- 1Department of Neurosurgery, National Neuroscience Institute, Singapore, Singapore

- 2Tan Tock Seng Hospital, Singapore, Singapore

- 3Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, Singapore

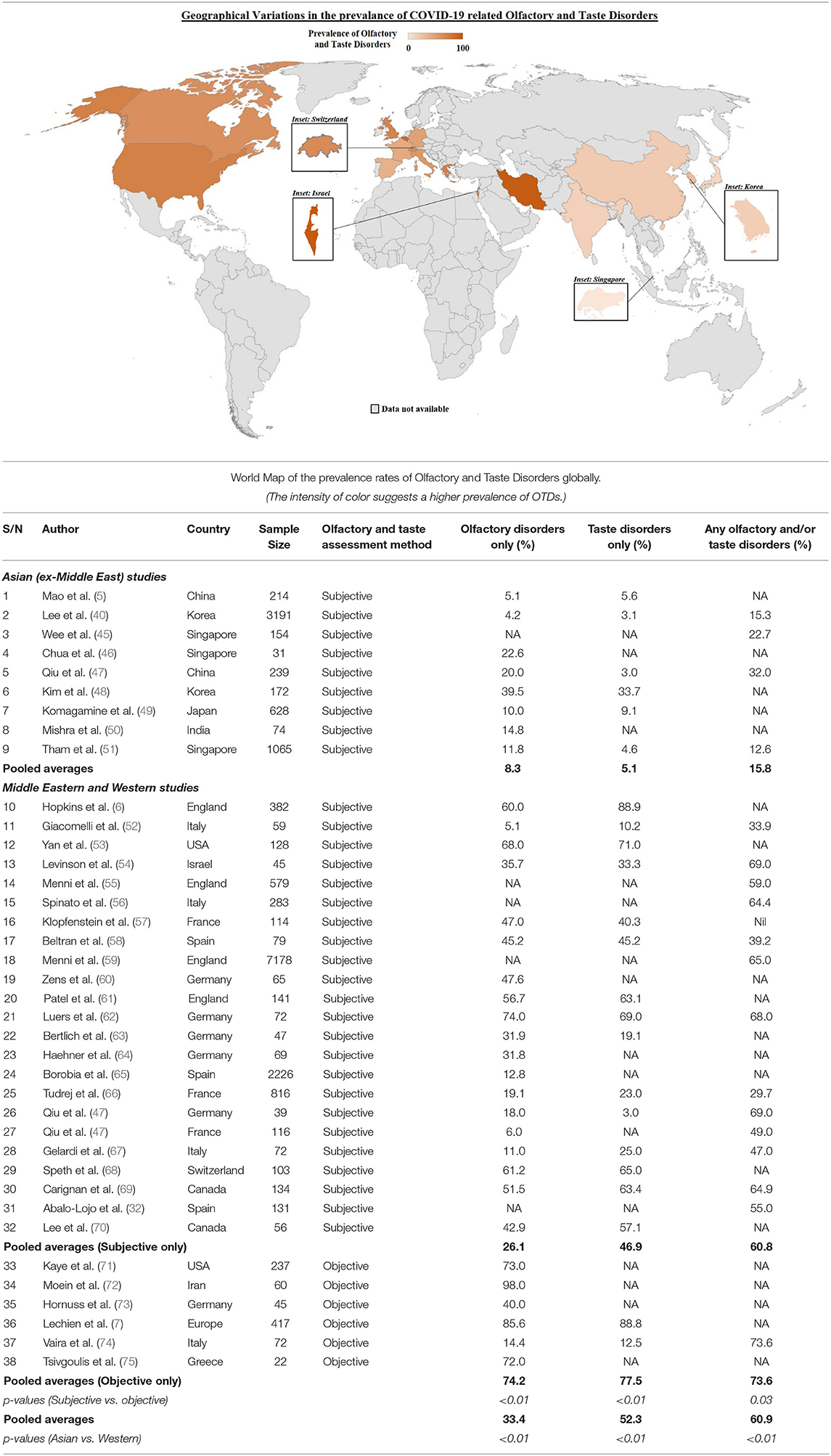

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), has become the most critical global health challenge in recent history. With SARS-CoV-2 infection, there was an unexpectedly high and specific prevalence of olfactory and taste disorders (OTDs). These high rates of hyposmia and hypogeusia, initially reported as up to 89% in European case series, led to the global inclusion of loss of taste and/or smell as a distinctive feature of COVID-19. However, there is emerging evidence that there are striking differences in the rates of OTDs in East Asian countries where the disease first emerged, as compared to Western countries (15.8 vs. 60.9%, p-value < 0.01). This may be driven by either variations in SARS-CoV-2 subtypes presenting to different global populations or genotypic differences in hosts which alter the predisposition of these different populations to the neuroinvasiveness of SARS-CoV-2. We also found that rates of OTDs were significantly higher in objective testing for OTDs as compared to subjective testing (73.6 vs. 60.8%, p-value = 0.03), which is the methodology employed by most studies. Concurrently, it has also become evident that racial minorities across geographically disparate world populations suffer from disproportionately higher rates of COVID-19 infection and mortality. In this mini review, we aim to delineate and explore the varying rates of olfactory and taste disorders amongst COVID-19 patients, by focusing on their underlying geographical, testing, ethnic and socioeconomic differences. We examine the current literature for evidence of differences in the olfactory and gustatory manifestations of COVID-19 and discuss current pathophysiological hypotheses for such differences.

Introduction

The novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the resultant coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is the largest pandemic in recent history. As of 24th January 2021, there have been 96, 877, 399 confirmed cases and 2, 098, 879 confirmed deaths in 224 countries and territories, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The first cases of COVID-19 were described in Wuhan, China, in late 2019 (1), with initial presenting complaints related to acute respiratory illnesses (ARI) (2–4). However, as the pandemic developed, relatively minor symptoms such as anosmia and ageusia were discovered to be disproportionately important to the presentation and understanding of COVID-19 pathophysiology.

