (Na2HPO4 6 g/L, KH2PO4 3 g/L, NaCl 0.5 g/L, NH4Cl 1 g/L, MgSO4 1 mM, CaCl2 0.1 mM, and 0.2% glucose) supplemented with thiamine (1 mg/L) and leucine (100 μg/mL; Eberhart et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2015, 2017) at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm. Antibiotics were added to media as needed (ampicillin, Amp, 100 μg/mL; tetracycline, Tet, 50 μg/mL; kanamycin, Kan, 50 μg/mL; nalidixic acid, Nal, 30 μg/mL; chloramphenicol, Cm, 32 μg/mL). Vibrio harveyi MM32 (ATCC BAA-1121) (Table 1) was grown in marine broth 2216 (Difco) or autoinducer bioassay (AB) medium [NaCl 17.5 g/L, MgSO4 12.3 g/L, casamino acids (vitamin-free) 2.0 g/L, KH2PO4 (pH 7.0) 1 M, L-arginine 0.1 M, and glycerol 10 mL/L; (ATCC)] at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm and antibiotics were added as needed (Amp, 50 μg/mL; Kan, 25 μg/mL; Cm, 15 μg/mL).

Plasmid Extraction and Vector Construction

All plasmids were extracted from E. coli by using a QIAprep Spin Miniprep kit (Qiagen). E. coli genomic DNA was extracted with the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen). Platinum PCR Super Mix (Invitrogen) was used for preparative PCR when working with plasmid pBAD18-Cm, pDM4, pGEM-2, and pKD4. Complementation were performed using primers incorporating restriction sites (Supplemental Table 1) for PCR amplification, restriction digest (New England Biolabs Inc.), and ligation (T4 ligase, New England Biolabs Inc.) following standard cloning techniques. All conventional PCR for verification of constructs and gene detection used DreamTag Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific) and PCR products were confirmed by sequencing (Eurofins Genomics).

Mutant Construction

Gene-specific PCR-mediated gene deletion followed the methods of Datsenko and Wanner (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000). Briefly, primers (Supplemental Table 1) were designed to incorporate a 36- to 50-nucleotide segment that was complementary to the DNA sequence flanking the gene of interest. Primers were used to generate a PCR product that joined these flanking sequences to a Kan-resistance gene (kanr) that originated from pKD4 (Table 1). PCR products were column purified by using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Restriction enzyme (DpnI; New England Biolabs Inc.) was used to digest pKD4 plasmid for 4 h at 37°C before column purification was repeated. Processed PCR products (150 ng) were then suspended in 5 μL of 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and were electroporated into E. coli 25 with a Gene Pulser Xcell (Bio-Rad) as described previously (Zhao et al., 2015). Briefly, E. coli 25 carrying the λ Red plasmid pKD46 (Ampr) was prepared for electroportation (1.8 kV, 25 μF, 200 Ω, 1 mm gap cuvette) by first growing culture to an optical density (OD600nm) of ~0.6 in SOB medium (Fisher Scientific) (Table 1) with 1 mM L-arabinose (30°C). Cells were then washed twice in ice-cold water and once in 10% glycerol. Cells were subsequently resuspended in 10% glycerol (50 μL) for electroporation. Immediately after electroporation, cells were resuspended in SOC recovery medium (Fisher Scientific) for 2 h at 30°C (200 rpm) before plating on Kan-containing LB agar and incubating overnight at 30°C. PCR was used to verify gene deletion of lsr, lsrK, and lsrR (Table S1). All mutants were generated utilizing this method with the exception of E. coli 25 ΔluxS, for which a splice-overlap-extension method was used (Heckman and Pease, 2007). Briefly, two 400- to 600-bp PCR fragments from sequences flanking luxS were joined and then cloned into a suicide plasmid (pDM4; Cmr; Table 1) by using standard cloning procedures (Milton et al., 1996). Constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Eurofins Genomics) prior to electroporating into electrocompetent E. coli S17-1 λpir (Table 1). Conjugation was performed with E. coli 25 to generate a mutant that was selected on LB agar plates (Tet and Cm antibiotics) followed by a 10% sucrose selection (Zhao et al., 2015). PCR was used to confirm the deletion of luxS.

RNA Extraction and Quantitative RT-PCR (RT-PCR)

Cultures (5 mL) were grown overnight in M9 medium and total RNA was extracted from an aliquot (1.5 mL) with the RiboPureTM-Bacteria kit (Ambion) per manufacturer's instruction with an additional DNase treatment with a RQ-1 RNase-Free DNase (Promega). RNA was quantified by using a NanoDropTM 2000 spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). Complementary DNA was generated from DNase-treated total RNA (500 ng) with iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad) per manufacturer's instruction. Quantitative RT-PCR was completed in triplicate using the SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) per manufacturer's instruction with indicated primers (Supplemental Table 1). A CFX98 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) was used to perform the thermal cycling parameters: one cycle at 95°C for 30 s; 39 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 55°C for 15 s with plate read and 72°C for 30 s; 65°C for 5 s and plate read every 0.5°C/cycle to 95°C. The relative gene expression level was calculated with wild-type E. coli 25 serving as the control for calculations using the ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). To detect potential DNA contamination, before the reverse transcription reaction an aliquot of each RNA extraction was subjected to conventional qPCR with rpoD primers (Cq-values >37, signified low level of DNA contamination).

Co-culture Competition Assays

Co-culture competition assays were performed with a modified competition assay protocol (Chen et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2015). Briefly, strains to be competed were grown individually in LB broth overnight. The next day the individual overnight cultures were combined (1:1) and inoculated into fresh M9 medium at a ratio of 1:100 for competition for 4, 8, 12, and 24 h at 37°C with aeration. Individual strains were also inoculated (monoculture) under the same conditions as controls. When appropriate, antibiotics and/or 0.2% (w/v) L-arabinose was added to pBAD18-Cm constructs or 0.5 mM Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to pGEM-2 constructs unless otherwise noted. Colony forming unit (CFU) were quantified by using serial dilution and a 6X6 drop-plate technique (Chen et al., 2003).

