94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

CASE REPORT article

Front. Med. , 11 March 2024

Sec. Gastroenterology

Volume 11 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1303305

Colonoscopy is widely acknowledged as a prevalent and efficacious approach for the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. In order to guarantee an effective colonoscopy, it is imperative for patients to undergo an optimal bowel preparation regimen. This entails the consumption of a substantial volume of a non-absorbable solution to comprehensively purge the colon of any fecal residue. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy to acknowledge that the bowel preparation procedure may occasionally elicit adverse symptoms such as nausea and vomiting. In exceptional instances, the occurrence of excessive vomiting may lead to the rupture of the distal esophagus, a grave medical condition referred to as Boerhaave syndrome (BS). Timely identification and efficient intervention are imperative for the management of this infrequent yet potentially perilous ailment. This investigation presents a case study of a patient who developed BS subsequent to the ingestion of mannitol during bowel preparation. Furthermore, an exhaustive examination of extant case reports and pertinent literature on esophageal perforation linked to colonoscopy has been conducted. This analysis provides valuable insights into the prevention, reduction, and treatment of such serious complications.

Boerhaave syndrome (BS) is an infrequent yet perilous ailment precipitated by an abrupt surge in negative intrathoracic pressure and intraesophageal pressure (1), culminating in an unanticipated esophageal perforation. Appropriate intervention is imperative to avert the elevated mortality rates linked to this serious condition (2, 3). Esophageal perforation exhibits a substantial fatality rate, which escalates to 75–89% when therapeutic measures are postponed beyond 48 h (4). Prior investigations have indicated that individuals afflicted with eosinophilic esophagitis, medication-induced esophagitis, ileus, Barrett’s esophagus, childbirth, seizure, weightlifting or experiencing recurrent vomiting are more susceptible to the development of BS (5–7). Herein, we report the case of BS due to intestinal preparation.

