94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 14 January 2015

Sec. Food Microbiology

Volume 5 - 2014 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00766

This article is part of the Research Topic Microorganisms for Functional Food View all 16 articles

A commentary has been posted on this article:

Commentary: Probiotic and technological properties of Lactobacillus spp. strains from the human stomach in the search for potential candidates against gastric microbial dysbiosis

This work characterizes a set of lactobacilli strains isolated from the stomach of healthy humans that might serve as probiotic cultures. Ten different strains were recognized by rep-PCR and PFGE fingerprinting among 19 isolates from gastric biopsies and stomach juice samples. These strains belonged to five species, Lactobacillus gasseri (3), Lactobacillus reuteri (2), Lactobacillus vaginalis (2), Lactobacillus fermentum (2) and Lactobacillus casei (1). All ten strains were subjected to a series of in vitro tests to assess their functional and technological properties, including acid resistance, bile tolerance, adhesion to epithelial gastric cells, production of antimicrobial compounds, inhibition of Helicobacter pylori, antioxidative activity, antibiotic resistance, carbohydrate fermentation, glycosidic activities, and ability to grow in milk. As expected, given their origin, all strains showed good resistance to low pH (3.0), with small reductions in counts after 90 min exposition to this pH. Species- and strain-specific differences were detected in terms of the production of antimicrobials, antagonistic effects toward H. pylori, antioxidative activity and adhesion to gastric epithelial cells. None of the strains showed atypical resistance to a series of 16 antibiotics of clinical and veterinary importance. Two L. reuteri strains were deemed as the most appropriate candidates to be used as potential probiotics against microbial gastric disorders; these showed good survival under gastrointestinal conditions reproduced in vitro, along with strong anti-Helicobacter and antioxidative activities. The two L. reuteri strains further displayed appropriated technological traits for their inclusion as adjunct functional cultures in fermented dairy products.

Over recent decades, culture-independent techniques have revealed the stomach to be home to a well-adapted, niche-specific microbial community (Bik et al., 2006; Andersson et al., 2008; Delgado et al., 2013). Gastric microbial communities are of potential probiotic use in the treatment of several diseases, but only a few studies have attempted to cultivate their members (Adamson et al., 1999; Li et al., 2009; Delgado et al., 2013). The isolation and characterization of stomach originated strains could provide novel probiotic candidates with enhanced capacities to counteract gastric pathogens such as Helicobacter pylori (Cui et al., 2010). This Gram-negative, microaerophilic microorganism infects over 50% of the population worldwide (Bruce and Maaroos, 2008). Indeed, H. pylori is the most important aetiological agent in chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers and gastric cancer (Peek and Blaser, 2002). The eradication (efficiency 80–90%) of H. pylori is possible using a combination of antibiotics and antacids. However, side-effects are common. As an alternative or complementary therapy, or indeed as a preventive strategy, use might be made of probiotics for the management of this infection (Malfertheiner et al., 2007). To date, studies have focused on conventional probiotic cultures from different origins. Among these, Lactobacillus reuteri having anti H. pylori action is one promising approach (Francavilla et al., 2008).

The aim of the present work was to examine in vitro the functional and technological characteristics of Lactobacillus isolates recovered from the stomach mucosa and gastric juice of healthy individuals in a previous study (Delgado et al., 2013) for their evaluation as probiotics in functional products against H. pylori infection. Gastric candidate probiotic strains with potential application in the prevention and treatment of gastric disorders and dysbiosis were then selected.

Nineteen Lactobacillus isolates belonging to five different species were cultured from gastric biopsies and stomach juice samples provided by healthy subjects (see Delgado et al., 2013). Unless otherwise indicated, all isolates were cultured in de Man, Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) medium supplemented with 0.25% cysteine (Merck) (MRSC). Incubations proceeded at 37°C for 24 h in an anaerobic chamber (Mac500, Down Whitley Scientific, West Yorkshire, UK) containing an anoxic atmosphere (10% H2, 10% CO2, 80% N2).

The isolates were genotyped by repetitive extragenic palindromic (rep)-PCR and by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) fingerprinting. For rep-PCR, total DNA from the isolates was purified from overnight cultures using the GenElute™ Bacterial Genomic DNA Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), following the manufacturer's recommendations. Amplifications were performed using the primer BoxA2-R (5′-ACGTGGTTTGAAGAGATTTTCG-3′), as reported by Koeuth et al. (1995). For PFGE, genomic DNA was isolated and digested at 30°C for 4 h in agarose plugs containing 20 U of the restriction endonuclease SmaI (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany). Electrophoresis was performed in 1% FastLane agarose gels (FMC, Philadelphia, PA, USA) in 0.5X TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) for 20 h at 14°C and at 6 V/cm, using a CHEF-DRII apparatus (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA). Pulse times ranged from 0.1 to 2 s for 4 h, from 2 to 5 s for 12 h, and from 5 to 10 s for 4 h. Low-range and bacteriophage lambda ladder PFGE markers (both from New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) were included in the gels.

