- 1Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

- 2School of Nursing, Naval Medical University, Shanghai, China

- 3Department of Obstetrics, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

- 4Department of Nursing, Shanghai First Maternity and Infant Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

Objective: To summarize and evaluate the experiences and expectations of newly qualified midwives (NQMs) during their transition from school to clinical practice. One of the main objectives was to provide references for the development of midwifery professional teaching and provide a basis for hospital administrators and instructors of midwifery to develop guidelines and strategies.

Methods: A systemic review of qualitative research using meta-aggregation was conducted. We collected studies from 12 databases between inception and February 2023. All qualitative studies published in English and Chinese that reported on the experiences of NQMs during their transition to practice were included. Two independent reviewers assessed the study quality and the credibility of study findings by using the JBI Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument. The process of searching followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses recommendations.

Results: A total of 14 studies were included, and 84 findings were extracted. The results were grouped into 8 new categories and synthesized into 3 main themes: multi-dimensional challenges, physical and emotional responses, and demands and expectations. The included studies were identified to be of good quality and the results of the methodological quality appraisal were all B grade or higher.

Conclusion: The transition period is a critical career development for NQMs. However, they faced various stress during the period, which had a negative impact on their physical and mental health. Therefore, it’s important to deeply understand their challenges and needs. And effective management strategies should be implemented, such as in-depth cooperation between hospitals and schools, improvement of the clinical transition support system, enhancement of continuing education, and standardization of the management system. This may be beneficial to improve the quality of clinical midwifery and maintain the stability and sustainable development of the midwifery team.

1. Introduction

Improving the health of mothers and newborns is one of the unfinished Millennium Development Goals and remains a priority in the era of sustainable development goals (1). The Global Strategy for Women, Children, and Adolescents Health (2016–2030) also highlights the significance of ensuring that every woman, child, and adolescent has access to fundamental interventions and a strong team of health professionals (2). Particularly, midwives play a significant role in improving mother–child dyads’ health. Approximately two-thirds of maternal and neonatal deaths can be prevented with the assistance of well-trained midwives (3). However, the State of the World’s Midwifery 2021 shows that only 42 percent of people with midwifery skills work in 73 countries where more than 90 percent of all maternal and newborn deaths and stillbirths occur (4). The survey also reveals that there is a 900,000-midwife deficit worldwide, with a projected 750,000-midwife shortage by 2030 (3, 4).

NQMs represent the future of this profession. However, recruitment and retention of midwives is a major challenge, with a high turnover of NQMs. A previous study indicated that the experiences during the transition to practice had an impact on job satisfaction and employee retention, which was a key factor of the global midwifery shortage (5). The transition period is defined as the period of study and adaptation to work as a registered nurse midwife after completion of a recognized midwifery education program (6). For many newly qualified practitioners, the transition period from students to qualified health professionals is typically 12 to 18 months (7). According to the data from the Royal College of Midwives (RCM), the lack of support of NQMs contributes to attrition ranging from 5 to 10% whereby graduates leave during the first year of practice (8).

To facilitate the retention of valuable midwifery workforce, many countries have developed structured transition support programs to help NQMs successfully transition to practice. However, studies conducted in Australia (7), Canada (9), New Zealand (10), and the United Kingdom (11) reported that NQMs still faced many challenges during the period, including but not limited to increased customer care responsibilities, problems with healthcare systems, political, managerial and role uncertainty (12). These challenges caused them to feel insecure, fearful, and stressed (13). Consequently, the smooth transition into their new roles was interfered and increased personnel losses occurred.

It’s crucial to deeply understand their experiences during the transition period and to explore what factors promote or inhibit the progress. Several qualitative studies have explored the challenges and feelings encountered by NQMs during the transition period but did not provide integrated results. As a result, we conducted a qualitative synthesis that could potentially provide a basis for hospital administrators and instructors of midwifery to develop guidelines and strategies to effectively support NQMs during the transition period.

2. Aims

This qualitative systematic review aimed to understand the experiences of NQMs during their transition to practice and to explore factors that promote or inhibit the progress. In particular, the review may provide hospital administrators and instructors of midwifery a new perspective to formulate guidelines and strategies, consequently, it can provide a better training system and platform for NQMs to help them gain fully play their professional roles and positive working experience.

3. Methods

3.1. Design

A systematic review of qualitative research using meta-aggregation was conducted. The Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) checklist (Supplementary Table S1) was used to report the process and results of synthesis, and enhance transparency (14).