Autoinducer Bioassay

Measurement of AI-2 production by E. coli 25 and complemented luxS strains was done by using an autoinducer bioassay (AB) as previously described (Surette and Bassler, 1998, 1999). Strains of interest were grown overnight at 30°C with aeration in LB medium supplemented with 0.5% glucose. V. harveyi MM32 was grown overnight at 30°C with aeration in AB medium supplemented with 0.5% glucose. On the following day, bacterial cultures were inoculated (1:100) into fresh media (as described, respectively) and were grown for 8 h at 30°C with aeration. E. coli 25 ΔluxS/pBAD18-Cm and E. coli 25 ΔluxS/pBAD18-Cm::luxS were grown in LB without glucose to avoid araC inhibition during L-arabinose induction of pBAD18-Cm::luxS (Simcikova et al., 2014). Samples were centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 10 min and filtered (0.22 μm) to obtain cell-free supernatants that were stored at −20°C. The autoinducer bioassay (AB) medium (Bassler et al., 1993) was used to grow reporter strain V. harveyi MM32 (autoinducer 1−, autoinducer 2−; Bassler et al., 1993). Previously prepared cell-free supernatants were tested for the presence of AI-2 by adding to V. harveyi culture followed by detection of luminesce. Briefly, reporter strain V. harveyi MM32 was grown overnight in AB medium (30°C for 16 h) and was then diluted (1:5,000) in fresh AB medium. An aliquot (90 μL) was added to each well of a 96-well plate with 10 μL supernatant sample (from above). A positive-control well contained cell-free supernatant from E. coli 25 wild-type, while a negative-control well contained V. harveyi MM32 with no supernatant added. Plates were sealed with breathable sealing film (Axygen) and luminescence was measured every hour using an Infiniti M1000 PRO microplate reader (Tecan Systems). Each assay was repeated for three independent replicates.

Protein Analysis

Isolated colonies were inoculated into 5-mL LB media with appropriate antibiotic and grown as described. Overnight culture was diluted (1:100) into fresh M9 media (10 mL) and grown overnight at 37°C with 200 rpm shaking until OD600 ~ 0.6 at which point 0.02% (w/v) L-arabinose was added for 24 h at room temperature with shaking at 200 rpm. Total proteins were collected by centrifugation at 18,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1x laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) and boiled for 10 min. Any kD Tris-glycine precast gels (Bio-Rad) were used for SDS-PAGE protein separation. A Trans-Blot turbo transfer starter system (Bio-Rad) was used to transfer proteins onto a low-fluorescence polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Bio-Rad) and Ponceau S stain was used to verify protein transfer prior to addition of antibodies for specific protein detection. Primary antibody anti-His-tag (1:1,000; Thermo Scientific) was used with secondary goat anti-mouse antibody (1:5,000; DyLight 650, conjugate). A ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad) was used to detect fluorescent signal and band intensity was quantified with ImageJ software (Schneider et al., 2012). A ratio of McpM value to DnaK value served to normalize and quantify and are represented by arbitrary unit (AU).

Statistical Analysis

Where appropriate, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare experimental results with a Dunnett's one-way multiple pairwise comparison test. Depending on the experimental design, a two-way ANOVA was used in conjunction with a Tukey's all pairwise multiple comparison test (SigmaPlot version 12.5; Systat Software, Inc., San Jose, CA).

