- Department of Translational Biomedicine and Neuroscience, University of Bari Medical School, Bari, Italy

The tumor microenvironment comprises diverse cell types, including T and B lymphocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, natural killer cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, mast cells, and fibroblasts. Cells in the tumor microenvironment can be either tumor-suppressive or tumor-supporting cells. In this review article, we analyze the double role played by tumor macrophages, tumor neutrophils, tumor mast cells, and tumor fibroblasts, in promoting angiogenesis during tumor progression. Different strategies to target the tumor microenvironment have been developed in this context, including the depletion of tumor-supporting cells, or their “re-education” as tumor-suppressor cells.

Introduction

Tumor cells undergo a Darwinian selection and can survive and enter an equilibrium state where the innate and adaptive immune system controls the tumor (1, 2). Some tumor cells acquire mutations, chromosome amplifications and deletions, and epigenetic modifications, resulting in gene silencing or synthesis of abnormal proteins. Overall, these events allow tumor cells to escape the control of the immune system, increase, and give rise to a clinically detectable tumor.

The link between chronic inflammation and tumorigenesis was first proposed by Rudolf Virchow in 1863 after the observation that infiltrating leukocytes are a hallmark of tumors and first established a causative connection between the lymphoreticular infiltrate at sites of chronic inflammation and the development of cancer (3). Dvorak described tumors as wounds that never heal (4). Under a variety of inflammatory conditions, both innate and adaptive immune cells are capable of polarization into their “tumoricidal” (growth arresting) or “tumorigenic” (growth promoting) forms. The tumor microenvironment comprises diverse cell types, including T and B lymphocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, natural killer cells, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, mast cells, and fibroblasts. Cells in the tumor microenvironment can be either tumor-suppressive or tumor-supporting cells. Different strategies to target the tumor microenvironment have been developed in this context, including the depletion of tumor-supporting cells, or their “re-education” as tumor-suppressor cells. In this review article, we analyze the double role played by tumor macrophages, neutrophils, mast cells, and fibroblasts, in promoting angiogenesis during tumor progression.

