94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Med. , 03 March 2025

Sec. Healthcare Professions Education

Volume 12 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2025.1522411

This article is part of the Research Topic Nurturing Medical Professionalism in Different Cultural Contexts View all 5 articles

Asil Sadeq1*

Asil Sadeq1* Shaista S. Guraya2

Shaista S. Guraya2 Brian Fahey1

Brian Fahey1 Eric Clarke1

Eric Clarke1 Abdelsalam Bensaaud3

Abdelsalam Bensaaud3 Frank Doyle3

Frank Doyle3 Grainne P. Kearney4

Grainne P. Kearney4 Fionnuala Gough1

Fionnuala Gough1 Mark Harbinson4

Mark Harbinson4 Salman Yousuf Guraya5

Salman Yousuf Guraya5 Denis W. Harkin1

Denis W. Harkin1Introduction: Medical professionalism (MP) is a vital competency in undergraduate medical students as it enhances the quality and safety of patient care as it includes professional values, attitudes and professional behaviours (PB). However, medical institutes are uncertain about how optimally it can be learnt and assessed. This review aims to systematically provide a summary of evidence from systematic reviews reporting MP educational interventions, their outcomes and sustainability to foster PB.

Methods: Eight major databases (CINAHL, EMBASE, ERIC, Health business, Medline, OVID, PsycINFO, SCOPUS and Web of Science) and grey literature were systematically searched from database inception to June 2024. The inclusion criteria were (1) systematic review studies (2) of educational interventions of any type; (3) targeting any aspect of MP; (4) provided to undergraduate medical students; and (5) with no restrictions on comparator group or outcomes assessed. A qualitative narrative summary of included reviews was conducted as all included reviews did not conduct quantitative nor meta-analysis of results but rather a qualitative summary. Methodological quality of included reviews was assessed using A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) 2 tool.

Results: The search identified 397 references for eligibility screening. Ultimately, eight systematic reviews were deemed eligible for inclusion. The majority of these reviews have reported a successful improvement in various aspects of MP (i.e., MP as a whole, empathy and compassion) through teaching and exposure to hidden curriculum. The included studies displayed significant methodological heterogeneity, with varying study designs and assessment methodologies to professional outcomes. A gap remains in reporting the sustainable effect on professionalism traits and on a standardised approach to MP teaching.

Conclusion: This review suggests that more interventions are needed in this area with a focus on methodological quality and teaching methods in a multicultural context to support PB and professional identity formation.

Clinical trial registration: PROSPERO [CRD42024495689].

Medical professionalism (MP) is defined as encompassing a range of values, professional behaviours (PB), and attitudes that are expected from healthcare care professionals to maintain public trust and ensure patient safety (1). The evolution of MP towards a more patient-centred approach has significantly escalated over time, particularly in the late 20th century (2–5). Today, MP encompasses a range of attributes, including compassion, integrity, accountability, and a commitment to continuous learning (1). MP is critical for maintaining clinical competence and ensuring that healthcare decisions prioritize patient welfare above all other considerations (6). As modern healthcare becomes increasingly complex, driven by technological advances and ethical challenges, maintaining high standards of MP remains essential for promoting equitable, compassionate, and patient-centred care (3).

Within medical education, MP is a core component as highlights the importance of cultivating professionalism at three distinct levels: individual (i.e., empathy, decision making, and accountability); institutional (i.e., commitment to integrating professionalism into clinical placement); and societal level (i.e., patient care and public trust in the healthcare systems) (7). In recent years, medical schools strive to formalize and standardize this aspect of the curriculum provided to undergraduate medical students (UMS) (7). Traditionally, MP was learned implicitly through role modelling and clinical exposure at a postgraduate level (8). However, recent educational approaches advocate for explicit teaching, assessment, and reflection on professionalism to better prepare students for the complex professional dilemmas and challenges of clinical practice, these can include individual burnouts, cultural resistance/systematic pressure and societal signification of patient-centred care (9–12). This shift requires continuous improvement of curricula, including the integration of feedback mechanisms that allow students to reflect on and enhance their ethical conduct over time. Nevertheless, challenges persist, particularly due to the variability in how professionalism is defined across institutions and cultural contexts. This inconsistency creates obstacles to developing standardized curricula and objective assessment tools (10). Moreover, there is no clear consensus on which educational strategies are most effective for MP, especially in diverse, multicultural environments (13).

While these challenges remain, recent systematic reviews underscore the effectiveness of multifaceted interventions that blend theoretical knowledge (i.e., theory of constructivism, theory of planned behaviour, and social learning theory) with practical experiences (i.e., experiential learning) while also recognizing the critical influence of the learning environment on the development of PB and professional identity formation (14, 15). Despite these promising interventions, the literature remains limited regarding the long-term sustainability of these efforts aimed at fostering professionalism (16, 17). Many existing studies lack rigorous methodological designs and comprehensive evaluations of long-term outcomes (2). This lack of longitudinal data raises concerns about whether early gains in professionalism are sustained throughout the clinical years of medical training, where PB are particularly critical.

