94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Med., 17 February 2023

Sec. Gastroenterology

Volume 10 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.997440

This article is part of the Research TopicReviews in GastroenterologyView all 10 articles

Erfan Arabpour1*

Erfan Arabpour1* Sina Khoshdel2

Sina Khoshdel2 Ali Akhgarzad2

Ali Akhgarzad2 Mohammadamin Abdi3

Mohammadamin Abdi3 Negin Tabatabaie2

Negin Tabatabaie2 Dorsa Alijanzadeh3

Dorsa Alijanzadeh3 Mohammad Abdehagh1*

Mohammad Abdehagh1*Background: The main components of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) management include a combination of medications and lifestyle modifications; Nevertheless, based on the severity of symptoms and their response to medications, other treatments could be considered. Baclofen has been demonstrated in studies to relieve GERD symptoms. The current study aimed to precisely address the effects of baclofen on the treatment of GERD and its characteristics.

Methods: A systematic search was carried out in Pubmed/Medline, Cochrane CENTRAL, Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and clinicaltrials.gov up to December 10, 2021. The search terms included baclofen, GABA agonists, GERD, and reflux.

Results: We selected 26 papers that matched the inclusion criteria after examining 727 records. Studies were classified into four categories based on the study population and reported outcomes: (1) adults, (2) children, (3) patients with gastroesophageal reflux-induced chronic cough, (4) hiatal hernia patients. The results revealed that baclofen can significantly improve reflux symptoms and pH-monitoring and manometry findings to different degrees in all four mentioned categories; although its effect on pH-monitoring parameters seems less significant than the other parameters. Mild neurological and mental status deterioration were the most reported side effects. However, side effects occurred in a portion of less than 5% of short-term users and nearly 20% of long-term users.

Conclusion: In PPI-resistant patients, a trial of adding baclofen to the PPI may be helpful. Baclofen therapies may be more beneficial for symptomatic GERD patients who also report concurrent conditions including alcohol use disorder, non-acid reflux, or obesity.

Systematic review registration: https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a clinical condition caused by the chronic retrograde reflux of acidic contents of the stomach into the esophagus with discomforting symptoms or complications or both (1). Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is a physiological condition during infancy and childhood and may not require treatment. In children, GERD is the symptomatic reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus and should be treated according to the severity of symptoms (2, 3). Global surveys in 2017 estimated an 18.1% increase in the total prevalence of GERD cases and a 67.1% increase in the years lived with disability (YLD) compared to 1990 (4). These findings suggest GERD as a public health concern with a considerable socioeconomic burden in the near future.

Diagnosis of GERD is based on clinical symptoms (heartburn, regurgitation, and non-cardiac chest pain) and response to empiric proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Nonetheless, studies have shown limitations of non-objective diagnosis; as a result, diagnostic evaluation such as upper endoscopy is recommended based on the clinical setting, especially in patients with red flags like dysphagia (5).

The main components of GERD management are lifestyle modification and PPIs. Nevertheless, based on the severity of symptoms and their response to PPIs, H2blockers, baclofen, antacids, sucralfate, prokinetic agents, and invasive anti-reflux procedures (such as surgeries, sphincter augmentation, and endoscopic therapy) are considered in combination with other treatments or as the replacement therapy for patients. Consideration is required based on efficacy and tolerability profile of each treatment option (5–7).

The pathophysiology of GERD is multifactorial and is explained by natural anti-reflux barrier. Studies suggest following mechanisms for GERD: the hypotonic lower esophageal sphincter (LES), hiatal hernia, Gubaroff valve failure, and thoraco-abdominal pressure (8, 9). Also, studies have shown that baclofen has been highly beneficial in the treatment of refractory GERD. Baclofen is an FDA-approved agonist of the gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor, which is generally used for the relaxation of pathologic spasms originating from the central nervous system (CNS). Its mechanism of action on GERD is by inhibition of LES relaxation induced via vasovagal reflexes. Baclofen inhibits these reflexes through GABAB receptor activation (10, 11).

Although previous studies proved effectiveness of baclofen on GERD (12), to the date, there are no systematic reviews regarding outcomes and side effects in different patient (grouped by: age, and comorbidities); A systematic review in that regard might resolve probable hesitancies in prescribing baclofen. Therefore, we will conduct this systematic review, aiming to facilitate informed decisions in managing GERD using baclofen. To achieve this goal we will review efficacy, side effects, and response predictors in different patients grouped by: age (adult vs. pediatrics), comorbidities (hiatal hernia and GERD-related chronic cough), and some other factors.

This study was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reported Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement (13).

We searched Pubmed/Medline, Cochrane CENTRAL, Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Clinicaltrials.gov for studies reporting the efficacy/effectiveness of baclofen in patients with GERD, published up to December 10, 2021. The search terms were baclofen, GABA agonists, GERD, and reflux. No language restrictions were imposed.

The records found through database searching were merged, and the duplicates were removed using EndNote X9. Two authors independently screened the records by title/abstract and full-texts to exclude those unrelated to the study topic. Included studies met the following inclusion criteria: (i) patients were diagnosed with GERD based on a defined criterion; (ii) patients were treated with baclofen; and (iii) treatment outcomes were recorded. Conference abstracts, reviews, experimental studies on animal models, and articles that their full-text or original data were not available were excluded.

Two authors designed a data extraction form. These reviewers extracted the following items from all eligible studies: first author’s name, year of publication, country/ies where the research was conducted, type of epidemiological study, demographics, treatment protocols, adverse effects, and outcomes. Data was inserted into an excel sheet, and differences were resolved by consensus.

The checklists provided by the National Institute of Health (NIH) for controlled intervention and before-after (pre-post) studies with no control group were used to perform the quality assessment (14).

