- 1Department of Interventional Radiology, Guizhou Medical University Affiliated Cancer Hospital, Guiyang, China

- 2Department of Pathology, The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, China

- 3Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

- 4Department of Radiology, The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, China

- 5Department of Radiology, The Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang, China

- 6Department of Liver Surgery, The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, Changsha, China

Background: Both the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging and the Hong Kong Liver Cancer (HKLC) staging have their own definitions of ideal patients for liver resection (IPLR) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). This study aimed to compare the prognosis of IPLRs between the BCLC and HKLC staging systems, and to identify patients who may benefit from liver resection (LR) in the HKLC staging but beyond the BCLC staging.

Methods: This retrospective study evaluated 1,296 consecutive patients with HCC who underwent LR between August 2013 and April 2021 (457 patients and 1,046 patients were IPLR according to the BCLC and HKLC staging systems, respectively). Overall survival (OS) was compared between the two groups. To assess potential benefit of LR for IPLR in the HKLC staging but beyond the BCLC staging, univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to determine prognostic factors of OS, and prognostic stratification was performed based on the selected prognostic factors. The IPLRs in the HKLC staging but beyond the BCLC staging were divided into subgroups according to the prognostic stratification and separately compared with the IPLRs in the BCLC staging.

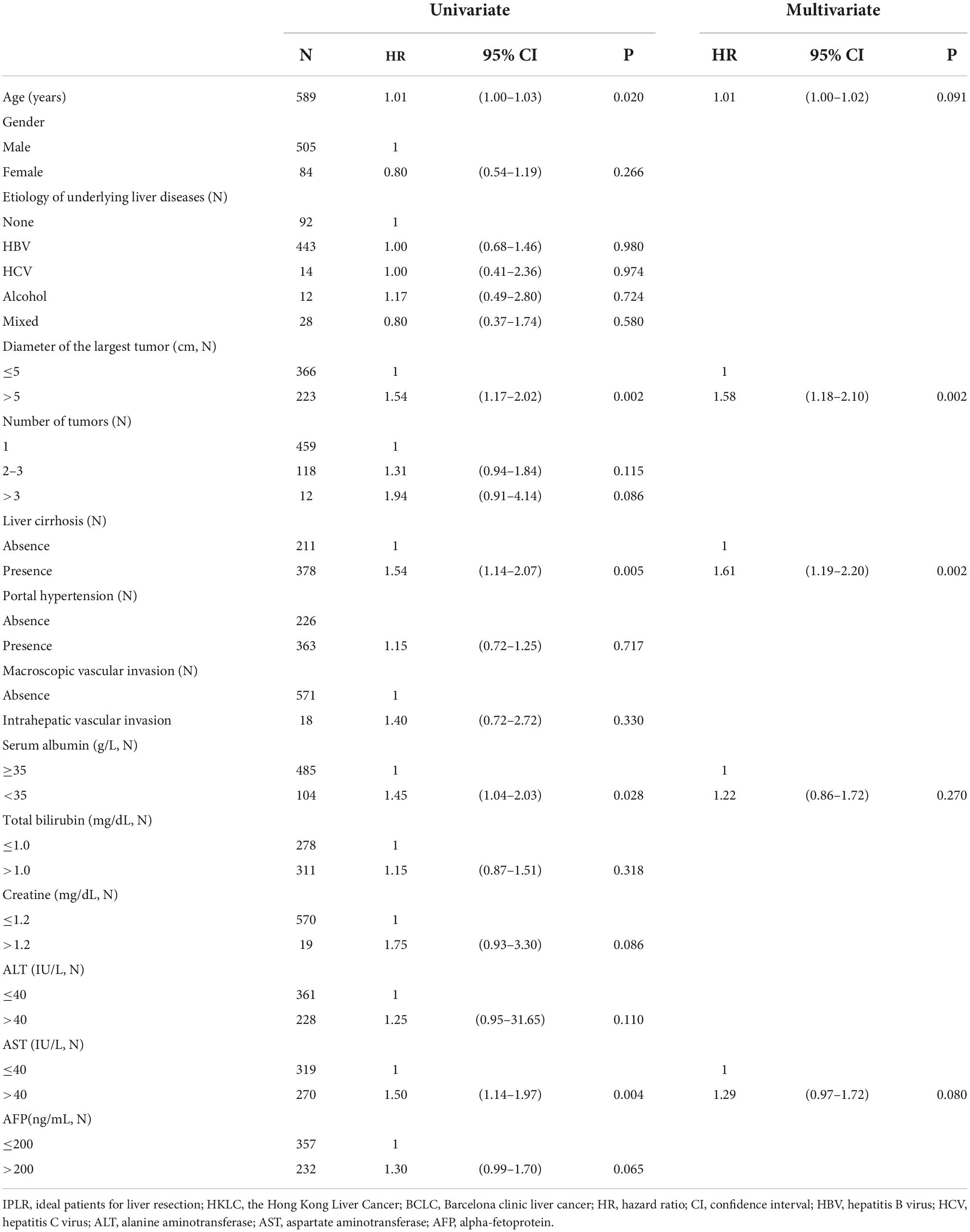

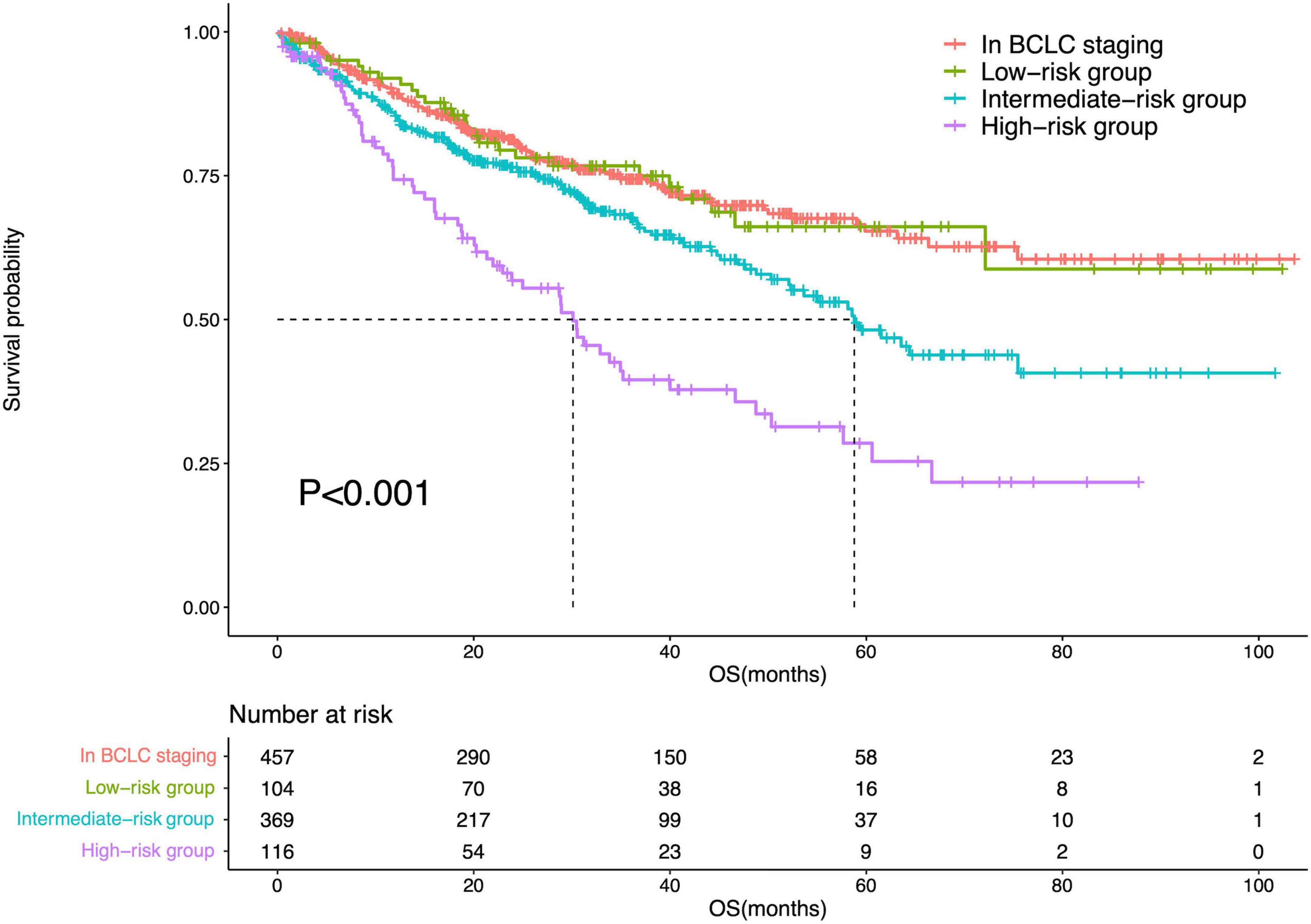

Results: OS was different between the two staging systems (P = 0.011). All the 457 IPLRs in the BCLC staging were also the IPLRs in the HKLC staging. Diameter of the largest tumor5 cm (HR = 1.58; 95% CI: 1.18–2.10; P = 0.002) and liver cirrhosis (HR = 1.61; 95% CI: 1.19–2.20; P = 0.002) were risk factors for poor OS in IPLRs in the HKLC staging but beyond the BCLC staging; hence, patients were divided into the low-risk (n = 104), intermediate-risk (n = 369), and high-risk groups (n = 116) accordingly. There was no difference in OS between patients in the BCLC staging and patients in low-risk group (P = 0.996). However, OS was significantly different between patients in the BCLC staging and those in intermediate-risk (P = 0.003) and high-risk groups (P < 0.001).