The ability of the isolates to survive under acidic conditions was assessed by exposing the cells to an acidic solution. HCl was added to cell suspensions (≈108 cells/ml) in a sterile saline solution (0.9%) to achieve pHs ranging from 2.0 to 6.5 (pH 7.0 was used as a control). The cells were then incubated at 37°C for 90 min. After incubation the pH of the medium was recorded again and the viability of the strains assessed by plate counting on MRSC.

The tolerance of the strains to bovine bile (Ox-gall, Sigma-Aldrich) was assayed following the procedure of Charteris et al. (1998). Briefly, individual colonies from MRSC plates were suspended in 2 ml of sterile saline solution until a density corresponding to McFarland standard 1 was obtained. Aliquots of this suspension (10μl) were spotted onto bile-containing agar plates. The concentration of bile assayed ranged from 0.25 to 4% (w/v).

H. pylori DSM 10242 was routinely grown in solid or liquid brain heart infusion medium (BHI; Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK), supplemented with either 5% (w/v) horse blood (Oxoid) or 10% (w/v) fetal bovine serum (Oxoid), respectively. Inoculated cultures were then incubated at 37°C for 3–7 days under the microaerophilic conditions generated by the CampyGen system (Oxoid). Antagonistic activity of lactobacilli against H. pylori was assessed by a broth inhibition assay after growing of the test strains in Elliker broth (Scharlau, Barcelona, Spain), since MRS medium inhibits the growth of this pathogen (Ryan et al., 2008b). Inhibition assays were performed in 96-well, “U”-bottom polystyrene microtitre plates. Supplemented BHI was inoculated at 1.5 (v/v) with a concentrated H. pylori culture (OD600 nm 1.0), and the cell suspension was dispensed into the wells of a microtitre plate. Then, 45 μl of the supernatant of each individual lactobacilli strain were added to the wells. As a negative control, aliquots of non-inoculated Elliker medium were also tested. The multi-well plates were then incubated for 3 days under the same conditions as above, and the OD600 nm recorded using a microplate spectrophotometer (Benchmark; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Assays were also performed with pH-neutralized supernatants (pH 6.6). All experiments were repeated twice using independent cultures; all supernatants were further assayed in triplicate.

Bacteriocin production was consecutively examined by an agar spot test and a well-diffusion assay as previously described (Delgado et al., 2007), using two well-recognized bacteriocin-susceptible strains (Lactobacillus sakei CECT 906 and Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis IL1403) as indicators.

H2O2 production was tested following the procedure described by Song et al. (1999). MRSC agar plates supplemented with 0.25 mg/ml of tetramethylbenzidine (TMB, Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.01 mg/ml of horseradish peroxidase (HRP, Sigma-Aldrich) were inoculated with the strains and incubated at 37°C under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions. The presence of any blue pigment in the H2O2–producing colonies was recorded after 2 days. Lactobacillus jensenii CECT 4306 (Martín and Suárez, 2010) was used as positive control.

The presence of the gene coding for the large subunit of glycerol dehydratase, which is essential in the production of reuterin (3-hydroxypropionaldehyde) (Claisse and Lonvaud-Funel, 2001), was checked for in the Lactobacillus reuteri strains via PCR. L. reuteri CECT 925, a reuterin-producing strain (Martín et al., 2005), was used as positive control.

The adhesion of the strains to the gastric mucosa was assessed in vitro using the gastric cell line AGS (ECACC number 89090402, Sigma-Aldrich), which is derived from a human gastric adenocarcinoma. The latter cells were cultured as per routine in Ham's F12 medium (LabClinics, Barcelona, Spain) supplemented with 2 mM of L-glutamine (PAA Laboratories GmbH, Paschina, Austria), 10% fetal bovine serum, plus 50 μg/ml of penicillin, 50 μg/ml of streptomycin, 50 μg/ml of gentamicin, and 1.25 μg/ml amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich). Monolayers of the cells were prepared in 24-well tissue culture plates (Becton Dickinson, New Jersey, USA) at a concentration of 105 cells/ml. After reaching confluence and differentiating (3 + 1 days), the strains were added at a ratio 1:1. For this, bacterial cultures were harvested by centrifugation, washed with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline solution (Sigma-Aldrich), and suspended in Ham's F12 medium without antibiotics. After 1 h of co-incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, the monolayers were washed 3 times with a phosphate-buffered saline solution to remove any non-attached bacteria. The monolayers were then disrupted with a 0.25% trypsin-EDTA solution (Sigma-Aldrich), and the attached bacteria enumerated by standard dilution and plate counting on MRSC. Experiments were carried out in triplicate and each strain tested in duplicate. The adhesion capacity of the strains was compared to that of the recognized probiotic strain Lactobacillus rhamnosus ATCC 53103 (strain GG). The results were expressed as the percentage of adhered bacteria with respect to the initial number of bacteria added.

The total antioxidative activity (TAA) of the gastric lactobacilli was assessed using the linolenic acid (LA) test, which evaluates the ability to inhibit lipid peroxidation. Bacterial cultures (24 h) were centrifuged, washed twice in saline solution, and suspended in the same solution to an OD600 nm of 1.0. Intact cells in the saline solution were examined, as were lysates obtained using a cell disruptor (Constant Systems, Daventry, UK). Reactions were performed according to the procedure described by Kullisaar et al. (2002), using 45μl samples (whole cells or lysate). The absorbance at 534 nm was measured using a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Hitachi High-Technologies, Tokyo, Japan). Intact cells and cell lysates were assayed in triplicate. The results were expressed as the percentage of LA oxidation inhibition.

