- 1Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 2Department of Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 3Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 4Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, The Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, Baltimore, MD, United States

- 5Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

Introduction: Healthcare workers’ well-being is of utmost importance given persistent high rates of burnout, which also affects quality of care. Minority healthcare workers (MHCW) face unique challenges including structural racism and discrimination. There is limited data on interventions addressing the psychological well-being of MHCW. Thus, this systematic review aims to identify interventions specifically designed to support MHCW well-being, and to compare measures of well-being between minority and non-minority healthcare workers.

Methods: We searched multiple electronic databases. Two independent reviewers conducted literature screening and extraction. The Mixed Methods Assessment Tool (MMAT) or Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) criteria were utilized to assess the methodological quality of studies, based on the study design. Total scores as percentages of criteria met were used to determine overall quality as low (<40%), moderate (40-80%), or high (>80%). For conflicts, consensus was reached through discussion. Meta-analysis was not possible due to heterogeneity of study designs.

Results: A total of 3,816 records were screened and 43 were included in the review. The majority of included studies (76.7%) were of moderate quality. There were no randomized control trials and only one study included a well-being intervention designed specifically for MHCW. Most (67.4%) were quantitative-descriptive studies that compared well-being measures between minority and non-minority identifying healthcare workers. Common themes identified were burnout, job retention, job satisfaction, discrimination, and diversity. There were conflicting results regarding burnout rates in MHCW vs non-minority workers with some studies citing protective resilience and lower burnout while others reported greater burnout due to compounding systemic factors.

Discussion: Our findings illuminate a lack of MHCW-specific well-being programs. The conflicting findings of MHCW well-being do not eliminate the need for supports among this population. Given the distinct experiences of MHCW, the development of policies surrounding diversity and inclusion, mental health services, and cultural competency should be considered. Understanding the barriers faced by MHCW can improve both well-being among the healthcare workforce and patient care.

Introduction

Healthcare worker (HCW) well-being is of great public health importance as high rates of burnout are present throughout the medical field and are linked to poor patient care outcomes (1). Burnout can be defined as unsuccessfully managed chronic workplace stress that results in emotional exhaustion, job dissatisfaction, and reduced professional efficacy (2). Systemic factors such as workload, organizational structure, and access to support systems contribute to stress and burnout rates. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, well-being has taken center stage due to concerning levels of psychosocial strain throughout the healthcare workforce. A study by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported significantly higher burnout rates among health workers in 2022 (46%) compared to 2018 (32%) (3). In the global context, a report by the Qatar Foundation, World Innovation Summit for Health (WISH), in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO) found similar findings of healthcare worker burnout ranging from 41 to 52% (4). Other measures such as the number of poor mental health days, intent to change jobs, and harassment showed similar trends before and after the pandemic (3).

The negative impact on quality and costs of care associated with poor HCW well-being is also of significant concern (1). HCWs suffering from burnout may struggle to concentrate and be less detail-oriented, and more likely to make mistakes that can affect patient care and increase medical expenditures (5). Multiple studies have demonstrated a relationship between the onset of physician burnout and declining patient safety (6, 7). A systematic review by Hall et al. found that “poor [well-being] and moderate to high levels of burnout [were] associated, in the majority of studies reviewed, with poor patient safety outcomes.” (6) Increases in the frequency of hospital-acquired infections (8), mortality risk, and length of hospital stay have all been found to be associated with nurse burnout (9). A cost–benefit analysis of an institution-wide support program for nursing staff projected an estimated $1.81 million in annual hospital cost savings after implementation of the well-being intervention (10). Given these concerning findings, it is imperative to address well-being among HCWs.

Minority healthcare workers (MHCW), such as those self-identifying with racial/ethnic, sexual and gender, or migrant minority groups, face unique challenges that may affect their workplace associated well-being. In addition to traditional workplace pressures, MHCW may need to navigate systemic barriers such as structural racism, discrimination, and stereotyping. Further, they are more likely to work in underserved communities with limited resources (11). These circumstances may compound one another and contribute to differences in well-being compared to their non-minority counterparts. Although it is crucial to acknowledge the unique circumstances of this population, there is inconclusive evidence that MHCW experience worse well-being. Previous studies present conflicting evidence on burnout rates between minority and non-minority HCWs with some even suggesting that a minority background can be a protective factor (12).

There is limited data on interventions targeting the well-being of MHCW. Most well-being interventions are designed as one-size-fits-all solutions intended to apply to all workers. It may be important to implement targeted interventions that address the distinct needs of MHCW. By doing so, all HCWs, regardless of their sociodemographic backgrounds or identities, could feel supported and continue to provide high-quality care for their patients. The aim of this study was to identify and examine interventions specifically designed to support the well-being of MHCW. Additionally, the study analyzed existing literature on well-being outcomes and experiences comparing minority and non-minority HCWs.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted between November 2023 and April 2024 in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA, 2021) (13) guidelines. The study protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, ID# CRD42023478339) prior to commencement of data collection.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed using the following databases: PubMed, Medline, Scopus, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, CINAHL, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, American Doctoral Dissertations, and Open Access Theses and Dissertations. Additional sources such as databases of gray literature, volumes of journals, reference lists of books, book chapters, systematic reviews were also searched. No time or study design restrictions were applied. The search was limited to availability in English. Multiple key terms and Boolean operators such as minority, underrepresented, healthcare worker, well-being, mental health, intervention, and program were used to target relevant papers. Results were limited to publications that included the search terms within their title or abstract text. The reference lists of eligible articles were also hand-searched to identify any additional publications. The detailed search strategy by database is included in Supplementary 1.

