95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Med. , 16 September 2024

Sec. Dermatology

Volume 11 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1454776

Background: Safflower, phellodendron, scutellaria baicalensis, coptis, and gardenia (SPSCG) are medicinal plants with a wide range of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. However, the related mechanism of SPSCG against hand-foot syndrome (HFS) has yet to be revealed.

Objective: To investigate the mechanisms of SPSCG in the treatment of HFS using the Network Pharmacology.

Methods: Active ingredients and targets of SPSCG for HFS were screened by the Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) and Swiss Target Prediction databases. Potential therapeutic targets were collected from the GeneCards and OMIM databases. Subsequently, protein–protein interactions (PPI), Gene Ontology (GO) annotations, and pathways from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) were performed to investigate the potential mechanism of the SPSCG in HFS. Then, molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations were performed to predict the binding interactions between the active compound and the core target. Finally, vitro experiments were used to verify the repair effect of key ingredients of SPSCG on cell damage caused by 5-Fluorouracil.

Results: Quercetin, kaempferol, β-sitosterol, and stigmasterol were identified as the major active components of SPSCG. GO analysis showed a total of 1,127 biological processes, 42 terms cellular components, and 57 molecular functions. KEGG analysis showed that the MAPK, TNF, and IL-17 signaling pathways were significantly enriched. The PPI analysis discovered that EGFR, CASP3, AKT1, CCND1, and CTNNB1 shared the highest centrality among all target genes. The experimental results confirmed that these SPSCG active ingredients could treat HFS by reducing inflammation reaction and promoting cell damage repair.

Conclusion: SPSCG may alleviate HFS by exerting antioxidative effects and suppressing inflammatory responses.

Hand–foot syndrome (HFS) is a prevalent cutaneous toxic reaction to chemotherapy in various malignancies (1), which was initially identified and documented by Dr. Zuehlke in 1974 (2). HFS typically occurs in the palms of the hands and on the soles of the feet, with symptoms such as numbness, tingling, ulcers, skin peeling, or even erosion, greatly affecting patients’ life quality (3). The clinical manifestations of HFS vary depending on the drug, treatment protocol, dosage, plasma concentration, and treatment duration. The incidence of HFS ranges from 6 to 64% (4). HFS is thought to be caused by an inflammatory response (5) associated with the proinflammatory receptor enzyme COX-2 (cyclooxygenase 2) and the accumulation and metabolism of antimetabolites (6). Therefore, in Western Medicine, the management of HFS involves reducing the dose of chemotherapy and increasing the interval between cycles, or discontinuing the treatment. Drug therapy for HFS primarily includes the use of oral celecoxib (7) or glucocorticoids (8). However, long-term use of such drugs can have anti-inflammatory-related and hormone-related negative effects. Additionally, any disruption or reduction in anti-cancer treatment can affect treatment outcomes. At present, effective treatment strategies for HFS are lacking. However, plant products hold great promise in the treatment of inflammatory and allergic reactions, with fewer side effects (9). Consequently, plant-derived compounds or plant extracts can be used to develop novel anti-inflammatory drugs for treating HFS.

Safflower, phellodendron, scutellaria baicalensis, coptis, and gardenia (SPSCG) are medicinal plants with a wide range of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. According to the meta-analysis, safflower could alleviate the symptoms of fluorouracil-induced HFS (10). However, the mechanism is uninvestigated. Compound phellodendron also could suppress inflammatory responses by regulating the TLR4/nuclear factor κ-B (NF-κB)/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway (11). Recent studies demonstrated that scutellaria baicalensis, a perennial herb belonging to the Lamiaceae family, had anti-inflammatory (12–14) and antioxidant activities (15, 16). Coptis exhibited various pharmacological activities, including antibacterial, antiviral, anticancer, and antioxidant process (17). Gardenia (Rubiaceae) is widely used in both TCM and culinary. According to TCM principles, gardenia could access the heart, lung, and tri-jiao meridians, thus reducing pathological internal heat and promoting blood cooling (18). Geniposide has been identified as the primary active constituent of the gardenia (19), which, exerts anti-inflammatory effects by regulating the MAPK/NF-κB and phosphatidyl inositol 3 kinase–protein kinase B (PI3K–Akt) signaling pathways (20). In addition, it induced the IL-10, suppressing the expression of proinflammatory factors and facilitating skin wound healing (21). Hence, it holds some merits in investigating the role of SPSCG in HFS for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects.

Network Pharmacology integrates bioinformatics, multidirectional pharmacology, computer science, and other interdisciplinary fields (22). It can be used to elucidate the potential mechanisms of drug action from various perspectives, reflecting the comprehensive and systematic nature of drug action. Investigating the principles of TCM and syndrome differentiation in TCM is challenging. However, Network Pharmacology is a promising approach to overcoming this challenge and, therefore, has received more attention in research on TCM (23).

In this study, Network Pharmacology was used to identify active components of SPSCG, including quercetin, β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, and kaempferol. We also intersected SPSCG target genes with HFS-related genes to determine more effective drugs for treating HFS. The findings may provide a valuable reference for future studies.

The active components and targets of SPSCG were identified using the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology (TCMSP) database and analysis platform. ADMET lab 2.01 was used for the insilico Drug metabolism study. The most commonly used screening parameter for web-based pharmacological analysis was oral bioavailability (OB), and drug-likeness (DL). In this study, the criteria of OB ≥ 30% and drug-likeness ≥0.18 were applied. Active components meeting these criteria were selected, and the corresponding targets were obtained using Mol ID. Gene names were normalized using the UniProt database.2

The keyword “hand-foot syndrome” was applied in the DisGeNET,3 OMIM,4 and GeneCards5 databases to screen, de-duplicate, and integrate HFS-related targets. VENNY2.1.0 was used to intersect the targets of SPSCG and HFS-related targets to obtain shared core targets.

The SPSCG and its corresponding active components and targeted genes were imported into Excel to generate network and attribute files. Then, the Cytoscape (version 3.7.2) software was used to visualize the network, and the built-in tool Network Analyzer was used to assess the topological parameters of the network. Core active components and target genes were identified based on the node degree value (degree).

To visualize the interaction between active components of SPSCG and HFS-related targets, the overlapping targets were imported into the STRING (version 11.0) database6 to establish a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network. The biological species was defined as “Homo sapiens,” and the minimum interaction threshold was defined as “medium confidence” (>0.4). TSV files were acquired, and the PPI network was visualized using the Cytoscape (version 3.7.2) software. The Network Analyzer was used to assess the topological parameters of the PPI network, and key targets were identified based on the degree value.

The targets of SPSCG related to HFS were imported into the Metascape platform7 for the GO and KEGG analysis. Significantly enriched biological processes and signaling pathways were identified based on p-values of <0.01. The micro-shengxin online platform was used to access GO entries. The results of the KEGG pathway analysis were visualized on a bubble map.

Ligand–receptor interactions were simulated through molecular docking to predict the binding mode and energy. Initially, the sdf fragments of the three-dimensional structures of receptors were obtained using the PubChem database.8 Subsequently, Openbabel and Autodock were used to convert the identified fragments to the PDBQT format. Key proteins/ligands were identified from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) database,9 and the PyMol software was used for removal of water molecules, extraction of ligands, determination of docking boxes, and other necessary manipulations. AutoDock was used for hydrogenation and charge processing. The targets and drugs were prepared and molecular docking performed inside a grid box (40 Å × 40 Å × 40 Å). A Lamarckian genetic algorithm was used for protein-ligand docking with default settings, an exhaustiveness level of 8, and a maximum of 10 outputs. The outputs were downloaded in the PDBQT format. Finally, binding energy was evaluated through molecular docking, with lower values indicating more stable binding between the ligand and receptor.

Molecular dynamics simulations of the ligand-receptor complexes were conducted using the GROMACS.10 The protein topology files were generated utilizing the AMBER99SB-ILDN force field, while the ligand topology files were created using the ACPYPE script under the AMBER force field. Then, the simulations were carried out in a triclinic box filled with TIP3 water molecules. Following system neutralization with NaCl counter ions, energy minimization was performed for 1,000 steps. Subsequently, the system was equilibrated through NVT and NPT ensembles for 100 ps each. Finally, molecular dynamics simulations were executed for 100 ns per system under periodic boundary conditions at a temperature of 310 K and 1.0 bar pressure.

Fluorouracil (5-FU, HY-90006), Quercetin (HY-18085), Kaempferol (HY-14590), Beta-Sitosterol (HY-N0171A), and Stigmasterol (HY-N0131) were all obtained from the MedChemExpress. IL-6 (BE6304H1), AKT1 (BE03171H1), CASP3 (BE04705H1), CCND1 (BE5634H1), CTNNB1 (BE5900H1) and EGFR (BE04853H1) were all obtained from MCE. IL-1β was all obtained from the Yuli Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Shanghai.

HACAT cells (Human immortal keratinocyte line) were obtained from the Asia-Vector Biotechnology (Shanghai) Co.Ltd. HACAT cells were cultured in DMEM (dulbecco’s modified eagle medium) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

Cells in the logarithmic phase of growth (2000 cells/well) were cultured on 96-well plates filled with 150 μL complete medium for 1 day. After different treatments, CCK-8 solution (10 μL, Sigma, Germany) was added and cultured for 1 h at 37°C. After that, the optical density of each well at 450 nm was detected.

