94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Med., 29 August 2022

Sec. Dermatology

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.967971

This article is part of the Research TopicCutaneous Manifestations of Systemic DiseaseView all 8 articles

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) is a genetic condition which leads to a loss of inhibition of cellular growth. Facial angiofibromas (FAs) are hamartomatous growths associated with TSC that appear as multiple small, erythematous papules on the skin of the face and may resemble more severe forms of acne vulgaris. FAs have been reported in up to 74.5% of pediatric TSC patients, rising to up to 88% in adults >30 years old. They have not been closely studied, potentially overshadowed by other, systemic features of TSC. To investigate the impact of FAs, a common clinical feature for patients with TSC, we performed a non-interventional study in the form of a survey, completed by people living with TSC and FAs, or their caregiver as a proxy, if necessary. Patients were recruited via patient organizations in the UK and Germany. Data was received from 108 families in the UK (44 patients, 64 caregivers) and 127 families in Germany (50 patients, 64 caregivers). Exclusion criteria were those outside of 6-89 years, those without FAs, or those enrolled in a clinical trial. Where caregivers reported on behalf of an individual unable to consent, they were required to be adults (>18 years). Patient experience in the design of the survey was considered from practical and logistical perspectives with survey questions assessing multiple aspects relating to FAs including age of onset, perceived severity, treatments, perceived efficacy of treatments and perceived psychosocial impacts of the FAs. The psychosocial impacts of FAs for the individuals as well as for caregivers were explored in terms of social, occupational and leisure activities. Results of the survey demonstrated that for those with TSC-related moderate or severe FAs, there is an impact on quality of life and psychosocial impacts in the form of anxiety and depression. This finding was also noted by caregivers of TSC individuals in these categories. The treatment most frequently received to improve FAs, topical rapamycin/sirolimus, was found to be successful in the majority of those who received it.

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) is a rare, autosomal dominant genetic condition relating to mutations in either TSC1 or TSC2, which code for hamartin and tuberin proteins, respectively, leading to constitutive activation of the mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 (mTORC1) and consequently a heterogenic loss of inhibition of cellular growth. This loss of inhibition of cellular growth leads to the development of benign tumors in the brain and other vital organs, such as the kidneys, heart, liver, eyes, lungs and skin (1). The central nervous system is typically involved, which may result in associated neuropsychiatric disorders such as cognitive impairment, autism, and other behavioral disorders—known as ‘TSC-Associated Neuropsychiatric Disorders' (TAND), in addition to other neurological symptoms, such as seizures (2).

Functionally, the proteins hamartin and tuberin form a complex which regulates cellular growth, therefore loss of function mutations lead to dysregulated growth. TSC2 mutations account for the majority of TSC cases and are associated with more severe symptoms (3). Disease prevalence is estimated to be 7–12 in 100,000 (4).

While TSC is a highly variable condition with inter-patient variability in signs, symptoms, and severity, skin abnormalities are common. Facial angiofibromas (FAs) are thought to occur in up to 88% of TSC patients (5, 6). These lesions, composed of blood vessels and fibrous tissue, have previously been reported to typically appear after the age of 5 years, often preceded by facial flushing (5).They are considered one of the key diagnostic criteria for TSC (7).

The facial appearance resulting from FA lesions is associated with high psychological and physical morbidity (for example, recurrent bleeding or nasal obstruction) (8), as such it may be considered alongside acne vulgaris, port wine stains, atopic dermatitis, congenital melanocytic nevi and other conditions as a psychodermatological condition (9) with both physical and psychosocial impacts. The onset of facial dermatological conditions during school-age and adolescence has been found to cause a particularly negative psychsocial impact at a time when peer relationships gain importance and self-concept matures (10). Such is the impact of psychodermatological conditions upon patients' self-esteem that asking patients or their caregivers to rate the satisfaction with their skin on a scale from 1 to 10 has been suggested (11).

Traditionally, treatment options have focused on removal, such as surgical or laser procedures. According to the “Updated TSC International Diagnostic Criteria and Surveillance and Management Recommendations” (7), intervention with mTOR inhibitors (mTORis), pulsed dye or ablative lasers, or surgical excision can be appropriate for lesions that are large, disfiguring, prone to bleeding, or painful. Less invasive topical treatment with mTORis (rapamycin/sirolimus gels) has been advocated and its safety and efficacy for this purpose has been demonstrated in clinical trials (12, 13).

