94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol., 05 April 2012

Sec. Terrestrial Microbiology

Volume 3 - 2012 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2012.00101

This article is part of the Research TopicNitrogen cycling in terrestrial ecosystemsView all 12 articles

The Chilean sclerophyllous matorral is a Mediterranean semiarid ecosystem affected by erosion, with low soil fertility, and limited by nitrogen. However, limitation of resources is even more severe for desert soils such as from the Atacama Desert, one of the most extreme arid deserts on Earth. Topsoil organic matter, nitrogen and moisture content were significantly higher in the semiarid soil compared to the desert soil. Although the most significant loss of biologically preferred nitrogen from terrestrial ecosystems occurs via denitrification, virtually nothing is known on the activity and composition of denitrifier communities thriving in arid soils. In this study we explored denitrifier communities from two soils with profoundly distinct edaphic factors. While denitrification activity in the desert soil was below detection limit, the semiarid soil sustained denitrification activity. To elucidate the genetic potential of the soils to sustain denitrification processes we performed community analysis of denitrifiers based on nitrite reductase (nirK and nirS) genes as functional marker genes for this physiological group. Presence of nirK-type denitrifiers in both soils was demonstrated but failure to amplify nirS from the desert soil suggests very low abundance of nirS-type denitrifiers shedding light on the lack of denitrification activity. Phylogenetic analysis showed a very low diversity of nirK with only three distinct genotypes in the desert soil which conditions presumably exert a high selection pressure. While nirK diversity was also limited to only few, albeit distinct genotypes, the semiarid matorral soil showed a surprisingly broad genetic variability of the nirS gene. The Chilean matorral is a shrub land plant community which form vegetational patches stabilizing the soil and increasing its nitrogen and carbon content. These islands of fertility may sustain the development and activity of the overall microbial community and of denitrifiers in particular.

Five Mediterranean-type environments exist across the six continents of the world. One of them, the sclerophyllous matorral, located between the Andean premountains and the coastal range of Central Chile extends between 30° and 38°S. This semiarid ecosystem is characterized by a Mediterranean climate with dry summers and rainy winters (Gajardo, 1994) and by a shrubland plant community of hardleaved plant species and small trees surrounded by grasses (Fuentes et al., 1984). Its Andean part is particular in that it is covered with vegetational patches of Colletia hystrix (Clos) a native actinorhizal plant forming a symbiosis with the nitrogen-fixing actinomycete Frankia (Carú, 1993; Carú et al., 2003). This symbiosis is an important source of nitrogen input into the soil resulting in higher amounts of nitrogen in soil associated to the plants than in the bulk soil (Orlando et al., 2007). In addition to nitrogen, microbial communities in the vicinity of plants are selectively favored by elevated carbon content and hence differed in their bacterial composition from that of the bulk soil (Orlando et al., 2007; Farías et al., 2009) or soil associated with other non-actinorhizal plants (Farías et al., 2009).

The matorral in Central Chile is flanked in the south by temperate forest and in the north by the Atacama Desert (30° to 20° S). While the northern part of the Atacama Desert is a hyperarid Mars-like environment, the southern area of the desert is considered an arid environment because it receives just some annual precipitation in the range of <20 mm mainly as water condensation from fogs and heavy dew (Gómez-Silva et al., 2008). This input of water may sustain sufficient microbial activity to close the nitrogen cycle and hence to counterbalance the atmospheric deposition which could be responsible for the accumulation of unaltered nitrate in the hyperarid parts of the Atacama Desert (Ewing et al., 2007). In addition, in the arid zone of southern Atacama Desert sporadically irregular and short rainfall pulses occur resulting in temporary increased soil moisture that cause the “desert bloom” event. These short periods may reflect “hot moments” of microbial activity and resulted in shifts in nitrate levels (Orlando et al., 2010). Elevated nitrate levels during the bloom could for instance reflect enhanced nitrification activity which would be in line with compositional changes in the ammonia oxidizer community (Orlando et al., 2010).

In arid soils microbial activity is primarily dependent on the presence of water (Gómez-Silva et al., 2008). However, nitrogen is often the most limiting nutrient in almost all of these systems (Whitford, 1992) and at moderate to cold temperatures nitrogen flux is driven by the production and loss of reactive nitrogen species by microbial activity in the soil (McCalley and Sparks, 2009). The most significant loss of nitrate from terrestrial ecosystems in general and from desert ecosystems in particular occurs via denitrification which is the dominant anaerobic respiratory process based on nitrogen (Bowden, 1986; Megonigal et al., 2004). During denitrification oxidized nitrogen compounds ( and ) are used as alternative electron acceptors for energy production. Nitrogen oxides are reduced stepwise to gaseous end products (NO, N2O, and N2) which are concomitantly released. Thus, besides limiting ecosystem productivity the process is also responsible for the production of potent greenhouse gases causing well-known climatic effects (Conrad, 1996). Two structurally different but functionally equivalent enzymes catalyze nitrite reduction: a copper- and a cytochrome cd1-containing nitrite reductase encoded by the genes nirK and nirS, respectively. Both genes were useful targets in PCR-based molecular approaches to detect denitrifier communities from a variety of soil environments such as meadow (Bremer et al., 2009; Falk et al., 2010), glacier foreland (Kandeler et al., 2006; Töwe et al., 2010), forest (Priemé et al., 2002; Katsuyama et al., 2008), and arable soil (Throbäck et al., 2004; Wolsing and Priemé, 2004). However, practically nothing is known about the composition of this functional group of arid or semiarid soils. While bacterial numbers and activity in general but also those associated with nitrogen cycling are low in desert ecosystems due to the lack of water (Gómez-Silva et al., 2008), in semiarid degraded areas nitrogen cycling processes may play a key role to assist sustainable restoration practices (Bastida et al., 2009). The sclerophyllous matorral has been shown previously to harbor a rather unique bacterial community making it an unique habitat compared to other Mediterranean-type semiarid ecosystems (Farías et al., 2009). However, whether this also applies for the functional group of denitrifiers is impossible to conclude from an approach to target the soil bacterial community in general. The present report focuses on a comparative evaluation of the diversity of nirK and nirS gene fragments in a semiarid and an arid soil from two types of arid ecosystems, the sclerophyllous matorral and the Atacama Desert, and how the genetic potential for denitrification is interlinked with potential activity. Although this report focuses on data obtained for only one sampling, we assume that denitrifier communities and activity were stable over time spans in the range of decades and hence representative for the prevalent conditions in these arid areas. These data therefore constitute a valuable contribution toward an enhanced understanding of microbial communities and N-turnover in arid soil systems.

