94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Med., 13 July 2023

Sec. Nephrology

Volume 10 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1179834

This article is part of the Research TopicCaRe Me: Improving the Cardio-Renal-Metabolic Care of Patients through Clinical and Translational ResearchView all 6 articles

The success of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and bariatric surgery in patients with chronic kidney disease has highlighted the importance of glomerular hyperfiltration and hypertrophy in the progression of kidney disease. Sustained glomerular hyperfiltration and hypertrophy can lead to glomerular injury and progressive kidney damage. This article explores the relationship between obesity and chronic kidney disease, focusing on the roles of glomerular hyperfiltration and hypertrophy as hallmarks of obesity-related kidney disease. The pathological mechanisms underlying this association include adipose tissue inflammation, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, chronic systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and overactivation of the sympathetic nervous system, as well as the renin-angiotensin aldosterone system. This article explains how glomerular hyperfiltration results from increased renal blood flow and intraglomerular hypertension, inducing mechanical stress on the filtration barrier and post-filtration structures. Injured glomeruli increase in size before sclerosing and collapsing. Therefore, using extreme values, such as the maximal glomerular diameter, could improve the understanding of the data distribution and allow for better kidney failure predictions. This review provides important insights into the mechanisms underlying glomerular hyperfiltration and hypertrophy and highlights the need for further research using glomerular size, including maximum glomerular profile, calculated using needle biopsy specimens.

Numerous studies have shown that obesity is a significant risk factor for chronic kidney disease (CKD) (1–4) and end-stage kidney disease (5–8). The link between obesity and CKD has been extensively studied, with evidence showing that excess weight and body fat can significantly damage the kidneys over time (9–11). The global spread of obesity has become a pandemic that cannot be ignored in the context of CKD (12–14), as obesity aggravates the prognosis of all kidney diseases, regardless of etiology (13, 15). Furthermore, all patients with CKD have a latent obesity risk due to lifestyle disturbances; as such, CKD and obesity are becoming inseparable. Importantly, the reno-protective effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors (16–20) and bariatric surgery (9, 21–23) have been recently confirmed. Nephrologists are very interested in SGLT2 inhibitors, as, by improving glomerular hyperfiltration, these drugs significantly improve kidney disease prognosis (19, 20). At present, the significance of glomerular hyperfiltration (21, 24–26) and its pathological glomerular hypertrophy (21, 22, 27, 28) within kidney disease have returned to the spotlight. This mini-review focuses on glomerular hyperfiltration and hypertrophy, which are hallmarks of obesity-related kidney diseases; it also discusses the utility of the maximal glomerular diameter (MaxGD) as their clinical indicator and the purpose of glomerulometry in kidney pathology.

Increased visceral fat accumulation can result in adipose tissue inflammation and adipokine dysregulation (29–33), leading to dyslipidemia, chronic systemic inflammation (31, 34, 35), oxidative stress (29), insulin resistance (31, 36), stimulation of the brain melanocortin system (34, 37), overactivation of the sympathetic nervous system (37–39), overactivation of the renin-angiotensin aldosterone system (40–44), mineralocorticoid receptor activation (45), sodium retention (46, 47), and expansion of the extracellular fluid volume (47–49). These conditions have complex interactions, ultimately leading to kidney damage by causing glomerular hyperfiltration (50, 51) and inflammation (52, 53), which are characteristics of obesity-related kidney disease (15, 47, 54–58).

Glomerular hyperfiltration, one of the predominant pathophysiological features in obesity-related glomerulopathy (ORG) (50, 51, 59–64), is histologically characterized by glomerular hypertrophy with tubular hypertrophy (51, 65). Generally, glomerular hyperfiltration is a result of the early changes in intrarenal hemodynamic function, including increased renal blood flow and intraglomerular hypertension (66), in response to various stimuli, such as a high-protein intake (67, 68), hyperglycemia or insulin resistance (69, 70), and obesity or metabolic syndrome (50, 71–73). In obesity, renal plasma flow increases less than glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (50, 62, 71), suggesting renal vasodilation mostly affects the glomerular afferent arteriole (51). Specifically, glomerular hyperfiltration leads to mechanical stress at the filtration barrier (50, 51, 62, 65, 71, 74), stretching the glomerular capillary wall and resulting in various conditions, such as podocyte loss, mesangial expansion and sclerosis, and glomerular hypertrophy. In turn, these will increase the Bowman’s space volume, that is, a large renal corpuscle (65, 74, 75). Additionally, increased proximal tubular flow due to glomerular hyperfiltration increases delivery and reabsorption of water and solutes, causing proximal tubular epithelial hypertrophy (65), proximal tubular lumen enlargement (65), and tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis (50, 51). The increased proximal reabsorption of solutes results in a decreased solute delivery to the macula densa, which in turn influences tubuloglomerular feedback, inducing preglomerular vasodilation and glomerular hyperfiltration similarly to a ‘vicious cycle’ (57, 61). These changes result in the initiation and progression of kidney disease. An elevated single-nephron GFR is associated with obesity, as well as larger nephrons, glomerulosclerosis, and arteriosclerosis on kidney biopsy and risk factors for CKD (76).

In patients with obesity or metabolic syndrome, relevant renal histopathological characteristics include glomerular hypertrophy with an enlargement of Bowman’s space, mesangial cell or matrix proliferation, podocytopathy, glomerular basement membrane thickening, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), global sclerosis, tubular hypertrophy, tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, arterial sclerosis, arterial hyalinosis, and focal dilatation of the afferent arteriole and glomerular perihilar capillaries (50, 57, 63, 77, 78). Furthermore, lipid accumulation in the glomeruli and tubule cells has been confirmed in patients with obesity (3, 57, 79–81). Among these histological parameters, the current gold standard histologic features of ORG in humans are glomerular hypertrophy, large renal corpuscles, podocyte stressor FSGS, and tubular hypertrophy, which imply glomerular hypertension and hyperfiltration (50, 57, 80, 82, 83). Glomerular hypertrophy or a large renal corpuscle has been reported as a potent kidney prognostic indicator in clinical practice (84–87) and plays an important role in patients with ORG as a simple and helpful indicator that incorporates early-to-late disease stages (57, 75, 80, 87). Conversely, while FSGS may indicate the disease severity or long-term kidney prognosis, it is a somewhat nonspecific indicator of kidney disease in relation to showing the result of kidney damage (86). The challenge in tubular hypertrophy is determining which renal tubules should be measured among the myriad of renal tubules in renal biopsy tissue. Furthermore, tubular hypertrophy assessment is complicated by the fact that increased severity of coexisting interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy in biopsy specimens are associated with a worse kidney outcome (88–90). Primarily, glomerular hypertrophy or a large renal corpuscle (52, 75, 84–87, 91) represents both glomerular hyperfiltration and glomerular inflammation and is recognized as an early marker of obesity-related kidney damage (52, 63). Considering the prophylactic significance of early indicators in patients with obesity, increased clinical use of indicators of glomerular hypertrophy or a large renal corpuscle is desired.

