94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 08 December 2017

Sec. Evolutionary and Genomic Microbiology

Volume 8 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02434

This article is part of the Research Topic Microbial Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Biodiversity View all 28 articles

Aeromonas sobria is a mesophilic motile aeromonad currently depicted as an opportunistic pathogen, despite increasing evidence of mutualistic interactions in salmonid fish. However, the determinants of its host-microbe associations, either mutualistic or pathogenic, remain less understood than for other aeromonad species. On one side, there is an over-representation of pathogenic interactions in the A. sobria literature, of which only three articles to date report mutualistic interactions; on the other side, genomic characterization of this species is still fairly incomplete as only two draft genomes were published prior to the present work. Consequently, no study specifically investigated the biodiversity of A. sobria. In fact, the investigation of A. sobria as a species complex may have been clouded by: (i) confusion with A. veronii biovar sobria because of their similar biochemical profiles, and (ii) the intrinsic low resolution of previous studies based on 16S rRNA gene sequences and multilocus sequence typing. So far, the only high-resolution, phylogenomic studies of the genus Aeromonas included one A. sobria strain (CECT 4245 / Popoff 208), making it impossible to robustly conclude on the phylogenetic intra-species diversity and the positioning among other Aeromonas species. To further understand the biodiversity and the spectrum of host-microbe interactions in A. sobria as well as its potential genomic diversity, we assessed the genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity among five A. sobria strains: two clinical isolates recovered from infected fish (JF2635 and CECT 4245), one from an infected amphibian (08005) and two recently isolated brook charr probionts (TM12 and TM18) which inhibit in vitro growth of A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida (a salmonid fish pathogen). A phylogenomic assessment including 2,154 softcore genes corresponding to 946,687 variable sites from 33 Aeromonas genomes confirms the status of A. sobria as a distinct species divided in two subclades, with 100% bootstrap support. The phylogenomic split of A. sobria in two subclades is corroborated by a deep dichotomy between all five A. sobria strains in terms of inhibitory effect against A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida, gene contents and codon usage. Finally, the antagonistic effect of A. sobria strains TM12 and TM18 suggests novel control methods against A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida.

Aeromonas spp. is a genus of Gammaproteobacteria with substantial heterogeneity among species and subspecies in terms of environmental distribution, host range and growth conditions (Cahill, 1990; Janda and Abbott, 2010; Vincent et al., 2016). Aeromonads are ubiquitous in aquatic environments worldwide (Hazen et al., 1978; Chowdhury et al., 1990), either as (i) free-living organisms (Acinas et al., 1999), (ii) sessile life biofilms on biotic and abiotic surfaces (Talagrand-Reboul et al., 2017a) or (iii) as part of the natural microbiota of amphibians, mammals, reptiles and fish (Popoff and Véron, 1976; Cahill, 1990).

For aeromonads associated with fish hosts, there is a broad spectrum of symbiotic interactions, from mutualism (Gibson et al., 1998; Gunasekara et al., 2011) to pathogenicity (Austin and Austin, 2012a,b). The type of interaction can shift in a given host–microbe system, depending on overall host health and several environmental factors such as temperature, fish population density and water quality (Austin and Austin, 2012a,b). For instance, water temperatures above 17°C may trigger acute episodes of furunculosis (A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida) in salmonids, with >90% mortality rates in less than a week post-infection (Scott, 1968), whereas for temperatures less than 12°C, fish may either be chronically infected (presence of skin nodules without mortalities) or become asymptomatic carriers (Schachte, 2002). Water temperature is indeed a critical factor, as climate change is predicted to elevate mean temperatures of some North American lakes and rivers to an optimum for A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida growth (Tam, 2009; Tam et al., 2011).

Interactions of aeromonads in a given host-microbe system are further controlled by other microbial strains that colonize host body surfaces composing the so called microbiota. Among members of the microbiota, some strains are documented to exert antagonistic effects against pathogenic strains (Boutin et al., 2012, 2013; Goulden et al., 2012; Schubiger et al., 2015) including aeromonads (Zhang et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2017; Gauthier et al., 2017). Whether a host-associated aeromonad exerts mutualistic or pathogenic interactions is highly dependent on which host(s) it infects, but also its genetic repertoire, which varies greatly between strains/species (Ghatak et al., 2016).

In A. salmonicida, for example, there are five officially recognized subspecies (Dallaire-Dufresne et al., 2014). Three of them (achromogenes, masoucida and smithia) infect a broad range of hosts including cod (Gadus morhua), black rockfish (Sebastes schlegeli) and turbot (Scophtalmus maximus) (Cornick et al., 1984; Larsen and Pedersen, 1996; Han et al., 2011). Subspecies pectinolytica is without any report of pathogenicity, and subspecies salmonicida almost exclusively infects salmonid fish (Austin and Austin, 2012a). The broad host range of A. salmonicida, as well as the presence of mesophilic strains in this mainly psychrophilic species (Vincent et al., 2016), are evidence of a great genomic heterogeneity and complexity. Indeed, the A. salmonicida pangenome (i.e., total non-redundant genes among 26 strains) is made of 8,164 genes, of which 59.2% are accessory genes (Vincent and Charette, 2017). The A. salmonicida pangenome is “open,” suggesting a high prevalence of genetic material exchanges across other bacteria sharing the same environment (Rouli et al., 2015).

Similarly, motile aeromonads A. hydrophila, A. veronii and A. caviae also exhibit open pangenomes with a high species-wise proportion of accessory genes (61.7%, 53.4%, and 50.9% respectively), with strong variation in terms of antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes (Ghatak et al., 2016). A. media, noted for its remarkable genomic and phenotypic heterogeneities, shows the highest known species-wise proportion of accessory genes for an Aeromonas species (68.4%) (Talagrand-Reboul et al., 2017b).

Genome “openness,” i.e., strong heterogeneity and high exchangeability of genes, seems to be a defining trait of this genus. This strong genomic heterogeneity, revealed by next-generation sequencing, has led to major reclassifications in the Aeromonas taxonomy (Beaz-Hidalgo et al., 2013, 2015). Indeed, of all 30 Aeromonas species with valid taxonomic status, half were described since the 2005 edition of the Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (Boone et al., 2005). Novel species continue to be described (Figueras et al., 2017).

However, there are other relevant Aeromonas species complexes whose diversity and complexity has not been as thoroughly characterized. To this respect, one example of interest is Aeromonas sobria (sensu Popoff and Véron, 1976), a mesophilic motile aeromonad currently depicted as an opportunistic pathogen of freshwater fish, amphibians and reptiles (Wahli et al., 2005; Janda and Abbott, 2010; Austin and Austin, 2012b; Yang Q.-H. et al., 2017). In spite of increasing evidence of mutualistic interactions mediated by A. sobria strains (Brunt and Austin, 2005; Brunt et al., 2007; Pieters et al., 2008), the determinants of its host-microbe associations remain less understood than for other aeromonad species such as A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida (Garduño and Kay, 1992; Garduño et al., 1993; Vanden Bergh and Frey, 2013). Indeed, the current literature on A. sobria is not only scarce with respect to other aeromonads, but is also strongly biased by an over-representation of pathogenic interactions.

From 1981 to date, PubMed referenced 142 articles dedicated to A. sobria while ISI Web of Science referenced 140 A. sobria articles from 1978 to date. Articles specifically discussing A. veronii biovar sobria are not included in this estimate. This constitutes about 10 times less literature than for A. hydrophila, a well-documented fish and human opportunistic pathogen (Cipriano et al., 1984; Janda and Abbott, 2010) and about five times less literature than for A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida, a major pathogen of salmonids (Austin and Austin, 2012a; Dallaire-Dufresne et al., 2014). There are only three reports on mutualistic interactions by A. sobria (Brunt and Austin, 2005; Brunt et al., 2007; Pieters et al., 2008), all of which dealt with the same A. sobria strain (GC2).

This rough estimate of 140 A. sobria articles may be lower: prior to the description of A. veronii (Hickman-Brenner et al., 1987), several ornithine-decarboxylase negative A. veronii strains (now referred to as A. veronii biovar sobria) were incorrectly labeled as A. sobria. As a consequence, epidemiology prior to 1987 may be unreliable to this regard. Ironically, the majority of those articles, referenced in either PubMed or Web of Science, are outbreak reports of immunocompromised human patients. Unlike A. veronii, few A. sobria (sensu stricto) strains have been isolated from sources other than fish and aquatic environments (Janda and Abbott, 2010).

Next-generation sequencing data on A. sobria is also scarce. Prior to this publication, only two genome assemblies (both drafts) were available on GenBank, compared to the 61 entries for A. hydrophila and 36 for A. salmonicida. The genome of the type strain CECT 4245 was sequenced through a large-scale study on the genus Aeromonas (Colston et al., 2014) while the one of 08005 was published as a Genome Announcement (Yang Q.-H. et al., 2017). Consequently, no study specifically investigated the genomic features and diversity of A. sobria.

To increase our knowledge about the spectrum of host–microbe interactions in A. sobria as well as its biodiversity, we report the comparative phenotypic and genomic analysis of five host-associated A. sobria strains including two mutualistic strains with strong in vitro antagonistic effect against A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida. Genome sequencing and comparative analyses of these strains revealed unexpected heterogeneity between all five A. sobria strains in terms of phylogeny, codon usage and gene contents, which closely correlates with their phenotype regarding their inhibitory effect against A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida.

Aeromonas sobria strains TM12 and TM18 were both isolated in 2015 from the intestinal contents of an adult brook charr (Salvelinus fontinalis) from Lake Prime-Huron, Quebec, Canada. Strain JF2635 was isolated in 2001 from a European perch (Perca fluviatilis) in Switzerland (Wahli et al., 2005). Strain CECT 4245 (formerly known as Popoff 208) was isolated from an infected fish specimen (Popoff and Véron, 1976). All A. sobria isolates were grown on lysogeny broth (LB) agar or Tryptic Soy Agar plates (TSA, BD Diagnostics) plates at 18°C or 30°C, except recently sequenced strain 08005 (Yang Q.-H. et al., 2017) which was only included in the comparative genomic analyses. Indeed, this novel genome sequence (08005) was published after in vitro assays were completed. Given the scarcity of A. sobria genome sequences, we chose to include this strain in comparative genomic analyses, despite the absence of in vitro results, in order to maximize taxon sampling.

