- 1Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, University of California, Riverside, CA, USA

- 2Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA

- 3Department of Earth System Science, University of California, Irvine, CA, USA

- 4Department of Biology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Methane is an important anthropogenic greenhouse gas that is produced and consumed in soils by microorganisms responding to micro-environmental conditions. Current estimates show that soil consumption accounts for 5–15% of methane removed from the atmosphere on an annual basis. Recent variability in atmospheric methane concentrations has called into question the reliability of estimates of methane consumption and calls for novel approaches in order to predict future atmospheric methane trends. This review synthesizes the environmental and climatic factors influencing the consumption of methane from the atmosphere by non-wetland, terrestrial soil microorganisms. In particular, we focus on published efforts to connect community composition and diversity of methane-cycling microbial communities to observed rates of methane flux. We find abundant evidence for direct connections between shifts in the methane-cycling microbial community, due to climate and environmental changes, and observed methane flux levels. These responses vary by ecosystem and associated vegetation type. This information will be useful in process-based models of ecosystem methane flux responses to shifts in environmental and climatic parameters.

Introduction

Microorganisms have the potential to impact large-scale ecosystem functions that are relevant to the atmospheric composition of the Earth. In particular, microbial communities responsible for “narrow” processes, those that are phylogenetically and/or physiologically constrained, have been linked to corresponding process rates in nature (Schimel and Schaeffer, 2012). Schimel and Gulledge (1998) proposed studying methane-cycling microbial communities to demonstrate the connection between microbial community composition and ecosystem function. Environmental and climatic shifts can alter methane (CH4) flux profiles of soils (Bender and Conrad, 1992; Willison et al., 1995; Aronson and Helliker, 2010), likely through shifts in microbial community structure and function. Since the publication of Schimel and Gulledge (1998), numerous technological advances have allowed for the direct analysis of the connection between environmental and climatic factors and microbial community composition. In addition, our understanding of how different members of the microbial community contribute to soil CH4 flux has increased. In this review, we outline the responses of methane-cycling microbial community composition and abundance to environment and climate and how well these shifts correspond to changes in soil CH4 flux profiles.

The goal of this review is to highlight the current state of, and recent advances in, our understanding of CH4 consumption by microorganisms in terrestrial environments, as well as to point out areas where further study is needed. We hypothesized that net CH4 flux is correlated with the abundance and/or composition of methane-cycling microbes. We focus on non-wetland soils while touching on wetland and methanogen communities when relevant. To this end we discuss the main global changes that could impact methanotroph communities in particular. These changing environmental and climatic drivers include increased atmospheric CO2 and CH4 mixing ratios, increased temperature, changes in precipitation regimes, soil pH, and increased inorganic nitrogen (N) deposition to soil. In addition, we analyzed trends in CH4 fluxes by ecosystem, climatic zone, and vegetation type. In order to organize the body of knowledge on this topic, a meta-dataset was created from the literature, which is published along with this review as supplemental data. We believe that this dataset can assist in identifying future experimental directions as well as modeling efforts of the relationships between environmental and climatic changes, methane-cycling microbial communities, and soil CH4 fluxes.

Background to the Methane Cycle

Methane is the 2nd most important anthropogenic greenhouse gas, responsible for 20–30% of total greenhouse gas radiative forcing since the industrial revolution (IPCC, 2007). Methane is currently about 200 times less concentrated in the atmosphere than is carbon dioxide, but each molecule of CH4 is 25 times more potent in terms of heat-holding capacity (Lelieveld et al., 1998). Due to changes in human activity and land use, both carbon dioxide and CH4 began to increase around 150 years ago, as the industrial age began. Since that time, atmospheric CH4 concentrations have increased ~150%; from a pre-industrial mixing ratio of about 0.7 ppm to ~1.8 ppm currently (Maxfield et al., 2006; Degelmann et al., 2010).

Variability in atmospheric methane concentrations

Atmospheric CH4 concentrations became erratic and did not increase overall from 1997 until 2007, and then began increasing again around 2008 (Rigby et al., 2008) and continue to increase. The reason(s) for this shift is unknown, but several explanations have been proposed for the recent vagaries in atmospheric CH4. Decreases in wetland sources have been proposed to explain the lack of growth in late 1990s and early 2000s (Bousquet et al., 2006). The patching of natural gas pipelines in Russia has also been proposed as an explanation for the change in atmospheric CH4 concentrations, since these had become leaky after the collapse of the Soviet Union, losing an estimated 29–50 Tg CH4 yr−1 in the late 1980s–early 1990s (Reshetnikov et al., 2000), although these numbers have not been confirmed. A reduction in fossil fuel sources has also been implied as the cause by a study of ethane levels in Greenland and Antarctic firn (Aydin et al., 2011). Also proposed are variations in atmospheric concentration of OH− radicals (Rigby et al., 2008), yet there did not appear to be any increase in atmospheric CH4 destruction from these radicals recorded early in the duration of this decrease (Prinn, 2001) and there is an active debate over the reliability of past OH− measurements (Lelieveld et al., 2004). Other explanations have focused on reduced rice agriculture and other microbial emissions, confirmed by isotopic measurements and models (Kai et al., 2011).

The wide range of potential explanations for past trends in atmospheric CH4 indicates a lack of understanding of the interplay between biotic and abiotic controls on CH4 cycling. The underlying biology of the microbial responses to environmental variables is still poorly understood (do Carmo et al., 2006). The non-wetland, terrestrial ecosystem CH4 sink may be larger than suggested by top-down models suggest, possibly accounting for this missing sink, but this hypothesis can only be tested with further study of soil methanotroph community composition and response to climatic and other variables. Indeed, the same isotopic fractionation evidence suggesting that reduced microbial sources may be responsible for the decline in atmospheric CH4 growth (i.e., Kai et al., 2011) could also imply increased microbial consumption. Small advances in our understanding of any CH4 source or sink will greatly improve our ability to budget this important greenhouse gas.

Atmospheric methane sources and sinks

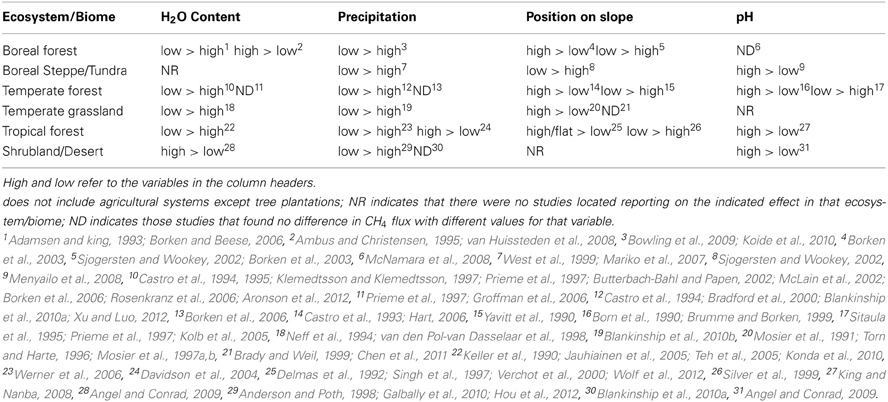

Methane sources are variable but their number and magnitude appear to be on the rise, while CH4 sinks are more uncertain. Total CH4 emissions were calculated by Lelieveld et al. (1998) to be 600 Tg CH4 yr−1, and by Wang et al. (2004) to be 506 Tg CH4 yr−1, with most recent estimates falling between 503 and 610 Tg CH4 yr−1 (IPCC, 2007). Figure 1 shows rough estimates of the relative contributions of CH4 sources and sinks, based on Lelieveld et al. (1998), Wang et al. (2004), and Conrad (2009). The largest global CH4 sources are natural and constructed wetlands, which contribute around 1/3 of annual emissions (IPCC, 2007). Anthropogenic sources, including rice paddies, domesticated animals, landfills, fossil fuel acquisition and burning, as well as biomass use for energy and agriculture, total at least 307 Tg CH4 yr−1, which could be over 60% of total emissions (Wang et al., 2004). There may be more sources than have been accounted for, as CH4 has also been found to be produced aerobically in the ocean (Karl et al., 2008). Trees themselves have also been linked to CH4 production (Keppler et al., 2006) through spontaneous UV-induced release and/or diffusion from dissolved soil CH4 in leaf water (Nisbet et al., 2009), although the overall contribution of that source has been shown to be negligible (Dueck et al., 2007).

Figure 1. Estimates of the relative contribution of sources and sinks to the global, annual methane budget.

There are indications that CH4 release from known sources was previously underestimated and has been on the rise with temperature increases in the last century. As high latitudes heat up in a generally warming climate, permafrost and accumulated ice thaw at accelerated rates (IPCC, 2007). This has caused the area of thermokarst lakes to increase, by at least double in the last 35 years (Walter et al., 2006). Advances in measurements in high latitude lakes show that most CH4 is released in rapid ebullition, a source type which was previously missed, and that the CH4 being released is Pleistocene in age, indicating the release of old carbon stores. This source accounts for at least 3.7 Tg CH4 yr−1 previously omitted from global estimates (Walter et al., 2006). Also associated with the warming in these higher latitudes is geological CH4 release from shallow hydrates, which may increase quickly as warming continues and could contribute up to 1.4 × 106 Tg CH4 (Shakhova et al., 2010). Further, increased temperatures in wetlands around the globe will likely lead to large increases in CH4 release, due to the sensitivity of methanogens to warming (Christensen et al., 2003).