Jansen and colleagues (14) reported a substantial burden of TSC on the personal lives of individuals with TSC and their families. Nearly half of the patients experienced negative progress in their education or career due to TSC; additionally, many of their caregivers were unemployed resulting from the time commitment associated with the care they provided. Most caregivers indicated that TSC affected family life, and social and working relationships. Furthermore, well-coordinated care was considered difficult to access, and patients experienced moderate rates of pain or discomfort as well as anxiety or depression (14).

TSC patients may be challenged across multiple body systems as a result of having multiple organ hamartomas. Such effects can present challenges for the patients themselves as well as their caregivers. There are some studies which have explored the quality of life and the burden of TSC related illness reported by patients and their caregivers (15). However, there is very little reported relating to the severity and psychosocial impacts of TSC-associated FAs in particular, for the affected individuals and their caregivers which this study aimed to establish.

This was a non-interventional, observational study consisting of a cross-sectional online survey with 17 questions (see Table 1).

People living with FAs were recruited through invitations distributed via Patient Organizations (POs) in monthly TSC newsletters, targeted mailing lists, and social media channels in the UK (Tuberous Sclerosis Association—www.Tuberous-Sclerosis.org) and Germany (Tuberöse Sklerose Deutschland e.V.—www.TSDEV.org). The invitations described a voluntary, unpaid, structured online survey of approximately 15 minutes in duration. Data subjects accessed the survey via an English language or a German language link distributed by the respective POs.

The survey materials were originally developed in English and then translated into German, and certified by an accredited translation agency. While external pilot testing of the survey with patients was not performed, internal quality checks ensured functionality and the survey was reviewed by members of UK and German POs.

The Survey included demographics and a series of questions evaluating the impact of FAs on quality of life (see Table 1). It was accessible for over 4 months (September to October 2021). There was no follow-up.

Inclusion criteria were:

• Person or caregiver of a person with a diagnosis of TSC.

• Aged 6–89 years.

• If a young adult: capacity to consent to a study (per national regulations for each country).

• If a caregiver was responding on behalf of a young subject (<18 years) the caregiver needed to be an adult (>18 years).

The exclusion criterion was being concurrently enrolled in another clinical trial.

All data subjects provided informed consent prior to completing the survey and were informed of their rights under General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) as well as national, regional and local laws pertaining to privacy and data protection. Data subjects were informed that the survey was sponsored (Plusultra pharma).

The study was performed in compliance with the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association (16) and was approved by the ethics committee of the Western Institutional Review Board (Tracking number: 20214481). Patients remained anonymised with de-identified patient information collated and aggregated. The survey consisted of eligibility screening questions followed by survey questions for eligible subjects. The screening questions verified that: there had been a confirmed diagnosis of TSC; the person completing the survey was either a patient or caregiver; the patient's age was within the stated criteria (and if 13–17 years old, considered suitable to participate); and that the caregiver's age was within the stated criteria.

The survey was accessed by 762 (UK = 331, Germany = 431, see Figure 1). There were 24 screen failures (UK = 9, Germany = 15). Screen failures were predominantly due to the survey being attempted by a non-patient or non-caregiver (n = 12, UK = 6, Germany = 6). This reason was followed by a lack of confirmed TSC diagnosis (n = 7, UK = 2, Germany = 5). Finally, some caregivers (n = 4, UK = 1, Germany = 3) cited their age as <18 years while another respondent declined consent (Germany = 1).

After five screening questions, 503 data subjects did not complete the survey to at least question 14 (UK = 214, Germany = 289); approximately twice as many as those who did (n = 235). Most survey drop-outs (n = 489; 97%) did so in the first five questions after screening, which assessed sample characteristics (see Table 1). The reason for not completing the survey is not known.

The survey was completed to at least question 14 by 235 eligible subjects (UK = 108, Germany = 127). A total of 94 patients (UK = 44, Germany = 50) and 141 caregivers (UK = 64, Germany = 77) were included. The age of the patients with TSC ranged from 6 years (per eligibility criteria) up to 70 years. The mean age was 30 years (UK = 31, Germany = 29) with a standard deviation of 15 years (UK = 16, Germany = 14). Approximately a quarter (23%) were pediatric (55/235 aged 6–17 years) and thus this group contributed either via proxy if <13 years or directly if aged 13–17 and considered suitable to complete the survey independently.

The subjects deemed eligible for analysis included 11 data subjects (2 patients, 9 caregivers) who had not completed the full survey (up to and including Q17) but had completed a sufficient majority of questions (up to and including Q14). These 11 subjects were included for analysis of their completed questions, with the variable sample size being reported for each analysis (see Figure 1).

