- 1HTAi Patient and Citizen Involvement Interest Group (PCIG) Chair, Brunswick, VIC, Australia

- 2Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Alliance (PAPAA), St Albans, United Kingdom

- 3Patient Advocates in Research (PAIR), Danville, CA, United States

- 4Patient Expert European and Dutch Lung Foundation, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 5Spanish Platform European Patients' Academy on Therapeutic Innovation (EUPATI), Madrid, Spain

- 6Acute Leukemia Advocates Network and Leukaemia Patient Advocates Foundation, Bern, Switzerland

Health technology assessment (HTA) is intended to determine the value of health technologies and, once a technology is recommended for funding, bridge clinical research and practice. Understanding the values and beliefs expressed by patients and health professionals can help guide this knowledge transfer and work toward managing the expectations of end users. We gathered patient and patient group leader experiences to gain insights into the roles that patients and patient advocacy groups are playing. We argue that through partnerships and co-creation between HTA professionals, researchers and patient advocates we can strengthen the HTA process and better align with service delivery where person-centered care and shared decision making are key elements. Patient experiences and knowledge are important to the democratization of evidence and the legitimacy of HTAs. Patient preference studies are used to balance benefits with potential harms of technologies, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) can measure what matters to patients over time. A change in culture in HTA bodies is occurring and with further transformative thinking patients can be involved in every step of the HTA process. Patients have a right to be involved in HTAs, with patients' values central to HTA deliberations on a technology and where patients can provide valuable insights to inform HTA decision-making; and in ensuring that HTA methodologies evolve. By evaluating the implementation of HTA recommendations we can determine how HTA benefits patients and their communities. Our shared commitment can positively effect the common good and provide benefits to individual patients and their communities.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about many changes in our healthcare systems. Some of these can provide benefits for patients, such as widespread use of telemedicine and decentralized clinical trials (1). We have also seen many shortcomings regarding access to medicines and vaccines; and how we get more evidence and context to decision makers, clinicians and the public. Regulators, health technology assessment (HTA) bodies, payers and industry have learned the value of aligning their processes, engaging with each other and creating more opportunities for international cooperation (2). Better alignment can convey information to decision makers in a timely fashion and assist them in dealing with uncertainty and change (2). The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) as the UK regulator for market access has worked with patient advocates to develop and release its first patient involvement strategy (3), placing it in line with, for example, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) (4) and U.S. Food & Drugs Administration Agency (FDA) (5).

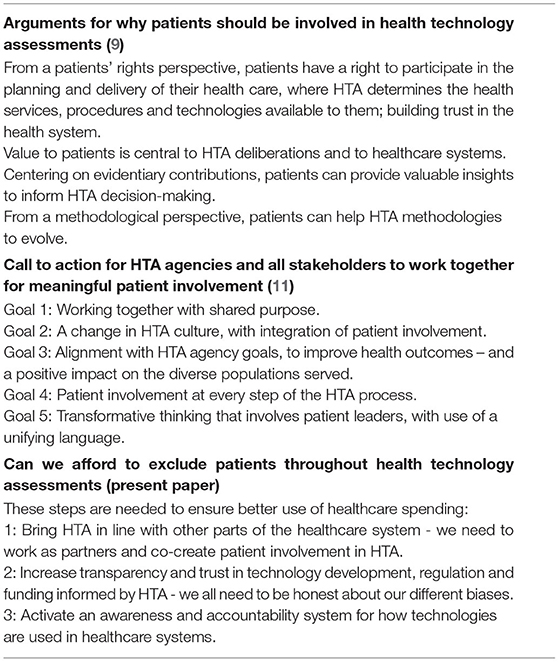

HTA is intended to bridge clinical research and clinical practice, and to determine the value of health technologies (6, 7). Understanding the values and beliefs expressed by patients and health professionals can help guide knowledge transfer from clinical trials to practice, and work toward matching the realities and expectations of end-users (8). Over recent years we have seen a progression from “should we involve patients” in HTAs (9), “can we afford to involve patients” (10), and a “call to action” (11) to the present situation with COVID-19 that indicates we cannot afford to leave patients out of HTAs (see Table 1). Partnership approaches are important to keep HTA aligned with the rest of the healthcare system where person-centered care and shared decision-making are key elements [e.g., (12)].

Involving Patients in HTA

HTA addresses important questions that patients and clinicians share, including: does the technology work? If so, for whom, how well, and at what cost? Does it provide value for individual patients and the health system, does it fit within care pathways, and is it worth funding, largely on the basis of “cost” (7)? A health technology includes drugs, diagnostic tests, medical devices and healthcare procedures. HTA is defined on the basis of scientific rigor and evidence, with multi-stakeholder deliberations to appraise the evidence (13). The patient perspective is important in the democratization of evidence. Co-creation with patients can add to the legitimacy of the HTA process for the common good (14). Currently patient involvement is limited in its scope and barriers to their involvement include the lack of information to patients and public about HTA and the lack of policies (15–17), and the need for culture change (18–21). The “invited spaces” for patient participation have been set by HTA policy and practice and leave significant opportunities for broadening through mutual discussions (22). Public representatives have a place on the appraisal committees in a number of countries (17, 23, 24) and in some healthcare systems patients are payers in addition to being the focal point of what healthcare is about. As payers, patients are legitimate stakeholders within HTA. Their role as a payer can cause financial distress for patients (25). HTA is therefore an important methodology for health systems to make decisions on what services and technologies are funded and for universal health coverage (26).