IL-6 and IL-1 β in cell culture supernatants were confirmed by ELISA using the ELISA Kit (Asia-Vector Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Shanghai) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. AKT1, CASP3, CCND1, CTNNB1, and EGFR in cells were confirmed by ELISA using the ELISA Kit (Asia-Vector Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Shanghai) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

All experiments were independently performed at least three times. Data were represented as mean ± standard deviation. Means between the two groups were compared using the one-way ANOVA, with Dunnett’s correction (GraphPad Software). Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05. Statistical tests are indicated in the figure legends: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

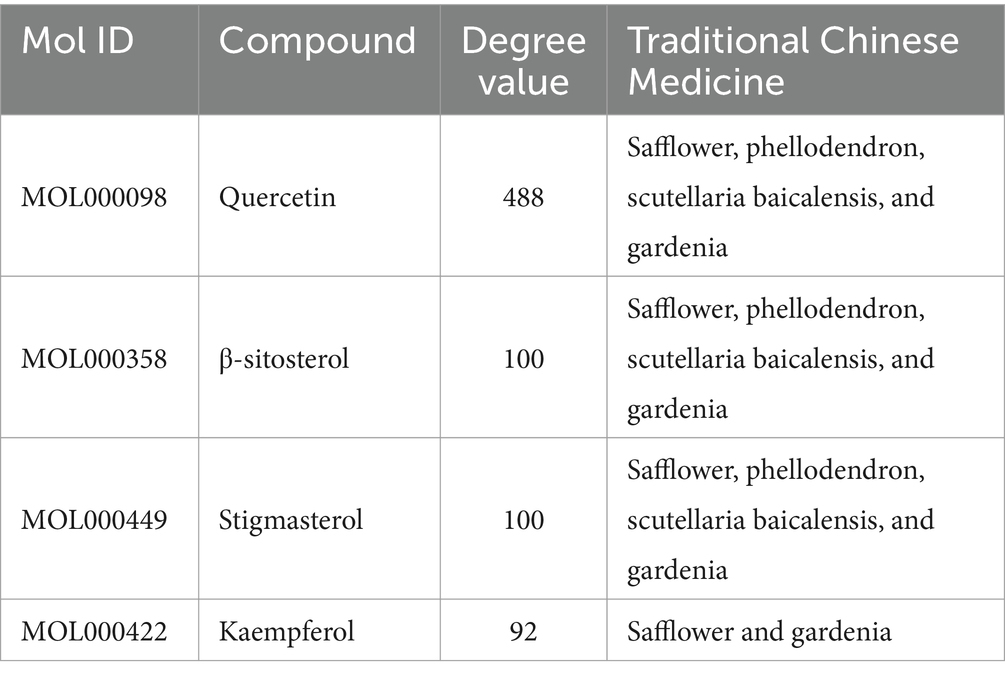

A comprehensive search in the TCMSP database revealed active components in safflower, phellodendron, scutellaria baicalensis, and gardenia, respectively. Notably, the identified active components primarily contained the quercetin, kaempferol, β-sitosterol, and stigmasterol (Table 1). Subsequently, 1,212 target genes of these components were identified. After gene normalization and weight removal using the UniProt database, 197 target genes were anchored. Table 2 shows the drug metabolism and molecular structure of active ingredients including quercetin, kaempferol, β-sitosterol, and stigmasterol.

Table 1. Relevant information about the active ingredients of safflower, phellodendron, scutellaria baicalensis, coptis, and gardenia.

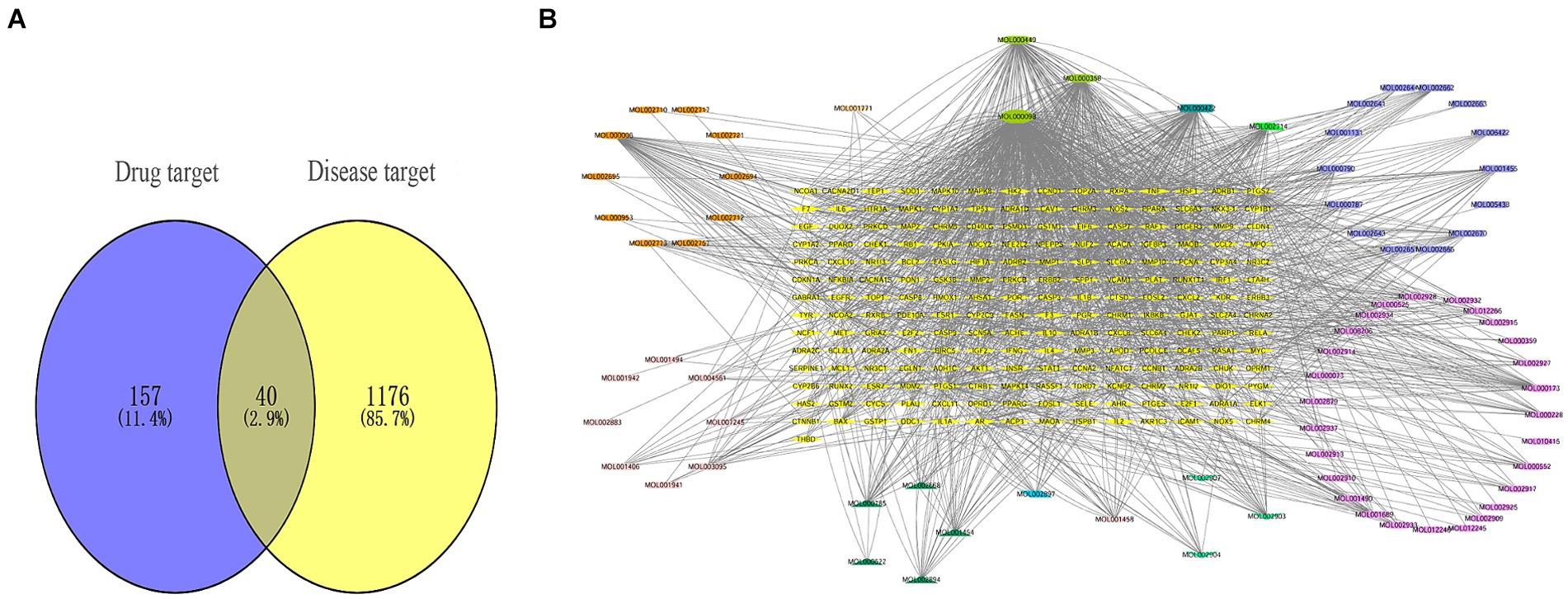

Firstly, we obtained a total of 179 drug targets using the database. Then, we identified 1,216 targets for HFS using Gene Cards, OMIM, TTD, Pharm GKB, and Drug Bank databases with the keyword “hand-foot syndrome.” The Venny 2.1.0 tool was used to intersect the 197 targets of SPSCG and 1,216 HFS-related targets, resulting in the identification of 40 overlapping targets (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Composite target relationship between safflower, phellodendron, scutellaria baicalensis, coptis, gardenia and hand-foot syndrome. (A) Wayne diagram of target for intersection of safflower, phellodendron, scutellaria baicalensis, coptis, and gardenia with hand-foot syndrome. (B) Safflower, phellodendron, scutellaria baicalensis, coptis, and gardenia-active ingredient-the target network plot.

The SPSCG-active component–target network was constructed using the Cytoscape (version 3.7.2) software (Figure 1B). The network comprised 95 active components of SPSCG, which had a total of 40 common targets. In particular, 16, 32, 24, 11, and 12 active components belonged to safflower, scutellaria baicalensis, phellodendron, coptis chinensis, and gardenia, respectively. Based on the degree value, the top four active components in the network were quercetin, kaempferol, β-sitosterol, and stigmasterol. Kaempferol was identified as a common component of two herbs (Table 1), whereas quercetin, β-sitosterol, and stigmasterol were identified as common components of four herbs (Table 1). These four active components (Table 1) may contribute to the anti-inflammatory effects of SPSCG in treating HFS.

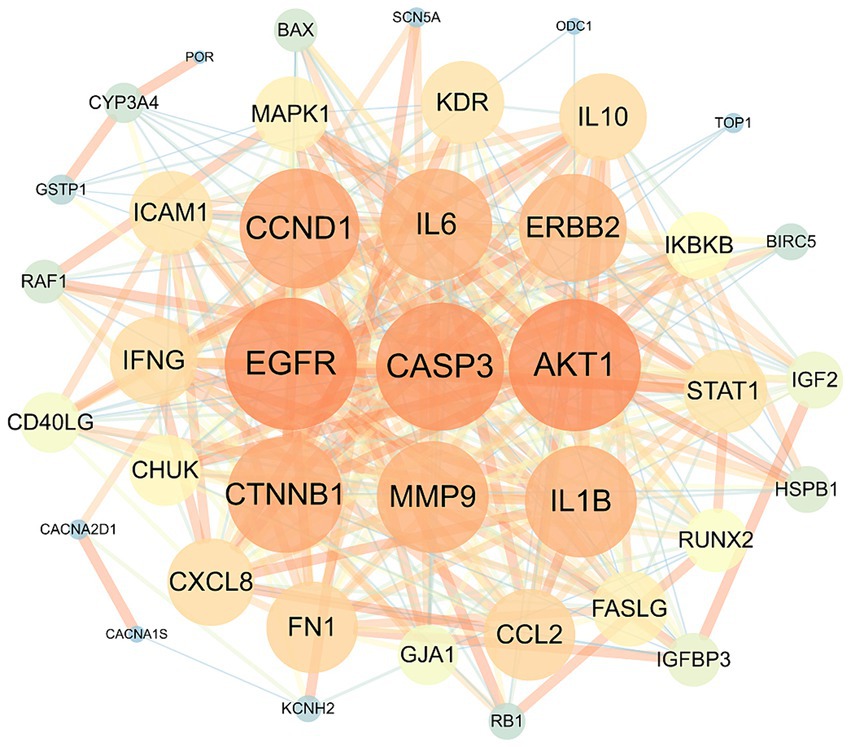

The overlapping targets were submitted to the STRING (version 11.0) database, with the organism species specified as “Homo sapiens” and the minimum interaction threshold set to “medium confidence” (>0.4). Subsequently, the TSV file was downloaded and used to generate the PPI network of the overlapping targets using Cytoscape. In the resulting network, nodes with larger areas and font sizes were shown in dark red, indicating higher degree values and importance of the corresponding targets within the network. Based on the degree value, interleukin (IL)-6, CCND1, EGFR, CASP3, AKT1, and CTNNB1 were identified as the top six core targets (Figure 2). These target genes may play a crucial role in treating HFS.