Kidney biopsy can help identifying the underlying cause of kidney disease and assess disease progression and treatment effectiveness (92–94). Various histological indices can be used to evaluate glomerular hyperfiltration (65, 75, 84–86, 90, 95–101). Especially, glomerular hypertrophy assessment is thought to be the most clinically significant (84–86, 90, 99, 100). First, glomerular hypertrophy is a direct response to glomerular hyperfiltration and represents the earliest histological change (75, 102). As reported, glomerular hypertrophy and renal hypertrophy are observed soon after the onset of type 1 diabetic nephropathy (103), and persistent renal hypertrophy precedes the development of microalbuminuria and GFR decrease (102). Second, although albuminuria and proteinuria are the leading prognostic factors for CKD and progression to end-stage kidney disease (104, 105), glomerular hypertrophy is associated with albuminuria/proteinuria and kidney function decline to a greater extent than other parameters (80, 84, 86), making it a clinically important parameter to evaluate in patients with glomerular hyperfiltration. Therefore, glomerular hypertrophy assessment can aid in the early detection and monitoring of kidney disease, as well as in the development of targeted treatment strategies (75). Furthermore, glomerular hypertrophy evaluated by glomerular diameter or glomerular area measurements is less prone to measurement variability, and can easily provide a more precise evaluation of glomerular hyperfiltration than tubular measurements, which are more prone to variation in tubular diameter and length (75, 89).

The size of the renal corpuscle, or glomerulus, is an important indicator of renal function and has been associated with the outcomes of kidney diseases in both experimental models (102, 103, 106, 107) and humans (84–86, 108–110). However, the currently used clinical practice guidelines and pathological classifications of glomerulonephritis do not adequately evaluate glomerular or renal corpuscle sizes as markers of a renal lesion (75, 83, 111). When using glomerular hypertrophy as an effective clinical indicator, clinicians should distinguish between physiological and pathological glomerular hypertrophy and ensure the accuracy and consistency of measurements (27, 75). Evaluating the glomerular size in clinical studies can be challenging (84, 112) due to glomeruli heterogeneity in a single kidney (113), presence of sclerosed and collapsing glomeruli, and use of different measurement techniques. Furthermore, the use of differing morphometric techniques (114), sample sizes, and statistical processing in the evaluation of the glomerular size in previous studies may have influenced the inconsistent results in clinical research.

The definitions of “normal” and “diseased” play an important role in medical practice. A clinically useful diagnostic definition of “normal” is based on a measurement rage within which the disease is absent in diagnostic tests (115). In kidney disease, differentiating between morbid and physiological enlargement of renal corpuscles is important, as morbid glomerular hypertrophy may involve irreversible structural changes that can lead to renal function decline (27, 75). Physiological hypertrophy may occur as a normal response to aging or an increased demand, such as in during pregnancy. Conversely, pathological hypertrophy is a maladaptive response to various insults, such as hypertension, diabetes, and glomerulonephritis, and can result in irreversible structural changes in the kidney (27, 75). In a previous study of IgA nephropathy, glomerular hypertrophy above a maximal diameter of 242 μm was associated with follow-up proteinuria aggravation and an increase in serum creatinine levels. Enlargement of the renal corpuscle to more than 1.5 times its original diameter may be considered morbid, and this threshold effect in the renal corpuscle size may be an important consideration when evaluating renal function and disease progression (84).

Importantly, the use of differing morphometric techniques (114), sample sizes, and statistical analyses in the evaluation of the glomerular size in previous studies may have influenced inconsistent results in clinical research. There are two major methods used to investigate the glomerular size or renal corpuscle size in human kidneys: estimating the mean glomerular size and measuring the individual glomerular size (75, 114). The traditional model-based method of Weibel and Gomez is widely applied to estimate the mean glomerular volume in biopsy specimens (116), but it cannot quantify the heterogeneity of the glomerular volume distribution. An individual glomerular volume allows the assessment of glomerular size variability within the kidneys, and two representative methods of measuring individual glomerular volumes are the Cavalieri (117) and maximal profile area (MPA) (118) methods. The MPA method is more feasible and advisable in clinical settings, as it allows the examination of more glomeruli in small tissue samples (119), while being less laborious (114) than the Cavalieri method.

