- 1Department of Ophthalmology, Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei City, Taiwan

- 2Department of Internal Medicine, Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei City, Taiwan

- 3School of Public Health, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei City, Taiwan

- 4Department of Medical Research, Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei City, Taiwan

- 5Taiwanese Injury Prevention and Safety Promotion Association, Taipei City, Taiwan

- 6Department of Colon and Rectal Surgery, Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei City, Taiwan

- 7Graduate Institute of Life Sciences, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei City, Taiwan

Background: Ischemic optic neuropathy (ION) is a possible extraintestinal manifestation (EIM) of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). We investigate the relation between IBD and ION and possible risk factors associated with their incidence.

Methods: Medical records were extracted from the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2013. The main outcome was ION development. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed.

Results: We enrolled 22,540 individuals (4,508 with IBD, 18,032 without). The cumulative risk of developing ION was significantly greater for patients with IBD vs. patients without (Kaplan–Meier survival curve, p = 0.009; log-rank test). Seven (5%) and five (0.03%) patients developed ION in the IBD and control groups, respectively. Patients with IBD were significantly more likely to develop ION than those without IBD [adjusted hazard ratio (HR) = 4.135; 95% confidence interval: 1.312–11.246, p = 0.01]. Possible risk factors of ION development were age 30–39 years, diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, ischemic heart disease (IHD), atherosclerosis, and higher Charlson comorbidity index revised (CCI_R) value.

Conclusion: Patients with IBD are at increased risk of subsequent ION development. Moreover, for patients with comorbidities, the risk of ION development is significantly higher in those with IBD than in those without.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic relapsing and remitting intestinal disorder that is typically classified into two subtypes: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's disease (CD) (1). Both UC and CD are thought to occur in adolescents and adults equally in both genders (2). Ulcerative colitis causes superficial mucosal inflammation of the colon with a contiguous manner of extension. On the other hand, CD is characterized by skip lesions throughout the gastrointestinal tract and transmural inflammation (3).

The highest reported prevalence of IBD is in Europe and North America. In newly industrialized countries in Africa, Asia, and South America, the incidence of IBD has increased substantially since 1990, when these areas became more Westernized (4, 5). In Taiwan, a trend of increasing incidence of IBD (both UC and CD) and decreasing UC-to-CD ratio, especially among those aged 20–39 years, from 2001 to 2015 has been reported (6).

Extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) of IBD are common and estimated to affect approximately 6% to 47% of adult patients with IBD (7). Although the whole body can be involved, EIMs predominantly affect the skin, joints, biliary tract, and eyes (8). The prevalence of ocular manifestations in IBD range from 0.3 to 13%, based on the population studied, and they occur more frequently in patients with CD (3.5–6%) as compared with UC (1.6–4.6%) (7, 9, 10). The most frequent ocular manifestations observed in IBD patients are episcleritis, scleritis, and uveitis (8, 10). Among ophthalmic EIMs of IBD, some are potentially vision threatening with severe consequences if not treated properly (9–11). In addition, some ocular complications related to IBD treatments have also been reported (8). Ocular complications are usually independent of the extent of the underlying bowel disease and occur in the early years of the disease course (12).

Ischemic optic neuropathy (ION) is one of the possible ophthalmic manifestations of IBD (13). Ischemic optic neuropathy is classified as either anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (AION) or posterior ischemic optic neuropathy (PION), depending on which part of the optic nerve is involved. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy is more frequent and can be further divided into either arteritic anterior ION, which is often associated with giant cell arteritis, or non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION), which is the most common.

Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy remains the most common cause of acute optic neuropathy among elderly individuals (14). It typically affects patients older than 50 years (mean age at onset ranging from 57 to 65 years) (15), and the incidence has been reported to increase with advancing age (16). Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy causes sudden painless visual loss with positive relative afferent pupillary defect, optic disc edema, and altitudinal visual field defect. Some of the risk factors, such as crowding optic nerve head appearance (small optic nerve head with a small cup-to-disk ratio), diabetes mellitus (DM), systemic hypertension (HTN), hyperlipidemia, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) have been reported in the literature (17, 18).

The relation between IBD and ION (especially NAION) has not been well-established in the previous studies. Only a few case reports of the association between ION and CD have been reported. In addition, one of the cases had a personal history of common systemic risk factors related to NAION (13, 19, 20).

Although ION is rare among IBD patients, it has no proven therapy and could cause significant visual impairment in patients. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the relation between IBD and ION as well as the possible risk factors associated with the incidence of ION in patients with IBD.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

More than 99% of all of Taiwan's population (including foreigners) are enrolled in the single-payer National Health Insurance program. The National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD) of this program possesses registration files and original claim data for reimbursement. The use of NHIRD is limited to research purposes only, and applicants must follow the related laws and regulations of Taiwan.

This retrospective population-based cohort study contained fully anonymized medical records extracted from the NHIRD from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2013. All patient demographics (including age, gender, index year, related comorbidities) were recorded and analyzed.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tri-Service General Hospital (TSGHIRB No. 2-105-05-082). The need for participant informed consent was waived because of the fully anonymized data of NHIRD.