Figure 2. The protein–protein interaction network of safflower, phellodendron, scutellaria baicalensis, coptis, and gardenia with the target proteins.

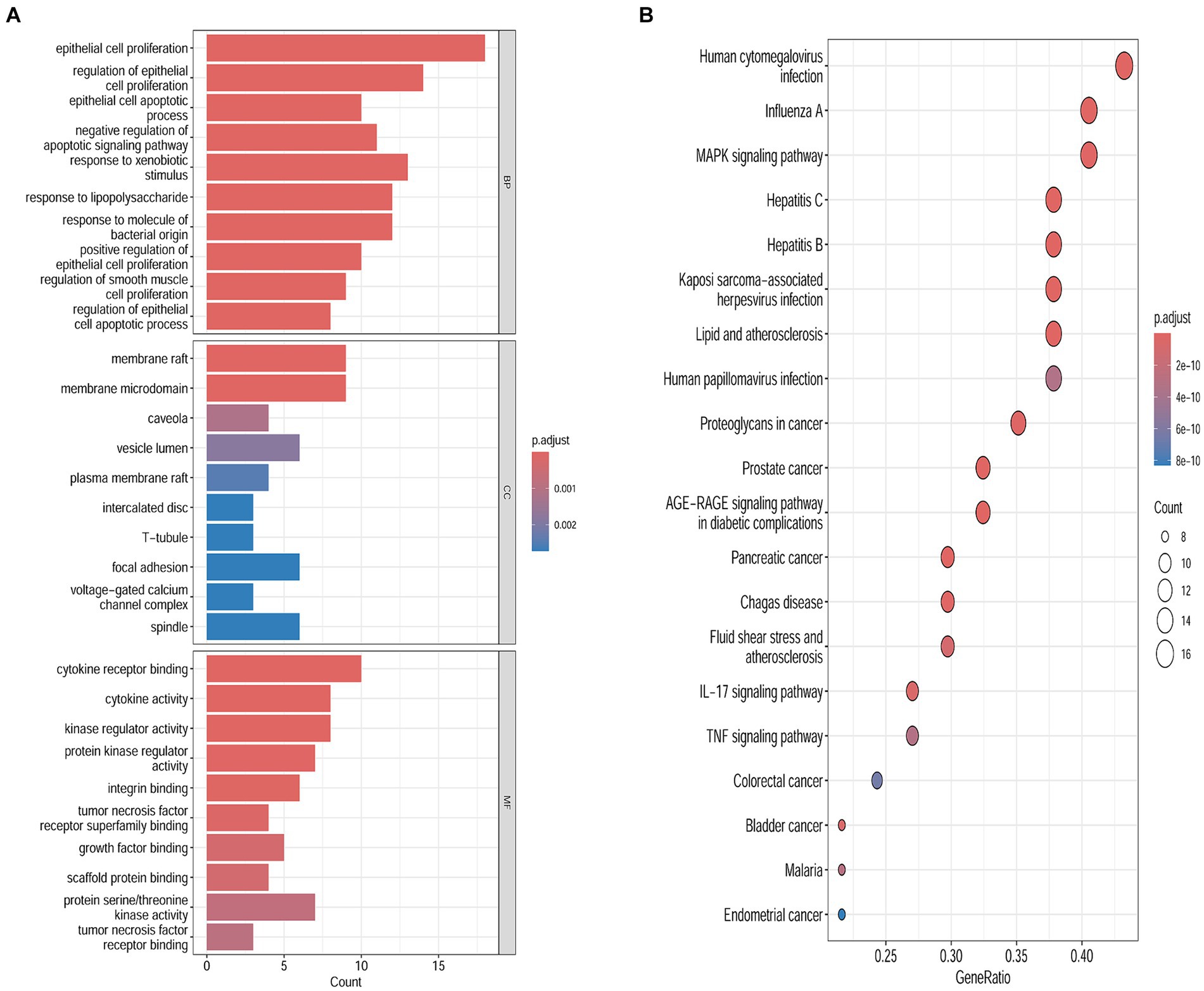

To examine the correlation between target genes and the biological phenotypes of HFS, the 40 common targets were subjected to GO and KEGG analysis using the Metascape database. The results showed that the target genes were significantly enriched in 1226 GO terms (1,127 BPs, 42 CCs, and 57 MFs) and 149 KEGG pathways (p < 0.01). A Cytoscape 3.9.0 online platform was used to visualize the top 10 GO terms on a three-in-one bar chart and the top 20 KEGG pathways on a bubble chart. Based on GO analysis, the target genes were primarily enriched in BPs, such as epithelial cell proliferation and positive regulation of epithelial cell proliferation. CCs, such as cell–cell contact zone and focal adhesion; and MFs such as cytokine receptor binding, growth factor binding, and scaffold protein binding (Figure 3A). KEGG analysis showed that the target genes were primarily enriched in the MAPK signaling pathway and other related pathways (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Biological functions and the pathways enrichment analyses. (A) Genomes pathway analysis of the intersection targets of safflower, phellodendron, scutellaria baicalensis, coptis, and gardenia and hand-foot syndrome (BP/CC/MF). (B) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes analysis of the intersection targets of safflower, phellodendron, scutellaria baicalensis, coptis, and gardenia and hand-foot syndrome.

