94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Microbiol., 26 April 2016

Sec. Food Microbiology

Volume 7 - 2016 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00578

This article is part of the Research TopicMicrobiology of Ethnic Fermented Foods and Alcoholic Beverages of the WorldView all 16 articles

Fermented foods have unique functional properties imparting some health benefits to consumers due to presence of functional microorganisms, which possess probiotics properties, antimicrobial, antioxidant, peptide production, etc. Health benefits of some global fermented foods are synthesis of nutrients, prevention of cardiovascular disease, prevention of cancer, gastrointestinal disorders, allergic reactions, diabetes, among others. The present paper is aimed to review the information on some functional properties of the microorganisms associated with fermented foods and beverages, and their health-promoting benefits to consumers.

Existing scientific data show many fermented foods have both nutritive and non-nutritive components in foods, which have the potential to modulate specific target functions in the body relevant to well-being and health of the consumers. However, 90% of naturally fermented foods and alcoholic beverages in different countries and regions of the world are still at home production under traditional conditions. Naturally fermented foods and beverages contain both functional and non-functional microorganisms (Tamang et al., 2016). Functional microorganisms transform the chemical constituents of raw materials of plant/animal sources during food fermentation thereby enhancing the bio-availability of nutrients, enriching sensory quality of the food, imparting bio-preservative effects and improvement of food safety, degrading toxic components and anti-nutritive factors, producing antioxidant and antimicrobial compounds, stimulating the probiotic functions, and fortifying with some health-promoting bioactive compounds (Tamang et al., 2009, 2016; Farhad et al., 2010; Bourdichon et al., 2012; Thapa and Tamang, 2015). Among bacteria associated with fermented foods and alcoholic beverages, lactic acid bacteria (LAB) mostly species of Enterococcus, Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, Pediococcus, Weissella, etc. are widely present in many fermented foods and beverages (Axelsson et al., 2012; Holzapfel and Wood, 2014). Species of Bacillus are also present in legume-based fermented foods (Kubo et al., 2011; Tamang, 2015). Species of Bifidobacterium, Brachybacterium, Brevibacterium, and Propionibacterium are isolated from cheese, and species of Arthrobacter and Hafnia from fermented meat products (Bourdichon et al., 2012). Several genera with hundred of species of yeasts have been isolated from fermented foods, alcoholic beverages and non-food mixed amylolytic starters which mostly include Candida, Debaryomyces, Geotrichum, Hansenula, Kluyveromyces, Pichia, Rhodotorula, Saccharomyces, Saccharomycopsis, Schizosaccharomyces, Torulopsis, Wickerhamomyces, and Zygosaccharomyces (Tamang and Fleet, 2009; Lv et al., 2013). Species of Actinomucor, Amylomyces, Aspergillus, Monascus, Mucor, Neurospora, Penicillium, Rhizopus, and Ustilago are reported for many fermented foods, Asian non-food amylolytic starters, and alcoholic beverages (Chen et al., 2014).

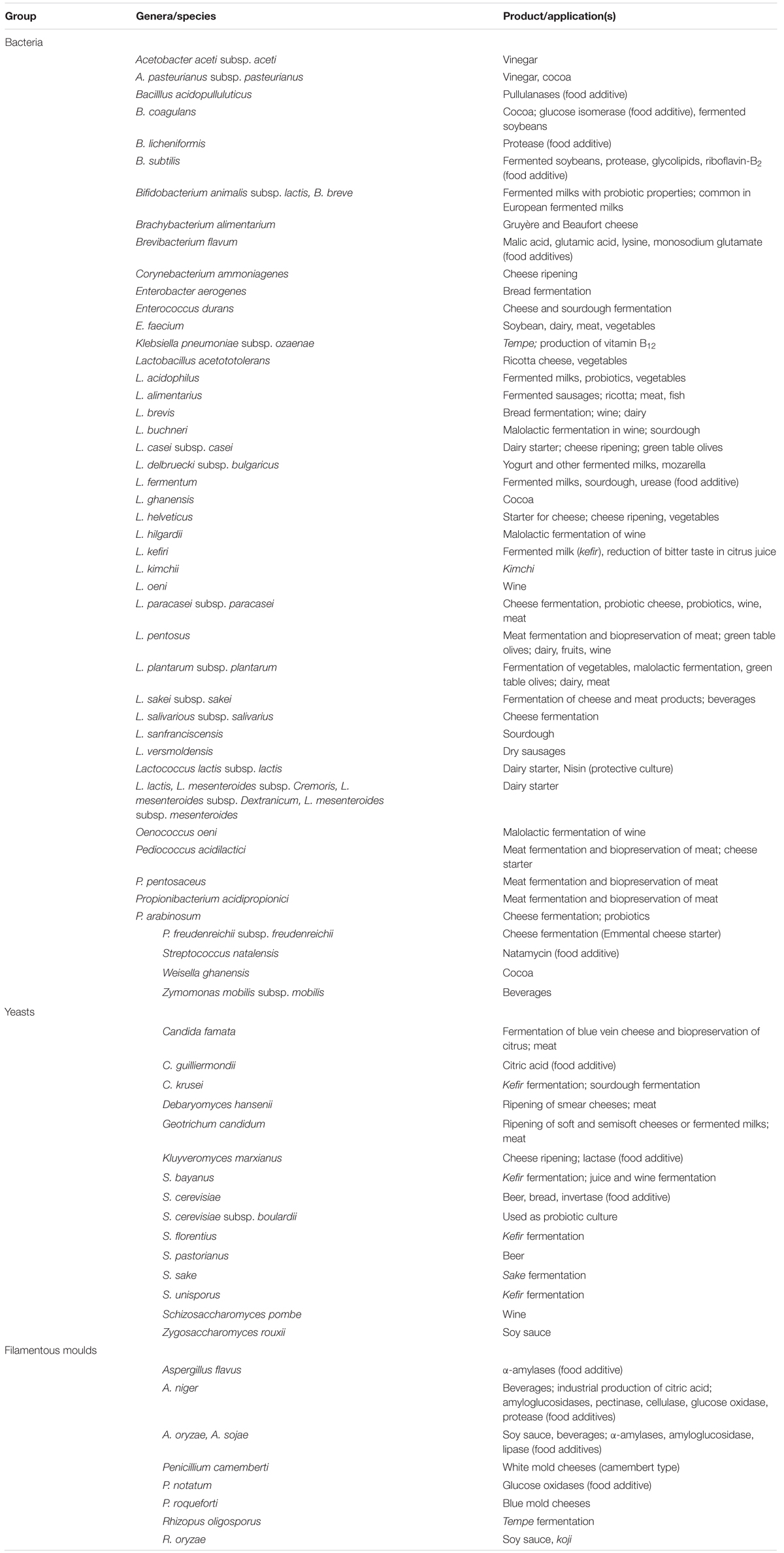

Functional properties of microorganisms in fermented foods include probiotics properties (Hill et al., 2014), antimicrobial properties (Meira et al., 2012), antioxidant (Perna et al., 2013), peptide production (De Mejia and Dia, 2010), fibrinolytic activity (Kotb, 2012), poly-glutamic acid (Chettri and Tamang, 2014), degradation of antinutritive compounds (Babalola, 2014), etc. which may be important criteria for selection of starter culture(s) to be used in the manufacture of functional foods (Badis et al., 2004). Some genera and species of microorganisms are used as commercial starters in food fermentation (Table 1), and some of products are commercialized and marketed globally as functional foods, health foods, therapeutic foods and nutraceuticals foods (Bernardeau et al., 2006; Bourdichon et al., 2012; Thapa and Tamang, 2015). The present paper is aimed to review the information on some functional properties of the microorganisms associated with fermented foods and beverages, and their health-promoting benefits to consumers.

TABLE 1. Some functional microorganisms used as commercial starters in food fermentation (amended and compiled from references: Mogensen et al., 2002; Bernardeau et al., 2006; Bourdichon et al., 2012; Thapa and Tamang, 2015).

Probiotics are defined as live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host (Hill et al., 2014). Probiotic organisms used in foods must have the ability to resist gastric juices, exposure to bile, and be able to proliferate and colonize the digestive tract (Saad et al., 2013). The beneficial effects of probiotic foods on human health and nutrition are constantly increasing (de LeBlanc et al., 2007; Monteagudo-Mera et al., 2012), and probiotics are popularly using bio-ingredients in many functional fermented foods (Chávarri et al., 2010). The most commonly used probiotic bacteria belong to the heterogeneous group of LAB (Lactobacillus, Enterococcus) and to the genus Bifidobacterium, however, yeasts and other microbes have also been developed as potential probiotics during recent years (Ouwehand et al., 2002). Some popular commercial probiotic cultures which are available in global markets include Bacillus coagulans BC30 marketed by Ganeden Biotech, Inc., Cleveland, OH, USA; Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM, Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 (DR20) and Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 (DR10) marketed by Danisco (Madison, WI, USA), L. casei strain Shirota and B. breve strain Yakult marketed by Yakult (Tokyo, Japan), L. fermentum VRI003 (PCC) marketed by Probiomics (Eveleigh, NSW, Australia), L. rhamnosus R0011 marketed by Institut Rosell (Montreal, QC, Canada), Streptococcus oralis KJ3 marketed by Oragenics, Inc. (Alachua, FL, USA), and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (boulardii) marketed by Biocodex (Creswell, OR, USA; US Probiotics Home, 2011).

