- Hu Nan Key Laboratory of Aging Biology, Department of Dermatology, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha, China

Nail lichen planus (NLP) is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology and has been recognized as a nail potentially critical disorder, which can be severe and rapidly worsen with irreversible scarring. Currently, the treatment options are limited based on disease progression. High-potency topical or intralesional corticosteroids are commonly considered first-line therapeutic options; however, these therapies are unsuitable for all patients with NLP, especially those with extensive lesions. As a potential therapeutic target for inflammatory skin diseases, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors can suppress both type-1 and type-2 cytokines, thereby reducing the immune response and resultant inflammation. Recent studies have suggested benefit in cutaneous lichen planus and lichen planopilaris with oral JAK inhibitors. Here, we report a case of severe NLP that exhibited a favorable response to tofacitinib treatment. A 41-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a 2-year history of nail dystrophy of all fingers of both hands. The NLP was finally confirmed by histopathology and the above clinical features. After the informed consent signature, tofacitinib monotherapy, 5 mg twice a day, was then begun, and after 6 months, the appearance of her nails had a significant improvement.

Introduction

Nail lichen planus (NLP) is a rare inflammatory nail disorder, which usually emerges in adulthood, and is characterized by predominant nail matrix destruction that can affect one or multiple nails/toenails (1). The management of NLP has always been challenging because of high rates of therapeutic failures and limited treatment options available, especially at the stage of dorsal pterygium (1).

As a potential therapeutic target for inflammatory skin diseases, Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors can suppress both type-1 and type-2 cytokines, thereby reducing the immune response and resultant inflammation (2). Here, we report a case of severe NLP that exhibited a favorable response to tofacitinib treatment.

Case presentation

A 41-year-old woman presented to our clinic with a 2-year history of nail dystrophy of all fingers of both hands. With seriously impacted qualities of life, she had a much more urgent demand for effective therapies. Onychomycosis was ruled out by direct microscopy and the history of failure of anti-fungal therapy. Physical examination demonstrated a series of typical NLP symptoms of longitudinal ridges and grooves, distal splitting, and trachyonychia, while nail bed and nail fold were generally normal (Figure 1). The patient was otherwise healthy and no other skin lesions were noted. Histological examination of nail biopsies showed band like lymphocytic infiltrate of nail matrix and focal liquefaction of the basal layer. Her NLP was finally confirmed by histopathology and the above clinical features.

The patient was initially treated with the topical application of high-potency corticosteroids and tacrolimus 0.1% ointment under occlusion using plastic film for 3 months, however, no significant improvement was seen. Due to the high number of nail involvement and painful side effects of the injection process, intralesional triamcinolone acetonide was not considered. We were also hesitant to initiate systemic treatment with oral retinoids or immunosuppressive agents, which is associated with increased risks and high treatment failure rates (3). Routine laboratory testing did not identify any abnormalities in our patient and screening for hepatitis B virus and latent tuberculosis infection was also negative. Tofacitinib monotherapy, 5 mg twice a day, was then begun, and after 6 months, the appearance of her nails had a significant improvement (Figure 2). During follow up, no treatment related adverse reactions were reported. As of this writing, the patient continues to receive tofacitinib and is doing well.

Figure 2. Clinical manifestation of nails of both hands after 6 months of treatment with tofacitinib, 5 mg twice a day.

Discussion

Nail lichen planus (NLP) is a chronic inflammatory disease with either isolated nail involvement or concurrently skin and mucosal involvement. It also has been recognized as a nail potentially critical disorder, which can be severe and rapidly worsen with irreversible scarring (4). High-potency topical or intralesional corticosteroids are commonly considered first-line therapeutic options; however, these therapies are not suitable for all patients with NLP, especially those with extensive lesions (5).

Although multifactorial in etiology, the mechanisms leading to lichen planus (LP) are not fully understood but likely involve a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental triggers, eventually leading to the auto-immune attack of the basal keratinocytes mediated by CD8+ CXCR3+ cytotoxic T cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (6). There is growing evidence showing that LP is a Th1-driven disease and mediates key cytokines in its pathogenesis through the JAK–STAT pathway (7). These finding suggest that tofacitinib might also have therapeutic benefits in NLP. Moreover, recent studies have suggested benefit in cutaneous lichen planus and lichen planopilaris with oral JAK inhibitors (7, 8). According to the above discussion, after clinical evaluation, treatment with tofacitinib was initiated with off-label use in this case.

