95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

Front. Med. , 05 January 2023

Sec. Geriatric Medicine

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.1069846

This article is part of the Research Topic Caregivers of Older Individuals: Reflections about Living, Health, Work and Social Conditions View all 9 articles

Objectives: Enrichment, defined as “the process of endowing caregiving with meaning or pleasure for both the caregiver and care recipient” can support relationships between people living with dementia (PLWD) and their caregivers. This study aims to explore (1) the types of psychosocial interventions that may enrich relationships between dementia caregiving dyads, and (2) the components within these psychosocial interventions that may contribute to enrichment.

Methods: A scoping review was conducted based on the Joanna Briggs Institute framework. We operationalized and contextualized core elements from Cartwright and colleagues’ enrichment model, which was also used to guide the review. Five electronic databases were searched. Psychosocial intervention components contributing to enrichment were identified and grouped within each core element.

Results: Thirty-four studies were included. Psychosocial interventions generating enrichment among dyads mainly involved supporting dyadic engagement in shared activities, carer education or training, or structural change to the environment around PLWD. Intervention components contributing to the enrichment of dyadic relationships were identified within “acquired symbolic meaning”, “performing activity”, and “fine tuning”. Dyadic communication support and skill-building were common contributors to enrichment.

Conclusion: Our findings may inform the planning and development of interventions to enrich dyadic relationships in the context of dementia. In formal caregiving contexts, future interventions may consider dedicating space for relationships to build and grow through positive interactions. In informal caregiving contexts, existing relationships should be considered to better support dyads engage in positive interactions.

As described by Kitwood (1, 2), person-centered care has been adopted as the main principle of dementia care. A central theme within the person-centered care model entails safeguarding the “personhood” of individuals with dementia, defined as “a standing or status bestowed upon human beings by others in the context of relationship and social being” (2) (p. 8). Although fundamental elements of personhood include the capacity to form and hold relationships, current person-centered interventions for people living with dementia (PLWD) have been criticized for being implicitly individualistic (3, 4) and insufficiently including the caregivers of PLWD (4–6). By considering the needs of each member of the caregiving dyad [defined as “a caregiving relationship consisting of a caregiver and a care recipient” (7)] separately (8), few existing interventions attempt to “enrich” their caregiving relationship through positive shared experiences (9). Around the beginning of this century, Snyder (10) and Lawrence (11) argued that caregiving relationships in dementia were largely overlooked, where few studies explored the dynamics between the dyad members. Since then, relationship-centered approaches have gained increasing recognition in caregiving by adequately including the relational dynamic between the care recipient and caregiver (12, 13).

As dementia progresses, the cognitive and functional changes in PLWD often lead to changing relationship dynamics with their caregivers (14), regardless of whether the caregiver is formal (i.e., paid) or informal (i.e., unpaid). Informal caregivers (e.g., family members or friends) might feel they are caring for someone other than the person they once knew (14). Although informal caregivers face challenges, losses, and negative experiences when caring for a loved one with dementia, these impacts may be lessened by continuing positives within the relationship (15–17). Furthermore, psychosocial interventions that support relationship sustenance can help the caregiving dyad to adapt and live well with the condition (18, 19). Also, in a formal caregiving context, such as long-term care (LTC) facilities (e.g., nursing homes), the common symptoms and dementia trajectory influence the conventional relationship between the PLWD and the formal caregiver (e.g., care staff). Despite dynamic healthcare environments, including staff rotations and turnover, the nature of the caregiving activities and residents’ length of stay constitute a unique setting for building relationships between caregivers and care recipients. This, in turn, directly impacts the experience of both PLWD and caregivers (20). Meaningful nurse-resident relationships in LTC have been associated with staff retention (20–22), highlighting the value of relationship-centered care in providing formal staff with a sense of purpose during caregiving. This notion is supported by Killick and Allan, who argue that formal caregivers generally deeply value the connections and relationships they make with their patients (23). Returning to Kitwood’s person-centered care model, personhood has been found to be sustained in relationships where both caregiver and care recipient experience a close emotional bond (24–26).

Regardless of the underlying theoretical concept, facilitating opportunities for PLWD to connect with caregivers is considered an imperative goal for psychosocial interventions (27–29), arguing for increased focus on activities that enrich the caregiving dyad and enhance the positive aspects of the caregiving relationship when coping with dementia. Maintaining social relationships in dementia is also one of the cornerstones in the work of the INTERDEM Social Health Taskforce, a European interdisciplinary collaborative research network focusing on psychosocial interventions in dementia (30–34). In their operationalization of “Social Health”, they postulate this concept as a possible driver for accessing cognitive reserve in PLWD through active facilitation and utilization of social and environmental resources (34). Furthermore, the INTERDEM Social Health Taskforce argues that interventions focusing on improving or maintaining social relationships in dementia can have beneficial effects on social interactions as well as on clinical and social outcomes for PLWD (30, 31). There is a growing body of research measuring relationship quality in caregiving dyads as an outcome of psychosocial interventions. In addition, there is an increased interest in using enriching activities and caregiving focusing on the interactive capabilities of PLWD, which have been shown to provide important ways to enhance social connections (9, 18, 19, 35–37).

However, what constitutes enriching activities? Following the developed definition by Cartwright and colleagues in 1994, we define enrichment in the context of care as “the process of endowing caregiving with meaning or pleasure for both caregiver and care recipient” (29) (p. 32). Nevertheless, the concept of enrichment in dementia caregiving remains unclear. A variety of terminologies has been used to describe different forms of enrichment in dementia caregiving, such as meaningful (20, 38, 39), rewarding (15, 40, 41), connecting (42–44), and positive aspects of caregiving (28, 32, 41, 45, 46). However, little is known about the components of psychosocial interventions that may generate these positive experiences among caregivers and PLWD. Hence, this scoping review focuses on uncovering the fundamentals of enriching components in psychosocial interventions for dementia caregiving dyads rather than the reported outcomes of these interventions. For the purpose of this review, we define psychosocial interventions as “interpersonal interventions concerned with the provision of information, education, or emotional support together with individual psychological interventions addressing a specific health and social care outcome” (47).

By identifying which components may generate enrichment in psychosocial interventions for dementia caregiving dyads, this review aims to understand how to support relationships through enriching experiences for both caregiver and care recipient. Two overarching research questions guided this review:

• “What types of psychosocial interventions reported in the literature may enrich relationships between caregiving dyads in a dementia context?”

• “Which components of these psychosocial interventions may contribute to the enrichment of relationships between caregiving dyads?”

