- 1School of Information Science and Technology, ShanghaiTech University, Shanghai, China

- 2Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Energy Efficient and Custom AI IC, Shanghai, China

- 3Department of Radiopharmacy and Molecular Imaging, School of Pharmacy, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

- 4PET Center, Huashan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

- 5Shanghai Changes Tech, Ltd., Shanghai, China

- 6Institute for Regenerative Medicine, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

- 7Institute for Biomedical Engineering, ETH Zürich and University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Small animal models play a fundamental role in brain research by deepening the understanding of the physiological functions and mechanisms underlying brain disorders and are thus essential in the development of therapeutic and diagnostic imaging tracers targeting the central nervous system. Advances in structural, functional, and molecular imaging using MRI, PET, fluorescence imaging, and optoacoustic imaging have enabled the interrogation of the rodent brain across a large temporal and spatial resolution scale in a non-invasively manner. However, there are still several major gaps in translating from preclinical brain imaging to the clinical setting. The hindering factors include the following: (1) intrinsic differences between biological species regarding brain size, cell type, protein expression level, and metabolism level and (2) imaging technical barriers regarding the interpretation of image contrast and limited spatiotemporal resolution. To mitigate these factors, single-cell transcriptomics and measures to identify the cellular source of PET tracers have been developed. Meanwhile, hybrid imaging techniques that provide highly complementary anatomical and molecular information are emerging. Furthermore, deep learning-based image analysis has been developed to enhance the quantification and optimization of the imaging protocol. In this mini-review, we summarize the recent developments in small animal neuroimaging toward improved translational power, with a focus on technical improvement including hybrid imaging, data processing, transcriptomics, awake animal imaging, and on-chip pharmacokinetics. We also discuss outstanding challenges in standardization and considerations toward increasing translational power and propose future outlooks.

Introduction

Clinically deployed imaging modalities, including MRI, PET, and single-photon emission CT (SPECT), have vastly facilitated the understanding of human brain function (1–3) and the development of disease biomarkers for brain disorders such as brain tumors, Alzheimer’s disease, ischemic stroke, and multiple sclerosis toward personalized medicine (4). MRI sequences for brain imaging, such as diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) for white matter integrity (5), structural T1 and T2 for regional brain atrophy, arterial spin labeling (ASL) for cerebral perfusion, and susceptibility-weighted imaging for microbleed assessment, are routinely performed both in animal models in the laboratory and in human patients in the clinical setting (6). The development of 7 T human MRI allows imaging of the living human brain at the mesoscopic level with a high spatial and temporal signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) (7, 8). There are currently seven Food and Drug Administration approved commercially available MR contrast agents with indications for central nervous system lesions (9). This gadolinium (III)-based contrast agents are widely used in the clinical setting. In addition, targeted agents, activatable agents, high-relaxivity agents, and gadolinium-free MR contrast agents are being developed (9). Gadolinium(III)-based contrast agents have been successful as they provide essential diagnostic information that often cannot be obtained with other non-invasive techniques. PET has been widely used as a highly quantitative non-invasive tool to detect neurotransmitter receptors and protein/enzyme levels, e.g., cerebral glucose metabolism ([18F]fluorodeoxyglucose, FDG), dopamine receptor ([11C]raclopride), glial activation, and amyloid-β plaques, in the living human brain (10). It is also noted that optical imaging accounts for a large segment of clinical imaging and has been used in image-guided surgery, although far fewer contrast agents have been approved for optical imaging than PET (11, 12). Emerging optical imaging methods, including fluorescence and optoacoustic imaging (OAT) (13, 14), have shown increasing value for assisting diagnosis and surgical navigation. Observation of molecular, structural, and functional changes in the brains of small animal models that recapitulate human diseases is highly valuable for understanding physiological function (15) and the mechanisms underlying brain disorders (16). Small animal brain imaging has been indispensable for the development of novel therapeutic drugs and diagnostic imaging probes. A previous study showed that preclinical dosimetry studies and models facilitate the prediction of clinical doses of new PET tracers (17). Here, we summarize the gaps in the translation of preclinical neuroimaging and focus on the recent technical developments in improving its clinical relevance, especially regarding data acquisition (hybrid imaging and awake animal imaging), data analysis using deep learning (DL), and transcriptomics. We also outline the current outstanding challenges in closing the translational gap and propose outlooks for the future.

Hybrid Imaging

The most commonly used hybrid systems in small animal imaging are the integration of molecular imaging using PET, SPECT, fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT), and OAT with structural imaging using MRI and CT. Both PET/SPECT-CT and PET/SPECT-MRI provide research tools for probing molecular and structural information and have demonstrated significant value in brain research (18, 19). Molecular imaging modalities generally lack high-spatial resolution and soft tissue contrast to accurately allocate the distribution of specified molecular signals. Thus, it is essential to provide accurate anatomical information along with the molecular imaging modalities to better interpret the acquired molecular signals (20–22). There are two approaches to address this: sequential-mode using different standalone modalities and follow-up image processing/image registration (23) or hybridized multimodal imaging (24). Sequential-mode multimodal imaging allows convenient data acquisition and minimal interference from each modality, while hybridization of the multimodal method enables dynamic imaging data from multiple channel signal sources, enhanced image reconstruction with prior structural information, and improved quantitative information (25).

Positron Emission Tomography/SPECT-CT and PET/SPECT-MRI

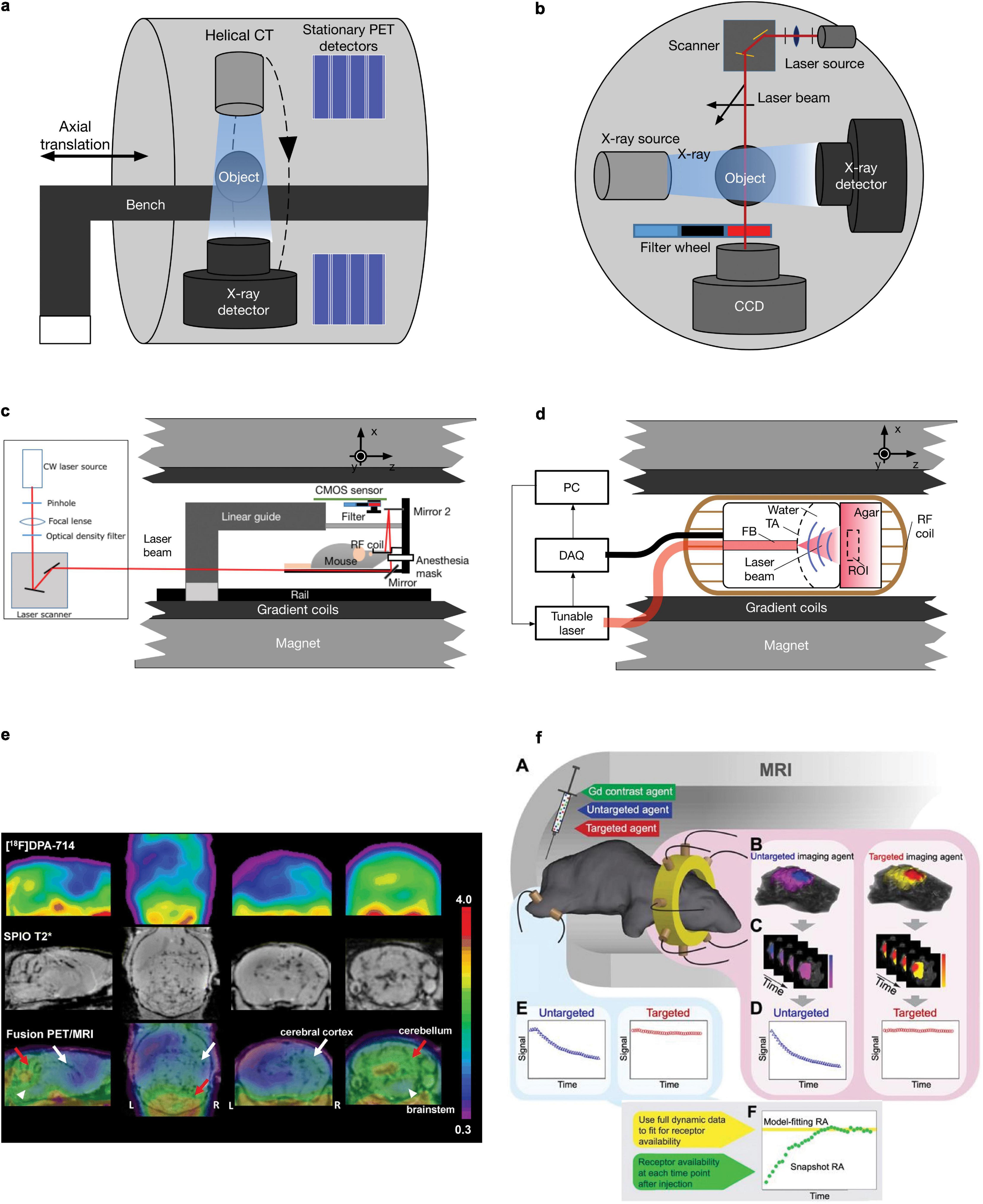

Positron emission tomography/SPECT provides quantitative in vivo detection of picomolar concentrations of the target within a large field-of-view (26–28). The resolution of commercially available microPET is approximately 0.5–2 mm (29–32), which is sufficient for rat brain imaging but suboptimal for mouse brain imaging considering the spillover and size of the mouse brain (10 mm × 10 mm × 15 mm) (33). The concept of combining PET/SPECT with CT was first introduced to clinical trials in the early 2000s (34). An early prototype PET/SPECT-CT scanner used a coaxial configuration and minimal axial translation of a movable couch to facilitate the sequential acquisition of PET/SPECT and CT during a single imaging session (35). The CT image serves as (1) an anatomical reference to map the molecular information given by PET and (2) an attenuation map for PET reconstruction to achieve more quantitative data (36). For hybridization of PET/SPECT and MRI, MRI provides better soft-tissue contrast without radiation and contains multiparametric (structural, molecular, and functional) readouts (25, 27, 37–39). Various MRI contrast agents, such as superparamagnetic iron oxide, can be applied to identify microglial activation/macrophage infiltration along with simultaneous PET using [18F]DPA-714 for glial activation in mouse models of relapsing-remitting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (40) (Figures 1a,e). As a high magnetic field exists in preclinical MRI scanners, the space inside the scanner bore is significantly limited. Several PET inserts in 7T or 9.4T MRI have been reported, such as Hyperion II and MADPET4 with digital silicon photomultiplier technology (41–47). Recently, Liu et al. reported a multimodal intravital imaging system that provided a coregistered in vivo trans-scale and transparent platform (PET, MRI, microscopy) and quantitative evaluation of tumor anatomy, vasculature, and the microenvironment, including glucose, oxygen, and acidity metabolism (48).

