95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Microbiol. , 29 June 2012

Sec. Virology

Volume 3 - 2012 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2012.00234

This article is part of the Research Topic Genomics and computational science for virus research View all 18 articles

Takushi Nomura1,2

Takushi Nomura1,2 Tetsuro Matano1,2*

Tetsuro Matano1,2*Virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are major effectors in acquired immune responses against viral infection. Virus-specific CTLs recognize specific viral peptides presented by major histocompatibility complex class-I (MHC-I) on the surface of virus-infected target cells via their T cell receptor (TCR) and eliminate target cells by both direct and indirect mechanisms. In human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infections, host immune responses fail to contain the virus and allow persistent viral replication, leading to AIDS progression. CTL responses exert strong suppressive pressure on HIV/SIV replication and cumulative studies have indicated association of HLA/MHC-I genotypes with rapid or slow AIDS progression.

Innate and acquired immune responses play an important role in the control of infectious pathogens. Pathogenic microbes are able to escape from the host innate immune responses and replicate in the hosts. After the acute growth phase, pathogen-specific neutralizing antibody and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses are induced and prevent the onset of pathogenic manifestations in most of acute infectious diseases. In HIV and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infections, these acquired immune responses are induced but fail to contain the virus and allow persistent viral replication, leading to AIDS progression, while persistent SIVsm infection of natural hosts, sooty mangabeys, does not result in disease onset (Silvestri et al., 2003). Effective neutralizing antibody responses are not efficiently induced in the acute phase (Burton et al., 2004). In contrast, virus-specific CTL responses play a main role in the reduction of viral loads from the peak to the set-point levels (Borrow et al., 1994; Koup et al., 1994; Matano et al., 1998; Jin et al., 1999; Schmitz et al., 1999). Previous studies suggest that, among various viral antigen-specific CTL responses, those directed against the viral structural protein Gag contribute to the control of viral replication (Edwards et al., 2002; Zuniga et al., 2006; Borghans et al., 2007; Kiepiela et al., 2007).

In virus-infected cells, antigenic peptides that are processed from viral proteins via the proteasome pathway and bound to MHC-I (HLA class I) molecules are presented on the cell surface. CTLs recognize antigenic peptide (epitope)-MHC-I complexes on the cell surface by their TCRs and eliminate the virus-infected cells by inducing apoptosis or lysis. Because presentation of antigenic peptides is restricted by MHC-I molecules, CTL efficacy is affected by MHC-I (HLA class I) genotypes.

HIV-infected individuals without anti-retroviral therapy (ART) mostly develop AIDS in 5–10 years after HIV exposure (Lui et al., 1988; Farewell et al., 1992). Humans have a single polymorphic HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C locus per chromosome. A number of studies on HIV-infected individuals reported the association of HLA genotypes with disease progression (Tang et al., 2002; Kiepiela et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2009; Leslie et al., 2010). Indeed, association of HLA-B⋆57 (Migueles et al., 2000; Altfeld et al., 2003; Miura et al., 2009) and HLA-B⋆27 (Goulder et al., 1997; Feeney et al., 2004; Altfeld et al., 2006; Schneidewind et al., 2007) with lower viral loads in the chronic phase and slow disease progression has been indicated. HLA-B⋆57-restricted Gag240-249 TW10 (TSTLQEQIGW) and HLA-B⋆27-restricted Gag263-272 KK10 (KRWIILGLNK) epitope-specific CTL responses exert strong suppressive pressure on HIV replication and often select for viral genome mutations resulting in viral escape from these CTL recognition with viral fitness costs (Goulder et al., 1997; Feeney et al., 2004). Some HIV-infected individuals possessing those HLA alleles associating with slower disease progression control viral replication for long periods, while the frequency of such elite controllers is under 1% (Lambotte et al., 2005; Grabar et al., 2009). In contrast, HLA genotypes such as HLA-B⋆35 associating with rapid disease progression have also been reported (Carrington et al., 1999; Gao et al., 2001). HLA-B⋆35 subtypes are divided into HLA-B⋆35-Px and HLA-B⋆35-Py based on the specificity of binding ability to epitope peptides in the P9 pocket. The former group, HLA-B⋆35-Px alleles including HLA-B⋆3502, B⋆3503, and B⋆3504 associate with rapid disease progression, whereas the latter HLA-B⋆35-Py alleles including HLA-B⋆3501 and HLA-B⋆3508 associate with relatively slower progression (Gao et al., 2001). Such differences in disease progression among HLA-B subtypes are also known in HLA-B⋆58 (Leslie et al., 2010).

Robust non-human primate AIDS models showing high pathogenic homology to human HIV infections are essential for AIDS research. While it is difficult to analyze the early phase in human HIV infection, animal models have considerable advantages in immunological analysis in the acute phase. Furthermore, comparisons among the hosts infected with the same virus strain are possible in animal AIDS models, although highly diversified HIVs are prevalent in humans. An important characteristic of HIV infection is selective loss of memory CCR5+ CD4+ T lymphocytes in the acute phase leading to persistent virus replication (Connor et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 1999; Brenchley et al., 2004). HIV tropism for CCR5+ CD4+ memory cells is considered as one central mechanism for persistent infection. R5-tropic SIVmac251/SIVmac239 or SIVsmE660/SIVsmE543-3 infection of rhesus macaques inducing the acute, selective loss of memory CD4+ T lymphocytes is currently considered the best AIDS model for analysis of AIDS pathogenesis and evaluation of vaccine efficacy (Veazey et al., 1998; Nishimura et al., 2004; Bontrop and Watkins, 2005; Mattapallil et al., 2005; Morgan et al., 2008). Recent studies indicated an association of restriction factor TRIM5α genotypes with disease progression in macaques infected with pathogenic SIVs such as SIVsmE660/SIVsmE543-3 but not in SIVmac239 infection (Kirmaier et al., 2010; Lim et al., 2010; de Groot et al., 2011; Fenizia et al., 2011; Letvin et al., 2011; Reynolds et al., 2011; Yeh et al., 2011). Macaque AIDS models of chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV) infection are also known. Infection with X4-tropic SHIVs such as SHIV89.6P results in acute CD4+ T cell depletion, while R5-tropic SHIVs such as SHIV162P3 induce persistent infection leading to chronic disease progression (Tsai et al., 2007; Nishimura et al., 2010; Zhuang et al., 2011). These SHIVs are useful especially for the analysis of Env-specific antibody responses (Ng et al., 2010; Watkins et al., 2011).