The largest estimated CH4 sinks include tropospheric destruction (approximately 80–90% annually) and oxidation in other parts of the atmosphere (5–10%), according to Lelieveld et al. (1998). The most common figure for gross oxidation by soil in terrestrial environments is ~30 ± 15 Tg CH4 (IPCC, 2007), which corresponds to 2.5–7.5% of the estimated 600 Tg CH4 budget per year (Lelieveld et al., 1998). However, there has been some variation in this estimate, with a classic review of methanotrophy estimating soil consumption at 40–60 Tg yr−1 (Hanson and Hanson, 1996). Of all the CH4 sources and sinks, the biotic sink strength is the most responsive to variation in human activities (Dunfield et al., 2007).

The above figures for total consumption by the soil were not measured directly, but rather approximated by top-down, or inverse, global models (Wang et al., 2004). Inverse modeling solves for the sources and sinks based on observations of atmospheric chemical species over time and space while attempting to minimize uncertainty (Prinn, 2000). More recently, a meta-analysis by Dutaur and Verchot (2007) attempted to scale up from averages of local observations, resulting in an estimated consumption rate of ~34 Tg CH4 yr−1. Due to low consumption levels at atmospheric concentrations and high variability, the bottom-up approach of extrapolating from small-scale observations has had limited success in the past. However, the bottom-up approach should be applied more strenuously in the near future to take advantage of advances in technology and more widespread measurements. Future attempts to scale up from local observations should also account for the environmental factors and their impacts on microbial communities that govern CH4 flux.

Methane-Cycling Microorganisms

Soil exchange of CH4 with the atmosphere is regulated by two groups of microorganisms, known as methanogens and methanotrophs. The disparate environmental requirements of these two groups, particularly oxygen concentration, temperature, water content, and nutrient availability, determine the net CH4 flux of a given ecosystem. Methanogenic (CH4 producing) archaea, active mainly in anaerobic conditions, produce CH4 as a metabolic byproduct and are the main biological source of CH4 in natural systems, landfills, and agriculture. Methanotrophic (CH4 consuming) bacteria (sometimes referred to as CH4 oxidizing bacteria or MOB) are active mainly in aerobic conditions and derive energy and carbon from the oxidation of CH4 (Hanson and Hanson, 1996).

Methanogens

In natural systems, methanogens produce about 33% of emissions (Lelieveld et al., 1998). Most anthropogenic CH4 emissions from waste management and agriculture are also due in large part to the action of methanogens. Most methanogens are anaerobic archaea, and there exists a large variety of methanogens that loosely fit into two main, non-phylogenetic categories: those that are hydrogenotrophic, i.e., produce CH4 primarily using H2 and CO2; and those that are acetotrophic, i.e., use primarily acetate for metabolism that has been formed from previous decomposition activities (Le Mer and Roger, 2001). Most, if not all, known methanogens express an isozyme of methyl-coenzyme M reductase (MRT), of which the gene encoding the α subunit (mcrA) is present in most known methanogens (Shively et al., 2001).

Methanotrophs

The most common group of methane consumers is aerobic Methanotrophs (mostly methane oxidizing bacteria or MOB), which are generally found in oxic soils or microsites within anoxic soils. MOB are the only known biological sink for CH4, as key organisms within a soil microbial consortium that derives energy from CH4 conversion to carbon dioxide (Hanson and Hanson, 1996). Methanotrophs are a sub-group of the methylotrophs, which also contain methanol oxidizing bacteria (Kolb, 2009). There are 12 recognized genera of methanotrophs that are phylogenetically divided into type I (within the class Gamma proteobacteria) and type II (within the class Alpha proteobacteria; Mohanty et al., 2006). The key methanotrophic enzyme is CH4 monooxygenase (MMO), which occurs as both particulate (pMMO) and soluble (sMMO) forms. The pmoA gene encodes the α subunit of pMMO, and is included in the genome of all most known methanotrophic species (Dedysh et al., 2000). Methanotrophs are divided into at least two functionally distinct groups, the high affinity group that uses CH4 at very low concentrations, and the low affinity group that only uses CH4 at high concentrations (Bender and Conrad, 1992). Most culturable methanotrophs are low affinity, which tend to be located near source environments (Reay et al., 2005). In addition to the more common CH4 cyclers, a group of methanogen-like anaerobic CH4 oxidizing archaea (MOA) has been described (Hallam et al., 2003). These MOA contain mcrA genes (Hallam et al., 2003) and many are involved in a consortium that couples denitrification with anaerobic CH4 oxidation (Raghoebarsing et al., 2006).

Microbial Community Composition Impacts on Methane Flux

The capacity to produce or consume CH4 is distributed among relatively few microbial taxa that are phylogenetically distinct (Martiny et al., 2013). The narrow distributions of these traits imply that CH4 production and consumption rates may be more closely tied to microbial community composition and abundance than other biogeochemical processes (Schimel, 1995). Genes involved in methane-cycling are found in deep-branching microbial clades, similar to other complex microbial traits such as oxygenic photosynthesis and sulfate reduction (Martiny et al., 2013). By contrast, genes involved in heterotrophic processing of other carbon compounds are not highly conserved, and nearly all microbial taxa contribute to CO2 production in upland soils.

For methanogenesis, studies have found variation in the strength of the link between community structure and function. In a peat soil microcosms, methogenesis correlated positively with mcrA gene expression, which was a better predictor than gene abundance (Freitag and Prosser, 2009). The pathway of methane production shows a clear dependence on microbial composition, with acetoclastic methanogenesis dependent on the Methanosarcinaceae and CO2 reduction driven by groups such as the Methanobacteriales and Methanosaetaceae. These groups are sensitive to temperature, such that the CO2/H2 pathway becomes more dominant at higher temperatures (Fey and Conrad, 2000; Conrad et al., 2009). However, the temperature threshold for dominance varies from 15°C to 40°C across these studies, and both pathways are observed in peat soils with cooler average temperatures (Kotsyurbenko et al., 2004).

Other studies point to a more complex relationship between methane production and methanogen communities. Ramakrishnan et al. (2001) examined biogeographic patterns in methanogen communities across 11 rice field soils and found relatively similar microbial composition despite >10-fold differences in methane production rates. Similarly, Juottonen et al. (2008) observed relatively little change in methanogen abundance and composition across seasons in a boreal mire, but large variations in methane production that were likely due to increased substrate availability during winter. In a Siberian permafrost soil, Ganzert et al. (2007) found a shift from mesophilic to psychrophilic methanogens with depth, but no single group was clearly related to rates of methanogenesis, suggesting a degree of functional redundancy within methanogen communities.

As with methanogen communities, the link to functional rates is also variable for methanotroph communities. Some studies have found tight relationships between methane oxidation rates and community structure, often in the context of environmental change. In a temperate agricultural soil, long-term fertilization with ammonium nitrate reduced methanotroph abundance by >70%, resulting a similar decline in methane oxidation rates (Maxfield et al., 2008; Seghers et al., 2003a) observed a similar pattern that was associated with reductions in the abundance of low-affinity type I methanotrophs. Different groups of methanotrophs may show different responses to fertilization, as observed in rice field and forest soils where type II methanotrophs were more strongly inhibited by mineral N fertilization than type I methanotrophs (Mohanty et al., 2006). In contrast, organic fertilizer addition can increase methanotroph abundance and associated rates of methane oxidation (Seghers et al., 2005).

Gradient studies also suggest that variation in methanotroph abundance can correlate with functional rates. In a pine forest soil, methane oxidation rates across soil horizons were related to the abundance of a single PLFA marker identified with 13C stable isotope probing (Bengtson et al., 2009). Using a combination of molecular approaches and 13C tracers, Bodelier et al. (2013) found a tight link between methane consumption rates and the abundance of type 1 methanotrophs across a riparian floodplain. In contrast, studies in New Zealand have shown that type II methanotrophs are linked to higher methane oxidation rates associated with afforestation and reforestation (Singh et al., 2007; Nazaries et al., 2011). A similar pattern was observed across a broader gradient of vegetation types in Scotland, with increased type II methanotroph abundance, lower overall methanotroph diversity, and increased rates of methane consumption associated with forest vegetation (Nazaries et al., 2013).

Not all studies show such tight relationships between methanotroph communities and methane oxidation. Bárcena et al. (2011) found pmoA genes associated with high-affinity methanotrophs in a glacial forefield in Greenland, but detected almost no methane oxidation. Jaatinen et al. (2004) measured increased methane oxidation following boreal forest fire but no associated change in communities of methane-oxidizing bacteria. Conversely, Seghers et al. (2003b) found differences in methanotroph community composition but no substantial difference in methane oxidation in response to chronic herbicide treatment.

Differences in community composition that are not associated with differences in methane-cycling could indicate a degree of functional redundancy among methane-cycling microbes. However, such conclusions could be misleading. In some studies, more direct links between composition and function might have been observed if methanogen or methanotroph abundance had been measured. Studies using group-specific primers can identify within-group shifts in composition but not overall changes in abundance that may be more important for functional rates (Seghers et al., 2003a). For example, Menyailo et al. (2008) found that reductions in methanotroph-derived PLFA markers largely explained a 3-fold reduction in soil methane consumption following reforestation of a Siberian grassland. Despite the overall reduction in biomass, there were no apparent shifts in methanotroph community composition.

