95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Med. , 08 March 2022

Sec. Pathology

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.818728

We propose an initial explanation for how myalgic encephalomyelitis / chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) could originate and perpetuate by drawing on findings from critical illness research. Specifically, we combine emerging findings regarding (a) hypoperfusion and endotheliopathy, and (b) intestinal injury in these illnesses with our previously published hypothesis about the role of (c) pituitary suppression, and (d) low thyroid hormone function associated with redox imbalance in ME/CFS. Moreover, we describe interlinkages between these pathophysiological mechanisms as well as “vicious cycles” involving cytokines and inflammation that may contribute to explain the chronic nature of these illnesses. This paper summarizes and expands on our previous publications about the relevance of findings from critical illness for ME/CFS. New knowledge on diagnostics, prognostics and treatment strategies could be gained through active collaboration between critical illness and ME/CFS researchers, which could lead to improved outcomes for both conditions.

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) is a debilitating illness that affects millions of people worldwide (an estimated 800,000 to 2.5 million in the USA) (1, 2). Impaired function, post-exertional malaise, and unrefreshing sleep are core symptoms (1, 3, 4). At least one-quarter of ME/CFS patients are house- or bedbound at some point in their lives (1); the illness can be completely incapacitating (5). The etiology of the illness is unclear (6, 7) and peri-onset events include infection-related episodes, stressful incidents, and exposure to environmental toxins (8).

Critical illness refers to the physiological response to virtually any severe injury or infection, such as head injury, burns, cardiac surgery, SARS-CoV-2 infection and heat stroke (9). Researchers make a distinction between the acute phase of critical illness—in the first hours or days following severe trauma or infection; and the chronic or prolonged phase—in the case of patients who survive the acute phase but for unknown reasons do not start recovering and continue to require intensive care (10–13). Regardless of the initial injury or infection, these “chronic Intensive Care Unit (ICU) patients” experience profound muscular weakness, cognitive impairment, pain, vulnerability to infection, etc. (9, 11, 14). The treatment of prolonged critical illness is incomplete and remains an active area of research. Moreover, cognitive and/or physical disability can last for months or even years after treatment in ICUs (i.e., post intensive care syndrome, PICS) for as of yet unexplained reasons (15–17).

Drawing on findings from critical illness, we here propose an initial explanation for how ME/CFS could originate and perpetuate. Specifically, we combine emerging findings regarding (a) hypoperfusion and endotheliopathy, and (b) intestinal injury in these illnesses with our previously published hypothesis about the role of (c) pituitary suppression, and (d) low thyroid hormone function associated with redox imbalance in ME/CFS. Moreover, we describe interlinkages between these pathophysiological mechanisms as well as “vicious cycles” involving cytokines and inflammation that may contribute to explain the chronic nature of these illnesses. This explanation summarizes and expands on our previous publications about the relevance of findings from critical illness for ME/CFS (18–20) and builds on the work by Nacul et al. (21). The general lack of large high-quality ME/CFS studies (a reflection of the lack of funding in this field) poses a challenge for the assessment of overlaps between the two conditions.

In the following sections we describe four central pathophysiological mechanisms in critical illness, including their relationship to inflammation. We also provide initial arguments for suggesting that similar mechanisms may underlie ME/CFS. Readers are referred to our prior publications for additional details about these mechanisms in critical illness (including heat stroke) and possible lessons for understanding ME/CFS (18–20).

It has long been suggested that inadequate oxygen circulation is central to critical illness (22). Specifically, the redistribution of blood away from the splanchnic area to critical tissues is considered an adaptive androgenic response to physiological stress (23, 24). However, the resulting ischemia / reperfusion (I/R) can contribute to tissue injury driving sepsis and multi-organ dysfunction (25, 26). The relative importance of reduced blood flow, vasoconstriction (27), capillary flow disturbances (28) and impaired cellular oxygen utilization (29, 30) in driving critical illness continues to be debated.

Endothelial dysfunction appears to occur in parallel with circulation disturbances during critical illness. Probable drivers of distortions in the structure and function of endothelial lining (i.e., glycocalyx) are cytokines (31), inflammation, exposure to oxidative stress (28, 32) and/or sympatho-adrenal hyperactivation (33). Crucially, endothelial dysfunction during critical illness has been associated with altered cerebral blood flow (34, 35) and increased blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability resulting in long-term cognitive impairment (36, 37). A leaky BBB could also contribute to increased intracranial pressure (38, 39). Finally, researchers have found that endotheliopathy and coagulation disorder bolster each other via inflammatory pathways (40). Coagulation abnormalities vary in critical illness, but coagulopathy is associated with unfavorable outcomes in prolonged critical illness (i.e., length of ICU stay and mortality) (41).

We propose that similar alterations of the vascular system in response to a physical, infectious and / or emotional stressor (i.e., physiological insult) may also contribute to explain the emergence of ME/CFS. This is consistent with recent hypotheses describing vasoconstriction in muscle and brain as a principal element of ME/CFS (42–46), and findings of cerebral hypoperfusion (47–49) and intracranial hypertension (50) in ME/CFS patients. It is also consistent with studies that have shown that endothelial function is impaired in ME/CFS (51, 52), both in large vessels and in the microcirculation (53, 54)—associated with redox imbalance (51). Finally, it is consistent with a new hypothesis for ME/CFS which suggests that endothelial senescence underpins ME/CFS by disrupting the intestinal barriers and BBBs (55), as well as with suggestions that leakage from dysfunctional blood vessels could explain many of the symptoms in ME/CFS (56).

Critical illness researchers have found profound intestinal alterations within hours following a physiological insult: a dramatic shift in the composition and virulence of intestinal microbes (57–59), an erosion of the mucus barrier, an increase in the permeability of the gut (i.e., “leaky gut”) (60–62), and a disruption in gut motility (63). This intestinal injury is thought to be largely a consequence of local I/R and redox imbalance resulting from splanchnic hypoperfusion (58, 61, 64–67). Indeed, studies in the field of exercise immunology have shown that even relatively low levels of splanchnic hypoperfusion during exercise result in intestinal injury (68).

Critically, this intestinal injury may lead to bacterial translocation from the gut into circulation (i.e., endotoxemia) and/or the formation of toxic gut-derived lymph (57, 60). This in turn can induce pro-inflammatory cytokines and systemic inflammation (69, 70). Moreover, changes in the intestinal microbiome or the mucus barrier may also impact the immune system directly (57). Thus, researchers have long considered the gut “the motor of critical illness” driving sepsis and distant organ dysfunction (71). Some have suggested that a self-perpetuating vicious inflammatory cycle centered around intestinal injury can hinder recovery from critical illness (61, 72).

We propose that the sequence during critical illness—from splanchnic hypoperfusion to hypoxia, redox imbalance, altered gut microbiome, intestinal injury, gut-related endotoxemia, pro-inflammatory cytokines and systemic inflammatory—may also contribute to explain the emergence of ME/CFS following a physiological insult. Our proposal is in alignment with others' findings that intestinal injury and resulting inflammation are central to ME/CFS (73–81) and consistent with findings linking the gut microbiome to inflammation (82–85) and to fatigue symptoms in ME/CFS (86). If verified, the existence of a vicious inflammatory cycle centered around intestinal injury could contribute to explain the perpetuation of ME/CFS. Post-exertional malaise—a key symptom of ME/CFS—could be the manifestation of an accentuation in intestinal injury following exertion. Moreover, the translocation of gut microbes or toxin from the intestines to the brain (55) might contribute to explain central nervous system inflammation in ME/CFS (87–89). Finally, leaky gut is also associated with auto-immunity (90, 91)—an important factor in ME/CFS pathology (92–94).

Almost immediately after a physiological insult, endocrine axes experience profound alterations considered a vital response to severe stress or injury to allow for a shift in energy and resources to essential organs and repair (95–97). Whereas, in critically ill patients who begin to recover, endocrine axes essentially normalize within 28 days of illness, in cases of prolonged critical illness the pituitary's pulsatile secretion of tropic hormones (unexpectedly) remains suppressed.

Why and how this central suppression is maintained in prolonged critical illness continues to be debated. Inflammatory pathways likely play a role irrespective of the nature of the original injury or infection. For example, cytokines increase the abundance and affinity of glucocorticoid receptors (GR) at the level of the hypothalamus / pituitary, thereby enhancing the negative feedback loop of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and consequently suppressing pituitary release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) (95, 98). Similarly, cytokines up-regulate deiodinase enzymes in the hypothalamus resulting in higher local levels of the active thyroid hormone (T3), thereby enhancing the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis' negative feedback loop and consequently suppressing pituitary secretion of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) irrespective of circulating thyroid hormone concentrations (99–101). Cytokines may also suppress the release of TSH by the pituitary directly (102, 103) contributing to a virtual complete loss of pulsatile TSH secretion (96).

The loss of pulsatile pituitary secretions has important implications for the autonomic nervous system, metabolism, and the immune system. Without sufficient pulsatile stimulation by ACTH, adrenal glands begin to atrophy (104, 105), compromising patients' ability to cope with external stressors and permitting excessive inflammatory responses. Erratic rather than pulsatile pituitary production of growth hormone (GH) leads to an imbalance between catabolic and anabolic hormones, resulting in loss of muscle and bone mass, muscle weakness, and changes in glucose and fat metabolism (106–108). Finally, suppression of the HPT axis is associated with tiredness and other hypothyroid-like symptoms (109, 110).