Public awareness of healthcare has grown as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in how infectious diseases spread, public health preventive actions, vaccine development, adverse effects of health technologies, regulatory processes, and the availability and distribution of protective clothing, medical interventions and vaccines. Healthcare systems have been stretched in many ways, including their capacities, access to equipment and technologies aggravated by arguments about how the disease is spread, use of face masks, and the science (27). These health system stresses have often meant that patient-centered healthcare has been side-lined, leaving people in critical conditions without their loved ones around them (28). Communication and support, including access to digital technologies, can be limited particularly for marginalized and vulnerable population groups (1).

In its June 2021 position statement, the International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment (INAHTA) stated that “Patient involvement is recognized by INAHTA as an important and valuable element in the conduct of HTA” (29). In a plenary session of the HTAi 2021 Annual Meeting on “Patients at the Heart of Innovation” a call was made for person-centered HTA (30). There appears to be consensus that “we can do more, and do better.” HTA bodies calling for patient input often rely on patient groups to provide input that helps inform deliberations (24). Once received, patient input can be difficult to incorporate into the committee papers and formal assessment (20, 31, 32). Discussions are taking place to overcome at least some of these barriers (33). On occasion, the information provided fills a gap in knowledge or understanding of the appraisal committee (34, 35). And patients can make a difference as evidenced by an example of an assessment in sickle cell anemia for the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). The sickle cell patient community highlighted “the appalling trade-off between choosing to manage intolerable pain from home or choosing to go to the emergency room, where many are met with racial prejudice, uninformed medical professionals, and a constant need to advocate for adequate pain management.” Patients needed to meet a prior authorization requirement for opioid pain management, which hinders their access (https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICER_SCD_Response-to-Comments_031220.pdf). This raises the issue of need to optimize overall healthcare when providing a medicine or technology for treatment of a health condition.

Are We Seeing Changes in Approach?

HTA professionals are looking to more “scientific” ways to provide patients' perspectives, as with syntheses of qualitative studies to provide patient evidence (36). Patient preference studies are now being extended beyond economic studies to build clinical trial evidence for an intervention or technology (37–40). Uptake in the USA has been slow (41, 42). In Europe however the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) funded PREFER (https://www.imi-prefer.eu/about/) project involves patient groups to provide guidance for industry, regulatory authorities and HTA bodies on how and when to include patient preference studies on benefits and risks of medicines. The PREFER framework covers validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), clinician-reported outcomes and observer-reported outcomes within a disease setting. These are used to weight the clinical trial evidence. How preference studies relate to patient input into HTA processes and actively involving patient advocates and patient advocacy groups is less clear. The IMI H2O Health Outcomes Observatory project (https://health-outcomes-observatory.eu/) involves patient groups and is creating a data governance and infrastructure model to collect PROMs and incorporate them into healthcare decision making at an individual and population level. Patients have ultimate control of their health data in this project. Qualitative studies that are used to inform patient preference studies are the type of studies that would make PROMs more meaningful and could help individual patients and patient groups better monitor their health conditions and the effects of treatments (43–45). As examples, Janssens et al. (45) showed that for people with multiple myeloma life extension is not the only thing they want from treatment. They want to retain the ability to carry out their daily activities and to maintain independence and mobility. Permanent and severe side-effects and symptoms are of concern to them. ICER noted that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approvals covering drugs for relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) were based on reductions in the number of relapses. Patients told ICER that accumulating longer-term functional disabilities were the most important outcome for them (ICER HTAi 2021 presentation—personal communication). In an oral presentation at the same meeting, patient advocates highlighted the importance of upper body function and independent living for people with progressive MS who were in wheelchairs (https://youtu.be/hB_eII-b0P8). PROMs are important in capturing “what matters” to patients (46). Patient groups are already forming partnerships to develop apps to personally collect data to monitor and report on their condition, its evolution and the effects of interventions. An example is “Patient Voice – myGUT” in collaboration with Microsoft (personal communication).

Patient-reported data not only has the capacity to empower patients in managing their own health condition but also contributes to broader knowledge that can inform healthcare more generally, including HTAs (47, 48). Patients have felt that they are peripheral to the HTA process and that their involvement takes place too late in the process to make any real difference. Patient involvement is needed early and through all stages of the HTA process from topic selection, scoping, examining evidence, appraisal committee deliberation to determine value, and in formulating recommendations for funding or subsidy (11, 29). An early experience from one co-author, as a “patient expert” at an HTA appraisal, highlights this:

“I was led into a room with a very large table. Everyone had their heads down and were very intent on what was in front of them. When prompted, I started talking but I was very quickly interrupted and told they had read my “testimonial statement” in the committee papers. They did not need anything more from me... I went there to provide a voice to the voiceless, but left feeling that I had been gagged…” Patient advocate

This example and others from the literature (11, 23, 32, 49) highlight that we need to address what patients and patient groups are being asked to do in HTA and why.