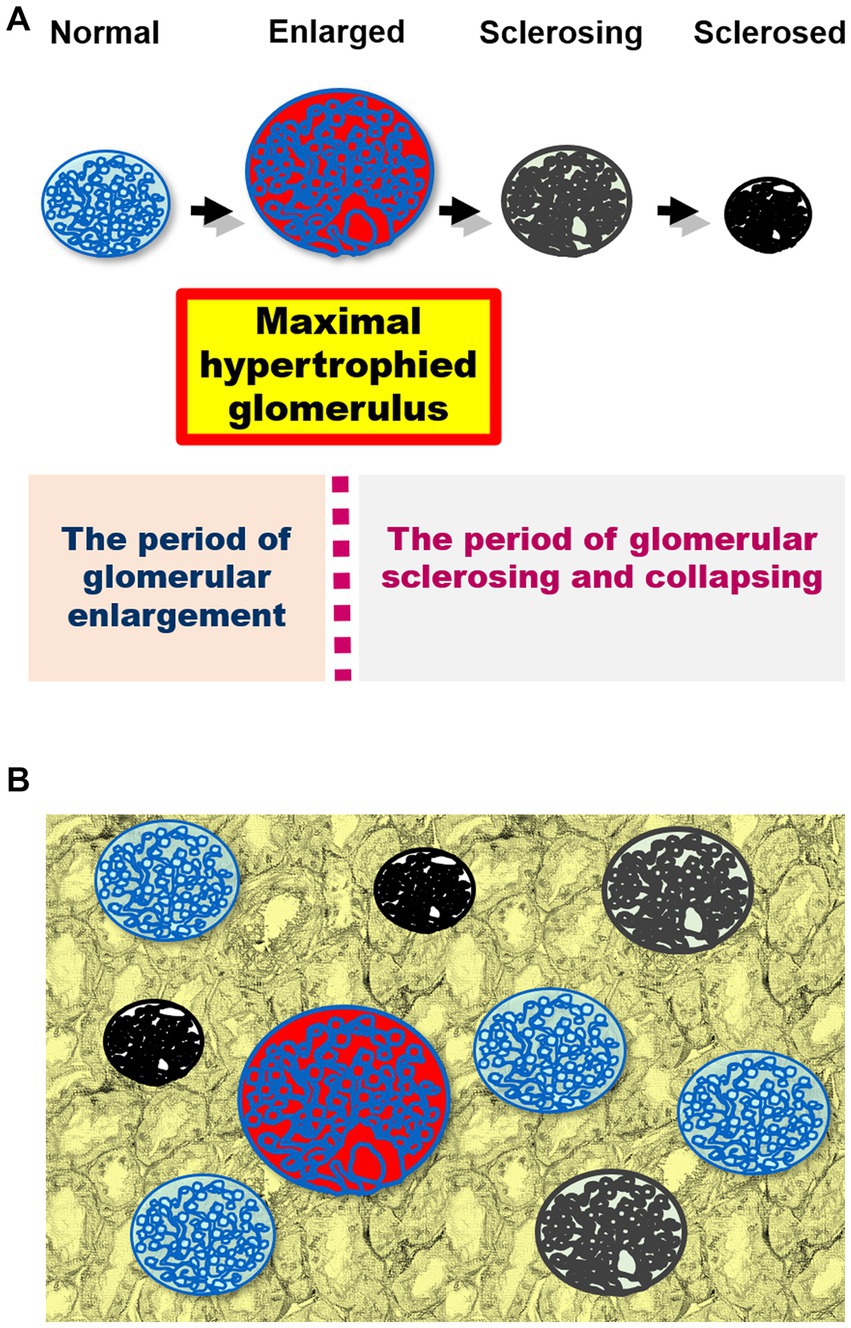

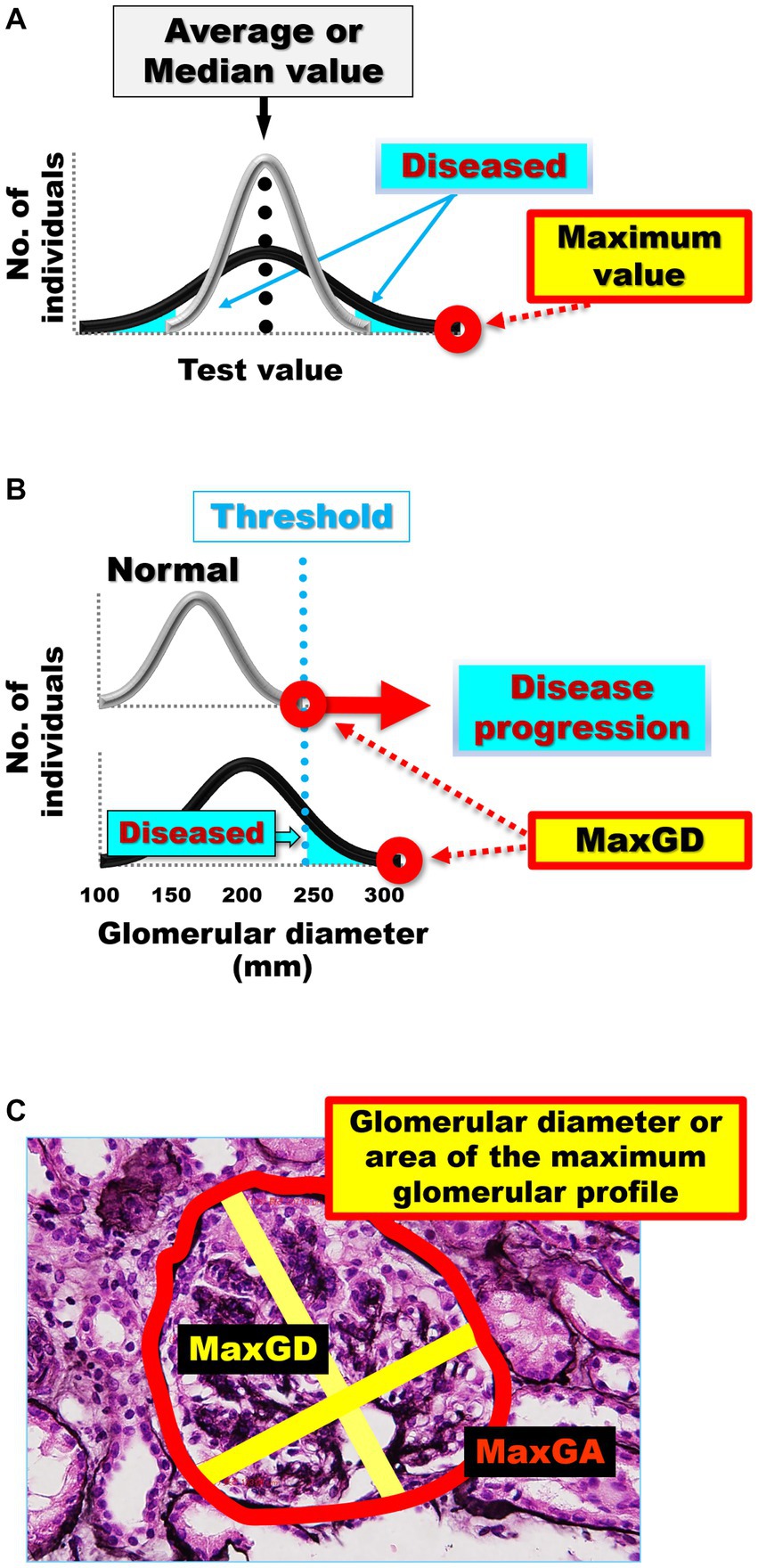

When measuring glomerular size (75, 84), it is important to consider that the size of each glomerulus varies over time (Figure 1A) and that glomeruli of various sizes, including hypertrophied and collapsing glomeruli, can be found within the same kidney (Figure 1B). Indeed, injured glomeruli increase in size before sclerosing and collapsing (120), and sclerosing and normal renal corpuscles with sized in the range of 160–180 μm coexisted in a study of IgA nephropathy (84). Of note, the mean glomerular size may not accurately reflect the true distribution of glomerular sizes in a kidney and may conceal important prognostic information (84). The use of extreme values (i.e., minimum and maximum values) in medical research is relatively rare, despite their applications in other fields, such as hydrology, earth sciences, environmental science, finance, insurance, and genetics, for forecasting unusual events (121). However, we consider that the basal concept of the extreme value theory can be used to predict the occurrence of events, such as kidney failure, from limited samples, such as kidney biopsy specimens (84, 121). This is because the mean and standard deviation, which are commonly used in medical research, are only appropriate for normally distributed data, which is often not the case in biological data (122, 123). Primarily, the mean and standard deviation, which are two of the most common descriptive statistic measures for continuous data and can be calculated from as few as two data points, correctly signify only a “normal” or “Gaussian” value distribution and cannot accurately describe small samples (122). The use of other statistical measures, such as the median and range or maximum values, could provide more informative insights into the distribution of data in diagnostic tests and allow for better prediction of unusual events (102, 115, 124–126) (Figure 2A). The most important phenomenon in kidney disease progression is the fact that injured glomeruli increase in size, represented by a rightward shift in the size distribution, before sclerosing and collapsing (102, 120) (Figure 2B). We consider that the difference in magnitude of a rightward shift in the glomerular size distribution caused by nephron loss, as well as by direct glomerular damage, can help distinguish between compensatory and pathological glomerular hypertrophy (75, 84). The maximum glomerular profile could be a direct indicator of the disease severity or progression, while being less susceptible to nephron loss (27, 121).