Products containing probiotic bacteria generally include foods and supplements (Varankovich et al., 2015). Fermented milk products are the most traditional source of probiotic strains of lactobacilli (Bernardeau et al., 2006; Shah, 2015); however, commercial probiotic lactobacilli have also been added to meat products, snacks, fruit juice, etc. (Ranadheera et al., 2010). Probiotic properties of Lactobacillus plantarum isolated from kimchi, Korean fermented vegetable product, has been reported (Ji et al., 2013), and is also found to prevent the growth of Helicobacter pylori (Lim and Im, 2009). Probiotic strain L. acidophilus La-5 produces conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), an anti-carcinogenic agent (Macouzet et al., 2009). Pediococcus pentosaceus CIAL-86 isolated from wine shows anti-adhesion activity against Escherichia coli CIAL-153, indicating its probiotic potential in wine (García-Ruiz et al., 2014).

Many species of LAB isolated from fermented vegetable and milk products have antimicrobial activities due to production of antimicrobial compounds such as bacteriocin and nisin (Tamang et al., 2009; Khan et al., 2010; Gaggia et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2012; Grosu-Tudor and Zamfir, 2013). Many strains of LAB isolated from kimchi produce antimicrobial compounds such as bacteriocin by L. lactis BH5 (Hur et al., 2000) and L. citreum GJ7 (Chang et al., 2008), and pediocin by P. pentosaceus (Shin et al., 2008). Species of LAB isolated from kimchi show strong antimicrobial activity against Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, and Salmonella typhimurium (Lee et al., 2009). Weissella cibaria isolated from fermented cabbage product shows antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens (Patel et al., 2014). Lactococcus lactis isolated from dahi, Indian curd, produces nisin Z that inhibits L. monocytogenes and S. aureus (Mitra et al., 2010). Several LAB species isolated from Romanian traditional fermented fruits and vegetables have antimicrobial activity against L. monocytogenes, E. coli, Salmonella, and Bacillus (Grosu-Tudor and Zamfir, 2013). Microorganisms as protective cultures, e.g., bacteriocin producers, may have several advantages, as they can contribute to the flavor, texture and nutritional value of the product besides the production of bacteriocin (Gaggia et al., 2011).

Antioxidant activities in fermented foods include 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl hydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity, 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzo-thiazoline-6-sulfonic acid; ABTS) radical scavenging activity, total phenol content (TPC) estimation, and reducing power assay (Liu and Pan, 2010; Abubakr et al., 2012). Many Asian fermented soybean foods have antioxidant properties, e.g., natto, Bacillus-fermented soybean food of Japan (Ping et al., 2012), chungkokjang and jang, fermented soybean foods of Korea (Shon et al., 2007; Shin and Jeong, 2015), douchi, a fermented soybean food of China (Wang et al., 2007a), kinema, Bacillus-fermented soybean food of India and Nepal (Moktan et al., 2008; Tamang, 2015), bekang and tungrymbai, Bacillus-fermented soybean foods of India (Chettri and Tamang, 2014), thua nao, Bacillus-fermented soybean food of Thailand (Dajanta et al., 2013), and tempe mold-fermented soybean food of Indonesia (Nurrahman et al., 2013). Antioxidant activities have also been observed in kimchi (Park et al., 2011) and yogurt (Sabeena et al., 2010).

Bioactive peptides are formed during food fermentation by proteolytic microorganisms (De Mejia and Dia, 2010). In fermented foods peptides have some functional properties such as immunomodulatory (Qian et al., 2011), antithrombic (Singh et al., 2014), and antihypertensive properties (Phelan and Kerins, 2011). Species of Bacillus are involved in enzymatic hydrolysis of protein producing peptides and amino acids, which claim to have health benefits (Nagai and Tamang, 2010). Inhibitory properties of Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) have been studied in various fermented milk products such as kefir (Quiros et al., 2005), koumiss (Chen et al., 2010), yogurt (Papadimitriou et al., 2007), fermented camel milk (Moslehishad et al., 2013), cheese (Meyer et al., 2009), and fermented fish products (Ichimura et al., 2003).

Another important reason to ferment foods is to coax microorganisms into producing enzymes that also provide very useful services. During food fermentation microorganisms produce enzymes to break down complex compounds to simple bio-molecules for several biological activities such as proteinase, amylase, mannase, cellulase, and catalase in many Asian fermented soybean foods by Bacillus spp. (Tamang and Nikkuni, 1996; Chettri and Tamang, 2014). Common genera of mycelial fungi in fermented foods and beverages such as Actinomucor, Amylomyces, Aspergillus, Monascus, Mucor, Neurospora, and Rhizopus produce various carbohydrases such as α- amylase, amyloglucosidase, maltase, invertase, pectinase, ß-galactosidase, cellulase, hemi-cellulase; acid and alkaline proteases; and lipases (Nout and Aidoo, 2002). Taka-amylase A (TAA), an enzyme produced by Aspergillus oryzae in koji has many uses in industry (Suganuma et al., 2007). Dry, solid, cake-like mixed amylolytic starters used for alcohol production in the Himalayas have yeasts Saccharomycopsis fibuligera, S. capsularis and Pichia burtonii with high amylase activities (Tsuyoshi et al., 2005; Tamang et al., 2007).

Bacillus subtilis subsp. natto in natto produces nattokinase showing fibrinolytic activity (Mine et al., 2005; Kotb, 2012). Among bacteria isolated from fermented foods, B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens (Chang et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2013; Singh et al., 2014), Vagococcus carniphilus, V. lutrae, Enterococcus faecalis, E. faecium, E. gallinarum, and P. acidilactici (Singh et al., 2014), and Virgibacillus halodenitrificans SK1-3-7 isolated from fish sauce fermentation (Montriwong et al., 2012) produce fibrinolytic enzymes.

Isoflavones are daidzein, genistein and glycitein, each of which exists in four chemical forms viz., aglycones, β-glucoside, acetylglucoside, and malonylglucoside in soybeans (Kudou et al., 1991). Isoflavone glucosides are hydrolyzed into their corresponding aglycones during fermentation of some Asian fermented soybean foods such as sufu and douchi of China (Wang et al., 2007b; Yin et al., 2007), miso and natto of Japan (Chiou and Cheng, 2001), chungkokjang and doenjang of Korea (Lee et al., 2007), tempe of Indonesia (Lu et al., 2009), and thua nao of Thailand (Dajanta et al., 2009). During tempe fermentation, isoflavone particularly Factor-II and aglycone contents are found to increase (Nakajima et al., 2005). Isoflavones in doenjang increase the activation of an LDL-C receptor, which is beneficial to prevent vascular diseases (Kwak et al., 2012).

Soybean saponins, which are oleanane triterpenoid glycosides, are again of two types viz., Group A and DDMP (2,3-dihydro-2,5-dihydroxy-6-metyl-4H-pyran-4-one; Paucar-Menacho et al., 2010). DDMP and their derivatives, Groups B and E saponins show health promoting benefits such as prevention of hypercholesterolemia (Murata et al., 2006), suppression of colon cancer cell proliferation (Ellington et al., 2006), and anti-peroxidation of lipids (Ishii and Tanizawa, 2006). Saponin contents are increased in natto, which are generated by Bacillus natto (Yanagisawa and Sumi, 2005). Kinema has high content of Group B saponin, which may indicate its health-promoting benefits to consumers (Omizu et al., 2011).

Poly-glutamic acid (PGA) is not synthesized by ribosomal proteins (Oppermann-Sanio and Steinbüchel, 2002), but is produced by some strains of Bacillus spp. in fermented soybean foods of Asia (Urushibata et al., 2002; Meerak et al., 2007; Nishito et al., 2010; Chettri and Tamang, 2014). B. subtilis and B. licheniformis are widely used industrial producers of γ-PGA (Stanley and Lazazzera, 2005). It is safe eating the viscous materials of Asian fermented soybean foods since PGA is completely biodegradable and water-soluble and non-toxic to human (Yoon et al., 2000).

Some microorganisms present in fermented foods may degrade anti-nutritive substances and thereby convert the substrates into consumable products (Nout, 1994; Tamang, 2015). Various steps employed during the processing of gari and fufu, fermented cassava products of Africa, such as peeling, washing, grating, fermentation, dewatering and roasting minimizes the residual cyanide contents of the product (Babalola, 2014). Bitter varieties of cassava tubers contain the cyanogenic glycoside linamarin and lotaustralin, which are detoxified by species of Leuconostoc, Lactobacillus, and Streptococcus during traditional method to gari and fufu productions to yield hydrocyanic acid (HCN) which has low boiling point and escapes from the dewatered pulp during toasting rendering the product safe for human consumption (Lambri et al., 2013; Babalola, 2014; Bamidele et al., 2015). In tempe, Rhizopus oligosporus eliminates the flatulence causing indigestible oligosaccharides such as stachyose and verbascose into the absorbable monosaccharides and disaccharides (Hesseltine, 1983; Sanchez, 2008). Degradation of anti-nutritive compounds by B. subtilis has been reported in kinema (Sarkar et al., 1997). Phytic acid is reduced during fermentation of idli (Reddy and Salunkhe, 1980) and rabadi, a fermented cereal food of India (Gupta et al., 1992).