Tofacitinib is a representative pan-JAK inhibitor and strongly blocks JAK1/3 but weakly inhibits JAK2 (9). It was first approved in 2012 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis and has since expanded the indications include psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and ulcerative colitis (9). However, as a non-selective first-generation JAK inhibitor, the clinical success of tofacitinib is limited by the increased adverse side effects associated with its broad inhibitory activity. In a study of seven-year safety databases based on the post-marketing surveillance data, a statistically significant elevation in the risk for pulmonary embolism and overall mortality were noted with the 10-mg dose of tofacitinib (10). Moreover, another randomized, noninferiority, safety end-point trial showed that the incidences of major adverse cardiovascular events and cancer were higher with the combined tofacitinib doses (3.4 and 4.2%, respectively) than with a TNF inhibitor (2.5 and 2.9%, respectively) (11). As a result, the FDA added a black-box warning and modified the labeling for all currently approved JAK inhibitors across all indications. It must be emphasized that all the above mentioned findings were based on patients with rheumatoid arthritis, which can only partially be generalized to patients with skin disorders. Identifying potential risk factors (include age>65, obesity, smoking, cardiovascular disease, coagulation disorder, or history of thromboembolism or malignancy) in an average individual may help in making tailored decisions in clinical practice (12).

The patient ultimately chose tofacitinib for the following reasons: (1) extensive nail damage with topical or intralesional corticosteroids is unsuitable because of the pain and inconvenience of that procedure, patient compliance is often poor; (2) systemic corticosteroids (0.5–1 mg/kg/d) are the most commonly used treatment options in clinical practice for severe LP, which may lead to a wide array of adverse events (3). Furthermore, based on our clinical experience, we found that females and elders were more vulnerable to the adverse effects of corticosteroids. The patient in our case refused glucocorticoid therapy because of obesity and menstrual disorders that might be caused by the inability to receive glucocorticoid therapy; (3) several reviews on the overall safety of JAK inhibitors have been published recently, suggesting that JAKi has good security with a low risk of venous thromboembolism, cardiac events, and cancer (13–17). As such, follow-up according to guidelines greatly ensured patient safety.

To date, there have been only two case reports about JAK inhibitors for the treatment of NLP (18, 19). In one case, an unexpected improvement in the nails was observed after the use of tofacitinib due to concomitant rheumatoid arthritis (19). Even more to the point, a successful pilot study indicated that tofacitinib yielded significant remission of nail lesions in patients with Synovitis-Acne-Pustulosis-Hyperostosis-Osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome (20). Given that permanent nail loss may occur without prompt and effective treatment, we propose that use of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib results in rapid resolution while avoiding the long-term side-effects of other topical treatments, such as corticosteroids. More studies are required to investigate the efficacy and remittive effect of tofacitinib for the treatment of NLP.