Olfactory and taste disorders (OTDs) were first described in February 2020 by Mao et al. (5) in their retrospective case series describing neurological manifestations amongst COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. Out of 314 patients, they reported 5.1% hyposmia and 5.6% hypogeusia (5). As the pandemic spread to Europe, media and anecdotal accounts from medical practitioners supported such reports of OTDs (6). In early April, Lechien et al. (7) published a multicentre cross-sectional study based in several European countries, with 417 patients, of which 85.6 and 88.8% were found to have olfactory dysfunction and gustatory dysfunction, respectively. Shortly after this, multiple otolaryngology chapters released statements recommending that OTDs be considered as symptoms of COVID-19 (8–10). This was followed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), United States of America (USA), and the Ministry of Health, Singapore adding “loss of smell or taste” to the list of symptoms of COVID-19 in mid-April. The World Health Organization and the Department of Health and Social Care, United Kingdom (UK), officially added “loss of taste or smell” to their respective list of symptoms of COVID-19 in early May.

Anosmia, ageusia and the entire spectrum of OTDs are of importance to our understanding of COVID-19 because they provide an opportunity to learn more about the neurotropic effects of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and allow us to study the potential long-term neurological effects that SARS-CoV-2 infection can lead to, even in patients with mild COVID-19 infections. It is interesting to note, that despite the initial surge of COVID-19 cases in Asia, the literature highlighting OTDs was primarily based on patients in Europe and the USA.

In this mini review we explore the different possible reasons behind these geographical differences in OTD rates, such as the initial stress on Asian healthcare systems, different viral genotypes and differing pathogenic susceptibility of different populations. We also examine variations seen in OTD rates in studies utilizing subjective testing as compared to objective testing. We describe the differences seen between different ethnic groups and explore if genetic determinants can account for the disproportionate affliction of minority races, and other factors such as comorbidity burden and socio-economic status. We also highlight developing trends such as the gender differences in anosmia and ageusia as well as the use of real-time trackers.

