94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

METHODS article

Front. Med., 18 March 2022

Sec. Intensive Care Medicine and Anesthesiology

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.819134

This article is part of the Research TopicPost COVID-19: Analysing and Addressing the Challenges Faced by Patients Following Intensive Care Treatment for COVID-19View all 16 articles

Vanni Agnoletti1*

Vanni Agnoletti1* Emiliano Gamberini1

Emiliano Gamberini1 Alessandro Circelli1

Alessandro Circelli1 Costanza Martino1

Costanza Martino1 Domenico Pietro Santonastaso1

Domenico Pietro Santonastaso1 Giuliano Bolondi1

Giuliano Bolondi1 Giorgia Bastoni2

Giorgia Bastoni2 Martina Spiga2

Martina Spiga2 Paola Ceccarelli2

Paola Ceccarelli2 Luca Montaguti3

Luca Montaguti3 Fausto Catena4

Fausto Catena4 Venerino Poletti5

Venerino Poletti5 Carlo Lusenti6

Carlo Lusenti6 Claudio Lazzari6

Claudio Lazzari6 Mattia Altini7

Mattia Altini7 Emanuele Russo1

Emanuele Russo1Background: This study aimed to describe an innovative and functional method to deal with the increased COVID-19 pandemic-related intensive care unit bed requirements.

Methods: We described the emergency creation of an integrated system of internistic ward, step-down unit, and intensive care unit, physically located in reciprocal vicinity on the same floor. The run was carried out under the control of single intensive care staff, through sharing clinical protocols and informatics systems, and following single director supervision. The intention was to create a dynamic and flexible system, allowing for rapid and fluid patient admission/discharge, depending on the requirements due to the third Italian peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2021.

Results: This study involved 142 COVID-19 patients and 66 non-COVID-19 patients who were admitted; no critical patient was left unadmitted and no COVID-19 severe patients referring to our center had to be redirected to other hospitals due to bed saturation. This system allowed shorter hospital length-of-stay in general wards (5.9 ± 4 days) than in other internistic COVID-19 wards and overall mortality in line with those reported in literature despite the peak raging.

Conclusion: This case report showed the feasibility and the efficiency of this dynamic model of hospital rearrangement to deal with COVID-19 pandemic peaks.

Since its onset, the COVID-19 pandemic has pressured healthcare systems worldwide. We previously described a functional and dynamic strategy that allowed our intensive care unit (ICU) to deal with the first two peaks of the pandemic, in March and October 2020, that in our community reached 8.2 cases per 1,000 inhabitants (1).

The setting is a public hospital of 450 beds, which is a reference point for a population of about 210,000 people. Before COVID-19, the ICU consisted of 18 beds, whereas during the pandemic, 6 non-COVID ICU beds and 9 step-down unit (SDU) beds were opened.

This case study aimed to show how this dynamic system has been furtherly implemented to deal with the third and strongest pandemic peak, in March 2021, reaching a local incidence of 13.3 positive cases per 1,000 inhabitants (62% increase).

As the third peak was arising, all the hospital non-COVID wards were promptly resized and relocated. Strategically, the first units left empty were those close to the ICU-SDU (4th floor) and to the COVID-internal medicine (6th floor).