Eligibility criteria

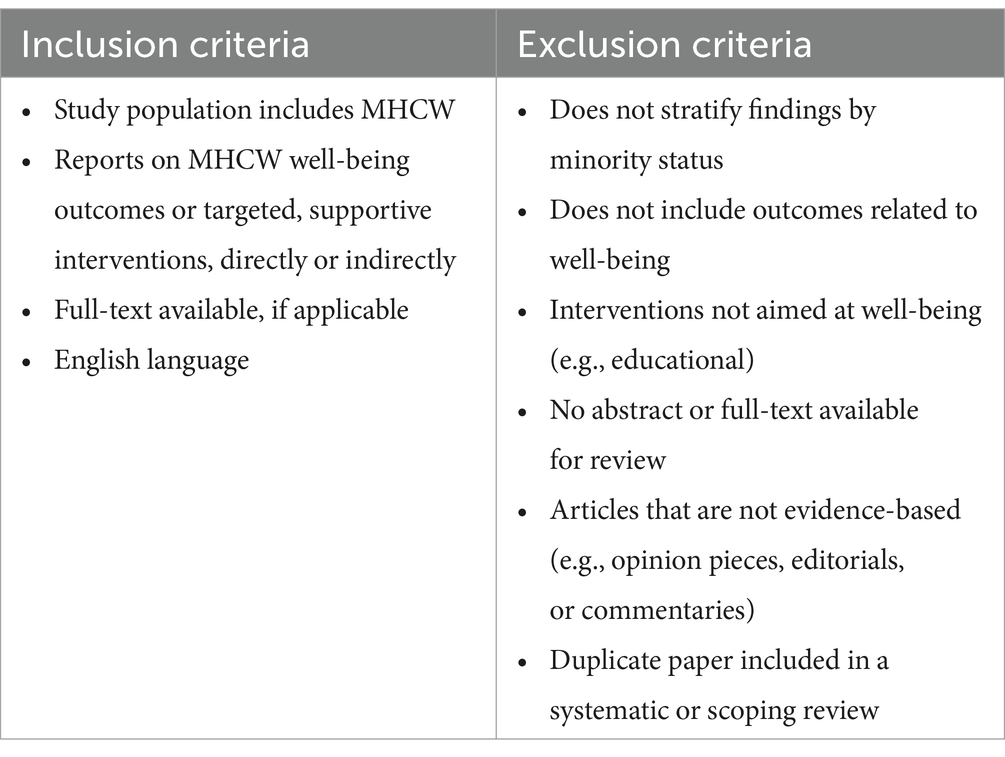

Published papers reporting original or secondary results of quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods research on the well-being of MHCW and targeted program interventions for MHCW were included. All study designs were considered inclusive of other systematic or scoping reviews in an effort to synthesize high-level evidence and reduce duplication of effort. We defined HCWs to be inclusive of physicians, pharmacists, physician assistants, nurses, hospital faculty, and their corresponding students or trainees. We chose to include early-career groups such as students as literature suggests early onset of burnout (14). Similarly, a broad characterization of minority was utilized to include racial/ethnic, gender, sexual, and migrant minority groups. These were defined within the geographic and cultural contexts in which the studies were conducted. The wide-ranging definitions were used capture more relevant data since published literature on this topic are relatively scarce. For inclusion in this review, articles must have included MHCW well-being outcomes or an intervention targeting the well-being of MHCW. Table 1 provides the detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria utilized to determine study eligibility.

Study selection and data extraction

An online systematic review management system, Covidence (Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia),1 was utilized for literature screening and data extraction. There were four reviewers, MM, TB, MC, and WH. Two independent reviewers conducted each title/abstract screening and full-text review. In cases of disagreement, consensus was acquired through discussion. At least one reviewer completed data extraction for selected articles. Extracted data included study title, author(s), date of publication, country, study design, type of HCW, type of MHCW, number of participants, attrition and response rate, well-being measures or interventions, well-being related primary and secondary outcomes (if applicable), and lessons learned.

Data synthesis

Extracted information was exported from Covidence to Microsoft Excel (version 16.81). A spreadsheet was used for organization of the extracted data with a focus on relevant variables. Meta-analysis was not possible due to heterogeneity in the methodological features of the studies. Therefore, descriptive analysis of the included papers was conducted.

Quality assessment

Included studies were categorized as quantitative (randomized, non-randomized, or descriptive), qualitative, mixed-methods, or systematic/scoping review. Due to the variety of study designs included in this review, two comprehensive critical appraisal tools, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT, version 2018) (15, 16) and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Systematic Reviews and Research Syntheses (2015) (17), were utilized. Two reviewers independently assessed all studies and disagreements were addressed through discussion to achieve consensus.

The MMAT is designed for the assessment of five study types: qualitative, quantitative randomized control, quantitative non-randomized, quantitative descriptive, and mixed-methods studies. There are two screening questions: (1) “Are there clear research questions?” and (2) “Do the collected data allow to address the research questions?” (15). The screening questions are followed by 25 appraisal items addressing quality criteria split into five sections corresponding to the specific study design, with each section having five questions. A total of five appraisal items are answered for all qualitative and quantitative study designs. A total of 15 questions are assigned for mixed-method studies as the specific two study designs included plus the mixed-methods-specific questions must be answered; however, the lowest score of the three categories is considered the overall quality. Response options to the series of questions include ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘cannot tell’. The full set of assessment questions can be found elsewhere (15). Quality was categorized as low (MMAT score, 0–2), moderate (MMAT score, 3–4), or high (MMAT score, 5).