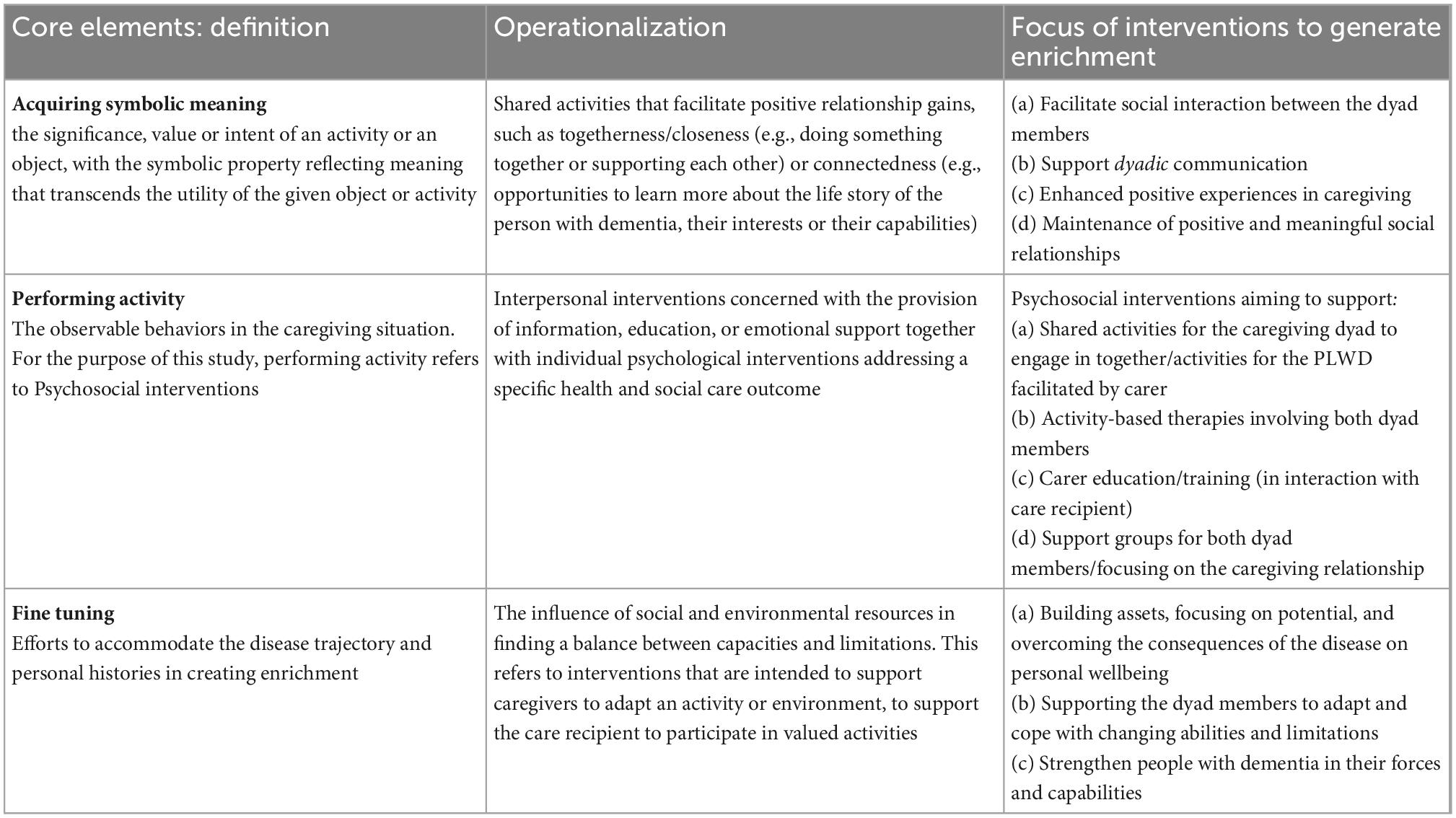

To answer our research questions, we built upon and extended the work of Cartwright and colleagues, who developed a model of enrichment in family caregiving for frail older adults (29). Using this model as a point of departure, we extended this definition to include both formal and informal relationships in dementia caregiving. This model was also used to guide the search strategy and data charting process; components of psychosocial interventions that may generate enrichment in dementia caregiving dyads were identified and mapped to the operationalized core enrichment elements (described in detail in the “Methods” section). The three core elements of enrichment have been operationalized following the definition proposed by Cartwright et al. (29), outlined in detail under “Concept” and summarized in Table 1. The process of operationalizing and contextualizing the core elements of enrichment was supported by findings from our preceding empirical studies focusing on dyadic relationships in dementia caregiving (48, 49), as well as the work of the INTERDEM Social Health Taskforce (30–34) (Supplementary Appendix 1). Within this context, this review mapped out existing types of psychosocial interventions and components that contribute to enrichment in dyadic relationships in formal and informal dementia caregiving contexts.

Table 1. Operationalization of enrichment in dementia and focus of psychosocial interventions contributing to enrichment.

Scoping reviews are valuable where evidence is widely dispersed or emerging and not yet amenable to questions of effectiveness (50). Furthermore, scoping review research questions may draw upon data from any type of evidence and research methodology (51). The purpose of this review is to scope and present an overview of psychosocial interventions promoting enrichment in dyadic relationships in dementia caregiving; therefore, a scoping review methodology (52) was deemed appropriate. This review was informed by the Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) approach to conducting and reporting scoping reviews (51) and utilized the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (53) to guide the development, conduct and reporting of this review (Supplementary Appendix 2).

The concept of enrichment in caregiving, especially in dementia, has not been systematically applied in psychosocial interventions aiming to generate positive experiences in caregiving and improve caregiving relationships. Therefore, the developed search strategy was informed by the three core elements of enrichment proposed by Cartwright et al. (29), operationalized and contextualized to caregiving relationships in dementia.

A prior review of relevant literature was conducted using PubMed (MEDLINE) to pilot the initial search terms, and relevant articles were reviewed to identify additional keywords for inclusion. The initial list of search terms was further refined in consultation with an expert research librarian to optimize the specificity and sensitivity of the search strategy. The search strategy was subsequently applied to five electronic databases in March 2022: MEDLINE via Ovid, CINAHL, AgeLine, Cochrane Library, and PsycINFO via Ovid. Key search terms included but were not limited to: “dementia”, “dyad”, “couple”, “family”, “carer”, “nurse”, “staff”, “social interaction” communication”, “social participation”, “intervention”, “psychosocial”, “reminiscence”, “relationship”, “meaningful”, “community”, “neighborhood”, “home dwelling”, “long-term care”, “assisted living facilities”. A complete strategy for MEDLINE is applied available in the (Supplementary Appendix 3).

During the study selection, all records were imported into Endnote and deduplicated before going through a two-phase screening process. Phase one included the screening of titles and abstracts using Rayyan, a web application for systematic reviews (54). The first and second authors (VH and WQK) independently screened titles and abstracts, discussed, and resolved discrepancies. Next, VH and WQK independently screened the full texts of included articles, discussed and resolved any conflicts in consultation with the third author (DS) consulted as necessary. The inclusion criteria are shown in the population, concept, and context (PCC) mnemonic in Table 2.

The study population included caregiving dyads, with caregivers being both formal and informal. The target groups of the psychosocial interventions are people living with dementia (regardless of type or severity of the disease), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), or memory problems as the primary diagnosis and their formal or informal caregiver in a dyadic relationship. Specifically, the reported interventions needed to target dyads as a unit, including care recipient and caregiver, or the relationship between the two.

The variety of terminologes encompassed in “enrichment” disposed the review to subjectivity. To ensure consistent inclusion of relevant studies, the three core elements in the concept of enrichment (29) were operationalized considering terms that broadly fall under the same definition. According to Cartwright and colleagues, the enrichment process represents the integration of three core elements: “acquired symbolic meaning”, “performing activity,” and “fine tuning” (29). The operationalization of these three elements (outlined in Table 1) guided the search strategy and inclusion criteria:

The first core element, acquired symbolic meaning, refers to the significance, value or intent of an activity or an object, with symbolic meaning extending beyond the utility of the given object or activity (29). Supported by empirical findings (49), this core element of enrichment is operationalized as shared activities that can lay the groundwork for positive relationship gains. A key element of psychosocial interventions is that they serve as a communication channel for PLWD to engage, interact and talk with others (31, 46). Thus, interventions intended to support social interaction and/or communication are also included here.

The second core element, performing activity, is described by Cartwright et al. as the observable behaviors in the caregiving situation (29). To extend the model to a dementia caregiving context, performing activity encompass psychosocial interventions, as defined above. Operationalized within a dementia caregiving context, this includes interpersonal relationships, wellbeing, cognition, and functioning in everyday activities (33). A central aspect of psychosocial interventions for PLWD involves supporting social participation (30, 31), as the quality of participation in social activities (experienced as meaningful to PLWD) can be considered indicative of social relationships and how a person with dementia stays connected with the social environment (31, 55). As such, social participation was also included in this core element.