Soil samples were taken at a depth of 0–10 cm from the sclerophyllous matorral of “El Romeral” (33°48′S, 70°14′W), Cajón del Maipo, RM and from the subdesert matorral of “Sierra Pajaritos” (27°59′S, 70°34′W), Desierto de Atacama, III Región, Chile during fall (April) 2006 (Figure 1). Random sampling points were selected that were separated from each other between 1 and 2 m within a plot of 15 m × 15 m at each site. The semiarid matorral samples represented bulk soil samples avoiding islands of fertility and were taken before the beginning of the rainy season. Samples from the Atacama Desert represent arid soil taken during the dry season, without any trace of the “desert bloom” event. To minimize the effects of small scale heterogeneity 10 cores collected at each sampling site were pooled and homogenized by sieving to 2-mm aggregate size and stored at 4°C.

Figure 1. Sampling region at “El Romeral,” Cajón del Maipo (semiarid matorral soil), and “Sierra Pajaritos” Atacama Desert (arid subdesert soil) in Chile.

Edaphic factors were determined as follows: pH was measured using potentiometry; moisture content and organic matter were calculated gravimetrically before and after desiccation and calcination, respectively; nitrate concentration was measured with an ion chromatograph (IC; Forster, 1995).

N2O production by denitrification was determined by the denitrification enzyme activity (DEA) assay (Smith and Tiedje, 1979). Therefore, soil equivalent to 5 g dry weight to which 5 ml sterile filtered solution of glucose (1 mM), potassium nitrate (1 mM), and chloramphenicol (1 g l−1) were added was incubated anaerobically at 25°C. Acetylene was also added at a final partial pressure of 10 kPa to inhibit N2O reduction. N2O was measured with a gas chromatograph (Carlo Erba Instruments, GC 8000) connected to a 63Ni-electron capture detector at 30 min intervals during 90 min after the addition of acetylene. Data were evaluated with the software Peak simple (version 2.66, SRI Instruments).

Soil DNA was extracted from 0.25 g of each soil composite sample using the FastDNA Soil Spin kit (Qbiogene, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was quantified and analyzed photometrically at 260 and 280 nm with a ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop® Technologies Inc., Rockland, ME, USA). Concentrations of DNA extracted from matorral and desert soil were >50 and 10–15 ng μl−1, respectively and DNA extracts were pure (A260/280 > 1.8). Subsequently, nirK and nirS gene fragments were PCR amplified from 1 μl of DNA (matorral soil) or 1 μl of fivefold concentrated DNA (desert soil) using primers nirK1F–nirK5R (Braker et al., 1998) and cd3aF–R3cd (Throbäck et al., 2004), respectively. PCR reactions were done as described previously (Braker et al., 1998; Throbäck et al., 2004) but 1.25 U RedAccuTaq™ LA DNA Polymerase (Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany) was used. For nirK amplification the concentration of each primer was reduced to 10 pmol μl−1and annealing temperatures during the first 10 touchdown cycles started with 56°C and were kept at 54°C during the following 30 cycles. For nirS amplification the reactions were run with annealing temperatures of 57 and 55°C for 40 cycles. Amplicons of 514 bp and 425 bp for nirK and nirS, respectively, were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1.5% [w/v (weight in volume)] agarose gels (Biozym Diagnostik, Hess. Oldendorf, Germany) followed by a 15 min staining with ethidium bromide (0.5 mg l−1). Bands were visualized by UV excitation.

The nirK and nirS amplicons from semiarid soil were purified using the Wizard® DNA Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) whilst the nirK amplicons obtained from the Desert soil DNA had to be gel purified using the Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega) to eliminate non-specific PCR-products. Clone libraries of nirK and nirS gene fragments were constructed using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After blue–white selection clones were screened for inserts of the proper length (nirK, 514 bp; nirS, 425 bp) using T7/M13 vector primers and inserts from positive clones were sequenced using an ABI PRISM 3100 Avant-Genetic-Analyzer Prism sequencer. Phylogenetic analyses were performed using ARB (www.arb-home.de) and the PHYLIP program package (Felsenstein, 1989). Initially, trees were calculated based on >2000 nirK and nirS database entries and clusters were defined whenever sequences were consistently grouped together by the neighbor joining, parsimony, and maximum likelihood method. Subsequently, sequences from the majority of uncultured organisms and from isolates of redundant phylogenetic affiliation were removed manually to reduce crowding of the trees without changing their overall topologies. Hence, bootstrap values cannot be shown.