Bacterial lawns of ten A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida strains (Supplementary Table 1) were prepared by streaking a sterile swab dipped in liquid culture (OD600 = 0.7) on TSA plates. Wells were punched in the agar using sterile pipette tips with a diameter of 3.5 mm. For each A. sobria isolate, 10 μL of liquid culture (OD600 = 0.7) were dispensed in an assigned well. Plates were incubated at 18°C for 96 h. Inhibition surfaces around the wells were measured on 23.6 pixel/mm scans with software ImageJ version 1.48k (Schneider et al., 2012), with the well area subtracted from the whole inhibition area.

For each A. sobria isolate, ECPs were recovered by centrifuging overnight liquid cultures incubated at 18°C for 24 h in LB broth, all adjusted to OD600 = 0.7. Culture supernatants (CS), obtained by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, were then filtered with a 0.2 μm Filtropur S syringe disk filter (Sarstedt), arrayed on a Bioscreen C microplate (Growth Curves AB Ltd, Helsinki, Finland), and supplemented with an equal volume of A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida 01-B526 liquid culture in LB broth adjusted at OD600 ∼ 0.05. A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida 01-B526 CS and fresh LB medium were used as neutral and negative controls for A. sobria CSs, respectively. Mixtures were incubated in a Bioscreen C plate reader at 18°C for 48 h, with OD600 measured at each hour. Statistical significance of growth differences between conditions was assessed with a one-way ANOVA for repeated measures over time (dftime = 47, dfconditions = 4, α = 0.05). Data used for testing were balanced (i.e., equal number of observations per condition), and respected the assumptions of normality (Shapiro–Wilk test: W = 0.98407, p = 0.9899) and homoscedasticity (Bartlett’s test: K2 = 2.2485, df = 4, p = 0.6902). Post hoc comparisons of means were performed using Tukey’s HSD test only if a statistically significant difference was detected by ANOVA.

The ability of A. sobria to produce biofilms in liquid broth was verified with the microtiter dish assay described by O’Toole (2011) with minor modifications. Briefly, overnight LB broth cultures adjusted at OD600 = 0.9 were diluted 1:100 in either LB-Miller or Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB, BD Diagnostics); 100 μL of each diluted culture were arrayed in triplicates on disposable PVC U-bottomed plates (VWR International). Plates were incubated at 30°C without shaking for 6 h. After incubation, OD600 was measured to estimate bacterial abundance in each culture. Biofilms were stained by adding 25 μL of 1% aqueous Crystal Violet solution in each well, and were let standing for 15 min at room temperature (RT). Wells were rinsed abundantly with distilled water. Wells were then washed twice with 200 μL 95% ethanol, which was kept and arrayed on a clean microtiter plate. Biofilms were quantified by reading the OD600 in each ethanol/Crystal Violet mixture. Statistical significance of growth differences between conditions was assessed with a two-way ANOVA (Factors: Growth media and A. sobria strain, dfmedia = 1, dfstrain = 4, α = 0.05). Data used for testing were balanced (i.e., had an equal number of observations per condition), and were log10-transformed to improve normality (Shapiro–Wilk test: W = 0.90401, p = 0.01054) and homoscedasticity (Levene’s test: df = 9, F = 1.0206, p = 0.4571). No other data transformation improved normality and homoscedasticity as efficiently as the log10 transformation. Post hoc comparisons of means were performed using Tukey’s HSD test only if a statistically significant difference was detected by ANOVA.

For each A. sobria isolate, 400 μL of overnight culture in LB adjusted at OD600 ∼ 0.05 were arrayed on a sterile transparent covered plate (CORNING). The plate was incubated at 30°C in an Infinite 200 PRO microplate incubator/reader equipped with a 595 nm absorbance filter (TECAN, Morrisville, NC, United States). The plate was shaken (200 RPM) for 48 h; OD595 was measured at each incubation cycle of 15 min.

The total genomic DNA of A. sobria strains JF2635, TM12, and TM18 was extracted using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Canada). The sequencing libraries were prepared using a KAPA Hyper Prep Kit and were sequenced by next-generation sequencing (NGS) on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina technology) by the Plateforme d’Analyse Génomique of the Institut de Biologie Intégrative et des Systèmes (IBIS, Université Laval). The resulting sequencing reads were de novo assembled into contiguous sequences using the A5-miseq pipeline version 20160825 (Tritt et al., 2012). Contigs were ordered using mauveAligner (Rissman et al., 2009) with the complete genome of Aeromonas veronii B565 (CP002607.1) as a reference. The complete draft genomes were annotated with RAST (Aziz et al., 2008) and the NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) and deposited in the public database GenBank (TM12: NQML00000000, TM18: NQMM00000000, and JF2635: LJZX00000000). The whole genome sequence of A. sobria CECT 4245 (GenBank: CDBW00000000.1) and 08005 (GenBank: NZ_MKFU00000000) were already available prior to this study.

The high-copy plasmid sequences were recovered by downsampling the sequencing reads using seqtk1 before re-performing de novo assemblies with the A5-miseq pipeline. The plasmid sequences were annotated with the RAST web server (Aziz et al., 2008) and were manually curated. The presence or absence of a type II toxin-antitoxin locus was assessed for each sequence using TAfinder (Shao et al., 2011). Plasmid sequences were deposited on GenBank (MF770238 and MF770239 for strain JF2635; MF770240, MF770241, and MF770242 for strain TM18).

In addition to three A. sobria genome sequences produced by the present study, 30 genome sequences from representative strains of all Aeromonas species available in GenBank were downloaded, thus making a dataset of 33 genomes (Supplementary Table 2). To avoid annotation bias, all the sequences were locally annotated with Prokka version 1.12-beta (Seemann, 2014). Homology links between the coding sequences were detected with GET_HOMOLOGUES version 20170105 (Contreras-Moreira and Vinuesa, 2013) using two algorithms, COG (Kristensen et al., 2010) and OMCL (Li et al., 2003). Homologous sequences detected with both algorithms were kept for the subsequent analyzes. The 2,154 nucleotidic sequences corresponding to orthologous genes of the softcore (genes present in at least 95% of the genomes) and without paralogous ambiguity were codon aligned by muscle version 3.7 (Edgar, 2004) through TranslatorX (Abascal et al., 2010). Monomorphic sites were removed for each alignment with BMGE version 1.2 (Criscuolo and Gribaldo, 2010). All the sequences were concatenated and partitioned into a supermatrix by AMAS (Borowiec, 2016). The best-fit model was found for each partition using IQ-TREE version 1.5.3 (Nguyen et al., 2015). Finally, a maximum-likelihood tree was inferred also using IQ-TREE and the branch supports obtained with 10,000 ultrafast bootstraps (Minh et al., 2013). The average nucleotide identity (ANI) was computed for the 33 taxa using pyani (Pritchard et al., 2016) and NUCmer version 3.1 (Kurtz et al., 2004).