The final core element, fine tuning, involves efforts to accommodate the “frailty” trajectories – as described by Cartwright and colleagues – and histories in creating enrichment (29). In a dementia caregiving context, this includes different activities and environmental modifications according to the capabilities and personal preferences of PLWD. This is in line with the INTERDEM Social Health Taskforce’s recommendations to focus on the remaining capabilities and strengths of PLWD rather than their deficits and cognitive deterioration (31). Hence, fine tuning was operationalized as “Interventions intended to support caregivers to adapt an activity or environment, to support care recipient’s participation in valued activities.”

All caregiving contexts were included, as the focus of this review was to assess interventions facilitating enrichment in dyadic relationships, regardless of context.

In addition to the outlined PCC, the following inclusion criteria were applied: (i) published, peer-reviewed papers; (ii) qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods primary research; (iii) reporting on an intervention targeted at caregiving dyads; (iv) published in English with an available full text. Correspondingly, articles that did not meet the outlined inclusion criteria were excluded. To ensure comprehensive coverage of the literature, reviews were included for citation tracking to identify further relevant studies. Figure 1 depicts a PRISMA flowchart displaying the decision process for study inclusion.

The research team developed a standardized charting form using Microsoft Excel for data charting, informed by JBIs guidance (51). A quality appraisal of the included studies was not conducted, as this is not necessitated for scoping reviews (51). The results were synthesized in three steps:

1. Identifying psychosocial interventions: A detailed description of the included psychosocial interventions was extracted, including authors, publication year, the country in which the study was conducted, stated aim, study design, intervention characteristics, caregiving setting, nature of the caregiving relationship (formal/informal) and implementation/delivery method from each study. All authors reviewed the charting sheet, and VH and WQK piloted the data charting using 20% of the identified studies to ensure consistency in data extraction. After that, VH charted the remaining 80% of the data independently, verified by WQK upon completion.

2. Identifying intervention components: VH deductively coded the extracted data by mapping the identified intervention components onto the three core elements. WQK verified this process. No percent agreement or kappa coefficient was calculated in this process, rather, all intervention components were rigorously assessed using the operationalized enrichment core elements and the standardized charting form. Any disagreements were discussed until consensus was achieved.

3. Identifying enrichment categories: The identified intervention components were grouped within each core element to identify categories of intervention components that may contribute to enrichment in dementia caregiving relationships. These categories were discussed among all authors.

The narrative below provides an overview of the main intervention types and the component categories within each operationalized enrichment core element (summarized in Table 4).

The database search resulted in 1,199 publications included for title and abstract screening, with an additional 65 articles from citation tracking of screened literature reviews. Following the full-text screening of 122 articles, 34 articles were included. The screening process is summarized in Figure 1.

Twelve countries were represented in the studies conducted, of which the majority were in Europe (n = 19, including Belgium, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, and the United Kingdom). Other studies were conducted in Australia (n = 4), Canada (n = 3), Hong Kong (n = 1), and the US (n = 7). Two articles included multi-national studies (56, 57). Three research approaches were employed, including 12 quantitative, 11 qualitative, and 11 multi- or mixed-methods. Fifteen studies described interventions for community-dwelling caregiving dyads, while seventeen described interventions conducted in institutional settings. The final two studies included both settings. The sample size in each study ranged from three (one PLWD and two caregivers) to 1,515 participants (550 PLWD and 965 caregivers). The nature of the caregiving relationships was not necessarily dependent on the caregiving setting. Of the interventions conducted in institutional settings, two focused exclusively on the dyadic relationship of residents with dementia and their visiting family members (58, 59), while six articles reported on psychosocial interventions, including both nursing staff and family caregivers in social interactions with PLWD (60–65). All studies conducted in a community-based setting were focused solely on informal dyadic relationships with family members being the primary caregivers (n = 17; i.e., no studies reported on non-relatives). Table 3 summarizes the studies’ characteristics and the psychosocial interventions delivered.

A wide array of interventions containing elements contributing to the operationalized definition of enrichment was identified. The interventions were categorized into three groups: (1) engagement in dyadic activities; (2) carer education or training; and (3) restructuring the caregiving framework around PLWD.

Most studies reported interventions (n = 22) which involved supporting caregiving dyads to participate in social activities (either supported by objects for shared attention or structured social sessions), cognitive and multisensory stimulation and self-management. Carer-provided stimuli for PLWD was a central means to support social participation, either through cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) (66, 67) or in dedicated rooms, the latter including multisensory stimulation to improve caregiving in institutional settings through meaningful social interactions in the caregiving dyads (57, 68). Bemelmans et al. (60) reported on an intervention involving the social pet robot, PARO, to elicit social engagement and facilitate interactions between dyads. Two interventions employed mobile applications to promote self-management and social participation in community-dwelling caregiving dyads (56, 69), while another intervention introduced a dementia assistance dog to support dyads at home (70).

Seven interventions included reminiscence therapy or reminiscence-based activities encompassed in a multi-component intervention (59, 61, 62, 71–74), either one-to-one (59, 61, 62, 72) or in groups (71, 73, 74). Two interventions utilized digital devices to promote reminiscence (62, 72), while four facilitated reminiscing using a collection of objects meaningful to the PLWD (59, 61) or through group conversations (71, 73, 74). Five of the remaining interventions implemented music, focusing mainly on social dancing (75), singing therapy (76), personalized music lists (77), or active music sessions combining singing, movement and playing instruments (58, 78). Two interventions involved engaging a professional artist to facilitate structured group sessions for community-dwelling dyads, involving group-based art-viewing, discussion and art-making (65, 79).

The second category encompassed ten interventions covering carer training either as a single-component intervention (64, 80–83) or using educational modules as one of the multicomponent interventions (63, 84–87). Interventions focusing solely on carer education and training included modules to promote integrity for PLWD (80), enhancing family visits to nursing homes (64), dyadic communication training (81, 83) and training to support PLWD’s functional abilities (82). Where education and training were part of multicomponent interventions, they focused on re-ablement (84, 85), empowerment (87), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) (86), and palliative care (63). The emphasis of these interventions was on promoting emotional health, physical strengths or cognitive capabilities in PLWD.

The final category contains only two interventions focused on the caregiving environment. In one study, the physical environment of the dining room in a nursing home was renovated to create a sense of homeliness for PLWD (88). In another study, the social aspect of care provision was changed to support care staff to take more ownership in developing and implementing care plans for their residents (89).

Many interventions contained components contributing to several core elements of enrichment in multiple ways, resulting in some overlap of subcategories. Table 4 summarizes the articles’ identified intervention components contributing to enrichment. The synthesized results are organized and presented categorically according to each core element of enrichment. Within each core element, categories of intervention components were identified; The treemap below displayed these categories and their relative sizes within each core element (Figure 2).

When analyzing the interventions included in this review, elements contributing to this enrichment core element were categorized into four categories: (i) core focus on the dyadic relationship; (ii) supporting communication; (iii) common platform for activity engagement; and (iv) socially oriented caregiving. Core focus on the dyadic relationship: Nine studies described interventions with a core focus on supporting dyadic relationships. These interventions were targeted at improving or maintaining the dyadic relationship (76, 81, 83), facilitating positive experiences (58, 60, 68), promoting connectedness in the dyad (56, 63) or enhancing the quality of social interactions (64). Supporting communication: The largest category (as depicted in Figure 2) of interventions’ contribution to “acquired symbolic meaning” was communication support, either using tools to help caregivers identify topics of conversation (56, 61, 68, 72), facilitating structured discussions (58, 66, 67, 79, 81) or providing training in verbal and/or non-verbal communication techniques (66, 81, 83, 85). Common platform for activity engagement: Several interventions provided a common platform for social interaction between dyad members. By providing a point of joint attention between the dyad members (59, 60, 72, 79), the interventions created a framework within which they could engage in meaningful activities together (56, 57, 69, 76). Regardless of whether the interventions aimed to stimulate positive social interactions (59–61, 66) or empowerment (56, 87), the fact that the focus was on the social aspects themselves and not on regular caregiving duties (63, 68, 75) provided structure to the social interactions. Socially oriented caregiving: Some interventions (n = 6) described a shift from “passive” caregiving responsibilities to a more socially oriented approach (82) of enabling meaningful relationships to form between care staff and PLWD (63, 68), encouraging openness in the dyadic relationship (84) and engaging PLWD in social interactions in the caregiving routine (75, 82).

