- 1Department of Medical Oncology, St Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

- 2Department of Medical Oncology, St James’s Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

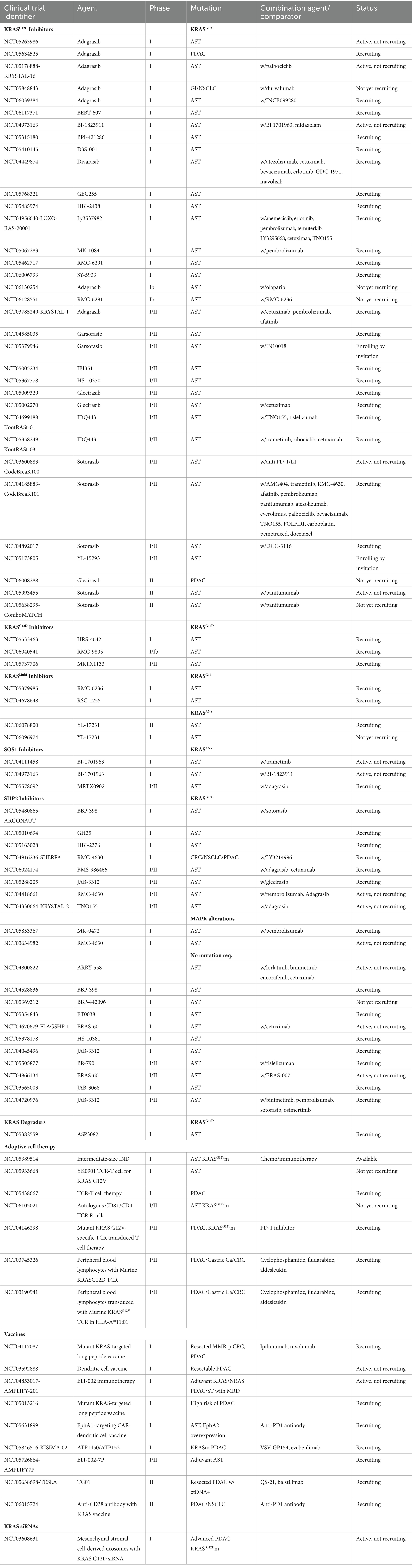

- 3Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada

Targeting the RAS pathway remains the holy grail of precision oncology. In the case of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDAC), 90–92% harbor mutations in the oncogene KRAS, triggering canonical MAPK signaling. The smooth structure of the altered KRAS protein without a binding pocket and its affinity for GTP have, in the past, hampered drug development. The emergence of KRASG12C covalent inhibitors has provided renewed enthusiasm for targeting KRAS. The numerous pathways implicated in RAS activation do, however, lead to the development of early resistance. In addition, the dense stromal niche and immunosuppressive microenvironment dictated by oncogenic KRAS can influence treatment responses, highlighting the need for a combination-based approach. Given that mutations in KRAS occur early in PDAC tumorigenesis, an understanding of its pleiotropic effects is key to progress in this disease. Herein, we review current perspectives on targeting KRAS with a focus on PDAC.

Introduction

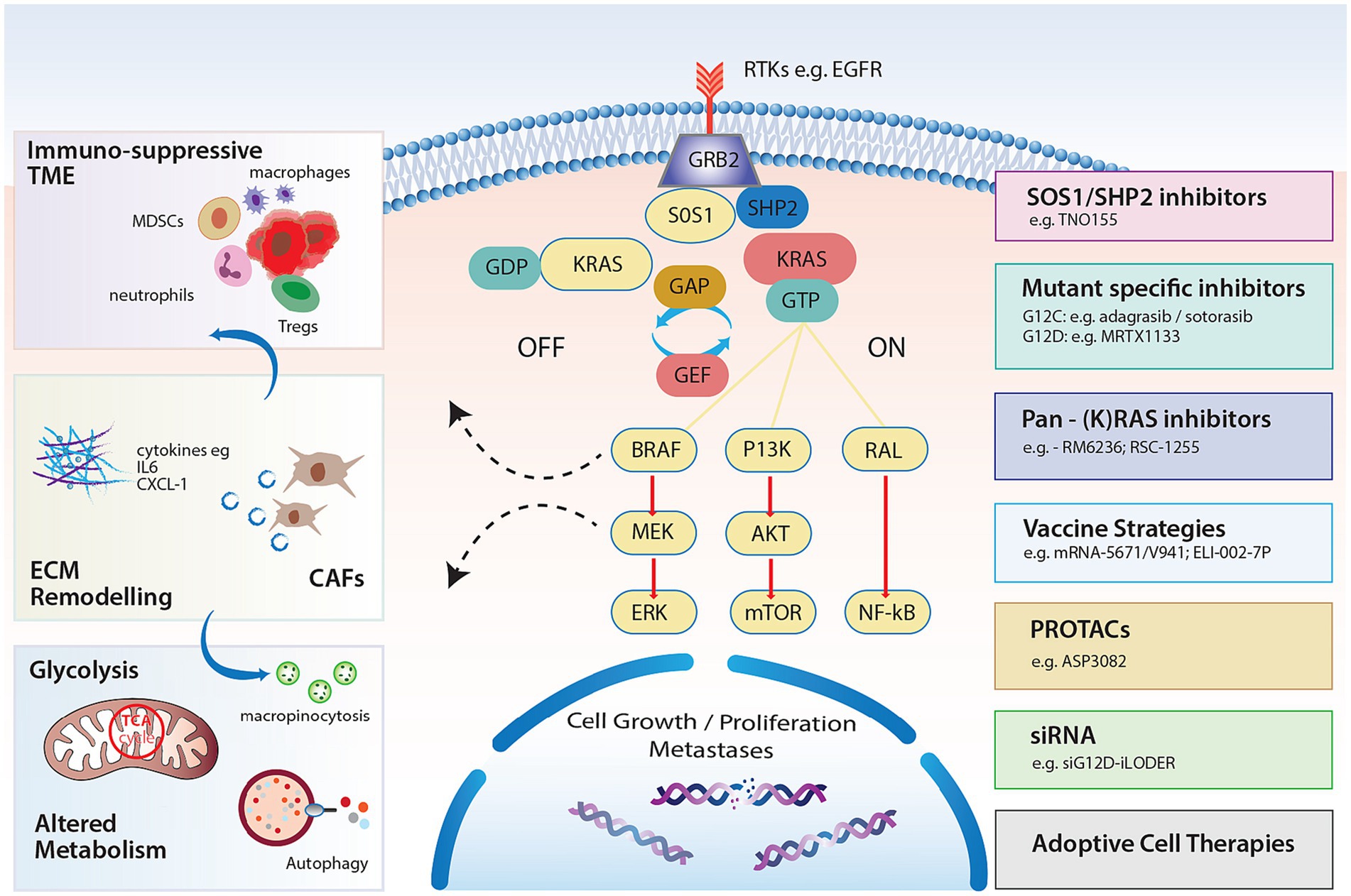

The Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene (KRAS) encodes the protein KRAS and represents the most altered protein across solid tumors underscoring the need for successful targeting (1). KRAS which is anchored as a membrane-bound protein in all human cells, acts as a central node for multiple signaling pathways important in normal cellular function (2). KRAS cycles between its inactive and active forms, facilitated by the exchange of KRAS-bound guanine diphosphate (GDP) and guanine triphosphate (GTP). Guanine exchange factors (GEFs) and GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) orchestrate this exchange and are therefore critical in maintaining KRAS activity (Figure 1). This well-controlled cycle was long considered ‘undruggable’ due to two main factors: the high affinity of KRAS for GTP and the absence of appropriate binding pockets suitable for the development of small molecule inhibitors (3, 4). The last 10 years have heralded a new era in personalized medicine with the discovery of the covalent KRASG12C inhibitors and a plethora of new investigational KRAS targeting agents are now entering the clinic. Innate and acquired resistance mechanisms to KRAS inhibitors have already been documented and our understanding of the pleiotropic effects of oncogenic KRAS on the tumor microenvironment has evolved. This has opened up new avenues in the treatment of KRAS mutated tumors with combination-based approaches in addition to emerging vaccines and adoptive cell therapy (ACT) strategies. Although oncology has seen the evolution of agnostic biomarkers to facilitate precise approaches, it remains to be seen whether mutations in the KRAS gene will represent universal biomarkers or whether inhibitor effects will be cell lineage dependent. In particular, pancreatic cancer has been a global challenge from a therapeutic perspective. Herein, we review approaches to KRAS targeting in pancreatic cancer to date and suggest some challenges for the future.

Figure 1. KRAS signaling pathways and impact on the TME, stroma and metabolism with strategies to target RAS.

KRAS signaling

KRAS is located on the short arm of chromosome 12 and is a member of the RAS oncogene family along with 2 other isoforms, neuroblastoma rat sarcoma viral oncogene (NRAS) and Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene (HRAS) (chromosomes 1 and 11 respectively) (5). KRAS is composed of 2 major domains, a catalytic domain called the G domain, and a hypervariable region at the C-terminal (6). The G domain consists of 3 regions: switch I, switch II and the P loop. Notably, as KRAS cycles between active and inactive states, the switch I and II pockets alter their conformation, providing a therapeutic vulnerability.

In the resting state, KRAS binds to GDP, which does not activate downstream signaling and is therefore considered “OFF.” GEFs limit KRAS-GDP affinity and act to replace GDP for GTP when activated by extracellular signals in the form of growth factors, e.g., epidermal growth factor (EGF), cytokines, and other molecules (Figure 1). Son of sevenless 1 and 2 (SOS1/SOS2), growth factor receptor-bound protein (GRB2) and RAS protein-specific guanine nucleotide-releasing factor 2 (RASGRF2) are common GEFs that enable the exchange (7). Src homology-2 domain containing protein tyrosine phosphatase (SHP2), which is considered a scaffolding protein, facilitates the GRB2/SOS1 complex at the cell membrane through direct binding to GRB2, promoting KRAS activation (8).

When KRAS is bound to GTP, it is considered “ON,” activating downstream signaling cascades. To convert back to the “OFF” state, KRAS-GTP must undergo hydrolysis. Intrinsic hydrolysis of GTPases is relatively ineffective and requires the assistance of GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) such as neurofibrin-1 (NF1) or p120-RasGAP protein (encoded by RASA1) (9).

When GTP-bound, subsequent interaction with RAS-binding domains (RBDs) of effector proteins permits downstream signaling (10). The three major RAS effectors include rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma (RAF) proteins, ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator (RALGDS) and the phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks) (Figure 1). Perhaps the most notable interaction is the activation of the mitogen activated protein kinase pathway (MAPK) RAF–MEK–ERK pathway. Activated KRAS ignites phosphorylation of RAF and subsequently extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) 1 and 2 following RAF dimerization (11). Phosphorylation of ERK results in ERK translocation to the nucleus where further transcriptional factors are phosphorylated and cell cycle progression through G0/G1 mitogenic signals ensues (12). Notably, the degree of activation of RAF kinases is likely variable which may influence prognostic outcomes of different mutated alleles (13).