Methodology

We performed searches for studies examining olfactory and gustatory dysfunction amongst COVID-19 patients in databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar and Web of Science. In view of the time-sensitive nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, preprint databases such as Medrxiv and Biorxiv were also utilized to capture latest developments. Search terms utilized included “Anosmia in COVID-19,” “Ageusia in COVID-19,” “Olfactory disorders in COVID-19,” “Gustatory disorders in COVID-19” and other related search terms. Original studies, commentaries and review articles were considered during the literature review. Studies with original data on OTDs were included for comparison and analysis, with the original reported rates of OTDs reflected without any secondary analysis. Pooled averages were calculated for comparison between different geographical regions. Statistical analysis was carried out by SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS, IBM Corporation, IL, USA), and Pearsons Chi-square tests were performed, with p < 0.05 regarded as statistically significant.

Hypothesized Pathophysiological Processes for the Development of Anosmia and Ageusia

SARS-CoV-2 is closely related to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – which have each caused their own epidemics associated with extrapulmonary manifestations and high mortality rates (11, 12). The functional receptor allowing for SARS-CoV-2 entry into host cells is human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (13), and this viral entry is facilitated by transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2), similar to SARS-CoV (14, 15). ACE2 is found in the human airway epithelia, lung parenchyma, vascular endothelia, kidney cells and small intestine cells (16, 17).

SARS-CoV-2 is postulated to be able to infect the CNS in a similar manner to SARS-CoV, via a hematogenous and trans-neuronal route, with cell entry mediated by ACE2 receptors (18). SARS-CoV-2 in the bloodstream may interact with ACE2 expressed in the capillary endothelium of cerebral vessels, and allow viral access to the brain, after which the virus can interact with ACE2 receptors expressed in neurons (18). Viral interaction with the olfactory bulb and cortex may lead to neuronal damage and resultant hyposmia or anosmia (18–21). The trans-neuronal spread of the virus has also been hypothesized to damage the peripheral neurons directly (18, 22, 23). However, olfactory neurons do not express significant levels of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 (24–27) and neuronal damage to the olfactory bulb and cortex cannot account for case reports of rapid and transient anosmia (7), in view of such damage requiring significant time for recovery (27).

Another proposed mechanism for anosmia is damage to non-neuronal structures that support olfactory function, such as olfactory epithelium sustentacular cells, microvillar cells, Bowman's gland cells, horizontal basal cells and olfactory bulb pericytes (25). These olfactory epithelium sustentacular cells have abundant expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 (24, 25, 28, 29). Local infection of these non-neuronal structures is proposed to cause significant inflammatory responses affecting olfactory sensory neurons or olfactory bulb neurons, and may even result in neuronal death (25). Reports of transient anosmia, with rapid recovery, may then be explained by the faster regeneration rate of sustentacular cells, as compared to olfactory neurons (20, 27).

Regarding ageusia, ACE2 receptors are known to diffusely express on the mucous membranes of the oral cavity, with a high concentration on the tongue (30). It is thought that ACE2 modulates taste perception, and that SARS-CoV-2 binding to the receptor may lead to taste dysfunction by damaging the gustatory cells, even though the exact mechanism is unclear (31, 32). One proposed mechanism is the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to sialic acid receptors, an ability it shares with MERS-CoV (33). This binding of SARS-CoV-2 to sialic acid receptors may result in the acceleration of degradation of gustatory particles, resulting in blunting of the patient's taste (31). Another possibility is that ageusia happens concomitantly with anosmia due to the close functional correlations between the olfactory and gustatory chemosensory systems (34).

Emerging evidence on neuroimaging characteristics of anosmic patients may also assist to elucidate the definite pathophysiology of COVID-19 associated OTDs. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of COVID-19 patients with OTDs have shown olfactory bulb injury (19) and changes (35–37), suggesting the viral invasion of these nerve structures with resultant sensorineural dysfunction. The persistence of OTDs is also an area of interest, with studies suggesting a persistence of symptoms in up to 24% of COVID-19 patients (38, 39), and interesting trends such as younger patients and female patients having a higher tendency for such persistence (40). It may be only possible with time to elucidate the exact pathophysiological elements leading to OTDs in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and histological biopsies of COVID-19 patients are likely to greatly aid this effort (27).