Educational interventions and efforts help ensure that MP teaching is not only relevant but also impactful (18, 19). However, to fully optimize these efforts, it is crucial to understand which approaches are most effective and sustainable. Thus, this review seeks to address the existing gaps by systematically evaluating the effectiveness of various professionalism education interventions. In particular, it will assess their impact on teaching methods, PB development, and the long-term sustainability of these interventions among medical students. By doing so, the review may provide clearer guidance on which methods lead to enduring improvements in MP.

This systematic review, also known as an umbrella review (systematic review of systematic reviews) was conducted to systematically summarize the published systematic reviews in this area (20). The reporting was in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (21). The protocol of this systematic review was prepared using PRIMSA-Protocol statement and registered on PROSPERO [CRD42024495689]. The PICO framework guiding this review is as follows:

• Population: Undergraduate medical students (preclinical and clinical).

• Interventions: Educational interventions designed to foster at least one attribute of MP (e.g., reflective practice, peer feedback, portfolios).

• Comparisons: Studies with and without comparator.

• Outcomes: all reported outcomes were included.

Eight major data bases were systematically searched (CINAHL, EMBASE, ERIC, Health business, Medline OVID, PsycINFO, SCOPUS and Web of Science) and grey literature from inception of data base to June 2024 to identify relevant systematic reviews. The search terms included the keywords “Medical professionalism” “humanism” “Professional behaviour” “undergraduate medical students” “educational interventions” and their appropriate synonyms to the title/abstract/keywords fields. The search was restricted to English language and where applicable, the search was either filtered to “systematic review” methodology or this was added to the search string. The search strategy was developed with the information specialist from the library in the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

All retrieved references were exported to Endnote 20 ®; duplicates were removed, and then imported into COVIDENCE.org, where duplicates were automatically repeated. Two reviewers independently screened references for title and abstract then for full text screening. Any conflicts between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. The same strategy was conducted for data extraction and quality assessment.

A data extraction form was developed with a team of expert researchers in systematic reviews and the topic of MP. The data extracted include characteristics of (i) systematic review (i.e., first author, publication year, aim, search date and number and type of study included); (ii) interventions included (type, duration, frequency, follow up, mode of delivery, themes of MP targeted); (iii) participants (number, undergraduate level/year, comparator characteristics); (iv) outcomes assessed; (v) key finding; and (vi) conclusion and suggestions.