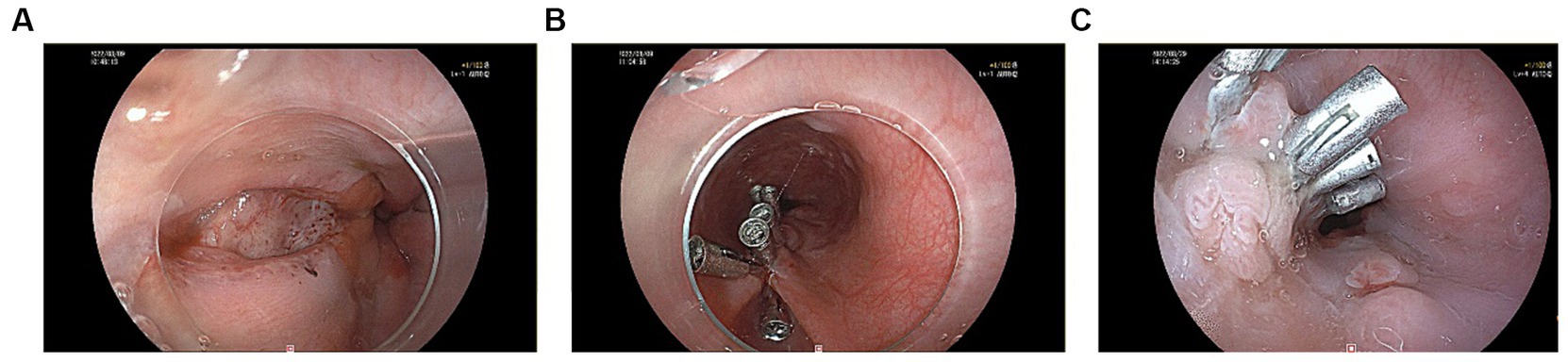

A 60-year-old male patient, who was in a state of good health with no significant medical or familial history and no specific complaints, had been scheduled for a screening colonoscopy. The patient started bowel preparation at around 22:00 pm and finished consuming 250 mL of mannitol and 2 L of water at around 01:00 am. Half an hour later, the patient vomited twice and then developed symptoms such as upper abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and chest tightness. Upon physical examination, decreased breath sounds and dullness upon percussion were observed over the left lower lung without jugular venous distention and cardiac murmurs. Laboratory studies revealed elevated inflammatory markers [White Bloodcell Count (WBC) 16.88×109/L, hypersensitive C-Reactive Protein (hsCRP) 44 mg/L, Procalcitonin (PCT) 3.03 ng/mL]. Furthermore, biochemical examination showed no abnormal electrolytes or liver and renal function. A thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan revealed the presence of an esophageal-mediastinum fistula and pleural effusion on the left side (Figure 1). A diagnosis of BS was strongly suspected, leading to the immediate performance of gastroscopy in case of stable vital signs. The patient underwent gastroscopy at around 10:30 am, during the procedure, a longitudinal laceration (length approximately 50 mm) was observed in the esophagus, specifically located from 35 cm from the incisors to the cardia on the lesser curvature side, which was suspected to be the site of perforation (Figure 2A). Closure of the defect was accomplished using a total of 6 titanium clips (Figure 2B). Time line of events from start of prep to diagnosis and intervention as show as Figure 3. After surgery, patient was hemodynamically stable and transferred to the general ward. Following continuous left chest drainage, administration of anti-infection measures, and nutritional support, a re-examination of the gastroscope conducted 20 days after hospitalization revealed a well-closed, scar-like hyperplasia at the site of the initial rupture in the lower esophagus (Figure 2C). Repeat thoracic CT showed resolution of pleural effusion (Figure 4). Laboratory test revealed 5.06 × 109/L WBC, 12 mg/L hsCRP and 0.04 ng/mL PCT, respectively. He recovered well and was discharged from hospital 3 weeks later.

Figure 2. (A) A longitudinal laceration located in the esophagus was seen under gastroscopy. (B) Clamping the esophageal chasm with 6 titanium clips. (C) A well-closed, scar-like hyperplasia at the site of the primary rupture of the lower esophagus.

We searched the literature in the databases Google Scholar, Medline, Web of Science, Embase, and Embase using keywords such as esophageal perforation, Boerhaave syndrome, bowel preparation, colonoscopy and complication. Few studies of esophageal rupture associated with colonoscopy and bowel preparation have been published (8–17). Herein we have reported these studies’ demographic features, symptoms, location of esophageal rupture, length of the laceration, diagnostic method, imaging findings, treatment and outcome in the following Table 1.

BS arises from a sudden increase in intraluminal pressure within the esophagus, resulting in a longitudinal laceration in the esophagus, with sizes ranging from 0.6 cm to 8.9 cm (18). During the process of bowel preparation, excessive intake of fluids can induce severe vomiting. At this point, pylorospasm may contribute to a delay in gastric emptying. Concurrently, powerful contraction of the abdominal and diaphragmatic muscles leads to a rapid elevation in intra-abdominal pressure. If esophageal spasms occur during the vomiting process, the gastric contents cannot be expelled, thereby causing a sudden rise in esophageal pressure and subsequent rupture. The anatomy of the esophagus is unique. In humans, the upper third is composed of skeletal muscle, the middle third is composed of mixed skeletal and smooth muscle, and only the distal third is composed of smooth muscle (19). Because of the presence of the smooth muscle layer at the distal esophagus, the tendency to retain food in this location and the fact that the distal esophagus lies below the left diaphragm, rupture of the esophagus is more likely to occur on the left side of the distal esophagus (20, 21).

Elderly persons are reported to have a higher risk of complications (such as cardiovascular/pulmonary complications, perforation, bleeding and mortality) during and after colonoscopy (22). However, it remains unclear whether esophageal perforation during the bowel preparation process is age-related. Previous reports and this case study have demonstrated a total of 9 cases experiencing esophageal rupture during bowel preparation and 3 cases during colonoscopy procedure. Based on our consolidated data, esophageal rupture during colonoscopy procedure and bowel preparation appears to be relatively more common in males (91.67%) and elderly persons (median age 71.5, range 48–85). The rupture is usually (in 90% of cases) in the lower third of the esophagus and in the left lateral position, longitudinal laceration sizes median 2.25 cm (ranging 1.5–5) (Table 1). One published case has been documented regarding esophageal rupture located in the right wall during the bowel preparation (9).

Once the esophagus is perforated, residual gastric contents, saliva, bile, and other secretions may enter the mediastinum, leading to chemical mediastinitis accompanied by mediastinal emphysema, inflammation, and subsequent mediastinal necrosis. Esophageal rupture is primarily manifested clinically as severe vomiting following binge eating or alcohol abuse, chest pain and tightness, radiating shoulder pain, dyspnea and respiratory distress, subcutaneous emphysema, fever, hematemesis and abdominal pain. Boerhaave syndrome is often misdiagnosed as peptic ulcer, acute pancreatitis, or myocardial infarction due to its rarity and nonspecific symptoms (1). Among the 12 integrated case reports in this article, 9 cases (75%) presented with vomiting, 7 cases (58%) experienced abdominal pain, 7 cases (58%) had difficulty breathing or shortness of breath, and 6 cases (50%) reported chest pain. We suggest that vomiting, abdominal pain, chest pain and difficulty breathing or shortness of breath be considered red flags, as they manifest in at least 50% of Boerhaave syndrome cases.

