95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Med. Technol. , 29 July 2021

Sec. Regenerative Technologies

Volume 3 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmedt.2021.670274

This article is part of the Research Topic Highlights in Regenerative Technologies 2021/22 View all 4 articles

Electrical stimulation (ES) is a well-known method for guiding the behaviour of nerve cells in in vitro systems based on the response of these cells to an electric field. From this perspective, understanding how the electrochemical stimulus can be tuned for the design of a desired cell response is of great importance. Most biomedical studies propose the application of an electrical potential to cell culture arrays while examining the cell response regarding viability, morphology, and gene expression. Conversely, various studies failed to evaluate how the fine physicochemical properties of the materials used for cell culture influence the observed behaviours. Among the various materials used for culturing cells under ES, conductive polymers (CPs) are widely used either in pristine form or in addition to other polymers. CPs themselves do not possess the optimal surface for cell compatibility because of their hydrophobic nature, which leads to poor protein adhesion and, hence, poor bioactivity. Therefore, understanding how to tailor the chemical properties on the material surface will determine the obtention of improved ES platforms. Moreover, the structure of the material, either in a thin film or in porous electrospun scaffolds, also affects the biochemical response and needs to be considered. In this review, we examine how materials based on CPs influence cell behaviour under ES, and we compile the various ES setups and physicochemical properties that affect cell behaviour. This review concerns the culture of various cell types, such as neurons, fibroblasts, osteoblasts, and Schwann cells, and it also covers studies on stem cells prone to ES. To understand the mechanistic behaviour of these devices, we also examine studies presenting a more detailed biomolecular level of interaction. This review aims to guide the design of future ES setups regarding the influence of material properties and electrochemical conditions on the behaviour of in vitro cell studies.

Since the discovery of conductive polymers (CPs) in the late 1970's, interest in these materials has steadily grown (1). Currently, there are a wide variety of new polymers and their derivatives, consisting basically of aromatic rings or linear chains with alternating single and double bonds, which allow the transport of electrons through conjugated π orbitals. These materials combine the electrical and optical properties of semiconductors with the mechanical and processing properties of polymers. Table 1 shows the structures of the most widely used CPs, which are applied in the development of rechargeable batteries, electrochromic devices, conductive plastics (2), drug-delivery devices (3), light-emitting diodes (4), sensors and biosensors (5, 6), electrocatalysis, and corrosion protection (7–9).

CPs generally present band gap (Eg) values higher than 1.5 eV, which makes them insulating materials. From oxidation or reduction of polymeric chains, decrease in Eg then happens, allowing these materials to become conductors. These processes occur with the formation of polarons, radical ions associated with distortion of the polymeric chain, and bipolarons, namely, pairs of similar charges associated with strong local distortions of the polymeric network (10). The value of Eg can be modulated by different functional groups. The substituent also influences properties, such as solubility, thermal stability, oxidation potential, electronic structure, and conductivity of the polymer (11).

PEDOT, for example, presents high conductivity and can be found in both neutral (reduced) and doped (oxidised) forms, with interconversion between forms taking place through primary and secondary doping processes. In general, the primary doping process of CPs refers to the addition of substances that decrease Eg, changing the electronic properties of the polymeric structure and enabling the electron conduction property (12). Secondary doping, according to MacDiarmid and Epstein (13), is the insertion of an apparently inert substance that provides an additional increase in the conductivity of a primarily doped polymer. Secondary doping differs from primary doping in that new enhanced properties can persist even with the complete removal of secondary doping. Doping reactions of the conjugated polymers are related to the transport of ions and electrons in the material. Depending on the types of charge compensation used during polymerisation, both insertion and release of cations and anions can occur during the electrochemical redox process. If a polyanion is used as a supporting electrolyte during the preparation of the CP, that polyanion is then immobile during redox processes, since it is incorporated into the polymer matrix on a molecular scale. Thus, two possible reactions take place during the doping/de-doping processes, as outlined in Equations 1, 2:

where A is the polyanion used during synthesis, and M+ and X− are the cation and anion of the salt used as a supporting electrolyte during electrochemical characterisation.

It has been reported that CPs, such as polypyrrole (PPy) and PEDOT doped with polysaccharides, namely, hyaluronic acid and heparin, can potentially be used in living tissue engineering as material for neural electrodes (14–16), because they can serve as biocompatible and biodegradable electroactive materials to increase the regeneration of peripheral nerves and other tissues (17). Lu et al. (18) and Yuk et al. (19) presented a way to produce a hydrogel made only of a mixture of PEDOT and polystyrene sulphonate (PEDOT:PSS) that could be 3D-printed, allowing the fabrication of devices with controllable shapes, which is important for tissue engineering applications. The authors printed a soft neural probe that could monitor the neural activities of a living mouse.

Among CPs, PPy is an intrinsic conductive polymer that has received considerable attention because of its high electrical conductivity and electrochemical stability (20). It is well-known in the literature that PPy can be found in different oxidising states. The degree of PPy doping leads to more or less conductive species, which are usually reversible, depending only on the amount of oxidant used or the potential applied to an electrode (21, 22). Studies have shown that it is able to support the in vitro growth of various types of cells (23). In vivo studies have also confirmed that PPy is non-cytotoxic to some extent, improving the interaction of nerve cell cultures to stimulate peripheral nerve regeneration (24). Knowing the concentration at which the polymer does not present cytotoxicity is fundamental for its applicability, especially in the biomedical area, to prevent toxicity and damage to the organism.

PANI is another widely used CP because of its highly conductive properties and its availability in different oxidation states, which can range from fully oxidised to fully reduced and are affected by pH. The most investigated form of PANI is the emeraldine base (PANI-EB), given its stability at room temperature and its transformation to the emeraldine salt form (PANI-ES) after doping with acid (protonated), a form that is known to be highly conductive (25).

It is worth mentioning that the development of biotechnological applications based on CPs usually includes the formation of blends and composites. Therefore, understanding the interactions among the components in the material is crucial for controlling the in vitro behaviour. Alemán et al. (26) assessed the interaction between CPs and DNA sequences, with major implications in numerous medical applications, from diagnosis to gene therapy. The interaction of post-doped electroactive materials with DNA was traditionally attributed to the tendency of DNA to interact with positively charged molecules. However, it has been found that some conductive polymers, such as PPy, are able to interact by forming specific interactions with well-defined nucleotide sequences of plasmid DNA. This selectivity suggests that the polymer-DNA hybrids are stabilised not only by electrostatic interactions but also by specific interactions depending on the chemical environment, spatial disposition, and orientation of the chemical groups.

Various studies have made use of the electrical nature of CPs to change their properties by applying ES (27–29). These procedures can also affect living structures attached to these materials by altering their chemical nature. During the eighteenth century, Luigi Galvani started research on frogs, analysing the effect of an electric field on the muscle-nerve system of the animal, which resulted in contractions. He concluded that there was some inherent electricity in the animal that could allow an external stimulus to flow in the body. For this study, Galvani became an important name in electrophysiology science (30, 31). Centuries later, scientists still studied the effect of the electric field in living organisms, namely, Patel and Poo (32) analysed the reaction of Xenopus neurons after applying a 1–10 V cm−1 steady state electric field. They observed that the cells changed the direction of neurite growth with the direction of the electric field and that the neurites had enhanced growth in the cathode direction. Their results indicated that the electric field not only had a biological effect, as noticed by Galvani but also could promote cell growth and organisation and could alter molecule migration in the neuronal membrane surface.

Moreover, the muscles and the neurosystems are not the only types of cells that can suffer an electric field effect. Fukada and Yasuda (33) and Anderson and Eriksson (34) investigated the piezoelectric properties of bone cells, pointing out that piezoelectricity enabled the use of an electric field in these cells. Valentini et al. (35) used polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), a piezoelectric polymer, to enhance neurite outgrowth of Nb2a cells with charged polymers, indicating that the materials could also assist ES.

From this perspective, Wong et al. (36) showed that PPy could be used as a biomaterial for cell culture of aortic endothelial cells, and they also noticed that the polymer charge affected the cell shape, indicating that the charge on the surface could regulate cell growth but did not affect the cell viability.

A very recent study by da Silva et al. (37) presented a study concerning the effect of ES on protein and cell adhesion over a copolymer of PEDOT and poly(d,l-lactic acid) (PEDOT-co-PDLLA) film. They investigated the effect of a + 0.5 V and a −0.125 V ES in a film of the copolymer over a gold quartz electrode, monitoring the adsorption of fibronectin and the adhesion of NIH-3T3 with an electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation (QCM-D). They noticed that ES increased fibronectin adsorption on the PEDOT-co-PDLLA surface and that the stimuli also promoted an improvement of fibroblast adhesion over the film and increased cell proliferation.

Previous reviews have focused on the effect of ES on cell behaviour and closely examined the cell response regarding viability, morphology, and gene expression. In this study, we attempt to summarise these interactions mediated mainly by CPs, and we look more closely at the material synthesis, properties, and electrochemical setup (38–63).

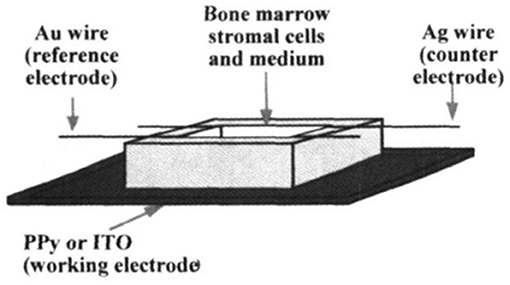

Shastri et al. (64) presented an ES study using PPy as a conductive substrate able to generate a response in the differentiation of bovine bone marrow stroma cells (BMSCs). They chose this CP for this cell type based on a study by Yasuda (33) investigating the piezoelectric behaviour of bone tissue. The electrode is based on electropolymerised PPy over an indium tin oxide (ITO) substrate. For BMSC growth, they used osteogenic supplements, ascorbic acid, dexamethasone, and β-glycerophosphate to enhance the capability of osteogenic differentiation. The ES setup is based on the use of a PPy electrode as the anode, a gold wire acting as a cathode, and the quasi-reference electrode as the silver wire (Figure 1). The authors applied a steady field of 20 V m−1 for 1 h, showing cell viability over the PPy substrate similar to the control (tissue culture polystyrene, TCPS) and better than that on the ITO without the PPy film. The analysis of alkaline phosphate (ALP) activity (an important marker to indicate osteogenic differentiation) showed that cells cultured over the PPy film resulted in higher levels of ALP activity, which was enhanced after ES only on the PPy film. Therefore, these results were presented as an effect of the surface chemistry of PPy films, with the negatively charged surface being important for the adhesion of positively charged proteins of cells, such as fibronectin, which acts in favour of cell adhesion and osteogenic differentiation.

Figure 1. Scheme for Electrical stimulation (ES) of BMSC on polypyrrole (PPy) thin films. Reproduced from (64) with the permission of the Materials Research Society.