Geographical Variations

Anosmia, ageusia and OTDs amongst COVID-19 patients were first recognized to be common in Europe, several months after the first few COVID-19 epicenters in Asia. Asian studies were consistently publishing lower percentages of patients presenting with anosmia and ageusia compared to those being reported in Europe and the USA, with one study reporting the prevalence of chemosensory dysfunction in Caucasians to be three times higher than that in Asians (27, 41–44). Table 1 illustrates the difference in pooled average prevalence of olfactory disorders, taste disorders and combined olfactory and/or taste disorders between Eastern and Western populations, with a map graphically representing the higher prevalence of OTDs in Western countries. The pooled average for the Western population was close to 4 times that of the Eastern populations (15.8 vs. 60.9%, p-value < 0.01) as seen in Table 1. Three main reasons have been postulated in the literature with regards to this difference between Western populations and Eastern populations.

Firstly, there was the shock element of the initial outbreak. In the initial stages of the outbreak, when it was first recognized in Asia, patients who were critically ill would have been prioritized and hospitalized. Indeed, the literature from the early days of the pandemic highlighted concerns regarding mortality and need for intensive care therapy (76, 77), suggesting that the patients presenting to the healthcare institutions were indeed more unwell. It has been suggested that minor symptoms such as anosmia and ageusia may have been overlooked in preliminary cohorts in the pandemic, both by medical professionals, as well as patients themselves (7, 43). This could have led to an under-reporting of actual anosmia and ageusia rates in Asian countries in the initial stages of the outbreak. However, over time, this has become a less viable explanation, in view of studies from other Asian countries also showing significantly lower rates of anosmia and ageusia as compared to Western nations (40, 45).

The second possible reason is that of differing viral genotypes in Asia as compared to Europe and the USA. A phylogenetic analysis of 160 SARS-CoV-2 genomes by Forster et al. (78) found 3 central variants of the virus: Types A, B and C. Types A and C were found to be more prevalent amongst Europeans and Americans, compared to Type B which was more prevalent amongst Asians (78). Types A and C are speculated to have high pathogenicity for the nasal cavity, hence resulting in the higher prevalence of olfactory and taste disorders in Western populations (43, 78). Mutations in the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the virus spike protein (subunit S1) may also result in differing viral tropism and infectivity (79). Mutations in the RBD have been shown to affect its binding to the ACE2 receptor (80, 81), and these mutations can impact the pathogenicity of the virus (82). Indeed, early studies probing interactions between ACE2 coding variants and SARS-CoV-2 virus have pointed to certain populations having a higher predisposition for SARS-CoV-2 binding (83). The emergence of new variants such as the UK variant (84) and South African variant (85) in late 2020 and early 2021 lend further credence to the presence of differing viral genotypes in distinct geographical territories. These variants may have differing rates of infectivity of the olfactory epithelium which may influence the prevalence of OTDs (27).

Finally, differing pathogenic susceptibility, in the form of genetic variations of host proteins and receptors such as ACE2 and TMPRSS2, may have led to the difference in anosmia and ageusia rates between different populations. Variations in ACE2 expression in different populations have been reported (86, 87), with one study finding increased ACE2 expression in tissues in East Asian populations (88). Variations in TMPRSS2 protein frequency have also been observed with European populations having much higher levels of pulmonary expression as compared to East Asian populations (20). Genetic differences in ACE2 variants, characterized by post-translational modifications such as glycosylation, may also contribute to the varying susceptibility of different populations to anosmia (27, 89). Such genetic differences resulting in differing OTD rates were corroborated by a Singaporean study, which collected nationality and ethnicity data, and found that Caucasians were 3.05 times more likely to have OTDs as compared to Chinese, South East Asian and West Asian races (51). Further research is required to delineate the link between ACE2/TMPRSS2 expression and susceptibility to olfactory and taste disorders.