Macrophages

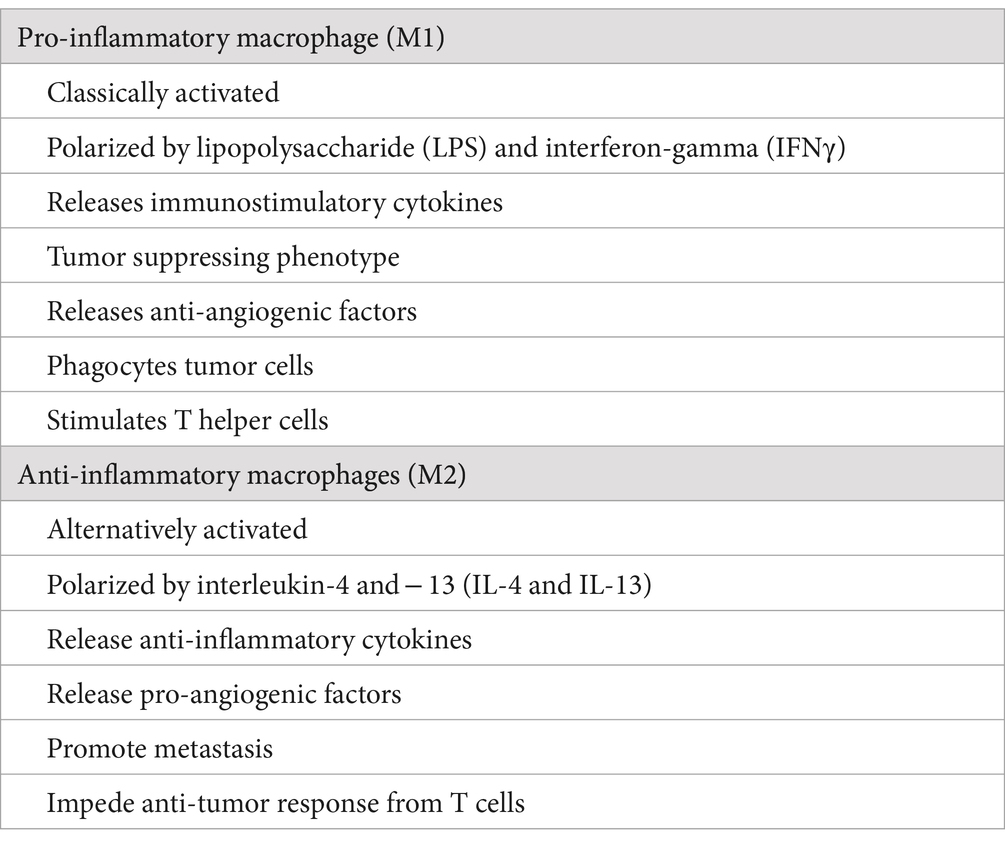

Two different macrophage subpopulations have been described: classically activated or inflammatory macrophages (M1) and alternatively activated or anti-inflammatory macrophages (M2) (Table 1). M2 macrophages can be divided into four subsets consisting of M2a, M2b, M2c, and M2d, based on the stimuli used to derive them in tissue culture experiments (5). M1 macrophages are induced by interferon-gamma (IFNγ), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and secrete different pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, interleukin 1 alpha, beta, 6, 12, 23 (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23), cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), whereas M2 macrophages are induced by IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, IL-21, IL-33, activin A, corticosteroids, prostaglandins (PGs), and vitamin D3 (6).

Macrophages are the most represented immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) include tissue-resident macrophages (TRMs) and a large proportion of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs). TRMs derive from CX3CR1+ Kit+ erythromyeloid progenitors, while BMDMs originate from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. TRMs, including alveolar macrophages in the lung, brain microglia, and Kupffer cells in the liver, develop in the embryonic yolk sac and fetal liver, self-maintain throughout adulthood, and are involved in tissue homeostasis and integrity (7). BMDMs derive from circulating monocytes that exit the bloodstream and undergo differentiation into macrophages within different tissues. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) secreted by activated fibroblasts, endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, monocytes, and T cells, triggers chemotaxis and migration of monocytes by interacting with the CC chemokine receptor 2 (CCR-2) on monocytes (8). TRMs and BMDMs are involved in forming a pre-metastatic niche, facilitating cancer engraftment at the metastatic sites (9).

TAM infiltration correlates with angiogenesis, poor prognosis, tumor progression, and metastasis in different tumors, including ovarian and breast cancer, follicular B lymphoma, soft tissue sarcoma, classic Hodgkin lymphoma, melanoma, glioma, squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, and bladder and prostate carcinoma. Increased TAMs are associated with poor prognosis and therapeutic resistance (9, 10). Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis has demonstrated the co-existence of multiple subsets of TAMs in individual tumors, showing that TAMs simultaneously co-express M1 and M2 marker genes (11). TAMs with M1 phenotype suppress tumor formation through direct phagocytosis of tumor cells, the induction of T cell-mediated cell cytotoxicity, and the stimulation of antibody-mediated immune response.

TAMs generally display an M2-like phenotype (12). In the initial stage of cancer, TAMs exert an immunostimulant function. In contrast, at later stages, they acquire an M2 phenotype, exerting a tumor-promoting function, promoting angiogenesis, repairing and remodeling wounded or damaged tissues, and suppressing adaptive immunity (12, 13). M2 TAMs produce immune-suppressive cytokines, including PGE2, IL-10, and transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) (14). They can also suppress dendritic cell differentiation and inhibit their functions through IL-10 production. The accumulation of M2 TAMs is linked to a poor prognosis in human cancers. The phenotype of polarized M1-M2 TAMs may be reversed (15), and a continuum exists between the two phenotypes (16). Negative regulation of CD47 and its ligand signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) can restore TAM phagocytic capacity (17).

TAMs are generally localized in the hypoxic areas of tumors, where they express hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF1α) that, in turn, induces the transcription of the angiogenic factors vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2), and platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) (18). TAMs regulate the angiogenic switch in a mouse model of breast cancer (19). VEGF restores delayed tumor progression in tumors depleted of macrophages (20). Pharmacological depletion of TAMs results in an inhibition of angiogenesis in tumors (12). TAMS express a broad array of angiogenesis-modulating enzymes, including matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, −7, −9, −12, and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (21–23).

Radiotherapy or chemotherapy increases the number of M2 TAMs favoring tumor recurrence (24, 25). Therapeutic strategies to reduce TAMs pro-tumoral activities include reduced monocyte recruitment, promotion of macrophage phagocytosis, and induction of M2 macrophage reprogramming, which may be obtained with different strategies including receptor tyrosine kinase RON inhibitors, angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) receptor inhibitors, histone acetyl deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors, PI3kδ inhibitors, miRNA inhibitors, CD40 agonists, Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, and macrophage receptors with collagenous structure (MARCO) neutralization antibodies.