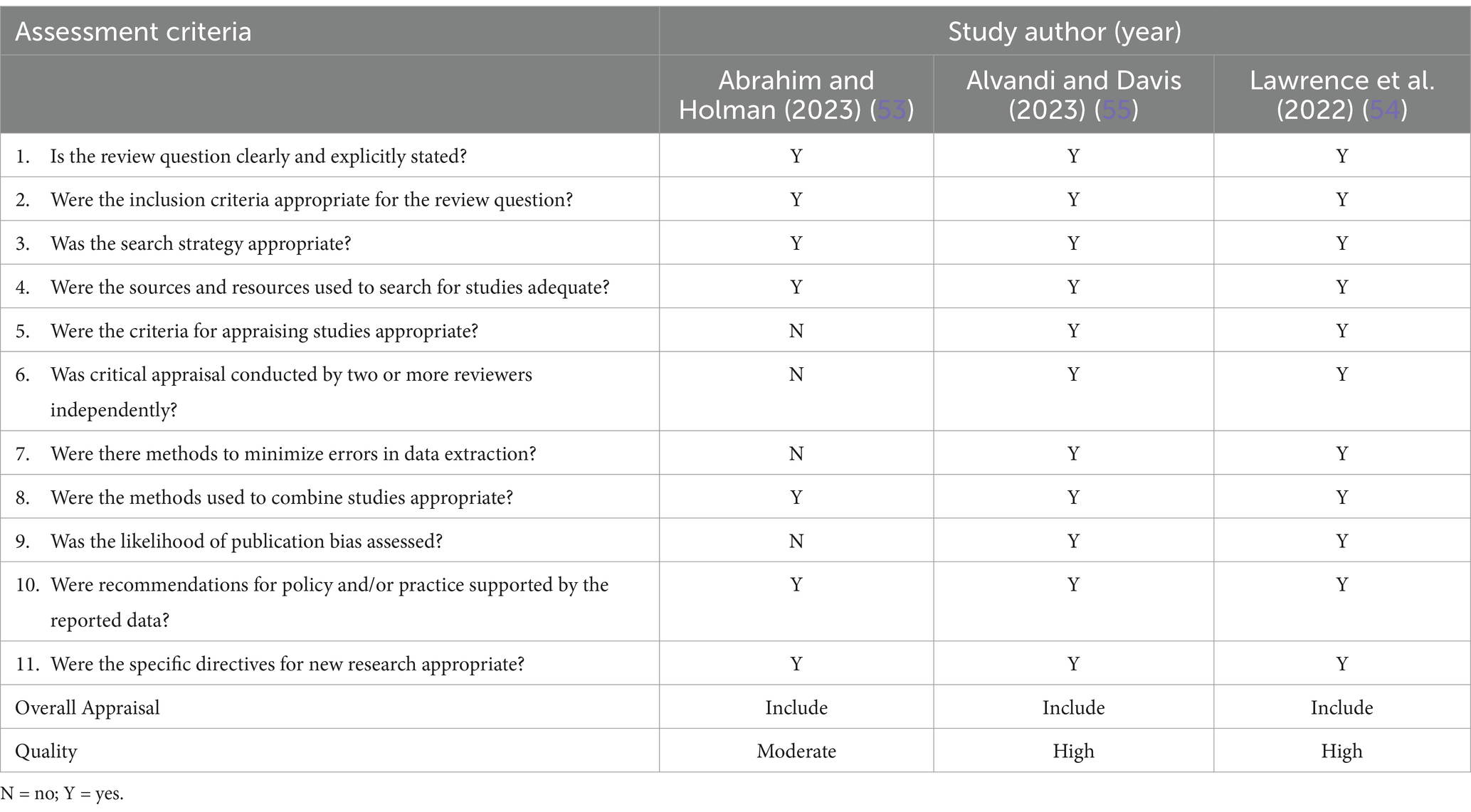

The JBI tool was utilized for the quality appraisal of systematic reviews and scoping reviews. This tool has a total of 11 items with response options of ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unclear’, or ‘not applicable’. Overall quality was reported based on percentage of criteria as low (<40%), moderate (40–80%), or high (>80%).

Results

Study selection

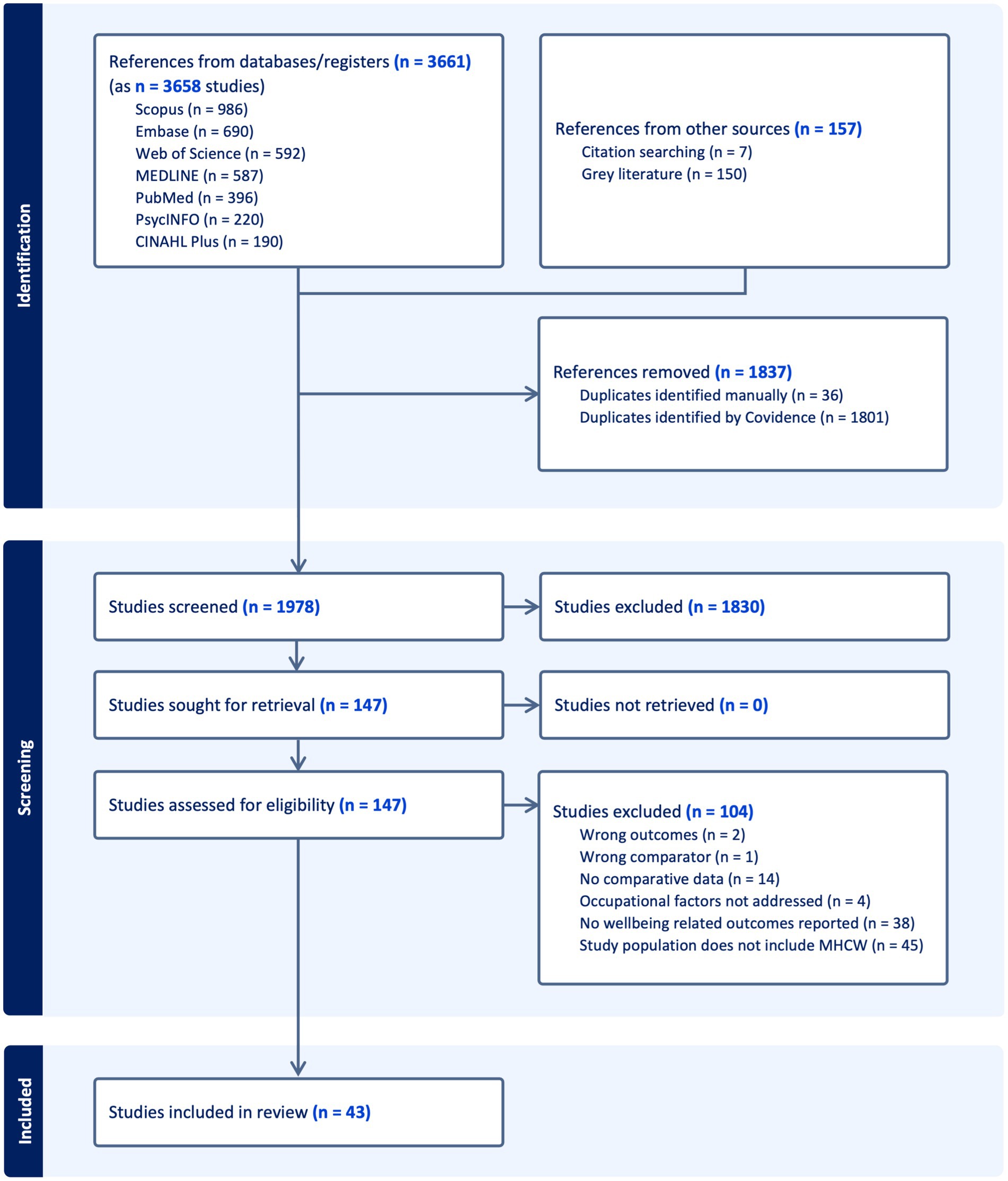

The initial search produced 3,815 records, of which 1,837 duplicates were removed (Figure 1). After screening of the available abstracts and titles by two independent reviewers, 147 studies were eligible for full-text review. Of these, 104 were excluded for various reasons (detailed in Figure 1) resulting in 43 included studies.

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram illustrating the search for relevant studies at different stages including identification, selection, and inclusion of the studies based on predefined criteria.