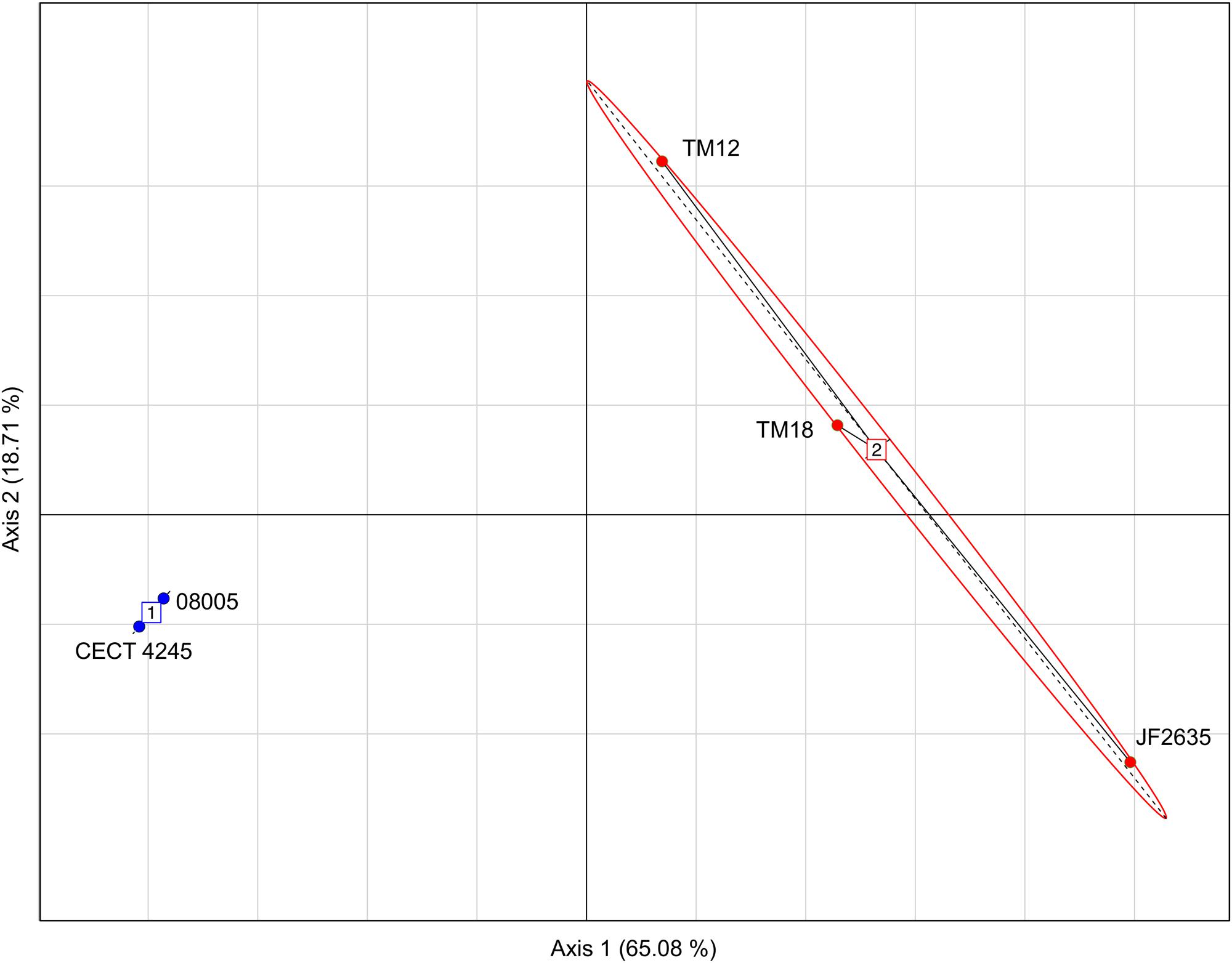

The pangenome of all five A. sobria strains studied here was inferred using GET_HOMOLOGUES (Contreras-Moreira and Vinuesa, 2013), allowing to sort the genes in four categories based on orthologous gene cluster frequency distribution: core genes (present in all genomes), softcore (present in 95% of all genomes), cloud (present in 1 or 2 genomes only) and shell (all remaining genes). Relative Synonymous Codon Usage (RSCU) was computed using DAMBE6 (Xia, 2017). The principal components analysis (PCA) used to differentiate the isolates in two groups based on the RSCU values was performed by the R package ade4 (Dray and Dufour, 2007). Antibiotic resistance genes were found using the resistance gene identifier (RGI) from the CARD database (McArthur et al., 2013). Genes implicated in a secretion system were found by TXSScan (Abby et al., 2016). Prophages were detected with PHASTER (Arndt et al., 2016) using pseudo-finished genome assemblies prepared with CONTIGuator v2.7.1 (Galardini et al., 2011) using the A. veronii B565 complete genome (CP002607.1) as a reference chromosome for contig alignments.

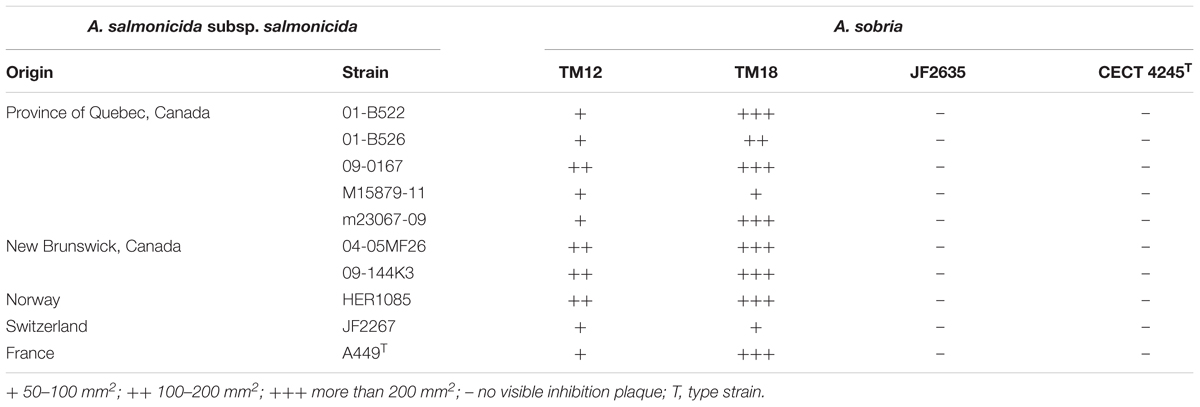

Two of the A. sobria strains (TM12 and TM18) analyzed in this study are gut symbionts recovered from healthy brook charr (Salvelinus fontinalis) (Table 1). Both were isolated in a research project aiming to study the interactions between resident brook charr bacteria and A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida. Both strains had strong, yet qualitatively different in vitro inhibitory effects against fish pathogen A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida (Table 2). This finding was interesting because two A. sobria strains were recovered from healthy specimens, yet also had an inhibitory effect against A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida which is also part of the resident brook charr microbiota (Dallaire-Dufresne et al., 2014). This prompted the assessment of this antagonistic effect in other A. sobria strains (JF2635, CECT 4245), which are clinical isolates recovered from infected fish (Table 1). No data regarding their inhibitory effect against A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida was available prior to this study.

TABLE 2. Diffusible inhibitory effect of A. sobria strains on TSA bacterial lawns of A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida, after 96 h at 18°C.

While A. sobria isolates TM12 and TM18 had an antagonistic effect against 10 strains of A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida from various hosts and geographical origins (Table 2), CECT 4245 and JF2635 did not show any disruptive effect on the growth of any A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida strain, even after 96 h. Radial inhibition on A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida bacterial lawns by TM12 and TM18 suggests involvement of diffusible inhibitory compounds, even though major differences were observed between these two strains. Strain TM12 produced inhibition halos overlapping the diffusion area of a blue pigment while TM18 did not exhibit any visible pigmentation, but a significantly stronger antagonistic effect (Supplementary Figure 1). Production of inhibition zones on A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida lawns indicates that A. sobria TM12 and TM18 (but neither JF2635 nor CECT 4245) can produce diffusible antimicrobial compounds that inhibit A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida. Interestingly, both strains that were isolated as causative infectious agents (JF2635 and CECT 4245) had no inhibitory effect against A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida, whereas TM12 and TM18 (recovered from asymptomatic fish) had a strong antimicrobial effect on A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida.

The production of antimicrobial compounds targeting A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida has also been assessed by exposing A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida 01-B526 to A. sobria extracellular products (ECPs) in culture supernatants (Supplementary Figure 2). Interestingly, results do not follow the trend observed in the agar assays described above. In fact, no significant change of A. salmonicida growth was detected after 48 h growth [F(4,10) = 0.482, p = 0.749].

It is possible that the inhibitory compounds produced in agar are not produced when grown in liquid broth. Indeed, in solid medium assays, A. sobria strains were in conditions of high cell density without direct contact with A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida cells, i.e., conditions resembling a bacterial biofilm (McBain, 2009). On the opposite, in liquid broth assays, A. sobria cells were in conditions more akin to planktonic life before recovery of their ECPs (i.e., in liquid broth with continuous shaking). Therefore, the growth characteristics of A. sobria isolates in liquid broth were investigated.

All A. sobria strains undergo a similar growth pattern in LB broth (Figure 1). Stationary phase is reached after 10 h (OD600 ∼ [0.8; 0.9]), followed by gradual decline. However, one striking difference is the high levels of background noise in the TM18 growth curve throughout the stationary and decline phases. This suggests that either cell aggregation occurs in liquid cultures, or that TM18 has the ability to form significant levels of biofilms in liquid broth. The latter possibility was subsequently assessed.

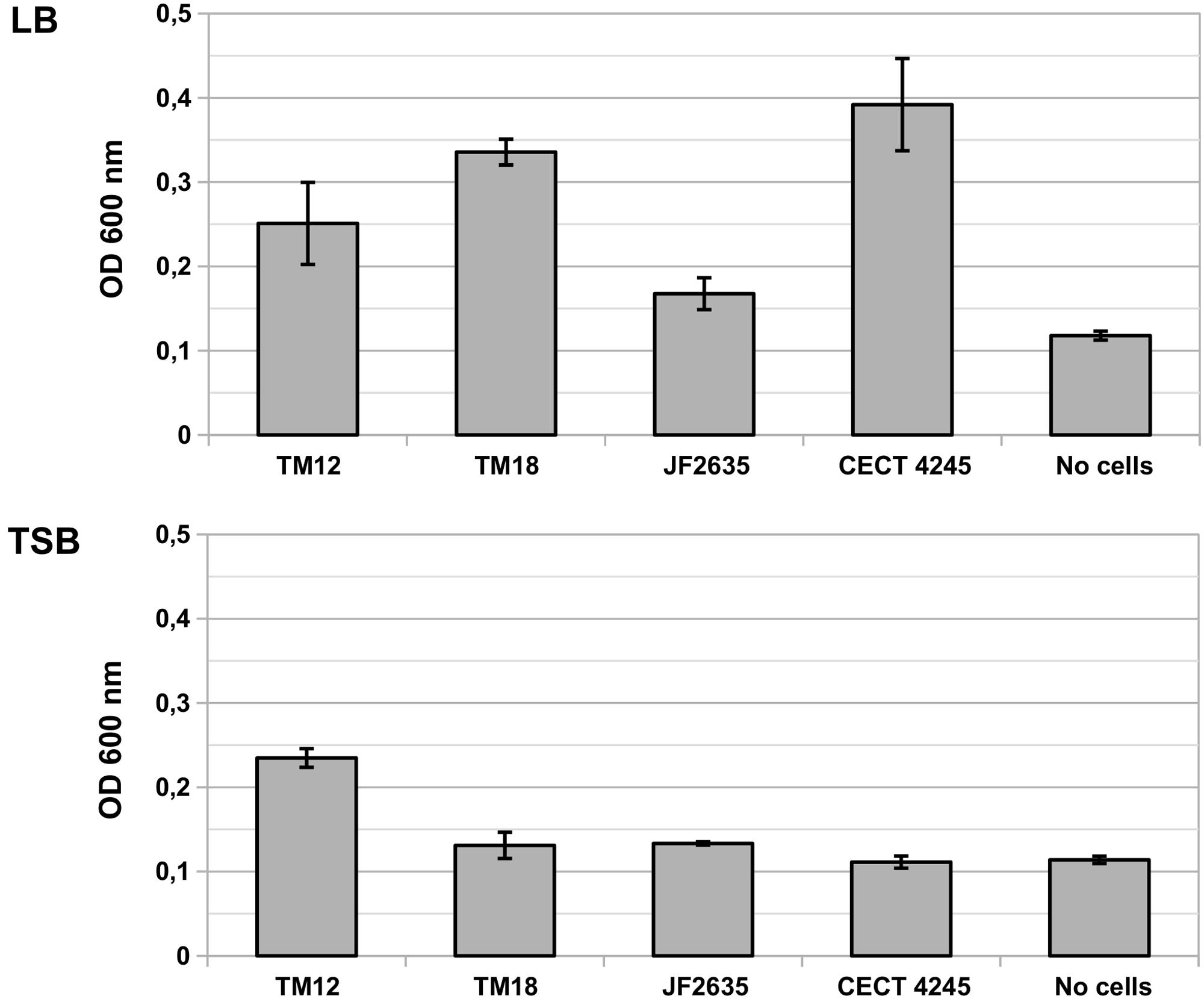

The levels of biofilm production by A. sobria are significantly different in LB than in TSB media [F(1,20) = 62.80, p = 1.35 × 10-7], and vary significantly between strains [F(4,20) = 17.87, p = 2.20 × 10-6) (Figure 2). There is a strong interaction between the growth medium and the ability of A. sobria strains to produce biofilms [F(4,20) = 16.30, p = 4.39 × 10-6).