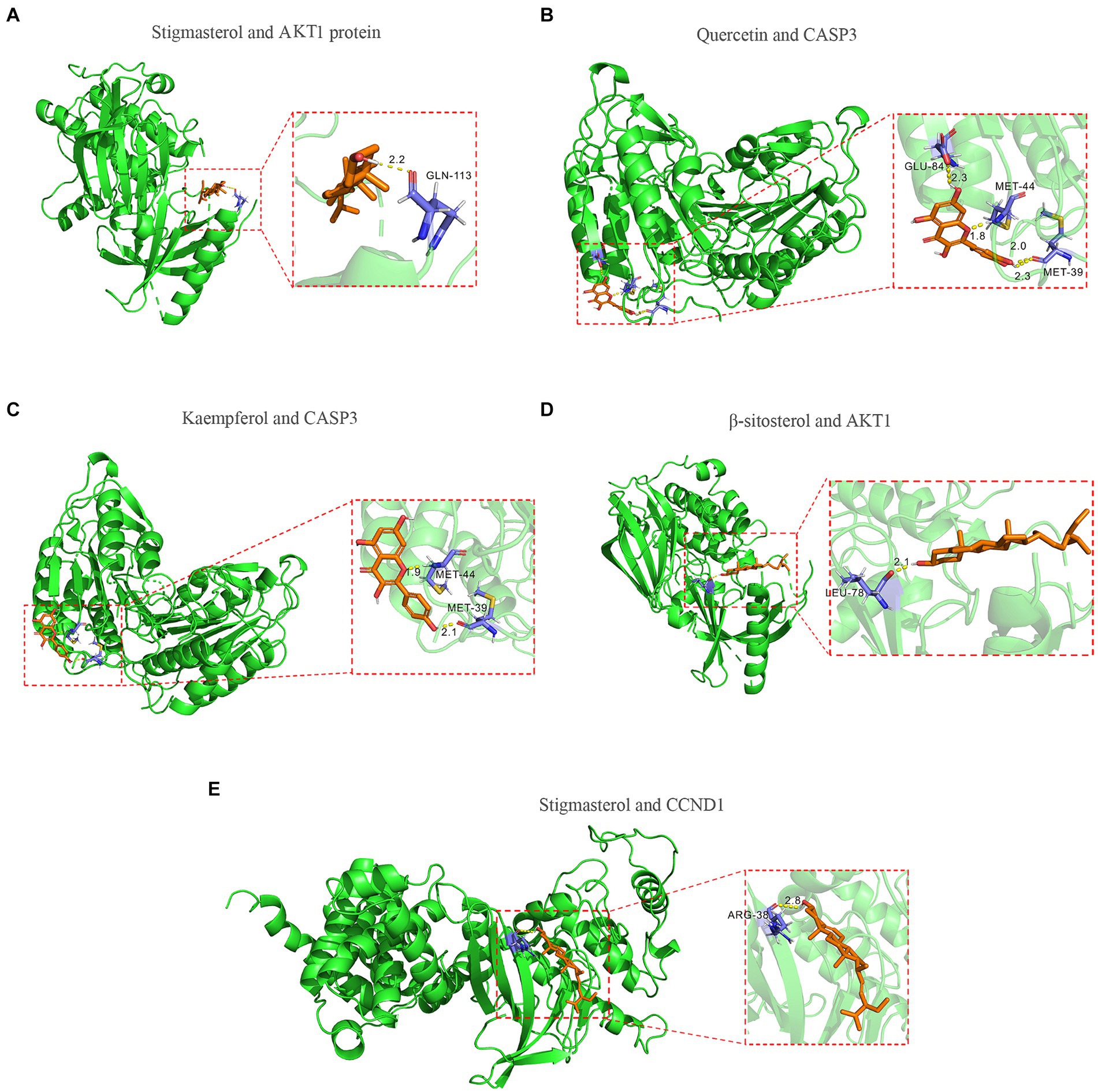

To further validate the predictive capability of bioinformatics, molecular docking was employed to investigate the potential of SPSCG in treating HFS. Following selection via CytoNCA analysis, the most critical HFS targets (AKT1, CASP3, and CCND1) were subjected to molecular docking with SPSCG (Figures 4A–E). As shown in Figures 4B,C, there were four and two hydrogen bonds in Quercetin-CASP3 and Kaempferol-CASP3, respectively. In Figures 4A,D,E, each had one hydrogen bond in Quercetin-CASP3, β-sitosterol-AKT1, and Stigmasterol-CCND1. Table 3 shows the hydrogen bond distance, interacting residues and unit of docking score. As depicted in Table 3, we checked the hydrogen bond distances in docked complexes. The hydrogen bond distances of Stigmasterol-CCND1, Quercetin-CASP3, Kaempferol-CASP3, β-sitosterol-AKT1, and Stigmasterol-CCND1 were 2.8, (2.3; 1.8; 2.0; 2.3), (1.9; 2.1), 2.1, and 2.8 angstroms, respectively. The maximum binding free energies for AKT1, CASP3, CCND1, CTNN1, and EGFR with the quercetin, β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, and kaempferol were − 4.93, −5.2, −4.09, −3.03, and − 3.65, respectively (Table 3). The docking binding free energies of the aforementioned molecules were all less than −5, indicating the strong binding affinity of SPSCG to the core targets of HFS. The cartoon representation highlights the specific locations of the ligand-protein binding residues (Figures 4A–E).

Figure 4. Molecular docking of core components of safflower, phellodendron, scutellaria baicalensis, coptis, and gardenia to key targets figure. (A) Stigmasterol and AKT1 protein. (B) Quercetin and CASP3 protein. (C) Kaempferol and CASP3 protein. (D) β-sitosterol and AKT1 protein. (E) Stigmasterol and CCND1.

Table 3. The docking of safflower, phellodendron, scutellaria baicalensis, coptis, and gardenia core components with key target molecules.

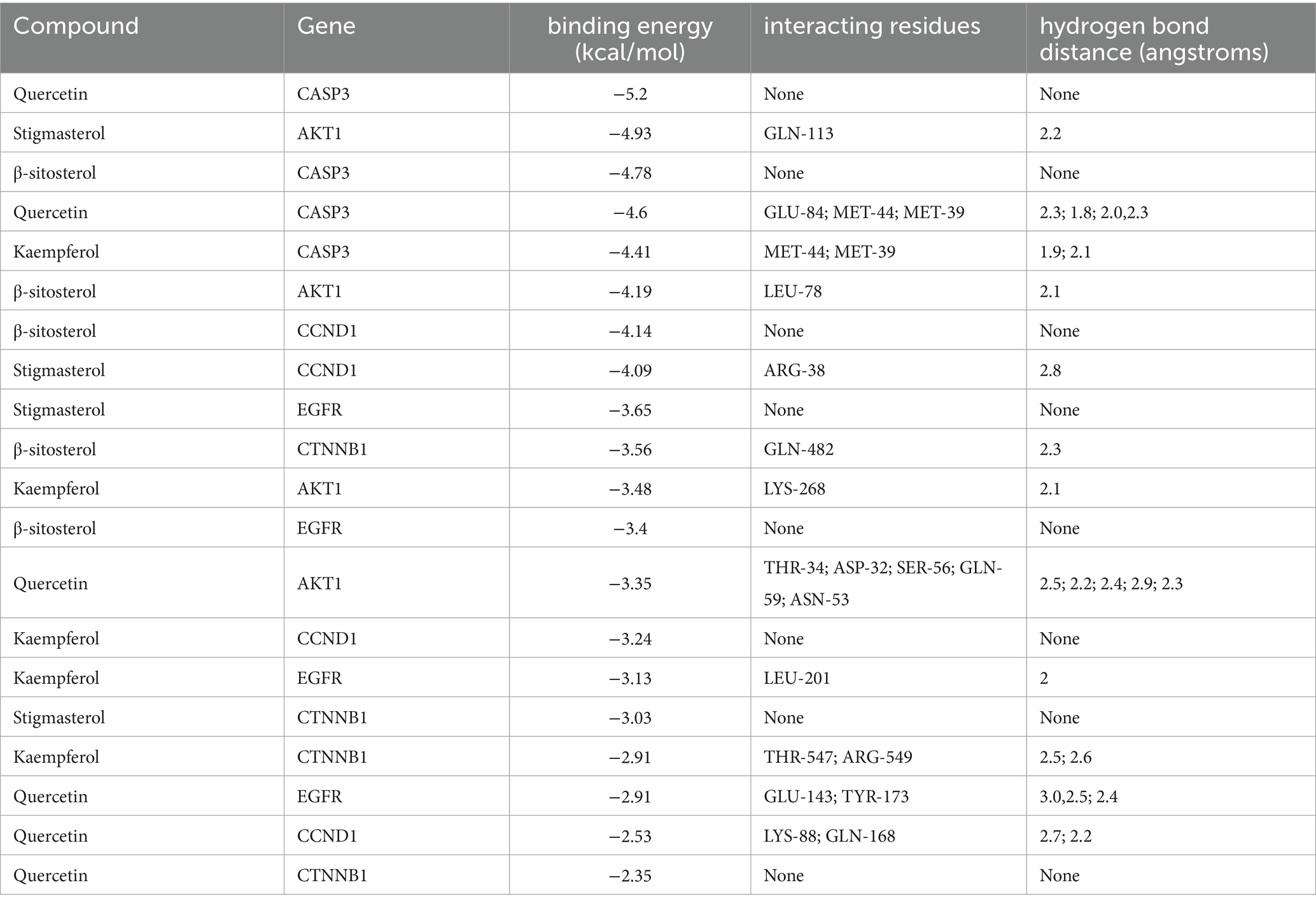

According to molecular docking results, the binding force between the compound and the protein increases as the binding free energies decrease. We used molecular dynamics simulations to validate the binding mode between Quercetin and CASP3, Kaempferol and CASP3, Stigmasterol and AKT1, β-sitosterol and AKT1, Stigmasterol and CCND1. And the obtained RMSD, RMSF, and hydrogen bond were used to evaluate their relative stability. The trend of RMSD of the protein and ligand complexes is a crucial indicator of whether the simulation has reached stability. As depicted in Figures 5A,D,G,J,M, the conformation reached a relatively stable state at approximately 20, 5, 3, 15, and 10 ns respectively, and fluctuated around 1.8–2.3, 1.25–1.5, 1.425–1.575, 1.65–2.05, and 2.05–2.65 angstroms, respectively. Complexes with small fluctuations were relatively stable, and those with large fluctuations were relatively unstable. RMSF values quantify a protein’s structural stability, atomic mobility, and residual flexibility upon collision. As depicted in Figures 5B,E,H,K,N, each system also exhibited different RMSF fluctuation trends and flexible regions. Hydrogen bonds indicate the binding strength between the ligand and the protein. The docked complex had a stable pattern of hydrogen bonds (Figures 5C,F,I,L,O). Complexes with hydrogen bonds are relatively stable. The molecular dynamics simulations results of hydrogen bonds were correlated with the dokcing results. Thus, the molecular dynamics simulations demonstrate that Stigmasterol-CCND1, Quercetin-CASP3, Kaempferol-CASP3, β-sitosterol-AKT1, and Stigmasterol-CCND1 had relatively good binding ability.

Figure 5. Molecular dynamics simulation. (A) The RMSD of Stigmasterol-AKT1. (B) The RMSF of Stigmasterol-AKT1. (C) The hydrogen bonds of Stigmasterol-AKT1. (D) The RMSD of Quercetin-CASP3. (E) The RMSF of Quercetin-CASP3. (F) The hydrogen bonds of Quercetin-CASP3. (G) The RMSD of Kaempferol-CASP3. (H) The RMSF of Kaempferol-CASP3. (I) The hydrogen bonds of Kaempferol-CASP3. (J) The RMSD of β-sitosterol-AKT1. (K) The RMSF of β-sitosterol-AKT1. (L) The hydrogen bonds of β-sitosterol-AKT1. (M) The RMSD of Stigmasterol-CCND1. (N) The RMSF of Stigmasterol-CCND1. (O) The hydrogen bonds of Stigmasterol-CCND1.