The high susceptibility to OTDs amongst Western populations as compared to East Asian populations, raises the specter of whether these same Western populations are facing a higher burden of SARS-CoV-2 related peripheral and central nervous system disorders. The same reasons of possibly different viral genotypes and differing pathogenic susceptibility can also be used to explain any corresponding spike in both PNS and CNS manifestations in Western populations as compared to Eastern populations. We should note that directly comparing prevalence of neurological symptoms between studies has proven to be difficult, largely due to the heterogenous nature of recorded neurological symptoms such as headache, giddiness and altered mental state – especially as they may be manifestations of systemic disease as well (90, 91). Nevertheless, comparing CNS syndromes, such as encephalitis, and PNS syndromes, such as mono or polyneuropathies, reveals no evidence of increased rates of such syndromes amongst Western populations compared to Eastern populations thus far (92, 93).

Testing Variations

The majority of the literature concerning COVID-19 and OTDs has been based on patient self-reporting (94). This may inevitably lead to inconsistences (52, 94), such as recall bias on the part of the patient, or confirmation bias on the part of the medical professional. Objective forms of testing have been proposed and utilized in some studies, such as the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT), Questionnaire of Olfactory Disorders–Negative Statements (95, 96), COVID-19 Anosmia Reporting Tool (71), Sniffin' sticks test, and Korean version of Sniffin' sticks test (KVSS) (97). Broadly, studies utilizing objective testing for anosmia and ageusia have found a higher prevalence of olfactory and gustatory disturbances amongst COVID-19 patients (72, 98). Table 1 highlights the differences in OTD rates between objective and subjective testing, seen in the differing prevalence rates, in favor of objective testing (60.8 vs. 73.6%, p-value = 0.03). We can hypothesize that the reasons behind under-reporting of anosmia or ageusia may be due to difficulties in perceiving a reduction in sense of smell or taste (99) as well as difficulties in finding and receiving an appropriate level of care (100), which may be linked to socio-economic issues, further elaborated on below. It has to be appreciated however, that self-reporting of symptoms may often be the only feasible and practical way of data collection, especially with pandemic precautions and restrictions (44).

Ethnic, Comorbidity and Socio-Economic Variations

COVID-19 has disproportionately affected racial minorities across the world, with infection rates and mortality rates two to three times higher in these minorities than their proportion in the population (101–106). Ethnic, socio-economic and comorbidity variations all have a role in accounting for this higher affliction rate amongst racial minorities (105).

Variations in OTDs, due to COVID-19, between different ethnicities residing in the same region, have yet to be described fully in the literature. We know from pre-COVID studies that anosmia is more prevalent amongst African-Americans as compared to Caucasians in the USA (107). Dong et al. described the prevalence of anosmia amongst African-Americans as 22.3%, as compared to 10.4% amongst Caucasians, but were unable to account for this stark racial disparity (107). As such, it would not be surprising if anosmia rates in African-American COVID-19 patients were higher than in other ethnicities. A possible explanation may be in the differences in ACE2 expression. A reduced molecular expression of ACE2 in African-descent populations has been described (108), which should theoretically lead to a lower incidence of COVID-19 in these populations, contrary to reality. Vinciguerra et al. proposed that whilst this reduced expression of ACE2 can lead to lower susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection, once infected, the clinical manifestations may be worse, due to progression of inflammatory and thrombotic processes as a result of such reduced ACE2 expression (109). TMPRSS2 may also play a part in the ethnic variations in anosmia. Ethnic differences in TMPRSS2 gene-related activity in prostate tissue have been associated with a higher incidence of prostate cancer in African-American men, as compared to Caucasian men, in the USA (110). This ethnic difference was found to be similar for nasal gene expression of TMPRSS2. In a study of 305 unique nasal epithelial samples, African-Americans were found to have statistically significantly higher TMPRSS2 expression as compared to Asian, Latino, mixed race and Caucasian individuals (111). TMPRSS2 is known to be essential in SARS-CoV-2 cell entry (15), suggesting a possible reason behind the higher burden of COVID-19 infection amongst African-Americans in the USA, possibly holding true for anosmia as well.