FIGURE 2. Biofilm production in liquid cultures of A. sobria over 6 h static incubation at 30°C in LB and TSB broth. Bars indicate the OD600 of crystal violet that adsorbed in biofilms. Vertical segments indicate the standard error of the mean. This experiment was performed in triplicates.

Post hoc multiple comparisons revealed that A. sobria strains TM12, TM18 and CECT 4245 produced significant levels of biofilm compared to the no-cell control (Tukey’s HSD test, p ≤ 0.021), but with marginal between-strain differences (Tukey’s HSD test, p ≥ 0.084). Biofilm-producing strains do better in LB than in TSB (Tukey’s HSD test, p = 10-7). Strain JF2635 produced no detectable amount of biofilm over the no-cell control (Tukey’s HSD test, p = 0.65).

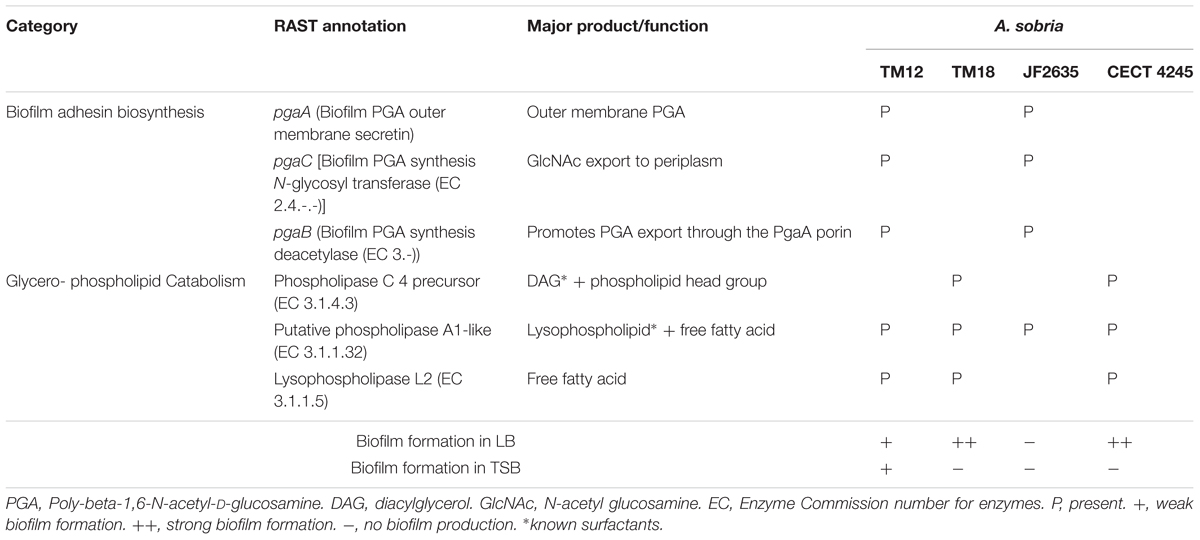

RAST genome annotations of A. sobria strains revealed that strains TM18 and CECT 4245 lack the pga operon required for the biosynthesis of biofilm adhesin poly-β-1,6-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (Table 3). This finding suggests that (i) TM18 and CECT 4245 could be more vulnerable to compounds inhibiting surface attachment (i.e., surfactants), and (ii) certain nutrients present in TSB broth but not in LB broth (i.e., enzymatic soymeal digest or glucose), could act as inhibitors of biofilm formation. Indeed, mono- and diglycerides are known surfactants (Prajapati et al., 2012) and inhibitors of biofilm formation in Aeromonas (Ham and Kim, 2016) that can be biologically synthesized in high abundance from enzymatic soymeal digests, due to its high phospholipid content (Küllenberg et al., 2012).

TABLE 3. Differential presence of genes involved in biofilm synthesis and glycerophospholipid catabolism, with special relevance to biofilm formation in A. sobria.

Interestingly, A. sobria strains possess several phospholipase genes that could produce surfactant metabolites (Table 3). Strains TM12, TM18 and CECT 4245 are likely able to produce (i) diacylglycerol (DAG) via phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C, and (ii) free fatty acids via lysophospholipase L2. The latter are known to play a role as signal molecules involved in either biofilm formation or dispersion (Marques et al., 2015), and could lead to biofilm inhibition. Strain JF2635 (which produces no biofilm in either LB or TSB) possesses a phospholipase A1 gene but lacks lysophospholipase. In a liquid broth rich in glycerophospholipids such as TSB, this may result in a buildup of extracellular lysophospholipids which have strong detergent properties (Huang et al., 1998).

There is significant quantitative and qualitative heterogeneity among the four A. sobria strains of this study in terms of basic phenotypic traits such as (i) antagonism against another Aeromonas species; (ii) growth kinetics and iii) production of biofilms in different growth conditions. Knowing that those four strains were isolated from fairly different backgrounds (Table 1), this heterogeneity may be underlain by strong genomic divergence resulting from adaptation to different niches. It was therefore tempting to verify if the phylogenomic clustering among the A. sobria strains studied here also reflects this heterogeneity.

The pangenome of A. sobria strains studied here exhibits a species-wise proportion of accessory genes of 2,084/5,586 = 37.3% (Table 4). This is lower than reported values for other Aeromonas species complexes, where accessory genes represent 50–70% of the pangenome (see Introduction). This low proportion can be explained by the scarcity of sequence data for A. sobria (five genomes including those introduced in this publication). Indeed, a development plot of the core genome (i.e., a fit of core genome size vs. number of subsampled genomes) reveals that an asymptote has not yet been reached (i.e., the number of core genes will decrease by adding more genomes; Supplementary Figure 3A). Conversely, a development plot shows that the pangenome is “open,” i.e., it would increase if more A. sobria genomes were included in the study (Supplementary Figure 3B) (Guimarães et al., 2015; Rouli et al., 2015). This suggests much of the phylogenomic diversity of A. sobria remains to be assessed, which will be solved by the addition of more whole genome data.