We propose that the sequence during critical illness—from increased release of pituitary hormones during the acute phase to suppression of the pituitary gland's pulsatile secretion in the prolonged phase—could also contribute to explain the emergence of ME/CFS following a physiological insult. This proposal is consistent with descriptions of ME/CFS as a progression from a hypermetabolic to hypometabolic state (21). It also aligns with a recent hypothesis relating many of the symptoms in severe ME/CFS to impaired pituitary function (111). Further support for this proposal is provided by the many previous ME/CFS studies that have documented dysfunctions in the hypothalamic–pituitary–somatotropic (HPS) axis (112–114), the HPT axis (115–120), and the HPA axis (121–136)—notably associated with inflammation and oxidative & nitrosative stress (O&NS) (137–140). Strikingly, models relating the persistence of a suppressed HPA axis in ME/CFS to a change in central GRs concentrations resemble the explanations provided for pituitary suppression in critical illness (141–146). Moreover, suppression of ACTH release would explain why in a small study ME/CFS patients were found to have 50% smaller adrenals than controls (147), resembling adrenal atrophy in prolonged critical illness. However, the relationship between the pituitary's pulsatile secretions, physiological alterations and severity of illness—which proved revelatory in understanding prolonged critical illness—remains unexplored in ME/CFS.

Peripheral mechanisms involving cytokines lead to the rapid depression of thyroid hormone activity following a severe physiological insult (148–152). This is termed “non-thyroidal illness syndrome” (NTIS), “euthyroid sick syndrome” or “low T3 syndrome” and is thought to be an adaptive response to conserve energy resources during critical illness (152–154). The mechanisms involved include alterations in the half-life of thyroid hormone in circulation (155–157); modifications in the uptake of thyroid hormone by cells (158, 159); down- and up-regulation of deiodinase enzymes that convert the thyroid hormone into active and inactive forms respectively (156, 160); and alterations in sensitivity of cells to thyroid hormones (161–163). These alterations can lead to important tissue-specific depression in thyroid hormone function (164, 165) which is, however, often missed altogether in clinical settings (166) because most of the alterations do not translate into changes in the blood concentrations of thyroid hormones (164, 167, 168). Indeed, the decrease in the ratio of the active form of thyroid hormone (T3) relative to the inactivated thyroid hormone (rT3) (150, 152, 169)—considered the most sensitive marker of NTIS—may be just the “tip of the iceberg” of the depressed thyroid hormone function in target tissues (120, 170).

While NTIS may be beneficial in the acute phase of critical illness, it is increasingly seen as maladaptive and hampering the recovery of patients in the case of prolonged critical illness (96, 101, 152, 169, 171–173). Low thyroid hormone function may hamper the function of organs (170) and the activity of immune cells, including natural killer cells (174–185). Immune dysfunctions might in turn explain other pathologies, such as viral reactivation observed in ICU patients (186–188). Some critical illness researchers have proposed a model that describes how NTIS is maintained by reciprocal relationships between inflammation (notably pro-inflammatory cytokines), O&NS and reduced thyroid hormone function, forming a “vicious cycle” (101, 173). This model can help to explain the perplexing failure to recover of some critically ill patients in ICUs that survive their initial severe illness or injury.

We propose that low thyroid hormone function could also contribute to explain the emergence of ME/CFS following a physiological insult. An immune-mediated loss of thyroid hormone function in ME/CFS has long been suspected (117). A recent study showed that the thyroid panel of ME/CFS patients resembles that of critical illness patients, including significantly lower ratio of T3 to rT3 hormones (120). Moreover, the other elements for a “vicious cycle” which researchers have suggested perpetuate a hypometabolic and inflammatory state in critical illness are also present in ME/CFS, including inflammation (140, 189), increased O&NS (190–192) and altered cytokine profiles (193, 194).

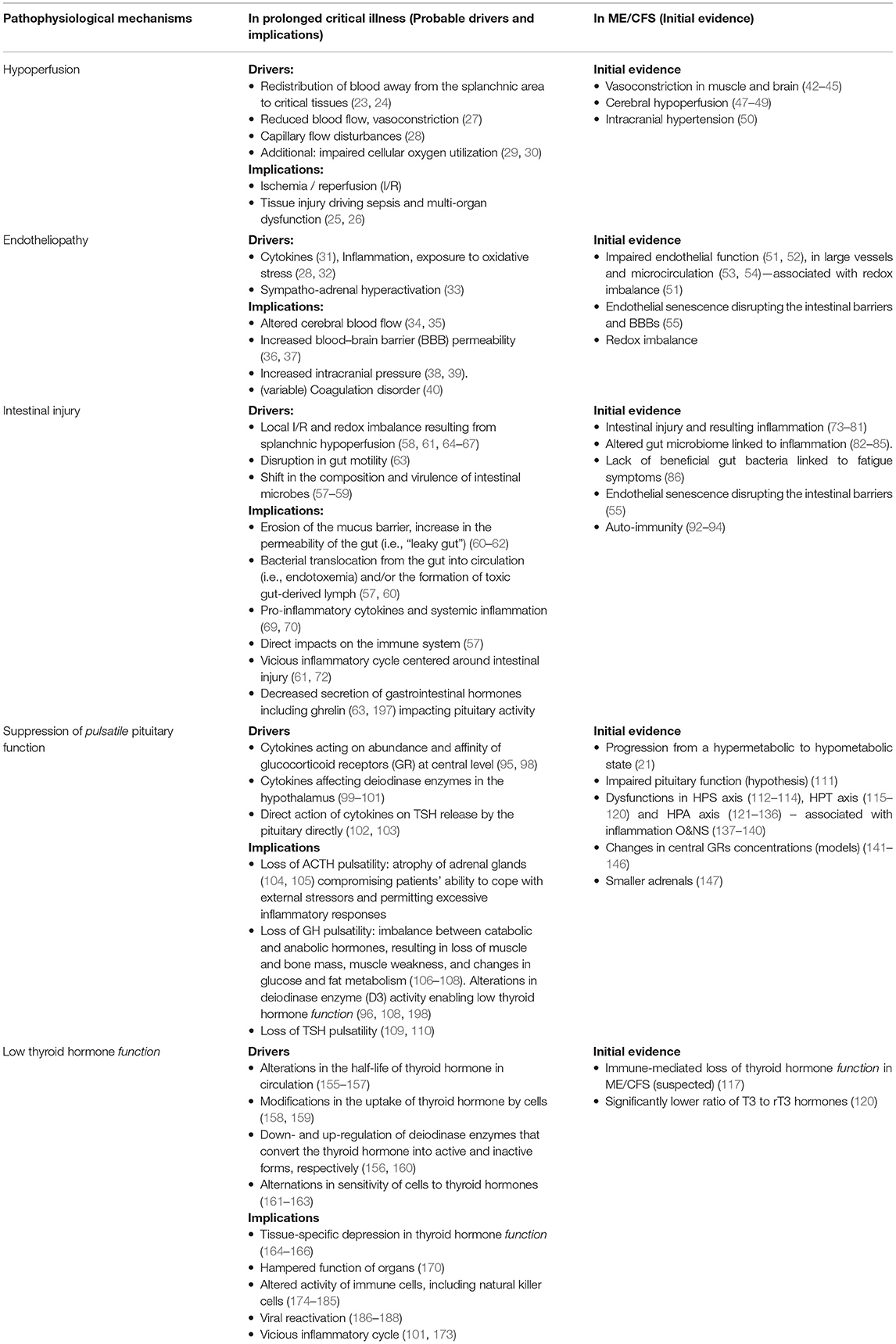

Hypoperfusion and endotheliopathy, intestinal injury, pituitary suppression, and low thyroid hormone function are each central to prolonged critical illness regardless of the nature of the initial severe injury or infection (101, 173, 195, 196). We propose that, similarly, these mechanisms and their reciprocal relationships with inflammation could underlie ME/CFS regardless of the nature of the peri-onset event (i.e., infection, stressful incident, exposure to environmental toxins or other) (Table 1). Moreover, the severity of ME/CFS may be a function of the strength of these mechanisms.

Table 1. Central pathophysiological mechanisms in prolonged critical illness, probable drivers and implications, and initial evidence suggesting similar mechanisms in ME/CFS.