Descriptive analyses were conducted in IBM® SPSS® Data Collection Survey Reporter v7.5 software. The descriptive statistics varied according to the type of data being described. Categorical data was analyzed for base size, frequencies and percentages. Continuous data was reported as base size, mean and median averages, standard deviations, interquartile ranges, minimum and maximum values and 95% confidence intervals.

Results for patients with TSC living with FAs will be reported as “data subjects;” combining patient and caregiver/proxy responses. In reference to treatment, all responses are in relation to the affected individual with TSC aside for Q16–17 which were directed toward caregivers (see Tables 6, 7). Between the UK and Germany, similar proportions of data subjects were patients; 41% for the UK (44/108), 39% for Germany (50/127).

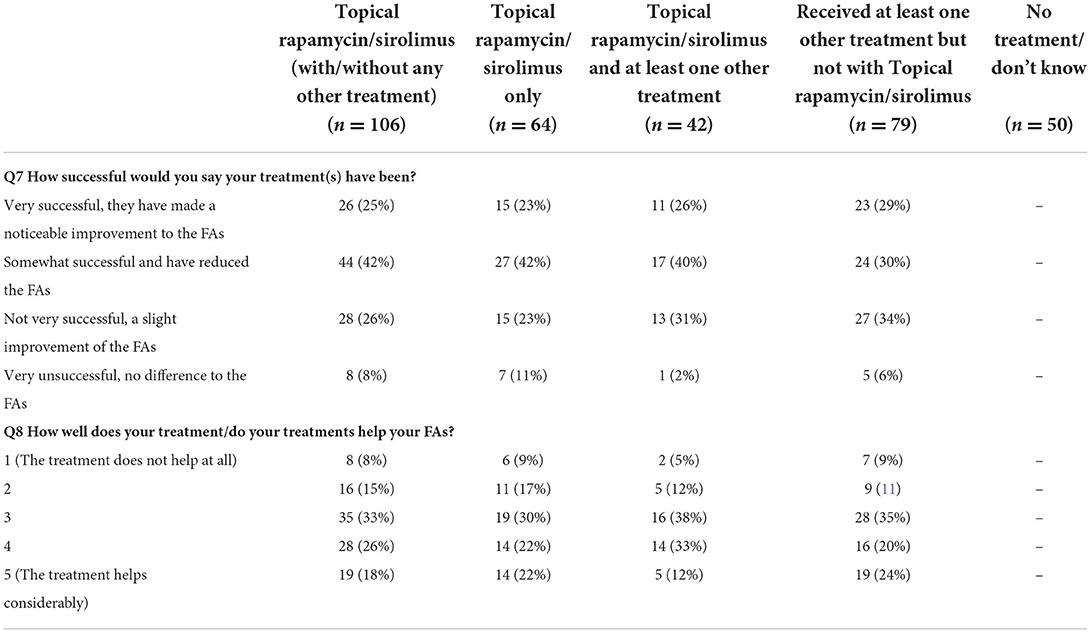

Questions relating to the study population's characteristics (see Table 1) identified that the three most common specialists or clinics attended were comparable between the UK and Germany. Combined, they were: Dermatologist (48%), a TSC clinic (41%) and neurologist (29%), with 48% visiting a TSC clinic at least annually. The reported severity of TSC-associated FAs was comparable between the two countries; 51% (CI: 41.7,60.2) reporting moderate FAs, 30% (CI: 19.7, 42.0) reporting mild FAs and 16% (CI: 6.2, 31.5) reporting severe FAs, with a small minority (~3%) undecided. The most common age for FAs to appear was 3–5 years old (37%), followed by 6–10 years old (23%). More common than other treatments, data subjects (45%) reported treatment for FAs with topical rapamycin/sirolimus (whether alone or in combination with other treatments). This was followed by laser ablation (34%). Of those treated with topical rapamycin/sirolimus, 67% (CI: 57.2, 75.8) found the treatment “very” or “somewhat successful” (see Table 2). This was higher than for those who had not received topical rapamycin/sirolimus where 59% reported successful/somewhat successful response to treatment.

Table 2. Treatment success for people who had received topical rapamycin/sirolimus with and without other common treatment options for Fas.