Ethnic foods have in-built systems both as foods and medicine to meet up hungry and also curative (Shin and Jeong, 2015; Thapa and Tamang, 2015). The highest longevity observed among the people of Okinawa prefecture in Japan is mostly due to their traditional and cultural foods such as natto, miso, tofu, shoyu, fermented vegetables, cholesterol-free, low-fat, and high bioactive-compounded foods in addition to active physical activity, sound environment, happiness and other several factors (Willcox et al., 2004). Korean kimchi has been claimed to possess health-promoting benefits (Cheigh, 1999; Lee et al., 2011; Park et al., 2014; Han et al., 2015). Kimchi has also anti-aging effect (Kim et al., 2002). Natto has several health benefits such as high contents of nattokinase, isoflavones, saponins, vitamin K, unsaturated fatty acids, probiotics and immunomodulating activities mostly produced by B. subtilis (natto; Tsubura, 2012; Nagai, 2015). Kinema has also some health promoting benefits (Omizu et al., 2011; Tamang, 2015). Indian popular fermented milk dahi has anti-carcinogenic property (Arvind et al., 2010). Lactic acid produced in kimchi may prevent fat accumulation and to improve obesity-induced heart diseases (Park et al., 2008). Anti-obesity effects have been reported in kimchi (Kim et al., 2011; Park et al., 2012) and in doenjang (Kwak et al., 2012) based on clinical trials (Cha et al., 2012; Jung et al., 2014). Red wine has anti-aging property due to presence of melatonin that regulates the body clock (Corder et al., 2006; Walker, 2014).

Ethnic people have customary belief in medicinal values of some of their ethnic foods including fermented foods and beverages, however, clinical trials and validation of the health benefits claims of almost all naturally fermented foods and beverages of the world need to be studied. Some health benefits of fermented foods are listed in Table 2.

Enrichment of substrates with vitamins, essential amino acids, and bioactive compounds occur during food fermentation (Holzapfel et al., 1995; Steinkraus, 1996; Thapa and Tamang, 2015). In tempe, mold-fermented soybean food of Indonesia, contents of folic acid, niacin, riboflavin, nicotinamide and pyridoxine are found to be increased by Rhizopus oligosporus (Astuti, 2015), whereas vitamin B12 is synthesized by non-pathogenic strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Citrobacter freundii (Liem et al., 1977; Okada, 1989; Keuth and Bisping, 1994). Contents of thiamine, riboflavin and methionine in idli, a rice-legume based fermented food of India and Sri Lanka enhance during fermentation (Ghosh and Chattopadhyay, 2011). Similarly, vitamins B complex and C, lysine and tryptophane, and iron contents have been found to increase during fermentation of pulque, an alcoholic drink of Mexico made from cactus plant (Ramirez et al., 2004). Riboflavin and niacin contents are increased in many Bacillus-fermented Asian fermented foods (Sarkar et al., 1998; Kim and Hahm, 2002; Nagai, 2015). Riboflavin and folic acid were found to be synthesized in kimchi by L. mesenteroides and L. sakei (Jung et al., 2013). Yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida tropicalis, Aureobasidium sp., and Pichia manschuria isolated from idli and jalebi, fermented cereal foods of India and Pakistan produce vitamin B12 (Syal and Vohra, 2013). Free amino acids are increased in fermented soybean foods (Nikkuni et al., 1995; Sarkar and Tamang, 1995; Tamang and Nikkuni, 1998; Kiers et al., 2000; Dajanta et al., 2011).

Antihypertensive properties of many fermented milk products have been validated using animal models and clinical trials (Seppo et al., 2002; Sipola et al., 2002). Consumption of fermented milks or probiotic bacteria (Agerholm-Larsen et al., 2000) and fermented soybean foods (Liu and Pan, 2010) lowers the risk of heart diseases. Fermented whole grain foods can lower the serum LDL-cholesterol values, hypertriacylglycerolaemia, hypertension, coronary heart disease, insulin resistance, and hyperhomocysteinaemia (Anderson, 2003). Consumption of some fermented foods reduces the cholesterol level in tempe (Hermosilla et al., 1993), fermented soybean foods (Lee, 2004), and kefir (Otes and Cagindi, 2003). Calpis, the Japanese fermented sour milk containing two peptides VPP and IPP has shown hypotensive effect (Nakamura et al., 1996). L. helvetius in fermented milk reduces elevated blood pressure (Aihara et al., 2005; Shah, 2015). Monascus purpureus in fermented red-rice of China locally called angkak, prohibits creation of cholesterol by blocking a key enzyme, HMG-CoA reductase due to presence of mevinolin citrinin (Pattanagul et al., 2008).

Drinking of fermented tea of China prevents heart disease (Mo et al., 2008). Some Asian fermented soybean foods have antihypertensive properties as observed in natto (Nagai, 2015) and tempe (Astuti, 2015). Isoflavone in doenjang, mold-fermented soybean food of Korea, plays an important role in preventing cardiovascular diseases (Kwak et al., 2012; Shin et al., 2015). Fermented whole-grain intake appears to protect from development of heart disease and diabetes (Anderson, 2003). Moderate consumption of wine is healthier (Walker, 2014). Polyphenols in red wine probably are synergists of the tocopherol (Vitamin E) and ascorbic acid (Vitamin C), thus they inhibit lipid peroxidation (Feher et al., 2007). Regular consumption of the Korean fermented soybean foods by hypertensive and Type 2 diabetic patients results in favorable changes in cardiovascular risk factors (Jung et al., 2014) and reduction of hypocholesterolemic effect (Lim et al., 2014). ACEs inhibitory peptides derived from food proteins are used for treating hypertension (Jakubczyk et al., 2013). Fermented foods, which are rich in fibrinolytic enzymes, are useful for thrombolytic therapy to prevent rapidly emerging heart diseases (Mine et al., 2005; Singh et al., 2014).

Some LAB-fermented foods have antimutagenic and anticarcinogeinc activities (Lee et al., 2004). Kefir is used for the treatment of cancer (Otes and Cagindi, 2003; Yanping et al., 2009). Sauerkraut, fermented vegetable of Germany, contains s-methylmethionine, which reduces tumourigenesis risk in the stomach (Kris-Etherton et al., 2002). Consumption of fermented milk products containing live cells of L. acidophilus decreases ß-glucuronidase, azoreductase, and nitroreductase (catalyze conversion of procarcinogens to carcinogens), probably removes procarcinogens, and activate the immune system of consumers (Goldin and Gorbach, 1984; Macouzet et al., 2009). Similarly, Indian dahi has anti-carcinogenic property (Mohania et al., 2013). Cancer preventive potential of W. cibaria, and L. plantarum has been reported in kimchi (Kwak et al., 2014). Consumption of yogurt can reduce bladder, colon and cervical cancer has been observed (Chandan and Kilara, 2013).

Lactic acid bacteria present in fermented foods may decrease number of incidence, duration and severity of some gastrointestinal disorders (Verna and Lucak, 2010). Administration of some strains of Lactobacillus improves the inflammatory bowel disease, paucities and ulcerative colitis (Orel and Trop, 2014). L. rhamnosus GG is effective in the treatment of acute diarrhea (Szajewska et al., 2007) and administration of L. helveticus-fermented milk in healthy older adults produced improvements in cognition function (Chung et al., 2014). Consumption of fermented milk products containing live bacteria has immunomodulation capacity (Granier et al., 2013), and cures diarrhea (Balamurugan et al., 2014). Korean kimchi is suitable for control of inflammatory bowel diseases (Lim et al., 2011).

Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens M1 isolated from kefir grains has an anti-allergic effect (Hong et al., 2010). Digestion of caseins during maturation of fermented milk products has shown to facilitate loss of allergenic reactivity thus increases tolerance (Alessandri et al., 2012). Chongkokjang has anti-allergic effect such as dermis thickness, decreased ear thickness, auricular lymph node and infiltrating mast cells (Lee et al., 2014). Lactobacillus species isolated from kimchi are found to modulate Th1/Th2 balance by producing a large amount of IL-12 and IFN-γ with ability to alleviate atopic dermatitis and food allergy (Won et al., 2011). Fermented fish oil, which is rich with Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, can reduce sensitization of allergy (Han et al., 2012).

Intake of high fiber foods may decrease the insulin requirements in diabetic persons (Meyer et al., 2000), and may increase the sensitivity to insulin for non-diabetic persons (Fukagawa et al., 1990; Anderson, 2003). Probiotic dahi-supplemented diet significantly delays the glucose intolerance, hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, oxidative stress and dyslipidemia indicating a lower risk of diabetes (Yadav et al., 2007). Daily consumption of chungkokjang may increase the insulin resistivity thus controls diabetics (Shin et al., 2011; Tolhurst et al., 2012).

Vitamin K2 present in natto stimulates the formation of bone, which may help to prevent osteoporosis in older women in Japan (Yanagisawa and Sumi, 2005). Mineral such magnesium, calcium, phosphorus, potassium, and also protein present in yogurt may function together to promote formation of healthy bones (Chandan and Kilara, 2013).

Some people suffer from lactose malabsorption, a condition in which lactose, the principal carbohydrate of milk, is not completely digested into glucose and galactose due to lack of ß-D-galactosidase (Shah, 2015). L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus used in production of yogurt contain substantial quantities of ß-D-galactosidase which improve the symptoms of lactose malabsorption in lactose intolerant people (Shah et al., 2013). Consumption of fresh yogurt (with live yogurt cultures) has been demonstrated better lactose digestion and absorption than with the consumption of a pasteurized product (Pedone et al., 2000). Kefir can minimize the symptoms of lactose intolerance by providing extra source of β-galactosidase (Hertzler and Clancy, 2003).