Patient Selection

We used the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) to identify the study population with a diagnosis of IBD (ICD-9-CM code 555, 556). Patients 20 years of age or older who had received medical codes of ICD-9-CM code 555, 556 once during hospitalization or at least three times during outpatient visits were included. Patients with a diagnosis of giant cell arteritis (ICD-9-CM code 446.5) from before 1 year to after 1 year of the index date were excluded. Furthermore, patients who diagnosed as having IBD before January 1, 2000, or with incomplete medical records, defined as incomplete insurance status or unrelated or incorrect given codes, were also excluded.

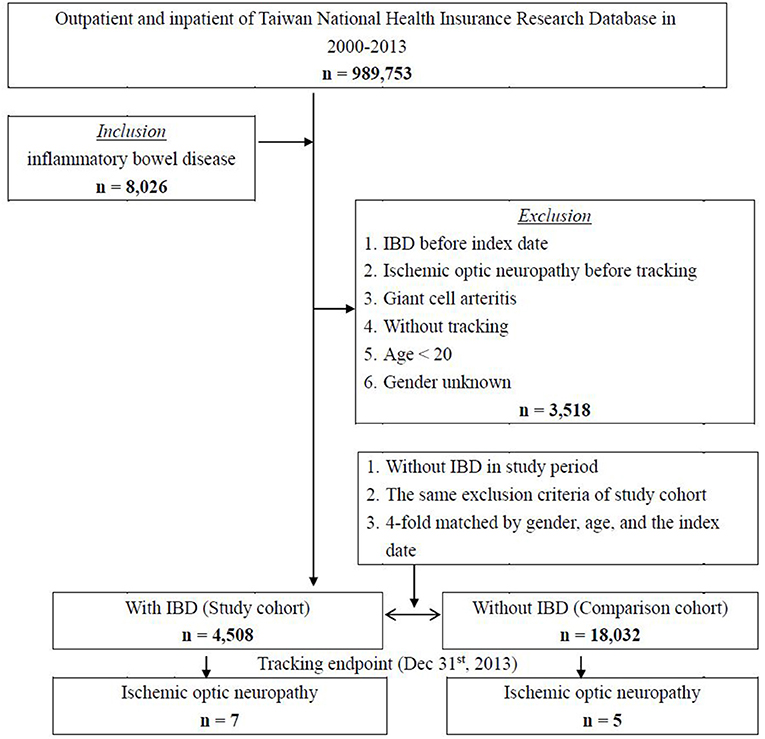

We selected a group of patients without IBD in the study period as a comparison cohort. This control group was four-fold the number of the IBD group and was matched to the patient's gender, age, and index date. The same exclusion criteria were applied to the control group. Patients were followed until the incidence of ION (ICD-9-CM code 377.41) was found in the records of outpatient or inpatient visits or until the end of the study period (December 31, 2013).

Comorbidities

We identified the following baseline comorbidities: DM, HTN, hypotension, hyperlipidemia, ischemic heart disease (IHD), atherosclerosis, OSA, renal failure, renal dialysis status, occlusion, and stenosis of the precerebral arteries, occlusion of the cerebral arteries, and hypercoagulable state. In addition, the Charlson comorbidity index revised (CCI_R) was used widely to assess the presence of chronic diseases. Supplementary Table 1 lists the ICD-9-CM codes used in this study for data extraction and analysis.

Study Outcome

The main outcome was a diagnosis of ION with ICD-9-CM codes (377.41). All subjects were followed from the index date until the occurrence of ION, the date of withdrawal from the insurance system, or the end of 2013.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed the characteristics of the patients and compared them between the IBD group and control group (without IBD) in terms of the baseline and the endpoint of this cohort. Categorical variables were reported as numbers and percentages, and continuous variables were reported as means ± standard deviations. Continuous variables in the two groups were compared using independent Student t-test; otherwise, Pearson chi-square test and Fisher exact test were used to evaluate the differences in categorical variables. Hazard ratios (HRs) for the association between potential clinical variables, including gender, age group, and related comorbidities, with the development of ION were evaluated using univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses. We also conducted multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) to examine possible effects of the cardiovascular-disease-related risk factors as covariant, including DM, occlusion, and stenosis of precerebral arteries, occlusion of cerebral arteries, and hypercoagulable state. Survival outcomes of ION development between the two cohorts were assessed using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by log-rank test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the patient selection process used in this cohort. A total of 8,025 patients with IBD were identified from the NHIRD database of 989,753 subjects from 2000 to 2013 in Taiwan. After 3,518 patients were excluded for reasons as listed, a study cohort of 4,508 patients with IBD was selected for further analyses. A four-fold group of 18,032 individuals matched by gender, age, and index date were selected as a control cohort.