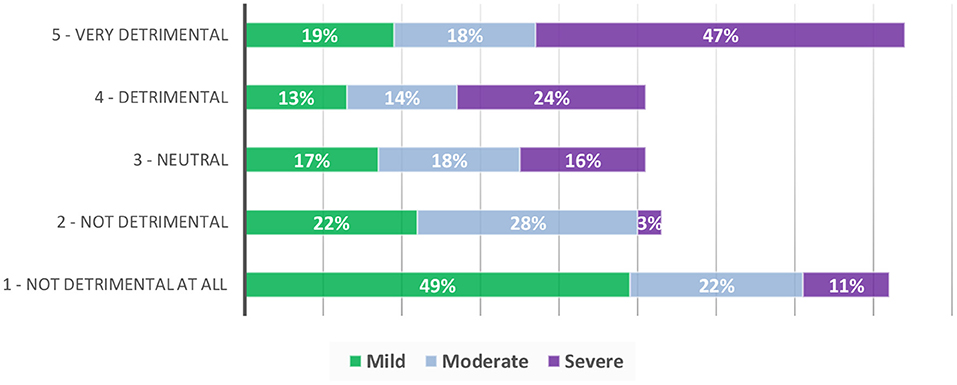

A greater proportion responded that FAs were detrimental to their overall quality of life, especially when they felt their FA treatment had been less or not at all successful [29% (CI: 18.6, 41.3) vs. 18% (CI: 11.5–26.2, see Table 3)]. Nearly half of data subjects who reported severe FAs (n = 38) reported that they had a detrimental impact on their quality of life (47%) (see Figure 2).