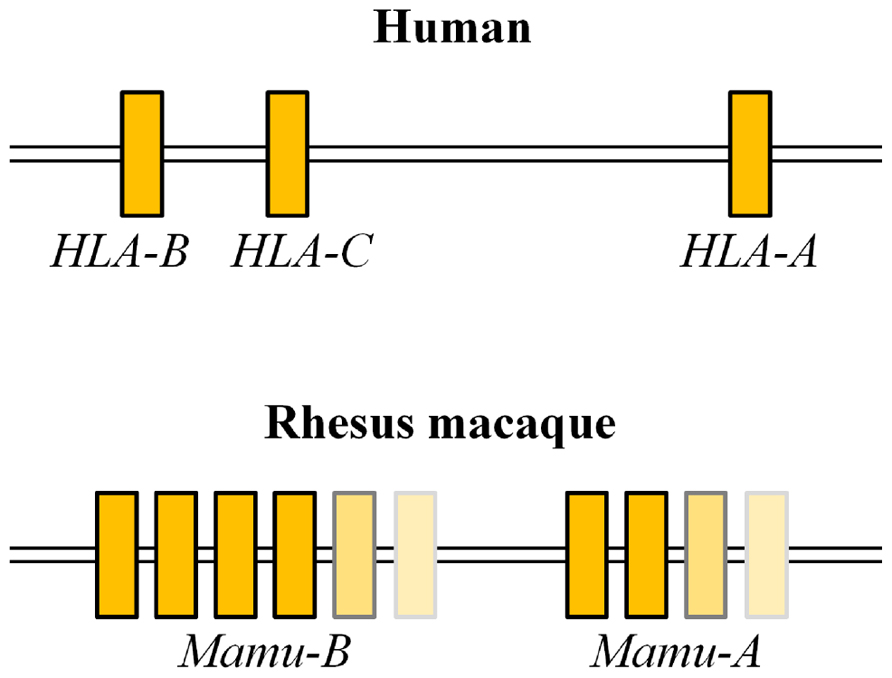

Human classical MHC-I alleles are composed of a single polymorphic HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C locus per chromosome. MHC-I haplotypes in rhesus macaques, however, have variable numbers of Mamu-A and Mamu-B loci (Boyson et al., 1996; Adams and Parham, 2001; Daza-Vamenta et al., 2004; Kulski et al., 2004; Otting et al., 2005; Figure 1). A number of studies described SIV infections in macaques sharing one or two MHC-I alleles, while few studies have examined SIV infection in macaques sharing an MHC-I haplotype.

FIGURE 1. Comparison of genome structures of MHC-I sub-regions in humans and rhesus macaques. Humans have a single polymorphic HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C locus per chromosome, while rhesus macaques have variable numbers of Mamu-A and Mamu-B loci per chromosome.

Simian immunodeficiency virus infections of Indian rhesus macaques are widely used as an AIDS model. Mamu-A⋆01, Mamu-B⋆08, and Mamu-B⋆17 are known as protective alleles and macaques possessing these alleles tend to show slow disease progression after SIVmac251/SIVmac239 challenge (Muhl et al., 2002; Mothe et al., 2003; Yant et al., 2006; Loffredo et al., 2007b). Fourteen Mamu-A⋆01-restricted SIVmac239 CTL epitopes have been reported (Allen et al., 2001; Mothe et al., 2002b). Mamu-A⋆01-restricted Tat28-35 SL8 (STPESANL)-specific and Gag181-189 CM9 (CTPYDINQM)-specific CTL responses are induced dominantly in SIVmac239 infection. Both epitope-specific CTLs show strong suppressive capacity against SIVmac239 replication in vitro (Loffredo et al., 2005), while the latter but not the former play a major role in suppression of viral replication in vivo (O’Connor et al., 2002; Loffredo et al., 2007c). In SHIV89.6P infection, Mamu-A⋆01-positive macaques elicit CM9-specific CTL responses and show slower disease progression than Mamu-A⋆01-negative animals (Zhang et al., 2002). Eight Mamu-B⋆08-restricted SIVmac239 CTL epitopes have been reported; previous studies indicated that Vif123-131 RL9 (RRAIRGEQL), Vif172-179 RL8 (RRDNRRGL), and Nef137-146 RL10 (RRHRILDIYL) epitope-specific CTL responses contribute to viral control (Loffredo et al., 2007a; Loffredo et al., 2008; Valentine et al., 2009; Mudd et al., 2012). SIVmac239 Vif66-73 HW8 (HLEVQGYW), Nef165-173 IW9 (IRYPKTFGW), and Nef195-203 MW9 (MHPAQTSQW) have been reported as Mamu-B⋆17-restricted CTL epitopes (Mothe et al., 2002a). In addition, cRW9 (RHLAFKCLW) in an alternate reading frame is known as a cryptic epitope (Maness et al., 2007). The cRW9-coding region [nucleotides 6889–6915 in SIVmac239 (accession number M33262)] is located in the same open reading frame that encodes exon 1 of the Rev protein but is downstream of the splice donor site. So, it is not predicted to be translated under normal biological circumstances. However, SIVmac239-infected Mamu-B⋆17-positive macaques efficiently induce cRW9-specific CTL responses.

We accumulated groups of Burmese rhesus macaques sharing individual MHC-I haplotypes (Tanaka-Takahashi et al., 2007; Naruse et al., 2010). SIVmac239 challenge of Burmese rhesus macaques mostly results in persistent viremia (geometric means of setpoint plasma viral loads: about 105 copies/ml) leading to AIDS (mean survival periods: about 2 years; Nomura et al., 2012). Further analysis revealed the association of MHC-I haplotypes with disease progression after SIVmac239 challenge.