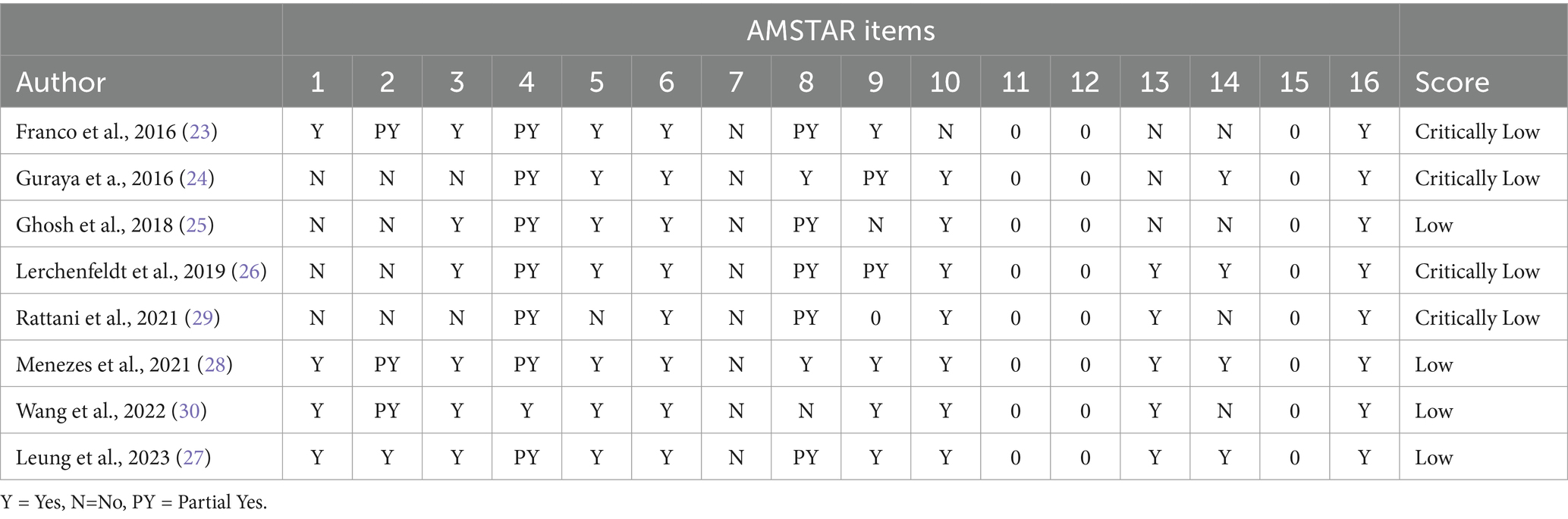

The methodological quality of systematic reviews included was assessed using the A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) 2 tool (22) which includes a checklist of 16 criteria that critically appraises if the study had followed a comprehensive systematic protocol, bias and validity of conclusions. Two independent reviewers provide “yes,” “no,” or “partial Yes” voting for each of the 16 criteria. The final AMSTAR 2 scoring was automatically categorised as critically low, low, moderate and high quality using the online ASMTAR calculator available online on https://amstar.ca/Amstar_Checklist.php.

A narrative summary of included systematic review was conducted s as all included reviews reported qualitative findings rather than a statistical analysis. Thus, meta-analysis of included reviews was not applicable.

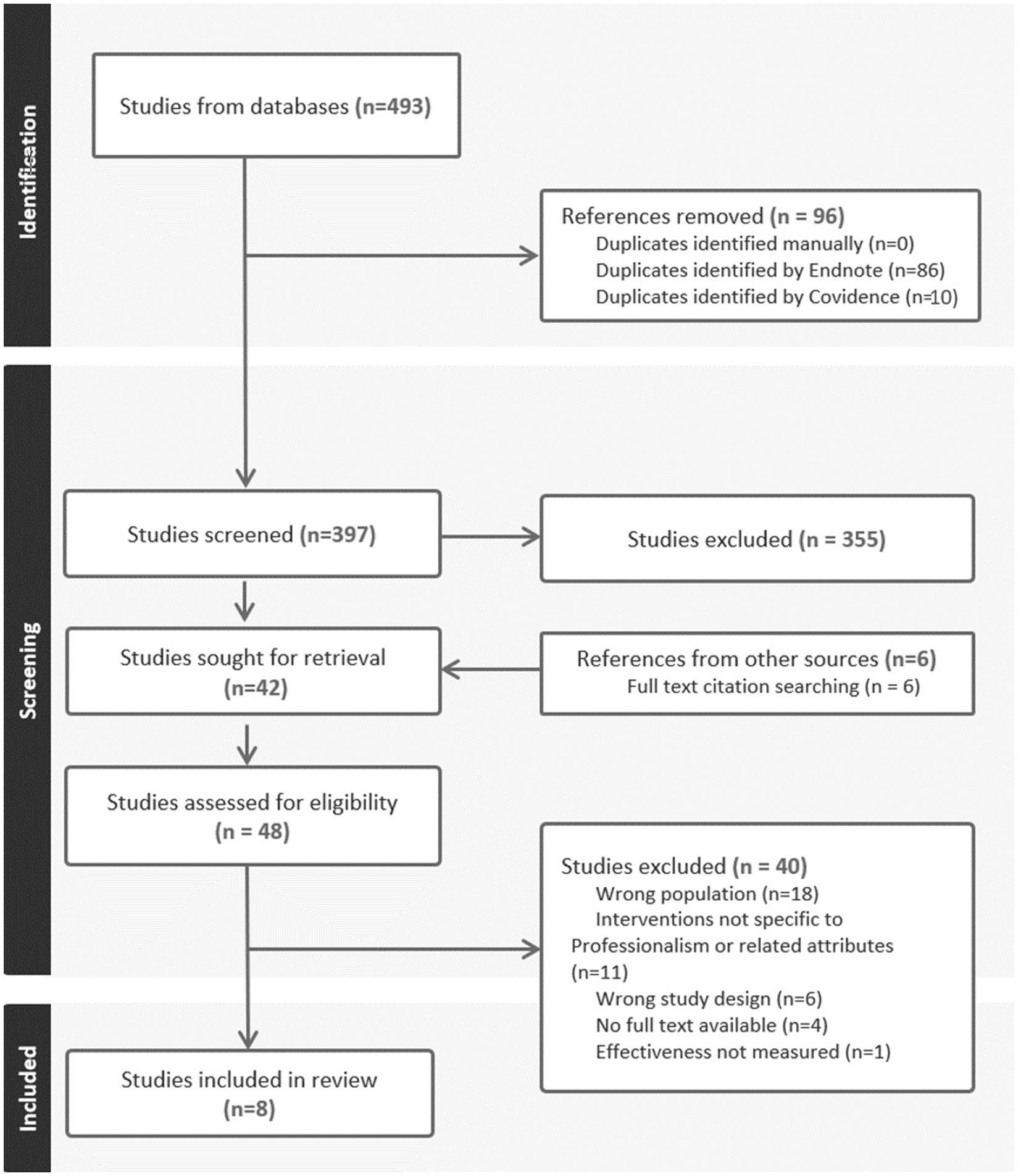

The search identified 397 references for title and abstract screening after the removal of duplicated (n = 96) (Figure 1). A total w48 full text studies were screened for eligibility, and 40 references did not meet the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, eight systematic reviews were eligible for inclusion (23–30).