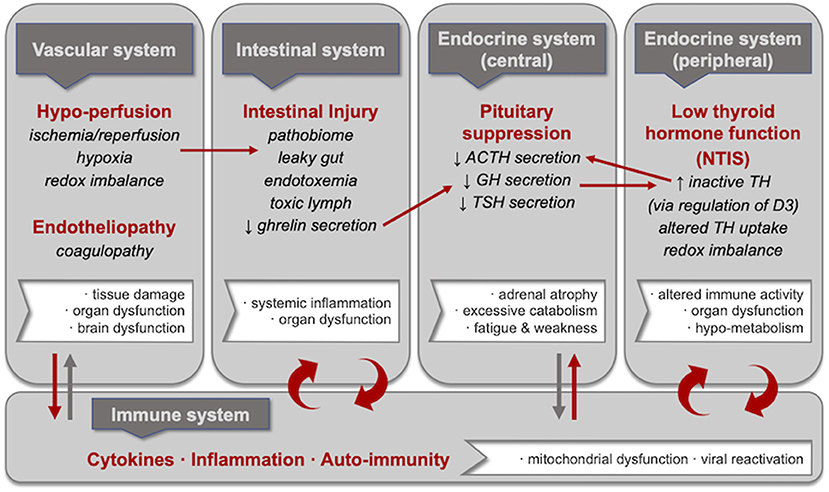

However, each of these pathological mechanisms has largely been studied in isolation and rarely have the linkages between them been explored. Yet, the aggregate of these mechanisms is likely necessary to fully explain the perpetuation of critical illness—and to inform the understanding of ME/CFS (Figure 1). Additional areas for inquiry thus include the following:

Figure 1. Central pathophysiological mechanisms in critical illness including selected consequences and inter-linkages. Hypoperfusion and endotheliopathy, intestinal injury, pituitary suppression, and low thyroid hormone function are each central to prolonged critical illness regardless of the nature of the initial severe injury or infection. These pathophysiological mechanisms are in reciprocal relationships with inflammation; specifically, researchers have proposed vicious cycles involving intestinal injury and low thyroid hormone function. Moreover, linkages have been described between these pathophysiological mechanisms, including (i) hypoperfusion and intestinal injury (i.e., leaky gut resulting from ischemia/reperfusion, hypoxia and redox imbalance); (ii) intestinal injury and pituitary suppression (i.e., suppressed growth hormone release resulting from reduced ghrelin secretion by the intestines); (iii) pituitary suppression and low thyroid hormone function (i.e., increased inactivated thyroid hormone resulting from the upregulation of D3 deiodinase as a consequence of lower growth hormone); and (iv) low thyroid hormone function and pituitary suppression (i.e., decreased ACTH secretion resulting from lower levels of activated thyroid hormone). We propose that these mechanisms and the linkages between them—alongside reciprocal relationships with inflammation—could also underlie ME/CFS.

Intestinal injury during critical illness results in decreased secretion of gastrointestinal hormones including ghrelin (63, 197). Decreased stimulation of the pituitary and hypothalamus by ghrelin during prolonged critical illness in turn results in lower secretion of GH by the pituitary (199). Researchers have found that the administration of an artificial ghrelin in chronic ICU patients reactivated the pulsatile secretion of GH by the pituitary and—when done in combination with thyrotropin-releasing hormones (TRH)—had beneficial metabolic effects (96, 108, 198). Similarly, the administration of ghrelin to the I/R rats “inhibited pro-inflammatory cytokine release, reduced neutrophil infiltration, ameliorated intestinal barrier dysfunction, attenuated organ injury, and improved survival” (200). The sequence between intestinal injury, ghrelin secretion and GH release by the pituitary could be particularly relevant for solving ME/CFS given that “several of the main typical symptoms in severe ME/CFS, such as fatigue, myalgia, contractility, delaying muscle recovery and function, exertional malaise, neurocognitive dysfunction, and physical disability may be related to severe GH deficiency” (111).

There are several pathways linking the activity of the pituitary with that of thyroid hormones. Firstly, GH secreted by the pituitary co-regulates the activity of the deiodinase enzyme (D3) responsible for the conversion of thyroid hormones into inactive forms (i.e., rT3 and inactivate forms of T2) (106, 201). Researchers showed that normalization of the GH secretion in prolonged critically ill patients is necessary to inhibit the increase in plasma rT3 concentrations (96, 108, 198). In other words, dampened GH release by the pituitary during prolonged critical illness enables low thyroid hormone function. Secondly, the lack of stimulation of the adrenals by ACTH could (by causing an atrophy of adrenals) create the condition necessary for persistent inflammation which depresses the activity of thyroid hormones during critical illness (148–152). In other words, dampened ACTH release by the pituitary during prolonged critical illness might permit the vicious inflammatory cycles described above. Thirdly, there is evidence that thyroid hormone conversely also stimulates ACTH secretion (202, 203). In summary, the bi-directional relationships between the endocrine axes and thyroid hormone function (in addition to reciprocal relationships with inflammation) could contribute to explain the persistence of chronic ICU and ME/CFS.

Upon binding to specific receptors on endothelial cells, thyroid hormones (T3 and T4) activate the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) responsible for nitric oxide (NO) production (204), which in turn impacts vasodilation and inflammation (205–207). A further line of inquiry may thus be the role of thyroid hormone function in endotheliopathy in ME/CFS, including as it relates to the new finding that plasma from ME/CFS patients inhibits eNOS and NO production in endothelial cells (208). Relatedly, critical illness researchers have found that serum from patients with NTIS inhibits the uptake of thyroid hormone (209, 210); the mechanisms remain unresolved (165).

The impaired perfusion, redox imbalance, lower thyroid hormone function and inflammation appear to collectively affect mitochondrial activity in critical illness (via inhibition, damage, and/or decreased turnover of new mitochondrial protein) (30, 211–213). Mitochondrial activity may be similarly affected in ME/CFS (190). Some have suggested that this down-regulation of mitochondrial activity (and oxygen utilization) in critical illness may be an adaptive form of “hibernation” to protect cells from death pathways (30, 213). This suggestion echoes the hypothesis that ME/CFS is a form of “dauer” or “cell danger response” (214–216). Lower mitochondrial activity in turn affects the immune system and the gut endothelial “such that the host's immune response and physical barriers to infection are simultaneously compromised” (29).

Although prolonged critical illness remains unresolved, early treatment trials—such as the reactivation of the pituitary, or interruption of the vicious inflammatory cycles centered around either gut injury or low thyroid hormone function—may provide therapeutic avenues for ME/CFS (19). Longitudinal studies of (spontaneous) recovery from critical illness may also give clues about prerequisites for recovery from ME/CFS. Researchers have, for example, found that “supranormal TSH precedes onset of recovery” from prolonged critical illness (96) and that metabolic rate rises > 50% above normal in the recovery phase (213).

Researchers have suggested commonality in the illnesses induced by physical, infectious, and / or emotional stressors (132, 217). These include heat stroke, fibromyalgia, ME/CFS, prolonged critical illness, PICS, cancer-related fatigue, post-viral fatigue, post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PACS) and long-COVID. Specifically, it is necessary to explore whether the pathological mechanisms described above also underlie long COVID—a disease which resembles ME/CFS (218–228) and can arise even after mild COVID-19 cases.

Decades of research in the field of critical illness medicine have demonstrated that in response to the stress of severe infection or injury, the vascular system, intestines, endocrine axes and thyroid hormone function experience profound alterations. Self-reinforcing interlinkages between these pathophysiological mechanisms as well as “vicious cycles” involving cytokines and inflammation may perpetuate illness irrespective of the initial severe infection or injury. Without excluding possible predisposing genetic or environmental factors, we propose that the pathological mechanisms—and the interlinkages between them—that prevent recovery of some critically ill patients may also underlie ME/CFS. This initial proposal is in line with and complements several existing hypotheses of ME/CFS pathogenesis. If this hypothesis is validated, past treatment trials for critical illness may provide avenues for a cure for ME/CFS. Certainly, given the similarities described above, active collaboration between critical illness and ME/CFS researchers could lead to improved understanding of not only both conditions, but also PICS, long-COVID, PACS, and fibromyalgia.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

DS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

The Open Medicine Foundation (JB) is acknowledged for support.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

BBB, Blood–brain barrier; ACTH, Adrenocorticotropic hormone; GH, Growth hormone; GR, glucocorticoid receptors; HPA, hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis: “Adreno-cortical axis”; HPS, Hypothalamic-pituitary-somatotropic axis: “Somatropic axis”; HPT, Hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid: “Thyrotropic axis”; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; I/R, Ischemia/reperfusion; ME/CFS, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome; NO, Nitrox oxide; NTIS, Non-thyroidal illness syndrome; O&NS, oxidative and nitrosative stress; PACS, Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome; PICS, Post-intensive care syndrome; TRH, Thyrotropin-releasing hormone; TSH, Thyroid stimulating hormone.

1. Institute of Medicine. Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press (2015).

2. Jason LA, Mirin AA. Updating the National Academy of Medicine ME/CFS prevalence and economic impact figures to account for population growth and inflation. Fatigue Biomed Health Behav. (2021) 9:9–13. doi: 10.1080/21641846.2021.1878716

3. Open Medicine Foundation,. Symptoms of ME/CFS. (2020). Available online at: https://www.omf.ngo/symptoms-mecfs (accessed March 27, 2021).

4. Nacul L, Authier FJ, Scheibenbogen C, Lorusso L, Helland IB, Martin JA, et al. European Network on Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (EUROMENE): expert consensus on the diagnosis, service provision, and care of people with ME/CFS in Europe. Medicina. (2021) 57:510. doi: 10.3390/medicina57050510

5. Dafoe W. Extremely severe ME/CFSra personal account. Healthcare. (2021) 9:504. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9050504

6. Komaroff AL. Advances in understanding the pathophysiology of chronic fatigue syndrome. JAMA. (2019) 322:499–500. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.8312

7. Komaroff AL. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: when suffering is multiplied. Healthcare. (2021) 9:919. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9070919

8. Chu L, Valencia IJ, Garvert DW, Montoya JG. Onset patterns and course of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Front Pediatr. (2019) 7:12. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00012

9. Loss SH, Nunes DSL, Franzosi OS, Salazar GS, Teixeira C, Vieira SRR. Chronic critical illness: are we saving patients or creating victims? Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. (2017) 29:87–95. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20170013

10. Van den Berghe G. Novel insights into the neuroendocrinology of critical illness. Eur J Endocrinol. (2000) 143:1–13. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1430001

11. Nelson JE, Cox CE, Hope AA, Carson SS. Chronic critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2010) 182:446–44610espir C1164/rccm.201002-0210CI

12. Van den Berghe GH. Acute and prolonged critical illness are two distinct neuroendocrine paradigms. Verh K Acad Geneeskd Belg. (1998) 60:487–518; discussion −20.