Figure 1. Schematics and example of different small animal hybrid imaging systems. (a) PET-CT uses a coaxial configuration with a helical CT scanner and stationary PET detectors aligned in parallel in one imaging chamber. A movable bench carrying the measured object allows minimal axial translation, facilitating dual-modal imaging. (b) A cross-sectional view of the FMT-CT configuration. In a transmission-mode FMT, the charge-coupled device detector and the illumination module, including a laser source and a scanning device, are placed on the opposite sides of the imaging object. Perpendicular to the optical path of FMT measurement, an X-ray source/detector pair is aligned in the same CT gantry. (c) FMT-MRI can be implemented by using an MR-compatible optical imager inserted into a preclinical MRI scanner. The major component of the insert includes a CMOS array and a customized RF coil [adapted from Ren et al. (63) with permission from Springer Nature]. (d) Similar to FMT-MRI, in OAT-MRI, an MR-compatible ultrasound transducer array together with the coupling medium was used as an OAT insert inside an MRI scanner. A pulsed light source and a data acquisition module (DAQ) are placed outside the MRI bore (adapted from Ren et al. (87) with permission from John Wiley & Sons, Inc. (e) Sagittal, coronal, and transaxial [18F]DPA-714 PET, SPIO T2*MRI, and PET/MRI fusion images of a representative experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mouse. PET images represent summed scans (20–50 min postinjection) normalized to the left cerebral neocortex SUV values. Increased radiotracer uptake and loss of T2* signal can be observed in the cerebellum (red arrow), brainstem (white arrowheads), and, to a lesser extent, right cerebral cortex (white arrow) in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mouse but not in the control. R, right; L, left. Reproduced from Coda et al. (40) with permission from Springer Nature. (f) MRI-FMT animal interface. (A) Illustration inside the magnet bore showing the tomographic fiber array encircling the head and a pair of optical fibers on the leg to acquire normal tissue kinetics. (B) Representative volumetric images of fluorescence activity (one frame) in the brain and tumor for both targeted and untargeted agents. Volumes such as these were acquired at approximately 0.5 Hz over the course of over 60 min, resulting in dynamic image stacks of each agent (C). Fluorescence activity was then extracted from the tumor and normal tissue to produce dynamic uptake curves, as shown in (D) and (E), respectively. Data from these curves were then used to determine RA using the model-fitting and snapshot approaches, as illustrated in (F). Reproduced from (64) with permission from Ivyspring International Publisher.

Fluorescence Molecular Tomography-CT and FMT-MRI

In addition to PET/SPECT, fluorescence imaging provides an alternative molecular imaging method with the features of high sensitivity, low cost, and non-ironizing radiation. FMT utilizes near-infrared light to penetrate living tissue up to several centimeters deep and applies a model-based reconstruction algorithm to recover the three-dimensional distribution of fluorescence probes (49). FMT-CT was first introduced by combining FMT in transmission mode with a commercial CT scanner (50) (Figure 1b); a point-shaped collimated laser source and a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera were placed on the opposite sides of the imaging object and mounted onto the CT gantry perpendicular to the X-ray instrumentation axis (51). The irregularly shaped boundary and heterogeneous inner structure can be rendered by CT and used for more accurate FMT image reconstruction (52). The FMT image quality is significantly improved with prior information from CT (53, 54). The FMT-CT hybrid system has been used for the detection of amyloid-β deposition in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and lung cancer (50, 55–59). FMT has been combined with MRI, such as detecting overexpressed epidermal growth factor receptors in a mouse model with gliomas (60) (Figure 1c). Similarly, an MR-compatible optical imager was inserted into a preclinical MRI scanner (61) using optical fibers or a silicon-based single-photon avalanche diode array to collect the emitted photons (61, 62). The anatomical reference obtained by MRI can be used as a prior information in a finite-element-method-based reconstruction algorithm to achieve a more accurate allocation of any fluorescent probe. In addition, dynamic image acquisition using FMT-MRI was performed to evaluate vascular perfusion and permeability in a breast tumor mouse model (63) and to quantify the target availability during therapy (64) (Figure 1f).

Optoacoustic Tomography-CT and OAT-MRI

Optoacoustic imaging combines the rich optical image contrast and exquisite spatiotemporal resolution given by ultrasound; consequently, it has developed rapidly into a common research tool for the preclinical studies (65, 66). OAT imaging has been applied to detect molecular and functional alterations in ischemic stroke, brain tumors, and Alzheimer’s disease rodent models (22, 67–70). However, the identification of different tissues or organs is difficult due to the limited soft-tissue contrast given in OAT. Several studies have utilized hybrid imaging systems combining OAT and ultrasound that offer moderate anatomical information in small animal imaging (71–73). Although the image formation mechanisms are different in these two modalities, it is relatively straightforward to combine OAT and ultrasound, as they utilize the same transducer array and coupling medium during measurement. The development of OAT-CT and OAT-MRI is still at an early stage. Sequential-mode multimodal imaging with OAT-CT and OAT-MRI has also been reported (74–79). Coregistration of images sequentially acquired with OA and other methods is performed for volume-of-interest analysis using dedicated algorithms (80, 81), either software-based (82–85) or a hardware-assisted protocol based on stable bimodal imaging support and a rigorous data acquisition procedure (81, 86). Similar to FMT-MRI and PET-MRI hybrid systems, the combination of OAT and MRI is highly restricted by the limited space inside the MRI bore and electromagnetic interference mainly caused by radiofrequency (RF) coils. To address these challenges, the optoacoustic signal readout can be properly shielded by copper and synchronized according to different MRI sequences. More recently, a proof-of-concept hybrid OAT-MRI system that allows simultaneous recording kinetics of two contrast agents in a phantom was reported (87), for which an MR-compatible OAT insert was developed with a specifically distributed transducer array and copper-made shielding (Figure 1d). For data acquisition, the excitation laser pulse signal and MRI pulse sequence were synchronized to avoid interference between the two modalities. Hybridization with MRI greatly enhances the performance of OAT by enabling the simultaneous readings of multichannel dynamic information, including resting-state functional MRI (rs-fMRI) for blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signals, oxygen saturation, or contrast agent biodistribution (88). Applications of OA imaging in clinical research have shown promising results and are still limited to the peripheral system (89–91). In vivo OA imaging in non-human primates has been demonstrated (92) and in the neonatal brain (93). A recent OA/functional MRI study of the living adult human brain demonstrated the potential of its application in the clinical neuroimaging (94, 95). However, significant challenges in skull aberrations and acoustic distortions still need to be addressed for potential clinical application and to further close the translational gap. Excitation lasers with longer wavelengths, such as in the near-infrared II window, and ultrasound transducers with lower central frequencies reduce both optical attenuation and acoustic aberration (96). The anatomical information containing both the skull and brain obtained by CT or MRI in those hybrid systems can be used for accurate modeling for light and ultrasound propagation, which can potentially improve OAT reconstruction (87).