Figure 1. (A) A schematic representation of the changes in glomerular size in kidney damage. Injured glomeruli increase in size before sclerosing and collapsing. The maximal hypertrophied glomerulus is shown in red. The course can be divided into two periods using the maximally hypertrophied glomerulus as a boundary: glomerular enlargement and glomerular sclerosing and collapsing. (B) Glomeruli of various sizes (including hypertrophied and collapsing glomeruli) simultaneously exist in the kidney biopsy specimen.

Figure 2. (A) Average or median values often cannot distinguish the differences in distribution curves for normal and diseased in diagnostic tests. The gray distribution curve represents the distribution of healthy participants in a diagnostic test, while the black distribution curve represents the distribution of patients in a diagnostic test. Differences between the black and gray distribution curves can be identified by extreme values, such as maximum and minimum values, rather than by the mean and median values. (B) The differences in the distribution curves of glomerular size between healthy individuals and patients with kidney damage. The gray distribution curve represents the glomerular size distribution in healthy participants without kidney damage. The black distribution curve represents glomerular size distribution in patients with kidney damage. Pathological glomeruli can be diagnosed when hypertrophy progresses beyond a certain threshold. The greater the damage to the kidney, the more the maximum glomerular profile shifts to the right in the kidney biopsy specimens. (C) Glomerular diameter or area of the maximum glomerular profile. Measurement of the MaxGD is indicated by the yellow line and MaxGA is represented by the red line. The MaxGD is calculated as the mean of the maximal diameter of the glomerulus and the maximal chord perpendicular to the maximal diameter of the maximally hypertrophied glomerulus in the area with the maximal profile in each specimen. The position of the geometric center of the maximal profile of the glomerulus is visually identifiable. After drawing the maximal diameter that passes through the geometric center, we draw the maximal chord perpendicular to the maximal diameter. MaxGD, maximal glomerular diameter; MaxGA, maximum glomerular area.

We have proposed a new method that focuses on extreme values, specifically the maximal glomerular profile, such as glomerular diameter (75, 84) or area (87), to predict the progression of CKD (Figure 2C). The clinical value of our pathological evaluation method, which measures only the largest glomerulus instead of the average value of all glomeruli, has been confirmed in subsequent studies. We have demonstrated poor renal prognosis in patients with IgA nephropathy only by using the maximal renal corpuscle diameter, instead of the mean renal corpuscle diameter (84). Glomerular hypertrophy, as indicated by a MaxGD ≥242.3 μm, has been shown to be a significant predictor of poor renal prognosis in patients with IgA nephropathy (84). We also confirmed the MaxGD as an effective pathological factor for predicting renal IgA nephropathy prognosis in another cohort (86) and in a follow-up study (85). In addition, using a combination of traditional statistical methods and machine learning to identify pathophysiological factors associated with glomerular hypertrophy we demonstrated that the MaxGD is not an indicator of compensatory glomerular hypertrophy but of renal damage itself (27).

While glomerular hyperfiltration has received more attention, there is still a lack of clinical research on its pathological index, glomerular hypertrophy. Historically, medical research assessing extreme values is not common, however, evaluating these values may help distinguish between “normal” and “diseased” states. Measurement of the MaxGD is the most clinically superior method for assessing glomerular hypertrophy in the context of glomerular hyperfiltration. This is because it provides direct information on the size of glomeruli, which can increase in response to hyperfiltration. In addition, this method is more objective, reproducible, and less influenced by interobserver variability than other methods. Overall, maximal glomerular diameter measurements offer valuable information for the pathological assessment of glomerular hyperfiltration, and can aid in the diagnosis and management of kidney diseases. Research using the maximum glomerular profile, including the MaxGD, is expected to contribute to the field of kidney disease in the future.

HK performed the literature search and wrote the manuscript. KN and JH were involved in planning and supervising the work. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was partly supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Intractable Renal Diseases Research and Research on Rare and Intractable Diseases, as well as by Health and Labor Sciences Research Grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan.

The authors appreciate the advice on the extreme value theory by Takahiro Mochizuki (deceased June 25, 2017) and his contribution to medical care and medical research in Japan.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Wang, Y, Chen, X, Song, Y, Caballero, B, and Cheskin, LJ. Association between obesity and kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int. (2008) 73:19–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002586

2. Hsu, C-y, McCulloch, C, Iribarren, C, Darbinian, J, and Go, A. Body mass index and risk for end-stage renal disease. Ann Intern Med. (2006) 144:21–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-1-200601030-00006

3. Serra, A, Romero, R, Lopez, D, Navarro, M, Esteve, A, Perez, N, et al. Renal injury in the extremely obese patients with normal renal function. Kidney Int. (2008) 73:947–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002796

4. Yamagata, K, Ishida, K, Sairenchi, T, Takahashi, H, Ohba, S, Shiigai, T, et al. Risk factors for chronic kidney disease in a community-based population: a 10-year follow-up study. Kidney Int. (2007) 71:159–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002017

5. Zoccali, C. The obesity epidemics in ESRD: from wasting to waist? Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2009) 24:376–80. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn589

6. Iseki, K, Ikemiya, Y, Kinjo, K, Inoue, T, Iseki, C, and Takishita, S. Body mass index and the risk of development of end-stage renal disease in a screened cohort. Kidney Int. (2004) 65:1870–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00582.x

7. Vivante, A, Golan, E, Tzur, D, Leiba, A, Tirosh, A, Skorecki, K, et al. Body mass index in 1.2 million adolescents and risk for end-stage renal disease. Arch Internal Med (1960). (2012) 172:1644–50. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.85

8. Chang, A, Grams, M, Ballew, S, Bilo, H, Correa, A, Evans, M, et al. Adiposity and risk of decline in glomerular filtration rate: meta-analysis of individual participant data in a global consortium. BMJ Br Med J. (2019) 364:k5301. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k5301

9. Docherty, N, and le Roux, C. Bariatric surgery for the treatment of chronic kidney disease in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2020) 16:709–20. doi: 10.1038/s41581-020-0323-4

10. Garofalo, C, Borrelli, S, Minutolo, R, Chiodini, P, De Nicola, L, and Conte, G. A systematic review and meta-analysis suggests obesity predicts onset of chronic kidney disease in the general population. Kidney Int. (2017) 91:1224–35. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.12.013

11. Xu, H, Kuja Halkola, R, Chen, X, Magnusson, PKE, Svensson, P, and Carrero, J-J. Higher body mass index is associated with incident diabetes and chronic kidney disease independent of genetic confounding. Kidney Int. (2019) 95:1225–33. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.12.019

12. Amor, A, Casas, A, Pané, A, Ruiz, S, Montagud Marrahi, E, Molina Andújar, A, et al. Weight gain following pancreas transplantation in type 1 diabetes is associated with a worse glycemic profile: A retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. (2021) 179:109026.