Study characteristics

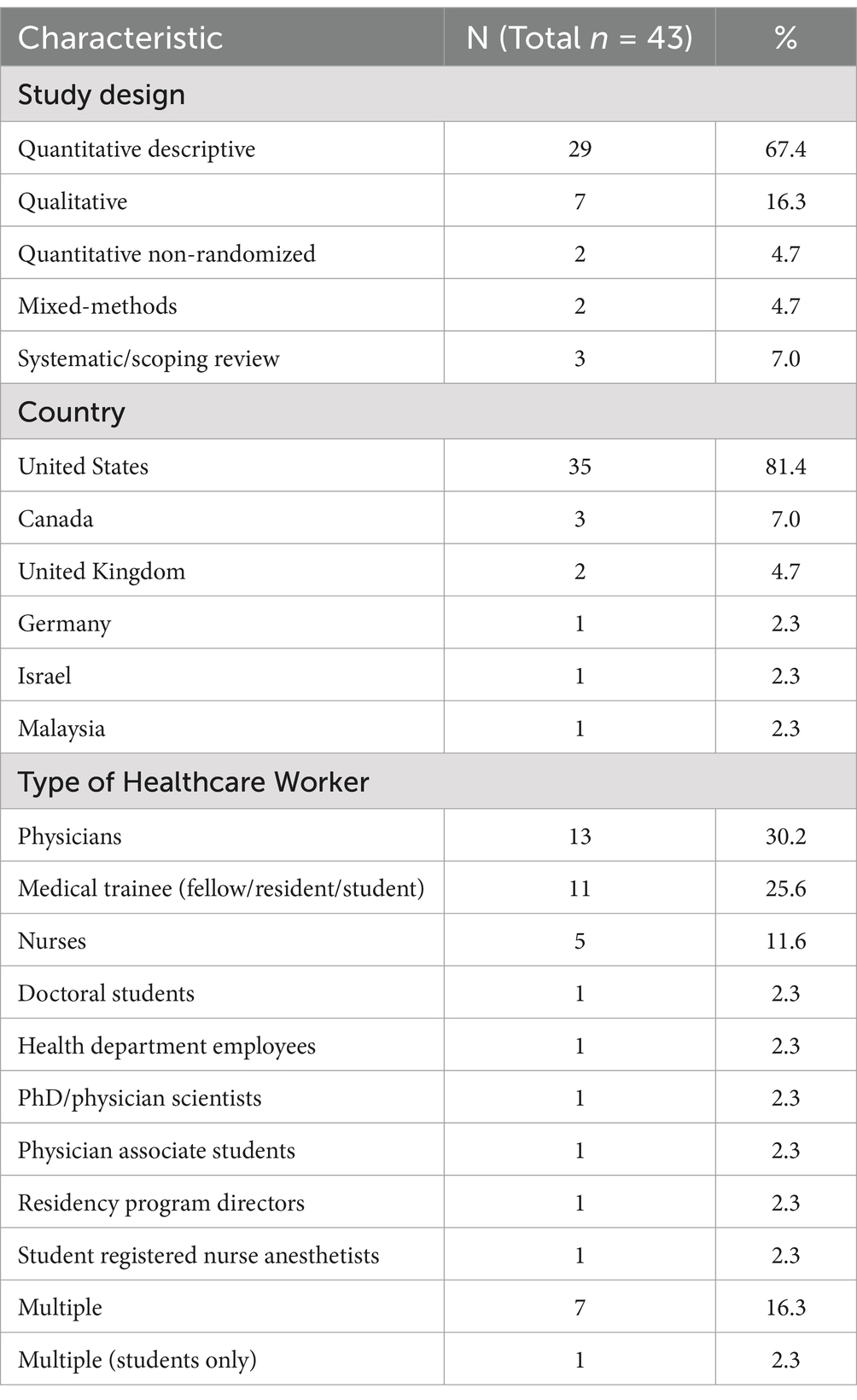

All 43 included studies were written in English and published between 2006 and 2023. Most of the studies (67.4%) utilized quantitative descriptive methods, 7 (16.3%) qualitative, 3 (7.0%) systematic or scoping reviews, 2 (4.7%) quantitative non-randomized, and 2 (4.7%) were mixed-methods studies. No studies utilized a randomized design. Geographic location was mostly the United States (81.4%) followed by Canada (7.0%) and the United Kingdom (4.7%). Other countries included Germany, Israel, and Malaysia. There was wide variability in the types of healthcare professionals included: physicians, medical trainees (fellows, residents, and students), nurses, health department employees, physician scientists, and other clinical-based students. A majority of studies defined minority status by race/ethnicity. Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of the included studies.

Studies measured several well-being domains such as burnout, emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, job satisfaction, intent to leave, depression, anxiety, and discrimination. Many authors created their own questionnaires or adapted already existing ones. Burnout was the most commonly assessed well-being outcome. Multiple validated and non-validated tools were utilized in assessing burnout; 10 studies utilized the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) (18) and 5 used the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) (19). All authors used paper-and-pencil or web-based/electronic self-report questionnaires and nine studies used semi-structured interviews to identify qualitative themes. A majority of studies used convenience sampling to identify participants, however we included data from 4 large national systematic surveys that compare well-being measures for racial/ethnic minority and non-minority HCWs.

Study quality

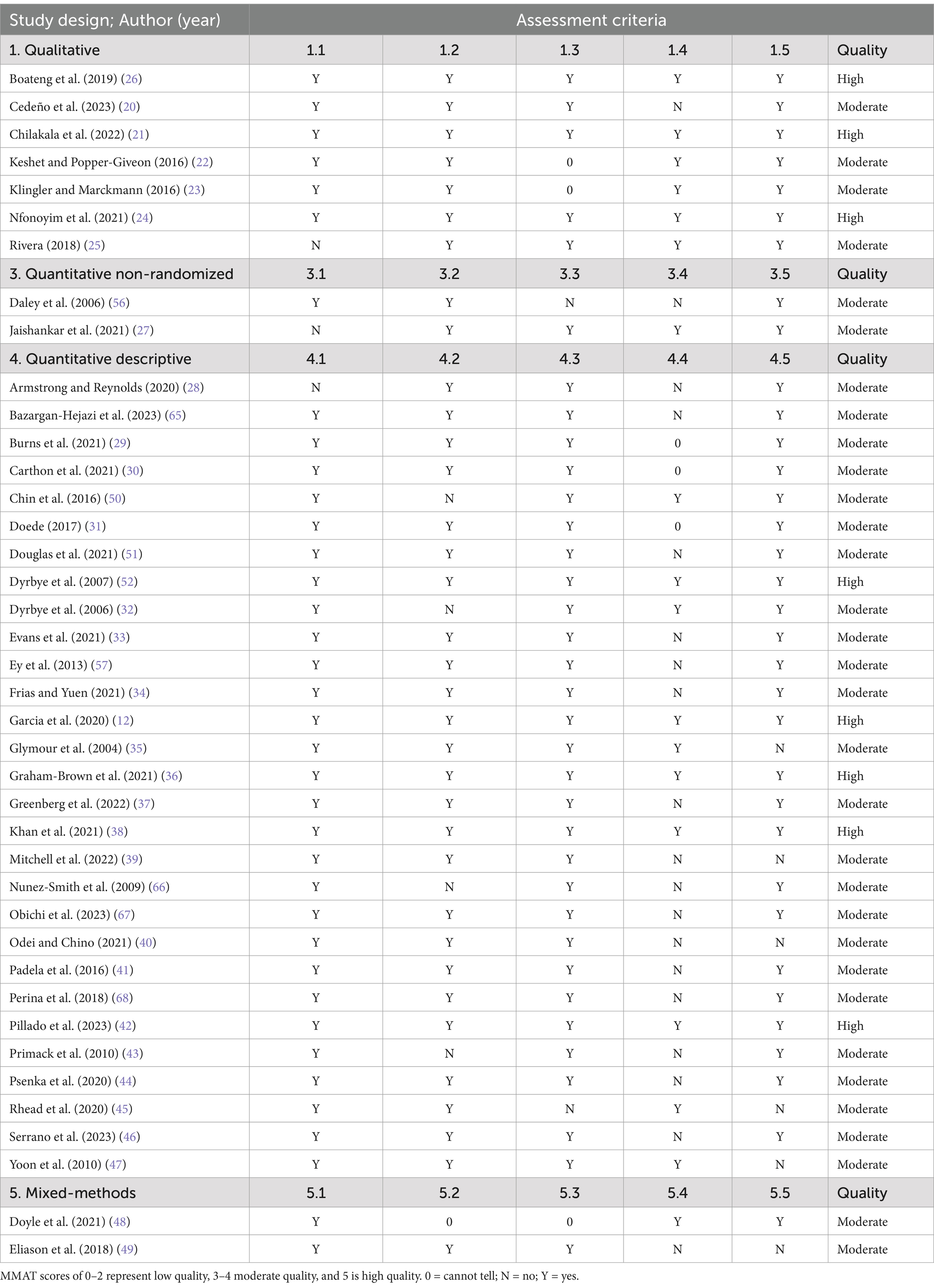

The MMAT was used to evaluate 40 studies (Table 3). All of these had a response of ‘yes’ to the two screening questions, which were not included in Table 3. MMAT questions 2.1 to 2.5 were also not included as no studies met the design criteria. All primary studies met more than half of the quality criteria of MMAT and used an appropriate sample frame to address the target population. However, the adequacy of the sample size and the use of valid methods was unclear for several studies. Two systematic reviews and 1 scoping review used the JBI appraisal tool. Table 4 shows appraisal results of JBI-evaluated studies. Overall, 76.7% of the included studies were of moderate methodological quality and 23.3% were of high quality. No studies were rated as low quality.

