95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 30 October 2014

Sec. Systems Microbiology

Volume 5 - 2014 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00575

This article is part of the Research Topic Development of microbial ecological theory: stability, plasticity and evolution of microbial ecosystems View all 15 articles

Investigation of microbial interspecies interactions is essential for elucidating the function and stability of microbial ecosystems. However, community-based analyses including molecular-fingerprinting methods have limitations for precise understanding of interspecies interactions. Construction of model microbial consortia consisting of defined mixed cultures of isolated microorganisms is an excellent method for research on interspecies interactions. In this study, a model microbial consortium consisting of microorganisms that convert acetate into methane directly (Methanosaeta thermophila) and syntrophically (Thermacetogenium phaeum and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus) was constructed and the effects of elevated CO2 concentrations on intermicrobial competition were investigated. Analyses on the community dynamics by quantitative RT-PCR and fluorescent in situ hybridization targeting their 16S rRNAs revealed that high concentrations of CO2 have suppressive effects on the syntrophic microorganisms, but not on the aceticlastic methanogen. The pathways were further characterized by determining the Gibbs free energy changes (ΔG) of the metabolic reactions conducted by each microorganism under different CO2 concentrations. The ΔG value of the acetate oxidation reaction (T. phaeum) under high CO2 conditions became significantly higher than -20 kJ per mol of acetate, which is the borderline level for sustaining microbial growth. These results suggest that high concentrations of CO2 undermine energy acquisition of T. phaeum, resulting in dominance of the aceticlastic methanogen. This study demonstrates that investigation on model microbial consortia is useful for untangling microbial interspecies interactions, including competition among microorganisms occupying the same trophic niche in complex microbial ecosystems.

In natural and engineered environments, many species of microorganisms coexist by interacting with each other. Comprehension of interspecies interactions is essential for describing the features of complex microbial ecosystems, and competition among microorganisms occupying similar trophic niches is a conventional and significant aspect of such interspecies interaction. Coexistence of multiple microorganisms with similar trophic niches is regarded as one of the major factors to confer functional stability and resiliency on microbial ecosystems (Loreau et al., 2001; Deng, 2012). It is important to grasp how the population of each microorganism changes depending on a specific environmental disturbance. Most microbial ecological research has assessed the effects of specific environmental factors on competitive interactions among multiple microbial species by observing the transition of abundances of each microorganism responding to environmental disturbances. Although this approach has produced many excellent outcomes, existence of non-target microorganisms and uncontrollable environmental factors in the systems often hamper precise understanding of the effects of specific environmental factors on the competitive interactions among target microorganisms.

Construction of microbial model consortia, in which interspecies interactions in ecosystems are reproduced by defined co-culture of isolated microorganisms, is appreciated as a worthwhile method to investigate microbial interactions (Haruta et al., 2009; De Roy et al., 2014; Großkopf and Soyer, 2014). For instance, the complex phenomenon of bacterial competition as being similar to rock-paper-scissors among colisin-producing, colisin-resistant, and colisin-sensitive strains was untangled by constructing model co-culture systems (Kerr et al., 2002; Nahum et al., 2011). Kato et al. (2005, 2008) constructed model microbial consortia composed of 4–5 bacterial strains, in which all members stably coexisted for long period of time, and demonstrated that existence of both positive and negative interspecies interactions among the members make these consortia stable. The construction of model consortia is a specific and beneficial feature of microbiological research fields, which will also be effective for proof-of-concept studies for theories in the field of macro-ecology (Haruta et al., 2009, 2013).

Methanogenesis from organic compounds is a complex microbial process accomplished by catabolic interactions among different trophic levels of microorganisms (Schink, 1997; Jones et al., 2008; Kato and Watanabe, 2010). Among the sequential biodegradation processes, acetate is the most important intermediary metabolite (Schink, 1997). Methanogenic acetate degradation proceeds by either aceticlastic methanogenesis or syntrophic acetate oxidation. The aceticlastic pathway is solely mediated by aceticlastic methanogens (Jetten et al., 1992). On the contrary, syntrophic acetate oxidation pathway requires cooperative interactions of two different types of microorganisms: acetate is first oxidized to H2 and CO2 by syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacteria (SAOB), and then hydrogenotrophic methanogens convert the products to CH4 (Zinder and Koch, 1984). As the acetate oxidation reaction is endoergonic under the standard conditions and is feasible only under extremely low H2 partial pressure, acetate oxidation by SAOB requires H2 elimination by hydrogenotrophic methanogens (Karakashev et al., 2006; Hattori, 2008). These two different acetate-degrading methane-producing pathways and organisms involved can co-exist, but diverse environmental factors, such as temperature, pH, salinity, toxic compounds, and concentrations of substrates determine one pathway and organisms to dominate over the other (Nüsslein et al., 2001; Shigematsu et al., 2004; Karakashev et al., 2006; Hao et al., 2013; Kato et al., 2014).

In our previous studies, we demonstrated that the syntrophic pathway is the dominant methanogenic acetate degradation pathway in underground, thermophilic petroleum reservoirs (Mayumi et al., 2011). We further demonstrated that aceticlastic pathway becomes dominant under high CO2 concentrations, which mimicked carbon capture and storage field conditions (Mayumi et al., 2013), whereas syntrophic acetate oxidation dominated over aceticlastic reactions under low CO2 concentrations. Since CO2 is either substrate or product of aceticlastic methanogenesis, acetate oxidation, and hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, high CO2 concentration alters the thermodynamics of each methanogenic reaction, which may cause the observed transition between syntrophic and aceticlastic methanogenic pathways. However, all the data were based on the analyses of complex microbial communities in field samples thus many other factors that affect the community shift could not be ruled out.

In the present study, the effect of CO2 concentrations on methanogenic microorganisms were assessed by using a defined inorganic medium and a defined methanogenic consortium which is comprised of three organisms, i.e., SAOB, hydrogenotrophic methanogen and aceticlastic methanogen, namely, which contains two different acetate-degrading methanogenic pathways. The experiments allowed to precisely show the CO2 concentrations to be a crucial factor affecting the dominance of respective pathways and organisms.