The resistance/susceptibility profiles of the different strains to 16 antibiotics were determined by microdilution using VetMIC™ plates for lactic acid bacteria (LAB) (National Veterinary Institute of Sweden, Uppsala, Sweden). The strains were grown in LSM (Klare et al., 2005) agar plates and then suspended in 2 ml of sterile saline solution to obtain a density corresponding to McFarland standard 1. The suspension was further diluted 1:1000 with LSM, and 100μl of this inoculum were added to each well. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest antibiotic concentration at which no visual growth was observed after incubation at 37°C for 48 h.

The carbohydrate fermentation profile of the strains was initially determined using a miniaturized commercial system (Phene-Plate, Stockholm, Sweden), following the manufacturer's instructions. Growth in the presence of different substrates (lactose, maltose, trehalose, melibiose and raffinose [all from Sigma-Aldrich]) was further evaluated by recording the OD600 nm at 24 and 48 h. The strains were inoculated (1% v/v) into a basal fermentation medium (MRS without glucose) supplemented with 2% (w/v) of the carbohydrate under test. All strains had been previously adapted overnight in the corresponding fermentation broth.

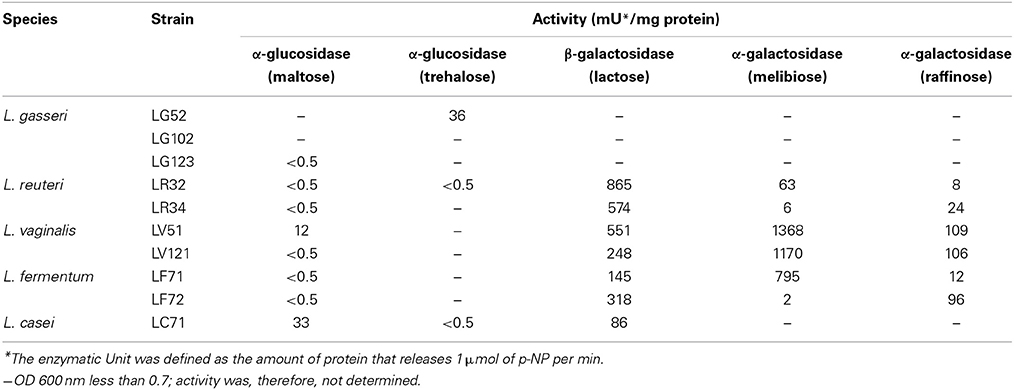

Enzyme activities were initially measured using the semi-quantitative API-ZYM system (bioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France), following the manufacturer's instructions. Glycosidic activities in cell-free extracts were confirmed and quantified by enzyme assays using the p-nitrophenyl (p-NP) derivatives 4-NP-β-D-glucopyranoside, 4-NP-α-D-glucopyranoside, 4-NP-β-D-galactopyranoside and 4-NP-α-D-galactopyranoside (all from Sigma-Aldrich) as substrates. Cells from 20 ml cultures in basal fermentation medium with different inducing carbohydrates were harvested by centrifugation, washed with 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 6.8, and the pellets suspended in 2 ml of the same buffer. Cells were disrupted as above and centrifuged to remove cell debris. The extracts were then assayed for glycosidic activity. Reactions were performed using 800μl of 40 mM buffer acetate pH 5.5, 100μl of the different p-NP derivatives at 10 mM, and 100μl of the cell-free extracts. Incubation proceeded for 30 min at 37°C and the reactions were then stopped by adding 1 ml of cold 1 M sodium carbonate. After centrifugation, the absorbance at 410 nm was recorded. The protein content of cell-free extracts was determined using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Activities were expressed as specific activity in mU per mg of protein. One unit of activity (1 U) was defined as the amount of protein that released 1 μmol of p-NP per min.

Overnight cultures, previously washed in a sterile saline solution, were used to inoculate UHT milk (CAPSA, Siero, Spain) to provide an initial cell concentration of about 107 cfu/ml. After incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 and 48 h, bacterial counts were performed on MRSC agar plates. The pH of the inoculated and control milk samples was measured using a Crison pH-meter (Crison Instruments, Barcelona, Spain) and via titration with phenolphthalein according to FIL/IDF Standard 86.

The 19 gastric lactobacilli isolates (9 Lactobacillus gasseri, 4 Lactobacillus reuteri, 3 Lactobacillus vaginalis, 2 Lactobacillus fermentum and 1 Lactobacillus casei) were successively typed by rep-PCR and PFGE (Supplementary Figure 1). The results of these two techniques agreed well, and 10 different strains were considered based on their distinct electrophoretic profiles provided by both methods. The ten selected strains included three L. gasseri strains (LG52, LG102, and LG123) from two subjects, two L. reuteri strains (LR32 and LR34) from a single subject, two L. vaginalis strains (LV51 and LV121) from different subjects, two genetically unrelated L. fermentum strains (LF1 and LF2) from a single subject, and a single strain of L. casei (LC71).