Cellular growth and proliferation also result from signaling through the PI3K/protein kinase B(AKT) pathway. Activated PI3K phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol(PIP)2 to PIP3 promoting AKT phosphorylation which in turn stimulates many downstream pathways and regulates cell proliferation, cell death and metabolic processes, including cellular responses to insulin (14). Interactions with mTOR target proteins via feedback phosphorylation promote cell proliferation but also activate Bcl-XL/Bcl-2 to facilitate apoptosis (15, 16). The third major effector of RAS is the Ral guanine nucleotide exchange factor pathway. Ral proteins (RalA and RalB) are GTPases also cycling between GDP and GTP bound states. This effector of RAS complements RAS/RAF and RAS/PI3K signaling and is known to stimulate the Jun-N terminal kinase pathway promoting cell migration and proliferation (17).

Altered KRAS signaling

Mutations

Oncogenic mutations in KRAS typically occur at hotspots in the protein with 95% occurring in codons 12, 13, and 61 (18). In pancreatic cancer the most common mutations occur on codon 12 with a single amino acid missense mutation when a glycine (G) is replaced by aspartate (G12D, 40%), valine (G12V, 29%), arginine (G12R, 15%), and cystine (G12C ~1%) (19). Less common mutations include G13 and Q61. KRASQ61H is found in about 5% of pancreatic cancer and is selectively associated with increased survival (20, 21). In contrast, KRASG12D has been associated with worse outcomes (22).

Mutations in KRAS increase KRAS-GTP affinity and the conformational changes inhibit GAP-mediated hydrolysis while also ensuring resistance to intrinsic GTPase activity (23, 24). In fact, it is thought that mutated KRAS may be more reliant on intrinsic rather than GAP-mediated hydrolysis to achieve its off state. Importantly, there are distinct biological differences in mutated KRAS forms. Mutations in codons 12 and 61 are insensitive to NF-1 mediated hydrolysis (25) and KRASG12C mutations demonstrate intrinsic GTPase activity similar to wild-type KRAS allowing for cycling between GDP and GTP bound states (23). In evaluating G12 mutants, higher intrinsic GTPase activity has been shown in G12D and G12C compared to G12R and G12V (23).

The etiology of some KRAS mutant cancers are distinct, e.g., G12C is the most common KRAS mutation in smoking-associated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (26). However, associations with epidemiologic risk factors have not been documented in PDAC.

KRAS amplification

Abnormal KRAS signaling in cancer can also be identified through high-level amplification of the KRAS gene. This is the fourth most common KRAS alteration that occurs and is evident in esophageal, stomach and serous ovarian cancer, generally representing an aggressive subtype (27, 28). Moreover, KRAS amplification permits adaptive resistance to MAPK inhibition and highlights the need for combination approaches (28). In pancreatic cancer, the dosage of mutant KRAS underpins particularly aggressive phenotypes (29). Major imbalances in mutant versus wild-type KRAS reflect the basal-like subtype and are associated with an inferior outcome in both resected and advanced PDAC (29, 30). This phenotype of PDAC is more evident in metastases than primaries and polyploid tumors, suggesting that evolutionary components to PDAC progression dictate more aggressive subtypes.

Common co-mutations

In pancreatic cancer, KRAS mutations commonly occur alongside inactivating mutations in tumor suppressor genes such as TP53, CDKN2A, and SMAD4 (31). Sequential inactivation of these genes is important in the evolution of invasive disease (32). This inactivation contributes to the heterogeneous nature of KRAS mutated PDAC with the number of drivers influencing survival (22, 33). Co-mutations in STK11 and the PIK3/AKT/mTOR pathway further contribute to inferior outcomes (34).

KRAS and progression to invasive PDAC

There are two predominant precursor lesions to invasive PDAC, namely pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) (85–90%) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) (10–15%). KRAS mutations are evident even in low-grade PanIN highlighting its principal role early in oncogenesis but also underscoring the need for the acquisition of co-mutations for invasive disease to develop. Indeed a stepwise model for progression has long been accepted (35, 36), although alternate models propose large-scale chromothriptic events which permit rapid disease progression, bypassing traditional models (37). Increasing knowledge of the malignant potential of cystic lesions, which are readily apparent on imaging, has revealed recurrent genetic drivers in KRAS, GNAS and RNF43, with additional alterations seen in invasive disease (38–40). With the successive inactivation of tumor suppressors in PDAC, cell cycle progression increases, as measured by RNA sequencing or Ki-67 (41). Transcriptional subtypes from primaries and metastases document major classifiers as basal-like and classical, with hybrid phenotypes evident which suggests tumoral plasticity. Although the incidence of the basal-like subtype is more apparent in metastases and associates with major imbalances in mutant KRAS, it is not yet clear what drives the progression to this phenotype. The influence of the tumor microenvironment (TME) and epigenetic factors are likely to be important. A full understanding of the progression of precursor lesions to invasive disease will underpin where KRAS can be targeted and what combination strategies may be needed.

Impact of KRAS signaling on the tumor microenvironment and stroma

PDAC harbors a unique tumoral niche characterized by a dense fibrotic stromal reaction and an immunosuppressive TME. Infiltration of immunosuppressive cells, encouraging immune evasion, is thought to occur early, highlighting the cell-extrinsic impacts of KRAS mutations (41, 42). In fact, it has been well documented in the genetically engineered KPC (Kras LSL-G12D/+Trp53LSL-R172H/+ Pdx-Cre) and KC mouse (KrasLSL-G12D/+ Pdx-Cre) models, that KRAS mutations in PanIN lesions associate with inflammatory environments with overexpression of COX2 (42), and early infiltration of T regulatory cells (Tregs), Tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) and Myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). This indicates a shift toward early immune evasion (43) and KRAS mutations induce multiple cytokines to promote and maintain this tumor promoting environment in invasive disease. RAS mutations induce the secretion of IL-6 in different cell types including myeloid cells, resulting in JAK1 activation and phosphorylation of the STAT3 pathway, culminating in a pro-inflammatory TME and shifting homeostasis toward tumorigenesis (44–46). Additionally, granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) secretion in response to mutated KRAS, can occur early and promotes MDSC infiltration, restricting anti-tumor immunity (47, 48). Moreover, continued secretion by mesenchymal stem cells within the stroma encourages tumor invasion and metastasis formation (49, 50) (Figure 1). Pivotal studies have demonstrated the upregulation of chemokines including CXCL-8 (IL-8) (51) and CXCR2 (52, 53) in response to RAS signaling, together with transcription factors such as NF-κB, promoting inflammation (54). Immune escape is further reinforced through the upregulation of PD-L1 and the conversion of CD4+ cells to Tregs (55). The latter is enhanced following ERK activation and secretion of IL-10 and TGF-B1, illustrating the importance of downstream pathways in shaping the TME (55). Nevertheless, the presence of a distinct chemokine signature (CCL4, CCL5, CXCL9, CXCL-10) can associate with T cell infiltration (56), and represents a biomarker of response to immune checkpoint inhibitor combinations in certain PDAC genotypes (57). This highlights the potential importance of profiling the TME for combination approaches.

The characteristic desmoplasia of PDAC is inherently reliant on cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) with varying CAF subtypes identified (58). It is now known that targeting stroma may accelerate PDAC progression. The origin of CAFs remains unclear with a minority produced from the pancreatic stellate cell (59). Immunosuppressive and immune-enhancing CAFs exist (60), however oncogenic KRAS promotes non-cell autonomous programming of CAFs to stimulate cytokines, which regulate MDSCs and other immune cells (61). Understanding the pleiotropic effects of KRAS mutations in molding the TME early in oncogenesis will be critical in trial design of combination approaches in PDAC. Notably, the unselected use of immune checkpoint inhibitors has been unsuccessful to date (62).

Metabolic impact on KRAS mutations

Cancer cell metabolism is critical to survival and in PDAC, KRAS mutations shape a unique metabolic environment which drives aerobic glycolysis (63). The adaptive switch to produce glucose, glutamine and fatty acids facilitates a supply for growth and proliferation. Notably, RAS-dependent metabolic adaption is likely tumor-specific, owing to the prevalence of specific KRAS mutations (64, 65). Mutations in KRAS are known to upregulate the GLUT1 transporter together with induction of enzymatic activity to increase glycolysis (66). Glutaminolysis also increases in the presence of oncogenic RAS signaling, providing glutamate from glutamine, fuelling tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) and providing a pool of amino acids (67, 68). Nutrient scavenging pathways such as autophagy are known to be upregulated in PDAC (69), and continue to feed the TCA cycle sustaining growth (70). Targeting autophagy has been a huge therapeutic strategy in the last number of years with multiple trials ongoing with hydroxychloroquine. Studies have shown that targeting RAS effector pathways such as ERK signaling may increase reliance on autophagy, necessitating combination approaches (71). Macropinocytosis is an additional metabolic process where cells can engulf extracellular material and is thought essential for PDAC survival (72, 73). The transcription factor MYC is important in this pathway, and notably, recent work has established mechanistic differences in macropinocytosis according to the mutant allele. KRASG12R exhibits impaired activation of the effector p110alpha PI3K, exposing potential therapeutic vulnerabilities (64). The crosstalk between KRAS, the TME and metabolic pathways will be critical in advancing combination therapeutic strategies, especially given the recent disappointments in targeting metabolism in the AVENGER trial (74).

Current KRAS targets

Allele-specific KRAS inhibitors

Direct G12C inhibitors

To date, progress in the field has been dominated by KRASG12C inhibitors, however, KRASG12C only represents approximately 1% of PDAC KRAS mutations (75). The direct G12C inhibitors bind covalently to the mutant cysteine, occupying the switch II pocket, trapping KRASG12C in the inactive, GDP-bound or “OFF” state (76).