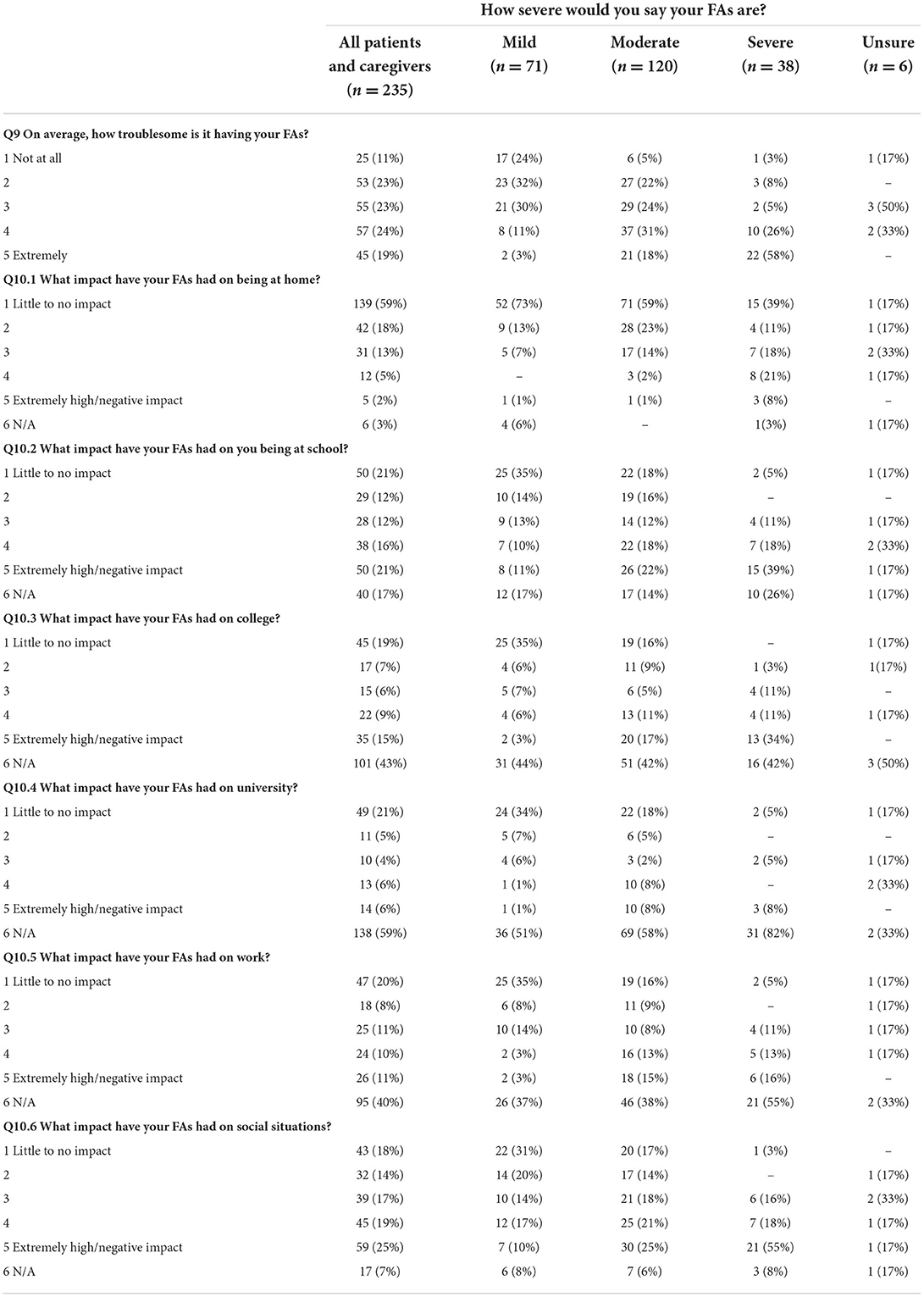

Table 3. Reported difficulty of having FAs and impact on everyday situations in each severity group.

Figure 2. Perceived Impact of FAs on quality of life in data subjects with mild, moderate and severe FAs.

Impact of FAs in general and in specific contexts: at home, work, places of education and in social situations was assessed (see Table 4; Figure 2). Across the whole sample, 43% (CI: 36.6, 49.6) of data subjects rated their FAs as being at least somewhat troublesome (4 or 5 on the scale), associated with increased severity. Of the 16% of data subjects who reported severe FAs, 84% (CI: 68.5, 93.8) reported them as being very to extremely troublesome.

Over half of data subjects (59%, CI: 52.4, 65.4) reported that their FAs had little impact at home (see Table 3), however there was a trend toward increased impact in the presence of increased FA severity. While 73% (CI: 61.2, 82.9) of those with mild FAs reported no impact at home, only 39% (CI: 23.6, 56.2) with severe FAs reported no impact in this setting with nearly a fifth [21% (CI: 9.5, 37.3)] reporting an extremely high/very negative impact in this setting. The greatest negative impact was in response to social situations (see Table 3) with 44% of all subjects reporting a high or extremely high impact, this was followed by school (37% of data subjects reporting a high or extremely high impact); university (27% of data subjects reporting a high or extremely high impact); college (with 24% of data subjects reporting a high or extremely high impact) and work (with 21%) of data subjects reporting a high or extremely high impact. The effect of having FAs on social situations was extremely marked for those with severe FAs with 73% (CI: 56.2, 86.1) of data subjects with severe FAs reported a high or/extremely high negative impact on social situations (see Table 3).

The psychosocial impact of FAs and impact on quality of life was assessed (see Table 4). Similar to other categories, the psychosocial impacts of FAs appear to increase with increased severity. While the majority of data subjects with FAs (mild to severe) reported that their FAs had little to no impact on socializing (61%), making new friends (69%), finding/doing a favorite hobby (78%), style choices (77%) or impact on holidays (67%) this was not the case among the subgroup of those reporting severe FAs. In this group; 69% (CI: 52.0, 83.0) reported feeling embarrassed by them, as well as self-conscious (64%, CI: 46.8, 78.9) and reported receiving unkind comments (65%, CI: 47.9, 79.7) or unwanted attention (84%, CI: 68.5, 93.8).

Pain and discomfort from FAs were mostly reported in data subjects with severe FAs (see Table 4), with 66% (CI: 48.9, 80.5) reporting that their FAs feel uncomfortable/itchy and 45% (CI: 28.9, 62.0) reporting that their FAs were painful. The pattern of increased impact with increased FA severity also translated to the impact of FAs on overall quality of life, with 71% (CI: 54.0, 84.5) of those reporting severe FAs reporting that they are detrimental to their quality of life (Figure 2) compared to those with moderate (32%, CI: 23.8, 41.1) and mild FAs (12%, CI: 5.5, 21.9).

The impact of FAs on anxiety and depression was assessed (see Table 5). The frequency of data subjects reporting higher levels of anxiety (responding “rather much” or “very much” to Q14. “To what extent have you been feeling anxious during the last month?”) was highest in those with severe FAs (50%, CI: 33.4, 66.6), followed by those with moderate (31%, CI: 22.9, 40.1) and mild FAs (14%, CI: 6.9, 24.3). There was a similar association between increased feelings of depression and increased FA severity.

