- 1Clinical Pharmacy and Practice Department, College of Pharmacy, QU Health, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

- 2Pharmaceutical Sciences Department, College of Pharmacy, QU Health, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

- 3Research and Instruction Section, Library Department, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar

Introduction: In health professions education (HPE), acknowledging and understanding the theories behind the learning process is important in optimizing learning environments, enhancing efficiency, and harmonizing the education system. Hence, it is argued that learning theories should influence educational curricula, interventions planning, implementation, and evaluation in health professions education programs (HPEPs). However, learning theories are not regularly and consistently implemented in educational practices, partly due to a paucity of specific in-context examples to help educators consider the relevance of the theories to their teaching setting. This scoping review attempts to provide an overview of the use of social theories of learning (SToLs) in HPEPs.

Method: A scoping search strategy was designed to identify the relevant articles using two key concepts: SToLs, and HPEPs. Four databases (PubMed, ERIC, ProQuest, and Cochrane) were searched for primary research studies published in English from 2011 to 2020. No study design restrictions were applied. Data analysis involved a descriptive qualitative and quantitative summary according to the SToL identified, context of use, and included discipline.

Results: Nine studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. Only two SToLs were identified in this review: Bandura's social learning theory (n = 5) and Lave and Wenger's communities of practice (CoP) theory (n = 4). A total of five studies used SToLs in nursing programs, one in medicine, one in pharmacy, and two used SToLs in multi-disciplinary programs. SToLs were predominantly used in teaching and learning (n = 7), with the remaining focusing on assessment (n = 1) and curriculum design (n = 1).

Conclusions: This review illustrated the successful and effective use of SToLs in different HPEPs, which can be used as a guide for educators and researchers on the application of SToLs in other HPEPs. However, the limited number of HPEPs that apply and report the use of SToLs suggests a potential disconnect between SToLs and educational practices. Therefore, this review supports earlier calls for collaborative reform initiatives to enhance the optimal use of SToLs in HPEPs. Future research should focus on the applicability and usefulness of other theories of learning in HPEPs and on measuring implementation outcomes.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#registryofsystematicreviewsmetaanalyses/registryofsystematicreviewsmeta-analysesdetails/60070249970590001bd06f38/, identifier review registry1069.

Introduction

Health professions education (HPE) is the field of expertise applied to the education of health care practitioners which caters to the specific requirements of students and is used to develop, implement, and evaluate all aspects of health professions curriculum (1). Acknowledging and understanding the theories behind the learning process is important in optimizing learning environments, enhancing efficiency, and harmonizing the education system (2), since theory and practice are inextricably linked and mutually inform each other (3, 4). Understanding learning theories helps academics and researchers recognize the nature of knowledge acquisition and how to measure learning outcomes. This improved perception will enhance the scholarship of teaching and the understanding of educators within various contexts, namely teaching, curriculum development, mentoring, academic leadership, and learner assessment (5). Furthermore, it will help learners recognize their learning processes and ultimately assist in enhancing their learning outcomes (6). Learning theories can be implemented, based on appropriateness, in learning processes at individual, group or community levels and in various forms of educational activities (7).

In health professional education programs (HPEPs), learning theories are not regularly and consistently implemented, which has resulted in accreditation bodies dictating educational agendas (8), variation in the extent to which learning theories are used in HPEPs, and ultimately a potential disconnect between learning theories, curriculum design, outcome evaluation, and educational practices (9). This is also evidenced by an unfamiliarity among educators inadequately trained to apply theories in a range of contexts with various learner characteristics (5, 6, 10–12). Mukhalalati and Taylor provide an easy-to-use summarized guide of key learning theories used in HPEPs with examples of how they can be applied. The guide aims to assist healthcare professional educators in selecting the most appropriate learning theory to better inform curricula design, teaching strategies, and assessment methods, which in turn reflects on learner experience (13). There is a paucity of literature reviewing the use of learning theories in HPE, the majority of this being generally descriptive, explaining different learning theories and potential HPEP application. For example, little has been reported about the use of learning theories or active learning strategies in e-learning for evidence-based practices (14), or making suggestions for utilizing the conceptual aspects of learning theories in the identification and implementation of effective practices for evaluating teaching practice (15). With a focus on the significance of health professions educators' professional development, using learning theories to enhance teaching skills, particularly in clinical settings (16), the extant literature does not provide clear guidance, for example via the provision of examples of practical application and how these conceptual frameworks might advance the scholarship of teaching and learning in HPEPs. Therefore, health professions education scholars recommend conducting more research into the influence of implementing learning theories on core education components of the HPEPs, namely: curriculum design, content development, teaching, and assessment (13, 17). Such research aims to demonstrate the benefits of implementing learning theories and pedagogies in HPEPs, ultimately reducing the gap between learning theories and educational practices (17).

Social theories of learning (SToLs) play an important role in the design and implementation of HPEPs (2, 10, 18). SToLs integrate the concept of behavioral modeling and focus on social interaction, the person, context, community, and the desired behavior as the main facilitators of learning (19). The use of SToLs in HPEPs varies possibly due in part to a lack of awareness of available SToLs and a paucity of specific in-context examples to help educators consider the theories relevant to their teaching situation. SToLs include zone of proximal development, sociocultural theories, Bandura's social learning and social cognitive theories (SLT and SCT), situated cognition, and communities of practice (13, 20–25). Zone of proximal development is defined as “the distance between the actual development level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with a more capable peer” (26). According to sociocultural theories, learning and development are embedded within social events and take place as a learner interacts with other people, things, and events in a collaborative setting (26). Bandura's social learning theories (SLTs), i.e., SLT and SCT, stress the necessity of observing, modeling, and mimicking other people's behaviors, attitudes, and emotional reactions such that environmental and cognitive variables interact to impact human learning and behavior (18, 25). Situated cognition theory asserts that learning occurs when a learner is doing something in both the real and virtual worlds, and hence learning takes place in a situated activity with social, cultural, and physical settings (27). Community of practice “are groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly” (28).