Results

Deleting luxS Attenuates the mccPDI Phenotype

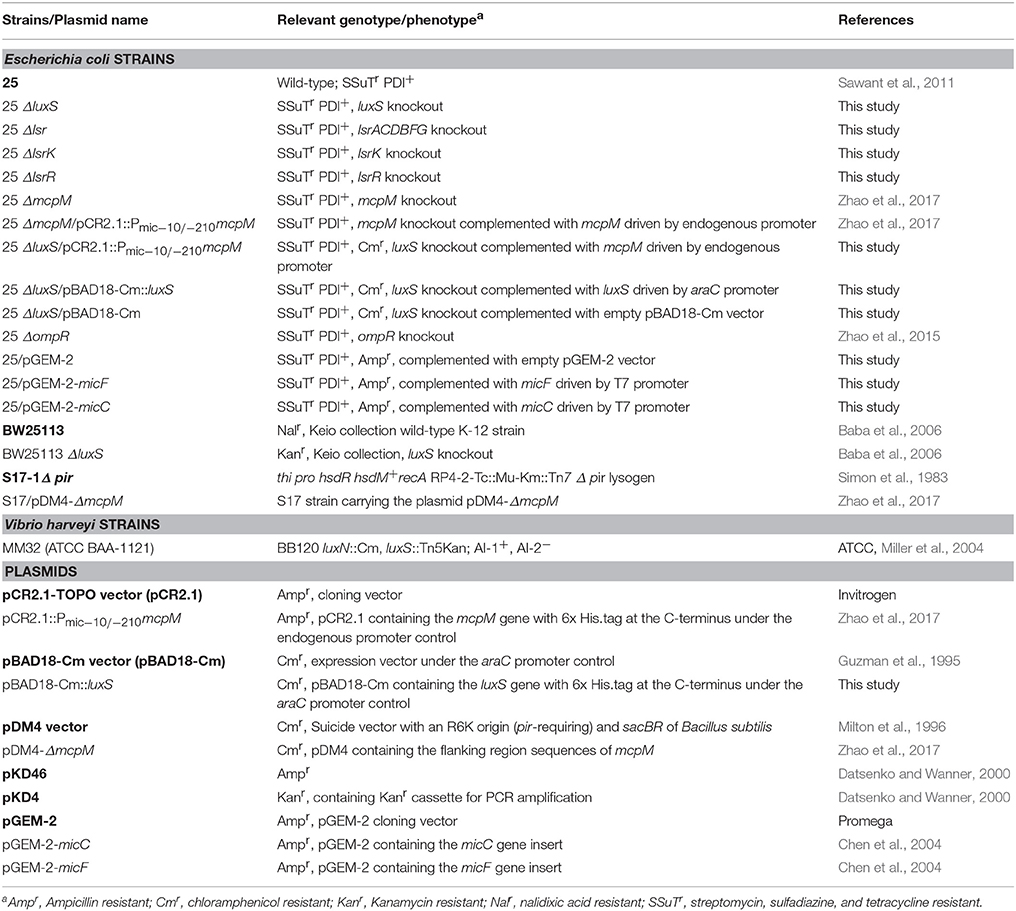

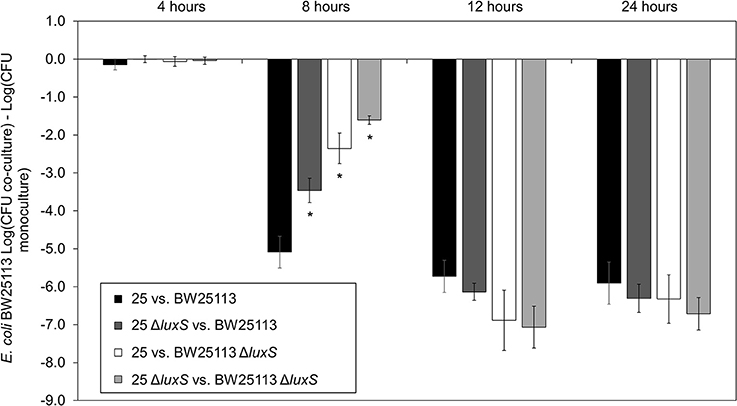

We conducted co-culture competition assays with luxS deletion strains for both the microcin-PDI positive (E. coli 25) and susceptible strains (E. coli K-12 BW25113; Figure 1). Differences in inhibition were clearly evident for the mid-to-late log growth phase (8 h), which is the same time that there was a 14-fold increase in the abundance of mcpM mRNA relative to the 4-h culture of wild-type E. coli 25 (Figure S1; Eberhart et al., 2012). Compared to inhibition of BW25113 by the wild-type positive control (at 8 h, Figure 1), eliminating luxS from E. coli 25 was 1.6-log less effective while eliminating luxS from BW25113 reduced the mccPDI phenotype by 2.7-log. When co-culture involved both luxS deletion strains, the total reduction in mccPDI phenotype was ~3.5 log relative to the wild-type strain; a finding that was consistent with AI-2 from both strains contributing to a signal for upregulation of mccPDI. After 8 h the effect of luxS deletion was no longer observed (Figure 1). As expected, co-culture with the susceptible E. coli BW25113 had no negative effects on E. coli 25 growth with or without a luxS (Figure S2).

Figure 1. Delayed mccPDI inhibition when luxS is deleted. Competition assays between mccPDI-positive E. coli strain (25 or 25 ΔluxS) and target E. coli strain (BW25113 or BW25113 ΔluxS) in M9 media for 4, 8, 12, and 24 h. Results are expressed as the difference of mean log CFU during co-culture and mono-culture of the target strain (n = 3 independent replicates; error bar = SEM). *P < 0.05 compared to wild-type co-culture (black bars) based on two-way ANOVA.

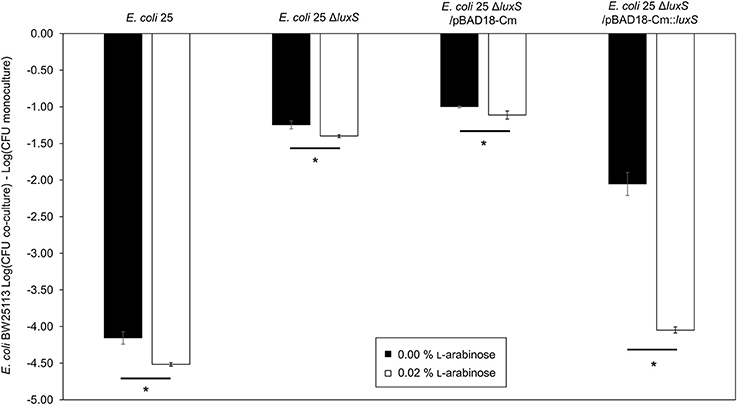

AI-2 deficient mutant strain E. coli 25 ΔluxS was complemented by using in trans expression of luxS under the control of an L-arabinose inducible promoter, araBAD (pBAD18-Cm). A pBAD18-Cm plasmid with no cloned insert was used as a negative control while E. coli 25 was used as positive control. Complementation restored the ability of luxS deletion strain to inhibit BW25113 compared to the respective un-induced strain (Figure 2, compare first and last bars under E. coli 25 ΔluxS/pBAD18-Cm::luxS). Adding arabinose to the culture regardless of the presence or absence of the pBAD18-Cm plasmid produced some growth advantage for the E. coli 25 strains relative to the susceptible strain (Figure 2, compare the open and filled bars), although this effect did not exceed 0.5 log on average. A western blot confirmed synthesis of the complemented LuxS protein (8 h culture; Figure S3A), and an autoinducer bioassay was consistent with increased production of AI-2 (Figure S3B).

Figure 2. Complementation restores of luxS mccPDI phenotype. CFU counts for E. coli BW25113 following competition with microcin-PDI producer E. coli 25, E. coli 25 ΔluxS, E. coli 25 ΔluxS/pBAD18-Cm, and E. coli 25 ΔluxS/pBAD18-Cm::luxS. Non-induced (black bar) and induced with 0.02% L-arabinose (white bar). Results are expressed as the difference in CFU counts of BW25113 grown in co-culture and monoculture (n = 3 independent replicates; error bar = SEM). *P < 0.05 compared to wild-type co-culture based on one-way ANOVA.

Deletion of the AI-2 Transporter Decreases Inhibition of mccPDI-Susceptible Bacteria

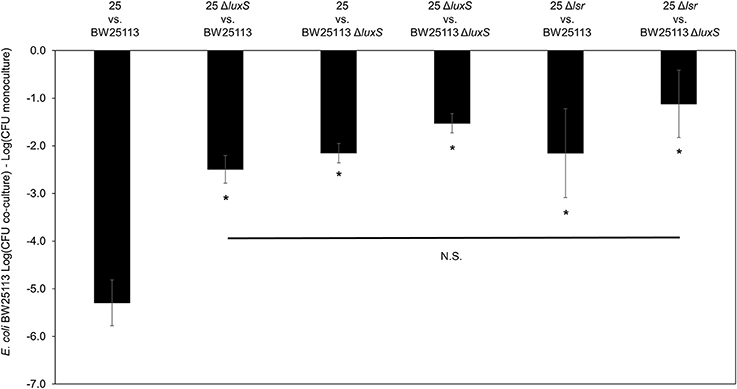

To further validate the contribution of AI-2 to the regulation of the mccPDI phenotype, we constructed an E. coli 25 ΔlsrACDBFG (E. coli Δlsr) mutant (Wang et al., 2005). The lsr operon consists of six genes of which lsrACDB encodes the ABC transporter, and lsrF and lsrG are involved in the degradation of AI-2. A separate lsrR/K operon encodes an uptake repressor and kinase to phosphorylate AI-2, respectively (Li et al., 2007). After 8 h the reduction in inhibition for the Δlsr strain was statistically indistinguishable from the reduction for the ΔluxS strain (Figure 3). We further confirmed that deletion of the lsr operon or the lsrR/K operon does not affect production of AI-2 itself (Figure S4).

Figure 3. Deletion of AI-2 ABC cassette, lsrACDBFG limits the mccPDI phenotype. Competition assay between isogenic mccPDI-producing E. coli strains (25, 25 ΔluxS, and 25 Δlsr) and target E. coli strains (BW25113 or BW25113 ΔluxS) in M9 media for 8 h. Results are expressed as the difference of mean log CFU during co-culture and mono-culture (n = 3 independent replicates; error bar = SEM). *P < 0.05 compared to wild-type co-culture based on one-way ANOVA.