13. Vanhorebeek I, Van den Berghe G. The neuroendocrine response to critical illness is a dynamic process. Crit Care Clin. (2006) 22:1–15, v. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2005.09.004

14. Vanhorebeek I, Latronico N, Van den Berghe G. ICU-acquired weakness. Intensive Care Med. (2020) 46:637–53. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05944-4

15. Van Aerde N, Van Dyck L, Vanhorebeek I, Van den Berghe G. Endocrinopathy of the Critically Ill. In: Preiser J-C, Herridge M, Azoulay E, editors. Post-Intensive Care Syndrome. Cham: Springer International Publishing (2020). p. 125–43.

16. Rawal G, Yadav S, Kumar R. Post-intensive care syndrome: an overview. J Transl Int Med. (2017) 5:90–2. doi: 10.1515/jtim-2016-0016

17. Smith S, Rahman O. Post Intensive Care Syndrome. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing (2020).

18. Stanculescu D, Larsson L, Bergquist J. Hypothesis: mechanisms that prevent recovery in prolonged ICU patients also underlie Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Front Med. (2021) 8:628029. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.628029

19. Stanculescu D, Larsson L, Bergquist J. Theory: treatments for prolonged ICU patients may provide new therapeutic avenues for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). Front Med. (2021) 8:672370. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.672370

20. Stanculescu D, Sepulveda N, Lim CL, Bergquist J. Lessons from heat stroke for understanding Myalgic Encephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:789784. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.789784

21. Nacul L, O'Boyle S, Palla L, Nacul FE, Mudie K, Kingdon CC, et al. How Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) progresses: the natural history of ME/CFS. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:826. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00826

22. Broder G, Weil MH. Excess lactate: an index of reversibility of shock in human patients. Science. (1964) 143:1457–9. doi: 10.1126/science.143.3613.1457

23. Halter JB, Pflug AE, Porte D. Jr. Mechanism of plasma catecholamine increases during surgical stress in man. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1977) 45:936–44. doi: 10.1210/jcem-45-5-936

24. Zhang D, Li H, Li Y, Qu L. Gut rest strategy and trophic feeding in the acute phase of critical illness with acute gastrointestinal injury. Nutr Res Rev. (2019) 32:176–82. doi: 10.1017/S0954422419000027

25. Rock P, Yao Z. Ischemia reperfusion injury, preconditioning and critical illness. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. (2002) 15:139–46. doi: 10.1097/00001503-200204000-00001

26. Schwarte L, Stevens M, Ince C. Splanchnic perfusion and oxygenation in critical illness. Intensive Care Med. (2006) 627–40. doi: 10.1007/3-540-33396-7_58

27. Pastores SM, Katz DP, Kvetan V. Splanchnic ischemia and gut mucosal injury in sepsis and the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. (1996) 91:1697–6979

28. Ostergaard L, Granfeldt A, Secher N, Tietze A, Iversen NK, Jensen MS, et al. Microcirculatory dysfunction and tissue oxygenation in critical illness. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. (2015) 59:1246–59. doi: 10.1111/aas.12581

29. Crouser ED. Mitochondrial dysfunction in septic shock and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Mitochondrion. (2004) 4:729–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2004.07.023

30. Singer M. The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in sepsis-induced multi-organ failure. Virulence. (2014) 5:66–72. doi: 10.4161/viru.26907

31. Kang S, Kishimoto T. Interplay between interleukin-6 signaling and the vascular endothelium in cytokine storms. Exp Mol Med. (2021) 53:1116–23. doi: 10.1038/s12276-021-00649-0

32. Cerny V, Astapenko D, Brettner F, Benes J, Hyspler R, Lehmann C, et al. Targeting the endothelial glycocalyx in acute critical illness as a challenge for clinical and laboratory medicine. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. (2017) 54:343–57. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2017.1379943

33. Johansson PI, Stensballe J, Ostrowski SR. Shock induced endotheliopathy (SHINE) in acute critical illness - a unifying pathophysiologic mechanism. Crit Care. (2017) 21:25. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1605-5

34. Slessarev M, Mahmoud O, McIntyre CW, Ellis CG. Cerebral blood flow deviations in critically ill patients: potential insult contributing to ischemic and hyperemic injury. Front Med. (2020) 7:615318. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.615318

35. Bowton DL, Bertels NH, Prough DS, Stump DA. Cerebral blood flow is reduced in patients with sepsis syndrome. Crit Care Med. (1989) 17:399–39989are Medo1097/00003246-198905000-00004

36. Hughes CG, Patel MB, Brummel NE, Thompson JL, McNeil JB, Pandharipande PP, et al. Relationships between markers of neurologic and endothelial injury during critical illness and long-term cognitive impairment and disability. Intensive Care Med. (2018) 44:345–55. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5120-1

37. Hughes CG, Morandi A, Girard TD, Riedel B, Thompson JL, Shintani AK, et al. Association between endothelial dysfunction and acute brain dysfunction during critical illness. Anesthesiology. (2013) 118:631–9. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31827bd193

38. Schizodimos T, Soulountsi V, Iasonidou C, Kapravelos N. An overview of management of intracranial hypertension in the intensive care unit. J Anesth. (2020) 34:741–57. doi: 10.1007/s00540-020-02795-7

39. Naessens DMP, de Vos J, VanBavel E, Bakker E. Blood-brain and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier permeability in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Fluids Barriers CNS. (2018) 15:26. doi: 10.1186/s12987-018-0112-7

40. Vallet B, Wiel E. Endothelial cell dysfunction and coagulation. Crit Care Med. (2001) 29:S36–41. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107001-00015

41. Winer LK, Salyer C, Beckmann N, Caldwell CC, Nomellini V. Enigmatic role of coagulopathy among sepsis survivors: a review of coagulation abnormalities and their possible link to chronic critical illness. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. (2020) 5:e000462. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2020-000462

42. Wirth KJ, Scheibenbogen C. Pathophysiology of skeletal muscle disturbances in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). J Transl Med. (2021) 19:162. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-02833-2

43. Wirth K, Scheibenbogen C A. Unifying hypothesis of the pathophysiology of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): recognitions from the finding of autoantibodies against ßc-adrenergic receptors. Autoimmun Rev. (2020) 19:102527. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102527

44. Malato J, Sotzny F, Bauer S, Freitag H, Fonseca A, Grabowska AD, et al. The SARS-CoV-2 receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a meta-analysis of public DNA methylation and gene expression data. Heliyon. (2021) 7:e07665. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07665

45. Fluge O, Tronstad KJ, Mella O. Pathomechanisms and possible interventions in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). J Clin Invest. (2021) 131:e150377. doi: 10.1172/JCI150377

46. Wirth KJ, Scheibenbogen C, Paul F. An attempt to explain the neurological symptoms of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. J Transl Med. (2021) 19:471. doi: 10.1186/s12967-021-03143-3

47. Campen C, Rowe PC, Visser FC. Orthostatic symptoms and reductions in cerebral blood flow in Long-Haul COVID-19 patients: similarities with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Medicina. (2021) 58:28. doi: 10.3390/medicina58010028

48. van Campen C, Visser FC. Psychogenic pseudosyncope: real or imaginary? Results from a case-control study in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) patients. Medicina. (2022) 58:98. doi: 10.3390/medicina58010098

49. van Campen CMC, Verheugt FWA, Rowe PC, Visser FC. Cerebral blood flow is reduced in ME/CFS during head-up tilt testing even in the absence of hypotension or tachycardia: A quantitative, controlled study using Doppler echography. Clinical Neurophysiol Pract. (2020) 5:50–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cnp.2020.01.003

50. Bragee B, Michos A, Drum B, Fahlgren M, Szulkin R, Bertilson BC. Signs of intracranial hypertension, hypermobility, and craniocervical obstructions in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:828. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00828

51. Blauensteiner J, Bertinat R, Leon LE, Riederer M, Sepulveda N, Westermeier F. Altered endothelial dysfunction-related miRs in plasma from ME/CFS patients. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:10604. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89834-9

52. Scherbakov N, Szklarski M, Hartwig J, Sotzny F, Lorenz S, Meyer A, et al. Peripheral endothelial dysfunction in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. ESC Heart Fail. (2020) 7:1064–71. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12633

53. Newton DJ, Kennedy G, Chan KK, Lang CC, Belch JJ, Khan F. Large and small artery endothelial dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome. Int J Cardiol. (2012) 154:335–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.10.030

54. Sorland K, Sandvik MK, Rekeland IG, Ribu L, Smastuen MC, Mella O, et al. Reduced endothelial function in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome-results from open-label cyclophosphamide intervention study. Front Med. (2021) 8:642710. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.642710

55. Sfera A, Osorio C, Zapata Martin Del Campo CM, Pereida S, Maurer S, Maldonado JC, et al. Endothelial senescence and chronic fatigue syndrome, a COVID-19 based hypothesis. Front Cell Neurosci. (2021) 15:673217. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2021.673217

56. Lubell J. Letter: could endothelial dysfunction and vascular damage contribute to pain, inflammation and post-exertional malaise in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)? J Transl Med. (2022) 20:40. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03244-7

57. Alverdy JC, Krezalek MA. Collapse of the Microbiome, Emergence of the Pathobiome, and the Immunopathology of Sepsis. Crit Care Med. (2017) 45:337–47. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002172

58. Otani S, Coopersmith CM. Gut integrity in critical illness. J Intensive Care. (2019) 7:17. doi: 10.1186/s40560-019-0372-6

59. Ojima M, Motooka D, Shimizu K, Gotoh K, Shintani A, Yoshiya K, et al. Metagenomic analysis reveals dynamic changes of whole gut microbiota in the acute phase of intensive care unit patients. Dig Dis Sci. (2016) 61:1628–34. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-4011-3

60. Mittal R, Coopersmith CM. Redefining the gut as the motor of critical illness. Trends Mol Med. (2014) 20:214–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.08.004

61. Sertaridou E, Papaioannou V, Kolios G, Pneumatikos I. Gut failure in critical care: old school versus new school. Ann Gastroenterol. (2015) 28:309–22.