Thirty-one interventions contained elements that contributed to enrichment within the core element of “performing activity”, and could be divided into four categories: (i) dementia-friendly activities; (ii) enhancing dementia caregiving; (iii) formal carer education and training; and (iv) informal carer education and training. Dementia-friendly activities: Most interventions engaged both dyad members in dementia-friendly activities, and as Figure 2 shows, this category was the most-represented category of all intervention components across all three core elements. These intervention components involved individualized social and physical stimulation for PLWD (57, 59, 61, 62, 66, 67, 72, 77) to engage both dyad members in social interactions. Enhancing dementia caregiving: Interventions which, in one way or another, could facilitate caregiving activities (60, 63, 70, 76, 86). This included emphasis on having the same person providing one-to-one care for PLWD (63), supporting daily (care) activities using a live or robotic pet (60, 70) and activity-based therapies involving both dyad members (76, 86). Formal carer education and training: Despite being the smallest category according to the treemap (Figure 2), several approaches were used to educate and train staff in institutional settings. These included education on providing optimized care through improved interactions (63, 80, 82), awareness of the physical, emotional, and social needs of PLWD (68), engaging PLWD in social activities using supportive tools (64, 68) or person-centered care approaches (82). Informal carer education and training: In contrast to approaches for staff, the education for informal caregivers was focused on supporting them to adapt and adjust to the dementia diagnosis. These included education on coping strategies (81, 84), communication and listening (64, 66, 71, 81, 83), conflict solution (83), and socially engaging their loved ones with dementia through supportive tools (61) or skill acquisition (64, 66, 74, 85, 86).

Although the intervention components were not as strongly represented within “fine tuning” as the two other core elements, three categories were identified: (i) developing and/or specifying goals; (ii) emotional support; and (iii) adapting the environment. Developing and/or specifying goals: Several intervention components included supporting one or both dyad members to formulate individualized goals and strategies in formal and informal caregiving relationships, to support their adaption and coping with symptoms of dementia and changing needs and capabilities (60, 81, 84–87). These included helping dyad members identify their individual and collective strengths (81, 87), areas of concern or difficulties (85, 86) and monitoring goal attainment (84, 87). Some involved specialist assessments of functional abilities and activity analysis (81, 84) or programs developed by specialists such as clinical psychologists (86) or occupational therapists (85). For community-dwelling dyads, intervention components also involved equipping them with skills to manage stress, anxiety and pain (84, 85), problem-solving and task simplification (85, 86). Maintaining or optimizing independence was an underlying theme in many of the goals specified through self-care (84), problem-solving strategies (81, 84, 85) and acquiring new skills in adapting to functional loss (87). Independence for PLWD or community-dwelling dyads was also sought through digital self-management tools (56, 69) or care approaches (82, 87). Emotional support: Several interventions emphasized providing emotional support to help carers become more familiar with common symptoms and behavior in dementia (64, 86), providing opportunities for reflection and active participation (56, 83, 84, 89), using the relationship as a resource for coping (81, 86, 87), and to address challenges in the dyadic relationship (86, 89). This support was mainly directed at informal caregivers (56, 64, 81, 83, 84, 86, 87), but one intervention included emotional support for staff in a nursing home (89). Adapting the environment: Some interventions described environment adaptation to support the relationships between PLWD and their caregivers, such as the physical revamping of the dining space in an LTC setting to create a more responsive environment (88), or adapting the homes of community-dwelling caregiving dyads (81, 84, 85), Creating “failure-free” social environments to support engagement in group activities (73) or using virtual tools supporting social interaction were important strategies to accommodate PLWD (62, 69). Finally, activity grading and task simplification were also present when adapting the environment to tailor to the cognitive, communicative and physical abilities of PLWD (59, 66), focusing on potential and capabilities rather than performance (68, 76), as well as energy conservation (84).

The objective of this review was to scope the body of literature on what constitutes enrichment in dementia caregiving by mapping components of psychosocial interventions onto our operationalized core elements of enrichment. To the best of our knowledge, this scoping review is the first to systematically identify and synthesize existing evidence on psychosocial interventions that facilitate enrichment in dyadic caregiving relationships in dementia. Most included studies were community-based or conducted in LTC facilities and mainly provided shared activities for the dyads, carer education interventions and structural change to the environment around PLWD.

Overall, our findings indicate an important distinction between formal and informal caregiving relationships: In formal caregiving relationships (i.e., between PLWD and paid caregivers), interventions were mainly directed at changing the care provision, shifting focus from pure custodial care to caregiving with space for the social element in the dyadic interactions. Whether the intervention type involved carer education/training (80, 82), restructuring the physical or organizational environment (88, 89) or engaging dyad members in shared activities (57, 68, 73, 75, 77, 78), the interventions created dedicated space for building a relationship between caregiver and care recipient, where such space otherwise is limited. In contrast, interventions targeting informal caregiving relationships appeared to support relationship sustenance by mitigating some challenges that might follow a dementia diagnosis. These interventions contained components emotionally supporting the dyad members to adjust and cope with the diagnosis (64, 71, 81, 83, 86), facilitating positive social interactions (58, 59, 61, 66, 67, 72, 74, 76, 79) or empowering them through self-management (56, 69, 70, 85, 87). These findings highlight the importance of supporting formal caregivers to enrich caregiving relationships. As such, future interventions may consider dedicating resources, such as protected time (90, 91), to support positive social interactions. Similarly, enrichment in informal relationships, where informal caregivers constantly have to adapt to the changing relationship dynamics alongside the progression of dementia, may be generated through interventions that facilitate positive social interactions or support dyads to build on collective and individual strengths.

Within the first core element, “acquired symbolic meaning”, intervention components contributing to enrichment had one important thing in common, regardless of the type of relationship: They all, in some way or another, facilitated dyadic communication, either explicitly (i.e., the category supporting communication), or indirectly through communication-enhancing mechanisms (i.e., the category showing a core focus on dyadic relationships; common platform for activity engagement; or socially oriented caregiving). Additionally, as shown in Figure 2, communication support was the most-represented category within “acquired symbolic meaning”. Considering the communication challenges that follow a dementia diagnosis, communication support seems essential to enrichment in dementia caregiving dyads. Eggenberger and colleagues’ systematic review found that communication skills in dementia care improve the life and wellbeing of PLWD cared for both in the community and institutional settings (92). They also found that formal caregivers reported a greater feeling of control and joy from opportunities to learn more about the patients in their care (92). However, the practicalities of supporting PLWD through communication are rarely mentioned in research (93), and socially oriented care through such day-to-day communication should receive greater attention.

Intervention components falling under the core element of “performing activity” were mostly contained within dementia-friendly activities (such as individualized social and physical stimulation for PLWD) or carer training and education. While dementia-friendly activities are gaining momentum in dementia research on social health (30, 94–96), this review showed that relatively few studies explicitly focused on supporting caregiving dyads’ relationship. Considering the reciprocal influence dyad members have on each other (97, 98), interventions focusing on dyads seem more effective than interventions focusing separately on each individual (17, 98). As such, to generate enrichment in caregiving relationships, developers of psychosocial interventions may consider including both dyadic members on equal terms to enhance dyadic wellbeing (17). A common intervention in dementia care often includes caregiver training and education that is often focused on one dyadic member (e.g., on the caregiver). Such training and education programs may increase effectiveness by including an additional focus on the relational aspect of the caregiving dyad.