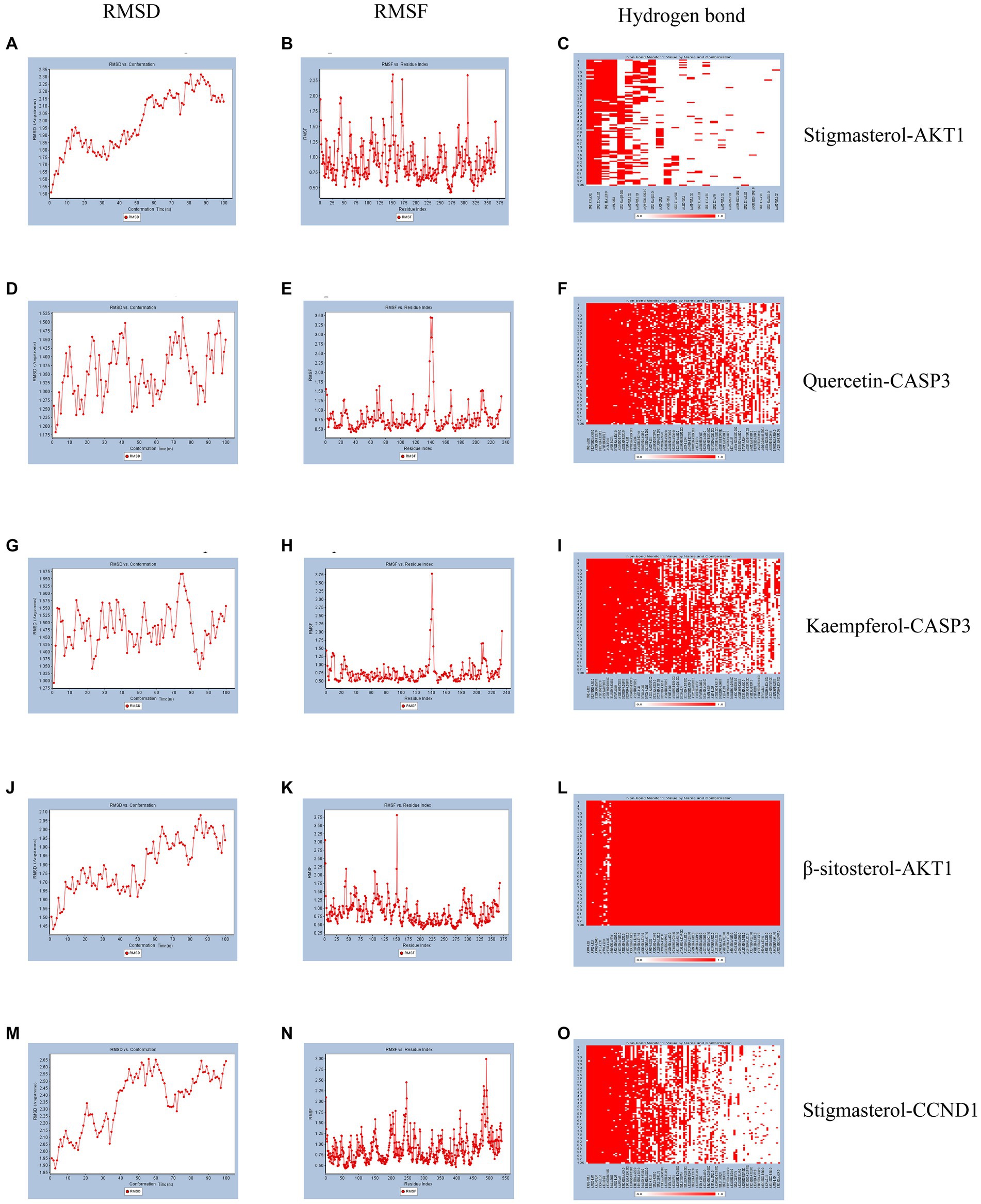

The previous data were obtained from public databases. Next, HACAT cells were cultured in vitro and cytotoxicity was tested with fluorouracil. The optimal dose of 5-FU at 50% cell survival was 802.4uM (Figure 6A). When quercetin (2 uM), kaempferol (1 uM), β-sitosterol (10 uM), and stigmasterol (0.5 uM) were added, the cell survival rate was 100%, indicating that the TCM had no inhibitory effect on cell growth (Figure 6B). When added with quercetin, kaempferol, β-sitosterol, and stigmasterol, the survival rate of cells was higher than that of cells added with 5-FU alone (Figure 6C; all p < 0.0001). This indicated that the cell growth-promoting effect of TCM could antagonize the inhibitory effect of 5-FU.

Figure 6. Relative cell viability in different concentration groups in HACAT cells. (A) After the treatment with different concentrations of 5-FU for 24 h, the relative cell viability was tested by CCK 8 (IC50). The IC50 of 5-FU was the 802.4uM, which was selected for the downstream experiments. (B) After the treatment with 2uM Quercetin, 1uM Kaempferol, 10uMβ-sitosterol and 0.5uM Sigmasterol for 24 h, the relative cell viability was tested by CCK 8 (IC50). (C) After the treatment with 5-FU, 5-FU + 2uM Quercetin, 5-FU + 1uM Kaempferol, 5-FU + 10uM β-sitosterol and 5-FU + 0.5uM Sigmasterol for 24 h, the relative cell viability was tested by CCK 8 (IC50). Data represent mean ± SD. *** vs. Ctrl p < 0.001; ### vs. 5-FU p < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA, with Dunnett’s correction). Significance level, α = 0.05.