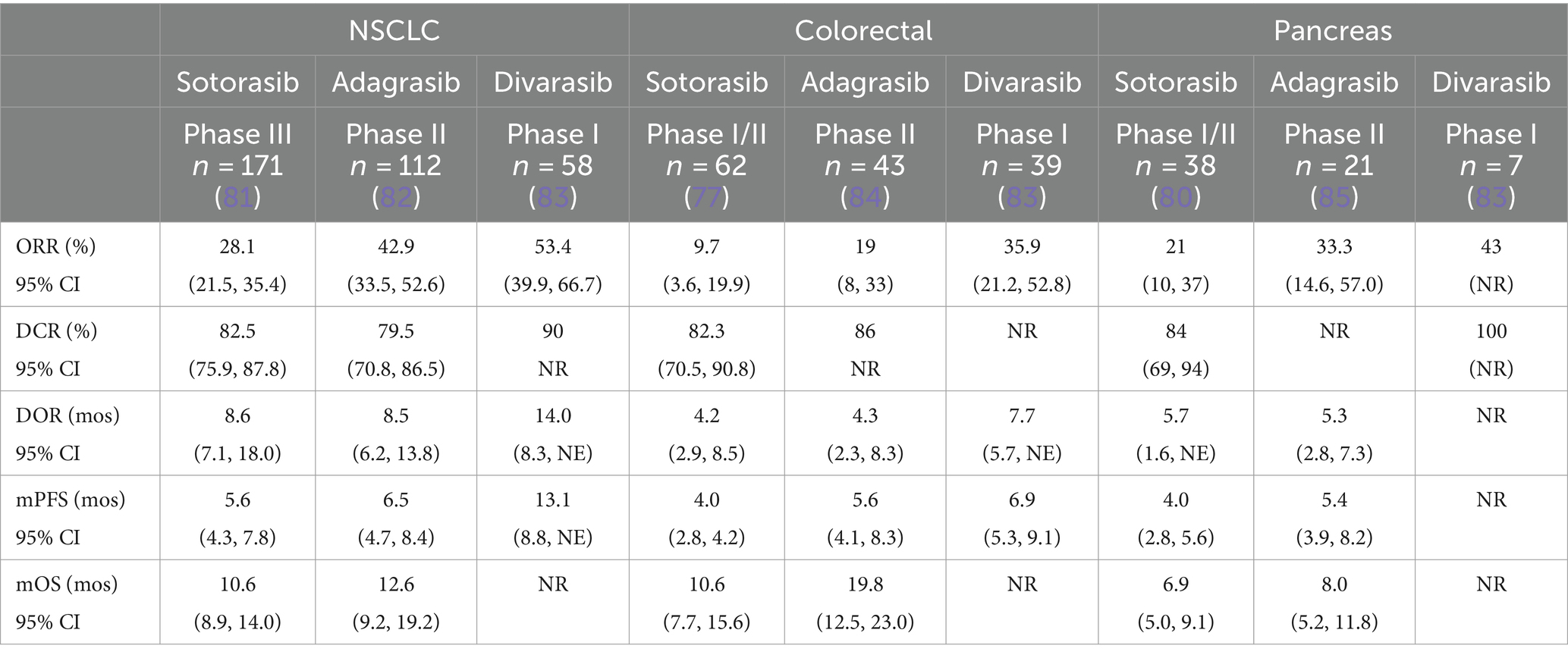

Sotorasib (AMG-510) was the first direct KRASG12C inhibitor to enter the clinical arena. It is an oral small-molecule inhibitor that selectively and irreversibly targets KRASG12C and has been FDA-approved for the treatment of advanced NSCLC, based on the phase II CodeBreaK-100 trial. Patients with KRASG12C mutated NSCLC (n = 126) were treated with sotorasib 960 mg OD and achieved an objective response rate (ORR) of 37.1% (95% CI, 28.6–46.1), with a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 6.8 months (95% CI, 5.1–8.2) (4). The response in KRASG12C mutated colorectal cancer is notably inferior, with an ORR of just 9.7% (95% CI 3.6–19.1) seen in this cohort of the CodeBreaK-100 trial (77). This improved to 30% (95% CI, 16.6–46.5) in the phase Ib CodeBreaK-101 trial with the addition of panitumumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (78). A further improvement was seen with the combination of sotorasib, panitumumab and FOLFIRI (5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and irinotecan) in which 58.1% (95% CI, 39.1–75.5) had an objective response (79). The activity of sotorasib in advanced PDAC harboring KRASG12C has been disappointing thus far. The phase I/II CodeBreaK-100 trials included 38 patients with advanced PDAC and demonstrated an ORR of 21% (95% CI, 10–37) with a disease control rate (DCR) of 84.2% (95% CI, 68.7–93.9). The median PFS was 4.0 months (95% CI 2.8–5.6) with a median overall survival (OS) of 6.9 months (95% CI 5.0–9.1) (80) (Table 1).

Table 1. Response to single agent KRAS G12C inhibition in NSCLC, colorectal cancer and pancreatic cancer.

Adagrasib (MRTX849), another direct KRASG12C inhibitor with a longer half-life than sotorasib at 23 h, is dosed at 600 mg BD based on dose escalation in the phase I KRYSTAL-1 trial (86). The twice-daily dosing may have contributed to the improved response rates in NSCLC and colorectal cancer compared with sotorasib, at 42.9% (95% CI, 33.5–52.6) and 19% (8/43) respectively (82, 84). Again, the addition of an EGFR inhibitor cetuximab, improved the ORR in the colorectal cohort to 46% (95% CI 8–33) and demonstrated an increase in duration of response from 4.3 months (95% CI 2.3–8.3) to 7.6 months (95% CI 5.7-not estimable) (84). There were also improved responses in the PDAC cohort of the phase I/II KRYSTAL-1 trial (n = 21) with an ORR of 33.3% (95% CI 14.6–57.0) and a DCR of 81% (17/21). The median PFS was 5.4 months (95% CI, 3.9–8.2) and OS 8.0 months (95% CI 5.2–11.8) (85).

Divarasib (GDC-6036), a KRASG12C inhibitor which has increased potency and selectivity relative to sotorasib and adagrasib, has demonstrated superior response rates in a phase I trial of 137 patients with advanced KRASG12C mutated solid tumors (83). Treatment with divarasib resulted in an ORR of 53.4% (95% CI, 39.9–66.7) in NSCLC and 29.1% (95% CI 17.6–42.9) in colorectal cancer (Table 1). There were 7 patients with PDAC included in the trial, and of these, 3 (43%) experienced an objective response and 4 (57%) recorded stable disease (83).

Safety and efficacy data of multiple other compounds targeting KRASG12C has been presented in the past 12 months. This includes MK-1084, Garsorasib, JDQ443 (target GDP-bound KRAS) and IBI351 (targets GDP/GTP exchange). These have not yet reported data on PDAC cohorts. The LOXO-RAS-20001 trial of LY3537982 (targets GDP-bound KRAS) in KRASG12C mutated advanced solid tumors included 8 patients with PDAC and reported an ORR of 38% (87). RMC-6291 is a tricomplex inhibitor which acts similarly to the immunosuppressant cyclosporin by binding to cyclophilin A, targeting the GTP-bound state. It has shown promise in NSCLC including a partial response in 50% who had been previously treated with a KRAS inhibitor (88). These compounds may overcome resistance to GDP-bound inhibitors which can acquire secondary resistance mutations (89). There are numerous clinical trials of KRASG12C inhibitor agents ongoing (Table 2).

Non-G12C allele-specific inhibitors

Given that G12D, G12V, and G12R represent over 90% of KRAS mutations in pancreatic cancer, an effective therapy for these cancers represents a significant unmet need.

There are multiple drugs targeting KRASG12D in development, with clinical trials for three compounds currently enrolling (Table 2). MRTX1133 is a selective, noncovalent G12D inhibitor which binds ionically to the aspartate 12 residue, inhibiting both the inactive and active states of KRASG12D (3). It is highly selective with a 700-fold affinity for KRASG12D versus wild-type (90) and has shown promising efficacy in mouse models with KRASG12D mutations, with >30% tumor regression in 8 of 11 PDAC models (90). The safety and efficacy profile of HRS-4642, a highly selective G12D inhibitor has been reported in a phase 1 trial of 18 patients, 15 of whom had NSCLC or CRC with an ORR of 33.3% (91). Furthermore, RMC-9805, another tricomplex inhibitor which targets the GTP-bound “ON” state of KRASG12D has shown promising preclinical results and studies have suggested synergy with immunotherapy (92). Other small molecules in development include TH-Z835, which forms a salt bridge with the aspartate 12 residue and binds to both inactive and active forms (93). This has shown encouraging efficacy in pancreatic mouse models however, the unintended side effect of weight loss suggests off-target effects.

Pan-RAS inhibitors

In 2023, the first tri-complex pan-RAS inhibitor RMC-(94)6236 announced initial results from a phase I trial in PDAC and NSCLC (Table 2). Across multiple doses, the ORR in 46 heavily pre-treated PDAC patients was 20% with a DCR of 87%. The median time to response was 1.4 months (1.2–4.4 months) and median time on treatment was 3.3 months (0.2–10.9 months). Notably, in 12/13 PDAC patients circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analyses revealed >50% reduction in the mutated allele (94). Importantly, the drug was well tolerated with most treatment related adverse events (TRAEs), grade 1–2. RMC-6236 has demonstrated pre-clinical activity with immune checkpoint inhibitors and may overcome RAS oncogene switch resistance mutations (95). A related compound, RMC-7977 has shown broad-spectrum activity against both mutant and wild-type KRAS cell lines (96).

Additional pan-RAS inhibitors include the nanomolar compound BI-2852 which targets a second pocket at the switch I/II position and inhibits all three RAS isoforms (97). BI-2865 is a non-covalent inhibitor which binds to the GDP-bound state of a range of KRAS mutants while sparing HRAS and NRAS, suppressing growth in KRAS mutant tumors in mice (98). A further compound, RSC-1255 binds to vacuolar ATPase, inhibiting autophagy and macropinocytosis, and selectively destroying KRAS/BRAF mutant cells, in particular, KRASG13D and KRASG12V mutated cells (99). Clinical trials in progress of pan-RAS inhibitors are shown in Table 2.

SOS1 and SHP2 inhibitors

The first small molecule SOS1 inhibitor to make it to the clinical setting is BI1701963, a derivative of BI-3406. It binds to the catalytic domain of SOS1 and prevents activation of KRAS without affecting SOS2-mediated signaling (100). In a phase I trial of 31 patients with KRAS mutated solid tumors, it was tolerable and showed stable disease in 7/31 patients at 18 months (101). Toxicity with these agents is a challenge and multiple trials have been terminated or stopped early by the sponsor (NCT04835714, NCT0462714) (102).

There is a plethora of SHP2 inhibitors currently at the clinical trial stage; many of these are first-in-human trials and yet to report (Table 2). A tri-complex SHP2 inhibitor, RMC-4630, demonstrated a disease control rate of 71% (5/7) and a reduction in tumor volume in 43% (3/7) in a small number of patients with KRASG12C mutated NSCLC (103). Subsequent analysis of ctDNA in this trial showed a decrease in KRASG12C variant allele frequency in 5/9 (59%) of patients who had detectable ctDNA at trial commencement, and this was associated with treatment response. Reduction in ctDNA was not seen in patients with KRASG12D or KRASG12V mutated tumors, therefore its potency as a single agent in pancreas cancer is uncertain (104). Clinical efficacy has been documented with TNO155, a pyrazine allosteric SHP2 inhibitor. In a phase I dose-finding study, 118 patients with advanced solid tumors were treated with TNO-155 with 20% experiencing stable disease (105). Preliminary results from the FLAGSHP-1 study, analyzing the SHP2 inhibitor ERAS-601 in advanced solid tumors were disappointing, with a partial response seen in 1/27 patients treated (106). These results suggest that SHP2 inhibitors may need to be used in combination to be effective. Notably, KRASG12R mutant and KRASQ61 mutant tumors appear less sensitive to SOS1 inhibition and SHP2 inhibition (107).