13. Chen, Y, Dabbas, W, Gangemi, A, Benedetti, E, Lash, J, Finn, P, et al. Obesity management and chronic kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. (2021) 41:392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2021.06.010

14. Berthoux, F, Mariat, C, and Maillard, N. Overweight/obesity revisited as a predictive risk factor in primary IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2013) 28:iv160–6. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft286

15. Kataoka, H, Nitta, K, and Hoshino, J. Visceral fat and attribute-based medicine in chronic kidney disease. Front Endocrinol. (2023) 14:1097596. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1097596

16. Thomson, S, Rieg, T, Miracle, C, Mansoury, H, Whaley, J, Vallon, V, et al. Acute and chronic effects of SGLT2 blockade on glomerular and tubular function in the early diabetic rat. AJP Regul Integr Comparat Physiol. (2012) 302:R75–83. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00357.2011

17. Wanner, C, Inzucchi, S, Lachin, J, Fitchett, D, von Eynatten, M, Mattheus, M, et al. Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. (2016) 375:323–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515920

18. Perkovic, V, Jardine, M, Neal, B, Bompoint, S, Heerspink, HJL, Charytan, D, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. (2019) 380:2295–306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811744

19. Heerspink, HJL, Stefánsson, B, Correa Rotter, R, Chertow, G, Greene, T, Hou, F-F, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:1436–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024816

20. Pasternak, B, Wintzell, V, Melbye, M, Eliasson, B, Svensson, A-M, Franzén, S, et al. Use of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors and risk of serious renal events: scandinavian cohort study. BMJ. Br Med J. (2020) 369:m1186. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1186

21. Jiang, H-W, Zhou, Y, Zhou, P-Y, Zhang, T-Y, Hu, J-Y, and Bai, X-T. Protective effects of bariatric surgery on kidney functions by inhibiting oxidative stress responses through activating PPARα in rats with diabetes. Front Physiol. (2021) 12:662666. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.662666

22. Xiong, Y, Zhu, W, Xu, Q, Ruze, R, Yan, Z, Li, J, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy attenuates diabetic nephropathy by upregulating nephrin expressions in diabetic obese rats. Obes Surg. (2020) 30:2893–904. doi: 10.1007/s11695-020-04611-3

23. Favre, G, Anty, R, Canivet, C, Clément, G, Ben Amor, I, Tran, A, et al. Determinants associated with the correction of glomerular hyper-filtration one year after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. (2017) 13:1760–6. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.07.018

24. Cherney, DZI, Perkins, B, Soleymanlou, N, Maione, M, Lai, V, Lee, A, et al. Renal hemodynamic effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. (2014) 129:587–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.005081

25. Feng, Y, Zhong, C, Niu, J, Zhang, L, Zhao, Y, Wang, W, et al. Effects of sleeve gastrectomy on lipid and energy metabolism in ZDF rats via PI3K/AKT pathway. Am J Transl Res. (2018) 10:3713–22.

26. Cortinovis, M, Perico, N, Ruggenenti, P, Remuzzi, A, and Remuzzi, G. Glomerular hyperfiltration. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2022) 18:435–51. doi: 10.1038/s41581-022-00559-y

27. Ushio, Y, Kataoka, H, Iwadoh, K, Ohara, M, Suzuki, T, Hirata, M, et al. Machine learning for morbid glomerular hypertrophy. Sci Rep. (2022) 12:19155. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-23882-7

28. Neff, K, Elliott, J, Corteville, C, Abegg, K, Boza, C, Lutz, T, et al. Effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and diet-induced weight loss on diabetic kidney disease in the Zucker diabetic fatty rat. Surg Obes Relat Dis. (2017) 13:21–7. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.08.026

29. Hosogai, N, Fukuhara, A, Oshima, K, Miyata, Y, Tanaka, S, Segawa, K, et al. Adipose tissue hypoxia in obesity and its impact on adipocytokine dysregulation. Diabetes. (2007) 56:901–11. doi: 10.2337/db06-0911

30. Hall, JE, da Silva, AA, Do Carmo, JM, Dubinion, J, Hamza, S, Munusamy, S, et al. Obesity-induced hypertension: role of sympathetic nervous system, leptin, and melanocortins. J Biol Chem. (2010) 285:17271–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.113175

31. Gregor, M, and Hotamisligil, G. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu Rev Immunol. (2011) 29:415–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101322

32. Ouchi, N, Parker, J, Lugus, J, and Walsh, K. Adipokines in inflammation and metabolic disease. Nat Rev Immunol. (2011) 11:85–97. doi: 10.1038/nri2921

33. Sharma, K, Ramachandrarao, S, Qiu, G, Usui, HK, Zhu, Y, Dunn, SR, et al. Adiponectin regulates albuminuria and podocyte function in mice. J Clin Invest. (2008) 118:1645–56. doi: 10.1172/jci32691

34. Jais, A, and Brüning, J. Hypothalamic inflammation in obesity and metabolic disease. J Clin Investig. (2017) 127:24–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI88878

35. Hotamisligil, G. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. (2006) 444:860–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05485

36. Spoto, B, Pisano, A, and Zoccali, C. Insulin resistance in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2016) 311:F1087–108. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00340.2016

37. Shi, Z, Wong, J, and Brooks, V. Obesity: sex and sympathetics. biology of sex. Differences. (2020) 11:10. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00286-8

38. Alvarez, G, Beske, S, Ballard, T, and Davy, K. Sympathetic neural activation in visceral obesity. Circulation. (2002) 106:2533–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000041244.79165.25

39. Brooks, V, Shi, Z, Holwerda, S, and Fadel, P. Obesity-induced increases in sympathetic nerve activity: sex matters. Auton Neurosci. (2015) 187:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2014.11.006

40. Gupte, M, Thatcher, S, Boustany Kari, C, Shoemaker, R, Yiannikouris, F, Zhang, X, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 contributes to sex differences in the development of obesity hypertension in C57BL/6 mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. (2012) 32:1392–9. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248559