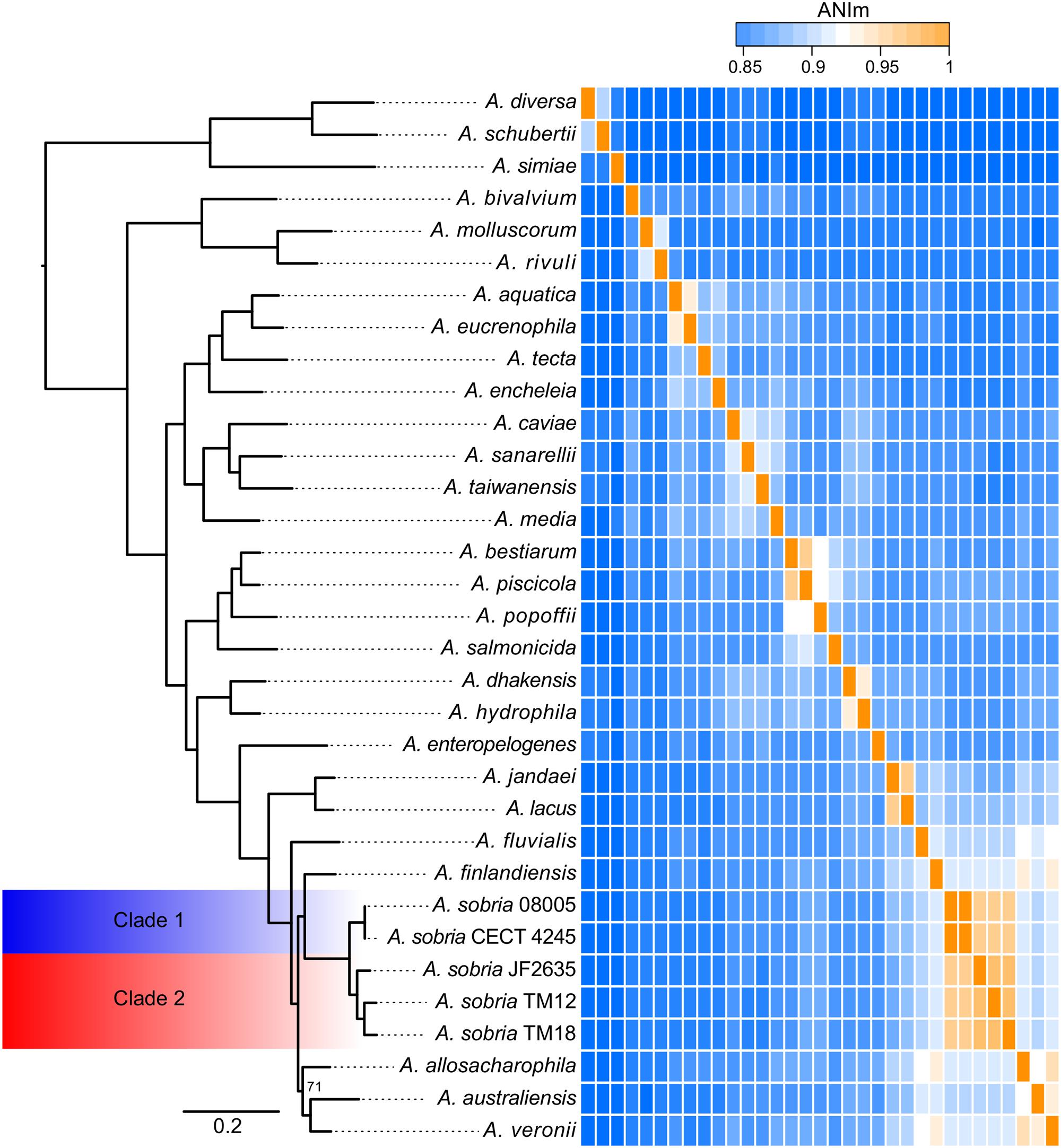

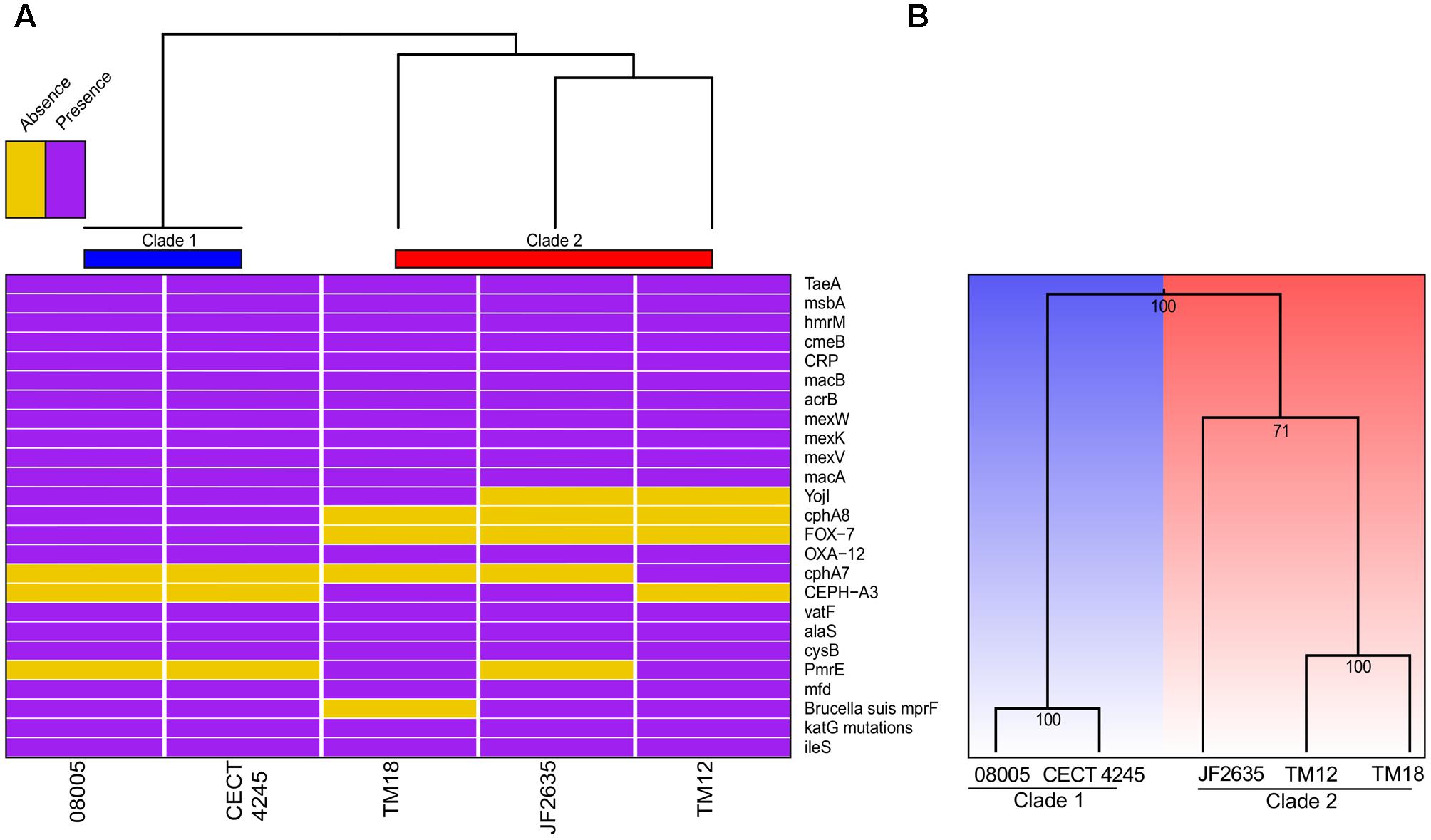

In addition to the A. sobria isolates, a set of representative strains of each Aeromonas species with whole genome sequences available in GenBank (Supplementary Table 2) has been added to get a more accurate phylogenetic resolution of the A. sobria isolates. This includes the genome sequences of a fifth A. sobria strain, 08005. This additional strain was recovered from an infected amphibian. As expected, the five A. sobria isolates formed a monophyletic group (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Phylogenomic tree of the Aeromonas softcore genome (2,154 genes present in at least 95% of 33 Aeromonas genomes), coupled to an ANIm analysis of the Aeromonas genus with an emphasis on the sobria species. All nodes are supported by bootstrap values of 100, excepted the one of allosaccharophila, which is 71. The ANIm heatmap is a square matrix; rows and columns are ordered identically.

As mentioned earlier, there is apparent confusion between A. sobria sensu stricto (Popoff and Véron, 1976) and A. veronii biovar sobria in the scientific literature, because of the similarity in their phenotypic profiles (Janda and Abbott, 2010; Austin and Austin, 2012b). However, the softcore genome phylogeny supports that A. veronii and A. sobria are distinct clades (Figure 3), as previously demonstrated by other clustering methods (Martino et al., 2011). To our knowledge, our phylogenetic assessment, which is based on 2,154 softcore gene sequences including 946,687 variable sites of 33 Aeromonas genomes, is the most robust and accurate phylogenetic positioning of A. sobria to date.

Interestingly, the sobria clade shares a near common ancestor with the A. finlandiensis species. Multilocus sequence analysis trees (7 and 15 housekeeping genes) from the paper having reported this species placed it near the species A. allosaccharophila and A. veronii, while A. sobria was more basal (Beaz-Hidalgo et al., 2015). A recent study, based on two concatenated gene sequences reported A. sobria forming a clade along with A. allosaccharophila while A. veronii was predicted to share a recent common ancestor with the one of A. finlandiensis (Sanglas et al., 2017). In addition to the present study, two papers describing phylogenies of the Aeromonas genus based on core and softcore genomes have been published (Colston et al., 2014; Vincent et al., 2016). Unfortunately, these two publications did not include A. finlandiensis because those two studies were initiated prior to its description (Beaz-Hidalgo et al., 2015). We believe that more complete genomes of strains from the A. finlandiensis species is required to have a clearer taxonomic positioning relative to A. sobria.

The average nucleotide identity (ANI) is known to be a gold standard to determine the relatedness of bacterial species, where a value of ∼95–96% correlates with the ∼70–75% DNA:DNA hybridization threshold used as a gold standard to define prokaryotic species (Konstantinidis and Tiedje, 2005; Goris et al., 2007; Colston et al., 2014; Federhen et al., 2016). The ANI values confirmed that the five A. sobria isolates are members of the same species (Figure 3). This analysis, in addition to the short phylogenetic branch lengths, showed that the strains 08005 and CECT 4245 (hereby referred to as “Clade 1”) are evolutionarily close (Shared ANI: 99.9%). It is worth noting that strains JF2635, TM12 and TM18 (hereby referred to as “Clade 2”), which all grouped together in the softcore phylogeny, exhibited substantial nucleotide diversity (Shared ANI: 96.4 ± 0.4%). The split corresponding to both clades is strongly supported with a bootstrap score of 100.

The genomic dissimilarity underlying the split into two clades was striking as it resulted mostly from the number of tRNA genes encoded by these genomes (Table 5). Clade 1 isolates harbored 20–22% less tRNA genes than clade 2. Given this extensive dichotomy in tRNA genes, it was reasonable to hypothesize that some codons could be preferred, depending on the clade. The relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) was found for each set of genes and the result was analyzed by a principal component analysis (PCA) in which the isolates were distributed as expected as in the phylogenetic tree (i.e., in two distinct groups), suggesting that a codon bias exists depending on the clade (Figure 4). Furthermore, the PCA also confirmed the more important heterogeneity within clade 2, previously evidenced in other analyses.

FIGURE 4. Principal components analysis (PCA) based on the RSCU values showing a separation between isolates from clade 1 (blue) and those from clade 2 (red).

Bacterial genomes harbor various key genes to enhance their fitness, including drug resistance and virulence factors. In A. sobria, little is known about the pool of coding genes used for antibiotic resistance mechanisms and to colonize new environments. Thorough genomic sequence investigation allowed to identify several genes conferring drug resistance (Figure 5A), many of which are coding either for efflux pumps or beta-lactam resistance proteins. This was not unsuspected knowing that aquatic environments are favorable for the spread of antibiotic resistance genes (Baquero et al., 2008), and that aeromonads are documented to be effective vectors for such genes (Henriques et al., 2006; Vincent et al., 2014; Piotrowska and Popowska, 2015; Trudel et al., 2016). Interestingly, there was a congruence regarding the phylogenetic signal between antibiotic resistance genes and the overall genomic sequence (i.e., supporting the same clade 1 and clade 2 dichotomy). The sole incongruence concerns the cluster 2 root: JF2635 roots the whole genome based phylogeny while TM18 roots the antibiotic resistance genes-based clustering (Figure 5A). Even if it is perilous to draw conclusions about evolutionary history of resistance genes in A. sobria given the small number of markers comparatively to the molecular phylogeny, the fact that both topologies are similar lets us believe that resistance genes are not mobile and are stable.