3.2. Search strategy

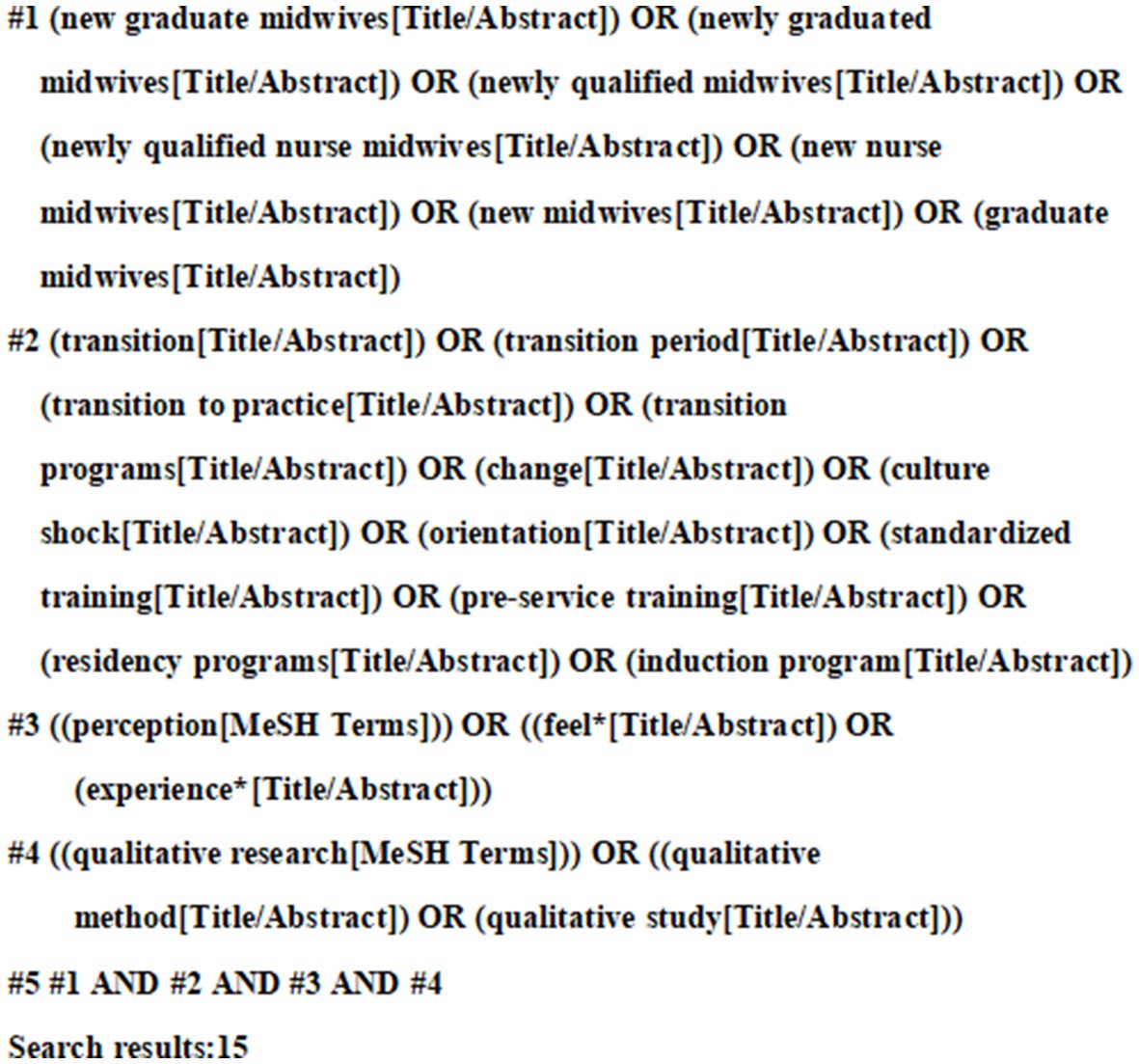

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline was adopted in this review. A three-step approach was used to identify the studies: (a) an initial limited search via PubMed, (b) a systematic search of electronic databases, and (c) a manual search of journal references. To find search terms, a preliminary limited search via PubMed was first carried out to examine the index words and the derivatives of terms for studies linked to the experiences of NQMs during their transition from education into practice. Then, we systematically searched 12 electronic databases, including eight English language databases: PubMed, Web of Science Core Collection (via ISI Web of Science), MEDLINE (via ISI Web of Science), Cochrane Library, LWW (via OVID), CINAHL Complete (via EBSCO), Scopus, and ScienceDirect, and four Chinese databases: China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Wanfang Database (CECDB), VIP Database, and China Biomedical Database (CBM). For different databases, a separate search strategy is designed and optimized based on the corresponding subject terms and search rules. Results were limited to journal articles written in English or Chinese and published before 15 February 2023. The query included five groups of keywords and MeSH terms combined with Boolean operators: (1) (new graduate midwives) OR (newly graduated midwives) OR (newly qualified midwives) OR (newly qualified nurse midwives) OR (new nurse midwives) OR (new midwives) OR (graduate midwives); (2) (transition) OR (transition period) OR (transition to practice) OR (transition programs) OR (change) OR (culture shock) OR (orientation) OR (standardized training) OR (pre-service training) OR (residency programs) OR (induction program); (3) (perception) OR (feel*) OR (experience*); (4) (qualitative research) OR (qualitative method) OR (qualitative study). Finally, the references of each qualifying articles were searched manually to identify further relevant studies. The sample search strategy for PubMed is presented in Figure 1.

3.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

3.3.1. Inclusion criteria

Studies were included according to the following:

Participant (P): Newly qualified midwives (NQMs) started clinical work for less than three years after graduation.

Interest of phenomena (I): The real experiences of NQMs during their transition from education into practice. The focus was on their stressors, demand, and expectation.

Context (Co): Included studies were those performed during their transition from education into practice.

Study design (S): Qualitative research and mixed-method studies from which the qualitative part could be extracted were included. Studies were included that used any qualitative methodology, including but not limited to phenomenology, grounded theory, case studies, action research, ethnography, and feminist research.

3.3.2. Exclusion criteria

Excluded were studies with qualitative data that were analyzed using quantitative methods; duplicate and unavailable full-text literature; non-English or Chinese literature; research not published in peer-reviewed journals, case reports, conference proceedings, poster abstracts, and theses. Additionally, we looked through their sources to find potential pertinent studies while excluding systematic reviews and other reviews.

3.4. Appraisal of methodological quality

By comparing the evaluation criteria of qualitative research, two researchers (JS, XL) who had undergone qualitative research studies and training in evidence-based methods were selected to conduct the study. Two researchers used the “JBI Evidence-Based Quality Evaluation Criteria for Qualitative Studies in Evidence-Based Health Care Centers” for the final independent evaluation of the included studies. Each item is evaluated by “yes,” “no,” “unclear” and “not applicable.” If all 10 items are “yes,” the possibility of bias is minimal and is A. If the above quality criteria are partially met, the possibility of bias is considered to be B. If all items are If “No,” the possibility of bias is considered high as C. After independent evaluation, the results of the two individuals were compared. Third party re-evaluation or arbitration in case of disagreement. The literature with a quality level of C was finally excluded.