Figure 1. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flowchart (21).

The eight included systematic review were published between 2011 and 2023 with an overall search duration from the inception of databases until 2022. These systematic reviews included a total of 367 studies. A total of 117,875 UMS at both preclinical and clinical level of education are included in the retrieved studies, except for one study which targeted only students during the preclinical stage only (25). The included studies displayed significant methodological heterogeneity, with varying study designs (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method approaches) and differing methodologies for assessing outcomes. A detailed description of included studies and participants is provided in Table 1.

As described in Table 2, included studies involved education interventions that (i) were either provided either in-person (25, 26, 29) or using both in-person and an online platform (23, 24, 27, 28) (ii) were either embedded within the curriculum or provided as a separate session/workshop, as reported by seven SRs (23–29); (iii) ranged from single sessions to multiple sessions, as reported by five references (23, 25, 27–29); (iv) had a duration from 0.5 to 150 min, as reported by two references (28, 29); and (v) either compared with standard teaching, did not have a comparator group, or compared two teaching methods, as reported by five references (26–30). There was considerable heterogeneity in the interventions used across the studies, which ranged from reflective practices to peer feedback and audiovisual tools. This variability limits the direct comparability of results.

The included systematic reviews were evaluated for methodological quality using AMSTAR 2 tool. The methodological quality across studies varied, with the majority scoring between low (n = 4) (25, 27, 28, 30) and critically low (n = 4) (23, 24, 26, 29); mainly due to lacking rigorous methodological designs, particularly in terms of bias assessment and reporting transparency (Table 3).

Table 3. Methodological quality assessment of reviews using A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) 2 scoring (22).

Included reviews measured the effectiveness of educational interventions on two major topics: (i) MP as a whole (n = 4) (23, 24, 26, 29); (ii) specified empathy and compassion (n = 4) (25, 27, 28, 30); Leung et al. review have examined both topics and are discussed in both sections (27).

Four systematic reviews reported the effectiveness of educational interventions of MP as a whole (23, 24, 26, 29). These educational interventions were delivered through various models and techniques. For instance, reflective practice (23, 24, 27), role modelling (24), audio-visual media (29), and collective peer feedback (23, 26). Due to the narrative nature of these reviews and the diversity of interventions, direct comparisons of effectiveness across studies were not feasible. However, certain trends emerged, with reflective practice and peer feedback standing out as particularly effective in fostering PB. Guraya et al.’ review systematically reported on the teaching strategies and their effectiveness in fostering MP and ability to analyse scenarios (i.e., identifying and analysing unprofessional behaviour) in UMS (24). The reviewers also identified multiple delivery modes of MP’s pillars, these include group-based discussion lectures, simulations, virtual reviews, preclinical teaching and experiential learning during clinical placement (24). Nevertheless, they concluded that the discussed heterogeneity suggests the absence of an evidence base to a consolidated approach in MP teaching (24).

Leung et al. review explored and discussed a structured reflective practice as a promising aspect to develop MP education and bridge the gap between theory and practice when delivered successfully (27). They concluded that future intervention should be further tested to validate successful provision of reflective practice (27).

Lerchenfedlt et al. assessed the effectiveness of ‘peer feedback’ during collective MP learning and denoted the likely value in improving MP and PB in UMS (26). The authors suggested (i) a standardized agreement on the definition of collective peer feedback and its assessment methods and (ii) added that future research could further explore this area, specifying assessments on the quality of these interventions on faculty and patients’ outcomes (26).

Rattani et al. (29) concluded that the use of trigger films in any MP teaching environment can improve engagement and fruitful discussions between UMS, especially in the current digital era. Trigger films, as explained by authors, characterised verbal conversations, non-verbal communication, reflective practice and inclusion of variety of different topics (29). The reviewers have suggested that trigger films should be relevant to scenarios experienced by medical students in clinical training (29).

Franco et al. (23) reported the use of portfolio as an effective tool in in reflective practice. Portfolios are reported to include an electronic ‘peer feedback’ discussion, defined in the review as either an assessment tool or a teaching approach, in which either have shown improvement in altruism as an attribute of MP (23). The authors discussed some degree of complexity that can contribute to failure of this approach, these include the timely process, lack of interest in some students and the use of scenarios irrelevant to practice (23). While these challenges exist, they suggested a framework to a support successful utility of portfolios that can adapted by researchers and educators (23).