Intervention components contributing to the final core element of enrichment, “fine tuning”, primarily targeted informal caregiving relationships through interventions supporting community-dwelling caregiving dyads to adapt and cope with dementia through educational modules and emotional support. These categories of fine tuning deserve greater attention in dementia research since relationship quality is recognized as a significant factor influencing the health and wellbeing of both caregiver and care recipient, consequently impacting their ability to live together at home (76). Although entirely different conditions govern formal caregiving, one could argue that the importance of “fine tuning” is no lower once a person with dementia transfers to institutional care. However, few included studies reported on interventions delivered in institutional settings adapting an activity or environment to support PLWD’s participation in valued activities. Some examples were identified, such as creating a more responsive dining environment for dyadic interaction (88), story-telling groups (73), or educating staff to adapt and optimize interactions in caregiving (68, 82, 89). With research indicating that nursing home residents with dementia are involved in few social activities (99–102), there is a need for more interventions to support “fine tuning” in formal caregiving to facilitate shared social activities that might enrich the caregiving dyad. Moreover, as indicated by the third category of psychosocial interventions containing only two studies, more interventions are needed focusing on accommodating the physical environment to create room for enrichment.

Whether the interventions contained components that fell under one, two, or all three core enrichment elements, there was a vast array of different approaches that may enrich the dyadic relationship and thereby enhance the relationship quality through different mechanisms. Therefore, interventions aiming to enrich dyadic relationships are inherently related to relationship-centered care strategies, as such interventions may lead to relationship gains (29, 41). With research suggesting that enriching activities can provide a vehicle to maintain or strengthen dyadic relationships and enhance positive outcomes for both caregiver and care recipient (103), intervention components identified in this scoping review may further contribute to developing research-centered approaches. In dementia research, influential theories have traditionally leaned toward stress-coping models that focus on burden and strain (9, 104, 105). There is an ongoing shift toward a more positive dementia discourse, with increasing attention to the social health of PLWD and their caregivers (30, 31, 106, 107). Nevertheless, there is a need to conceptualize this focus (28, 108). Although not previously applied to dementia research, the model of Cartwright and colleagues offers a broad inclusion of different typologies of dyadic relationships while focusing on positive aspects of caregiving. The application of theoretical frameworks appropriate for dyadic processes has been emphasized as essential to expand our understanding of outcomes in dementia research (17), as they might lead to innovative approaches in working with caregiving dyads (108). As such, we believe that the model of Cartwright and colleagues may provide a useful framework when developing, implementing and evaluating psychosocial interventions taking on a relationship-centered approach.

This study reviewed and clarified intervention components that may contribute to enrichment, which might provide a groundwork for future research aiming to promote positive caregiving experiences through enrichment by supporting relationship sustenance among dyads. Enrichment in interventions targeting formal caregiving relationships seems to require space dedicated to enabling social interactions beyond custodial care. Considerations such as protected time and explicit training on socially oriented care may be necessary (109–111) to allow positive relationships to emerge and grow. Interventions targeting informal dyads, on the other hand, may consider building on the dyads’ shared history and sustain or enhance their caregiving relationship by including components that may circumvent the challenges that follow when living with dementia, such as emotional support, coping and management strategy training or dementia-friendly shared activities.

Regardless of the relationship type, communication seems essential to contributing to enrichment in dyadic relationships interactions, calling for increased focus on communication skill acquisition and support in dementia research and practice. Naturally, the type of caregiving relationship constitutes a major contextual factor influencing the “process of endowing caregiving with meaning or pleasure” for both dyad members. Although the interventions shared many similarities in how their components contributed to enrichment, the nature of the caregiving relationship will unquestionably influence how the three core enrichment elements can be achieved. The same is true for the outcomes of enrichment in terms of impacting the dyad members and their relationships. Research suggests that the relational nature influences the relationship quality and the experiences of both dyad members living with dementia (15). Cartwright and colleagues included contextual factors and enrichment outcomes in their theoretical model (29). Future research into enrichment in dementia caregiving can therefore utilize this model and further extend it when focusing on outcomes of enrichment, as well as contextual influences.

There are several strengths of this review. First, an established methodological framework was used to guide the conduct of the review. Next, there is no existing definition of enrichment in dyadic relationships; to minimize the potential subjectivities, this scoping review leveraged and built upon the model by Cartwright et al., using empirical research and the spearheaded work of the INTERDEM Social Health Taskforce (30–34). This enabled the concept of enrichment to be operationalized and systematically applied during the construction of the search strings, data screening, charting and synthesis. Next, the initial search strategy was refined and further developed in collaboration with an expert research librarian with extensive knowledge and experience in literature reviews. Finally, at least two independent reviewers were involved in the screening, charting, and data synthesis stages. A third reviewer was involved in resolving any disagreements.

There are also limitations to this review that must be acknowledged. Since enrichment has not been defined previously, there is a chance that relevant studies are not yielded from the current search strategy. Despite the operationalization of the concept of enrichment guiding the inclusion criteria, articles using different terms than those contained in our search strategy may not be identified. A systematic citation tracking of identified reviews was also conducted to minimize this risk. Nevertheless, other relevant studies might have been missed as only peer-reviewed publications in English were included. A final limitation that must be considered is that this review did not look into the outcomes of the psychosocial interventions. The realized individual or relational gains (or the lack thereof) following psychosocial interventions containing enriching components fall outside the scope of this review and are not synthesized. However, with no existing framework to follow in systematically promoting enrichment in the context of dementia, we consider this review as the first step in the development of an extensive groundwork focusing on the positive aspects of dementia caregiving.

This scoping review proposed taking on a relationship-centered approach using and extending a theoretical framework for enrichment to develop and promote psychosocial interventions supporting dyadic relationships in dementia caregiving. By charting the evidence of existing psychosocial interventions that may enrich relationships between caregiving dyads, we identified intervention components that may contribute to such enrichment. Interventions aiming to enhance formal caregiving relationships should focus on providing space for positive social interactions and room for relationships to build and grow. Interventions targeting informal caregiving dyads, on the other hand, need to consider the existing relationship when facilitating positive social interactions and provide support in coping and managing the changing relationship dynamics a dementia diagnosis might bring. Whether the caregiving relationship is formal or informal, dyadic communication support and skill acquisition seem vital in laying the groundwork for generating enrichment in the caregiving relationship. Findings from this review may inform the planning and development of enrichment interventions to improve or maintain dyadic relationships in dementia caregiving, which may ultimately lead to beneficial outcomes.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The review was conceived and planned by VH in conjunction with WQK and DS. An initial literature search strategy was developed and conducted by VH based on theoretical and empirical literature, which was thereafter revised and refined in collaboration with an expert research librarian. VH and WQK thereafter screened titles/abstracts and full-text articles for eligibility independently. Discrepancies between VH and WQK was discussed until consensus was achieved, and any discrepancies in the full-text screening phase was resolved by DS. VH and WQK independently piloted 20% of the data extraction before VH completed the remaining 80%, verified by WQK. The charting and analysis of extracted data was conducted by VH, again verified by WQK and discussed with DS. VH wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was critically reviewed by WQK and DS, and the drafts were thereafter developed in an iterative process through joint discussions between all three authors. All authors agreed on the final manuscript submitted for publication.

This study arises from the project DISTINCT (Dementia: Intersectorial Strategy for Training and Innovation Network for Current Technology), which is funded by the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Innovative Training Networks (MSC-ITN) under the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 program (Grant Agreement No. 813196).