3.5. Data extraction and synthesis

According to the JBI meta-aggregation, qualitative data were extracted in two steps. Firstly, publication details (author’s name, publication year, country or region, research aim, research design, method of data collection, sampling and data analysis, participants) and findings were extracted. Secondly, verbatim statements about the experiences of NQMs during their transition to practice were extracted for a subsequent meta-synthesize across all included studies. Two reviewers (JS, XL) independently evaluated the plausibility of each finding and identified them into three levels: (1) Unequivocal (U): relates to evidence beyond a reasonable doubt, which may include findings that are matter of fact, directly reported/observed and not open to challenge; (2) Equivocal (E): those that are, albeit interpretations, plausible in light of data and the theoretical framework. They can be logically inferred from the data; (3) Not Supported (NS): when 1 nor 2 apply and when most notable findings are not supported by the data. The extracted findings that had similar meanings were aggregated to form new categories. Eventually, these categories were further synthesized to generate more comprehensive findings, called synthesis findings.

4. Results

4.1. Search results

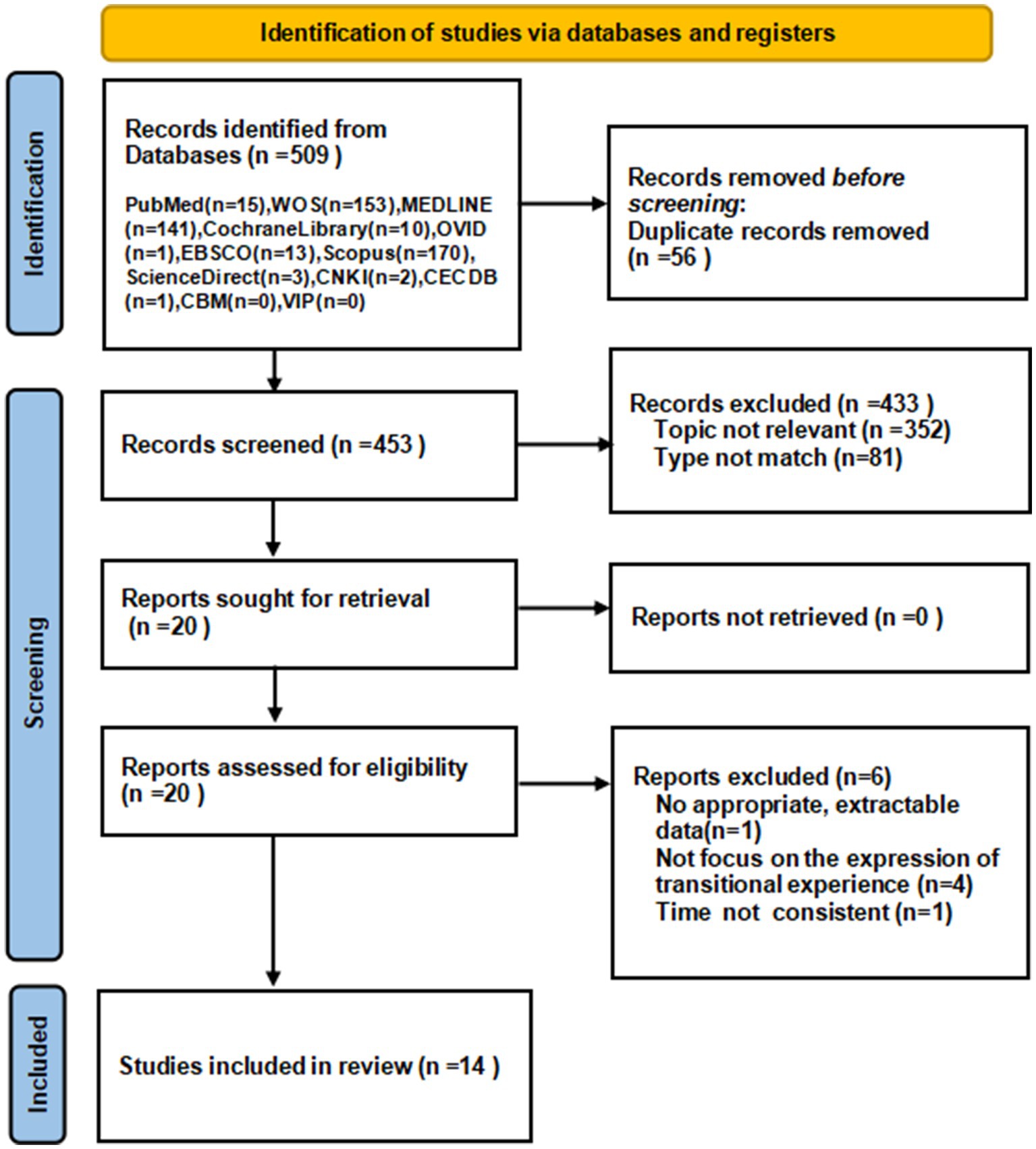

A total of 509 relevant articles were initially searched from the database. 453 articles were collected in total through NoteExpress after removing duplicates. Two researchers independently read the titles, abstracts and keywords to obtain 20 articles, after reading the full text, 14 articles were included. The detailed search and screening process is showed in Figure 2.