We investigated a total of 952 records found in the systematic search; after removing duplicates and full-text reviews, 26 were chosen. Studies included and excluded through the review process are summarized in Figure 1 and Supplementary Table 1. Among the included studies, there were 9 crossover RCTs, 8 RCTs, and 9 single-arm clinical trials. The studies originated from twelve countries: United States (n = 6), China (n = 4), Iran (n = 3), Australia, Belgium, Italy, Sweden (n = 2, for each one), Switzerland, the Netherlands, Mexico, Japan, and Germany (n = 1, for each one) (Table 1). Two of the studies had two separate parts (15, 16), so we looked at these parts separately and overviewed 28 studies as a whole. All studies assessed baclofen efficacy based on clinical status, pH monitoring, or manometry findings. Additionally, in most trials, the safety of treatment was evaluated by the occurrence of adverse events or side effects.

Based on the NIH checklists for controlled intervention and before-after (pre-post) studies with no control group, the included studies had a low risk of bias (Supplementary Tables 2, 3).

Except for one study that did not report the number of patients (17), the remaining 27 trials included 785 patients who got baclofen and 358 who received control medication. The baclofen groups included individuals aged 7.1 months (infants) to 58 years (adults). The most frequently utilized methods for diagnosing GERD were, in order, history, pH monitoring, manometry, and endoscopy (Table 2).

In twenty-two studies, the treatment regimen consisted only of baclofen, whereas in the six remaining studies, the treatment regimen consisted of baclofen and a PPI (18–23). The majority of studies used baclofen for at least 1 week; however, some used shorter treatment periods to investigate baclofen’s acute effects. In all studies, treatments were administered orally, except one that also administered enteric baclofen (24) (Table 3).

Among 28 studies, four studies did not investigate treatment side effects (17, 25–27). No treatment-related severe adverse events were observed in the remaining 24 studies. The adverse effects noted were somnolence among 14.2% of participants, dizziness (10.0%), fatigue (4.9%), nausea (1.6%), gastrointestinal symptoms (0.9%), headache (0.7%), anxiety (0.2%), and a slight reduction in muscular tone (0.2%). The most frequently reported adverse effects were neurological and mental status deterioration (particularly dizziness and somnolence). However, some of these events were not induced by baclofen; rather, they were caused by the other underlying comorbidities. The side effects occurred in a portion of less than 5% of short-term users (less than 4 weeks) and nearly 20% of long-term users (more than 4 weeks), and also occurred during placebo therapy in certain studies. Baclofen had no adverse effects in seven studies, and was well tolerated (11, 16, 18, 21, 28–30) (Table 4).

Studies were classified into four categories based on the study population and reported outcomes: (1) adults, (2) children, (3) patients with gastroesophageal reflux-induced chronic cough, and (4) hiatal hernia patients.

This category contained seventeen studies. These publications evaluated baclofen’s efficacy using changes in clinical status, acid reflux time, TLESR incidence, GER incidence, LES pressure, and some other parameters.

Eleven trials reported changes in clinical status. Baclofen significantly improved clinical symptoms in seven studies. However, Bajbouj et al. (19) and Zhang et al. (11) discovered no significant improvement following baclofen treatment. According to Abbasinazari et al. (18) baclofen alleviated esophageal symptoms (heartburn and regurgitation) but had no significant effect on extra-esophageal symptoms (chest pain and hoarseness). Baclofen reduced belching with no effect on other reflux symptoms in Cange et al.’s (31) trial.

Changes in acid reflux time were documented in eleven studies. Baclofen significantly decreased acid reflux time in five studies. However, four studies found that baclofen has no significant effect on acid reflux time (11, 15, 19, 20). Orr et al. (30) reported that baclofen reduced recumbent acid contact time by 50% compared to placebo, although the difference was not statistically significant. In Curcic et al.’s (28) study, baclofen increased reflux duration by a small but significant degree.

Four studies reported changes in TLESR incidence. All of them mentioned that baclofen has a significant reducing effect on TLESR incidence (11, 32–34).

Thirteen studies reported changes in GER incidence. All of them declared baclofen had a significant effect on reducing GER incidence, except for two studies: (a) Koek et al. (20) reported that after adding baclofen, the number of acid reflux episodes remained unchanged, but the number of duodenal reflux episodes and the number of duodenal reflux episodes lasting longer than 5 min decreased significantly. (b) Bajbouj et al. (19) observed no significant changes in reflux episodes, before and after adding baclofen. Additionally, two trials examined the effect of body posture on efficacy of baclofen (15, 25). Both of them suggested that baclofen decreased reflux episodes in the upright position significantly, while reflux episodes in the supine position did not change significantly.

Six studies investigated changes in LES pressure. Baclofen significantly elevated LES pressure in four studies (11, 28, 32, 33). Cossentino et al. (25) and van Herwaarden et al. (34) on the other hand, found no difference in LES pressure between the baclofen and placebo groups. All outcomes are present in more detail in Table 5.

Six studies were included in this category. The mean age of the participants ranged between 7.1 months and 10.0 years.

Four studies reported changes in clinical status. All of them confirmed baclofen’s significant efficacy in the improvement of clinical status by symptom remission, weight gain, or reduction in crying and restlessness.

Three studies evaluated the efficacy of baclofen in children using invasive GI procedures (pH monitoring or esophageal manometry). Omari et al. (35) and Dibner (17) found that children receiving baclofen had considerably lower TLESR and acid GER compared to children receiving a placebo. In Kawai et al.’s (24) study, the total number of acid reflux events was reduced significantly during the postprandial and entire 24-h periods. However, they found no significant changes in total acid exposure time, the percentage of time with esophageal pH < 4 and the duration of the longest acid reflux resulting from baclofen (24) (Table 6).

In this category, four studies were included. Cough period ranged from 12.6 to 36 months on average. The daytime cough symptom score was greater (3, 4) than the night time cough symptom score (1, 2). Overall, baclofen was effective in treating GERC in 122 of 214 (57.0%) individuals. Outcomes are available in more detail in Table 7.