One of the important health risks in fermented foods is presence of biogenic amines. Biogenic amines are low molecular weight organic compounds by microbial decarboxylation of their precursor amino acids or by transamination of aldehydes and ketones by amino acid transaminases (Zhai et al., 2012), which are are present in some fermented foods such as sauerkraut, fish products, cheese, wine, beer, dry sausages, etc. (Halász et al., 1994; Suzzi and Gardini, 2003; Spano et al., 2010; Visciano et al., 2014). Enterobacteriaceae and enterococci are major biogenic amine producers in foods (Nout, 1994). Foods with high levels of biogenic amines could be considered as unhealthy (Latorre-Moratalla et al., 2010). High levels (>100 mg/kg) of histamine and tyramine can cause adverse effects to human health (Rauscher-Gabernig et al., 2009). Fermentation of cabbage with certain lactic starters such as L. casei subsp. casei, L. plantarum and L. curvatus could reduce the biogenic amine content of sauerkraut (Rabie et al., 2011). The ingestion of food containing small amounts of histamine has little effect in healthy individuals, but it can result in histamine intolerance in persons characterized by impairment of diamine oxidase activity, either due to genetic predisposition, gastrointestinal diseases, or medication with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (Maintz and Novak, 2007). A maximum limit of 100 mg/kg of histamine in food indicates a safe level for consumption (Halász et al., 1994).

Some fermented foods and beverages have health benefits due to presence of functional microorganisms. Although, some fermented foods and beverages are marketed globally as health foods, functional foods, therapeutic foods, nutraceutical foods, bio-foods, however, due to urbanization, changes in life-style, and the shifting from traditional food habits to commercial fast foods, the production and consumption of traditional fermented foods is in decline mostly in Asia and Africa. Reliance on fewer providers of fermented foods is also leading to a decline in the biodiversity of microorganisms. We recommend that validation of health claims by clinical trials and animal models of some common fermented foods of the world may be studied in details, and also introduction of new fermented food products containing well-validated functional microorganism(s) may emerge in global food market.

JPT (70% – data collection, analysis, writing), D-HS (10% – data collection), S-JJ (10% – data collection) and S-WC (10% – data collection).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abubakr, M. A. S., Hassan, Z., Imdakim, M. M. A., and Sharifah, N. R. S. (2012). Antioxidant activity of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) fermented skim milk as determined by 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and ferrous chelating activity (FCA). Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 6, 6358–6364.

Agerholm-Larsen, L., Bell, M. L., Grunwald, G. K., and Astrup, A. (2000). The effect of probiotic milk product on plasma cholesterol: a meta-analysis of short-term intervention studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 54, 856–860.

Aihara, K., Kajimoto, O., Hirata, H., Takahashi, R., and Nakamura, Y. (2005). Effect of powdered fermented milk with Lactobacillus helveticus on subjects with high-normal blood pressure or mild hypertension. J. Am. Col. Nutri. 24, 257–265.

Alessandri, C., Sforza, S., Palazzo, F., Lambertini, S., Paolella, D., Zennaro, C., et al. (2012). Tolerability of a fully maturated cheese in cow’s milk allergic children: biochemical, immunochemical, and clinical aspects. PLoS ONE 7:e40945.

Anderson, J. W. (2003). Whole grains protect against atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Proc. Nutri. Soc. 62, 135–142. doi: 10.1079/PNS2002222

Arvind, K., Nikhlesh, K. S., and Pushpalata, R. S. (2010). Inhibition of 1,2-dimethylhydrazine induced colon genotoxicity in rats by the administration of probiotic curd. Mol. Biol. Rep. 37, 1373–1376. doi: 10.1007/s11033-009-9519-1

Astuti, M. (2015). “Health benefits of tempe,” in Health Benefits of Fermented Foods, ed. J. P. Tamang (New York, NY: CRC Press), 371–394.

Axelsson, L., Rud, I., Naterstad, K., Blom, H., Renckens, B., Boekhorst, J., et al. (2012). Genome sequence of the naturally plasmid-free Lactobacillus plantarum strain NC8 (CCUG 61730). J. Bacteriol. 194, 2391–2392. doi: 10.1128/JB.00141-12

Babalola, O. O. (2014). Cyanide content of commercial gari from different areas of Ekiti State, Nigeria. World J. Nutri. Health 2, 58–60.

Badis, A., Guetarni, D., Moussa-Boudjemaa, B., Henni, D. E., Tornadijo, M. E., and Kihal, M. (2004). Identification of cultivable lactic acid bacteria isolated from Algerian raw goat’s milk and evaluation of their technological properties. Food Microbiol. 21, 343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2003.11.006

Balamurugan, R., Chandragunasekaran, A. S., Chellappan, G., Rajaram, K., Ramamoorthi, G., and Ramakrishna, B. S. (2014). Probiotic potential of lactic acid bacteria present in home made curd in Southern India. Indian J. Med. Res. 140, 345–355.

Bamidele, O. P., Fasogbon, M. B., Oladiran, D. A., and Akande, E. O. (2015). Nutritional composition of fufu analog flour produced from Cassava root (Manihot esculenta) and Cocoyam (Colocasia esculenta) tuber. Food Sci. Nutr. 3, 597–603. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.250

Bernardeau, M., Guguen, M., and Vernoux, J. P. (2006). Beneficial lactobacilli in food and feed: long-term use, biodiversity and proposals for specific and realistic safety assessments. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30, 487–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00020.x

Bourdichon, F., Casaregola, S., Farrokh, C., Frisvad, J. C., Gerds, M. L., Hammes, W. P., et al. (2012). Food fermentations: microorganisms with technological beneficial use. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 154, 87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.12.030

Cha, Y. S., Yang, J. A., Back, H. I., Kim, S. R., Kim, M. G., Jung, S. J., et al. (2012). Visceral fat and body weight are reduced in overweight adults by the supplementation of Doenjang, a fermented soybean paste. Nutri. Res. Pract. 6, 520–526.

Chandan, R. C., and Kilara, A. (2013). Manufacturing Yogurt and Fermented Milks, 2nd Edn. (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons), 477.

Chang, C. T., Wang, P. M., Hung, Y. F., and Chung, Y. C. (2012). Purification and biochemical properties of a fibrinolytic enzyme from Bacillus subtilis – fermented red bean. Food Chem. 133, 1611–1617.

Chang, J. Y., Lee, H. J., and Chang, H. C. (2008). Identification of the agent from Lactobacillus plantarum KFRI464 that enhances bacteriocin production by Leuconostoc citreum GJ7. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103, 2504–2515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03543.x

Chávarri, M., Marañón, I., Ares, R., Ibáñez, F. C., Marzo, F., and Villarán, M. C. (2010). Microencapsulation of a probiotic and prebiotic in alginate-chitosan capsules improves survival in simulated gastro-intestinal conditions. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 142, 185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.06.022

Cheigh, H. (1999). Production, characteristics and health functions of kimchi. Acta Horticult. 483, 405–420. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.1999.483.47

Chen, B., Wu, Q., and Xu, Y. (2014). Filamentous fungal diversity and community structure associated with the solid state fermentation of Chinese Maotai-flavor liquor. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 179, 80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.03.011

Chen, Y., Wang, Z., Chen, X., Liu, Y., Zhang, H., and Sun, T. (2010). Identification of angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from koumiss, a traditional fermented mare’s milk. J. Dairy Sci. 93, 884–892.

Chettri, R., and Tamang, J. P. (2014). Functional properties of tungrymbai and bekang, naturally fermented soybean foods of North East India. Int. J. Fer. Foods 3, 87–103. doi: 10.5958/2321-712X.2014.01311.8

Chiou, R. Y. Y., and Cheng, S. L. (2001). Isoflavone transformation during soybean koji preparation and subsequent miso fermentation supplemented with ethanol and NaCl. J. Agric. Food Chem. 49, 3656–3660. doi: 10.1021/jf001524l

Chung, Y. C., Jin, H. M., Cui, Y., Kim, D. S., Jung, J. M., Park, J. I., et al. (2014). Fermented milk of Lactobacillus helveticus IDCC3801 improves cognitive functioning during cognitive fatigue tests in healthy older adults. J. Funct. Foods 10, 465–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.07.007

Corder, R., Mullen, W., Khan, N. Q., Marks, S. C., Wood, E. G., Carrier, M. J., et al. (2006). Oenology: red wine procyanidins and vascular health. Nature 444:566.

Dajanta, K., Apichartsrangkoon, A., Chukeatirote, E., Richard, A., and Frazier, R. A. (2011). Free-amino acid profiles of thua nao, a Thai fermented soybean. Food Chem. 125, 342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.09.002

Dajanta, K., Chukeatirote, E., Apichartsrangkoon, A., and Frazier, R. A. (2009). Enhanced aglycone production of fermented soybean products by Bacillus species. Acta Biol. Szeged. 53, 93–98.

Dajanta, K., Janpum, P., and Leksing, W. (2013). Antioxidant capacities, total phenolics and flavonoids in black and yellow soybeans fermented by Bacillus subtilis: a comparative study of Thai fermented soybeans (thua nao). Int. Food Res. J. 20, 3125–3132.

de LeBlanc, A. M., Matar, C., and Perdigón, G. (2007). The application of probiotics in cancer. Br. J. Nutri. 98, S105–S110. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507839602

De Mejia, E. G., and Dia, V. P. (2010). The role of nutraceutical proteins and peptides in apoptosis, angiogenesis, and metastasis of cancer cells. Cancer Metast. 29, 511–528. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9241-4

Ellington, A. A., Berhow, M. A., and Singletary, K. W. (2006). Inhibition of Akt singaling and enhanced ERK1/2 activity are involved in induction of macroautophagy by triterpenoid B-group soyasaponins in colon cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 27, 298–306. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi214

Farhad, M., Kailasapathy, K., and Tamang, J. P. (2010). “Health aspects of fermented foods,” in Fermented Foods and Beverages of the World, eds J. P. Tamang and K. Kailasapathy (New York, NY: CRC Press), 391–414.