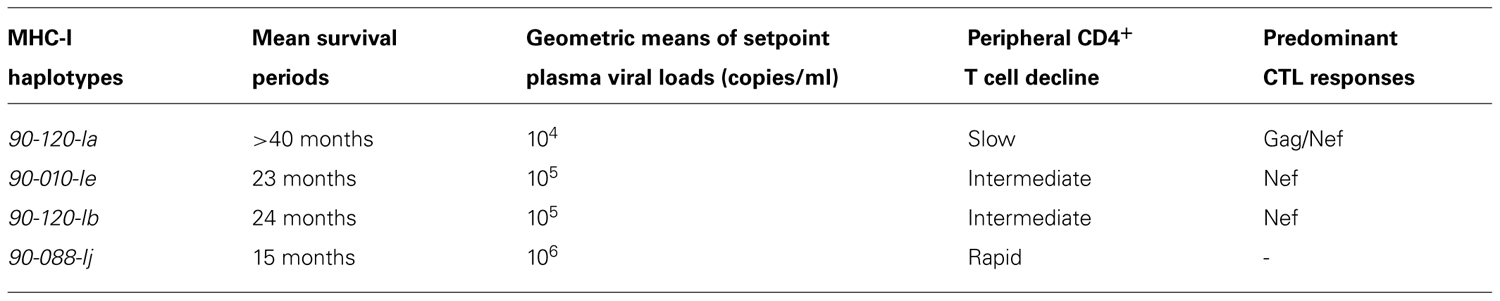

In our study (Nomura et al., 2012), the group of Burmese rhesus macaques possessing MHC-I haplotype 90-010-Ie (dominant MHC-I alleles: A1⋆066:01 and B⋆005:02) exhibited a typical pattern of disease progression after SIVmac239 challenge (Table 1). These animals showed predominant Nef-specific CTL responses, approximately 105 copies/ml of setpoint plasma viral loads (geometric means), and 2 years of mean survival periods. Another group of macaques possessing 90-120-Ib (dominant MHC-I alleles: A1⋆018:08 and B⋆036:03) showed similar setpoint viral loads and survival periods. However, the group of Burmese rhesus macaques possessing MHC-I haplotype 90-088-Ij (dominant MHC-I alleles: A1⋆008:01 and B⋆007:02) showed higher setpoint plasma viral loads (geometric means: about 106 copies/ml) and shorter survival periods (means: about 15 months; Table 1). These animals mostly showed poor CTL responses.

TABLE 1. Association of MHC-I haplotypes with disease progression in SIV infection (Nomura et al., 2012).

In contrast, the group of Burmese rhesus macaques possessing MHC-I haplotype 90-120-Ia (dominant MHC-I alleles: A1⋆043:01 and B⋆061:03), referred to as A+ animals, showed lower setpoint plasma viral loads (geometric means: about 104 copies/ml) and slower disease progression (means of survival periods: more than 40 months; Table 1). These animals predominantly elicited Gag-specific and Nef-specific CTL responses after SIVmac239 challenge. Mamu-A1⋆043:01-restricted Gag206-216 (IINEEAADWDL) and Mamu-A1⋆065:01-restricted Gag241-249 (SSVDEQIQW) were determined as dominant CTL epitopes. SIVmac239-infected A+ animals selected viral escape mutations from these epitope-specific CTL responses with viral fitness costs in the chronic phase (Kobayashi et al., 2005; Kawada et al., 2006). These mutations are GagL216S, a mutation leading to a leucine (L)-to-serine (S) substitution at the 216th amino acid in SIVmac239 Gag, and GagD244E, aspartic acid (D)-to-glutamic acid (E) at the 244th, or GagI247L, isoleucine [I]-to-L at the 247th. A+ animals immunized with a prophylactic prime-boost vaccine consisting of a DNA prime followed by a boost with a recombinant Sendai virus vector expressing SIVmac239 Gag controlled an SIVmac239 challenge (Matano et al., 2004). However, vaccinated A+ animals failed to control a challenge with a mutant SIVmac239 carrying GagL216S and GagD244E, indicating that Gag206-216-specific and Gag241-249-specific CTL responses are responsible for the control of the wild-type SIVmac239 replication (Kawada et al., 2006, 2008). Interestingly, the Mamu-A1⋆065:01-restricted SIVmac239 Gag241-249 epitope is located in a region corresponding to the HLA-B⋆57-restricted HIV Gag240-249 epitope TW10 and TW10-specific CTL responses have also been indicated to exert strong suppressive pressure on HIV replication. An SIVmac239 Gag241-249-specific CTL escape mutation, GagD244E, results in loss of viral fitness similarly with an HIV TW10-specific CTL escape mutation. Both of the Mamu-A1⋆065:01-restricted SIVmac239 Gag241-249 epitope and the HLA-B⋆57-restricted HIV TW10 epitope are considered to have the same anchor residues, S at position 2 and tryptophan (W) at the carboxyl terminus. Additionally, anchor residues of CTL epitopes presented by Mamu-B⋆17/Mamu-B⋆08 were indicated to be similar to those restricted by HLA-B⋆57/HLA-B⋆27 (Loffredo et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2011).

Human HLA genotypes largely affect disease progression in HIV infection, reflecting that CTL responses play a central role in suppression of HIV replication. Animal AIDS models are required for understanding of the interaction between highly diversified viruses and the hosts with polymorphic MHC-I genotypes. SIV infection of Indian rhesus macaques are widely used as an AIDS model, and association of certain MHC-I alleles with slower disease progression has been indicated. We have recently reported SIV infection of Burmese rhesus macaques as a robust AIDS model and indicated association of MHC-I haplotypes with disease progression. Accumulation of those macaque groups sharing MHC-I haplotypes could lead to constitution of a more sophisticated AIDS model facilitating analysis of virus-host immune interaction.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Adams, E. J., and Parham, P. (2001). Species-specific evolution of MHC class I genes in the higher primates. Immunol. Rev. 183, 41–64.

Allen, T. M., Mothe, B. R., Sidney, J., Jing, P., Dzuris, J. L., Liebl, M. E., Vogel, T. U., O’Connor, D. H., Wang, X., Wussow, M. C., Thomson, J. A., Altman, J. D., Watkins, D. I., and Sette, A. (2001). CD8(+) lymphocytes from simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques recognize 14 different epitopes bound by the major histocompatibility complex class I molecule mamu-A⋆01: implications for vaccine design and testing. J. Virol. 75, 738–749.