FIGURE 5. (A) Heatmap based on the presence or absence of the antibiotic resistance genes. (B) Clustering based on the presence or absence of genes implicated in secretion systems.

Secretion systems are well characterized as sophisticated protein machineries widely distributed among bacteria and are, among other things, major determinants in virulence (Costa et al., 2015; Abby et al., 2016; Green and Mecsas, 2016). As for antibiotic resistance genes, it was consequently relevant to verify the presence or absence of genes implicated in these systems (Supplementary Table 4). Here, the clustering analysis of virulence genes was even more congruent with the whole genome phylogeny than what was observed for resistance genes (Figure 5B). One of the most salient features was the absence of mandatory genes involved in the formation of a T6SSi, a secretion system exporting effectors to both bacterial and eukaryotic cells (Ho et al., 2014), for clade 2 isolates. A functional T6SS was previously reported in A. hydrophila (Suarez et al., 2008). Then, the five A. sobria genomes were predicted to harbor all mandatory genes for functional T1SS, T2SS, type IV pilus (T4P) and flagellum (Supplementary Table 5). Also the genomes of 08005, CECT 4245 and JF2635 were predicted to bear the single mandatory gene (coding for a protein having both the translocator and passenger domains) to have a functional T5aSS (Leo et al., 2012).

Of all five A. sobria strains included in this study, only two (TM18 and JF2635 from clade 2) harbored small high-copy-number plasmids (Supplementary Figure 4). TM18 has three plasmids ranging from 4,393 to 5,190 bp, whilst JF2635 harbors two plasmids (3,818 and 5,381 bp). Plasmids pJF2635-1 and pTM18-3 are ColE1-like replicons, as evidenced by the presence of genes encoding regulatory RNAs I and II involved in ColE1-type replication (Tomizawa, 1984). The other plasmids (pJF2635-2, pTM18-1 and pTM18-2) are ColE2-type replicons which have no RNA II gene but a RNA I gene complementary to the repA mRNA (Sugiyama and Itoh, 1993).

Aside from RNA I and RNA II genes, most genes found in the plasmid repertoire of A. sobria TM18 and JF2635 encode either hypothetical proteins or proteins involved in plasmid mobility and maintenance (Supplementary Figure 4; blue arrows). Two notable exceptions are:

(i) a putative vapD gene in pTM18-2, which may encode a virulence-associated protein with ssRNA endonuclease activity (Katz et al., 1992; Kwon et al., 2012). No other vap gene homologs were found in neither the plasmids nor the draft genome sequences.

(ii) a pseudogene in pTM18-1. A BLASTx search against the non-redundant protein database (NCBI) returned a hypothetical protein from an Aeromonas sp. as best hit. No putative conserved domain was detected.

A total of nine predicted phage elements were found across the five A. sobria isolates (Supplementary Table 3). Seven of those prophages were found in JF2635, of which only two were presumably intact: a Phi018p-like element (Beilstein and Dreiseikelmann, 2008) and a SJ46-like element (Yang L. et al., 2017). Only one intact prophage, a Fels-2-like element is found in both CECT 4245 and 08005 strains (clade 1), whilst only one prophage, a 9.5 kb Phi018p-like element (presumably incomplete) was found in both TM12 and TM18 strains (clade 2). There is a clear dichotomy in terms of prophage contents between strains from clade 1 (CECT 4245 and 08005) and strains from clade 2 (TM12, TM18 and JF2635). Even among clade 2 strains, there is a split, with JF2635 having substantially more phage elements (Supplementary Figure 5). The presence of many degenerated elements in JF2635 suggests that this strain acquired prophages early in the evolutionary history of clade 2. The low number of phage elements in other A. sobria strains, as opposed to JF2635, requires further investigation.

Aeromonas sobria is a mesophilic motile aeromonad whose host–microbe associations, either mutualistic or pathogenic, are less understood than for other aeromonad species. We assessed the genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity among five A. sobria strains: two brook charr probionts (TM12 and TM18) which inhibit in vitro growth of A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida, and three clinical isolates recovered from infected fish (JF2635 and CECT 4245) and an infected amphibian (08005). Comparative analysis supports a split of the A. sobria species complex in two clades.

• Clade 1 strains (08005 and CECT 4245) harbor no plasmids but a single intact Fels-2-like prophage. They also possess an identical antibiotic resistance gene profile. They have no inhibitory effect against A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida.

• Clade 2 strains (TM12, TM18 and JF2635) possess 20–22% more tRNA genes than clade 1 strains, leading to major differences in relative synonymous codon usage. They harbor no Fels-2-like prophage, but minimally an incomplete Phi018p-like prophage. There are notable differences between clade 2 strains, however. Unlike TM12 and TM18, strain JF2635 has two intact and five incomplete prophages. Only TM18 and JF2635 harbor plasmids. Their antibioresistance gene and secretion gene profiles are more heterogeneous than within clade 1. Only clade 2 strains inhibit growth of A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida (TM12 and TM18), with the exception of JF2635.

These findings illustrate how adaptation to a broad range of hosts and life strategies has shaped the evolution of the A. sobria species complex into two clades harboring significant within-clade and between-clade diversity. A. sobria has been treated as a monotypic bacterial species since its inception (Popoff and Véron, 1976; Martinez-Murcia et al., 1992; Abbott et al., 2003; Martino et al., 2011). However, the clear genomic and phenotypic division between clade 1 and clade 2 indicates that the A. sobria species complex may be composed of at least two candidates to subspecies status. Of course, the taxonomic assessment of A. sobria below the species level will be more accurate when more genome sequences will be available.

Finally, the antagonistic effect of clade 2 strains TM12 and TM18 against A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida indicates that these strains (or their products) could lead to novel control and prevention methods to mitigate this opportunistic pathogen of salmonid fish. This effect suggests a role of certain host-associated A. sobria strains in controlling the abundance of other opportunistic pathogens in their host microbiota (including other aeromonads) and deserves further investigation.

JG, AV, SC, and ND designed the experiments. JG and AV performed in vitro and in silico experiments. JG, AV, SC, and ND contributed to the manuscript.

The authors acknowledge funding from the Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l’Alimentation du Québec (INNOVAMER Program), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) and Ressources Aquatiques Québec (RAQ). JG received a Graduate Scholarship from the NSERC and AV received an Alexander Graham Bell Canada Graduate Scholarship from the NSERC. SC is a research scholar from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec en Santé.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors thank Joachim Frey (University of Bern) for the JF2635 isolate, Typhaine Morvant for the isolation of strains TM12 and TM18 and Tom Van Acker for early characterization of those strains.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02434/full#supplementary-material

Abascal, F., Zardoya, R., and Telford, M. J. (2010). TranslatorX: multiple alignment of nucleotide sequences guided by amino acid translations. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W7–W13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq291

Abbott, S. L., Cheung, W. K. W., and Janda, J. M. (2003). The genus Aeromonas: biochemical characteristics, atypical reactions, and phenotypic identification schemes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 2348–2357. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2348-2357.2003

Abby, S. S., Cury, J., Guglielmini, J., Néron, B., Touchon, M., and Rocha, E. P. C. (2016). Identification of protein secretion systems in bacterial genomes. Sci. Rep. 6:23080. doi: 10.1038/srep23080

Acinas, S. G., Antón, J., and Rodríguez-Valera, F. (1999). Diversity of free-living and attached bacteria in offshore Western Mediterranean waters as depicted by analysis of genes encoding 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, k514–522.

Arndt, D., Grant, J. R., Marcu, A., Sajed, T., Pon, A., Liang, Y., et al. (2016). PHASTER: a better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W16–W21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw387

Austin, B., and Austin, D. A. (eds). (2012a). “Aeromonadaceae representative (Aeromonas salmonicida),” in Bacterial Fish Pathogens (Dordrecht: Springer), 147–228. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4884-2_5

Austin, B., and Austin, D. A. (eds). (2012b). “Aeromonadaceae representatives (motile aeromonads),” in Bacterial Fish Pathogens (Dordrecht: Springer),k119–146. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4884-2_4

Aziz, R. K., Bartels, D., Best, A. A., DeJongh, M., Disz, T., Edwards, R. A., et al. (2008). The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75

Baquero, F., Martínez, J.-L., and Cantón, R. (2008). Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in water environments. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19, 260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.05.006

Beaz-Hidalgo, R., Latif-Eugenín, F., Hossain, M. J., Berg, K., Niemi, R. M., Rapala, J., et al. (2015). Aeromonas aquatica sp. nov. Aeromonas finlandiensis sp. nov. and Aeromonas lacus sp. nov. isolated from Finnish waters associated with cyanobacterial blooms. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 38, 161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2015.02.005

Beaz-Hidalgo, R., Martínez-Murcia, A., and Figueras, M. J. (2013). Reclassification of Aeromonas hydrophila subsp. dhakensis Huys et al. 2002 and Aeromonas aquariorum Martínez-Murcia et al. 2008 as Aeromonas dhakensis sp. nov. comb nov. and emendation of the species Aeromonas hydrophila. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 36, 171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2012.12.007

Beilstein, F., and Dreiseikelmann, B. (2008). Temperate bacteriophage PhiO18P from an Aeromonas media isolate: characterization and complete genome sequence. Virology 373, 25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.11.016

Boone, D. R., Castenholz, R. W., Garrity, G. M., Brenner, D. J., Krieg, N. R., and Staley, J. T. (2005). Bergey’s Manual® of Systematic Bacteriology. Berlin: Springer.