62. Doig CJ, Sutherland LR, Sandham JD, Fick GH, Verhoef M, Meddings JB. Increased intestinal permeability is associated with the development of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome in critically ill ICU patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (1998) 158:444–51. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.2.9710092

63. Martinez EE, Fasano A, Mehta NM. Gastrointestinal function in critical illness—a complex interplay between the nervous and enteroendocrine systems. Pediatr Med. (2020) 3:26. doi: 10.21037/pm-20-74

64. Bischoff SC, Barbara G, Buurman W, Ockhuizen T, Schulzke JD, Serino M, et al. Intestinal permeability–a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. (2014) 14:189. doi: 10.1186/s12876-014-0189-7

65. Aranow J, Fink M. Determinants of intestinal barrier failure in critical illness. Br J Anaesth. (1996) 77:71–81. doi: 10.1093/bja/77.1.71

66. Jakob SM. Clinical review: splanchnic ischaemia. Crit Care. (2002) 6:306–12. doi: 10.1186/cc1515

67. Stechmiller JK, Treloar D, Allen N. Gut dysfunction in critically ill patients: a review of the literature. Am J Crit Care. (1997) 6:204–9. doi: 10.4037/ajcc1997.6.3.204

68. van Wijck K, Lenaerts K, van Loon LJ, Peters WH, Buurman WA, Dejong CH. Exercise-induced splanchnic hypoperfusion results in gut dysfunction in healthy men. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e22366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022366

69. Fink MP, Delude RL. Epithelial barrier dysfunction: a unifying theme to explain the pathogenesis of multiple organ dysfunction at the cellular level. Crit Care Clin. (2005) 21:177–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2005.01.005

70. Holland J, Carey M, Hughes N, Sweeney K, Byrne PJ, Healy M, et al. Intraoperative splanchnic hypoperfusion, increased intestinal permeability, down-regulation of monocyte class II major histocompatibility complex expression, exaggerated acute phase response, and sepsis. Am J Surg. (2005) 190:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.03.038

71. Meakins J, Marshall J. Multi-organ-failure syndrome. The gastrointestinal tract: the “motor” of MOF. Arch Surg. (1986) 121:196–208. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1986.01400020082010

72. Deitch EA. Gut-origin sepsis: evolution of a concept. Surgeon. (2012) 10:350–6. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2012.03.003

73. Maes M, Coucke F, Leunis JC. Normalization of the increased translocation of endotoxin from gram negative enterobacteria (leaky gut) is accompanied by a remission of chronic fatigue syndrome. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. (2007) 28:739–44.

74. Morris G, Berk M, Carvalho AF, Caso JR, Sanz Y, Maes M. The role of microbiota and intestinal permeability in the pathophysiology of autoimmune and neuroimmune processes with an emphasis on inflammatory bowel disease type 1 diabetes and chronic fatigue syndrome. Curr Pharm Des. (2016) 22:6058–75. doi: 10.2174/1381612822666160914182822

75. Morris G, Maes M, Berk M, Puri BK. Myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome: how could the illness develop? Metab Brain Dis. (2019) 34:385–415. doi: 10.1007/s11011-019-0388-6

76. Maes M, Mihaylova I, Leunis JC. Increased serum IgA and IgM against LPS of enterobacteria in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): indication for the involvement of gram-negative enterobacteria in the etiology of CFS and for the presence of an increased gut-intestinal permeability. J Affect Disord. (2007) 99:237–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.021

77. Zhang ZT, Du XM, Ma XJ, Zong Y, Chen JK Yu CL, et al. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in lipopolysaccharide-induced mouse fatigue and its relevance to chronic fatigue syndrome. J Neuroinflammation. (2016) 13:71. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0539-1

78. Maes M, Leunis JC. Normalization of leaky gut in chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) is accompanied by a clinical improvement: effects of age, duration of illness and the translocation of LPS from gram-negative bacteria. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. (2008) 29:902–10.

79. Missailidis D, Annesley SJ, Fisher PR. Pathological mechanisms underlying myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Diagnostics. (2019) 9:80. doi: 10.20944/preprints201907.0196.v1

80. Anderson G, Maes M. Mitochondria and immunity in chronic fatigue syndrome. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. (2020) 103:109976. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109976

81. Shukla SK, Cook D, Meyer J, Vernon SD, Le T, Clevidence D, et al. Changes in gut and plasma microbiome following exercise challenge in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0145453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145453

82. Giloteaux L, Goodrich JK, Walters WA, Levine SM, Ley RE, Hanson MR. Reduced diversity and altered composition of the gut microbiome in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome. (2016) 4:30. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0171-4

83. Lakhan SE, Kirchgessner A. Gut inflammation in chronic fatigue syndrome. Nutr Metab. (2010) 7:79. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-7-79

84. Varesi A, Deumer U-S, Ananth S, Ricevuti G. The emerging role of gut microbiota in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): current evidence and potential therapeutic applications. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:5077. doi: 10.3390/jcm10215077

85. König RS, Albrich WC, Kahlert CR, Bahr LS, Löber U, Vernazza P, et al. the gut microbiome in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS). Front Immunol. (2022) 12:628741. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.628741

86. Guo C, Che X, Briese T, Allicock O, Yates RA, Cheng A, et al. Deficient butyrate-producing capacity in the gut microbiome of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome patients is associated with fatigue symptoms. [Preprint] medRxiv. (2021) Available at: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.10.27.21265575v1 (accessed February 21, 2021).

87. Nakatomi Y, Kuratsune H, Watanabe Y. [Neuroinflammation in the brain of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome]. Brain Nerve. (2018) 70:19–25. doi: 10.11477/mf.1416200945

88. Nakatomi Y, Mizuno K, Ishii A, Wada Y, Tanaka M, Tazawa S, et al. Neuroinflammation in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: an (1)(1)C-(R)-PK11195 PET study. J Nucl Med. (2014) 55:945–50. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.131045

89. Mueller C, Lin JC, Sheriff S, Maudsley AA, Younger JW. Evidence of widespread metabolite abnormalities in Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: assessment with whole-brain magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Brain Imaging Behav. (2020) 14:562–72. doi: 10.1007/s11682-018-0029-4

90. Mu Q, Kirby J, Reilly CM, Luo XM. Leaky gut as a danger signal for autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:598. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00598

91. Fasano A. Leaky gut and autoimmune diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. (2012) 42:71–71 doi: 10.1007/s12016-011-8291-x

92. Sotzny F, Blanco J, Capelli E, Castro-Marrero J, Steiner S, Murovska M, et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome – evidence for an autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev. (2018) 17:601–9. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.01.009

93. Morris G, Berk M, Galecki P, Maes M. The emerging role of autoimmunity in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/cfs). Mol Neurobiol. (2014) 49:741–56. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8553-0

94. Blomberg J, Gottfries CG, Elfaitouri A, Rizwan M, Rosén A. Infection elicited autoimmunity and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: an explanatory model. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:229. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00229

95. Boonen E, Bornstein SR, Van den Berghe G. New insights into the controversy of adrenal function during critical illness. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. (2015) 3:805–15. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00224-7

96. Van den Berghe G. On the neuroendocrinopathy of critical illness. Perspectives for feeding and novel treatments. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2016) 194:1337–48. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201607-1516CI

97. Bergquist M, Huss F, Fredén F, Hedenstierna G, Hästbacka J, Rockwood AL, et al. Altered adrenal and gonadal steroids biosynthesis in patients with burn injury. Clin Mass Spectr. (2016) 1:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.clinms.2016.10.002

98. Marik PE. Mechanisms and clinical consequences of critical illness associated adrenal insufficiency. Curr Opin Crit Care. (2007) 13:363–9. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32818a6d74

99. Boelen A, Kwakkel J, Thijssen-Timmer DC, Alkemade A, Fliers E, Wiersinga WM. Simultaneous changes in central and peripheral components of the hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid axis in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute illness in mice. J Endocrinol. (2004) 182:315–23. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1820315

100. Joseph-Bravo P, Jaimes-Hoy L, Charli JL. Regulation of TRH neurons and energy homeostasis-related signals under stress. J Endocrinol. (2015) 224:R139–59. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0593