As detailed in Table 4, four studies have systematically reported on the effectiveness of educational interventions on empathy and compassion (25, 27, 28, 30). The interventions varied widely, including reflective practice, virtual discussions, and group-based sessions, with mixed results depending on the context and delivery of the interventions. In three reviews, teaching techniques such as reflective practice, virtual discussions of donors, and in-person simulation, and group-based discussions have shown improvements in developing empathy and compassion in UMS (25, 27, 30). The majority of included interventions varied in outcomes and their assessment methods as detailed in Table 4. Authors have emphasized the importance of longitudinal exposure to the hidden curriculum by UMS at all levels of their education, from early exposure during their clinical placement stage (25, 27, 30).

Menezes et al.’s (28) review identified various teaching programmes designed and resulted in improvement in empathy and compassion in UMS. While a comparison in the effectiveness between the different teaching programmes was not achievable, the review has highlighted the need for a longitudinal curriculum agenda that can potentially include a blended programme, focusing on interprofessional practice and professional identity formation (28).

Leung et al.’s (27) review—the most recent included review—on the other hand, identified collective reflective practice in UMS as a promising approach to enhance and retain empathy and compassion, when exercised voluntarily. Similar to the majority of included reviews in our study, the authors included interventions provided to students at both pre and during clinical placement stage. Nonetheless, Leung et al. (27) highlighted the importance of the consistent learning during clinical placements and suggested that future research should examine the quality of MP teaching evaluation methods to maintain PB. The reviewer also assessed the effectiveness of wellbeing and reported that the lack of literature to provide evidence suggests that future research can explore the influence of collective reflective practice on the wellbeing of UMS (27).

Wang et al. (24) reported on the predictors of empathy and compassion, focusing on personal factors (e.g., cultural background, education level) and environmental factors (e.g., the educational culture and role modelling). While personal factors had inconsistent effects, environmental factors, particularly positive role modelling, were found to have a critical impact on developing empathy and compassion in medical students (30).

Ghosh et al. (25) focused on examining formation of MP and empathy in UMS using recorded video interviews of donors and meeting the donors’ family members in dissection anatomy courses. The review reported a noted improvement in empathy and compassion as a result of the hidden curriculum exposure using patient factors and authors discussed the importance of this approach on MP education and development of professionalism in practice (25).

Six included reviews have reported details on the potential sustainability of MP education from included interventions and was dependent of specific implementation strategies used in each study. Leung et al. and Ghosh et al. have reported that collective reflective practice and digital clips of donors in dissection anatomy can foster PB and MP traits (25, 27). The authors have discussed the importance of linear exposure to hidden curriculum not only during the preclinical stage but also during their clinical training to support experiential learning and prolong positive development (25, 27). Ghosh et al. concluded on the promising impact of interventions included in preserving empathy and compassion (25).

Menezes et al. have emphasized the importance of the sustainability of MP teaching and learning provided to UMS as it can potentially support professionalism in practice (28). Franco et al. discussed challenges to achieving effective results and suggested that evaluation of the impact of teaching tools can support their term effects (23). Wang et al. informed the limited literature on the long-term effect of factors that influence PB in medical students and suggested further investigation from future research in this area (30). Lerchenfeldt et al. review did not report on long-term effect of included MP educational interventions, but concluded that future studies should further develop interventions and study benefits to professionalism in practice (26).

Overall, there is limited data on the long-term sustainability of professionalism education, with few studies evaluating the lasting impact of these interventions. This highlights a gap regarding the durability of professionalism education outcomes.

This review included an overview of SRs of interventions published in the last three decades including over 100 thousand UMS. These SRs included various study types that narratively assessed interventions of a wide range of teaching modalities aimed at improving MP as a whole and empathy and compassion. While some SR reported a degree of success in teaching techniques, there remains limited evidence on a standardized approach to MP education in UMS. All included systematic reviews presented a low-quality score and limited results were identified to provide evidence on the long-term impact of MP educational interventions.

While MP education is vital to UMS, published interventions in this area to date are limited in evaluating and developing MP in research (31). The limitation can stem from challenges given the inconsistent definition of MP education’s and its uniformly across different contexts (32). In other words, aspects of MP, their interpretation and application can vary widely among individuals and institutions (33). This review adds to the body of evidence on significant challenge that is the lack of standardized, objective tools for measuring professionalism (2). Passi et al. explain that the nature of MP education in different contexts are often prone to bias and subjectivity, complicating efforts to produce developing curriculum on professionalism (18). Moreover, Mueller et al. adds the complications in designing a universal framework due to personal and cultural factors (34). Similar interpretations can be drawn from our review to reflect on the importance of the cultural sensitivity influence on the formation of an effective curriculum to developing PB in UMS. These complexities hinder the creation of a clear, evidence-based framework for research on professionalism. Thus, this review suggests that establishing the taxonomy of MP definition and learning outcomes is essential to support the development of a standardised/innovative assessment of MP educational syllabus, accommodating its dynamic and context-dependent nature. This suggestion is similar to a systematic review conducted by Al Rumayyan et al. on the differences between MP frameworks across multiple geographic regions (35).

