- 1Department of Neurology, School of Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States

- 2School of Music, The University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, United States

- 3School of Music, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States

- 4Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC), Veterans Affairs Minneapolis Healthcare System, Minneapolis, MN, United States

Introduction: Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) constitutes a major societal problem with devastating neuropsychiatric involvement in over 90% of those diagnosed. The large spectrum of AD neuropsychiatric symptoms leads to polypharmacological prescribing that, in turn, poses a major risk for increased side effects. Non-pharmacological interventions such as music therapy (MT) are therefore recommended as first-line treatments. The amalgamation of an aging population, long lifespan, and shortage of qualified music therapists limits access to MT services for AD.

Objective: The purpose of this paper is to provide a rationale for a protocolized music teletherapy (MTT) intervention to increase accessibility for MT as a psychosocial intervention for neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with AD by conducting a narrative review of the existing MT and AD literature.

Methods: We conducted a narrative review of MT and MTT publications indexed in PubMed and Google Scholar wherein authors used the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. We examined the impact of MT on neuropsychiatric symptoms of AD and identified MTT as a way to increase access to clinical services.

Results: MT can have positive impacts on neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD. However, we identified an ensuing need for protocolized MT interventions, access to services, and increased awareness. MTT is an option that can address these needs.

Discussion: Although MT can have positive effects on neuropsychiatric symptoms and can be beneficial and safe for individuals with AD, the current approach to MT practice is enormously heterogeneous with studies demonstrating variable therapist qualifications, uses of music, therapy approaches, and clinical populations. Congruently, the existing literature indicates that MT has not been standardized with protocolized interventions, making it difficult for clinicians and researchers to objectively assess the evidence, and thus, prescribe MT interventions. The lack of MT standardization, coupled with a low number of music therapists relative to people with AD, result in a lack of awareness that hinders access to MT as a psychosocial treatment for neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with AD. We therefore propose that protocolized MTT interventions are needed to increase access to better address neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with AD.

Introduction

The Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) population in the United States is currently at 6.5 million and is predicted to reach over 12.5 million by 2050 (1). As such, AD constitutes a major societal problem warranting treatment, funding, and research. AD is accompanied by neuropsychiatric symptoms in over 85% of those diagnosed (2–5). These symptoms can be disruptive, impair care, and result in unsafe conditions for people with AD (6). Neuropsychiatric changes including irritability, agitation, anxiety, and depression are common in patients in the earlier stages of AD (2). In later AD stages, symptoms can include aggression, anger, restlessness, delusions, hallucinations, sleep disturbances, and sundowning. Additionally, environmental factors including but not limited to noise, heat, and social interactions, can activate and augment these symptoms (7, 8). These neuropsychiatric changes decrease quality of life and increase caregiver burden, often leading to institutionalization (9, 10). The ability to successfully address these neuropsychiatric symptoms has the potential to prolong independent living at home, delay institutionalization and may reduce caregiver burden, and reduce expenses.

Pharmacological approaches to neuropsychiatric symptoms of AD

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had not approved pharmacological interventions for treatment of AD neuropsychiatric symptoms until the recent approval of brexipiprazole (Rexulti) (11). The vast majority of pharmacological treatments for AD neuropsychiatric symptoms are prescribed off-label. Most commonly, physicians prescribe atypical antipsychotic medications to address psychosis in AD, but these have black-box warnings, potentially making them unsafe (12, 13). Although brexipiprazole was approved for the treatment of agitation associated with AD, it carries a black-box warning for increased mortality in elderly individuals with dementia-related psychosis as well as increased risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in young adults (11). Additionally, off-label prescribed medications often have side effects that may be difficult to tolerate in elderly populations with comorbidities such as cerebrovascular conditions and Parkinson’s disease. Common psychotropic medications including olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone are typically discontinued within 3 months because of lack of tolerability or associated cerebrovascular events and extrapyramidal symptoms (14). Moreover, because of the large spectrum of neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD, treatments to address depression, agitation, psychosis, or sleep disturbances often lead to polypharmacological prescribing and pose an increased risk for side effects. Thus, non-pharmacological treatments, including music-based interventions, can constitute first-line psychosocial treatments that may maintain neuropsychiatric regulation without the risk of side effects (2, 15).

Music to address AD neuropsychiatric symptoms

Researchers have provided a neurological rationale for music as a psychosocial intervention for AD. For example, Ferreri et al. conducted a double masked within-subject design in healthy participants engaged in music listening and showed a positive association between dopamine and the music experience. The participants received a dopamine precursor (levodopa), a dopamine antagonist (risperidone), or a placebo (lactose) (16). The authors found that the dopamine precursor levodopa enhanced the hedonic and motivational experience associated with music, whereas the dopamine antagonist diminished the effect. In a separate study, Wang et al. evaluated fMRI resting-state data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) to study functional connectivity within and between auditory and rewards systems in older adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), AD, and age-matched healthy controls (17). Wang et al. found preserved within- and between-network connectivity in the auditory and reward systems in MCI individuals compared to AD, suggesting that functional connectivity is impaired as AD pathology progresses.

Scholars conducting preliminary studies in music and AD have indicated that music ability and memory are housed in an “island of preservation” in people with dementia (18). Memory for familiar music can be somewhat maintained in AD (19–23). The ability to respond, recall, or produce music by singing, playing instruments, or composing is often preserved even in the severe stages of AD (24, 25). When 7 Tesla functional brain magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) compared AD regions of interest to the brain’s response to music excerpts, regions such as the anterior cingulate cortex and ventral pre-supplementary motor area which encoded musical memory corresponded to areas, showed substantially minimal cortical atrophy and minimal disruption of glucose-metabolism (26). The unique relationship between music and preserved memory suggests music-based interventions, including music therapy (MT), may constitute an approach to address neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD.