Table 4. Appraisal of systematic and scoping reviews using JBI critical appraisal checklist for systematic reviews and research syntheses.

Study outcomes

Well-being in minority versus non-minority HCWs

Most qualitative studies (85.7%) did not have non-minority comparison groups, however all identified negative experiences for MHCW (20–25). The qualitative themes identified included exposure to microaggressions, institutional ostracizing, tense working environment, racial isolation, lack of culturally diverse mentors, stereotypical or offensive attitude from patients, unprofessional encounters from peers, pressure to prove themselves as a result of negative experiences, and fear of being othered. Experiences of microaggression and discrimination were reported by both racial/ethnic and gender/sexual MHCW.

A majority of studies (n = 29, 67.4%) compared the well-being of minority and non-minority HCWs either qualitatively or quantitively. Of these, the vast majority (82.8%) noted some worse outcomes in the MHCW population (26–49). One study found no significant overall difference in burnout by gender or ethnicity (50). Three studies reported better well-being among MHCW in comparison to their non-minority counterparts (12, 51, 52). Garcia et al. (12) reported lower adjusted odds of burnout among minority racial/ethnic groups in comparison to non-Hispanic white participants (Hispanic/Latinx physicians, odds ratio [OR] = 0.63, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.47, 0.86]; non-Hispanic Black physicians, OR = 0.49, 95% CI [0.30, 0.79]). This study was a secondary analysis of survey data from 4,424 physicians, using MBI to assess burnout. Authors noted several limitations including a much lower response rate for minority physicians and the utilization of the American Medical Association’s Physician Masterfile dataset to identify minority physicians, which lacked comprehensive racial/ethnic information. Additionally, Abrahim and Holman (53) conducted a scoping review of literature on the well-being of racial and ethnic minority nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Two studies in their review documented greater anxiety among white nurses, but contained relatively small, predominantly white, unrepresentative samples. The authors concluded that “findings for the nurses of color may not be reliable because the samples included few racial and ethnic minority nurses.” (53).

In regards to overall burnout scores, two studies found no significant difference between minority and non-minority medical students (28, 32). However, one of these studies (28) (n = 162) showed significantly higher rates of personal burnout among racial/ethnic minority medical students (p = 0.001). The second study (32) surveyed medical students (n = 545) and although there were similarly no overall differences in burnout, emotional exhaustion, or depersonalization, minority medical students had a significantly lower sense of personal accomplishment (42% vs. 28%; p = 0.02). Also of note, minority students were less likely to respond to the survey (37% vs. 50%; p < 0.001).

A systematic review by Lawrence et al. (54) that focused on the racial/ethnic differences in burnout rates had inconclusive findings, and recommended increased evaluation and focus on systemic factors that may be at play. Three of the 16 studies in this review did not include HCWs. Additionally, Lawrence et al. noted that their findings were nuanced and several of the included studies had methodological issues.

The majority of studies used convenience sampling to identify participants, but our sample also included data from four large national systematic surveys that compared well-being measures for racial minority and non-minority HCWs. The largest of these (31) (n = 27,953) was from the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses. It found that Asians had lower odds (p < 0.001) of job dissatisfaction and having changed jobs (p < 0.001) compared to white counterparts, while Black and Hispanic participants showed no significant association. The authors concluded that race/ethnicity was a predictor of job satisfaction and turnover and Asian nurses showed more positive outcomes than white nurses, while Black and Hispanic individuals showed significantly worse outcomes. Another large national survey (30) (n = 14,778) reporting on the data from RN4CAST-U.S found that Black nurses reported greater job dissatisfaction (p < 0.001) and intent to leave within a year (p < 0.001) in comparison to white nurses. A national training survey from the UK General Medical Council of 627 renal medicine physicians similarly suggested that racial/ethnic minority medical trainees reported higher burnout rates than white trainees (36).

However, data from a national physician survey (n = 3,096) from the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) Family Medicine Continuing Certification Examination Registration questionnaire showed that minority physicians were significantly less likely to report depersonalization, both as a binary variable (p = 0.03) and continuous variable (p < 0.001), less likely to report emotional exhaustion as a continuous variable (p = 0.04), but equally likely to report emotional exhaustion (p = 0.09) (51). Minority physicians were more likely to work in counties with higher diversity index and authors concluded that working in racially and ethnically diverse environments could be a mediating factor resulting in a lower frequency of emotional exhaustion and feelings of depersonalization (51).

Among studies that compared outcomes between men and women (n = 16), 68.8% found worse well-being among women HCWs. Yoon et al. (47) explored conflict as a correlate of burnout among HCWs. No association was found between conflict over treatment decisions and race/ethnicity, but there was a significant positive association among women physicians. Reasons for this association are not well understood, but Yoon et al. (47) suggest that female patients are more likely to choose female physicians and more willing to voice disagreements with physicians of the same gender. Five studies specifically investigated gender differences in burnout. Two of these studies did not find any difference in burnout among male and female HCWs (38, 50). One study found that male renal trainees reported higher burnout rates than women colleagues (36). However, a systematic review of 11 studies by Alvandi and Davis (55) showed that female HCWs reported greater burnout.

Sexual minority HCWs were examined in four studies. Key findings include discomfort in ‘coming-out’ in the workplace (49), being socially excluded (25), and greater odds of depressive or anxiety symptoms than heterosexual counterparts (33).

Well-being interventions

Only one study, by Daley et al. (56) included a specific MHCW-focused well-being intervention. They examined the change in retention rate among health center faculty after the implementation of the Junior Faculty Development Program for minority-identifying faculty which provided development workshops, counseling, and mentoring. There was a non-significant increase in retention rate of 15% among minority-identifying faculty in academic medicine. One other study by Ey et al. (57) included an intervention that was not tailored to the MHCW population. They evaluated a Resident Wellness Program that provided free, on-site counseling for all medical trainees regardless of minority status. Findings indicated that MHCW were significantly less likely to utilize the program.

Details of study population, measures, outcomes, and lessons learned of all included studies are summarized in Supplementary 2.