The authors would like to acknowledge the incredible contribution and reflected advice of Rosie Dunne and Michael Fanning in the development of our literature search strategy.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2022.1069846/full#supplementary-material

1. Kitwood T, Bredin K. Towards a theory of dementia care: personhood and well-being. Ageing Soc. (1992) 12:269–87. doi: 10.1017/s0144686x0000502x

2. Kitwood T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First. Maidenhead: Open University Press (1997).

3. Post S. Quality of Life and Quality of Lives in Dementia Care. Maidenhead: Oxford University Press (2001).

4. Nolan M, Ryan T, Enderby P, Reid D. Towards a more inclusive vision of dementia care practice and research. Dementia. (2002) 1:193–211.

5. Nolan M, Brown J, Davies S, Nolan J, Keady J. The Senses Framework: Improving Care for Older People through a Relationship-Centred Approach. Getting Research into Practice (Grip) Report No 2. Sheffield: University of Sheffield (2006).

6. Adams T, Gardiner P. Communication and interaction within dementia care triads: developing a theory for relationship-centred care. Dementia. (2005) 4:185–205. doi: 10.1177/1471301205051092

7. Lyons K, Zarit S, Sayer A, Whitlatch C. Caregiving as a dyadic process: perspectives from caregiver and receiver. J Gerontol Ser B. (2002) 57:195–204. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.P195

9. Hellström I, Nolan M, Lundh U. Sustaining couplehood’. Spouses’ strategies for living positively with dementia. Dementia. (2007) 6:383–409. doi: 10.1177/1471301207081571

10. Snyder J. Impact of caregiver-receiver relationship quality on burden and satisfaction. J Women Aging. (2000) 12:147–67. doi: 10.1300/J074v12n01_10

11. Lawrence R, Tennstedt S, Assmann S. Quality of the caregiver–care recipient relationship: does it offset negative consequences of caregiving for family caregivers? Psychol Aging. (1998) 13:150. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.13.1.150

12. Brown Wilson C, Swarbrick C, Pilling M, Keady J. The senses in practice: enhancing the quality of care for residents with dementia in care homes. J Adv Nurs. (2013) 69:77–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05992.x

13. Beach M, Inui T, Relationship-Centered Care Research Network. Relationship-centered care. A constructive reframing. J Gen Intern Med. (2006) 21(Suppl. 1):S3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00302.x

14. Shim B, Barroso J, Davis L. A comparative qualitative analysis of stories of spousal caregivers of people with dementia: negative, ambivalent, and positive experiences. Int J Nurs Stud. (2012) 49:220–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.09.003

15. Ablitt A, Jones G, Muers J. Living with dementia: a systematic review of the influence of relationship factors. Aging Ment Health. (2009) 13:497–511. doi: 10.1080/13607860902774436

16. Bielsten T, Hellström IA. Review of couple-centred interventions in dementia: exploring the what and why – part A. Dementia. (2019) 18:2436–49. doi: 10.1177/1471301217737652

17. Braun M, Scholz U, Bailey B, Perren S, Hornung R, Martin M. Dementia caregiving in spousal relationships: a dyadic perspective. Aging Ment Health. (2009) 13:426–36. doi: 10.1080/13607860902879441

18. Kindell J, Keady J, Sage K, Wilkinson R. Everyday conversation in dementia: a review of the literature to inform research and practice. Int J Lang Commun Disord. (2017) 52:392–406. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12298

19. Beard R, Knauss J, Moyer D. Managing disability and enjoying life: how we reframe dementia through personal narratives. J Aging Stud. (2009) 23:227–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2008.01.002

20. McGilton K, Boscart V, Brown M, Bowers B. Making tradeoffs between the reasons to leave and reasons to stay employed in long-term care homes: perspectives of licensed nursing staff. Int J Nurs Stud. (2014) 51:917–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.10.015

21. McGilton K, O’Brien-Pallas L, Darlington G, Evans M, Wynn F, Pringle D. Effects of a relationship-enhancing program of care on outcomes. J Nurs Scholarsh. (2003) 35:151–6.

22. Prentice D, Black M. Coming and staying: a qualitative exploration of registered nurses’ experiences working in nursing homes. Int J Older People Nurs. (2007) 2:198–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2007.00072.x

23. Killick J, Allan K. Communication and the Care of People with Dementia. Philadeplphia, PA: Open University Press (2001). p. 388.

24. Buron B. Levels of personhood: a model for dementia care. Geriatr Nurs. (2008) 29:324–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.11.001

25. Molyneaux V, Butchard S, Simpson J, Murray C. The co-construction of couplehood in dementia. Dementia. (2011) 11:483–502. doi: 10.1177/1471301211421070

26. Smebye K, Kirkevold M. The influence of relationships on personhood in dementia care: a qualitative, hermeneutic study. BMC Nurs. (2013) 12:29. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-12-29

27. Kindell J, Wilkinson R, Sage K, Keady J. Combining music and life story to enhance participation in family interaction in semantic dementia: a longitudinal study of one family’s experience. Arts Health. (2018) 10:165–80. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2017.1342269

28. Carbonneau H, Caron C, Desrosiers J. Development of a conceptual framework of positive aspects of caregiving in dementia. Dementia. (2010) 9:327–53. doi: 10.1177/1471301210375316

29. Cartwright J, Archbold P, Stewart B, Limandri B. Enrichment processes in family caregiving to frail elders. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. (1994) 17:31–43. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199409000-00006

30. de Vugt M, Dröes R. Social health in dementia. towards a positive dementia discourse. Aging Ment Health. (2017) 21:1–3. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1262822

31. Dröes R, Chattat R, Diaz A, Gove D, Graff M, Murphy K, et al. Social health and dementia: a European consensus on the operationalization of the concept and directions for research and practice. Aging Ment Health. (2017) 21:4–17. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1254596

32. de Vugt M, Verhey F. The impact of early dementia diagnosis and intervention on informal caregivers. Prog Neurobiol. (2013) 110:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.04.005

33. Moniz-Cook E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Woods B, Orrell M, Network I. Psychosocial Interventions in Dementia Care Research: The Interdem Manifesto. Abingdon-on-Thames: Taylor & Francis (2011).

34. Vernooij-Dassen M, Moniz-Cook E, Verhey F, Chattat R, Woods B, Meiland F, et al. Bridging the divide between biomedical and psychosocial approaches in dementia research: the 2019 interdem manifesto. Aging Ment Health. (2019) 25:2. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1693968

35. McDermott O, Crellin N, Ridder H, Orrell M. Music therapy in dementia: a narrative synthesis systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2012) 28:781–94.

36. Subramaniam P, Woods B. The impact of individual reminiscence therapy for people with dementia: systematic review. Expert Rev Neurother. (2012) 12:545–55. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.35

37. Testad I, Mekki T, Førland O, Øye C, Tveit E, Jacobsen F, et al. Modeling and evaluating evidence-based continuing education program in nursing home dementia care (Medced)—training of care home staff to reduce use of restraint in care home residents with dementia. a cluster randomized controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2016) 31:24–32. doi: 10.1002/gps.4285

38. Ayres L. Narratives of family caregiving: the process of making meaning. Res Nurs Health. (2000) 23:424–34.

39. Sörensen S, Duberstein P, Gill D, Pinquart M. Dementia care: mental health effects, intervention strategies, and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol. (2006) 5:961–73.

40. Baikie E. The impact of dementia on marital relationships. Sex Relat Ther. (2002) 17:289–99. doi: 10.1080/14681990220149095

41. Lloyd J, Patterson T, Muers J. The positive aspects of caregiving in dementia: a critical review of the qualitative literature. Dementia. (2016) 15:1534–61.

42. Moyle W, Arnautovska U, Ownsworth T, Jones C. Potential of telepresence robots to enhance social connectedness in older adults with dementia: an integrative review of feasibility. Int Psychogeriatr. (2017) 29:1951–64. doi: 10.1017/S1041610217001776

43. Baker F, Grocke D, Pachana N. Connecting through music: a study of a spousal caregiver-directed music intervention designed to prolong fulfilling relationships in couples where one person has dementia. Austr J Music Ther. (2012) 23:4–21.