4.2. Methodological quality

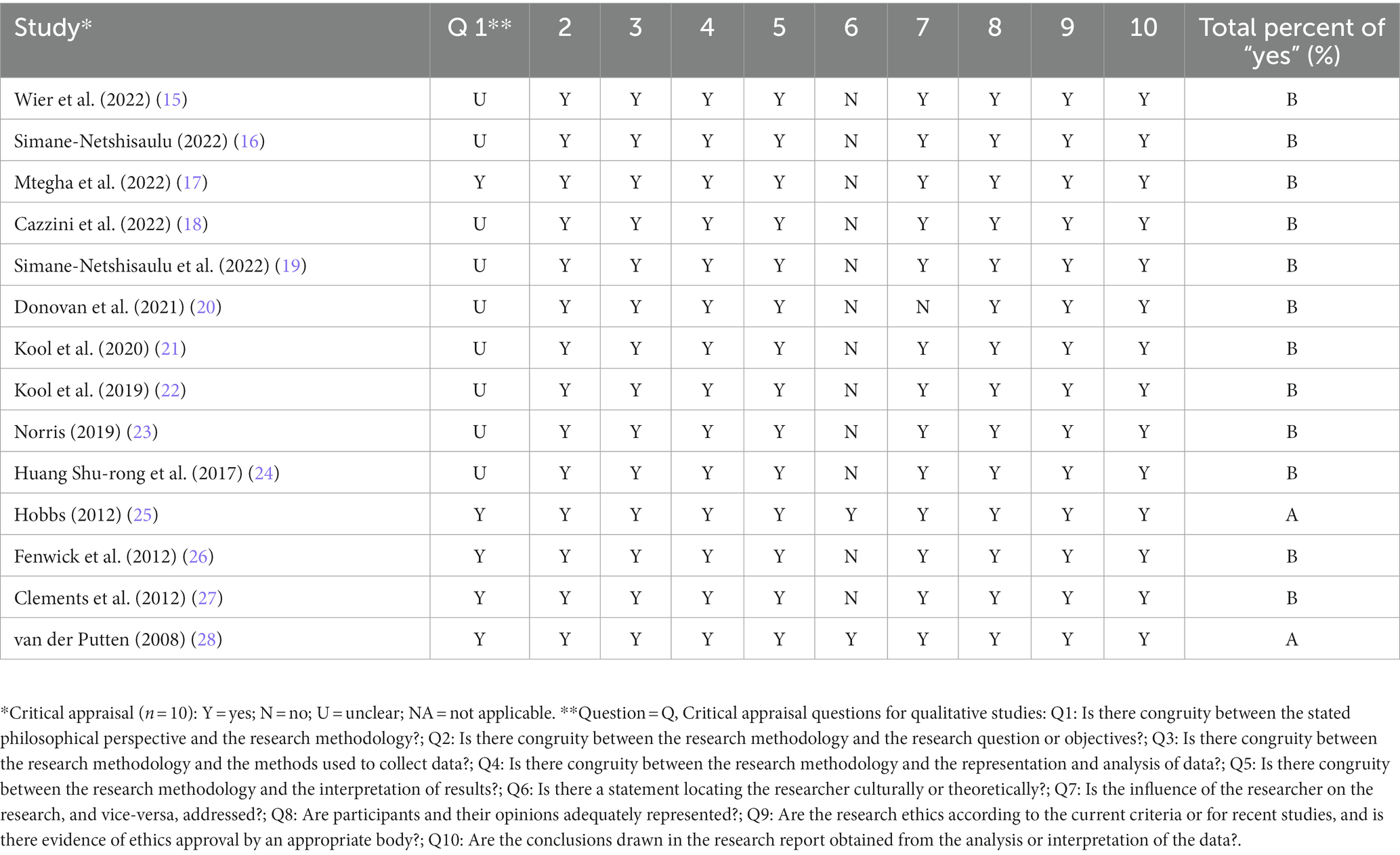

The quality of the included literature was evaluated and the results were all B grade or higher. The results of the methodological quality appraisal are presented in Table 1.