To date, no study has examined the application of SToLs in HPEPs and the nature of their use. Consequently, this scoping review aims to examine the application of SToLs in HPEPs. The specific objectives are to (1) identify the SToLs applied to HPEPs, and (2) examine how SToLs are applied to learning and teaching processes in HPEPs.

Method

Protocol and registration

This study adopted a scoping review approach involving exploring and documenting the breadth of knowledge and practice in the investigated topic (29). The protocol for this scoping review was registered at RESEARCH REGISTRY [https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#registryofsystematicreviewsmeta-analyses/registryofsystematicreviewsmeta-analysesdetails/60070249970590001bd06f38/] with the number [reviewregistry1069]. This scoping review is compliant with the PRISMA statement for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (30).

Eligibility criteria

The main focus of this review was to identify articles that describe the applications of SToLs in undergraduate or postgraduate teaching and learning processes. The eligibility criteria included primary research studies that were electronically available in their entirety, published in English during the last 10 years (i.e., 2011–2020), and that reported the use of a SToL, namely: zone of proximal development, sociocultural theories, Bandura's SLTs, situated cognition, and communities of practice.

Primary research articles should report the use of SToLs explicitly and as a central theme, and a description of how SToLs were applied in HPEPs should be mentioned in order to be included in the study. No restrictions were applied to the study design. Primary research studies that used a theory other than the determined ones, mentioned SToLs only in the introduction, or used SToLs for data analysis, and/or as a theoretical framework, rather than as an intervention or an application in HPEP teaching and learning processes, were also excluded. Moreover, articles published more than 10 years ago were not included. Based on the authors experience in this field and on their extensive review of the literature, the scarcity of research that applies SToLs to undergraduate and postgraduate HPE became apparent (8, 9, 31). An initial testing search was conducted with no timeframe boundaries, to refine the search strategy and conduct a comprehensive review. Despite returning a significant number of records, initial screening indicated the irrelevance of the vast majority of studies. Therefore, the authors decided to restrict the timeframe to 10 years to reflect the most recent application of SToLs in HPE and the growth and volume of knowledge related to teaching and learning. Article types other than primary research literature (e.g., reviews, editorials, letters, opinion articles, commentaries, essays, preliminary notes, pre-print/in process, and conference papers) were also excluded from this review because such applications are usually reported in primary research articles. Theses and dissertations were also excluded because they risked being less scientifically rigorous due to a lack of peer-review and being unpublished in commercial journals (32).

Information sources

The search strategy was developed by a multidisciplinary team. This included academics (BM, FH, ME, and SE) with expertise in pharmacy, healthcare professions education, learning theories, and systematic review studies, and an academic research and instruction librarian (AB) with expertise in health science, education, pharmacy, and medical databases. A search of the electronic literature was performed by AB in December 2020 and January 2021, using PubMed, ERIC, ProQuest, and Cochrane databases. Two key concepts (SToLs, HPEPs) were combined using the Boolean connector (AND). Keywords used in the social learning theories concept search included: “social learning theories,” “social theories of learning,” “social cognitive theories,” “zone of proximal development,” “sociocultural theories,” “situated cognition,” “community/communities of practice.” Keywords for this concept were combined using the Boolean connector (OR). Keywords used to search for the HPEPs concept included “healthcare professional education,” “health care professional education,” “medical program education,” “pharmacy program education,” “health sciences program education,” “nursing program education,” “midwifery program education,” “nutrition program education,” “dietician program education,” “biomedical program education,” “physiotherapy program education,” “physical therapy program education,” “occupational therapy program education,” “radiation therapy program education,” “public health program education,” and “dental program education.” Keywords for this concept were combined using the Boolean connector (OR). Keywords were matched to database-specific indexing terms and applied based on each database as appropriate.

Search

The PubMed database was searched on December 22, 2020, implementing date (i.e., 2011–2020) and language (i.e., English only) filters, resulting in 689 articles. The following search strategy was used: “social learning theor*”[Title/Abstract] OR “social theor* of learning”[Title/Abstract] OR “social cognitive theor*”[Title/Abstract] OR “zone of proximal development”[Title/Abstract] OR “situated cognition”[Title/Abstract] OR “sociocultural theor*”[Title/Abstract] OR communit* of practice[Title/Abstract] AND Education[MeSH Terms] OR healthcare professional education[Title/Abstract] OR health care professional education[Title/Abstract] OR health sciences program education[Title/Abstract] OR nutrition program education[Title/Abstract] OR diet* program education[Title/Abstract] OR biomedical program education[Title/Abstract] OR physiotherapy program education[Title/Abstract] OR physical therapy program education[Title/Abstract] OR occupational therapy program education[Title/Abstract] OR radiation therapy program education[Title/Abstract]. Completed search strategies for other databases are presented in Supplementary material 1.

Selection of sources of evidence

Two investigators (BM and FH) conducted the title and abstract screening for the identified articles from the search strategy outlined above after duplicates and any clearly irrelevant articles had been removed. Full-text screening was conducted initially by two investigators (BM and MJ) who assessed the eligibility of the studies independently. Further multiple rounds of full-text reviews were performed by four investigators (BM, SE, MJ, and FH) to ensure that studies directly relevant to the objectives were included in this review. Disagreements were resolved by consensus via meetings and discussions.