Included SRs includes UMS at the preclinical and clinical stages of their educations. While results did not allow our review to draw comparisons between the two stages, it is important to acknowledge the growing research reporting the fundamental impact on their PB. On one hand, evolving interventions are focused on students on their preclinical stage for the benefits of developing PB and preparation for unprofessional dilemmas through critical learning and reflections (15, 36, 37). On the other hand, other interventions aim at targeting students in their later stage with focus on experiential learning (38, 39). These interventions are based on a theoretical perspective of behaviour and learning (40, 41) given their significance in explaining what works and does not work in an intervention. Additionally, the use of theory benefits the feedback loop in learning and bridging gaps between theory and practice (38, 41). This review suggests that future research should focus on a longitudinal curriculum design for different stages of learning that is based on a theoretical perspective and is needed to tackle gaps in professionalism in practice.

To date, there is limited evidence on the sustainability of MP educational interventions. Carr et al. suggests the complexity in designing interventions aimed at exploring long term impact on outcomes (42). This review could not report of barriers and facilitators to studying the long-term impact of educational interventions included within SRs. Thus, the review highlights the ambiguity in literature reporting in this area. Furthermore, a wealth of research had been conducted towards the importance of extended learning of professionalism at the postgraduate level to further sustain PB and patient safety (43–45). This has emerged from the reported evidence of the declining in professionalism traits as part of the professional identity formation in residents and healthcare professionals (46). Ultimately, fostering professionalism at the postgraduate level is crucial for ensuring that healthcare professionals are equipped not only with technical expertise but also the ethical and interpersonal skills needed for professional and humanistic patient care. More research, particularly longitudinal randomised controlled trials are needed to understand the evolution of professionalism education at the undergraduate level and if postgraduate education is essential for the sustainability of PB.

The potential always exists in reviewing extensive literature that important studies may have been missed either during the screening of SR published in English language and/or using systematic reviews as the unit of analysis not the original interventions. Secondly, while the search strategy was developed with a team of experts and subject librarian in the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, some keywords used to describe either MP or educational interventions, given the discussed inconsistent definitions of MP, could have omitted. Lastly, it is important to acknowledge that all included reviews exhibit a low methodological quality which consequently have a minor impact on conclusions drawn from this umbrella review.

The majority of included reviews have reported a successful improvement in various aspects of MP (i.e., MP as a whole, empathy and compassion) through teaching and exposure to hidden curriculum in UMS. A gap is still present in reporting the sustainable effect on professionalism traits in UMS and on suggesting a standardised approach to professionalism teaching and improvement in professionalism in practice. This review suggests that (1) future research should be towards a systematic review of methodological quality to support rigour interpretation; and (2) more educational interventions are needed in this area, with the focus on teaching methods in multicultural context to support professional identity formation and precursors of PB.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

AS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ShG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BF: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EC: Conceptualization, Project administration, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FD: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. GK: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FG: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MH: Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation. SaG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. DH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the North–South Research Programme from The Higher Education Authority (HEA) in Ireland, granted to the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (Grant number: 21578A01).

The authors wishes to acknowledge the administrator in RCSI Health Profession Education Centre, Mary Smith; Information specialist in RCSI library, Killian Walsh; and digital media specialist in RCSI, Sinead Hand for the overall support in the umbrella review.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Blank, L, Kimball, H, McDonald, W, and Merino, JABIM Foundation AF, * EFoIM. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: A physician charter 15 months later. Am College Phys. (2003) 138:839–41. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-10-200305200-00012

2. Li, H, Ding, N, Zhang, Y, Liu, Y, and Wen, D. Assessing medical professionalism: a systematic review of instruments and their measurement properties. PLoS One. (2017) 12:e0177321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177321

3. Guraya, SS, Guraya, SY, Rashid-Doubell, F, Fredericks, S, Harkin, DW, Nor, MZ, et al. Reclaiming the concept of professionalism in the digital context; a principle-based concept analysis. Annals Med. (2024) 56:2398202.