In addition, microbes that appear functionally redundant in one environment may show distinct responses when the environment changes. For example, different methanotroph communities may oxidize CH4 at similar rates in unfertilized soils (Seghers et al., 2003a), but communities dominated by type II methanogens could show much steeper declines in CH4 oxidation in response to N deposition (Mohanty et al., 2006).

Overall, many studies we reviewed support the idea that CH4 cycling depends on the composition and abundance of relatively narrow microbial groups. In addition, these studies demonstrate that environmental factors are important because they influence microbial communities. The abundances of methane-cycling microbes are often sensitive to environmental conditions such as temperature, precipitation, nutrient availability, CH4 concentration, and plant species (Fey and Conrad, 2000; Henckel et al., 2000; Horz et al., 2005; Liebner and Wagner, 2007; Maxfield et al., 2008; Tsutsumi et al., 2009). In some cases, these factors impact CH4 cycling though changes in microbial communities, but in other cases, environmental changes have important direct effects. For example, substrate availability and temperature both affect CH4 cycling rates, independent of changes in community composition (Wagner et al., 2005; Juottonen et al., 2008). Thus, even if CH4 cycling depends on narrow groups of methanogens and methanotrophs, the relationship between structure and function will always be subject to modification by environmental factors (Nazaries et al., 2011). This complexity will require models of the CH4 cycle that allow for feedbacks between microbial communities and environmental drivers.

Environmental Factors and the Methane Cycle

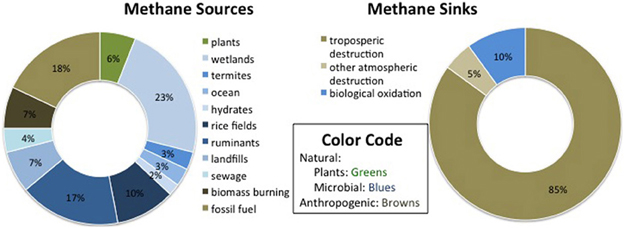

There is no ecosystem for which all of the potential direct or indirect effects of environmental variables on CH4 consumption of soil are understood, but many known interactions are summarized in Table 1. Conspicuously absent in Table 1 are any trends in tropical grasslands or savannahs, as there were no studies available testing environmental effects in these ecosystems to review. In general, the effect of higher soil moisture and precipitation is a decrease in the sink strength of the soil, however as Table 1 shows, even these impacts are not completely consistent. Other environmental variables that indirectly affect CH4 flux due to their influence on soil moisture and oxygen content are aspect and catena position, position on slope, soil type, and water holding capacity. Due to varying microbial preferences in terms of optimal pH, there is also some variation in response of CH4 flux to varying pH in the soil. Few general studies of distribution and activity of soil microbes as a whole have been done across catenas, slopes, or soil types, and many of those that have been done have not included methanotrophic or methanogenic organisms (Florinsky et al., 2004).

Methane Flux Responses to Increased Methane Concentrations

Although the average mixing ratio of CH4 at the Earth's surface has risen from around 0.7 ppm during pre-industrial times to about 1.8 currently, there has been little direct study of the impacts of rising atmospheric CH4 on the rate of consumption of CH4 by upland soils. Bender and Conrad (1992) determined that there were two kinetic optima for methanotrophy. There was a clear increase in the consumption of CH4 by the soil with increasing CH4 concentrations, indicating that the reaction is methane-limited at atmospheric oxygen levels (Bender and Conrad, 1992). However, they did not test consumption at CH4 concentrations between 2 and 6 ppm, since this range is thought to fall between the two Vmax values for methanotrophy. Yet, this range might be relevant for soil CH4 consumption rates under global change. Most other investigations of methanotrophy responses to CH4 concentration have used high concentrations, focused either on determining kinetic or potential rates of methanotrophy (Henckel et al., 2000; Tuomivirta et al., 2009; Tate et al., 2012).

Recently, one study showed that levels of CH4 only slightly elevated above ambient can lead to markedly increased CH4 consumption. Irvine et al. (2012) observed a strong direct relationship between ambient CH4 concentrations at the start of CH4 flux measurement and the rate of consumption in salt marsh soils. This result could indicate that increases in average ambient CH4 concentrations will lead to a measurable increase in atmospheric CH4 consumption across soils.

Methane Flux Responses to Increased CO2 Concentrations

Increases in CO2 can lead to increased methanogeny, both indirectly through greater biomass production increasing acetotrophic metabolism, and directly from CO2 stimulating hydrogenotrophic metabolism. In wetland areas the increased plant production due to elevated CO2 leads to greater CH4 release, likely due to acetotrophic metabolism (Dacey et al., 1994). Experiments in rice system soils have overwhelmingly agreed with these results (Ziska et al., 1998; Groot et al., 2003; Cheng et al., 2006). Whole soil and plant-facilitated emission of CH4 increased up to 69% in a wetland glasshouse experiment with elevated CO2 (Vann and Megonigal, 2003). However, plant facilitation may not add to this increase at all, as emissions facilitated by transport through wetland plants were not found to be changed by increased CO2 in a free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE) experiment (Baggs and Blum, 2004).

Though not as widely studied in non-wetland ecosystems, a similar trend was observed in two FACE studies performed in temperate forests, where heightened CO2 exposure resulted in an overall annual decrease in CH4 uptake of up to 30% (Phillips et al., 2001) and 25% (McLain et al., 2002). Another FACE study in a temperate grassland also showed decreased consumption with elevated CO2 (Ineson et al., 1998). It was hypothesized that these shifts were due to stimulation of methanogenesis by increased soil moisture in the lower soil layers (McLain et al., 2002; McLain and Ahmann, 2008; Dubbs and Whalen, 2010). However, elevated CO2 caused decreased overall bacterial counts and pmoA abundances (by qPCR and FISH) in a meadow soil (Kolb et al., 2005), indicating direct negative impacts on methanotrophy. Some studies have contradicted this trend, such as an open top chamber experiment in a shortgrass steppe, which showed a slight increase in net CH4 uptake that was not significant (Mosier et al., 2002). Similarly, elevated CO2 increased CH4 consumption in a grassland greenhouse study (Dijkstra et al., 2010). More analysis of the impact of elevated CO2 on CH4 flux in non-wetland terrestrial systems is needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn, specifically in the presence of other predicted global changes, such as warming.

Soil Moisture

Studies of precipitation and soil moisture content show correlations between wetter sites and decreased CH4 uptake or increased release (see Table 1), which is due in large part to the disparate environmental requirements of methanotrophs and methanogens. Throughfall exclusion in the Amazon basin caused CH4 consumption to more than quadruple compared to plots receiving natural precipitation levels (Davidson et al., 2004). Many studies have found that increased soil moisture content negatively influences CH4 consumption in ecosystems ranging from boreal, temperate, and tropical forests to shortgrass steppe, temperate farmland, and tundra (Adamsen and King, 1993; Castro et al., 1994; Klemedtsson and Klemedtsson, 1997; Epstein et al., 1998; Burke et al., 1999; West et al., 1999; McLain et al., 2002; Mosier et al., 2002).

However, there are intricacies that this generalization does not address. A dry tropical forest study showed that in the rainy season, CH4 consumption was inversely related to water content and precipitation (Singh et al., 1997). In the dry season, the trend was reversed, likely because all microbial activities are decreased, and the input of rain to severely dry soil leads to an increase in microbial activity, including methanotrophy. Boreal forest sites without peat show no significant difference in CH4 fluxes between inundated and dry soils. However, inundated peat soils released significantly more CH4 than dry peat soils from the boreal forest (Oelbermann and Schiff, 2010), indicating a vital role of water holding capacity of soil and surrounding vegetation.

Position in landscape, aspect, and catena

Factors such as position in the landscape, aspect, and catena impact CH4 flux indirectly, due to their impact on soil moisture retention. A mixed shrub, herb, and tree community showed higher CH4 consumption on North facing slopes (Burke et al., 1999). In a tundra study the results were mixed, with low snowmelt areas with high wind showing higher CH4 consumption on the North facing slope and areas with more snowmelt and protection having lower consumption on North facing slopes (West et al., 1999). A study in the boreal forest, using many different measures of CH4 flux and different tree communities showed that CH4 consumption was consistently greater on South facing slopes (Whalen et al., 1992). South facing slopes may have higher rates of evaporation than North facing slopes in the Northern Hemisphere, where all of these studies were located. This difference should lead to higher CH4 consumption on South facing slopes for more saturated soils, with the opposite effect for low water content soils, which does explain the mixed results seen in West et al. (1999). However, other factors may impact the effect of slope aspect, such as whether one slope receives higher precipitation due to orographic effects, as is known to occur in the Rocky Mountains of North America.

The impact of slope position is more variable, and more complete information is summarized in Table 1. For example, in the rainy season, dry tropical forest showed decreased CH4 uptake with low position on slope, with no trend in the dry season (Singh et al., 1997), which was also seen in boreal forest stands (Gulledge and Schimel, 2000). This result is likely due to prolonged increases in soil water content corresponding to poor drainage conditions and lower exposure to evaporation at low slope positions relative to hilltops. In Puerto Rican rainforest, the higher cloud forests release copious amounts of CH4, compared to the lower Tabanuco and Colorado forests which consume and release small amounts of CH4, respectively (Silver et al., 1999).