Chest X-rays, CT scans, esophagography, or endoscopic examinations can provide diagnostic information on esophageal perforation. On chest X-ray, findings suggestive of esophageal perforation include free gas in the peritoneal cavity, pneumomediastinum, or subcutaneous emphysema. However, chest X-ray has limited sensitivity for detecting esophageal perforation (5). For patients who are not suitable for invasive examinations, consider performing esophagography, as leakage of the contrast agent serves as a reliable indicator for confirming the diagnosis of perforation. The choice of contrast agents for esophagography include water-soluble contrast (such as meglumine diatrizoate) and barium contrast. Compared to water-soluble contrast, barium contrast has a better performance for smaller perforations, and it can detect 60–90% of esophageal perforations (23). However, due to the potential for barium contrast to cause mediastinal or pleural cavity inflammatory reactions, it is generally preferred to use water-soluble contrast (24). Additionally, chest CT scans are also an effective method for diagnosing esophageal perforation. A CT scan of the chest revealed periesophageal fluid accumulation, thickening of esophageal wall with oedema, effusion and gas in pleural and peritoneal cavities, compatible with an esophageal perforation (25–27). However, small esophageal perforations may present as negative findings on CT scans, as the swollen esophageal wall may close the fistula orifice. For stable patients with no suppurative complications, we can perform an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (28). Endoscopy allows direct visualization of the specific site and size of the esophageal perforation. The role of endoscopy in the diagnosis of spontaneous esophageal perforation is controversial, as the endoscopic procedure can extend the perforation and introduce air into the mediastinum (29).

The mortality rate is high in cases of esophageal rupture. Early and definitive diagnosis leads to specific treatment, which can improve prognosis. In a report of 12 cases, 8 cases (66.7%) underwent surgical treatment, recovered well and was discharged from hospital 11 days to 2 months later. 2 cases (16.7%) underwent endoscopic titanium clip closure, our case showing improvement and being discharged after 3 weeks, and the other case showing significant improvement on chest CT a few days later, with no contrast agent leakage on esophagography (9). Two cases (16.7%) of patients with poor general condition were treated conservatively, and one of them died within 36 h after conservative management (14). The other patient restarted eating by mouth 2 months after the colonoscopy (13). For patients with esophageal rupture, it is crucial to develop urgent and personalized treatment plans. Treatment options include conservative management, endoscopic intervention, or surgical approaches. Conservative management is suitable for patients with mild symptoms or poor general condition who cannot tolerate surgery or endoscopic examination. For patients with stable conditions or those unlikely to tolerate surgery, endoscopic treatment should be considered (30–32). Common endoscopic interventions include self-expanding stents (included metal stents and plastic stents) (28, 33–35), endoscopic negative pressure therapy (ENPT) (36), endoluminal vacuum therapy (31), endoscopic suturing, esophageal resection, through-the-scope (TTS) clips, over-the-scope (OTS) clips and diversion (37). The treatment of patients should be personalized based on their condition, the extent of the disease, and the timing of symptom onset.

As a rare but serious complication, Boerhaave syndrome following colonoscopy procedure or bowel preparation may worsen the prognosis of patients. Therefore, several strategies have been proposed to reduce the esophageal rupture. PEG electrolyte solution is widely used for bowel preparation (38), and nausea is a common side effect (39). Due to the large volume of solution required for colon cleansing, which increases the likelihood of vomiting. Esophageal rupture is more commonly observed in elderly males, patients with esophagitis, ileus, Barrett’s esophagus, childbirth, seizure, weightlifting or esophageal hiatal hernia. Firstly, in this high-risk patient population, administering PEG electrolyte solution via a nasogastric tube prior to colonoscopy may help prevent this complication. We believe that anti-emetic medication during the bowel preparation process may potentially reduce the incidence of this complications in high-risk individuals (12). Additionally, patients should be advised to discontinue the consumption of PEG electrolyte solution if they experience vomiting. Secondly, we can reduce the complications by minimizing the intake of PEG. Relevant studies have indicated that there is no significant difference in bowel cleansing efficacy between orally consuming 1 L PEG with linaclotide and consuming 2 L PEG (40). However, patients in the 1 L PEG with linaclotide group reported less nausea and vomiting (40). In addition, slowing down the intake speed of liquids can also reduce the occurrence of such symptoms. Thirdly, we can choose bowel cleansing agents that are more better tolerated in elderly patients. There are various bowel cleansing agents available for bowel preparation, such as magnesium sulfate solution (MSS), magnesium citrate, lactulose, mannitol, sodium phosphate and sodium picosulfate (41–46). A study involving 1,174 patients demonstrated that low-dose of MSS is non-inferior to the standard PEG regimen in terms of bowel preparation quality for elderly and MSS offers fewer nausea, vomiting and better tolerability (41).