Methanosaeta thermophila DSM6194T (Kamagata and Mikami, 1991) and Thermacetogenium phaeum DSM12270T (Hattori et al., 2000) were obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkukturen GmbH (Braunschweig, Germany). Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus strain TM was isolated from a thermophilic anaerobic methanogenic reactor in Japan (Hattori et al., 2000). Routine cultivations were conducted at 55°C with 68-ml capacity serum vials containing 20 ml of a bicarbonate-buffered inorganic medium (pH 7.0; Kato et al., 2014) under an atmosphere of N2-CO2 [80/20 (v/v)] without shaking. Pyruvate (40 mM) or 200 kPa H2-CO2 [80/20 (v/v)] was supplemented as energy and carbon sources for the pure cultures of T. phaeum and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus, respectively. Sodium acetate (40 mM) was utilized as an energy and carbon source for the pure culture of Methanosaeta thermophila, the defined co-culture of T. phaeum and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus, and the tri-culture of the three strains. The tri-culture was constructed by simultaneously inoculating 1 and 2 ml of the early-stationary phases of pure culture of Methanosaeta thermophila and the defined co-culture of T. phaeum and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus, respectively, into the 20 ml of the medium. Although the long term stability of the tri-culture was not been tested, coexistence of the three microorganisms in the batch culture was confirmed.

Three culture conditions were prepared to examine the effects of CO2 concentrations on the microorganisms. For each condition, the media were supplemented with different concentrations of sodium bicarbonate and the gas phases were replaced with N2/CO2 mixed gas with different volume ratios, as described in Table 1. The medium was bubbled with the respective deoxygenated gas with 100 ml min-1 for 5 min and immediately capped with a butyl rubber stopper and an aluminum cap. The medium pH was adjusted to 7.0 by adding 1N NaOH solution before the cultivation, and the fluctuation of pH value throughout the cultivation was less than 0.2. For pH measurement, 100 μl of the medium was sampled with syringes and the pH value was determined using a compact pH meter B-212 (Horiba). The concentration of CO2 in the aqueous phase [caq (M)] was calculated according to Henry’s law (caq = kp), where k is the Henry’s low constant (0.019 for CO2 at 55°C) and p is the partial pressure of CO2 in the gas phase (atm). Then the bicarbonate concentrations were calculated based on the equilibrium formula (H2CO3 = H+ + ) with the equilibrium constant of 4.47 × 107. The culture experiments were conducted in triplicate and the student’s t-test was used for the statistical analyses.

Growth of Methanosaeta thermophila and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus in pure and mixed cultures was determined by measuring methane production. Growth of T. phaeum pure culture was determined by measuring acetate production from pyruvate. The partial pressure of CH4 was determined using a gas chromatograph GC-2014 (Shimadzu) as described previously (Kato et al., 2014). The partial pressure of H2 was determined using a trace reduction gas analyzer TRA-1000 (ACE Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The concentrations of organic acids were determined using a high performance liquid chromatography (D-2000 LaChrom Elite HPLC system, HITACHI) equipped with Aminex HPX-87H Ion Exclusion column (BIO-RAD) and L2400 UV detector (HITACHI).

Microbial cells of the tri-cultures in the early stationary phases were collected by centrifugation, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2) and left for 6 h at 4°C. The samples were washed three times with PBS, immobilized on glass slides, and dehydrated by successive passages through 50, 70, 80, 90, and 100% ethanol (3 min each). The following oligonucleotide probes complementary to specific regions of 16S rRNA were utilized for hybridizations: (i) Alexa488-labeled EUB338, specific for the domain Bacteria (Amann et al., 1990) and (ii) TexRed-labeled ARCH917, specific for the domain Archaea (Loy et al., 2002), (iii) Alexa594-labeled MSMX860, specific for the order Methanosarcinales (Raskin et al., 1994), and (iv) Alexa488-labeled MB311, specific for the order Methanobacteriales (Crocetti et al., 2006). Hybridizations were performed at 46°C for 3 h with hybridization buffer (0.9 M NaCl, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) containing 5 ng μl-1 of each labeled probe. The specificity of each probe was confirmed by FISH observations using pure cultures of the three microorganisms used in this study even with the hybridization buffer not containing formamide. The washing step was done at 48°C for 30 min with washing buffer (0.2 M NaCl, 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). The samples hybridized with the probes were observed with a fluorescent microscope Provis AX70 (Olympus).

Microbial cells were harvested from the mid-logarithmic phases by centrifugation at 10,000 X g and 4°C. Total RNA was isolated using ISOGEN II reagent (Nippon Gene, Japan) combined with a bead-beating method, as described previously (Kato et al., 2014). Total RNA was purified using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) with DNase treatment (RNase-free DNase set, Qiagen) as described in the manufacturer’s instructions. The purified RNA was spectroscopically quantified using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies). The PCR primers used for quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) were designed with Primer3 software (http://simgene.com/Primer3) and are listed in Table 2. Quantification of 16S rRNA copy numbers in the defined mixed culture were performed by one-step real-time RT-PCR using a Mx3000P QPCR System (Stratagene) and RNA-direct SYBR Green Realtime PCR Master Mix (Toyobo) as described previously (Kato et al., 2014). At least three biological replicates were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis, and at least two separate trials were conducted for each sample. Standard curves were generated with serially diluted PCR products (103–108 copies ml-1) amplified using the respective primer sets and were used to calculate the copy number of rRNA in the total RNA samples.

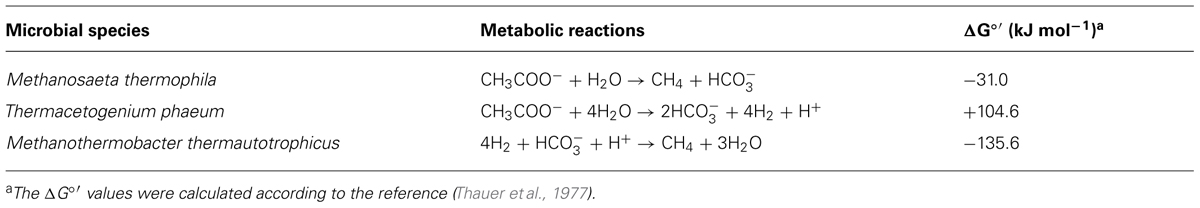

As the model consortium performing methanogenic acetate degradation, we utilized a defined mixed culture of an aceticlastic methanogen (Methanosaeta thermophila), a hydrogenotrophic methanogen (Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus), and a SAOB (T. phaeum; Table 3). These microbial species were originally isolated from a thermophilic methanogenic digester (Kamagata and Mikami, 1991; Hattori et al., 2000) and are regarded as representative species for the methanogenic acetate degradation reactions that occur in various natural environments such as high-temperature petroleum reservoirs (Pham et al., 2009; Mayumi et al., 2011, 2013) and thermophilic methanogenic digesters (Sekiguchi et al., 1998; McHugh et al., 2003; Hori et al., 2011).