How Can we Facilitate Change?

We advocate that collectively, and at all stages of the HTA process, we can integrate the voices of patients, their advocates and support groups. We propose working together to democratize HTA processes, from governance to making recommendations on specific interventions. We see this as a right (9). Frank, comprehensive and respectful conversations are needed with patient advocates and patient advocacy groups about where and how they can provide fruitful, positive and meaningful contributions, and what impacts and benefits these can achieve.

Currently, patient advocates and patient groups may not have a clear understanding of the earlier stages in the development of the technology and in the HTA process, or know if patients or patient groups were involved. They also need clarity about what treatments are already available, at what cost, with what treatment effectiveness, burden and side-effects, and for which sub-groups of patients. Background and landscape analyses can help patients offer more complete understanding and perspectives on the value of a particular technology as they explore and explain the trade-offs that patients must face. Yet scientific and medical jargon can deter patients from joining conversations. Health literacy principles apply and facilitate learning and mutual understanding (22, 50). Patient and public participation should have a direct effect on policy and decisions with inclusion of people's values, ideas and sentiments such that all participants can “live with the result” (22).

Transparency and trust in technology development, regulation and funding informed by HTA can be increased if we all are transparent about our different perspectives, limitations and biases. We also need open discussion on the conflicts of interest of each person involved. For example, HTA appraisal committees may be uncomfortable hearing about individual patient experiences and unmet needs (49), or they may not see the relevance of patients being present.

“Patients/patient group representatives are often not really listened to when they speak. The expectation is that they just want the new [better] technology, and they are in league with industry anyway.” Patient advocate

Yet, “patient advocates tend to change the environment and tenor of the discussion. This gives people on all sides the space to say things they may not normally feel comfortable saying—when “we let them”.” Patient advocate

An example from ICER shows where a new treatment for sight loss (blindness) failed to achieve traditional measures of cost-effectiveness. Patients and their families conveyed how extensive the benefits of better sight (even partial) are for the entire family through improvements in school, work, and social functioning. ICER developed an alternative economic model incorporating these benefits that was accepted as a reasonable long-term value (HTAi 2021 presentation, personal communication). The value for patient communities needs to be clear. It is also important to understand at the start what the place of the technology is: is it a “breakthrough” technology, another me too, an older product revitalized? This can have an impact on the amount of time patient advocacy groups spend on preparing patient input.

“On an HTA appraisal committee I was asked why I was not supporting approval of a cheaper, less effective drug. I was able to state very clearly because if approved it would be used and would make it more difficult for patients to access treatments that were much more likely to be effective, and so prolong their discomfort and suffering.” Patient advocate

“We need to challenge patient groups to take more responsibility for better outcomes for their patients by insisting that we get better, not just more, treatments. And that they add value to patients' lives without causing them to go bankrupt.” Patient advocate

“We should show how we represent a group of patients, not just our own experience. Part of the responsibility of an HTA patient advocate is to give a spectrum of issues and experiences. This approach helps build our credibility, and necessitates our authority as peers with specific expertise on the perspectives of service users.” Patient advocate

In recent years patient advocates and their organizations have become better informed, educated and trained to concentrate on their patients' experiences and knowledge so to effectively contribute to regulatory and HTA decision-making [e.g., (37, 51–53)]. They are also involved in clinical trial design (54, 55). Now we need to co-create and democratize the evidence (56). Patient advocates and patient advocacy groups need to have access to comprehensive, informative data on the technology they are being asked to comment on, which often does not happen (22). The justification of not sharing the data on a technology is that manufacturers need to protect confidential and proprietary information, and laws on “advertising prescription technologies” to the public that interrupt adequate flows of information (57). A non-disclosure agreement (NDA) is already used by the HTA body for the other members of the committee and can also be used for patients. Clinical trial reports may be behind journal paywalls or not accessible to the public; similarly comparative data, longer-term and real-world data. Some HTAs have tried to resolve these limitations. The Scottish Medicines Consortium “Summary of Information for Patients” (SIP) is a simple summary of clinical trial data for patient groups to be provided by industry as part of its product submission that is being used to develop similar processes in other countries (58). While promising, the authors of this paper are concerned that industry may essentially control what patient advocacy groups know about the new technologies.

“We are “selling” something to patients without giving them the background information and evidence-base that they need to be able to make rational choices/judgements.” Patient Advocacy Group

Germany's Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) ensures that its patient advocates receive full information (59), HTAi 2019 PCIG workshop—personal communication], demonstrating that “political commitment” can overcome these information barriers (22). “Partnership synergy” is the ability to work together by combining resources in order to produce an output that cannot otherwise be achieved by single agents (22). This is for “the common good” and fosters democratic discussions where the quality of the dialogue is dependent on the quality of the information provided, together with a trusting relationship between participants (22).

Finally, optimizing and measuring how technologies are used would ensure the most effective use of technologies, and how healthcare systems could derive the greatest benefit from them. HTAs often ask medical professionals, researchers and public members of an appraisal committee to judge what patients think about a new treatment and its potential benefits and harms, ironically while restricting patient advocate and patient advocacy group input. Information directly from the source is always more reliable.