Deduced NirK and NirS amino acid sequences were assigned to operational taxonomic units (OTUs) based on an arbitrarily set threshold level of 10% distance using Distance-Based OTU and Richness (DOTUR) which were then used to calculate rarefaction curves (Schloss and Handelsman, 2005). The coverage CX of the clone libraries was calculated using CX = 1 − (Nx/n) (Nx, the number of unique sequences in the sample; n, the total number of sequences). The nirK and nirS gene sequences from the matorral soil have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers EU645543–EU645573 and EU650277–EU650316, respectively and nirK sequences from the desert soil under accession numbers JQ219219–JQ219261.

The soils differed profoundly with respect to their edaphic parameters and in potential denitrification activity (Table 1). The semiarid sclerophyllous matorral soil receives an average annual precipitation of 350 mm but the sampling location in the Atacama Desert is characterized by an arid desert climate, with scarce, and extremely low annual precipitation (<20 mm; McKay et al., 2003). Nitrate, organic matter, and moisture content were significantly higher in the matorral soil relative to the desert soil but pH was higher in the desert soil. While potential denitrification activity was below the detection limit in the arid soil, activity albeit only at a low level of 1.8 ng N-N2O gsdw−1 h−1 was detected for the matorral soil.

To assess denitrifier community composition in soils of the Chilean sclerophyllous matorral and the Atacama Desert, a cultivation-independent approach was applied using PCR amplification, subsequent cloning, and phylogenetic analysis of deduced amino acid sequences of nitrite reductase genes (nirK/nirS). The clone libraries of the matorral soil consisted of 31 and 40 clones for nirK and nirS, respectively, and all of them contained a nirK- or nirS-type insert. For the desert soil the nirK amplification was less specific resulting in only 43 positives out of 70 clones. No amplification was obtained for this soil using nirS specific primers even if the DNA was concentrated by precipitation presumably due to very low target numbers in the extract. Threshold values of 90% amino acid sequence identity were used to define OTU which were used to calculate rarefaction curves as well as the coverage of the clone libraries. Based on this definition a Chao I richness of 6.5 (95%-confidence interval of 5.1–20.1) NirK–OTUs was estimated for the denitrifier community in the matorral soil while community richness was lower with only 3.0 (3.0–3.0) NirK-OTUs (data not shown) estimated for the desert soil and this contrast was significant owing to the non-overlapping confidence intervals. A surprisingly high richness was estimated for nirS-type denitrifiers in the semiarid soil with 17.0 (14.5–31.9) different OTUs (data not shown).

The coverage of the libraries was 96.8% for nirK and 87.5% for nirS in the matorral thus indicating that the extent to which the sequences in the libraries represent the total populations was rather high. No singletons were found for NirK sequences from the desert soil reflected by 100% coverage of the clone library.