Comorbidity burden has been positively correlated with the severity of COVID-19 and mortality (112). This is of particular interest when analysing the impact of COVID-19 on minority races, as comorbidity burdens in ethnic minorities have been found to be higher (101, 105, 113, 114). Several comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic kidney disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have been reported in higher percentages amongst COVID-19 mortality statistics (115). The impact of comorbidities are further highlighted when considering that mortality rates amongst African-American and Caucasian patients in the USA are not significantly different when comorbidities are corrected for (116). However, anosmia tends to affect individuals with fewer comorbidities, except for asthma, which was found to be of a high proportion in patients presenting with anosmia (7, 57). This could possibly be due to anosmia being the only symptom in mild and moderate COVID-19 infections, which tend to occur more often in patients with no or low comorbidity burdens (7). This implies that COVID-19 patients with only isolated OTDs may have a milder disease process.

Possibly the most important piece in explaining the higher proportion of racial minorities being infected with COVID-19 is the socio-economic aspect of the disease. Poverty has been associated with a higher risk of intensive care unit admissions in the USA (117), and a large study in Brazil found that patients from lower socio-economic regions had a higher mortality rate (102). Patients in lower socio-economic regions also have more comorbidities, suggesting that structural health disparities and poor access to healthcare result in poorly controlled chronic diseases (102, 103). People from lower socio-economic classes were also unable to comply with pandemic measures such as social distancing or working from home, due to their crowded living conditions or the blue-collar occupations that many hold (101, 105, 115). In Scotland, COVID-19 patients living in areas with the greatest socio-economic deprivation had a higher frequency of critical care admission and a higher adjusted 30-day mortality, with healthcare facilities in areas with higher socio-economic deprivation also operating at higher occupancy rates (118). The relationship between OTDs and socio-economic status alludes to the differing access to healthcare between different socio-economic groups. A pre-COVID-19 study in South Korea found that high-income population groups had a 1.4 times higher incidence of anosmia as compared to low-income population groups (119). The authors attributed this to the accessibility of medical care to patients with different income levels, and concluded that anosmia can be frequently underestimated by the elderly and low-income due to their economic situation, which hinders them from seeking medical care (119). We can hypothesize that the incidence of OTDs in lower socio-economic groups may be higher in the COVID-19 outbreak, but may not be reflected in the data due to socio-economic factors that hinder their access to healthcare. Future studies on the prevalence of OTDs in different socio-economic groups affected by COVID-19 will help to corroborate this hypothesis.