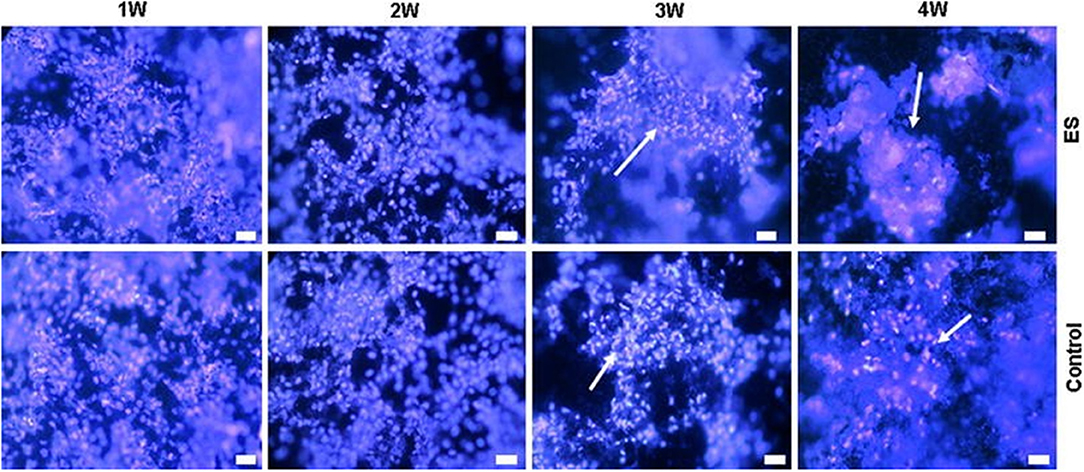

Another study related to the ES of bone cells was published by Meng et al. (65). In that study, the authors used osteoblast-like Saos-2 cells, which are important for the regeneration of bone tissue, and a PPy/polylactide (PLLA)/heparin (HE) composite was synthesised via chemical polymerisation. The reaction yielded a solution that was cast onto a Teflon plate forming a membrane. Cell culture and growth were expected to yield bone nodule mineralisation and to form inorganic elements, mainly calcium and phosphate. These minerals are present in hydroxyapatite, the main structural mineral in bone composition. After incubation in a standard medium for 2 days, the cells were cultured for 24 h in wells in the same standard medium, which was replaced with a mineralisation medium, and 200 V mm−1 ES was applied for three periods of 6 h for 6 days. The cultures were then left to grow for 3 more weeks without any ES. The control group and the experimental group showed divergences on week 3, when more cell aggregates appeared in the experimental wells than in the control wells. From weeks 3–4, significant growth was observed in the amount of those cell aggregates in the experimental wells (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Electrical stimulation study on Saos-2 cells on PLLA/PPy/HE membranes. The arrowheads show the formation of nodules in the highest periods (Hoechst staining, bar 10 μm). Adapted from (65) with permission from the publisher.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of mineralisation showed that in both the experimental and control groups, mineral particles appeared in the 1st week and grew over the course of the 4 weeks, as well as osteoblast nodules and aggregations. It is important to highlight that the number and size of mineral particles and the osteoblast nodules/aggregations were much larger in the experimental cultures than in the control cultures. The crystal structure of the mineral obtained by wide-angle x-ray diffraction (WAXD) was remarkably similar to those obtained from natural hydroxyapatite. This finding indicates that the crystallisation process of the experiment resembles the natural process. Moreover, there was a clear augmentation of calcium and phosphate levels when ES was applied.

In a more recent study, Hardy et al. (66) reported a method for creating silk foam-based bone tissue scaffolds, which allows the stimulation of human mesenchymal stem cells (HMSCs) to intensify their osteogenic differentiation. Natural silk proteins and recombinant silk-inspired proteins are well-known base materials for use in tissue scaffold engineering (67–71). The scaffolds were interpenetrated with a self-doped CP composed of pyrrole and 2-hydroxy-5-sulphonic aniline, and polymerisation within the scaffold was performed in situ using ammonium persulphate and ferric chloride. The enhanced scaffolds allowed direct ES of the HMSCs residing within them and improved the osteogenic differentiation outcome, which was confirmed by both biochemical assays and qualitative histological analysis. ES also increased the calcium and collagen concentrations, which are important for the formation of the calcified extracellular matrix associated with bone.

In another study with PPy, Richardson et al. (72) presented gold electrodes covered with polypyrrole-p-toluene sulphonic acid (PPy:pTS) with an incorporation of neurotrophin-3 (NT3) on its surface and applied ES to release the incorporated NT3 into a spiral ganglion neuron (SGN) culture. PPy was electrochemically polymerised over a gold electrode, and p-toluene sulphonate (tosylate) was added as the dopant. During the polymerisation process, NT3 was added to the electrochemical cell. For the ES experiments, cells had grown over the electrodes for 24 h, and biphasic current pulses were applied for 1 h (± 1 mA current amplitude, at 250 Hz). After ES, the cells were cultured for 3 days before further analysis. The authors verified that polyornithine, a cell adhesion molecule, improved cell growth when coated over electrodes, and they also showed that boosting the NT3 concentration improved neurite outgrowth. They verified the improvement in cell growth when neurites were cultured close to the electrodes and suggested that the effect of NT3 release combined with ES could explain this behaviour. The systems with ES showed an enhancement of neurite outgrowth in comparison with the one without ES when PPy/pTS/NT3 was used, but when the PPy/pTS electrode was used, ES had no influence. This finding indicated that the release of NT3 had a more important effect on cell growth than ES.

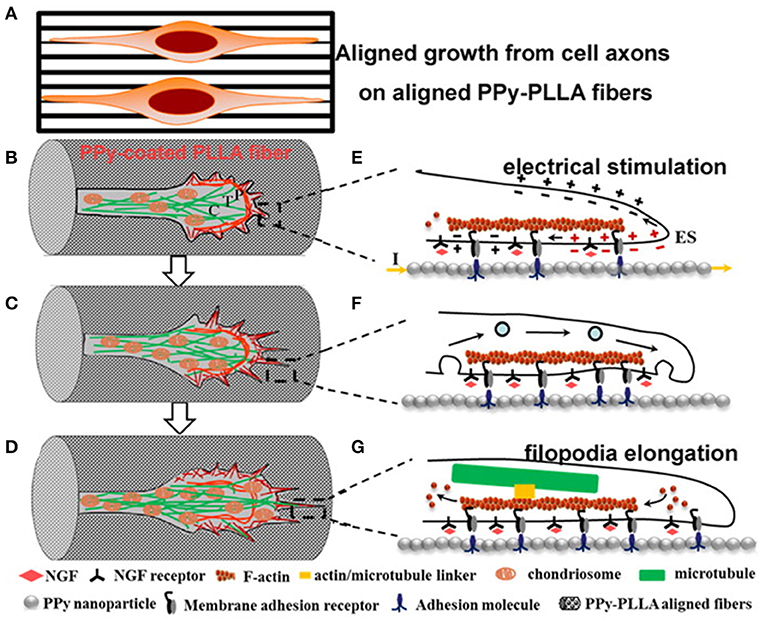

In 2009, Xie et al. (73) presented the preparation of a PPy-based core-shear nanofibre for studies on axon regeneration, aiming to use the material for neural tissue engineering. The material consisted of electrospun fibres made of poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) or poly(L-lactide) (PLA) and pyrrole using Fe3+ and Cl− as an oxidant and as a dopant, respectively. They noticed that the PPy coating over PCL and PLA presented different morphologies. The material electroactivity was studied by applying a 10-V constant potential for 4 h per day over the random and aligned materials. They calculated the effective current applied as ~250 μA (74, 75). ES produced better results in increasing length when using random nanofibres than with aligned nanofibres, which could be related to the cell growth capability reaching a length limit. The authors analysed the ES effect on cell growth, explaining that the electrical current changed the interaction of the adhesive glycoproteins with the charged PPy chain, improving the adhesion of cells and resulting in a higher growth rate (76). Other possibilities were the change in the electrophoretic distribution resulting in polarisation of the cells, improvement in the rate of protein synthesis, favourable protein conformation, migration of Schwann cells, and formation of an induced field in the cell culture with a molecular and ionic gradient (24).

In another study with PPy, Yan et al. (77) proposed the fabrication of an implant that can be electrically stimulated as a way to treat retinal ganglial cells (RGCs) lesioned by glaucoma disease. For this purpose, the use of a mixed material made of graphene oxide (GO) modified with PPy (PPy-G) is proposed prior to preparing a nanofibrous scaffold by electrospinning a mixture of PPy-G with polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA). The electrochemical characterisation led the authors to choose an approach with double-pulsed potential chronoamperometry varying the potential from 0.1 to 1 V cm−1, and the reverse potential varied from −0.1 to −1 V cm−1 for 1 h day−1 for 3 days. The variation of potential was important to establish the best conditions of ES for these cells over the material; and it was observed that at ±1,000 mV cm−1, death of RGCs was caused by overpolarisation, so a ±700 mV cm−1 step potential was chosen. Applying this ES, the cell length increased compared with that in the non-stimulated group, with a major increase observed in the 6% PPy-G scaffold, which was the most electroactive material.

The authors also verified the ageing of the RGC cultures over the 6% PPy-G material with and without ES. The main viability of this cell type after 10 days was 40%, showing nuclear necrosis and cell apoptosis in the control group. Over the conductive scaffold, the cells without ES presented cell shape alterations, such as a reduction of the round shape, indicating an apoptotic process; however, when the cells were cultured over the scaffold and electrically stimulated, they displayed an increase in cell length, and the morphology was maintained. The authors suggested that ES on the material also promoted an anti-ageing effect on RGCs.