Soil type

Soil type exerts strong controls on the water holding capacity of soil, as well as the diffusion of gases into soil, both of which lead to pronounced effects on CH4 flux. Sandy soil (soil with larger particle size) has the lowest water holding capacity, followed by loam and then clay (Brady and Weil, 1999). The sand content of temperate grassland has been correlated with CH4 consumption rates, with sandy soil consuming more CH4 than loam, which in turn consumed more than clay (Born et al., 1990). Across terrestrial ecosystems, a recent meta-analysis performed by Dutaur and Verchot (2007) found that soil texture was one of the main factors correlated with CH4 fluxes, with coarser and medium-textured (loam) soils consuming more CH4 than fine (clay) soils (Dutaur and Verchot, 2007). Due to this recent meta-analysis, further discussion of the impact of soil type is limited in this review.

Soil Temperature

The methane-cycling microorganism response to temperature varies more than the response to changes in soil moisture. Insofar as temperature can lead to greater evapotranspiration, it may lead to decreased soil moisture, which would increase CH4 consumption. This trend was seen in multiple studies in temperate and boreal forests, which have found that higher observed soil temperatures correlate with greater uptake rates of CH4 (Castro et al., 1995; Klemedtsson and Klemedtsson, 1997; Bradford et al., 2001; Butterbach-Bahl and Papen, 2002; Rosenkranz et al., 2006). However, the enzymes involved in CH4 oxidation have variable optimum temperatures, with the average optimum temperature at 25°C (Hanson and Hanson, 1996). The enzymes involved in the degradation of organic matter that eventually results in methanogenesis have optima between 30 and 40°C (Le Mer and Roger, 2001). Similarly, temperature and precipitation have been shown to change the standing and ephemeral microbial community structure (Pritchard and Rogers, 2000), with varied consequences. A soil warming study using infrared heating, a method that provides a good approximation of future global warming (Aronson and McNulty, 2009), found that with increases in growing season temperature of up to 4.1°C there was no change in the CH4 flux of bog and fen mesocosms (Updegraff et al., 2001). However, higher temperatures (21°C vs. 14°C) caused significantly greater CH4 release from inundated peat soils from the boreal forest (Oelbermann and Schiff, 2010). Results were similar in a soil warming study within a grassland system, with increased heating causing lower CH4 uptake rates (Christensen et al., 1997).

Nitrogen and Fertilizer in the Methane Cycle

Global inorganic N input to non-wetland ecosystems from deposition, industry, and fertilizer use is projected to double from the 1990 levels by the year 2050 (Kroeze and Seitzinger, 1998). The effects of N on CH4 uptake in the soil environment are more complex than other environmental variables. Compared to natural forest and grassland, cropland and pasture consume less CH4 and show greater decreases in CH4 consumption rates with increased nitrogen additions (Aronson and Helliker, 2010). In general, the conversion of native lands to row-crop agriculture has been found to lead to a seven-fold reduction in both methanotroph diversity and CH4 consumption (Levine et al., 2011). The genetics and enzyme kinetics behind CH4 oxidation show tight evolutionary and functional linkages between the enzymes that enable CH4 and ammonia oxidation (Dunfield and Knowles, 1995). Methanotrophs and ammonia oxidizers are capable of switching substrates, which is a mechanism believed to be responsible for the inhibition of CH4 uptake by soil exposed to high concentrations of ammonia (Hanson and Hanson, 1996). In a rice paddy soil, CH4 oxidation and nitrification (i.e., ammonia oxidation) were inversely related in the presence of high N (Alam and Jia, 2012). In a wetland study by Baggs and Blum (2004), emissions facilitated by transport through plants were doubled with a four-fold increase in N deposition. However, laboratory experiments at elevated levels of ammonium showed that the inhibition of CH4 oxidation did not correspond to a shift in methanotroph communities (Bykova et al., 2007).

Methanotrophs demonstrate N limitation of CH4 uptake at low concentrations of available nitrogen relative to available CH4 in both N-limited wetlands (Bodelier et al., 2000) and upland soils (Aronson et al., 2012). A potential mechanism for this observed stimulation of CH4 oxidation with added inorganic N, in N-limited systems, was proposed by Bodelier and Laanbroek (2004) to be the N-fixation pathway found in a subset of methanotrophs, specifically the nitrogenase pathway found in types II and X methanotrophs (Hanson and Hanson, 1996). Type X methanotrophs are closely related to type I, but share some metabolic similarities with type II (Macalady et al., 2002). Thus, it has been put forward that in N-limited conditions, methanotrophy is limited by the energy requirement of N fixation (Henckel et al., 2000). Evidence for stimulation of methanotrophy by addition of low levels of inorganic N has been found in some non-wetland terrestrial systems (Aronson and Helliker, 2010). In general, soil drainage condition may indicate whether N stimulates methanotrophy, inhibits it, or does not impact the CH4 cycle at all (Aronson et al., 2013).

Soil pH

Methanotrophs are more sensitive to acidic environments than are methanogens, although they are more tolerant of variations in pH through time (Le Mer and Roger, 2001). With the exception of variable responses to pH in the temperate forest, there was a general trend of increasing CH4 consumption with higher pH (Table 1). There was also no clear trend in the boreal forest studied (McNamara et al., 2008).

Ecosystem and Vegetation Effects on Methane Uptake

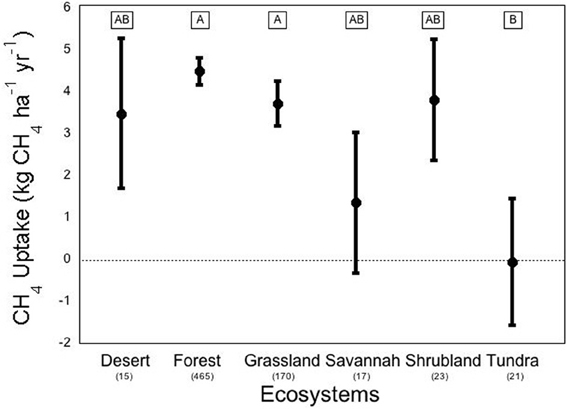

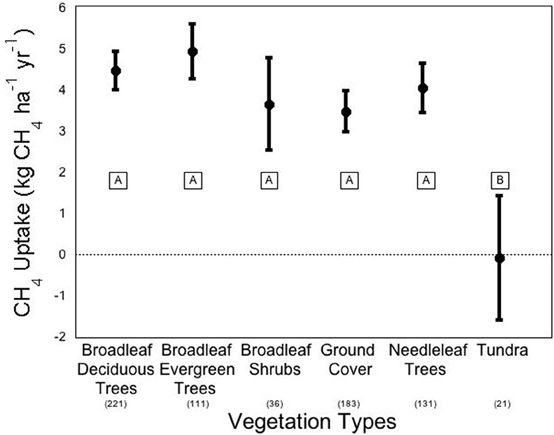

We conducted a meta-analysis to determine ecosystem and vegetation impacts on CH4 uptake in upland soils (methods in Appendix A, database in Appendix B). Across the ecosystems included in our meta-analysis, there exists a high variability in CH4 flux by ecosystem type (Figure 2). The One-Way ANOVA performed across studies by ecosystem type found that there was a significant difference between ecosystem types (p < 0.031). Means comparisons using Student's t revealed that forests and grasslands consumed more CH4 than tundra, with the other ecosystems not different from each other. In addition, vegetation type (Figure 3), was significant by ANOVA (p < 0.044). Means comparisons showed that tundra, which released methane on average, differed significantly from all other vegetation types, which consumed methane.

Figure 2. Methane flux by ecosystem. Negative numbers indicate net release of methane by the soil. Averages are expressed bounded by standard errors of the means. The number of studies included in each average is listed in parentheses under each ecosystem type. Means with the same letter are not significantly different (Student's t-test).

Figure 3. Methane flux by vegetation types. Negative numbers indicate net release of methane by the soil. Averages are expressed bounded by standard errors of the means. The number of studies included in each average is listed in parentheses under each vegetation type. Means with the same letter are not significantly different (Student's t-test).

On average, forest systems show the greatest CH4 consumption capability of any ecosystem, at an average of about −4.50 ± 0.32 kg ha−1 yr−1. The variation between forest observations is great, even though the standard error is relatively low, due to the fact that the number of studies included in the database from forests is an order of magnitude greater than most other ecosystems. This rate can be much higher; a study of a New Zealand pine forest found an overall uptake of CH4 at an annual rate of –12.1 kg ha−1 yr−1 (Tate et al., 2006). At the extreme end, an early CH4 uptake study in a British mixed-temperate forest on a single day found an uptake rate that would scale to –165 kg ha−1 yr−1 (Willison et al., 1995). But not all forests consume CH4 overall; a study of the CH4 budget of a black spruce forest in Germany found an average CH4 release of 54.5 kg ha−1 yr−1 (Fiedler et al., 2005). Tundra ecosystems (including “alpine” and “subarctic” tundra) on average were found to release CH4 at a rate of 0.035 kg ha−1 yr−1. Tundra also displayed extremely high variation in uptake rates across various environmental conditions, which may be due to ebullition; the release of large amounts of CH4 in bubbles from clathrate associations deep below the soil or water column (Shakhova et al., 2010). Vegetation height has also been found to be a good indicator of CH4 release in varied wet tundra sites (von Fischer et al., 2010). Deserts displayed the greatest variation, with mean ± standard error of desert flux found to be 3.49 ± 1.79 kg ha−1 yr−1 across 9 studies, which may be due to more extreme responses to precipitation pulses. Alternately, this variation may be due fact that deserts over natural gas deposits have been shown to be CH4 sources (Etiope and Klusman, 2010).