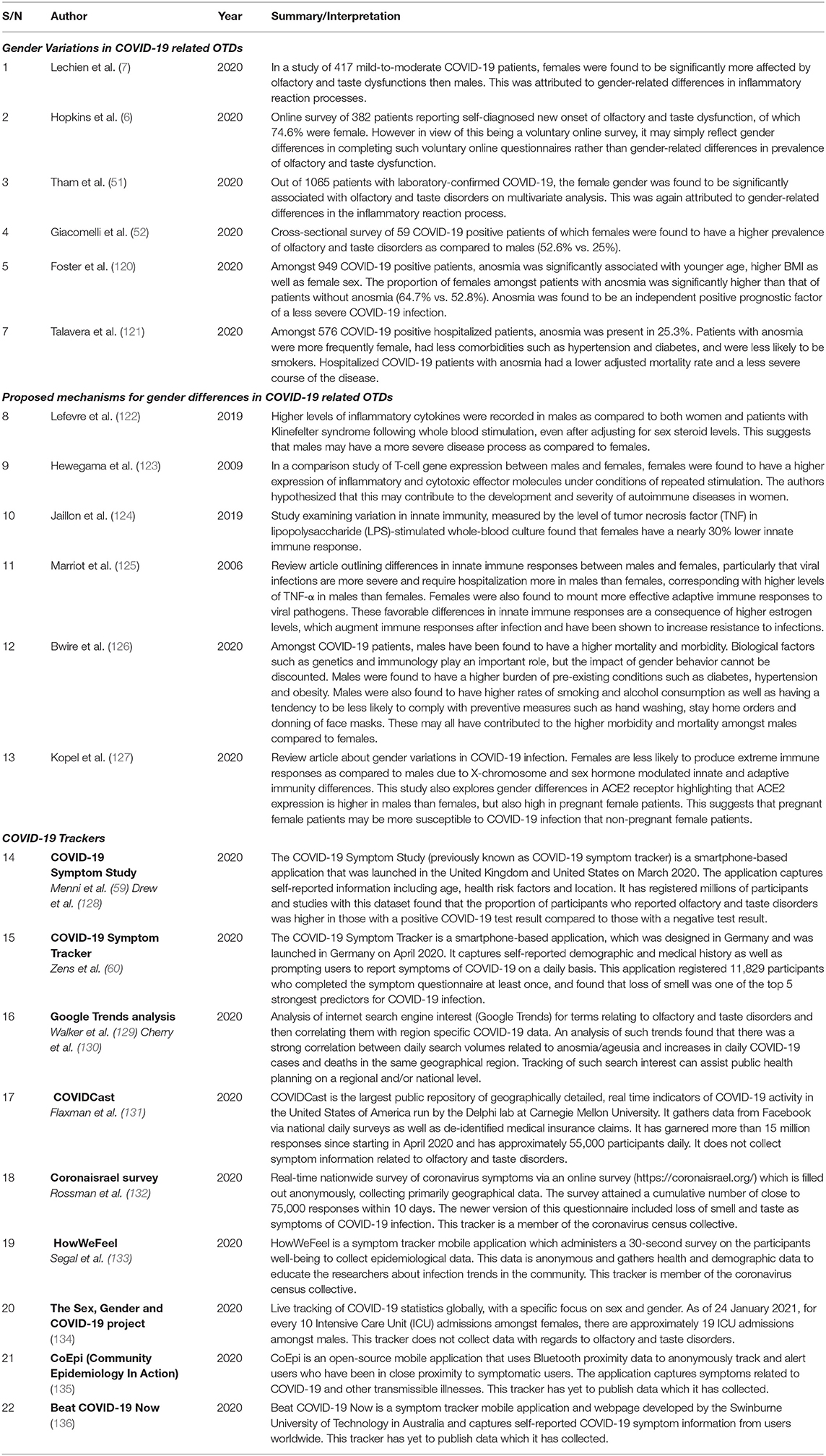

In addition to the inequalities described above, there may be emerging evidence that gender distinguishes both susceptibility to COVID-19 and associated complications such as anosmia and ageusia (Table 2); further study is required to explain such differences. The ability for public health and research groups to mobilize the efforts of its “citizen scientist” community during this pandemic has also been key to illustrating emerging or unusual trends, such as OTDs, in the form of trackers (Table 2). Despite the limitations of these trackers, they provide both helpful and near real-time updates of disease prevalence as well as gauge societal attitudes toward such group efforts in global health.

Table 2. Gender Variations in COVID-19 related olfactory and taste disorders (OTDs) and COVID-19 trackers.

Conclusion

Anosmia and ageusia have become well-recognized symptoms of this current pandemic. Much has changed since the original case reports about olfactory and taste disorders, but there are still many questions that remain unanswered regarding how biological and societal factors influence the impact of SARS-CoV-2. In this mini review, we categorize and collate current available literature in order to describe the differences in OTDs seen in different geographical regions as well as amongst different ethnicities and socio-economic conditions. We believe our study to be the first mini review to compare and contrast the variously reported global variations in OTDs. Concurrently, we have provided an up-to-date report on the disproportionate influence of ethnic, comorbidity and socio-economic factors toward such variations. Understanding such inequalities may highlight areas of consideration for allocation of resources and focused attention. Further research is also required to elucidate the exact pathophysiological mechanisms underpinning the phenomena of anosmia and ageusia in COVID-19 and account for other variations, such as the importance of gender toward the clinical phenotype of disease.