For patients who experience nausea, vomiting, and subsequent chest or abdominal pain during the bowel preparation process or colonoscopy, we should promptly consider the possibility of spontaneous esophageal rupture. Early intervention and treatment can lead to favorable outcomes for patients. For certain high-risk individuals, appropriate measures can be taken to minimize the occurrence of such complications.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

R-yG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. X-lW: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. J-fW: Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Z-wZ: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. X-qY: Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. X-qY was supported by Shenzhen Science and Technology Research and Development Fund, No. JSGG20210802153548040. J-fW was supported by Shenzhen Luohu District Science and Technology Innovation Bureau Soft Science Research Project, No. LX20211306.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2024.1303305/full#supplementary-material

1. Bjerke, HS . Boerhaave's syndrome and barogenic injuries of the esophagus. Chest Surg Clin N Am. (1994) 4:819–25.

2. Yan, XL, Jing, L, Guo, LJ, Huo, YK, Zhang, YC, Yan, XW, et al. Surgical management of Boerhaave's syndrome with early and delayed diagnosis in adults: a retrospective study of 88 patients. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. (2020) 112:669–74. doi: 10.17235/reed.2020.6746/2019

3. Brauer, RB, Liebermann-Meffert, D, Stein, HJ, Bartels, H, and Siewert, JR. Boerhaave's syndrome: analysis of the literature and report of 18 new cases. Dis Esophagus. (1997) 10:64–8. doi: 10.1093/dote/10.1.64

4. Huber-Lang, M, Henne-Bruns, D, Schmitz, B, and Wuerl, P. Esophageal perforation: principles of diagnosis and surgical management. Surg Today. (2006) 36:332–40. doi: 10.1007/s00595-005-3158-5

5. Pate, JW, Walker, WA, Cole, FH Jr, Owen, EW, and Johnson, WH. Spontaneous rupture of the esophagus: a 30-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg. (1989) 47:689–92. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(89)90119-7

6. Herbella, FA, Matone, J, and Del Grande, JC. Eponyms in esophageal surgery, part 2. Dis Esophagus. (2005) 18:4–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2005.00447.x

7. He, F, Dai, M, Zhou, J, He, J, and Ye, B. Endoscopic repair of spontaneous esophageal rupture during gastroscopy: a CARE compliant case report. Medicine (Baltimore). (2018) 97:e13422. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013422

8. Zhu, LL, Lyu, XH, Lei, TT, and Yang, JL. Occurrence of Boerhaave's syndrome after diagnostic colonoscopy: what else can emergency physicians do? World J Emerg Med. (2023) 14:85–7. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2023.006

9. Xu, H, Huang, D, and He, C. Boerhaave's syndrome with rupture of the right wall of the esophagus after oral administration of sulfate solution. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. (2021) 113:677. doi: 10.17235/reed.2020.7617/2020

10. Nishikawa, Y, Miyamoto, S', Horimatsu, T, Okabe, H, and Muto, M. Esophageal rupture associated with colonoscopy preparation. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2016) 64:682–3. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14003

11. Yu, JY, Kim, SK, Jang, EC, Yeom, JO, Kim, SY, and Cho, YS. Boerhaave's syndrome during bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol in a patient with postpolypectomy bleeding. World J Gastrointest Endosc. (2013) 5:270–2. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i5.270

12. Emmanouilidis, N, Jäger, MD, Winkler, M, and Klempnauer, J. Boerhaave syndrome as a complication of colonoscopy preparation: a case report. J Med Case Rep. (2011) 5:544. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-5-544

13. Chalumeau, C, Facy, O, Radais, F, Hueber, T, Houzé, J, and Ortega-Deballon, P. Colonoscopy-related esophageal perforation: report of two cases. Endoscopy. (2009) 41:E261. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215158

14. Aljanabi, I, Johnston, P, and Stone, G. Spontaneous rupture of the oesophagus after bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol. ANZ J Surg. (2004) 74:176–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-1433.2003.02809.x

15. Eisen, GM, and Jowell, PS. Esophageal perforation after ingestion of colon lavage solution. Am J Gastroenterol. (1995) 90:2074.