Data charting process and data items

An extraction sheet was designed to tabulate data from the included articles using a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet. The extracted data included: (1) article information (title, author(s), year of publication, and journal name), (2) setting information (setting, organization name, whether the organization was public or private, and country), (3) research information (objective, design, HPEP), (4) theory information (name of the theory, context of application, description of how the theory was applied, the outcomes assessed, and methods of analysis), (5) outcome information (number of participants involved, intervention provided, duration of intervention, overall outcome and recommendations, and reported limitations related to the theory), and (6) the applicability to other disciplines. The context of the SToLs application includes teaching and learning (strategies used to deliver and receive educational content in clinical or non-clinical settings, etc.), curriculum development (learning objectives, planning of teaching strategies, program evaluation, etc.), or assessment (development, validation, and administration of assessment activities, etc.). The data extraction sheet was piloted by two investigators (BM and MJ) using four sample articles included in this review. Based on successful piloting, complete data extraction was done by four investigators (BM, FH, ME, and SE).

Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence

The included studies were not evaluated for quality or critically appraised because of methodological heterogeneity among studies. However, this lack of quality evaluation and critical appraisal aligns with the general standards of scoping reviews (33).

Synthesis of results

Descriptive numeric analysis was used to summarize data retrieved from the included articles according to the proportion of (1) articles per discipline, (2) SToLs applied, and (3) contexts in which SToLs were used. Moreover, the analysis of the data involved conducting a narrative description of the included articles by two independent investigators (MJ and FH). Consensus was reached on the basis of the analyzed data.

Results

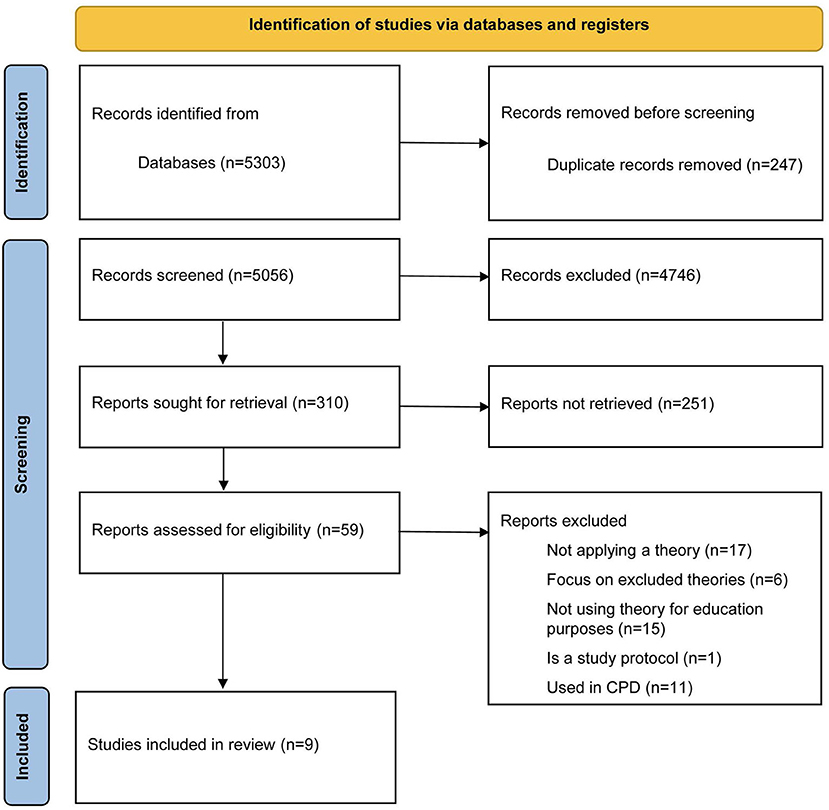

Out of 5,303 articles retrieved from databases, 247 were duplicates and hence removed (Figure 1). Following the title and abstract screening of 5,056 articles, 310 articles were eligible for full-text screening. Primary reasons for exclusion include: article types other than primary research literature (e.g., review articles, description of a theory, editorial letters, commentaries, protocols), thesis or dissertations, articles that described the use of theories other than SToLs, articles that did not implement SToLs or did not implement them in undergraduate or postgraduate education (e.g., implemented them for faculty development), articles that focused on other professions and not on health professions, and articles that used SToLs for data analysis purposes. Other reasons for exclusion included manually detected duplicates. A total of nine articles were qualified for inclusion and were used to inform this scoping review.