Discussion

Contrary to our expectations, there were few publications on supportive interventions that specifically target MHCW. We found only one published MHCW-specific intervention, a development and mentorship program which showed no significant association with retention rate (56). Instead, findings from this review suggest that creating a safe work environment and empowering MHCW to participate in well-being interventions may be important. One study (57) showed that MHCW were less likely that their non-minority counterparts to utilize their well-being program. Several studies found discomfort among HCWs in receiving support, and that time away from work may be a potential barrier to utilizing well-being programs (57, 58). These barriers may be greater for MHCW experiencing discrimination and other systemic challenges, who may want to avoid any additional discomfort in the workplace.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to comprehensively explore the well-being of MHCW. We aimed to cover a broad topic area as we felt that any narrowing of the well-being definition may result in selection bias. The search included a broad range of search terms with minimal limitations. All study designs were included and no studies were excluded based on quality. Uniformity in the critical appraisal process was prioritized by usage of the MMAT which encompassed most study designs. This important review provided context and awareness to how intersectional factors (e.g., race, gender, sexual orientation) affects the well-being of the minority-identifying healthcare workforce, highlighting the importance of inclusivity and equity in the workplace and providing evidence-based syntheses for policymakers to improve the well-being of MHCW.

Consistent with previous literature, we found inconsistencies in well-being outcomes among MHCW. There are potential reasons for these discrepant findings. It is important to consider that minority populations may express stress differently which could affect scores on well-being measures. The validity of previously established stress models has been questioned for minority populations. Ivey and Gauch (59) demonstrated that “minority communities have different distributions of emotions than the general population” and that existing models may not be representative as they are not trained with minority-specific data. Singh et al. (60) found that chronic stress among individuals who experience continuous discrimination leads to emotional dysregulation and emotional suppression. They argued that the “impact of any instance of social isolation, discrimination, and bias is directly responsible for suppression of emotional expression” (60) whether that be negative or positive responses. This potential reporting bias should be considered in interpreting our findings.

Notably, larger, well-represented national surveys tended to find higher rates of burnout among MHCW. It also appeared that burnout among MHCW can be modulated by a variety of professional and environmental factors. For example, working in racially and ethnically diverse environments was found to be a mediating factor reducing burnout among minority family physicians (51). MHCW may feel less minoritized in settings that promote diversity. Similarly, in a survey of 519 oncologists, 48 minority radiation oncologists reported greater burnout rates than non-minority, but minority medical oncologists reported lower burnout rates than non-minority respondents. This suggests a potential influence of differences in work environment on burnout (40).

Psychological distress can be cumulative over the life course and can also be compounded by the presence of multiple stressors. For example, identifying with more than one type of minority or identifying with an ‘invisible’ minority group may be associated with worse outcomes. Those identifying as sexual minorities, in particular, are sometimes able to make a ‘choice’ about coming-out to colleagues and patients, as opposed to those with racial/ethnic minority status which may be more visibly apparent. This could worsen well-being among the LGBTQ+ community as they internalize negative feelings. Future studies should control for or evaluate the differences associated with a particular minority group, however this is understandably challenging given the concept of intersectionality in identity. There is a complex interplay of various facets of identity, such as ethnicity, gender, sexuality, professional seniority, etc., that do not exist in isolation but rather intersect in various ways to shape an individual’s context (61).

There are multiple benefits to an inclusive and supportive work environment in promoting well-being among MHCW. Wolfe (62) theorizes that LGBTQ+ healthcare professionals, similar to other minority-identifying populations, encounter incongruence between their personal and professional identities, and thus have differential experiences with mental distress and burnout. They also call for “intersectional actions that recognize and mitigate spaces of inequality that constrain the benefit marginalized professionals receive from improvement efforts” (62) such as interventions tailored to specific minority group needs. Brown et al. (63) emphasize that medical education diversity goals are only attainable “when inclusion and equity are on the table as well” since a supportive work environment must address systemic inequalities in order to promote well-being among the workforce. Prioritizing diversity and inclusion policies requires a systemic approach of stakeholder collaboration, strategy evaluation, and community engagement (64). This will also have a direct impact on the retention of MHCW. Additionally, a healthcare workplace that closely represents the community it serves will improve the quality of care (64).

Limitations

This study has some limitations. There was methodological heterogeneity in the types of well-being outcomes and the measurement tools included in studies. However, there was less heterogeneity in the study populations. Studies also utilized different definitions of “minority” with most focusing on racial/ethnic minorities, while others included immigration status and religious affiliation. This prevented aggregation or quantitative comparisons of results. Furthermore, findings from different countries were included in this review without consideration of the cultural, political, and economic contexts surrounding healthcare. Therefore, the results should be interpreted in context.

Conclusion

There is paucity of published evidence on supportive interventions to address MHCW well-being. The results of our review do not fully support the need for well-being programs tailored solely to MHCW. However, we could only find one study specifically supporting MHCW’s. It is possible that systematic barriers such as discrimination are preventing MHCW’s participation in support programs. Given the complex and intersectional nature of identity, it is understandable that there is no one “size” approach even among a particular population of MHCW. Rather, a broad public health approach should be considered to mitigate the negative health outcomes and improve utilization of support programs, including the development and implementation of policies surrounding diversity and inclusion, mental health services, and cultural competency. By increasing focus on the barriers to well-being faced by MHCW, the well-being of the entire healthcare workforce could be improved and subsequently translate into better patient care. We recommend future research on MHCW utilizing validated well-being measures and incorporating a wider geographical variation beyond North America and Europe, especially from underrepresented countries.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

TB: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Methodology. MM: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. MC: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. WH: Data curation, Software, Writing – review & editing. CW: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. KW: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. CC: Writing – review & editing. MB: Writing – review & editing. GE: Writing – review & editing. HM: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. AW: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) [Thriving Together: Supporting Resilience in the Healthcare Workforce. 1U3MHP45382–01-00].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1531090/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

1. Well-Being Index Team. How physician wellness impacts quality of care. MedEd web solutions. (2019). Available at: https://www.mededwebs.com/blog/how-physician-wellness-impacts-quality-of-care (Accessed March 25, 2024)

2. World Health Organization. Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International classification of diseases. (2019). Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (Accessed March 20, 2024).

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health workers face a mental health crisis. (2023). Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/health-worker-mental-health/index.html (Accessed March 25, 2024).