The primary population of pro-angiogenic TAMs corresponds to TIE-2 expressing monocytes (TEMs), which secrete VEGF and MMP-9 (26). Most of the circulating TEMs do not express endothelial cell/endothelial precursor cells markers, such as VEGFR-2, AC133, CD146, and CD34, whereas they express hematopoietic markers, such as CD45. Moreover, circulating human TEMs do not express CCR-2, the receptor for MCP-1, a chemokine that regulates the recruitment of monocytes to inflamed tissues and tumors. TEMs might be attracted to tumors in a CCR-2-independent manner, by signals produced by tumor cells, stromal cells, or endothelial cells. TEM knockout prevents human glioma neovascularization in a mouse model and induces tumor regression (26). Ang-2 (a TIE-2 ligand) blockade abrogates TIE-2 expression and inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by impairing angiogenesis (27). TEMs do not differentiate into endothelial cells, suggesting that their pro-angiogenic activity could consist of a paracrine stimulation of angiogenesis. TEMs are localized both in perivascular and avascular viable (hypoxic) areas of tumors and are absent in non-neoplastic tissues adjacent to tumors (28). Exposure to both hypoxia and Ang-2 markedly suppressed the release of an anti-angiogenic IL-12 (29).

The selective elimination of TEMs using a suicide gene impaired angiogenesis in mouse tumors and induced substantial tumor regression and TEM elimination does not affect the overall number of TAMs and granulocytes, indicating that TEMs represent a distinct monocyte subset with specific pro-angiogenic activity (26, 29).

Neutrophils

Neutrophils are the most abundant circulating leukocytes, constituting a significant component of infiltrated immune and inflammatory cells in the tumor microenvironment. Besides their recruitment to primary tumors, neutrophils accumulate in the blood and distant organs of tumor-bearing hosts. Tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) are polarized in anti-tumor (N1) or pro-tumor (N2) phenotypes. N1 TANs are short-living, highly cytotoxic, and highly immune-stimulating. They recruit and activate immune cells by producing cytokines, chemokines, and proteases able to stimulate T cell proliferation, NK, and dendritic cell maturation (30, 31). N2 TANs are long-living, low-cytotoxic, with high pro-angiogenic, pro-metastatic, and immunosuppressive activities (32, 33). In mouse tumor models, TANs assume N1 or N2 phenotype and function, according to different tumor progression times. TGFβ stimulates N2 and inhibits N1 polarization, whereas inhibition of TGFβ results in a shift to the N1 phenotype (32). N2 TANs release different angiogenic factors, such as VEGF, IL-8, TNF-α, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and MMPs (34–36). Microarray analysis has demonstrated about thirty angiogenesis-relevant genes in human neutrophils (37). Neutrophil contribution to pathological angiogenesis may be sustained by an autocrine amplification mechanism.

VEGF release occurs at sites of neutrophil accumulation. Production and release of VEGF from neutrophils depend on granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) (38). Moreover, neutrophil-derived VEGF can stimulate neutrophil migration (39).

Mast cells

Mast cells are well known for their role in allergies and autoimmunity, but they can also infiltrate tumors, where exert both pro- and anti-tumorigenic activities depending on their microenvironmental stimuli. Mast cells attracted in the tumor microenvironment by stem cell factor (SCF) secreted by tumor cells produce several angiogenic factors as well as MMPs, which promote tumor vascularization and invasiveness, respectively (40). H1 receptor antagonists significantly improved overall survival rates and suppressed tumor growth as well as the infiltration of mast cells and VEGF levels through the inhibition of HIF-1α expression in B16F10 melanoma-bearing mice (41). Mast cells exert immunosuppression releasing TNF-α and IL-10 and stimulating immune tolerance and tumor promotion (42, 43). Mast cells may promote inflammation, inhibition of tumor cell growth, and tumor cell apoptosis by releasing cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, monocyte chemotactic protein-3 and -4 (MCP-3 and MCP-4), TGF-β, and chymase. Chondroitin sulfate inhibits tumor cell diffusion and tryptase causes tumor cell disruption and inflammation through the activation of protease-activated receptors (PAR-1 and -2) (44).