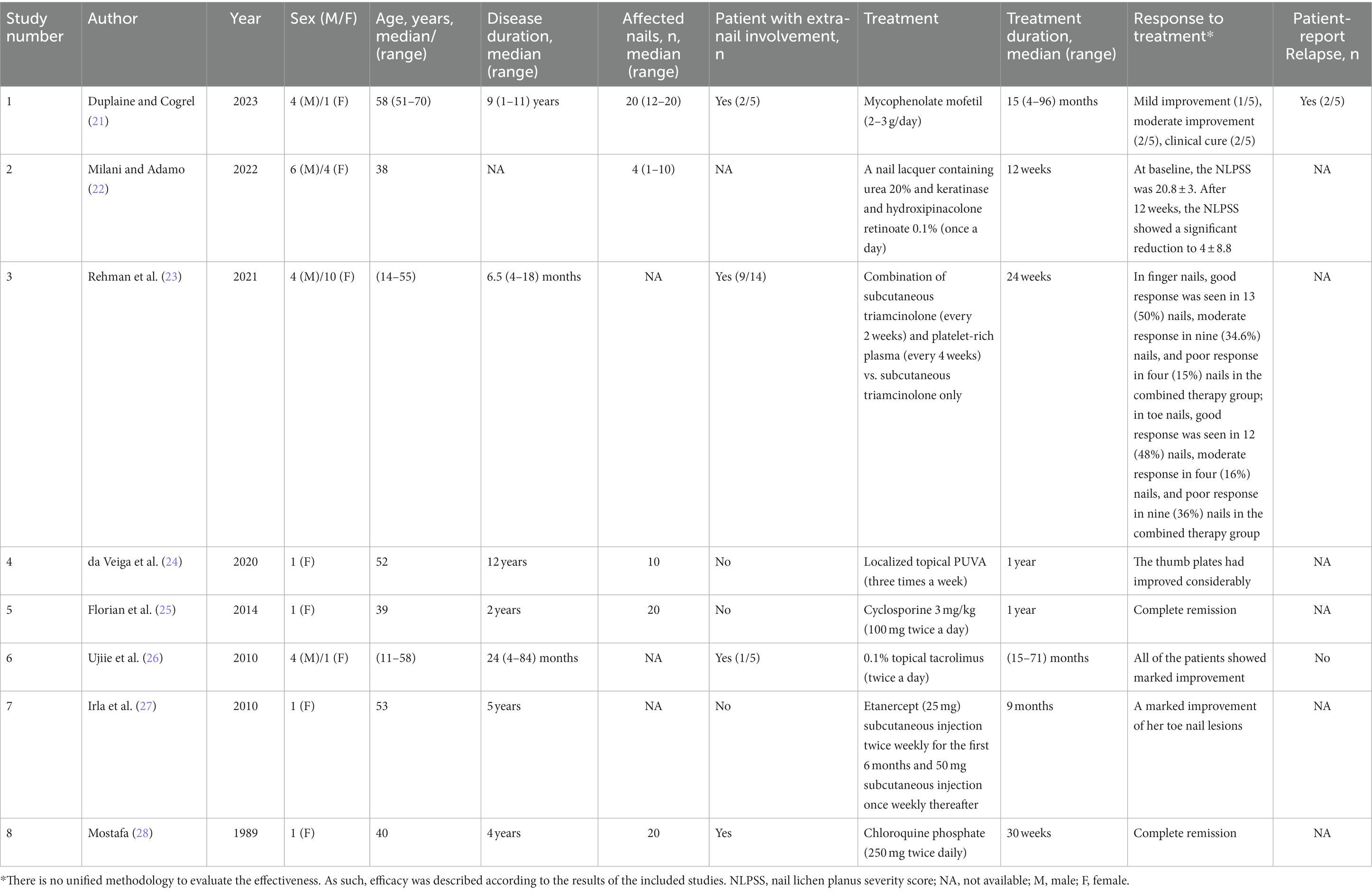

In order to fully describe the anecdotal reports of the successful treatment of nail lichen planus, a comprehensive literature search of PubMed was performed on October 29, 2023. Search terms included: “nail lichen planus,” “nail and lichen planus,” “treatment,” and “therapeutic.” In addition, articles including the wording “case report” or “case series” were added. All the sourced articles were full-text reviewed to ensure that the contents were relevant to the study. The literature search in PubMed yielded 155 articles. After the screening process, a total of 8 articles were labeled as eligible. Patient characteristics and treatment and response data are shown in Table 1. In summary, few cases of successful treatment of NLP have been reported. Low-quality research may lead to poor information for evidence-based decision-making.

In conclusion, NLP is a chronic inflammatory disorder with significant cosmetic and functional impact. The treatment options are limited based on disease progression. This case highlights the potential of the tofacitinib to improve this condition, and improve patient quality of life. More studies and observations are needed to fully appreciate the potential of tofacitinib for NLP.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WS: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

All authors thank the patient in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Grover, C, Kharghoria, G, and Baran, R. Nail lichen planus: a review of clinical presentation, diagnosis and therapy. Ann Dermatol Venereol. (2022) 149:150–64. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2022.01.010

2. Ciechanowicz, P, Rakowska, A, Sikora, M, and Rudnicka, L. JAK-inhibitors in dermatology: current evidence and future applications. J Dermatolog Treat. (2019) 30:648–58. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2018.1546043

3. Rice, JB, White, AG, Scarpati, LM, Wan, G, and Nelson, WW. Long-term systemic corticosteroid exposure: a systematic literature review. Clin Ther. (2017) 39:2216–29. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.09.011

4. Gupta, MK, and Lipner, SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. (2021) 39:221–30. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002

5. Iorizzo, M, Tosti, A, Starace, M, Baran, R, Daniel, CR III, di Chiacchio, N, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2020) 83:1717–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

6. Tziotzios, C, Lee, J, Brier, T, Saito, R, Hsu, C-K, Bhargava, K, et al. Lichen planus and lichenoid dermatoses: clinical overview and molecular basis. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2018) 79:789–804. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.010

7. Motamed-Sanaye, A, Khazaee, YF, Shokrgozar, M, Alishahi, M, Ahramiyanpour, N, and Amani, M. JAK inhibitors in lichen planus: a review of pathogenesis and treatments. J Dermatolog Treat. (2022) 33:3098–103. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2022.2116926

8. Plante, J, Eason, C, Snyder, A, and Elston, D. Tofacitinib in the treatment of lichen planopilaris: a retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2020) 83:1487–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.104

9. Kostovic, K, Gulin, SJ, Mokos, ZB, and Ceovic, R. Tofacitinib, an Oral Janus kinase inhibitor: perspectives in dermatology. Curr Med Chem. (2017) 24:1158–67. doi: 10.2174/1874467210666170113104503

10. Winthrop, KL, and Cohen, SB. Oral surveillance and JAK inhibitor safety: the theory of relativity. Nat Rev Rheumatol. (2022) 18:301–4. doi: 10.1038/s41584-022-00767-7