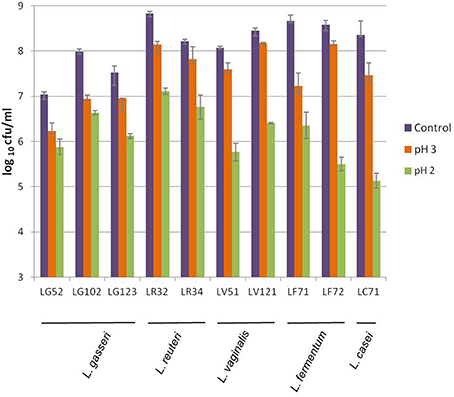

As a whole, high tolerance to acidity was detected; similar plate counts were returned by control (pH 7) and treated samples after exposure to pH 4.5 and above (data not shown). At pH 3 reductions in counts varied among strains but in less than 1 logarithmic unit in all cases (Figure 1). However, at pH 2, reductions compared to controls counts were between 1 and 3 logarithmic units. The L. gasseri strains were among the most acid tolerant.

Figure 1. Viability of the gastric Lactobacillus strains of this study to acidic conditions after exposure to pH 3 and pH 2 for 90 min, as compared to the control (pH 7.0).

Resistance of the strains to bile varied widely, depending largely on the species. The L. gasseri strains were the most susceptible (MICs 0.25–1.5%), followed by those of L. fermentum (MIC = 1%). The most resistant strains were those of L. reuteri, L. vaginalis and L. casei, which grew in the presence of 4% bile.

The percentage of adhesion to gastric cells was strain-dependent but <10% for all strains - even for L. rhamnosus GG (Figure 2). The most adherent strain was L. casei LC71 (8.5%) followed by L. reuteri LR32 and L. gasseri LG102.

Regarding the bacteriocin-mediated antagonism assays, some gastric strains of the species L. reuteri, L. gasseri and L. fermentum were able to slightly inhibit the growth of the indicators in the agar spot test, although clear halos of inhibition using cell-free, neutralized supernatants were only observed for L. gasseri LG52 (Supplementary Table 1). The proteinaceous nature of the antimicrobial bacteriocin-like substance produced by this strain was confirmed after treatment of the cell-free supernatants with proteinase K and pronase, both of which eliminated the antibacterial effect.

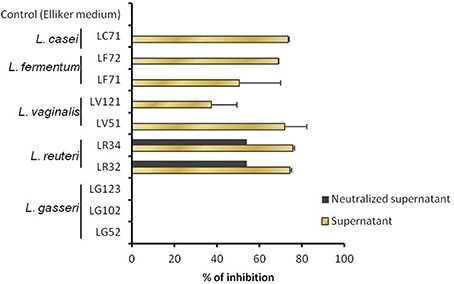

On the other hand, the H. pylori inhibitory test revealed all strains to have some antimicrobial activity against this pathogen, except for those of L. gasseri (Figure 3). The highest inhibitory values (~75%) were obtained for the two L. reuteri strains. When the supernatants were neutralized, H. pylori growth was suppressed only by the pH-adjusted supernatants pertaining to the L. reuteri strains, suggesting that the inhibition observed for the other strains was probably due to the production of organic acids. Further, the presence of genes associated with reuterin production (coding for the glycerol dehydratase unit) was revealed by PCR in the two L. reuteri strains.

Figure 3. Growth inhibition of Helicobacter pylori, as determined in liquid with non-adjusted and pH-neutralized supernatants of the Lactobacillus strains grown in Elliker medium.

As concerns H2O2 production, all L. gasseri strains showed slight production under aerobic conditions, while the L. vaginalis and L. reuteri strains clearly produced this substance under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Supplementary Table 1).

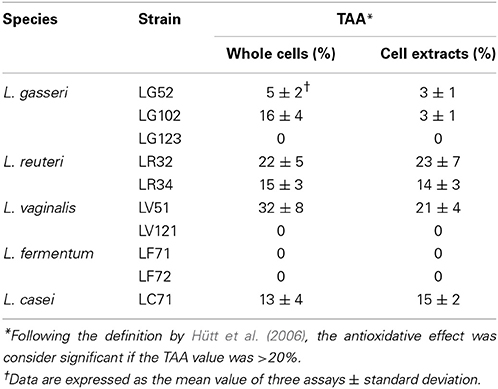

Strain-specific differences were also observed with respect to their TAA, as assessed by the LA test (Table 1). Comparable results were obtained using either whole cells or cell lysates. Remarkable activity (TAA >20%) was observed for L. reuteri LR32 and L. vaginalis LV51, and moderate activity (around a 15% reduction of lipid peroxidation) for L. casei LC71 and L. reuteri LR34. Neither the L. fermentum strains, nor L. gasseri LG123 and L. vaginalis LV121 showed any antioxidative activity under the experimental conditions of this assay.

Table 1. Percentages of total antioxidative activity (TAA) determined by the linolenic acid test in intact cells and lysates of the gastric lactobacilli.