Three studies were included in this category because they featured a subgroup of patients with HH. Cange et al. (31) reported a significant reduction in acid reflux time and reflux episodes after receiving baclofen, compared to placebo. Beaumont et al. (15) found no significant changes in total acid exposure time and the percentage of time with pH < 4 in patients with HH after administration of baclofen and placebo. However, they observed that baclofen reduced the total number of reflux episodes compared to placebo. In addition, they made a comparison between patients with and without HH and found: (I) patients with a large HH did not show a significantly more proximal reflux compared to patients without HH. No correlation was found between the size of the HH and the proximal extent of the reflux (r = 0.1; P = 0.75); (II). The total number of reflux episodes of placebo was significantly higher in patients with HH and remained significantly higher compared to in patients without HH (P < 0.05). No correlation (r = 0.01; P = 0.95) was found between the size of the HH and the number of acid reflux episodes (15). In Scarpellini et al.’s (33) study, preprandial LES pressures following baclofen were significantly lower in patients with HH compared to those without HH (P < 0.05), and did not change significantly in the postprandial period (Table 8).

Table 9 summarizes the evidence from the included studies regarding the feasibility of using baclofen in the treatment of GERD.

We conducted this study to review the effects of baclofen on the treatment of GERD along with its advantages and disadvantages. Most included studies we reviewed diagnosed GERD based on clinical presentation and only a few diagnosed on pH-monitoring results. The results showed that baclofen is a relatively safe choice that may significantly improve reflux symptoms and pH-monitoring and manometry findings, although its effect on pH-monitoring parameters seems less significant than the other parameters. Baclofen showed effective to different degrees in all of four assessed categories (including adults, children, patients with GERC, and patients with HH).

The mechanisms, safety, and efficacy of baclofen in the GERD management will be discussed in the following sections.

Baclofen is a GABA agonist that works primarily in the spinal cord by binding to GABAB receptors and inhibits the release of substance P and excitatory neurotransmitters; so, baclofen alleviates muscle spasms and discomfort (36). Although the spinal cord is the principal site of action for baclofen, its receptors are also found in the brain. Studies suggest that baclofen interacts with serotonin, dopamine, and other neurotransmitters, an off-label treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety (37).

However, how does baclofen work to treat gastroesophageal reflux? The molecular and neural mechanisms of action of baclofen in reflux disease are still unclear. The vasovagal reflex relaxes the LES as food enters the stomach, but predisposes to acid and food reflux to occur. As a result, the TLESR is the most likely cause for the gastroesophageal reflux disease. Number of neurotransmitters play a role in this reflex, but GABAB receptor agonists have received the most attention for drug intervention. A low basal pressure of the LES is another proposed mechanism for reflux disease (38, 39). All included clinical trials reported the significant effect of baclofen on TLESRs and LES pressure, except for Cossentino et al. (25) and van Herwaarden et al. (34) who found no significant change in LES pressure between the baclofen and placebo groups. They prescribed baclofen for a period of 2 weeks and 1 day, respectively. Their result does not seem to be attributable to the period of baclofen administration, since there are some studies reporting the efficacy of baclofen on LES pressure during the same administration period (11, 28, 32, 33).

There are still many questions about the mechanism of baclofen in GERD. Although the manometry findings confirm the effect of baclofen on the LES, baclofen has been less effective on pH-monitoring findings. Unlike PPIs, baclofen has no known effect on gastric acid secretion, but theoretically, it may reduce acid exposure time secondary to increased LES pressure. However, most of the studies reported no significant improvement in acid exposure time with baclofen. Furthermore, in some of these studies, despite no significant reduction in acid exposure time, GERD symptoms were significantly improved. This can suggest other mechanisms rather than the effect on the LES; for example, baclofen may have a role in suppressing esophageal sensory neurons, as a result, despite the reflux of the acid, patient feels no heartburn. Taken together, it seems that the increased LES pressure cannot be the only mechanism of action of baclofen in GERD; more studies are needed in this field.

One of the most critical considerations in any treatment is the patient’s safety. Baclofen’s side effects have caused hesitancies in prescribing for the treatment of GERD.

As previously mentioned, baclofen is a GABAB agonist which justifies its side effects by this mechanism. CNS side effects may include dizziness, drowsiness, confusion, sedation, asthenia, and nausea. These side effects are dose-dependent and related to the pharmacologic action of binding to the presynaptic GABAB receptors within the brain stem, dorsal horn of the spinal cord, and other CNS parts while reducing the release of excitatory neurotransmitters. Taking oral doses of more than 60 mg per day and severe renal impairment (eGFR less than 30 ml/minute/1.73 m2) are the major predictors for CNS side effects. Patients who are concurrently taking other CNS depressants (for example, benzodiazepines or opioids) are more susceptible to these side effects (40, 41).

As expected, these side effects were also observed in the clinical trials. These side effects were well explained both by the agonistic effects of baclofen on GABAB receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems and the normal postprandial symptoms of GERD. The duration of the treatment and other factors may have an impact on its safety. We review that in short -term use the overall adverse effects of baclofen in GERD patients are negligible, yet in long-term use side effects are more prominent. However, Sobhani Shahmirzadi et al. (21) and Khodad et al. (29) administered baclofen for a period of 1 month and 3 months, respectively; and no significant adverse event was observed despite long-term use of baclofen.

Li et al. (12) conducted a meta-analysis of nine RCTs to examine the safety of baclofen in reflux therapy. Baclofen- and placebo-treated participants did not have a statistically significant difference in the frequency of overall adverse events (OR = 1.62; 95% CI: 1.03, 2.54; P = 0.04). Neurological/psychiatric symptoms were the most reported side effects. All reported adverse events were mild to moderate in intensity (12).

Some clinicians administer low dose baclofen and increment the dosage as a precaution against baclofen adverse effects. This approach was utilized in six of our trials (15, 16, 19, 20, 25, 42). However, results are inconclusive due to lack of studies comparing high-dose baclofen at the beginning of treatment with the incremental dosing mentioned above in adverse effects.