Altfeld, M., Addo, M. M., Rosenberg, E. S., Hecht, F. M., Lee, P. K., Vogel, M., Yu, X. G., Draenert, R., Johnston, M. N., Strick, D., Allen, T. M., Feeney, M. E., Kahn, J. O., Sekaly, R. P., Levy, J. A., Rockstroh, J. K., Goulder, P. J., and Walker, B. D. (2003). Influence of HLA-B57 on clinical presentation and viral control during acute HIV-1 infection. AIDS 17, 2581–2591.

Altfeld, M., Kalife, E. T., Qi, Y., Streeck, H., Lichterfeld, M., Johnston, M. N., Burgett, N., Swartz, M. E., Yang, A., Alter, G., Yu, X. G., Meier, A., Rockstroh, J. K., Allen, T. M., Jessen, H., Rosenberg, E. S., Carrington, M., and Walker, B. D. (2006). HLA alleles associated with delayed progression to AIDS contribute strongly to the initial CD8(+) T cell response against HIV-1. PLoS Med. 3, e403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030403

Bontrop, R. E., and Watkins, D. I. (2005). MHC polymorphism: AIDS susceptibility in non-human primates. Trends Immunol. 26, 227–233.

Borghans, J. A., Molgaard, A., de Boer, R. J., and Kesmir, C. (2007). HLA alleles associated with slow progression to AIDS truly prefer to present HIV-1 p24. PLoS ONE 2, e920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000920s

Borrow, P., Lewicki, H., Hahn, B. H., Shaw, G. M., and Oldstone, M. B. (1994). Virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity associated with control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 68, 6103–6110.

Boyson, J. E., Shufflebotham, C., Cadavid, L. F., Urvater, J. A., Knapp, L. A., Hughes, A. L., and Watkins, D. I. (1996). The MHC class I genes of the rhesus monkey. Different evolutionary histories of MHC class I and II genes in primates. J. Immunol. 156, 4656–4665.

Brenchley, J. M., Schacker, T. W., Ruff, L. E., Price, D. A., Taylor, J. H., Beilman, G. J., Nguyen, P. L., Khoruts, A., Larson, M., Haase, A. T., and Douek, D. C. (2004). CD4+ T cell depletion during all stages of HIV disease occurs predominantly in the gastrointestinal tract. J. Exp. Med. 200, 749–759.

Burton, D. R., Desrosiers, R. C., Doms, R. W., Koff, W. C., Kwong, P. D., Moore, J. P., Nabel, G. J., Sodroski, J., Wilson, I. A., and Wyatt, R. T. (2004). HIV vaccine design and the neutralizing antibody problem. Nat. Immunol. 5, 233–236.

Carrington, M., Nelson, G. W., Martin, M. P., Kissner, T., Vlahov, D., Goedert, J. J., Kaslow, R., Buchbinder, S., Hoots, K., and O’Brien, S. J. (1999). HLA and HIV-1: heterozygote advantage and B⋆35-Cw⋆04 disadvantage. Science 283, 1748–1752.

Connor, R. I., Sheridan, K. E., Ceradini, D., Choe, S., and Landau, N. R. (1997). Change in coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1-infected individuals. J. Exp. Med. 185, 621–628.

Daza-Vamenta, R., Glusman, G., Rowen, L., Guthrie, B., and Geraghty, D. E. (2004). Genetic divergence of the rhesus macaque major histocompatibility complex. Genome Res. 14, 1501–1515.

de Groot, N. G., Heijmans, C. M., Koopman, G., Verschoor, E. J., Bogers, W. M., and Bontrop, R. E. (2011). TRIM5 allelic polymorphism in macaque species/populations of different geographic origins: its impact on SIV vaccine studies. Tissue Antigens 78, 256–262.

Edwards, B. H., Bansal, A., Sabbaj, S., Bakari, J., Mulligan, M. J., and Goepfert, P. A. (2002). Magnitude of functional CD8+ T-cell responses to the gag protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 correlates inversely with viral load in plasma. J. Virol. 76, 2298–2305.

Farewell, V. T., Coates, R. A., Fanning, M. M., MacFadden, D. K., Read, S. E., Shepherd, F. A., and Struthers, C. A. (1992). The probability of progression to AIDS in a cohort of male sexual contacts of men with HIV disease. Int. J. Epidemiol. 21, 131–135.

Feeney, M. E., Tang, Y., Roosevelt, K. A., Leslie, A. J., McIntosh, K., Karthas, N., Walker, B. D., and Goulder, P. J. (2004). Immune escape precedes breakthrough human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viremia and broadening of the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response in an HLA-B27-positive long-term-nonprogressing child. J. Virol. 78, 8927–8930.

Fenizia, C., Keele, B. F., Nichols, D., Cornara, S., Binello, N., Vaccari, M., Pegu, P., Robert-Guroff, M., Ma, Z. M., Miller, C. J., Venzon, D., Hirsch, V., and Franchini, G. (2011). TRIM5alpha does not affect simian immunodeficiency virus SIV(mac251) replication in vaccinated or unvaccinated Indian rhesus macaques following intrarectal challenge exposure. J. Virol. 85, 12399–12409.

Gao, X., Nelson, G. W., Karacki, P., Martin, M. P., Phair, J., Kaslow, R., Goedert, J. J., Buchbinder, S., Hoots, K., Vlahov, D., O’Brien, S. J., and Carrington, M. (2001). Effect of a single amino acid change in MHC class I molecules on the rate of progression to AIDS. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1668–1675.

Goulder, P. J., Phillips, R. E., Colbert, R. A., McAdam, S., Ogg, G., Nowak, M. A., Giangrande, P., Luzzi, G., Morgan, B., Edwards, A., McMichael, A. J., and Rowland-Jones, S. (1997). Late escape from an immunodominant cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response associated with progression to AIDS. Nat. Med. 3, 212–217.