TABLE 3. The metabolic reactions and the respective standard Gibbs free energy changes (ΔG°’) of the microorganisms utilized in this study.

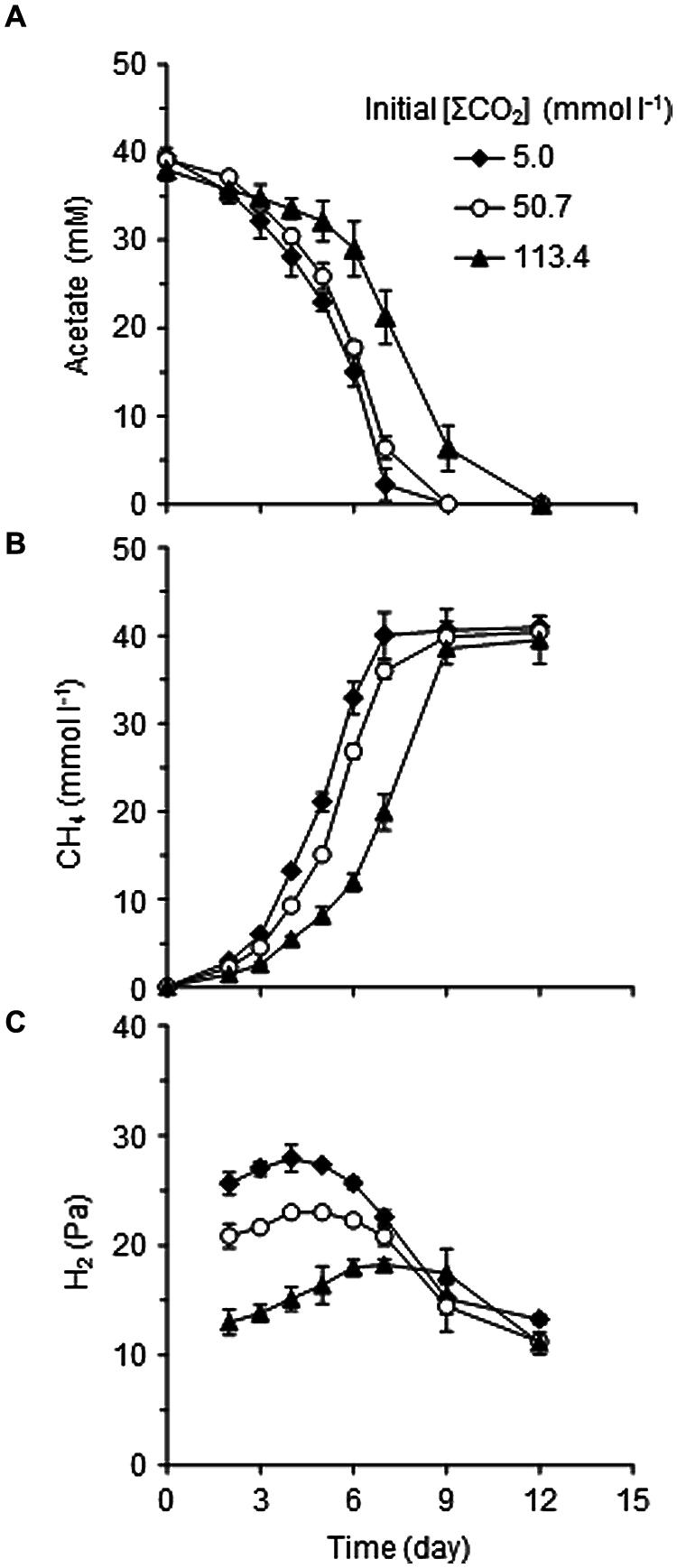

To adequately assess the effects of CO2 concentration itself, media with different supplementation of CO2/ were prepared (Table 1). The initial concentrations of total CO2/ in the cultures, designated as [ΣCO2]initial, were 5.0, 50.7, or 113.4 mmol l-1. The model consortium composed of Methanosaeta thermophila, Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus, and T. phaeum was cultivated under the three different [ΣCO2]initial conditions to evaluate their methanogenic acetate degradation abilities (Figure 1). A stoichiometric production of CH4 from acetate in a 1:1 molar ratio was observed in all culture conditions tested. Both acetate consumption and CH4 production rates slightly decreased with increasing the [ΣCO2]initial (Figures 1A,B). Interestingly, the partial pressure of H2, which is an important intermediate of syntrophic acetate degradation, significantly decreased with increasing the [ΣCO2]initial (Figure 1C). This observation suggests that syntrophic methanogenic microorganisms are influenced by elevated CO2 concentrations.

FIGURE 1. Effects of CO2 concentrations on the metabolism of the model consortium composed of Thermacetogenium phaeum, Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus, and Methanosaeta thermophila. Time courses of acetate (A), CH4 (B), and H2 (C) concentrations during cultivation on acetate with different [ΣCO2]initial are shown. Data are presented as means of three independent cultures, and error bars represent SDs.