Characteristics of included studies

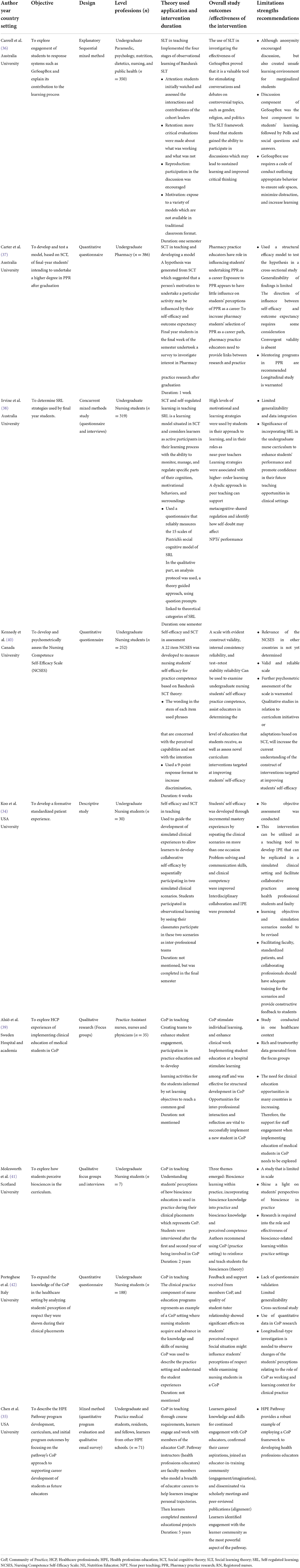

Of studies published between 2013 and 2019, two studies were conducted in the USA (34, 35), three in Australia (36–38), and one study in each of these countries: Sweden (39), Canada (40), Scotland (41), and Italy (42). A total of five studies used Bandura's SLTs (34, 36–38, 40), while four used Lave and Wenger's CoP theory (35, 39, 41, 42). Three studies used a qualitative research methodology (39–41), two studies used quantitative research methodology (37, 42), and three studies used a mixed-method design (35, 36, 38). The remaining study, educational innovation, focused on describing the implementation of a teaching strategy (34). A total of five studies used SToLs in nursing programs (34, 38, 40–42), one in medicine (39), one in pharmacy (37), and two were multi-disciplinary, including: paramedicine, psychology, nutrition and dietetics, nursing, public health, medicine, and other HPEPs (35, 36). Seven studies used SToLs in teaching and learning (34, 36–39, 41, 42), one in assessment (40), and one in curriculum design (35). The included studies covered a total of 1,780 participants (i.e., undergraduate students, residents, clinical teachers, and healthcare professionals) (Table 1).

Bandura's SLTs

Five studies in this scoping review focused on utilizing Bandura's SLTs in the teaching, learning, and assessment of health professions students (34, 36–38, 40). The use of Bandura's SLTs in the included studies suggested its advantages in improving students' self-efficacy and confidence, collaborative learning, learning experiences and future teaching experience and career research intentions.

In 1977, Bandura proposed an SLT based on a series of human behavioral studies (24). According to Bandura, learning takes place in social settings and occurs not only through an individual's own experiences, but by observing the actions of others and their consequences (24, 43). Social learning is also referred to as observational learning because learning takes place as a result of observing others (i.e., models), which Bandura's previous studies demonstrated as a valuable strategy for acquiring new behaviors (44). Bandura and his colleagues continued to demonstrate modeling/observational learning as a very efficient method of learning (44). Bandura's theorizing of the social development process later incorporated motivational and cognitive processes into SLT (44). In 1986, Bandura renamed his original SLT to SCT to emphasize the critical role that cognition plays in encoding and the performance of activities (44, 45). SCT suggests that learning occurs in a social context with a dynamic and reciprocal interaction of the person, environment, and behavior (25). The core constructs of SCT include modeling/observational learning, outcome expectancies, self-efficacy and self-regulation (25, 44). Bandura's observational learning consists of four stages: (1) attention: learners see the behavior they want to reproduce, (2) retention: learners retain the behavior they have seen entailing a cognitive process in which learners mentally rehearse the behavior they wish to replicate, (3) reproduction: learners put the processes obtained in attention and retention into action, and (4) motivation: learners imitate the observed behavior through reinforcement (direct, vicarious or self-reinforcement).

Based on Bandura's argument that human behavior is learnt via interactions with, and modeling of others in social contexts, Carroll et al. (36) applied the four stages of observational learning to investigate the effectiveness of GoSoapBox, a student response system (SRS). The study proved the effectiveness of this online tool in stimulating discussions on controversial topics, improving learning experiences and in-class engagement among paramedic, psychology, nutrition and dietetics, nursing, and public health students.

Carter et al. (37) focused on the self-efficacy, outcome expectancy and social influence components of SCT to develop and test a model that evaluates undergraduate pharmacy students' intentions to pursue a higher pharmacy practice research (PPR) degree. The authors suggest that educators must provide links between practice and research and increase student self-confidence to undertake PPR, thereby increasing interest in this as a future career path. This is because exposure alone has minimal influence on a student's interest in PPR as a career.

Irvine et al. (38) explored self-regulated learning (SRL), a learning model situated in SCT, strategies utilized by final year nursing students in both their approaches to learning and practical teaching sessions (peer-teaching). The study findings support the use of SRL in nursing education, as highlighted by the high level of motivational behaviors and learning strategies reported among undergraduate nursing students in their approach to learning and their roles as peer-teachers.

Kennedy et al. (40) used the construct of self-efficacy to develop and psychometrically assess a scale that examines undergraduate nursing students' self-efficacy practice competence, assist educators in determining the level of education that students receive, as well as their level of confidence and advocacy for positive changes.

Furthermore, Koo et al. (34) indicated that implementing a self-efficacy construct to develop a formative standardized patient experience allowed nursing students to develop the concepts of inter-professional collaborative communication, and enhanced their problem-solving and communication skills, as well as their clinical competency.

Lave and Wenger's theory: Communities of practice (CoP)

The CoP theory consists of three key components: the domain (the common interest among all members), the practice (the implicit and explicit knowledge shared), and the community (made up of mutually beneficial interactions between experts and learners leading to learning, engagement, and identity development) (10, 46–48). All the articles retrieved in this review described a CoP as a group of people who share similar characteristics and collaborate toward a common goal, therefore enhancing mutual learning through sharing relevant knowledge and fostering the development of a shared identity. Three of the studies implemented CoP theory with a focus on teaching and learning among health professions students, and one with a focus on HPEP curricula design. All studies indicated that implementing the CoP learning theory enhanced student learning, collaboration, and identity.