4.3. Study characteristics

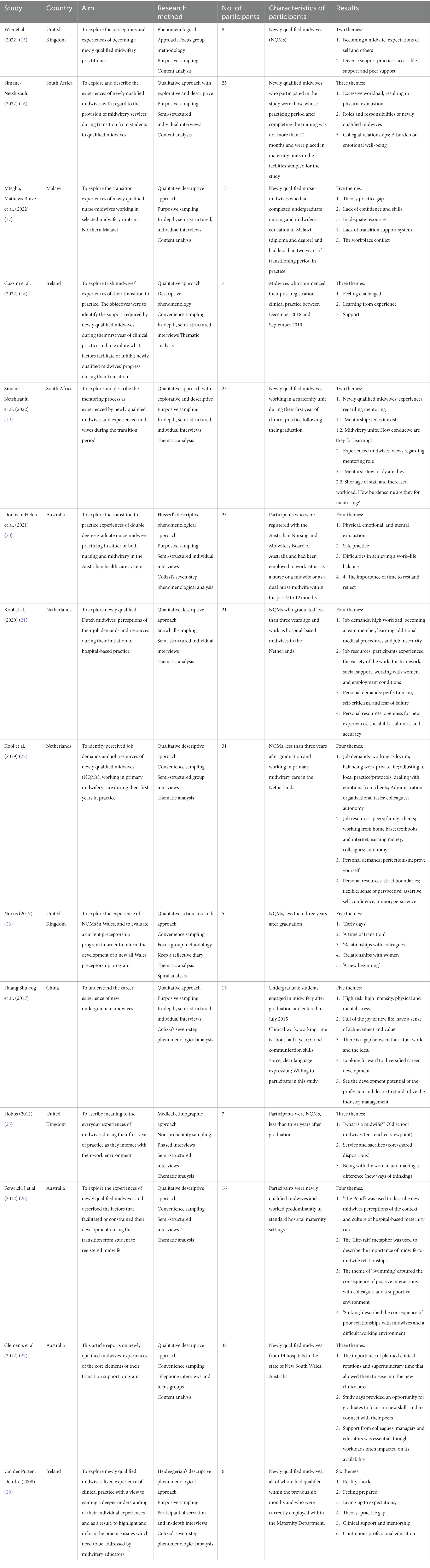

The 14 studies were conducted in the following countries: China (n = 1), Malawi (n = 1), South Africa (n = 2), Netherlands (n = 2), Ireland (n = 2), the United Kingdom (n = 3), and Australia (n = 3). These studies involved 238 NQMs. Study designs included qualitative action-research approach (n = 1), phenomenological approach (n = 4), qualitative descriptive approach (n = 5), mix-method study (n = 2), ethnography (n = 1), and a study described as qualitative without a specific approach (n = 1). All the studies were published after 2008 and were original articles. Study characteristics are presented in Table 2.

4.4. Results of meta-synthesis

The researcher extracted 84 findings from 14 articles and summarized into 8 categories. From the 8 categories, three synthesized findings emerged: multi-dimensional challenges, physical, and emotional responses, and demands and expectations. The main findings with illustrations and levels of credibility are presented in Supplementary Table S2, and the detailed process of synthesis is reported in Supplementary Table S3.

4.4.1. Synthesized finding 1: multi-dimensional challenges

4.4.1.1. Shock from realistic clinical settings

The real work in the delivery room was challenging for NQMs. First, there was a gap between theoretical knowledge in school and clinical practice. Many participants reported that the theoretical knowledge learned in school was relatively outdated or inconsistent with its application in practice. “Upon reaching the ward, I found that most of the guidelines like HIV guidelines, and some reproductive health standards had changed. There were also new things like CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure). So it was really tough for me as I was referring to old things, yet, the practice had changed on the ground” (18). In addition, the delivery room was a place of uncertainty, full of challenges and risks directly related to the safety of the mother-infant dyads’ lives. “Getting a baby into the world alive was what everyone worried about” (26). At the same time, the lack of human resources was a very serious problem, which led to the huge amount of work that individuals need to carry on. “…human resource is a challenge…Despite the nursery ward being one of the busy wards, there are times that you are alone on duty and you are expected to do all the activities…” (17). In addition, the job was insecure and they always faced the possibility of losing their jobs due to the lack of permanent contracts. “Yes, you know…you have no job security, so you take all the work you can get everywhere…that increases pressure” (22).

4.4.1.2. High expectations from themselves and others

NQMs were strict with themselves and others also expected more from them. They were eager to prove their abilities quickly, which put a lot of pressure on themselves. “You want to be the best of the best…I probably put too much pressure on myself…I just need to have confidence and take a deep breath…and I’ll be alright…but then every once I have a little panic…” (15). They viewed them as true midwives and must be responsible for mothers and babies, so they held themselves to a higher standard. “you are more independent as a midwife because you have to make more choices you have to have more clinical judgment…more pressure, more responsibility and being more accountable for what I do” (18). Experienced colleagues also had high expectations of NQMs because they thought that NQMs were fresh out of school and knowledgeable. “I think are they going to perceive me as: well, you are newly qualified and you need to be able to do this…” (15). Besides, they were also expected to do more than work, some even beyond their current capabilities. “After three months I was left in charge of the ward as the only midwife and when I questioned it I was told (by the manager) ‘Oh, you can manage … ‘because you have got experience a nurse’…” (27).

4.4.1.3. Lack of transitional support

Many participants reacted hospitals did not provide a perfect support system during the transition to practice, which increased the difficulty of adapting to new environments and transitioning into new roles. At first, there was a lack of the training about the hospital-related management system. “There are a lot of dynamics in the hospital…And it took me some time to realize which disciplines are involved and which agreements are made per hospital, and about protocols. And even if you have a protocol, the usual way of doing things can be different, and it takes a while before you know this…” (21). Secondly, the absence of training in clinical skills made NQMs scared. “The situation is not good at all; in some instances, you have to learn through trial and error. I was so scared of resuscitating a new-born baby, until one day in which I had to practice it all by myself” (16). Thirdly, NQMs were frustrated about the lack of support from experienced mentors. “Do you know in my whole year as a new grad [graduate] I do not think I worked with an [midwifery] educator once” (26). Finally, NQMs often did not receive a positive response from colleagues when they asked for help. “…however, some are unfriendly. The unfriendly ones give bad and demotivating remarks when we seek for assistance. It’s bad” (19). “…fter you have had handover and they are like, ‘Oh fine, do not worry.’ Then they go to the desk and they are like: ‘I do not want to come on to work after her, she leaves everything for the night staff” (23).

4.4.2. Synthesized finding 2: physical and emotional responses

4.4.2.1. Physical fatigue

NQMs suffered physically fatigue because of the high intensity of work. And due to the shift system, their life was irregular and did not get enough rest, which even affected their safe operation. “It’s just exhausting, just physically. Some days you just need to sleep” (20). “I do not think I will ever get used to shift work! It’s almost debilitating…you just start to doubt yourself and I think ‘Am I safe practicing when I’m this tired or this exhausted?’” (20).