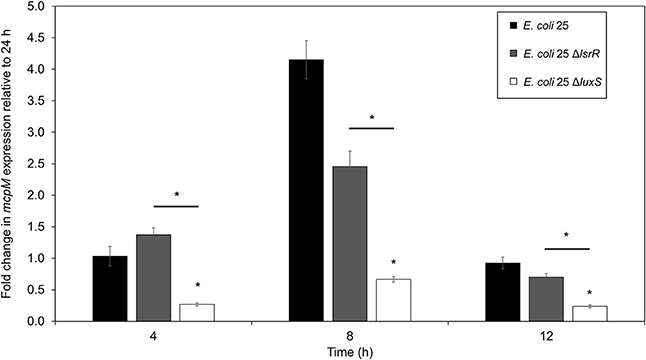

RT-qPCR Confirms Down Regulation of mcpM in E. coli 25 ΔluxS

The mRNA for mcpM peaks at the mid-to-late log phase growth and declines when cultures enter stationary phase (Figure S1). Under monoculture (1:500 initial dilution) mcpM expression differed at 8 h was reduced for ΔluxS strains compared to the isogenic wild-type (Figure 4). To verify ΔluxS monoculture results, we repeated the experiment from co-culture samples with reduced inoculant (1:1,000 instead of 1:500 to normalize with co-culture experiments) and observed a similar mcpM expression pattern, but at later point of 12 h (Figure S5). The pattern of up and down-regulation of mcpM expression matches what has been reported previously (Eberhart et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2017). The AI-2 deficient mutant (ΔluxS) clearly exhibits reduction of mcpM (Figure 4 and Figure S5) with an overall 5-fold reduction in mcpM transcription, consistent with phenotype differences (Figure 1). Furthermore, the strain deficient in AI-2 (ΔluxS) has a greater reduction of mcpM expression compared to ΔlsrR (Figure 4). This suggests that the deletion of the AI-2 uptake regulation gene (ΔlsrR) or uptake mechanism Δlsr (Figure 3) can be mitigated through another means of cell entry such as passive diffusion of AI-2 through porins (Galloway et al., 2011).

Figure 4. Transcription of mcpM is significantly down regulated in AI-2 QS deficient E. coli 25 strains. Transcriptional analysis of the mccPDI effector mcpM for E. coli 25 ΔluxS, E. coli 25 ΔlsrR mutant and isogenic wild-type strain in M9 media over time by qPCR. Fold change is expressed relative to mcpM expression in M9 at 24 h (error bars = SEM; three independent replicates). *P < 0.05 based on two-way ANOVA.

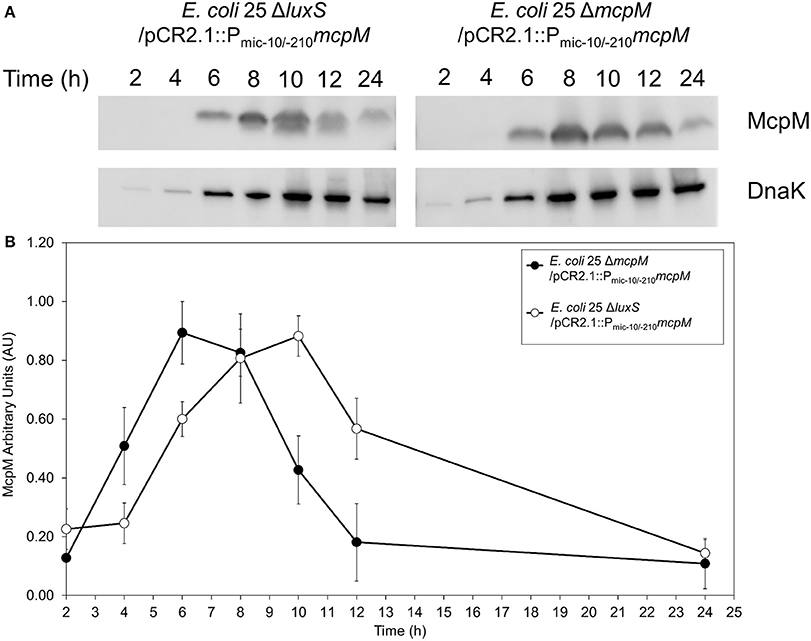

luxS Deletion Delays Synthesis of Recombinant McpM

To examine the kinetics of McpM protein synthesis, we used a vector (pCR2.1) with the mcpM endogenous promotor (Pmic−10/−210) coupled with mcpM (Zhao et al., 2017). Normalized densitometry of western blot results showed a delay in E. coli 25 ΔluxS/pCR2.1::Pmic−10/−210mcpM recombinant McpM production compared to the strain E. coli 25 ΔmcpM/pCR2.1::Pmic−10/−210mcpM that retained an intact luxS (Figure 5). The kinetics of McpM synthesis for both strains mirrored the typical mcpM transcription except with a 2-h delay for the ΔluxS strain (Figure 5B). The lack of luxS does not inhibit the production of McpM because EnvZ/OmpR is still the primary regulator of mcpM (Zhao et al., 2017) as confirmed by loss of McpM synthesis with the deletion of the ompR (Figure S6A). Deletion of luxS also does not affect ompR expression, which remains constant through different growth phases (Figure S6B).

Figure 5. E. coli 25 ΔluxS mutant causes delay in McpM production. (A) Western blot of McpM. Whole-cell lysate samples from E. coli 25 ΔmcpM/pCR2.1::Pmic−10/−210mcpM and E. coli 25 ΔluxS/pCR2.1::Pmic−10/−210mcpM complemented strains were collected for every 2 h from 2 to 12 h, and 24 h. Endogenous DnaK served as a loading control. (B) Western blot densitometry analysis of McpM. Whole-cell lysate samples from E. coli 25 ΔmcpM/pCR2.1::Pmic−10/−210mcpM (black circle) and E. coli 25 ΔluxS/pCR2.1::Pmic−10/−210mcpM (white circle) complemented strains were collected for every 2 h from 2 to 12 h, and 24 h. Endogenous DnaK served as a loading control. Normalization of the McpM against DnaK are represented by arbitrary unit (AU) over 24 h. Error bars = SEM; three independent experiments.