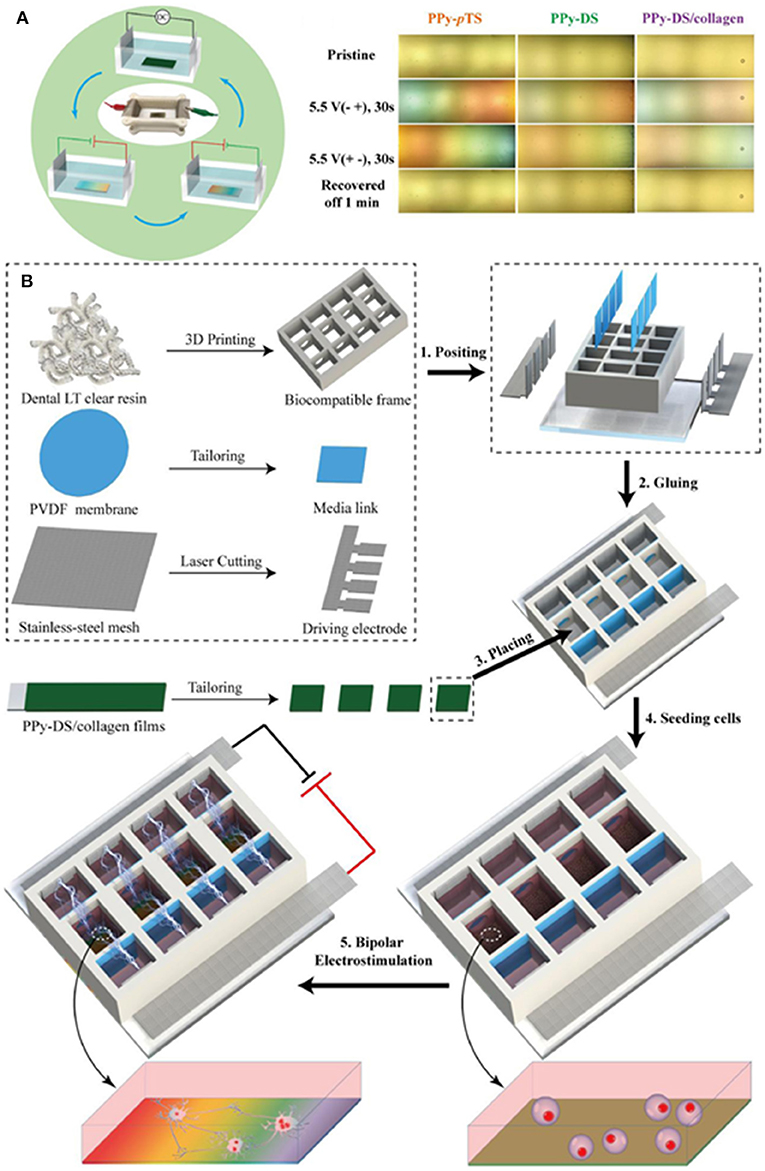

A novel approach for applying ES is when the electrode materials are not connected directly to the power supply, but a dipole is created wirelessly between them and the electrodes are connected to the culture medium in which they are immersed. Qin et al. (78) showed that bipolar electrochemistry could offer this effective pathway to modify ES systems into a more desirable contactless mode (Figure 3A). In that study, they presented for the first time the development of a CP-based bipolar electrical stimulation (BPES) system for living cells. PPy films with different dopants were used to demonstrate a reversible and recoverable bipolar electrochemical activity under a low driving DC voltage (<-5.5 V). A BPES prototype enabling wireless and programmable cell stimulation was devised using PPy codoped with dextran sulphate (DS) and collagen (PPy-DS/collagen) as a bipolar electrode and rat pheochromocytoma cells as a model cell line (Figure 3B). Significantly, wireless stimulation enhanced cell proliferation and differentiation. This study established a new paradigm for ES of living cells using CPs as bipolar electrodes, providing an attractive wireless approach to advance the field of medical bionics.

Figure 3. (A) Scheme of BPES cycling and CP-immersed bipolar cells. (B) Manufacture of BPES platform. Adapted from (78) with permission from the publisher.

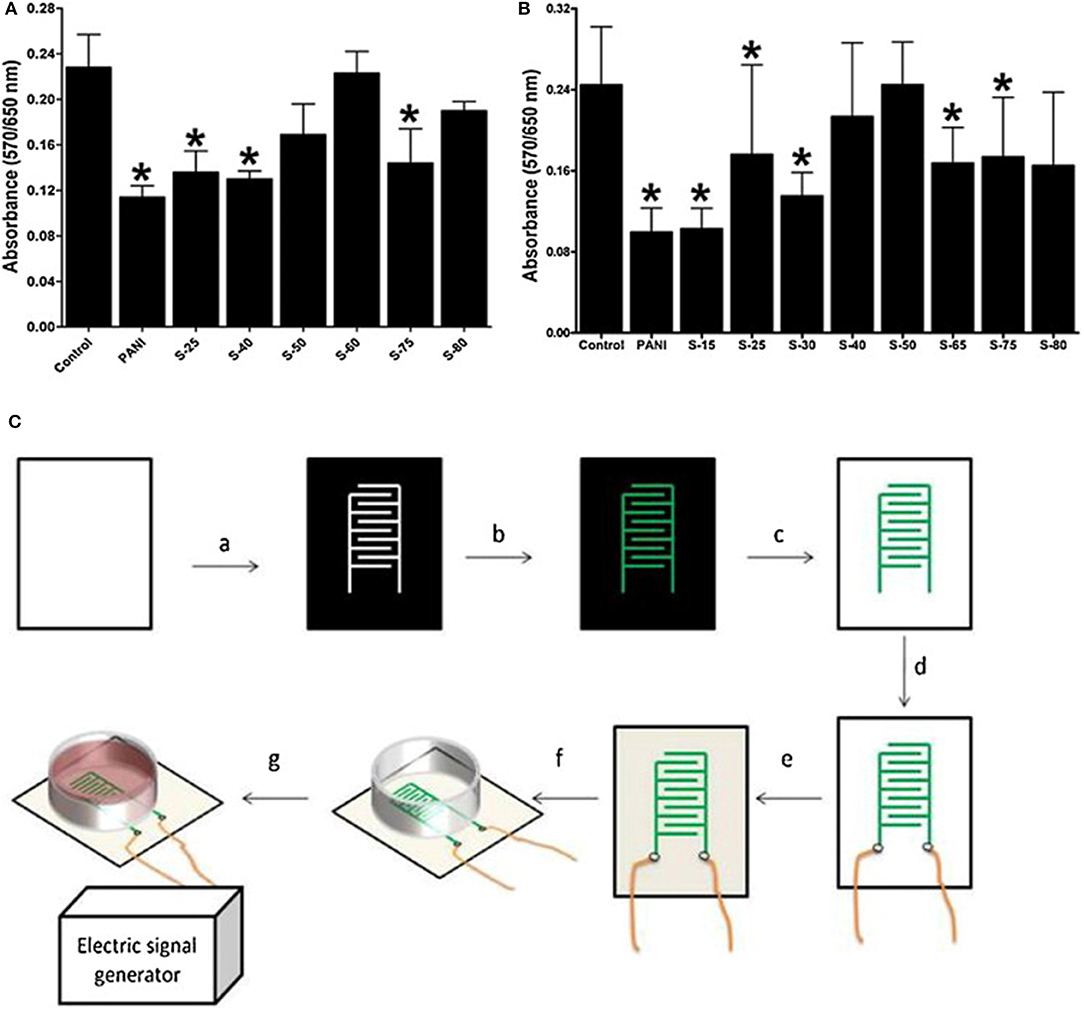

Materials based on PANI have also been extensively applied in combination with ES for in vitro studies. Min et al. (79) reported a facile fabrication method of self-doped sulphonated polyaniline (SPAN)-based interdigitated electrodes (IDEs) for controlled ES of cancer-type human osteosarcoma (HOS) cells. An increased degree of sulphonation was found to increase the SPAN conductivity, which in turn improved cell attachment and cell growth without ES. However, enhanced cell growth was observed under controlled ES with alternating current at a low applied voltage and frequency (≤800 mV and ≤1 kHz). Cell growth reached a maximum threshold at an applied voltage or frequency, beyond which pronounced cell death was observed. The ES was initially performed with a sine wave generator at a fixed frequency of 1 kHz. The cells were subjected to a steady potential between 0 and 1,600 mV. ES applied through SPAN-based IDEs was found to significantly enhance cell growth, as shown in Figure 4. Furthermore, the growth of the cells increased with the potential and showed no abnormal cellular behaviour or cell death up to 1,000 mV. However, when the applied potential was increased to above 1,200 mV, cell death was more pronounced. A rapid increase in cell growth was observed at a very low applied frequency (≤1 kHz), and it remained constant up to 100 kHz. Nevertheless, significantly enhanced cell death was observed above 200 kHz. The ALP activity profile was similar to the cell proliferation profile, which further confirmed the above results.

Figure 4. SPAN biocompatibility with (A). BMSCs and (B). MC3T3-E1 cells, without electrical stimulation, after 5 days (C). Fabrication of SPAN-based IDEs: (a) Printing on a PET transparency, (b) layer-by-layer deposition by in situ polymerization, (c) toner removal, (d) wire connexion with silver glue, (e) PLA coating, (f) electrode assembly, and (g) power connexion. Adapted from (105) with permission from the publisher. *represents a statistically significant difference in comparison with the control; (1-way RM-ANOVA and Newman–Keuls post-hoc analysis with p < 0.05, n = 6).

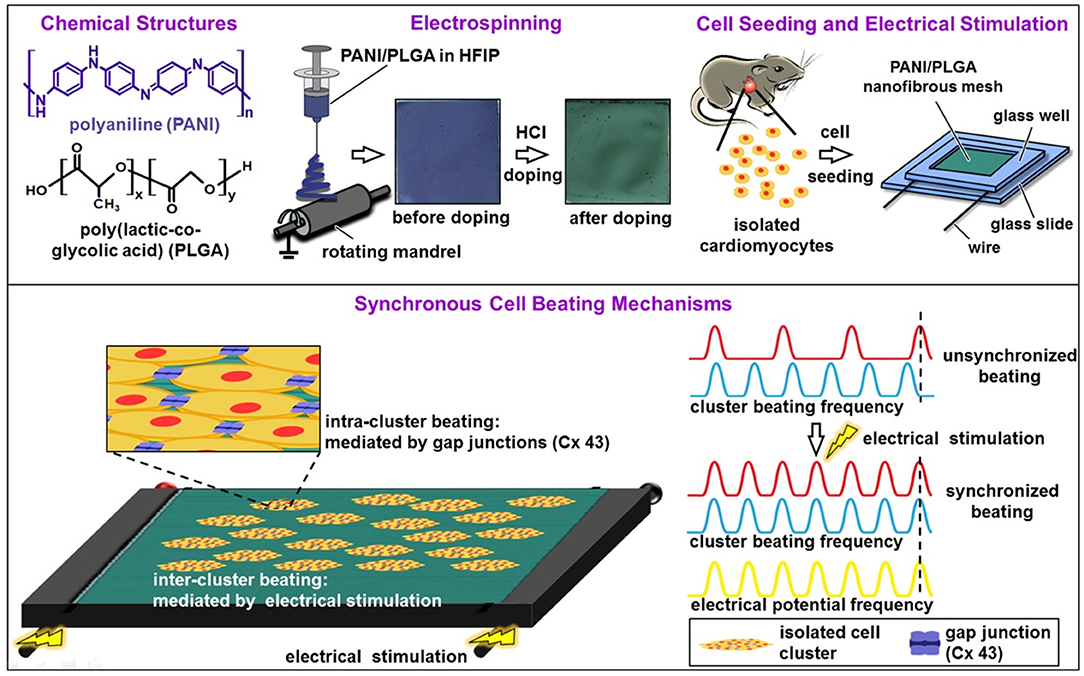

The study of Hsiao et al. (80) presented the synthesis of a nanofibre mesh of PLGA and PANI for ES of cardiomyocytes. The fibres were synthesised using 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) as the solvent (capable of solubilizing PANI-EB and PLGA), and the mixture was used to produce fibres by electrospinning. As soon as the meshes were prepared, CP was doped with HCl, changing its oxidation state from PANI-EB to PANI-ES by overnight protonation with a visible change in colour, as shown in Figure 5. The fibre alignment was analysed as a function of different proportions of PANI and PLGA, indicating that it was enhanced by increasing the amount of PLGA. It was also observed that PANI maintained conductivity in cell culture media for 100 h, after which the conductivity started to decrease because of PANI deprotonation. Culture of cardiomyocytes over the material before and after doping was positively affected by the alignment of the cells with the meshes in the doped state. ES was performed as shown in Figure 5, where 5 V cm−1, 1.25 Hz electrical pulses were applied (81), raising the possibility of coordinating cardiomyocyte contraction between distant cell clusters.