16. McBride, MA, and Vanagunas, A. Esophageal perforation associated with polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution. Gastrointest Endosc. (1993) 39:856–7. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(93)70290-4

17. Pham, T, Porter, T, and Carroll, G. A case report of Boerhaave's syndrome following colonoscopy preparation. Med J Aust. (1993) 159:708. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb138096.x

18. Kassem, MM, and Wallen, JM. Esophageal Perforation and Tears. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls (2023).

19. Mittal, RK, and Bhalla, V. Oesophageal motor functions and its disorders. Gut. (2004) 53:1536–42. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.035618

20. Velasco Hernández, DN, Horiuchi, HR, Rivaletto, LA, Farina, F, and Viscuso, M. Boerhaave's syndrome with late presentation. Experience in an argentine single center: case series. Ann Med Surg (Lond). (2019) 45:59–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2019.07.023

21. de Schipper, JP, Pull ter Gunne, AF, Oostvogel, HJM, and van Laarhoven, CJHM. Spontaneous rupture of the oesophagus: Boerhaave's syndrome in 2008. Literature review and treatment algorithm. Dig Surg. (2009) 26:1–6. doi: 10.1159/000191283

22. Day, LW, Kwon, A, Inadomi, JM, Walter, LC, and Somsouk, M. Adverse events in older patients undergoing colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. (2011) 74:885–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.023

23. Buecker, A, Wein, BB, Neuerburg, JM, and Guenther, RW. Esophageal perforation: comparison of use of aqueous and barium-containing contrast media. Radiology. (1997) 202:683–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.202.3.9051016

24. Dodds, WJ, Stewart, ET, and Vlymen, WJ. Appropriate contrast media for evaluation of esophageal disruption. Radiology. (1982) 144:439–41. doi: 10.1148/radiology.144.2.7089304

25. Backer, CL, LoCicero, J III, Hartz, RS, Donaldson, JS, and Shields, T. Computed tomography in patients with esophageal perforation. Chest. (1990) 98:1078–80. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.5.1078

26. de Lutio di Castelguidone, E, Merola, S, Pinto, A, Raissaki, M, Gagliardi, N, and Romano, L. Esophageal injuries: spectrum of multidetector row CT findings. Eur J Radiol. (2006) 59:344–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.04.027

27. Tonolini, M, and Bianco, R. Spontaneous esophageal perforation (Boerhaave syndrome): diagnosis with CT-esophagography. J Emerg Trauma Shock. (2013) 6:58–60. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.106329

28. Śnieżyński, J, Wilczyński, B, Skoczylas, T, and Wallner, GT. Successful late endoscopic stent-grafting in a patient with Boerhaave syndrome. Am J Case Rep. (2021) 22:e931629. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.931629

29. Gubbins, GP, Nensey, YM, Schubert, TT, and Batra, SK. Barogenic perforation of the esophagus distal to a stricture after endoscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. (1990) 12:310–2. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199006000-00016

30. Schweigert, M, Beattie, R, Solymosi, N, Booth, K, Dubecz, A, Muir, A, et al. Endoscopic stent insertion versus primary operative management for spontaneous rupture of the esophagus (Boerhaave syndrome): an international study comparing the outcome. Am Surg. (2013) 79:634–40. doi: 10.1177/000313481307900627

31. Still, S, Mencio, M, Ontiveros, E, Burdick, J, and Leeds, SG. Primary and rescue Endoluminal vacuum therapy in the Management of Esophageal Perforations and Leaks. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. (2018) 24:173–9. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.17-00107

32. Tellechea, JI, Gonzalez, JM, Miranda-García, P, Culetto, A, D’Journo, XB, Thomas, PA, et al. Role of endoscopy in the Management of Boerhaave Syndrome. Clin Endosc. (2018) 51:186–91. doi: 10.5946/ce.2017.043

33. Dasari, BV, Neely, D, Kennedy, A, Spence, G, Rice, P, Mackle, E, et al. The role of esophageal stents in the management of esophageal anastomotic leaks and benign esophageal perforations. Ann Surg. (2014) 259:852–60. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000564