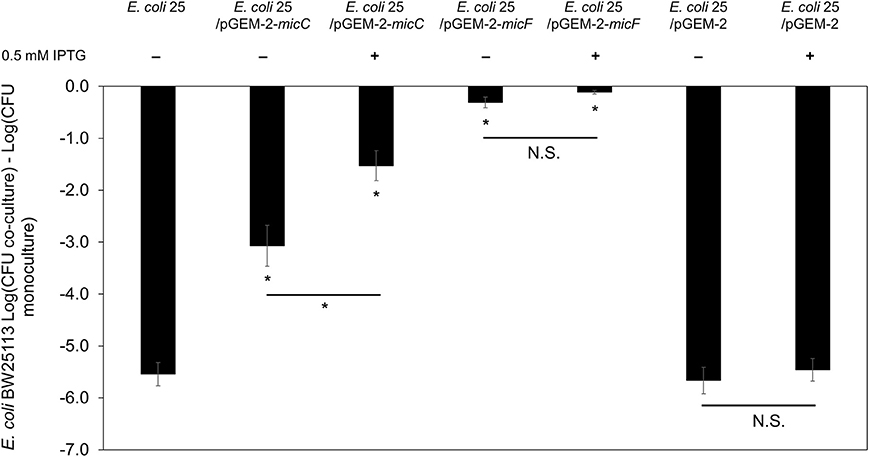

Overexpression of sRNA micC and micF Limits mccPDI

Published work demonstrates that AI-2 QS and LsrR influence the synthesis of the sRNA micC (Li et al., 2007), which in turn regulates outer membrane porins (OmpC and OmpF) in a manner similar to the EnvZ/OmpR two-component system (Mizuno et al., 1988). To examine the effects of micC and micF (another sRNA known to regulate outer membrane porin OmpF in E. coli; Delihas and Forst, 2001) in PDI-producer strain, we overexpressed micC and micF in E. coli 25 during competition with strain BW25113. After 8-h co-culture competition it was readily apparent that overexpression of micC and micF reduced the PDI phenotype significantly (Figure 6). Compared to positive control competition culture (with empty vector pGEM-2; 5-log loss in susceptible BW25113), micC overexpression resulted in a 1-log reduction in BW25113 while micF overexpression resulted in a complete loss of the PDI phenotype. There was evidence that a “leaky” pGEM-2 vector permitted sufficient micF and micC expression to reduce the PDI phenotype by 5-log and 2-log, respectively, in the absence of IPTG induction (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Overexpression of sRNA micC and micF in PDI-producer strain. The co-culture competition assay of over expression micC and micF in wild-type E. coli 25 (E. coli 25/pGEM-2-micC, E. coli 25/pGEM-2-micF, E. coli 25/pGEM-2) induced with 0.5 mM IPTG against target E. coli BW25113 in M9 media for 8 h. Results are expressed as the difference of mean log CFU during co-culture and mono-culture (n = 3 independent replicates; error bar = SEM). *P < 0.05 based on one-way ANOVA.

Discussion

The involvement of QS in the regulation of mccPDI was suspected. Eberhart et al. first demonstrated that the expression of the mccPDI effector gene (mcpM) increases rapidly during the late-log growth phase and declines rapidly as a culture enters the stationary phase (Eberhart et al., 2012). Zhao et al. demonstrated that without the EnvZ/OmpR two-component regulatory system, mcpM expression would not be upregulated (Zhao et al., 2017). The EnvZ/OmpR system functions by sensing the osmolarity of the broth culture (low salt favors upregulation; Zhao et al., 2017). Importantly, even when salt concentration is low the expression of mcpM is delayed until late log-growth, after which the expression of mcpM is downregulated despite a constant salt concentration (although pH also changes; unpublished results; Eberhart et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2017). This project concerns the mechanism by which mcpM expression is upregulated in the presence of permissible osmotic conditions (low salt) during late log-phase growth.

Microcin production by Gram-negative bacteria is typically triggered by environmental and nutritional factors (Duquesne et al., 2007). Examples include microcin B17, C, E492, and J25 that are regulated by a global regulator (e.g., OmpR and sigma factors), or in response to depletion of nutrient, carbon, and or nitrogen source (de Lorenzo, 1985; Moreno et al., 2002; Socias et al., 2009). Unlike bacteriocins from lactic-acid producing bacteria and for which quorum sensing (QS) is known to play a regulatory role (Drider et al., 2006), to date there have been no reports about the contribution of QS to the regulation of Class I, IIa, or IIb microcin expression. There is some evidence that QS is at least indirectly involved with regulation of other Gram-negative microcins. Piskunova et al. (2017) recently reported that (p)ppGpp can mediate production of microcin C in E. coli, presumably as part of the stringent response pathway that is known to interact with quorum sensing (Oh and Cho, 2014). In the case of mccPDI, however, the pattern of upregulation under favorable osmotic conditions reflects what would be expected if regulation was influenced by QS.

Without QS, Upregulation of mcpM Is Compromised

From a broad perspective, QS-regulated bacteriocin production should provide a competitive advantage when resources become limited in the presence of large population of competitors (Blanchard et al., 2016). The PDI-positive strain (E. coli 25) used in this study was originally isolated from a cow (Sawant et al., 2011), and by using a neonatal calf model Eberhart et al. showed that the wild-type E. coli 25 out competed an isogenic PDI-defective strain (E. coli 25 ΔmcpM ΔmcpI; Eberhart et al., 2014). The “growth phase” of bacteria in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is likely variable depending on conditions at any given time, but the size of the bacterial population (E. coli >106/g feces in cattle) is likely to be within a range that is conducive to QS (Maki and Picard, 1965; Alberghini et al., 2009).

LuxS is necessary for AI-2 synthesis and E. coli uses AI-2 for interspecies communication and global gene regulation (Sperandio et al., 2001). E. coli can also sense AI-1, AI-3, epinephrine/norepinephrine and other QS molecules (Sperandio et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2004; Walters and Sperandio, 2006; Walters et al., 2006; Connolly et al., 2015; Moreira and Sperandio, 2016) even though it does not produce these signal molecules with exception of AI-3-producing EHEC (Michael et al., 2001; Dyszel et al., 2010; Soares and Ahmer, 2011; Sabag-Daigle et al., 2012). Loss of mcpM regulation with deletion of luxS (Figure 5) and the combined effect of AI-2 when both E. coli 25 and BW25113 are co-cultured (Figure 1) are consistent with AI-2 influencing McpM synthesis. It is presumed that the lower GI tract of a cattle experiences relatively low osmolarity (Brouwer and Van Weerden, 1956) that is conducive to EnvZ/OmpR-mediated upregulation of mcpM. In this environment, AI-2 concentration likely provides “fine-tuned” control of expression so that even with permissive osmolarity, McpM is only synthesized when high-density bacterial populations experience conditions conducive to further population growth (e.g., after the host animal ingests a meal).

Small RNA May Play a Role in mcpM Regulation through AI-2 Quorum Sensing

It is unclear how the concentration of AI-2 regulates mcpM expression. We know that decreased AI-2 concentration increases ompC expression and represses ompF expression during stationary-phase growth (Ren et al., 2004). OmpF is an outer membrane that must be present on susceptible cells before McpM is able to inhibit these cells (Zhao et al., 2015), and as a consequence Zhao et al. speculated that mcpM expression should mirror ompF expression (Zhao et al., 2017). For E. coli LsrR serves as an autoregulatory repressor protein that also regulates lsrACDB (AI-2 ATP-binding cassette transporter; Xue et al., 2009). Furthermore, when AI-2 is phosphorylated by LsrK, it subsequently binds to LsrR to regulate other genes associated to biofilm, membrane porins, and sRNA production (Li et al., 2007; Xue et al., 2009). A functional lsr AI-2 transport system is AI-2 (luxS) dependent (Taga et al., 2001).