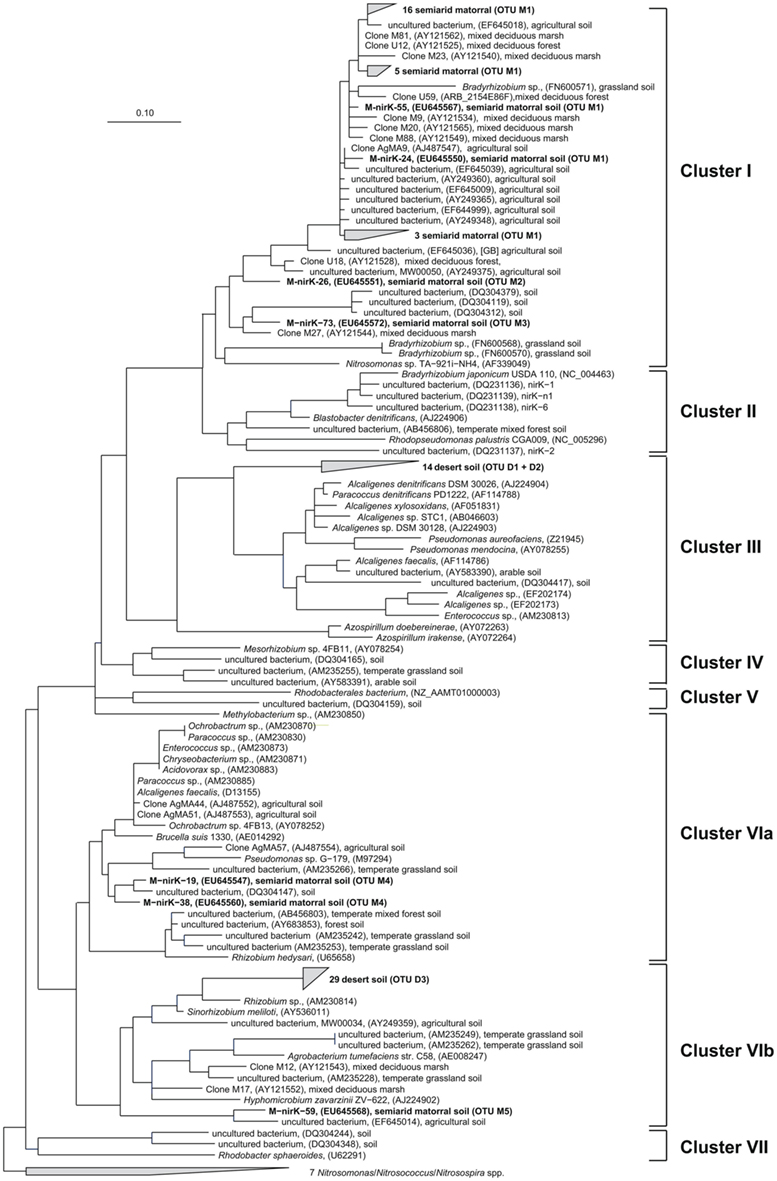

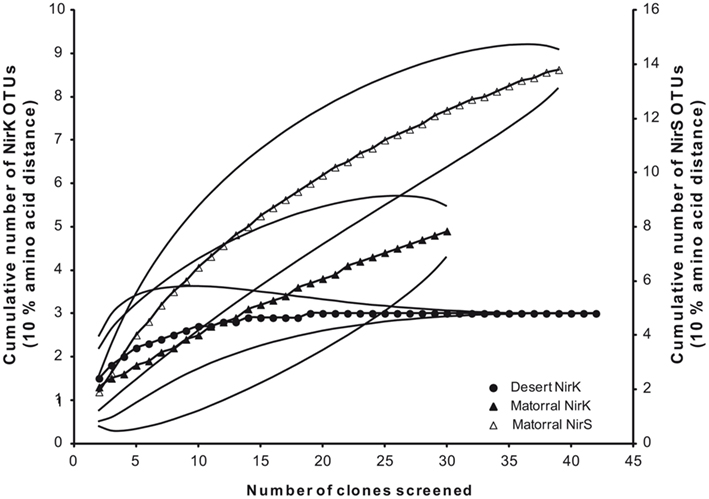

Deduced NirK amino acid sequences from the matorral soil grouped into only two distinct clusters (I and VI; Figure 2) and five OTUs. Rarefaction analysis, however, indicated that owing to the high fraction of singletons the nirK diversity was not sufficiently sampled and thus probably higher than estimated (Figure 3). The majority of NirK sequences (90.4%) were clustered with NirK from Bradyrhizobium spp. and Nitrosomonas sp. TA-921i-NH4 in three OTUs (M1, M2, and M3) in cluster I. These sequences were most similar (average 94 [87–100]% identity) to environmental clones previously obtained from rhizosphere (Henry et al., 2008), mixed deciduous marsh (Priemé et al., 2002), agricultural land (Avrahami et al., 2002; Wolsing and Priemé, 2004), and sewage sludge-amended soil (Throbäck et al., 2007). Three additional sequences (OTUs M4 and M5) grouped in two different subclusters (Cluster VIa/b) and showed amino acid similarity to cultivated denitrifiers. One of them was related to NirK from organisms belonging to the order Rhizobiales (on average 83% identity). Two others were most closely affiliated with NirK from an uncultured rhizosphere soil bacterium and clustered with NirK sequences from a variety of organisms [e.g., Alcaligenes sp., Acidovorax sp., Paracoccus sp., Enterococcus sp., Chryseobacterium sp., Brucella suis, Pseudomonas sp., and Rhizobium hedysari (88% identical)]. Many of these organisms were isolated in a cultivation-dependent study of denitrifiers from activated sludge of a municipal wastewater treatment plant (Heylen et al., 2006). NirK-type denitrifiers were even less diverse in the desert soil belonging to only three different OTUs (D1, D2, and D3) within clusters III and VIb (Figure 2) and the diversity seemed sufficiently covered by the clone library as shown by rarefaction analysis (Figure 3). These clusters are both dominated by NirK sequences from cultured denitrifiers but comprised only few environmental sequences such as those from the desert soil which clustered separately from the cultured representatives. The only overlap between NirK types from both soils occurred in cluster VIb which also included one sequence derived from the semiarid soil besides the desert soil subbranch.

Figure 2. Neighbor joining tree (Kimura amino acid replacement model) based on 134 deduced amino acid positions of nirK-gene sequences retrieved from soil samples of the sclerophyllous matorral and the Atacama Desert (in bold) and other terrestrial habitats as well as from isolates (accession numbers are given in parentheses).

Figure 3. Rarefaction analysis of deduced amino acids of nitrite reductase genes from the sclerophyllous matorral (▲, Δ) and the Atacama Desert (•) based on a threshold level of 10% amino acid distance; NirK (closed symbols) and NirS (open symbols).