Translational Gaps

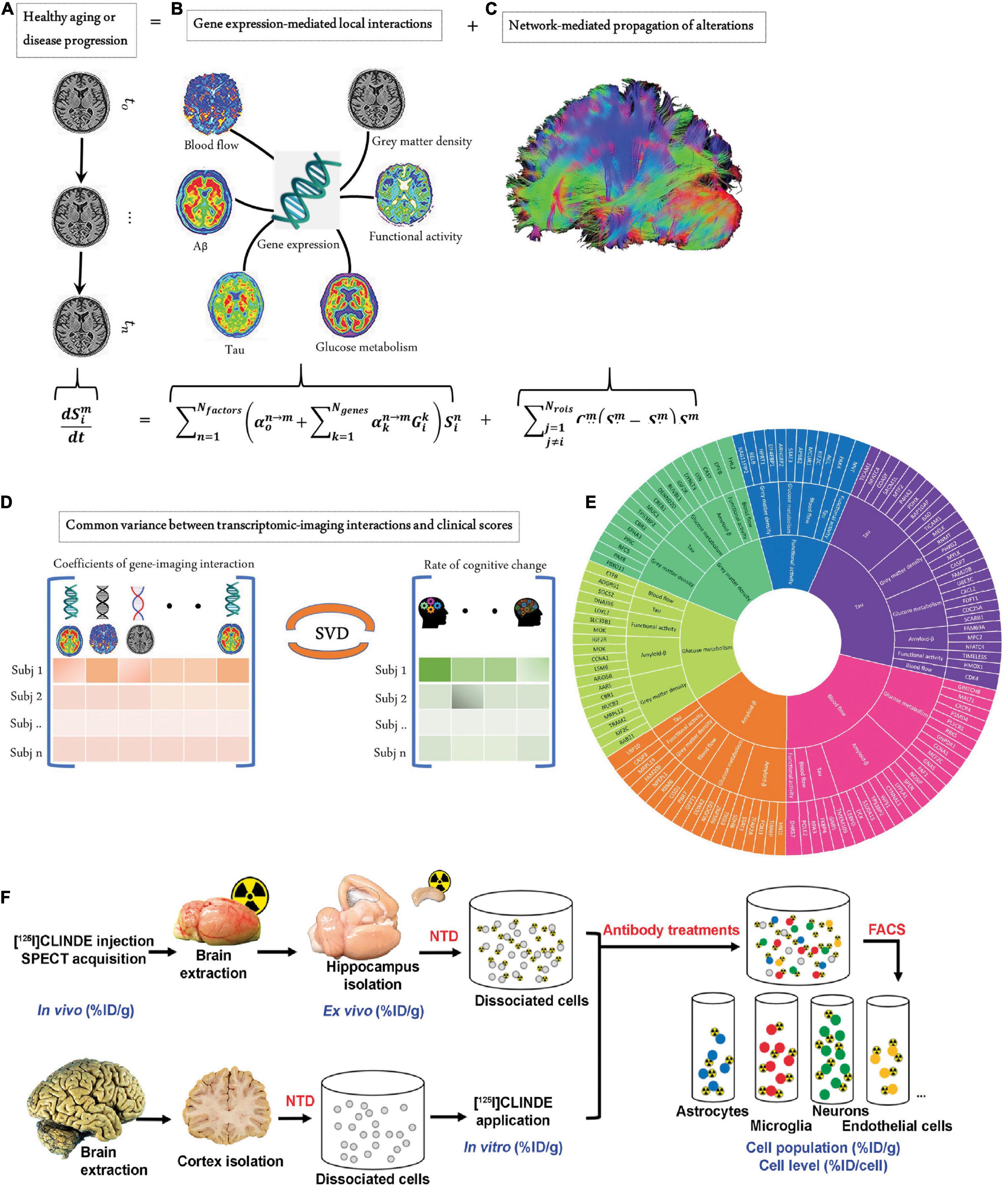

Translational gaps exist in developing imaging biomarkers, including those (1) between in vitro and in vivo animal studies, (2) between animal and patient translation as a robust medical research tool, and (3) between research tools and integrated clinical applications (97, 98). For clinical imaging, rapid and safe processes, reliable readouts and the added value to patients (in comparison to the existing option) are important. Imaging biomarker generates added value by facilitating drug development, monitoring of treatment response (99), and reducing cost per quality-adjusted life year gained by enabling early diagnosis (100). Closing the translational gaps requires enormous technical, biological, and clinical validation and also cost effectiveness assessment (101). The lack of a satisfactory animal model is a shared problem for research on brain diseases, including stroke, neurodegenerative diseases, psychiatric diseases, and multiple sclerosis (102). Many reviews have outlined the challenges in animal models and the need for models better mimicking human diseases to improve translational power (103, 104). Using the genome engineering technology CRISPR/Cas9, humanized knock-in animal models are under rapid development. However, species differences exist in the size of the brain, anatomical structure, cerebral cortical folding, parcelation, and connectivity neuron size in humans, non-human primates, and mice (105, 106). Microglia and astrocyte in humans and mice exhibit different vulnerabilities and responses to external stressors (107, 108). The differences in gene expression and protein level between small animals and humans increase the difficulty of translation of targeting ligands (109). Moreover, there are pharmacological and behavioral differences between mice and rats, which need to be considered when interpreting the results. In addition, strain- and substrain-dependent vulnerability to pathological interventions such as permanent focal cerebral ischemia in a mouse model has been documented (110, 111). Bailey et al. showed that the C57BL/6 strain background has an influence on tauopathy progression in the rTg4510 transgenic mouse model originally of the FVB/129 background (112). Moreover, the recent findings highlighted the unique vulnerability of humans to Alzheimer’s disease or primary tauopathy, and the amyloid-β and tau deposits formed in the brains from transgenic mouse models over 1–2 years are structurally different compared with those found in aged patients (113). A similar difference has been reported for α-synuclein aggregates in patients with Parkinson’s disease (114). These differences are reflected in the divergent binding properties observed in tau/amyloid-β/α-synuclein imaging probes binding to the brains of rodent models, non-human primates, and patients (115–117). In addition to the aforementioned developments, recent single-cell tracking PET, a cellular global positioning system, was able to detect a single cell over time in a living mouse and directly related the in vivo imaging pattern to a single cell with its molecular profiles (118). Moreover, Tournier et al. and Nutma et al. developed fluorescence-activated cell sorting to radioligand-treated tissues (FACS-RTT) to reveal the cell origin of the radioligand translocator protein binding (119, 120) (Figure 2F).

Figure 2. Measures to close biological gaps. (A–E) Integrated transcriptomic and neuroimaging data to understand biological mechanisms in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. (A) The longitudinal alteration of macroscopic biological factors in healthy and diseased brains due to gene-imaging interactions and the propagation of the ensuing alterations across brain networks. (B) Regional multifactorial interactions between six macroscopic biological factors/imaging modalities are modulated by local gene expression. (C) Causal multifactorial propagation network capturing the interregional spread of biological factor alterations through physical connections. (D) By applying a multivariate analysis through singular value decomposition (SVD), the maximum cross-correlation between age-related changes in cognitive/clinical evaluation and the magnitude of genetic modulation of imaging modalities was determined in a cohort of stable healthy subjects (for healthy aging), mild cognitive impairment (MCI) converters, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) subjects (for AD progression). (E) The key causal genes driving healthy aging and AD progression are identified through their absolute contributions to the explained common variance between the gene-imaging interactions and cognitive scores. Reproduced from (148) with permission from eLife Sciences Publications, Ltd. (F) Overview of the fluorescence-activated cell sorting to radioligand-treated tissues (FACS–RTT) protocol. Schematic overview of the methodology used for the in vivo, ex vivo, in vitro and cellular measurement of the radioligand. % ID/cell: percentage of the injected dose/cell; % ID/g: percentage of the injected dose/g tissue weight; NTD: neural tissue dissociation. Reproduced from (120) with permission from Sage Publication.

Awake Animal Imaging

Anesthesia leads to alterations in the brain state, cardiovascular physiology, and hemodynamic properties. Functional readouts derived from rs-fMRI (BOLD signal) and ASL-MRI (cerebral blood flow) are especially affected by awake or anesthesia status (121). In addition, PET imaging in rodents, such as [18F]FDG for cerebral glucose metabolism (122) and [18F]MPPF for serotonin 1A receptor (123), is also largely influenced by anesthesia, restraint stress, and physiological stability of the animal. A key difference between rodent and human functional imaging is the use of anesthesia to reduce motion during scanning. To overcome this gap, imaging in awake behaving rodents has been increasingly reported in the two-photon optical imaging, functional ultrasound imaging, electrophysiology, PET, and MRI in the recent years (124–127). These imaging platforms enable the integration of molecular-, behavioral-level, and circuit-level understanding of the brain. However, the duration, setup, and imaging type suitable for use in awake rodents are still limited and require extensive habituation and further development.

Deep Learning in Multimodal Imaging Postprocessing

Deep learning-based methods have recently gained great momentum in both image reconstruction (128) and postprocessing (129, 130). Here, we focus on the DL application in image postprocessing with emphasis on image segmentation in a mono-modality and registration between different modalities. For a standalone modality such as MRI, DL has successfully been used in assisting the diagnosis of brain disease and analyzing the whole brain vasculature (131). Several pipelines for registration and segmentation of high-resolution mouse brain data onto brain atlases have been developed, such as aMAP (132, 133) and AMaSiNe (134). In addition to conventional manual feature extraction, the emerging applications of DL entail an enormous advancement in discovering new characteristic features in data (135–137). Given sufficient training, it can learn complex non-linear functions from high-dimensional and unstructured data (138). The potential of artificial intelligence has already been revealed in medical applications such as computerized diagnosis and prognosis (139). Regardless of sequential-mode multimodal imaging or truly hybrid systems, developing software-based algorithms for accurate and automatic registering molecular information with structural information is of high interest. For small animal PET, SPECT, CT, and MRI data, several established pipelines and commercial software such as ANTs, statistical parametric mapping (SPM), AFNI, PMOD, etc., have been established and routinely used (140–142). For OAT data, challenges remain in reconstruction processing, including segmentation and registration. Different detection configurations generate OAT images with different features. As OAT images have limited soft-tissue contrast, segmentation, and registration are thus difficult and highly dependent on the user experience. Human inputs were involved in the previously reported OAT-MRI registration methods to a certain extent, such as piecewise linear mapping algorithms (82). Gehrung et al. developed an integrated protocol for OAT-MRI registration by using a customized animal holder and landmark-based registration software (86). Ren et al. reported semiautomated OAT-MRI brain imaging data registration software that used active contour segmentation as the first step and an adaptive mutual information-based registration algorithm (84). Hu et al. developed a fully automated registration method for OAT-MRI brain imaging data registration empowered by DL, which consists of (1) two U-net-like neural networks to segment OAT and MRI images (71) and (2) an adaptive neural network to transform these generated OAT/MRI masks (reference). The accuracy and robustness of such DL-based registration have been shown to be comparable with classic methods but at a much higher speed without manual efforts on either landmark selection or boundary drawing (143).

Transcriptomics

With the affordability of single-cell sequencing, metabolomics, and transcriptomics (144–146), deep phenotyping techniques allow us to elucidate the similarities and differences in the genetics (147) and protein expression in animal models and humans (109, 148–151). Single-cell transcriptomic profiling of aging and Alzheimer’s disease combined with data from amyloid and tau PET, [18F]FDG PET, and rs-Fmri, and structural MRI to unveil the gene and macroscopic factor interactions and the biological mechanisms underlying Alzheimer’s disease (148) (Figures 2A–E). Spatially resolved transcriptomics in particular, such as fluorescence in situ hybridization, showed promising application in convergent cellular, transcriptomic, and molecular neuroimaging data (149, 152, 153). Allen brain transcriptomics mouse and human datasets provide an excellent platform for exploring the link between mice and humans, integrated with connectivity and histology data (154). Other gene expression databases, such as ‘‘Brain RNA-Seq’’1 (109) and machine-learning models to improve mouse-to-human inference ‘‘Found In Translation,’’2 non-human primate platforms (155) are available to facilitate the interpretation of experimental observations. In addition, the uptake of several tracers, such as [18F]GE-180 (for glial activation) and [18F]FDG (for cerebral glucose metabolism), is influenced by sex (156–158). Further transcriptomic analysis may reveal sex-specific molecular differences associated with the uptake of different tracers.