Grabar, S., Selinger-Leneman, H., Abgrall, S., Pialoux, G., Weiss, L., and Costagliola, D. (2009). Prevalence and comparative characteristics of long-term nonprogressors and HIV controller patients in the French Hospital Database on HIV. AIDS 23, 1163–1169.

Jin, X., Bauer, D. E., Tuttleton, S. E., Lewin, S., Gettie, A., Blanchard, J., Irwin, C. E., Safrit, J. T., Mittler, J., Weinberger, L., Kostrikis, L. G., Zhang, L., Perelson, A. S., and Ho, D. D. (1999). Dramatic rise in plasma viremia after CD8(+) T cell depletion in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J. Exp. Med. 189, 991–998.

Kawada, M., Igarashi, H., Takeda, A., Tsukamoto, T., Yamamoto, H., Dohki, S., Takiguchi, M., and Matano, T. (2006). Involvement of multiple epitope-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in vaccine-based control of simian immunodeficiency virus replication in rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 80, 1949–1958.

Kawada, M., Tsukamoto, T., Yamamoto, H., Iwamoto, N., Kurihara, K., Takeda, A., Moriya, C., Takeuchi, H., Akari, H., and Matano, T. (2008). Gag-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-based control of primary simian immunodeficiency virus replication in a vaccine trial. J. Virol. 82, 10199–10206.

Kiepiela, P., Leslie, A. J., Honeyborne, I., Ramduth, D., Thobakgale, C., Chetty, S., Rathnavalu, P., Moore, C., Pfafferott, K. J., Hilton, L., Zimbwa, P., Moore, S., Allen, T., Brander, C., Addo, M. M., Altfeld, M., James, I., Mallal, S., Bunce, M., Barber, L. D., Szinger, J., Day, C., Klenerman, P., Mullins, J., Korber, B., Coovadia, H. M., Walker, B. D., and Goulder, P. J. (2004). Dominant influence of HLA-B in mediating the potential co-evolution of HIV and HLA. Nature 432, 769–775.

Kiepiela, P., Ngumbela, K., Thobakgale, C., Ramduth, D., Honeyborne, I., Moodley, E., Reddy, S., de Pierres, C., Mncube, Z., Mkhwanazi, N., Bishop, K., van der Stok, M., Nair, K., Khan, N., Crawford, H., Payne, R., Leslie, A., Prado, J., Prendergast, A., Frater, J., McCarthy, N., Brander, C., Learn, G. H., Nickle, D., Rousseau, C., Coovadia, H., Mullins, J. I., Heckerman, D., Walker, B. D., and Goulder, P. (2007). CD8+ T-cell responses to different HIV proteins have discordant associations with viral load. Nat. Med. 13, 46–53.

Kirmaier, A., Wu, F., Newman, R. M., Hall, L. R., Morgan, J. S., O’Connor, S., Marx, P. A., Meythaler, M., Goldstein, S., Buckler-White, A., Kaur, A., Hirsch, V. M., and Johnson, W. E. (2010). TRIM5 suppresses cross-species transmission of a primate immunodeficiency virus and selects for emergence of resistant variants in the new species. PLoS Biol. 8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000462

Kobayashi, M., Igarashi, H., Takeda, A., Kato, M., and Matano, T. (2005). Reversion in vivo after inoculation of a molecular proviral DNA clone of simian immunodeficiency virus with a cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte escape mutation. J. Virol. 79, 11529–11532.

Koup, R. A., Safrit, J. T., Cao, Y., Andrews, C. A., McLeod, G., Borkowsky, W., Farthing, C., and Ho, D. D. (1994). Temporal association of cellular immune responses with the initial control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 syndrome. J. Virol. 68, 4650–4655.

Kulski, J. K., Anzai, T., Shiina, T., and Inoko, H. (2004). Rhesus macaque class I duplicon structures, organization, and evolution within the alpha block of the major histocompatibility complex. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 2079–2091.

Lambotte, O., Boufassa, F., Madec, Y., Nguyen, A., Goujard, C., Meyer, L., Rouzioux, C., Venet, A., and Delfraissy, J. F. (2005). HIV controllers: a homogeneous group of HIV-1-infected patients with spontaneous control of viral replication. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41, 1053–1056.

Leslie, A., Matthews, P. C., Listgarten, J., Carlson, J. M., Kadie, C., Ndung’u, T., Brander, C., Coovadia, H., Walker, B. D., Heckerman, D., and Goulder, P. J. (2010). Additive contribution of HLA class I alleles in the immune control of HIV-1 infection. J. Virol. 84, 9879–9888.

Letvin, N. L., Rao, S. S., Montefiori, D. C., Seaman, M. S., Sun, Y., Lim, S. Y., Yeh, W. W., Asmal, M., Gelman, R. S., Shen, L., Whitney, J. B., Seoighe, C., Lacerda, M., Keating, S., Norris, P. J., Hudgens, M. G., Gilbert, P. B., Buzby, A. P., Mach, L. V., Zhang, J., Balachandran, H., Shaw, G. M., Schmidt, S. D., Todd, J. P., Dodson, A., Mascola, J. R., and Nabel, G. J. (2011). Immune and genetic correlates of vaccine protection against mucosal infection by SIV in monkeys. Sci. Transl. Med. 3, 81ra36.

Lim, S. Y., Rogers, T., Chan, T., Whitney, J. B., Kim, J., Sodroski, J., and Letvin, N. L. (2010). TRIM5alpha modulates immunodeficiency virus control in rhesus monkeys. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000738. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000738

Loffredo, J. T., Rakasz, E. G., Giraldo, J. P., Spencer, S. P., Grafton, K. K., Martin, S. R., Napoe, G., Yant, L. J., Wilson, N. A., and Watkins, D. I. (2005). Tat(28-35)SL8-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes are more effective than Gag(181–189)CM9-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes at suppressing simian immunodeficiency virus replication in a functional in vitro assay. J. Virol. 79, 14986–14991.

Loffredo, J. T., Bean, A. T., Beal, D. R., Leon, E. J., May, G. E., Piaskowski, S. M., Furlott, J. R., Reed, J., Musani, S. K., Rakasz, E. G., Friedrich, T. C., Wilson, N. A., Allison, D. B., and Watkins, D. I. (2008). Patterns of CD8+ immunodominance may influence the ability of Mamu-B⋆08-positive macaques to naturally control simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 replication. J. Virol. 82, 1723–1738.