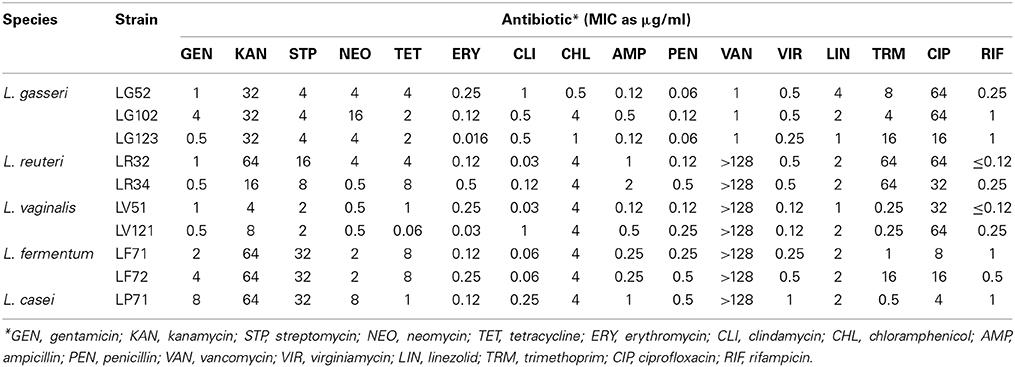

Atypical antibiotic resistance was not detected for any of the strains (Table 2). The MICs of the different antibiotics were always equal to or lower than the microbiological breakpoints defined by the Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP) of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA, 2012). The exception was kanamycin, for which a MIC value of 64 μg/ml was observed for the two L. fermentum strains; the EFSA's breakpoint established for this species is one dilution lower.

Table 2. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of 16 antibiotics to the gastric lactobacilli strains.

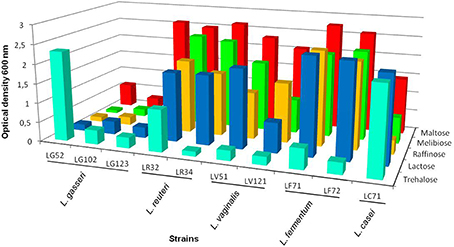

Differences were observed between the 10 strains in terms of their utilization of carbohydrates (Supplementary Table 2). All strains fermented maltose, and all but L. gasseri LG102 and LG123 fermented sucrose. Lactose was fermented by the single L. casei, the two L. reuteri, and the two L. fermentum strains. The growth capacity of the strains in basal fermentation medium with lactose, maltose, threhalose, melibiose and raffinose was further evaluated by recording the optical density after 24 and 48 h (Figure 4). In general, and in agreement with the previous results, the L. gasseri strains showed a reduced fermentation capacity compared to the others. Most of the gastric strains grew in the presence of maltose and lactose as the sole carbon source. The ability to grow in trehalose, however, was restricted to a few Lactobacillus strains (Figure 4). The L. reuteri, L. vaginalis and L. fermentum strains showed good growth rates in the presence of raffinose and melibiose.

Figure 4. Optical density at 600 nm of the lactobacilli strains grown in basal fermentation medium at 37°C for 48 h using different carbohydrates: maltose, melibiose, raffinose, lactose and trehalose as the carbon source (coefficient of variation <10%).

Nineteen enzymatic activities were tested with the API-ZYM system. Moderate inter- and intra-species variability on the substrates utilized was observed (Supplementary Table 3). Some activities were shown by all or most strains and at high levels (Cys-, Val-, and Leu- arylamidase peptidases, and α- and β-galactohydrolase activities). In contrast, other activities (such as those of lipase, trypsin, α-quimotrypsin, α-mamnosidase, and α-fucosidase) were detected at low levels and only rarely. Glycosidic activities were also examined in cell-free extracts after growth of the strains in inducing carbohydrates. These activities may have a prominent role in key probiotic properties, such as utilization of prebiotics, colonization of the gastric epithelium, etc. The results are summarized in Table 3. With the exception of the L. gasseri strains (which did not grow in the presence of lactose) all showed high β-galactosidase activity. The L. vaginalis strains showed strong α-galactosidase activity, but so too did the L. reuteri and L. fermentum strains. The L. casei strain returned the highest α-glucosidase activity in presence of maltose.

Table 3. Glycosidic activities of the Lactobacillus strains determined in cell-free extracts using p-nitrophenyl derivatives.

Table 4 shows the strains' ability to grow in and acidify milk. After 24 h of incubation, the cell counts of all the strains increased slightly, but the figures for most (particularly L. vaginalis and L. fermentum) fell by 48 h. The exceptions were the L. reuteri strains, which reached values of around 2 × 108 cfu/ml, and the L. casei strain, which showed the highest viable count (1 × 109 cfu/ml) and the lowest pH at both sampling points. As expected, the titratable acidity followed an inverse trend with respect to pH, increasing as the pH decreased. A titratable acidity of around 81% of lactic acid equivalent after 48 h of incubation was recorded for L. casei LC71.