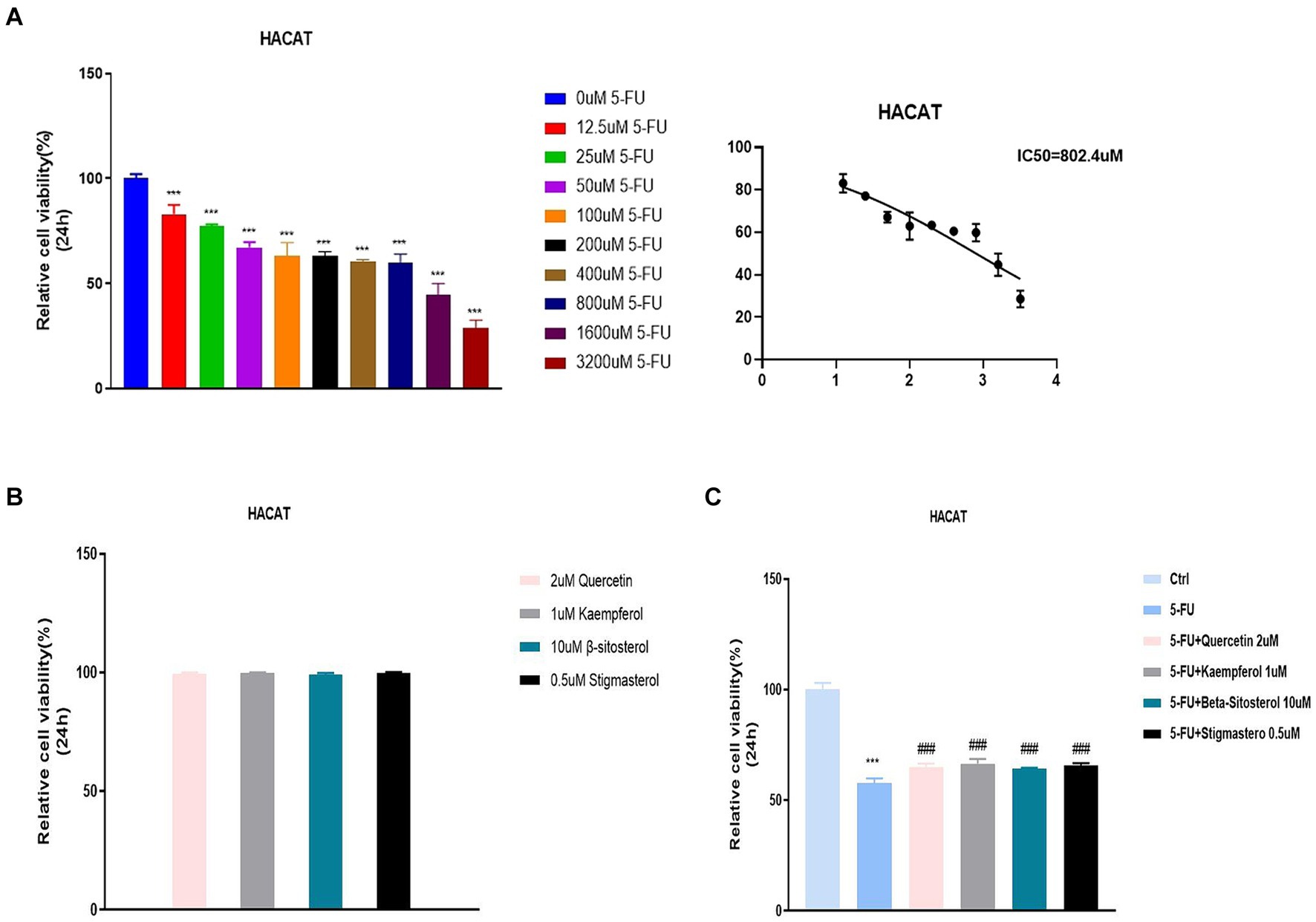

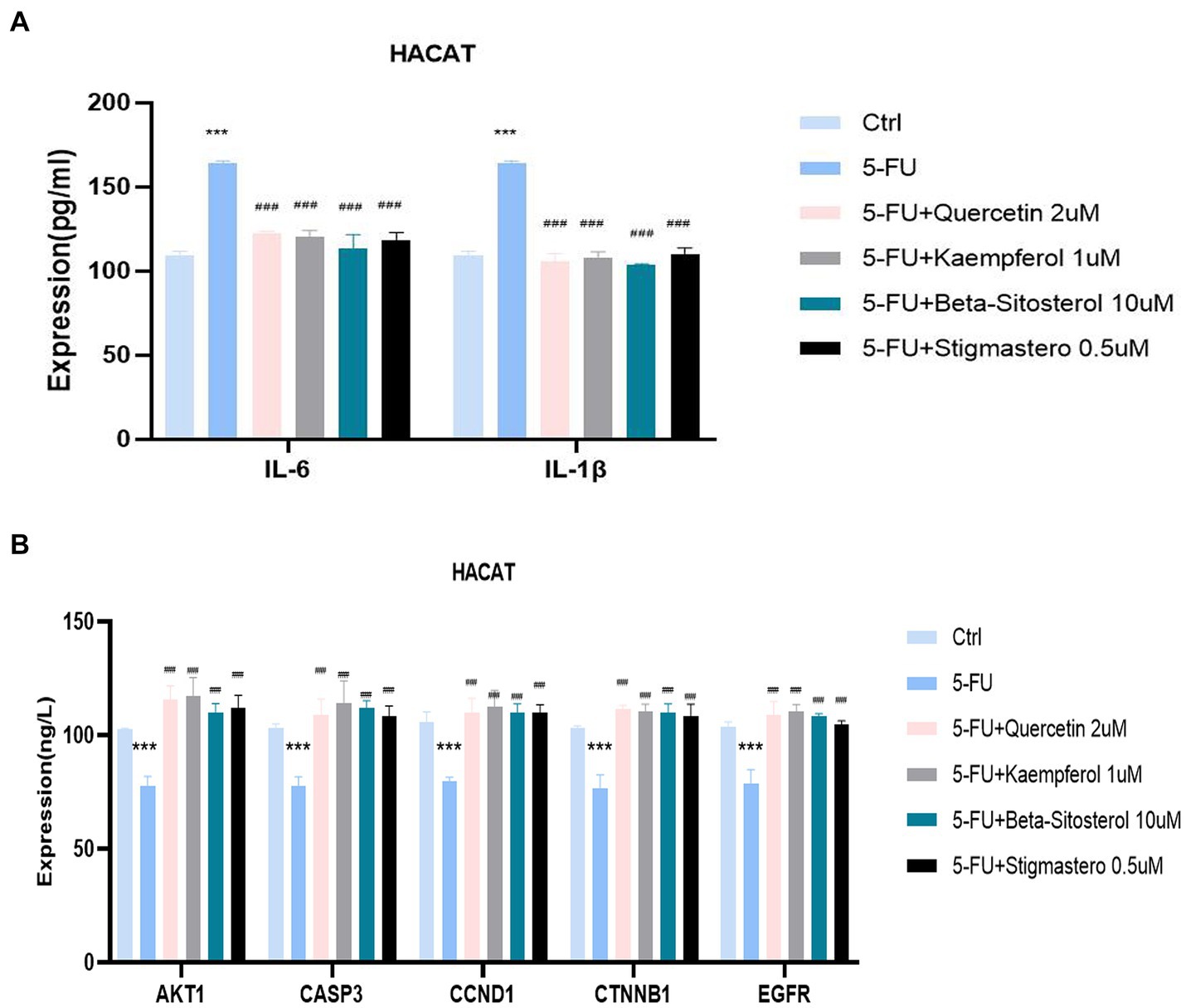

Figure 7A shows that IL-6 and IL-1 β expression were significantly increased in the cells added with 5-FU, when compared with the normal cell group. When added with quercetin, kaempferol, β-sitosterol, and stigmasterol, the IL-6 and IL-1 β levels were lower than that of cells added with 5-FU alone (Figure 7A; all p < 0.0001), and the expression of AKT1, CASP3, CCND1, CTNNB1,and EGFR were higher than that of cells added with 5-FU alone (Figure 7B; all p < 0.0001).

Figure 7. Comparison of the expression of different cytokines and targets in different groups including control (Ctrl), 5-FU, 5-FU + 2uM Quercetin, 5-FU + 1uM Kaempferol, 5-FU + 10uM β-sitosterol, and 5-FU + 0.5uM Sigmasterol. (A) Comparison of the expression of IL-6 and IL-1β in different groups. The test sample was the supernatant taken after 24-h culture. (B) Comparison of the expression of different AKT1, CASP3, CCND1, CTNNB1, and EGFR in different groups. The test sample was the cells taken after 24-h culture. Data represent mean ± SD. *** vs. Ctrl p < 0.001; ### vs. 5-FU p < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA, with Dunnett’s correction). Significance level, α = 0.05.

Network pharmacology involves the identification of drug targets and disease-related genes to assess the therapeutic efficacy. This approach offers the advantages of an increased success rate and the decreased drug development expenses (23). In this study, data from various platforms including network pharmacology were integrated and intersected to investigate the key component of SPSCG in HFS (24). The mechanism of SPSCG in the treatment of HFS was predicted, which warrants subsequent experimental validation.

The precise etiology of HFS remains uncertain, and the mechanisms through which anti-cancer drugs induce HFS may vary. HFS is characterized by varying degrees of necrosis in cells and inflammation at the junction of the epidermis and dermis (4). Additionally, some patients could develop exocrine gland squamous epithelial granuloma or neutrophil-infiltrating hidradenitis (25). Microscopic examination revealed vacuolar degeneration, infiltration by skin basal keratinocytes and perivascular lymphocytes, vasodilation, and edema (26), resembling an inflammatory response. Owing to the abundant capillary networks and higher density of secretory glands in the palms and soles, these sites might accumulate excess chemotherapy drugs (27). Consequently, inflammatory responses are more pronounced in the palms and soles. This phenomenon suggests that HFS can be alleviated and managed by suppressing inflammatory responses. Given that SPSCG is widely used in TCM, this study may present an innovative approach to investigating the mechanism of SPSCG in HFS treatment.

The primary active components of SPSCG contains the quercetin, kaempferol, β-sitosterol, and stigmasterol. Studies have shown that quercetin has antioxidative properties, protects the vascular endothelium, and inhibits inflammatory responses (28). Furthermore, it can decrease the expression of PIK3R1 and EGFR (29), contributing to the repair of skin damage through the PI3K-AKT and EGFR/MAPK pathways. Kaempferol is commonly found in various edible plants and is used to formulate natural medications in TCM (30). It has multiple pharmacological activities, including antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activities (30). Additionally, it could inhibit macrophage inflammation (31) and exert cytoprotective and anti-apoptotic effects (32). β-sitosterol plays an essential role in stabilizing the phospholipid bilayer of the cell membrane (33). It exhibits lipid-lowering, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidative activities (34). It has been shown to mitigate inflammatory response through inhibition of the ERK/p38 and NF-κB pathways induced by LPS in BV2 cells (35). Stigmasterol holds significant therapeutic potential owing to its diverse pharmacological effects, including anti-inflammatory (36) and antioxidative effects (37). It can increase the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-10. Conversely, it can notably increase the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators, including iNOS, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and COX-2. These findings suggest that stigmasterol can effectively alleviate inflammation by suppressing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (38). Therefore, SPSCG’s core active ingredients combat inflammation and aid skin repair via antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cell-protective mechanisms.

In this study, the primary targets of SPSCG for the treatment of HFS were identified as CASP3, EGFR, AKT1, CCND1, and CTNNB1. Caspase 3 played an important role in regulating skin damage, as it was implicated in apoptotic pathways characterized by genomic DNA cleavage, cell membrane phosphatidylserine exposure, and activation by inflammatory cells (39). Inhibition of the CASP3 sustained the inactive phosphorylated state of the FoxO3a, effectively preserving endothelial cell integrity (40). EGFR is a crucial signaling molecule involved in maintaining the structure and functions of the skin and regulating inflammatory and immune responses in the skin (41). Inhibition of EGFR in cuticular cells could aggravate skin inflammation (42). Moreover, EGFR was downregulated at both mRNA and protein levels in dermatitis (43). In this study, stigmasterol was found to exhibit the highest binding affinity to EGFR, suggesting that EGFR might be a promising target for stigmasterol-based treatment in HFS. AKT1 is involved in regulating various biological processes, such as cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Activation of AKT signaling was facilitated by phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K). AKT1 served as a crucial downstream target of the PI3K signaling pathway, contributing to cellular homeostasis during the differentiation of peripheral blood B and T cells (44). The pathological characteristics of HFS include skin damage and inflammation. Hence, alleviating these symptoms represents an effective therapeutic strategy for HFS. EGFR and AKT1 can counteract inflammation. Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs can regulate cellular glycosaminoglycan synthesis by modulating the EGFR and PI3K signaling pathways (45). In this study, β-sitosterol and stigmasterol were found to have significant binding affinity to EGFR and AKT1. We speculate that EGFR/AKT signaling is one of the important pathways that SPSCG functions in HFS treatment. Cyclin D1 exhibits frequent abnormalities in various human cancers (46) and plays a crucial role in facilitating the transition from the G1 to the S phase of the cell cycle in numerous cell types (47). The proximal selective polyadenylation sites of CCND1 have been identified as accelerators of the cell cycle and promoters of cell proliferation (48). In this study, β-sitosterol and CCND1 had the highest binding scores, suggesting that β-sitosterol targets CCND1 to regulate the cell cycle for the HFS treatment. The CTNNB1 gene encodes β-catenin, which serves as a crucial component of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and plays an essential role in cadherin-mediated intercellular adhesion. Numerous studies have shown that downregulation of β-catenin leads to inhibition of cell growth and induction of apoptosis in diverse cell types (49). In the present study, β-sitosterol exhibited the most notable binding affinity to CTNNB1. This finding suggests the involvement of CTNNB1 in cellular regeneration following skin injury, thereby establishing it as a crucial target of β-sitosterol in the management of HFS.