Alsio et al. (39) found that when CoP theory was used to create teams of practicing nurses, physicians, and undergraduate medical students with the mandate of developing learning activities during their clinical placements, learning was stimulated through self-reflection and consideration of their perspectives during patient interactions. Further, inter-professional reflection was vital for successful introduction of new students into a CoP and was effective for structural and cultural development. Moreover, staff and students' awareness of their roles and responsibilities facilitated their motivation to participate in the CoPs implementation.

Similarly, Molesworth et al. (41) and Protoghese et al. (42) explored the experiences of undergraduate nursing students regarding their application of the CoP theory during clinical placements. Both studies argued that CoP helped students to integrate their theoretical learning of bioscience into practice (41), and to advance their existing clinical knowledge (42). Moreover, application of bioscience knowledge within a CoP facilitated effective inter-professional relationships (41). Additionally, students perceived that they received more respect, support, and feedback while learning within a CoP (42). This further emphasizes the significance of mutual engagement and the collaborative relationship component of the CoP theory in enhancing student learning (42).

Furthermore, Chen et al. (35) used CoP theory in a curricular design for the HPEP aimed at helping undergraduate medical students, residents, fellows, and learners from other HPE schools to develop their identities as future health professions educators. The program has demonstrated its effectiveness in providing learners with the knowledge and skills to realize their career aspirations. It also enhanced learners' enthusiasm for teaching and increased their interest in educational leadership, innovation, and research.

Discussion

This scoping review attempted to provide an overview of how SToLs have been used in the teaching and learning of HPEPs over the last decade. This review highlighted some interesting findings that, collectively, may provide insights into how educational practices in HPEPs are shaped and influenced by learning theories.

Bandura's SLTs

Bandura's SLTs were applied predominantly in teaching and instruction strategies within the HPEPs. This review demonstrated the application of Bandura's observational learning model in the form of in-class integrated collaborative learning activities through an online tool for improving learning experiences and engagement (36). It is argued that observational learning provides a faster and safer approach to learning complicated patterns of behavior than trial and error, making it consistent with and suitable for HPE (7, 49). Self-efficacy, defined by an individuals' assessment of their capacity to perform given tasks or activities and achieve specified goals (50), was the most highlighted construct in the included articles. This can be explained by Bandura's argument that self-efficacy is central to social learning because it significantly impacts a wide range of human endeavors, including developmental and health psychology, education, and in the workplace (19). The findings suggest that the self-efficacy construct is beneficial to the learning outcome, particularly in simulation contexts, as demonstrated in the review conducted by Lavoie et al. (51). This aligns with previous literature about the self-efficacy construct indicating that individuals with stronger self-efficacy for certain tasks are more motivated to execute them (50, 52). Furthermore, the self-efficacy construct was used to develop an assessment tool that evaluates students competence and confidence level and advocacy for positive changes as they become professional nursing practitioners (40). In this context, it is worth mentioning that assessment tools based on self-efficacy found in previous health-related literature are task-specific (53, 54). Previous literature has also argued that feelings of confidence among medical students are associated with competence and proficiency (55, 56), and lack of confidence leads to nurses leaving the profession (57). Moreover, clinical educators' self-efficacy and confidence are critical to their ability to carry out their teaching and training responsibilities as they affect student achievement and patient outcomes (58).

Lave and Wenger's CoP theory

In this review, CoP theory was mainly employed in the teaching and learning of health professions students, educators, and providers to improve learning, collaboration, and identity. However, as highlighted by Hörberg et al. (59), it would be better used to identify team challenges and provide more meaningful interventions. It is noteworthy that none of the included studies highlighted any long-term benefits of CoP, aligning with Allen et al.'s (60) argument that there is a paucity of health professions studies exploring the long-term effect of CoP on individuals and the relevance to educational outcomes. Additionally, several studies in healthcare education and practice indicated the scarcity of studies that focus on the development and assessment of CoPs (10, 61, 62).

This review highlights a scarcity of research focusing on the application of SToLs in the development, validation, and conduction of assessment activities within HPEPs. Only one study used the self-efficacy construct to develop a tool for assessing student competence (40). This is consistent with a recent literature review suggesting that SToLs are not applied in performing assessment activities compared to other learning theories, such as humanistic theories or motivational models (13). This is despite evidence of the utility of CoP learning theory in planning and implementing effective assessment measures in the PharmD program (20).

The current review suggests that the application of SToLs in designing HPEPs' curricular content, learning objectives, syllabus or influencing educational competencies is also not common. In this regard, Mukhalalati and Taylor proposed a novel CoP theory-informed framework that can be used in designing a new HPEP to reduce the disconnect between the educational practice and learning theories (10). The authors suggest key components to consider when developing a CoP-based curriculum, including but not limited to, complementing formal with informal learning, transferring tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge through socialization and externalization, re-contextualizing knowledge, and aligning students' learning needs to learning activities (10). These components are compatible with several SToLs and claimed to be applicable in various HPEPs (10).