Deletion of lsrR is associated with the up-regulation of sRNA micC through AI-2 signaling (Li et al., 2007). sRNAs micC and micF bind the mRNA of ompC and ompF to form MicC-ompC and MicF-ompF complexes that prevent translation of these mRNAs (Schmidt et al., 1995; Chen et al., 2004; Vogel and Papenfort, 2006). In M9 defined medium, conditions favoring OmpF expression in E. coli also favor the synthesis of McpM in E. coli 25 at late-log growth phase (Zhao et al., 2017). We speculate that during exponential growth phase, both micF and micC expression are kept at a base level similar to ompR expression (Figure S6B). When the PDI-producer strain reaches stationary growth phase, micF and micC are up-regulated to reduce synthesis of OmpF and OmpC. We surmise that the sRNA micF and micC also interact and regulate synthesis of McpM. IntaRNA prediction of pmic−500/0mcpM (mcpM−500 to 0 bp promotor region) sequence against micC and micF suggests a potential interaction between mcpM mRNA (189–241 nt) and micC (7–66 nt); mcpM (290–345 nt) and micF (1–64 nt; Wright et al., 2014). As a result, sRNA micC and micF could potentially mediate the translation of McpM as suggested in our overexpression experiment (Figure 6), and this would provide a mechanism for down-regulating mcpM as the population enters a stationary growth phase.

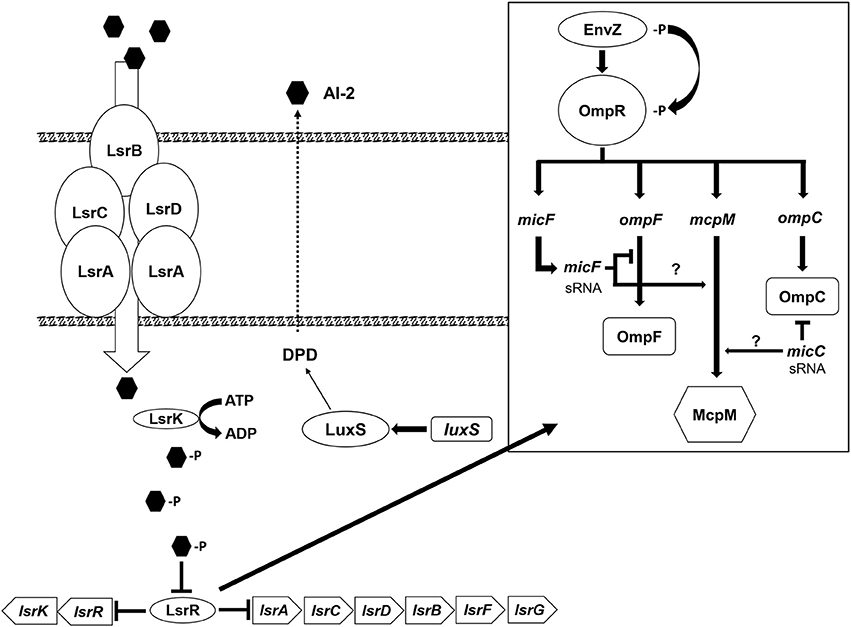

Proposed Model for McpM Regulation

Disruption of the QS AI-2 synthesis and uptake system in the microcin-PDI producer strain (E. coli 25) does not result in complete repression of McpM. Presumably, this is because OmpR interacts directly with the mcpM promoter as reported earlier (Figure S6A; Zhao et al., 2017). Herein we propose a McpM regulation mechanism model that incorporates both the EnvZ/OmpR two-component regulatory system and QS AI-2 (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Microcin-PDI regulation model. The proposed regulatory mechanism of mcpM through the AI-2 uptake pathway (modified from Li et al., 2007). The AI-2 molecule produced by LuxS is actively transported into the cell by LsrACBD where it is phosphorylated by LsrK. The phosphorylated AI-2 interacts with LsrR and the signal is transduced via LsrR through (1) an unknown mechanism (?) that influences the two component system, EnvZ/OmpR (modified from Delihas and Forst, 2001; Blain et al., 2010) and induces expression of sRNA micC and/or micF that subsequently bind mcpM mRNA to inhibit translation, or (2) via an alternative pathway (?) that regulates transcription of micF and/or micC.

The AI-2 molecule is derived from 4, 5-dihydroxy-2,3-pentadione (DPD), which is catalytically transformed by the LuxS from S-ribosylhomocysteine (Schauder et al., 2001). As cellular density increases, AI-2 molecules accumulate in the extracellular milieu. Via the Lsr ABC transporter (comprised of lsrACDB), AI-2 in medium is actively transported into permissible cells (Li et al., 2007) although passive diffusion of AI-2 across the cellular membrane is possible (Galloway et al., 2011). The Lsr transporter moves AI-2 into the bacterial cytoplasm where it is phosphorylated by LsrK (Xue et al., 2009). Phospho-AI-2 binds LsrR thereby blocking further repression of lsr-transporter genes, which leads to additional AI-2 uptake (Li et al., 2007). At this stage LsrR may bind to a “factor X” that interacts directly with the EnvZ/OmpR two-component system to activate transcription of micF [via OmpR which binds to the promoter of micF (Coyer et al., 1990; Delihas and Forst, 2001)] and/or directly regulates transcription of micC (Chen et al., 2004). sRNA micC and/or micF in turn block translation of mcpM mRNA. Because neither E. coli 25 ΔluxS nor E. coli 25 Δlsr mutants completely or continuously repress the mccPDI phenotype (Figure 1), it is likely that another pathway further contributes to regulation of micC and/or micF transcription.

Author Contributions

S-YL and DC conceived the experiments. S-YL, ZZ, JA, and JL performed the experiments. S-YL and DC analyzed the results. S-YL and DC wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The antibacterial activities of mccPDI are described under US Patent No. 9,492,500 for which DC is an author.