11. Ytterberg, SR, Bhatt, DL, Mikuls, TR, Koch, GG, Fleischmann, R, Rivas, JL, et al. Cardiovascular and Cancer risk with Tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. (2022) 386:316–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109927

12. Samuel, C, Cornman, H, Kambala, A, and Kwatra, SG. A review on the safety of using JAK inhibitors in dermatology: clinical and laboratory monitoring. Dermatol Ther. (2023) 13:729–49. doi: 10.1007/s13555-023-00892-5

13. Klein, B, Treudler, R, and Simon, JC. JAK-inhibitors in dermatology - small molecules, big impact? Overview of the mechanism of action, previous study results and potential adverse effects. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. (2022) 20:19–25. doi: 10.1111/ddg.14668_g

14. Elmariah, SB, Smith, JS, and Merola, JF. JAK in the [black] box: a dermatology perspective on systemic JAK inhibitor safety. Am J Clin Dermatol. (2022) 23:427–31. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00701-3

15. Yoon, S, Kim, K, Shin, K, Kim, HS, Kim, B, Kim, MB, et al. The safety of systemic Janus kinase inhibitors in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2023) 1–10. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19426

16. Liu, M, Gao, Y, Yuan, Y, Yang, K, Shen, C, Wang, J, et al. Janus kinase inhibitors for alopecia Areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. (2023) 6:e2320351. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.20351

17. Mao, MQ, Ding, YX, Jing, J, Tang, ZW, Miao, YJ, Yang, XS, et al. The evaluation of JAK inhibitors on effect and safety in alopecia areata: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 2018 patients. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1195858. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1195858

18. Punchera, J, and Laffitte, E. Treatment of severe nail lichen planus with Baricitinib. JAMA Dermatol. (2022) 158:107–8. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5082

19. Iorizzo, M, and Haneke, E. Tofacitinib as treatment for nail lichen planus associated with alopecia Universalis. JAMA Dermatol. (2021) 157:352–3. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.4555

20. Li, C, Li, Z, Cao, Y, Li, L, Li, F, Li, Y, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of nail lesions and palmoplantar Pustulosis in synovitis, acne, Pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. (2021) 157:74–8. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.3095

21. Duplaine, A, and Cogrel, O. Mycophenolate Mofetil in the treatment of severe corticosteroid-dependent or corticosteroid-resistant nail lichen planus: a case series of 5 patients. Skin Appendage Disord. (2022) 8:427–30. doi: 10.1159/000524246

22. Milani, M, and Adamo, L. Successful treatment of nail lichen planus with a lacquer containing urea, keratinase, and a retinoid molecule: report of 10 cases. Case Rep Dermatol. (2022) 14:43–8. doi: 10.1159/000523796

23. Rehman, F, Krishan, K, Latif, I, Sudan, E, Sultan, J, and Hassan, I. Intra-individual right-left comparative study of combined therapy of Intramatricial triamcinolone and platelet-Rich plasma vs. Intramatricial triamcinolone only in lichen planus-associated nail dystrophy. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. (2021) 14:311–7. doi: 10.4103/JCAS.JCAS_156_20

24. da Veiga, GP, Perez-Feal, P, Moreiras-Arias, N, Peteiro-García, C, Suárez-Peñaranda, JM, Vázquez-Veiga, H, et al. Treatment of nail lichen planus with localized bath-PUVA. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. (2020) 36:241–3. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12528

25. Florian, B, Angelika, J, and Ernst, SR. Successful treatment of palmoplantar nail lichen planus with cyclosporine. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. (2014) 12:724–5. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12325

26. Ujiie, H, Shibaki, A, Akiyama, M, and Shimizu, H. Successful treatment of nail lichen planus with topical tacrolimus. Acta Derm Venereol. (2010) 90:218–9. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0814

27. Irla, N, Schneiter, T, Haneke, E, and Yawalkar, N. Nail lichen planus: successful treatment with Etanercept. Case Rep Dermatol. (2010) 2:173–6. doi: 10.1159/000321419

Keywords: nail lichen planus, tofacitinib, case report, review, JAK inhibitor

Citation: Huang J and Shi W (2023) Successful treatment of nail lichen planus with tofacitinib: a case report and review of the literature. Front. Med. 10:1301123. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1301123

Edited by:

Müzeyyen Gönül, Dışkapı Yildirim Training and Research Hospital, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Albert E. Zhou, UCONN Health, United StatesDario Didona, University Hospital Giessen and Marburg, Germany

Archana Singal, University College of Medical Sciences, India

Mohammed Abu El-Hamd, Sohag University, Egypt

Copyright © 2023 Huang and Shi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Shi, c2hpd2VpQGNzdS5lZHUuY24=

Jundong Huang

Jundong Huang Wei Shi

Wei Shi