Conclusion: IPLRs in the BCLC staging system have better prognosis. However, IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging may have equivalent prognosis to IPLRs in the BCLC staging if the tumor size is ≤ 5 cm and liver cirrhosis is absent.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver cancer worldwide, with high morbidity and mortality rates (1). Several guidelines suggest liver resection (LR) as a main curative treatment option for HCC (2, 3). However, the prognosis of HCC after LR differs significantly owing to the heterogeneity of the HCC population (4). Several scoring and staging systems have been developed to stratify the prognosis of patients with HCC (5–7), with the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system being the most popular treatment guideline in Western countries (8). The BCLC staging system has been endorsed by both the European Association for the Study of the Liver and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. However, the BCLC staging system is not widely accepted in Asia, because the cause of HCC in the east is different to that in west. The Hong Kong Liver Cancer (HKLC) staging system was developed in Asia in 2014 (9). Like the BCLC staging system, the HKLC staging system also incorporates performance status (PS), liver function, and tumor burden and links prognostic classification to treatment indications. Both staging systems have proposed ideal patients for LR (IPLR), and the definitions of IPLR between two staging systems are rather different. Several studies have compared the prognostic predictive value of these two staging systems for HCC (10–13). However, the prognosis of IPLRs between these two staging systems still remain unknown. In addition, the definition in IPLR in the BCLC staging system is usually considered to be conservative while that in the HKLC staging is considered to be aggressive. Therefore, it needs to be determined whether the IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system may potentially benefit from the LR. As such, this study aimed to (1) compare the difference in overall survival (OS) of IPLRs between the BCLC and the HKLC staging; (2) compare the difference in OS between IPLRs in the BCLC staging system and those in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system; and (3) investigate the risk factors of poor OS and identify potential patients who may benefit from LR in IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

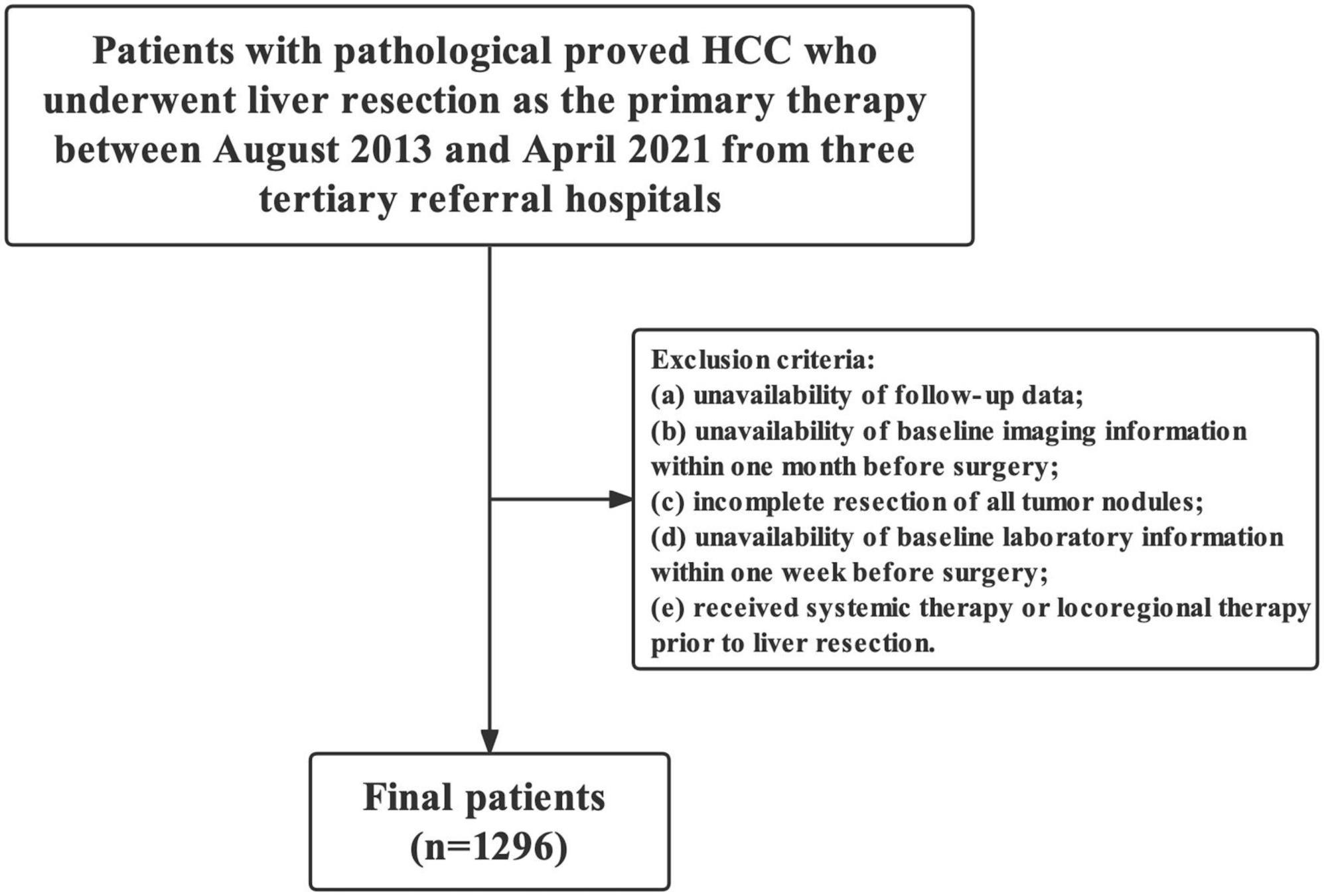

This retrospective study evaluated consecutive patients with pathologically proven HCC who underwent LR in three tertiary referral hospitals between August 2013 and April 2021. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) unavailability of follow-up data, (2) unavailability of baseline imaging information within 1 month preoperatively, (3) incomplete resection of all tumor nodules, (4) unavailability of baseline laboratory information within 1 week preoperatively, and (5) history of systemic therapy or locoregional therapy prior to LR.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of our hospitals and was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The institution review board waived the requirement for written informed consent owing to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data collection