4. World Health Organization. World failing in ‘our duty of care’ to protect mental health and well-being of health and care workers, finds report on impact of COVID-19. (2022). Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-10-2022-world-failing-in--our-duty-of-care--to-protect-mental-health-and-wellbeing-of-health-and-care-workers--finds-report-on-impact-of-covid-19 (Accessed January 8, 2025)

5. Patel, RS, Bachu, R, Adikey, A, Malik, M, and Shah, M. Factors related to physician burnout and its consequences: a review. Behav Sci (Basel). (2018) 8:98. doi: 10.3390/bs8110098

6. Hall, LH, Johnson, J, Watt, I, Tsipa, A, and O’Connor, DB. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0159015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015

7. Heeb, JL, and Haberey-Knuessi, V. Health professionals facing burnout: what do we know about nursing managers? Nurs Res Pract. (2014) 2014:681814. doi: 10.1155/2014/681814

8. Cimiotti, JP, Aiken, LH, Sloane, DM, and Wu, ES. Nurse staffing, burnout, and health care-associated infection. Am J Infect Control. (2012) 40:486–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.02.029

9. Schlak, AE, Aiken, LH, Chittams, J, Poghosyan, L, and McHugh, M. Leveraging the work environment to minimize the negative impact of nurse burnout on patient outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:610. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020610

10. Moran, D, Wu, AW, Connors, C, Chappidi, MR, Sreedhara, SK, Selter, JH, et al. Cost-benefit analysis of a support program for nursing staff. J Patient Saf. (2020) 16:e250–4. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000376

11. Xierali, IM, and Nivet, MA. The racial and ethnic composition and distribution of primary care physicians. J Health Care Poor Underserved. (2018) 29:556–70. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2018.0036

12. Garcia, LC, Shanafelt, TD, West, CP, Sinsky, CA, Trockel, MT, Nedelec, L, et al. Burnout, depression, career satisfaction, and work-life integration by physician race/ethnicity. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2012762. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12762

13. Page, MJ, McKenzie, JE, and Bossuyt, PM. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. (2021) 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

14. Fang, DZ, Young, CB, Golshan, S, Moutier, C, and Zisook, S. Burnout in premedical undergraduate students. Acad Psychiatry. (2012) 36:11–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.10080125

15. Hong, QN, Pluye, P, and Fabregues, S, Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018. (2018). Available at: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (Accessed January 8, 2024).

16. Hong, QN, Pluye, P, Fàbregues, S, Bartlett, G, Boardman, F, Cargo, M, et al. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: a modified e-Delphi study. J Clin Epidemiol. (2019) 111:49–59.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.008

17. Aromataris, E, Fernandez, R, Godfrey, CM, Holly, C, Khalil, H, and Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. JBI Evidence Implementation. (2015) 13:132–40. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055

18. Maslach, C, Jackson, SE, and Leiter, MP. The Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. (1997). Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277816643_The_Maslach_Burnout_Inventory_Manual (Accessed April 9, 2024).

19. Kristensen, TS, Borritz, M, Villadsen, E, and Christensen, KB. The Copenhagen burnout inventory: a new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress. (2005) 19:192–207. doi: 10.1080/02678370500297720

20. Cedeño, B, Shimkin, G, Lawson, A, Cheng, B, Patterson, DG, and Keys, T. Positive yet problematic: lived experiences of racial and ethnic minority medical students during rural and urban underserved clinical rotations. J Rural Health. (2023) 39:545–50. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12745

21. Chilakala, A, Camacho-Rivera, M, and Frye, V. Experiences of race-and gender-based discrimination among black female physicians. J Natl Med Assoc. (2022) 114:104–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2021.12.008

22. Keshet, Y, and Popper-Giveon, A. Work experiences of ethnic minority nurses: a qualitative study. Isr J Health Policy Res. (2016) 5:18. doi: 10.1186/s13584-016-0076-5

23. Klingler, C, and Marckmann, G. Difficulties experienced by migrant physicians working in German hospitals: a qualitative interview study. Hum Resour Health. (2016) 14:57–7. doi: 10.1186/s12960-016-0153-4

24. Nfonoyim, B, Martin, A, Ellison, A, Wright, JL, and Johnson, TJ. Experiences of underrepresented faculty in pediatric emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. (2021) 28:982–92. doi: 10.1111/acem.14191

25. Rivera, AD. Perceived stigma and discrimination as barriers to practice for LGBTQ mental health clinicians: A minority stress perspective. ProQuest Information & Learning; (2018). Available at: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=psyh&AN=2017-43828-114&site=ehost-live&scope=site&authtype=ip,shib&custid=s3555202 (Accessed January 8, 2024).

26. Boateng, G, Schuster, R, and Boateng, M. Uncovering a health and wellbeing gap among professional nurses: situated experiences of direct care nurses in two Canadian cities. Soc Sci Med. (2019) 242:112568. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112568

27. Jaishankar, D, Dave, S, and Tatineni, S. Burnout, stress, and loneliness among u.s. medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. (2021) 36:1–469. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06830-5

28. Armstrong, M, and Reynolds, K. Assessing burnout and associated risk factors in medical students. J Natl Med Assoc. (2020) 112:597–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.05.019

29. Burns, KEA, Pattani, R, Lorens, E, Straus, SE, and Hawker, GA. The impact of organizational culture on professional fulfillment and burnout in an academic department of medicine. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0252778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252778

30. Carthon, JMB, Travers, JL, Hounshell, D, Udoeyo, I, and Chittams, J. Disparities in nurse job dissatisfaction and intent to leave: implications for retaining a diverse workforce. J Nurs Adm. (2021) 51:310–7. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0000000000001019

31. Doede, M. Race as a predictor of job satisfaction and turnover in US nurses. J Nurs Manag. (2017) 25:207–14. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12460

32. Dyrbye, LN, Thomas, MR, Huschka, MM, Lawson, KL, Novotny, PJ, Sloan, JA, et al. A multicenter study of burnout, depression, and quality of life in minority and nonminority US medical students. Mayo Clin Proc. (2006) 81:1435–42. doi: 10.4065/81.11.1435

33. Evans, KE, Holmes, MR, Prince, DM, and Groza, V. Social work doctoral student well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive study. Int J Dr Stud. (2021) 16:569–92. doi: 10.28945/4840

34. Frias, D, and Yuen, CX. The physician assistant student experience: diversity, stress, and school membership. J Physician Assist Educ. (2021) 32:113–5. doi: 10.1097/JPA.0000000000000362

35. Glymour, MM, Saha, S, and Bigby, J. Physician race and ethnicity, professional satisfaction, and work-related stress: results from the physician Worklife study. J Natl Med Assoc. (2004) 96:1283–94.

36. Graham-Brown, MP, Beckwith, HK, O’Hare, S, Trewartha, D, Burns, A, and Carr, S. Impact of changing medical workforce demographics in renal medicine over 7 years: analysis of GMC national trainee survey data. Clin Med (Lond). (2021) 21:e363–70. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-1065

37. Greenberg, AL, Cevallos, JR, Ojute, FM, Davis, DL, Greene, WR, and Lebares, CC. The general surgery residency experience: a multicenter study of differences in wellbeing by race/ethnicity. Ann Surg Open. (2022) 3:e187. doi: 10.1097/AS9.0000000000000187

38. Khan, N, Palepu, A, Dodek, P, Salmon, A, Leitch, H, Ruzycki, S, et al. Cross-sectional survey on physician burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic in Vancouver, Canada: the role of gender, ethnicity and sexual orientation. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e050380. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050380

39. Mitchell, AK, Apenteng, BA, and Boakye, KG. Examining factors associated with minority turnover intention in state and local public health organizations: the moderating role of race in the relationship among supervisory support, job satisfaction, and turnover intention. J Public Health Manag Pract. (2022) 28:E768–77. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000001571