Patients Characteristics

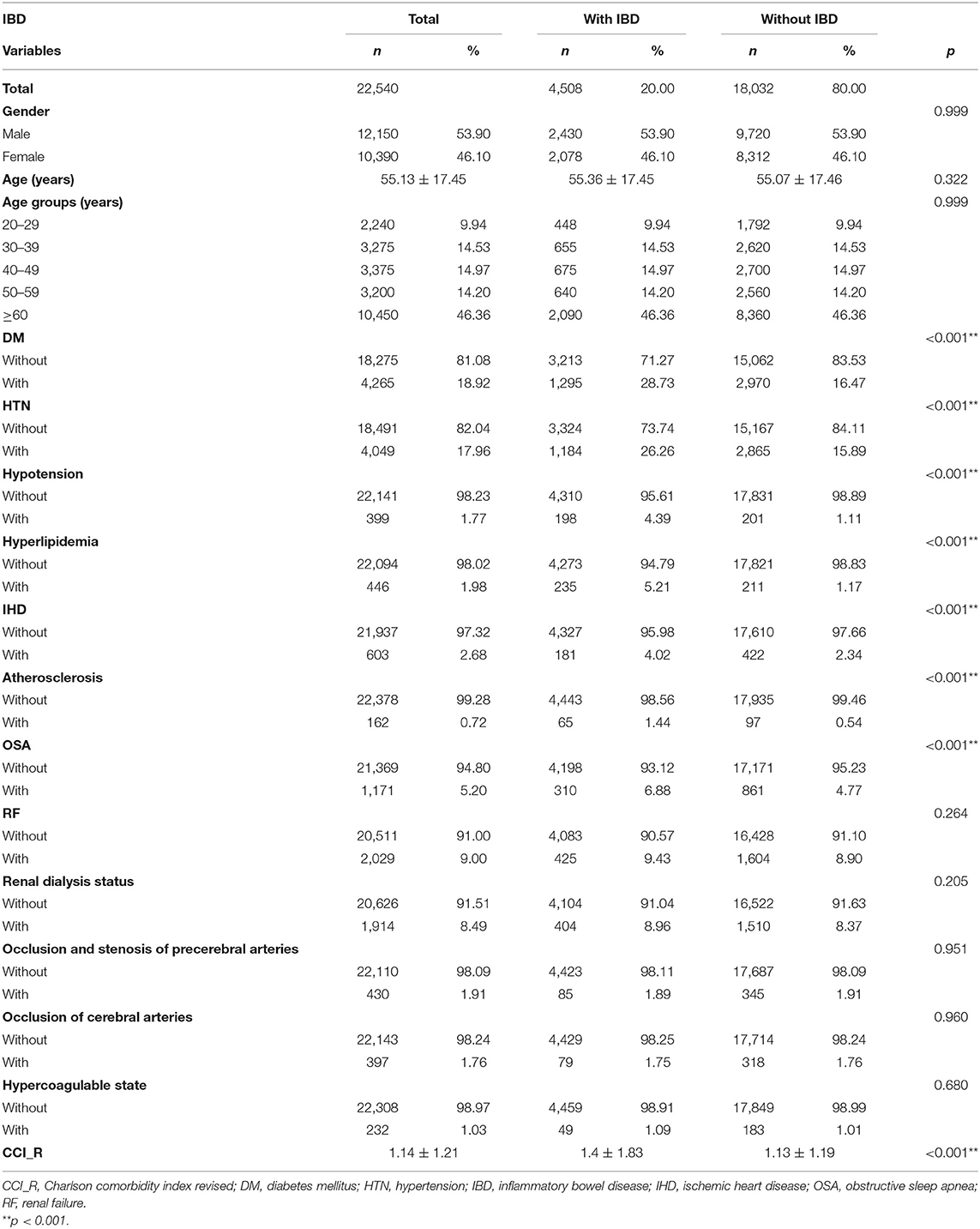

Table 1 lists the demographic characteristics of the enrolled patients at baseline. A total of 22,540 individuals were enrolled in this study, including 4,508 patients with IBD and 18,032 patients without IBD. The mean follow-up period in all patients was 7.53 ± 5.50 years (Supplementary Table 2-1). The mean ages of patients with and without IBD were 55.36 ± 17.45 and 55.07 ± 17.46 years, respectively. Among all age groups, most patients (46.36%) were aged 60 years or older. Considering the related comorbidities, DM, HTN, hypotension, hyperlipidemia, IHD, atherosclerosis, and OSA were found to be significantly increased (all p < 0.001) in patients with IBD as compared with patients without IBD. The CCI_R value was also significantly higher in the IBD group (p < 0.001).

Outcomes

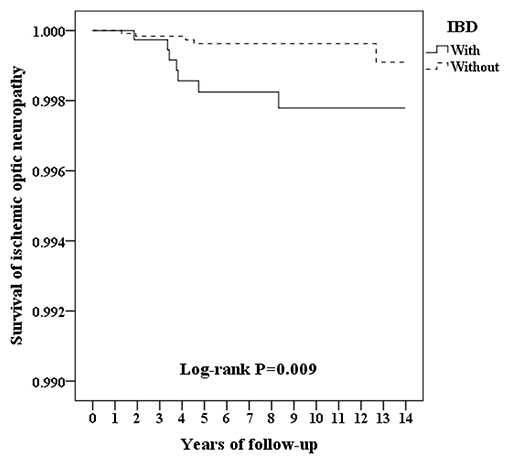

Figure 2 shows the Kaplan–Meier survival curve of the cumulative risk of developing ION in patients with and without IBD. The cumulative risk of ION development was significantly greater for patients with IBD vs. patients without IBD (p = 0.009; log-rank test). The mean survival time to ION development was 4.18 ± 2.02 years in patients with IBD and 4.92 ± 4.56 years in patients without IBD (Supplementary Table 2-2).