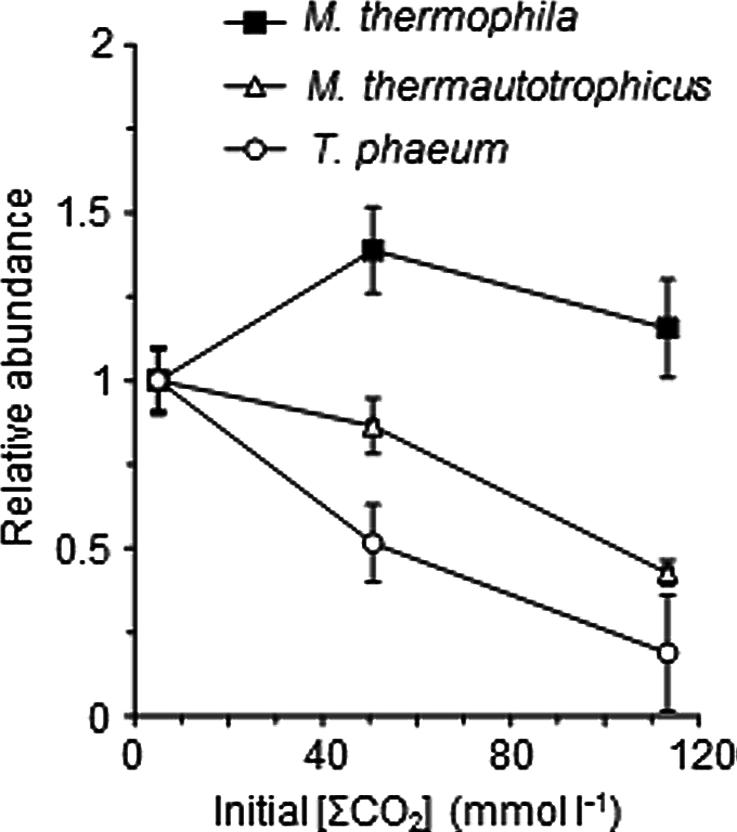

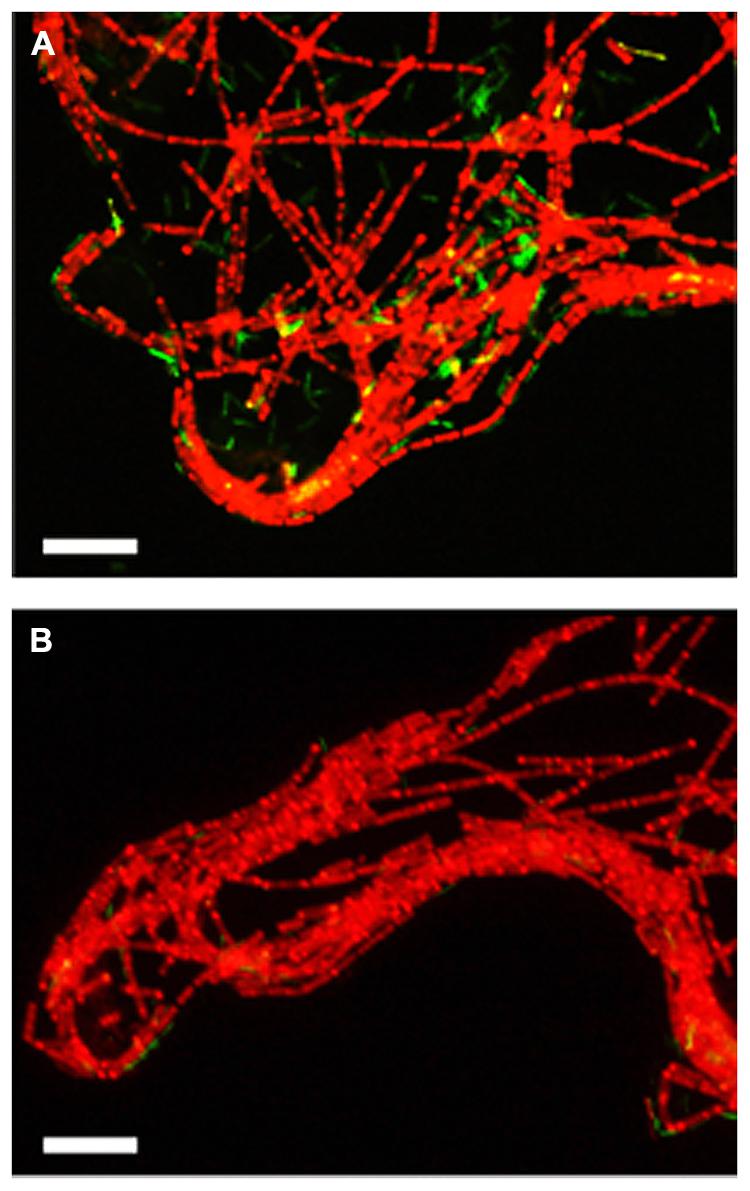

To assess the influence of the elevated CO2 concentrations on each methanogenic pathway, the relative abundances of each microorganism in the exponentially growing cultures of the model consortium with the different [ΣCO2]initial were evaluated by FISH and qRT-PCR analyses. The qRT-PCR analysis clearly demonstrated the decrease of the abundances of Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus and T. phaeum in the higher [ΣCO2]initial cultures (Figure 2). The FISH analysis also demonstrated that the relative abundances of Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus and T. phaeum in the cultures with higher CO2 concentrations are significantly lower than those in the low CO2 cultures (Figure 3). These results indicate that the syntrophic methanogenic pathway is more strongly influenced by the elevation of CO2 concentrations compared to the aceticlastic pathway.

FIGURE 2. Relative abundances of T. phaeum, Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus, and Methanosaeta thermophila in the model consortium with different [ΣCO2]initial. The 16S rRNA copy numbers of each microorganism in the mid-exponential phases were determined by the qRT-PCR analysis. The abundance of each microorganism was normalized against those of the cultures with [ΣCO2]initial of 5.0 mmol l-1, and plotted against the respective [ΣCO2]initial values. Data are presented as the means of three independent cultures, and error bars represent SDs.

FIGURE 3. Fluorescent microscopic images of the three-strains consortium cultivated with the [ΣCO2]initial of 5.0 (A) or 113.4 mmol l–1 (B). The exponential phase cultures were subjected to in situ hybridization with the probes described in the Materials and Methods section. Red, Methanosaeta thermophila (hybridized with Archaea917-TexRed and MSMX860-Alexa594); Yellow, Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus (hybridized with Archaea917-TexRed and MB311- Alexa488); Green, T. phaeum (hybridized with EUB338-Alexa488). Bars = 10 μm.