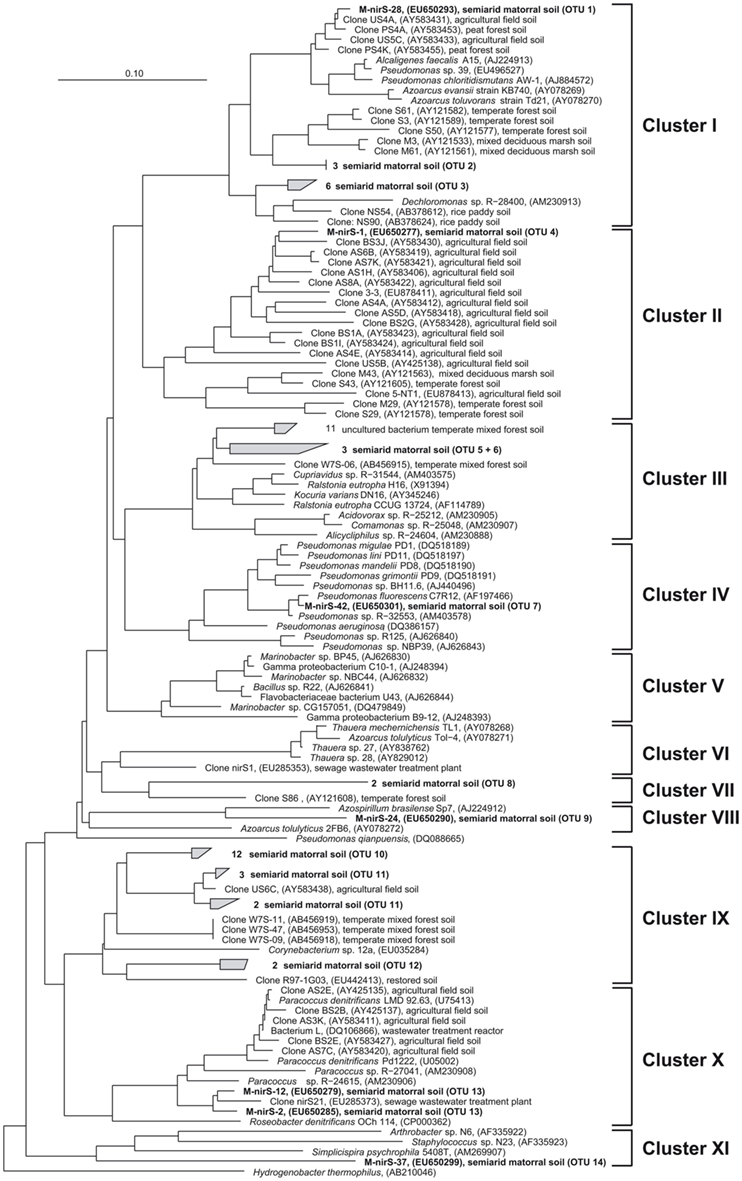

Surprisingly, NirS in the semiarid soil showed a much greater genetic diversity than NirK. NirS-type nitrite reductase sequences grouped into 14 OTUs in 9 distinct clusters within the nirS gene tree (Figure 4). Most NirS sequences in this report (47.5%) were clustered with NirS from Corynebacterium sp. 12a (Cluster IX) and were most similar (average 85% identity) to environmental sequences obtained from a temperate mixed forest soil (Katsuyama et al., 2008), an agricultural field soil (Throbäck et al., 2004) and a short-term soil restoration chronosequence (Smith and Ogram, 2008). In addition, a significant number of clones (25%) were grouped in part with environmental clones related to the genera Pseudomonas, Alcaligenes, and Azoarcus; and some formed a group with Dechloromonas sp. R-28400 (cluster I). Additional clones fell into clusters composed of divergent lineages and shared the greatest similarity with sequences obtained from agricultural field soil (Throbäck et al., 2004) and temperate forest soil (Priemé et al., 2002; Katsuyama et al., 2008) within clusters II, III, and VII. The remaining NirS sequences were most closely affiliated with those of Pseudomonas fluorescens C7R12 (cluster IV), Azospirillum brasilense Sp7 (cluster VIII), Paracoccus sp. (Cluster X), and Simplicispira psychrophila 5408T (cluster XI). However, it should be noted that the majority of NirS sequences obtained from this semiarid soil grouped together forming distinct subclusters of arid soil clones within the major clusters of the gene trees, which were divergent from previously described sequences in the database including sequences from world soils and thus revealing an unknown diversity of nirS-type denitrifiers in the matorral ecosystem.

Figure 4. Neighbor joining tree (Kimura amino acid replacement model) based on 131 deduced amino acid positions of nirS gene sequences retrieved from soil samples of the sclerophyllous matorral (in bold) and other terrestrial habitats as well as from isolates (accession numbers are given in parentheses).

It was estimated that globally up to 30% of the loss of nitrogen gas from terrestrial ecosystems originate from arid soil ecosystems, at least in part due to the vast area (31.6% of total uncultivated land) they occupy (Bowden, 1986). Although this loss was primarily attributed to denitrification, virtually nothing is known on microbial communities in arid soils with the potential to denitrify. This study addresses whether denitrifier communities thrive in arid soils and whether they may contribute to nitrogen losses from these ecosystems. Therefore, we explored denitrifier communities from two soils, an arid soil from the Atacama Desert and a semiarid sclerophyllous matorral soil in Central Chile, and their propensity to contribute to ecosystem nitrogen losses via denitrification. Soils of the hyperarid part of the Atacama Desert located between approximately 22° and 26° S are rich in nitrate (up to 150 μg g−1 soil; Connon et al., 2007) which is introduced into the soil via lightning. It accumulates in the soil system owing to lack of denitrification activity caused by severe water limitation (Mancinelli et al., 2006; Ewing et al., 2007; Gómez-Silva et al., 2008). In the wetter southern extends of the Atacama Desert soil nitrate content is much lower, for instance 17.71 ± 0.17 μg gsdw−1 at our sampling station (Table 1). These lower levels are believed to result mainly from nitrogen losses via denitrification which counterbalances nitrate accumulation by closing the nitrogen cycle (Ewing et al., 2007). More active nutrient cycling may indeed be expected due to higher microbial abundance with cultivable bacteria in the range of 106 CFU g1 of soil in desert soils of the southern Atacama Desert compared to <100 CFU g1 of soil in the hyperarid zone (Navarro-González et al., 2003; Connon et al., 2007).