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier survival curve for ischemic optic neuropathy in patients with and without IBD.

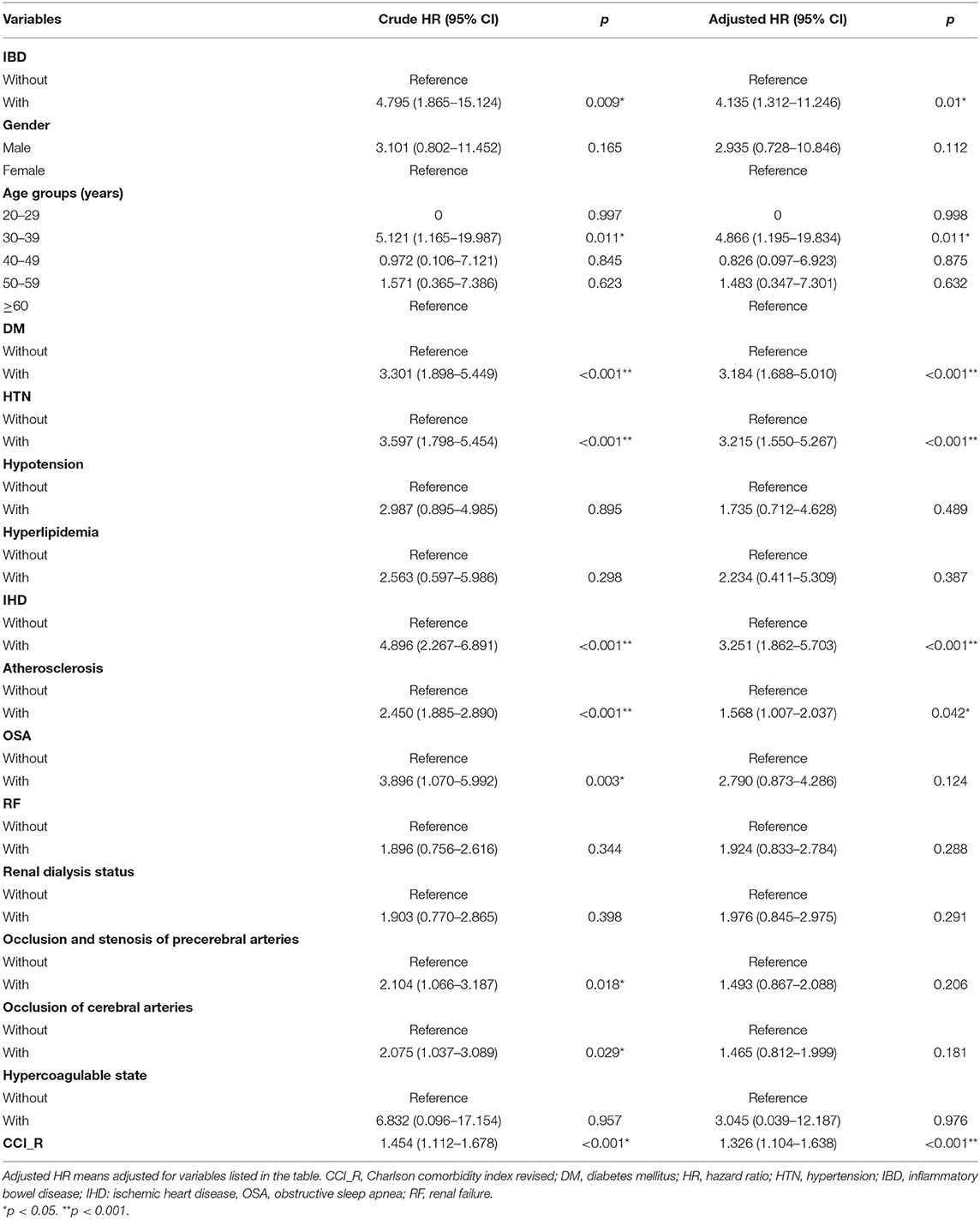

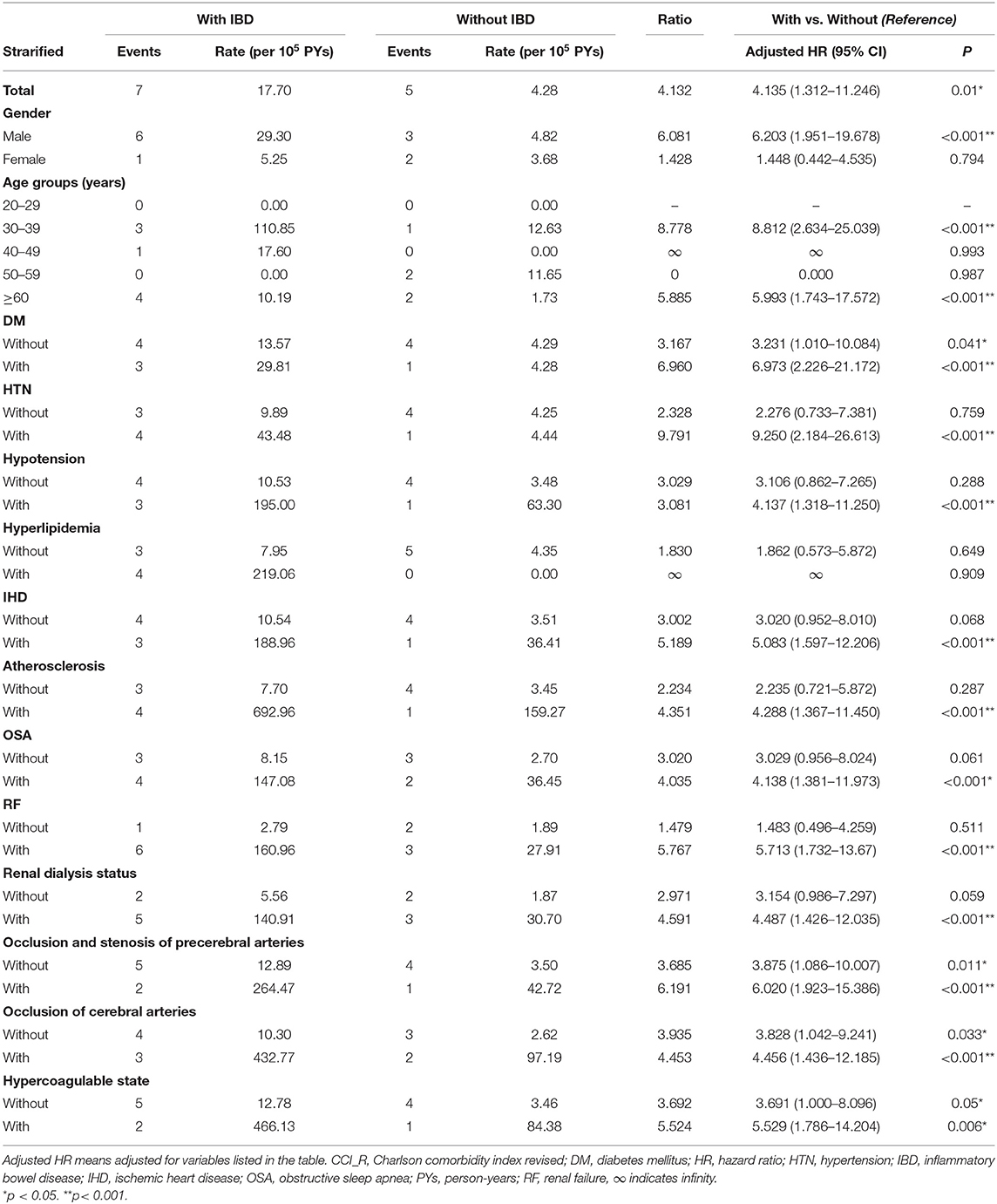

After we adjusted for confounding factors, multivariate analysis using Cox regression demonstrated that patients with IBD had a significantly higher probability of developing ION than did patients without IBD (adjusted HR = 4.135; 95% CI: 1.312–11.246, p = 0.01; Table 2). For other potential clinical variables evaluated by Cox regression analyses, age between 30 and 39 years; patients with underlying comorbidities of DM, HTN, IHD, or atherosclerosis; and patients with higher CCI_R score had a significantly higher probability of developing ION (Table 2). The cardiovascular-disease-related risk factors were entered as covariant into a MANCOVA analysis, which revealed IBD was statistically significantly associated with the incidence of ION (Wilks' lambda = 0.125, F = 2.709, p = 0.003), confirming in consistent with our result.

We further conducted stratified subgroup analyses by multivariate Cox regression; the results are provided in Table 3. At the study endpoint, seven (5%) patients with IBD and five (0.03%) patients without IBD developed ION. Supplementary Table 3 shows the detailed information of IBD and Non-IBD patients who developed ION in this cohort. The overall incidence rate of ION was 17.7 per 100,000 person-years in patients with IBD and 4.28 per 100,000 person-years in patients without IBD. Male patients with IBD had a significantly higher risk of ION development as compared with male patients without IBD (adjusted HR = 6.203; 95% CI: 1.951–19.678, p < 0.001). For patients aged 30–39 years and ≥60 years, IBD was significantly associated with risks of developing ION (adjusted HR = 8.812; 95% CI: 2.634–25.039; p < 0.001; and adjusted HR = 5.993; 95% CI: 1.743–17.572; p < 0.001, respectively). Inflammatory bowel disease also significantly increased the risk of ION development, whether or not patients had DM, occlusion and stenosis of the precerebral arteries, occlusion of the cerebral arteries, and hypercoagulable state. Nevertheless, the significance was more prominent in patients with these comorbidities as compared with patients without these comorbidities. Among all other clinical variables, the adjusted HRs were significantly higher in IBD patients with HTN, hypotension, IHD, atherosclerosis, OSA, renal failure, and renal dialysis status (adjusted HR = 9.25, 4.137, 5.083, 4.288, 4.138, 5.713, and 4.487, respectively; all p < 0.001).