“The regulatory and approval systems focus on efficacy of the product, not effectiveness of its use in or with people. The public is not told about this difference and often assumes that the product is effective when this has not been evaluated...” Patient advocate (US)

Steps to Lead Forward

Working together in partnership is transformative and can help HTA bodies to understand how to invest in active, meaningful patient engagement (22, 60). Patient participation can help to ensure that HTA agencies are aligned with the end-users [(11), https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/ICER_Lupus-Nephritis_Policy-Recommendations_041621.pdf].

A system to monitor and provide feed-back on how technologies are being utilized within the healthcare system, and for whom, could complete the loop for evaluating the implementation of HTA recommendations. This can create a “learning HTA and healthcare environment” that measures outcomes to inform them and builds on value over time [US Agency for Health care Research and Quality (AHRQ) https://www.ahrq.gov/learning-health-systems/index.html]. In the longer-term we would all learn to trust and benefit from availability of the most appropriate and effective technologies.

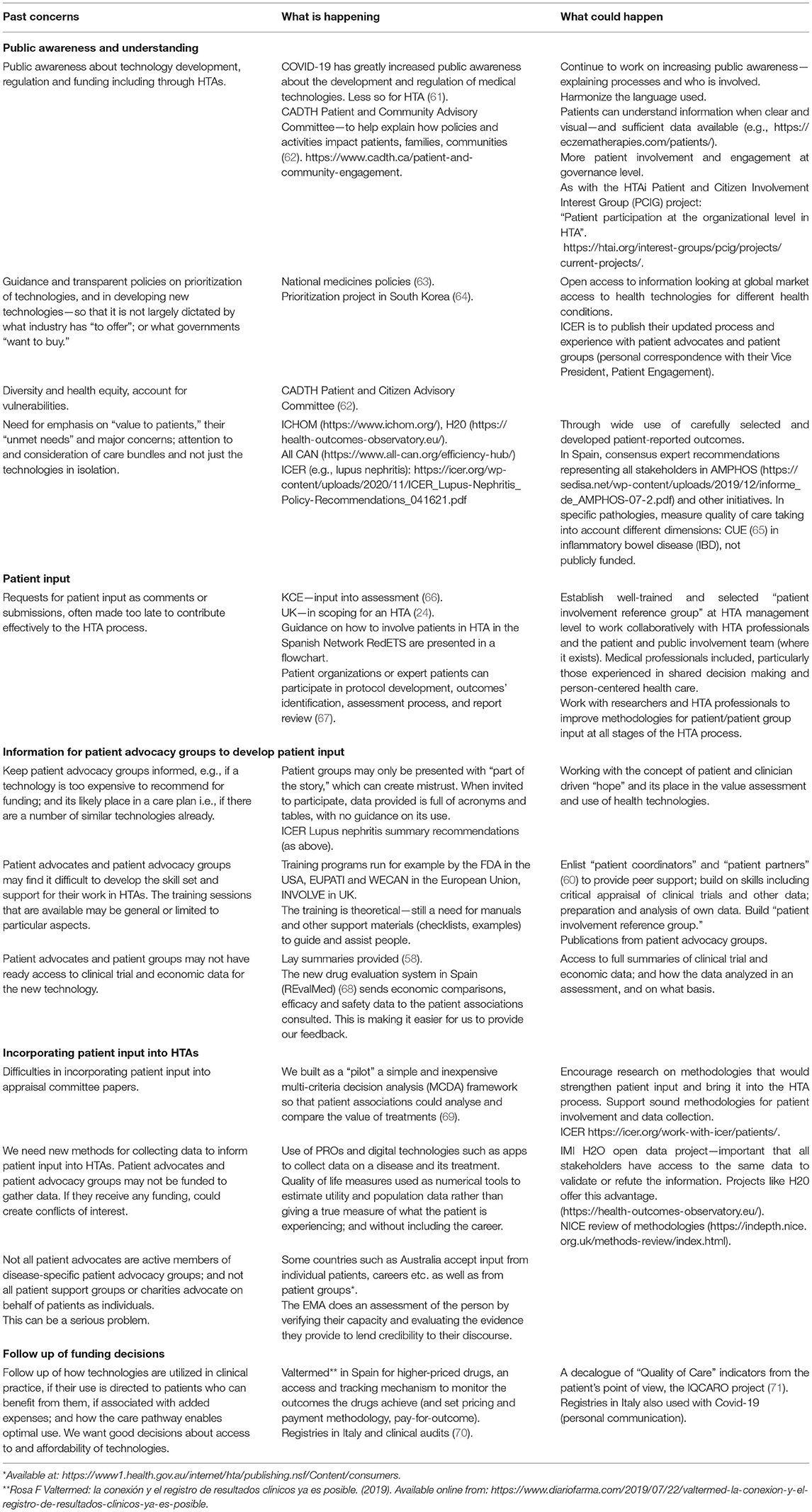

In Table 2 we have summarized our concerns together with examples of what is being done related to HTA bodies.

Table 2. Patient advocate and patient advocacy group concerns with examples of what is being done related to HTA bodies.