4. Cunningham, M, Hickey, A, Murphy, P, Collins, M, Harkin, D, Hill, ADK, et al. The assessment of personal and professional identity development in an undergraduate medical curriculum: a scoping review protocol. HRB Open Res. (2022) 5:62. doi: 10.12688/hrbopenres.13596.1

5. Wynia, MK, Papadakis, MA, Sullivan, WM, and Hafferty, FW. More than a list of values and desired behaviors: a foundational understanding of medical professionalism. Acad Med. (2014) 89:712–4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000212

6. Hodges, BD, Ginsburg, S, Cruess, R, Cruess, S, Delport, R, Hafferty, F, et al. Assessment of professionalism: recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 conference. Med Teach. (2011) 33:354–63. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.577300

7. Forouzadeh, M, Kiani, M, and Bazmi, S. Professionalism and its role in the formation of medical professional identity. Med J Islam Repub Iran. (2018) 32:765–8. doi: 10.14196/mjiri.32.130

8. Cruess, R, McIlroy, JH, Cruess, S, Ginsburg, S, and Steinert, Y. The professionalism Mini-evaluation exercise: a preliminary investigation. Acad Med. (2006) 81:S74–8. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200610001-00019

9. Cruess, SR, Cruess, RL, and Steinert, Y. Supporting the development of a professional identity: general principles. Med Teach. (2019) 41:641–9. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1536260

10. Mid Staffordshire, N. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS foundation trust public inquiry. The Stationery Office Limited. United Kingdom, (2013). Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7ba0faed915d13110607c8/0947.pdf

11. Goldstein, EA, Maestas, RR, Fryer-Edwards, K, Wenrich, MD, Oelschlager, A-MA, Baernstein, A, et al. Professionalism in medical education: an institutional challenge. Acad Med. (2006) 81:871–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000238199.37217.68

12. Yancy, CW, Jessup, M, Bozkurt, B, Butler, J, Casey, DE, Drazner, MH, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2013) 62:e147–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019

13. Jha, V, Bekker, HL, Duffy, SR, and Roberts, TE. Perceptions of professionalism in medicine: a qualitative study. Med Educ. (2006) 40:1027–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02567.x

14. O'Sullivan, H, van Mook, W, Fewtrell, R, and Wass, V. Integrating professionalism into the curriculum: AMEE guide no. 61. Med Teach. (2012) 34:e64–77. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.655610

15. Guraya, SS, Clarke, E, Sadeq, A, Smith, M, Hand, S, Doyle, F, et al. Validating a theory of planned behavior questionnaire for assessing changes in professional behaviors of medical students. Front Med. Annals of Medicine. (2024) 11:1382903. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1382903

16. Rich, A, Medisauskaite, A, Potts, HWW, and Griffin, A. A theory-based study of doctors’ intentions to engage in professional behaviours. BMC Med Educ. (2020) 20:44. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-1961-8

17. Stern, DT, Frohna, AZ, and Gruppen, LD. The prediction of professional behaviour. Med Educ. (2005) 39:75–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02035.x

18. Passi, V, Doug, M, Peile, E, Thistlethwaite, J, and Johnson, N. Developing medical professionalism in future doctors: a systematic review. Int J Med Educ. (2010) 1:19–29. doi: 10.5116/ijme.4bda.ca2a

19. Ong, YT, Kow, CS, Teo, YH, Tan, LHE, Abdurrahman, ABHM, Quek, NWS, et al. Nurturing professionalism in medical schools. A systematic scoping review of training curricula between 1990–2019. Med Teach. (2020) 42:636–49. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1724921

20. Aromataris, E, Fernandez, R, Godfrey, CM, Holly, C, Khalil, H, and Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. JBI Evid Implement. (2015) 13:132–40. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055

21. Moher, D, Liberati, A, Tetzlaff, J, and Altman, DGGroup P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. (2010) 8:336–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007

22. Shea, BJ, Reeves, BC, Wells, G, Thuku, M, Hamel, C, Moran, J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. (2017) 358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008

23. Franco, RS, Franco, CAGS, Pestana, O, Severo, M, and Ferreira, MA. The use of portfolios to foster professionalism: attributes, outcomes, and recommendations. Assess Eval High Educ. (2016) 42:737–55. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2016.1186149

24. Guraya, SY, Guraya, SS, and Almaramhy, HH. The legacy of teaching medical professionalism for promoting professional practice: a systematic review. Biomed Pharmacol J. (2016) 9:809–17. doi: 10.13005/bpj/1007

25. Kumar Ghosh, S, and Kumar, A. Building professionalism in human dissection room as a component of hidden curriculum delivery: a systematic review of good practices. Anat Sci Educ. (2019) 12:210–21. doi: 10.1002/ase.1836

26. Lerchenfeldt, S, Mi, M, and Eng, M. The utilization of peer feedback during collaborative learning in undergraduate medical education: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. (2019) 19:321–10. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1755-z

27. Leung, KC, and Peisah, C. A mixed-methods systematic review of group reflective practice in medical students. Healthcare (Basel). (2023) 11:1798. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11121798