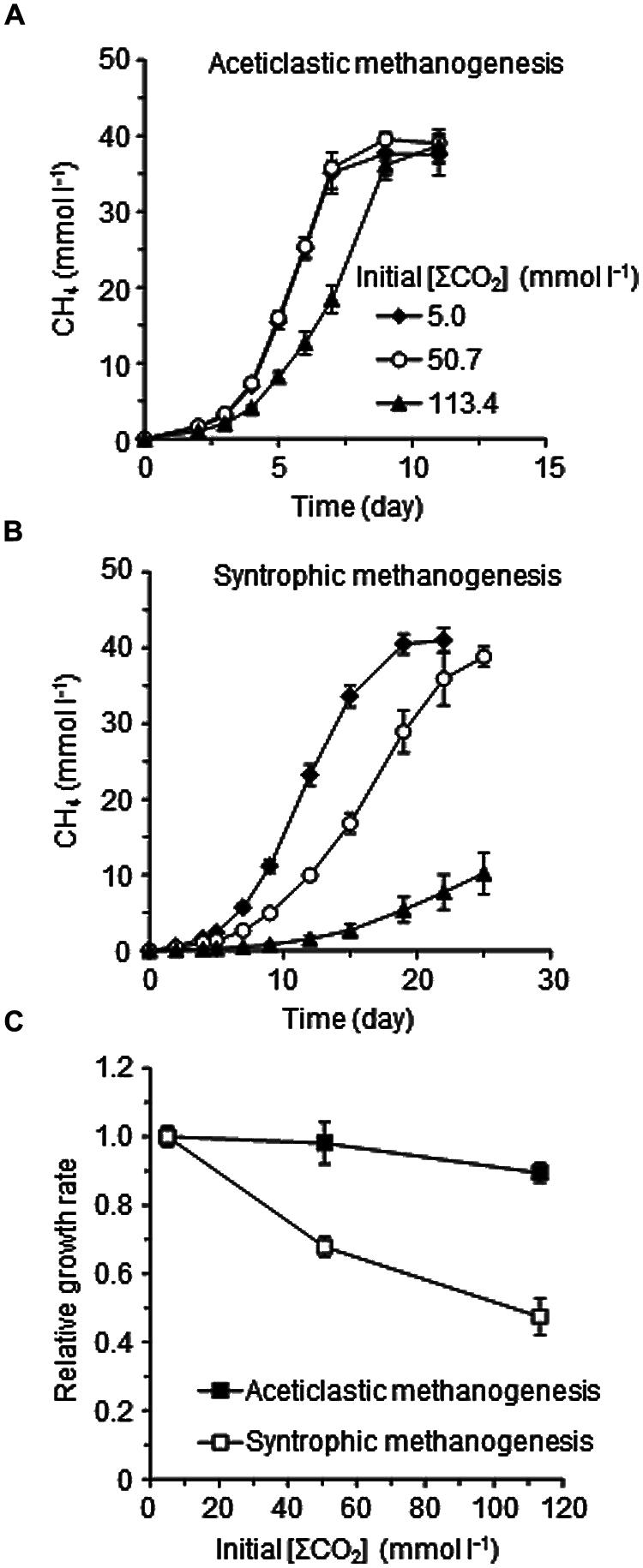

To confirm the differences in the suppressive effects of elevated CO2 concentrations on the two methanogenic pathways, the pure culture of Methanosaeta thermophila and the defined co-culture of Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus and T. phaeum were separately cultivated in the media with the different [ΣCO2]initial (Figure 4). The growth of Methanosaeta thermophila was barely affected by the elevated CO2 concentration: the methanogenic rate in the [ΣCO2]initial of 113.4 mmol l-1 cultures decreased only about 10% compared to the cultures with [ΣCO2]initial of 5.0 mmol l-1 (Figures 4A,C). On the contrary, the methanogenic rate of the syntrophic co-culture in the [ΣCO2]initial of 113.4 mmol l-1 dropped to less than half of that in the cultures with [ΣCO2]initial of 5.0 mmol l-1 (Figures 4B,C). These observations confirm the assumption that the syntrophic acetate degradation pathway is more susceptible to elevated CO2 concentrations than the aceticlastic pathway.

FIGURE 4. Effects of CO2 concentrations on aceticlastic methanogenesis by the pure-culture of Methanosaeta thermophila (A), syntrophic methanogenesis by the defined co-culture of T. phaeum and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus (B), and the relative methanogenic rates of the aceticlastic and syntrophic methanogenic cultures (C). The methanogenic rates determined from respective methane generation data (A,B) were normalized against those of the cultures with [ΣCO2]initial of 5.0 mmol l-1. Data are presented as the means of three independent cultures and error bars represent SDs.

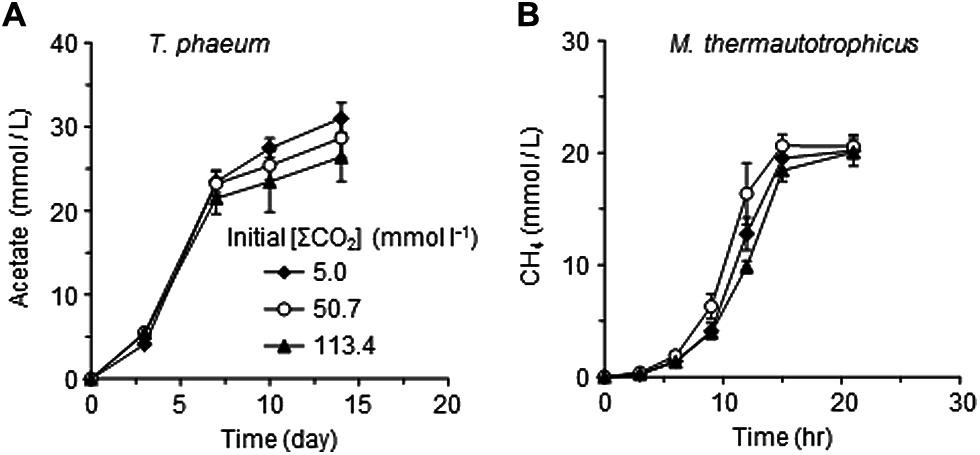

One possible explanation for the suppressive effects of CO2 on the syntrophic methanogenesis is the susceptibility of Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus and/or T. phaeum to some environmental alterations induced by increased CO2 or to CO2 itself. To evaluate this possibility, pure cultures of Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus and T. phaeum were cultivated in media with different [ΣCO2]initial (Figure 5). No significant differences were observed for the growth of both Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus and T. phaeum under the different CO2 conditions tested. These results suggest that elevated CO2 concentrations negatively affect the microbial activity only when Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus and T. phaeum are in a syntrophic relationship.

FIGURE 5. Effects of CO2 concentrations on the pure cultures of T. phaeum (A) and Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus (B). Data are presented as the means of three independent cultures, and error bars represent SDs.