Loffredo, J. T., Friedrich, T. C., Leon, E. J., Stephany, J. J., Rodrigues, D. S., Spencer, S. P., Bean, A. T., Beal, D. R., Burwitz, B. J., Rudersdorf, R. A., Wallace, L. T., Piaskowski, S. M., May, G. E., Sidney, J., Gostick, E., Wilson, N. A., Price, D. A., Kallas, E. G., Piontkivska, H., Hughes, A. L., Sette, A., and Watkins, D. I. (2007a). CD8+ T cells from SIV elite controller macaques recognize Mamu-B⋆08-bound epitopes and select for widespread viral variation. PLoS ONE 2, e1152. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001152

Loffredo, J. T., Maxwell, J., Qi, Y., Glidden, C. E., Borchardt, G. J., Soma, T., Bean, A. T., Beal, D. R., Wilson, N. A., Rehrauer, W. M., Lifson, J. D., Carrington, M., and Watkins, D. I. (2007b). Mamu-B⋆08-positive macaques control simian immunodeficiency virus replication. J. Virol. 81, 8827–8832.

Loffredo, J. T., Burwitz, B. J., Rakasz, E. G., Spencer, S. P., Stephany, J. J., Vela, J. P., Martin, S. R., Reed, J., Piaskowski, S. M., Furlott, J., Weisgrau, K. L., Rodrigues, D. S., Soma, T., Napoe, G., Friedrich, T. C., Wilson, N. A., Kallas, E. G., and Watkins, D. I. (2007c). The antiviral efficacy of simian immunodeficiency virus-specific CD8+ T cells is unrelated to epitope specificity and is abrogated by viral escape. J. Virol. 81, 2624–2634.

Loffredo, J. T., Sidney, J., Bean, A. T., Beal, D. R., Bardet, W., Wahl, A., Hawkins, O. E., Piaskowski, S., Wilson, N. A., Hildebrand, W. H., Watkins, D. I., and Sette, A. (2009). Two MHC class I molecules associated with elite control of immunodeficiency virus replication, Mamu-B⋆08 and HLA-B⋆2705, bind peptides with sequence similarity. J. Immunol. 182, 7763–7775.

Lui, K. J., Darrow, W. W., and Rutherford, G. W., 3rd (1988). A model-based estimate of the mean incubation period for AIDS in homosexual men. Science 240, 1333–1335.

Maness, N. J., Valentine, L. E., May, G. E., Reed, J., Piaskowski, S. M., Soma, T., Furlott, J., Rakasz, E. G., Friedrich, T. C., Price, D. A., Gostick, E., Hughes, A. L., Sidney, J., Sette, A., Wilson, N. A., and Watkins, D. I. (2007). AIDS virus specific CD8+ T lymphocytes against an immunodominant cryptic epitope select for viral escape. J. Exp. Med. 204, 2505–2512.

Matano, T., Kobayashi, M., Igarashi, H., Takeda, A., Nakamura, H., Kano, M., Sugimoto, C., Mori, K., Iida, A., Hirata, T., Hasegawa, M., Yuasa, T., Miyazawa, M., Takahashi, Y., Yasunami, M., Kimura, A., O’Connor, D. H., Watkins, D. I., and Nagai, Y. (2004). Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-based control of simian immunodeficiency virus replication in a preclinical AIDS vaccine trial. J. Exp. Med. 199, 1709–1718.

Matano, T., Shibata, R., Siemon, C., Connors, M., Lane, H. C., and Martin, M. A. (1998). Administration of an anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody interferes with the clearance of chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus during primary infections of rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 72, 164–169.

Mattapallil, J. J., Douek, D. C., Hill, B., Nishimura, Y., Martin, M., and Roederer, M. (2005). Massive infection and loss of memory CD4+ T cells in multiple tissues during acute SIV infection. Nature 434, 1093–1097.

Migueles, S. A., Sabbaghian, M. S., Shupert, W. L., Bettinotti, M. P., Marincola, F. M., Martino, L., Hallahan, C. W., Selig, S. M., Schwartz, D., Sullivan, J., and Connors, M. (2000). HLA B⋆5701 is highly associated with restriction of virus replication in a subgroup of HIV-infected long term nonprogressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 2709–2714.

Miura, T., Brockman, M. A., Schneidewind, A., Lobritz, M., Pereyra, F., Rathod, A., Block, B. L., Brumme, Z. L., Brumme, C. J., Baker, B., Rothchild, A. C., Li, B., Trocha, A., Cutrell, E., Frahm, N., Brander, C., Toth, I., Arts, E. J., Allen, T. M., and Walker, B. D. (2009). HLA-B57/B⋆5801 human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite controllers select for rare gag variants associated with reduced viral replication capacity and strong cytotoxic T-lymphocyte [corrected] recognition. J. Virol. 83, 2743–2755.

Morgan, C., Marthas, M., Miller, C., Duerr, A., Cheng-Mayer, C., Desrosiers, R., Flores, J., Haigwood, N., Hu, S. L., Johnson, R. P., Lifson, J., Montefiori, D., Moore, J., Robert-Guroff, M., Robinson, H., Self, S., and Corey, L. (2008). The use of nonhuman primate models in HIV vaccine development. PLoS Med. 5, e173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050173

Mothe, B. R., Sidney, J., Dzuris, J. L., Liebl, M. E., Fuenger, S., Watkins, D. I., and Sette, A. (2002a). Characterization of the peptide-binding specificity of Mamu-B⋆17 and identification of Mamu-B⋆17-restricted epitopes derived from simian immunodeficiency virus proteins. J. Immunol. 169, 210–219.

Mothe, B. R., Horton, H., Carter, D. K., Allen, T. M., Liebl, M. E., Skinner, P., Vogel, T. U., Fuenger, S., Vielhuber, K., Rehrauer, W., Wilson, N., Franchini, G., Altman, J. D., Haase, A., Picker, L. J., Allison, D. B., and Watkins, D. I. (2002b). Dominance of CD8 responses specific for epitopes bound by a single major histocompatibility complex class I molecule during the acute phase of viral infection. J. Virol. 76, 875–884.