Data on clinical variables, including age, sex, etiology of underlying liver diseases, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status score, were collected. Imaging parameters included the diameter of the largest tumor, number of tumors, ascites, macroscopic vascular invasion, liver cirrhosis, and portal hypertension. Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed by pathology, which was defined as an advanced form of progressive hepatic fibrosis with distortion of the hepatic architecture and regenerative nodule formation. In our institutions, direct measurement of portal venous pressure was not routinely performed; therefore, portal hypertension was defined as either splenomegaly, ascites, or varices on imaging or a platelet count < 100 × 109. Laboratory parameters included neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, platelet count, serum albumin, total bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), creatinine, international normalized ratio, and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP).

Follow-up protocol and outcome measures

Patients were observed during follow-up every 2–3 months postoperatively and at least every 6 months thereafter. Follow-up comprised routine measurements of serum AFP levels and liver function and liver ultrasonography to monitor for recurrence. If recurrence was suspected, contrast-enhanced computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging was performed to verify the recurrence. If tumor recurrence occurred, the choice of treatment modality was based on the tumor site, liver function, and general condition of the patient. The primary outcome measure was OS, defined as the time interval between the date of surgery and the date of any-cause death. The last follow-up was defined as the time of the last telephone interview (March 2022) or the last visit to the hospital if a telephone interview was unavailable.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) (age is presented as mean and standard deviation) and compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test, Student’s t-test or Kruskal-Wallis test, or One-way ANOVA (if appropriate). Meanwhile, categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test (if appropriate). The difference in OS between IPLRs in the BCLC staging system and those in the HKLC staging system was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using log-rank tests. Similarly, the difference in OS was also compared between IPLRs in the BCLC staging and those in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system. The risk factors for poor OS in IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system were determined. Differences in sex, age, diameter of the largest tumor, number of tumors, etiology of underlying liver diseases, liver cirrhosis, albumin, total bilirubin, ALT, AST, AFP, portal hypertension, macroscopic vascular invasion, and creatinine according to OS were compared using univariate Cox regression analysis. The optimal cut-off values for serum albumin (≥ 35/ < 35 g/L), total bilirubin (≤ 1.0/ > 1.0 mg/dL), ALT (≤ 40/ > 40 IU/L), AST (≤ 40/ > 40 IU/L), and creatinine (≤ 1.2/ > 1.2 mg/dL) were determined based on the upper or lower limits of the normal range. For the diameter of the largest tumor, number of tumors, and AFP level, the optimal cut-off values were 5 cm, single/2–3/ > 3, and 200 ng/mL, respectively.

Significant variables in the univariate analysis (i.e., those with P-values < 0.05) were entered in a multivariate backward Cox regression analysis. The prognostic stratification for IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system was performed. To identify patients who may benefit from LR in IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system, the prognostic stratification was performed by assigning exact points for each variable in proportion to the beta coefficients in the final Cox regression model with statistically significant predictors. The total points for each patient were the sum of the points of the identified parameters. The patients were then stratified into low, intermediate, and high risk of death groups using a set of clinical factors that had the best prognostic performance in the multivariate Cox regression analysis. The differences in the OS of each group were compared with those of patients in the BCLC staging system. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) or R software (version 4.0.2).1 All tests were two sided, and P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the entire study population