This review concludes an acceptable safety and tolerability profile for baclofen in GERD, yet Caution should be taken in the long-term use of baclofen, as 20% of long-term users experienced neurological and mental side effects. We noted that some trials did not report side effects, and some had restricted criteria toward side effects; therefore, side effects might not be reported in these studies. Furthermore, the populations of the included studies were heterogeneous. Thus, we recommend that cautions should be considered when administering baclofen to susceptible populations. In general, to limit the risk of baclofen side effects, we recommend: (i) starting with a low dose and gradually increasing it; (ii) prescribing no more than 60 mg of baclofen per day; and (iii) obtaining a comprehensive history of the patient, including comorbidities, medications (particularly CNS depressants) and a previous history of dizziness, somnolence and other baclofen side effects.

In our included trials, the efficacy of baclofen was evaluated through changes in clinical status, acid reflux time, TLESR incidence, GER incidence, LES pressure, and several other factors. Due to heterogeneity of the included studies, a meta-analysis of the data was not possible. Nonetheless, the effects of baclofen on GERD from the results are noticeable. Li et al. (12) conducted a meta-analysis on nine RCTs to determine the efficacy of baclofen on reflux statistically (eight studies administered baclofen in GERD patients and one administered baclofen in normal healthy subjects). The results revealed a statistically significant difference between baclofen-treated and placebo-treated subjects in reduction of GER incidence [standardized mean difference (SMD): −0.65; 95% CI: −0.94, −0.36; P = 0.00001], acid reflux time (SMD: −1.14; 95% CI: −1.72, −0.56; P = 00001) and TLESR incidence (SMD: −3.56; 95% CI: −4.30, −3.00; P < 0.00001) (12).

Baclofen may benefit a diverse population including: adults, infants with refractory regurgitation, neurologically impaired children with GERD, patients with GERC, and patients with hiatal hernia may benefit from baclofen. Of the twenty-six included, only Bajbouj et al. (19) and Zhu et al. (42) advised against using baclofen for the treatment of reflux disease.

The study by Bajbouj et al. (19) involved seven patients with GERD who did not respond to PPI. They added 15 mg of baclofen to the 80 mg of esomeprazole daily, which was increased to 60 mg after 1 month. They maintained this regimen for a period of 2 months. They found no significant change in patients’ clinical status, acid reflux time and GER incidence after 3 months of treatment. Also, two patients discontinued the study because of drowsiness. Therefore, Bajbouj et al. (19) recommended against the use of baclofen in patients who did not respond to PPI (19). However, in all other studies, baclofen was significantly more effective than placebo in treating GERD patients who did not respond to PPI; we cannot independently explain Bajbouj et al.’s (19) study results.

Among PPI-resistant patients, when deciding to prescribe baclofen, how to distinguish responders from non-responders? The study by Zhu et al. (42) included 138 patients with refractory GERC. In contrast to Bajbouj et al.’s (19) study, baclofen was effective in alleviating symptoms, with 72 of 138 (52.2%) GERC patients receiving a successful treatment. Nonetheless, a significant proportion of patients experienced CNS side effects as a result of long-term baclofen use, and the improvement in cough was not satisfactory. So, Zhu et al. (42) recommended against using baclofen because of its unsatisfactory efficacy and side effects. They discovered that LES pressure with a cut-off point of 11 mmHg (with a sensitivity of 83.1% and a specificity of 79.1%) and LES length with a cut-off point of 2.35 cm (with a sensitivity of 81.6% and a specificity of 72.1%) are the independent predictors of baclofen efficacy in reflux disease (42). Although the population of the study was limited to patients with refractory GERC, considering the mechanism of baclofen on GERD, it may be possible to use these cut-off points for all patients with refractory GERD; but more studies are needed to determine these cut-offs. However, using manometry to assess response to baclofen is impractical, as it is used in a limited portion of GERD patients.

Is baclofen a proper choice in patients with GERC? 64% of individuals in this category were the patients of Zhu et al.’s (42) study. The issue that is remarkable about their study is that they prescribed baclofen as monotherapy without PPI. 52.2% of patients were treated with baclofen and 86.3% of baclofen non-responders were treated with double dose of PPI (42). On the other hand, Xu et al.’s (23) reported that adding baclofen to the PPI was effective in cough resolution of 66.7% of patients with GERC who failed to response high-dose PPI and H2blocker. On the whole, the heterogeneity of the studies in this category prevents us from making a correct judgment, and it seems that baclofen lacks the potency for standard clinical use in patients with GERC, apart from the fact that the risk of side effects is also higher in these patients due to the long-term use.

Does HH reduce the efficacy of baclofen during PPI add-on therapy? Beamount et al. (15) studied 27 GERD patients, including 16 patients without HH and 11 without a large HH. The total number of reflux episodes decreased by 36% in patients without HH and 43% in patients with HH, but the number of acid reflux episodes and total acid exposure time did not change. They reported that baclofen may also be effective in patients with a large HH but findings are not satisfactory (15).

Is baclofen effective as a stand-alone treatment for GERD? Twenty-two studies used baclofen as monotherapy and six used it as a combination therapy with PPI. Baclofen improved symptoms in both treatment groups significantly, but due to the heterogeneity of studies, it is impossible to compare these two groups. Despite the fact that baclofen monotherapy is effective in treating GERD, it is not recommended to use it as the first-line treatment without PPI; especially for long-term use, in which case its side effects are more pronounced. We recommend that, if high-dose PPI treatment fails to improve GERD, baclofen can be added to PPI to benefit the synergistic effects. In PPI-resistant patients, baclofen could be used as a replacement for prokinetics such as domperidone; particularly in patients who have heart diseases, as prokinetics prolong the QT interval and increase the risk of torsades de pointes and fatal arrhythmias (43).

Does body posture affect the efficacy of baclofen? Due to the strain of abdominal organs, the LES pressure is significantly higher in the supine position than the upright position and a low basal pressure of the LES is one of the important mechanisms of the GERD (44). Theoretically, baclofen, which increases the pressure of the LES, will be more effective in upright reflux; because of the lower LES pressure in this posture. Two studies evaluated the effect and reported that baclofen significantly decreased reflux episodes only in the upright position (15, 25). Thus, it seems that baclofen is not a good choice in patients with reflux in supine position (e.g., patients with nocturnal reflux). In contrast, Orr et al. (30) evaluated the efficacy of baclofen in reducing reflux during sleep (supine position). They reported that baclofen can not only significantly reduce reflux events during sleep, but also improve objective and subjective measures of sleep (30). So, it seems that the knowledge about the efficacy of baclofen in upright and supine positions are still paradoxical and more studies are needed to provide an answer.