Combination strategies

Combination with upstream inhibitors

Combination strategies are likely necessary to overcome the rapid acquisition of resistance and modest duration of response of direct KRAS inhibitors. Obtaining a sustained clinical response to direct KRAS inhibitors may require targeting GEFs by blocking receptor tyrosine kinases/SHP2/SOS1 or mitigating feedback activation of the pathway. Co-inhibition of KRASG12C and SHP2 has been shown to drive sustained RAS suppression and improve efficacy in vitro and in vivo (108). Jacobio et al. recently reported initial results from a phase I/IIa study of JAB-3312 in combination with the KRASG12C inhibitor glecirasib in patients with KRASG12C mutated solid tumors (109). In 28 patients with treatment-naïve NSCLC, ORR was 50% (14/28), with 100% DCR. A cohort of patients who had previous treatment with a KRASG12C inhibitor demonstrated an ORR of 14.3% (1/7). Tolerability will be critical here and the rate of Grade 3 and 4 TRAEs was notable at 36.7%.

Combination with downstream inhibitors

Simultaneous blockade of downstream effectors to mitigate feedback activation and overcome resistance pathways is another potential combination strategy. There are ongoing clinical trials of direct KRASG12C inhibitors in combination with MEK and ERK inhibitors though preclinical evidence seems stronger for upstream inhibition (108). Moreover, inhibition of parallel pathway (e.g., PI3K/Akt/mTOR) downstream effectors may work more effectively. Preclinical evidence shows mTORC and KRASG12C inhibitors acted synergistically to increase cell death in mouse models (110). This will be further explored in clinical trials of sotorasib and the mTOR inhibitor, everolimus and adagrasib and the PIK3CA inhibitor, INCB099280 (Table 2).

Combination with immunotherapy

Exploratory results from major immunotherapy trials have indicated that KRAS status impacts on response to checkpoint inhibition. In the KEYNOTE-042 and CA209-057 trials, patients with KRAS mutated tumors had superior responses to single-agent pembrolizumab and nivolumab, respectively, compared with KRAS wild-type (111, 112). However, this effect may have been dominated by KRASG12C mutations which respond more favorably to checkpoint inhibition than other KRAS mutations (113). Trials of checkpoint inhibition in PDAC have so far been unsuccessful, however, preclinical studies suggest that a rationale for combination with KRAS-directed therapies. KRASG12D inhibition with MRTX1133 alters the TME which may contribute to the anti-tumor effect with a reduction in myeloid cells, MDSCs and dendritic cells, an increase in M1/M2 macrophage ratio and stimulation of T cell infiltration (114). While the combination of sotorasib with immunotherapy (pembrolizumab or atezolizumab) resulted in a significant rate of hepatotoxicity (115), the addition of pembrolizumab to adagrasib in the KRYSTAL-07 trial appeared to increase response rates (ORR 49%) with an acceptable toxicity profile (116). Furthermore, SHP2 acts with the receptor PD-1 to have an immunomodulatory effect on T cells, therefore the combination of SHP2 with PD-1 inhibitor is promising and several clinical trials are ongoing (Table 2).

Combination with other agents

Co-occurring inactivating mutations in the tumor suppressor CDKN2A result in the depletion of the cell cycle inhibitory protein p16INK4a. It was therefore hoped that CDK4/6 inhibitors, which act to chemically restore the function of p16INK4a, would be effective. The clinical response to CDK4/6 inhibitors in PDAC has been disappointing thus far, however, there is emerging evidence that a combination approach with MAPK inhibition may be efficacious. In preclinical PDAC mouse models, downstream MAPK inhibition with the MEK inhibitor, trametinib in combination with CKD4/6 inhibitor, palbociclib induced a senescent state, inhibiting PDAC growth (117). This senescent phenotype resulted in a modified TME with enhanced tumor vascularisation and increased levels of CD8+ cells, which may point to synergistic effects with chemoimmunotherapeutic strategies. Moreover, simultaneous co-inhibition of CDK2, a protein which acts with CDK4/6 to promote cell cycle progression, has been shown to have accentuated anti-tumor activity in vivo and in vitro (118–120), pointing to another potential combination strategy. In a similar vein, concurrent inhibition of CDK4/6 and ERK in PDAC organoid models resulted in apoptosis (119). There are clinical trials ongoing of CDK inhibitors in combination with MEK inhibitors [NCT05554367], ERK inhibitors [NCT03454035], direct G12C inhibitors, and SHP2 inhibitors (Table 2).

Additional agents currently at clinical trial stage in combination with KRAS inhibitors in PDAC include poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (olaparib), aurora kinase inhibitors (LY3295668), autophagy inhibitors (DCC-3116) and FAK inhibitor (IN10018) as well as traditional chemotherapy drugs.

Novel strategies to target KRAS

KRAS degraders

An innovative approach to target KRAS-driven cancers is to accelerate the destruction of mutant KRAS alleles. Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras (PROTACs) utilize the cell’s natural system for the destruction of damaged proteins (ubiquitin ligase) (121). These bivalent molecules form a complex with the mutant protein and E3 ubiquitin ligase. The E3 ligase then marks the mutant protein resulting in degradation (122). ASP3082, a PROTAC targeting KRASG12D has shown encouraging preclinical results with inhibition of growth in PDAC cancer cells. A phase I clinical trial is ongoing (123). It is likely that these agents will show a higher level of toxicity but may have a role in treating cancers driven by wild-type KRAS or amplified KRAS. PROTACs targeting SOS1 are also in development (124).

siRNA

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) are short duplex RNA molecules that are introduced into target cells, inhibit the expression of specific messenger RNA, thereby causing gene silencing (125–128). At a cellular level, siRNA is specific, however delivery to target tissue can be challenging due to quick degradation, fast renal clearance and the dense stroma of PDAC (129, 130). One delivery approach is local intratumoral administration of siRNA. In a phase I/IIa study, Golan et al. enrolled 15 patients with locally advanced PDAC. They each had a biodegradable implant (Local Drug EluteR, LODER) containing siRNA targeting G12D inserted into their tumor and were treated synchronously with systemic chemotherapy (131). Response was seen in 2/12 analyzed by CT scans, with 10/12 exhibiting stable disease and median OS of 15.1 months (95% CI, 10.2–18.4). However, serious TRAEs were observed in 5/15 patients (131). Exosomes are an alternate delivery method. They are nano-sized extracellular vesicles that can be internalized by cells and used to deliver cargo (132). These exosomes have advantages over liposomes in terms of their efficiency and half-life due to CD47 on the surface (133). Enhanced macropinocytosis in KRAS mutant cells enables uptake of exosomes despite the dense stroma of pancreatic cancers (134). Kamerkar et al. successfully engineered exosomes to carry siRNA targeting KRASG12D and found that treatment inhibited cancer growth in advanced PDAC mouse models and increased overall survival (135).

Adoptive cell therapy

In 2016, Tran et al. reported the first case of a KRASG12D mutated colorectal cancer treated with T cells recognizing neoantigen G12D-HLA-C*08:02. Regression was seen in all 7 metastases (136). More recently, the same group reported the case of a patient with KRASG12D mutated metastatic pancreatic cancer who was treated with autologous peripheral CD8+ and CD4+ T cells which had been engineered to express a T cell receptor (TCR) against the mutant KRASG12D (137). Treatment response was ongoing at 6 months. This is promising; however, the heterogeneity of KRAS-mutated pancreatic cancer may dampen the dramatic responses seen in other malignancies. The ability to select for neoantigens and the logistics of these strategies will pose global challenges.

Cancer vaccination

Peptide vaccines are increasingly being developed to elicit an immune response in PDAC and may provide greatest benefit in the adjuvant setting. ELI-002 consists of amphiphile-modified KRAS mutant peptides (G12D and G12R) together with amphiphile-modified Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9 agonistic CPG-7909 DNA. The novel approach through its binding to endogenous albumin encourages transit from subcutaneous tissues into lymph glands rather than the bloodstream. In AMPLIFY-201, patients were treated who had ctDNA detected or elevation in serum biomarkers following completion of surgery/adjuvant therapy. Twenty-five patients were included and 84% demonstrated mutated KRAS-specific T cell responses. Reduction in ctDNA was seen in 77% with 33% showing clearance of ctDNA (138). AMPLIFY-7P will further investigate a related compound, ELI-002 7P in a phase I/II study.

TG01 is a vaccine containing seven synthetic RAS peptides that target KRAS. In phase I/II trial, 32 patients with resected stage I or II PDAC were treated with TG01/GM-CSF in combination with adjuvant gemcitabine. Over 90% developed an immune response as defined by a delayed-type hypersensitivity response and/or a positive T cell proliferation assay. Median OS was 33.1 months (95% CI 16.8, 45.8) (139). A phase II trial is underway (NCT 05638698). Another long peptide pooled mutant-KRAS vaccine is being investigated in a phase I trial in combination with nivolumab and ipilimumab in patients with resected MMR-proficient colorectal cancer and pancreatic cancer (NCT04117087).

The KISIMA vaccine platform includes 3 components: a cell-penetrating peptide for intracellular antigen delivery, a multi-antigenic cargo tailored to the tumor type and a TLR peptide agonist to enhance the immune response. A phase I trial is underway in which patients are treated with a ‘prime-boost’ vaccine, consisting of the protein vaccine described (ATP150 or ATP152) in combination with a viral vector VSV-GP154 and an immune checkpoint inhibitor (KISIMA-02). Initial testing will be done in locally advanced/metastatic KRASG12D or KRASG12V mutated PDAC, progressing to randomized parallel cohorts of resected PDAC and a control arm (NCT05846516). DC3/8 is a dendritic cell (DC) vaccine loaded with KRAS mutated peptide which is currently being investigated in resected PDAC patients. An accrual target of 29 patients will receive autologous DCs with mutant KRAS peptides according to the patient’s tumor mutation and HLA subtype (NCT03592888). The mRNA vaccine mRNA-5671/V941 is enclosed in a lipid nanoparticle which targets KRAS G12D, G12V, G13D, and G12C. The mRNA is absorbed by APCs and translated into peptides to be presented. This has elicited strong T-cell responses in mouse models (140, 141). A phase I in-human clinical trial of V941 alone or with pembrolizumab has completed accrual, and results are awaited (NCT03948763).

Resistance mechanisms

Although KRAS mutations are prevalent across tumor types, it’s clear that there is heterogeneity with regard to responses. Understanding both innate and acquired resistance mechanisms to KRAS inhibitors is key to identifying optimal combination strategies and overcoming the modest duration of response we have seen with existing direct KRAS inhibitors. Adaptation to G12C inhibitors has been described as happening in a G12C-dependent or independent manner and can be rapid (142). Dependant adaptation occurs post treatment with G12C inhibitors, when some cancer cells are sequestered in an inactive state and newly formed G12C cancer cells are amplified and resume proliferation (143). Independent adaptation happens through a variety of mechanisms (89, 143). KRAS cells may acquire additional KRAS mutations on codons 12, 13, and 61. They may also acquire mutations on the switch II binding pocket, e.g., KRAS R68S, H95D/Q/R, Y96C/D (89, 143). These mutations may lead to noncovalent binding inhibition at the pocket site. Interestingly, some pocket site mutations which appeared after adagrasib treatment, conferred marked resistance to adagrasib however remained sensitive to sotorasib (143). Therefore, resistance to some inactive-state inhibitors can be overcome by a functionally distinct KRASG12C inhibitor (89). In addition, the tricomplex inhibitors may overcome resistance from mutations in the switch II pocket.