Figure 5. Diagrams showing the fabrication of aligned conductive PANI/PLGA nanofibrous mesh, cell seeding, ES, and the mechanisms involved in the synchronous cell beatings. Adapted from (80) with permission from the publisher.

Transplantation of neural stem cells (NSCs) is an important tool for the recovery of injured tissue, as these cells have the ability to differentiate into neurons and other key components of the central nervous system (CNS). To avoid the random differentiation of NSCs, ES coupled with CPs as scaffold materials for cell growth had the ability to promote nerve regeneration without eliciting apoptosis due to a lack of control of exogenous factor release or high current stimulation. Xu et al. (82) developed a platform for the differentiation of NSCs based on a hydrogel (PVV-PANI) consisting of poly(2-vinyl-4,6-diamino-1,3,5-triazine) (PVDT) and 1-vinylimidazole (VI) crosslinked with poly(ethylene glycol diacrylate) coated with PANI, which was responsive to ES. The conductivity of PVV-PANI hydrogels increased by up to 5-fold when compared with PVDT without VI, indicating that the imidazole groups acted as dopants and facilitated the adsorption of PANI, which increased the electrical conductivity. The hydrogel also showed robust and elastic mechanical properties, making it a promising material for tissue engineering. The setup for cell stimulation was based on two PANI-coated ITO electrodes serving as substrates after removing the cell growth factors from the culture medium. NSCs grew for 24 h before applying a 200 Hz electric field with charge balance every other 6 h from 1 to 7 days with a biphasic pulse amplitude of 75 mV. Starting on day 5, there was a significant difference in the density of cells cultured under ES when compared with those without stimuli. A higher potential was observed to adversely affect cell growth, and the best results were obtained at 15 mV.

The effect of ES on NSC differentiation was also observed. Cells under ES showed more and longer neurites as well as more surface coverage compared with unstimulated cells. The length of the neurites also varied proportionally to the applied potential. Gene expression experiments corroborated the results, with higher values of β3-tubulin, B-FABP, and PMP22 obtained for stimulated cells, as well as genes involved in preferential differentiation to neurons and glial cells, while the value for nestin, a specific marker for NSCs, was higher in the unstimulated group.

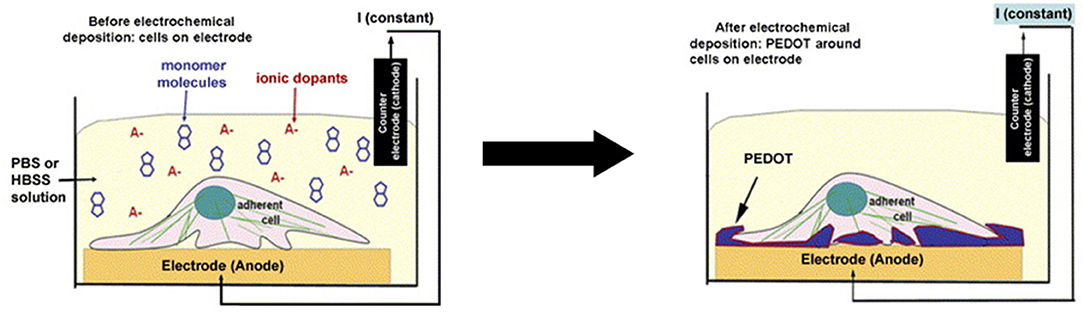

Another interesting study regarding material fabrication by Richardson-Burns et al. (83) studied the effects of depositing PEDOT around living neural cells. The authors studied the way the cells themselves responded to the coating and the electrochemical characteristics of the electrodes. Two different neural cell types were used: MCC and SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma-derived cell lines. Initially, cytotoxicity tests were performed with the cells using the monomer of the polymer EDOT and the stabiliser PSS−. The experiments showed that the cells could withstand concentrations of as high as 0.01 M EDOT and 0.02% PSS− for as long as 72 h. The method of preparation of the PEDOT-coated neural cells was as follows: first, the cells were cultured over the surface of the electrodes for 24–48 h; then, the electrodes were submerged in a solution of EDOT:PSS− for the subsequent electrochemical process of polymerisation. The scheme is shown below (Figure 6). This process resulted in the deposition of the polymer around the living cells. There were regions where the deposition was not present, which probably represented contact points of the cells and the electrodes where no monomer could be polymerised. This technique was subsequently implemented in the creation of cell-templated electrodes, thus creating cell-shaped cavities on their surfaces. This phenomenon was achieved by the decellularisation of the previously produced electrodes. Tests were then performed to evaluate the preference of cells in adhering to the surface. The cells seemed to have a preference for regions in which cells were present before decellularisation. However, few cells would still grow in the regions without apparent templating. PEDOT-coated cells were studied for abnormalities and defects, and despite signs of apoptosis, most of the cells were healthy after polymerisation. Apoptosis rates indeed increased, but only at 72 h after polymerisation. This finding showed that the procedure had no significant effect on nutrient transport to the cells. Increased rates of apoptosis could be attributed to subsequent permeabilisation of the cellular membrane after the electrochemical process, which was discovered by staining the cells with propidium iodide, a nucleic acid dye that is impermeable to cells with intact plasma membranes. Abnormal F-actin staining was also observable in the cells coated with PEDOT as early as 1 h after the experiment.

Figure 6. Scheme of PEDOT electrochemical deposition around the neural cell monolayer on the electrode surface. Adapted from (83) with permission from the publisher.

The study of Bolin et al. (84) presented nanofibres consisting of poly(ethyleneterphthalate) (PET) covered with PEDOT doped with tosylate. The material was used for ES of SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. PET nanofibres were generated by electrospinning and covered with PEDOT by vapour phase polymerisation (VPP) of its monomer. The authors called the ES an electrochemical switch of PEDOT, for which they developed a setup that applies 3 V cm−1, enabling the electrochromic effect of PEDOT. At −3 V, they noticed Ca2+ release, and when the ES ended, Ca2+dropped to baseline. When the stimuli were repeated, the Ca2+ release was slower, and the authors correlated with voltage-operated Ca2+ channel desensitisation. To depolarise the membrane, KCl (50 mM) was added between the stimuli. The Ca2+ increase induced by the nanofibres was less steep than that induced by KCl, which could have been due to the conducting electrochemical properties of PEDOT, suggesting that the nanofibres were well-suited as electrodes for ES in vitro.

Another study based on PEDOT was carried out by Krukiewicz et al. (85), who studied Pt electrodes with fractal-like forms based on PEDOT/Au film for enhancing the length of neurites using mesencephalon cells. The electrode was formed by stacking layers of PEDOT:PSS (spin-coating) and Au (sputtering) over a Pt-coated glass plate, with the first layer being PEDOT:PSS and the last layer being Au. They noticed that the improvement of the layers produced electrodes with a fractal-like organisation and greater Au particles, varying from 91 nm (one layer of Au) to 702 nm (seven PEDOT/Au layers) in diameter. They discussed that the presence of water related to PEDOT:PSS creates the conditions for the gold nanoparticles to reorganise toward agglomerates and form fractal structures. The study presented different types of electrochemical characterisation, indicating that the material had a low electrical impedance of 30 ± 2 Ω at 1 Hz, charge storage capacity of 34.9 ± 2.6 mC cm−2, and good electrochemical stability. Other factors, such as a high signal-to-noise ratio, are important for neuronal application in ES studies.

In a more recent study, Tsai et al. (86) developed a composite electrode based on an electrospinning process with poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO), (3-glycidyloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane (GOPS) and PEDOT:PSS (87). This material showed high water resistance and retained good electrochemical performance during ES; moreover, the electrospun nanofibres possessed an efficient attraction surface, which allowed neuron adhesion and manipulation of the cell morphology. Interestingly, a spin-coated film from the same dispersion formed a contact repulsion surface that limited cell attachment. The authors suspected that this behaviour could derive from the superior nanoscale architecture in the nanofibrous material, which resembled extracellular matrixes.

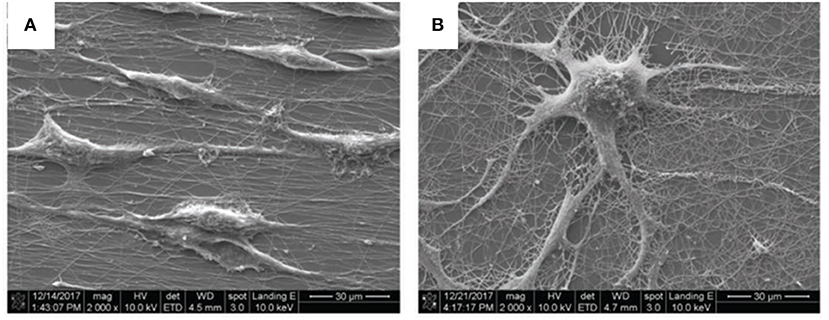

In that study, the PEO/PEDOT:PSS composite was used in the form of a thin film, with aligned or random nanofibres as a surface for differentiation of the pheochromocytoma 12 (PC12) cell line into neuron-like cells under ES. This approach is known to promote neurite growth by enhancing the MEK-ERK1/2 protein pathway (88) and by regulating protein kinase C (PKC) activity (89). The results of neurite outgrowth without ES showed that random nanofibres (Figure 7) allowed the formation of more neurites than aligned nanofibres or thin films, which showed the worst results.

Figure 7. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of (A) aligned and (B) random nanofibres after 5 days of culturing without ES; scale bar: 30 μm. Reproduced from Tsai et al. with permission from Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA.

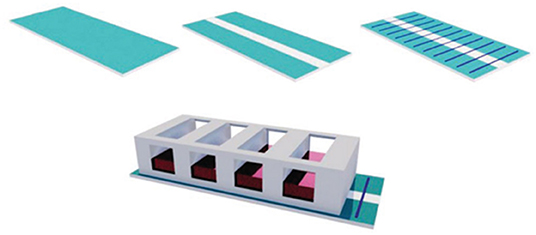

Figure 8 shows an ES device that was mounted with PEO/PEDOT:PSS nanofibres electrospun on the surface of an ITO electrode and a chamber slide to prevent cross-contamination. PC12 cells were seeded, and after 1 day, a differentiation medium was added to ensure cell adhesion. An electrical field was provided and maintained for 5 days at an amplitude of 100 mV cm−1 for 1 h per day with a biphasic pulse (duration of 100 ms; interval of 100 ms).