Mast cells store in their secretory granules pre-formed active serine proteases, including tryptase and chymase (45). Tryptase stimulates the proliferation of endothelial cells, promotes vascular tube formation in vitro, degrades connective tissue matrix, and activates MMPs and plasminogen activator, which in turn degrade the extracellular matrix with consequent release of VEGF or FGF-2 from their matrix-bound state (46). Mast cells contain MMPs, and tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs), which intervene in regulation of extracellular matrix degradation, allowing the release of angiogenic factors. Mast cell-deficient W/Wv mice exhibit a decreased rate of tumor angiogenesis (47). Development of squamous cell carcinoma in a human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 infected transgenic mouse model of epithelial carcinogenesis provided experimental support for the early participation of mast cells in tumor growth and angiogenesis (48, 49). Mast cells infiltrated hyperplasia, dysplasias, and the invasive front of carcinomas, but not the core of tumors. Accumulation occurred proximal to developing capillaries and the stroma surrounding the advancing tumor mass (48). Infiltration of mast cells and activation of MMP-9 coincided with the angiogenic switch in premalignant lesions through the release of pro-angiogenic molecules from the extracellular matrix. Remarkably, premalignant angiogenesis was abrogated in a mast cell-deficient HPV 16 transgenic mouse indicating that neoplastic progression in this model involved infiltration of mast cells in the skin (48, 49). An increased number of mast cells have been demonstrated in angiogenesis associated with vascular tumors, like hemangioma and hemangioblastoma, as well as several hematological and solid tumors, including lymphomas, multiple myeloma myelodysplastic syndrome, B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, breast cancer, gastric and colon-rectal cancer, uterine cervix cancer, melanoma, and pulmonary adenocarcinoma, in which mast cell accumulation correlate with increased neovascularization, mast cell VEGF and FGF-2 expression, tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis (40).

Fibroblasts

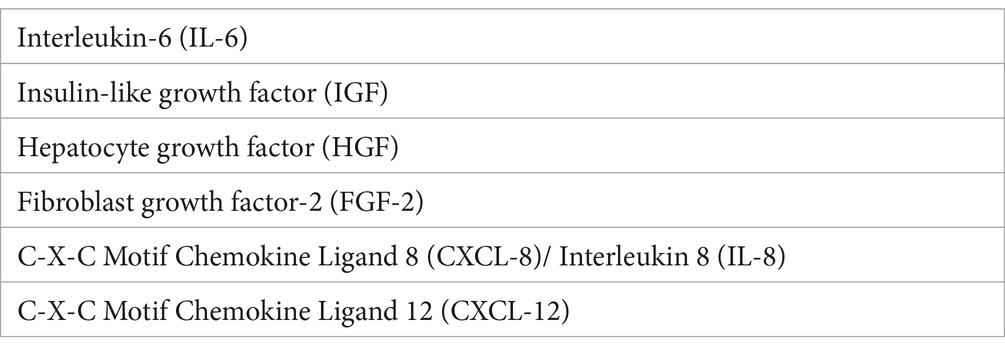

Fibroblasts are interconnected with tumor cells by promoting tumor growth, angiogenesis, and the metastatic process (50). Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are characterized by the expression of specific markers and secrete growth factors and angiogenic factors (Table 2). A source of CAFs is represented by the expansion of tissue-resident fibroblasts in the early stages of tumor progression (51, 52). CAFs may also originate from transdifferentiation of myofibroblasts, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells, stellate cells, and adipocytes (53–56). CAFs modulate tumor growth by secreting: (i) growth factors able to increase tumor cell proliferation and exert an anti-apoptotic activity; (ii) chemotactic factors recruiting other stromal cells, including leukocytes, monocytes/macrophages, and mast cells. CAFs have both pro-tumorigenic and anti-tumorigenic roles. CAFs (type 1 polarized fibroblasts) induce immunosuppression by an increase in Th2 cells, Th17 cells, and Tregs, and are also involved in therapy resistance (57). Co-injection of CAFs with tumor cells resulted in enhanced tumor formation (58). CAFs (type 2 polarized fibroblasts) exert a tumor-promoting function under the influence of growth factors and chemokines. They stimulate cancer cell survival, growth, and invasion, by secreting cytokines, exosomes, and growth factors, contribute to angiogenesis through the release of angiogenic cytokines, including VEGF, TGFβ, IL-6, and TNFα, and activate other immune cells (58). ScRNA-seq of precursor lesions of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PDCA) revealed dynamic changes in the composition of CAF subsets during tumor progression (59). The progression of premalignant Barrett’s esophagus to esophageal adenocarcinoma is characterized by increased inflammatory-related gene expression by fibroblasts (60).

Therapeutic strategies

VEGF/VEGF receptors (VEGFRs) inhibition represents the most widely used anti-angiogenic strategy, including anti-VEGF and anti-VEGFRs specific antibodies, VEGF decoy receptors (VEGF-TRAP), receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) inhibitors. An alternative anti-angiogenic strategy is the use of Ang2/Tie2 inhibitors.