Secondary bypass alterations in the RAS/MAPK/PI3K signaling pathway in patients who have progressed on sotorasib/adagrasib have also been documented (143, 144). These included treatment-emergent amplifications, mutations or fusions of genes encoding receptor tyrosine kinases MET, EGFR, RET, ALK, and FGFR3 leading to investigation of combination strategies. However, the specific receptor tyrosine kinase driving the rebound in signaling can vary widely among tumors suggesting it might be advantageous to look at downstream blockade. Other bypass mechanisms include mutations or fusions of downstream effector kinases: BRAF, CRAF, and MEK1; loss of function mutations in NF1 and PTEN; NRAS and PI3K mutations. Cell state transitions are an additional mechanism of resistance and in NSCLC cell lines epithelial to mesenchymal transition was responsible for both intrinsic and acquired resistance (145). The contribution of the TME and stromal compartment in resistance is yet to be established.

The diversity of resistance mechanisms that have emerged in response to KRAS G12C inhibition highlights the challenges in targeting RAS. As data on pan-RAS inhibitors emerge, these will no doubt expand, underscoring the need for rapid adaptive combination approaches in the trial setting.

Future directions/conclusion

Targeting the RAS pathway remains the biggest challenge in precision oncology. The future in PDAC will likely see selection of first line combinations based on KRAS allelic status.

Vaccine strategies herald huge promise, especially in early-stage disease. The modest duration of response and emergence of resistance mechanisms to the KRASG12C inhibitors points to challenges that we are likely to see across the direct KRAS inhibitors. Overcoming resistance and defining optimal combination strategies is likely to be crucial to improving patient outcomes. This requires an in-depth knowledge of not just the mutational profile but of metabolic needs and distinct TMEs of each patient. The plethora of new agents under investigation has the potential to revolutionize the treatment paradigm for patients with KRAS-mutated pancreatic cancer.

Author contributions

AL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. MO’R: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. RM: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. GO’K: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Prior, IA, Hood, FE, and Hartley, JL. The frequency of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. (2020) 80:2969–74. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-3682

2. Barbacid, M . Ras genes. Annu Rev Biochem. (1987) 56:779–827. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.004023

3. Wang, X, Allen, S, Blake, JF, Bowcut, V, Briere, DM, Calinisan, A, et al. Identification of MRTX1133, a noncovalent, potent, and selective KRAS(G12D) inhibitor. J Med Chem. (2022) 65:3123–33. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01688

4. Skoulidis, F, Li, BT, Dy, GK, Price, TJ, Falchook, GS, Wolf, J, et al. Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p.G12C mutation. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:2371–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103695

5. Prior, IA, Lewis, PD, and Mattos, C. A comprehensive survey of Ras mutations in cancer. Cancer Res. (2012) 72:2457–67. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2612

6. Aran, V . K-RAS4A: Lead or supporting role in Cancer biology? Front Mol Biosci. (2021) 8:729830. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.729830

7. Boriack-Sjodin, PA, Margarit, SM, Bar-Sagi, D, and Kuriyan, J. The structural basis of the activation of Ras by Sos. Nature. (1998) 394:337–43. doi: 10.1038/28548

8. Dance, M, Montagner, A, Salles, JP, Yart, A, and Raynal, P. The molecular functions of Shp2 in the Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (ERK1/2) pathway. Cell Signal. (2008) 20:453–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.10.002

9. Trahey, M, and McCormick, F. A cytoplasmic protein stimulates normal N-ras p21 GTPase, but does not affect oncogenic mutants. Science. (1987) 238:542–5. doi: 10.1126/science.2821624

10. Simanshu, DK, Nissley, DV, and McCormick, F. RAS proteins and their regulators in human disease. Cell. (2017) 170:17–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.009

11. Terrell, EM, and Morrison, DK. Ras-mediated activation of the Raf family kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. (2019) 9:a033746. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a033746

12. Weber, JD, Raben, DM, Phillips, PJ, and Baldassare, JJ. Sustained activation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 1 (ERK1) is required for the continued expression of cyclin D1 in G1 phase. Biochem J. (1997) 326:61–8. doi: 10.1042/bj3260061

13. Bournet, B, Muscari, F, Buscail, C, Assenat, E, Barthet, M, Hammel, P, et al. KRAS G12D mutation subtype is a prognostic factor for advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. (2016) 7:e157. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2016.18

14. Hoxhaj, G, and Manning, BD. The PI3K–AKT network at the interface of oncogenic signalling and cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. (2020) 20:74–88. doi: 10.1038/s41568-019-0216-7

15. Huang, L, Guo, Z, Wang, F, and Fu, L. KRAS mutation: from undruggable to druggable in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2021) 6:386. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00780-4

16. Liu, GY, and Sabatini, DM. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2020) 21:183–203. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0199-y

17. Hofer, F, Fields, S, Schneider, C, and Martin, GS. Activated Ras interacts with the Ral guanine nucleotide dissociation stimulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1994) 91:11089–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11089

18. Biankin, AV, Waddell, N, Kassahn, KS, Gingras, MC, Muthuswamy, LB, Johns, AL, et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature. (2012) 491:399–405. doi: 10.1038/nature11547

19. Lee, JK, Sivakumar, S, Schrock, AB, Madison, R, Fabrizio, D, Gjoerup, O, et al. Comprehensive pan-cancer genomic landscape of KRAS altered cancers and real-world outcomes in solid tumors. NPJ Precis Oncol. (2022) 6:91. doi: 10.1038/s41698-022-00334-z

20. Witkiewicz, AK, McMillan, EA, Balaji, U, Baek, G, Lin, WC, Mansour, J, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of pancreatic cancer defines genetic diversity and therapeutic targets. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:6744. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7744

21. Bailey, P, Chang, DK, Nones, K, Johns, AL, Patch, AM, Gingras, MC, et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. (2016) 531:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965

22. Qian, ZR, Rubinson, DA, Nowak, JA, Morales-Oyarvide, V, Dunne, RF, Kozak, MM, et al. Association of Alterations in Main driver genes with outcomes of patients with resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. JAMA Oncol. (2018) 4:e173420. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3420

23. Hunter, JC, Manandhar, A, Carrasco, MA, Gurbani, D, Gondi, S, and Westover, KD. Biochemical and structural analysis of common Cancer-associated KRAS mutations. Mol Cancer Res. (2015) 13:1325–35. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-15-0203

24. Mann, KM, Ying, H, Juan, J, Jenkins, NA, and Copeland, NG. KRAS-related proteins in pancreatic cancer. Pharmacol Ther. (2016) 168:29–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.09.003

25. Rabara, D, Tran, TH, Dharmaiah, S, Stephens, RM, McCormick, F, Simanshu, DK, et al. KRAS G13D sensitivity to neurofibromin-mediated GTP hydrolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2019) 116:22122–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1908353116

26. Dogan, S, Shen, R, Ang, DC, Johnson, ML, D'Angelo, SP, Paik, PK, et al. Molecular epidemiology of EGFR and KRAS mutations in 3,026 lung adenocarcinomas: higher susceptibility of women to smoking-related KRAS-mutant cancers. Clin Cancer Res. (2012) 18:6169–77. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3265

27. Hofmann, MH, Gerlach, D, Misale, S, Petronczki, M, and Kraut, N. Expanding the reach of precision oncology by drugging all KRAS mutants. Cancer Discov. (2022) 12:924–37. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-1331

28. Wong, GS, Zhou, J, Liu, JB, Wu, Z, Xu, X, Li, T, et al. Targeting wild-type KRAS-amplified gastroesophageal cancer through combined MEK and SHP2 inhibition. Nat Med. (2018) 24:968–77. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0022-x

29. Mueller, S, Engleitner, T, Maresch, R, Zukowska, M, Lange, S, Kaltenbacher, T, et al. Evolutionary routes and KRAS dosage define pancreatic cancer phenotypes. Nature. (2018) 554:62–8. doi: 10.1038/nature25459

30. Chan-Seng-Yue, M, Kim, JC, Wilson, GW, Ng, K, Figueroa, EF, O'Kane, GM, et al. Transcription phenotypes of pancreatic cancer are driven by genomic events during tumor evolution. Nat Genet. (2020) 52:231–40. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0566-9

31. Cucurull, M, Notario, L, Sanchez-Cespedes, M, Hierro, C, Estival, A, Carcereny, E, et al. Targeting KRAS in lung Cancer beyond KRAS G12C inhibitors: the immune regulatory role of KRAS and novel therapeutic strategies. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:793121. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.793121

32. Connor, AA, and Gallinger, S. Pancreatic cancer evolution and heterogeneity: integrating omics and clinical data. Nat Rev Cancer. (2022) 22:131–42. doi: 10.1038/s41568-021-00418-1

33. Aguirre, AJ, Nowak, JA, Camarda, ND, Moffitt, RA, Ghazani, AA, Hazar-Rethinam, M, et al. Real-time genomic characterization of advanced pancreatic Cancer to enable precision medicine. Cancer Discov. (2018) 8:1096–111. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0275

34. Fuentes Antrás, JJG, Topham, JT, Zhang, A, Tsang, ES, Wang, Y, Hutchinson, S, et al. Molecular characterization of long-term and short-term survivors of advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. (2022) 40:4024–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.4024

35. Hruban, RH, Goggins, M, Parsons, J, and Kern, SE. Progression model for pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2000) 6:2969–72.