Figure 8. Electrical stimulation device setup with ITO substrate; ITO substrate with an etching gap; aligned nanofibers electrospun on the modified ITO substrate; aligned nanofibers electrospun on the modified ITO substrate inside a chamber slide. Reproduced from (86) with permission from Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA.

The neurite length was increased onto the aligned nanofibres compared with the control plate surface (TCPS) and the random fibres, with the latter presenting the lowest values. The ES time was also directly proportional to the neurite length regarding both the pulse period and days of exposure. When examining gene expression, the authors observed that ES was effective in increasing the formation of RNA primers related to neural-like cells, and that longer pulses induced later stages of neural differentiation.

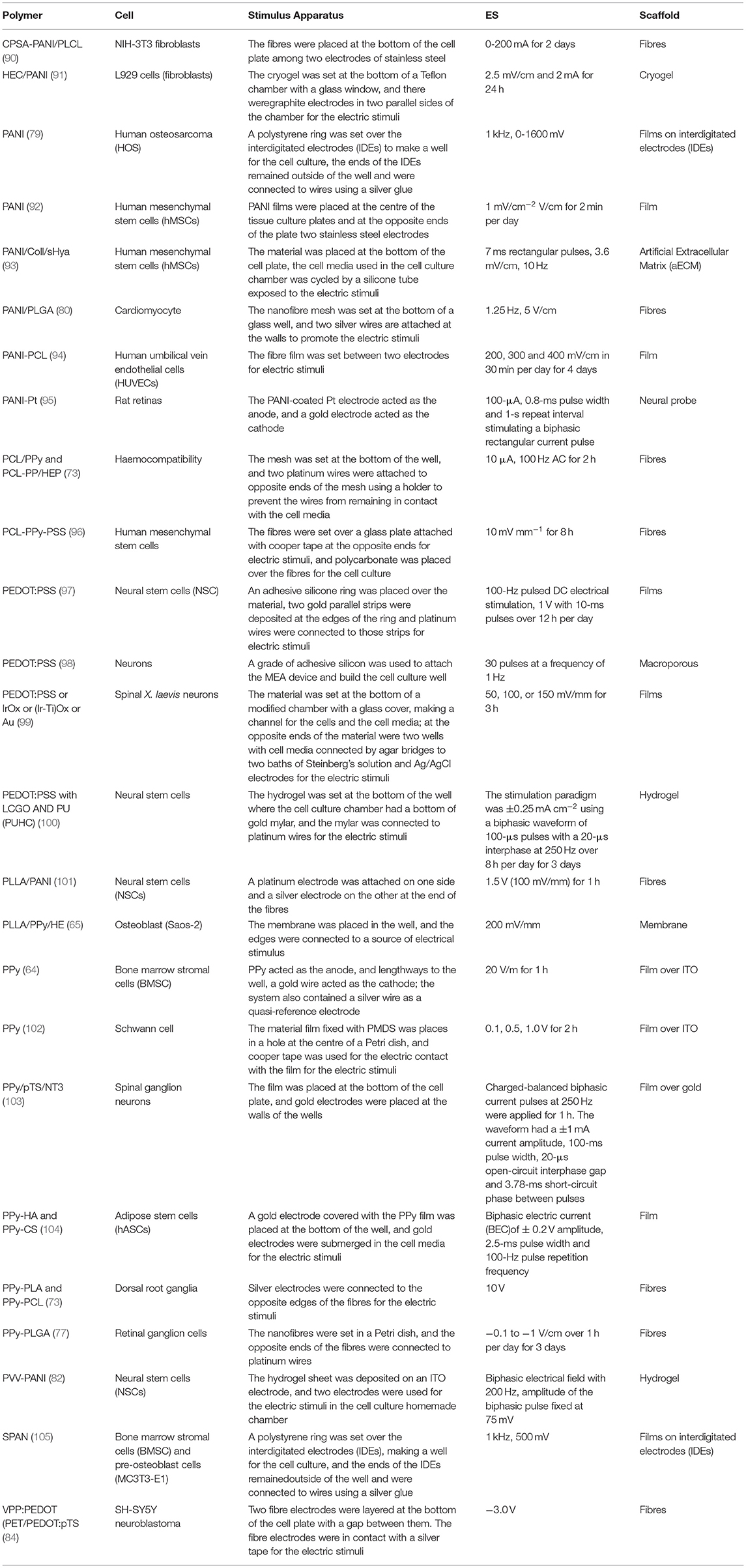

A compilation of the conditions used in different studies with ES, CPs and cells is systematised in Table 2.

Table 2. Electrical stimulation (ES) studies on different cell lines applied to conductive polymeric materials.

To compare different setups with CPs and ES, we decided to look at studies with PC12 cells, and their conditions are summarised in Table 3. Within these studies, Zou et al. (114) prepared a material of PPy-PDLLA and applied electric fields of 100, 200, 400, and 800 mV cm−1 to PC12 cells for 4 h. The material was made by electrospinning, and they could control fibre formation, making films of both random and aligned fibres. They noticed that the material organisation without ES was able to orient the cells, and this orientation also increased the neurite length from 65 μm in the random fibre film to 114 μm on average for the aligned fibres. When an electric field was applied, the effect on cells over the aligned fibres was enhanced, especially at an applied potential of 200 mV cm−1. ES also promoted an enhancement of cell differentiation and cell alignment over the fibres.

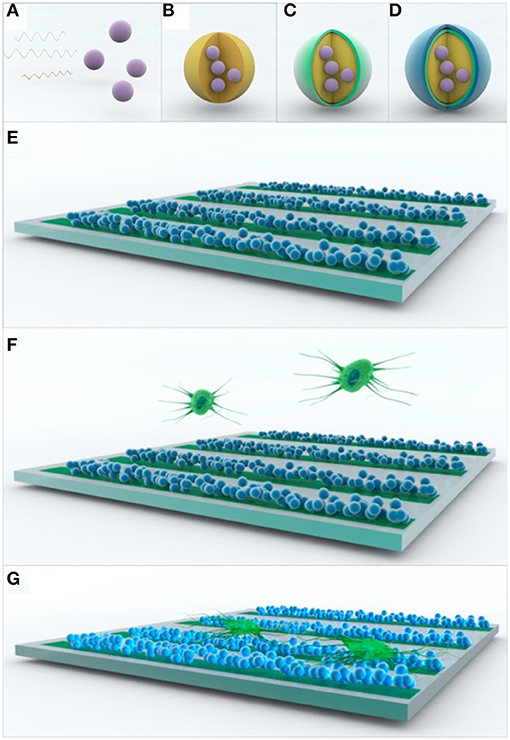

Ho et al. (108) also noticed that a patterned scaffold based on PEDOT:PSS nanoparticles structured in a conduit pattern over an ITO substrate could enhance the adhesion of PC12 cells (Figure 9). By applying pulses at 250 Hz for 2 ms with an amplitude of 1 mA, it was noticed that the cells improved the dendritic network over the aligned fibre scaffold.

Figure 9. Scheme of the assembly of multifunctional PEDOT:PSS nanoparticle arrays for ES. (A–D) Multilayer formation of PEDOT:PSS nanoparticles via non-spontaneous emulsification. (E–G) Patterning of the multilayered PEDOT:PSS nanoparticles for ES of PC12 cells. Reproduced from (108) with permission from the publisher.

These studies showed that the alignment of the fibres in the scaffold influenced cellular growth, and, therefore, on the device setup for the ES experiments, the fibres were connected in a manner to allow the flux of electrons to follow the fibres in the material.

To understand the effect of an organised pattern, Zou et al. (114) proposed a mechanism that correlates the CP surface during ES with the neural growth cone, and they showed that the enhancement of charge in a rough PPy-PDLLA fibre surface could trigger processes of molecule adhesion and neural growth cones in different domains (peripheral, P, transition zone, T, and central domain, C), creating guidance for neuron outgrowth along the PPy-PDLLA fibres (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Scheme of axon elongation from PC12 cells on aligned fibres (A) after differentiation, (B–D) change in growth cone, and (E–G) inner change in filopodia during elongation. Reproduced from (114) with permission from the publisher.

Together with the material scaffold, ES conditions are also important to modulate cell growth and differentiation. Moroder et al. (107) proposed a study on two different ES routines over polycaprolactone fumarate–PPy (PCLF–PPy) scaffolds to stimulate PC12 cells. The setups promoted 10 μA current stimuli over the membranes, one with a constant direct current applied for 1 h per day for 2 days, and the other with a pulse frequency of 20 Hz. They noticed that the membrane of PCFL-PPy treated with naphthalene sulphonic acid (NSA) and with an ES of 20 Hz frequency resulted in an increase in the neurite number per cell in comparison to the constant one, but both ES protocols promoted enhancement of the neurite length per cell over the non-stimulated culture. Taking that study into account, the choice of ES conditions needs to be tested with the cells and the material so that the difference in material conductivity can change the current density felt by the cells and hinder the current density measurement given that the geometric areas of fibres or membranes do not represent the total area of the material (116).

In summary, for PC12 cells, an ES of at least 10 mV over a time range of 2–5 h in total was sufficient to promote cell outgrowth (24, 110, 111, 113–115, 117), This finding indicates that a continuous stimulus for a defined period per day can promote cell growth without damaging the cells or the electrode.

When comparing studies related to neurons, Rajnicek et al. (98) studied the effects of an applied electric field over amphibian neurons growing on transparent films of diverse conductive materials, such as bare metals, polymers, and semiconducting oxides. The applied electric field was not direct; hence, it was applied by connecting electrodes to the solution in which the materials were immersed, generating a dipole wirelessly within them. The electric field was from a DC power supply connected to two Ag/AgCl electrodes in baths of Steinberg's solution. Electrical contact with the cell cultures was made through two 2%w/v agar bridges, with one end of each bridge in the electrode bath and the other in the pools of culture medium at each end of the channel. The medium was constrained by dams of silicone. The electric field was set by measuring the voltage across the chamber length to yield 50, 100, or 150 mV mm−1.

To date, studies conducted on mammalian cells have been limited and have generally focused on hippocampal neurons in the CNS in the absence of glia. Embryonic rat hippocampal neurons were submitted to constant DC fields of 28–219 mV mm−1 for 24 h and responded by extending the outgrowth perpendicular to the applied ES with less growth in the cathode direction (118). A higher non-physiological applied ES (>580 mV mm−1) caused embryonic rat hippocampal neuronal growth cones to turn in the direction of the cathode (119). A recent study also showed that ES increased the survival rates of retinal ganglion cells after the optical nerve had been damaged (120).

The topography and chemistry of the growth substrate also influence the ES neuronal response. As an example, neurites extending from embryonic frog spinal neurons showed not only electrical cues but also guidance cues, and the neurites extended orthogonally to the applied electrical field (121).