Tumor microenvironment cells represent attractive therapeutic strategies (61). Different approaches have been developed to enhance TAMs anti-tumor immune activity, including TAM apoptosis by blocking CSF-1/CSF1-R signaling (62); CSF1-R inhibitors suppress macrophage differentiation toward the M2 phenotype and macrophage-related angiogenesis (63); inhibition of TAM recruitment to tumor microenvironment by blocking CCL2 of CCR2 axis, improving the prognosis (64); increase of TAM-mediated phagocytosis of cancer cells; blocking programmed cell death protein (PD-1)/ programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) signaling improve phagocytic activity of TAMs (65); reprogramming of TAMs by enhancing their antigen presentation to T cells via CD40 agonists, or by promoting their re-education to anti-tumoral phenotypes (66); Ang2/Tie2 signaling inhibits tumor growth by blocking angiogenesis signals and the immunosuppressive functions of TAMs (63).

Different studies have demonstrated the anti-cancer activity of CAFs, including inhibition of fibroblast activation protein, TGFβ inhibitors, or vitamin S analog Paricalcitol (50).

Strategies explored to inhibit neutrophils include the inhibition of CXC receptors like CXCR2 that are associated with the migration of neutrophils to tumor areas. CXCR1 and CXCR2 inhibitors are currently in clinical development in cancer. Inhibition of the IL-23 and IL-17 axis is another approach, as IL-17 and IL-23 stimulate the expansion of neutrophils mediated by G-CSF (67).

Mast cells might act as a new target for the adjuvant treatment of tumors through the selective inhibition of angiogenesis, tissue remodeling, and tumor-promoting molecules, allowing the secretion of cytotoxic cytokines, and preventing mast cell-mediated immune suppression. Pre-clinical studies using anti-c-kit antibodies, anti-TNF-α antibodies, or the mast cells stabilizer disodium cromoglycate (cromolyn) in mouse models have demonstrated promising results (68).

Concluding remarks

This mini review provides an overview of our knowledge of the crosstalk between different inflammatory cell subpopulations and tumor angiogenesis. Targeting these cells has proven to be a promising strategy for tumor treatment. The binary concept of dividing these cells into two subpopulations with, respectively, pro- and anti-inflammatory activities is too simplistic considering their functional plasticity and the context-dependent nature of their behaviors and functions. These inflammatory cells exist in a wide spectrum of phenotypes driven by tumor-derived signals and tissue-specific microenvironments. Recent new technologies including CRISPR gene editing and single-cell sequencing allow us to understand better how these cells regulate tumor angiogenesis. Moreover, the potential transition between immunosuppressive and immunostimulatory phenotypes should be further investigated in the context of different biomarkers of signaling pathways. Future exploration and characterization of specific subgroups will lead to a new direction for targeted tumor angiogenesis.

Author contributions

DR: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by AIL Bari, Italy.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Dunn, GP, Bruce, AT, Ikeda, H, Old, LJ, and Schreiber, RD. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol. (2002) 3:991–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1102-991

2. Schreiber, RD, Old, LJ, and Smith, MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. (2011) 331:1565–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486

3. Balkwill, F, and Mantovani, A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. (2002) 357:539–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0

4. Dvorak, HF. Tumors: wounds that not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. New Engl J Med. (1986) 315:1650–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612253152606

5. Martinez, FO, Sica, A, Mantovani, A, and Locati, M. Macrophage activation and polarization. Front Biosci. (2008) 13:453–61. doi: 10.2741/2692

6. Mantovani, A, Sica, A, and Locati, M. New vistas on macrophage differentiation and activation. Eur J Immunol. (2007) 37:14–6. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636910

7. Ginhoux, F, and Crulliams, M. Tissue-resident macrophage ontogeny and homeostasis. Immnunity. (2016) 44:439–49. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.024

8. Melgarejo, E, Medina, MA, Sanchez-Jimenez, F, and Urdiales, JL. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1: a key mediator in inflammatory processes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. (2009) 41:998–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.07.018

9. Cassetta, L, and Pollard, JW. Targeting macrophages: therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2018) 17:887–904. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.169

10. Mantovani, A, Marchesi, F, Alesci, A, Malesci, A, Laghi, L, and Allavena, P. Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2017) 14:399–416. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.217

11. Cheng, S, Li, Z, Gao, R, Xing, B, Gao, Y, Yang, Y, et al. A pan-cancer single-cell transcriptional atlas of tumor infiltrating myeloid cells. Cell. (2021) 184:792–809. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.010

12. Belgiovine, C, D'Incalci, M, Allavena, P, and Frapolli, R. Tumor associated macrophages and anti-tumor therapies: complex links. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2016) 73:2411–24. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2166-5