41. Xue, B, Yu, Y, Zhang, Z, Guo, F, Beltz, T, Thunhorst, R, et al. Leptin mediates high-fat diet sensitization of angiotensin II-elicited hypertension by Upregulating the brain renin-angiotensin system and inflammation. Hypertension. (2016) 67:970–6. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06736

42. Engeli, S, Böhnke, J, Gorzelniak, K, Janke, J, Schling, P, Bader, M, et al. Weight loss and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Hypertension. (2005) 45:356–62. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000154361.47683.d3

43. Tuck, ML, Sowers, J, Dornfeld, L, Kledzik, G, and Maxwell, M. The effect of weight reduction on blood pressure, plasma renin activity, and plasma aldosterone levels in obese patients. N Engl J Med. (1981) 304:930–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198104163041602

44. Achard, V, Boullu Ciocca, S, Desbriere, R, Nguyen, G, and Grino, M. Renin receptor expression in human adipose tissue. AJP Regul Integr Comparat Physiol. (2007) 292:R274–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00439.2005

45. de Paula, R, da Silva, A, and Hall, J. Aldosterone antagonism attenuates obesity-induced hypertension and glomerular hyperfiltration. Hypertension. (2004) 43:41–7. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000105624.68174.00

46. Hall, J. The kidney, hypertension, and obesity. Hypertension. (2003) 41:625–33. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000052314.95497.78

47. Hall, J, Do Carmo, J, da Silva, A, and Wang, Z. Obesity, kidney dysfunction and hypertension: mechanistic links. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2019) 15:367–85. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0145-4

48. Neeland, I, Ross, R, Després, J-P, Matsuzawa, Y, Yamashita, S, Shai, I, et al. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2019) 7:715–25. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30084-1

49. da Silva, A, do Carmo, J, Li, X, Wang, Z, Mouton, A, and Hall, J. Role of Hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in hypertension: metabolic syndrome revisited. Can J Cardiol. (2020) 36:671–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.02.066

50. Chagnac, A, Herman, M, Zingerman, B, Erman, A, Rozen-Zvi, B, Hirsh, J, et al. Obesity-induced glomerular hyperfiltration: its involvement in the pathogenesis of tubular sodium reabsorption. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2008) 23:3946–52. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn379

51. Chagnac, A, Zingerman, B, Rozen Zvi, B, and Herman, EM. Consequences of glomerular Hyperfiltration: the role of physical forces in the pathogenesis of chronic kidney disease in diabetes and obesity. Nephron J. (2019) 143:38–42. doi: 10.1159/000499486

52. Wu, Y, Liu, Z, Xiang, Z, Zeng, C, Chen, Z, Ma, X, et al. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: insights from gene expression profiles of the glomeruli derived from renal biopsy samples. Endocrinology. (2006) 147:44–50. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0641

53. Liu, Y, Wang, L, Luo, M, Chen, N, Deng, X, He, J, et al. Inhibition of PAI-1 attenuates perirenal fat inflammation and the associated nephropathy in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. AJP Endocrinol. Metabolism. (2019) 316:E260–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00387.2018

54. Kotsis, V, Martinez, F, Trakatelli, C, and Redon, J. Impact of obesity in kidney diseases. Nutrients. (2021) 13:4482. doi: 10.3390/nu13124482

55. Praga, M, and Morales, E. The fatty kidney: obesity and renal disease. Nephron. (2017) 136:273–6. doi: 10.1159/000447674

56. Martínez Montoro, J, Morales, E, Cornejo Pareja, I, Tinahones, F, and Fernández, GJ. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: current approaches and future perspectives. Obes Rev. (2022) 23:e13450. doi: 10.1111/obr.13450

57. D’Agati, VD, Chagnac, A, de Vries, AP, Levi, M, Porrini, E, Herman-Edelstein, M, et al. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: clinical and pathologic characteristics and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2016) 12:453–71. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2016.75

58. Wang, M, Wang, Z, Chen, Y, and Dong, Y. Kidney damage caused by obesity and its feasible treatment drugs. Int J Mol Sci. (2022) 23:23. doi: 10.3390/ijms23020747

59. Praga, M, Borstein, B, Andres, A, Arenas, J, Oliet, A, Montoyo, C, et al. Nephrotic proteinuria without hypoalbuminemia: clinical characteristics and response to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. Am J Kidney Dis. (1991) 17:330–8. doi: 10.1016/S0272-6386(12)80483-5

60. Brenner, BM, Lawler, EV, and Mackenzie, HS. The hyperfiltration theory: a paradigm shift in nephrology. Kidney Int. (1996) 49:1774–7. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.265

61. Vallon, V, Richter, K, Blantz, RC, Thomson, S, and Osswald, H. Glomerular hyperfiltration in experimental diabetes mellitus: potential role of tubular reabsorption. J Am Soc Nephrol. (1999) 10:2569–76. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10122569

62. Chagnac, A, Weinstein, T, Korzets, A, Ramadan, E, Hirsch, J, and Gafter, U. Glomerular hemodynamics in severe obesity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2000) 278:F817–22. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.5.F817

63. Henegar, JR, Bigler, SA, Henegar, LK, Tyagi, SC, and Hall, JE. Functional and structural changes in the kidney in the early stages of obesity. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2001) 12:1211–7. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1261211

64. Yang, S, Cao, C, Deng, T, and Zhou, Z. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: a latent change in obesity requiring more attention. Kidney Blood Press Res. (2020) 45:510–22. doi: 10.1159/000507784

65. Tobar, A, Ori, Y, Benchetrit, S, Milo, G, Herman Edelstein, M, Zingerman, B, et al. Proximal tubular hypertrophy and enlarged glomerular and proximal tubular urinary space in obese subjects with proteinuria. PLoS One. (2013) 8:e75547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075547

66. Helal, I, Fick Brosnahan, G, Reed Gitomer, B, and Schrier, R. Glomerular hyperfiltration: definitions, mechanisms and clinical implications. Nat Rev Nephrol. (2012) 8:293–300. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.19

67. Bosch, JP, Lauer, A, and Glabman, S. Short-term protein loading in assessment of patients with renal disease. Am J Med. (1984) 77:873–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90529-1

68. Bergström, J, Ahlberg, M, and Alvestrand, A. Influence of protein intake on renal hemodynamics and plasma hormone concentrations in normal subjects. Acta Med Scand. (1985) 217:189–96. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1985.tb01655.x

69. Bank, N. Mechanisms of diabetic hyperfiltration. Kidney Int. (1991) 40:792–807. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.277

70. Keller, CK, Bergis, KH, Fliser, D, and Ritz, E. Renal findings in patients with short-term type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. (1996) 7:2627–35. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V7122627