Feher, J., Lengyel, G., and Lugasi, A. (2007). The cultural history of wine - theoretical background to wine therapy. Central Eur. J. Med. 2, 379–391.

Fernández-Mar, M. I., Mateos, R., García-Parrilla, M. C., Puertas, B., and Cantos-Villar, E. (2012). Bioactive compounds in wine: Resveratrol, hydroxytyrosol and melatonin: a review. Food Chem. 130, 797–813.

Ferruzzi, M. G., and Blakeslee, J. (2007). Digestion, absorption, and cancer preventative activity of dietary chlorophyll derivatives. Nutr. Res. 27, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2006.12.003

Fukagawa, N. K., Anderson, J., Young, V. R., and Minaker, K. L. (1990). High-carbohydrate, high-fiber diets increase peripheral insulin sensitivity in healthy young and old adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutri. 52, 524–528.

Gaggia, F., Di Gioia, D., Baffoni, L., and Biavati, B. (2011). The role of protective and probiotic cultures in food and feed and their impact in food safety. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 22, 58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2011.03.003

García-Ruiz, A., Esteban-Fernández, D. G. A., Requena, T., Bartolomé, B., and Moreno-Arribas, M. V. (2014). Assessment of probiotics properties in lactic acid bacteria isolated from wine. Food Microbiol. 44, 220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2014.06.015

Ghosh, D., and Chattopadhyay, P. (2011). Preparation of idli batter, its properties and nutritional improvement during fermentation. J. Food Sci. Technol. 48, 610–615. doi: 10.1007/s13197-010-0148-4

Goldin, B. R., and Gorbach, S. L. (1984). The effect of milk and lactobacillus feeding on human intestinal bacterial enzyme activity. American. J. Clin. Nutri. 39, 756–761.

Granier, A., Goulet, O., and Hoarau, C. (2013). Fermentation products: immunological effects on human and animal models. Pediatr. Res. 74, 238–244. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.76

Grosu-Tudor, S. S., and Zamfir, M. (2013). Functional properties of LAB isolated from Romanian fermented vegetables. Food Biotechnol. 27, 235–248. doi: 10.1080/08905436.2013.811082

Gupta, M., Khetarpaul, N., and Chauhan, B. M. (1992). Rabadi fermentation of wheat: changes in phytic acid content and in vitro digestibility. Plant Foods Hum. Nutri. 42, 109–116. doi: 10.1007/BF02196463

Halász, A., Baráth, A., Simon-Sarkadi, L., and Holzapfel, W. H. (1994). Biogenic amines and their production by microorganisms in food. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 5, 42–49. doi: 10.1016/0924-2244(94)90070-1

Han, E. S., Kim, H. J., and Choi, H. K. (2015). “Health benefits of Kimchi,” in Health Benefits of Fermented Foods, ed. J. P. Tamang (New York: CRC Press), 343–370.

Han, S., Kang, G., Ko, Y., Kang, H., Moon, S., Ann, Y., et al. (2012). Fermented fish oil suppresses T helper 1/2 cell response in a mouse model of atopic dermatitis via generation of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells. BMC Immunol 13:44.

Hermosilla, J. A. G., Jha, H. C., Egge, H., and Mahmud, M. (1993). Isolation and characterization of hydroxymethylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors from fermented soybean extracts. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutri. 15, 163–174. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.15.163

Hertzler, S. R., and Clancy, S. M. (2003). Kefir improves lactose digestion and tolerance in adults with lactose maldigestion. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 103, 582–587. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50111

Hesseltine, C. W. (1983). Microbiology of oriental fermented foods. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 37, 575–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.37.100183.003043

Hill, C., Guarner, F., Reid, G., Gibson, G. R., Merenstein, D. J., Pot, B., et al. (2014). Expert consensus document: the international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 506–514. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66

Holzapfel, W. H., Giesen, R., and Schillinger, U. (1995). Biological preservation of foods with reference to protective cultures, bacteriocins and food-grade enzymes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 24, 343–362. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(94)00036-6

Holzapfel, W. H., and Wood, B. J. B. (2014). Lactic Acid Bacteria: Biodiversity and Taxonomy. (New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell), 632.

Hong, W., Chen, Y., and Chen, M. (2010). The antiallergic effect of kefir Lactobacilli. J. Food Sci. 75, H244–H253.

Hur, J. W., Hyun, H. H., Pyun, Y. R., Kim, T. S., Yeo, I. H., and Park, H. D. (2000). Identification and partial characterization of lacticin bh5, a bacteriocin produced by Lactococcus lactis BH5 isolated from Kimchi. J. Food Protect. 63, 1707–1712.

Ichimura, T., Hu, J., Aita, D. O., and Maruyama, S. (2003). Angiotensin I-Converting enzyme inhibitory activity and insulin secretion stimulative activity of fermented fish sauce. J. Biosci. Bioengineer. 96, 496–499. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(03)70138-8

Ishii, Y., and Tanizawa, H. (2006). Effects of soyasaponins on lipid peroxidation through the secretion of thyroid hormones. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 29, 1759–1763. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1759

Jackson, R. S. (2008). Wine Science: Principles and Applications, 3rd Edn. London: Academic Press, 686–706.

Jakubczyk, A., Karaś, M., Baraniak, B., and Pietrzak, M. (2013). The impact of fermentation and in vitro digestion on formation angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptides from pea proteins. Food Chem. 141, 3774–3780. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.095

Jeong, J., Junga, H., Leea, S., Leea, H., Hwanga, K. T., and Kimb, T. (2010). Anti-oxidant, anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory activities of the extracts from black raspberry fruits and wine. Food Chem. 123, 338–344.

Ji, Y., Kim, H., Park, H., Lee, J., Lee, H., Shin, H., et al. (2013). Functionality and safety of lactic bacterial strains from Korean kimchi. Food Control 31, 467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.10.034

Jiang, J., Shi, B., Zhu, D., Cai, Q., Chen, Y., Li, J., et al. (2012). Characterization of a novel bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus sakei LSJ618 isolated from traditional Chinese fermented radish. Food Control 23, 338–344.

Jung, J. Y., Lee, S. H., Jin, H. M., Hahn, Y., Madsen, E. L., and Jeon, C. O. (2013). Metatranscriptomic analysis of lactic acid bacterial gene expression during kimchi fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 163, 171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.02.022

Jung, S. J., Park, S. H., Choi, E. K., Cha, Y. S., Cho, B. H., Kim, Y. G., et al. (2014). Beneficial effects of Korean traditional diets in hypertensive and Type 2 diabetic patients. J. Med. Food 17, 161–171. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2013.3042

Keuth, S., and Bisping, B. (1994). Vitamin B12 production by Citrobacter freundii or Klebsiella pneumoniae during tempeh fermentation a proof of enterotoxin absence by PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 1495–1499.

Khan, H., Flint, S., and Yu, P. L. (2010). Enterocins in food preservation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 141, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.03.005

Kiers, J. L., Van laeken, A. E. A., Rombouts, F. M., and Nout, M. J. R. (2000). In vitro digestibility of Bacillus fermented soya bean. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 60, 163–169.

Kim, E. K., An, S. Y., Lee, M. S., Kim, T. H., Lee, H. K., Hwang, W. S., et al. (2011). Fermented kimchi reduces body weight and improves metabolic parameters in overweight and obese patients. Nutri. Res. 31, 436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.05.011

Kim, H. J., Lee, J. S., Chung, H. Y., Song, S. H., Suh, H., Noh, J. S., et al. (2007). 3-(4′-Hydroxyl-3′, 5′-dimethoxyphenyl) propionic acid, an active principle of kimchi, inhibits development of atherosclerosis in rabbits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 55, 10486–10492. doi: 10.1021/jf072454m

Kim, J. H., Ryu, J. D., and Song, Y. O. (2002). The effect of kimchi intake on free radical production and the inhibition of oxidation in young adults and the elderly people. Korean J. Commun. Nutri. 7, 257–265.

Kim, K. Y., and Hahm, Y. T. (2002). Recent studies about physiological functions of Chungkkokjang and Functional enhancement with genetic engineering. Instit. Mol. Biol. Genet. 16, 1–18.

Kotb, E. (ed.). (2012). “Springer briefs microbiol,” in Fibrinolytic Bacterial Enzymes with Thrombolytic Activity (Berlin: Springer).

Kris-Etherton, P. M., Hecker, K. D., Bonanome, A., Coval, S. M., Binkoski, A. E., Hilpert, K. F., et al. (2002). Bioactive compounds in foods: their role in the prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Am. J. Med. 113, 71S–88S. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00995-0

Kubo, Y., Rooney, A. P., Tsukakoshi, Y., Nakagawa, R., Hasegawa, H., and Kimura, K. (2011). Phylogenetic analysis of Bacillus subtilis strains applicable to natto (fermented soybean) production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 6463–6469. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00448-11

Kudou, S., Fleury, Y., Welti, D., Magnolato, D., Uchida, T., Kitamura, K., et al. (1991). Malonyl isoflavone glycosides in soybean seeds (Glycine max Merrill). Agric. Biol. Chem. 55, 2227–2233. doi: 10.1271/bbb1961.55.2227

Kwak, C. S., Park, S., and Song, K. Y. (2012). Doenjang, a fermented soybean paste, decreased visceral fat accumulation and adipocyte size in rats fed with high fat diet more effectively than nonfermented soybeans. J. Med. Food 15, 1–9. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2010.1224

Kwak, S. H., Cho, Y. M., Noh, G. M., and Om, A. S. (2014). Cancer preventive potential of Kimchi lactic acid bacteria (Weissella cibaria, Lactobacillus plantarum). J. Cancer Prevent. 19, 253–258. doi: 10.15430/JCP.2014.19.4.253

Lambri, M., Fumi, M. D., Roda, A., and de Faveri, D. (2013). Improved processing methods to reduce the total cyanide content of cassava roots from Burundi. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 12, 2685–2691.