Organ-On-Chip Pharmacokinetics

There is a continued need for small animals as a powerful model system to advance neuroimaging and translational brain research (159). The biodistribution and pharmacokinetic information of pharmaceuticals in rodents and ex vivo target validation are prerequisites for phase 1 studies. Recent developments in organoids from induced pluripotent stem cells have introduced a paradigm shift for drug development (160). Cerebral organoids and blood–brain barrier organoids that mimic mouse or human physiology for investigating the permeability of compounds have been developed (161). With the goal of implementing the 3R principle (replacement, refinement, and reduction), recent efforts have been made to assess the behavior of imaging ligands using organ-on-chip systems employing organoids (162, 163). In addition, several recent studies reported systems for the characterization of cellular pharmacokinetics based on microfluidic systems, including a continuously infused microfluidic radioassay (164), microfluidics-coupled radioluminescence microscopy (165), and droplet-based single-cell radiometric assay (166). Further research on in vitro in vivo extrapolation will facilitate the translation and development of imaging ligands toward clinical application.

Discussion

Imaging methods that non-invasively record rapidly changing functional and molecular imaging data have been crucial for our understanding of human and small animal brains. Recent developments in optogenetics, chemogenomics, two-photon microscopy, and all optical interrogation have improved the understanding of physiological and pathological processes in the rodent brains (167–175). However, these imaging methods are limited to preclinical applications. To further improve the translational power of PET, MRI, and CT and optical imaging, we suggest the following considerations:

Standardization, Quality Assurance, and Quality Control

Standardization of imaging protocols and data analysis: The standardization of PET, CT, and MRI procedures in humans is more advanced than that in preclinical imaging and is a prerequisite for clinical trials. Even for structural MRI, scan session, head tilt, interscan interval, acquisition sequence, and processing stream have been found to influence the imaging results (176). The standardization of preclinical PET-CT/PET-MRI protocols, including CT, absorbed dose guidelines, has not been fully established. The updated ARRIVE guideline 2.0 provides a general checklist of in vivo experiments to facilitate the reproducibility of the results and methodological rigor (177, 178). Previous systematic reviews have systematically evaluated the choice of anesthetic/sedative regimen and the variation in fMRI rodent imaging (179–181). In a recent multicenter study in the United States and Europe, standardization of the preclinical PET/CT acquisition and reconstruction protocols have been shown to increase the quantitative accuracy as well as the reproducibility of imaging results (182). Similar multicenter, cross-scanner validation studies are needed for PET, SPECT, MRI, ultrasound, CT, optical imaging, hybrid imaging, and less established imaging tools, e.g., OAT or FMT. Osborne et al. proposed useful guidance for QC and scanner calibration procedures for the preclinical imaging laboratories with a balanced cost consideration (183). In the terms of data postprocessing, recent comparisons of different fMRI processing pipelines outline the importance of consensus and move beyond processing and analysis-associated variation to increase the reproducibility in human neuroimaging data (184, 185). For mouse brain imaging, recent multicenter rs-fMRI analyses have reported common functional networks in the mouse brain (186). Further comprehensive QA/QC consensuses and multicenter studies are needed for the scanner as well as for the entire pipeline, including data acquisition, reconstruction, and postprocessing to improve reproductivity and reduce variation across different studies.

Open Data Sharing

The open sharing of neuroimaging research data is critical to promote the reproducibility of scientific findings (187, 188). Large international initiatives in human brain imaging data sharing, such as ADNI (189), OpenNeuro (190), the human connectome project (191), and OASIS (192), have greatly facilitated the advancement of the research field. In contrast, less small animal neuroimaging data sharing has been achieved thus far. There is thus a need for promoting the sharing of mouse and rat neuroimaging data that are compliant with brain imaging data structure (BIDS) following the FAIR principles (193). Increasing the sample size of animal studies and cross-study comparisons add to the reliability of the findings (194).

Conclusion

In conclusion, developments in hybrid imaging, deep learning in data processing, awake animal imaging, and transcriptomics have greatly improved the translation of preclinical brain imaging. Further efforts on standardization, quality assurance/quality control, data sharing, and on-chip modeling for the translation of preclinical small animal brain imaging from bench to bedside need to be undertaken.

Author Contributions

WR and RN wrote the draft. All authors contributed to the manuscript.

Funding

WR received a start-up grant from ShanghaiTech University. RN received funding from Helmut Horten Stiftung, Vontobel Stiftung, and University of Zurich [MEDEF-20-021].

Conflict of Interest

LC is employed in Shanghai Changes Tech, Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

References

1. Finnema SJ, Nabulsi NB, Eid T, Detyniecki K, Lin SF, Chen MK, et al. Imaging synaptic density in the living human brain. Sci Transl Med. (2016) 8:348ra396. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf6667

2. Glasser MF, Coalson TS, Robinson EC, Hacker CD, Harwell J, Yacoub E, et al. A multi-modal parcellation of human cerebral cortex. Nature. (2016) 536:171–8. doi: 10.1038/nature18933

3. Poldrack RA, Farah MJ. Progress and challenges in probing the human brain. Nature. (2015) 526:371–9. doi: 10.1038/nature15692

4. Weiskopf N, Edwards LJ, Helms G, Mohammadi S, Kirilina E. Quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of brain anatomy and in vivo histology. Nat Rev Phys. (2021) 3:570–88.

5. Shah D, Jonckers E, Praet J, Vanhoutte G, Delgado y Palacios R, Bigot C, et al. Resting state fMRI reveals diminished functional connectivity in a mouse model of amyloidosis. PLoS One. (2013) 8:e84241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084241

6. Debette S, Schilling S, Duperron M-G, Larsson SC, Markus HS. Clinical significance of magnetic resonance imaging markers of vascular brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. (2019) 76:81–94. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3122

7. Dumoulin SO, Fracasso A, van der Zwaag W, Siero JCW, Petridou N. Ultra-high field MRI: advancing systems neuroscience towards mesoscopic human brain function. Neuroimage. (2018) 168:345–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.01.028

8. Triantafyllou C, Hoge RD, Krueger G, Wiggins CJ, Potthast A, Wiggins GC, et al. Comparison of physiological noise at 1.5 T, 3 T and 7 T and optimization of fMRI acquisition parameters. Neuroimage. (2005) 26:243–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.007

9. Wahsner J, Gale EM, Rodríguez-Rodríguez A, Caravan P. Chemistry of MRI contrast agents: current challenges and new Frontiers. Chem Rev. (2019) 119:957–1057. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00363

10. Lammertsma AA. Forward to the past: the case for quantitative PET imaging. J Nucl Med. (2017) 58:1019–24. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.188029

11. de Boer E, Harlaar NJ, Taruttis A, Nagengast WB, Rosenthal EL, Ntziachristos V, et al. Optical innovations in surgery. Br J Surg. (2015) 102:e56–72. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9713

12. Weber J, Beard PC, Bohndiek SE. Contrast agents for molecular photoacoustic imaging. Nat Methods. (2016) 13:639–50.

13. Deán-Ben XL, Robin J, Ni R, Razansky D. Noninvasive three-dimensional optoacoustic localization microangiography of deep tissues. arXiv. (2020) [Preprint]. arXiv:2007.00372

14. Razansky D, Buehler A, Ntziachristos V. Volumetric real-time multispectral optoacoustic tomography of biomarkers. Nat Protoc. (2011) 6:1121–9. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.351

15. Hagihara KM, Bukalo O, Zeller M, Aksoy-Aksel A, Karalis N, Limoges A, et al. Intercalated amygdala clusters orchestrate a switch in fear state. Nature. (2021) 594:403–7. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03593-1

16. Zimmer ER, Parent MJ, Cuello AC, Gauthier S, Rosa-Neto P. MicroPET imaging and transgenic models: a blueprint for Alzheimer’s disease clinical research. Trends Neurosci (2014) 37:629–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.07.002

17. Garrow AA, Andrews JPM, Gonzalez ZN, Corral CA, Portal C, Morgan TEF, et al. Preclinical dosimetry models and the prediction of clinical doses of novel positron emission tomography radiotracers. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:15985. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72830-w

18. Cheng SH, Yu D, Tsai HM, Morshed RA, Kanojia D, Lo LW, et al. Dynamic In vivo SPECT imaging of neural stem cells functionalized with radiolabeled nanoparticles for tracking of glioblastoma. J Nucl Med. (2016) 57:279–84. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.163006

19. Ho KC, Toh CH, Li SH, Liu CY, Yang CT, Lu YJ, et al. Prognostic impact of combining whole-body PET/CT and brain PET/MR in patients with lung adenocarcinoma and brain metastases. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2019) 46:467–77. doi: 10.1007/s00259-018-4210-1

20. Kadir A, Almkvist O, Forsberg A, Wall A, Engler H, Langstrom B, et al. Dynamic changes in PET amyloid and FDG imaging at different stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. (2012) 33:e191–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.06.015

21. Osmanski B, Pezet S, Ricobaraza A, Lenkei Z, Tanter M. Functional ultrasound imaging of intrinsic connectivity in the living rat brain with high spatiotemporal resolution. J Cerebr Blood F Met. (2016) 36:566–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6023

22. Razansky D, Klohs J, Ni R. Multi-scale optoacoustic molecular imaging of brain diseases. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2021) 48:4152–70. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05207-4

23. Promteangtrong C, Kolber M, Ramchandra P, Moghbel M, Houshmand S, Scholl M, et al. Multimodality imaging approaches in Alzheimer’s disease. Part II: 1H MR spectroscopy, FDG PET and amyloid PET. Dement Neuropsychol. (2015) 9:330–42. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642015DN94000330

25. Rudin M. Molecular Imaging: Basic Principles and Applications in Biomedical Research. London: Imperial College Press (2012).