Vegetation Effects

Robust differences in CH4 fluxes appear when separated by vegetation type (Figure 3; ANOVA p = 0.009). Individual plant species effects on CH4 flux can be substantial, but most effects have been reported in wetland species. The most common species effects occur in some wetland plants that facilitate CH4 entering and leaving the soil or sediment. For an example with the sedge plant type/functional type, there is a clear difference between Carex scopulorum, which allows the emission of CH4, and Kobresia myosuroides, which allowed the consumption of CH4 (West et al., 1999). Confounding may frequently emerge in most experiments that report on the plant species and functional type causes of uptake because the effects of plant species are difficult to tease apart from the effects of environmental variables, which may in turn predict plant species colonization. For example, in West et al. (1999), the variation in amount of snowmelt received during the snow-free months in the alpine tundra predicted plant species dominance differences. The CH4 uptake rate in these sites varied, but whether the variation was due to a species or environmental effect is ambiguous (West et al., 1999).

Generally when plant effects are observed, it is not specific species but plant functional type differences that are of interest, with the soil around trees associated with higher CH4 consumption than shrubs, grasses, and sedges. Across studies, deciduous forests have higher CH4 uptake rates than do coniferous forests (Degelmann et al., 2010), which is likely related to pH impacts. In the meta-analysis, we found broadleaf deciduous trees to consume −4.51 kg CH4 ha−1 yr−1 compared to –4.08 kg CH4 ha−1 yr−1 in needleleaf trees, however, this difference was not significant (Figure 3). There was also one study that directly tested the impact of tree proximity on CH4 uptake rate and found that there is greater net uptake by soils that are closer to deciduous trees and further from coniferous trees (Butterbach-Bahl et al., 2002). There has also been an observed effect of grass functional diversity on CH4 uptake in shortgrass steppe soils (Epstein et al., 1998). In clay soils, a mixture of C3 and C4 grasses appeared to consume more CH4 than either grass type alone, though these results were not significant at the 5% level. In sandy clay soils, a different effect was observed with C4 plants significantly increasing uptake of CH4 compared to C3. Mixed grasses fell between the grass types and did not differ significantly from either C3 or C4 uptake (Epstein et al., 1998).

Disturbance, Burning, and Plant Succession

There has been limited study of the impacts of burning, grazing, plant removal, and other disturbances on CH4 uptake by soils. There are no clear trends in a handful of studies on the effects of burning on CH4 flux performed across multiple ecosystems. In tropical forests and temperate grasslands, burning increased consumption of CH4 (Tate and Striegl, 1993; Poth et al., 1995). Burning results in vegetative cover removal that could increase the sunlight reaching the soil, therefore allowing for a lower water filled pore space and more consumption of CH4. However, in tropical savannas the impact of burning was decreased consumption (Prieme and Christensen, 1999). In boreal forests and Mediterranean shrublands, the response to fire was mixed or there was no change at all (Gulledge et al., 1997; Anderson and Poth, 1998; Castaldi and Fierro, 2005).

The impact of non-fire vegetative removal has also been mixed across ecosystems. Grazing has been shown to increase CH4 uptake in the boreal steppe (Geng et al., 2010). In temperate and tropical grasslands grazing generally decreased consumption (Zhou et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2010, 2011; Wang et al., 2012). Clipping was found to increase CH4 consumption in tropical savannah (Sanhueza and Donoso, 2006). Thinning of the trees decreased CH4 consumption in one temperate forest (Dannenmann et al., 2007), but not another (Wu et al., 2011). Clear-cutting reduced consumption in the boreal forest (Saari et al., 2004) and temperate forest (Wu et al., 2011).

Changes in CH4 consumption are often observed during ecological succession following disturbance. Within forests, the climax (i.e., virgin or old-growth) vegetation is most often found to consume more CH4 than early successional stages This trend was found in two temperate forest studies of deciduous (Hudgens and Yavitt, 1997) and mixed deciduous and coniferous stands of various ages since disturbance (Brumme and Borken, 1999). Within tropical forests, old-growth forest was found to consume more CH4 (Keller and Reiners, 1994; Verchot et al., 2000; Veldkamp et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008). MacDonald et al. (1999) had mixed results and MacDonald et al. (1998) and Goreau and Mello (1985) found that secondary forest consumed more CH4 than old-growth forest. (Kruse and Iversen, 1995) found that in temperate grasslands, post-plow secondary growth soils consumed more CH4 than both bare plowed soil and natural heathland. They also found that oaks invading the grassland consumed resulted in more CH4 consumption than the nature heathland or secondary grasses, and that old-growth and established oak stands consumed even more CH4 (Kruse and Iversen, 1995). In Mediterranean shrublands, old growth shrubs consumed more CH4 than early and mid-succession (Price et al., 2010).

Conclusions

Methane-cycling microorganisms in soils have the potential to impact the atmospheric composition of the Earth. As a narrow process, we found the composition of the microbial communities responsible for CH4 consumption and production have been linked to corresponding process rates in nature, as was proposed by Schimel and Gulledge (1998). We hypothesized that net CH4 flux would be correlated with the abundance and/or composition of methane-cycling microbes. In fact we found prolific, although not entirely consistent, evidence that the impacts of environmental and climate drivers on net CH4 flux are the result of changes in the methane-cycling microbial community. However, we found fewer studies that linked these changes to overall abundance of methanotrophs and/or methanogens, or specific phylogenetic lineages within these groups. This is an area of study ripe for investigation, and we believe that coupled with the knowledge of the impact of shifts in community composition, this data on abundance could complete the picture of the role of microorganisms in the global CH4 cycle.

Combined with information on microbial community impacts on CH4 flux, the dataset created for this review can assist in future modeling efforts. In particular, it demonstrates relationships between environmental and climatic changes, methane-cycling microbial communities, and soil CH4 fluxes. Process-based and ecosystem-specific models of CH4 flux are necessary to predict ecosystem CH4 fluxes in response to environmental and climatic changes. In order to create these models, certain ecosystems deserve further study, either because they consume large amounts of CH4 or because they are understudied. In particular, attention should be focused tropical grasslands and savannahs. Secondarily, some attention should be paid to the impact of pH in boreal forest and soil moisture content in boreal steppe/tundra, as well as the impacts of temperature across the boreal landscape, as research on these topics is lacking and most warming is expected to occur in high latitudes where these ecosystems are prevalent (IPCC, 2007).

Finally, it is important to decrease the uncertainty regarding CH4 sources and sinks in order to improve predictions of future global warming. We now have the tools necessary to answer questions about recent fluctuations in the CH4 growth rate in the atmosphere and predict the CH4 budget. The increasing use of eddy covariance techniques for regional scale estimates of CH4 fluxes can assist these global inventories, but should be paired with chamber-based flux measurements to account for the effects of environmental variation. Small-scale process-based models, global inventories, and global inverse models have all approached this issue with limited success. The next generation of models must use process-based and microbial community knowledge to account for seasonal and inter-annual variation in global CH4 budgets.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Air and Waste Management Association's Air Pollution Education and Research Grant, the NASA Graduate Student Researchers Program, as well as the NOAA Climate and Global Change Postdoctoral Fellowship for supporting this research.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/Terrestrial_Microbiology/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00225/abstract

References

Adamsen, A. P. S., and King, G. M. (1993). Methane consumption in temperate and sub-arctic forest soils – rates, vertical zonation, and responses to water and nitrogen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59, 485–490.

Alam, M. S., and Jia, Z. (2012). Inhibition of methane oxidation by nitrogenous fertilizers in a paddy soil. Front. Microbiol. 3:246. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00246

Ambus, P., and Christensen, S. (1995). Spatial and seasonal nitrous oxide and methane fluxes in Danish forest-ecosystems, grassland-ecosystems, and agroecosystems. J. Environ. Qual. 24, 993–1001. doi: 10.2134/jeq1995.00472425002400050031x

Anderson, I. C., and Poth, M. A. (1998). Controls on fluxes of trace gases from brazilian cerrado soils. J. Environ. Qual. 27, 1117–1124. doi: 10.2134/jeq1998.00472425002700050017x

Angel, R., and Conrad, R. (2009). In situ measurement of methane fluxes and analysis of transcribed particulate methane monooxygenase in desert soils. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 2598–2610. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01984.x

Aronson, E. L., Dubinsky, E. A., and Helliker, B. R. (2013). Effects of nitrogen addition on soil microbial diversity and methane cycling capacity depend on drainage conditions in a pine forest soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 62, 119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2013.03.005

Aronson, E. L., and Helliker, B. R. (2010). Methane flux in non-wetland soils in response to nitrogen addition: a meta-analysis. Ecology 91, 3242–3251. doi: 10.1890/09-2185.1

Aronson, E. L., and McNulty, S. G. (2009). Appropriate experimental ecosystem warming methods by ecosystem, objective, and practicality. Agricult. Forest Meteorol. 149, 1791–1799. doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2009.06.007

Aronson, E. L., Vann, D. R., and Helliker, B. R. (2012). Methane flux response to nitrogen amendment in an upland pine forest soil and riparian zone. J. Geophys. Res. 117, G03012. doi: 10.1029/2012JG001962

Aydin, M., Verhulst, K. R., Saltzman, E. S., Battle, M. O., Montzka, S. A., Blake, D. R., et al. (2011). Recent decreases in fossil-fuel emissions of ethane and methane derived from firn air. Nature 476, 198–201. doi: 10.1038/nature10352