34. Siersema, PD, Homs, MYV, Haringsma, J, Tilanus, HW, and Kuipers, EJ. Use of large-diameter metallic stents to seal traumatic nonmalignant perforations of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. (2003) 58:356–61. doi: 10.1067/S0016-5107(03)00008-7

35. Gelbmann, CM, Ratiu, NL, Rath, HC, Rogler, G, Lock, G, Schölmerich, J, et al. Use of self-expandable plastic stents for the treatment of esophageal perforations and symptomatic anastomotic leaks. Endoscopy. (2004) 36:695–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825656

36. Loske, G, Albers, K, and Mueller, CT. Endoscopic negative pressure therapy (ENPT) of a spontaneous oesophageal rupture (Boerhaave's syndrome) with peritonitis – a new treatment option. Innov Surg Sci. (2021) 6:81–6. doi: 10.1515/iss-2020-0043

37. Barakat, MT, Girotra, M, and Banerjee, S. (re)building the wall: recurrent Boerhaave syndrome managed by over-the-scope clip and covered metallic stent placement. Dig Dis Sci. (2018) 63:1139–42. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4756-y

38. Marshall, JB, Barthel, JS, and King, PD. Short report: prospective, randomized trial comparing a single dose sodium phosphate regimen with PEG-electrolyte lavage for colonoscopy preparation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (1993) 7:679–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1993.tb00150.x

39. Hur, GY, Lee, SY, Shim, JJ, In, KH, Kang, KH, and Yoo, SH. Aspiration pneumonia due to polyethylene glycol-electrolyte solution (Golytely) treated by bronchoalveolar lavage. Respirology. (2008) 13:152–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2007.01209.x

40. Zhang, C, Chen, X, Tang, B, Shan, J, Qin, J, He, J, et al. A novel ultra-low-volume regimen combining 1 L polyethylene glycol and linaclotide versus 2 L polyethylene glycol for colonoscopy cleansing in low-risk individuals: a randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. (2023) 97:952–961.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2022.12.015

41. Ge, F, Kang, X, Wang, Z, Zhu, H, Liao, L, Wang, M, et al. Low-dose of magnesium sulfate solution was not inferior to standard regime of polyethylene glycol for bowel preparation in elderly patients: a randomized, controlled study. Scand J Gastroenterol. (2023) 58:94–100. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2022.2106154

42. Li, CX, Guo, Y, Zhu, Y-J, Zhu, J-R, Xiao, Q-S, Chen, D-F, et al. Comparison of polyethylene glycol versus lactulose Oral solution for bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. (2019) 2019:2651450. doi: 10.1155/2019/2651450

43. Spada, C, Fiori, G, Uebel, P, Tontini, GE, Cesaro, P, Grazioli, LM, et al. Oral mannitol for bowel preparation: a dose-finding phase II study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. (2022) 78:1991–2002. doi: 10.1007/s00228-022-03405-z

44. Yao-dong, L, Yi-ping, W, Gang, M, Yang-yun, H, Ling-ling, Z, Hong, D, et al. Comparison of oral sodium phosphate tablets and polyethylene glycol lavage solution for colonoscopy preparation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Front Med (Lausanne). (2023) 10:1088630. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1088630

45. Vissoci, CM, Santos, GT, Duarte, RP, Pinheiro, CGDOA, Silva, FMMDA, Pires, VP, et al. Comparative study between manitol and sodium picosulfate with magnesium oxide solutions in the preparation for colonoscopy. Rev Col Bras Cir. (2022) 49:e20222476. doi: 10.1590/0100-6991e-20222476-en

46. Bor, R, Matuz, M, Fabián, A, Szepes, Z, Szántó, K, Farkas, K, et al. Efficacy, tolerability and safety of a split-dose bowel cleansing regimen of magnesium citrate with sodium picosulfate – a phase IV clinical observational study. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. (2021) 113:635–42. doi: 10.17235/reed.2020.7073/2020

Keywords: Boerhaave syndrome, colonoscopy, bowel preparation, treatment option, mannitol

Citation: Gao R-y, Wei X-l, Wu J-f, Zhou Z-w and Yu X-q (2024) The perilous consequences of bowel preparation: a case study with literature review of Boerhaave syndrome. Front. Med. 11:1303305. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1303305

Received: 27 September 2023; Accepted: 26 January 2024;

Published: 11 March 2024.

Edited by:

Mengfei Liu, Yale University, United StatesReviewed by:

Tanureet Kochar, The Wright Center, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Gao, Wei, Wu, Zhou and Yu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xi-qiu Yu, eXVlcjIwMDQ3MEAxMjYuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.