26. Herfert K, Mannheim JG, Kuebler L, Marciano S, Amend M, Parl C, et al. Quantitative rodent brain receptor imaging. Mol Imaging Biol. (2020) 22:223–44. doi: 10.1007/s11307-019-01368-9

27. Judenhofer MS, Wehrl HF, Newport DF, Catana C, Siegel SB, Becker M, et al. Simultaneous PET-MRI: a new approach for functional and morphological imaging. Nat Med. (2008) 14:459–65. doi: 10.1038/nm1700

28. Miyaoka RS, Lehnert AL. Small animal PET: a review of what we have done and where we are going. Phys Med Biol. (2020) 65:24TR04. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ab8f71

29. Amirrashedi M, Zaidi H, Ay MR. Advances in preclinical PET instrumentation. PET Clin. (2020) 15:403–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cpet.2020.06.003

30. Lai Y, Wang Q, Zhou S, Xie Z, Qi J, Cherry SR, et al. H(2)RSPET: a 0.5 mm resolution high-sensitivity small-animal PET scanner, a simulation study. Phys Med Biol. (2021) 66:065016. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/abe558

31. Nagy K, Tóth M, Major P, Patay G, Egri G, Häggkvist J, et al. Performance evaluation of the small-animal nanoScan PET/MRI system. J Nucl Med. (2013) 54:1825–32. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.119065

32. Yang Y, Bec J, Zhou J, Zhang M, Judenhofer MS, Bai X, et al. A prototype high-resolution small-animal pet scanner dedicated to mouse brain imaging. J Nucl Med. (2016) 57:1130–5. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.165886

33. Fang YH, Muzic RF Jr. Spillover and partial-volume correction for image-derived input functions for small-animal 18F-FDG PET studies. J Nucl Med. (2008) 49:606–14. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.047613

34. Townsend DW, Carney JP, Yap JT, Hall NC. PET/CT today and tomorrow. J Nucl Med. (2004) 45, (Suppl. 1):4S–14S.

35. Lawrence J, Rohren E, Provenzale J. PET/CT today and tomorrow in veterinary cancer diagnosis and monitoring: fundamentals, early results and future perspectives. Vet Comp Oncol. (2010) 8:163–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5829.2010.00218.x

36. Dogdas B, Stout D, Chatziioannou AF, Leahy RM. Digimouse: a 3D whole body mouse atlas from CT and cryosection data. Phys Med Biol. (2007) 52:577–87. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/3/003

37. Lake EMR, Ge X, Shen X, Herman P, Hyder F, Cardin JA, et al. Simultaneous cortex-wide fluorescence Ca2+ imaging and whole-brain fMRI. Nat Methods. (2020) 17:1262–71.

38. Yu X, He Y, Wang M, Merkle H, Dodd SJ, Silva AC, et al. Sensory and optogenetically driven single-vessel fMRI. Nat Methods. (2016) 13:337–40. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3765

39. Zürcher NR, Walsh EC, Phillips RD, Cernasov PM, Tseng C-EJ, Dharanikota A, et al. A simultaneous [11C]raclopride positron emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging investigation of striatal dopamine binding in autism. Transl Psychiatry. (2021) 11:33. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01170-0

40. Coda AR, Anzilotti S, Boscia F, Greco A, Panico M, Gargiulo S, et al. In vivo imaging of CNS microglial activation/macrophage infiltration with combined [(18)F]DPA-714-PET and SPIO-MRI in a mouse model of relapsing remitting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2021) 48:40–52. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-04842-7

41. Grant AM, Deller TW, Khalighi MM, Maramraju SH, Delso G, Levin CS. NEMA NU 2-2012 performance studies for the SiPM-based ToF-PET component of the GE SIGNA PET/MR system. Med Phys. (2016) 43:2334. doi: 10.1118/1.4945416

42. Gsell W, Molinos C, Correcher C, Belderbos S, Wouters J, Junge S, et al. Characterization of a preclinical PET insert in a 7 tesla MRI scanner: beyond NEMA testing. Phys Med Biol. (2020) 65:245016. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aba08c

43. Hallen P, Schug D, Weissler B, Gebhardt P, Salomon A, Kiessling F, et al. PET performance evaluation of the small-animal Hyperion II(D) PET/MRI insert based on the NEMA NU-4 standard. Biomed Phys Eng Express. (2018) 4:065027. doi: 10.1088/2057-1976/aae6c2

44. Omidvari N, Cabello J, Topping G, Schneider FR, Paul S, Schwaiger M, et al. PET performance evaluation of MADPET4: a small animal PET insert for a 7 T MRI scanner. Phys Med Biol. (2017) 62:8671–92. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aa910d

45. Omidvari N, Topping G, Cabello J, Paul S, Schwaiger M, Ziegler SI. MR-compatibility assessment of MADPET4: a study of interferences between an SiPM-based PET insert and a 7 T MRI system. Phys Med Biol. (2018) 63:095002. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aab9d1

46. Schug D, Lerche C, Weissler B, Gebhardt P, Goldschmidt B, Wehner J, et al. Initial PET performance evaluation of a preclinical insert for PET/MRI with digital SiPM technology. Phys Med Biol. (2016) 61:2851–78. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/61/7/2851

47. Stortz G, Thiessen JD, Bishop D, Khan MS, Kozlowski P, Retière F, et al. Performance of a PET insert for high-resolution small-animal PET/MRI at 7 tesla. J Nucl Med. (2018) 59:536–42. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.187666

48. Liu Z, Cheng T, Düwel S, Jian Z, Topping GJ, Steiger K, et al. Proof of concept of a multimodal intravital molecular imaging system for tumour transpathology investigation. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2021). doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05574-y [Epub ahead of print].

49. Ntziachristos V, Tung CH, Bremer C, Weissleder R. Fluorescence molecular tomography resolves protease activity in vivo. Nat Med. (2002) 8:757–60. doi: 10.1038/nm729

50. Hyde D, de Kleine R, MacLaurin SA, Miller E, Brooks DH, Krucker T, et al. Hybrid FMT-CT imaging of amyloid-beta plaques in a murine Alzheimer’s disease model. Neuroimage. (2009) 44:1304–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.038

51. Ale A, Ermolayev V, Herzog E, Cohrs C, de Angelis MH, Ntziachristos V. FMT-XCT: in vivo animal studies with hybrid fluorescence molecular tomography-X-ray computed tomography. Nat Methods. (2012) 9:615–20. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2014

52. Li BQ, Maafi F, Berti R, Pouliot P, Rheaume E, Tardif JC, et al. Hybrid FMT-MRI applied to in vivo atherosclerosis imaging. Biomed Opt Express. (2014) 5:1664–76. doi: 10.1364/BOE.5.001664

53. Ren W, Isler H, Wolf M, Ripoll J, Rudin M. Smart toolkit for fluorescence tomography: simulation, reconstruction, and validation. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. (2020) 67:16–26. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2019.2907460

54. Ren W, Jiang J, Costanzo Mata AD, Kalyanov A, Ripoll J, Lindner S, et al. Multimodal imaging combining time-domain near-infrared optical tomography and continuous-wave fluorescence molecular tomography. Opt Express. (2020) 28:9860–74. doi: 10.1364/OE.385392

55. Ale A, Ermolayev V, Deliolanis NC, Ntziachristos V. Fluorescence background subtraction technique for hybrid fluorescence molecular tomography/x-ray computed tomography imaging of a mouse model of early stage lung cancer. J Biomed Opt. (2013) 18:56006. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.18.5.056006

56. Mohajerani P, Hipp A, Willner M, Marschner M, Trajkovic-Arsic M, Ma X, et al. FMT-PCCT: hybrid fluorescence molecular tomography-x-ray phase-contrast CT imaging of mouse models. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. (2014) 33:1434–46. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2014.2313405

57. Niedre M, Ntziachristos V. Elucidating structure and function in vivo with hybrid fluorescence and magnetic resonance imaging. Proc IEEE. (2008) 96:382–96. doi: 10.1109/jproc.2007.913498

58. Ren W, Ni R, Vaas M, Klohs J, Ripoll J, Wolf M, et al. Non-invasive visualization of amyloid-beta deposits in Alzheimer amyloidosis mice using magnetic resonance imaging and fluorescence molecular tomography. bioRxiv. (2021) [Preprint]. doi: 10.1101/2021.11.20.466221

59. Schulz RB, Ale A, Sarantopoulos A, Freyer M, Soehngen E, Zientkowska M, et al. Hybrid system for simultaneous fluorescence and x-ray computed tomography. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. (2010) 29:465–73. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2009.2035310

60. Davis SC, Samkoe KS, Tichauer KM, Sexton KJ, Gunn JR, Deharvengt SJ, et al. Dynamic dual-tracer MRI-guided fluorescence tomography to quantify receptor density in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2013) 110:9025–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213490110

61. Stuker F, Baltes C, Dikaiou K, Vats D, Carrara L, Charbon E, et al. Hybrid small animal imaging system combining magnetic resonance imaging with fluorescence tomography using single photon avalanche diode detectors. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. (2011) 30:1265–73. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2011.2112669

62. Davis SC, Samkoe KS, O’Hara JA, Gibbs-Strauss SL, Paulsen KD, Pogue BW. Comparing implementations of magnetic-resonance-guided fluorescence molecular tomography for diagnostic classification of brain tumors. J Biomed Opt. (2010) 15:051602. doi: 10.1117/1.3483902

63. Ren W, Elmer A, Buehlmann D, Augath M-A, Vats D, Ripoll J, et al. Dynamic measurement of tumor vascular permeability and perfusion using a hybrid system for simultaneous magnetic resonance and fluorescence imaging. Mol Imaging Biol. (2016) 18:191–200. doi: 10.1007/s11307-015-0884-y

64. Meng B, Folaron MR, Strawbridge RR, Sadeghipour N, Samkoe KS, Tichauer K, et al. Noninvasive quantification of target availability during therapy using paired-agent fluorescence tomography. Theranostics. (2020) 10:11230–43. doi: 10.7150/thno.45273

65. Kneipp M, Turner J, Estrada H, Rebling J, Shoham S, Razansky D. Effects of the murine skull in optoacoustic brain microscopy. J Biophotonics. (2016) 9:117–23. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201400152

66. Wang LV, Hu S. Photoacoustic tomography: in vivo imaging from organelles to organs. Science. (2012) 335:1458. doi: 10.1126/science.1216210

67. Gottschalk S, Degtyaruk O, Mc Larney B, Rebling J, Hutter MA, Deán-Ben XL, et al. Rapid volumetric optoacoustic imaging of neural dynamics across the mouse brain. Nat Biomed Eng. (2019) 3:392–401.