28. Menezes, P, Guraya, SY, and Guraya, SS. A systematic review of educational interventions and their impact on empathy and compassion of undergraduate medical students. Front Med. (2021) 8:758377. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.758377

29. Rattani, A, Kaakour, D, Syed, RH, and Kaakour, A-H. Changing the channel on medical ethics education: systematic review and qualitative analysis of didactic-icebreakers in medical ethics and professionalism teaching. Monash Bioeth Rev. (2021) 39:125–40. doi: 10.1007/s40592-020-00120-2

30. Wang, CX, Pavlova, A, Boggiss, AL, O’Callaghan, A, and Consedine, NS. Predictors of medical students’ compassion and related constructs: a systematic review. Teach Learn Med. New York, NY: Oxford Academic. (2022) 35:502–13. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2022.2103816

31. Arnold, L, and Stern, DT. “What is medical professionalism?,” In: TS David editor. Measur Med Profes. (New York, NY: Oxford Academic) (2006) 15–37.

32. Goldie, J. Assessment of professionalism: a consolidation of current thinking. Med Teach. (2013) 35:e952–6. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.714888

33. Birden, H, Glass, N, Wilson, I, Harrison, M, Usherwood, T, and Nass, D. Defining professionalism in medical education: a systematic review. Med Teach. (2014) 36:47–61. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.850154

34. Mueller, PS. Incorporating professionalism into medical education: the Mayo Clinic experience. Keio J Med. (2009) 58:133–43. doi: 10.2302/kjm.58.133

35. Al-Rumayyan, A, Van Mook, WNKA, Magzoub, ME, Al-Eraky, MM, Ferwana, M, Khan, MA, et al. Medical professionalism frameworks across non-Western cultures: a narrative overview. Med Teach. (2017) 39:S8–S14. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1254740

36. Elliott, DD, May, W, Schaff, PB, Nyquist, JG, Trial, J, Reilly, JM, et al. Shaping professionalism in pre-clinical medical students: professionalism and the practice of medicine. Med Teach. (2009) 31:e295–302. doi: 10.1080/01421590902803088

37. Goldie, J, Dowie, A, Cotton, P, and Morrison, J. Teaching professionalism in the early years of a medical curriculum: a qualitative study. Med Educ. (2007) 41:610–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02772.x

38. Yoshimura, M, Saiki, T, Imafuku, R, Fujisaki, K, and Suzuki, Y. Experiential learning of overnight home care by medical trainees for professional development: an exploratory study. Int J Med Educ. (2020) 11:146–54. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5f01.c78f

39. Wong, BM, Etchells, EE, Kuper, A, Levinson, W, and Shojania, KG. Teaching quality improvement and patient safety to trainees: a systematic review. Acad Med. (2010) 85:1425–39. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e2d0c6

40. Shapiro, J. Perspective: does medical education promote professional alexithymia? A call for attending to the emotions of patients and self in medical training. Acad Med. (2011) 86:326–32. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182088833

41. Michie, S, van Stralen, MM, and West, R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. (2011) 6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

42. Carr, SE, Noya, F, Phillips, B, Harris, A, Scott, K, Hooker, C, et al. Health humanities curriculum and evaluation in health professions education: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. (2021) 21:568. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-03002-1

43. de Groot, JM, Kassam, A, Swystun, D, and Topps, M. Residents’ transformational changes through self-regulated, experiential learning for professionalism. Canadian Med Educ J. (2022) 13:5–16. doi: 10.36834/cmej.70234

44. Yardley, S, Teunissen, PW, and Dornan, T. Experiential learning: AMEE guide no. 63. Med Teach. (2012) 34:e102–15. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.650741

45. Logar, T, Le, P, Harrison, JD, and Glass, M. Teaching corner: “first do no harm”: teaching global health ethics to medical trainees through experiential learning. J Bioethical Inquiry. (2015) 12:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s11673-014-9603-7

Keywords: medical professionalism, medical professionalism education, professional behaviour, systematic review, sustainability, professional identity formation

Citation: Sadeq A, Guraya SS, Fahey B, Clarke E, Bensaaud A, Doyle F, Kearney GP, Gough F, Harbinson M, Guraya SY and Harkin DW (2025) Medical professionalism education: a systematic review of interventions, outcomes, and sustainability. Front. Med. 12:1522411. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1522411

Received: 04 November 2024; Accepted: 18 February 2025;

Published: 03 March 2025.

Edited by:

Kate Owen, University of Warwick, United KingdomReviewed by:

Rabia S. Allari, Al-Ahliyya Amman University, JordanCopyright © 2025 Sadeq, Guraya, Fahey, Clarke, Bensaaud, Doyle, Kearney, Gough, Harbinson, Guraya and Harkin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Asil Sadeq, YXNpbHNhZGVxQHJjc2kuaWU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.