44. Van Haitsma K, Curyto K, Abbott K, Towsley G, Spector A, Kleban MA. Randomized controlled trial for an individualized positive psychosocial intervention for the affective and behavioral symptoms of dementia in nursing home residents. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. (2015) 70:35–45. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbt102

45. Quinn C, Clare L, McGuinness T, Woods R. The impact of relationships, motivations, and meanings on dementia caregiving outcomes. Int Psychogeriatr. (2012) 24:1816–26.

46. Orrell M, Yates L, Leung P, Kang S, Hoare Z, Whitaker C, et al. The impact of individual cognitive stimulation therapy (iCST) on cognition, quality of life, caregiver health, and family relationships in dementia: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med. (2017) 14:e1002269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002269

47. Pusey H, Richards DA. Systematic review of the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for carers of people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. (2001) 5:107–19. doi: 10.1080/13607860120038302

48. Hoel V, Wolf-Ostermann K, Ambugo E. Social isolation and the use of technology in caregiving dyads living with dementia during Covid-19 restrictions. Front Public Health. (2022) 10:697496. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.697496

49. Hoel V, Ambugo E, Wolf-Ostermann K. Sustaining our relationship: dyadic interactions supported by technology for people with dementia and their informal caregivers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:10956. doi: 10.3390/ijerph191710956

50. Peters M, Marnie C, Colquhoun H, Garritty C, Hempel S, Horsley T, et al. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst Rev. (2021) 10:263. doi: 10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

51. Peters M, Godfrey C, Khalil H, McInerney P, Soares C, Parker D. 2017 guidance for the conduct of Jbi scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna briggs institute reviewer’s manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute (2017).

52. Munn Z, Peters M, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2018) 18:143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

53. Tricco A, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien K, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. Prisma extension for scoping reviews (prisma-scr): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. (2018) 169:467–73.

54. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. (2016) 5:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

55. Kuiper J, Zuidersma M, Zuidema S, Burgerhof J, Stolk R, Oude Voshaar R, et al. Social relationships and cognitive decline: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Int J Epidemiol. (2016) 45:dyw089. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw089

56. Lasrado R, Bielsten T, Hann M, Schumm J, Reilly S, Davies L, et al. Developing a management guide (the Dempower app) for couples where one partner has dementia: nonrandomized feasibility study. JMIR Aging. (2021) 4:e16824.

57. Goodall G, Taraldsen K, Granbo R, Serrano J. Towards personalized dementia care through meaningful activities supported by technology: a multisite qualitative study with care professionals. BMC Geriatr. (2021) 21:468. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02408-2

58. Clair A, Ebberts A. The effects of music therapy on interactions between family caregivers and their care receivers with late stage dementia. J Music Ther. (1997) 34:148–64.

59. Crispi E, Heitner G. An activity-based intervention for caregivers and residents with dementia in nursing homes. Act Adapt Aging. (2002) 26:61–72. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-11-30

60. Bemelmans R, Gelderblom G, Jonker P, de Witte L. How to use robot interventions in intramural psychogeriatric care; a feasibility study. Appl Nurs Res. (2016) 30:154–7. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.07.003

61. Hagens C, Beaman A, Ryan E. Reminiscing, poetry writing, and remembering boxes: personhood-centered communication with cognitively impaired older adults. Act Adapt Aging. (2003) 27:97–112.

62. Hamel A, Sims T, Klassen D, Havey T, Gaugler J. Memory matters: a mixed-methods feasibility study of a mobile aid to stimulate reminiscence in individuals with memory loss. J Gerontol Nurs. (2016) 42:1–10. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20160201-04

63. Froggatt K, Best A, Bunn F, Burnside G, Coast J, Dunleavy L, et al. A group intervention to improve quality of life for people with advanced dementia living in care homes: the namaste feasibility cluster rct. Health Technol Assess. (2020) 24:1–140. doi: 10.3310/hta24060

64. McCallion P, Tosel R, Freeman K. An evaluation of a family visit education program. J Am Geriatr Soc. (1999) 47:203–14.

65. Windle G, Caulfield M, Woods B, Joling K. How can the arts influence the attitudes of dementia caregivers? A mixed-methods longitudinal investigation. Gerontologist. (2020) 60:1103–14. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa005

66. Leroi I, Vatter S, Carter L, Smith S, Orgeta V, Poliakoff E, et al. Parkinson’s-adapted cognitive stimulation therapy: a pilot randomized controlled clinical trial. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. (2019) 12:1756286419852217.

67. Orgeta V, Leung P, Yates L, Kang S, Hoare Z, Henderson C, et al. Individual cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia: a clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. (2015) 19:1–108. doi: 10.3310/hta19640

68. van Weert J, van Dulmen A, Spreeuwenberg P, Ribbe M, Bensing J. Effects of snoezelen, integrated in 24 H dementia care, on nurse-patient communication during morning care. Patient Educ Couns. (2005) 58:312-26. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.07.013

69. Beentjes K, Neal D, Kerkhof Y, Broeder C, Moeridjan Z, Ettema T, et al. Impact of the findmyapps program on people with mild cognitive impairment or dementia and their caregivers; an exploratory pilot randomised controlled trial. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. (2020) 1–13. doi: 10.1080/17483107.2020.1842918 [Online ahead of print].

70. Ritchie L, Quinn S, Tolson D, Jenkins N, Sharp B. Exposing the mechanisms underlying successful animal-assisted interventions for people with dementia: a realistic evaluation of the dementia dog project. Dementia. (2021) 20:66–83. doi: 10.1177/1471301219864505

71. Charlesworth G, Burnell K, Crellin N, Hoare Z, Hoe J, Knapp M, et al. Peer support and reminiscence therapy for people with dementia and their family carers: a factorial pragmatic randomised trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. (2016) 87:1218–28. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-313736

72. Damianakis T, Crete-Nishihata M, Smith K, Baecker R, Marziali E. The psychosocial impacts of multimedia biographies on persons with cognitive impairments. Gerontologist. (2009) 50:23–35. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp104

73. Fritsch T, Jung K, Grant S, Lang J, Montgomery R, Basting A. Impact of timeslips, a creative expression intervention program, on nursing home residents with dementia and their caregivers. Gerontologist. (2009) 49:117–27. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp008

74. Woods R, Bruce E, Edwards R, Elvish R, Hoare Z, Hounsome B, et al. Remcare: reminiscence groups for people with dementia and their family caregivers – effectiveness and cost-effectiveness pragmatic multicentre randomised trial. Health Technol Assess. (2012) 16:v–xv, 1–116. doi: 10.3310/hta16480

75. Palo-Bengtsson L, Sirkka-Liisa Ekman R. Social dancing in the care of persons with dementia in a nursing home setting: a phenomenological study. Res Theory Nurs Pract. (1997) 11:101.