36. Maitra, A, Adsay, NV, Argani, P, Iacobuzio-Donahue, C, De Marzo, A, Cameron, JL, et al. Multicomponent analysis of the pancreatic adenocarcinoma progression model using a pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia tissue microarray. Mod Pathol. (2003) 16:902–12. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000086072.56290.FB

37. Notta, F, Chan-Seng-Yue, M, Lemire, M, Li, Y, Wilson, GW, Connor, AA, et al. A renewed model of pancreatic cancer evolution based on genomic rearrangement patterns. Nature. (2016) 538:378–82. doi: 10.1038/nature19823

38. Ideno, N, Yamaguchi, H, Ghosh, B, Gupta, S, Okumura, T, Steffen, DJ, et al. GNAS(R201C) induces pancreatic cystic neoplasms in mice that express activated KRAS by inhibiting YAP1 signaling. Gastroenterology. (2018) 155:1593–1607.e12. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.006

39. Hosein, AN, Dangol, G, Okumura, T, Roszik, J, Rajapakshe, K, Siemann, M, et al. Loss of Rnf43 accelerates Kras-mediated neoplasia and remodels the tumor immune microenvironment in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. (2022) 162:1303–1318.e18. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.12.273

40. Noe, M, Niknafs, N, Fischer, CG, Hackeng, WM, Beleva Guthrie, V, Hosoda, W, et al. Genomic characterization of malignant progression in neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:4085. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17917-8

41. Connor, AA, Denroche, RE, Jang, GH, Lemire, M, Zhang, A, Chan-Seng-Yue, M, et al. Integration of genomic and transcriptional features in pancreatic Cancer reveals increased cell cycle progression in metastases. Cancer Cell. (2019) 35:267–282.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.12.010

42. Hingorani, SR, Petricoin, EF, Maitra, A, Rajapakse, V, King, C, Jacobetz, MA, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. (2003) 4:437–50. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00309-X

43. Clark, CE, Beatty, GL, and Vonderheide, RH. Immunosurveillance of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: insights from genetically engineered mouse models of cancer. Cancer Lett. (2009) 279:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.09.037

44. Lesina, M, Kurkowski, MU, Ludes, K, Rose-John, S, Treiber, M, Klöppel, G, et al. Stat3/Socs3 activation by IL-6 transsignaling promotes progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and development of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. (2011) 19:456–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.009

45. Ancrile, B, Lim, KH, and Counter, CM. Oncogenic Ras-induced secretion of IL6 is required for tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. (2007) 21:1714–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.1549407

46. Corcoran, RB, Contino, G, Deshpande, V, Tzatsos, A, Conrad, C, Benes, CH, et al. STAT3 plays a critical role in KRAS-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. (2011) 71:5020–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0908

47. Pylayeva-Gupta, Y, Lee, KE, Hajdu, CH, Miller, G, and Bar-Sagi, D. Oncogenic Kras-induced GM-CSF production promotes the development of pancreatic neoplasia. Cancer Cell. (2012) 21:836–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.024

48. Bayne, LJ, Beatty, GL, Jhala, N, Clark, CE, Rhim, AD, Stanger, BZ, et al. Tumor-derived granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor regulates myeloid inflammation and T cell immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. (2012) 21:822–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.025

49. Waghray, M, Yalamanchili, M, Dziubinski, M, Zeinali, M, Erkkinen, M, Yang, H, et al. GM-CSF mediates mesenchymal-epithelial cross-talk in pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. (2016) 6:886–99. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0947

50. Hamarsheh, S, Osswald, L, Saller, BS, Unger, S, De Feo, D, Vinnakota, JM, et al. Oncogenic Kras(G12D) causes myeloproliferation via NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:1659. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15497-1

51. Sparmann, A, and Bar-Sagi, D. Ras-induced interleukin-8 expression plays a critical role in tumor growth and angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. (2004) 6:447–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.028

52. Ijichi, H, Chytil, A, Gorska, AE, Aakre, ME, Bierie, B, Tada, M, et al. Inhibiting Cxcr2 disrupts tumor-stromal interactions and improves survival in a mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Invest. (2011) 121:4106–17. doi: 10.1172/JCI42754

53. Steele, CW, Karim, SA, Leach, JDG, Bailey, P, Upstill-Goddard, R, Rishi, L, et al. CXCR2 inhibition profoundly suppresses metastases and augments immunotherapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. (2016) 29:832–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.04.014

54. Ling, J, Kang, Y, Zhao, R, Xia, Q, Lee, DF, Chang, Z, et al. KrasG12D-induced IKK2/β/NF-κB activation by IL-1α and p62 feedforward loops is required for development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. (2012) 21:105–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.006

55. Zdanov, S, Mandapathil, M, Abu Eid, R, Adamson-Fadeyi, S, Wilson, W, Qian, J, et al. Mutant KRAS conversion of conventional T cells into regulatory T cells. Cancer Immunol Res. (2016) 4:354–65. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0241

56. Romero, JM, Grunwald, B, Jang, GH, Bavi, PP, Jhaveri, A, Masoomian, M, et al. A four-chemokine signature is associated with a T-cell-inflamed phenotype in primary and metastatic pancreatic Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2020) 26:1997–2010. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2803

57. Terrero, G, Datta, J, Dennison, J, Sussman, DA, Lohse, I, Merchant, NB, et al. Ipilimumab/Nivolumab therapy in patients with metastatic pancreatic or biliary Cancer with homologous recombination deficiency pathogenic germline variants. JAMA Oncol. (2022) 8:1–3. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.0611

58. Geng, X, Chen, H, Zhao, L, Hu, J, Yang, W, Li, G, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast (CAF) heterogeneity and targeting therapy of CAFs in pancreatic Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2021) 9:655152. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.655152

59. Helms, EJ, Berry, MW, Chaw, RC, DuFort, CC, Sun, D, Onate, MK, et al. Mesenchymal lineage heterogeneity underlies nonredundant functions of pancreatic Cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Discov. (2022) 12:484–501. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0601

60. Cheng, NC, and Vonderheide, RH. Immune vulnerabilities of mutant KRAS in pancreatic cancer. Trends Cancer. (2023) 9:928–36. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2023.07.004

61. Velez-Delgado, A, Donahue, KL, Brown, KL, Du, W, Irizarry-Negron, V, Menjivar, RE, et al. Extrinsic KRAS signaling shapes the pancreatic microenvironment through fibroblast reprogramming. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2022) 13:1673–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2022.02.016

62. O'Reilly, EM, Oh, DY, Dhani, N, Renouf, DJ, Lee, MA, Sun, W, et al. Durvalumab with or without Tremelimumab for patients with metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. (2019) 5:1431–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.1588

63. Racker, E, Resnick, RJ, and Feldman, R. Glycolysis and methylaminoisobutyrate uptake in rat-1 cells transfected with ras or myc oncogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1985) 82:3535–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.11.3535

64. Hobbs, GA, Baker, NM, Miermont, AM, Thurman, RD, Pierobon, M, Tran, TH, et al. Atypical KRAS(G12R) mutant is impaired in PI3K signaling and macropinocytosis in pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. (2020) 10:104–23. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1006

65. Salem, ME, El-Refai, SM, Sha, W, Puccini, A, Grothey, A, George, TJ, et al. Landscape of KRAS(G12C), associated genomic alterations, and interrelation with Immuno-oncology biomarkers in KRAS-mutated cancers. JCO Precis Oncol. (2022) 6:e2100245. doi: 10.1200/PO.21.00245

66. Ying, H, Kimmelman, AC, Lyssiotis, CA, Hua, S, Chu, GC, Fletcher-Sananikone, E, et al. Oncogenic Kras maintains pancreatic tumors through regulation of anabolic glucose metabolism. Cell. (2012) 149:656–70. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.058

67. DeBerardinis, RJ, and Cheng, T. Q's next: the diverse functions of glutamine in metabolism, cell biology and cancer. Oncogene. (2010) 29:313–24. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.358

68. Yang, L, Venneti, S, and Nagrath, D. Glutaminolysis: a Hallmark of Cancer metabolism. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. (2017) 19:163–94. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071516-044546

69. Guo, JY, Chen, HY, Mathew, R, Fan, J, Strohecker, AM, Karsli-Uzunbas, G, et al. Activated Ras requires autophagy to maintain oxidative metabolism and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. (2011) 25:460–70. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016311

70. Yang, S, Wang, X, Contino, G, Liesa, M, Sahin, E, Ying, H, et al. Pancreatic cancers require autophagy for tumor growth. Genes Dev. (2011) 25:717–29. doi: 10.1101/gad.2016111

71. Bryant, KL, Stalnecker, CA, Zeitouni, D, Klomp, JE, Peng, S, Tikunov, AP, et al. Combination of ERK and autophagy inhibition as a treatment approach for pancreatic cancer. Nat Med. (2019) 25:628–40. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0368-8

72. White, E . Exploiting the bad eating habits of Ras-driven cancers. Genes Dev. (2013) 27:2065–71. doi: 10.1101/gad.228122.113

73. Kamphorst, JJ, Nofal, M, Commisso, C, Hackett, SR, Lu, W, Grabocka, E, et al. Human pancreatic cancer tumors are nutrient poor and tumor cells actively scavenge extracellular protein. Cancer Res. (2015) 75:544–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2211

74. Philip, PA, Buyse, ME, Alistar, AT, Lima, CMSPR, Luther, S, Pardee, TS, et al. Avenger 500, a phase III open-label randomized trial of the combination of CPI-613 with modified FOLFIRINOX (mFFX) versus FOLFIRINOX (FFX) in patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. J Clin Oncol. (2019) 37:TPS479. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.4_suppl.TPS479

75. Ostrem, JM, Peters, U, Sos, ML, Wells, JA, and Shokat, KM. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature. (2013) 503:548–51. doi: 10.1038/nature12796

76. Lito, P, Solomon, M, Li, LS, Hansen, R, and Rosen, N. Allele-specific inhibitors inactivate mutant KRAS G12C by a trapping mechanism. Science. (2016) 351:604–8. doi: 10.1126/science.aad6204

77. Fakih, MG, Kopetz, S, Kuboki, Y, Kim, TW, Munster, PN, Krauss, JC, et al. Sotorasib for previously treated colorectal cancers with KRAS(G12C) mutation (CodeBreaK100): a prespecified analysis of a single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2022) 23:115–24. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00605-7

78. Kuboki, Y, Yaeger, R, Fakih, MG, Strickler, JH, Masuishi, T, Kim, EJ, et al. 315O Sotorasib in combination with panitumumab in refractory KRAS G12C-mutated colorectal cancer: safety and efficacy for phase Ib full expansion cohort. Ann Oncol. (2022) 33:S680–1. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.07.453

79. Kuboki, Y, Strickler, JH, Fakih, M, Houssiau, H, Price, TJ, Elez, E, et al. Sotorasib (Soto) plus panitumumab (Pmab) and FOLFIRI for previously treated KRAS G12C-mutated metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC): CodeBreaK 101 phase 1b safety and efficacy. J Clin Oncol. (2023) 41:3513. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.3513

80. Strickler, JH, Satake, H, George, TJ, Yaeger, R, Hollebecque, A, Garrido-Laguna, I, et al. Sotorasib in KRAS p.G12C-mutated advanced pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med. (2023) 388:33–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2208470

81. de Langen, AJ, Johnson, ML, Mazieres, J, Dingemans, AC, Mountzios, G, Pless, M, et al. Sotorasib versus docetaxel for previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer with KRAS(G12C) mutation: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. (2023) 401:733–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00221-0

82. Jänne, PA, Riely, GJ, Gadgeel, SM, Heist, RS, Ou, SI, Pacheco, JM, et al. Adagrasib in non-small-cell lung Cancer harboring a KRAS(G12C) mutation. N Engl J Med. (2022) 387:120–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204619

83. Sacher, A, LoRusso, P, Patel, MR, Miller, WH, Garralda, E, Forster, MD, et al. Single-agent Divarasib (GDC-6036) in solid tumors with a KRAS G12C mutation. N Engl J Med. (2023) 389:710–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2303810

84. Yaeger, R, Weiss, J, Pelster, MS, Spira, AI, Barve, M, Ou, SI, et al. Adagrasib with or without Cetuximab in colorectal Cancer with mutated KRAS G12C. N Engl J Med. (2023) 388:44–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2212419

85. Bekaii-Saab, TS, Yaeger, R, Spira, AI, Pelster, MS, Sabari, JK, Hafez, N, et al. Adagrasib in advanced solid tumors harboring a KRAS(G12C) mutation. J Clin Oncol. (2023) 41:4097–106. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.00434