We found that the treatment of HFS with SPSCG involves several interconnected pathways, such as the MAPK, TNF, and IL-17 signaling pathways by GO and KEGG analysis. HFS is a prevalent adverse event associated with various chemotherapeutic drugs and tumor-targeted therapies (2). The pathogenesis of HFS includes the formation of skin keratinocytes, increased levels of thymidine phosphatase, required for the degradation of drugs such as 5-fluorouracil, and result in augmented breakdown and accumulation of cytotoxic metabolites in the skin (50). Furthermore, the vulnerability of minute capillaries in the skin causes ruptures in the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet owing to the pressure exerted during walking or use, thereby releasing cytotoxic agents and inducing inflammatory responses (51). Notably, drugs targeting atopic dermatitis could decrease p38 MAPK levels and inhibit the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway (52). Therefore, MAPK inhibitors might serve as effective therapeutic agents for skin inflammation caused by allergic reactions (53). Suppression of MAPK signaling and modulation of intracellular signaling pathways associated with atopic inflammation has been shown to alleviate the symptoms of atopic dermatitis (54) (55). Consequently, activating the EGFR/AKT signaling pathway while inhibiting MAPK activity can effectively mitigate inflammation and enhance the integrity of the skin barrier, representing a promising strategy for the treatment of HFS. During inflammatory reactions, TNF-α could trigger non-specific immune responses by activating macrophages and promoting the release of additional inflammatory cytokines (56). TNF-α is released during the early stages of both acute and chronic inflammatory conditions, such as septic shock, rheumatoid arthritis, and allergic reactions. The biosynthesis of TNF-α is regulated through intricate and diverse mechanisms, primarily involving gene transcription, mRNA degradation, and intracellular protein signaling (57). SPSCG may inhibit the secretion of TNF-α. However, the underlying mechanisms warrant further investigation.

Our experiment confirmed that the quercetin, kaempferol, β-sitosterol and stigmasterol have a promoting effect on epithelial cell growth at appropriate concentrations, which could antagonize the cytotoxic effects caused by 5-FU. The quercetin, kaempferol, β-sitosterol, and stigmasterol downregulated the inflammatory factors and upregulated cell proliferation-related factors caused by 5-FU. Therefore, the quercetin, kaempferol, β-sitosterol, and stigmasterol may treat HFS for their anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and cell damage repair effects. However, we did not establish an animal model to validate the repair effect of the core drugs on HFS.

There are several limitations to this study. The network pharmacology approach improves the investigation of natural plant products used in TCM but faces challenges owing to incomplete data and evaluation criteria. In the future study, we want to verify it with clinical studies. Secondly, in vivo experiments should be integrated to validate the targets and pathways of natural products to expand the clinical application of TCM.

In summary, quercetin, kaempferol, β-sitosterol, and stigmasterol are the active components of SPSCG, which can target AKT1, CASP3, CCND1, CTNNB1, and EGFR to exert anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects for treating HFS. However, further investigation is required to validate these findings and elucidate the mechanisms of the abovementioned active components in treating HPS.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethical approval was not required for the studies on humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used. Ethical approval was not required for the studies on animals in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements because only commercially available established cell lines were used.

PL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. LC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. JL: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by research projects for the Natural Science Foundation of Nanping City of China (grant no. 2019 J45).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^https://admetmesh.scbdd.com/

8. ^https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

10. ^version 2021.2, https://www.gromacs.org/

1. Lévy, E, Piedbois, P, Buyse, M, Pignon, JP, Rougier, P, Ryan, L, et al. Toxicity of fluorouracil in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: effect of administration schedule and prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. (1998) 16:3537–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.11.3537

2. Miller, KK, Gorcey, L, and Mclellan, BN. Chemotherapy-induced hand-foot syndrome and nail changes: a review of clinical presentation, etiology, pathogenesis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2014) 71:787–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.019

3. Braghiroli, CS, Ieiri, R, Ocanha, JP, Paschoalini, RB, and Miot, HA. Do you know this syndrome? Hand-foot syndrome. An Bras Dermatol. (2017) 92:131–3. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20174602

4. Nagore, E, Insa, A, and Sanmartín, O. Antineoplastic therapy-induced palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia ('hand-foot') syndrome. Incidence, recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. (2000) 1:225–34. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200001040-00004

5. Degen, A, Alter, M, Schenck, F, Satzger, I, Völker, B, Kapp, A, et al. The hand-foot-syndrome associated with medical tumor therapy - classification and management. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. (2010) 8:652–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2010.07449.x

6. Lassere, Y, and Hoff, P. Management of hand-foot syndrome in patients treated with capecitabine (Xeloda). Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2004) 8:S31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2004.06.007

7. Zhang, RX, Wu, XJ, Wan, DS, Lu, ZH, Kong, LH, Pan, ZZ, et al. Celecoxib can prevent capecitabine-related hand-foot syndrome in stage II and III colorectal cancer patients: result of a single-center, prospective randomized phase III trial. Ann Oncol. (2012) 23:1348–53. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr400

8. Elyasi, S, Shojaee, FSR, Allahyari, A, and Karimi, G. Topical silymarin administration for prevention of capecitabine-induced hand-foot syndrome: a randomized, double-blinded, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Phytother Res. (2017) 31:1323–9. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5857

9. Lee, J, and Bielory, L. Complementary and alternative interventions in atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. (2010) 30:411–24. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2010.06.006

10. Deng, B, and Sun, W. Herbal medicine for hand-foot syndrome induced by fluoropyrimidines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytother Res. (2018) 32:1211–28. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6068

11. Di, H, Liu, H, Xu, S, Yi, N, and Wei, G. Network pharmacology and experimental validation to explore the molecular mechanisms of compound Huangbai liquid for the treatment of acne. Drug Des Devel Ther. (2023) 17:39–53. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S385208

12. Liu, G, Rajesh, N, Wang, X, Zhang, M, Wu, Q, Li, S, et al. Identification of flavonoids in the stems and leaves of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. (2011) 879:1023–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.02.050

13. Zhi, H, Jin, X, Zhu, H, Li, H, Zhang, Y, Lu, Y, et al. Exploring the effective materials of flavonoids-enriched extract from Scutellaria baicalensis roots based on the metabolic activation in influenza a virus induced acute lung injury. J Pharm Biomed Anal. (2020) 177:112876. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2019.112876

14. Yoon, SB, Lee, YJ, Park, SK, Kim, HC, Bae, H, Kim, HM, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Scutellaria baicalensis water extract on LPS-activated RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Ethnopharmacol. (2009) 125:286–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.06.027

15. Cole, IB, Cao, J, Alan, AR, Saxena, PK, and Murch, SJ. Comparisons of Scutellaria baicalensis, Scutellaria lateriflora and Scutellaria racemosa: genome size, antioxidant potential and phytochemistry. Planta Med. (2008) 74:474–81. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1034358

16. Han, YK, Kim, H, Shin, H, Song, J, Lee, MK, Park, B, et al. Characterization of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant constituents from Scutellaria baicalensis using LC-MS coupled with a bioassay method. Molecules. (2020) 25:617. doi: 10.3390/molecules25163617

17. Kim, JM, Jung, HA, Choi, JS, and Lee, NG. Identification of anti-inflammatory target genes of Rhizoma coptidis extract in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW264.7 murine macrophage-like cells. J Ethnopharmacol. (2010) 130:354–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.05.022

18. Liu, H, Chen, YF, Li, F, and Zhang, HY. Fructus Gardenia (Gardenia jasminoides J. Ellis) phytochemistry, pharmacology of cardiovascular, and safety with the perspective of new drugs development. J Asian Nat Prod Res. (2013) 15:94–110. doi: 10.1080/10286020.2012.723203

19. Chen, L, Li, M, Yang, Z, Tao, W, Wang, P, Tian, X, et al. Gardenia jasminoides Ellis: Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, and pharmacological and industrial applications of an important traditional Chinese medicine. J Ethnopharmacol. (2020) 257:112829. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112829

20. Yuan, J, Zhang, J, Cao, J, Wang, G, and Bai, H. Geniposide alleviates traumatic brain injury in rats via anti-inflammatory effect and MAPK/NF-kB inhibition. Cell Mol Neurobiol. (2020) 40:511–20. doi: 10.1007/s10571-019-00749-6

21. Chen, XY, Jiang, WW, Liu, YL, Ma, ZX, and Dai, JQ. Anti-inflammatory action of geniposide promotes wound healing in diabetic rats. Pharm Biol. (2022) 60:294–9. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2022.2030760

23. Li, S, and Zhang, B. Traditional Chinese medicine network pharmacology: theory, methodology and application. Chin J Nat Med. (2013) 11:110–20. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(13)60037-0