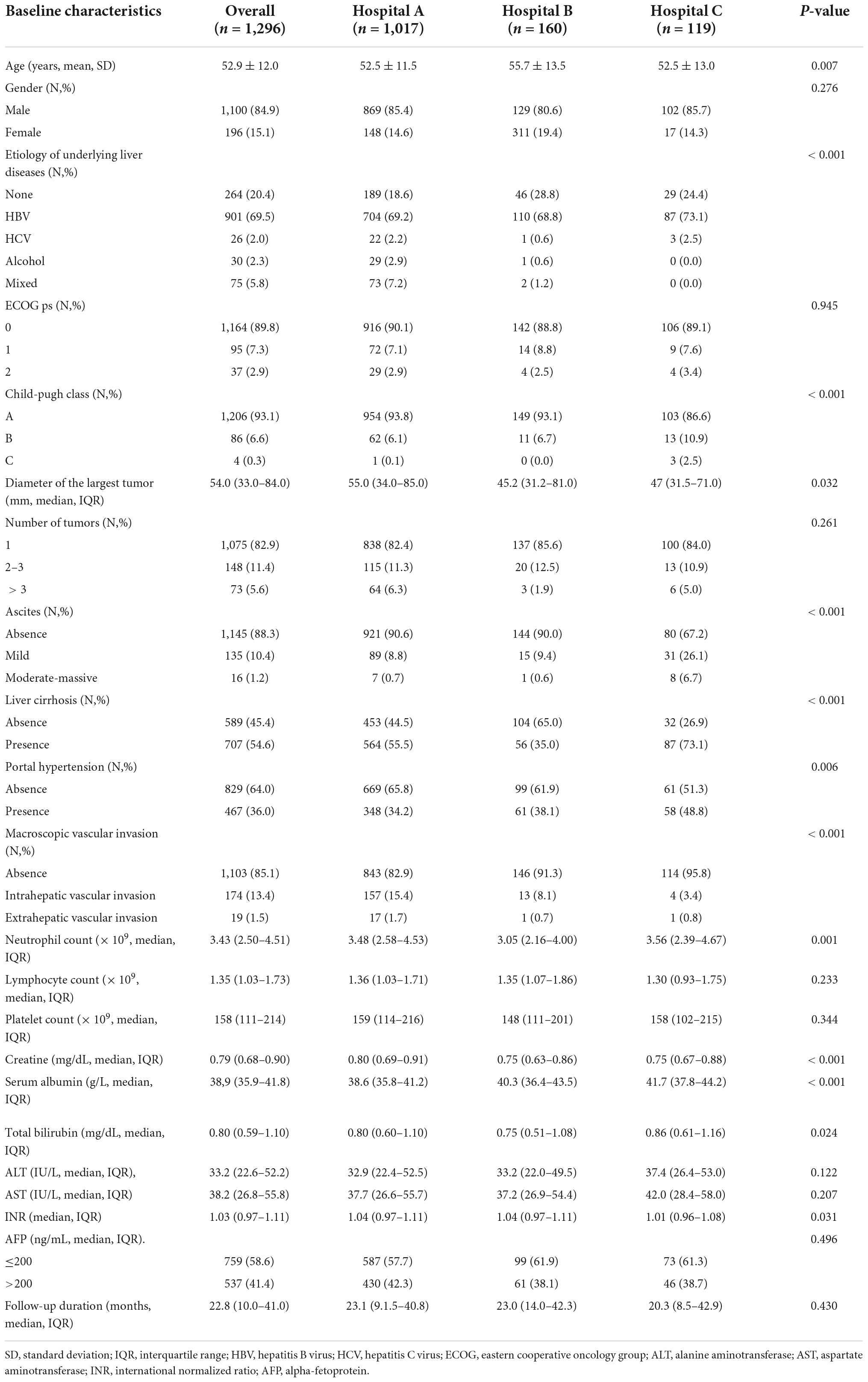

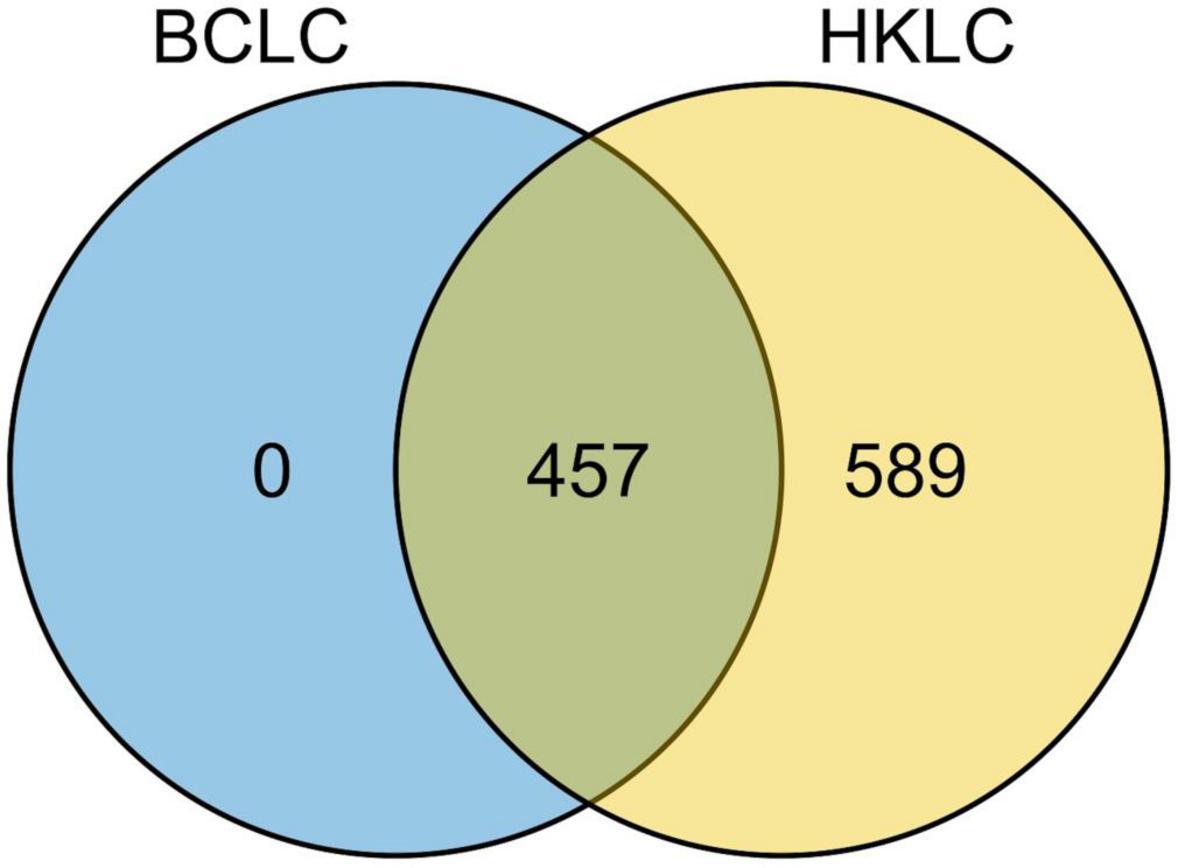

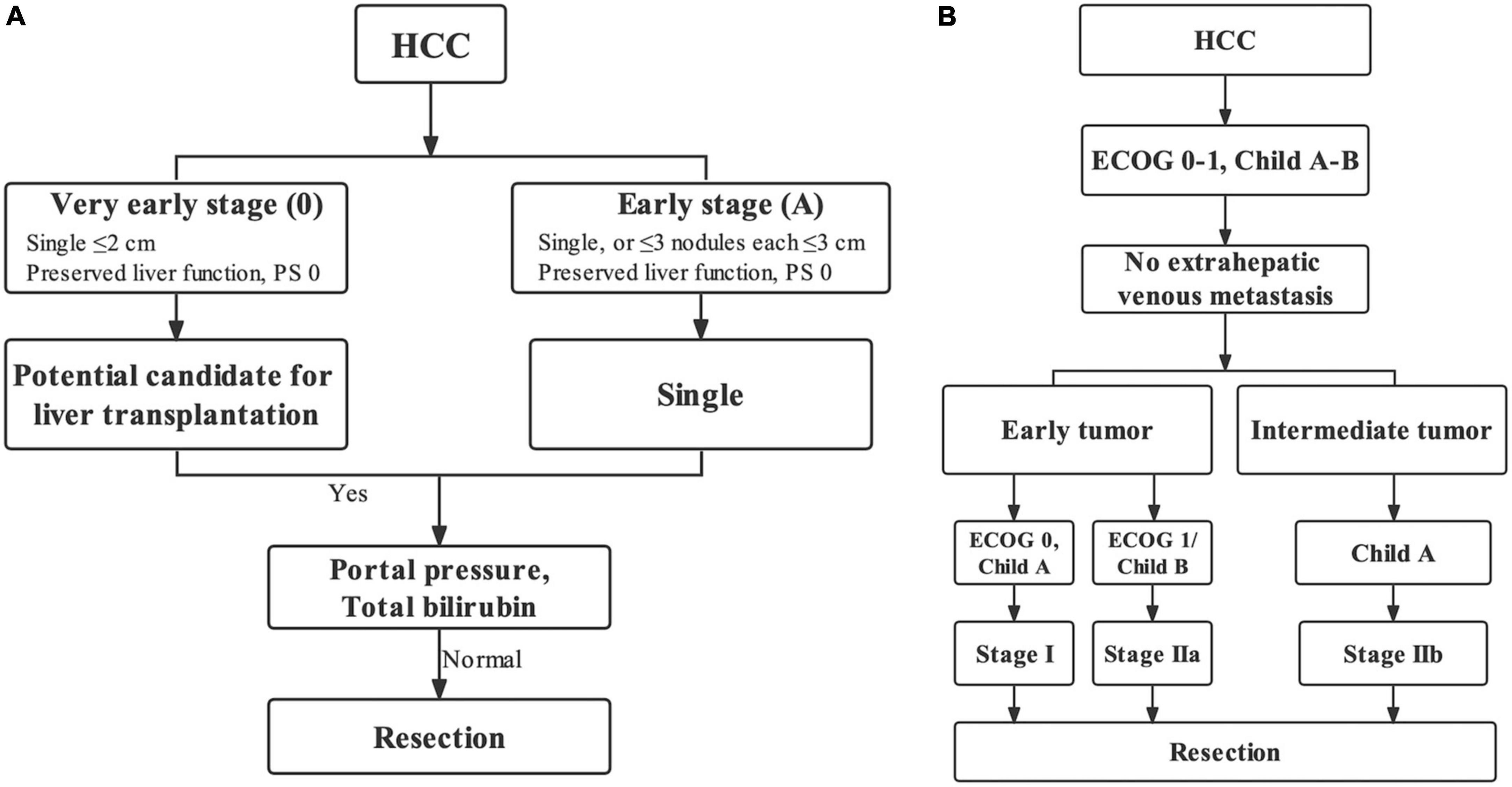

Overall, 457 (35.3%, 457/1,296) and 1,046 (80.7%, 1,046/1,296) patients were IPLR according to the 2022 version of the BCLC and HKLC staging systems, respectively. The patient selection flowchart is shown in Figure 1. The definitions of IPLRs in the BCLC and HKLC staging systems are illustrated in Figure 2. The median follow-up duration of the entire study population was 22.8 months (IQR: 10.0–41.0 months). By the end of the last follow-up, telephone interviews were successfully performed for 1,075 patients (82.9%, 1,075/1,296), and 464 patients died (35.8%, 464/1,296). The median OS in the entire study population was 60.6 months (95% CI: 51.7–69.5), and the 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-year OS rates were 81.9, 70.4, 61.9, 55.8, and 49.9%, respectively. The baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2. Ideal patients for liver resection (IPLR) in the BCLC staging system (A) and HKLC staging system (B).