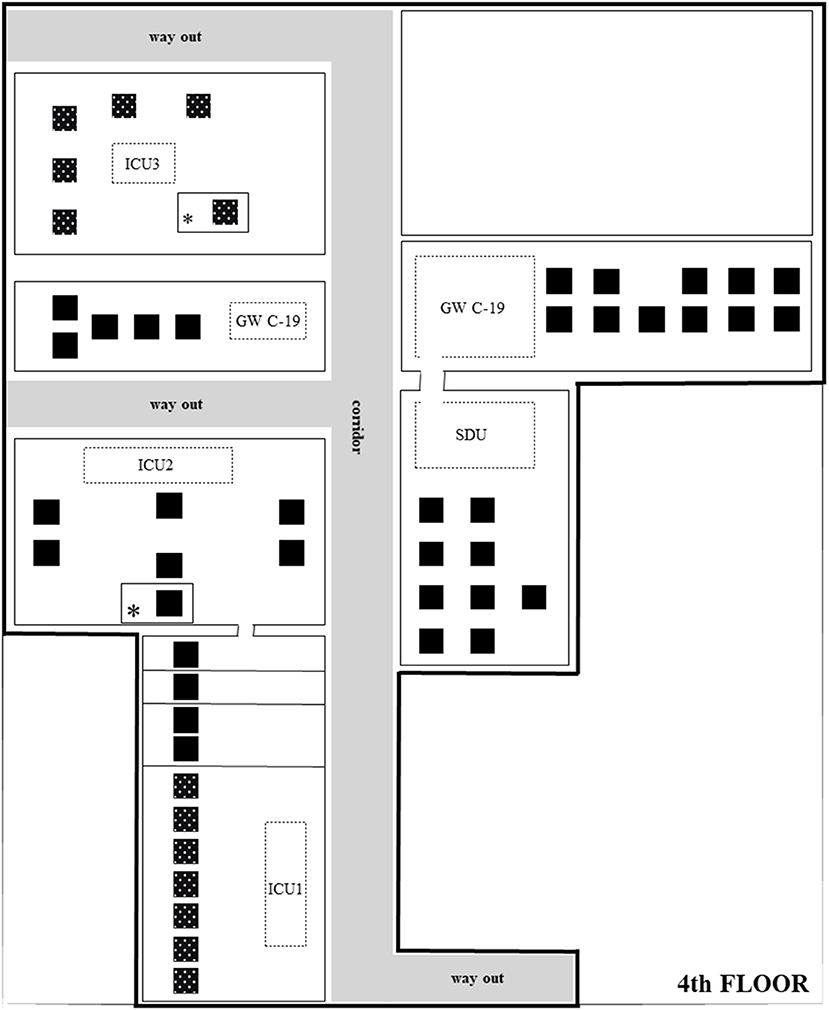

With respect to the previous strategy, a further internistic COVID unit, General Internal Medicine Ward COVID-19 (GWC19), of 16 beds was carved out on the 4th floor, next to the SDU (Figure 1). It was staffed by an intensivist physician, with an 8:1 patient-per-nurse ratio (PPNR), wherein nurses were not ICU-trained. Two monitored beds (oxygen saturation, non-invasive or invasive blood pressure, and ECG) for patients needing high flow nasal cannulae (HFNC) were available. Admission criteria to this general ward were the following: patients positive to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), with radiologic evidence of pulmonary interstitiopathy, dyspnea, oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≥ 92% on room air, and low oxygen supplementation (less 10 L/min). Clinical factors, such as fever, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, were considered risk factors for possibly severe evolution (2).

Figure 1. Critical area on the 4th floor. Planimetry and bed location of the 4th floor, under the direct control of the intensive care department. Full-black beds,COVID-19 patients; Spotted-black beds, non-COVID-19 patients; Asterick, supra-numerary beds, usually not in use, open only for emergency; Dotted rectangles with unit name, medical positions and monitor areas physically separated from patient's open-space.

The 4th floor, under the control of the intensive care department, thus counted on the following: 16 GWC19 beds, 1 intensivist, 8:1 PPNR; 9 beds SDU, 1 intensivist, and 3:1 PPNR (at least 1 ICU-trained nurse); 11 ICU1 beds, 2 intensivists (1 during the night shift), and 2:1 PPNR; 7 ICU2 beds, 2 intensivists (1 during the night shift), and 2:1 PPNR; 6 ICU3 beds, 1 intensivist, and 2:1 PPNR (Figure 1). Admission criteria to SDU were previously described (1).