The other possible explanation for the suppression of syntrophic methanogenesis by elevated CO2 concentration is alterations of thermodynamic conditions of each microbial reaction. A minimum energy required for biochemical energy conversion is estimated at around –20 kJ mol-1 (Schink, 1997), while some anaerobic microorganisms have been reported to thrive under more thermodynamically restricted conditions (Jackson and McInerney, 2002; Nauhaus et al., 2002). The value was estimated from the energetics of ATP formation (around -70 kJ mol-1 under the physiological conditions; Jetten et al., 1991; Tran and Unden, 1998) and the number of protons transported to ATP formation (between 3 and 4; Maloney, 1983; Stock et al., 1999). Since syntrophic methanogenesis from acetate is one of the least exergonic microbial metabolisms (Schink, 1997), it is no wonder that only slight perturbations on the thermodynamics induce deteriorations of the syntrophic methanogenesis.

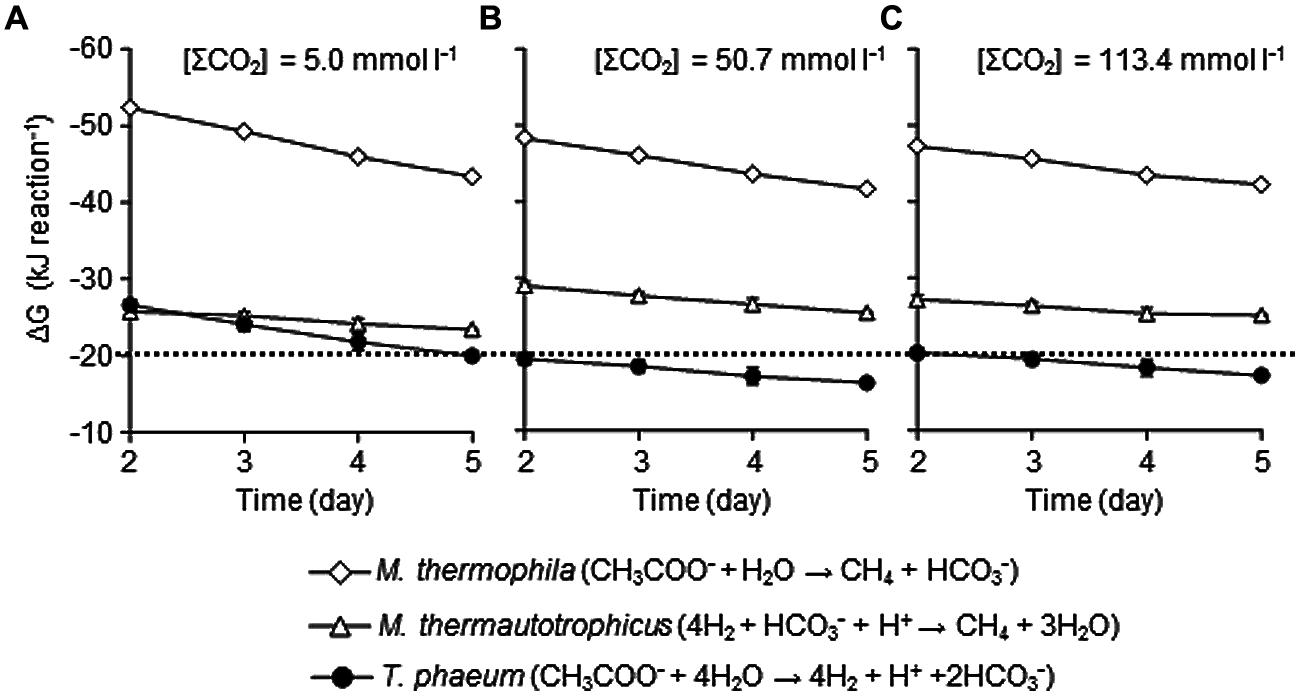

To evaluate the influences of elevated CO2 concentrations on the thermodynamic properties, ΔG values of metabolic reactions conducted by each microorganism in the model consortium were determined using the data-set of metabolite concentrations shown in Figure 1. The ΔG values of the aceticlastic methanogenesis conducted by Methanosaeta thermophila were not significantly influenced by the elevated CO2 concentrations (Figure 6). The average ΔG values during the logarithmic growth phase (day 2–5) with the [ΣCO2]initial of 5.0, 50.7 and 113.4 mmol l-1 were -47.7 ± 3.5, -44.9 ± 2.6, and -44.6 ± 2.0 kJ mol-1, respectively, which are substantially lower than the ΔG value required for microbial energy acquisition.

FIGURE 6. Effects of CO2 concentrations on the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) of metabolisms of each microorganism under the conditions with the [ΣCO2]initial of 5.0 (A), 50.7 (B), or 113.4 mmol l–1 (C). The ΔG values were calculated using metabolite concentration data presented in Figure 1. The dotted line represents ΔG value of –20 kJ/reaction. Data are presented as the means of three independent cultures and error bars represent SDs.

The ΔG values of the hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis catalyzed by Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus were also largely not altered with different CO2 settings and were constantly lower than -20 kJ mol-1 (Figure 6). The average ΔG values during the logarithmic growth phases with the [ΣCO2]initial of 5.0, 50.7, and 113.4 mmol l-1 were -24.6 ± 1.0, -27.2 ± 1.0, and -26.0 ± 1.2 kJ mol-1, respectively. Since CO2 is the substrate for hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, lower ΔG values under the higher CO2 conditions are expected. However, the decrease in H2 partial pressures under the higher CO2 conditions (Figure 1C) compensates for the positive effects of increase in CO2 concentration.