Latorre-Moratalla, M. L., Bover-Cid, S., Talon, R., Garriga, M., Aymerich, T., Zanardi, E., et al. (2010). Strategies to reduce biogenic amine accumulation in traditional sausage manufacturing. Food Sci. Technol. 43, 20–25.

Lee, H., Yoon, H., Ji, Y., Kim, H., Park, H., Lee, J., et al. (2011). Functional properties of Lactobacillus strains isolated from kimchi. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 145, 155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.12.003

Lee, J. K., Jung, D. W., Kim, Y. J., Cha, S. K., Lee, M. K., Ahn, B. H., et al. (2009). Growth inhibitory effect of fermented kimchi on food-borne pathogens. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 18, 12–17.

Lee, J. W., Shin, J. G., Kim, E. H., Kang, H. E., Yim, I. B., Kim, J. Y., et al. (2004). Immunomodulatory and antitumor effects in vivo by the cytoplasmic fraction of Lactobacillus casei and Bifidobacterium longum. J. Vet. Sci. 5, 41–48.

Lee, Y. J., Kim, J. E., Kwak, M. H., Go, J., Kim, D. S., Son, H. J., et al. (2014). Quantitative evaluation of the therapeutic effect of fermented soybean products containing high concentration of GABA on phtalic anhydride-induced atopic dermatitis in IL4/Luc/CNS-1 Tg mice. Int. J. Mol. Med. 33, 1185–1194.

Lee, Y. W., Kim, J. D., Zheng, J. Z., and Row, K. H. (2007). Comparisons of isoflavones from Korean and Chinese soybean and processed products. Biochem. Eng. J. 36, 49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2006.06.009

Liem, I. T. H., Steinkraus, K. H., and Cronk, T. C. (1977). Production of vitamin B12 in tempeh, a fermented soybean food. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 34, 773–776.

Lim, J., Seo, B. J., Kim, J. E., Chae, C. S., Im, S. H., Hahn, Y. S., et al. (2011). Characteristics of immunomodulation by a Lactobacillus sakei proBio65 isolated from Kimchi. Korean J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 39, 313–316.

Lim, J. H., Jung, E. S., Choi, E. K., Jeong, D. Y., Seung-Wha, J. O., Jin, J. H., et al. (2014). Supplementation with Aspergillus oryzae-fermented kochujang lowers serum cholesterol in subjects with hyperlipidemia. Clin. Nutri. 34, 383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.05.013

Lim, S.-M., and Im, D. S. (2009). Screening and characterization of probiotic lactic acid bacteria isolated from Korean fermented foods. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 19, 178–186. doi: 10.4014/jmb.0804.269

Liu, C. F., and Pan, T. M. (2010). In vitro effects of lactic acid bacteria on cancer cell viability and antioxidant activity. J. Food Drug Anal. 18, 77–86.

Lu, Y., Wang, W., Shan, Y., Zhiqiang, E., and Wang, L. (2009). Study on the inhibition of fermented soybean to cancer cells. J. Northeast Agric. Univ. 16, 25–28.

Lv, X. C., Huang, X. L., Zhang, W., Rao, P. F., and Ni, L. (2013). Yeast diversity of traditional alcohol fermentation starters for Hong Qu glutinous rice wine brewing, revealed by culture-dependent and culture-independent methods. Food Control 34, 183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.04.020

Macouzet, M., Lee, B. H., and Robert, N. (2009). Production of conjugated linoleic acid by probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus La-5. J. Appl. Microbiol. 106, 1886–1891. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04164.x

Maintz, L., and Novak, N. (2007). Histamine and histamine intolerance. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 85, 1185–1196.

Martinez-Villaluenga, C., Peñas, E., Sidro, B., Ullate, M., Frias, J., and Vidal-Valverde, C. (2012). White cabbage fermentation improves ascorbigen content, antioxidant and nitric oxide production inhibitory activity in LPS-induced macrophages. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 46, 77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2011.10.023

Meerak, J., Lida, H., Watanabe, Y., Miyashita, M., Sato, H., Nakagawa, Y., et al. (2007). Phylogeny of poly-γ-glutamic acid-producing Bacillus strains isolated from fermented soybean foods manufactured in Asian countries. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 53, 315–323. doi: 10.2323/jgam.53.315

Meira, S. M. M., Daroit, D. J., and Helfer, V. E. (2012). Bioactive peptides in water soluble extract of ovine cheese from southern Brazil and Uruguay. Food Res. Int. 48, 322–329. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2012.05.009

Meyer, J., Butikofer, U., Walther, B., Wechsler, D., and Sieber, R. (2009). Hot topic: changes in angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and concentration of the teripeptides Val-Pro-Pro and Ile-Pro-Pro during ripening of different Swiss cheese varieties. J. Dairy Sci. 92, 826–836. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1531

Meyer, K., Kushi, L., Jacobs, D., Slavin, J., Sellers, T., and Folsom, A. (2000). Carbohydrates, dietary fiber, and incidence of type 2 diabetes in older women. Am. J. Clin. Nutri. 71, 921–930.

Mine, Y., Wong, A. H. K., and Jiang, B. (2005). Fibrinolytic enzymes in Asian traditional fermented foods. Food Res. Int. 38, 243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2004.04.008

Mitra, S., Chakrabartty, P. K., and Biswas, S. R. (2010). Potential production and preservation of dahi by Lactococcus lactis W8, a nisin-producing strain. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 43, 337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2009.08.013

Mo, H., Zhu, Y., and Chen, Z. (2008). Review. Microbial fermented tea – a potential source of natural food preservatives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 19, 124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2007.10.001

Mogensen, G., Salminen, S., O’Brien, J., Ouwehand, A., Holzapfel, W., Shortt, C., et al. (2002). Inventory of micro-organisms with a documented history of use in food. Bulletin 377, 10–19.

Mohania, D., Kansal, V. K., Sagwal, R., and Shah, D. (2013). Anticarcinogenic effect of probiotic dahi and piroxicam on DMH-induced colorectal carcinogenesis in Wister rats. Am. J. Cancer Ther. Pharmacol. 1, 8–24.

Moktan, B., Saha, J., and Sarkar, P. K. (2008). Antioxidant activities of soybean as affected by Bacillus-fermentation to Kinema. Food Res. Int. 4, 586–593.

Monteagudo-Mera, A., Rodríguez-Aparicio, L., Rúa, J., Martínez- Blanco, H., Navasa, N., García-Armesto, M. R., et al. (2012). In vitro evaluation of physiological probiotic properties of different lactic acid bacteria strains of dairy and human origin. J. Funct. Foods 4, 531–541. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2012.02.014

Montriwong, A., Kaewphuak, S., Rodtong, S., and Roytrakul, S. (2012). Novel fibrinolytic enzymes from Virgibacillus halodenitrificans SK1-3-7 isolated from fish sauce fermentation. Process. Biochem. 47, 2379–2387. doi: 10.1007/s12010-015-1591-5

Moslehishad, M., Ehsani, M. R., and Salami, M. (2013). The comparative assessment of ACE- inhibitory and antioxidant activities of peptide fractions obtained from fermented camel and bovine milk by Lactobacillus rhamnosus PTCC1637. Int. Dairy Res. 29, 82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2012.10.015

Murata, M., Houdai, T., Yamamoto, H., Matsumori, M., and Oishi, T. (2006). Membrane interaction of soyasaponins in association with their antioxidation effect –analysis of biomembrane interaction. Soy Protein Res. 9, 82–86.

Nagai, T. (2015). “Health benefits of Natto,” in Health Benefits of Fermented Foods, ed. J. P. Tamang (New York, NY: CRC Press), 433–453.

Nagai, T., and Tamang, J. P. (2010). “Fermented soybeans and non-soybeans legume foods,” in Fermented Foods and Beverages of the World, eds J. P. Tamang and K. Kailasapathy (New York, NY: CRC Press), 191–224.

Nakajima, N., Nozaki, N., Ishihara, K., Ishikawa, A., and Tsuji, H. (2005). Analysis of isoflavone content in tempeh: a fermented soybean product, and preparation of a new isoflavone-enriched tempeh. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 100, 685–687. doi: 10.1263/jbb.100.685

Nakamura, Y., Masuda, O., and Takano, T. (1996). Decrease of tissue angiotensin I-converting enzyme activity upon feeding sour milk in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 60, 488–489. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.488

Nikkuni, S., Karki, T. B., Vilku, K. S., Suzuki, T., Shindoh, K., Suzuki, C., et al. (1995). Mineral and amino acid contents of kinema, a fermented soybean food prepared in Nepal. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 1, 107–111. doi: 10.3136/fsti9596t9798.1.107

Nishito, Y., Osana, Y., Hachiya, T., Popendorf, K., Toyoda, A., Fujiyama, A., et al. (2010). Whole genome assembly of a natto production strain Bacillus subtilis natto from very short read data. BMC Genomics 11:243. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-243

Nout, M. J. R. (1994). Fermented foods and food safety. Food Res. Int. 27, 291–298. doi: 10.1016/0963-9969(94)90097-3

Nout, M. J. R., and Aidoo, K. E. (2002). “Asian fungal fermented food,” in The Mycota, ed. H. D. Osiewacz (New York: Springer-Verlag), 23–47.