Introduction to music therapy

MT is a specific music-based intervention wherein qualified music therapists (MT-BCs1) use music to address clinical objectives within the context of a therapeutic relationship. MT is based on the interactions between the service user,2 a compassionate and empathetic MT-BC, and the music. Capitalizing on the associations between music, neuroscience, and the interpersonal relationship between the service user and therapist, MT can be an engaging psychosocial treatment for people with AD. In the United States, MT-BCs undergo academic training and accrue 1,200 supervised clinical training hours prior to the board-certification exam. Resulting from their “rigorous” (27) academic and clinical training, MT-BCs are uniquely qualified to design and implement effective psychosocial interventions for people with AD to address their diverse needs. MT-BCs are educated in and guided by psychotherapeutic frameworks that are developmentally and clinically appropriate given the service user, objectives, and context. MT-BCs are knowledgeable and skilled in a plethora of music genres and styles, various instruments and voice, and the psychology of music (28, 29). With this unique knowledge and skill set, MT-BCs implement research-based interventions to maximize therapeutic outcomes.

After receiving a referral from a healthcare professional, the MT-BC conducts a formal assessment as part of the treatment process to design and tailor interventions that best use the person’s strengths and motivations to address their needs. MT interventions are based on the service user’s assessment, music preferences, experiences, and motivations for therapy and therefore minimize the potential for music-induced harm (30). Tailored MT interventions can vary depending on factors related to the service user’s preferences and experiences, the MT-BC, and music all within the unique contextual parameters of the setting and related clinical objectives. As such, MT interventions typically vary across different service user populations, clinical objectives, as well as the education, clinical experiences, and approaches of the MT-BC.

Regarding the music within MT, there are often misperceptions that certain music genres are beneficial as well as that there are music genres more likely to result in detrimental impacts on people’s health (31–36). However, each individual’s preferred music is the most effective and therapeutic regardless of the genre or message within the music (37, 38). Resultant of its malleability and the MT-BC’s musical skill sets, live music can be more effective and therapeutic than recorded music (39, 40). Therefore, MT-BCs are academically and clinically trained to be knowledgeable in a wide variety of music genres and are competent musicians on instruments including voice, piano, guitar, and percussion. The use of preferred live music during interactive MT can also result in a stronger therapeutic relationship, alliance, and therapeutic outcome (30, 41).

MT is distinct from receptive music listening and music medicine3 as MT-BCs address non-musical clinical objectives that have been collaboratively formulated by the service user, MT-BC, and the multidisciplinary treatment team. MT-BCs integrate service user’s preferred music and present it in a developmentally appropriate manner. Moreover, MT-BCs use live music with optimized levels of repetition to enhance engagement and clinical success and are able to manipulate a variety of musical elements including melody, harmony, tempo, dynamics, timbre, and structure. Common MT interventions for people with AD may include singing, playing instruments, composition, reminiscing, and receptive music listening. MT-BCs are trained to use nonverbal behavior with older adults and those with AD to enhance clinical outcomes (42, 43). The gestalt of these music and common therapy factors based on traditional talk-based interventions can result in augmented service user engagement, motivation, and positive treatment outcomes (38, 42, 44, 45).

Further supporting MT for AD, music is processed in bilateral cerebral hemispheres and is considered to be different from noise. Stegemöller et al. (2018) proposed that professionally trained musicians such as MT-BCs have less noise in their speech and singing (46). As a result, Stegemöller et al. (2018) suggested that MT can augment neuroplasticity because the brain is more efficient at processing a clear auditory signal (46). Additionally, the Neuroplasticity Model of Music Therapy (NMMT) describes how MT can augment neuroplasticity via utilizing the service user’s preferred music (46, 47). The NMMT and Hebbian principle note that pairing novel information and behaviors with rhythm can synchronize neural activation and augment the likelihood of neuroplasticity, particularly seen when MT-BCs are able to successfully manipulate various elements of live music by activating various brain regions (46). As such, music and MT may be an effective way to engage people with AD and thus offer potential therapeutic effects for the neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with AD.

To date, the existing MT literature for AD is positive but limited in its scope related to neuropsychiatric symptoms. Moreover, there is a paucity of literature regarding music teletherapy (MTT) research outcomes. This gap in the literature is consequential because MTT may be able to increase access to MT as a psychosocial intervention to address neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to provide a rationale for a protocolized music teletherapy (MTT) intervention to address neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD by conducting a narrative review of the existing MT and AD literature.

Method

Narrative review

To provide a rationale for a protocolized MTT intervention to increase accessibility for MT as a psychosocial intervention for neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with AD, we conducted a focused search via PubMed and Google Scholar. Inclusion criteria consisted of refereed AD articles published in English using the neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI) (48) as a dependent variable. The NPI is a frequently used quantitative measurement for neuropsychiatric symptoms available in over 40 different languages and has been used in 350 clinical trials. The NPI examines many of the neuropsychiatric changes that develop in AD including delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, depression, anxiety, elation/euphoria, apathy/indifference, disinhibition, irritability, aberrant motor behavior, sleep and night time behavior disorders, appetite and eating disorders (48–50). Tailoring our review to the NPI allowed us to compare the studies in a more standardized manner. We included AD but excluded other forms of dementia. We recognize these criteria as delimitations of the paper.