In this study we demonstrated the presence of nirK-type denitrifiers in an arid desert soil from the southern Atacama using a cultivation-independent approach. Diversity of nirK was restricted to only few genotypes in clusters with NirK sequences of cultured denitrifiers and other environmental clones but our sequences formed habitat-specific branches separate from these sequences (Figure 2). Although we did not measure gene copy numbers, our study suggests that the abundance of nitrite reductase containing denitrifiers in this soil was presumably very low. Amplification of nirK-gene fragments was successful only if DNA extracts were concentrated by ethanol precipitation while amplification of nirS-type denitrifiers failed despite our various attempts to optimize PCR conditions.

Moreover, denitrification activity determined by the DEA assay was below the detection limit suggesting that the number of enzymes which pre-existed in the soil at the sampling time was not sufficient to sustain measurable activity even at the surplus of nitrate provided for the DEA assay. Our sampling took place during a dry period without any signs of plant growth, so the data of this study reflect only the status of denitrifier communities during dry periods which may be different from that following a rainfall event. Activity and biomass of desert soil microbial communities in general are permanently and predominantly limited by water availability, but also by carbon (Ewing et al., 2008) and nitrogen (Xie et al., 2001) or by low C:N ratios (Gallardo and Schlesinger, 1992). Occasionally, however, they can become active in response to one of the rare rainfall events that occur, for instance during the El Niño phenomenon every 7–8 years. Indeed, indication of soil nitrate reduction activity which could at least in part be due to denitrification in the southern Atacama Desert came from a previous study of Orlando et al. (2010) who observed nitrate disappearance following a desert bloom during which it had accumulated in the soil. Further support comes from another study, which confirmed the potential to denitrify of the desert soil microbial community upon incubation of the soil at 60% water holding capacity for 84 days albeit with potentials in the low range of all activities measured to date (Orlando, unpublished results). Interestingly, even after this incubation or after combined amendment with water and nitrate nirS gene remained undetectable by the PCR assays used. Taken together, our data suggest that at least nirK-type denitrifier communities are present in this desert soil, which are predominantly dormant and thus stable over decades but may become active given conditions become favorable for denitrification. Then, during short time spans they may contribute to a large part of the N-loss from this system.

The sclerophyllous matorral differs from this arid soil ecosystem by several edaphic factors including higher precipitation and soil moisture, carbon and nitrogen content but lower pH (Table 1). Hence we hypothesized more abundant and more active microbial communities. Potential denitrification activity was detectable for the semiarid matorral soil albeit only at a very low level. Although annual precipitation at our sampling site at Cajón del Maipo, Chile (350 mm; Table 1) was higher compared to, for instance, that of the Mojave desert (137 mm; www.usgs.gov), the potential denitrifying enzyme activity of the soil (1.81 ± 0.41 ng N-N2O gsdw−1 h−1) was below the range measured for the Mojave and other desert soils (9–237 ng N g−1 h−1) during the dry season (Peterjohn, 1991).

However, in agreement with detectable potential activity, nitrite reductase gene (nirK and nirS) fragments could be readily amplified from this soil which is indicative for the presence of denitrifiers. Denitrifiers of the nirK-type were of very limited diversity (Figures 2 and 3) and their nirK genes were in their majority closely related to nirK from Bradyrhizobium spp. recently cultivated from an experimental agricultural soil (Hashimoto et al., 2009) and from a grassland soil (Falk et al., 2010). However, rhizobial and bradyrhizobial symbionts were also isolated from a mesquite woodland soil of the Sonoran desert and were in their majority capable of nitrate respiration and denitrification in particular (Jenkins, 2003) suggesting that related organisms may play a major role in denitrification in arid soil systems. In contrast to nirK, nirS-type denitrifiers were surprisingly diverse (Figures 3 and 4), which could be in accordance with the higher numbers of nirS than nirK detected in another semiarid soil (Bastida et al., 2009). It may, however, also agree with the higher level of diversity of NirS compared to NirK in an acid soil with pH 5.4 (Braker et al., 2012), which to our knowledge was never described for neutral soils. Whether this reflects environmental preferences of nirK- and nirS-containing denitrifiers is currently unknown, probably because only few of the organisms which dominate in nature have been cultivated. Although analysis of molecular data suggests that the assembly of nirK- and nirS-type denitrifier communities in nature is governed by environmental gradients this is not well studied (Jones and Hallin, 2010). It is well-known for instance, that pH is a strong driver for bacterial community development in soils (Fierer and Jackson, 2006) but this was never addressed systematically with respect to differences between nirK- and nirS-type denitrifiers.

A previous report using terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) to characterize the diversity of the bacterial community of the matorral soil showed a dominance of Firmicutes and in addition that a significant number of the T-RFs could not be identified using suitable databases (Farías et al., 2009). When this study was refined using a cloning and sequencing approach it turned out that this semiarid soil was dominated by Proteobacteria but that Firmicutes, Acido- and Actinobacteria were the next most abundant groups (unpublished data). Hence, the sclerophyllous matorral could be an ecosystem different to other arid and semiarid soils with respect to the bacterial community suggesting that this habitat could be colonized by unique bacteria especially adapted to this semiarid soil. Nevertheless, more information on the functional and genetic diversity of the microbial assemblages related to nitrogen cycling is necessary to understand the functioning of these arid soil ecosystems.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work was supported by FONDECYT project No 1080280 and by the Max Planck Society. J. Orlando acknowledges a scholarship from Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst (DAAD).