Comparison of overall survival between ideal patients for liver resections in the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system and those in the Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging system

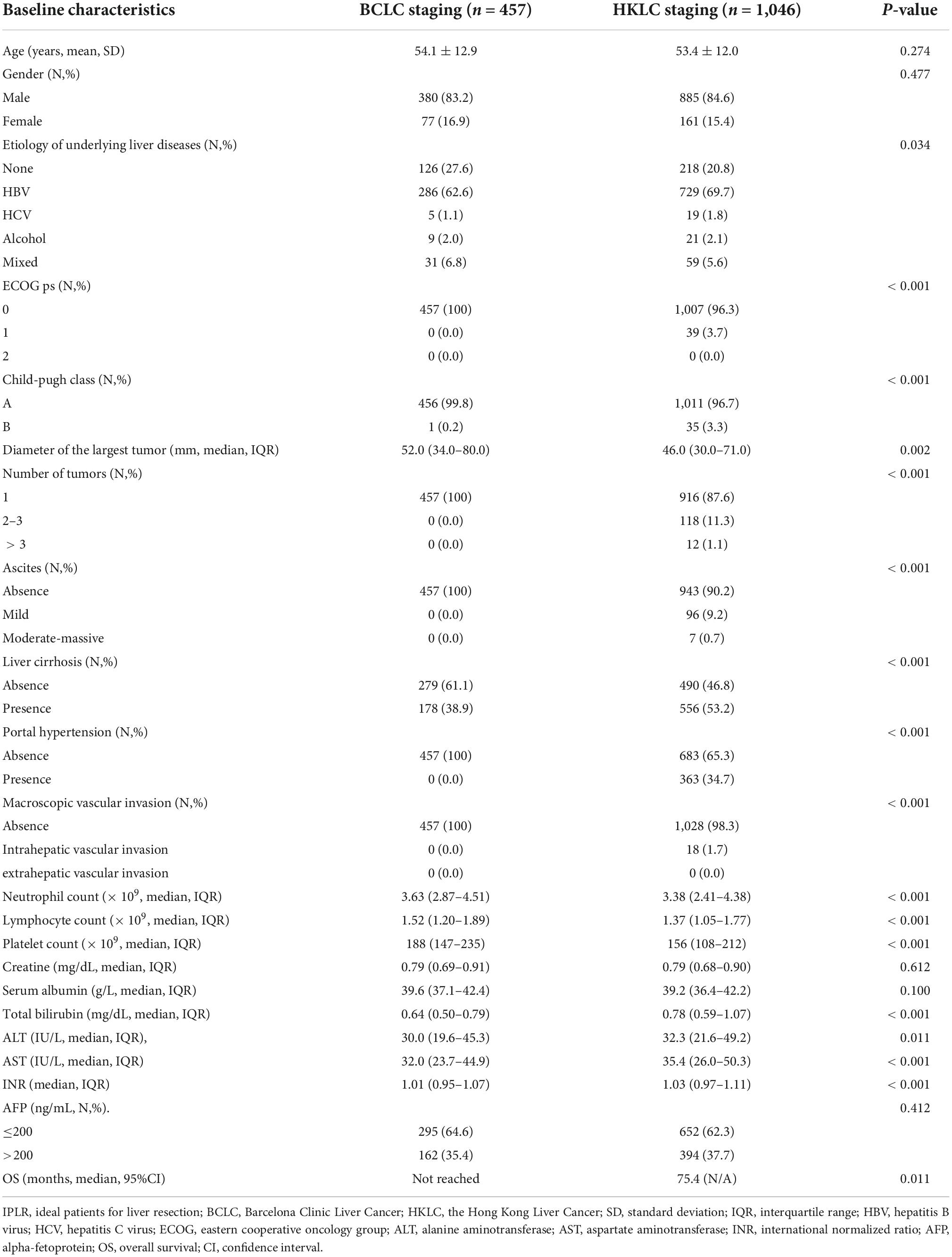

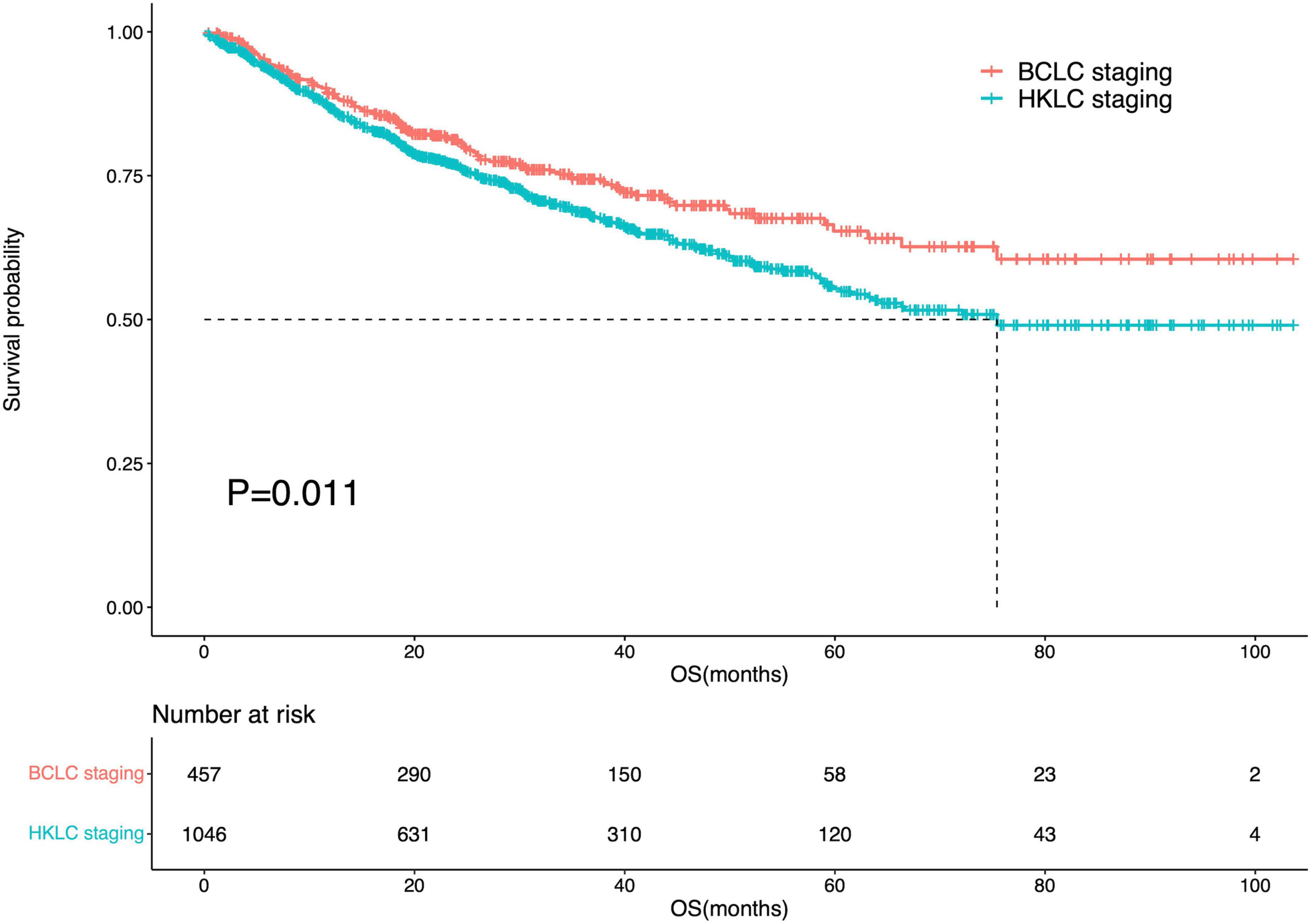

Among IPLRs in the BCLC staging system, 31 patients had BCLC-0 and 426 patients had BCLC-A disease. Moreover, among IPLRs in the HKLC staging system, 507, 429, and 110 patients had stage I, stage IIa, and stage IIb disease, respectively. The 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-year OS rates of IPLRs in the BCLC staging system were 89.0, 81.0, 73.9, 69.1, and 64.1%, respectively. The corresponding percentiles for IPLRs within the HKLC staging were 86.7, 76.7, 68.4, 61.7, and 54.9%, respectively. The median OS was not reached for IPLRs in the BCLC staging system and was 75.4 months (95% CI: N/A) for IPLRs in the HKLC staging system, with a significant difference (P = 0.011, Figure 3). The baseline characteristics of IPLRs in the BCLC and HKLC staging systems are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 3. Survival curve of the IPLRs in the BCLC staging system and those in the HKLC staging system.