An important observation in this review was the exclusion of a large number of retrieved articles because they failed to inform how SToLs are implemented in the educational practices and in delivering educational goals (63), or because they aimed to use SToLs as a lens to explore HPEPs teaching and learning practices, or as a theoretical framework to conceptualize or analyze HPE research data (64–66). This aligns with previous research that highlighted the significance of using theories to enhance research rigor and its relevant outcomes (67). However, it is suggested to use learning theories to critique HPE and guide its advancement initiatives (68, 69). Furthermore, several excluded studies utilized SToLs for healthcare professionals continuing professional development (70–75), which seems to be a common application of SToLs. Although examining SToLs utilization in continuing professional development activities was not the aim of conducting this review, this aspect is extremely important as it indirectly influences students who will ultimately become health care professionals. Collectively, the small number of included eligible studies in this review that applied SToLs in HPEPs suggests disconnect between SToLs and HPEPs educational practices. It is argued that it is challenging for HPEPs educators to apply the educational theories because they received minimal or no educational training about their significance and implementation (5). Therefore, as recommended by previous research, a collaborative reform initiative should be enacted to enhance the optimal use of SToLs in educational practice and examine the applicability and usefulness of other theories of learning in HPEP (20). Moreover, this review did not include studies from Africa, Eastern Mediterranean, and South-East Asia, suggesting that exploratory and experimental educational research utilizing various learning theories are highly warranted in these regions.

Strengths and limitations

This review explored SToLs use in HPEPs and provided a valuable overview for educators in a broad range of health education fields. Studies included were conducted in various countries which further enhanced the results' applicability to other contexts. However, a number of limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the findings of this review. For example, this review was limited to only four databases and to the last decade, potentially missing relevant articles in other major databases such as Scopus and Web of Science and those published before 2011. Moreover, as is inherent to scoping reviews, a quality assessment for the included articles was not conducted necessitating caution in interpreting conclusions. Additionally, since SToLs can be categorized and named differently, this might inadvertently result in the omission of relevant articles.

Conclusions

This review provides an overview of the application of SToLs in HPEPs from 2011 to 2020. Only two SToLs were identified in this review: Bandura's SLT and SCT; and Lave and Wenger's CoP theory. Bandura's four-stage model of observational learning, as well as self-efficacy construct, were applied in the included studies. CoP theory was mainly employed to improve learning, collaboration, and identity, whilst SToLs use was predominantly focused on teaching and learning with less focus on assessment and curriculum design. This review demonstrated a limited number of HPEPs applying and reporting an application of SToLs despite the significance of the social aspect of learning concepts in those theories and within HPEP. This suggests a potential disconnect between SToLs and HPEP educational practices. Nonetheless, this review illustrated the successful and effective implementation of StoLs in various HPEPs, which is applicable to other HPEPs. Finally, this review supports the call for collaborative reform initiatives to optimize the use of StoLs in HPEPs educational practices. Future research should focus on the applicability and usefulness of other theories of learning in HPEP and investigate the long-term outcomes of theory implementation.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

Open Access funding is provided by the Qatar National Library.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2022.912751/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Sciences WUoH. Health Professions Education Track. Available online at: https://www.westernu.edu/health-sciences/mshs/health-professions-education-track/ (accessed June 21, 2022).

2. Aliakbari F, Parvin N, Heidari M, Haghani F. Learning theories application in nursing education. J Edu Health Promot. (2015) 4:2. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.151867

3. Poduska JM, Kurki A. Guided by theory, informed by practice: training and support for the good behavior game, a classroom-based behavior management strategy. J Emot Behav Disord. (2014) 22:83–94. doi: 10.1177/1063426614522692

4. Spouse J. Bridging Theory and practice in the supervisory relationship: a sociocultural perspective. J Adv Nurs. (2001) 33:512–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01683.x

5. Lacasse M, Douville F, Gagnon J, Simard C, Côté L. Theories and models in health sciences education–a literature review. Can J Scholar Teach Learn. (2019) 10:9477. doi: 10.5206/cjsotl-rcacea.2019.3.9477

6. Bajpai S, Semwal M, Bajpai R, Car J, Ho AHY. Health professions' digital education: review of learning theories in randomized controlled trials by the digital health education collaboration. J Med Internet Res. (2019) 21:e12912. doi: 10.2196/12912

8. Austin Z, Ensom MHH. Education of pharmacists in Canada. Am J Pharm Educ. (2008) 72:128. doi: 10.5688/aj7206128

9. Allan HT, Smith P. Are pedagogies used in nurse education research evident in practice? Nurse Educ Today. (2010) 30:476–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.10.011

10. Mukhalalati BA, Taylor A. The development of a theory-informed communities of practice framework for pharmacy and other professional healthcare education programs. Pharmacy Edu. (2018) 18:167–80. Available online at: https://pharmacyeducation.fip.org/pharmacyeducation/article/view/592

11. McInerney PA, Green-Thompson LP. Teaching and learning theories, and teaching methods used in postgraduate education in the health sciences: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database Sys Rev Implement Reports. (2017) 15:899–904. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003110

12. Capstick S, Green JA, Beresford R. Choosing a course of study and career in pharmacy—Student attitudes and intentions across 3 years at a New Zealand school of pharmacy. Pharm Edu. (2007) 7:811. doi: 10.1080/15602210701673811

13. Mukhalalati BA, Taylor A. Adult learning theories in context: a quick guide for healthcare professional educators. J Med Edu Curr Develop. (2019) 6:2382120519840332. doi: 10.1177/2382120519840332

14. Song CE, Park H. Active learning in e-learning programs for evidence-based nursing in academic settings: a scoping review. J Cont Edu Nurs. (2021) 52:407–12. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20210804-05

15. LaVelle JM, Lovato C, Stephenson CL. Pedagogical considerations for the teaching of evaluation. Eval Program Plann. (2020) 79:101786. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2020.101786