Avrahami, S., Conrad, R., and Braker, G. (2002). Effect of soil ammonium concentration on N2O release and on the community structure of ammonia oxidizers and denitrifiers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 5685–5692.

Bastida, F., Perez-Mora, A., Babic, K., Hai, B., Hernandez, T., Garcia, C., and Schloter, M. (2009). Role of amendments on N cycling in Mediterranean abandoned semiarid soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 41, 195–205.

Bowden, W. B. (1986). Gaseous nitrogen emissions from undisturbed terrestrial ecosystems: an assessment of their impacts on local and global nitrogen budgets. Biogeochemistry 2, 249–279.

Braker, G., Dörsch, P., and Bakken, L. R. (2012). Genetic characterization of denitrifier communities with contrasting intrinsic functional traits. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 79, 542–554.

Braker, G., Fesefeldt, A., and Witzel, K. P. (1998). Development of PCR primer systems for amplification of nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS) to detect denitrifying bacteria in environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 3769–3775.

Bremer, C., Braker, G., Matthies, D., Beierkuhnlein, C., and Conrad, R. (2009). Plant presence and species combination, but not diversity, influence denitrifier activity and the composition of nirK-type denitrifier communities in grassland soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 70, 377–387.

Carú, M. (1993). Characterization of native Frankia strains isolated from Chilean shrubs (Rhamnaceae). Plant Soil 157, 137–145.

Carú, M., Mosquera, G., Bravo, L., Guevara, R., Sepúlveda, D., and Cabello, A. (2003). Infectivity and effectivity of Frankia strains from the Rhamnaceae family on different actinorhizal plants. Plant Soil 251, 219–225.

Connon, S. A., Lester, E. D., Shafaat, H. S., Obenhuber, D. C., and Ponce, A. (2007). Bacterial diversity in hyperarid Atacama Desert soils. J. Geophys. Res. 112, G04S17.

Conrad, R. (1996). Soil microorganisms as controllers of atmospheric trace gases (H2, CO, CH4, OCS, N2O, and NO). Microbiol. Rev. 60, 609–640.

Ewing, S. A., Macalady, J. L., Warren-Rhodes, K., McKay, C. P., and Amundson, R. (2008). Changes in the soil C cycle at the arid-hyperarid transition in the Atacama Desert. J. Geophys. Res. 113, G02S90.

Ewing, S. A., Michalski, G., Thiemens, M., Quinn, R. C., Macalady, J. L., Kohl, S., Wankel, S. D., Kendall, C., McKay, C. P., and Amundson, R. (2007). Rainfall limit of the N cycle on earth. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 21, GB3009.

Falk, S., Liu, B., and Braker, G. (2010). Isolation, genetic and functional characterization of novel soil nirK-type denitrifiers. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 33, 337–347.

Farías, F., Orlando, J., Bravo, L., Guevara, R., and Car, M. (2009). Comparison of soil bacterial communities associated with actinorhizal, non-actinorhizal plants and the interspaces in the sclerophyllous matorral from Central Chile in two different seasons. J. Arid Environ. 73, 1117–1124.

Fierer, N., and Jackson, R. B. (2006). The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 626–631.

Forster, J. C. (1995). “Soil sampling, handling, storage and analysis,” in Methods in Applied Soil Microbiology and Biochemistry, eds K. Alef and P. Nannipieri (London: Academic Press), 49–121.

Fuentes, E. R., Otaiza, R. D., Alliende, M. C., Hoffmann, A., and Poiani, A. (1984). Shrub clumps of the Chilean matorral vegetation: structure and possible maintenance mechanisms. Oecologia 62, 405–411.

Gajardo, R. (1994). La vegetación natural de Chile. Clasificación y distribuión geográphica. Santiago de Chile, Chile.

Gallardo, A., and Schlesinger, W. H. (1992). Carbon and nitrogen limitations of soil microbial biomass in desert ecosystems. Biogeochemistry 18, 1–17.

Gómez-Silva, B., Rainey, F. A., Warren-Rhodes, K. A., McKay, C. P., and Navarro-González, R. (2008). “Atacama desert soil microbiology,” in Microbiology of Extreme Soils, eds P. Dion and C. S. Nautiyal (Heidelberg: Springer), 117–132.

Hashimoto, T., Koga, M., and Masaoka, Y. (2009). Advantages of a diluted nutrient broth medium for isolating N2-producing denitrifying bacteria of α-proteobacteria in surface and subsurface upland soils. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 55, 647–659.

Henry, S., Texier, S., Hallet, S., Bru, D., Dambreville, C., Cheneby, D., Bizouard, F., Germon, J. C., and Philippot, L. (2008). Disentangling the rhizosphere effect on nitrate reducers and denitrifiers: insight into the role of root exudates. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 3082–3092.

Heylen, K., Gevers, D., Vanparys, B., Wittebolle, L., Geets, J., Boon, N., and De Vos, P. (2006). The incidence of nirS and nirK and their genetic heterogeneity in cultivated denitrifiers. Environ. Microbiol. 8, 2012–2021.

Jenkins, M. B. (2003). Rhizobial and bradyrhizobial symbionts of mesquite from the Sonoran desert: salt tolerance, facultative halophily and nitrate respiration. Soil Biol. Biochem. 35, 1675–1682.