Comparison of overall survival between ideal patients for liver resections in the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system and those in the Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging but beyond the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system

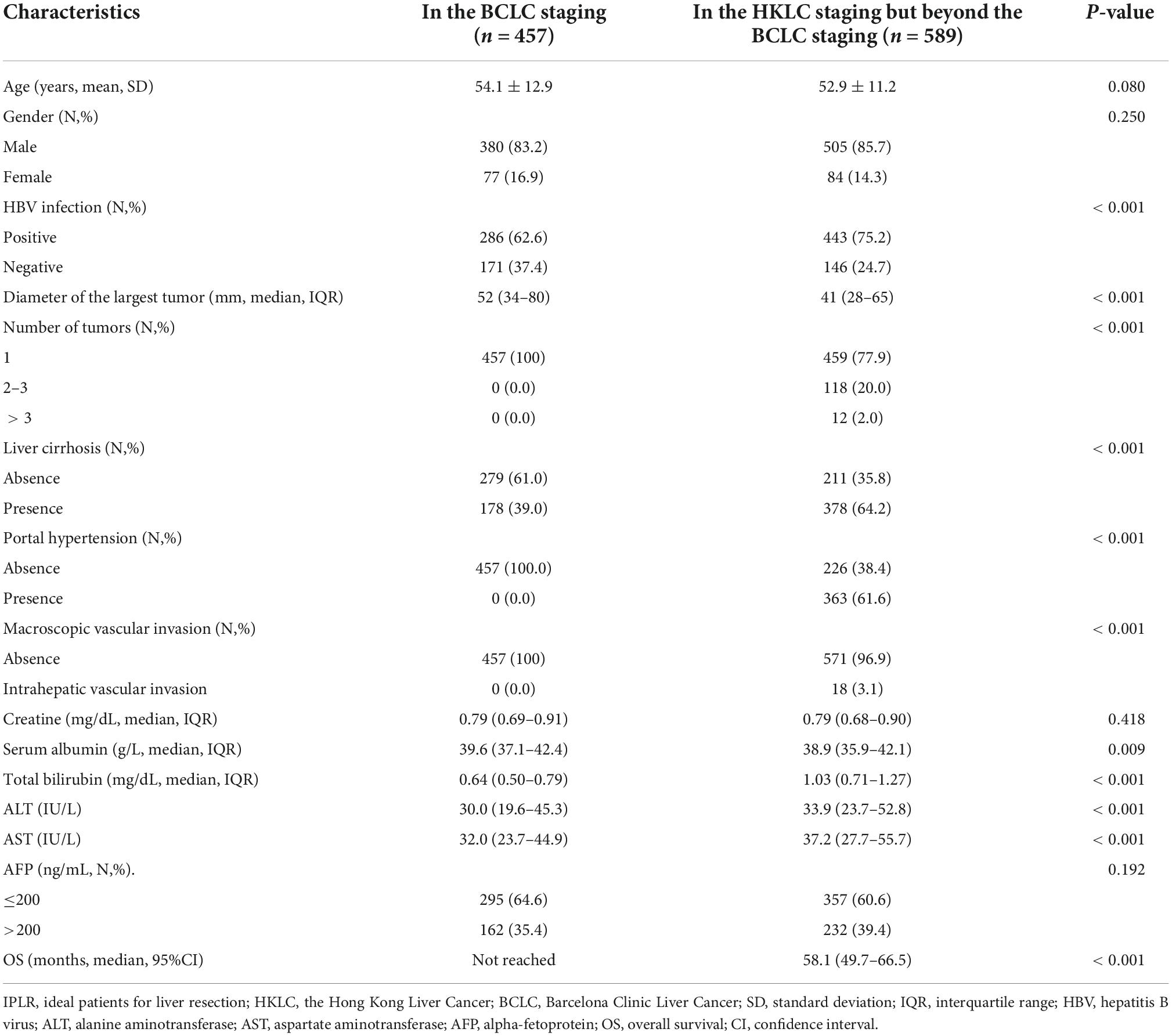

All the 457 IPLRs in the BCLC staging system were also IPLRs in the HKLC staging system, and the remaining 589 patients were IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system (Figure 4). Compared with IPLRs in the BCLC staging system, those in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system had a higher percentile of HBV infection (P < 0.001); smaller tumor size (P < 0.001); more tumors (P < 0.001); higher frequencies of liver cirrhosis (P < 0.001), portal venous hypertension (P < 0.001), and macroscopic vascular invasion (P < 0.001); lower albumin level (P = 0.009); higher total bilirubin (P < 0.001), ALT (P < 0.001), and AST (P < 0.001) levels. The baseline characteristics of the patients in the two groups are compared in Table 3.

Table 3. Baseline characteristics between IPLRs in the BCLC staging and IPLRs in the HKLC staging but beyond the BCLC staging.