71. Wuerzner, G, Pruijm, M, Maillard, M, Bovet, P, Renaud, C, Burnier, M, et al. Marked association between obesity and glomerular hyperfiltration: a cross-sectional study in an African population. Am J Kidney Dis. (2010) 56:303–12. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.017

72. Bosma, RJ, van der Heide, JJ, Oosterop, EJ, de Jong, PE, and Navis, G. Body mass index is associated with altered renal hemodynamics in non-obese healthy subjects. Kidney Int. (2004) 65:259–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00351.x

73. Tomaszewski, M, Charchar, FJ, Maric, C, McClure, J, Crawford, L, Grzeszczak, W, et al. Glomerular hyperfiltration: a new marker of metabolic risk. Kidney Int. (2007) 71:816–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002160

74. Chagnac, A, Weinstein, T, Herman, M, Hirsh, J, Gafter, U, and Ori, Y. The effects of weight loss on renal function in patients with severe obesity. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2003) 14:1480–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000068462.38661.89

75. Kataoka, H, Mochizuki, T, and Nitta, K. Large renal corpuscle: clinical significance of evaluation of the largest renal corpuscle in kidney biopsy specimens. Contrib Nephrol. (2018) 195:20–30. doi: 10.1159/000486931

76. Denic, A, Mathew, J, Lerman, L, Lieske, J, Larson, J, Alexander, M, et al. Single-nephron glomerular filtration rate in healthy adults. N Engl J Med. (2017) 376:2349–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614329

77. Lin, L, Tan, W, Pan, X, Tian, E, Wu, Z, and Yang, J. Metabolic syndrome-related kidney injury: a review and update. Front Endocrinol. (2022) 13:904001. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.904001

78. D'Agati, V. Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Semin Nephrol. (2003) 23:117–34. doi: 10.1053/snep.2003.50012

79. Goumenos, DS, Kawar, B, El Nahas, M, Conti, S, Wagner, B, Spyropoulos, C, et al. Early histological changes in the kidney of people with morbid obesity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2009) 24:3732–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp329

80. Kambham, N, Markowitz, GS, Valeri, AM, Lin, J, and D'Agati, VD. Obesity-related glomerulopathy: an emerging epidemic. Kidney Int. (2001) 59:1498–509. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590041498.x

81. Kato, S, Nazneen, A, Nakashima, Y, Razzaque, MS, Nishino, T, Furusu, A, et al. Pathological influence of obesity on renal structural changes in chronic kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol. (2009) 13:332–40. doi: 10.1007/s10157-009-0169-3

82. Stasi, A, Cosola, C, Caggiano, G, Cimmarusti, M, Palieri, R, Acquaviva, P, et al. Obesity-related chronic kidney disease: principal mechanisms and new approaches in nutritional management. Front. Nutr. (2022) 9:925619. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.925619

83. D'Agati, VD, Fogo, AB, Bruijn, JA, and Jennette, JC. Pathologic classification of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a working proposal. Am J Kidney Dis. (2004) 43:368–82. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.10.024

84. Kataoka, H, Ohara, M, Honda, K, Mochizuki, T, and Nitta, K. Maximal glomerular diameter as a 10-year prognostic indicator for IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. (2011) 26:3937–43. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr139

85. Kataoka, H, Ohara, M, Suzuki, T, Inoue, T, Akanuma, T, Kawachi, K, et al. Time series changes in pseudo-R2 values regarding maximum glomerular diameter and the Oxford MEST-C score in patients with IgA nephropathy: a long-term follow-up study. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0232885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232885

86. Kataoka, H, Moriyama, T, Manabe, S, Kawachi, K, Ushio, Y, Watanabe, S, et al. Maximum glomerular diameter and Oxford MEST-C score in IgA nephropathy: the significance of time-series changes in Pseudo-R(2) values in relation to renal outcomes. J Clin Med. (2019) 8:8. doi: 10.3390/jcm8122105

87. Kataoka, H, Ohara, M, Shibui, K, Sato, M, Suzuki, T, Amemiya, N, et al. Overweight and obesity accelerate the progression of IgA nephropathy: prognostic utility of a combination of BMI and histopathological parameters. Clin Exp Nephrol. (2012) 16:706–12. doi: 10.1007/s10157-012-0613-7

88. D'Agati, VD, Kaskel, FJ, and Falk, RJ. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. N Engl J Med. (2011) 365:2398–411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1106556

89. Denic, A, Glassock, RJ, and Rule, AD. Structural and functional changes with the aging kidney. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. (2016) 23:19–28. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2015.08.004

90. Denic, A, Elsherbiny, H, Mullan, A, Leibovich, B, Thompson, RH, Ricaurte Archila, L, et al. Larger nephron size and Nephrosclerosis predict progressive CKD and mortality after radical nephrectomy for tumor and independent of kidney function. J Am Soc Nephrol. (2020) 31:2642–52. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020040449

91. Brenner, BM. Hemodynamically mediated glomerular injury and the progressive nature of kidney disease. Kidney Int. (1983) 23:647–55. doi: 10.1038/ki.1983.72

92. Hull, K, Adenwalla, S, Topham, P, and Graham, BM. Indications and considerations for kidney biopsy: an overview of clinical considerations for the non-specialist. Clin Med. (2022) 22:34–40. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2021-0472

93. Roberts, IS, Cook, HT, Troyanov, S, Alpers, CE, Amore, A, Barratt, J, et al. The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: pathology definitions, correlations, and reproducibility. Kidney Int. (2009) 76:546–56. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.168

94. Cattran, DC, Coppo, R, Cook, HT, Feehally, J, Roberts, ISD, Troyanov, S, et al. The Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: rationale, clinicopathological correlations, and classification. Kidney Int. (2009) 76:534–45. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.243

95. Moriya, T, Yamagishi, T, Matsubara, M, and Ouchi, M. Serial renal biopsies in normo-and microalbuminuric patients with type 2 diabetes demonstrate that loss of renal function is associated with a reduction in glomerular filtration surface secondary to mesangial expansion. J Diabetes Complicat. (2019) 33:368–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2019.02.002

96. Vallon, V, and Thomson, S. Renal function in diabetic disease models: the tubular system in the pathophysiology of the diabetic kidney. Annu Rev Physiol. (2012) 74:351–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153333

97. Fogo, AB. Glomerular hypertension, abnormal glomerular growth, and progression of renal diseases. Kidney Int Suppl. (2000) 75:S15–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.57.s75.5.x

98. Young, RJ, Hoy, WE, Kincaid Smith, P, Seymour, AE, and Bertram, JF. Glomerular size and glomerulosclerosis in Australian aborigines. Am J Kidney Dis. (2000) 36:481–9. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.9788