4.4.2.2. Negative emotion: lack of confidence, fear, and loneliness

NQMs’ negative feelings included lack of confidence, fear, and loneliness. When they entered a new environment, due to unfamiliar with the environment and lack of training, they were not confident in themselves. “When we were students, we were never given any chance to practice managing the unit, but suddenly you are expected to manage the unit including patients, staff members, equipment and supplies. This is not easy. Especially because you do not feel confident enough to delegate duties to some members of staff” (16). In addition, they often felt fear when facing some clinical problems alone. “I was absolutely terrified just because I had not done it for so long…and I would be like, I do not know if I can do this. I do not know what I’m doing” (20). For many NQMs who work away from home, they were not accompanied by family and friends and felt very lonely. “Just the loneliness was probably the most emotionally draining thing” (20). It is very important for them to have time to spend time with their family and friends, and to get their support and company. “It’s really important that you are able to debrief with friends and family because you will say things to friends and family that you would not say to work colleagues” (20).

4.4.3. Synthesized finding 3: demands and expectations

4.4.3.1. Support from peers, colleagues, and managers

NQMs desperately needed substantial support from peers, colleagues and managers, which was like a light in the dark, making them less nervous and more confident. Support from peers reduced their anxiety. “[having peer support] should be part of the support process…an opportunity for us to feel like our concerns are being listened too…It’s not just us talking amongst ourselves…” (15). Support from colleagues, especially experienced midwives, helped them smoothly transition, which was essential for them to adapt quickly to their new roles. “…they orientate you, they explain everything to you, the routine, the procedures and practices and they still keep an eye on you, you know make sure you are doing ok and that gives you confidence” (28). In addition, it was important to have an approachable leader who can provide great clinical and emotional support to NQMs. “The manager on the ward was excellent, she was always checking in with you making sure that you were doing okay” (18).

4.4.3.2. Improve professional competence

NQMs wanted to improve their professional skills, including clinical decision-making ability, humanistic care, and clinical professional skills. First, NQMs expected independent clinical decision-making capabilities and they needed to have independent autonomy in the care of their patients. “I also dared to make decisions and I dared to pick up [tasks] independently and it is really not that I needed help with anything and everything. I think that I can generally work independently” (16). Second, almost all the participants hoped to give more humanistic care to women. “My frustration is mainly to do with the women not getting the care that maybe they expected or I expected them to get” (25). “For me, being with the woman is just a part of my soul…but I do not get a lot of time to do that…I have to do a lot of things rather than actually being with woman…” (18). By improving humanistic care, in turn inspires them to work better. “When I support a woman…that is why I chose this profession. Then it is easy to get out of my bed in the night. Moreover, I feel that my work is my passion, and my passion is my work” (22). Finally, NQMs would like to receive more professional training or study in order to adapt faster to the new environment and further strengthen their professional skills. “I hope to continue my study in midwifery and continuously improve my skills in technical operation and clinical thinking” (29).

4.4.3.3. Standardize the management system

NQMs desired to standardize the industry management and establish an independent midwifery management and training system. “For young midwives, there should be a standardized training system, and they should have standardized training just like clinicians. After all, this line of work requires a high level of competence for midwives, and our work is also related to the safety of mothers and babies” (29). Besides, there were some shortcomings about the hospital management systems, such as paying too much attention to employee rank, ignoring NQMs’ opinions and feelings, and focusing solely on number rather than quality of the work. “Midwifery is a hierarchical system. It is based on midwifery-in-charge [and] also who has been here the longest or who has the most experience and it’s like you were in a food chain’” (26). “Midwifery practice requires me to actually give more loyalty to the hospital and do all the tasks that they expect of me in a day to save [them] from being sued or just to say, ‘These jobs have been done’” (26).

5. Discussion

The systematic review of 14 qualitative studies was rigorously conducted by researchers trained in evidence-based nursing, contributing to a more in-depth and comprehensive understanding of experiences of NQMs during the transition period. The main findings indicated that NQMs faced challenges from multiple sources. These challenges mainly derived from the realistic clinical settings. They felt so stressed as a fresh midwife. At the same time, we also discovered their real needs and expectations. Therefore, to ease their physical and mental stress and further create a friendly work environment, transitional support for NQMs should be strengthened and the training system should be improved, which will play a positive role in reducing the resignation rate of new midwives.

Hospitals and schools should collaborate to facilitate a smooth transition to clinical practice for NQMs. Gap between theory and practice, high risk, high intensity, job insecurity are the main challenges NQMs faced during the transition. Complex interpersonal relationships and high-loaded work cause negative work experience, and affect adversely their physical and mental health (30). Therefore, it’s urgent to take various measures to help them meet challenges, and enhance their positive career experience. Hospitals and schools need deep cooperation to provide targeted career guidance to students. During the school, midwifery specialists can introduce the nature, significance, professional content and history of the midwifery profession in China and abroad, and share their professional experiences. Besides, the clinical practice is equally important. The midwifery training room should be available for students so that they can have a preliminary understanding and experience of the clinical midwifery work. This may help them identify and internalize their professionalism. Educators should pay attention to the combination of theoretical and practical teaching, cultivate students’ practical ability, so that they can better adapt to clinical after graduation. At the same time, attention should be paid to improve students’ psychological quality and improve their ability to cope with occupational stress.

The clinical transition support system should be improved to promote positive career experience for NQMs. The multifaceted, multi-disciplinary clinical support system has positive implications for the smooth transition of NQMs to new roles. According to studies, the level of clinical support new midwives receive during the clinical transition greatly influences their clinical competence (31). According to Thunes (32) and Fenwick (33), obstetrics students attribute their clinical success to the practitioners they work together every day. On the one hand, improving the support system can reduce the clinical responsibility and pressure of NQMs and prevent them from intentionally narrowing the scope of their practice for fear of taking risks; on the other hand, it can promote NQMs to maximize the professional role and provide maternal-centered midwifery services, so as to further improve the quality of maternal and infant health care.