Baggs, E. M., and Blum, H. (2004). CH4 oxidation and emissions of CH4 and N2O from Lolium perenne swards under elevated atmospheric CO2. Soil Biol. Biochem. 36, 713–723. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2004.01.008

Bárcena, T. G., Finster, K. W., and Yde, J. C. (2011). Spatial patterns of soil development, methane oxidation, and methanotrophic diversity along a receding glacier forefield, southeast greenland. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 43, 178–188. doi: 10.1657/1938-4246-43.2.178

Bender, M., and Conrad, R. (1992). Kinetics of CH4 oxidation in oxic soils exposed to ambient air or high CH4 mixing ratios. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 101, 261–270. doi: 10.1016/0168-6496(92)90043-S

Bengtson, P., Basiliko, N., Dumont, M. G., Hills, M., Murrell, J. C., Roy, R., et al. (2009). Links between methanotroph community composition and CH 4oxidation in a pine forest soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 70, 356–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00751.x

Blankinship, J. C., Brown, J. R., Dijkstra, P., Allwright, M. C., and Hungate, B. A. (2010a). Response of terrestrial CH4 uptake to interactive changes in precipitation and temperature along a climatic gradient. Ecosystems 13, 1157–1170. doi: 10.1007/s10021-010-9391-9

Blankinship, J. C., Brown, J. R., Dijkstra, P., and Hungate, B. A. (2010b). Effects of interactive global changes on methane uptake in an annual grassland. J. Geophys. Res. 115, G02008, doi:10.1029/2009JG001097

Bodelier, P. L. E., and Laanbroek, H. J. (2004). Nitrogen as a regulatory factor of methane oxidation in soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 47, 265–277. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6496(03)00304-0

Bodelier, P. L. E., Meima-Franke, M., Hordijk, C. A., Steenbergh, A. K., Hefting, M. M., Bodrossy, L., et al. (2013). Microbial minorities modulate methane consumption through niche partitioning. ISME J. 2013, 1–15.

Bodelier, P. L. E., Roslev, P., Henckel, T., and Frenzel, P. (2000). Stimulation by ammonium-based fertilizers of methane oxidation in soil around rice roots. Nature 403, 421–424. doi: 10.1038/35000193

Borken, W., and Beese, F. (2006). Methane and nitrous oxide fluxes of soils in pure and mixed stands of European beech and Norway spruce. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 57, 617–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2389.2005.00752.x

Borken, W., Davidson, E. A., Savage, K., Sundquist, E. T., and Steudler, P. (2006). Effect of summer throughfall exclusion, summer drought, and winter snow cover on methane fluxes in a temperate forest soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 38, 1388–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.10.011

Borken, W., Xu, Y. J., and Beese, F. (2003). Conversion of hardwood forests to spruce and pine plantations strongly reduced soil methane sink in Germany. Glob. Change Biol. 9, 956–966. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00631.x

Born, M., Dorr, H., and Levin, I. (1990). Methane consumption in aerated soils of the temperate zone. Tellus 42, 2–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0889.1990.00002.x

Bousquet, P., Ciais, P., Miller, J. B., Dlugokencky, E. J., Hauglustaine, D. A., Prigent, C., et al. (2006). Contribution of anthropogenic and natural sources to atmospheric methane variability. Nature 443, 439–443. doi: 10.1038/nature05132

Bowling, D. R., Miller, J. B., Rhodes, M. E., Burns, S. P., Monson, R. K., and Baer, D. (2009). Soil, plant, and transport influences on methane in a subalpine forest under high ultraviolet irradiance. Biogeosciences 6, 1311–1324. doi: 10.5194/bg-6-1311-2009

Bradford, M. A., Ineson, P., Wookey, P. A., and Lappin-Scott, H. M. (2000). Soil CH4 oxidation: response to forest clearcutting and thinning. Soil Biol. Biochem. 32, 1035–1038. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00007-9

Bradford, M. A., Wookey, P. A., Ineson, P., and Lappin-Scott, H. M. (2001). Controlling factors and effects of chronic nitrogen and sulphur deposition on methane oxidation in a temperate forest soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 33, 93–102. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00118-8

Brady, N. C., and Weil, R. R. (1999). The Nature and Properties of Soils, 12th Edn. Toronto, ON: Macmillan.

Brumme, R., and Borken, W. (1999). Site variation in methane oxidation as affected by atmospheric deposition and type of temperate forest ecosystem. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 13, 493–501. doi: 10.1029/1998GB900017

Brummell, M. E., Farrell, R. E., and Siciliano, S. D. (2012). Greenhouse gas soil production and surface fluxes at a high arctic polar oasis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 52, 1–12.

Burke, R. A., Meyer, J. L., Cruse, J. M., Birkhead, K. M., and Paul, M. J. (1999). Soil-atmosphere exchange of methane in adjacent cultivated and floodplain forest soils. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 104, 8161–8171. doi: 10.1029/1999JD900015

Butterbach-Bahl, K., and Papen, H. (2002). Four years continuous record of CH4-exchange between the atmosphere and untreated and limed soil of a N-saturated spruce and beech forest ecosystem in Germany. Plant Soil 240, 77–90. doi: 10.1023/A:1015856617553

Butterbach-Bahl, K., Rothe, A., and Papen, H. (2002). Effect of tree distance on N2O and CH4-fluxes from soils in temperate forest ecosystems. Plant Soil 240, 91–103. doi: 10.1023/A:1015828701885

Bykova, S., Boeckx, P., Kravchenko, I., Galchenko, V., and Cleemput, O. V. (2007). Response of CH4 oxidation and methanotrophic diversity to NH4 and CH4 mixing ratios. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 43, 341–348. doi: 10.1007/s00374-006-0114-5

Castaldi, S., and Fierro, A. (2005). Soil-atmosphere methane exchange in undisturbed and burned Mediterranean shrubland of southern Italy. Ecosystems 8, 182–190. doi: 10.1007/s10021-004-0093-z

Castro, M. S., Melillo, J. M., Steudler, P. A., and Chapman, J. W. (1994). Soil-moisture as a predictor of methane uptake by temperate forest soils. Can. J. For. Res. 24, 1805–1810. doi: 10.1139/x94-233

Castro, M. S., Steudler, P. A., Melillo, J. M., Aber, J. D., and Bowden, R. D. (1995). Factors controlling atmospheric methane consumption by temperate forest soils. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 9, 1–10. doi: 10.1029/94GB02651

Castro, M. S., Steudler, P. A., Melillo, J. M., Aber, J. D., and Millham, S. (1993). Exchange of N2O and CH4 between the atmosphere and soils in Spruce-Fir forests in the Northeastern United-States. Biogeochemistry 18, 119–135. doi: 10.1007/BF00003273

Chen, W., Wolf, B., Zheng, X., Yao, Z., Butterbach-Bahl, K., Brüggemann, N., et al. (2011). Annual methane uptake by temperate semiarid steppes as regulated by stocking rates, aboveground plant biomass and topsoil air permeability. Glob. Change Biol. 17, 2803–2816. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02444.x

Chen, W. W., Wolf, B., Yao, Z. S., Bruggemann, N., Butterbach-Bahl, K., Liu, C. Y., et al. (2010). Annual methane uptake by typical semiarid steppe in Inner Mongolia. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 115, D15108.

Cheng, W. G., Yagi, K., Sakai, H., and Kobayashi, K. (2006). Effects of elevated atmospheric CO2 concentrations on CH4 and N2O emission from rice soil: An experiment in controlled-environment chambers. Biogeochemistry 77, 351–373. doi: 10.1007/s10533-005-1534-2

Christensen, T. R., Ekberg, A., Strom, L., Mastepanov, M., Panikov, N., Oquist, M., et al. (2003). Factors controlling large scale variations in methane emissions from wetlands. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30. doi: 10.1029/2002GL016848

Christensen, T. R., Michelsen, A., Jonasson, S., and Schmidt, I. K. (1997). Carbon dioxide and methane exchange of a subarctic heath in response to climate change related environmental manipulations. Oikos 79, 34–44. doi: 10.2307/3546087

Conrad, R. (2009). The global methane cycle: recent advances in understanding the microbial processes involved. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1, 285–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00038.x

Conrad, R., Klose, M., and Noll, M. (2009). Functional and structural response of the methanogenic microbial community in rice field soil to temperature change. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 1844–1853. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01909.x

Dacey, J. W. H., Drake, B. G., and Klug, M. J. (1994). Stimulation of methane emission by carbon-dioxide enrichment of marsh vegetation. Nature 370, 47–49. doi: 10.1038/370047a0

Dannenmann, M., Gasche, R., Ledebuhr, A., Holst, T., Mayer, H., and Papen, H. (2007). The effect of forest management on trace gas exchange at the pedosphere-atmosphere interface in beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) forests stocking on calcareous soils. Eur. J. For. Res. 126, 331–346. doi: 10.1007/s10342-006-0153-3

Davidson, E. A., Ishida, F. Y., and Nepstad, D. C. (2004). Effects of an experimental drought on soil emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and nitric oxide in a moist tropical forest. Glob. Change Biol. 10, 718–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00762.x

Dedysh, S. N., Liesack, W., Khmelenina, V. N., Suzina, N. E., Trotsenko, Y. A., Semrau, J. D., et al. (2000). Methylocella palustris gen. nov., sp nov., a new methane-oxidizing acidophilic bacterium from peat bags, representing a novel subtype of serine-pathway methanotrophs. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50, 955–969. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-3-955