This was made possible by a drastic 50% reduction of the planned operating room activity, actuated for safety reasons, that allowed to recover a sufficient number of anesthetists to be employed at the 4th floor. In Italy, anesthesia and intensive care still constitute a single residency program, thus specialists are certified and trained to manage complex patients with one or more ongoing organ failure.

In March 2021, the Italian Ministry of Health published new guidelines on the management of isolation of severe COVID-19 patients: (3) 21 days after the first SARS-CoV-2 positivity, if asymptomatic or with a negative molecular test, they were considerable non-infective and transferable to non-COVID units. This increased the fluidity in the management of bed occupancy.

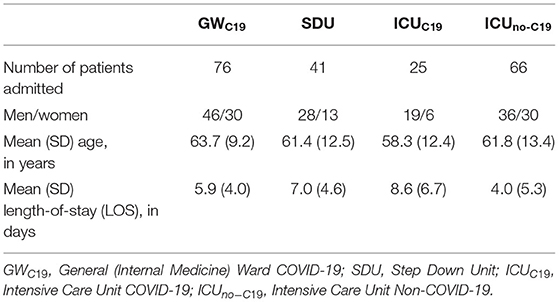

In March 2021 (31 days), a total of 142 COVID-19 patients and 66 non-COVID-19 patients were admitted to the 4th floor. Table 1 describes the characteristics of these patients. The 4th-floor setting allowed to admit every patient to a level of intensiveness appropriate for their clinical status.

Table 1. Clinical description of the patients admitted in the different units during the pandemic peak.

Mean length-of-stay (LOS) (SD) in days was 5.9 (4) for GWC19, 7 (4.6) for SDU, 8.6 (6.7) for ICU COVID-19 (ICUC19), and 4 (5.3) for ICU non-COVID-19 (ICUno−C19). The mortality rate was 2.6% for GWC19, 20% for SDU, 36% for ICUC19, and 9.2% for ICUno−C19, in line with available literature (4, 5).