101. Chatzitomaris A, Hoermann R, Midgley JE, Hering S, Urban A, Dietrich B, et al. Thyroid allostasis–adaptive responses of thyrotropic feedback control to conditions of strain, stress, and developmental programming. Front Endocrinol. (2017) 8:163. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00163

102. Harel G, Shamoun DS, Kane JP, Magner JA, Szabo M. Prolonged effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha on anterior pituitary hormone release. Peptides. (1995) 16:641–5. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(95)00019-G

103. Wassen FW, Moerings EP, Van Toor H, De Vrey EA, Hennemann G, Everts ME. Effects of interleukin-1 beta on thyrotropin secretion and thyroid hormone uptake in cultured rat anterior pituitary cells. Endocrinology. (1996) 137:1591–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.5.8612490

104. Boonen E, Langouche L, Janssens T, Meersseman P, Vervenne H, De Samblanx E, et al. Impact of Duration of Critical Illness on the Adrenal Glands of Human Intensive Care Patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2014) 99:4214–22. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2429

105. Téblick A, Peeters B, Langouche L, Van den Berghe G. Adrenal function and dysfunction in critically ill patients. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2019) 15:417–27. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0185-7

106. Weekers F, Van den Berghe G. Endocrine modifications and interventions during critical illness. Proc Nutr Soc. (2004) 63:443–50. doi: 10.1079/PNS2004373

107. Baxter RC. Changes in the IGF–IGFBP axis in critical illness. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2001) 15:421–34. doi: 10.1053/beem.2001.0161

108. Van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Mohan S, Baxter RC, Veldhuis JD, et al. Reactivation of pituitary hormone release and metabolic improvement by infusion of growth hormone-releasing peptide and thyrotropin-releasing hormone in patients with protracted critical illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1999) 84:1311–23. doi: 10.1210/jc.84.4.1311

109. Litin SC. Mayo Clinic Family Health Book 5th Edition: Completely Revised and Updated. Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic Press (2018).

110. Hertoghe T. Atlas of Endocrinology for Hormone Therapy. Luxembourg: International Medical Books (2010).

111. De Bellis A, Bellastella G, Pernice V, Cirillo P, Longo M, Maio A, et al. Hypothalamic-Pituitary autoimmunity and related impairment of hormone secretions in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2021) 106:e5147–55. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab429

112. Berwaerts J, Moorkens G, Abs R. Secretion of growth hormone in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Growth Horm IGF Res. (1998) 8(Suppl. B):127–9. doi: 10.1016/S1096-6374(98)80036-1

113. Moorkens G, Berwaerts J, Wynants H, Abs R. Characterization of pituitary function with emphasis on GH secretion in the chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. (2000) 53:99–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2000.01049.x

114. Cleare AJ, Sookdeo SS, Jones J, O'Keane V, Miell JP. Integrity of the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor system is maintained in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2000) 85:1433–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.85.4.1433

115. Teitelbaum J, Bird B. Effective Treatment of Severe Chronic Fatigue: A Report of a Series of 64 Patients. J Musculoskelet Pain. (1995) 3:91–110. doi: 10.1300/J094v03n04_11

116. Holtorf K. Diagnosis and treatment of Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction in patients with chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) and Fibromyalgia (FM). J Chronic Fatigue Syndr. (2008) 14:59–88. doi: 10.1300/J092v14n03_06

117. Fuite J, Vernon SD, Broderick G. Neuroendocrine and immune network re-modeling in chronic fatigue syndrome: An exploratory analysis. Genomics. (2008) 92:393–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.08.008

118. Holtorf K. Thyroid hormone transport into cellular tissue. J Restor Med. (2014) 3:53–68. doi: 10.14200/jrm.2014.3.0104

119. Holtorf K. Peripheral thyroid hormone conversion and its impact on TSH and metabolic activity. J Restor Med. (2014) 3:30–52. doi: 10.14200/jrm.2014.3.0103

120. Ruiz-Núñez B, Tarasse R, Vogelaar EF, Janneke Dijck-Brouwer DA, Muskiet FAJ. Higher prevalence of “low T3 syndrome” in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: a case–control study. Front Endocrinol. (2018) 9:97. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00097

121. Poteliakhoff A. Adrenocortical activity and some clinical findings in acute and chronic fatigue. J Psychosom Res. (1981) 25:91–5. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(81)90095-7

122. Demitrack MA, Dale JK, Straus SE, Laue L, Listwak SJ, Kruesi MJ, et al. Evidence for impaired activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1991) 73:1224–34. doi: 10.1210/jcem-73-6-1224

123. Scott LV, Medbak S, Dinan TG. Blunted adrenocorticotropin and cortisol responses to corticotropin-releasing hormone stimulation in chronic fatigue syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand. (1998) 97:450–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10030.x

124. De Becker P, De Meirleir K, Joos E, Campine I, Van Steenberge E, Smitz J, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) response to iv ACTH in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Horm Metab Res. (1999) 31:18–21. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-978690

125. Cleare AJ, Miell J, Heap E, Sookdeo S, Young L, Malhi GS, et al. Hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome, and the effects of low-dose hydrocortisone therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2001) 86:3545–54. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.8.7735

126. Gaab J, Huster D, Peisen R, Engert V, Heitz V, Schad T, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis reactivity in chronic fatigue syndrome and health under psychological, physiological, and pharmacological stimulation. Psychosom Med. (2002) 64:951–62. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200211000-00012

127. Jerjes WK, Cleare AJ, Wessely S, Wood PJ, Taylor NF. Diurnal patterns of salivary cortisol and cortisone output in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Affect Disord. (2005) 87:299–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.03.013

128. Segal TY, Hindmarsh PC, Viner RM. Disturbed adrenal function in adolescents with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. (2005) 18:295–301. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.2005.18.3.295

129. Van Den Eede F, Moorkens G, Hulstijn W, Van Houdenhove B, Cosyns P, Sabbe BG, et al. Combined dexamethasone/corticotropin-releasing factor test in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychol Med. (2008) 38:963–73. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001444

130. Van Den Eede F, Moorkens G, Van Houdenhove B, Cosyns P, Claes SJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in chronic fatigue syndrome. Neuropsychobiology. (2007) 55:112–20. doi: 10.1159/000104468

131. Papadopoulos AS, Cleare AJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2011) 8:22–32. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.153

132. Craddock TJ, Fritsch P, Rice MA Jr, del Rosario RM, Miller DB, et al. A role for homeostatic drive in the perpetuation of complex chronic illness: Gulf War Illness and chronic fatigue syndrome. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e84839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084839

133. Gaab J, Engert V, Heitz V, Schad T, Schurmeyer TH, Ehlert U. Associations between neuroendocrine responses to the Insulin Tolerance Test and patient characteristics in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res. (2004) 56:419–24. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00625-1

134. Tomas C, Newton J, Watson S A. review of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in chronic fatigue syndrome. ISRN Neurosci. (2013) 2013:784520. doi: 10.1155/2013/784520

135. Di Giorgio A, Hudson M, Jerjes W, Cleare AJ. 24-hour pituitary and adrenal hormone profiles in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychosom Med. (2005) 67:433–40. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000161206.55324.8a

136. Pednekar DD, Amin MR, Fekri Azgomi H, Aschbacher K, Crofford LJ, Faghih RT. Characterization of cortisol dysregulation in fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndromes: a state-space approach. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. (2020) 67:3163–72. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2020.2978801

137. Morris G, Anderson G, Maes M. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal hypofunction in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) as a consequence of activated immune-inflammatory and oxidative and nitrosative pathways. Mol Neurobiol. (2017) 54:6806–19. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0170-2

138. Hatziagelaki E, Adamaki M, Tsilioni I, Dimitriadis G, Theoharides TC. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome-metabolic disease or disturbed homeostasis due to focal inflammation in the hypothalamus? J Pharmacol Exp Ther. (2018) 367:155–67. doi: 10.1124/jpet.118.250845

139. Jason LA, Porter N, Herrington J, Sorenson M, Kubow S. Kindling and oxidative stress as contributors to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J Behav Neurosci Res. (2009) 7:1–17.