The acidic environment of the gastric lumen limits the latter's microbial colonization to acidophilic and acid-resistant bacteria. Among these, different LAB species belonging mainly to the genera Lactobacillus and Streptococcus have been described (Adamson et al., 1999; Ross et al., 2005; Ryan et al., 2008a; Delgado et al., 2013). In this study, members of the genus Lactobacillus isolated from the stomach of healthy humans (see Delgado et al., 2013) were studied. Four out of the five Lactobacillus species examined (L. gasseri, L. fermentum, L. vaginalis and L. reuteri) have also been isolated from human gastric biopsies by other authors (Ryan et al., 2008a), which strongly suggests that they are common inhabitants of the gastric environment. Different strains belonging to the same species in a single individual were detected only occasionally. Based on the typing results, ten different strains were considered; these were characterized for their technological and probiotic properties. In general, they showed good tolerance and survival at low pH, indicating their capacity to survive in the human stomach. However, resistance to low pHs for longer periods of time (and colonization of the gastric epithelium) would be required to ensure persistence in the human stomach. Resistance to acidic conditions is a property of interest for the design and formulation of probiotic cultures. Such an ability would allow not only survival in the upper gastrointestinal tract, but also in fermented products (the most common vehicle for probiotics). The molecular mechanisms involved in such intrinsic resistance are currently unknown. The contribution of urease activity to this resistance however can be ruled out since all the present strains proved to be urease-negative (data not shown).

Since duodenogastric biliary reflux occasionally occurs, strains could also be resistant to bile. In fact, high resistance to bovine bile in lactobacilli strains from the gastric ecosystem has already been reported (Ryan et al., 2008a). Among the strains of this study, the L. reuteri proved to be the most resistant to Ox-gall. In contrast, as described for intestinal L. gasseri isolates (Delgado et al., 2007), the gastric strains of this species were rather susceptible to bile.

The strains were shown to adhere to gastric epithelial cells just as well, or even better than, the well-recognized adherent strain L. rhamnosus GG (Tuomola and Salminen, 1998). However, comparison of the results with those reported on the literature is difficult given the use of different cell lines (mostly colorectal Caco-2 and HT-29) and different cell-to-bacteria ratios employed.

Probiotics may be useful in the treatment of gastric dysbiosis, such as those caused by H. pylori infections. In fact, several studies have reported an inhibitory effect of probiotic lactobacilli on colonization and development of this pathogen (Johnson-Henry et al., 2004; Sykora et al., 2005; Francavilla et al., 2008). H. pylori colonizes the epithelium of the stomach and duodenum, occasionally invading the cells. Colonization seems to reduce systemic and cellular antioxidative defenses (Hütt et al., 2009). The antioxidative potential of the strains was therefore tested, a property that has already been reported for certain lactobacilli strains (Kullisaar et al., 2002). According to Hütt et al. (2006), total antioxidative (TAA) values >20% are considered noteworthy. In the present work, two strains, L. reuteri LR32 and L. vaginalis LV51, met this criterion. This protective property may be useful as a defense mechanism for the gastric mucosa, preserving the tissue from oxidant-induced damage.

The gastric lactobacilli were also screened for their antimicrobial activities against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The production of bacteriocin-like inhibitory substances varies widely among LAB species and strains (de Vuyst and Leroy, 2007). After successive solid and liquid medium assays, a single L. gasseri strain (LG52) was consistently shown to be bacteriocin producer. However, whether LG52 produces an active bacteriocin under gastric conditions remains yet to be investigated. Another potential source of inhibitory effects is H2O2, which in certain environments might be more important than the production of organic acids. The stomach is a microaerobic environment and the production of H2O2 might be greater under such conditions than in anaerobiosis. This prompted us to evaluate the production of H2O2 under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. The two L. reuteri strains and L. vaginalis LV51 were shown to produce this compound under both conditions. These strains must have H2O2 detoxification mechanisms that allow them to protect themselves from its toxic effects. Superoxide dismutases, peroxidases and dehydrogenases are all able to degrade H2O2, and have been described in lactobacilli species (Kullisaar et al., 2002; Hütt et al., 2006; Martín and Suárez, 2010). These enzymes contribute toward the antioxidative cell defense system. In the present work, the strains with the largest H2O2 production capacity were those with the greatest antioxidative activity.

The inhibition of H. pylori by the two L. reuteri strains was probably due to the production of reuterin; certainly, a gene essential for its production was detected. Reuterin is a potent antimicrobial agent that inhibits both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. L. reuteri also produces other potent antimicrobial compounds, such as reutericin 6 and reutericyclin, but these have no effects on Gram-negative bacteria (Gänzle, 2004). The inhibition of H. pylori by lactobacilli has already been reported (Sgouras et al., 2004; Hütt et al., 2006; López-Brea et al., 2008; Ryan et al., 2008b). However, most authors attribute the observed inhibitory effects to live metabolizing cells. In contrast, the present work provides evidence of the inhibitory effect of L. reuteri culture supernatants against H. pylori. Wherever this inhibitory activity comes from, the potential use of these human stomach-derived L. reuteri strains as probiotics for protecting against H. pylori infection should be considered.

While L. gasseri seems to be more prevalent in the gastric ecosystem than L. reuteri, the strains of the latter species displayed more probiotic-relevant properties and/or higher activity levels. The antimicrobial—and especially anti-H. pylori—activity of the L. reuteri strains, together with their antioxidative effects, might allow them to protect the gastric mucosa from infection and damage. The L. reuteri strains also showed some technological traits that would allow their inclusion in fermented dairy products. Strains of other species further showed desirable traits to be recommended as probiotic candidates. As an example, L. vaginalis LV51 showed the strongest α-galactosidase activity. This would be highly desirable in soy-derived products to hydrolyse the α-galactosides (mainly raffinose and stachyose) capable of causing gastrointestinal discomfort and flatulence (LeBlanc et al., 2008).