Degelmann, D. M., Borken, W., Drake, H. L., and Kolb, S. (2010). Different Atmospheric Methane-Oxidizing Communities in European Beech and Norway Spruce Soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 3228–3235. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02730-09

Delmas, R. A., Servant, J., Tathy, J. P., Cros, B., and Labat, M. (1992). Sources and sinks of methane and carbon-dioxide exchanges in mountain forest in Equatorial Africa. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 97, 6169–6179. doi: 10.1029/90JD02575

Dijkstra, F. A., Morgan, J. A., LeCain, D. R., and Follett, R. F. (2010). Microbially mediated CH4 consumption and N2O emission is affected by elevated CO2, soil water content, and composition of semi-arid grassland species. Plant Soil 329, 269–281. doi: 10.1007/s11104-009-0152-5

do Carmo, J. B., Keller, M., Dias, J. D., de Camargo, P. B., and Crill, P. (2006). A source of methane from upland forests in the Brazilian Amazon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L04809. doi: 10.1029/2005GL025436

Dubbs, L. L., and Whalen, S. C. (2010). Reduced net atmospheric CH4 consumption is a sustained response to elevated CO2 in a temperate forest. Biol. Fert. Soils 46, 597–606. doi: 10.1007/s00374-010-0467-7

Dueck, T. A., de Visser, R., Poorter, H., Persijn, S., Gorissen, A., de Visser, W., et al. (2007). No evidence for substantial aerobic methane emission by terrestrial plants: a C-13-labelling approach. New Phytol. 175, 29–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02103.x

Dunfield, P., and Knowles, R. (1995). Kinetics of inhibition of methane oxidation by nitrate, nitrite, and ammonium in a humisol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 3129–3135.

Dunfield, P. F., Yuryev, A., Senin, P., Smirnova, A. V., Stott, M. B., Hou, S. B., et al. (2007). Methane oxidation by an extremely acidophilic bacterium of the phylum Verrucomicrobia. Nature 450, U879–U818. doi: 10.1038/nature06411

Dutaur, L., and Verchot, L. V. (2007). A global inventory of the soil CH4 sink. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 21, GB4013. doi: 10.1029/2006GB002734

Epstein, H. E., Burke, I. C., Mosier, A. R., and Hutchinson, G. L. (1998). Plant functional type effects on trace gas fluxes in the shortgrass steppe. Biogeochemistry 42, 145–168. doi: 10.1023/A:1005959001235

Etiope, G., and Klusman, R. W. (2010). Methane microseepage in drylands: soil is not always a CH 4sink. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 7, 31–38. doi: 10.1080/19438151003621359

Fey, A., and Conrad, R. (2000). Effect of Temperature on Carbon and Electron Flow and on the Archaeal Community in Methanogenic Rice Field Soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 4790–4797. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.11.4790-4797.2000

Fiedler, S., Holl, B. S., and Jungkunst, H. F. (2005). Methane budget of a Black Forest spruce ecosystem considering soil pattern. Biogeochemistry 76, 1–20. doi: 10.1007/s10533-005-5551-y

Florinsky, I. V., McMahon, S., and Burton, D. L. (2004). Topographic control of soil microbial activity: a case study of denitrifiers. Geoderma 119, 33–53. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7061(03)00224-6

Freitag, T. E., and Prosser, J. I. (2009). Correlation of Methane Production and Functional Gene Transcriptional Activity in a Peat Soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 6679–6687. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01021-09

Ganzert, L., Jurgens, G., Mãnster, U., and Wagner, D. (2007). Methanogenic communities in permafrost-affected soils of the Laptev Sea coast, Siberian Arctic, characterized by 16S rRNA gene fingerprints. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 59, 476–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00205.x

Galbally, I., Meyer, C. P., Wang, Y. P., and Kirstine, W. (2010). Soil-atmosphere exchange of CH4, CO, N2O and NOx and the effects of land-use change in the semiarid Mallee system in Southeastern Australia. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 2407–2419.

Geng, Y., Luo, G., and Yuan, G. (2010). CH4 uptake flux of Leymus chinensis steppe during rapid growth season in Inner Mongolia, China. Sci. China Earth Sci. 53, 977–983. doi: 10.1007/s11430-010-3082-4

Goreau, T. J., and Mello, W. Z. (1985). “Effects of deforestation on sources and sinks of atmospheric CO2, N2O, and CH4 from central Amazonian soils and biota during the dry season,” in Workshop on Biogeochemistry of Tropical Rain Forests. Piracicaba.

Groffman, P. M., Hardy, J. P., Driscoll, C. T., and Fahey, T. J. (2006). Snow depth, soil freezing, and fluxes of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane in a northern hardwood forest. Glob. Change Biol. 12, 1748–1760. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01194.x

Groot, T. T., van Bodegom, P. M., Harren, F. J. M., and Meijer, H. A. J. (2003). Quantification of methane oxidation in the rice rhizosphere using C-13-labelled methane. Biogeochemistry 64, 355–372. doi: 10.1023/A:1024921714852

Gulledge, J., Doyle, A. P., and Schimel, J. P. (1997). Different NH4+-inhibition patterns of soil CH4 consumption: A result of distinct CH4-oxidizer populations across sites? Soil Biol. Biochem. 29, 13–21. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(96)00265-9

Gulledge, J., and Schimel, J. P. (2000). Controls on soil carbon dioxide and methane fluxes in a variety of taiga forest stands in interior Alaska. Ecosystems 3, 269–282. doi: 10.1007/s100210000025

Hallam, S. J., Girguis, P. R., Preston, C. M., Richardson, P. M., and DeLong, E. F. (2003). Identification of methyl coenzyme M reductase A (mcrA) genes associated with methane-oxidizing archaea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 5483–5491. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.9.5483-5491.2003

Hart, S. C. (2006). Potential impacts of climate change on nitrogen transformations and greenhouse gas fluxes in forests: a soil transfer study. Glob. Change Biol. 12, 1032–1046. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01159.x

Henckel, T., Jackel, U., Schnell, S., and Conrad, R. (2000). Molecular analyses of novel methanotrophic communities in forest soil that oxidize atmospheric methane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 1801–1808. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.5.1801-1808.2000

Horz, H. P., Rich, V., Avrahami, S., and Bohannan, B. J. M. (2005). Methane-oxidizing bacteria in a california upland grassland soil: diversity and response to simulated global change. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 2642–2652. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.5.2642-2652.2005

Hou, L.-Y., Wang, Z.-P., Wang, J.-M., Wang, B., Zhou, S.-B., and Li, L.-H. (2012). Growing season in situ uptake of atmospheric methane by desert soils in a semiarid region of northern China. Geoderma 189–190, 415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.geoderma.2012.05.012

Hudgens, D. E., and Yavitt, J. B. (1997). Land-use effects on soil methane and carbon dioxide fluxes in forests near Ithaca, New York. Ecoscience 4, 214–222.

Hutchinson, G. L., and Mosier, A. R. (2002). Improved Soil Cover Method for Field Measurement of Nitrous Oxide Fluxes. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 45, 311–316.

Ineson, P., Benham, D. G., Poskitt, J., Harrison, A. F., Taylor, K., and Woods, C. (1998). Effects of climate change on nitrogen dynamics in upland soils. 2. A soil warming study. Glob. Change Biol. 4, 153–161. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.1998.00119.x

IPCC (2007). The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, eds S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K. B. Averyt, M. Tignor, H. L. Miller, (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press).

Irvine, I. C., Vivanco, L., Bentley, P. N., and Martiny, J. B. H. (2012). The effect of nitrogen enrichment on C1-cycling microorganisms and methane flux in salt marsh sediments. Front. Microbiol. 3, 1–10. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00090

Jaatinen, K., Knief, C., Dunfield, P. F., Yrjã Lã, K., and Fritze, H. (2004). Methanotrophic bacteria in boreal forest soil after fire. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 50, 195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.06.013

Jauhiainen, J., Takahashi, H., Heikkinen, J. E. P., Martikainen, P. J., and Vasander, H. (2005). Carbon fluxes from a tropical peat swamp forest floor. Glob. Change Biol. 11, 1788–1797. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.001031.x

Juottonen, H., Tuittila, E.-S., Juutinen, S., Fritze, H., and Yrjälä, K. (2008). Seasonality of rDNA- and rRNA-derived archaeal communities and methanogenic potential in a boreal mire. ISME J. 2, 1157–1168. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.66

Kai, F. M., Tyler, S. C., Randerson, J. T., and Blake, D. R. (2011). Reduced methane growth rate explained by decreased Northern Hemisphere microbial sources. Nature 476, 194–197. doi: 10.1038/nature10259

Karl, D. M., Beversdorf, L., Bjorkman, K. M., Church, M. J., Martinez, A., and DeLong, E. F. (2008). Aerobic production of methane in the sea. Nat. Geosci. 1, 473–478. doi: 10.1038/ngeo234

Keller, M., Mitre, M. E., and Stallard, R. F. (1990). Consumption of atmospheric methane in soils of central Panama: effects of agricultural development. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 4, 21–27. doi: 10.1029/GB004i001p00021

Keller, M., and Reiners, W. A. (1994). Soil atmosphere exchange of nitrous-oxide, nitric-oxide, and methane under secondary succession of pasture to forest in the Atlantic lowlands of Costa-Rica. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 8, 399–409. doi: 10.1029/94GB01660