Mothe, B. R., Weinfurter, J., Wang, C., Rehrauer, W., Wilson, N., Allen, T. M., Allison, D. B., and Watkins, D. I. (2003). Expression of the major histocompatibility complex class I molecule Mamu-A⋆01 is associated with control of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 replication. J. Virol. 77, 2736–2740.

Mudd, P. A., Ericsen, A. J., Burwitz, B. J., Wilson, N. A., O’Connor, D. H., Hughes, A. L., and Watkins, D. I. (2012). Escape from CD8+ T cell responses in Mamu-B⋆00801+ macaques differentiates progressors from elite controllers. J. Immunol. 188, 3364–3370.

Muhl, T., Krawczak, M., Ten Haaft, P., Hunsmann, G., and Sauermann, U. (2002). MHC class I alleles influence set-point viral load and survival time in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus monkeys. J. Immunol. 169, 3438–3446.

Naruse, T. K., Chen, Z., Yanagida, R., Yamashita, T., Saito, Y., Mori, K., Akari, H., Yasutomi, Y., Miyazawa, M., Matano, T., and Kimura, A. (2010). Diversity of MHC class I genes in Burmese-origin rhesus macaques. Immunogenetics 62, 601–611.

Ng, C. T., Jaworski, J. P., Jayaraman, P., Sutton, W. F., Delio, P., Kuller, L., Anderson, D., Landucci, G., Richardson, B. A., Burton, D. R., Forthal, D. N., and Haigwood, N. L. (2010). Passive neutralizing antibody controls SHIV viremia and enhances B cell responses in infant macaques. Nat. Med. 16, 1117–1119.

Nishimura, Y., Igarashi, T., Donau, O. K., Buckler-White, A., Buckler, C., Lafont, B. A., Goeken, R. M., Goldstein, S., Hirsch, V. M., and Martin, M. A. (2004). Highly pathogenic SHIVs and SIVs target different CD4+ T cell subsets in rhesus monkeys, explaining their divergent clinical courses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12324–12329.

Nishimura, Y., Shingai, M., Willey, R., Sadjadpour, R., Lee, W. R., Brown, C. R., Brenchley, J. M., Buckler-White, A., Petros, R., Eckhaus, M., Hoffman, V., Igarashi, T., and Martin, M. A. (2010). Generation of the pathogenic R5-tropic simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIVAD8 by serial passaging in rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 84, 4769–4781.

Nomura, T., Yamamoto, H., Shiino, T., Takahashi, N., Nakane, T., Iwamoto, N., Ishii, H., Tsukamoto, T., Kawada, M., Matsuoka, S., Takeda, A., Terahara, K., Tsunetsugu-Yokota, Y., Iwata-Yoshikawa, N., Hasegawa, H., Sata, T., Naruse, T. K., Kimura, A., and Matano, T. (2012). Association of major histocompatibility complex class I haplotypes with disease progression after simian immunodeficiency virus challenge in Burmese rhesus macaques. J. Virol. 86, 6481–6490.

O’Connor, D. H., Allen, T. M., Vogel, T. U., Jing, P., DeSouza, I. P., Dodds, E., Dunphy, E. J., Melsaether, C., Mothe, B., Yamamoto, H., Horton, H., Wilson, N., Hughes, A. L., and Watkins, D. I. (2002). Acute phase cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape is a hallmark of simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Nat. Med. 8, 493–499.

Otting, N., Heijmans, C. M., Noort, R. C., de Groot, N. G., Doxiadis, G. G., van Rood, J. J., Watkins, D. I., and Bontrop, R. E. (2005). Unparalleled complexity of the MHC class I region in rhesus macaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 1626–1631.

Reynolds, M. R., Sacha, J. B., Weiler, A. M., Borchardt, G. J., Glidden, C. E., Sheppard, N. C., Norante, F. A., Castrovinci, P. A., Harris, J. J., Robertson, H. T., Friedrich, T. C., McDermott, A. B., Wilson, N. A., Allison, D. B., Koff, W. C., Johnson, W. E., and Watkins, D. I. (2011). The TRIM5{alpha} genotype of rhesus macaques affects acquisition of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVsmE660 infection after repeated limiting-dose intrarectal challenge. J. Virol. 85, 9637–9640.

Schmitz, J. E., Kuroda, M. J., Santra, S., Sasseville, V. G., Simon, M. A., Lifton, M. A., Racz, P., Tenner-Racz, K., Dalesandro, M., Scallon, B. J., Ghrayeb, J., Forman, M. A., Montefiori, D. C., Rieber, E. P., Letvin, N. L., and Reimann, K. A. (1999). Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science 283, 857–860.

Schneidewind, A., Brockman, M. A., Yang, R., Adam, R. I., Li, B., Le Gall, S., Rinaldo, C. R., Craggs, S. L., Allgaier, R. L., Power, K. A., Kuntzen, T., Tung, C. S., LaBute, M. X., Mueller, S. M., Harrer, T., McMichael, A. J., Goulder, P. J., Aiken, C., Brander, C., Kelleher, A. D., and Allen, T. M. (2007). Escape from the dominant HLA-B27-restricted cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response in Gag is associated with a dramatic reduction in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J. Virol. 81, 12382–12393.

Silvestri, G., Sodora, D. L., Koup, R. A., Paiardini, M., O’Neil, S. P., McClure, H. M., Staprans, S. I., and Feinberg, M. B. (2003). Nonpathogenic SIV infection of sooty mangabeys is characterized by limited bystander immunopathology despite chronic high-level viremia. Immunity 18, 441–452.

Tanaka-Takahashi, Y., Yasunami, M., Naruse, T., Hinohara, K., Matano, T., Mori, K., Miyazawa, M., Honda, M., Yasutomi, Y., Nagai, Y., and Kimura, A. (2007). Reference strand-mediated conformation analysis-based typing of multiple alleles in the rhesus macaque MHC class I Mamu-A and Mamu-B loci. Electrophoresis 28, 918–924.