140. Morris G, Maes M. Oxidative and nitrosative stress and immune-inflammatory pathways in patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS). Curr Neuropharmacol. (2014) 12:168–85. doi: 10.2174/1570159X11666131120224653

141. Gupta S, Aslakson E, Gurbaxani BM, Vernon SD. Inclusion of the glucocorticoid receptor in a hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis model reveals bistability. Theor Biol Med Model. (2007) 4:8. doi: 10.1186/1742-4682-4-8

142. Ben-Zvi A, Vernon SD, Broderick G. Model-based therapeutic correction of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction. PLoS Comput Biol. (2009) 5:e1000273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000273

143. Sedghamiz H, Morris M, Craddock TJA, Whitley D, Broderick G. High-fidelity discrete modeling of the HPA axis: a study of regulatory plasticity in biology. BMC Syst Biol. (2018) 12:76. doi: 10.1186/s12918-018-0599-1

144. Hosseinichimeh N, Rahmandad H, Wittenborn AK. Modeling the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis: A review and extension. Math Biosci. (2015) 268:52–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2015.08.004

145. Craddock TJ, Del Rosario RR, Rice M, Zysman JP, Fletcher MA, Klimas NG, et al. Achieving remission in gulf war illness: a simulation-based approach to treatment design. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0132774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132774

146. Morris MC, Cooney KE, Sedghamiz H, Abreu M, Collado F, Balbin EG, et al. Leveraging prior knowledge of endocrine immune regulation in the therapeutically relevant phenotyping of women with chronic fatigue syndrome. Clin Ther. (2019) 41:656–74 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2019.03.002

147. Scott LV, Teh J, Reznek R, Martin A, Sohaib A, Dinan TG. Small adrenal glands in chronic fatigue syndrome: a preliminary computer tomography study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (1999) 24:759–68. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(99)00028-1

148. Boelen A, Platvoet-Ter Schiphorst MC, Wiersinga WM. Association between serum interleukin-6 and serum 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine in nonthyroidal illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1993) 77:1695–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.6.8263160

149. Davies PH, Black EG, Sheppard MC, Franklyn JA. Relation between serum interleukin-6 and thyroid hormone concentrations in 270 hospital in-patients with non-thyroidal illness. Clin Endocrinol. (1996) 44:199–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1996.668489.x

150. Warner MH, Beckett GJ. Mechanisms behind the non-thyroidal illness syndrome: an update. J Endocrinol. (2010) 205:1–13. doi: 10.1677/JOE-09-0412

151. Wajner SM, Goemann IM, Bueno AL, Larsen PR, Maia AL. IL-6 promotes nonthyroidal illness syndrome by blocking thyroxine activation while promoting thyroid hormone inactivation in human cells. J Clin Invest. (2011) 121:1834–45. doi: 10.1172/JCI44678

152. Wajner SM, Maia AL. New insights toward the acute non-thyroidal illness syndrome. Front Endocrinol. (2012) 3:8. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00008

153. Carter JN, Eastman CJ, Corcoran JM, Lazarus L. Effect of severe, chronic illness on thyroid function. Lancet. (1974) 2:971–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)92070-4

154. Van den Berghe G. Novel insights in the HPA-axis during critical illness. Acta Clin Belg. (2014) 69:397–406. doi: 10.1179/2295333714Y.0000000093

155. Bartalena L, Farsetti A, Flink IL, Robbins J. Effects of interleukin-6 on the expression of thyroid hormone-binding protein genes in cultured human hepatoblastoma-derived (Hep G2) cells. Mol Endocrinol. (1992) 6:935–42. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.6.1323058

156. Bartalena L, Bogazzi F, Brogioni S, Grasso L, Martino E. Role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of the euthyroid sick syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. (1998) 138 6:603–14. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1380603

157. Afandi B, Vera R, Schussler GC, Yap MG. Concordant decreases of thyroxine and thyroxine binding protein concentrations during sepsis. Metabolism. (2000) 49:753–4. doi: 10.1053/meta.2000.6239

158. Bartalena L, Robbins J. Variations in thyroid hormone transport proteins and their clinical implications. Thyroid. (1992) 2:237–45. doi: 10.1089/thy.1992.2.237

159. Mebis L, Paletta D, Debaveye Y, Ellger B, Langouche L, D'Hoore A, et al. Expression of thyroid hormone transporters during critical illness. Eur J Endocrinol. (2009) 161:243. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0290

160. Huang SA, Mulcahey MA, Crescenzi A, Chung M, Kim BW, Barnes C, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta promotes inactivation of extracellular thyroid hormones via transcriptional stimulation of type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase. Mol Endocrinol. (2005) 19:3126–36. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0173

161. Kwakkel J, Wiersinga WM, Boelen A. Interleukin-1beta modulates endogenous thyroid hormone receptor alpha gene transcription in liver cells. J Endocrinol. (2007) 194:257–65. doi: 10.1677/JOE-06-0177

162. Rodriguez-Perez A, Palos-Paz F, Kaptein E, Visser TJ, Dominguez-Gerpe L, Alvarez-Escudero J, et al. Identification of molecular mechanisms related to nonthyroidal illness syndrome in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue from patients with septic shock. Clin Endocrinol. (2008) 68:821–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03102.x

163. Lado-Abeal J, Romero A, Castro-Piedras I, Rodriguez-Perez A, Alvarez-Escudero J. Thyroid hormone receptors are down-regulated in skeletal muscle of patients with non-thyroidal illness syndrome secondary to non-septic shock. Eur J Endocrinol. (2010) 163:765–73. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0376

164. Gereben B, Zavacki AM, Ribich S, Kim BW, Huang SA, Simonides WS, et al. Cellular and molecular basis of deiodinase-regulated thyroid hormone signaling. Endocr Rev. (2008) 29:898–938. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0019

165. De Groot LJ. The non-thyroidal illness syndrome. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G, de Herder WW, Dungan K, et al. editors. Endotext. South Dartmouth, MA: MDText.com, Inc. (2000).

166. Dietrich JW, Landgrafe-Mende G, Wiora E, Chatzitomaris A, Klein HH, Midgley JE, et al. Calculated parameters of thyroid homeostasis: emerging tools for differential diagnosis and clinical research. Front Endocrinol. (2016) 7:57. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2016.00057

167. Mendoza A, Hollenberg AN. New insights into thyroid hormone action. Pharmacol Ther. (2017) 173:135–45. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.02.012

168. Cicatiello AG, Di Girolamo D, Dentice M. Metabolic effects of the intracellular regulation of thyroid hormone: old players, new concepts. Front Endocrinol. (2018) 9:474. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00474

169. De Groot LJ. Dangerous dogmas in medicine: the nonthyroidal illness syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1999) 84:151–64. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.1.5364

170. Donzelli R, Colligiani D, Kusmic C, Sabatini M, Lorenzini L, Accorroni A, et al. Effect of hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism on tissue thyroid hormone concentrations in rat. Eur Thyroid J. (2016) 5:27–34. doi: 10.1159/000443523

171. Plikat K, Langgartner J, Buettner R, Bollheimer LC, Woenckhaus U, Scholmerich J, et al. Frequency and outcome of patients with nonthyroidal illness syndrome in a medical intensive care unit. Metabolism. (2007) 56:239–44. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.09.020

172. Boelen A, Kwakkel J, Fliers E. Beyond low plasma T3: local thyroid hormone metabolism during inflammation and infection. Endocr Rev. (2011) 32:670–93. doi: 10.1210/er.2011-0007

173. Mancini A, Di Segni C, Raimondo S, Olivieri G, Silvestrini A, Meucci E, et al. Thyroid hormones, oxidative stress, and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. (2016) 2016:6757154. doi: 10.1155/2016/6757154

174. Balazs C, Leovey A, Szabo M, Bako G. Stimulating effect of triiodothyronine on cell-mediated immunity. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. (1980) 17:19–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00561672

175. Pillay K. Congenital hypothyroidism and immunodeficiency: evidence for an endocrine-immune interaction. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. (1998) 11:757–61. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.1998.11.6.757

176. Klecha AJ, Genaro AM, Gorelik G, Barreiro Arcos ML, Silberman DM, Schuman M, et al. Integrative study of hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid-immune system interaction: thyroid hormone-mediated modulation of lymphocyte activity through the protein kinase C signaling pathway. J Endocrinol. (2006) 189:45–55. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06137

177. Klein JR. The immune system as a regulator of thyroid hormone activity. Exp Biol Med. (2006) 231:229–36. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100301

178. Hans VH, Lenzlinger PM, Joller-Jemelka HI, Morganti-Kossmann MC, Kossmann T. Low T3 syndrome in head-injured patients is associated with prolonged suppression of markers of cell-mediated immune response. Eur J Trauma. (2005) 31:359–68. doi: 10.1007/s00068-005-2068-y

179. Hodkinson CF, Simpson EE, Beattie JH, O'Connor JM, Campbell DJ, Strain JJ, et al. Preliminary evidence of immune function modulation by thyroid hormones in healthy men and women aged 55-70 years. J Endocrinol. (2009) 202:55–63. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0488

180. Straub RH, Cutolo M, Buttgereit F, Pongratz G. Energy regulation and neuroendocrine-immune control in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Intern Med. (2010) 267:543–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02218.x

181. Jara EL, Munoz-Durango N, Llanos C, Fardella C, Gonzalez PA, Bueno SM, et al. Modulating the function of the immune system by thyroid hormones and thyrotropin. Immunol Lett. (2017) 184:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2017.02.010

182. Bilal MY, Dambaeva S, Kwak-Kim J, Gilman-Sachs A, Beaman KD. A role for iodide and thyroglobulin in modulating the function of human immune cells. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:1573. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01573

183. van der Spek AH, Surovtseva OV, Jim KK, van Oudenaren A, Brouwer MC, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C, et al. Regulation of intracellular triiodothyronine is essential for optimal macrophage function. Endocrinology. (2018) 159:2241–52. doi: 10.1210/en.2018-00053

184. De Vito P, Incerpi S, Pedersen JZ, Luly P, Davis FB, Davis PJ. Thyroid hormones as modulators of immune activities at the cellular level. Thyroid. (2011) 21:879–90. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0429

185. De Luca R, Davis PJ, Lin HY, Gionfra F, Percario ZA, Affabris E, et al. Thyroid hormones interaction with immune response, inflammation and non-thyroidal illness syndrome. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2020) 8:614030. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.614030

186. Textoris J, Mallet F. Immunosuppression and herpes viral reactivation in intensive care unit patients: one size does not fit all. Crit Care. (2017) 21:230. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1803-1