Conclusions

Patient advocates and patient advocacy group leaders share common interests and goals with HTA bodies regarding good decisions about access to, and affordability of health technologies. Greater benefit and effectiveness can be generated by integrating patient advocates and patient advocacy groups into HTAs, rather than treating them as separate from decision-making bodies. Good progress is being made by the HTA community. It is now time to develop consistent emerging practices globally, and to measure the results of HTA recommendations in ways that benefit the health and welfare of patients and their communities. We call on HTA leadership to work with us to build pro-active, iterative participatory methods that engage and integrate patient input into the technology development and HTA continuum. Our shared commitment can positively affect the common good as well as provide benefits to individual patients and their communities.

Definition of Terms as Used in This Paper

Co-creation, co-design and co-production: Terms used interchangeably in this document to describe equal status partnerships between patient leaders and HTA bodies.

Democratization of evidence: Developing a better understanding and use of evidence.

Legitimacy: Where “democratic legitimacy” incorporates a broader view of evidence to inform efficacy, utility, and effectiveness; through inclusion and equity of allocation of resources.

“Scientific legitimacy” involves the application of scientific rigor and objectivity, leading to scientific policy goals rather than population goals.

Healthcare technologies: Services, diagnostics, medicines, medical devices and digital devices for use in health care.

Patient input: Includes patient advocates/patient group representatives on a committee, patient experts presenting at a committee meeting, and patient and patient group submissions for an HTA. This can also include caregivers.

Patient leaders: Patient advocates and patient advocacy groups who are active in building and strengthening patient involvement in HTAs. We describe patient leaders as people who can envision where changes to bring about solutions can take place, and work with others to enable change. McNally (72) used the term “patient leadership” to describe an investment in patient and career leaders working collaboratively in co-creation, co-design and co-production projects.

Patient and public involvement and engagement: A purpose of patient involvement in HTA is to improve the legitimacy of decision making; and is instrumental in producing better quality decisions that reflect patient and public preferences and values, through transparent, accountable, legitimate processes.

Person-centered HTA: The involvement of patients throughout the HTA process to build on patient input that has taken place in earlier stages of technology development, such as in basic research, patient preference studies, clinical trials and in being part of regulatory processes. This term was first publicly used at the plenary session “Patients at the heart of innovation” during the HTAi 2021 Annual Meeting (30).

Service end users: People who use the healthcare system for prevention or for treatment. Most often known as “patients.”

Stakeholder: Any group or individual who can affect or is affected.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

JW, DCh, DCo, DH, RS, and ZP-W contributed to the discussions and preparation of this manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Yvette Venable of ICER for her contribution to the content of this manuscript and the many patient advocates, patient advocacy groups and associated clinicians world-wide who are actively involved in promoting patient voices in health technology assessments and related areas.

Abbreviations

App, mobile device application; CADTH, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health; EMA, European Medicines Agency; EUPATI, European Patients’ Academy on Therapeutic Innovation, ; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; G-BA, The Federal Joint Committee, Germany; HTAi, health technology assessment international; ICER, Institute for Clinical and Economic Review; KCE, Belgium Health Care Knowledge Center; MHRA, Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, UK; NICE, The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, England; PCIG, HTAi Patient and Citizen Involvement in HTA Interest Group; PRO, patient-reported outcome; SMC, Scottish Medicines Consortium.

References

1. Yamey G, Pai M. How COVID-19 Is Revolutionizing Health Care Around the World. Time Magazine. (2021). Available online at: https://time.com/6052677/covid-19-health-care-innovations/ (accessed June 10, 2021).

2. McGurn S. Changing Landscape of Evidence Charting New Assessment Pathways. Q&A with Canadian Agency for Drugs Technologies in Health (CADTH). DIA Global Forum (2021). Available online at: https://globalforum.diaglobal.org/issue/october-2021/changing-landscape-of-evidence-charting-new-assessment-pathways/ (accessed October 1, 2021).

3. Medicines, & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Patient Involvement Strategy 2021-25. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1022370/Patient_involvement_strategy.pdf (accessed October 5, 2021).

4. European, Medicines Agency (EMA). Partners & Networks. Patients and Consumers. Available online at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/partners-networks/patients-consumers/getting-involved (accessed October 1, 2021).

5. U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA). Patient Engagement. Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/patients/learn-about-fda-patient-engagement (accessed October 1, 2021).

6. About, CADTH. Delivering Value to Canadians. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health (CADTH). Available online at: https://www.cadth.ca/index.php/about-cadth (accessed October 1, 2021).

7. Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. (2010) 363:2477–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024

8. Landry R, Amara N, Pablos-Mendes A, Shademani R, Gold I. The knowledge-value chain: a conceptual framework for knowledge translation in health. Bull World Health Organ. (2006) 8:597–602. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.031724

9. Wale J, Scott AM, Hofmann B, Garner S, Low E, Sansom L. Why patients should be involved in health technology assessment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2017) 1:1–4. doi: 10.1017/S0266462317000241

10. O'Rourke B, Werkö SS, Merlin T, Huang LY, Schuller T. The 'Top 10' challenges for health technology assessment: INAHTA viewpoint. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2020) 36:1–4. doi: 10.1017/S0266462319000825

11. Wale JL, Thomas S, Hamerlijnck D, Hollander R. Patients and public are important stakeholders in health technology assessment but the level of involvement is low - a call to action. Res Involv Engagem. (2021) 7:1. doi: 10.1186/s40900-020-00248-9

12. Australian Australian Commission on Safety and Quality of Health Care National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards Partnering with Consumers Standard. Available online at: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards/partnering-consumers-standard (accessed September 15, 2021).