Adding baclofen or suggesting anti-reflux surgery? After inadequate response from PPIs, the management of GERD is complex (45). Spechler et al. (46) compared the efficacy of medical treatment versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. 25 patients received baclofen plus omeprazole and 27 patients underwent nissen fundoplication surgery. The treatment success rate with surgery was significantly higher than medical treatment (67% against 28%, p-value = 0.007). Although the study evaluated heartburn (which is not specific for GERD, and also is not the only symptom of GERD), baclofen appears to be a less effective alternative for surgery candidates (46).

Baclofen may be more effective in some populations when other comorbidities of patients with GERD are considered. In addition to patients with muscle spasms, baclofen can be a priority in GERD patients with the following disorders:

Alcohol is one of the substances that can relax the LES and exacerbates reflux symptoms. Patients with symptomatic GERD are frequently advised to abstain from alcohol (47). Moreover, studies have shown that 30–80 mg of baclofen per day could be effective in quitting alcohol or preventing relapse: an off-label indication (48). In symptomatic GERD patients with AUD, baclofen not only reduces symptoms by decreasing TLESR episodes but also aids in alcohol cessation as a lifestyle modification.

Antacid medications (including histamine-2 blockers and PPIs) are the first-line treatment for GERD. However, in patients with non-acid reflux or rumination syndrome, the antacid approach does not relieve symptoms. In these patients, increasing LES pressure and minimizing TLESR episodes may be the best option (49, 50). Thus, if pH monitoring reveals non-acid reflux, baclofen could be the treatment of choice.

Studies have shown that central obesity is associated with symptomatic GERD. The mechanism is thought to be associated with increasing the gastroesophageal pressure gradient and shortening of the lower esophageal sphincter, which baclofen can resolve the latter. Moreover, obese patients are at higher risk of long-standing GERD complications, including erosive esophagitis, Barrett esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma (51). A pilot study shows the positive effects of baclofen on weight reduction in obese patients (52). Thus, in obese GERD patients, baclofen could reduce both the GERD symptoms and body weight, which is one of the risk factors for symptomatic GERD.