On the contrary, elevation of CO2 concentrations significantly influenced the ΔG values of the acetate oxidation reaction performed by T. phaeum (Figure 6). While the average ΔG value during the logarithmic growth phases with the [ΣCO2]initial of 5.0 mmol l-1 (-23.1 ± 2.7 kJ mol-1) was less than the borderline ΔG value of -20 kJ mol-1, those with the [ΣCO2]initial of 50.7 and 113.4 mmol l-1 (-17.8 ± 1.3 and -18.7 ± 1.4 kJ mol-1, respectively) exceeded the borderline. As acetate oxidation reaction produces 2 mol of CO2 from 1 mol of acetate, it is rational that this reaction is strongly influenced by the elevation of CO2 concentration. The decrease in the partial pressure of H2, the other metabolic product of acetate oxidation, is expected to compensate for the negative effects of increase in CO2. However, the decrease in H2 partial pressure would be limited by the minimum threshold for H2 consumption by Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus. The minimum thresholds for H2 utilization by hydrogenotrophic methanogens have been reported as around 5–10 Pa (Lovley, 1985; Thauer et al., 2008). However, considering the energy required for active growth, H2 partial pressure of around 10–15 Pa observed in the increased CO2 conditions in this study may be the minimum H2 threshold for the syntrophic interaction. Actually, if the H2 partial pressure in the cultures with [ΣCO2]initial of 113.4 mmol l-1 at the logarithmic growth phase (day 5) becomes 10 Pa, the ΔG value becomes > -20 kJ mol-1 (-19.7 ± 0.3 kJ mol-1) from the actual value of -25.1 ± 1.4 kJ mol-1 (with H2 partial pressure of 16.4 ± 1.7 Pa). These results clearly demonstrated that high concentrations of CO2 thermodynamically constrain the acetate oxidizing reaction, which results in the deterioration of syntrophic methanogenesis from acetate.

This is the first paper to evaluate the influence of elevated CO2 concentration on the two different methanogenic acetate degradation pathways, namely aceticlastic and syntrophic pathways, using a model microbial consortium. As expected from the observations based on in situ environments with complex microbial communities, high concentrations of CO2 suppressed the syntrophic pathway rather than the aceticlastic pathway. Thermodynamic calculations revealed that the acetate oxidation reaction is more intensely constrained by elevated CO2 concentrations. This study exemplified the importance of even slight changes in the ΔG values of microbial metabolisms in anaerobic biota. Furthermore, this study demonstrated that the construction of model microbial consortia is useful for assessing competitive interspecies interactions even in anaerobic, methanogenic environments.

Souichiro Kato, Tomoyuki Sato, and Yoichi Kamagata designed the research. Souichiro Kato, Rina Yoshida, Takashi Yamaguchi, Tomoyuki Sato, and Isao Yumoto carried out the experiments and analyzed the data. Souichiro Kato and Yoichi Kamagata wrote the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work was supported by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). We thank Dr. Mia Terashima and Hiromi Ikebuchi for helpful comments by critical reading and technical assistance, respectively.

Amann, R. I., Krumholz, L., and Stahl, D. A. (1990). Fluorescent-oligonucleotide probing of whole cells for determinative, phylogenetic, and environmental studies in microbiology. J. Bacteriol. 172, 762–770.

Crocetti, G., Murto, M., and Björnsson, L. (2006). An update and optimization of oligonucleotide probes targeting methanogenic Archaea for use in fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH). J. Microbiol. Methods 65, 194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.07.007

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Deng, H. (2012). A review of diversity-stability relationship of soil microbial community: what do we not know? J. Environ. Sci. 24, 1027–1035. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(11)60846-2

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

De Roy, K., Marzorati, M., Van den Abbeele, P., Van de Wiele, T., and Boon, N. (2014). Synthetic microbial ecosystems: an exciting tool to understand and apply microbial communities. Environ. Microbiol. 16, 1472–1481. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12343

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Großkopf, T., and Soyer, O. S. (2014). Synthetic microbial communities. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 18, 72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2014.02.002

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hao, L., Lü, F., Li, L., Wu, Q., Shao, L., and He, P. (2013). Self-adaption of methane-producing communities to pH disturbance at different acetate concentrations by shifting pathways and population interaction. Bioresour. Technol. 140, 319–327. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2013.04.113

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Haruta, S., Kato, S., Yamamoto, K., and Igarashi, Y. (2009). Intertwined interspecies relationships: approaches to untangle the microbial network. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 2963–2969. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01956.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Haruta, S., Yoshida, T., Aoi, Y., Kaneko, K., and Futamata, H. (2013). Challenges for complex microbial ecosystems: combination of experimental approaches with mathematical modeling. Microbes Environ. 28, 285–294. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME13034

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hattori, S. (2008). Syntrophic acetate-oxidizing microbes in methanogenic environments. Microbes Environ. 23, 118–127. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.23.118

Hattori, S., Kamagata, Y., Hanada, S., and Shoun, H. (2000). Thermacetogenium phaeum gen. nov., sp. nov., a strictly anaerobic, thermophilic, syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50, 1601–1609. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-4-1601

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hori, T., Sasaki, D., Haruta, S., Shigematsu, T., Ueno, Y., Ishii, M.,et al. (2011). Detection of active, potentially acetate-oxidizing syntrophs in an anaerobic digester by flux measurement and formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase (FTHFS) expression profiling. Microbiology 157, 1980–1989. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.049189-0

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jackson, B. E., and McInerney, M. J. (2002). Anaerobic microbial metabolism can proceed close to thermodynamic limits. Nature 415, 454–456. doi: 10.1038/415454a

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Jetten, M. S. M., Stams, A. J. M., and Zehnder, A. J. B. (1991). Adenine nucleotide content and energy charge of Methanothrix soehngenii during acetate degradation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 84, 313–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1991. tb04616.x

Jetten, M. S. M., Stams, A. J. M., and Zehnder, A. J. B. (1992). Methanogenesis from acetate: a comparison of the acetate metabolism in Methanothrix soehngenii and Methanosarcina spp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 88, 181–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb04987.x

Jones, D. M., Head, I. M., Gray, N. D., Adams, J. J., Rowan, A. K., Aitken, C. M.,et al. (2008). Crude-oil biodegradation via methanogenesis in subsurface petroleum reservoirs. Nature 451, 176–180. doi: 10.1038/nature06484

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kamagata, Y., and Mikami, E. (1991). Isolation and characterization of a novel thermophilic Methanosaeta strain. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41, 191–196. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-2-191

Karakashev, D., Batstone, D. J., Trably, E., and Angelidaki, I. (2006). Acetate oxidation is the dominant methanogenic pathway from acetate in the absence of Methanosaetaceae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5138–5141. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00489-06

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kato, S., Haruta, S., Cui, Z. J., Ishii, M., and Igarashi, Y. (2005). Stable coexistence of five bacterial strains as a cellulose-degrading community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 7099–7106. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7099-7106.2005