Borowiec, M. L. (2016). AMAS: a fast tool for alignment manipulation and computing of summary statistics. PeerJ 4:e1660. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1660

Boutin, S., Audet, C., and Derome, N. (2013). Probiotic treatment by indigenous bacteria decreases mortality without disturbing the natural microbiota of Salvelinus fontinalis. Can. J. Microbiol. 59, 662–670. doi: 10.1139/cjm-2013-0443

Boutin, S., Bernatchez, L., Audet, C., and Derôme, N. (2012). Antagonistic effect of indigenous skin bacteria of brook charr (Salvelinus fontinalis) against Flavobacterium columnare and F. psychrophilum. Vet. Microbiol. 155, 355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.09.002

Brunt, J., and Austin, B. (2005). Use of a probiotic to control lactococcosis and streptococcosis in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum). J. Fish Dis. 28, 693–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2005.00672.x

Brunt, J., Newaj-Fyzul, A., and Austin, B. (2007). The development of probiotics for the control of multiple bacterial diseases of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum). J. Fish Dis. 30, 573–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2007.00836.x

Cahill, M. M. (1990). Bacterial flora of fishes: a review. Microb. Ecol. 19, 21–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02015051

Chowdhury, M. A., Yamanaka, H., Miyoshi, S., and Shinoda, S. (1990). Ecology of mesophilic Aeromonas spp. in aquatic environments of a temperate region and relationship with some biotic and abiotic environmental parameters. Zentralbl. Hyg. Umweltmed. 190, 344–356.

Cipriano, R., Bullock, G., and Pyle, S. (1984). Aeromonas hydrophila and Other Septicemias of Fish. US Fish & Wildlife Publications. Available at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usfwspubs/134

Colston, S. M., Fullmer, M. S., Beka, L., Lamy, B., Gogarten, J. P., and Graf, J. (2014). Bioinformatic genome comparisons for taxonomic and phylogenetic assignments using Aeromonas as a test case. mBio 5:e02136-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02136-14

Contreras-Moreira, B., and Vinuesa, P. (2013). GET_HOMOLOGUES, a versatile software package for scalable and robust microbial pangenome analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 7696–7701. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02411-13

Cornick, J. W., Morrison, C. M., Zwicker, B., and Shum, G. (1984). Atypical Aeromonas salmonicida infection in Atlantic cod. Gadus morhua L. J. Fish Dis. 7, 495–499. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.1984.tb01174.x

Costa, T. R. D., Felisberto-Rodrigues, C., Meir, A., Prevost, M. S., Redzej, A., Trokter, M., et al. (2015). Secretion systems in Gram-negative bacteria: structural and mechanistic insights. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 343–359. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3456

Criscuolo, A., and Gribaldo, S. (2010). BMGE (block mapping and gathering with entropy): a new software for selection of phylogenetic informative regions from multiple sequence alignments. BMC Evol. Biol. 10:210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-210

Dallaire-Dufresne, S., Tanaka, K. H., Trudel, M. V., Lafaille, A., and Charette, S. J. (2014). Virulence, genomic features, and plasticity of Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida, the causative agent of fish furunculosis. Vet. Microbiol. 169, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.06.025

Dray, S., and Dufour, A. B. (2007). The ade4 package: implementing the duality diagram for ecologists. J. Stat. Softw. 22, 1–20. doi: 10.18637/jss.v022.i04

Edgar, R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340

Federhen, S., Rossello-Mora, R., Klenk, H.-P., Tindall, B. J., Konstantinidis, K. T., Whitman, W. B., et al. (2016). Meeting report: GenBank microbial genomic taxonomy workshop (12–13 May, 2015). Stand. Genomic Sci. 11:15. doi: 10.1186/s40793-016-0134-1

Figueras, M. J., Latif-Eugenín, F., Ballester, F., Pujol, I., Tena, D., Berg, K., et al. (2017). “Aeromonas intestinalis” and “Aeromonas enterica” isolated from human faeces, “Aeromonas crassostreae” from oyster and “Aeromonas aquatilis” isolated from lake water represent novel species. New Microbes New Infect. 15, 74–76. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2016.11.019

Galardini, M., Biondi, E. G., Bazzicalupo, M., and Mengoni, A. (2011). CONTIGuator: a bacterial genomes finishing tool for structural insights on draft genomes. Source Code Biol. Med. 6, 11. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-6-11

Gao, X.-Y., Liu, Y., Miao, L.-L., Li, E.-W., Sun, G., Liu, Y., et al. (2017). Characterization and mechanism of anti-Aeromonas salmonicida activity of a marine probiotic strain, Bacillus velezensis V4. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101, 3759–3768. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8095-x

Garduño, R. A., and Kay, W. W. (1992). Interaction of the fish pathogen Aeromonas salmonicida with rainbow trout macrophages. Infect. Immun. 60, 4612–4620.

Garduño, R. A., Thornton, J. C., and Kay, W. W. (1993). Fate of the fish pathogen Aeromonas salmonicida in the peritoneal cavity of rainbow trout. Can. J. Microbiol. 39, 1051–1058. doi: 10.1139/m93-159

Gauthier, J., Charette, S. J., and Derome, N. (2017). Draft genome sequence of Pseudomonas fluorescens ML11A, an endogenous strain from brook charr with antagonistic properties against Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida. Genome Announc. 5:e01716-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01716-16

Ghatak, S., Blom, J., Das, S., Sanjukta, R., Puro, K., Mawlong, M., et al. (2016). Pan-genome analysis of Aeromonas hydrophila, Aeromonas veronii and Aeromonas caviae indicates phylogenomic diversity and greater pathogenic potential for Aeromonas hydrophila. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 109, 945–956. doi: 10.1007/s10482-016-0693-6

Gibson, L. F., Woodworth, J., and George, A. M. (1998). Probiotic activity of Aeromonas media on the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, when challenged with Vibrio tubiashii. Aquaculture 169, 111–120. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(98)00369-X

Goris, J., Konstantinidis, K. T., Klappenbach, J. A., Coenye, T., Vandamme, P., and Tiedje, J. M. (2007). DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57, 81–91. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0

Goulden, E. F., Hall, M. R., Pereg, L. L., and Høj, L. (2012). Identification of an antagonistic probiotic combination protecting ornate spiny lobster (Panulirus ornatus) larvae against Vibrio owensii infection. PLOS ONE 7:e39667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039667

Green, E. R., and Mecsas, J. (2016). Bacterial secretion systems: an overview. Microbiol. Spectr. 4:VMBF-0012-2015. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.VMBF-0012-2015

Guimarães, L. C., Florczak-Wyspianska, J., de Jesus, L. B., Viana, M. V. C., Silva, A., Ramos, R. T. J., et al. (2015). Inside the pan-genome - methods and software overview. Curr. Genomics 16, 245–252. doi: 10.2174/1389202916666150423002311

Gunasekara, R. A., Cornillie, P., Casteleyn, C., De Spiegelaere, W., Sorgeloos, P., Simoens, P., et al. (2011). Stereology and computer assisted three-dimensional reconstruction as tools to study probiotic effects of Aeromonas hydrophila on the digestive tract of germ-free Artemia franciscana nauplii. J. Appl. Microbiol. 110, 98–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04862.x

Ham, Y., and Kim, T.-J. (2016). Inhibitory activity of monoacylglycerols on biofilm formation in Aeromonas hydrophila, Streptococcus mutans, Xanthomonas oryzae, and Yersinia enterocolitica. Springerplus 5:1526. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-3182-5

Han, H.-J., Kim, D.-Y., Kim, W.-S., Kim, C.-S., Jung, S.-J., Oh, M.-J., et al. (2011). Atypical Aeromonas salmonicida infection in the black rockfish, Sebastes schlegeli Hilgendorf, in Korea. J. Fish Dis. 34, 47–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2010.01217.x

Hazen, T. C., Fliermans, C. B., Hirsch, R. P., and Esch, G. W. (1978). Prevalence and distribution of Aeromonas hydrophila in the United States. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 36, 731–738.

Henriques, I. S., Fonseca, F., Alves, A., Saavedra, M. J., and Correia, A. (2006). Occurrence and diversity of integrons and beta-lactamase genes among ampicillin-resistant isolates from estuarine waters. Res. Microbiol. 157, 938–947. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.09.003

Hickman-Brenner, F. W., MacDonald, K. L., Steigerwalt, A. G., Fanning, G. R., Brenner, D. J., and Farmer, J. J. (1987). Aeromonas veronii, a new ornithine decarboxylase-positive species that may cause diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25, 900–906.

Ho, B. T., Dong, T. G., and Mekalanos, J. J. (2014). A view to a kill: the bacterial type VI secretion system. Cell Host Microbe 15, 9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.008

Huang, P., Liu, Q., and Scarborough, G. A. (1998). Lysophosphatidylglycerol: a novel effective detergent for solubilizing and purifying the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. Anal. Biochem. 259, 89–97. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2633

Janda, J. M., and Abbott, S. L. (2010). The genus Aeromonas: taxonomy. pathogenicity, and infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23, 35–73. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00039-09

Katz, M. E., Strugnell, R. A., and Rood, J. I. (1992). Molecular characterization of a genomic region associated with virulence in Dichelobacter nodosus. Infect. Immun. 60, 4586–4592.

Konstantinidis, K. T., and Tiedje, J. M. (2005). Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 2567–2572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409727102

Kristensen, D. M., Kannan, L., Coleman, M. K., Wolf, Y. I., Sorokin, A., Koonin, E. V., et al. (2010). A low-polynomial algorithm for assembling clusters of orthologous groups from intergenomic symmetric best matches. Bioinformatics 26, 1481–1487. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq229

Küllenberg, D., Taylor, L. A., Schneider, M., and Massing, U. (2012). Health effects of dietary phospholipids. Lipids Health Dis. 11:3. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-11-3

Kurtz, S., Phillippy, A., Delcher, A. L., Smoot, M., Shumway, M., Antonescu, C., et al. (2004). Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 5:R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12

Kwon, A.-R., Kim, J.-H., Park, S. J., Lee, K.-Y., Min, Y.-H., Im, H., et al. (2012). Structural and biochemical characterization of HP0315 from Helicobacter pylori as a VapD protein with an endoribonuclease activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 4216–4228. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1305

Larsen, J. L., and Pedersen, K. (1996). Atypical Aeromonas salmonicida isolated from diseased turbot (Scophtalmus maximus L.). Acta Vet. Scand. 37, 139–146.