Tang, J., Tang, S., Lobashevsky, E., Myracle, A. D., Fideli, U., Aldrovandi, G., Allen, S., Musonda, R., and Kaslow, R. A. (2002). Favorable and unfavorable HLA class I alleles and haplotypes in Zambians predominantly infected with clade C human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 76, 8276–8284.

Tsai, L., Trunova, N., Gettie, A., Mohri, H., Bohm, R., Saifuddin, M., and Cheng-Mayer, C. (2007). Efficient repeated low-dose intravaginal infection with X4 and R5 SHIVs in rhesus macaque: implications for HIV-1 transmission in humans. Virology 362, 207–216.

Valentine, L. E., Loffredo, J. T., Bean, A. T., Leon, E. J., MacNair, C. E., Beal, D. R., Piaskowski, S. M., Klimentidis, Y. C., Lank, S. M., Wiseman, R. W., Weinfurter, J. T., May, G. E., Rakasz, E. G., Wilson, N. A., Friedrich, T. C., O’Connor, D. H., Allison, D. B., and Watkins, D. I. (2009). Infection with “escaped” virus variants impairs control of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 replication in Mamu-B⋆08-positive macaques. J. Virol. 83, 11514–11527.

Veazey, R. S., DeMaria, M., Chalifoux, L. V., Shvetz, D. E., Pauley, D. R., Knight, H. L., Rosenzweig, M., Johnson, R. P., Desrosiers, R. C., and Lackner, A. A. (1998). Gastrointestinal tract as a major site of CD4+ T cell depletion and viral replication in SIV infection. Science 280, 427–431.

Wang, Y. E., Li, B., Carlson, J. M., Streeck, H., Gladden, A. D., Goodman, R., Schneidewind, A., Power, K. A., Toth, I., Frahm, N., Alter, G., Brander, C., Carrington, M., Walker, B. D., Altfeld, M., Heckerman, D., and Allen, T. M. (2009). Protective HLA class I alleles that restrict acute-phase CD8+ T-cell responses are associated with viral escape mutations located in highly conserved regions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 83, 1845–1855.

Watkins, J. D., Diaz-Rodriguez, J., Siddappa, N. B., Corti, D., and Ruprecht, R. M. (2011). Efficiency of neutralizing antibodies targeting the CD4-binding site: influence of conformational masking by the V2 loop in R5-tropic clade C simian-human immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 85, 12811–12814.

Wu, Y., Gao, F., Liu, J., Qi, J., Gostick, E., Price, D. A., and Gao, G. F. (2011). Structural basis of diverse peptide accommodation by the rhesus macaque MHC class I molecule Mamu-B⋆17: insights into immune protection from simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Immunol. 187, 6382–6392.

Yant, L. J., Friedrich, T. C., Johnson, R. C., May, G. E., Maness, N. J., Enz, A. M., Lifson, J. D., O’Connor, D. H., Carrington, M., and Watkins, D. I. (2006). The high-frequency major histocompatibility complex class I allele Mamu-B⋆17 is associated with control of simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 replication. J. Virol. 80, 5074–5077.

Yeh, W. W., Rao, S. S., Lim, S. Y., Zhang, J., Hraber, P. T., Brassard, L. M., Luedemann, C., Todd, J. P., Dodson, A., Shen, L., Buzby, A. P., Whitney, J. B., Korber, B. T., Nabel, G. J., Mascola, J. R., and Letvin, N. L. (2011). The TRIM5 gene modulates penile mucosal acquisition of simian immunodeficiency virus in rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 85, 10389–10398.

Zhang, Z., Schuler, T., Zupancic, M., Wietgrefe, S., Staskus, K. A., Reimann, K. A., Reinhart, T. A., Rogan, M., Cavert, W., Miller, C. J., Veazey, R. S., Notermans, D., Little, S., Danner, S. A., Richman, D. D., Havlir, D., Wong, J., Jordan, H. L., Schacker, T. W., Racz, P., Tenner-Racz, K., Letvin, N. L., Wolinsky, S., and Haase, A. T. (1999). Sexual transmission and propagation of SIV and HIV in resting and activated CD4+ T cells. Science 286, 1353–1357.

Zhang, Z. Q., Fu, T. M., Casimiro, D. R., Davies, M. E., Liang, X., Schleif, W. A., Handt, L., Tussey, L., Chen, M., Tang, A., Wilson, K. A., Trigona, W. L., Freed, D. C., Tan, C. Y., Horton, M., Emini, E. A., and Shiver, J. W. (2002). Mamu-A⋆01 allele-mediated attenuation of disease progression in simian-human immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol. 76, 12845–12854.

Zhuang, K., Finzi, A., Tasca, S., Shakirzyanova, M., Knight, H., Westmoreland, S., Sodroski, J., and Cheng-Mayer, C. (2011). Adoption of an “open” envelope conformation facilitating CD4 binding and structural remodeling precedes coreceptor switch in R5 SHIV-infected macaques. PLoS ONE 6, e21350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021350

Zuniga, R., Lucchetti, A., Galvan, P., Sanchez, S., Sanchez, C., Hernandez, A., Sanchez, H., Frahm, N., Linde, C. H., Hewitt, H. S., Hildebrand, W., Altfeld, M., Allen, T. M., Walker, B. D., Korber, B. T., Leitner, T., Sanchez, J., and Brander, C. (2006). Relative dominance of Gag p24-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes is associated with human immunodeficiency virus control. J. Virol. 80, 3122–3125.

Keywords: CTL, HIV, HLA, Mamu, MHC-I, MHC-I haplotype, SIV

Citation: Nomura T and Matano T (2012) Association of MHC-I genotypes with disease progression in HIV/SIV infections. Front. Microbio. 3:234. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2012.00234

Received: 01 May 2012; Paper pending published: 16 May 2012;

Accepted: 11 June 2012; Published online: 29 June 2012.

Edited by:

Hironori Sato, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, JapanCopyright: © 2012 Nomura and Matano. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited.

*Correspondence: Tetsuro Matano, AIDS Research Center, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, 1-23-1 Toyama, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo 162-8640, Japan. e-mail:dG1hdGFub0BuaWguZ28uanA=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.