Results and rationale for music teletherapy

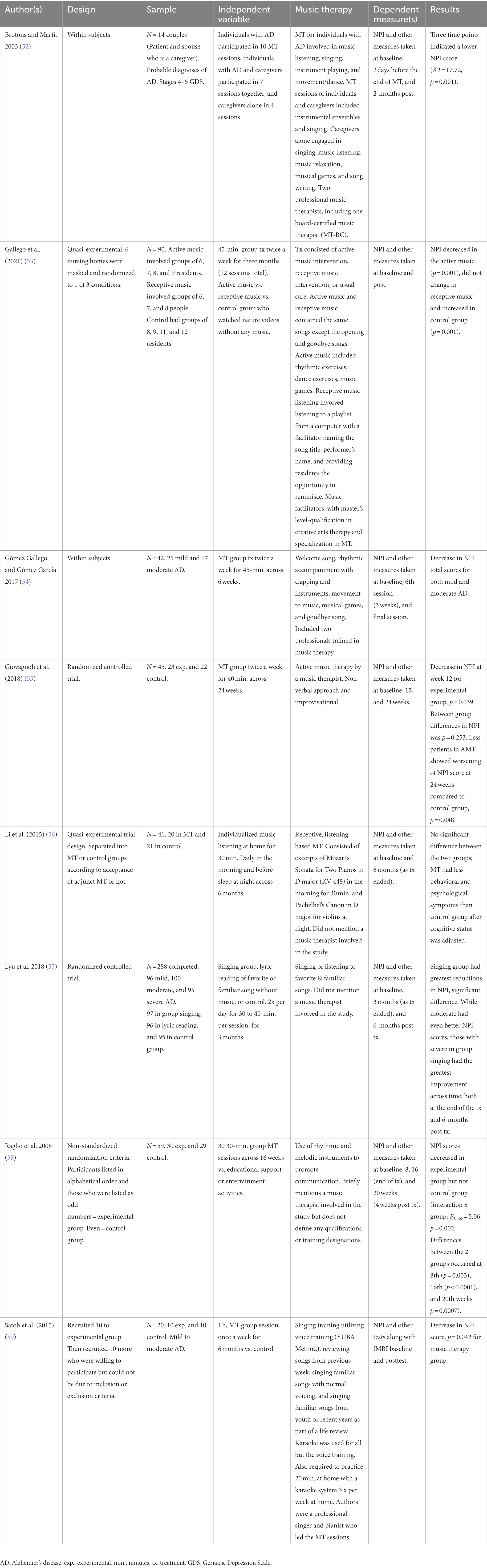

MT is considered beneficial and safe by people with AD and their caregivers (51). We identified eight existing clinical trials that met our inclusion criteria of MT services to treat neuropsychiatric symptoms of individuals with AD. We extracted relevant data from these studies and depicted the results in Table 1. As seen in Table 1, most researchers investigating MT found significant improvement on neuropsychiatric symptoms of AD. However, there are limitations in these studies. The researchers conducting these trials did not use a single standardized MT protocol and the approaches towards how MT was conducted varied widely.

Lack of standardized music therapy protocols

Although MT can be beneficial as well as safe for people with AD and their caregivers, current MT practice is heterogeneous with variable therapist qualifications and therapeutic approaches (51, 60–62). For example, although there are 99 MT training programs in Europe, the European MT confederation reports that standardization of training standards have not yet been completed (63). MT interventions can also vary between recorded music versus live music. Additionally, there can be differences in active interventions including instrument playing, composition, music making, singing, listening, and reminiscing. The totality of the vast number of musical elements to consider, MT intervention types, and sociocultural aspects of music further compound the heterogeneity of MT. Moreover, MT researchers have not consistently protocolized intervention approaches, making it difficult to objectively assess the state of the literature.

The protocolization of MT may help to standardize it as a nonpharmacological AD treatment option, improve dissemination, and incorporate it into standard of care for AD. To develop effective protocols that will lead to referrals and increase access to care, it will be crucial to develop systematic and reproducible measures to identify mechanisms of change including but not limited to dosage, duration, procedures, and MT intervention components that predict clinically significant improvement in AD neuropsychiatric outcomes. To date, researchers have not empirically identified therapeutic process factors that contribute to MT outcomes in AD. Thus, it is imperative to identify critical MT process elements to enable future treatment refinement and to train MT-BCs to reproduce high-quality MT, both of which ultimately may improve patient outcomes. In addition, researchers will need to report these mechanisms and components in a transparent manner such that standardized reproducible protocols are developed and accepted as standard of care. As such, we recommend using reporting guidelines for music-based interventions (64) and clearly articulating the qualifications, approach, and experiences of the practitioner providing MT. Protocolized music teletherapy (MTT) intervention has the potential to overcome some of the barriers associated with MT and increase accessibility such that MT becomes a realistic and viable psychosocial intervention option for neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with AD.

Music therapy access

There are approximately 10,000 MT-BCs in the United States. However, as MT is a medium-specific profession and MT-BCs serve a variety of clinical populations, not all MT-BCs work in AD settings. Within the United States, the AD population is currently at 6.5 million and predicted to reach over 12.5 million by 2050 (65, 66). Given these statistics, it is unlikely that there will be enough MT-BCs to meet the psychosocial needs of people with AD.

In addition to a limited number of MT-BCs and a growing population of people with AD, 50% of people with AD stop driving within 3 years of disease onset (67). Thus, challenges in transportation logistics in AD can further limit MT access. The amalgamation of these factors severely restricts the ability of MT-BCs to provide in-person MT.

We therefore recommend MTT as an option to increase access to services by eliminating the need for patients to drive to sessions. With MT-BCs providing care remotely, it would also eliminate time allocated to driving. The reduction in driving may lead to the ability to provide additional services. By eliminating travel times, MT-BCs may also increase their billable hours and increase their earning potential. Increased revenue may lead to fewer MT-BCs leaving the profession (68–70).

Music therapy awareness

To date, there is limited research regarding MT for neuropsychiatric symptoms related to AD. This lack of research based on standardized protocols likely impacts the awareness of MT as a potential treatment for AD. Moreover, care providers are often not aware of MT as a psychosocial intervention for AD because of poor access to MT in the outpatient setting, and therefore do not make referrals (71). Additionally, it is possible caregivers are unaware of MT as a treatment for AD and therefore are not likely to request it as a treatment option for their loved ones. Reasons that caregivers are unaware of MT as a treatment in the USA may be because the United States’ Alzheimer’s Association website does not offer MT as a treatment option (72).Whilst the National Institute of Aging recommends music and singing to patients with AD, the NIA does not specifically recommend MT as a treatment for neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD (73). As a result of the combination of these factors, patients and caregivers can experience difficulty in obtaining MT services.

Rationale for protocolized music tele-therapy

To date, there is no published clinical trial study investigating MTT for neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD. However, authors have noted that non-MT telehealth interventions can be delivered for people with MCI and AD and that these treatments can be as effective as in-person delivery (74–77). MT scholars reported that MT can be delivered to older adults via telehealth (78, 79). Although MTT was already in existence (80, 81), it was popularized out of necessity during the COVID-19 pandemic (82). Various MT authors have described MTT as a potential service delivery model (78, 79). Telehealth can reduce caregiver burden, reduce access barriers, and reach a wide range of patients in rural areas or locations with low numbers of music therapists (83). Furthermore, MTT augments accessibility and reduces travel time for both the therapist and service users. Music therapists are likely to continue using telehealth in the future and believe that caregiver involvement is important (78).