The other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

G. Storz at NICHD-NIH provided pGEM-2-micC and pGEM-2-micF. L. Knodler provided the pBAD18-Cm vector and reviewed a draft of this manuscript. We thank L. Orfe, C. Deobald, and J. Klein for technical assistance. This project was supported in part by USDA NIFA grant 2010-04487, and NIH Protein Biotechnology Training Program T32GM008336, and by the Agricultural Animal Health Program, Washington Agricultural Research Center, and the Paul G. Allen School for Global Animal Health at Washington State University.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02570/full#supplementary-material

References

Alberghini, S., Polone, E., Corich, V., Carlot, M., Seno, F., Trovato, A., et al. (2009). Consequences of relative cellular positioning on quorum sensing and bacterial cell-to-cell communication. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 292, 149–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01478.x

Baba, T., Ara, T., Hasegawa, M., Takai, Y., Okumura, Y., Baba, M., et al. (2006). Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008. doi: 10.1038/msb4100050

Bassler, B. L., Wright, M., Showalter, R. E., and Silverman, M. R. (1993). Intercellular signalling in Vibrio harveyi: sequence and function of genes regulating expression of luminescence. Mol. Microbiol. 9, 773–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01737.x

Blain, K. Y., Kwiatkowski, W., and Choe, S. (2010). The functionally active Mistic-fused histidine kinase receptor, EnvZ. Biochemistry 49, 9089–9095. doi: 10.1021/bi1009248

Blanchard, A. E., Liao, C., and Lu, T. (2016). An ecological understanding of quorum sensing-controlled bacteriocin synthesis. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 9, 443–454. doi: 10.1007/s12195-016-0447-6

Brouwer, E., and Van Weerden, E. J. (1956). Osmotic pressure in the intestine of the cow. Nature 178:211. doi: 10.1038/178211a0

Chen, C. Y., Nace, G. W., and Irwin, P. L. (2003). A 6 x 6 drop plate method for simultaneous colony counting and MPN enumeration of Campylobacter jejuni, Listeria monocytogenes, and Escherichia coli. J. Microbiol. Methods 55, 475–479. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(03)00194-5

Chen, S., Zhang, A., Blyn, L. B., and Storz, G. (2004). MicC, a second small-RNA regulator of Omp protein expression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186, 6689–6697. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.20.6689-6697.2004

Connolly, J. P., Finlay, B. B., and Roe, A. J. (2015). From ingestion to colonization: the influence of the host environment on regulation of the LEE encoded type III secretion system in enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 6:568. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00568

Coyer, J., Andersen, J., Forst, S. A., Inouye, M., and Delihas, N. (1990). micF RNA in ompB mutants of Escherichia coli: different pathways regulate micF RNA levels in response to osmolarity and temperature change. J. Bacteriol. 172, 4143–4150. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.8.4143-4150.1990

Datsenko, K. A., and Wanner, B. L. (2000). One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297

Delihas, N., and Forst, S. (2001). MicF: an antisense RNA gene involved in response of Escherichia coli to global stress factors. J. Mol. Biol. 313, 1–12. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5029

DeLisa, M. P., Valdes, J. J., and Bentley, W. E. (2001). Quorum signaling via AI-2 communicates the “Metabolic Burden” associated with heterologous protein production in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 75, 439–450. doi: 10.1002/bit.10034

de Lorenzo, V. (1985). Factors affecting microcin E492 production. J. Antibiot. 38, 340–345. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.340

Drider, D., Fimland, G., Hechard, Y., McMullen, L. M., and Prevost, H. (2006). The continuing story of class IIa bacteriocins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 564–582. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00016-05

Duquesne, S., Destoumieux-Garzon, D., Peduzzi, J., and Rebuffat, S. (2007). Microcins, gene-encoded antibacterial peptides from enterobacteria. Nat. Prod. Rep. 24, 708–734. doi: 10.1039/b516237h

Dyszel, J. L., Smith, J. N., Lucas, D. E., Soares, J. A., Swearingen, M. C., Vross, M. A., et al. (2010). Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium can detect acyl homoserine lactone production by Yersinia enterocolitica in mice. J. Bacteriol. 192, 29–37. doi: 10.1128/JB.01139-09

Eberhart, L. J., Deringer, J. R., Brayton, K. A., Sawant, A. A., Besser, T. E., and Call, D. R. (2012). Characterization of a novel microcin that kills enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 and O26. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 6592–6599. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01067-12

Eberhart, L. J., Ochoa, J. N., Besser, T. E., and Call, D. R. (2014). Microcin MccPDI reduces the prevalence of susceptible Escherichia coli in neonatal calves. J. Appl. Microbiol. 117, 340–346. doi: 10.1111/jam.12535

Federle, M. J. (2009). Autoinducer-2-based chemical communication in bacteria: complexities of interspecies signaling. Contrib. Microbiol. 16, 18–32. doi: 10.1159/000219371

Galloway, W. R., Hodgkinson, J. T., Bowden, S. D., Welch, M., and Spring, D. R. (2011). Quorum sensing in Gram-negative bacteria: small-molecule modulation of AHL and AI-2 quorum sensing pathways. Chem. Rev. 111, 28–67. doi: 10.1021/cr100109t

Guzman, L. M., Belin, D., Carson, M. J., and Beckwith, J. (1995). Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177, 4121–4130.

Heckman, K. L., and Pease, L. R. (2007). Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat. Protoc. 2, 924–932. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.132

Li, J., Attila, C., Wang, L., Wood, T. K., Valdes, J. J., and Bentley, W. E. (2007). Quorum sensing in Escherichia coli is signaled by AI-2/LsrR: effects on small RNA and biofilm architecture. J. Bacteriol. 189, 6011–6020. doi: 10.1128/JB.00014-07

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Maki, L. R., and Picard, K. (1965). Normal intestinal flora of cattle fed high-roughage rations. J. Bacteriol. 89, 1244–1249.

Michael, B., Smith, J. N., Swift, S., Heffron, F., and Ahmer, B. M. (2001). SdiA of Salmonella enterica is a LuxR homolog that detects mixed microbial communities. J. Bacteriol. 183, 5733–5742. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.19.5733-5742.2001

Miller, S. T., Xavier, K. B., Campagna, S. R., Taga, M. E., Semmelhack, M. F., Bassler, B. L., et al. (2004). Salmonella typhimurium recognizes a chemically distinct form of the bacterial quorum-sensing signal AI-2. Mol. Cell 15, 677–687. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.020

Milton, D. L., O'Toole, R., Horstedt, P., and Wolf-Watz, H. (1996). Flagellin A is essential for the virulence of Vibrio anguillarum. J. Bacteriol. 178, 1310–1319. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1310-1319.1996

Mizuno, T., Kato, M., Jo, Y. L., and Mizushima, S. (1988). Interaction of OmpR, a positive regulator, with the osmoregulated ompC and ompF genes of Escherichia coli. Studies with wild-type and mutant OmpR proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 1008–1012.