13. Sica, A, Schioppa, T, Mantovani, A, and Allavena, P. Tumour-associated macrophages are a distinct M2 polarised population promoting tumour progression: potential targets of anti-cancer therapy. Eur J Cancer. (2006) 42:717–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.003

14. Mantovani, A, Sozzani, S, Locati, M, Allavena, P, and Sica, A. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. (2002) 23:549–55. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4906(02)02302-5

15. Guiducci, L, Vicari, AP, Sangaletti, S, Trinchieri, G, and Colombo, MP. Redirecting in vivo elicited tumor infiltrating macrophages and dendritic cells towards tumor rejection. Cancer Res. (2005) 65:3437–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4262

16. Murray, PJ. Macrophage polarization. Annu Rev Physiol. (2017) 79:541–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034339

17. Zhou, J, Tang, Z, Gao, S, Li, C, Feng, Y, and Zhou, XJF. Tumor-associated macrophages: recent insights and therapies. Front Oncol. (2020) 10:188. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00188

18. Jetten, N, Verbruggen, S, Gijbels, MJ, Post, MJ, De Winther, MP, and Donners, MM. Anti-inflammatory M2, but not pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages promote angiogenesis in vivo. Angiogenesis. (2014) 17:109–18. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9381-6

19. Lin, EY, Li, JF, Gnatovskiy, L, Deng, Y, Zhu, L, Grzesik, DA, et al. Macrophages regulate the angiogenic switch in a mouse model of breast cancer. Cancer Res. (2006) 66:11238–46. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1278

20. Lin, EY, Li, JF, Bricard, G, Wang, W, Deng, Y, Sellers, R, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor restores delayed tumor progression in tumors depleted of macrophages. Mol Oncol. (2007) 1:288–302. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2007.10.003

21. Klimp, AH, Hollema, H, Kempinga, C, van der Zee, A, de Vries, EG, and Daemen, T. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase in human ovarian tumors and tumor-associated macrophages. Cancer Res. (2001) 61:7305–9.

22. Lewis, CE, Leek, R, Harris, A, and McGee, JO’D. Cytokine regulation of angiogenesis in breast cancer: the role of tumor-associated macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. (1995) 57:747–51. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.5.747

23. Sunderkotter, C, Goebeler, M, Schiltze-Osthoff, K, Bhardwaj, R, and Sorg, C. Macrophage-derived angiogenesis factors. Pharmacol Ther. (1991) 51:195–216. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(91)90077-Y

24. Seifert, L, Werba, G, Tiwari, S, Giao Ly, NN, Nguy, S, Alothman, S, et al. Radiation therapy induces macrophages to suppress T-cell responses against pancreatic tumors in mice. Gastroenterology. (2016) 150:1659–1672.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.070

25. Takeuchi, S, Baghdadi, M, Tsuchikawa, T, Wada, H, Nakamura, T, Abe, H, et al. Chemotherapy-derived inflammatory responses accelerate the formation of immunosuppressive myeloid cells in the tissue microenvironment of human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. (2015) 75:2629–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2921

26. De Palma, M, Venneri, MA, Galli, R, Sergi, L, Politi, LS, Sampaolesi, M, et al. Tie 2 identifies a hematopoietic lineage of proangiogenic monocytes required for tumor vessel formation and a mesenchymal population of pericyte progenitors. Cancer Cell. (2005) 8:211–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.002

27. Mazzieri, R, Pucci, F, Moi, D, Zonari, E, Ranghetti, A, Berti, A, et al. Targeting the ANG2/TIE2 axis inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by impairing angio-genesis and disabling rebounds of proangiogenic myeloid cells. Cancer Cell. (2008) 14:299–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.005

28. Venneri, MA, De Palma, M, Ponzoni, M, Pucci, F, Scielzo, C, Zonari, E, et al. Identification of proangiogenic TIE2-expressing monocytes (TEMs) in human peripheral blood and cancer. Blood. (2007) 109:5276–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-053504

29. De Palma, M, Venneri, MA, Roca, C, and Naldini, L. Targeting exogenous genes to tumor angiogenesis by transplantation of genetically modified hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. (2003) 9:789–95. doi: 10.1038/nm871

30. Mayadas, TN, Cullere, X, and Lowell, CA. The multifaceted functions of neutrophils. Annu Rev Pathol. (2014) 9:181–218. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164023

31. Riise, RE, Bernson, E, Aurelius, J, Martner, A, Pesce, S, Della Chiesa, M, et al. TLR-stimulated neutrophils instruct NK cells to trigger dendritic cell maturation and promote adaptive T cell responses. J Immunol. (2015) 195:1121–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500709