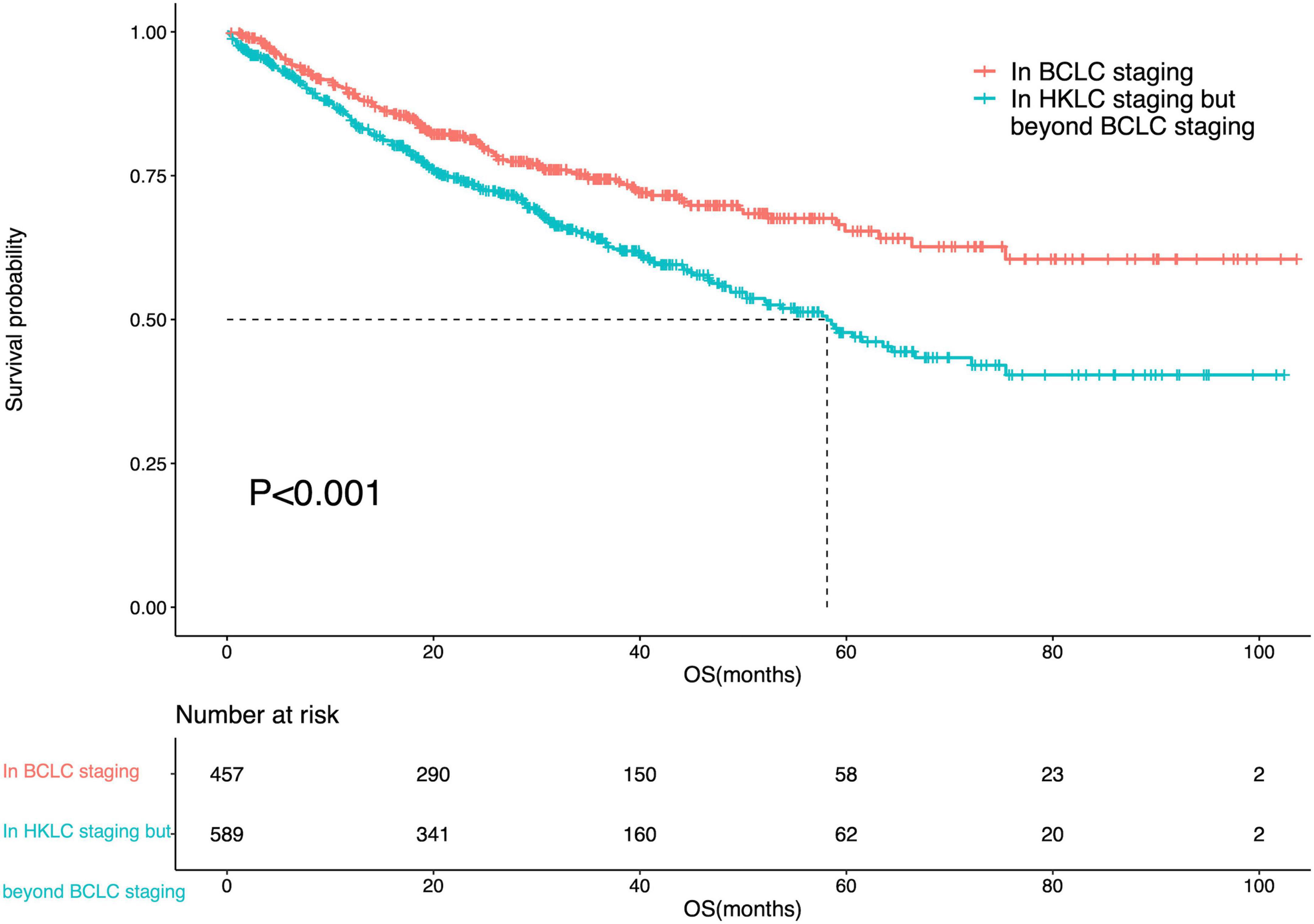

The median OS of IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system was 58.1 months (95% CI: 49.7–66.5). There was a significant difference in OS between patients in the BCLC staging and those in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system (P < 0.001) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Survival curve of the IPLRs in the BCLC staging system and those in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system.

Risk factors of poor prognosis of ideal patients for liver resections in the Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging system but beyond the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system

In the univariate analysis, age (P = 0.020), diameter of the largest tumor (P = 0.002), liver cirrhosis (P = 0.005), serum albumin (P = 0.028), and AST (P = 0.004) were influencing factors of prognosis. Therefore, these five parameters were included in the multivariate Cox regression analysis. The results showed that the diameter of the largest tumor > 5 cm (HR = 1.58; 95% CI: 1.18–2.10; P = 0.002) and presence of liver cirrhosis (HR = 1.61; 95% CI: 1.19–2.20; P = 0.002) were risk factors for poor prognosis in IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system. The results of the univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analysis with risk factors of poor prognosis of IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system (n = 589).

The diameter of the largest tumor had a beta coefficient of 0.454, while liver cirrhosis had a beta coefficient of 0.479. As these two parameters had similar beta coefficients in the multivariate Cox regression analysis, patients were assigned one point when they had a tumor > 5 cm or liver cirrhosis. Therefore, the minimum total point was 0, while the maximum total point was 2. The 104 patients with a total score of 0 were classified into the low-risk group; 369 patients with a total point of 1, intermediate-risk group; and 116 patients with a total score of 2, high-risk group. There was a significant difference in OS among patients in the BCLC staging systems and low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk groups (P < 0.001). Meanwhile, there was no difference in OS between patients in the BCLC staging system and those in the low-risk group (P = 0.996). However, differences in OS were noted between patients in the BCLC staging system and those in the intermediate-risk (P = 0.003) and high-risk (P < 0.001) groups. The survival curves are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Survival curves of the IPLRs in the BCLC staging system and those in the low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups.

Discussion

The BCLC staging system is a most popular treatment algorithm in Western countries while the HKLC staging is widely accepted in Eastern countries (14–16), and both two staging systems have their own definitions for IPLR. The 2022 version of the BCLC staging system defines IPLRs as patients with ECOG-PS score of 0, preserved liver function, single tumor regardless of size, absence of macroscopic vascular invasion and extrahepatic metastasis, and normal total bilirubin level and portal venous pressure (8). Meanwhile, in the HKLC staging system, IPLRs are defined as patients with an ECOG-PS score of 0–1, preserved liver function, absence of extrahepatic vascular invasion/metastasis, early tumor burden (≤ 5 cm, ≤ 3 tumor nodules, and absence of intrahepatic venous invasion), or intermediate tumor burden (≤ 5 cm, > 3 tumor nodules/with intrahepatic venous invasion or > 5 cm, ≤ 3 tumor nodules, and no intrahepatic venous invasion) (9). As described, the definition of IPLRs in the HKLC staging system is more aggressive than that in the BCLC staging system. In the present study, only 35.3% of patients in the entire study population were IPLRs according to the BCLC staging system, whereas the percentage was higher at 80.7% according to the HKLC staging system.

The prognostic predictive performance for OS in the BCLC staging system compared with that in the HKLC staging system has been widely investigated. A cohort study by Li et al. demonstrated that the BCLC staging system is better than the HKLC staging system in predicting survival and allocating patients to curative treatment (10). Kolly et al. also showed that the BCLC staging system offered a more accurate survival prediction than the HKLC staging system in the European population (11). However, studies by Yan et al. and de Freitas et al. showed that the HKLC staging system was more suitable for predicting prognosis in selected cases (12, 13). Apparently, it is still controversial whether one staging system is superior to the other. In the present study, IPLRs in the BCLC staging system had a better prognosis than those in the HKLC staging system (P = 0.011).

In the current study, all IPLRs in the BCLC staging system were also IPLRs in the HKLC staging system, as such, IPLRs in the HKLC staging system were divided into two groups, one is IPLRs in the BCLC staging system and the other is the IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system. The results showed that the IPLRs in the BCLC staging system had a better survival than those in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system (P < 0.001), hence, the definition of IPLR in the HKLC staging but beyond the BCLC staging system should be carefully reconsidered. Not surprisingly, IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system had higher percentile of HBV infection (P < 0.001); more tumors (P < 0.001); higher frequencies of liver cirrhosis (P < 0.001), portal venous hypertension (P < 0.001), and macroscopic vascular invasion (P < 0.001); lower albumin level (P = 0.009); higher total bilirubin (P < 0.001), ALT (P < 0.001), and AST (P < 0.001) levels than those in the BCLC staging system. However, interestingly, the diameter of the largest tumor is smaller in the IPLRs in the HKLC staging but beyond the BCLC staging than those in the BCLC staging. The possible explanation for this discrepancy is mainly owing to the different definitions of IPLR between these two staging systems. The tumor size is not a key element to define the IPLR in the BCLC staging system, while tumor size ≤ 5 cm is a main factor to define the IPLR in the HKLC staging system.