68. Lv J, Li S, Zhang J, Duan F, Wu Z, Chen R, et al. In vivo photoacoustic imaging dynamically monitors the structural and functional changes of ischemic stroke at a very early stage. Theranostics. (2020) 10:816–28. doi: 10.7150/thno.38554

69. Ni R, Rudin M, Klohs J. Cortical hypoperfusion and reduced cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen in the arcAβ mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Photoacoustics. (2018) 10:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2018.04.001

70. Ni R, Villois A, Dean-Ben XL, Chen Z, Vaas M, Stavrakis S, et al. In-vitro and in-vivo characterization of CRANAD-2 for multi-spectral optoacoustic tomography and fluorescence imaging of amyloid-beta deposits in Alzheimer mice. Photoacoustics. (2021) 23:100285. doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2021.100285

71. Lafci B, Mercep E, Morscher S, Dean-Ben XL, Razansky D. Deep learning for automatic segmentation of hybrid optoacoustic ultrasound (OPUS) images. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control PP. (2020) 68:688–96. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2020.3022324

72. McNally LR, Mezera M, Morgan DE, Frederick PJ, Yang ES, Eltoum IE, et al. Current and emerging clinical applications of multispectral optoacoustic tomography (MSOT) in oncology. Clin Cancer Res. (2016) 22:3432–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0573

73. Mercep E, Dean-Ben XL, Razansky D. Combined pulse-echo ultrasound and multispectral optoacoustic tomography with a multi-segment detector array. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. (2017) 36:2129–37. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2017.2706200

74. Cheng Y, Lu T, Wang YD, Song YL, Wang SY, Lu QL, et al. Glutathione–mediated clearable nanoparticles based on ultrasmall Gd2O3 for MSOT/CT/MR imaging guided photothermal/radio combination cancer therapy. Mol Pharmaceut. (2019) 16:3489–501. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00332

75. Ke KM, Yang W, Xie XL, Liu R, Wang LL, Lin WW, et al. Copper manganese sulfide nanoplates: a new two-dimensional theranostic nanoplatform for MRI/MSOT dual-modal imaging-guided photothermal therapy in the second near-infrared window. Theranostics. (2017) 7:4763–76. doi: 10.7150/thno.21694

76. Song YL, Wang YL, Zhu Y, Cheng Y, Wang YD, Wang SY, et al. Biomodal tumor-targeted and redox-responsive Bi2Se3 hollow nanocubes for MSOT/CT imaging guided synergistic low-temperature photothermal radiotherapy. Adv Healthc Mater. (2019) 8:e1900250. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201900250

77. Vaas M, Ni R, Rudin M, Kipar A, Klohs J. Extracerebral tissue damage in the intraluminal filament mouse model of middle cerebral artery occlusion. Front Neurol. (2017) 8:85. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2017.00085

78. Wang SY, You Q, Wang JP, Song YL, Cheng Y, Wang YD, et al. MSOT/CT/MR imaging-guided and hypoxia-maneuvered oxygen self-supply radiotherapy based on one-pot MnO2-mSiO(2)@Au nanoparticles. Nanoscale. (2019) 11:6270–84. doi: 10.1039/c9nr00918c

79. Yang S, You Q, Yang LF, Li PS, Lu QL, Wang SY, et al. Rodlike MSN@Au nanohybrid-modified supermolecular photosensitizer for NIRF/MSOT/CT/MR quadmodal imaging-guided photothermal/photodynamic cancer therapy. Acs Appl Mater Inter. (2019) 11:6777–88. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b19565

80. Ni R, Dean-Ben XL, Kirschenbaum D, Rudin M, Chen Z, Crimi A, et al. Whole brain optoacoustic tomography reveals strain-specific regional beta-amyloid densities in Alzheimer’s disease amyloidosis models. bioRxiv. (2020) [Preprint]. doi: 10.1101/2020.02.25.964064

81. Zhang S, Qi L, Li X, Liang Z, Wu J, Huang S, et al. In vivo co-registered hybrid-contrast imaging by successive photoacoustic tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. bioRxiv (2021) [Preprint]. doi: 10.1101/2021.03.06.434031

82. Attia ABE, Ho CJH, Chandrasekharan P, Balasundaram G, Tay HC, Burton NC, et al. Multispectral optoacoustic and MRI coregistration for molecular imaging of orthotopic model of human glioblastoma. J Biophotonics. (2016) 9:701–8. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201500321

83. Ni R, Vaas M, Ren W, Klohs J. Noninvasive detection of acute cerebral hypoxia and subsequent matrix-metalloproteinase activity in a mouse model of cerebral ischemia using multispectral-optoacoustic-tomography. Neurophotonics. (2018) 5:015005. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.5.1.015005

84. Ren W, Skulason H, Schlegel F, Rudin M, Klohs J, Ni R. Automated registration of magnetic resonance imaging and optoacoustic tomography data for experimental studies. Neurophotonics. (2019) 6:025001. doi: 10.1117/1.NPh.6.2.025001

85. Vagenknecht P, Luzgin A, Ono M, Ji B, Higuchi M, Noain D, et al. Non-invasive imaging of tau-targeted probe uptake by whole brain multi-spectral optoacoustic tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2022). doi: 10.1007/s00259-022-05708-w [Epub ahead of print].

86. Gehrung M, Tomaszewski M, McIntyre D, Disselhorst J, Bohndiek S. Co-registration of optoacoustic tomography and magnetic resonance imaging data from murine tumour models. Photoacoustics. (2020) 18:100147. doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2019.100147

87. Ren W, Dean-Ben XL, Augath MA, Razansky D. Development of concurrent magnetic resonance imaging and volumetric optoacoustic tomography: a phantom feasibility study. J Biophotonics. (2021) 14:e202000293. doi: 10.1002/jbio.202000293

88. Blockley NP, Griffeth VEM, Simon AB, Buxton RB. A review of calibrated blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) methods for the measurement of task-induced changes in brain oxygen metabolism. Nmr Biomed. (2013) 26:987–1003. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2847

89. Garcia-Uribe A, Erpelding TN, Krumholz A, Ke H, Maslov K, Appleton C, et al. Dual-modality photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging system for noninvasive sentinel lymph node detection in patients with breast cancer. Sci Rep. (2015) 5:15748. doi: 10.1038/srep15748

90. Knieling F, Neufert C, Hartmann A, Claussen J, Urich A, Egger C, et al. Multispectral optoacoustic tomography for assessment of crohn’s disease activity. N Engl J Med. (2017) 376:1292–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1612455

91. Masthoff M, Helfen A, Claussen J, Karlas A, Markwardt NA, Ntziachristos V, et al. Use of multispectral optoacoustic tomography to diagnose vascular malformations. JAMA Dermatol. (2018) 154:1457–62. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3269

92. Chang K-W, Zhu Y, Hudson HM, Barbay S, Guggenmos DJ, Nudo RJ, et al. Photoacoustic imaging of squirrel monkey cortical and subcortical brain regions during peripheral electrical stimulation. Photoacoustics. (2022) 25:100326. doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2021.100326

93. Mahmoodkalayeh S, Kratkiewicz K, Manwar R, Shahbazi M, Ansari MA, Natarajan G, et al. Wavelength and pulse energy optimization for detecting hypoxia in photoacoustic imaging of the neonatal brain: a simulation study. Biomed Opt Express. (2021) 12:7458–77. doi: 10.1364/BOE.439147

94. Na S, Russin JJ, Lin L, Yuan X, Hu P, Jann KB, et al. Massively parallel functional photoacoustic computed tomography of the human brain. Nat Biomed Eng. (2021). doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00735-8 [Epub ahead of print].

95. Na S, Wang LV. Photoacoustic computed tomography for functional human brain imaging [Invited]. Biomed Opt Express. (2021) 12:4056–83. doi: 10.1364/BOE.423707

96. Nie L, Cai X, Maslov K, Garcia-Uribe A, Anastasio MA, Wang LV. Photoacoustic tomography through a whole adult human skull with a photon recycler. J Biomed Opt. (2012) 17:110506. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.11.110506

97. Blocker SJ, Mowery YM, Holbrook MD, Qi Y, Kirsch DG, Johnson GA, et al. Bridging the translational gap: implementation of multimodal small animal imaging strategies for tumor burden assessment in a co-clinical trial. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0207555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207555

98. O’Connor JPB, Aboagye EO, Adams JE, Aerts HJWL, Barrington SF, Beer AJ, et al. Imaging biomarker roadmap for cancer studies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2017) 14:169–86. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.162

99. Kaufmann TJ, Smits M, Boxerman J, Huang R, Barboriak DP, Weller M, et al. Consensus recommendations for a standardized brain tumor imaging protocol for clinical trials in brain metastases. Neuro Oncol. (2020) 22:757–72. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noaa030

100. Waterhouse DJ, Fitzpatrick CRM, Pogue BW, O’Connor JPB, Bohndiek SE. A roadmap for the clinical implementation of optical-imaging biomarkers. Nat Biomed Eng. (2019) 3:339–53. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0392-5

101. Shaw RC, Tamagnan GD, Tavares AAS. Rapidly (and Successfully) translating novel brain radiotracers from animal research into clinical use. Front Neurosci. (2020) 14:871. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2020.00871

102. Rothstein JD. Of mice and men: reconciling preclinical ALS mouse studies and human clinical trials. Ann Neurol. (2003) 53:423–6. doi: 10.1002/ana.10561

103. de Jong M, Essers J, van Weerden WM. Imaging preclinical tumour models: improving translational power. Nat Rev Cancer. (2014) 14:481–93. doi: 10.1038/nrc3751

104. Zahs KR, Ashe KH. ‘Too much good news’ – are Alzheimer mouse models trying to tell us how to prevent, not cure, Alzheimer’s disease? Trends Neurosci. (2010) 33:381–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.05.004

105. Beaulieu-Laroche L, Brown NJ, Hansen M, Toloza EHS, Sharma J, Williams ZM, et al. Allometric rules for mammalian cortical layer 5 neuron biophysics. Nature. (2021) 600:274–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04072-3

106. Van Essen DC, Donahue CJ, Coalson TS, Kennedy H, Hayashi T, Glasser MF. Cerebral cortical folding, parcellation, and connectivity in humans, nonhuman primates, and mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2019) 116:26173–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1902299116

107. Li J, Pan L, Pembroke WG, Rexach JE, Godoy MI, Condro MC, et al. Conservation and divergence of vulnerability and responses to stressors between human and mouse astrocytes. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:3958. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24232-3