32. Fridlender, ZG, Sun, J, Kim, S, Kapoor, V, Cheng, G, Ling, L, et al. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell. (2009) 16:183–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017

33. Uribe-Querol, E, and Rosales, C. Neutrophils in cancer: two sides of the same coin. J Immunol Res. (2015) 2015:983698. doi: 10.1155/2015/983698

34. Bazzoni, F, Cassatella, MA, Rossi, F, Ceska, M, Dewald, B, and Baggiolini, M. Phagocytosing neutrophils produce and release high amounts of the neutrophil-activating peptide 1/interleukin 8. J Exp Med. (1991) 173:771–4. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.771

35. Dubravec, DB, Spriggs, DR, Mannick, JA, and Rodrick, ML. Circulating human peripheral blood granulocytes synthesize and secrete tumor necrosis factor alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1990) 87:6758–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6758

36. Grenier, A, Chollet-Martin, S, Crestani, B, Delarche, C, el Benna, J, Boutten, A, et al. Presence of a mobilizable intracellular pool of hepatocyte growth factor in human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Blood. (2002) 99:2997–3004. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.8.2997

37. Schruefer, R, Sulyok, S, Schymeinsky, J, Peters, T, Scharffetter-Kochanek, K, and Walzog, B. The proangiogenic capacity of polymorphonuclear neutrophils delineated by microarray technique and by measurement of neovascularization in wounded skin of CD18-deficient mice. J Vasc Res. (2006) 43:1–11. doi: 10.1159/000088975

38. Ohki, Y, Heissig, B, Sato, Y, Akiyama, H, Zhu, Z, Hicklin, DJ, et al. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor promotes neovascularization by releasing vascular endothelial growth factor from neutrophils. FASEB J. (2005) 19:2005–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3496fje

39. Ancelin, M, Chollet-Martin, S, Herve, MA, Legrand, C, El Benna, J, Perrot-Applanat, M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor VEGF189 induces human neutrophil chemotaxis in extravascular tissue via an autocrine amplification mechanism. Lab Investig. (2004) 84:502–12. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700053

40. Ribatti, D, and Crivellato, E. The controversial role of mast cells in tumor growth. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. (2009) 275:89–131. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(09)75004-X

41. Jeong, HJ, Oh, HA, Nam, SY, Han, NR, Kim, YS, Kim, JH, et al. The critical role of mast cell-derived hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in human and mice melanoma growth. Int J Cancer. (2013) 132:2492–501. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27937

42. Grimbaldesnton, MA, Nakae, S, Kalesnikoff, K, Tsai, M, and Galli, SJ. Mast cell-derived interleukin 10 limits skin pathology in contact dermatitis and chronic irradiation with ultraviolet B. Nat Immunol. (2007) 38:1095–104. doi: 10.1038/ni1503

43. Ullrich, SE, Nghiem, DX, and Khaskina, P. Suppression of an established immune response by UVA-a critical role for mast cells. Photochem Photobiol. (2007) 83:1095–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00184.x

44. Ribatti, D, and Crivellato, E. Mast cells, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Biochem Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. (2012) 1822:2–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.11.010

45. Metcalfe, DD, Baram, D, and Mekori, YA. Mast cells. Physiol Rev. (1997) 77:1033–79. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.1033

46. Blair, RJ, Meng, H, Marchese, MJ, Ren, S, Schwartz, LB, Tonnesen, MG, et al. Human mast cells stimulate vascular tube formation: tryptase is a novel potent angiogenic factor. J Clin Invest. (1997) 99:2691–700. doi: 10.1172/JCI119458

47. Starkey, JR, Crowle, PK, and Taubenberger, S. Mast cell-deficient W/Wv mice exhibit a decreased rate of tumor angiogenesis. Int J Cancer. (1988) 42:48–52. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910420110

48. Coussens, LM, Raymond, WW, Bergers, G, Laig-Webster, M, Behrendtsen, O, Werb, Z, et al. Inflammatory mast cells up-regulate angiogenesis during squamous epithelial carcinogenesis. Genes Dev. (1999) 13:1382–97. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1382

49. Coussens, LM, Tinkle, CL, Hanahan, D, and Werb, Z. MMP-9 supplied by bone marrow-derived cells contributes to skin carcinogenesis. Cell. (2000) 103:481–90. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00139-2

50. Cirri, P, and Chiarugi, P. Cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor cells: a diabolic liaison driving cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev. (2012) 31:195–208. doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9340-x