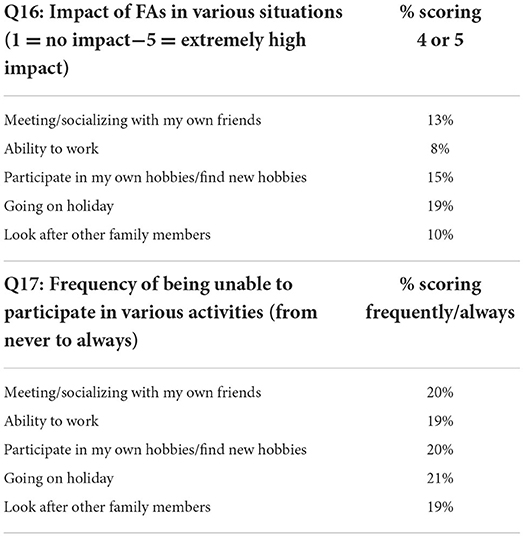

Caregivers completing the survey on behalf of the person with FAs were asked two further questions on how caring for that person impacted on their daily life (see Tables 6, 7). Most caregivers reported little impact on their own ability to work; find and participate in hobbies; go on holiday; or look after other family members (Q16). However, those caring for people with moderate and severe FAs reported higher levels of impact on socializing with 38% (CI: 28.5, 48.3) of the 100 caregivers of people with moderate or severe FAs having reported a high to extremely high impact on socializing.

Table 7. Percentage of caregivers reporting a high level of impact across the situations assessed in questions 16 and 17.

Some caregivers, particularly those who cared for people with severe FAs, reported not being able to do certain activities as frequently as they would like (see Tables 6, 7, Q17). Forty-five percent (CI: 26.9, 64.1) of those who cared for people with severe FAs reported not being able to participate in social activities as often as they would like for at least some of the time (having selected either “sometimes,” “frequently,” or “always”). Most responses highlighted the broad impact of FAs for carers in various situations, showing that in the region of a fifth reported experiencing a “high” or “extremely” negative impact in a range of situations and activities such as socializing, working, participating in hobbies, going on holiday and looking after other family members.

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in the UK and Germany with the aim of exploring the impact of living with FAs for those affected by TSC as well as for their caregivers and wider family. This survey supports previous evidence that FAs first appear at a young age of 3–5 years (6), younger than has been previously reported (5).

More participants with moderate and severe FAs reported a negative impact in their day-to-day lives, at work, places of education and in social situations in general, compared to those with mild FAs. Most participants with severe FAs reported negative impacts such as feeling embarrassed (69%), self-conscious (64%), receiving unkind comments (65%) or attracting unwanted attention (84%). In terms of physical impacts, 66% of those with severe FAs reported that they were uncomfortable/itchy and of these, nearly half reported they were painful. Seventy-one percent of those with severe FAs reported that they are detrimental to their quality of life (see Figure 2) compared to those with moderate (32%) and mild FAs (12%). Additionally, those who cared for TSC affected individuals with moderate and severe FAs reported greater negative impacts than those who cared for those with mild FAs.

Aside from those affected by severe FAs, the impact on quality of life was broadly reported by 36% of data subjects in the UK and 28% of data subjects in Germany, reflecting a common negative impact from this widely prevalent feature of TSC. The current findings demonstrate a substantial burden of TSC on the personal lives of individuals with TSC and their families (14) and the negative psychosocial and mental health impacts of living with FAs. While FAs are a common feature of TSC, this survey demonstrates that for the 16% of those who described having severe FAs, the negative impact cuts across a broad spectrum of daily life, in particular psychosocial categories. The high prevalence of reported negative experiences among affected by severe FAs (38/235 data subjects) is cause for concern.

The survey explored current treatment options and identified that the most common treatment, topical rapamycin/sirolimus, either alone or in combination, was reported to be of benefit to most participants, successfully treating and helping their FAs either somewhat or very successfully in 67% (Figure 3).

The survey received a limited number of completed responses with a combined total of 762 individuals accessing the survey, 24 failing to meet screening criteria and 503 individuals not completing the survey to at least question 14. In view of the large number of individuals believed to have a diagnosis of TSC, estimated to be between 3,700 and 11,000 in the UK alone, according to the UK Tuberous Sclerosis Association, further studies with a larger response rate from individuals with TSC or their caregivers would be needed to confirm this study's preliminary findings.

As with all self-completed surveys, only data from those people willing to participate were captured, therefore a bias of self-selected population reporting is expected. Among the data subjects, 40% were patients (94 patients and 141 caregivers contributed data, 235 in total) therefore a greater proportion were represented by proxy.