86. Ou, S-HI, Jänne, PA, Leal, TA, Rybkin, II, Sabari, JK, Barve, MA, et al. First-in-human phase I/IB dose-finding study of Adagrasib (MRTX849) in patients with advanced KRASG12C solid tumors (KRYSTAL-1). J Clin Oncol. (2022) 40:2530–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02752

87. Murciano-Goroff, YR, Heist, RS, Kuboki, Y, Koyama, T, Ammakkanavar, NR, Hollebecque, A, et al. Abstract CT028: a first-in-human phase 1 study of LY3537982, a highly selective and potent KRAS G12C inhibitor in patients with KRAS G12C-mutant advanced solid tumors. Cancer Res. (2023) 83:CT028–CT. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2023-CT028

88. Jänne, PABF, Papadopoulos, K, Eberst, L, Sommerhalder, D, Lebellec, L, Voon, PJ, et al. Abstract PR014: preliminary safety and anti-tumor activity of RMC-6291, a first-in-class, tri-complex KRASG12C (ON) inhibitor, in patients with or without prior KRASG12C (OFF) inhibitor treatment. Mol Cancer Ther. (2023) 1, 22:PR014. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.TARG-23-PR014

89. Tanaka, N, Lin, JJ, Li, C, Ryan, MB, Zhang, J, Kiedrowski, LA, et al. Clinical acquired resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition through a novel KRAS switch-II pocket mutation and polyclonal alterations converging on RAS-MAPK reactivation. Cancer Discov. (2021) 11:1913–22. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-21-0365

90. Hallin, J, Bowcut, V, Calinisan, A, Briere, DM, Hargis, L, Engstrom, LD, et al. Anti-tumor efficacy of a potent and selective non-covalent KRASG12D inhibitor. Nat Med. (2022) 28:2171–82. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-02007-7

91. Zhou, CLW, Song, Z, Zhang, Y, Huang, D, Yang, Z, Zhou, M, et al. LBA33 a first-in-human phase I study of a novel KRAS G12D inhibitor HRS-4642 in patients with advanced solid tumors harboring KRAS G12D mutation. Ann Oncol. (2023) 34:S1273. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.10.025

92. Jiang, L, Menard, M, Weller, C, Wang, Z, Burnett, L, Aronchik, I, et al. Abstract 526: RMC-9805, a first-in-class, mutant-selective, covalent and oral KRASG12D(ON) inhibitor that induces apoptosis and drives tumor regression in preclinical models of KRASG12D cancers. Cancer Res. (2023) 83:526. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2023-526

93. Mao, Z, Xiao, H, Shen, P, Yang, Y, Xue, J, Yang, Y, et al. KRAS(G12D) can be targeted by potent inhibitors via formation of salt bridge. Cell Discov. (2022) 8:5. doi: 10.1038/s41421-021-00368-w

94. Arbour, KCPS, Garrido-Laguna, I, Hong, DS, Wolpin, B, Pelster, MS, Barve, M, et al. 652O preliminary clinical activity of RMC-6236, a first-in-class, RAS-selective, tri-complex RAS-MULTI (ON) inhibitor in patients with KRAS mutant pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Ann Oncol. (2023) 34:S458. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.09.1838

95. Koltun, ES, Rice, MA, Gustafson, WC, Wilds, D, Jiang, J, Lee, BJ, et al. Abstract 3597: direct targeting of KRASG12X mutant cancers with RMC-6236, a first-in-class, RAS-selective, orally bioavailable, tri-complex RASMULTI(ON) inhibitor. Cancer Res. (2022) 82:3597. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2022-3597

96. Popescu, B, Stieglitz, E, and Smith, CC. RAS MULTI(ON) inhibitor RMC-7977 targets oncogenic RAS mutations and overcomes RAS/MAPK-mediated resistance to FLT3 inhibitors in AML models. Blood. (2023) 142:2793. doi: 10.1182/blood-2023-178397

97. Kessler, D, Bergner, A, Böttcher, J, Fischer, G, Döbel, S, Hinkel, M, et al. Drugging all RAS isoforms with one pocket. Future Med Chem. (2020) 12:1911–23. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2020-0221

98. Kim, D, Herdeis, L, Rudolph, D, Zhao, Y, Böttcher, J, Vides, A, et al. Pan-KRAS inhibitor disables oncogenic signalling and tumour growth. Nature. (2023) 619:160–6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06123-3

99. Tolani, B, Celli, A, Yao, Y, Tan, YZ, Fetter, R, Liem, CR, et al. Ras-mutant cancers are sensitive to small molecule inhibition of V-type ATPases in mice. Nat Biotechnol. (2022) 40:1834–44. doi: 10.1038/s41587-022-01386-z

100. Hofmann, MH, Lu, H, Duenzinger, U, Gerlach, D, Trapani, F, Machado, AA, et al. Abstract CT210: trial in process: phase 1 studies of BI 1701963, a SOS1::KRAS inhibitor, in combination with MEK inhibitors, irreversible KRASG12C inhibitors or irinotecan. Cancer Res. (2021) 81:CT210. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2021-CT210

101. Johnson, ML, Gort, E, Pant, S, Lolkema, MP, Sebastian, M, Scheffler, M, et al. 524P a phase I, open-label, dose-escalation trial of BI 1701963 in patients (pts) with KRAS mutated solid tumours: a snapshot analysis. Ann Oncol. (2021) 32:S591–2. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.1046

102. Brazel, D, Arter, Z, and Nagasaka, M. A long overdue targeted treatment for KRAS mutations in NSCLC: spotlight on Adagrasib. Lung Cancer (Auckl). (2022) 13:75–80. doi: 10.2147/LCTT.S383662

103. Ou, SI, Koczywas, M, Ulahannan, S, Janne, P, Pacheco, J, Burris, H, et al. A12 the SHP2 inhibitor RMC-4630 in patients with KRAS-mutant non-small cell lung Cancer: preliminary evaluation of a first-in-man phase 1 clinical trial. J Thorac Oncol. (2020) 15:S15–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.12.041

104. Hayes, JL, Koczywas, M, Ou, S-HI, Janne, PA, Pacheco, JM, Ulahannan, S, et al. Abstract LB054: confirmation of target inhibition and anti-tumor activity of the SHP2 inhibitor RMC-4630 via longitudinal analysis of ctDNA in a phase 1 clinical study. Cancer Res. (2021) 81:LB054. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2021-LB054

105. Brana, I, Shapiro, G, Johnson, ML, Yu, HA, Robbrecht, D, Tan, DS-W, et al. Initial results from a dose finding study of TNO155, a SHP2 inhibitor, in adults with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. (2021) 39:3005. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.3005

106. McKean, M, Rosen, E, Barve, M, Meniawy, T, Wang, J, Hong, DS, et al. Abstract CT184: preliminary dose escalation results of ERAS-601 in combination with cetuximab in FLAGSHP-1: a phase I study of ERAS-601, a potent and selective SHP2 inhibitor, in patients with previously treated advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Cancer Res. (2023) 83:CT184. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2023-CT184

107. Gebregiworgis, T, Kano, Y, St-Germain, J, Radulovich, N, Udaskin, ML, Mentes, A, et al. The Q61H mutation decouples KRAS from upstream regulation and renders cancer cells resistant to SHP2 inhibitors. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:6274. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26526-y

108. Ryan, MB, Fece de la Cruz, F, Phat, S, Myers, DT, Wong, E, Shahzade, HA, et al. Vertical pathway inhibition overcomes adaptive feedback resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. (2020) 26:1633–43. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3523

109. Wang, J, Zhao, J, Zhong, J, Li, X, Fang, J, Yu, Y, et al. 653O Glecirasib (KRAS G12C inhibitor) in combination with JAB-3312 (SHP2 inhibitor) in patients with KRAS p.G12C mutated solid tumors. Ann Oncol. (2023) 34:S459. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.09.1839

110. Brown, WS, McDonald, PC, Nemirovsky, O, Awrey, S, Chafe, SC, Schaeffer, DF, et al. Overcoming adaptive resistance to KRAS and MEK inhibitors by co-targeting mTORC1/2 complexes in pancreatic Cancer. Cell Rep Med. (2020) 1:100131. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100131

111. Borghaei, H, Paz-Ares, L, Horn, L, Spigel, DR, Steins, M, Ready, NE, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. (2015) 373:1627–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1507643

112. Herbst, RS, Lopes, G, Kowalski, DM, Kasahara, K, Wu, YL, and De Castro, G, Jr.,, et al. LBA4 association of KRAS mutational status with response to pembrolizumab monotherapy given as first-line therapy for PD-L1-positive advanced non-squamous NSCLC in Keynote-042. Ann Oncol (2019);30:xi63–xi64, doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz453.001

113. Frost, N, Kollmeier, J, Vollbrecht, C, Grah, C, Matthes, B, Pultermann, D, et al. KRAS(G12C)/TP53 co-mutations identify long-term responders to first line palliative treatment with pembrolizumab monotherapy in PD-L1 high (≥50%) lung adenocarcinoma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. (2021) 10:737–52. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-20-958

114. Kemp, SB, Cheng, N, Markosyan, N, Sor, R, Kim, IK, Hallin, J, et al. Efficacy of a small-molecule inhibitor of KrasG12D in immunocompetent models of pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov. (2023) 13:298–311. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-22-1066

115. Li, BT, Falchook, GS, Durm, GA, Burns, TF, Skoulidis, F, Ramalingam, SS, et al. OA03.06 CodeBreaK 100/101: first report of safety/efficacy of Sotorasib in combination with Pembrolizumab or Atezolizumab in advanced KRAS p.G12C NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. (2022) 17:S10–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2022.07.025

116. Jänne, PA, Smit, EF, de Marinis, F, Laskin, J, Gomez, MD, Gadgeel, S, et al. LBA4 preliminary safety and efficacy of adagrasib with pembrolizumab in treatment-naïve patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring a KRASG12C mutation. Immuno-Oncol Technol. (2022) 16:100360. doi: 10.1016/j.iotech.2022.100360

117. Ruscetti, M, Morris, JP IV, Mezzadra, R, Russell, J, Leibold, J, Romesser, PB, et al. Senescence-induced vascular remodeling creates therapeutic vulnerabilities in pancreas Cancer. Cell. (2020) 181:424–41.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.008

118. Knudsen, ES, Kumarasamy, V, Chung, S, Ruiz, A, Vail, P, Tzetzo, S, et al. Targeting dual signalling pathways in concert with immune checkpoints for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Gut. (2021) 70:127–38. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321000

119. Goodwin, CM, Waters, AM, Klomp, JE, Javaid, S, Bryant, KL, Stalnecker, CA, et al. Combination therapies with CDK4/6 inhibitors to treat KRAS-mutant pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Res. (2023) 83:141–57. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-22-0391

120. Freeman-Cook, K, Hoffman, RL, Miller, N, Almaden, J, Chionis, J, Zhang, Q, et al. Expanding control of the tumor cell cycle with a CDK2/4/6 inhibitor. Cancer Cell. (2021) 39:1404–21.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.08.009