These findings explain how many factors play key roles in in vitro ES studies. As an example, astrocytes are the most abundant glia in the CNS and have various functions, such as in the nutrient supply, neurotransmission, and structural support. They are known to orient themselves perpendicular to a highly exogenous non-physiological electrical field (122). This behaviour is instructive for neurons, and when controlled by an exogenous stimulus, they can provide benefits of assisting in neuronal injury repair. Another example is oligodendrocytes, which are an important myelinating agent in CNS glia. Experiments have shown that controlled applied electrical fields exhibited higher rates of neuronal survival than control fields (123). These experiments clearly showed that glia of the CNS responded differently following ES. The mechanisms to explain such responses need to be further investigated until an improved understanding is achieved.

A major concern when applying in vitro ES of CP-based materials is the effect on water electrolysis and consequently on the medium pH, which can affect cell viability (51, 88). Cell culture with ES can also promote electrode corrosion (42), and, thus, some studies have combined biodegradable materials with CPs to avoid generating toxic species in the media (124–126). Biphasic stimuli represent a process that changes the current direction during pulses, a procedure that is interesting for reducing electrode damage by Faradaic reactions at the electrode surface (42, 44).

Moreover, it is important to maintain the current density within a range without causing cell damage, and the current density is dependent not only on the ES but also on material conductivity, number of cells, and distance between the electrodes (127). Changing these parameters could change the current density through the cells. Hence, the material properties together with ES generate responses in the molecules of the cell membrane, leading to accelerated growth and differentiation processes, which is a beneficial and key aspect of tissue regeneration.

In vitro ES using CPs needs to consider the design of the material as well as the type of cell in relation to the stimulus control. In the case of different cells, the ES duration may vary: for cardiomyocytes, it is interesting to apply a short-period stimulus to monitor contraction of the cells during stimulation, while for neuronal cells, longer ES periods are necessary to monitor the cells after each stimulus to confirm the cell viability. Biphasic stimulation is also an important and viable alternative to reduce cell and electrode damage during long ES periods. The addition of growth factors to the cell media or when immobilised on the CP surface could also affect the necessary ES duration.

Electrical stimulation can be performed in various devices, some of which make use of the CP itself as a working electrode, allowing the stimulus to be applied directly on the material or as thin films deposited on conductive supports, such as ITO and gold mylar. Other possible designs make use of a salt bridge that generates a flux of electrons in the culture medium. Overall, the choice of devices in vitro must acknowledge that the material should generate a cell stimulus without eliciting any toxic effects. Another important aspect to consider is to construct the device with the material synthesis already envisioning the in vivo application.

In summary, CPs and ES are important tools to study cell growth for in vitro tissue regeneration and are relevant to understanding and tailoring future applications of these materials in in vivo devices.

All the authors contributed to the writing and discussion of the study.

FAPESP scholarships: 2020/15005-1, 2018/11162-5, and 2018/21546-5. FAPESP projects: 2018/13492-2 and 2015/26308-7. CNPq scholarship: 133326/2018-7.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors would like to thank FAPESP and CNPq for the funding.

1. Shirakawa H, Louis EJ, MacDiarmid AG, Chiang CK, Heeger AJ. Synthesis of electrically conducting organic polymers: Halogen derivatives of polyacetylene, (CH)x. J Chem Soc Chem Commun. (1977) 578–80. doi: 10.1039/c39770000578

2. Mayer AC, Scully SR, Hardin BE, Rowell MW, McGehee MD. Polymer-based solar cells. Mater Today. (2007) 10:28–33. doi: 10.1016/S1369-7021(07)70276-6

3. Svirskis D, Travas-Sejdic J, Rodgers A, Garg S. Electrochemically controlled drug delivery based on intrinsically conducting polymers. J Control Rel. (2010) 146:6–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.03.023

4. Mortimer RJ, Dyer AL, Reynolds JR. Electrochromic organic and polymeric materials for display applications. Displays. (2006) 27:2–18. doi: 10.1016/j.displa.2005.03.003

5. Castagnola E, Ansaldo A, Maggiolini E, Angotzi GN, Skrap M, Ricci D, et al. Biologically compatible neural interface to safely couple nanocoated electrodes to the surface of the brain. ACS Nano. (2013) 7:3887–95. doi: 10.1021/nn305164c

6. Mathiyarasu J, Senthilkumar S, Phani KLN, Yegnaraman V. PEDOT-Au nanocomposite film for electrochemical sensing. Mater Lett. (2008) 62:571–3. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2007.06.004

7. Łapkowski M, Proń A. Electrochemical oxidation of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) - “in situ” conductivity and spectroscopic investigations. Synthetic Metals. (2000) 110:79–83. doi: 10.1016/S0379-6779(99)00271-4

8. Pereira Da Silva JE, Córdoba de Torresi SI, Torresi RM. Polyaniline acrylic coatings for corrosion inhibition: the role played by counter-ions. Corrosion Sci. (2005) 47:811–22. doi: 10.1016/j.corsci.2004.07.014

9. Zarras P, Anderson N, Webber C, Irvin DJ, Irvin JA, Guenthner A, et al. Progress in using conductive polymers as corrosion-inhibiting coatings. Radiat Phys Chem. (2003) 68:387–94. doi: 10.1016/S0969-806X(03)00189-0

10. Bredas JL, Street GB. Polarons, bipolarons, and solitons in conducting polymers. Acc Chem Res. (1985) 18:309–15. doi: 10.1021/ar00118a005

11. Carlberg C, Chen X, Inganäs O. Ionic transport and electronic structure in poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene). Solid State Ionics. (1996) 85:73–8. doi: 10.1016/0167-2738(96)00043-4

12. Groenendaal L, Zotti G, Aubert PH, Waybright SM, Reynolds JR. Electrochemistry of poly(3,4-alkylenedioxythiophene) derivatives. Adv Mater. (2003) 15:855–79. doi: 10.1002/adma.200300376

13. MacDiarmid AG, Epstein AJ. The concept of secondary doping as applied to polyaniline. Synth Met. (1994) 65:103–16. doi: 10.1016/0379-6779(94)90171-6

14. Cen L, Neoh KG, Kang ET. Surface functionalization of electrically conductive polypyrrole film with hyaluronic acid. Langmuir. (2002) 18:8633–40. doi: 10.1021/la025979b

15. Asplund M, Thaning E, Lundberg J, Sandberg-Nordqvist AC, Kostyszyn B, Inganäs O, et al. Toxicity evaluation of PEDOT/biomolecular composites intended for neural communication electrodes. Biomed Mater. (2009) 4:045009. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/4/4/045009

16. Asplund M, von Holst H, Inganäs O. Composite biomolecule/PEDOT materials for neural electrodes. Biointerphases. (2008) 3:83–93. doi: 10.1116/1.2998407

17. Kim DH, Wiler JA, Anderson DJ, Kipke DR, Martin DC. Conducting polymers on hydrogel-coated neural electrode provide sensitive neural recordings in auditory cortex. Acta Biomater. (2010) 6:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.07.034

18. Lu B, Yuk H, Lin S, Jian N, Qu K, Xu J, et al. Pure PEDOT:PSS hydrogels. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09003-5

19. Yuk H, Lu B, Lin S, Qu K, Xu J, Luo J, et al. 3D printing of conducting polymers. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:4–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15316-7

20. Scrosati B. Polymer electrodes. In: Bruce PG, editor. Solid State Electrochemistry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1994). p. 229–63. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511524790.010

21. Furukawa Y, Tazawa S, Fujii Y, Harada I. Raman spectra of polypyrrole and its 2,5-13C-substituted and C-deuterated analogues in doped and undoped states. Synth Met. (1988) 24:329–41. doi: 10.1016/0379-6779(88)90309-8

22. Liu YC, Hwang BJ, Jian WJ, Santhanam R. In situ cyclic voltammetry-surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy: studies on the doping-undoping of polypyrrole film. Thin Solid Films. (2000) 374:85–91. doi: 10.1016/S0040-6090(00)01061-0

23. Garner B, Georgevich A, Hodgson AJ, Liu L, Wallace GG. Polypyrrole-heparin composites as stimulus-responsive substrates for endothelial cell growth. J Biomed Mater Res. (1999) 44:121–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4636(199902)44:2<121::AID-JBM1>3.0.CO;2-A

24. Schmidt CE, Shastri VR, Vacanti JP, Langer R. Stimulation of neurite outgrowth using an electrically conducting polymer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1997) 94:8948–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.8948

25. MacDiarmid AG. “Synthetic metals”: a novel role for organic polymers. Angew Chem Int Ed. (2001) 40:2581–90. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010716)40:14<2581::AID-ANIE2581>3.0.CO;2-2

26. Alemán C, Teixeira-Dias B, Zanuy D, Estrany F, Armelin E, del Valle LJ. A comprehensive study of the interactions between DNA and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene). Polymer. (2009) 50:1965–74. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2009.02.033

27. Stossel TP. On the crawling of animal cells. Science. (1993) 260:1086–94. doi: 10.1126/science.8493552

28. Cho MR, Thatte HS, Lee RC, Golan DE. Reorganization of microfilament structure induced by ac electric fields. FASEB J. (1996) 10:1552–8. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.13.8940302

29. Cho MR, Thatte HS, Lee RC, Golan DE. Integrin-dependent human macrophage migration induced by oscillatory electrical stimulation. Ann Biomed Eng. (2000) 28:234–43. doi: 10.1114/1.263

30. Piccolino M. Luigi Galvani and animal electricity: two centuries after the foundation of electrophysiology. Trends Neurosci. (1997) 20:443–8. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(97)01101-6

31. McCaig CD, Rajnicek AM, Song B, Zhao M. Controlling cell behavior electrically: current views and future potential. Physiol Rev. (2005) 85:943–78. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2004

32. Patel N, Poo MM. Orientation of neurite growth by extracellular electric fields. J Neurosci. (1982) 2:483–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-04-00483.1982

33. Fukada E, Yasuda I. On the piezoelectric effect of silk fibers. J Phys Soc Jap. (1957) 12:1158–62. doi: 10.1143/JPSJ.12.1158

34. Anderson JC, Eriksson C. Piezoelectric properties of dry and wet bone. Nature. (1970) 227:491–2. doi: 10.1038/227491a0

35. Valentini RF, Vargo TG, Gardella JA, Aebischer P. Electrically charged polymeric substrates enhance nerve fibre outgrowth in vitro. Biomaterials. (1992) 13:183–90. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(92)90069-Z

36. Wong JY, Langer R, Ingber DE. Electrically conducting polymers can noninvasively control the shape and growth of mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1994) 91:3201–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3201

37. da Silva AC, da Silva RA, Souza MJPG, Montoya PM, Bentini R, Augusto T, et al. Electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance with dissipation investigation of fibronectin adsorption dynamics driven by electrical stimulation onto a conducting and partially biodegradable copolymer. Biointerphases. (2020) 15:021003. doi: 10.1116/1.5144983