13. O'Rourke B, Oortwijn W, Schuller T, International Joint Task Group. The new definition of health technology assessment: a milestone in international collaboration. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2020) 36:187–90. doi: 10.1017/S0266462320000215

14. Goetghebeur M, Cellier M. Deliberative processes by health technology assessment agencies: a reflection on legitimacy, values and patient and public involvement: Comment on “Use of evidence-informed deliberative processes by health technology assessment agencies around the globe.” Int J Health Policy Manag. (2020) 10:228–31. doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.46

15. Gauvin FP, Abelson J, Giacomini M, Eyles J, Lavis JN. “It all depends”: conceptualizing public involvement in the context of health technology assessment agencies. Soc Sci Med. (2010) 70:1518–26. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.036

16. Abelson J, Wagner F, DeJean D, Boesveld S, Gauvin FP., Bean S, et al. Public and patient involvement in health technology assessment: a framework for action. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2016) 32:256–64. doi: 10.1017/S0266462316000362

17. Gagnon MP, Tantchou Dipankui M, Poder TG, Payne-Gagnon J, Mbemba G, Beretta V. Patient and public involvement in health technology assessment: update of a systematic review of international experiences. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2021) 37:e36. doi: 10.1017/S0266462321000064

18. Boothe K. “Getting to the table”: changing ideas about public and patient involvement in Canadian drug assessment. J Health Polit Policy Law. (2019) 44:631–63. doi: 10.1215/03616878-7530825

19. Boothe K. (Re)defining legitimacy in Canadian drug assessment policy? Comparing ideas over time. Health Econ Policy Law. (2021). 16:424–39. doi: 10.1017/S1744133121000013

20. Bidonde J, Vanstone M, Schwartz L, Abelson J. An institutional ethnographic analysis of public and patient engagement activities at a national health technology assessment agency. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2021) 37:e37. doi: 10.1017/S0266462321000088

21. Cleemput I, Dauvrin M, Kohn L, Mistiaen P, Christiaens W, Léonard C. Developing an agency's position with respect to patient involvement in health technology assessment: the importance of the organizational culture. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2020) 36:569–78. doi: 10.1017/S0266462320000513

22. Pagatpatan CP, Ward PR. Understanding the factors that make public participation effective in health policy and planning: a realist synthesis. Aust J Prim Health. (2017) 23:516–30. doi: 10.1071/PY16129

23. Scott AM, Wale JL. HTAi Patient and Citizen Involvement in HTA Interest Group, Patient Involvement and Education Working Group. Patient advocate perspectives on involvement in HTA: an international snapshot. Res Involv Engagem. (2017) 3:2. doi: 10.1186/s40900-016-0052-9

24. Norburn L, Thomas L. Expertise, experience, and excellence. Twenty years of patient involvement in health technology assessment at NICE: an evolving story. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2020) 37:e15. doi: 10.1017/S0266462320000860

25. Collyar DE. Time to treat financial toxicity for patients. Cancer J. (2020) 26: 292–297. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000466

26. Sixty-seventh World Health Assembly WHA67.23 Agenda Item 15.7, 24 May 2014. Health Intervention and Technology Assessment in Support of Universal Health Coverage. (2014). Available online at: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_R23-en.pdf (accessed December 20, 2020).

27. Czypionka T, Greenhalgh T, Bassler D, Bryant MB. Masks and face coverings for the lay public: a narrative update. Ann Intern Med. (2021) 174:511–20. doi: 10.7326/M20-6625

28. Greenhalgh T. Moral uncertainty: a case study of Covid-19. Patient Educ Couns. (2021) 104:2643–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.07.022

29. The International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment (INAHTA) Position Statement: Patient involvement is recognised by INAHTA as an important valuable element in the conduct of Health Technology Assessment (HTA). (2021). Available online at: https://www.inahta.org/position-statements/ (accessed September 15, 2021).

30. HTAi 2021 Innovation Through HTA Annual Meeting. Plenary “Patients at the Heart of Innovation.” Available online at: https://htai.eventsair.com/htai-manchester-2021-am/plenaries (accessed October 6, 2021).