108. Zhou Y, Song WM, Andhey PS, Swain A, Levy T, Miller KR, et al. Human and mouse single-nucleus transcriptomics reveal TREM2-dependent and TREM2-independent cellular responses in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. (2020) 26:131–42. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0695-9

109. Zhang Y, Sloan SA, Clarke LE, Caneda C, Plaza CA, Blumenthal PD, et al. Purification and characterization of progenitor and mature human astrocytes reveals transcriptional and functional differences with mouse. Neuron. (2016) 89:37–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.013

110. Majid A, He YY, Gidday JM, Kaplan SS, Gonzales ER, Park TS, et al. Differences in vulnerability to permanent focal cerebral ischemia among 3 common mouse strains. Stroke. (2000) 31:2707–14. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.11.2707

111. Zhao L, Mulligan MK, Nowak TS Jr. Substrain- and sex-dependent differences in stroke vulnerability in C57BL/6 mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2019) 39:426–38. doi: 10.1177/0271678X17746174

112. Bailey RM, Howard J, Knight J, Sahara N, Dickson DW, Lewis J. Effects of the C57BL/6 strain background on tauopathy progression in the rTg4510 mouse model. Mol Neurodegener. (2014) 9:8. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-8

113. Walker LC, Jucker M. The exceptional vulnerability of humans to Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Mol Med. (2017) 23:534–45. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2017.04.001

114. Denny P, Justice MJ. Mouse as the measure of man? Trends Genet. (2000) 16:283–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02039-4

115. Holec SAM, Woerman AL. Evidence of distinct α-synuclein strains underlying disease heterogeneity. Acta Neuropathol. (2021) 142:73–86. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02163-5

116. Ni R, Ji B, Ono M, Sahara N, Zhang MR, Aoki I, et al. Comparative in vitro and in vivo quantifications of pathologic tau deposits and their association with neurodegeneration in tauopathy mouse models. J Nucl Med. (2018) 59:960–6. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.201632

117. Rosen RF, Walker LC, Levine H III. PIB binding in aged primate brain: enrichment of high-affinity sites in humans with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. (2011) 32:223–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.02.011

118. Jung KO, Kim TJ, Yu JH, Rhee S, Zhao W, Ha B, et al. Whole-body tracking of single cells via positron emission tomography. Nat Biomed Eng. (2020) 4:835–44. doi: 10.1038/s41551-020-0570-5

119. Nutma E, Ceyzériat K, Amor S, Tsartsalis S, Millet P, Owen DR, et al. Cellular sources of TSPO expression in healthy and diseased brain. Eur J. Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2021) 49:146–63. doi: 10.1007/s00259-020-05166-2

120. Tournier BB, Tsartsalis S, Ceyzériat K, Medina Z, Fraser BH, Grégoire MC, et al. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting to reveal the cell origin of radioligand binding. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. (2020) 40:1242–55. doi: 10.1177/0271678X19860408

121. Tremoleda JL, Kerton A, Gsell W. Anaesthesia and physiological monitoring during in vivo imaging of laboratory rodents: considerations on experimental outcomes and animal welfare. EJNMMI Res. (2012) 2:44. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-2-44

122. Deleye S, Waldron AM, Richardson JC, Schmidt M, Langlois X, Stroobants S, et al. The effects of physiological and methodological determinants on 18F-FDG mouse brain imaging exemplified in a double transgenic Alzheimer model. Mol Imaging. (2016) 15:1536012115624919. doi: 10.1177/1536012115624919

123. Buchecker V, Waldron AM, van Dijk RM, Koska I, Brendel M, von Ungern-Sternberg B, et al. [(18)F]MPPF and [(18)F]FDG μPET imaging in rats: impact of transport and restraint stress. EJNMMI Res. (2020) 10:112.

124. Chen X, Tong C, Han Z, Zhang K, Bo B, Feng Y, et al. Sensory evoked fMRI paradigms in awake mice. Neuroimage. (2020) 204:116242. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116242

125. Kenkel WM, Yee JR, Moore K, Madularu D, Kulkarni P, Gamber K, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging in awake transgenic fragile X rats: evidence of dysregulation in reward processing in the mesolimbic/habenular neural circuit. Transl Psychiatry. (2016) 6:e763–763. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.15

126. Miranda A, Glorie D, Bertoglio D, Vleugels J, De Bruyne G, Stroobants S, et al. Awake (18)F-FDG PET Imaging of memantine-induced brain activation and test-retest in freely running mice. J Nucl Med. (2019) 60:844–50. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.118.218669

127. Tsurugizawa T, Tamada K, Ono N, Karakawa S, Kodama Y, Debacker C, et al. Awake functional MRI detects neural circuit dysfunction in a mouse model of autism. Sci Adv. (2020) 6:eaav4520. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aav4520

128. Wang G, Ye JC, Mueller K, Fessler JA. Image reconstruction is a new Frontier of machine learning. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. (2018) 37:1289–96. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2018.2833635

129. Hakim A, Christensen S, Winzeck S, Lansberg MG, Parsons MW, Lucas C, et al. Predicting infarct core from computed tomography perfusion in acute ischemia with machine learning: lessons from the ISLES challenge. Stroke. (2021) 52:2328–37. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030696

130. Katabathula S, Wang Q, Xu R. Predict Alzheimer’s disease using hippocampus MRI data: a lightweight 3D deep convolutional network model with visual and global shape representations. Alzheimers Res Ther. (2021) 13:104. doi: 10.1186/s13195-021-00837-0

131. Todorov MI, Paetzold JC, Schoppe O, Tetteh G, Shit S, Efremov V, et al. Machine learning analysis of whole mouse brain vasculature. Nat Methods. (2020) 17:442–9. doi: 10.1038/s41592-020-0792-1

132. Lein ES, Hawrylycz MJ, Ao N, Ayres M, Bensinger A, Bernard A, et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. (2007) 445:168–76.

133. Niedworok CJ, Brown APY, Jorge Cardoso M, Osten P, Ourselin S, Modat M, et al. aMAP is a validated pipeline for registration and segmentation of high-resolution mouse brain data. Nat Commun. (2016) 7:11879. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11879

134. Song JH, Choi W, Song Y-H, Kim J-H, Jeong D, Lee S-H, et al. Precise mapping of single neurons by calibrated 3D reconstruction of brain slices reveals topographic projection in mouse visual cortex. Cell Rep. (2020) 31:107682. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107682

135. Esser SK, Merolla PA, Arthur JV, Cassidy AS, Appuswamy R, Andreopoulos A, et al. Convolutional networks for fast, energy-efficient neuromorphic computing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2016) 113:11441–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604850113

136. Ithapu VK, Singh V, Okonkwo OC, Chappell RJ, Dowling NM, Johnson SC. Imaging-based enrichment criteria using deep learning algorithms for efficient clinical trials in mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. (2015) 11:1489–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.01.010

138. Sengupta S, Basak S, Saikia P, Paul S, Tsalavoutis V, Atiah F, et al. A review of deep learning with special emphasis on architectures, applications and recent trends. Knowl Based Syst. (2020) 194:105596. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2020.5063

139. Suk HI, Lee SW, Shen D. Latent feature representation with stacked auto-encoder for AD/MCI diagnosis. Brain Struct Funct. (2015) 220:841–59. doi: 10.1007/s00429-013-0687-3

140. Avants BB, Tustison N, Song G. Advanced normalization tools (ANTS). Insight J. (2009) 2:1–35. doi: 10.1007/s11682-020-00319-1

141. Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. (1996) 29:162–73.

142. Penny WD, Friston KJ, Ashburner JT, Kiebel SJ, Nichols TE. Statistical Parametric Mapping: The Analysis of Functional Brain Images. Amsterdam: Elsevier (2011).

143. Hu Y, Lafci B, Luzgin A, Wang H, Klohs J, Dean-Ben XL, et al. Deep learning facilitates fully automated brain image registration of optoacoustic tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. arXiv. (2021) [Preprint]. arXiv:2109.01880.

144. Argelaguet R, Cuomo ASE, Stegle O, Marioni JC. Computational principles and challenges in single-cell data integration. Nat Biotechnol. (2021) 39:1202–15. doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-00895-7

145. Dhar R, Falcone GJ, Chen Y, Hamzehloo A, Kirsch EP, Noche RB, et al. Deep learning for automated measurement of hemorrhage and perihematomal edema in supratentorial intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. (2020) 51:648–51. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.027657

146. Yu Y, Xie Y, Thamm T, Gong E, Ouyang J, Huang C, et al. Use of deep learning to predict final ischemic stroke lesions from initial magnetic resonance imaging. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e200772. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0772

147. Tecott LH. The genes and brains of mice and men. Am J Psychiatry. (2003) 160:646–56. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.646

148. Adewale Q, Khan AF, Carbonell F, Iturria-Medina Y. Integrated transcriptomic and neuroimaging brain model decodes biological mechanisms in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Elife. (2021) 10:e62589. doi: 10.7554/eLife.62589

149. Martins D, Giacomel A, Williams S, Turkheimer F, Dipasquale O, Veronese M. Imaging transcriptomics: Convergent cellular, transcriptomic, and molecular neuroimaging signatures in the healthy adult human brain. Cell Rep. (2021) 37:110173. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110173

150. Ximerakis M, Lipnick SL, Innes BT, Simmons SK, Adiconis X, Dionne D, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic profiling of the aging mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. (2019) 22:1696–708. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0491-3

151. Zhang Y, Chen K, Sloan SA, Bennett ML, Scholze AR, Keeffe S, et al. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. (2014) 34:11929. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014

152. Girgenti MJ, Wang J, Ji D, Cruz DA, Alvarez VE, Benedek D. Transcriptomic organization of the human brain in post-traumatic stress disorder. Nat Neurosci. (2021) 24:24–33. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00748-7

153. Su JH, Zheng P, Kinrot SS, Bintu B, Zhuang X. Genome-scale imaging of the 3D organization and transcriptional activity of chromatin. Cell. (2020) 182:1641.e–59.e. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.032