Given the interactive and music-related aspects of MT, there are potential complications with MTT including but not limited to compromised quality of the music, delays when interacting or when concurrently engaging in live music, reliable internet connections, and secure and accessible platforms. These complications may be exacerbated in AD populations who may have difficulty learning new skills such as accessing MTT on a phone, tablet, or computer. However, advances in technology have made it easier for individuals to use smartphones and tablets for therapeutic purposes (84, 85). We suggest providing service users with high quality instruments, technology that relies on cellular data instead of home-based wifi, and using both live and recorded music and more talk-based therapy approaches in MTT. As approximately 50% of surveyed music therapists reported that they would continue telehealth delivery after the pandemic restrictions are over (79), MTT is a viable delivery format for MT.

During the pandemic, researchers stated there was a need to determine how people with AD and their caregivers benefit from MT services delivered via telehealth and the role of the caregiver in the process (78). Currently, there is no music therapy study comparing an in-person delivery format with MMT; however, other non-MT telehealth psychosocial interventions for older adults with dementia and their caregivers can be as effective as in-person delivery (75–77). Based on these results, MTT may have potential to be as effective as in-person service delivery formats. Relatedly, Saragih et al. suggested future researchers conduct trials to determine what factors are associated with positive outcomes in telehealth interventions for people with dementia and their caregivers as there is a need to provide evidence for what might be effective with older adults with dementia as well as the mechanisms of action. Based on our review, we suggest this is also the case for MT and MTT.

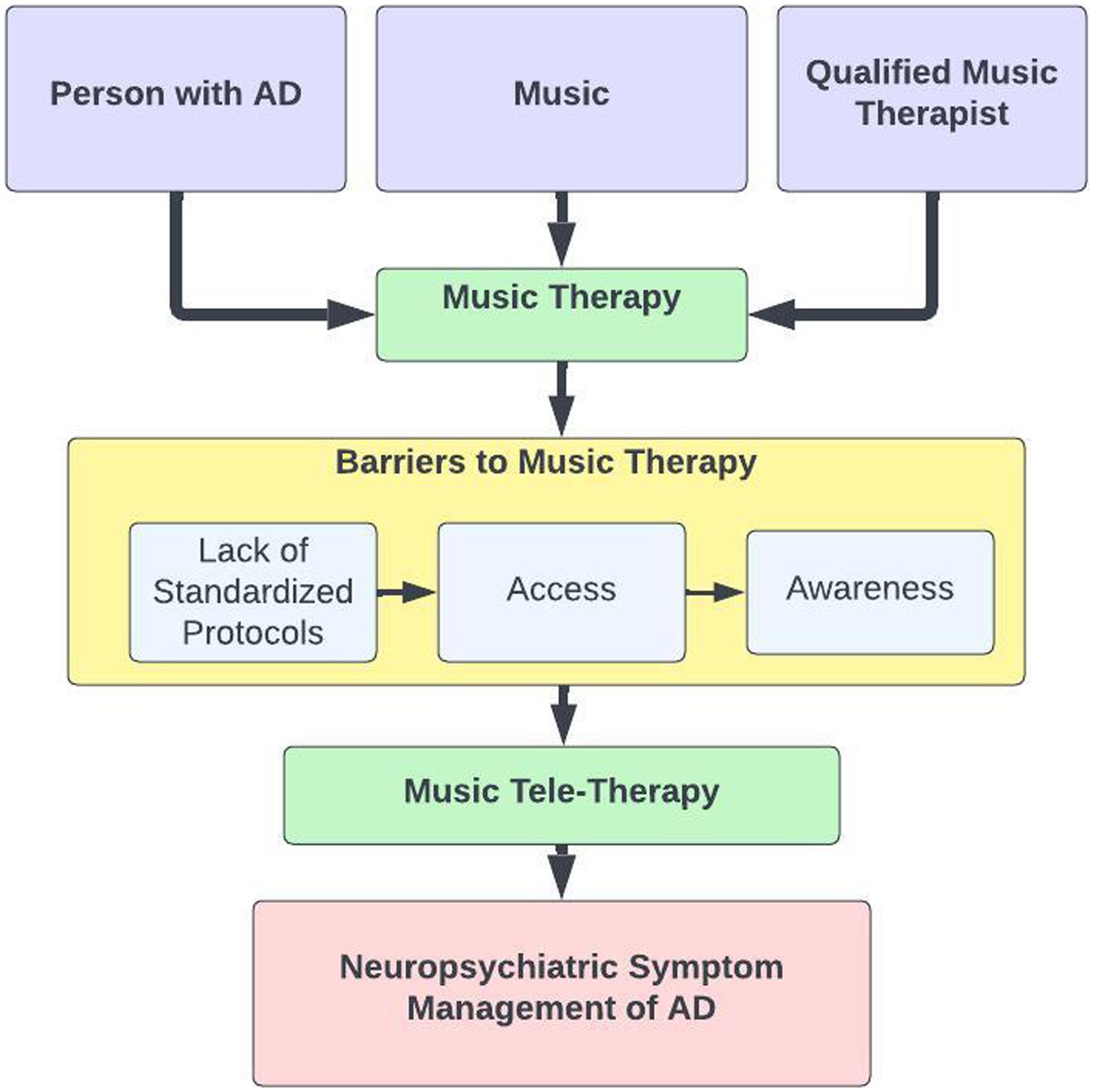

Our narrative review regarding MTT to increase accessibility for MT as a psychosocial intervention for neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD implicates three main categories representing barriers to MT for AD utilization and delivery: (1) lack of standardization in MT protocols, (2) lack of access to music therapy, and (3) lack of awareness. Based on the interactions between these identified factors, we created Figure 1 to depict a rationale for MTT to address neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD.