Leo, J. C., Grin, I., and Linke, D. (2012). Type V secretion: mechanism(s) of autotransport through the bacterial outer membrane. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367, 1088–1101. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0208

Li, L., Stoeckert, C. J., and Roos, D. S. (2003). OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13, 2178–2189. doi: 10.1101/gr.1224503

Marques, C. N. H., Davies, D. G., and Sauer, K. (2015). Control of biofilms with the fatty acid signaling molecule cis-2-decenoic acid. Pharmaceuticals 8, 816–835. doi: 10.3390/ph8040816

Martinez-Murcia, A. J., Benlloch, S., and Collins, M. D. (1992). Phylogenetic interrelationships of members of the genera Aeromonas and Plesiomonas as determined by 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing: lack of congruence with results of DNA-DNA hybridizations. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42, 412–421. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-412

Martino, M. E., Fasolato, L., Montemurro, F., Rosteghin, M., Manfrin, A., Patarnello, T., et al. (2011). Determination of microbial diversity of Aeromonas strains on the basis of multilocus sequence typing, phenotype, and presence of putative virulence genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 4986–5000. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00708-11

McArthur, A. G., Waglechner, N., Nizam, F., Yan, A., Azad, M. A., Baylay, A. J., et al. (2013). The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 3348–3357. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00419-13

McBain, A. J. (eds). (2009). “Chapter 4 in vitro biofilm models: an overview,” in Advances in Applied Microbiology (Cambridge, MA: Academic Press), 99–132. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(09)69004-3

Minh, B. Q., Nguyen, M. A. T., and von Haeseler, A. (2013). Ultrafast approximation for phylogenetic bootstrap. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 1188–1195. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst024

Nguyen, L.-T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A., and Minh, B. Q. (2015). IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300

O’Toole, G. A. (2011). Microtiter dish biofilm formation assay. J. Vis. Exp. 47:2437. doi: 10.3791/2437

Pieters, N., Brunt, J., Austin, B., and Lyndon, A. R. (2008). Efficacy of in-feed probiotics against Aeromonas bestiarum and Ichthyophthirius multifiliis skin infections in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss, Walbaum). J. Appl. Microbiol. 105, 723–732. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03817.x

Piotrowska, M., and Popowska, M. (2015). Insight into the mobilome of Aeromonas strains. Front. Microbiol. 6:494. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00494

Popoff, M., and Véron, M. (1976). A taxonomic study of the Aeromonas hydrophila-Aeromonas punctata group. Microbiology 94, 11–22. doi: 10.1099/00221287-94-1-11

Prajapati, H. N., Dalrymple, D. M., and Serajuddin, A. T. M. (2012). A comparative evaluation of mono-, Di- and triglyceride of medium chain fatty acids by lipid/surfactant/water phase diagram, solubility determination and dispersion testing for application in pharmaceutical dosage form development. Pharm. Res. 29, 285–305. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0541-3

Pritchard, L., Glover, R. H., Humphris, S., Elphinstone, J. G., and Toth, I. K. (2016). Genomics and taxonomy in diagnostics for food security: soft-rotting enterobacterial plant pathogens. Anal. Methods 8, 12–24. doi: 10.1039/C5AY02550H

Rissman, A. I., Mau, B., Biehl, B. S., Darling, A. E., Glasner, J. D., and Perna, N. T. (2009). Reordering contigs of draft genomes using the Mauve Aligner. Bioinformatics 25, 2071–2073. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp356

Rouli, L., Merhej, V., Fournier, P.-E., and Raoult, D. (2015). The bacterial pangenome as a new tool for analysing pathogenic bacteria. New Microbes New Infect. 7, 72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2015.06.005

Sanglas, A., Albarral, V., Farfán, M., Lorén, J. G., and Fusté, M. C. (2017). Evolutionary roots and diversification of the genus Aeromonas. Front. Microbiol. 8:127. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00127

Schachte, J. H. (2002). Furunculosis. Long Island City, NY: New York Department of Environmental Conservatory.

Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S., and Eliceiri, K. W. (2012). NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089

Schubiger, C. B., Orfe, L. H., Sudheesh, P. S., Cain, K. D., Shah, D. H., and Call, D. R. (2015). Entericidin is required for a probiotic treatment (Enterobacter sp. strain C6-6) to protect trout from cold-water disease challenge. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 658–665. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02965-14

Scott, M. (1968). The pathogenicity of Aeromonas salmonicida (Griffin) in sea and brackish waters. J. Gen. Microbiol. 50, 321–327. doi: 10.1099/00221287-50-2-321

Seemann, T. (2014). Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153

Shao, Y., Harrison, E. M., Bi, D., Tai, C., He, X., Ou, H.-Y., et al. (2011). TADB: a web-based resource for Type 2 toxin–antitoxin loci in bacteria and archaea. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D606–D611. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq908

Suarez, G., Sierra, J. C., Sha, J., Wang, S., Erova, T. E., Fadl, A. A., et al. (2008). Molecular characterization of a functional type VI secretion system from a clinical isolate of Aeromonas hydrophila. Microb. Pathog. 44, 344–361. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2007.10.005

Sugiyama, T., and Itoh, T. (1993). Control of ColE2 DNA replication: in vitro binding of the antisense RNA to the Rep mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 5972–5977. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.25.5972

Talagrand-Reboul, E., Jumas-Bilak, E., and Lamy, B. (2017a). The social life of Aeromonas through biofilm and quorum sensing systems. Front. Microbiol. 8:37. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00037

Talagrand-Reboul, E., Roger, F., Kimper, J.-L., Colston, S. M., Graf, J., Latif-Eugenín, F., et al. (2017b). Delineation of taxonomic species within complex of species: Aeromonas media and related species as a test case. Front. Microbiol. 8:621. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00621

Tam, B. (2009). A Climate Change Impact Assessment on the Spread of Furunculosis in the Ouje-Bougoumou Region. Available at: https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/17227 [accessed September 14, 2017].

Tam, B., Gough, W. A., and Tsuji, L. (2011). The impact of warming on the appearance of furunculosis in fish of the James Bay region, Quebec, Canada. Reg. Environ. Change 11, 123–132. doi: 10.1007/s10113-010-0122-8

Tomizawa, J. (1984). Control of ColE1 plasmid replication: the process of binding of RNA I to the primer transcript. Cell 38, 861–870. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90281-2

Tritt, A., Eisen, J. A., Facciotti, M. T., and Darling, A. E. (2012). An integrated pipeline for de novo assembly of microbial genomes. PLOS ONE 7:e42304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042304

Trudel, M. V., Vincent, A. T., Attéré, S. A., Labbé, M., Derome, N., Culley, A. I., et al. (2016). Diversity of antibiotic-resistance genes in Canadian isolates of Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida: dominance of pSN254b and discovery of pAsa8. Sci. Rep. 6:35617. doi: 10.1038/srep35617

Vanden Bergh, P., and Frey, J. (2013). Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida in the light of its type-three secretion system. Microb. Biotechnol. 7, 381–400. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12091

Vincent, A. T., and Charette, S. J. (2017). Phylogenetic analysis of the fish pathogen Aeromonas salmonicida underlines the dichotomy between European and Canadian strains for the salmonicida subspecies. J. Fish Dis. 40, 1241–1247. doi: 10.1111/jfd.12595

Vincent, A. T., Trudel, M. V., Freschi, L., Nagar, V., Gagné-Thivierge, C., Levesque, R. C., et al. (2016). Increasing genomic diversity and evidence of constrained lifestyle evolution due to insertion sequences in Aeromonas salmonicida. BMC Genomics 17:44. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2381-3

Vincent, A. T., Trudel, M. V., Paquet, V. E., Boyle, B., Tanaka, K. H., Dallaire-Dufresne, S., et al. (2014). Detection of variants of the pRAS3, pAB5S9, and pSN254 plasmids in Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida: multidrug resistance, Interspecies exchanges, and plasmid reshaping. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 7367–7374. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03730-14

Wahli, T., Burr, S. E., Pugovkin, D., Mueller, O., and Frey, J. (2005). Aeromonas sobria, a causative agent of disease in farmed perch, Perca fluviatilis L. J. Fish Dis. 28, 141–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2761.2005.00608.x

Xia, X. (2017). DAMBE6: new tools for microbial genomics, phylogenetics, and molecular evolution. J. Hered. 108, 431–437. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esx033

Yang, L., Li, W., Jiang, G.-Z., Zhang, W.-H., Ding, H.-Z., Liu, Y.-H., et al. (2017). Characterization of a P1-like bacteriophage carrying CTX-M-27 in Salmonella spp. resistant to third generation cephalosporins isolated from pork in China. Sci. Rep. 7:40710. doi: 10.1038/srep40710

Yang, Q.-H., Zhou, C., Lin, Q., Lu, Z., He, L.-B., and Guo, S.-L. (2017). Draft genome sequence of Aeromonas sobria strain 08005, isolated from sick Rana catesbeiana. Genome Announc. 5:e01352-16. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01352-16

Keywords: Aeromonas sobria, host–microbe interactions, bacterial genomics, microbial diversity, molecular systematics

Citation: Gauthier J, Vincent AT, Charette SJ and Derome N (2017) Strong Genomic and Phenotypic Heterogeneity in the Aeromonas sobria Species Complex. Front. Microbiol. 8:2434. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02434

Received: 26 September 2017; Accepted: 23 November 2017;

Published: 08 December 2017.

Edited by:

Jesus L. Romalde, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, SpainReviewed by:

M. Carmen Fuste, University of Barcelona, SpainCopyright © 2017 Gauthier, Vincent, Charette and Derome. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jeff Gauthier, amVmZi5nYXV0aGllci4xQHVsYXZhbC5jYQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.