121. Scudellari, M . Protein-slaying drugs could be the next blockbuster therapies. Nature. (2019) 567:298–300. doi: 10.1038/d41586-019-00879-3

122. Bond, MJ, Chu, L, Nalawansha, DA, Li, K, and Crews, CM. Targeted degradation of oncogenic KRAS(G12C) by VHL-recruiting PROTACs. ACS Cent Sci. (2020) 6:1367–75. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00411

123. Nagashima, T, Inamura, K, Nishizono, Y, Suzuki, A, Tanaka, H, Yoshinari, T, et al. ASP3082, a first-in-class novel KRAS G12D degrader, exhibits remarkable anti-tumor activity in KRAS G12D mutated cancer models. Eur J Cancer. (2022) 174:S30. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(22)00881-4

124. Bian, Y, Alem, D, Beato, F, Hogenson, TL, Yang, X, Jiang, K, et al. Development of SOS1 inhibitor-based degraders to target KRAS-mutant colorectal Cancer. J Med Chem. (2022) 65:16432–50. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c01300

125. Elbashir, SM, Harborth, J, Lendeckel, W, Yalcin, A, Weber, K, and Tuschl, T. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. (2001) 411:494–8. doi: 10.1038/35078107

126. Lam, JK, Chow, MY, Zhang, Y, and Leung, SW. siRNA versus miRNA as therapeutics for gene silencing. Mol Ther Nucl Acids. (2015) 4:e252. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2015.23

127. Yuan, TL, Fellmann, C, Lee, CS, Ritchie, CD, Thapar, V, Lee, LC, et al. Development of siRNA payloads to target KRAS-mutant cancer. Cancer Discov. (2014) 4:1182–97. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0900

128. Davis, ME . The first targeted delivery of siRNA in humans via a self-assembling, cyclodextrin polymer-based nanoparticle: from concept to clinic. Mol Pharm. (2009) 6:659–68. doi: 10.1021/mp900015y

129. Kota, J, Hancock, J, Kwon, J, and Korc, M. Pancreatic cancer: stroma and its current and emerging targeted therapies. Cancer Lett. (2017) 391:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.12.035

130. Kiaie, SH, Mojarad-Jabali, S, Khaleseh, F, Allahyari, S, Taheri, E, Zakeri-Milani, P, et al. Axial pharmaceutical properties of liposome in cancer therapy: recent advances and perspectives. Int J Pharm. (2020) 581:119269. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119269

131. Golan, T, Khvalevsky, EZ, Hubert, A, Gabai, RM, Hen, N, Segal, A, et al. RNAi therapy targeting KRAS in combination with chemotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer patients. Oncotarget. (2015) 6:24560–70. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4183

132. Shtam, TA, Kovalev, RA, Varfolomeeva, EY, Makarov, EM, Kil, YV, and Filatov, MV. Exosomes are natural carriers of exogenous siRNA to human cells in vitro. Cell Commun Signal. (2013) 11:88. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-88

133. Herrmann, IK, Wood, MJA, and Fuhrmann, G. Extracellular vesicles as a next-generation drug delivery platform. Nat Nanotechnol. (2021) 16:748–59. doi: 10.1038/s41565-021-00931-2

134. Bar-Sagi, D, and Feramisco, JR. Induction of membrane ruffling and fluid-phase pinocytosis in quiescent fibroblasts by ras proteins. Science. (1986) 233:1061–8. doi: 10.1126/science.3090687

135. Kamerkar, S, LeBleu, VS, Sugimoto, H, Yang, S, Ruivo, CF, Melo, SA, et al. Exosomes facilitate therapeutic targeting of oncogenic KRAS in pancreatic cancer. Nature. (2017) 546:498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature22341

136. Tran, E, Robbins, PF, Lu, YC, Prickett, TD, Gartner, JJ, Jia, L, et al. T-cell transfer therapy targeting mutant KRAS in Cancer. N Engl J Med. (2016) 375:2255–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609279

137. Leidner, R, Sanjuan Silva, N, Huang, H, Sprott, D, Zheng, C, Shih, YP, et al. Neoantigen T-cell receptor gene therapy in pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med. (2022) 386:2112–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2119662

138. Wainberg, ZA, Weekes, CD, Furqan, M, Kasi, PM, Devoe, CE, Leal, AD, et al. AMPLIFY-201, a first-in-human safety and efficacy trial of adjuvant ELI-002 2P immunotherapy for patients with high-relapse risk with KRAS G12D- or G12R-mutated pancreatic and colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2023) 41:2528. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2023.41.16_suppl.2528

139. Palmer, DH, Valle, JW, Ma, YT, Faluyi, O, Neoptolemos, JP, Jensen Gjertsen, T, et al. TG01/GM-CSF and adjuvant gemcitabine in patients with resected RAS-mutant adenocarcinoma of the pancreas (CT TG01-01): a single-arm, phase 1/2 trial. Br J Cancer. (2020) 122:971–7. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-0752-7

140. Nagasaka, M . ES28.04 emerging mechanisms to target KRAS directly. J Thorac Oncol. (2021) 16:S96–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.01.063

141. Moderna . (2022). KRAS Vaccine (mRNA-5671). Available at: https://s29.q4cdn.com/435878511/files/doc_downloads/program_detail/2022/11/KRAS-(11-03-22).pdf.

142. Xue, JY, Zhao, Y, Aronowitz, J, Mai, TT, Vides, A, Qeriqi, B, et al. Rapid non-uniform adaptation to conformation-specific KRAS(G12C) inhibition. Nature. (2020) 577:421–5. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1884-x

143. Awad, MM, Liu, S, Rybkin, II, Arbour, KC, Dilly, J, Zhu, VW, et al. Acquired resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition in Cancer. N Engl J Med. (2021) 384:2382–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105281

144. Zhao, Y, Murciano-Goroff, YR, Xue, JY, Ang, A, Lucas, J, Mai, TT, et al. Diverse alterations associated with resistance to KRAS(G12C) inhibition. Nature. (2021) 599:679–83. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04065-2

145. Adachi, Y, Ito, K, Hayashi, Y, Kimura, R, Tan, TZ, Yamaguchi, R, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is a cause of both intrinsic and acquired resistance to KRAS G12C inhibitor in KRAS G12C-mutant non-small cell lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2020) 26:5962–73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2077

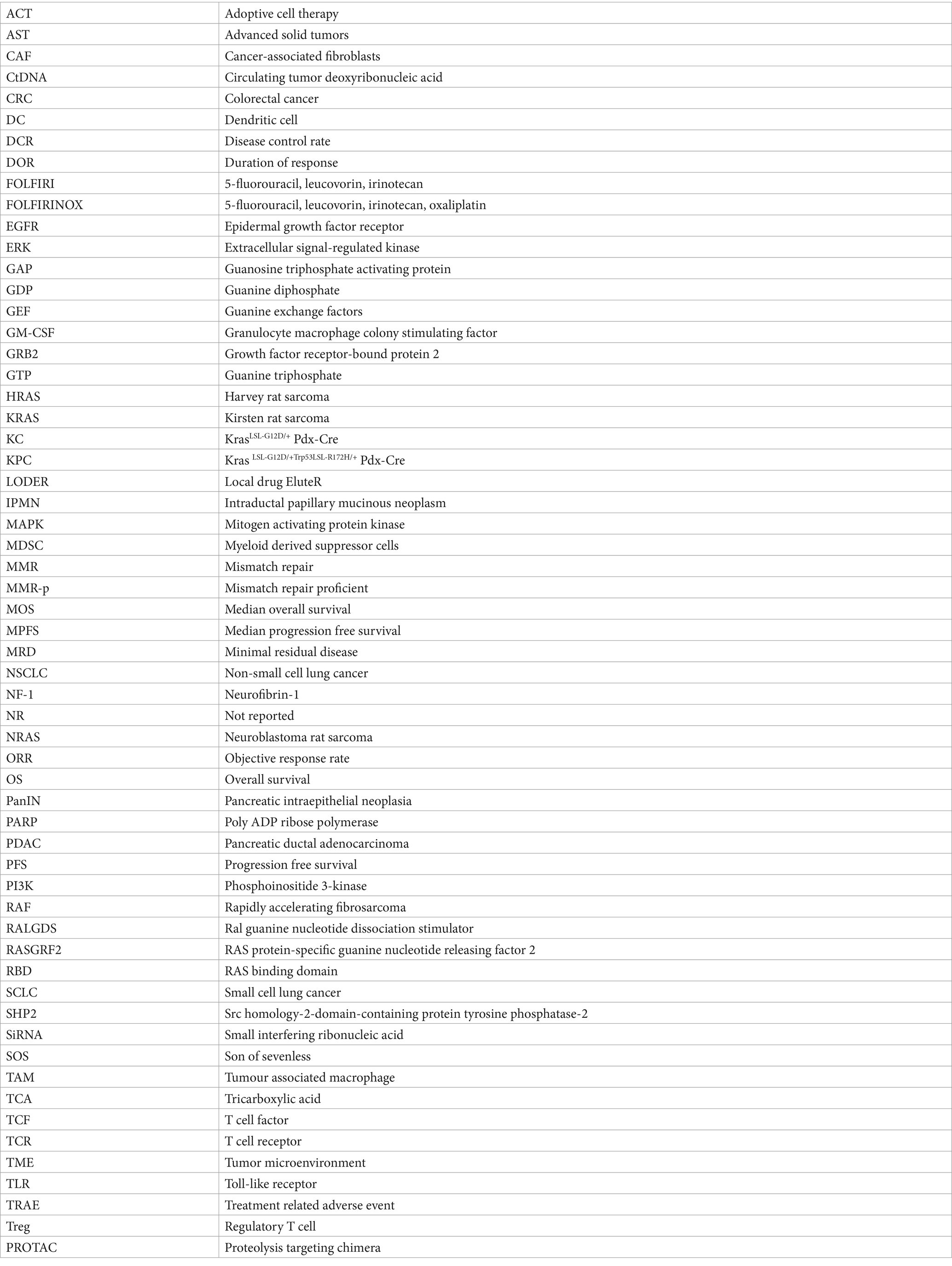

Glossary

Keywords: KRAS, mutation, pancreatic cancer, tumor microenvironment, SHP2, metabolic impact

Citation: Linehan A, O’Reilly M, McDermott R and O’Kane GM (2024) Targeting KRAS mutations in pancreatic cancer: opportunities for future strategies. Front. Med. 11:1369136. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1369136

Edited by:

Alice Chen, Consultant, Potomac, MD, United StatesReviewed by:

Wenzheng Guo, University of Kentucky, United StatesJin Wu, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, United States

Copyright © 2024 Linehan, O’Reilly, McDermott and O’Kane. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Grainne M. O’Kane, R09LYW5lQHN0amFtZXMuaWU=

Anna Linehan

Anna Linehan Mary O’Reilly1

Mary O’Reilly1 Grainne M. O’Kane

Grainne M. O’Kane