Figure 1. Barriers to MT for AD utilization and delivery. A flow diagram depicts the barriers to music therapy and music tele-therapy as a solution in the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of AD.

The barriers to accessing music therapy are problematic, especially since music might be a viable non-pharmacological approach to address the neuropsychiatric symptoms for adults with AD. We therefore propose music therapists utilize MTT to increase the number of people served, particularly those with AD and their caregivers, who often have limitations in accessing treatment. As a person-centered and flexible treatment, both MT and MTT have the potential to address the neuropsychiatric symptoms that are problematic for people with AD and their caregivers. However, MTT has the potential to improve access to care.

Limitations

There are numerous limitations of this review. First, our inclusion criteria were purposely narrow as we wanted to specifically investigate the impact of MT on neuropsychiatric symptoms as measured by the NPI in AD. There were other articles wherein authors investigated music and MT for individuals with dementia or addressed different dependent measures (86–90). Although using the NPI as inclusion criteria allowed us to compare and contrast studies with a validated quantitative outcome measure, it also limited our results to eight studies. Only including articles published in English is also a limitation and we note the privilege associated with our familiarity of the English language. A final and consequential limitation is that not all countries have established MT training programs or qualified MT practitioners.

Suggestions for future research

Based on the narrative review, there is a need for studies to improve the understanding of the underlying mechanisms of MT via imaging and biomarkers. To date, the underlying mechanisms of action within MT for AD are poorly understood and a better comprehension of these mechanisms may lead to the ability to design best practice MT interventions that may include neuromodulation or pharmaceuticals to augment MT’s clinical effects. MT may have the potential to raise people’s thresholds for tolerating environmental stimuli that activate unmet needs in AD (91). Therefore, future investigators could design and measure the impact of MT interventions and structured MT environments to address unmet needs by adjusting the sensory input and maximizing skills and abilities of each individual throughout the session (44). Future research using broader inclusion criteria may identify limitations and help develop a research agenda. Additionally, researchers could study process elements within MT to identify what components of MT are most clinically significant such that these processes are incorporated into standardized protocols. These may include specific features related to the music, the therapist, as well as specific music therapy interventions. Future researchers might also examine the differences between music medicine and receptive music listening and MT provided by a MT-BC. This is a crucial item on the research agenda to protect service users from music induced harm (30). However, given the challenges that people with AD may have, we recommend MT/MTT because of the specialized academic and clinical training that MT-BCs receive. Therefore, it would be beneficial for researchers and clinicians to compare MTT to MT as well as other established treatments by measuring neuropsychiatric symptoms. Future service delivery model research is also warranted to compare MT with MTT. For example, the most user-friendly approaches to MTT application should be studied to optimize the clinical impact of music therapy. These suggestions for future research may also consist of clinical trials, effectiveness, feasibility, mechanistic, and refinement studies.

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to provide a rationale for a protocolized MTT intervention to increase accessibility for MT as a psychosocial intervention for neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with AD. We conducted a narrative review of MT publications using the NPI as a dependent measure indexed in PubMed and Google Scholar. Based on the narrative review of eight studies that met our inclusion criteria, MT seems to have positive impacts on neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD. However, we identified an ensuing need for protocolized MT interventions, increased access to MT, and greater awareness of MT. As a relatively inexpensive psychosocial intervention, MTT can be an accessible option with the potential to address these barriers. Although MT can have beneficial effects on neuropsychiatric symptoms in AD, we highlight a subsequent need for MT that is easily accessible and follows a standardized intervention protocol. MTT has the potential to constitute a viable solution to fulfill these needs. Future MTT research from all paradigms is necessary.

Author contributions

SW, AC-T, MS, and SY conceived the concept of the review, performed the research and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported partly by the ITN (Institute of Translational Neuroscience). SY is an ITN Scholar at the University of Minnesota.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Indira Rao for her assistance with the references and Raiden Chen for his assistance with the preparation and references for this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^We use MT-BC to represent qualified practitioners, as we are geographically located in the United States, and this is the official qualification for music therapists (www.cbmt.org). We recognize that other countries have different terminologies for professional qualification.

2. ^We recognize that people with AD can be referred to as patients, clients, or service users depending upon a number of contextual factors including but not limited to setting, country, level of care, and relationship to care provider.

3. ^Typically occurring in adult medical settings, music medicine can be defined as listening to recorded music that is chosen by a medical professional without specialized music training, assessments, or a therapeutic process (Dileo, 1999; Silverman et al., 2016; Yinger & Gooding, 2014).

References

1. Gaugler, J, James, B, Johnson, T, Reimer, J, Solis, M, Weuve, J, et al. 2022 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. (2022) 18:700–89. doi: 10.1002/alz.12638

2. Tampi, RR, and Jeste, DV. Dementia is more than memory loss: neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia and their nonpharmacological and pharmacological management. Am J Psychiatry. (2022) 179:528–43. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.20220508

3. Siafarikas, N, Selbaek, G, Fladby, T, Benth, JŠ, Auning, E, and Aarsland, D. Frequency and subgroups of neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment and different stages of dementia in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. (2018) 30:103–13. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217001879

4. Eikelboom, WS, van den Berg, E, Singleton, EH, Baart, SJ, Coesmans, M, Leeuwis, AE, et al. Neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms across the Alzheimer disease clinical Spectrum: cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Neurology. (2021) 97:e1276–87. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012598

5. Lanctôt, KL, Amatniek, J, Ancoli-Israel, S, Arnold, SE, Ballard, C, Cohen-Mansfield, J, et al. Neuropsychiatric signs and symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease: new treatment paradigms. Alzheimer’s Dement. (2017) 3:440–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2017.07.001

6. Kim, Y, Wilkins, KM, and Tampi, RR. Use of gabapentin in the treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: a review of the evidence. Drugs Aging. (2008) 25:187–96. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825030-00002

7. Eriksson, S. Impact of the environment on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. (2000) 12:89–91. doi: 10.1017/S1041610200006839