16. Omer AAA. The importance of theory to inform practice—theorizing the current trends of clinical teaching: a narrative review. Sudan J Med Sci. (2020) 15:383–98. doi: 10.18502/sjms.v15i4.8161

17. Moss C, Grealish L, Lake S. Valuing the gap: a dialectic between theory and practice in graduate nursing education from a constructive educational approach. Nurse Educ Today. (2010) 30:327–32. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.09.001

18. Bandura A, McClelland DC. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, Inc., (1977).

19. Grusec JE. Social Learning Theory. In: Benson JB, editor. Encyclopedia of Infant and Early Childhood Development (Second Edition). Oxford: Elsevier (2020). p. 221-8. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-809324-5.23568-2

20. Mukhalalati B. Examining the disconnect between learning theories and educational practices in the pharmd program at qatar university: a case study. Am J Pharm Edu. (2016) 84:9. doi: 10.5688/ajpe847515

21. Wenger E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press (1998). doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511803932

22. Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press (1991). doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511815355

23. Vygotsky L. Interaction between learning and development. Readings on the development of children. (1978) 23:34–41.

26. Vygotsky LS, Cole M. Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes: Harvard University Press (1978).

27. Ataizi M. Situated Cognition. Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning. Boston, MA: Springer US (2012):3082–4. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_16

28. Wenger E. Communities of Practice: A Brief Introduction. National Science Foundation. U.S. (2011).

29. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. (2010) 5:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

30. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. Prisma extension for scoping reviews (Prisma-Scr): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850

31. Husband AK, Todd A, Fulton J. Integrating science and practice in pharmacy curricula. Am Jf Pharmaceut Edu. (2014) 78:7863. doi: 10.5688/ajpe78363

32. Hartling L, Featherstone R, Nuspl M, Shave K, Dryden DM, Vandermeer B. Grey literature in systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study of the contribution of non-english reports, unpublished studies and dissertations to the results of meta-analyses in child-relevant reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2017) 17:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0347-z

33. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

34. Koo LW, Idzik SR, Hammersla MB, Windemuth BF. Developing standardized patient clinical simulations to apply concepts of interdisciplinary collaboration. J Nurs Edu. (2013) 52:705–8. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20131121-04

35. Chen HC, Wamsley MA, Azzam A, Julian K, Irby DM, O'Sullivan PS. The health professions education pathway: preparing students, residents, and fellows to become future educators. Teach Learn Med. (2017) 29:216–27. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2016.1230500

36. Carroll J-A, Sankupellay M, Newcomb M, Rodgers J, Cook R. Gosoapbox in public health tertiary education: a student response system for improving learning experiences and outcomes. Au J Edu Technol. (2018) 35:58–71. doi: 10.14742/ajet.3743

37. Carter SR, Moles RJ, Krass I, Kritikos VS. Using social cognitive theory to explain the intention of final-year pharmacy students to undertake a higher degree in pharmacy practice research. Am J Pharmaceut Edu. (2016) 80:80695. doi: 10.5688/ajpe80695

38. Irvine S, Williams B, Özmen M, McKenna L. Exploration of self-regulatory behaviours of undergraduate nursing students learning to teach: a social cognitive perspective. Nurse Educ Pract. (2019) 41:102633. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2019.102633

39. Alsiö Å, Wennström B, Landström B, Silén C. Implementing clinical education of medical students in hospital communities: experiences of healthcare professionals. Int J Med Edu. (2019) 10:54. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5c83.cb08

40. Kennedy E, Murphy GT, Misener RM, Alder R. Development and psychometric assessment of the nursing competence self-efficacy scale. J Nurs Edu. (2015) 54:550–8. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20150916-02

41. Molesworth M, Lewitt M. Preregistration nursing students' perspectives on the learning, teaching and application of bioscience knowledge within practice. J Clin Nurs. (2016) 25:725–32. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13020

42. Portoghese I, Galletta M, Sardu C, Mereu A, Contu P, Campagna M. Community of practice in healthcare: an investigation on nursing students' perceived respect. Nurse Educ Pract. (2014) 14:417–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2014.01.002

43. Bandura A. On the Functional Properties of Perceived Self-Efficacy Revisited. Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA (2012). p. 9-44. doi: 10.1177/0149206311410606

45. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall (1986) 1986(23-28).

46. Wenger E, McDermott RA, Snyder W. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing (2002).

47. Kothari A, Boyko JA, Conklin J, Stolee P, Sibbald SL. Communities of practice for supporting health systems change: a missed opportunity. Health Res Policy Syst. (2015) 13:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12961-015-0023-x

48. Bentley C, Browman GP, Poole B. Conceptual and practical challenges for implementing the communities of practice model on a national scale-a canadian cancer control initiative. BMC Health Serv Res. (2010) 10:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-3

49. Bahn D. Social learning theory: its application in the context of nurse education. Nurse Educ Today. (2001) 21:110–7. doi: 10.1054/nedt.2000.0522

50. Bandura A, Freeman W, Lightsey R. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Springer. (1999). doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.13.2.158

51. Lavoie P, Michaud C, Belisle M, Boyer L, Gosselin E, Grondin M, et al. Learning theories and tools for the assessment of core nursing competencies in simulation: a theoretical review. J Adv Nurs. (2018) 74:239–50. doi: 10.1111/jan.13416

52. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. (1977) 84:191. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

53. Goldenberg D, Andrusyszyn MA, Iwasiw C. The effect of classroom simulation on nursing students' self-efficacy related to health teaching. J Nurs Edu. (2005) 44:310–4. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20050701-04

54. Ravert PKM. Use of a Human Patient Simulator with Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Prototype Evaluation of Critical Thinking and Self-Efficacy (Dissertation). The University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, United States (2004).