31. Staley K, Doherty C. It's not evidence, it's insight: bringing patients' perspectives into health technology appraisal at NICE. Res Involv Engagem. (2016) 2:4. doi: 10.1186/s40900-016-0018-y

32. Wale J, Sullivan M. Exploration of the visibility of patient input in final recommendation documentation for three health technology assessment bodies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2020) 36:197–203. doi: 10.1017/S0266462320000240

33. Rasburn M, Livingstone H, Scott SE. Strengthening patient outcome evidence in health technology assessment: a coproduction approach. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2021) 37:e12. doi: 10.1017/S0266462320002202

34. Facey KM, Bedlington N, Berglas S, Bertelsen N, Single ANV, Thomas V. Putting patients at the centre of healthcare: progress and challenges for health technology assessments. Patient. (2018) 11:581–9. doi: 10.1007/s40271-018-0325-5

35. Livingstone H, Verdiel V, Crosbie H, Upadhyaya S, Harris K, Thomas L. Evaluation of the impact of patient input in health technology assessments at NICE. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2021) 37:e33. doi: 10.1017/S0266462320002214

36. Staniszewska S, Söderholm Werkö S. Mind the evidence gap: the use of patient-based evidence to create “complete HTA” in the twenty-first century. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2021) 37:e46. doi: 10.1017/S026646232100012X

37. U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA). CDER Patient-Focused Drug Development. Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/development-approval-process-drugs/cder-patient-focused-drug-development

38. Whitty JA, de Bekker-Grob EW, Cook NS, Terris-Prestholt F, Drummond M, et al. Patient preferences in the medical product lifecycle. Patient. (2019) 13:7–10. doi: 10.1007/s40271-019-00400-y

39. Chachoua L, Dabbous M, François C, Dussart C, Aballéa S, Toumi M. Use of patient preference information in benefit–risk assessment, health technology assessment, and pricing and reimbursement decisions: a systematic literature review of attempts and initiatives. Front Med. (2020) 7:543046. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.543046

40. Whichello C, van Overbeeke E, Janssens R, Schölin Bywall K, Russo S, Veldwijk J, et al. Factors and situations affecting the value of patient preference studies: semi-structured interviews in Europe and the US. Front Pharmacol. (2019) 10:1009. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01009

41. Kieffer CM, Miller AR, Chacko B, Robertson AS. FDA reported use of patient experience data in 2018 drug approvals. Ther Innov Regul Sci. (2019) 54:709–16. doi: 10.1177/2168479019871519

42. Gnanasakthy A, Barrett A, Evans E, D'Alessio D, Romano CD. A review of patient-reported outcomes labeling for oncology drugs approved by the FDA and the EMA (2012-2016). Value Health. (2019) 2:203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.09.2842

43. Louis E, Ramos-Goñi JM, Cuervo J, Kopylov U., Barreiro-de Acosta M, McCartney S, et al. A qualitative research for defining meaningful attributes for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease from the patient. Perspective Patient. (2020) 3:317–25. doi: 10.1007/s40271-019-00407-5

44. Cook NS, Cave J, Holtorf AP. Patient preference studies during early drug development: aligning stakeholders to ensure development plans meet patient needs. Front Med. (2019) 6:82. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00082

45. Janssens R, Lang T, Vallejo A, Galinsky J, Plate A, Morgan K, et al. Patient preferences for multiple myeloma treatments: a multinational qualitative study. Front Med. (2021) 8:686165. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.686165

46. Calvert MJ, O'Connor DJ, Basch EM. Harnessing the patient voice in real-world evidence: The essential role of patient-reported outcomes. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2019) 18:731–2. doi: 10.1038/d41573-019-00088-7

47. Addario B, Geissler J, Horn MK, Krebs LU, Maskens D, Oliver K, et al. Including the patient voice in the development and implementation of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. Health Expect. (2019) 23:41–1. doi: 10.1111/hex.12997

48. Schmidt T, Valuck T, Perkins B, Riposo J, Patel P, Westrich K, et al. Improving patient-reported measures in oncology: a payer call to action. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. (2021) 1:118–26. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2020.20313

49. Hashem F, Calnan MW, Brown PR. Decision making in NICE single technology appraisals: how does NICE incorporate patient perspectives? Health Expect. (2018) 1:128–37. doi: 10.1111/hex.12594

50. Okan O, Bauer U, Levin-Zamir D, Pinheiro P, Sørensen K, editors. International Handbook of Health Literacy. Research, Practice Policy Across the Lifespan. Bristol: Policy Press (2019). p. 764. Available online at: https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/24879 (accessed September 15, 2021)

51. National Institute for Health Research. National Standards for Public Involvement. Available online at: https://www.invo.org.uk/posttypepublication/national-standards-for-public-involvement/ (accessed February 25, 2020).

52. EUPATI Toolbox. Available online at: https://toolbox.eupati.eu/ (accessed September 29, 2021).

53. WECAN Academy Knowledge Base. Available online at: https://wecanadvocate.eu/academy/ (accessed on September 15, 2021).

54. Collyar DE, Gautier LJ. The importance and value of engaging patients in cancer research. Future Oncol. (2021) 28:3663–6. doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-0856

55. Katz ML, Archer LE, Peppercorn JM, Kereakoglow S, Collyar DE, Burstein HJ, et al. Patient advocates' role in clinical trials: perspectives from Cancer and Leukemia Group B investigators and advocates. Cancer. (2012) 18:4801–5. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27485

56. Deane K, Delbecque L, Gorbenko O, Hamoir AM, Hoos A, Nafria B, et al. Co-creation of patient engagement quality guidance for medicines development: an international multistakeholder initiative. BMJ Innov. (2019) 1:43–55. doi: 10.1136/bmjinnov-2018-000317

57. European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA). EFPIA code of practice on relationships between the pharmaceutical industry and patient organisations. Brussels: EFPIA (2011).