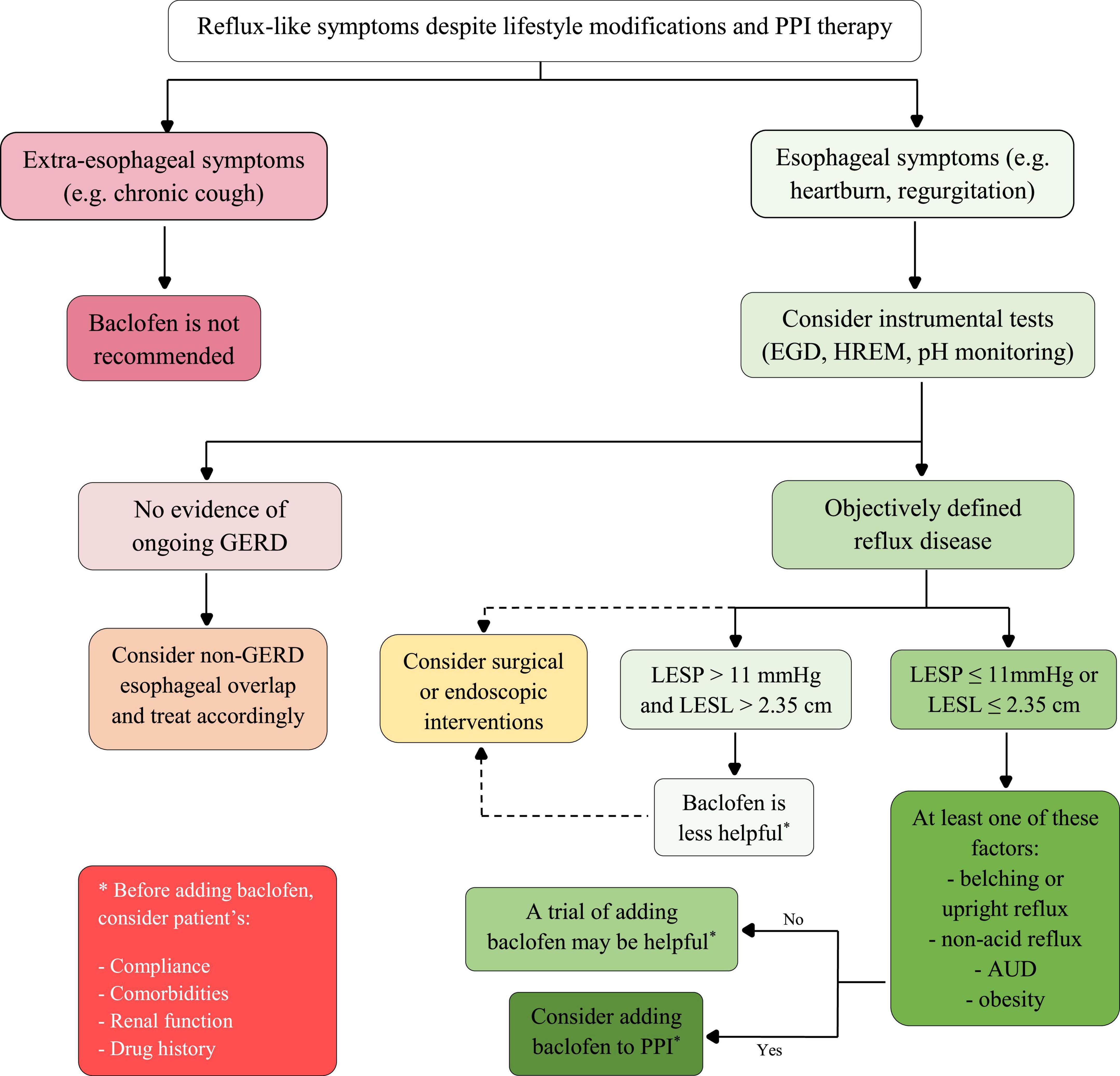

Management of refractory GERD can be very challenging. In PPI non-responders, the American College of Gastroenterology recommends against adding medications other than PPI to the regiment (53); Sometimes it is inevitably necessary to add other medications. Although trials confirm the efficacy of baclofen as a stand-alone treatment for GERD, we do not recommend it as a mono-therapy. In PPI-resistant patients, a trial of adding baclofen to the PPI may be helpful under special circumstances. This can help reduce symptoms (regurgitation, heartburn, and belching) and may decrease the dose of PPI. We recommend against using baclofen in patients with extra-esophageal reflux symptoms (e.g., GERC); as the efficacy of baclofen is low and the side effects are more frequent and severe. Also, we recommend against using baclofen for maintenance therapy or long-term use. In patients with symptomatic reflux who are candidates for anti-reflux surgery but refuse, baclofen can be a modest alternative. However, these patients may experience more side effects of baclofen as well. To reduce side effects, starting baclofen with a dose of 5–10 mg and incrementing to a maximum dose of 60 mg is recommended. Symptomatic GERD patients (especially those with belching or upright reflux) with an AUD, non-acid reflux, or obesity may benefit more from baclofen. An esophageal manometry (measures LES pressure and length) can help selecting refractory GERD patients who may respond appropriately to baclofen. Suggested algorithm for administration of baclofen for refractory reflux disease is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Suggested algorithm for administration of baclofen for refractory reflux disease. AUD, alcohol use disorder; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; HREM, high resolution esophageal manometry; LESL, lower esophageal sphincter length; LESP, lower esophageal sphincter pressure; PPI, proton pump inhibitor. *Means to pay attention to the issues that are listed in red rectangle.

Some limitations of this study should be taken into consideration. First, most of the studies diagnosed GERD (before and after intervention) by symptoms (not pH-monitoring) what is uncertain. Second, the relatively small number of trials in some outcome categories. This may diminish the persuasiveness of the conclusions. Third, the potential influence of the preexisting conditions and the severity of the reflux disease could not be investigated because of the limited information obtained from the reviewed articles. Fourth, as with any systematic review, limitations associated with potential publication bias should be considered. Furthermore, trials’ variability, different patients’ characteristics, and a wide range of outcome measures were other limitations.

The present study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first study that systematically addresses various aspects of baclofen administration in the spectrum of GERD patients. A trial of adding baclofen to the PPI may be helpful in PPI-resistant patients. Baclofen therapies may be more beneficial for symptomatic GERD patients who suffer AUD, non-acid reflux, or obesity. To reduce the side effects, we recommend starting baclofen with a low dose and increasing it gradually, avoiding prescribing more than 60 mg of baclofen per day, and paying close attention to the patients’ history.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

EA and MAbde designed the study. EA, SK, AA, and NT performed the search, study selection, and data extraction. EA and SK wrote the first draft of the manuscript. EA, MAbdi, DA, and MAbde revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2023.997440/full#supplementary-material

GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; GER, gastroesophageal reflux; GERC, gastroesophageal reflux-induced chronic cough; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; HH, hiatal hernia; LES, lower esophageal sphincter; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; TLESR, transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation.

1. Vakil N, Van Zanten S, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am Coll Gastroenterol. (2006) 101:1900–20.

2. Esposito C, Roberti A, Turrà F, Escolino M, Cerulo M, Settimi A, et al. Management of gastroesophageal reflux disease in pediatric patients: a literature review. Pediatric Health Med Ther. (2015) 6:1–8.

3. Lightdale J, Gremse D, Heitlinger L, Cabana M, Gilger M, Gugig R, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux: management guidance for the pediatrician. Pediatrics. (2013) 131:e1684–95.

4. Kamangar F, Nasrollahzadeh D, Safiri S, Sepanlou S, Fitzmaurice C, Ikuta K, et al. The global, regional, and national burden of oesophageal cancer and its attributable risk factors in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2020) 5:582–97. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30007-8

5. Katz P, Gerson L, Vela M. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. (2013) 108:308–28.

6. Gyawali C, Fass R. Management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. (2018) 154:302–18.

7. Zhang M, Hou Z, Huang Z, Chen X, Liu F. Dietary and lifestyle factors related to gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. (2021) 17:305–23. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S296680

8. Mikami D, Murayama K. Physiology and pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surg Clin. (2015) 95:515–25.

9. Tack J, Pandolfino J. Pathophysiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. (2018) 154:277–88.

10. Romito J, Turner E, Rosener J, Coldiron L, Udipi A, Nohrn L, et al. Baclofen therapeutics, toxicity, and withdrawal: a narrative review. SAGE Open Med. (2021) 9:20503121211022197. doi: 10.1177/20503121211022197

11. Zhang Q, Lehmann A, Rigda R, Dent J, Holloway R. Control of transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations and reflux by the GABA(B) agonist baclofen in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. (2002) 50:19–24. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.1.19

12. Li S, Shi S, Chen F, Lin J. The effects of baclofen for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gastroenterol Res Pract. (2014) 2014:307805. doi: 10.1155/2014/307805

13. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. (2009) 151:264–9.

14. NIH,. Study quality assessment tools. (2021). Available online at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

15. Beaumont H, Boeckxstaens G. Does the presence of a hiatal hernia affect the efficacy of the reflux inhibitor baclofen during add-on therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. (2009) 104:1764–71. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.247

16. Ciccaglione A, Marzio L. Effect of acute and chronic administration of the GABAB agonist baclofen on 24 hour pH metry and symptoms in control subjects and in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. (2003) 52:464–70. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.4.464

17. Dibner L. A pharmacological option for the treatment of GERD in infants effect of baclofen on esophagogastric motility and gastroesophageal reflux in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a randomized controlled trial. Rev Gastroenterol Méx. (2006) 71:544–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.05.029

18. Abbasinazari M, Panahi Y, Mortazavi S, Fahimi F, Valizadegan G, Mohtashami R, et al. Effect of a combination of omeprazole plus sustained release baclofen versus omeprazole alone on symptoms of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Iran J Pharm Res. (2014) 13:1221–6.