Data was self-reported (e.g., in responses to screening questions, grading of symptoms and impacts) and subjective with no validation of responses against clinical records. The survey did not assess the medical background of the TSC affected individuals, in particular the prevalence of TSC-associated Neuropsychiatric Disorders (TAND) of which includes anxiety and depressive disorders. The prevalence of these has previously been reported as: anxiety disorders (28%) and mood disorders (26%) in a survey of 241 children and adults with TSC (17). It is possible that TAND could influence responses relating to psychosocial aspects of the survey and equally, that the presence of mild to severe FAs may have a varying degree of impact for those affect by TAND.

FAs are a visible manifestation of TSC and may mimic severe forms of acne vulgaris, a condition which has well-described negative impacts on stress, interpersonal relations and daily life (18). FAs are present on the most socially engaged aspect of the body; the face, and incur negative psychosocial impacts (19). They may be considered an example of a psychodermatological condition. In this survey, we found the impact of FAs to be comparable to previous findings on the psychosocial impacts reported by those with acne vulgaris, namely that subjective ratings of severity of acne vulgaris are related to reported negative self-image, self-esteem, social relations and depression scores (18). Studies focussed on the psychosocial impacts of acne vulgaris suggest that the reported impacts are independent of objective measures, encouraging clinicians to focus on the subjective perception in managing the condition, irrespective of objective measures of severity (18).

The results from this survey quantify the perceived social and physical impacts of FAs as well as the perceived efficacy of their treatment options, as reported by affected patients or caregivers by proxy, in the UK and Germany. This is the first survey assessing the impact of FAs not only on the patient group but also on the working and social lives of their caregivers. The findings are notable for the high proportion of data subjects reporting a negative impact of FAs on affected individuals' day-to-day activities, leading to large numbers reporting a detrimental impact on their overall quality of life, particularly among those reporting severe FAs. For the caregivers, caring for someone with with FAs did not appear to hinder the ability of most participating carers to socialize, work, find and participate in hobbies, go on holiday and look after other family members. However, similar to the answers provided in the main survey, generally the frequency of no/low impact was higher in caregivers if the person they cared for had mild FAs, whereas those who cared for people with moderate and severe FAs reported more of an impact.

This survey highlights the wide-ranging and often severe impact of FAs on both physical and social experience and the need to ensure adequate efforts are made to provide effective treatment. Clinicians should consider proactive assessment and treatment of facial angiofibromas with available treatments, which may include topical rapamycin/sirolimus among other therapeutic options, such as laser ablation and electro-dissection.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Western Institutional Review Board (Tracking number: 20214481). Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

MM authored the manuscript and implemented editorial changes following the feedback. SA critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version to be published. MK contributed to the conception/design of the study, contributed to the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final version to be published. PT and LL contributed to the design, dissemination of the study, critically reviewed, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version to be published. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors would like to thank all the study participants for their contributions to this survey. In addition, the authors acknowledge the support received from the TSC patient organizations involved in this study; the Tuberous Sclerosis Association (TSA), based in the UK and the European Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Association (E-TSC) as well as the Tuberous Sclerosis Germany (TSDEV) both based in Germany. The report of the survey was authored by Adelphi Real World: Neil Reynolds, Megan O'Brien, and Laura Mirams, Lauren Bateman.

This study was commissioned by Plusultra pharma, David Jones and Mark Partington. The report was produced by Adelphi Real World. The Tuberous Sclerosis Association (TSA) has received sponsorship for events from PlusUltra Pharmaceuticals. MM is completing a study with a salary funded by PTC Therapeutics. No personal financial relation to pharmaceutical companies. SA has received funding from GW Pharmaceuticals, Norvartis, PTC Therapeutics, Boston Scientific, Nutricia, UCB, BioMarin, LivaNova, Medtronic, Desitin, Ipsen, CDKL5 UK, TSA and the National Institute for Health Research.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

EphMRA, European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association; FA, Facial Angiofibroma; GDPR, General Data Protection Regulations; mTOR, mammalian (or “Mechanistic”) Target of Rapamycin; PO, Patient Organisation; TAND, TSC Associated Neuropsychiatric Disorders; TSC, Tuberous Sclerosis Somplex; UK, United Kingdom; WIRB, Western Institutional Review Board.