Table 3. Risk analysis for ischemic optic neuropathy stratified by demographic and clinical characteristics between patients with/without IBD.

Discussion

We conducted a 13-year follow-up population-based study using data obtained from the Taiwan NHIRD. To our knowledge, this is the first cohort study to investigate the associations between ION and IBD and to evaluate the possible risk factors in the incidence of ION in IBD patients. As compared with patients without IBD, those with IBD had a statistically significant higher risk of developing ION. In addition, age 30–39 years; presence of DM, HTN, IHD, or atherosclerosis; and higher CCI_R scores were identified as significant risk factors for the development of ION.

The etiopathogenesis of NAION is controversial and still debated (21). The disease entity is considered to be an acute ischemic insult of the optic nerve head secondary to low blood flow in the posterior ciliary arteries (13, 21, 22). Multiple factors may correlate with the incidence of NAION, including local predisposing factors (e.g., crowding optic nerve head appearance, optic disc drusen), precipitating factors (e.g., severe hypotension, impaired autoregulation of the disc circulation, posterior vitreous detachment, general anesthesia, or dialysis), and systemic vascular diseases (e.g., OSA, HTN, DM, hyperlipidemia) (21, 23). In this study, we found a significantly higher risk of developing ION in IBD patients after adjusting for confounding factors. The interplay between ION and IBD remains unclear. It might be multifactorial and requires further investigation. Some theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiological mechanisms of ophthalmic complications of IBD, including vaso-occlusive phenomena (24), action of antigen–antibody complexes produced against the vessels of the bowel wall (9), occlusion secondary to inflammation or hypercoagulability (22), and side effects related to IBD treatment (8, 25, 26).

Some possible risk factors of ION development were identified by multivariate Cox regression in this cohort, including age 30–39 years; presence of DM, HTN, IHD, or atherosclerosis; and higher CCI_R score. Ambiguities exist in studies regarding the possible association between gender and ophthalmic manifestations of IBD. Bernstein et al. described the association between female sex and ocular manifestation in IBD, but only iritis and uveitis were analyzed in that study (27). According to the results of our study (although not significant) and previous case reports of ION in IBD (in which all patients were male) (13, 19, 20), there may be a male predilection for ION development in IBD patients. Patients aged 30–39 years showed a significantly higher risk of ION development. This age peak in the incidence of ION might be due to the fact that IBD patients tend to develop at least one EIM within 15 years of disease diagnosis, and most are diagnosed in their 20s to 30s (28). Among all other possible risk factors, most are correlated with systemic vascular diseases. Because ION is presumed to be a vascular disease of the optic nerve head (29), the presence of these comorbidities in IBD patients may imply some synergistic effects on ION development. Nevertheless, further study is needed to elucidate their relation and underlying mechanisms.

There are several strengths of this study. First, this was a nationwide population-based cohort study from a million-level database in Taiwan. Because of its large sample size and the long-term follow-up period, the study provided relatively good statistical power for this rare disease in IBD patients. Second, a four-fold control group matched by gender, age, and index date was selected for comparison. In addition, possible confounding factors were adjusted during multivariate Cox regression analysis.

However, several study limitations should be noted. First, nearly all study participants were from the Taiwan population, thus preventing generalization and the application of the study results to patients from other racial or ethnic groups. A study conducted in the United States concluded that Asians (US-born Asians and Asian immigrants) are more likely to have ocular EIM as compared with White patients (3.4 vs. 0.7%, p = 0.022) (30). In contrast, another systemic review showed that no major differences in EIM between African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians (31).

Another limitation is that the medications prescribed (either for IBD or other diseases) were not stratified in this study, and consequently, the influence of medication treatment could not be ruled out. There is no ultimate treatment of IBD and the treatment-related side effects should be considered individually. Among all of the current treatments of IBD, there was no reported correlation with ION (32, 33). Either treatment-related complications or possible protective effects of IBD drugs toward the ION development need further studies to investigate.

To date, there are no definitive, proven treatments or prophylaxes for NAION (21, 34, 35). Because most of the NAION patients have one or more vascular risk factors (18, 36), controlling these systemic risk factors remains an important issue and is always suggested. Moreover, the stage and severity of the underlying diseases might have some influence on the hazard of developing NAION (37). Third, the NHIRD database does not provide blood test and imaging data such as magnetic resonance imaging or fundus images. The ION could be identified only by the ICD-9-CM codes as described. As a result, the possibility of misdiagnosis cannot be ruled out in this study. Finally, we did not analyze the influence of other ocular manifestations and treatment-related ocular complications on the incidence of ION in IBD patients.