8. Linares, C, Culqui, D, Carmona, R, Ortiz, C, and Díaz, J. Short-term association between environmental factors and hospital admissions due to dementia in Madrid. Environ Res. (2017) 152:214–20. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.10.020

9. Smith, GE, O’Brien, PC, Ivnik, RJ, Kokmen, E, and Tangalos, EG. Prospective analysis of risk factors for nursing home placement of dementia patients. Neurology. (2001) 57:1467–73. doi: 10.1212/WNL.57.8.1467

10. Yaffe, K, Fox, P, Newcomer, R, Sands, L, Lindquist, K, Dane, K, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. (2002) 287:2090–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2090

11. FDA; (2023). FDA Approves First Drug to Treat Agitation Symptoms Associated with Dementia due to Alzheimer’s Disease. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-drug-treat-agitation-symptoms-associated-dementia-due-alzheimers-disease

12. Mühlbauer, V, Luijendijk, H, Dichter, MN, Möhler, R, Zuidema, SU, and Köpke, S. Antipsychotics for agitation and psychosis in people with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2019) 2019:CD013304. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013304

13. Almutairi, S, Masters, K, and Donyai, P. The health professional experience of using antipsychotic medication for dementia in care homes: a study using grounded theory and focussing on inappropriate prescribing. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2018) 25:307–18. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12464

14. Schneider, LS, Tariot, PN, Dagerman, KS, Davis, SM, Hsiao, JK, Ismail, MS, et al. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. (2006) 355:1525–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061240

15. Aleixo, MAR, Santos, RL, and Dourado, MCDN. Efficacy of music therapy in the neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia: systematic review. J Bras Psiquiatr. (2017) 66:52–61. doi: 10.1590/0047-2085000000150

16. Ferreri, L, Mas-Herrero, E, Zatorre, RJ, Ripollés, P, Gomez-Andres, A, Alicart, H, et al. Dopamine modulates the reward experiences elicited by music. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2019) 116:3793–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811878116

17. Wang, D, Belden, A, Hanser, SB, Geddes, MR, and Loui, P. Resting-state connectivity of auditory and reward Systems in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Front Hum Neurosci. (2020) 14:280. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2020.00280

18. Baird, A, and Samson, S. Music and dementia In:. Progress in brain research [internet] : Elsevier (2015). 207–35. Available at: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0079612314000296

19. Cuddy, LL, Duffin, JM, Gill, SS, Brown, CL, Sikka, R, and Vanstone, AD. Memory for melodies and lyrics in Alzheimer’s disease. Music Percept. (2012) 29:479–91. doi: 10.1525/mp.2012.29.5.479

20. Cuddy, LL, Sikka, R, and Vanstone, A. Preservation of musical memory and engagement in healthy aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2015) 1337:223–31. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12617

21. Cuddy, LL, and Duffin, J. Music, memory, and Alzheimer’s disease: is music recognition spared in dementia, and how can it be assessed? Med Hypotheses. (2005) 64:229–35. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2004.09.005

22. Kerer, M, Marksteiner, J, Hinterhuber, H, Mazzola, G, Kemmler, G, Bliem, HR, et al. Explicit (semantic) memory for music in patients with mild cognitive impairment and early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Aging Res. (2013) 39:536–64. doi: 10.1080/0361073X.2013.839298

23. Vanstone, AD, and Cuddy, LL. Musical memory in Alzheimer disease. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. (2010) 17:108–28. doi: 10.1080/13825580903042676

24. Beatty, WW, Zavadil, KD, Bailly, RC, and Rixen, GJ. Preserved musical skill in a severely demented patient. Int J Clin Neuropsychol. (1988) 10:158–64.

25. Beatty, WW, Brumback, RA, and Vonsattel, JPG. Autopsy-proven Alzheimer disease in a patient with dementia who retained musical skill in life. Arch Neurol. (1997) 54:1448. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550240008002

26. Jacobsen, JH, Stelzer, J, Fritz, TH, Chételat, G, La Joie, R, and Turner, R. Why musical memory can be preserved in advanced Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. (2015) 138:2438–50. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv135

27. Sena, MK. Music therapy advocacy for professional recognition: a historical perspective and future directions. Music Ther Perspect. (2015) 33:76–85. doi: 10.1093/mtp/miu043

28. Geist, K, Creagan, J, Neugebauer, C, and Elkins, A. Education for a career in music therapy In: A Knight, B LaGasse, and A Clair, editors. Music therapy: An introduction to the profession. Silver Spring, Maryland: American Music Therapy Association (2018). 11–32.

29. Matney, B. Understanding literature reviews: implications for music therapy. Nord J Music Ther. (2018) 27:97–125. doi: 10.1080/08098131.2017.1366543

30. Silverman, MJ, Gooding, LF, and Yinger, O. It’s…Complicated: a theoretical model of music-induced harm. J Music Ther. (2020) 57:251–81. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thaa008

31. Baker, F, and Bor, W. Can music preference indicate mental health status in young people? Australas Psychiatry. (2008) 16:284–8. doi: 10.1080/10398560701879589

32. Lozon, J, and Bensimon, M. Music misuse: a review of the personal and collective roles of “problem music”. Aggress Violent Behav. (2014) 19:207–18. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2014.04.003

33. North, AC, and Hargreaves, DJ. Problem music and self-harming. Suicide Life Threat Behav. (2006) 36:582–90. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.5.582

34. North, AC, and Hargreaves, DJ. Lifestyle correlates of musical preference: 2. Media, leisure time and music. Psychol Music. (2007) 35:179–200. doi: 10.1177/0305735607070302

35. Olsen, KN, Powell, M, Anic, A, Vallerand, RJ, and Thompson, WF. Fans of violent music: the role of passion in positive and negative emotional experience. Music Sci. (2022) 26:364–87. doi: 10.1177/1029864920951611

36. Slade, A, Olsen, KN, and Thompson, WF. An investigation of empathy in male and female fans of aggressive music. Music Sci. (2021) 25:189–211. doi: 10.1177/1029864919860169

37. VanWeelden, K, and Cevasco, AM. Geriatric clients’ preferences for specific popular songs to use during singing activities. J Music Ther. (2009) 46:147–59. doi: 10.1093/jmt/46.2.147