38. Arteshi Y, Aghanejad A, Davaran S, Omidi Y. Biocompatible and electroconductive polyaniline-based biomaterials for electrical stimulation. Eur Polym J. (2018) 108:150–70. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2018.08.036

39. Sensharma P, Madhumathi G, Jayant RD, Jaiswal AK. Biomaterials and cells for neural tissue engineering: current choices. Mater Sci Eng C. (2017) 77:1302–15. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.03.264

40. Ning C, Zhou Z, Tan G, Zhu Y, Mao C. Electroactive polymers for tissue regeneration: developments and perspectives. Prog Polym Sci. (2018) 81:144–62. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2018.01.001

41. Stoppel WL, Kaplan DL, Black LD III. Electrical and mechanical stimulation of cardiac cells and tissue constructs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. (2016) 96:135–55. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.07.009

42. Bertucci C, Koppes R, Dumont C, Koppes A. Neural responses to electrical stimulation in 2D and 3D in vitro environments. Brain Res Bull. (2019) 152:265–84. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2019.07.016

43. Dong R, Ma PX, Guo B. Conductive biomaterials for muscle tissue engineering. Biomaterials. (2020) 229:119584. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119584

44. Thrivikraman G, Boda SK, Basu B. Unraveling the mechanistic effects of electric field stimulation towards directing stem cell fate and function: a tissue engineering perspective. Biomaterials. (2018) 150:60–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.10.003

45. Ding J, Zhang J, Li J, Li D, Xiao C, Xiao H, et al. Electrospun polymer biomaterials. Prog Polym Sci. (2019) 90:1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2019.01.002

46. Vandghanooni S, Eskandani M. Electrically conductive biomaterials based on natural polysaccharides: challenges and applications in tissue engineering. Int J Biol Macromol. (2019) 141:636–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.09.020

47. Fomby P, Cherlin AJ, Hadjizadeh A, Doillon CJ, Sueblinvong V, Weiss DJ, et al. Stem cells and cell therapies in lung biology and diseases: conference report. Ann Am Thorac Soc. (2010) 12:181–204. doi: 10.1002/term.383

48. Hardy JG, Lee JY, Schmidt CE. Biomimetic conducting polymer-based tissue scaffolds. Curr Opin Biotechnol. (2013) 24:847–54. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.03.011

49. Nezakati T, Seifalian A, Tan A, Seifalian AM. Conductive polymers: opportunities and challenges in biomedical applications. Chem Rev. (2018) 118:6766–843. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00275

50. Balint R, Cassidy NJ, Cartmell SH. Conductive polymers: towards a smart biomaterial for tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. (2014) 10:2341–53. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.02.015

51. Merrill DR, Bikson M, Jefferys JGR. Electrical stimulation of excitable tissue: design of efficacious and safe protocols. J Neurosci Methods. (2005) 141:171–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.10.020

52. Aregueta-Robles UA, Woolley AJ, Poole-Warren LA, Lovell NH, Green RA. Organic electrode coatings for next-generation neural interfaces. Front Neuroeng. (2014) 7:1–18. doi: 10.3389/fneng.2014.00015

53. Municoy S, Álvarez Echazú MI, Antezana PE, Galdopórpora JM, Olivetti C, Mebert AM, et al. Stimuli-responsive materials for tissue engineering and drug delivery. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:1–39. doi: 10.3390/ijms21134724

54. Levin M, Stevenson CG. Regulation of cell behavior and tissue patterning by bioelectrical signals: challenges and opportunities for biomedical engineering. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. (2012) 14:295–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071811-150114

55. Ateh DD, Navsaria HA, Vadgama P. Polypyrrole-based conducting polymers and interactions with biological tissues. J Royal Soc Interface. (2006) 3:741–52. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0141

56. Qazi TH, Rai R, Boccaccini AR. Tissue engineering of electrically responsive tissues using polyaniline based polymers: a review. Biomaterials. (2014) 35:9068–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.020

57. Ali I, Xudong L, Xiaoqing C, Zhiwei J, Pervaiz M, Weimin Y, et al. A review of electro-stimulated gels and their applications: present state and future perspectives. Mater Sci Eng C. (2019) 103:109852. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.109852

58. Zhou DD, Cui XT, Hines A, Greenberg RJ. Conducting Polymers in Neural Stimulation Applications. Sylmar, CA: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC (2010). doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-98120-8_8

59. Zhu R, Sun Z, Li C, Ramakrishna S, Chiu K, He L. Electrical stimulation affects neural stem cell fate and function in vitro. Exp Neurol. (2019) 319:112963. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2019.112963

60. Chen YS. Effects of electrical stimulation on peripheral nerve regeneration. BioMedicine. (2011) 1:33–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biomed.2011.10.006

61. Metwally S, Stachewicz U. Surface potential and charges impact on cell responses on biomaterials interfaces for medical applications. Mater Sci Eng C. (2019) 104:109883. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.109883

62. Hosoyama K, Ahumada M, Goel K, Ruel M, Suuronen EJ, Alarcon EI. Electroconductive materials as biomimetic platforms for tissue regeneration. Biotechnol Adv. (2019) 37:444–58. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2019.02.011

63. da Silva AC, Córdoba de Torresi SI. Advances in conducting, biodegradable and biocompatible copolymers for biomedical applications. Front Mater. (2019) 6:1–9. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2019.00098

64. Shastri VP, Rahman N, Martin I, Langer R. Application of conductive polymers in bone regeneration. Mater Res Soc Symp Proc. (1999) 550:215–9. doi: 10.1557/PROC-550-215

65. Meng S, Zhang Z, Rouabhia M. Accelerated osteoblast mineralization on a conductive substrate by multiple electrical stimulation. J Bone Miner Metab. (2011) 29:535–44. doi: 10.1007/s00774-010-0257-1

66. Hardy JG, Geissler SA, Aguilar D, Villancio-Wolter MK, Mouser DJ, Sukhavasi RC, et al. Instructive conductive 3D silk foam-based bone tissue scaffolds enable electrical stimulation of stem cells for enhanced osteogenic differentiation. Macromol Biosci. (2015) 15:1490–6. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201500171

67. Hardy JG, Pfaff A, Leal-Egaña A, Müller AHE, Scheibel TR. Glycopolymer functionalization of engineered spider silk protein-based materials for improved cell adhesion. Macromol Biosci. (2014) 14:936–42. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201400020

68. Saha S, Kundu B, Kirkham J, Wood D, Kundu SC, Yang XB. Osteochondral tissue engineering in vivo: a comparative study using layered silk fibroin scaffolds from mulberry and nonmulberry silkworms. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e80004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080004

69. Widhe M, Johansson J, Hedhammar M, Rising A. Invited review: current progress and limitations of spider silk for biomedical applications. Biopolymers. (2012) 97:468–78. doi: 10.1002/bip.21715

70. Dal Pra I, Freddi G, Minic J, Chiarini A, Armato U. De novo engineering of reticular connective tissue in vivo by silk fibroin nonwoven materials. Biomaterials. (2005) 26:1987–99. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.036

71. Zhao Z, Li Y, Xie MB. Silk fibroin-based nanoparticles for drug delivery. Int J Mol Sci. (2015) 16:4880–903. doi: 10.3390/ijms16034880

72. Richardson RT, Thompson B, Moulton S, Newbold C, Lum MG, Cameron A, et al. The effect of polypyrrole with incorporated neurotrophin-3 on the promotion of neurite outgrowth from auditory neurons. Biomaterials. (2007) 28:513–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.008

73. Xie J, Macewan MR, Willerth SM, Li X, Moran DW, Sakiyama-Elbert SE, et al. Conductive core–sheath nanofibers and theirpotential application in neural tissue engineering. Adv Funct Mater. (2009) 19:2312–8. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200801904

74. Kerns JM, Fakhouri AJ, Weinrib HP, Freeman JA. Electrical stimulation of nerve regeneration in the rat: the early effects evaluated by a vibrating probe and electron microscopy. Neuroscience. (1991) 40:93–107. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90177-P

75. Kow LM, Pfaff DW. Estrogen effects on neuronal responsiveness to electrical and neurotransmitter stimulation: an in vitro study on the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus. Brain Res. (1985) 347:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90883-2

76. Kotwal A, Schmidt CE. Electrical stimulation alters protein adsorption and nerve cell interactions with electrically conducting biomaterials. Biomaterials. (2001) 22:1055–64. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(00)00344-6

77. Yan L, Zhao B, Liu X, Li X, Zeng C, Shi H, et al. Aligned nanofibers from polypyrrole/graphene as electrodes for regeneration of optic nerve via electrical stimulation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. (2016) 8:6834–40. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b12843

78. Qin C, Yue Z, Chao Y, Forster RJ, Maolmhuaidh FÓ, Huang X-F, et al. Bipolar electroactive conducting polymers for wireless cell stimulation. Appl Mater Today. (2020) 21:100804. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2020.100804

79. Min Y, Yang Y, Poojari Y, Liu Y, Wu JC, Hansford DJ, et al. Sulfonated polyaniline-based organic electrodes for controlled electrical stimulation of human osteosarcoma cells. Biomacromolecules. (2013) 14:1727–31. doi: 10.1021/bm301221t

80. Hsiao CW, Bai MY, Chang Y, Chung MF, Lee TY, Wu CT, et al. Electrical coupling of isolated cardiomyocyte clusters grown on aligned conductive nanofibrous meshes for their synchronized beating. Biomaterials. (2013) 34:1063–72. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.10.065

81. Yamauchi Y, Harada A, Kawahara K. Changes in the fluctuation of interbeat intervals in spontaneously beating cultured cardiac myocytes: experimental and modeling studies. Biol Cybern. (2002) 86:147–54. doi: 10.1007/s00422-001-0285-y

82. Xu B, Bai T, Sinclair A, Wang W, Wu Q, Gao F, et al. Directed neural stem cell differentiation on polyaniline-coated high strength hydrogels. Mater Today Chem. (2016) 1–2:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mtchem.2016.10.002

83. Richardson-Burns SM, Hendricks JL, Foster B, Povlich LK, Kim DH, Martin DC. Polymerization of the conducting polymer poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) around living neural cells. Biomaterials. (2007) 28:1539–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.026

84. Bolin MH, Svennersten K, Wang X, Chronakis IS, Richter-Dahlfors A, Jager EWH, et al. Nano-fiber scaffold electrodes based on PEDOT for cell stimulation. Sens Actuat B Chem. (2009) 142:451–6. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2009.04.062

85. Krukiewicz K, Chudy M, Vallejo-Giraldo C, Skorupa M, Wiecławska D, Turczyn R, et al. Fractal form PEDOT/Au assemblies as thin-film neural interface materials. Biomed Mater. (2018) 13:054102. doi: 10.1088/1748-605X/aabced

86. Tsai NC, She JW, Wu JG, Chen P, Hsiao YS, Yu J. Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polymer composite bioelectrodes with designed chemical and topographical cues to manipulate the behavior of PC12 neuronal cells. Adv Mater Interfaces. (2019) 6:1–11. doi: 10.1002/admi.201801576