40. Odei, B, and Chino, F. Incidence of burnout among female and minority Faculty in Radiation Oncology and Medical Oncology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2021) 111:S28–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2021.07.092

41. Padela, AI, Adam, H, Ahmad, M, Hosseinian, Z, and Curlin, F. Religious identity and workplace discrimination: a national survey of American Muslim physicians. AJOB Empirical Bioethics. (2016) 7:149–59. doi: 10.1080/23294515.2015.1111271

42. Pillado, E, Li, R, and Eng, J. Persistent racial discrimination among vascular surgery trainees threatens wellness. J Vasc Surg. (2023) 77:262–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2022.09.011

43. Primack, BA, Dilmore, TC, Switzer, GE, Bryce, CL, Seltzer, DL, Li, J, et al. Burnout among early career clinical investigators. Clin Transl Sci. (2010) 3:186–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2010.00202.x

44. Psenka, TM, Freedy, JR, Mims, LD, DeCastro, AO, Berini, CR, Diaz, VA, et al. A cross-sectional study of United States family medicine residency programme director burnout: implications for mitigation efforts and future research. Fam Pract. (2020) 37:772–8. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmaa075

45. Rhead, RD, Chui, Z, Bakolis, I, Gazard, B, Harwood, H, MacCrimmon, S, et al. Impact of workplace discrimination and harassment among National Health Service staff working in London trusts: results from the TIDES study. BJPsych Open. (2020) 7:e10. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.137

46. Serrano, Y, Dalley, CB, Crowell, NA, and Eshkevari, L. Racial and ethnic discrimination during clinical education and its impact on the well-being of nurse anesthesia students. AANA J. (2023) 91:259–66.

47. Yoon, J, Rasinski, K, and Curlin, F. Conflict and emotional exhaustion in obstetrician-gynaecologists: a national survey. J Med Ethics. (2010) 36:731–5. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.037762

48. Doyle, JM, Morone, NE, Proulx, CN, Althouse, AD, Rubio, DM, Thakar, MS, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on underrepresented early-career PhD and physician scientists. J Clin Transl Sci. (2021) 5:e174. doi: 10.1017/cts.2021.851

49. Eliason, MJ, Streed, CJ, and Henne, M. Coping with stress as an LGBTQ+ health care professional. J Homosex. (2018) 65:561–78. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1328224

50. Chin, RW, Chua, Y, and Chu, M. Prevalence of burnout among Universiti Sains Malaysia medical students. Educ Med J. (2016) 8:61–74. doi: 10.5959/eimj.v8i3.454

51. Douglas, M, Coman, E, Eden, AR, Abiola, S, and Grumbach, K. Lower likelihood of burnout among family physicians from underrepresented racial-ethnic groups. Ann Fam Med. (2021) 19:342–50. doi: 10.1370/afm.2696

52. Dyrbye, LN, Thomas, MR, Eacker, A, Harper, W, Massie, FS, Power, DV, et al. Race, ethnicity, and medical student well-being in the United States. Arch Intern Med. (2007) 167:2103–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2103

53. Abrahim, H, and Holman, E. A scoping review of the literature addressing psychological well-being of racial and ethnic minority nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Outlook. (2023) 71:101899. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2022.11.003

54. Lawrence, J, Davis, B, Corbette, T, Hill, E, Williams, D, and Reede, J. Racial/ethnic differences in burnout: a systematic review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2022) 9:257–69. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00950-0

55. Alvandi, M, and Davis, J. Risk factors associated with burnout among medical faculty: A systematic review. Pielegniarstwo XXI wieku/Nursing in the 21st Century. 22:208–213. doi: 10.2478/pielxxiw-2023-0030

56. Daley, S, Wingard, DL, and Reznik, V. Improving the retention of underrepresented minority faculty in academic medicine. J Natl Med Assoc. (2006) 98:1435–40.

57. Ey, S, Moffit, M, Kinzie, JM, Choi, D, and Girard, DE. “If you build it, they will come”: attitudes of medical residents and fellows about seeking services in a resident wellness program. J Grad Med Educ. (2013) 5:486–92. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00048.1

58. McKevitt, C, and Morgan, M. Anomalous patients: the experiences of doctors with an illness. Sociol Health Illn. (1997) 19:644–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.1997.tb00424.x

59. Ivey, J, and Gauch, S. Improving minority stress detection with emotions. (2023). Available at: http://arxiv.org/abs/2311.17676 (Accessed April 17, 2024)

60. Singh, A, Dandona, A, Sharma, V, and Zaidi, SZH. Minority stress in emotion suppression and mental distress among sexual and gender minorities: a systematic review. Ann Neurosci. (2023) 30:54–69. doi: 10.1177/09727531221120356

61. Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics University of Chicago Legal Forum (1989) 8. Available at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

62. Wolfe, A. Incongruous identities: mental distress and burnout disparities in LGBTQ+ health care professional populations. Heliyon. (2023) 9:e14835. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14835

63. Brown, Z, Al-Hassan, RS, and Barber, A. Inclusion and equity: experiences of underrepresented in medicine physicians throughout the medical education continuum. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. (2021) 51:101089. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2021.101089

64. Stanford, FC. The importance of diversity and inclusion in the healthcare workforce. J Natl Med Assoc. (2020) 112:247–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.03.014

65. Bazargan-Hejazi, S, Dehghan, K, and Chou, S. Hope, optimism, gratitude, and wellbeing among health professional minority college students. J Am Coll Heal. (2023) 71:1125–33. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.1922415

66. Nunez-Smith, M, Pilgrim, N, Wynia, M, Desai, MM, Bright, C, Krumholz, HM, et al. Health care workplace discrimination and physician turnover. J Natl Med Assoc. (2009) 101:1274–82. doi: 10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31139-1

67. Obichi, CC, Omenka, O, Perkins, SM, and Oruche, UM. Experiences of minority frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. (2023) 11:3818–28. doi: 10.1007/s40615-023-01833-w

Keywords: well-being, minority healthcare workers, burnout, supportive interventions, peer support

Citation: Bafna T, Malik M, Choudhury MC, Hu W, Weston CM, Weeks KR, Connors C, Burhanullah MH, Everly G, Michtalik HJ and Wu AW (2025) Systematic review of well-being interventions for minority healthcare workers. Front. Med. 12:1531090. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1531090

Edited by:

Salvatore Zaffina, Bambino Gesù Children’s Hospital (IRCCS), ItalyReviewed by:

Luis Felipe Dias Lopes, Federal University of Santa Maria, BrazilJennifer Creese, University of Leicester, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Bafna, Malik, Choudhury, Hu, Weston, Weeks, Connors, Burhanullah, Everly, Michtalik and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mansoor Malik, bW1hbGlrNEBqaG1pLmVkdQ==

†Present Address: Tanvi Bafna, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, United States

Tanvi Bafna

Tanvi Bafna Mansoor Malik

Mansoor Malik Mohua C. Choudhury1

Mohua C. Choudhury1 Kristina R. Weeks

Kristina R. Weeks M. Haroon Burhanullah

M. Haroon Burhanullah