Strengthen continuing education to ensure the sustainability of the NQMs team. Many NQMs often feel a lack of expertise and competence when face with complex clinical problems, and continuing professional learning becomes the expectation of most of them. And their new level of responsibility inspires the importance of continuous professional education in order to continue to provide safe care for women. Continuing education programs will help healthcare providers improve their professional competence and adapt them to rapidly changing and new roles (34–36). Particularly, midwives are one of the important healthcare providers, and their continuing education can enhance midwives’ ability to improve maternal and child health status (37).

Standardize the management system and provide a broad career exhibition path for NQMs. They have high expectations for regulated management systems, especially they want independent professional systems and independent professional behavior. At present, in many countries, the midwifery major still belongs to the nursing major (38), and midwives do not have independent professional title evaluation and promotion sequence, and lack of the corresponding assessment, registration and promotion system (38), which forms certain obstacles to the echelon construction of midwifery talents and the development of professional characteristics. Improving the standard management system of midwifery professional education and midwife registration is conducive to enhancing the sense of responsibility and autonomy of NQMs, providing a richer career development path, so as to promote the development of midwifery profession and the retention of talent resources.

6. Conclusion

This qualitative systematic review expounds the experience and feelings of NQMs during the transition to practice. Studies have shown that NQMs face multifaceted challenges, which have negative effects on their physical and mental health. NQMs are at a critical time in their career development, and properly guiding their role change is a difficult but important task. From the perspective of obstetric educators and clinical managers, this study suggests that hospitals and schools collaborate on guidance and intervention to improve clinical transitional support systems, standardize management systems, and strengthen continuing education. And thus, it helps NQMs make a smooth transition to clinical practice, gain positive career experiences, and provide them with a broad career path. This can contribute to the building and sustainable development of the midwifery workforce and better serve people.

7. Limitations

Although a systematic search was conducted using appropriate search strategies, according to the eligible criteria, only qualitative research or mixed-method studies from which qualitative data could be extracted were included. Gray literature and dissertations were not searched; only articles published in indexed journals in either Chinese or English were included. The omittance may have caused information bias. The included studies were of high quality, but two-thirds of the literature omitted information about the researcher’s theoretical or cultural background, which could have an impact on the results.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JS and XL: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing of original draft, and writing – review and editing. YL: conceptualization, methodology, writing of original draft, and writing – review and editing. YL, JL, RZ, and HJ: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and writing – review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by: (1) Technical standard project of Shanghai Municipal 2022 “Action Plan for Science and Technology Innovation” (22DZ2203800), (2) Shanghai Shenkang Hospital Development Center Management Research Project (2022SKMR-18) and (3) Shanghai Shenkang Hospital Development Center Technology Standardization Management and Promotion Project (SHDC22022227).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2023.1242490/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Nove, A , Friberg, IK , de Bernis, L , McConville, F , Moran, AC , Najjemba, M, et al. Potential impact of midwives in preventing and reducing maternal and neonatal mortality and stillbirths: a lives saved tool modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. (2021) 9:e24–32. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30397-1

2. Callister, LC . Global strategy for the health of women, children, and adolescents: 2016-2030. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. (2016) 41:190. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000237

3. Boateng, AB , Opoku, DA , Ayisi-Boateng, NK , Sulemana, A , Mohammed, A , Osarfo, J, et al. Factors influencing turnover intention among nurses and midwives in Ghana. Nurs Res Pract. (2022) 2022:4299702–8. doi: 10.1155/2022/4299702

5. Clements, V , Davis, D , and Fenwick, J . Continuity of care: supporting new graduates to grow into confident practitioners. Int J Childbirth. (2013):3–12. doi: 10.1891/2156-5287.3.1.3

6. Rahmadhena, MP , McIntyre, M , and McLelland, G . New midwives' experiences of transition support during their first year of practice: a qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. (2017) 15:1265–71. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003374

7. Gray, M , Malott, A , Davis, BM , and Sandor, C . A scoping review of how new midwifery practitioners transition to practice in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, United Kingdom and The Netherlands. Midwifery. (2016) 42:74–9. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2016.09.018

8. Shortage of midwives is the reason for high agency staff costs, says RCM. Pract Midwife. (2015) 18:8.

9. Nour, V , and Williams, AM . "Theory becoming alive": the learning transition process of newly graduated nurses in Canada. Can J Nurs Res. (2019) 51:6–13. doi: 10.1177/0844562118771832

10. Dixon, L , Calvert, S , Tumilty, E , Kensington, M , Gray, E , Lennox, S, et al. Supporting New Zealand graduate midwives to stay in the profession: an evaluation of the midwifery first year of practice programme. Midwifery. (2015) 31:633–9. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2015.02.010

11. Lennox, S , Skinner, J , and Foureur, M . Mentorship, preceptorship and clinical supervision: three key processes for supporting midwives. NZ Coll Midwives J. (2008) 39:7–12.

12. Hofler, L , and Thomas, K . Transition of new graduate nurses to the workforce: challenges and solutions in the changing health care environment. N C Med J. (2016) 77:133–6. doi: 10.18043/ncm.77.2.133

13. Labrague, LJ , and McEnroe-Petitte, DM . Job stress in new nurses during the transition period: an integrative review. Int Nurs Rev. (2018) 65:491–504. doi: 10.1111/inr.12425

14. Tong, A , Flemming, K , McInnes, E , Oliver, S , and Craig, J . Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2012) 12:181. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

15. Wier, J , and Lake, K . Making the transition: a focus group study which explores third year student and newly qualified midwives' perceptions and experiences of becoming a registrant midwife. Midwifery. (2022) 111:103377. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2022.103377

16. Simane-Netshisaulu, K , Maputle, M , Netshikweta, LM , and Shilubane, H . Mentorship during transition period: a challenge for newly qualified midwives in Limpopo province of South Africa. Afr Health Sci. (2022) 22:191–9. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v22i1.25