Nurrahman, Astuti, M., Suparmo, M., and Soesatyo, H. N. E. (2013). The role of black soybean tempe in increasing antioxidant enzyme activity and human lymphocyte proliferation in vivo. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2, 316–327.

Okada, N. (1989). Role of microorganism in tempeh manufacture. Isolation of vitamin B12 producing bacteria. Japan Agric. Res. Q. 22, 310–316.

Omizu, Y., Tsukamoto, C., Chettri, R., and Tamang, J. P. (2011). Determination of saponin contents in raw soybean and fermented soybean foods of India. J. Sci. Indus. Res. 70, 533–538.

Oppermann-Sanio, F. B., and Steinbüchel, A. (2002). Occurence, functions and biosynthesis of polyamides in microorganisms and biotechnological productions. Naturwissenschaften 89, 11–22. doi: 10.1007/s00114-001-0280-0

Orel, R., and Trop, T. K. (2014). Intestinal microbiota, probiotics and prebiotics in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 11505–11524. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i33.11505

Otes, S., and Cagindi, O. (2003). Kefir: a probiotic dairy-composition, nutritional and therapeutic aspects. Pakistan J. Nutri. 2, 54–59. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2003.54.59

Ouwehand, A. C., Salminen, S., and Isolauri, E. (2002). Probiotics: an overview of beneficial effects. Antonie Van Leeuwen 82, 279–289. doi: 10.1023/A:1020620607611

Papadimitriou, C. G., Vafopoulou-Mastrojiannaki, A., Silva, S. V., Gomes, A. M., Malcata, F. X., and Alichanidis, E. (2007). Identification of peptides in traditional and probiotic sheep milk yoghurt with angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitory activity. Food Chem. 105, 647–656. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-9336

Park, J. A., Tirupathi Pichiah, P. B., Yu, J. J., Oh, S. H., Daily, J. W. III, and Cha, Y. S. (2012). Anti-obesity effect of kimchi fermented with Weissella koreensis OK1-6 as starter in high-fat diet-induced obese C57BL/6J mice. J. Appl. Microbiol. 113, 1507–1516. doi: 10.1111/jam.12017

Park, J. E., Moon, Y. J., and Cha, Y. S. (2008). Effect of functional materials producing microbial strains isolated from Kimchi on antiobesity and inflammatory cytokines in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. FASEB J. 23:111.

Park, J. M., Shin, J. H., Gu, J. G., Yoon, S. J., Song, J. C., Jeon, W. M., et al. (2011). Effect of antioxidant activity in kimchi during a short-term and over-ripening fermentation period. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 112, 356–359. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.06.003

Park, K. Y., Jeong, J. K., Lee, Y. E., and Daily, J. W. III (2014). Health benefits of kimchi (Korean fermented vegetables) as a probiotic food. J. Med. Foods 17, 6–20. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2013.3083

Patel, A., Prajapati, J. B., Holst, O., and Ljungh, A. (2014). Determining probiotic potential of exopolysaccharide producing LAB isolated from vegetables and traditional Indian fermented food products. Food Biosci. 5, 27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2013.10.002

Pattanagul, P., Pinthong, R., Phianmongkhol, A., and Tharatha, S. (2008). Mevinolin, citrinin and pigments of adlay angkak fermented by Monascus sp. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 126, 20–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.04.019

Paucar-Menacho, L. M., Amaya-Farfan, J., Berhow, M. A., Mandarino, J. M. G., de Mejia, E., and Chang, Y. K. (2010). A high-protein soybean cultivar contains lower isoflavones and saponins but higher minerals and bioactive peptides than a low-protein cultivar. Food Chem. 120, 15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.062

Pedone, C. A., Arnaud, C. C., Postaire, E. R., Bouley, C. F., and Reinert, P. (2000). Multicentric study of the effect of milk fermented by Lactobacillus casei on the incidence of diarrhoea. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 54, 568–571.

Peñas, E., Limón, R. I., Vidal-Valverde, C., and Frias, J. (2013). Effect of storage on the content of indole-glucosinolate breakdown products and vitamin C of sauerkrauts treated by high hydrostatic pressure. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 53, 285–289. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2013.01.015

Perna, A., Intaglietta, I., Simonetti, A., and Gambacorta, E. (2013). Effect of genetic type and casein halotype on antioxidant activity of yogurts during storage. J. Dairy Sci. 96, 1–7. doi: 10.3168/jds.2012-5859

Phelan, M., and Kerins, D. (2011). The potential role of milk derived peptides in cardiovascular diseases. Food Funct. 2, 153–167. doi: 10.1039/c1fo10017c

Ping, S. P., Shih, S. C., Rong, C. T., and King, W. Q. (2012). Effect of isoflavone aglycone content and antioxidation activity in natto by various cultures of Bacillus subtilis during the fermentation period. J. Nutri. Food Sci. 2:153. doi: 10.4172/2155-9600.1000153

Qian, B., Xing, M., Cui, L., Deng, Y., Xu, Y., Huang, M., et al. (2011). Antioxidant, antihypertensive, and immunomodulatory activities of peptide fraction from fermented skim milk with Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp bulgaricus LB340. J. Dairy Res. 78, 72–79. doi: 10.1017/S0022029910000889

Quiros, A., Hernandez-Ledesma, B., Ramos, M., Amigo, L., and Recio, I. (2005). Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory activity of peptides derived from caprine kefir. J. Dairy Sci. 88, 3480–3487. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)73032-0

Rabie, M. A., Siliha, H., El-Saidy, S., El-Badawy, A. A., and Malcata, F. X. (2011). Reduced biogenic amine contents in sauerkraut via addition of selected LAB. Food Chem. 129, 1778–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.05.106

Ramadori, G., Gautron, L., Fujikawa, T., Claudia, R., Vianna, J., Elmquist, E., et al. (2009). Central administration of resveratrol improves diet-induced diabetes. Endocrinology 150, 5326–5333. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0528

Ramrez, J. F., Sanchez-Marroquin, A., Alvarez, M. M., and Valyasebi, R. (2004). “Industrialization of Mexican pulque,” in Industrialization of Indigenous Fermented Foods, 2nd Edn, ed. K. Steinkraus (New York, NY: Marcel Deckker), 547–586.

Ranadheera, R., Baines, S., and Adams, M. (2010). Importance of food in probiotic efficacy. Food Res. Int. 43, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2009.09.009

Rauscher-Gabernig, E., Grossgut, R., Bauer, F., and Paulsen, P. (2009). Assessment of alimentary histamine exposure of consumers in Austria and development of tolerable levels in typical foods. Food Control 20, 423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2008.07.011

Reddy, N. R., and Salunkhe, D. K. (1980). Effect of fermentation on phytate phosphorus, and mineral content in black gram, rice, and black gram and rice blends. J. Food Sci. 45, 1708–1712. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1980.tb07594.x

Saad, N., Delattre, C., Urdaci, M., Schmitter, J. M., and Bressollier, P. (2013). An overview of the last advances in probiotic and prebiotic field. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 50, 1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.05.014

Sabeena, F. K. H., Baron, C. P., Nielsen, N. S., and Jacobsen, C. (2010). Antioxidant activity of yoghurt peptides: part 1-in vitro assays and evaluation in ω-3 enriched milk. Food Chem. 123, 1081–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.05.067

Sanchez, P. C. (2008). Philippine Fermented Foods: Principles and Technology. (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press), 511.

Sarkar, P. K., Jones, L. J., Craven, G. S., and Somerset, S. M. (1997). Oligosaccharides profile of soybeans during kinema production. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 24, 337–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.1997.00035.x

Sarkar, P. K., Morrison, E., Tingii, U., Somerset, S. M., and Craven, G. S. (1998). B-group vitamin and mineral contents of soybeans during kinema production. J. Sci. Food Agric. 78, 498–502. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199812)78:4<498::AID-JSFA145>3.3.CO;2-3

Sarkar, P. K., and Tamang, J. P. (1995). Changes in the microbial profile and proximate composition during natural and controlled fermentations of soybeans to produce kinema. Food Microbiol. 12, 317–325. doi: 10.1016/S0740-0020(95)80112-X

Seppo, L., Kerojoki, O., Suomalainen, T., and Korpela, R. (2002). The effect of a Lactobacillus helveticus LBK-16 H fermented milk on hypertension — a pilot study on humans. Milchwissen 57, 124–127.

Shah, N. P. (2015). “Functional properties of fermented milks,” in Health Benefits of Fermented Foods, ed. J. P. Tamang (New York, NY: CRC Press), 261–274.

Shah, N. P., da Cruz, A. G., and Faria, J. D. A. F. (2013). Probiotics and Probiotic Foods: Technology, Stability and Benefits to Human Health. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers.

Shin, D. H., and Jeong, D. (2015). Korean traditional fermented soybean products: Jang. J. Ethnic Foods 2, 2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jef.2015.02.002

Shin, D. H., Jung, S. J., and Chae, S. W. (2015). “Health benefits of Korean fermented soybean products,” in Health Benefits of Fermented Foods, ed. J. P. Tamang (New York, NY: CRC Press), 395–431.