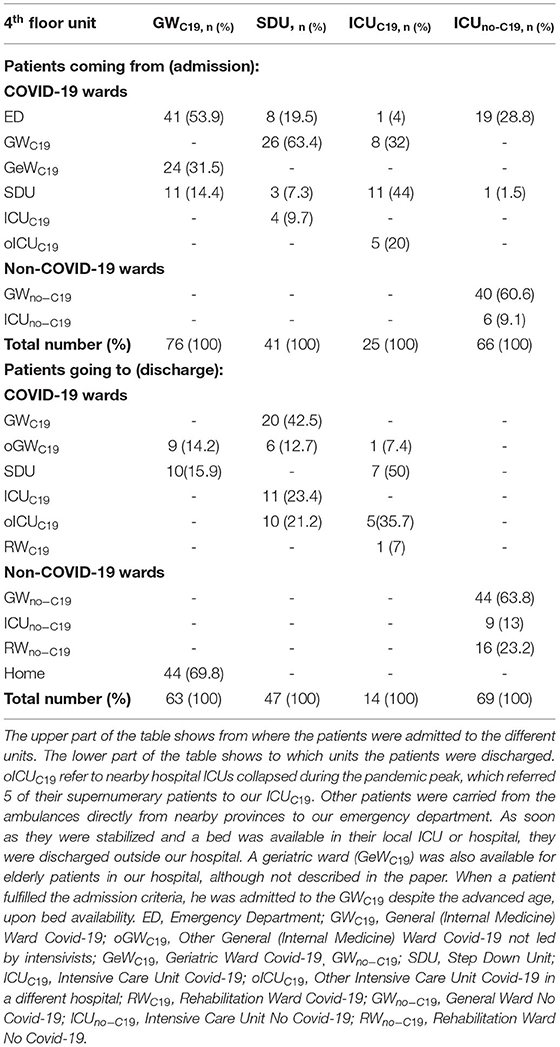

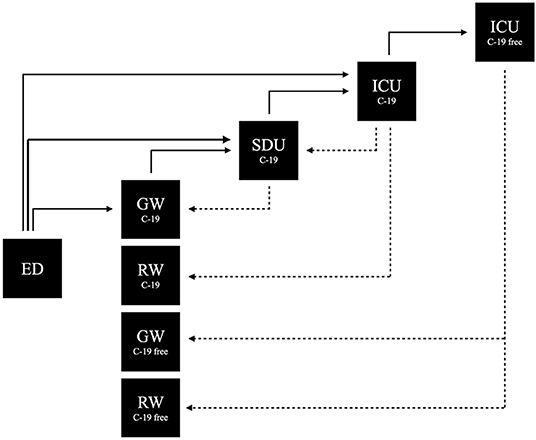

Table 2, Figure 2 summarize the overall flow of patients between different units.

Table 2. Summary of the provenience and the discharge destination of all the patients treated at the 4th floor integrated system led by the intensive care department.

Figure 2. Patient COVID-19 flow. Patients flow between the different units during the pandemic peak. For the number of patients refere to Table 2. ED, Emergency department; GW C-19, General ward COVID-19; RW C-19, Rehabilitation ward COVID-19; SDU C-19, Step down unit COVID-19; ICU C-19, Intensive care unit COVID-19; ICU C-19 free, Intensive care unit no-COVID-19; GW C-19 free, General ward no-COVID-19; RW C-19 free, Rehabilitation ward no-COVID-19.

Mean (± SD) LOS in GWC19 was shorter than in other internistic COVID-19 wards: 5.9 (4) days vs. 11.8 (5) days (p < 0.0001; unpaired t-test). This is probably due to the higher rapidity by which patients were transferred to a higher level of care through early detection of clinical deterioration and simple transfer systems or to the mindset of intensivists used to working with short timescales. All patients with severe COVID-19 who were referred to our hospital have been hospitalized, none needed to be referred to other hospitals, thanks to a system that avoided hospital bed saturation.

The decision to staff the GWC19 with anesthesiologists/intensivists was proposed by the hospital direction due to staff contingency. The director of anesthesia and ICU and the collaborators agreed with this setting, to ease and improve the management of patient discharge from ICU and SDU, trying to avoid bed saturation. Being part of the same team, sharing the same protocols, informatics system (Margherita 3), and coordinators allowed considerable time-saving. This was an efficient solution to maintain a safe and balanced hospital environment.

Differently from the previous report from March and April 2020, SDU worked more as a high dependency unit (HDU), at a semi-intensive care level, more complex than a common step-down unit (6). Furthermore, 8 patients were transferred from ICUC19 to SDU without requiring invasive ventilation; of the 41 patients admitted in SDU, only 11 needed escalation to ICUC19 for higher monitoring or orotracheal intubation; 34 patients were admitted directly from the emergency department (ED) to SDU. These data seem to testify to the high intensity of care reached in SDU at this third wave.

A limitation of this report is that, by its nature of case study, it is not matched with a comparative system. Moreover, at first superficial sight, the employment of intensivists in GWC19 and SDU might seem a waste of resources. In our experience, this has allowed many physicians to cyclically work at a lower intensity, periodically decompressing from the stress and pressure of a year in an ICUC19, interacting with conscious patients experiencing better outcomes, thus reducing burnout problems (7).

A further limitation of this system is that it worked in our specific context, whereas, it might not be applicable for hospitals acting as referral centers for a much wider general population and it might also not be applicable to regions where the incidence rate is much higher, determining a dramatic pandemic wave.

The model of differential intensity for hospital care management (high-intensity for ICU, medium-intensity for SDU, and low-intensity for GW), handled by a single intensive care unit, determined a sort of independence of the 4th floor from the hospital. The 4th floor was able to admit COVID-19 patients from other units/floors as needed from their clinical status evaluated by a consultant, but internally there was no need for hospital bed-manager coordination, counseling requests, bureaucracy, and time-wasting procedures.