Moreira, C. G., and Sperandio, V. (2016). The epinephrine/norepinephrine/autoinducer-3 interkingdom signaling system in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 874, 247–261. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-20215-0_12

Moreno, F., Gonzalez-Pastor, J. E., Baquero, M. R., and Bravo, D. (2002). The regulation of microcin B, C and J operons. Biochimie 84, 521–529. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(02)01452-9

Oh, K. H., and Cho, S. H. (2014). Interaction between the quorum sensing and stringent response regulation systems in the enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 EDL933 strain. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24, 401–407. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1310.10091

Papenfort, K., and Bassler, B. L. (2016). Quorum sensing signal-response systems in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14, 576–588. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.89

Piskunova, J., Maisonneuve, E., Germain, E., Gerdes, K., and Severinov, K. (2017). Peptide-nucleotide antibiotic Microcin C is a potent inducer of stringent response and persistence in both sensitive and producing cells. Mol. Microbiol. 104, 463–471. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13640

Ren, D., Bedzyk, L. A., Ye, R. W., Thomas, S. M., and Wood, T. K. (2004). Stationary-phase quorum-sensing signals affect autoinducer-2 and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 2038–2043. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.4.2038-2043.2004

Sabag-Daigle, A., Soares, J. A., Smith, J. N., Elmasry, M. E., and Ahmer, B. M. (2012). The acyl homoserine lactone receptor, SdiA, of Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium does not respond to indole. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 5424–5431. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00046-12

Sawant, A. A., Casavant, N. C., Call, D. R., and Besser, T. E. (2011). Proximity-dependent inhibition in Escherichia coli isolates from cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 2345–2351. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03150-09

Schauder, S., Shokat, K., Surette, M. G., and Bassler, B. L. (2001). The LuxS family of bacterial autoinducers: biosynthesis of a novel quorum-sensing signal molecule. Mol. Microbiol. 41, 463–476. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02532.x

Schmidt, M., Zheng, P., and Delihas, N. (1995). Secondary structures of Escherichia coli antisense micF RNA, the 5′-end of the target ompF mRNA, and the RNA/RNA duplex. Biochemistry 34, 3621–3631. doi: 10.1021/bi00011a017

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S., and Eliceiri, K. W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089

Simcikova, M., Prather, K. L., Prazeres, D. M., and Monteiro, G. A. (2014). On the dual effect of glucose during production of pBAD/AraC-based minicircles. Vaccine 32, 2843–2846. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.02.035

Simon, R., Priefer, U., and Pühler, A. (1983). A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic-engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Bio-Technology 1, 784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784

Smith, J. L., Fratamico, P. M., and Novak, J. S. (2004). Quorum sensing: a primer for food microbiologists. J. Food Prot. 67, 1053–1070. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-67.5.1053

Soares, J. A., and Ahmer, B. M. (2011). Detection of acyl-homoserine lactones by Escherichia and Salmonella. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2011.01.006

Socias, S. B., Vincent, P. A., and Salomon, R. A. (2009). The leucine-responsive regulatory protein, Lrp, modulates microcin J25 intrinsic resistance in Escherichia coli by regulating expression of the YojI microcin exporter. J. Bacteriol. 191, 1343–1348. doi: 10.1128/JB.01074-08

Sperandio, V., Li, C. C., and Kaper, J. B. (2002). Quorum-sensing Escherichia coli regulator A: a regulator of the LysR family involved in the regulation of the locus of enterocyte effacement pathogenicity island in enterohemorrhagic E. coli. Infect. Immun. 70, 3085–3093. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.3085-3093.2002

Sperandio, V., Mellies, J. L., Nguyen, W., Shin, S., and Kaper, J. B. (1999). Quorum sensing controls expression of the type III secretion gene transcription and protein secretion in enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 15196–15201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15196

Sperandio, V., Torres, A. G., Giron, J. A., and Kaper, J. B. (2001). Quorum sensing is a global regulatory mechanism in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157: H7. J. Bacteriol. 183, 5187–5197. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.17.5187-5197.2001

Sperandio, V., Torres, A. G., Jarvis, B., Nataro, J. P., and Kaper, J. B. (2003). Bacteria-host communication: the language of hormones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 8951–8956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1537100100

Sun, J., Daniel, R., Wagner-Dobler, I., and Zeng, A. P. (2004). Is autoinducer-2 a universal signal for interspecies communication: a comparative genomic and phylogenetic analysis of the synthesis and signal transduction pathways. BMC Evol. Biol. 4:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-36

Surette, M. G., and Bassler, B. L. (1998). Quorum sensing in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 7046–7050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7046

Surette, M. G., and Bassler, B. L. (1999). Regulation of autoinducer production in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 31, 585–595. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01199.x

Taga, M. E., Semmelhack, J. L., and Bassler, B. L. (2001). The LuxS-dependent autoinducer AI-2 controls the expression of an ABC transporter that functions in AI-2 uptake in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 42, 777–793. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02669.x

Vogel, J., and Papenfort, K. (2006). Small non-coding RNAs and the bacterial outer membrane. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9, 605–611. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.10.006

Walters, M., Sircili, M. P., and Sperandio, V. (2006). AI-3 synthesis is not dependent on luxS in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188, 5668–5681. doi: 10.1128/JB.00648-06

Walters, M., and Sperandio, V. (2006). Autoinducer 3 and epinephrine signaling in the kinetics of locus of enterocyte effacement gene expression in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 74, 5445–5455. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00099-06

Wang, L., Li, J., March, J. C., Valdes, J. J., and Bentley, W. E. (2005). luxS-dependent gene regulation in Escherichia coli K-12 revealed by genomic expression profiling. J. Bacteriol. 187, 8350–8360. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.24.8350-8360.2005

Wright, P. R., Georg, J., Mann, M., Sorescu, D. A., Richter, A. S., Lott, S., et al. (2014). CopraRNA and IntaRNA: predicting small RNA targets, networks and interaction domains. Nucleic. Acids Res. 42, W119–W123. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku359

Xue, T., Zhao, L., Sun, H., Zhou, X., and Sun, B. (2009). LsrR-binding site recognition and regulatory characteristics in Escherichia coli AI-2 quorum sensing. Cell Res. 19, 1258–1268. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.91

Zhao, Z., Eberhart, L. J., Orfe, L. H., Lu, S. Y., Besser, T. E., and Call, D. R. (2015). Genome-wide screening identifies six genes that are associated with susceptibility to Escherichia coli Microcin, P. D. I. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 6953–6963. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01704-15

Keywords: autoinducer-2, bacteriocin, microcin, mccPDI, luxS, lsr, quorum sensing

Citation: Lu S-Y, Zhao Z, Avillan JJ, Liu J and Call DR (2017) Autoinducer-2 Quorum Sensing Contributes to Regulation of Microcin PDI in Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 8:2570. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02570

Received: 26 August 2017; Accepted: 11 December 2017;

Published: 22 December 2017.

Edited by:

Yuji Morita, Aichi Gakuin University, JapanReviewed by:

Konstantin Severinov, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, United StatesMichael Chikindas, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, United States

Copyright © 2017 Lu, Zhao, Avillan, Liu and Call. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Douglas R. Call, ZHJjYWxsQHdzdS5lZHU=

Shao-Yeh Lu

Shao-Yeh Lu Zhe Zhao

Zhe Zhao Johannetsy J. Avillan

Johannetsy J. Avillan Jinxin Liu

Jinxin Liu Douglas R. Call

Douglas R. Call