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kato, S., Haruta, S., Cui, Z. J., Ishii, M., and Igarashi, Y. (2008). Network relationships of bacteria in a stable mixed culture. Microb. Ecol. 56, 403–411. doi: 10.1007/s00248-007-9357-4

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kato, S., Sasaki, K., Watanabe, K., Yumoto, I., and Kamagata, Y. (2014). Physiological and transcriptomic analyses of a thermophilic, aceticlastic methanogen Methanosaeta thermophila responding to ammonia stress. Microbes Environ. 29, 162–167. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME14021

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kato, S., and Watanabe, K. (2010). Ecological and evolutionary interactions in syntrophic methanogenic consortia. Microbes Environ. 25, 145–151. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME10122

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kerr, B., Riley, M. A., Feldman, M. W., and Bohannan, B. J. (2002). Local dispersal promotes biodiversity in a real-life game of rock-paper-scissors. Nature 418, 171–174. doi: 10.1038/nature00823

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Loreau, M., Naeem, S., Inchausti, P., Bengtsson, J., Grime, J. P., Hector, A.,et al. (2001). Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: current knowledge and future challenges. Science 294, 804–808. doi: 10.1126/science.1064088

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Lovley, D. R. (1985). Minimum threshold for hydrogen metabolism in methanogenic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49, 1530–1531.

Loy, A., Lehner, A., Lee, N., Adamczyk, J., Meier, H., Ernst, J.,et al. (2002). Oligonucleotide microarray for 16S rRNA gene-based detection of all recognized lineages of sulfate-reducing prokaryotes in the environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 5064–5081. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.10.5064-5081.2002

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Maloney, P. (1983). Relationship between phosphorylation potential and electrochemical H+ gradient during glycolysis in Streptococcus lactis. J. Bacteriol. 153, 1461–1470.

Mayumi, D., Dolfing, J., Sakata, S., Maeda, H., Miyagawa, Y., Ikarashi, M.,et al. (2013). Carbon dioxide concentration dictates alternative methanogenic pathways in oil reservoirs. Nat. Commun. 13:1998. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2998

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Mayumi, D., Mochimaru, H., Yoshioka, H., Sakata, S., Maeda, H., Miyagawa, Y.,et al. (2011). Evidence for syntrophic acetate oxidation coupled to hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis in the high-temperature petroleum reservoir of Yabase oil field (Japan). Environ. Microbiol. 13, 1995–2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02338.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

McHugh, S., Carton, M., Mahony, T., and O’Flaherty, V. (2003). Methanogenic population structure in a variety of anaerobic bioreactors. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 219, 297–304. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00055-7

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nahum, J. R., Harding, B. N., and Kerr, B. (2011). Evolution of restraint in a structured rock-paper-scissors community. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 10831–10838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100296108

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nauhaus, K., Boetius, A., Krüger, M., and Widdel, F. (2002). In vitro demonstration of anaerobic oxidation of methane coupled to sulphate reduction in sediment from a marine gas hydrate area. Environ. Microbiol. 4, 296–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00299.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Nüsslein, B., Chin, K. J., Eckert, W., and Conrad, R. (2001). Evidence for anaerobic syntrophic acetate oxidation during methane production in the profundal sediment of subtropical Lake Kinneret (Israel). Environ. Microbiol. 3, 460–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00215.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Pham, V. D., Hnatow, L. L., Zhang, S., Fallon, R. D., Jackson, S. C., Tomb, J. F.,et al. (2009). Characterizing microbial diversity in production water from an Alaskan mesothermic petroleum reservoir with two independent molecular methods. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 176–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01751.x

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Raskin, L., Poulsen, L. K., Noguera, D. R., Rittmann, B. E., and Stahl, D. A. (1994). Quantification of methanogenic groups in anaerobic biological reactors by oligonucleotide probe hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 1241–1248.

Schink, B. (1997). Energetics of syntrophic cooperation in methanogenic degradation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61, 262–280.

Sekiguchi, Y., Kamagata, Y., Syutsubo, K., Ohashi, A., Harada, H., and Nakamura, K. (1998). Phylogenetic diversity of mesophilic and thermophilic granular sludges determined by 16S rRNA gene analysis. Microbiology 144, 2655–2665. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-9-2655

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Shigematsu, T., Tang, Y., Kobayashi, T., Kawaguchi, H., Morimura, S., and Kida, K. (2004). Effect of dilution rate on metabolic pathway shift between aceticlastic and nonaceticlastic methanogenesis in chemostat cultivation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 4048–4052. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.7.4048-4052.2004

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Stock, D., Leslie, A. G. W., and Walker, J. E. (1999). Molecular architecture of the rotary motor in ATP synthase. Science 286, 1700–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1700

Thauer, R. K., Jungermann, K., and Decker, K. (1977). Energy conservation in chemotrophic anaerobic bacteria. Bacteriol. Rev. 41, 100–180.

Thauer, R. K., Kaster, A. K., Seedorf, H., Buckel, W., and Hedderich, R. (2008). Methanogenic archaea: ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1931

Pubmed Abstract | Pubmed Full Text | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Tran, Q. H., and Unden, G. (1998). Changes in the proton potential and the cellular energetics of Escherichia coli during growth by aerobic and anaerobic respiration or by fermentation. Eur. J. Biochem. 251, 538–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2510538.x

Keywords: model consortia, methanogenesis, acetate, thermodynamics, CO2 concentration

Citation: Kato S, Yoshida R, Yamaguchi T, Sato T, Yumoto I and Kamagata Y (2014) The effects of elevated CO2 concentration on competitive interaction between aceticlastic and syntrophic methanogenesis in a model microbial consortium. Front. Microbiol. 5:575. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00575

Received: 28 August 2014; Accepted: 13 October 2014;

Published online: 30 October 2014.

Edited by:

Shin Haruta, Tokyo Metropolitan University, JapanReviewed by:

Hans Karl Carlson, University of California, Berkeley, USACopyright © 2014 Kato, Yoshida, Yamaguchi, Sato, Yumoto and Kamagata. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Souichiro Kato, Bioproduction Research Institute, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, 2-17-2-1 Tsukisamu-Higashi, Toyohira-ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido 062-8517, Japan e-mail:cy5rYXRvdUBhaXN0LmdvLmpw

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.