58. Cook N, Livingstone H, Dickson J, Taylor L, Morgan K, Coombes M, et al. Development of an international template to support patient submissions in Health Technology Assessments. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2021) 1:e50. doi: 10.1017/S0266462321000167

59. Haefner S, Danner M. Germany. In: Facey K, Ploug Hansen H, Single A, editors. Patient Involvement in Health Technology Assessment. Singapore: Springer (2017). p. 299–312. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-4068-9_25

60. Pomey MP, Bush PL, Demers-Payette O. L'Espérance A, Lochhead L, Ganache I, Roy D. Developing recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease: the role of the patient's perspective in a controversial environment. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2020) 37:e11. doi: 10.1017/S0266462320002123

61. O'Rourke B, Orsini LS, Guerino J. COVID-19: Challenges and Opportunities for the Global Health Technology Assessment Community. Available online at: https://www.ispor.org/publications/journals/value-outcomes-spotlight/vos-archives/issue/view/expanding-the-value-conversation/covid-19-challenges-and-opportunities-for-the-global-health-technology-assessment-community?utm_medium=email&utm_source=database&utm_campaign=value_and_outcomes_spotlight&utm_content=vos_highlight_email&utm_term=vos+highlight+email&_zs=3hXOX&_zl=v5wg2 (accessed September 29, 2021).

62. Berglas S, Vautour N, Bell D. Creating a patient and community advisory committee at the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2021) 37:e19. doi: 10.1017/S0266462320002251

63. WHO Policy Perspectives on Medicines - How to Develop and Implement a National Drug Policy. Geneva: World Health Organization (2003). p. 6. Available online at: https://www.who.int/management/background_4b.pdf

64. Bae EY, Lim MK, Lee B, Bae G. Who should be given priority for public funding? Health Policy. (2020) 124:1108–14. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2020.06.010

65. Barreiro-de Acosta M, Gutiérrez A, Zabana Y, Beltrán B, Calvet X, Chaparro M, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease integral care units: evaluation of a nationwide quality certification programme. The GETECCU experience. United Eur Gastroenterol J. (2021) 9:766–72. doi: 10.1002/ueg2.12105

66. Cleemput I, Dauvrin M, Kohn L, Mistiaen P, Christiaens W, Léanard C. KCE Reports 320: Position of KCE on Patient Involvement in Health Care Policy Research. (2019). Available online at: https://kce.fgov.be/en/position-of-kce-on-patient-involvement-in-health-care-policy-research (accessed March 16, 2020).

67. Toledo-Chávarri A, Gagnon M, Álvarez-Pérez Y, Perestelo-Pérez L, Triñanes Pego Y. Serrano Aguilar P. Development of a decisional flowchart for meaningful patient involvement in health technology assessment. Int J Tech Assess Health Care. (2021) 37:E3. doi: 10.1017/S0266462320001956

68. Revalmed (Spanish),. (2020). Available online at: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/farmacia/IPT/docs/20200708.Plan_de_accion_para_la_consolidacion_de_los_IPT.actCPF8Julio.pdf

69. Roldán ÚB, Badia X, Marcos-Rodríguez JA, de la Cruz-Merino L, Gómez-González J, Melcón-de Dios A, et al. Multi-criteria decision analysis as a decision-support tool for drug evaluation: a pilot study in a pharmacy and therapeutics committee setting. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. (2018) 34:519–26. doi: 10.1017/S0266462318000569

70. Xoxi E, Facey KM, Cicchetti A. The evolution of AIFA registries to support managed entry agreements for orphan medicinal products in Italy. Front Pharmacol. (2021) 12:699466. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.699466

71. Calvet X, Saldaña R, Carpio D, Mínguez M, Vera I, Juliá B, et al. Improving quality of care in inflammatory bowel disease through patients' eyes: IQCARO project. Inflamm Bowel Dis. (2020) 26:782–91. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz126

Keywords: patient involvement, patient engagement, health technology assessment, value, person-centered, patient-reported outcomes, patient preference studies

Citation: Wale JL, Chandler D, Collyar D, Hamerlijnck D, Saldana R and Pemberton-Whitely Z (2022) Can We Afford to Exclude Patients Throughout Health Technology Assessment? Front. Med. Technol. 3:796344. doi: 10.3389/fmedt.2021.796344

Received: 16 October 2021; Accepted: 08 November 2021;

Published: 25 January 2022.

Edited by:

Hao Hu, University of Macau, ChinaReviewed by:

Rossella Di Bidino, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, ItalyEntela Xoxi, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Wale, Chandler, Collyar, Hamerlijnck, Saldana and Pemberton-Whitely. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Janet L. Wale, c29jcmF0ZXMxMTFAYmlnb2luZC5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Janet L. Wale

Janet L. Wale David Chandler

David Chandler Deborah Collyar

Deborah Collyar Dominique Hamerlijnck

Dominique Hamerlijnck Roberto Saldana5†

Roberto Saldana5†