In summary, this work reports a genotypic, technological and probiotic description and characterization of a group of lactobacilli from the human stomach. In vitro, some of the gastric strains (particularly the L. reuteri strains) showed a vast array of desirable properties to be considered as promising probiotic candidates. Additionally, they showed appropriate technological traits to be included in dairy or other fermented functional foods as adjunct cultures. The efficacy of such probiotics for the treatment and/or prevention of gastric microbial dysbiosis should be carefully evaluated in vivo through controlled clinical trials.

Susana Delgado and Baltasar Mayo contributed with the conception and design of the study. Susana Delgado and Analy M. O. Leite were involved in the experimental determinations. Patricia Ruas-Madiedo was in charge of the adhesion experiments and in the maintenance of the gastric cell line. Susana Delgado and Baltasar Mayo interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. Patricia Ruas-Madiedo performed a critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the article.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This research was funded by projects from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and Innovation (Ref. AGL2011-24300) and FICYT (Ref. IB08-005). Susana Delgado was supported by a contract under Juan de la Cierva program (Ref. JCI-2008-02391). The technical assistance of Elena Fernández and Alicia Noriega is greatly acknowledged.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00766/abstract

Adamson, I., Nord, C. E., Lundquist, P., Sjöstedt, S., and Edlund, C. (1999). Comparative effects of omeprazole, amoxycillin plus metronidazole versus omeprazole, clarithromycin plus metronidazole on the oral, gastric and intestinal microflora in Helicobacter pylori-infected patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44, 629–640.

Andersson, A., Lindberg, M., Jakobsson, H., Bäckhed, F., Nyrén, P., and Engstrand, L. (2008). Comparative analysis of human gut microbiota by barcoded pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE 3:e2836. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002836

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bik, E. M., Eckburg, P. B., Gill, S. R., Nelson, K. E., Purdom, E. A., Francois, F., et al. (2006). Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in the human stomach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 732–737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506655103

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bruce, M. G., and Maaroos, H. I. (2008). Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 13 (Suppl. 1), 1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00631.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Charteris, W. P., Kelly, P. M., Morelli, L., and Collins, J. K. (1998). Development and application of an in vivo methodology to determine the transit tolerance of potentially probiotic Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species in the upper human gastrointestinal tract. J. Appl. Microbiol. 84, 759–768.

Claisse, O., and Lonvaud-Funel, A. (2001). Primers and a specific DNA probe for detecting lactic acid bacteria producing 3-hydroxypropionaldehyde from glycerol in spoiled ciders. J. Food Protect. 64, 833–837.

Cui, Y., Wang, C. L., Liu, X. W., Wang, X. H., Chen, L. L., Zhao, X., et al. (2010). Two stomach-originated Lactobacillus strains improve Helicobacter pylori infected murine gastritis. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 445–452. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i4.445

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Delgado, S., Cabrera-Rubio, R., Mira, A., Suárez, A., and Mayo, B. (2013). Microbiological survey of the human gastric ecosystem using culturing and pyrosequencing methods. Microbial. Ecol. 65, 763–772. doi: 10.1007/s00248-013-0192-5

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Delgado, S., O'Sullivan, E., Fitzgerald, G., and Mayo, B. (2007). Subtractive screening for probiotic properties of Lactobacillus species from the human gastrointestinal tract in the search for new probiotics. J. Food Sci. 72, M310–M315. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00479.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

de Vuyst, L., and Leroy, F. (2007). Bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria: production, purification, and food applications. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 13, 194–199. doi: 10.1159/000104752

EFSA. (2012). Guidance on the assessment of bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobials of human and veterinary importance. EFSA J. 10, 2740–2749.

Francavilla, R., Lionetti, E., Castellaneta, S. P., Magistà, A. M., Maurogiovanni, G., Bucci, N., et al. (2008). Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori infection in humans by Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 and effect on eradication therapy: a pilot study. Helicobacter 13, 127–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00593.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Gänzle, M. G. (2004). Reutericyclin: biological activity, mode of action, and potential applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 64, 326–332. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1536-8

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hütt, P., Andreson, H., Kullisaar, T., Vihalemm, T., Unt, E., Kals, J., et al. (2009). Effects of a synbiotic product on blood antioxidative activity in subjects colonized with Helicobacter pylori. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 48, 797–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02607.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hütt, P., Shchepetova, J., Lõivukene, K., Kullisaar, T., and Mikelsaar, M. (2006). Antagonistic activity of probiotic lactobacilli and bifidobacteria against entero- and uropathogens. J. Appl. Microbiol. 100, 1324–1332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02857.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Johnson-Henry, K. C., Mitchell, D. J., Avitzur, Y., Galindo-Mata, E., Jones, N. L., and Sherman, P. M. (2004). Probiotics reduce bacterial colonization and gastric inflammation in H. pylori-infected mice. Dig. Dis. Sci. 49, 1095–1102. doi: 10.1023/B:DDAS.0000037794.02040.c2

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Klare, I., Konstabel, C., Müller-Bertling, S., Reissbrodt, R., Huys, G., Vancanneyt, M., et al. (2005). Evaluation of new broth media for microdilution antibiotic susceptibility testing of lactobacilli, lactococci, pediococci, and bifidobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 8982–8986. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8982-8986.2005

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Koeuth, T., Versalovic, J., and Lupski, J. R. (1995). Differential subsequence conservation of interspersed repetitive Streptococcus pneumoniae BOX elements in diverse bacteria. Genome Res. 5, 408–418.