76. Tamplin J, Clark I, Lee Y, Baker F. Remini-sing: a feasibility study of therapeutic group singing to support relationship quality and wellbeing for community-dwelling people living with dementia and their family caregivers. Front Med. (2018) 5:245. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00245

77. Kuot A, Barton E, Tiri G, McKinlay T, Greenhill J, Isaac V. Personalised music for residents with dementia in an australian rural aged-care setting. Aust J Rural Health. (2021) 29:71–7. doi: 10.1111/ajr.12691

78. Götell E, Brown S, Ekman S. Caregiver-assisted music events in psychogeriatric care. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. (2000) 7:119–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2850.2000.00271.x

79. Camic P, Tischler V, Pearman C. Viewing and making art together: a multi-session art-gallery-based intervention for people with dementia and their carers. Aging Ment Health. (2014) 18:161–8. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.818101

80. Kihlgren M, Hallgren A, Norberg A, Karlsson I. Disclosure of basic strengths and basic weaknesses in demented patients during morning care, before and after staff training: analysis of video-recordings by means of the Erikson theory of “eight stages of man”. Int J Aging Hum Dev. (1996) 43:219–33. doi: 10.2190/Y3YL-R51V-MCPC-MW37

81. Nordheim J, Häusler A, Yasar S, Suhr R, Kuhlmey A, Rapp M, et al. Psychosocial intervention in couples coping with dementia led by a psychotherapist and a social worker: the Dyadem trial. J Alzheimers Dis. (2019) 68:745–55. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180812

82. Resnick B, Boltz M, Galik E, Fix S, Holmes S, Zhu S, et al. Testing the impact of Ffc-Al-eit on psychosocial and behavioral outcomes in assisted living. J Am Geriatr Soc. (2021) 69:459–66. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16886

83. Williams C, Newman D, Hammar L. Preliminary study of a communication intervention for family caregivers and spouses with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2018) 33:e343–9.

84. Jeon Y, Clemson L, Naismith S, Mowszowski L, McDonagh N, Mackenzie M, et al. Improving the social health of community-dwelling older people living with dementia through a reablement program. Int Psychogeriatr. (2018) 30:915–20.

85. Rahja M, Culph J, Clemson L, Day S, Laver KA. Second chance: experiences and outcomes of people with dementia and their families participating in a dementia reablement program. Brain Impair. (2020) 21:274–85.

86. Spector A, Charlesworth G, Marston L, Rehill A, Orrell M. Cognitive behavioural therapy (Cbt) for anxiety in dementia: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Alzheimers Dement. (2014) 10:209-10.

87. Yu D, Li P, Zhang F, Cheng S, Ng T, Judge K. The effects of a dyadic strength-based empowerment program on the health outcomes of people with mild cognitive impairment and their family caregivers: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Interv Aging. (2019) 14:1705-17. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S213006

88. Chaudhury H, Lillian H, Rust T, Wu S. Do physical environmental changes make a difference? Supporting person-centered care at mealtimes in nursing homes. Dementia. (2017) 16:878–96. doi: 10.1177/1471301215622839

90. Thoft D, Møller A, Møller A. Evaluating a digital life story app in a nursing home context – a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. (2021) 31:1884–95. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15714

91. Appel L, Appel E, Kisonas E, Pasat Z, Mozeson K, Vemulakonda J, et al. Virtual reality for veteran relaxation (Vr2) – introducing Vr-therapy for veterans with dementia – challenges and rewards of the therapists behind the scenes. Front Virt Real. (2021) 2:720523. doi: 10.3389/frvir.2021.720523

92. Eggenberger E, Heimerl K, Bennett M. Communication skills training in dementia care: a systematic review of effectiveness, training content, and didactic methods in different care settings. Int Psychogeriatr. (2013) 25:345–58. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212001664

93. Stanyon M, Griffiths A, Thomas S, Gordon A. The facilitators of communication with people with dementia in a care setting: an interview study with healthcare workers. Age Ageing. (2016) 45:164–70. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv161

94. DEEP. Involving People with Dementia in Creating Dementia Friendly Communities. (2015). Available online at: http://www.innovationsindementia.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/DEEP-Guide-Involving-people-with-dementia-in-Dementia-Friendly-Communities-3.pdf (accessed Jyly 08, 2022).

95. Øksnebjerg L, Diaz-Ponce A, Gove D, Moniz-Cook E, Mountain G, Chattat R, et al. Towards capturing meaningful outcomes for people with dementia in psychosocial intervention research: a pan-european consultation. Health Expect. (2018) 21:1056–65. doi: 10.1111/hex.12799

96. World Health Organization. Global Status Report on the Public Health Response to Dementia. Geneva: World Health Organization (2021).

97. Wiegelmann H, Wolf-Ostermann K, Brannath W, Arzideh F, Dreyer J, Thyrian J, et al. Sociodemographic aspects and health care-related outcomes: a latent class analysis of informal dementia care dyads. BMC Health Serv Res. (2021) 21:727. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06708-6

98. Van’t Leven N, Prick A, Groenewoud J, Roelofs P, de Lange J, Pot A. Dyadic interventions for community-dwelling people with dementia and their family caregivers: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. (2013) 25:1581–603.

99. Tak S, Beck C, Hong S. Feasibility of providing computer activities for nursing home residents with dementia. Nonpharmacol Ther Dement. (2013) 3:1–10.

100. De Boer B, Beerens H, Katterbach M, Viduka M, Willemse B, Verbeek H. The physical environment of nursing homes for people with dementia: traditional nursing homes, small-scale living facilities, and green care farms. Healthcare. (2018) 6:137.

101. den Ouden M, Bleijlevens M, Meijers J, Zwakhalen S, Braun S, Tan F, et al. Daily (in)activities of nursing home residents in their wards: an observation study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. (2015) 16:963–8.

102. Beerens H, de Boer B, Zwakhalen S, Tan F, Ruwaard D, Hamers J, et al. The association between aspects of daily life and quality of life of people with dementia living in long-term care facilities: a momentary assessment study. Int Psychogeriatr. (2016) 28:1323. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216000466

103. Nolan M, Grant G, Keady J. Understanding Family Care: A Multidimensional Model of Caring and Coping. Maidenhead: Open University Press (1996).

104. Campbell P, Wright J, Oyebode J, Job D, Crome P, Bentham P, et al. Determinants of burden in those who care for someone with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2008) 23:1078–85. doi: 10.1002/gps.2071

105. Montgomery R, Williams K. Implications of differential impacts of care-giving for future research on Alzheimer care. Aging Ment Health. (2001) 5:23–34. doi: 10.1080/13607860120044783

106. Janssen E, de Vugt M, Köhler S, Wolfs C, Kerpershoek L, Handels R, et al. Caregiver profiles in dementia related to quality of life, depression and perseverance time in the European actifcare study: the importance of social health. Aging Ment Health. (2017) 21:49–57. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2016.1255716

107. Vernooij-Dassen M, Jeon Y. Social health and dementia: the power of human capabilities. Int Psychogeriatr. (2016) 28:701–3.

108. Moon H, Adams K. The effectiveness of dyadic interventions for people with dementia and their caregivers. Dementia. (2013) 12:821–39. doi: 10.1177/1471301212447026

109. Moniz-Cook E, Hart C, Woods B, Whitaker C, James I, Russell I, et al. Challenge demcare: management of challenging behaviour in dementia at home and in care homes – development, evaluation and implementation of an online individualised intervention for care homes; and a cohort study of specialist community mental health care for families. Program Grants Appl Res. (2017) 5:1–290. doi: 10.3310/pgfar05150

110. Hoel V, Seibert K, Domhoff D, Preuß B, Heinze F, Rothgang H, et al. Social health among German nursing home residents with dementia during the Covid-19 pandemic, and the role of technology to promote social participation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2022) 19:1956. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19041956

Keywords: dementia, dyadic relationships, caregiving, enrichment, psychosocial interventions

Citation: Hoel V, Koh WQ and Sezgin D (2023) Enrichment of dementia caregiving relationships through psychosocial interventions: A scoping review. Front. Med. 9:1069846. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.1069846

Received: 14 October 2022; Accepted: 13 December 2022;

Published: 05 January 2023.

Edited by:

Daniella Pires Nunes, State University of Campinas, BrazilReviewed by:

Jan Oyebode, University of Bradford, United KingdomCopyright © 2023 Hoel, Koh and Sezgin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Viktoria Hoel,  aG9lbEB1bmktYnJlbWVuLmRl

aG9lbEB1bmktYnJlbWVuLmRl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.