The use of a COVID-19 “critical floor” from the general ward to ICU is an example of system adaptability. The effort made by intensivists was useful for patients in terms of quality of care and doctors in terms of occupational stress and mental health.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

VA conceived the study and wrote the article. EG, AC, CM, DS, and GBo worked in COVID-19 ICU and wards and helped to write the article. GBa, MS, and PC coordinated the nursing staff in the management of the ward. LM, FC, CLu, MA, CLa, and VP collaborated to review the manuscript. ER helped to write the manuscript and provided supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors thank all the colleagues (physicians, nurses, and healthcare operators) who cannot be mentioned in this article, who bravely and restlessly collaborated to face this year of COVID-19 pandemic.

ICU, Intensive Care Unit; SDU, Step-Down Unit; PPNR, Patient-Per-Nurse Ratio; HFNC, High Flow Nasal Cannulae; SARS-CoV-2, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2; SpO2, Oxygen Saturation; GWC19, General Ward Covid-19; LOS, Length-Of-Stay; SD, Standard Deviation; ICUC19, Intensive Care Unit Covid-19; ICUno−C19, Intensive Care Unit No Covid-19; HDU, High Dependency Unit; ED, Emergency Department.

1. Agnoletti V, Russo E, Circelli A, Benni M, Bolondi G, Martino C, et al. From intensive care to step-down units: managing patients throughput in response to COVID-19. Int J Qual Health Care. (2021) 33:mzaa091. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzaa091

2. Yetmar ZA, Issa M, Munawar S, M Burton MC, Pureza V, Sohail MR, et al. Inpatient care of patients with COVID-19: a guide for hospitalists. Am J Med. (2020) 133:1019–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.03.041

3. COVID-19: indicazioni per la durata e il termine dell'isolamento e della quarantena. Available online at: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioNotizieNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=5117.

4. Taniguchi Y, Kuno T, Komiyama J, Adomi M, Suzuki T, Abe T, et al. Comparison of patient characteristics and in-hospital mortality between patients with COVID-19 in 2020 and those with influenza in 2017-2020: a multicenter, retrospective cohort study in Japan. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. (2022) 20:100365. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100365

5. Borman AM, Fountain H, Guy R, Casale E, Gerver SM, Elgohari S, et al. Increased mortality in COVID-19 patients with fungal co- and secondary infections admitted to intensive care or high dependency units in NHS hospitals in England. J Infect. (2022) 4. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.12.047. [Epub ahead of print].

6. Solberg BC, Dirksen CD, Nieman FH, van Merode G, Ramsay G, Roekaerts P, et al. Introducing an integrated intermediate care unit improves ICU utilization: a prospective intervention study. BMC Anesthesiol. (2014) 14:76. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-14-76

Keywords: COVID-19, intensive care unit, high dependency unit, step-down unit, hospital admission criteria, bed management, bed occupancy rate, patients throughput

Citation: Agnoletti V, Gamberini E, Circelli A, Martino C, Santonastaso DP, Bolondi G, Bastoni G, Spiga M, Ceccarelli P, Montaguti L, Catena F, Poletti V, Lusenti C, Lazzari C, Altini M and Russo E (2022) Description of an Integrated and Dynamic System to Efficiently Deal With a Raging COVID-19 Pandemic Peak. Front. Med. 9:819134. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.819134

Received: 20 November 2021; Accepted: 14 February 2022;

Published: 18 March 2022.

Edited by:

Ornella Piazza, University of Salerno, ItalyReviewed by:

Rosalba Romano, Hospital Antonio Cardarelli, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Agnoletti, Gamberini, Circelli, Martino, Santonastaso, Bolondi, Bastoni, Spiga, Ceccarelli, Montaguti, Catena, Poletti, Lusenti, Lazzari, Altini and Russo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vanni Agnoletti, dmFubmkuYWdub2xldHRpQGF1c2xyb21hZ25hLml0

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.