1. Stroke NIoNDA. National Institute of Neurological Disorders S. Tuberous Sclerosis. Definitions (2019).

2. Vries PJ, Wilde L, Vries MC, Moavero R, Pearson DA, Curatolo P. A clinical update on tuberous sclerosis complex-associated neuropsychiatric disorders (TAND). Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet. (2018) 178:309–20. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31637

3. Rendtorff ND, Bjerregaard B, Frödin M, Kjaergaard S, Hove H, Skovby F, et al. Analysis of 65 tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) patients byTSC2DGGE,TSC1/TSC2MLPA, andTSC1long-range PCR sequencing, and report of 28 novel mutations. Human Mutation. (2005) 26:374–83. doi: 10.1002/humu.20227

4. O'Callaghan FJ, Shiell AW, Osborne JP, Martyn CN. Prevalence of tuberous sclerosis estimated by capture-recapture analysis. Lancet. (1998) 351:1490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78872-3

5. Webb DW, Clarke A, Fryer A, Osborne JP. The cutaneous features of tuberous sclerosis: a population study. Br J Dermatol. (1996) 135:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb03597.x

6. Józwiak S, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK, Michałowicz R, Chmielik J. Skin lesions in children with tuberous sclerosis complex: their prevalence, natural course, and diagnostic significance. Int J Dermatol. (1998) 37:911–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00495.x

7. Northrup H, Aronow ME, Bebin EM, Bissler J, Darling TN, de Vries PJ, et al. Updated international tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations. Pediatr Neurol. (2021) 123:50–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2021.07.011

8. Amin S, Lux A, Khan A, O'Callaghan F. Sirolimus ointment for facial angiofibromas in individuals with tuberous sclerosis complex. Int Sch Res Notices. (2017) 2017:8404378. doi: 10.1155/2017/8404378

9. Vivar KL, Kruse L. The impact of pediatric skin disease on self-esteem. Int J Womens Dermatol. (2018) 4:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.11.002

10. Chernyshov PV. Stigmatization and self-perception in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. (2016) 9:159–66. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S91263

11. Nguyen CM, Koo J, Cordoro KM. Psychodermatologic effects of atopic dermatitis and acne: a review on self-esteem and identity. Pediatr Dermatol. (2016) 33:129–35. doi: 10.1111/pde.12802

12. Wataya-Kaneda M, Nagai H, Ohno Y, Yokozeki H, Fujita Y, Niizeki H, et al. Safety and efficacy of the sirolimus gel for tsc patients with facial skin lesions in a long-term, open-label, extension, uncontrolled clinical trial. Dermatol Ther. (2020) 10:635–50. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00387-7

13. Salido-Vallejo R, Garnacho-Saucedo G, Moreno-Giménez JC. Current options for the treatment of facial angiofibromas. Actas Dermo Sifiliog. (2014) 105:558–68. doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2014.05.001

14. Jansen AC, Vanclooster S, de Vries PJ, Fladrowski C, Beaure d'Augères G, Carter T, et al. Burden of illness and quality of life in tuberous sclerosis complex: findings from the TOSCA study. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:904. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00904

15. Crall C, Valle M, Kapur K, Dies KA, Liang MG, Sahin M, et al. Effect of angiofibromas on quality of life and access to care in tuberous sclerosis patients and their caregivers. Pediatr Dermatol. (2016) 33:518–25. doi: 10.1111/pde.12933

16. Association EPMR Others. The EphMRA Code of Conduct for International Healthcare Market Research (2012).

17. Muzykewicz DA, Newberry P, Danforth N, Halpern EF, Thiele EA. Psychiatric comorbid conditions in a clinic population of 241 patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsy Behav. (2007) 11:506–13. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.07.010

18. Do JE, Cho SM, In SI, Lim KY, Lee S, Lee ES. Psychosocial aspects of acne vulgaris: a community-based study with korean adolescents. Ann Dermatol. (2009) 21:125–9. doi: 10.5021/ad.2009.21.2.125

Keywords: tuberous sclerosis, facial angiofibromas, rapamycin, sirolimus, TSC

Citation: Monaghan M, Takhar P, Langlands L, Knuf M and Amin S (2022) Impact of facial angiofibromas in tuberous sclerosis complex and reported efficacy of available treatments. Front. Med. 9:967971. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.967971

Received: 13 June 2022; Accepted: 01 August 2022;

Published: 29 August 2022.

Edited by:

Alvise Sernicola, University of Padua, ItalyReviewed by:

Chiara Iacovino, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Monaghan, Takhar, Langlands, Knuf and Amin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marie Monaghan, bW9uYWdoYW4ubWFyaWVAb3V0bG9vay5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.