19. Bajbouj M, Becker V, Phillip V, Wilhelm D, Schmid R, Meining A. High-dose esomeprazole for treatment of symptomatic refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease -A prospective pH-metry/impedance-controlled study. Digestion. (2009) 80:112–8. doi: 10.1159/000221146

20. Koek G, Sifrim D, Lerut T, Janssens J, Tack J. Effect of the GABA(B) agonist baclofen in patients with symptoms and duodeno-gastro-oesophageal reflux refractory to proton pump inhibitors. Gut. (2003) 52:1397–402. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.10.1397

21. Sobhani Shahmirzadi M, Barati L, Ebraimi M, Shiroodbakhshi K. The efficacy of baclofen to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease in children aged 6 months to 12 years: a clinical trial study. Int J Pediatr. (2020) 8:11287–96.

22. Xu X, Lv H, Yu L, Chen Q, Liang S, Qiu Z. A stepwise protocol for the treatment of refractory gastroesophageal reflux-induced chronic cough. J Thorac Dis. (2016) 8:178–85. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2016.01.50

23. Xu X, Yang Z, Chen Q, Yu L, Liang S, Lv H, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of baclofen in refractory gastroesophageal reflux-induced chronic cough. World J Gastroenterol. (2013) 19:4386–92.

24. Kawai M, Kawahara H, Hirayama S, Yoshimura N, Ida S. Effect of baclofen on emesis and 24-hour esophageal pH in neurologically impaired children with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2004) 38:317–23. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200403000-00017

25. Cossentino M, Mann K, Armbruster S, Lake J, Maydonovitch C, Wong R. Randomised clinical trial: the effect of baclofen in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux–a randomised prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2012) 35:1036–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05068.x

26. Vakil N, Huff F, Bian A, Jones D, Stamler D. Arbaclofen placarbil in GERD: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. (2011) 106:1427–38. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.121

27. Vela M, Tutuian R, Katz P, Castell D. Baclofen decreases acid and non-acid post-prandial gastro-oesophageal reflux measured by combined multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2003) 17:243–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01394.x

28. Curcic J, Schwizer A, Kaufman E, Forras-Kaufman Z, Banerjee S, Pal A, et al. Effects of baclofen on the functional anatomy of the oesophago-gastric junction and proximal stomach in healthy volunteers and patients with GERD assessed by magnetic resonance imaging and high-resolution manometry: a randomised controlled double-blind study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2014) 40:1230–40. doi: 10.1111/apt.12956

29. Khodadad A, Sani M, Nemat-Khorasani E, Mansouri F. The effect of baclofen on treatment of infancy gastro-esophageal reflux disorder. Iran J Pediatr. (2008) 18(Suppl. 1):15–20.

30. Orr W, Goodrich S, Wright S, Shepherd K, Mellow M. The effect of baclofen on nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux and measures of sleep quality: a randomized, cross-over trial. Neurogastroenterol Motil. (2012) 24:553–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01900.x

31. Cange L, Johnsson E, Rydholm H, Lehmann A, Finizia C, Lundell L, et al. Baclofen-mediated gastro-oesophageal acid reflux control in patients with established reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2002) 16:869–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01250.x

32. Grossi L, Spezzaferro M, Sacco L, Marzio L. Effect of baclofen on oesophageal motility and transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations in GORD patients: a 48-h manometric study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. (2008) 20:760–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01115.x

33. Scarpellini E, Boecxstaens V, Broers C, Vos R, Pauwels A, Tack J. Effect of baclofen on gastric acid pocket in subjects with gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms. Dis Esophagus. (2016) 29:1054–63. doi: 10.1111/dote.12443

34. van Herwaarden M, Samsom M, Rydholm H, Smout A. The effect of baclofen on gastro-oesophageal reflux, lower oesophageal sphincter function and reflux symptoms in patients with reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2002) 16:1655–62.

35. Omari T, Benninga M, Sansom L, Butler R, Dent J, Davidson G. Effect of baclofen on esophagogastric motility and gastroesophageal reflux in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr. (2006) 149:468–74.

36. Abe T, Taniguchi W, Nishio N, Nakatsuka T, Yoshida M, Yamada H. Molecular mechanisms of the antispasticity effects of baclofen on spinal ventral horn neurons. Neuroreport. (2019) 30:19–25. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001155

37. Drake R, Davis L, Cates M, Jewell M, Ambrose S, Lowe J. Baclofen treatment for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann Pharmacother. (2003) 37:1177–81.

38. Clarke J, Fernandez-Becker N, Regalia K, Triadafilopoulos G. Baclofen and gastroesophageal reflux disease: seeing the forest through the trees. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. (2018) 9:137. doi: 10.1038/s41424-018-0010-y

39. Warren R, Davis S. The role of baclofen in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pharm Technol. (2015) 31:258–61.

40. Ertzgaard P, Campo C, Calabrese A. Efficacy and safety of oral baclofen in the management of spasticity: a rationale for intrathecal baclofen. J Rehabil Med. (2017) 49:193–203. doi: 10.2340/16501977-2211

42. Zhu Y, Xu X, Zhang M, Si F, Sun H, Yu L, et al. Pressure and length of the lower esophageal sphincter as predictive indicators of therapeutic efficacy of baclofen for refractory gastroesophageal reflux-induced chronic cough. Respir Med. (2021) 183:106439. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106439

43. Giudicessi J, Ackerman M, Camilleri M. Cardiovascular safety of prokinetic agents: a focus on drug-induced arrhythmias. Neurogastroenterol Motil. (2018) 30:e13302. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13302

44. Sears V, Castell J, Castell D. Comparison of effects of upright versus supine body position and liquid versus solid bolus on esophageal pressures in normal humans. Dig Dis Sci. (1990) 35:857–64. doi: 10.1007/BF01536799

45. Rettura F, Bronzini F, Campigotto M, Lambiase C, Pancetti A, Berti G, et al. Refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease: a management update. Front Med. (2021) 8:765061. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.765061

46. Spechler S, Hunter J, Jones K, Lee R, Smith B, Mashimo H, et al. Randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. N Engl J Med. (2019) 381:1513–23.