55. Liaw SY, Scherpbier A, Rethans J-J, Klainin-Yobas P. Assessment for simulation learning outcomes: a comparison of knowledge and self-reported confidence with observed clinical performance. Nurse Educ Today. (2012) 32:e35–e9. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.10.006

56. Clanton J, Gardner A, Cheung M, Mellert L, Evancho-Chapman M, George RL. The Relationship between confidence and competence in the development of surgical skills. J Surg Educ. (2014) 71:405–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.08.009

57. Benner P, Sutphen M, Leonard V, Day L. Educating Nurses: A Call for Radical Transformation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass (2009).

58. Artino AR. Academic self-efficacy: from educational theory to instructional practice. Perspect Med Educ. (2012) 1:76–85. doi: 10.1007/s40037-012-0012-5

59. Hörberg A, Lindström V, Scheja M, Conte H, Kalén S. Challenging encounters as experienced by registered nurses new to the emergency medical service: explored by using the theory of communities of practice. Adv Health Sci Edu. (2019) 24:233–49. doi: 10.1007/s10459-018-9862-x

60. Allen LM, Palermo C, Armstrong E, Hay M. Categorising the broad impacts of continuing professional development: a scoping review. Med Educ. (2019) 53:1087–99. doi: 10.1111/medu.13922

61. Fung-Kee-Fung M, Boushey RP, Morash R. Exploring a “community of practice” methodology as a regional platform for large-scale collaboration in cancer surgery—the ottawa approach. Current Oncology. (2014) 21:13–8. doi: 10.3747/co.21.1662

62. McKellar KA, Pitzul KB Yi JY, Cole DC. Evaluating communities of practice and knowledge networks: a systematic scoping review of evaluation frameworks. Ecohealth. (2014) 11:383–99. doi: 10.1007/s10393-014-0958-3

63. Malwela T, Maputle SM, Lebese RT. Factors affecting integration of midwifery nursing science theory with clinical practice in vhembe district, limpopo province as perceived by professional midwives. Af J Prim Health Care Family Med. (2016) 8:1–6. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v8i2.997

64. Fredholm A, Manninen K, Hjelmqvist H, Silén C. Authenticity made visible in medical students' experiences of feeling like a doctor. Int J Med Edu. (2019) 10:113. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5cf7.d60c

65. Horsburgh J, Ippolito K. A Skill to be worked at: using social learning theory to explore the process of learning from role models in clinical settings. BMC Med Educ. (2018) 18:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1251-x

66. Burgess A, Haq I, Bleasel J, Roberts C, Garsia R, Randal N, et al. Team-based learning (Tbl): a community of practice. BMC Med Educ. (2019) 19:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1795-4

67. Stewart D, Klein S. The use of theory in research. Int J Clin Pharm. (2016) 38:615–9. doi: 10.1007/s11096-015-0216-y

68. Rees CE, Monrouxe LV. Theory in medical education research: how do we get there? Med Educ. (2010) 44:334–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03615.x

69. Albert M, Hodges B, Regehr G. Research in medical education: balancing service and science. Adv Health Sci Edu. (2007) 12:103–15. doi: 10.1007/s10459-006-9026-2

70. Cantillon P, D'Eath M, De Grave W, Dornan T. How do clinicians become teachers? a communities of practice perspective advances in health sciences. Education. (2016) 21:991–1008. doi: 10.1007/s10459-016-9674-9

71. Chlipalski M, Baker S, Olson B, Auld G. Evaluation and lessons learned from the development and implementation of an online prenatal nutrition training for efnep paraprofessionals. J Nutri Edu Behav. (2019) 51:749–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2018.11.013

72. Diker A, Cunningham-Sabo L, Bachman K, Stacey JE, Walters LM, Wells L. Nutrition educator adoption and implementation of an experiential foods curriculum. J Nutri Edu Behav. (2013) 45:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2013.07.001

73. Evans C, Yeung E, Markoulakis R, Guilcher S. An online community of practice to support evidence-based physiotherapy practice in manual therapy. J Cont Edu Health Profess. (2014) 34:215–23. doi: 10.1002/chp.21253

74. Sanderson BK, Carter M, Schuessler JB. Writing for publication: faculty development initiative using social learning theory. Nurse Educ. (2012) 37:206–10. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0b013e318262eae9

Keywords: social learning theory, social cognitive theory, communities of practice, health professions education, teaching, assessment, curriculum

Citation: Mukhalalati B, Elshami S, Eljaam M, Hussain FN and Bishawi AH (2022) Applications of social theories of learning in health professions education programs: A scoping review. Front. Med. 9:912751. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.912751

Received: 04 April 2022; Accepted: 08 July 2022;

Published: 28 July 2022.

Edited by:

Lynn Valerie Monrouxe, The University of Sydney, AustraliaReviewed by:

Eleanor Beck, University of Wollongong, AustraliaAna L. S. Da Silva, Swansea University Medical School, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Mukhalalati, Elshami, Eljaam, Hussain and Bishawi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Banan Mukhalalati, YmFuYW4ubUBxdS5lZHUucWE=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Banan Mukhalalati

Banan Mukhalalati Sara Elshami

Sara Elshami Myriam Eljaam

Myriam Eljaam Farhat Naz Hussain2†

Farhat Naz Hussain2† Abdel Hakim Bishawi

Abdel Hakim Bishawi