Shin, M. S., Han, S. K., Ryu, J. S., Kim, K. S., and Lee, W. K. (2008). Isolation and partial characterization of a bacteriocin produced by Pediococcus pentosaceus K23-2 isolated from kimchi. J. Appl. Microbiol. 105, 331–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03770.x

Shin, S. K., Kwon, J. H., Jeon, M., Choi, J., and Choi, M. S. (2011). Supplementation of Cheonggukjang and Red Ginseng Cheonggukjang can improve plasma lipid profile and fasting blood glucose concentration in subjects with impaired fasting glucose. J. Med. Food 14, 108–113. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2009.1366

Shon, M. Y., Lee, J., Choi, J. H., Choi, S. Y., Nam, S. H., Seo, K. I., et al. (2007). Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity of methanol extract of chungkukjang. J. Food Composit. Anal. 20, 113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2006.08.003

Singh, T. A., Devi, K. R., Ahmed, G., and Jeyaram, K. (2014). Microbial and endogenous origin of fibrinolytic activity in traditional fermented foods of Northeast India. Food Res. Int. 55, 356–362. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.11.028

Sipola, M., Finckenberg, P., Korpela, R., Vapaatalo, H., and Nurminen, M. (2002). Effect of long-term intake of milk products on blood pressure in hypertensive rats. J. Dairy Res. 69, 103–111. doi: 10.1017/S002202990100526X

Spano, G., Russo, P., Lonvaud-Funel, A., Lucas, P., Alexandre, H., Grandvalet, C., et al. (2010). Biogenic amine in fermented foods. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 64, 95–100. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.218

Stanley, N. R., and Lazazzera, B. A. (2005). Defining the genetic differences between wild and domestic strains of Bacillus subtilis that affect poly-γ-dl-glutamic acid production and biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 57, 1143–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04746.x

Steinkraus, K. H. (1996). Handbook of Indigenous Fermented Food, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker, Inc.

Suganuma, T., Fujita, K., and Kitahara, K. (2007). Some Distinguishable properties between acid-stable and neutral types of α-amylases from acid-producing koji. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 104, 353–362. doi: 10.1263/jbb.104.353

Suzzi, G., and Gardini, F. (2003). Biogenic amines in dry fermented sausages: a review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 88, 41–54. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00080-1

Syal, P., and Vohra, A. (2013). Probiotic potential of yeasts isolated from traditional Indian fermented foods. Int. J. Microbiol. Res. 5, 390–398. doi: 10.9735/0975-5276.5.2.390-398

Szajewska, H., Skorka, A., Ruszczynski, M., and Gieruszczak-bialek, D. (2007). Meta-analysis: Lactobacillus GG for treating acute diarrhoea in children. Aliment. Pharm. Therapeut. 25, 871–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03282.x

Tamang, J. P. (2015). Naturally fermented ethnic soybean foods of India. J. Ethnic Foods 2, 8–17. doi: 10.1007/s12275-012-1409-x

Tamang, J. P., Dewan, S., Tamang, B., Rai, A., Schillinger, U., and Holzapfel, W. H. (2007). Lactic acid bacteria in Hamei and Marcha of North East India. Indian J. Microbiol. 47, 119–125. doi: 10.1007/s12088-007-0024-8

Tamang, J. P., and Fleet, G. H. (2009). “Yeasts diversity in fermented foods and beverages,” in Yeasts Biotechnology: Diversity and Applications, eds T. Satyanarayana and G. Kunze (New York: Springer), 169–198.

Tamang, J. P., and Nikkuni, S. (1996). Selection of starter culture for production of kinema, fermented soybean food of the Himalaya. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 12, 629–635. doi: 10.1007/BF00327727

Tamang, J. P., and Nikkuni, S. (1998). Effect of temperatures during pure culture fermentation of Kinema. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 14, 847–850. doi: 10.1023/A:1008867511369

Tamang, J. P., Tamang, B., Schillinger, U., Guigas, C., and Holzapfel, W. H. (2009). Functional properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from ethnic fermented vegetables of the Himalayas. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 135, 28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.07.016

Tamang, J. P., Watanabe, K., and Holzapfel, W. H. (2016). Review: Diversity of microorganisms in global fermented foods and beverages. Front. Microbiol. 7:377. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00377

Thapa, N., and Tamang, J. P. (2015). “Functionality and therapeutic values of fermented foods,” in Health Benefits of Fermented Foods, ed. J. P. Tamang (New York: CRC Press), 111–168.

Tolhurst, G., Heffron, H., Lam, Y. S., Parker, H. E., Habib, A. M., Diakogiannaki, E., et al. (2012). Short-chain fatty acids stimulate glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion via the g-protein-coupled receptor FFAR2. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 61, 364–371. doi: 10.2337/db11-1019

Tsubura, S. (2012). Anti-periodontitis effect of Bacillus subtilis (natto). Shigaku (Odontol.) 99, 160–164.

Tsuyoshi, N., Fudou, R., Yamanaka, S., Kozaki, M., Tamang, N., Thapa, S., et al. (2005). Identification of yeast strains isolated from marcha in Sikkim, a microbial starter for amylolytic fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 99, 135–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.08.011

Urushibata, Y., Tokuyama, S., and Tahara, Y. (2002). Characterization of the Bacillus subtilis ywsC gene, involved in (–polyglutamic acid production. J. Bacteriol. 184, 337–343. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.2.337-343.2002

US Probiotics Home (2011). Available at: www.usprobiotics.org

Varankovich, N. V., Nickerson, M. T., and Korber, D. R. (2015). Probiotic-based strategies for therapeutic and prophylactic use against multiple gastrointestinal diseases. Front. Microbiol. 6:685. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00685

Verna, E. C., and Lucak, S. (2010). Use of probiotics in gastrointestinal disorders: what to recommend? Ther. Adv Gastroenterol. 3, 307–319. doi: 10.1177/1756283X10373814

Visciano, P., Schirone, N., Tofalo, R., and Suzzi, G. (2014). Histamine poisoning and control measures in fish and fishery products. Front. Microbiol. 5:500. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00500

Walker, G. M. (2014). “Microbiology of winemaking,” in Encyclopaedia of Food Microbiology, 2 Edn, eds C. Batt and M. A. Tortorello (Oxford: Elsevier Ltd.), 787–792.

Wang, L. J., Li, D., Zou, L., Chen, X. D., Cheng, Y. Q., Yamaki, K., et al. (2007a). Antioxidative activity of douchi (a Chinese traditional salt-fermented soybean food) extracts during its processing. Int. J. Food Propert. 10, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/10942910601052715

Wang, L.-J., Yin, L.-J., Li, D., Zou, L., Saito, M., Tatsumi, E., et al. (2007b). Influences of processing and NaCl supplementation on isoflavone contents and composition during douchi manufacturing. Food Chem. 101, 1247–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.03.029

Weill, F. S., Cela, E. M., Paz, M. L., Ferrari, A., Leoni, J., and Gonzalez Maglio, D. H. (2013). Lipoteichoic acid from Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG as an oral photoprotective agent against UV-induced carcinogenesis. Br. J. Nutri. 109, 457–466. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512001225

Willcox, B. J., Willcox, D. C., and Suzuki, M. (2004). The Okinawa Diet Plan. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press.

Won, T. J., Kim, B., Song, D. S., Lim, Y. T., Oh, E. S., Lee, D. I., et al. (2011). Modulation of Th1/Th2 balance by Lactobacillus strains isolated from kimchi via stimulation of macrophage cell line J774A.1 in vitro. J. Food Sci. 76, H55–H61. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.02031.x

Yadav, H., Jain, S., and Sinha, P. R. (2007). Antidiabetic effect of probiotic dahi containing Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus casei in high fructose fed rats. Nutrition 23, 62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.09.002

Yanagisawa, Y., and Sumi, H. (2005). Natto bacillus contains a large amount of water-soluble vitamin K (menaquinone-7). J. Food Biochem. 29, 267–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2005.00016.x

Yanping, W., Nv, X., Aodeng, X., Zaheer, A., Bin, Z., and Xiaojia, B. (2009). Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum MA2 isolated from Tibet kefir on lipid metabolism and intestinal microflora of rats fed on high-cholesterol diet. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 84, 341–347. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2012-x

Yin, L. J., Li, D., Zou, L., Saito, M., Tatsumi, E., and Li, L. T. (2007). Influences of processing and NaCl supplementation on isoflavone contents and composition during douchi manufacturing. Food Chem. 101, 1247–1253.

Yoon, S., Do, J., Lee, S., and Chag, H. (2000). Production of poly-δ-glutamic acid by fed-batch culture of Bacillus lichenifomis. Biotechnol. Lett. 22, 585–588. doi: 10.1023/A:1005625026623

Zeng, W., Li, W., Shu, L., Yi, J., Chen, G., and Liang, Z. (2013). Non-sterilized fermentative co-production of poly (γ-glutamic acid) and fibrinolytic enzyme by a thermophilic Bacillus subtilis GXA-28. Bioresour. Technol. 142, 697–700. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.05.020

Keywords: fermented foods, microorganisms, functional properties, health benefits, bioactive compounds

Citation: Tamang JP, Shin D-H, Jung S-J and Chae S-W (2016) Functional Properties of Microorganisms in Fermented Foods. Front. Microbiol. 7:578. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00578

Received: 21 February 2016; Accepted: 08 April 2016;

Published: 26 April 2016.

Edited by:

Andrea Gomez-Zavaglia, Center for Research and Development in Food Cryotechnology (CIDCA, CONICET), ArgentinaReviewed by:

Maria De Los Angeles Serradell, CCT La Plata-CONICET, Instituto de Ciencias de la Salud-UNAJ, ArgentinaCopyright © 2016 Tamang, Shin, Jung and Chae. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jyoti P. Tamang, anlvdGlfdGFtYW5nQGhvdG1haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.