Jones, C. M., and Hallin, S. (2010). Ecological and evolutionary factors underlying global and local assembly of denitrifier communities. ISME J. 1–9.

Kandeler, E., Deiglmayr, K., Tscherko, D., Bru, D., and Philippot, L. (2006). Abundance of narG, nirS, nirK, and nosZ genes of denitrifying bacteria during primary successions of a glacier foreland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5957–5962.

Katsuyama, C., Kondo, N., Suwa, Y., Yamagishi, T., Itoh, M., Ohte, N., Kimura, H., Nagaosa, K., and Kato, K. (2008). Denitrification activity and relevant bacteria revealed by nitrite reductase gene fragments in soil of temperate mixed forest. Microbes Environ. 23, 337–345.

Mancinelli, R. L., Warren-Rhodes, K., and Banin, A. (2006). Washington, DC: Astrobiology Science Conference.

McCalley, C. K., and Sparks, J. P. (2009). Abiotic gas formation drives nitrogen loss from a desert ecosystem. Science 326, 837–840.

McKay, C. P., Friedmann, E. I., Gómez-Silva, B., Cáceres-Villanueva, L., Andersen, D. T., and Landheim, R. (2003). Temperature and moisture conditions for life in the extreme arid region of the Atacama desert: four years of observations including the El Niño of 1997–1998. Astrobiology 3, 393–406.

Megonigal, J. P., Hines, M. E., and Visscher, P. T. (2004). Anaerobic Metabolism: Linkages to Trace Gases and Aerobic Processes. Oxford: Elsevier-Pergamon.

Navarro-González, R., Rainey, F. A., Molina, P., Bagaley, D. R., Hollen, B. J., de la Rosa, J., Small, A. M., Quinn, R. C., Grunthaner, F. J., Cáceres, L., Gomez-Silva, B., and McKay, C. P. (2003). Mars-like soils in the Atacama desert, Chile, and the dry limit of microbial life. Science 302, 1018–1021.

Orlando, J., Alfaro, M., Bravo, L., Guevara, R., and Carú, M. (2010). Bacterial diversity and occurrence of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in the Atacama desert soil during a ‘desert bloom’ event. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42, 1183–1188.

Orlando, J., Chavez, M., Bravo, L., Guevara, R., and Caru, M. (2007). Effect of Colletia hystrix (Clos), a pioneer actinorhizal plant from the Chilean matorral, on the genetic and potential metabolic diversity of the soil bacterial community. Soil Biol. Biochem. 39, 2769–2776.

Peterjohn, W. T. (1991). Denitrification: enzyme content and activity in desert soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 23, 845–855.

Priemé, A., Braker, G., and Tiedje, J. M. (2002). Diversity of nitrite reductase (nirK and nirS) gene fragments in forested upland and wetland soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 1893–1900.

Schloss, P. D., and Handelsman, J. (2005). Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 1501–1506.

Smith, J. M., and Ogram, A. (2008). Genetic and functional variation in denitrifier populations along a short-term restoration chronosequence. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5615–5620.

Smith, M. S., and Tiedje, J. M. (1979). Phases of denitrification following oxygen depletion in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 11, 261–267.

Throbäck, I. N., Enwall, K., Jarvis, Å., and Hallin, S. (2004). Reassessing PCR primers targeting nirS, nirK and nosZ genes for community surveys of denitrifying bacteria with DGGE. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 49, 401–417.

Throbäck, I. N., Johansson, M., Rosenquist, M., Pell, M., Hansson, M., and Hallin, S. (2007). Silver (Ag+) reduces denitrification and induces enrichment of novel nirK genotypes in soil. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 270, 189–194.

Töwe, S., Albert, A., Kleineidam, K., Brankatschk, R., Dümig, A., Welzl, G., Munch, J., Zeyer, J., and Schloter, M. (2010). Abundance of microbes involved in nitrogen transformation in the rhizosphere of Leucanthemopsis alpina (L.) Heywood grown in soils from different sites of the Damma glacier forefield. Microb. Ecol. 60, 762–770.

Whitford, W. G. (1992). Biogeochemical consequences of desertification. ACS Symp. Ser. 483, 352–359.

Wolsing, M., and Priemé, A. (2004). Observation of high seasonal variation in community structure of denitrifying bacteria in arable soil receiving artificial fertilizer and cattle manure by determining T-RFLP of nir gene fragments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 48, 261–271.

Keywords: denitrifiers, nirK and nirS, semiarid soil, desert soil, Chile

Citation: Orlando J, Carú M, Pommerenke B and Braker G (2012) Diversity and activity of denitrifiers of Chilean arid soil ecosystems. Front. Microbio. 3:101. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00101

Received: 06 January 2012; Paper pending published: 26 January 2012;

Accepted: 29 February 2012; Published online: 05 April 2012.

Edited by:

Lisa Y. Stein, University of Alberta, CanadaReviewed by:

Joana Falcão Salles, University of Groningen, NetherlandsCopyright: © 2012 Orlando, Carú, Pommerenke and Braker. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in other forums, provided the original authors and source are credited.

*Correspondence: Gesche Braker, Department of Biogeochemistry, Max Planck Institute for Terrestrial Microbiology, Karl-von-Frisch-Strasse 10, 35043 Marburg, Germany. e-mail:YnJha2VyQG1waS1tYXJidXJnLm1wZy5kZQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.