Although, prognosis of IPLRs in the BCLC staging system is better than that of IPLRs in the HKLC staging system as well as that of IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system, the BCLC staging system is too conservative to define the IPLR and thus may exclude patients who may potentially benefit from LR. In the last decades, better patient selection and improved surgical techniques have enabled the indications for LR to be expanded. Therefore, it is essential to identify IPLRs beyond the BCLC staging system who may really benefit from LR. In the present study, univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses showed that the diameter of the largest tumor being > 5 cm (HR = 1.58; 95% CI: 1.18–2.10; P = 0.002) and the presence of liver cirrhosis (HR = 1.61; 95% CI: 1.19–2.20; P = 0.002) were risk factors for poor prognosis in IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system. Tumor size is a tumor burden-related parameter that is highly associated with the prognosis of HCC (17, 18). Liver cirrhosis is an underlying liver disease-related parameter that is widely accepted as a significant prognostic factor for survival because most HCCs derive from the background of underlying liver diseases (19, 20). These two risk factors were used to identify the population who may benefit from LR in IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system. The results demonstrated that among IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system, those whose largest tumor size is smaller than 5 cm and without concurrent liver cirrhosis might have comparable survival to IPLRs in the BCLC staging. This result indicates that LR can be performed in selected cases in this population.

This study had some limitations. First, the retrospective nature of the study may have led to several selection biases. Second, with approximately 70% of patients having evidence of HBV infection, our data require validation from other study groups in whom HCV infection or alcohol consumption is the prevailing etiology of chronic liver disease. Third, we only validated the performance of the two systems in patients who underwent LR. The accuracy for other treatments according to the HKLC and BCLC staging systems remains unclear. In addition, there was a lack of patients treated with liver transplantation and ablation in our cohort, which may not account for this aspect of HKLC and BCLC staging and treatment recommendations. Future studies should include more patients such as those who underwent liver transplantation and ablation to validate our findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, IPLRs in the BCLC staging system have better prognosis than those in the HKLC staging system and those in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system. This indicates that the BCLC staging system is better in identifying IPLR. However, among IPLRs in the HKLC staging system but beyond the BCLC staging system, patients with the largest tumor size measuring < 5 cm and without liver cirrhosis may obtain comparable survival benefit from LR to IPLRs in the BCLC staging system.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

J-XL and PZ wrote the manuscript. J-XL, PZ, W-WC, and YB provided the patients’ information. YT and YB reviewed the patients’ clinical data. D-HC, SZ, Y-DX, and W-WC edited the manuscript. W-WC revised the manuscript. Y-DX, W-WC, and SZ were the main contributors of the study design and concept. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

1. Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2021) 7:6. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3

2. European Assoc Study Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. (2018) 69:182–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019

3. Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, Sirlin CB, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. (2018) 67:358–80. doi: 10.1002/hep.29086

4. Allaire M, Goumard C, Lim C, Le Cleach A, Wagner M, Scatton O. New frontiers in liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. JHEP Rep. (2020) 2:100134. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100134

5. Hu B, Yang XR, Xu Y, Sun YF, Sun C, Guo W, et al. Systemic immune-inflammation index predicts prognosis of patients after curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. (2014) 20:6212–22. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0442

6. Wang Q, Xia D, Bai W, Wang E, Sun J, Huang M, et al. Development of a prognostic score for recommended TACE candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre observational study. J Hepatol. (2019) 70:893–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.01.013

7. Farinati F, Vitale A, Spolverato G, Pawlik TM, Huo TL, Lee YH, et al. Development and validation of a new prognostic system for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS Med. (2016) 13:e1002006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002006

8. Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Burrel M, Garcia-Criado Á, et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: the 2022 update. J Hepatol. (2022) 76:681–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.018

9. Yau T, Tang VYF, Yao TJ, Fan ST, Lo CM, Poon RTP. Development of Hong Kong liver cancer staging system with treatment stratification for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. (2014) 146:1691–700. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.032

10. Li JW, Goh BBG, Chang PE, Tan CK. Barcelona Clinic liver cancer outperforms Hong Kong liver cancer staging of hepatocellular carcinoma in multiethnic Asians: real-world perspective. World J Gastroenterol. (2017) 23:4054–63. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i22.4054

11. Kolly P, Reeves H, Sangro B, Knopfli M, Candinas D, Dufour JF. Assessment of the Hong Kong liver cancer staging systemin Europe. Liver Int. (2016) 36:911–7. doi: 10.1111/liv.13045

12. Yan XP, Fu X, Cai C, Zi XJ, Yao H, Qiu YD. Validation of models in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of Hong Kong liver cancer with barcelona clinic liver cancer staging system in a Chinese cohort. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2015) 27:1180–6. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000418

13. de Freitas LBR, Longo L, Santos D, Grivicich I, Alvares-da-Silva MR. Hepatocellular carcinoma staging systems: Hong Kong liver cancer vs Barcelona clinic liver cancer in a Western population. World J Hepatol. (2019) 11:678–88. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i9.689

14. Kobayashi S, Fukushima T, Ueno M, Moriya S, Chuma M, Numata K, et al. A prospective observational cohort study of lenvatinib as initial treatment in patients with BCLC-defined stage B hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. (2022) 22:517. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09625-x

15. Zu QQ, Schenning RC, Jahangiri Y, Tomozawa Y, Kolbeck KJ, Kaufman JA, et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for BCLC stage C hepatocellular carcinoma comparing child-Pugh A versus B7 patients: are the outcomes equivalent? Cardiolvasc Intervent Radiol. (2020) 43:721–31. doi: 10.1007/s00270-020-02434-4

16. Kim KM, Sinn DH, Jung SH, Gwak GY, Paik YH, Choi MS, et al. The recommended treatment algorithms of the BCLC and HKLC staging systems: does following these always improve survival rates for HCC patients? Liver Int. (2016) 36:1490–7. doi: 10.1111/liv.13107

17. Müller L, Hahn F, Auer TA, Fehrenbach U, Gebauer B, Haubold J, et al. Tumor burden in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization: head-to-head comparison of current scoring systems. Front Oncol. (2022) 12:850454. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.850454

18. Ho SY, Liu PH, Hsu CY, Huang YH, Liao JI, Su CW, et al. A new tumor burden score and albumin-bilirubin grade-based prognostic model for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers. (2022) 14:649. doi: 10.3390/cancers14030649

19. Lim J, Chon YE, Kim MN, Lee JH, Hwang SG, Lee HC, et al. Cirrhosis, age, and liver stiffness-based models predict hepatocellular carcinoma in Asian patients with chronic hepatitis B. Cancers. (2021) 13:5609. doi: 10.3390/cancers13225609

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, liver resection, ideal patients, prognosis, comparison

Citation: Li J-X, Zhou P, Chang D-H, Tong Y, Bao Y, Xiao Y-D, Zhou S and Cai W-W (2022) Ideal patients for liver resection in Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer or Hong Kong Liver clinic systems for hepatocellular carcinoma: Conservative or aggressive? Front. Med. 9:977135. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.977135

Received: 24 June 2022; Accepted: 21 September 2022;

Published: 14 October 2022.

Edited by:

Alfred Wei Chieh Kow, National University of Singapore, SingaporeReviewed by:

Alessio Gerussi, University of Milano-Bicocca, ItalyMatteo Donadon, Università Degli Studi del Piemonte Orientale, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Li, Zhou, Chang, Tong, Bao, Xiao, Zhou and Cai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shi Zhou, emhvdXNoaUBnbWMuZWR1LmNu; Wen-Wu Cai, Y2Fpd2Vud3UxOTg2QGNzdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Jun-Xiang Li1†

Jun-Xiang Li1† Yao Tong

Yao Tong Yu-Dong Xiao

Yu-Dong Xiao