99. Hoy, WE, Hughson, MD, Diouf, B, Zimanyi, M, Samuel, T, McNamara, BJ, et al. Distribution of volumes of individual glomeruli in kidneys at autopsy: association with physical and clinical characteristics and with ethnic group. Am J Nephrol. (2011) 33:15–20. doi: 10.1159/000327044

100. Hoy, WE, Hughson, MD, Zimanyi, M, Samuel, T, Douglas-Denton, R, Holden, L, et al. Distribution of volumes of individual glomeruli in kidneys at autopsy: association with age, nephron number, birth weight and body mass index. Clin Nephrol. (2010) 74:S105–12. doi: 10.5414/CNP74S105

101. Hayslett, JP, Kashgarian, M, and Epstein, FH. Functional correlates of compensatory renal hypertrophy. J Clin Invest. (1968) 47:774–82. doi: 10.1172/jci105772

102. Toyota, E, Ogasawara, Y, Fujimoto, K, Kajita, T, Shigeto, F, Asano, T, et al. Global heterogeneity of glomerular volume distribution in early diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. (2004) 66:855–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00816.x

103. Miller, PL, Rennke, HG, and Meyer, TW. Glomerular hypertrophy accelerates hypertensive glomerular injury in rats. Am J Phys. (1991) 261:F459–65. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1991.261.3.F459

104. Coresh, J, Heerspink, HJL, Sang, Y, Matsushita, K, Arnlov, J, Astor, B, et al. Change in albuminuria and subsequent risk of end-stage kidney disease: an individual participant-level consortium meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2019) 7:115–27. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30313-9

105. Kataoka, H, Ono, K, Mochizuki, T, Hanafusa, N, Imai, E, Hishida, A, et al. A body mass index-based cross-classification approach for the assessment of prognostic factors in chronic kidney disease progression. Kidney Blood Press Res. (2019) 44:362–83. doi: 10.1159/000501021

106. Fries, JW, Sandstrom, DJ, Meyer, TW, and Rennke, HG. Glomerular hypertrophy and epithelial cell injury modulate progressive glomerulosclerosis in the rat. Lab Investig. (1989) 60:205–18.

107. Cahill, MM, Ryan, GB, and Bertram, JF. Biphasic glomerular hypertrophy in rats administered puromycin aminonucleoside. Kidney Int. (1996) 50:768–75. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.375

108. Fogo, A, Hawkins, EP, Berry, PL, Glick, AD, Chiang, ML, MacDonell, RC Jr, et al. Glomerular hypertrophy in minimal change disease predicts subsequent progression to focal glomerular sclerosis. Kidney Int. (1990) 38:115–23. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.175

109. Osterby, R, and Gundersen, HJ. Glomerular size and structure in diabetes mellitus. I. Early abnormalities. Diabetologia. (1975) 11:225–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00422326

110. Zerbini, G, Bonfanti, R, Meschi, F, Bognetti, E, Paesano, PL, Gianolli, L, et al. Persistent renal hypertrophy and faster decline of glomerular filtration rate precede the development of microalbuminuria in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. (2006) 55:2620–5. doi: 10.2337/db06-0592

111. Trimarchi, H, Barratt, J, Cattran, DC, Cook, HT, Coppo, R, Haas, M, et al. Oxford classification of IgA nephropathy 2016: an update from the IgA nephropathy classification working group. Kidney Int. (2017) 91:1014–21. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.02.003

112. Azevedo, F, Alperovich, G, Moreso, F, Ibernon, M, Goma, M, Fulladosa, X, et al. Glomerular size in early protocol biopsies is associated with graft outcome. Am J Transplant. (2005) 5:2877–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01126.x

113. Schmitz, A, Gundersen, HJ, and Osterby, R. Glomerular morphology by light microscopy in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Lack of glomerular hypertrophy. Diabetes. (1988) 37:38–43. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.37.1.38

114. Lane, PH, Steffes, MW, and Mauer, SM. Estimation of glomerular volume: a comparison of four methods. Kidney Int. (1992) 41:1085–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.165

115. How to read clinical journals: II. To learn about a diagnostic test. Can Med Assoc J. (1981) 124:703–10.

116. Weibel, ER, and Gomez, DM. A principle for counting tissue structures on random sections. J Appl Physiol. (1962) 17:343–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1962.17.2.343

117. Gundersen, HJ, and Jensen, EB. The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology and its prediction. J Microsc. (1987) 147:229–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1987.tb02837.x

118. Yoshida, Y, Fogo, A, and Ichikawa, I. Glomerular hemodynamic changes vs. hypertrophy in experimental glomerular sclerosis. Kidney Int. (1989) 35:654–60. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.35

119. Pagtalunan, ME, Drachman, JA, and Meyer, TW. Methods for estimating the volume of individual glomeruli. Kidney Int. (2000) 57:2644–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00125.x

120. Yoshida, Y, Kawamura, T, Ikoma, M, Fogo, A, and Ichikawa, I. Effects of antihypertensive drugs on glomerular morphology. Kidney Int. (1989) 36:626–35. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.239

121. Thomas, M, Lemaitre, M, Wilson, ML, Viboud, C, Yordanov, Y, Wackernagel, H, et al. Applications of extreme value theory in public health. PLoS One. (2016) 11:e0159312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159312

122. Lang, T. Twenty statistical errors even you can find in biomedical research articles. Croat Med J. (2004) 45:361–70.

123. Feinstein, AR. X and iprP: an improved summary for scientific communication. J Chronic Dis. (1987) 40:283–8. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90043-9

124. Murray, GD. The task of a statistical referee. Br J Surg. (1988) 75:664–7. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800750714

125. Manabe, S, Kataoka, H, Mochizuki, T, Iwadoh, K, Ushio, Y, Kawachi, K, et al. Maximum carotid intima-media thickness in association with renal outcomes. J Atheroscler Thromb. (2021) 28:491–505. doi: 10.5551/jat.57752

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, glomerular hyperfiltration, glomerular hypertrophy, obesity, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, visceral fat, inflammation, extreme value

Citation: Kataoka H, Nitta K and Hoshino J (2023) Glomerular hyperfiltration and hypertrophy: an evaluation of maximum values in pathological indicators to discriminate “diseased” from “normal”. Front. Med. 10:1179834. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1179834

Received: 05 March 2023; Accepted: 05 June 2023;

Published: 13 July 2023.

Edited by:

Pedro Ventura-Aguiar, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, United StatesReviewed by:

Bojan Jelakovic, University of Zagreb, CroatiaCopyright © 2023 Kataoka, Nitta and Hoshino. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hiroshi Kataoka, a2F0YW9rYUB0d211LmFjLmpw

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.