In conclusion, patients with IBD are at increased risk of subsequent ION development during follow-up in this cohort. In addition, among patients with some comorbidities, especially systemic vascular risk factors, the risks of ION development were significantly higher in those with IBD than in those without IBD. It is important for the clinician to remain vigilant regarding visual complaints in IBD patients. If IBD patients present with systemic vascular risk factors, these factors should be properly treated. Furthermore, regular ophthalmic follow-up in IBD patients, especially those with higher risk, may be of great importance.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Board of Tri-Service General Hospital. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

T-YL, W-CC, and Y-HH: conceptualization and validation. T-YL, Y-FL, P-HC, C-HC, P-CK, and W-CC: methodology. T-YL and Y-HH: literature search. C-HC and W-CC: data acquisition, statistical analysis, and data curation. T-YL, Y-FL, P-HC, C-HC, W-CC, P-CK, and Y-HH: data analysis and investigation. T-YL: manuscript preparation. P-HC, C-HC, C-LC, Y-HC, J-TC, W-CC, and Y-HH: manuscript editing. C-HC, C-LC, Y-HC, J-TC, P-CK, W-CC, and YHH: supervision. Y-HH and W-CC: project administration and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Tri-Service General Hospital Research Foundation (TSGH-B-110012 and TSGH-D-110110), and the sponsor has no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We also appreciate the Health and Welfare Data Science Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare (HWDC, MOHW), Taiwan, for providing the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.753367/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Graham DB, Xavier RJ. Pathway paradigms revealed from the genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. (2020) 578:527–39. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2025-2

2. Seyedian SS, Nokhostin F, Malamir MD. A review of the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment methods of inflammatory bowel disease. J Med Life. (2019) 12:113–22. doi: 10.25122/jml-2018-0075

3. Chang JT. Pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel diseases. N Engl J Med. (2020) 383:2652–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2002697

4. Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, Underwood FE, Tang W, Benchimol EI, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. (2017) 390:2769–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32448-0

5. Alatab S, Sepanlou SG, Ikuta K, Vahedi H, Bisignano C, Safiri S, et al. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study (2017). Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2020) 5:17–30. doi: 10.1016/s2468-1253(19)30333-4

6. Yen H-H, Weng M-T, Tung C-C, Wang Y-T, Chang YT, Chang C-H, et al. Epidemiological trend in inflammatory bowel disease in Taiwan from 2001 to 2015: a nationwide populationbased study. Intest Res. (2019) 17:54–62. doi: 10.5217/ir.2018.00096

7. Chams S, Badran R, Sayegh SE, Chams N, Shams A, Hajj Hussein I. Inflammatory bowel disease: looking beyond the tract. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. (2019) 33:2058738419866567. doi: 10.1177/2058738419866567

8. Marotto D, Atzeni F, Ardizzone S, Monteleone G, Giorgi V, Sarzi-Puttini P. Extra-intestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel diseases. Pharmacol Res. (2020) 161:105206. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105206

9. Troncoso LL, Biancardi AL, de Moraes HV Jr, Zaltman C. Ophthalmic manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a review. World J Gastroenterol. (2017) 23:5836–48. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i32.5836

10. Castellano F, Alessio G, Palmisano C. Ocular manifestations of inflammatory bowel diseases: an update for gastroenterologists. Minerva Gastroenterol (Torino). (2021) 67:91–100. doi: 10.23736/s1121-421x.20.02727-0

11. Annese V. A Review of extraintestinal manifestations and complications of inflammatory bowel disease. Saudi J Med Med Sci. (2019) 7:66–73. doi: 10.4103/sjmms.sjmms_81_18

12. Hopkins DJ, Horan E, Burton IL, Clamp SE, de Dombal FT, Goligher JC. Ocular disorders in a series of 332 patients with Crohn's disease. Br J Ophthalmol. (1974) 58:732–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.58.8.732

13. Felekis T, Katsanos KH, Zois CD, Vartholomatos G, Kolaitis N, Asproudis I, et al. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in a patient with Crohn's disease and aberrant MTHFR and GPIIIa gene variants. J Crohns Colitis. (2010) 4:471–4. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.02.008

14. Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Decompression Trial Research G. Ischemic optic neuropathy decompression trial: twenty-four–month update. Arch Ophthalmol. (2000) 118:793–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.6.793

15. Miller NR, Arnold AC. Current concepts in the diagnosis, pathogenesis and management of nonarteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy. Eye (Lond). (2015) 29:65–79. doi: 10.1038/eye.2014.144

16. Lee J-Y, Park K-A, Oh SY. Prevalence and incidence of non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy in South Korea: a nationwide population-based study. Brit J Ophthalmol. (2018) 102:936–41. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311140

17. Farahvash A, Micieli JA. Neuro-ophthalmological manifestations of obstructive sleep apnea: current perspectives. Eye Brain. (2020) 12:61–71. doi: 10.2147/EB.S247121

18. Behbehani R, Ali A, Al-Moosa A. Risk factors and visual outcome of Non-Arteritic Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (NAION): experience of a tertiary center in Kuwait. PLoS ONE. (2021). 16:e0247126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247126

19. Heuer DK, Gager WE, Reeser FH. Ischemic optic neuropathy associated with Crohn's disease. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. (1982) 2:175–81.