154. Tasic B, Yao Z, Graybuck LT, Smith KA, Nguyen TN, Bertagnolli D, et al. Shared and distinct transcriptomic cell types across neocortical areas. Nature. (2018) 563:72–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0654-5

155. Messinger A, Sirmpilatze N, Heuer K, Loh KK, Mars RB, Sein J, et al. A collaborative resource platform for non-human primate neuroimaging. NeuroImage. (2021) 226:117519. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117519

156. Biechele G, Franzmeier N, Blume T, Ewers M, Luque JM, Eckenweber F, et al. Glial activation is moderated by sex in response to amyloidosis but not to tau pathology in mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases. J Neuroinflammation. (2020) 17:374. doi: 10.1186/s12974-020-02046-2

157. Chan SR, Salem K, Jeffery J, Powers GL, Yan Y, Shoghi KI, et al. Sex as a biologic variable in preclinical imaging research: initial observations with (18)F-FLT. J Nucl Med. (2018) 59:833–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.117.199406

158. Hu Y, Xu Q, Li K, Zhu H, Qi R, Zhang Z, et al. Gender differences of brain glucose metabolic networks revealed by FDG-PET: evidence from a large cohort of 400 young adults. PLoS One (2013) 8:e83821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083821

159. Homberg JR, Adan RAH, Alenina N, Asiminas A, Bader M, Beckers T, et al. The continued need for animals to advance brain research. Neuron. (2021) 109:2374–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2021.07.015

160. Ma C, Peng Y, Li H, Chen W. Organ-on-a-chip: a new paradigm for drug development. Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2021) 42:119–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2020.11.009

161. Bergmann S, Lawler SE, Qu Y, Fadzen CM, Wolfe JM, Regan MS, et al. Blood-brain-barrier organoids for investigating the permeability of CNS therapeutics. Nat Protoc. (2018) 13:2827–43. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0066-x

163. Herland A, Maoz BM, Das D, Somayaji MR, Prantil-Baun R, Novak R, et al. Quantitative prediction of human pharmacokinetic responses to drugs via fluidically coupled vascularized organ chips. Nat Biomed Eng. (2020) 4:421–36.

164. Liu Z, Jian Z, Wang Q, Cheng T, Feuerecker B, Schwaiger M, et al. A continuously infused microfluidic radioassay system for the characterization of cellular pharmacokinetics. J Nucl Med. (2016) 57:1548–55. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.169151

165. Kim TJ, Ha B, Bick AD, Kim M, Tang SKY, Pratx G. Microfluidics-coupled radioluminescence microscopy for in vitro radiotracer kinetic studies. Anal Chem. (2021) 93:4425–33. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c04321

166. Gallina ME, Kim TJ, Shelor M, Vasquez J, Mongersun A, Kim M, et al. Toward a droplet-based single-cell radiometric assay. Anal Chem. (2017) 89:6472–81. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b00414

167. Banerjee A, Parente G, Teutsch J, Lewis C, Voigt FF, Helmchen F. Value–guided remapping of sensory cortex by lateral orbitofrontal cortex. Nature. (2020) 585:245–50. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2704-z

168. Barson D, Hamodi AS, Shen X, Lur G, Constable RT, Cardin JA, et al. Simultaneous mesoscopic and two-photon imaging of neuronal activity in cortical circuits. Nat Methods. (2020) 17:107–13. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0625-2

169. Bottes S, Jaeger BN, Pilz GA, Jörg DJ, Cole JD, Kruse M, et al. Long-term self-renewing stem cells in the adult mouse hippocampus identified by intravital imaging. Nat Neurosci. (2021) 24:225–33. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00759-4

170. Jun JJ, Steinmetz NA, Siegle JH, Denman DJ, Bauza M, Barbarits B, et al. Fully integrated silicon probes for high-density recording of neural activity. Nature. (2017) 551:232–6. doi: 10.1038/nature24636

171. Pilz GA, Bottes S, Betizeau M, Jörg DJ, Carta S, Simons BD, et al. Live imaging of neurogenesis in the adult mouse hippocampus. Science. (2018) 359:658–62. doi: 10.1126/science.aao5056

172. Seiriki K, Kasai A, Hashimoto T, Schulze W, Niu M, Yamaguchi S, et al. High-speed and scalable whole-brain imaging in rodents and primates. Neuron. (2017) 94:1085.e–100.e. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.05.017

173. Sun Q, Li X, Ren M, Zhao M, Zhong Q, Ren Y, et al. A whole-brain map of long-range inputs to GABAergic interneurons in the mouse medial prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. (2019) 22:1357–70. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0429-9

174. Wang T, Ouzounov DG, Wu C, Horton NG, Zhang B, Wu CH, et al. Three-photon imaging of mouse brain structure and function through the intact skull. Nat Methods. (2018) 15:789–92. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0115-y

175. Zong W, Wu R, Chen S, Wu J, Wang H, Zhao Z, et al. Miniature two-photon microscopy for enlarged field-of-view, multi-plane and long-term brain imaging. Nat Methods. (2021) 18:46–9.

176. Hedges EP, Dimitrov M, Zahid U, Vega BB, Si S, Dickson H, et al. Reliability of structural MRI measurements: the effects of scan session, head tilt, inter-scan interval, acquisition sequence, FreeSurfer version and processing stream. Neuroimage. (2021) 246:118751. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118751

177. Percie du Sert N, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, et al. Reporting animal research: Explanation and elaboration for the ARRIVE guidelines 2.0. PLoS Biol. (2020) 18:e3000411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000411

178. Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. (2020) 18:e3000410.

179. Reimann HM, Niendorf T. The (Un)conscious mouse as a model for human brain functions: key principles of anesthesia and their impact on translational neuroimaging. Front Syst Neurosci. (2020) 14:8. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2020.00008

180. Steiner AR, Rousseau-Blass F, Schroeter A, Hartnack S, Bettschart-Wolfensberger R. Systematic review: anaesthetic protocols and management as confounders in rodent blood oxygen level dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging (BOLD fMRI)-part A: effects of changes in physiological parameters. Front Neurosci. (2020) 14:577119.

181. Steiner AR, Rousseau-Blass F, Schroeter A, Hartnack S, Bettschart-Wolfensberger R. Systematic review: anesthetic protocols and management as confounders in rodent blood oxygen level dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging (BOLD fMRI)—part B: effects of anesthetic agents, doses and timing. Animals. (2021) 11:199. doi: 10.3390/ani11010199

182. McDougald W, Vanhove C, Lehnert A, Lewellen B, Wright J, Mingarelli M, et al. Standardization of preclinical PET/CT imaging to improve quantitative accuracy, precision, and reproducibility: a multicenter study. J Nucl Med. (2020) 61:461–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.119.231308

183. Osborne DR, Kuntner C, Berr S, Stout D. Guidance for efficient small animal imaging quality control. Mol Imaging Biol. (2017) 19:485–98.

184. Botvinik-Nezer R, Holzmeister F, Camerer CF, Dreber A, Huber J, Johannesson M, et al. Variability in the analysis of a single neuroimaging dataset by many teams. Nature. (2020) 582:84–8.

185. Li X, Ai L, Giavasis S, Jin H, Feczko E, Xu T, et al. Moving beyond processing and analysis-related variation in neuroscience. bioRxiv. (2021) [Preprint]. doi: 10.1101/2021.12.01.470790

186. Grandjean J, Canella C, Anckaerts C, Ayrancı G, Bougacha S, Bienert T, et al. Common functional networks in the mouse brain revealed by multi-centre resting-state fMRI analysis. Neuroimage. (2020) 205:116278.

187. Gau R, Noble S, Heuer K, Bottenhorn KL, Bilgin IP, Yang YF, et al. Brainhack: Developing a culture of open, inclusive, community-driven neuroscience. Neuron. (2021) 109:1769–75.

188. Poldrack RA, Gorgolewski KJ. Making big data open: data sharing in neuroimaging. Nat Neurosci. (2014) 17:1510–7.

189. Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Donohue MC, Gamst AC, Harvey DJ, et al. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology. (2010) 74:201–9.

190. Markiewicz CJ, Gorgolewski KJ, Feingold F, Blair R, Halchenko YO, Miller E, et al. The OpenNeuro resource for sharing of neuroscience data. Elife. (2021) 10:e71774.

191. Van Essen DC, Smith SM, Barch DM, Behrens TE, Yacoub E, Ugurbil K. The WU-minn human connectome project: an overview. Neuroimage. (2013) 80:62–79.

192. LaMontagne PJ, Benzinger TLS, Morris JC, Keefe S, Hornbeck R, Xiong C, et al. OASIS-3: longitudinal neuroimaging, clinical, and cognitive dataset for normal aging and alzheimer disease. medRxiv. (2019) [Preprint]. doi: 10.1101/2019.12.13.19014902

193. Gorgolewski KJ, Auer T, Calhoun VD, Craddock RC, Das S, Duff EP, et al. The brain imaging data structure, a format for organizing and describing outputs of neuroimaging experiments. Sci Data. (2016) 3:160044.

Keywords: deep learning, magnetic resonance imaging, multimodal imaging, neuroimaging, positron emission tomography, optoacoustic imaging, image registration, fluorescence imaging

Citation: Ren W, Ji B, Guan Y, Cao L and Ni R (2022) Recent Technical Advances in Accelerating the Clinical Translation of Small Animal Brain Imaging: Hybrid Imaging, Deep Learning, and Transcriptomics. Front. Med. 9:771982. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.771982

Received: 07 September 2021; Accepted: 16 February 2022;

Published: 24 March 2022.

Edited by:

Adriana Tavares, University of Edinburgh, United KingdomReviewed by:

Sridhar Goud, National Institutes of Health (NIH), United StatesSonia Waiczies, Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association, Germany

Kuangyu Shi, University of Bern, Switzerland

Copyright © 2022 Ren, Ji, Guan, Cao and Ni. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wuwei Ren, cmVud3dAc2hhbmdoYWl0ZWNoLmVkdS5jbg==; Ruiqing Ni, cnVpcWluZy5uaUB1emguY2g=

Wuwei Ren

Wuwei Ren Bin Ji

Bin Ji Yihui Guan

Yihui Guan Lei Cao

Lei Cao Ruiqing Ni

Ruiqing Ni