38. VanWeelden, K, and Cevasco, AM. Recognition of geriatric popular song repertoire: a comparison of geriatric clients and music therapy students. J Music Ther. (2010) 47:84–99. doi: 10.1093/jmt/47.1.84

39. Groene, R. The effect of presentation and accompaniment styles on attentional and responsive behaviors of participants with dementia diagnoses. J Music Ther. (2001) 38:36–50. doi: 10.1093/jmt/38.1.36

40. Moore, RS, Staum, MJ, and Brotons, M. Music preferences of the elderly: repertoire, vocal ranges, tempos, and accompaniments for singing. J Music Ther. (1992) 29:236–52. doi: 10.1093/jmt/29.4.236

41. Silverman, MJ. Music therapy and therapeutic Alliance in adult mental health: a qualitative investigation. J Music Ther. (2019) 56:90–116. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thy019

42. Cevasco, AM. Effects of the therapist’s nonverbal behavior on participation and affect of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease during group music therapy sessions. J Music Ther. (2010) 47:282–99. doi: 10.1093/jmt/47.3.282

43. Jones, JD, and Cevasco, AM. A comparison of music therapy students’ and professional music therapists’ nonverbal behavior: a pilot study. Music Ther Perspect. (2007) 25:19–24. doi: 10.1093/mtp/25.1.19

44. Cevasco, AM, and Grant, RE. Value of musical instruments used by the therapist to elicit responses from individuals in various stages of Alzheimer’s disease. J Music Ther. (2006) 43:226–46. doi: 10.1093/jmt/43.3.226

45. Swedberg, YO, and Cevasco-Trotter, A. Music therapy and older adults in the medical setting In: L Gooding, editor. Medical music therapy: Building a comprehensive program. Silver Spring, Maryland: American Music Therapy Association (n.d.)

46. Stegemöller, EL, Izbicki, P, and Hibbing, P. The influence of moving with music on motor cortical activity. Neurosci Lett. (2018) 683:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.06.030

47. Stegemoller, EL. Exploring a neuroplasticity model of music therapy. J Music Ther. (2014) 51:211–27. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thu023

48. Cummings, JL. The neuropsychiatric inventory: assessing psychopathology in dementia patients. Neurology. (1997) 48:10S–6S. doi: 10.1212/WNL.48.5_Suppl_6.10S

49. Cummings, JL, Mega, M, Gray, K, Rosenberg-Thompson, S, Carusi, DA, and Gornbein, J. The neuropsychiatric inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. (1994) 44:2308–14. doi: 10.1212/WNL.44.12.2308

50. Mao, HF, Kuo, CA, Huang, WN, Cummings, JL, and Hwang, TJ. Values of the minimal clinically important difference for the neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaire in individuals with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2015) 63:1448–52. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13473

51. Matziorinis, AM, and Koelsch, S. The promise of music therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: a review. Ann NY Acad Sci. (2022) 1516:11–7. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14864

52. Brotons, M, and Marti, P. Music therapy with Alzheimer’s patients and their family caregivers: a pilot project. J Music Ther. (2003) 40:138–50. doi: 10.1093/jmt/40.2.138

53. Gómez-Gallego, M, Gómez-Gallego, JC, Gallego-Mellado, M, and García-García, J. Comparative efficacy of active group music intervention versus group music listening in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:8067. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18158067

54. Gómez Gallego, M, and Gómez, GJ. Music therapy and Alzheimer’s disease: cognitive, psychological, and behavioural effects. Neurologia. (2017) 32:300–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2015.12.003

55. Giovagnoli, AR, Manfredi, V, Schifano, L, Paterlini, C, Parente, A, and Tagliavini, F. Combining drug and music therapy in patients with moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized study. Neurol Sci. (2018) 39:1021–8. doi: 10.1007/s10072-018-3316-3

56. Li, CH, Liu, CK, Yang, YH, Chou, MC, Chen, CH, and Lai, CL. Adjunct effect of music therapy on cognition in Alzheimer’s disease in Taiwan: a pilot study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. (2015) 11:291–6. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S73928

57. Lyu, J, Zhang, J, Mu, H, Li, W, Champ, M, Xiong, Q, et al. The effects of music therapy on cognition, psychiatric symptoms, and activities of daily living in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. (2018) 64:1347–58. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180183

58. Raglio, A, Bellelli, G, Traficante, D, Gianotti, M, Ubezio, MC, Villani, D, et al. Efficacy of music therapy in the treatment of behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. (2008) 22:158–62. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181630b6f

59. Satoh, M, Yuba, T, Ichi, TK, Okubo, Y, Kida, H, Sakuma, H, et al. Music therapy using singing training improves psychomotor speed in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a neuropsychological and fMRI study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra. (2015) 5:296–308. doi: 10.1159/000436960

60. Leggieri, M, Thaut, MH, Fornazzari, L, Schweizer, TA, Barfett, J, Munoz, DG, et al. Music intervention approaches for Alzheimer’s disease: a review of the literature. Front Neurosci. (2019) 13:132. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00132

61. Moreno-Morales, C, Calero, R, Moreno-Morales, P, and Pintado, C. Music therapy in the treatment of dementia: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Front Med. (2020) 7:160. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00160

62. van der Steen, JT, Smaling, HJ, van der Wouden, JC, Bruinsma, MS, Scholten, RJ, and Vink, AC. Music-based therapeutic interventions for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2018) 7:CD003477. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003477.pub4

63. EMTC. Training Standards. (2023). Available at: https://emtc-eu.com/training/training-standards/

64. Robb, SL, Carpenter, JS, and Burns, DS. Reporting guidelines for music-based interventions. J Health Psychol. (2011) 16:342–52. doi: 10.1177/1359105310374781

65. Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. (n.d.) Alzheimer’s Association. Available at: https://alz.org/

66. CBMT. (n.d.) Available at: https://www.cbmt.org/home/

67. Carr, DB. Motor vehicle crashes and drivers with DAT. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. (1997) 11 Suppl 1:38–41. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199706001-00009