47. Pan J, Cen L, Chen W, Yu C, Li Y, Shen Z. Alcohol consumption and the risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alcohol Alcohol. (2019) 54:62–9.

48. De Beaurepaire R, Sinclair J, Heydtmann M, Addolorato G, Aubin H, Beraha E, et al. The use of baclofen as a treatment for alcohol use disorder: a clinical practice perspective. Front Psychiatry. (2019) 9:708. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00708

49. Pauwels A, Broers C, Van Houtte B, Rommel N, Vanuytsel T, Tack J. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study using baclofen in the treatment of rumination syndrome. Am Coll Gastroenterol. (2018) 113:97–104. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.441

50. Zikos T, Clarke J. Non-acid reflux: when it matters and approach to management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. (2020) 22:43. doi: 10.1007/s11894-020-00780-4

51. Hampel H, Abraham N, El-Serag H. Meta-analysis: obesity and the risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications. Ann Intern Med. (2005) 143:199–211.

52. Arima H, Oiso Y. Positive effect of baclofen on body weight reduction in obese subjects: a pilot study. Intern Med. (2010) 49:2043–7. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3918

53. Katz P, Dunbar K, Schnoll-Sussman F, Greer K, Yadlapati R, Spechler S. ACG clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. (2022) 117:27–56.

54. Gerson L, Huff F, Hila A, Hirota W, Reilley S, Agrawal A, et al. Arbaclofen placarbil decreases postprandial reflux in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. (2010) 105:1266–75. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.718

55. Vadlamudi N, Hitch M, Dimmitt R, Thame K. Baclofen for the treatment of pediatric GERD. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2013) 57:808–12.

56. Xu X, Chen Q, Liang S, Lü H, Qiu Z. Successful resolution of refractory chronic cough induced by gastroesophageal reflux with treatment of baclofen. Cough. (2012) 8:8.

57. Beaumont H, Smout A, Aanen M, Rydholm H, Lei A, Lehmann A, et al. The GABA(B) receptor agonist AZD9343 inhibits transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations and acid reflux in healthy volunteers: a phase I study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2009) 30:937–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04107.x

58. Boeckxstaens G, Rydholm H, Lei A, Adler J, Ruth M. Effect of lesogaberan, a novel GABA(B)-receptor agonist, on transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations in male subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2010) 31:1208–17.

59. Lidums I, Lehmann A, Checklin H, Dent J, Holloway R. Control of transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations and reflux by the GABA(B) agonist baclofen in normal subjects. Gastroenterology. (2000) 118:7–13. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70408-2

60. Blondeau K, Boecxstaens V, Rommel N, Farré R, Depeyper S, Holvoet L, et al. Baclofen improves symptoms and reduces postprandial flow events in patients with rumination and supragastric belching. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2012) 10:379–84. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.10.042

61. De Beaurepaire R, Joussaume B, Rapp A, Jaury P. Treatment of binge eating disorder with high-dose baclofen: a case series. J Clin Psychopharmacol. (2015) 35:357–9. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000332

62. Dong R, Xu X, Yu L, Ding H, Pan J, Yu Y, et al. Randomised clinical trial: gabapentin vs baclofen in the treatment of suspected refractory gastro-oesophageal reflux-induced chronic cough. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2019) 49:714–22. doi: 10.1111/apt.15169

63. Yu Y, Wen S, Wang S, Shi C, Ding H, Qiu Z, et al. Reflux characteristics in patients with gastroesophageal reflux-related chronic cough complicated by laryngopharyngeal reflux. Ann Transl Med. (2019) 7:529. doi: 10.21037/atm.2019.09.162

64. Blondeau K. Treatment of gastro-esophageal reflux disease: the new kids to block: VIEWPOINT. Neurogastroenterol Motil. (2010) 22:836–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01537.x

65. Xu X, Yu L, Chen Q, Shi C, Lv H, Qiu Z, et al. Association of esophageal dysfunction with therapeutic efficacy of baclofen in patients with refractory gastroesophageal reflux-induced chronic cough. Eur Respir Soc. (2017) 50:A3668.

66. Wu D, Huang Z, Chen S. Efficacy of baclofen combined with esomeprazole and mosapride on refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. Chin J Gastroenterol. (2014) 19:725–9.

Keywords: baclofen (PubChem CID: 2284), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), reflux, GABA agonist B, refractory, benign esophageal disease

Citation: Arabpour E, Khoshdel S, Akhgarzad A, Abdi M, Tabatabaie N, Alijanzadeh D and Abdehagh M (2023) Baclofen as a therapeutic option for gastroesophageal reflux disease: A systematic review of clinical trials. Front. Med. 10:997440. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.997440

Received: 18 July 2022; Accepted: 03 February 2023;

Published: 17 February 2023.

Edited by:

Huan Tong, Sichuan University, ChinaReviewed by:

Fernando A. M. Herbella, Federal University of São Paulo, BrazilCopyright © 2023 Arabpour, Khoshdel, Akhgarzad, Abdi, Tabatabaie, Alijanzadeh and Abdehagh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Erfan Arabpour,  ZXJmYW5hcmFicG91cjE5OTlAZ21haWwuY29t; orcid.org/0000-0003-0557-1278; Mohammad Abdehagh,

ZXJmYW5hcmFicG91cjE5OTlAZ21haWwuY29t; orcid.org/0000-0003-0557-1278; Mohammad Abdehagh,  YWFiYWF5QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; orcid.org/0000-0002-7177-1633

YWFiYWF5QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; orcid.org/0000-0002-7177-1633

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.