Kullisaar, T., Zilmer, M., Mikelsaar, M., Vihalemm, T., Annuk, H., Kairane, C., et al. (2002). Two antioxidative lactobacilli strains as promising probiotics. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 72, 215–224. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(01)00674-2

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

LeBlanc, J. G., Ledue-Clier, F., Bensaada, M., de Giori, G. S., Guerekobaya, T., Sesma, F., et al. (2008). Ability of Lactobacillus fermentum to overcome host alpha-galactosidase deficiency, as evidenced by reduction of hydrogen excretion in rats consuming soya alpha-galacto-oligosaccharides. BMC Microbiol. 8:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-22

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Li, X. X., Wong, G. L. H., To, K. F., Wong, V. W. S., Lai, L. H., Chow, D. K. L., et al. (2009). Bacterial microbiota profiling in gastritis without Helicobacter pylori infection or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. PLoS ONE 4:e7985. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007985

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

López-Brea, M., Alarcón, T., Domingo, D., and Díaz-Regañón, J. (2008). Inhibitory effect of Gram-negative and Gram-positive microorganisms against Helicobacter pylori clinical isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61, 139–142. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm404

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Malfertheiner, P., Megraud, F., O'Morain, C., Bazzoli, F., El-Omar, E., Graham, D., et al. (2007). Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III consensus report. Gut 56, 772–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Martín, R., Olivares, M., Marín, M. L., Xaus, J., Fernández, L., and Rodríguez, J. M. (2005). Characterization of a reuterin-producing Lactobacillus coryniformis strain isolated from a goat's milk cheese. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 104, 267–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.03.007

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Martín, R., and Suárez, J. E. (2010). Biosynthesis and degradation of H2O2 by vaginal lactobacilli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 400–405. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01631-09

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Peek, R. M., and Blaser, M. J. (2002). Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc703

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ross, S., Engstrand, L., and Jonsson, H. (2005). Lactobacillus gastricus sp. nov., Lactobacillus antri sp. nov., Lactobacillus kalixensis sp. nov. and Lactobacillus ultunensis sp. nov., isolated from human stomach mucosa. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 55, 77–82. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63083-0

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ryan, K. A., Daly, P., Li, Y., Hooton, C., and O'Toole, P. W. (2008b). Strain-specific inhibition of Helicobacter pylori by Lactobacillus salivarius and other lactobacilli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 61, 831–834. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn040

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ryan, K. A., Jarayaman, T., Daly, P., Canchaya, C., Curran, S., Fang, F., et al. (2008a). Isolation of lactobacilli with probiotic properties from the human stomach. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 47, 269–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02416.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Sgouras, D., Maragkoudakis, P., Petraki, K., Martinez-Gonzalez, B., Eriotou, E., Michopoulos, S., et al. (2004). In vitro and in vivo inhibition of Helicobacter pylori by Lactobacillus casei strain Shirota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 518–526. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.518-526.2004

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Song, Y. L., Kato, N., Matsumiya, Y., Liu, C. X., Kato, H., and Watanabe, K. (1999). Identification of and hydrogen peroxide production by fecal and vaginal lactobacilli isolated from Japanese women and newborn infants. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37, 3062–3064.

Sykora, J., Valeckova, K., Amlerova, J., Siala, K., Dedek, P., Watkins, S., et al. (2005). Effects of a specially designed fermented milk product containing probiotic Lactobacillus casei DN-114 001 and the eradication of H. pylori in children: a prospective randomized double-blind study. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 39, 692–698. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000173855.77191.44

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Keywords: stomach microbiota, gastric lactobacilli, specific probiotics, functional characterization, antioxidative activity, anti-Helicobacter activity, fermentation capability

Citation: Delgado S, Leite AMO, Ruas-Madiedo P and Mayo B (2015) Probiotic and technological properties of Lactobacillus spp. strains from the human stomach in the search for potential candidates against gastric microbial dysbiosis. Front. Microbiol. 5:766. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00766

Received: 31 October 2014; Accepted: 16 December 2014;

Published online: 14 January 2015.

Edited by:

Maria De Angelis, University of Bari Aldo Moro, ItalyReviewed by:

Luca Cocolin, Univeristy of Turin, ItalyCopyright © 2015 Delgado, Leite, Ruas-Madiedo and Mayo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Susana Delgado, Instituto de Productos Lácteos de Asturias (IPLA), Paseo del Río Linares s/n, 33300 Villaviciosa, Spain e-mail:c2RlbGdhZG9AaXBsYS5jc2ljLmVz

†Present address: Analy M. O. Leite, Departamento de Microbiologia Geral, Instituto de Microbiologia, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.