24. Srivastava, AK, Wang, Y, Huang, R, Skinner, C, Thompson, T, Pollard, L, et al. Human genome meeting 2016: Houston, TX, USA. 28 February −2 march 2016. Hum Genomics. (2016) 10:12. doi: 10.1186/s40246-016-0063-5

25. Itamoto, S, Imafuku, K, Miyazawa, H, Anan, T, Matsumiya, H, Endo, D, et al. Hand-foot syndrome histopathologically presenting eccrine squamous syringometaplasia due to pembrolizumab after lenvatinib treatment. J Cutan Pathol. (2023) 50:932–5. doi: 10.1111/cup.14493

26. Abushullaih, S, Saad, ED, Munsell, M, and Hoff, PM. Incidence and severity of hand-foot syndrome in colorectal cancer patients treated with capecitabine: a single-institution experience. Cancer Investig. (2002) 20:3–10. doi: 10.1081/CNV-120000360

27. Griffin, JI, Wang, G, Smith, WJ, Vu, VP, Scheinman, R, Stitch, D, et al. Revealing dynamics of accumulation of systemically injected liposomes in the skin by Intravital microscopy. ACS Nano. (2017) 11:11584–93. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b06524

28. Zhang, M, Swarts, SG, Yin, L, Liu, C, Tian, Y, Cao, Y, et al. Antioxidant properties of quercetin. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2011) 701:283–9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-7756-4_38

29. Shen, W, Liu, Q, Li, C, Abula, M, Yang, Z, Wang, Z, et al. Exploration of the effect and potential mechanism of quercetin in repairing spinal cord injury based on network pharmacology and in vivo experimental verification. Heliyon. (2023) 9:e20024. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20024

30. Calderón-Montaño, JM, Burgos-Morón, E, Pérez-Guerrero, C, and López-Lázaro, M. A review on the dietary flavonoid kaempferol. Mini Rev Med Chem. (2011) 11:298–344. doi: 10.2174/138955711795305335

31. Yang, MF, Li, H, Xu, XR, Zhang, QY, Wang, TY, Feng, L, et al. Comprehensive identification of metabolites and metabolic characteristics of luteolin and kaempferol in Simiao Yong’an decoction in rats by UHPLC-LTQ-Orbitrap MS/MS. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. (2023) 48:6191–9. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20230621.201

32. Samhan-Arias, AK, Martín-Romero, FJ, and Gutiérrez-Merino, C. Kaempferol blocks oxidative stress in cerebellar granule cells and reveals a key role for reactive oxygen species production at the plasma membrane in the commitment to apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. (2004) 37:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.04.002

33. Zaloga, GP. Phytosterols, lipid administration, and liver disease during parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. (2015) 39:39s–60s. doi: 10.1177/0148607115595978

34. Babu, S, and Jayaraman, S. An update on β-sitosterol: a potential herbal nutraceutical for diabetic management. Biomed Pharmacother. (2020) 131:110702. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110702

35. Sun, Y, Gao, L, Hou, W, and Wu, J. β-Sitosterol alleviates inflammatory response via inhibiting the activation of ERK/p 38 and NF-κB pathways in LPS-exposed BV2 cells. Biomed Res Int. (2020) 2020:7532306. doi: 10.1155/2020/7532306

36. Jie, F, Yang, X, Yang, B, Liu, Y, Wu, L, and Lu, B. Stigmasterol attenuates inflammatory response of microglia via NF-κB and NLRP3 signaling by AMPK activation. Biomed Pharmacother. (2022) 153:113317. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113317

37. Goswami, M, Priya, JS, Gupta, GD, and Verma, SK. A comprehensive update on phytochemistry, analytical aspects, medicinal attributes, specifications and stability of stigmasterol. Steroids. (2023) 196:109244. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2023.109244

38. Ahmad Khan, M, Sarwar, A, Rahat, R, Ahmed, RS, and Umar, S. Stigmasterol protects rats from collagen induced arthritis by inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines. Int Immunopharmacol. (2020) 85:106642. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106642

39. Chong, ZZ, Kang, JQ, and Maiese, K. Essential cellular regulatory elements of oxidative stress in early and late phases of apoptosis in the central nervous system. Antioxid Redox Signal. (2004) 6:277–87. doi: 10.1089/152308604322899341

40. Chong, ZZ, and Maiese, K. Erythropoietin involves the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway, 14-3-3 protein and FOXO3a nuclear trafficking to preserve endothelial cell integrity. Br J Pharmacol. (2007) 150:839–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707161

41. Pastore, S, Mascia, F, Mariani, V, and Girolomoni, G. The epidermal growth factor receptor system in skin repair and inflammation. J Invest Dermatol. (2008) 128:1365–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701184

42. Mascia, F, Mariani, V, Girolomoni, G, and Pastore, S. Blockade of the EGF receptor induces a deranged chemokine expression in keratinocytes leading to enhanced skin inflammation. Am J Pathol. (2003) 163:303–12. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63654-1

43. Sääf, A, Pivarcsi, A, Winge, MC, Wahlgren, CF, Homey, B, Nordenskjöld, M, et al. Characterization of EGFR and ErbB2 expression in atopic dermatitis patients. Arch Dermatol Res. (2012) 304:773–80. doi: 10.1007/s00403-012-1242-4

44. Yuan, TL, Wulf, G, Burga, L, and Cantley, LC. Cell-to-cell variability in PI3K protein level regulates PI3K-AKT pathway activity in cell populations. Curr Biol. (2011) 21:173–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.12.047

45. Shin, JW, Lee, HS, Na, JI, Huh, CH, Park, KC, and Choi, HR. Resveratrol inhibits particulate matter-induced inflammatory responses in human keratinocytes. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:446. doi: 10.3390/ijms21103446

46. Lamb, J, Ramaswamy, S, Ford, HL, Contreras, B, Martinez, RV, Kittrell, FS, et al. A mechanism of cyclin D1 action encoded in the patterns of gene expression in human cancer. Cell. (2003) 114:323–34. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00570-1

47. Guardavaccaro, D, Corrente, G, Covone, F, Micheli, L, D'agnano, I, Starace, G, et al. Arrest of G(1)-S progression by the p53-inducible gene PC3 is Rb dependent and relies on the inhibition of cyclin D1 transcription. Mol Cell Biol. (2000) 20:1797–815. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.5.1797-1815.2000

48. Wang, Q, He, G, Hou, M, Chen, L, Chen, S, Xu, A, et al. Cell cycle regulation by alternative polyadenylation of CCND1. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:6824. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25141-0

49. Xia, H, Ng, SS, Jiang, S, Cheung, WK, Sze, J, Bian, XW, et al. miR-200a-mediated downregulation of ZEB2 and CTNNB1 differentially inhibits nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell growth, migration and invasion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2010) 391:535–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.093

50. Asgari, MM, Haggerty, JG, Mcniff, JM, Milstone, LM, and Schwartz, PM. Expression and localization of thymidine phosphorylase/platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor in skin and cutaneous tumors. J Cutan Pathol. (1999) 26:287–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1999.tb01846.x

51. Farr, KP, and Safwat, A. Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia associated with chemotherapy and its treatment. Case Rep Oncol. (2011) 4:229–35. doi: 10.1159/000327767

52. Wang, W, Wang, Y, Zou, J, Jia, Y, Wang, Y, Li, J, et al. The mechanism action of German chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) in the treatment of eczema: based on dose-effect weight coefficient network pharmacology. Front Pharmacol. (2021) 12:706836. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.706836

53. Hong, S, Lee, B, Kim, JH, Kim, EY, Kim, M, Kwon, B, et al. Solanum nigrum Linne improves DNCB-induced atopic dermatitis-like skin disease in BALB/c mice. Mol Med Rep. (2020) 22:2878–86. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11381

54. Duan, W, and Wong, WS. Targeting mitogen-activated protein kinases for asthma. Curr Drug Targets. (2006) 7:691–8. doi: 10.2174/138945006777435353

55. Sur, B, Kang, S, Kim, M, and Oh, S. Alleviation of atopic dermatitis lesions by a Benzylideneacetophenone derivative via the MAPK signaling pathway. Inflammation. (2019) 42:1093–102. doi: 10.1007/s10753-019-00971-w

56. Aggarwal, BB, Gupta, SC, and Sung, B. Curcumin: an orally bioavailable blocker of TNF and other pro-inflammatory biomarkers. Br J Pharmacol. (2013) 169:1672–92. doi: 10.1111/bph.12131

Keywords: hand-foot syndrome, molecular mechanism, network pharmacology, traditional Chinese medicine, molecular docking

Citation: Li P, Chen L and Liu J (2024) Network pharmacology and molecular docking approach to elucidate the mechanisms of safflower, phellodendron, scutellaria baicalensis, coptis, and gardenia in hand–foot syndrome. Front. Med. 11:1454776. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1454776

Received: 25 June 2024; Accepted: 03 September 2024;

Published: 16 September 2024.

Edited by:

Mithun Rudrapal, Vignan’s Foundation for Science, Technology and Research, IndiaReviewed by:

Manish Kumar Tripathi, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, IndiaCopyright © 2024 Li, Chen and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jianhui Liu, MzY0MTMyMDU0MEBxcS5jb20=; Lizhu Chen, eWlkdW95dW4wMzdAZmptdS5lZHUuY24=

†ORCID: Pengxing Li, https://orcid.org/0009-0001-3432-0892

Lizhu Chen, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9881-2976

Jianhui Liu, https://orcid.org/0009-0006-4112-5194

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.