68. Branson, JL. Leaving the profession: a grounded theory exploration of music therapists’ decisions. Voices. (2023) 23 Available at: https://voices.no/index.php/voices/article/view/3259

69. Oden, J. A descriptive analysis of music therapy employment from 2013 to 2019. Music Ther Perspect. (2021) 39:78–85. doi: 10.1093/mtp/miaa021

70. Silverman, MJ, Segall, LE, and Edmonds, T. “I’ve lost my callouses:” a phenomenological investigation of music therapists who left the profession. J Music Ther. (2022) 59:394–429. doi: 10.1093/jmt/thac011

71. Schoonover, J, and Rubin, SE. Incorporating music therapy into primary care. Am Fam Physician. (2022) 106:225A.

72. Alzheimer’s Disease and Dementia. (n.d.) Treatments for behavior. Available at: https://alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/treatments/treatments-for-behavior

73. National Institute on Aging. (n.d.) Managing personality and behavior changes in Alzheimer’s. Available at: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/managing-personality-and-behavior-changes-alzheimers

74. Di Lorito, C, Bosco, A, Rai, H, Craven, M, McNally, D, Todd, C, et al. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis on digital health interventions for people living with dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2022) 37:5730. doi: 10.1002/gps.5730

75. Laver, K, Liu, E, Clemson, L, Davies, O, Gray, L, Gitlin, LN, et al. Does telehealth delivery of a dyadic dementia care program provide a noninferior alternative to face-to-face delivery of the same program? A randomized, controlled trial. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2020) 28:673–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.02.009

76. Saragih, ID, Tonapa, SI, Porta, CM, and Lee, BO. Effects of telehealth intervention for people with dementia and their carers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2022) 54:704–19. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12797

77. Yi, JS, Pittman, CA, Price, CL, Nieman, CL, and Oh, ES. Telemedicine and dementia care: a systematic review of barriers and facilitators. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2021) 22:1396–1402.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.03.015

78. Clements-Cortés, A, Mercadal-Brotons, M, Alcântara Silva, TR, and Vianna, MS. Telehealth music therapy for persons with dementia and/or caregivers. Music Med. (2021) 13:206–10. doi: 10.47513/mmd.v13i3.821

79. Wilhelm, L, and Wilhelm, K. Telehealth music therapy Services in the United States with Older Adults: a descriptive study. Music Ther Perspect. (2022) 40:84–93. doi: 10.1093/mtp/miab028

80. Bates, D. Music therapy ethics “2.0”: preventing user error in technology. Music Ther Perspect. (2014) 32:136–41. doi: 10.1093/mtp/miu030

81. Vaudreuil, R, Langston, DG, Magee, WL, Betts, D, Kass, S, and Levy, C. Implementing music therapy through telehealth: considerations for military populations. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. (2022) 17:201–10. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2020.1775312

82. Knott, D, and Block, S. Virtual music therapy: developing new approaches to service delivery. Music Ther Perspect. (2020) 38:151–6. doi: 10.1093/mtp/miaa017

83. Cole, LP, Henechowicz, TL, Kang, K, Pranjić, M, Richard, NM, Tian, GLJ, et al. Neurologic music therapy via telehealth: a survey of clinician experiences, trends, and recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Neurosci. (2021) 15:648489. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.648489

84. Levy, CE, Spooner, H, Lee, JB, Sonke, J, Myers, K, and Snow, E. Telehealth-based creative arts therapy: transforming mental health and rehabilitation care for rural veterans. Arts Psychother. (2018) 57:20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.aip.2017.08.010

85. Lightstone, AJ, Bailey, SK, and Voros, P. Collaborative music therapy via remote video technology to reduce a veteran’s symptoms of severe, chronic PTSD. Arts Health. (2015) 7:123–36. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2015.1019895

86. de la Rubia Ortí, JE, García-Pardo, MP, Iranzo, CC, Madrigal, JJC, Castillo, SS, Rochina, MJ, et al. Does music therapy improve anxiety and depression in Alzheimer’s patients? J Altern Complement Med. (2018) 24:33–6. doi: 10.1089/acm.2016.0346

87. Guétin, S, Portet, F, Picot, MC, Pommié, C, Messaoudi, M, Djabelkir, L, et al. Effect of music therapy on anxiety and depression in patients with Alzheimer’s type dementia: randomised, controlled study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. (2009) 28:36–46. doi: 10.1159/000229024

88. Hanser, SB, Butterfield-Whitcomb, J, Kawata, M, and Collins, BE. Home-based music strategies with individuals who have dementia and their family caregivers. J Music Ther. (2011) 48:2–27. doi: 10.1093/jmt/48.1.2

89. Ledger, AJ, and Baker, FA. An investigation of long-term effects of group music therapy on agitation levels of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Aging Ment Health. (2007) 11:330–8. doi: 10.1080/13607860600963406

90. Sakamoto, M, Ando, H, and Tsutou, A. Comparing the effects of different individualized music interventions for elderly individuals with severe dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. (2013) 25:775–84. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212002256

Keywords: Alzheimer’s, dementia, geriatrics, music therapy, narrative review, telehealth, neuropsychiatric symptoms

Citation: Wang SG, Cevasco-Trotter AM, Silverman MJ and Yuan SH (2023) A narrative review of music therapy for neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease and rationale for protocolized music teletherapy. Front. Med. 10:1248245. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1248245

Edited by:

Melissa Mercadal-Brotons, Catalonia College of Music, SpainReviewed by:

Suzanne B. Hanser, Berklee College of Music, United StatesConcetta Maria Tomaino, Institute for Music and Neurologic Function, United States

Giuseppe Pulice, Singular - Música y Alzheimer, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Wang, Cevasco-Trotter, Silverman and Yuan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shauna H. Yuan, c3l1YW5AdW1uLmVkdQ==

Sonya G. Wang

Sonya G. Wang Andrea M. Cevasco-Trotter

Andrea M. Cevasco-Trotter Michael J. Silverman

Michael J. Silverman Shauna H. Yuan

Shauna H. Yuan