87. Yu CC, Ho BC, Juang RS, Hsiao YS, Naidu RVR, Kuo CW, et al. Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-based nanofiber mats as an organic bioelectronic platform for programming multiple capture/release cycles of circulating tumor cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. (2017) 9:30329–42. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b07042

88. Pires F, Ferreira Q, Rodrigues CAV, Morgado J, Ferreira FC. Neural stem cell differentiation by electrical stimulation using a cross-linked PEDOT substrate: expanding the use of biocompatible conjugated conductive polymers for neural tissue engineering. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2015) 1850:1158–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2015.01.020

89. Brosenitsch TA, Katz DM. Physiological patterns of electrical stimulation can induce neuronal gene expression by activating N-type calcium channels. J Neurosci. (2001) 21:2571–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02571.2001

90. Jeong SI, Jun ID, Choi MJ, Nho YC, Lee YM, Shin H. Development of electroactive and elastic nanofibers that contain polyaniline and poly(L-lactide-co-ε-caprolactone) for the control of cell adhesion. Macromol Biosci. (2008) 8:627–37. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200800005

91. Petrov P, Mokreva P, Kostov I, Uzunova V, Tzoneva R. Novel electrically conducting 2-hydroxyethylcellulose/polyaniline nanocomposite cryogels: synthesis and application in tissue engineering. Carbohydr Polym. (2016) 140:349–55. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.12.069

92. Thrivikraman G, Madras G, Basu B. Intermittent electrical stimuli for guidance of human mesenchymal stem cell lineage commitment towards neural-like cells on electroconductive substrates. Biomaterials. (2014) 35:6219–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.018

93. Thrivikraman G, Lee PS, Hess R, Haenchen V, Basu B, Scharnweber D. Interplay of substrate conductivity, cellular microenvironment, and pulsatile electrical stimulation toward osteogenesis of human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. (2015) 7:23015–28. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b06390

94. Li Y, Li X, Zhao R, Wang C, Qiu F, Sun B, et al. Enhanced adhesion and proliferation of human umbilical vein endothelial cells on conductive PANI-PCL fiber scaffold by electrical stimulation. Mater Sci Eng C. (2017) 72:106–12. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.11.052

95. Di L, Wang LP, Lu YN, He L, Lin ZX, Wu KJ, et al. Protein adsorption and peroxidation of rat retinas under stimulation of a neural probe coated with polyaniline. Acta Biomater. (2011) 7:3738–45. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.06.009

96. Xiong GM, Yuan S, Wang JK, Do AT, Tan NS, Yeo KS, et al. Imparting electroactivity to polycaprolactone fibers with heparin-doped polypyrrole: modulation of hemocompatibility and inflammatory responses. Acta Biomater. (2015) 23:240–9. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.05.003

97. Wang S, Guan S, Li W, Ge D, Xu J, Sun C, et al. 3D culture of neural stem cells within conductive PEDOT layer-assembled chitosan/gelatin scaffolds for neural tissue engineering. Mater Sci Eng C. (2018) 93:890–901. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.08.054

98. Rajnicek AM, Zhao Z, Moral-Vico J, Cruz AM, McCaig CD, Casañ-Pastor N. Controlling nerve growth with an electric field induced indirectly in transparent conductive substrate materials. Adv Healthc Mater. (2018) 7:1–11. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201800473

99. McCaig CD. Spinal neurite reabsorption and regrowth in vitro depend on the polarity of an applied electric field. Development. (1987) 100:31–41. doi: 10.1242/dev.100.1.31

100. Javadi M, Gu Q, Naficy S, Farajikhah S, Crook JM, Wallace GG, et al. Conductive Tough Hydrogel for Bioapplications. Macromol Biosci. (2018) 18:1–11. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201700270

101. Prabhakaran MP, Ghasemi-Mobarakeh L, Jin G, Ramakrishna S. Electrospun conducting polymer nanofibers and electrical stimulation of nerve stem cells. J Biosci Bioeng. (2011) 112:501–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.07.010

102. Forciniti L, Ybarra J, Zaman MH, Schmidt CE. Schwann cell response on polypyrrole substrates upon electrical stimulation. Acta Biomater. (2014) 10:2423–33. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.01.030

103. Evans AJ, Thompson BC, Wallace GG, Millard R, O'Leary SJ, Clark GM, et al. Promoting neurite outgrowth from spiral ganglion neuron explants using polypyrrole/BDNF-coated electrodes. J Biomed Mater Res A. (2009) 91:241–50. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32228

104. Björninen M, Siljander A, Pelto J, Hyttinen J, Kellomäki M, Miettinen S, et al. Comparison of chondroitin sulfate and hyaluronic acid doped conductive polypyrrole films for adipose stem cells. Ann Biomed Eng. (2014) 42:1889–900. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1023-7

105. Min Y, Liu Y, Poojari Y, Wu JC, Hildreth BE, Rosol TJ, et al. Self-doped polyaniline-based interdigitated electrodes for electrical stimulation of osteoblast cell lines. Synth Met. (2014) 198:308–13. doi: 10.1016/j.synthmet.2014.10.035

106. Wang L, Huang Q, Wang JY. Nanostructured polyaniline coating on ITO glass promotes the neurite outgrowth of PC 12 cells by electrical stimulation. Langmuir. (2015) 31:12315–22. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b00992

107. Moroder P, Runge MB, Wang H, Ruesink T, Lu L, Spinner RJ, et al. Material properties and electrical stimulation regimens of polycaprolactone fumarate-polypyrrole scaffolds as potential conductive nerve conduits. Acta Biomater. (2011) 7:944–53. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.10.013

108. Ho D, Zou J, Chen X, Munshi A, Smith NM, Agarwal V, et al. Hierarchical patterning of multifunctional conducting polymer nanoparticles as a bionic platform for topographic contact guidance. ACS Nano. (2015) 9:1767–74. doi: 10.1021/nn506607x

109. Huang L, Zhuang X, Hu J, Lang L, Zhang P, Wang Y, et al. Synthesis of biodegradable and electroactive multiblock polylactide and aniline pentamer copolymer for tissue engineering applications. Biomacromolecules. (2008) 9:850–8. doi: 10.1021/bm7011828

110. Xu H, Holzwarth JM, Yan Y, Xu P, Zheng H, Yin Y, et al. Conductive PPY/PDLLA conduit for peripheral nerve regeneration. Biomaterials. (2014) 35:225–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.002

111. Lee JY, Bashur CA, Goldstein AS, Schmidt CE. Polypyrrole-coated electrospun PLGA nanofibers for neural tissue applications. Biomaterials. (2009) 30:4325–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.042

112. Liu X, Yue Z, Higgins MJ, Wallace GG. Conducting polymers with immobilised fibrillar collagen for enhanced neural interfacing. Biomaterials. (2011) 32:7309–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.047

113. Gomez N, Schmidt CE. Nerve growth factor-immobilized polypyrrole: bioactive electrically conducting polymer for enhanced neurite extension. J Biomed Mater Res A. (2006) 79:135–49. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31047

114. Zou Y, Qin J, Huang Z, Yin G, Pu X, He D. Fabrication of aligned conducting PPy-PLLA fiber films and their electrically controlled guidance and orientation for neurites. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. (2016) 8:12576–82. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b00957

115. Zhang J, Qiu K, Sun B, Fang J, Zhang K, Ei-Hamshary H, et al. The aligned core-sheath nanofibers with electrical conductivity for neural tissue engineering. J Mater Chem B. (2014) 2:7945–54. doi: 10.1039/C4TB01185F

116. Voiry D, Chhowalla M, Gogotsi Y, Kotov NA, Li Y, Penner RM, et al. Best practices for reporting electrocatalytic performance of nanomaterials. ACS Nano. (2018) 12:9635–8. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b07700

117. Kim S, Jang LK, Jang M, Lee S, Hardy JG, Lee JY. Electrically conductive polydopamine-polypyrrole as high performance biomaterials for cell stimulation in vitro and electrical signal recording in vivo. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. (2018) 10:33032–42. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b11546

118. Rajnicek A, Gow N, McCaig C. Electric field-induced orientation of rat hippocampal neurones in vitro. Exp Physiol. (1992) 77:229–32. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1992.sp003580

119. Davenport RW, McCaig CD. Hippocampal growth cone responses to focally applied electric fields. J Neurobiol. (1993) 24:89–100. doi: 10.1002/neu.480240108

120. Henrich-Noack P, Voigt N, Prilloff S, Fedorov A, Sabel BA. Transcorneal electrical stimulation alters morphology and survival of retinal ganglion cells after optic nerve damage. Neurosci Lett. (2013) 543:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.03.013

121. McCaig CD. Electric fields, contact guidance and the direction of nerve growth. J Embryol Exp Morphol. (1986) 94:245–55. doi: 10.1242/dev.94.1.245

122. Borgens RB, Shi R, Mohr TJ, Jaeger CB. Mammalian cortical astrocytes align themselves in a physiological voltage gradient. Exp Neurol. (1994) 128:41–9. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1111

123. Gary DS, Malone M, Capestany P, Houdayer T, Mcdonald JW. Electrical stimulation promotes the survival of oligodendrocytes in mixed cortical cultures. J Neurosci Res. (2012) 90:72–83. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22717

124. Quigley AF, Razal JM, Thompson BC, Moulton SE, Kita M, Kennedy EL, et al. A conducting-polymer platform with biodegradable fibers for stimulation and guidance of axonal growth. Advanced Materials. (2009) 21:4393–7. doi: 10.1002/adma.200901165

125. Shi G, Rouabhia M, Wang Z, Dao LH, Zhang Z. A novel electrically conductive and biodegradable composite made of polypyrrole nanoparticles and polylactide. Biomaterials. (2004) 25:2477–88. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.032

126. Silva AC, Semeano ATS, Dourado AHB, Ulrich H, Torresi SIC. Novel conducting and biodegradable copolymers with noncytotoxic properties toward embryonic stem cells. ACS Omega. (2018) 3:5593–604. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b,00510

Keywords: electrical stimulation, conductive polymers, biomaterials, cell culture, cells-material interactions

Citation: Rocha I, Cerqueira G, Varella Penteado F and Córdoba de Torresi SI (2021) Electrical Stimulation and Conductive Polymers as a Powerful Toolbox for Tailoring Cell Behaviour in vitro. Front. Med. Technol. 3:670274. doi: 10.3389/fmedt.2021.670274

Received: 20 February 2021; Accepted: 17 June 2021;

Published: 29 July 2021.

Edited by:

Rami Mhanna, American University of Beirut, LebanonReviewed by:

Firouzeh Sabri, University of Memphis, United StatesCopyright © 2021 Rocha, Cerqueira, Varella Penteado and Córdoba de Torresi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Igor Rocha, aWdvci5yb2NoYUB1c3AuYnI=; Susana I. Córdoba de Torresi, c3RvcnJlc2lAaXEudXNwLmJy

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.