17. Mtegha, MB , Chodzaza, E , Chirwa, E , Kalembo, FW , and Zgambo, M . Challenges experienced by newly qualified nurse-midwives transitioning to practice in selected midwifery settings in Northern Malawi. BMC Nurs. (2022) 21:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12912-022-01012-y

18. Cazzini, H , Cowman, T , Fleming, J , Fletcher, A , Kuriakos, S , Mulligan, K, et al. An exploration of midwives' experiences of the transition to practice in the Republic of Ireland. Br J Midwifery. (2022) 30:136–43. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2022.30.3.136

19. Simane-Netshisaulu, KG . Student to midwife transition: newly qualified midwives? Experiences in Limpopo province. Health SA Gesondheid. (2022) 27:27. doi: 10.4102/hsag.v27i0.1992

20. Donovan, H , Welch, A , and Williamson, M . Reported levels of exhaustion by the graduate nurse midwife and their perceived potential for unsafe practice: a phenomenological study of Australian double degree nurse midwives. Workplace Health Saf. (2021) 69:73–80. doi: 10.1177/2165079920938000

21. Kool, LE , Schellevis, FG , Jaarsma, D , and Feijen-De, JE . The initiation of Dutch newly qualified hospital-based midwives in practice, a qualitative study. Midwifery. (2020) 83:102648. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2020.102648

22. Kool, L , Feijen-de Jong, EI , Schellevis, FG , and Jaarsma, D . Perceived job demands and resources of newly qualified midwives working in primary care settings in the Netherlands. Midwifery. (2019) 69:52–8. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2018.10.012

23. Norris, S . In the wilderness: an action-research study to explore the transition from student to newly qualified midwife. Evid Based Midwifery. (2019) 17:128–34.

24. Huang, S , Yu, Y , Zhou, X , and Cai, W . The occupational experience of the new-recruited undergraduate midwives. Chinese Nursing Education. (2017) 14:692–6.

25. Hobbs, JA . Newly qualified midwives' transition to qualified status and role: assimilating the 'habitus' or reshaping it? Midwifery. (2012) 28:391–9. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2011.04.007

26. Fenwick, J , Hammond, A , Raymond, J , Smith, R , Gray, J , Foureur, M, et al. Surviving, not thriving: a qualitative study of newly qualified midwives' experience of their transition to practice. J Clin Nurs. (2012) 21:2054–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04090.x

27. Clements, V , Fenwick, J , and Davis, D . Core elements of transition support programs: the experiences of newly qualified Australian midwives. Sex Reprod Healthc. (2012) 3:155–62. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2012.08.001

28. van der Putten, D . The lived experience of newly qualified midwives: a qualitative study. Br J Midwifery. (2008) 16:348–58. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2008.16.6.29592

29. Karimyar, JM , Minaei, S , Abdollahifard, S , and Maddahfar, M . The effect of stress management on occupational stress and satisfaction among midwives in obstetrics and gynecology hospital wards in Iran. Glob J Health Sci. (2016) 8:91. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n9p91

30. U-Eun, C , and Hyun-Young, K . The impact of safety climate and fatigue on safety performance of operating room nurses. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. (2016) 22:471. doi: 10.11111/jkana.2016.22.5.471

31. Thunes, S , and Sekse, RJ . Midwifery students first encounter with the maternity ward. Nurse Educ Pract. (2015) 15:243–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2015.01.012

32. Power, A , and Grzelak, I . University midwifery societies: support for student midwives, by student midwives. Br J Midwifery. (2016) 24:787–9. doi: 10.12968/bjom.2016.24.11.787

33. Heslehurst, N , Russell, S , McCormack, S , Sedgewick, G , Bell, R , and Rankin, J . Midwives perspectives of their training and education requirements in maternal obesity: a qualitative study. Midwifery. (2013) 29:736–44. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2012.07.007

34. Elliott, S , Murrell, K , Harper, P , Stephens, T , and Pellowe, C . A comprehensive systematic review of the use of simulation in the continuing education and training of qualified medical, nursing and midwifery staff. JBI Libr Syst Rev. (2011) 9:538–87. doi: 10.11124/01938924-201109170-00001

35. Yolanda, FP , and Magdalena, AC . Factors influencing nursing staff members' participation in continuing education. Rev Lat Am Enferm. (2006) 14:309–15. doi: 10.1590/S0104-11692006000300002

36. Abedian, K , Charati, JY , Samadaee, K , and Shahhosseini, Z . A cross-sectional study of Midwives' perspectives towards their professional educational needs. Mater Sociomed. (2014) 26:182–5. doi: 10.5455/msm.2014.26.182-185

37. O'Connell, MA , and Sosa, G . Midwifery in Abu Dhabi: a descriptive survey of midwives. Women Birth. (2023) 36:e439–44. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2023.02.002

Keywords: newly qualified midwives, transition to practice, experience, meta-synthesis, qualitative systematic review

Citation: Shi J, Li X, Li Y, Liu Y, Li J, Zhang R and Jiang H (2023) Experiences of newly qualified midwives during their transition to practice: a systematic review of qualitative research. Front. Med. 10:1242490. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1242490

Edited by:

Loreto Pantoja, University of Chile, ChileReviewed by:

Xin Li, Chengdu Women and Children’s Central Hospital, ChinaElsa Vitale, Bari Local Health Authority, Italy

Copyright © 2023 Shi, Li, Li, Liu, Li, Zhang and Jiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hui Jiang, amlhbmdodWl0ZXN0QDE2My5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Jinjin Shi

Jinjin Shi Xuemei Li

Xuemei Li Yongqi Li

Yongqi Li Ying Liu3

Ying Liu3 Hui Jiang

Hui Jiang