51. Arina, A, Idel, C, Hyjek, EM, Alegre, ML, Wang, Y, Bindokas, VP, et al. Tumor-associated fibroblasts predominantly come from local and not circulating precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2016) 113:7551–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600363113

52. Sahai, E, Astsaturov, I, Cukierman, E, DeNardo, DG, Egeblad, M, Evans, RM, et al. A framework for advancing our understanding of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Cancer. (2020) 20:174–86. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0238-1

53. Bartoschek, M, Oskolkov, N, Bocci, M, Lövrot, J, Larsson, C, Sommarin, M, et al. Spatially and functionally distinct subclasses of breast cancer associated fibroblasts revealed by single cell RNA sequencing. Nat Commun. (2018) 9:5150. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07582-3

54. Bochet, L, Lehuédé, C, Dauvillier, S, Wang, YY, Dirat, B, Laurent, V, et al. Adipocyte-derived fibroblasts promote tumor progression and contribute to the desmoplastic reaction in breast cancer. Cancer Res. (2013) 73:5657–68. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0530

55. Helms, EJ, Berry, MW, Chaw, RC, DuFort, CC, Sun, D, Onate, MK, et al. Mesenchymal lineage heterogeneity underlies non redundant functions of pancreatic cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Discov. (2022) 12:484–501. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0601

56. Raz, Y, Cohen, N, Shani, O, Bell, RE, Novitskiy, SV, Abramovitz, L, et al. Bone marrow-derived fibroblasts are a functionally distinct stromal cell population in breast cancer. J Exp Med. (2018) 215:3075–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180818

57. Müerköster, S, Wegehenkel, K, and Arlt, A. Tumor stroma interactions induce chemoresistance in pancreatic ductal carcinoma cells involving increased secretion and paracrine effects of nitric oxide and interleukin-1β. Cancer Res. (2004) 64:1331–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1860

58. Augusten, M. Cancer-associated fibroblasts as another polarized cell type of the tumor microenvironment. Front Oncol. (2014) 4:62. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00062

59. Bernard, V, Semaan, A, Huang, J, San Lucas, FA, Mulu, FC, Stephens, BM, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of pancreatic cancer precursors demonstrates epithelial and microenvironmental heterogeneity as an early event in neoplastic progression. Clin Cancer Res. (2019) 25:2194–205. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-1955

60. Saadi, A, Shannon, NB, Lao-Sirieix, P, O’Donovan, M, Walker, E, Clemons, NJ, et al. Stromal genes discriminate preinvasive from invasive disease, predict outcome, and highlight inflammatory pathways in digestive cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2010) 107:2177–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909797107

61. Bejarano, L, Jordāo, MJC, and Joyce, JA. Therapeutic targeting of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Discov. (2021) 11:933–59. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1808

62. Hume, DA, and MacDonald, KP. Therapeutic applications of macrophage colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF-1) and antagonists of CSF-1 receptor (CSF-1R) signaling. Blood J Am Soc Hematol. (2012) 119:1810–20. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379214

63. Komohara, Y, Fujiwara, Y, Ohnishi, K, and Takeya, M. Tumor-associated macrophages: potential therapeutic targets for anti-cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. (2016) 99:180–5. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.11.009

64. Zhang, SY, Song, XY, Li, Y, Ye, LL, Zhou, Q, and Yang, WB. Tumor associated macrophages: a promising target for a cancer immunotherapeutic strategy. Pharmacol Res. (2020) 161:105111. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105111

65. Xie, F, Xu, M, Lu, J, Mao, L, and Wang, SJM. The role of exosomal PD-L1 in tumor progression and immunotherapy. Mol Cancer. (2019) 18:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1074-3

66. Beatty, GL, Li, Y, and Long, KB. Cancer immunotherapy: activating innate and adaptive immunity through CD40 agonists. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. (2017) 17:175–86. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2017.1270208

67. Masucci, MT, Minopoli, M, and Carrieri, MV. Tumor associated neutrophils. Their role in tumorigenesis, metastasis, prognosis and therapy. Front. Oncologia. (2019) 9:1146. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01146

Keywords: angiogenesis, fibroblasts, macrophages, mast cells, neutrophils, tumor progression

Citation: Ribatti D (2024) Different subpopulations of macrophages, neutrophils, mast cells, and fibroblasts are involved in the control of tumor angiogenesis. Front. Med. 11:1481609. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1481609

Edited by:

Luigi M. Terracciano, University of Basel, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Navin K. Chintala, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Ribatti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Domenico Ribatti, ZG9tZW5pY28ucmliYXR0aUB1bmliYS5pdA==

Domenico Ribatti

Domenico Ribatti