187. Coşkun O, Yazici E, Sahiner F, Karakaş A, Kiliç S, Tekin M, et al. Cytomegalovirus and Epstein–Barr virus reactivation in the intensive care unit. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfallmed. (2017) 112:239–45. doi: 10.1007/s00063-016-0198-0

188. Walton AH, Muenzer JT, Rasche D, Boomer JS, Sato B, Brownstein BH, et al. Reactivation of multiple viruses in patients with sepsis. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e98819. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098819

189. Pall M. The NO/ONOO-cycle mechanism as the cause of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgia encephalomyelitis. In: Svoboda E, Zelenjcik K, editors. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Symptoms, Causes and Prevention. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Publishers (2009). p. 27–56

190. Morris G, Maes M. Mitochondrial dysfunctions in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome explained by activated immuno-inflammatory, oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways. Metab Brain Dis. (2014) 29:19–36. doi: 10.1007/s11011-013-9435-x

191. Armstrong CW, McGregor NR, Lewis DP, Butt HL, Gooley PR. Metabolic profiling reveals anomalous energy metabolism and oxidative stress pathways in chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Metabolomics. (2015) 11:1626–39. doi: 10.1007/s11306-015-0816-5

192. Shungu DC, Weiduschat N, Murrough JW, Mao X, Pillemer S, Dyke JP, et al. Increased ventricular lactate in chronic fatigue syndrome. III Relationships to cortical glutathione and clinical symptoms implicate oxidative stress in disorder pathophysiology. NMR Biomed. (2012) 25:1073–87. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2772

193. Montoya JG, Holmes TH, Anderson JN, Maecker HT, Rosenberg-Hasson Y, Valencia IJ, et al. Cytokine signature associated with disease severity in chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2017) 114:E7150–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1710519114

194. Hornig M, Montoya JG, Klimas NG, Levine S, Felsenstein D, Bateman L, et al. Distinct plasma immune signatures in ME/CFS are present early in the course of illness. Sci Adv. (2015) 1:e1400121. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1400121

195. Langouche L, Van den Berghe G. Hypothalamic-pituitary hormones during critical illness: a dynamic neuroendocrine response. Handb Clin Neurol. (2014) 124:115–26. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-59602-4.00008-3

196. Boonen E, Van den Berghe G. Endocrine responses to critical illness: novel insights and therapeutic implications. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2014) 99:1569–82. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4115

197. Deane A, Chapman MJ, Fraser RJ, Horowitz M. Bench-to-bedside review: the gut as an endocrine organ in the critically ill. Crit Care. (2010) 14:228. doi: 10.1186/cc9039

198. Van den Berghe G, de Zegher F, Baxter RC, Veldhuis JD, Wouters P, Schetz M, et al. Neuroendocrinology of prolonged critical illness: effects of exogenous thyrotropin-releasing hormone and its combination with growth hormone secretagogues. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1998) 83:309–19. doi: 10.1210/jc.83.2.309

199. Mesotten D, Van den Berghe G. Changes within the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor I/IGF binding protein axis during critical illness. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. (2006) 35:793–805, ix–x. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2006.09.010

200. Wu R, Dong W, Ji Y, Zhou M, Marini CP, Ravikumar TS, et al. Orexigenic hormone ghrelin attenuates local and remote organ injury after intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. PLoS ONE. (2008) 3:e2026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002026

201. Debaveye Y, Ellger B, Mebis L, Darras VM, Van den Berghe G. Regulation of tissue iodothyronine deiodinase activity in a model of prolonged critical illness. Thyroid. (2008) 18:551–60. doi: 10.1089/thy.2007.0287

202. Lizcano F, Rodríguez JS. Thyroid hormone therapy modulates hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Endocr J. (2011) 58:137–42. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.K10E-369

203. Sánchez-Franco F, Fernández L, Fernández G, Cacicedo L. Thyroid hormone action on ACTH secretion. Horm Metab Res. (1989) 21:550–2. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1009285

204. Hiroi Y, Kim HH, Ying H, Furuya F, Huang Z, Simoncini T, et al. Rapid nongenomic actions of thyroid hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2006) 103:14104–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601600103

205. Sharma JN, Al-Omran A, Parvathy SS. Role of nitric oxide in inflammatory diseases. Inflammopharmacology. (2007) 15:252–9. doi: 10.1007/s10787-007-0013-x

206. Handa O, Stephen J, Cepinskas G. Role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase-derived nitric oxide in activation and dysfunction of cerebrovascular endothelial cells during early onsets of sepsis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. (2008) 295:H1712–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00476.2008

207. Gluvic ZM, Obradovic MM, Sudar-Milovanovic EM, Zafirovic SS, Radak DJ, Essack MM, et al. Regulation of nitric oxide production in hypothyroidism. Biomed Pharmacother. (2020) 124:109881. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.109881

208. Bertinat R, Villalobos-Labra R, Hofmann L, Blauensteiner J, Sepúlveda N, Westermeier F. Decreased NO production in endothelial cells exposed to plasma from ME/CFS patients. Vascul Pharmacol. (2022) 148:106953. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2022.106953

209. Lim CF, Docter R, Visser TJ, Krenning EP, Bernard B, van Toor H, et al. Inhibition of thyroxine transport into cultured rat hepatocytes by serum of nonuremic critically ill patients: effects of bilirubin and nonesterified fatty acids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1993) 76:1165–72. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.5.8496307

210. Vos RA, De Jong M, Bernard BF, Docter R, Krenning EP, Hennemann G. Impaired thyroxine and 3,5,3'-triiodothyronine handling by rat hepatocytes in the presence of serum of patients with nonthyroidal illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (1995) 80:2364–70. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.8.7629231

211. Preiser JC, Ichai C, Orban JC, Groeneveld AB. Metabolic response to the stress of critical illness. Br J Anaesth. (2014) 113:945–54. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu187

212. McBride MA, Owen AM, Stothers CL, Hernandez A, Luan L, Burelbach KR, et al. The metabolic basis of immune dysfunction following sepsis and trauma. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:1043. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01043

213. Singer M. Critical illness and flat batteries. Crit Care. (2017) 21:309. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1913-9

214. Naviaux RK, Naviaux JC Li K, Bright AT, Alaynick WA, Wang L, et al. Metabolic features of chronic fatigue syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2016) 113:E5472–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607571113

215. Naviaux RK. Perspective: Cell danger response Biology—The new science that connects environmental health with mitochondria and the rising tide of chronic illness. Mitochondrion. (2020) 51:40–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2019.12.005

216. Naviaux RK. Metabolic features and regulation of the healing cycle-a new model for chronic disease pathogenesis and treatment. Mitochondrion. (2019) 46:278–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2018.08.001

217. Arnett SV, Clark IA. Inflammatory fatigue and sickness behaviour - lessons for the diagnosis and management of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Affect Disord. (2012) 141:130–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.04.004

218. Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A'Court C, Buxton M, Husain L. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. (2020) 370:m3026. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3026

219. Dani M, Dirksen A, Taraborrelli P, Torocastro M, Panagopoulos D, Sutton R, et al. Autonomic dysfunction in 'long COVID': rationale, physiology and management strategies. Clin Med. (2020) 21:e63–7. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0896

220. Huang C, Huang L, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Gu X, et al. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study. Lancet. (2021) 397:220–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8

221. Townsend L, Dyer AH, Jones K, Dunne J, Mooney A, Gaffney F, et al. Persistent fatigue following SARS-CoV-2 infection is common and independent of severity of initial infection. PLoS ONE. (2020) 15:e0240784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240784

222. Komaroff AL, Bateman L. Will COVID-19 lead to myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome? Front Med. (2021) 7:606824. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.606824

223. Wildwing T, Holt N. The neurological symptoms of COVID-19: a systematic overview of systematic reviews, comparison with other neurological conditions and implications for healthcare services. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. (2021) 12. doi: 10.1177/2040622320976979

224. Proal AD, VanElzakker MB. Long COVID or post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC): an overview of biological factors that may contribute to persistent symptoms. Front Microbiol. (2021) 12:698169. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.698169

225. Mackay A A. Paradigm for post-Covid-19 fatigue syndrome analogous to ME/CFS. Front Neurol. (2021) 12:701419. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.701419

226. Komaroff AL, Lipkin WI. Insights from myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome may help unravel the pathogenesis of postacute COVID-19 syndrome. Trends Mol Med. (2021) 27:895–906. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2021.06.002

227. Comella PH, Gonzalez-Kozlova E, Kosoy R, Charney AW, Peradejordi IF, Chandrasekar S, et al. A Molecular network approach reveals shared cellular and molecular signatures between chronic fatigue syndrome and other fatiguing illnesses. [Preprint] medRxiv. (2021). Available at: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.29.21250755v1 (accessed February 21, 2021).

Keywords: post-viral fatigue, hypoperfusion, endotheliopathy, gut permeability, endotoxemia, pituitary, non-thyroidal illness syndrome, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)

Citation: Stanculescu D and Bergquist J (2022) Perspective: Drawing on Findings From Critical Illness to Explain Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Front. Med. 9:818728. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.818728

Received: 25 November 2021; Accepted: 11 February 2022;

Published: 08 March 2022.

Edited by:

Juarez Antonio Simões Quaresma, Universidade do Estado do Pará, BrazilReviewed by:

Anthony L. Komaroff, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, United StatesCopyright © 2022 Stanculescu and Bergquist. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jonas Bergquist, am9uYXMuYmVyZ3F1aXN0QGtlbWkudXUuc2U=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.