20. Nemati R, Mehdizadeh S, Salimipour H, Yaghoubi E, Alipour Z, Tabib SM, et al. Neurological manifestations related to Crohn's disease: a boon for the workforce. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). (2019) 7:291–7. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gox034

21. Augstburger E, Héron E, Abanou A, Habas C, Baudouin C, Labbé A. Acute ischemic optic nerve disease: pathophysiology, clinical features and management. J Fr Ophtalmol. (2020) 43:e41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2019.12.002

22. Katsanos A, Asproudis I, Katsanos KH, Dastiridou AI, Aspiotis M, Tsianos EV. Orbital and optic nerve complications of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. (2013) 7:683–93. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.09.020

23. Arnold AC. Pathogenesis of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol. (2003) 23:157–63. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200306000-00012

24. Ghanchi FD, Rembacken BJ. Inflammatory bowel disease and the eye. Surv Ophthalmol. (2003) 48:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2003.08.004

25. Chan JW, Castellanos A. Infliximab and anterior optic neuropathy: case report and review of the literature. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. (2010) 248:283–7. doi: 10.1007/s00417-009-1227-y

26. Fine S, Nee J, Thakuria P, Duff B, Farraye FA, Shah SA. Ocular, auricular, and oral manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. (2017) 62:3269–79. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4781-x

27. Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Rawsthorne P, Yu N. The prevalence of extraintestinal diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. (2001) 96:1116–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03756.x

28. Jose FA, Garnett EA, Vittinghoff E, Ferry GD, Winter HS, Baldassano RN, et al. Development of extraintestinal manifestations in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. (2009) 15:63–8. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20604

29. Arnold AC. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Semin Ophthalmol. (1995) 10:221–33. doi: 10.3109/08820539509060976

30. Kochar B, Barnes EL, Herfarth HH, Martin CF, Ananthakrishnan AN, McGovern D, et al. Asians have more perianal Crohn disease and ocular manifestations compared with white Americans. Inflamm Intest Dis. (2017) 2:147–53. doi: 10.1159/000484347

31. Afzali A, Cross RK. Racial and ethnic minorities with inflammatory bowel disease in the United States: a systematic review of disease characteristics and differences. Inflamm Bowel Dis. (2016) 22:2023–40. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000835

32. Actis GC, Pellicano R, Rizzetto M, Ayoubi M, Leone N, Tappero G, et al. Individually administered or co-prescribed thiopurines and mesalamines for inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. (2009) 15:1420–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1420

33. Beaugerie L, Rahier J-F, Kirchgesner J. Predicting, preventing, and managing treatment-related complications in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2020). 18:1324.e2–35.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.02.009

34. Foroozan R. New Treatments for nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Neurol Clin. (2017) 35:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2016.08.003

35. Newman NJ, Scherer R, Langenberg P, Kelman S, Feldon S, Kaufman D, et al. The fellow eye in naion: report from the ischemic optic neuropathy decompression trial follow-up study. Am J Ophthalmol. (2002) 134:317–28. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(02)01639-2

36. Preechawat P, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in patients younger than 50 years. Am J Ophthalmol. (2007) 144:953–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.07.031

Keywords: chron's disease, extraintestinal manifestation, inflammatory bowel diseases, ischemic optic neuropathy, ocular manifestation, ulcerative colitis

Citation: Lin T-Y, Lai Y-F, Chen P-H, Chung C-H, Chen C-L, Chen Y-H, Chen J-T, Kuo P-C, Chien W-C and Hsieh Y-H (2021) Association Between Ischemic Optic Neuropathy and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-Based Cohort Study in Taiwan. Front. Med. 8:753367. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.753367

Received: 04 August 2021; Accepted: 31 August 2021;

Published: 28 September 2021.

Edited by:

Michele Lanza, University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli, ItalyReviewed by:

Chun-Hung Chang, China Medical University Hospital, TaiwanTsai-Ching Hsu, Chung Shan Medical University, Taiwan

Sebastian Yu, Kaohsiung Medical University, Taiwan

Rinaldo Pellicano, Molinette Hospital, Italy

Copyright © 2021 Lin, Lai, Chen, Chung, Chen, Chen, Chen, Kuo, Chien and Hsieh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wu-Chien Chien, Y2hpZW53dSYjeDAwMDQwO25kbWN0c2doLmVkdS50dw==; Yun-Hsiu Hsieh, dnY3Nzg4NDQyMjAwJiN4MDAwNDA7Z21haWwuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share last authorship

Ting-Yi Lin

Ting-Yi Lin Yi-Fen Lai1

Yi-Fen Lai1 Po-Huang Chen

Po-Huang Chen Chi-Hsiang Chung

Chi-Hsiang Chung Ching-Long Chen

Ching-Long Chen Wu-Chien Chien

Wu-Chien Chien