Keppler, F., Hamilton, J. T. G., Brass, M., and Rockmann, T. (2006). Methane emissions from terrestrial plants under aerobic conditions. Nature 439, 187–191. doi: 10.1038/nature04420

King, G. M., and Nanba, K. (2008). Distribution of atmospheric methane oxidation and methanotrophic communities on Hawaiian volcanic deposits and soils. Microb. Environ. 23, 326–330. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME08529

Klemedtsson, A. K., and Klemedtsson, L. (1997). Methane uptake in Swedish forest soil in relation to liming and extra N-deposition. Biol. Fert. Soils 25, 296–301. doi: 10.1007/s003740050318

Koide, T., Saito, H., Shirota, T., Iwahana, G., Lopez, M. L., Maximov, T. C., et al. (2010). Effects of changes in the soil environment associated with heavy precipitation on soil greenhouse gas fluxes in a Siberian larch forest near Yakutsk. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 56, 645–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0765.2010.00484.x

Kolb, S. (2009). Aerobic methanol-oxidizing Bacteria in soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 300, 1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01681.x

Kolb, S., Carbrera, A., Kammann, C., Kampfer, P., Conrad, R., and Jackel, U. (2005). Quantitative impact of CO2 enriched atmosphere on abundances of methanotrophic bacteria in a meadow soil. Biol. Fert. Soils 41, 337–342. doi: 10.1007/s00374-005-0842-y

Konda, R., Ohta, S., Ishizuka, S., Heriyanto, J., and Wicaksono, A. (2010). Seasonal changes in the spatial structures of N2O, CO2, and CH4 fluxes from Acacia mangium plantation soils in Indonesia. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42, 1512–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.05.022

Kotsyurbenko, O. R., Chin, K.-J., Glagolev, M. V., Stubner, S., Simankova, M. V., Nozhevnikova, A. N., et al. (2004). Acetoclastic and hydrogenotrophic methane production and methanogenic populations in an acidic West-Siberian peat bog. Environ. Microbiol. 6, 1159–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00634.x

Kroeze, C., and Seitzinger, S. P. (1998). Nitrogen inputs to rivers, estuaries and continental shelves and related nitrous oxide emissions in 1990 and 2050: a global model. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 52, 195–212. doi: 10.1023/A:1009780608708

Kruse, C. W., and Iversen, N. (1995). Effect of plant succession, plowing, and fertilization on the microbial oxidation of atmospheric methane in a heathland soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 18, 121–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1995.tb00169.x

Lelieveld, J., Crutzen, P. J., and Dentener, F. J. (1998). Changing concentration, lifetime and climate forcing of atmospheric methane. Tellus B Chem. Phys. Meteorol. 50, 128–150. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0889.1998.t01-1-00002.x

Lelieveld, J., Dentener, F. J., Peters, W., and Krol, M. C. (2004). On the role of hydroxyl radicals in the self-cleansing capacity of the troposphere. 1-8. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 4, 2337–2344. doi: 10.5194/acp-4-2337-2004

Le Mer, J., and Roger, P. (2001). Production, oxidation, emission and consumption of methane by soils: A review. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 37, 25–50. doi: 10.1016/S1164-5563(01)01067-6

Levine, U. Y., Teal, T. K., Robertson, G. P., and Schmidt, T. M. (2011). Agriculture impact on microbial diversity and associated fluxes of carbon dioxide and methane. ISME J. 5, 1683–1691. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.40

Liebner, S., and Wagner, D. (2007). Abundance, distribution and potential activity of methane oxidizing bacteria in permafrost soils from the Lena Delta, Siberia. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 107–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01120.x

Macalady, J. L., McMillan, A. M. S., Dickens, A. F., Tyler, S. C., and Scow, K. M. (2002). Population dynamics of Type I and II methanotrophic bacteria in rice soils. Environ. Microbiol. 4, 148–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2002.00278.x

MacDonald, J. A., Eggleton, P., Bignell, D. E., Forzi, F., and Fowler, D. (1998). Methane emission by termites and oxidation by soils, across a forest disturbance gradient in the Mbalmayo Forest Reserve, Cameroon. Glob. Change Biol. 4, 409–418. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.1998.00163.x

MacDonald, J. A., Jeeva, D., Eggleton, P., Davies, R., Bignell, D. E., Fowler, D., et al. (1999). The effect of termite biomass and anthropogenic disturbance on the CH4 budgets of tropical forests in Cameroon and Borneo. Glob. Change Biol. 5, 869–879. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.1999.00279.x

Mariko, S., Urano, T., and Asanuma, J. (2007). Effects of irrigation on CO2 and CH4 fluxes from Mongolian steppe soil. J. Hydrol. 333, 118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2006.07.027

Martiny, A. C., Treseder, K., and Pusch, G. (2013). Phylogenetic conservatism of functional traits in microorganisms. ISME J. 7, 830–838. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.160

Maxfield, P. J., Hornibrook, E. R. C., and Evershed, R. P. (2006). Estimating high-affinity methanotrophic bacterial biomass, growth, and turnover in soil by phospholipid fatty acid C-13 labeling. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 3901–3907. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02779-05

Maxfield, P. J., Hornibrook, E. R. C., and Evershed, R. P. (2008). Acute impact of agriculture on high-affinity methanotrophic bacterial populations. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 1917–1924. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01587.x

McLain, J. E. T., and Ahmann, D. M. (2008). Increased moisture and methanogenesis contribute to reduced methane oxidation in elevated CO2 soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 44, 623–631. doi: 10.1007/s00374-007-0246-2

McLain, J. E. T., Kepler, T. B., and Ahmann, D. M. (2002). Belowground factors mediating changes in methane consumption in a forest soil under elevated CO2. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 16, 1050. doi: 10.1029/2001GB001439

McNamara, N. P., Black, H. I. J., Piearce, T. G., Reay, D. S., and Ineson, P. (2008). The influence of afforestation and tree species on soil methane fluxes from shallow organic soils at the UK Gisburn Forest Experiment. Soil Use Manage. 24, 1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-2743.2008.00147.x

Menyailo, O. V., Hungate, B. A., Abraham, W.-R., and Conrad, R. (2008). Changing land use reduces soil CH4 uptake by altering biomass and activity but not composition of high-affinity methanotrophs Glob. Change Biol. 14, 2405–2419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01648.x

Mohanty, S. R., Bodelier, P. L. E., Floris, V., and Conrad, R. (2006). Differential effects of nitrogenous fertilizers on methane-consuming microbes in rice field and forest soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1346–1354. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.2.1346-1354.2006

Mosier, A. R., Delgado, J. A., Cochran, V. L., Valentine, D. W., and Parton, W. J. (1997a). Impact of agriculture on soil consumption of atmospheric CH4 and a comparoson of CH4 and N2O flux in subacrtic, temperate and tropical grasslands. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 49, 71–83. doi: 10.1023/A:1009754207548

Mosier, A. R., Morgan, J. A., King, J. Y., LeCain, D., and Milchunas, D. G. (2002). Soil-atmosphere exchange of CH4, CO2, NOx, and N2O in the Colorado shortgrass steppe under elevated CO2. Plant Soil 240, 201–211. doi: 10.1023/A:1015783801324

Mosier, A. R., Parton, W. J., Valentine, D. W., Ojima, D. S., Schimel, D. S., and Heinemeyer, O. (1997b). CH4 and N2O fluxes in the Colorado shortgrass steppe.2. Long-term impact of land use change. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 11, 29–42. doi: 10.1029/96GB03612

Mosier, A. R., Schimel, D., Valentine, D., Bronson, K., and Parton, W. (1991). Methane and nitrous-oxide fluxes in native, fertilized and cultivated grassland. Nature 350, 330–332. doi: 10.1038/350330a0

Nazaries, L., Pan, Y., Bodrossy, L., Baggs, E. M., Millard, P., Murrell, J. C., et al. (2013). Evidence of Microbial Regulation of Biogeochemical Cycles from a Study on Methane Flux and Land Use Change. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 4013–4040. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00095-13

Nazaries, L., Tate, K. R., Ross, J. D., Singh, J., et al. (2011). Response of methanotrophic communities to afforestation and reforestation in New Zealand. ISME J. 5, 1832–1836. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.62

Neff, J. C., Bowman, W. D., Holland, E. A., Fisk, M. C., and Schmidt, S. K. (1994). Fluxes of nitrous-oxide and methane from nitrogen-amended soils in a Colorado alpine ecosystem. Biogeochemistry 27, 23–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00002569

Nisbet, R. E. R., Fisher, R., Nimmo, R. H., Bendall, D. S., Crill, P. M., Gallego-Sala, A. V., et al. (2009). Emission of methane from plants. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 276, 1347–1354. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1731

Oelbermann, M., and Schiff, S. L. (2010). Inundating contrasting boreal forest soils: CO2 and CH4 production rates. Ecoscience 17, 216–224. doi: 10.2980/17-2-3245

Phillips, R. L., Whalen, S. C., and Schlesinger, W. H. (2001). Influence of atmospheric CO2 enrichment on methane consumption in a temperate forest soil. Glob. Change Biol. 7, 557–563. doi: 10.1046/j.1354-1013.2001.00432.x

Poth, M., Anderson, I. C., Miranda, H. S., Miranda, A. C., and Riggan, P. J. (1995). The magnitude and persistence of soil NO, N2O, CH4, and CO, fluxes from burned tropical savanna in Brazil. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 9, 503–513. doi: 10.1029/95GB02086