Author Contributions

AK, CL, and NK: conceived of the direction and scope of the review and performed the literature reviews and compilation of references. AK and SL: wrote the manuscript with supervision and direction from CL and NK. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This research was supported in part by grants from SingHealth Duke-NUS (AM/CSP006/2020) and the National Medical Research Council (MOH-000303-00).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Eng J Med. (2020) 382:727–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017

2. Guan W-j, Ni Z-y, Hu Y, Liang W-h, Ou C-q, He J-x, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Eng J Med. (2020) 382:1708–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032

3. Wang Z, Yang B, Li Q, Wen L, Zhang R. Clinical Features of 69 Cases With Coronavirus Disease. (2019). Wuhan: Clinical infectious diseases.

4. Chan JF-W, Yuan S, Kok K-H, To KK-W, Chu H, Yang J, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. (2020) 395:514–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9

5. Mao L, Wang M, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, et al. Neurological manifestations of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective case series study. Medrxiv. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.02.22.20026500

6. Hopkins C, Surda P, Whitehead E, Kumar BN. Early recovery following new onset anosmia during the COVID-19 pandemic – an observational cohort study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. (2020) 49:26. doi: 10.1186/s40463-020-00423-8

7. Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, Horoi M, Le Bon SD, Rodriguez A, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Oto Rhino Laryngol. (2020) 277:2251–61. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1

8. UK E. Anosmia as a Potential Marker of COVID-19 Infection – an Update (2020). Available online at: https://www.entuk.org/anosmia-potential-marker-covid-19-infection-%E2%80%93-update (accessed February 01, 2021).

9. AAO-HNS. AAO-HNS: Anosmia, Hyposmia and Dysgeusia Symptoms of Coronavirus Disease (2020). Available online at: https://www.entnet.org/content/aao-hns-anosmia-hyposmia-and-dysgeusia-symptoms-coronavirus-disease (accessed February 01, 2021).

10. Chapter of Otorhinolaryngologists S. Acute olfactory and gustatory dysfunction as a symptom of COVID-19 infection: Joint statement of the Chapter of Otorhinolaryngologists, College of Surgeons, Singapore and the Society of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. Singapore: In press. (2020).

11. Matías-Guiu J, Gomez-Pinedo U, Montero-Escribano P, Gomez-Iglesias P, Porta-Etessam J, Matias-Guiu JA. Should we expect neurological symptoms in the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic? Neurologia. (2020) 35:170–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nrleng.2020.03.002

12. Swanson II PA, McGavern DB. Viral diseases of the central nervous system. Curr Opin Virol. (2015) 11:44–54. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.12.009

13. Natoli S, Oliveira V, Calabresi P, Maia LF, Pisani A. Does SARS-Cov-2 invade the brain? Translational lessons from animal models. Eur J Neurol. (2020) 27:1764–73. doi: 10.1111/ene.14277

14. Li W, Moore MJ, Vasilieva N, Sui J, Wong SK, Berne MA, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. (2003) 426:450–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02145

15. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. (2020) 181:271–80.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052

16. Kam Y-W, Okumura Y, Kido H, Ng LFP, Bruzzone R, Altmeyer R. Cleavage of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein by airway proteases enhances virus entry into human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro. PLoS ONE. (2009) 4:e7870. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007870

17. Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, Lely AT, Navis G, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. (2004) 203:631–7. doi: 10.1002/path.1570

18. Baig AM, Khaleeq A, Ali U, Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: tissue distribution, host–virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chem Neuro. (2020) 11:995–8. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00122

19. Aragão M, Leal MC, Cartaxo Filho OQ, Fonseca TM, Valença MM. Anosmia in COVID-19 associated with injury to the olfactory bulbs evident on MRI. Am J Neuroradiol. (2020). 41:1703–6. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6675

20. DosSantos MF, Devalle S, Aran V, Capra D, Roque NR, Coelho-Aguiar JdM, et al. Neuromechanisms of SARS-CoV-2: A Review. Front Neuro. (2020) 14:37. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2020.00037

21. Ahmed MU, Hanif M, Ali MJ, Haider MA, Kherani D, Memon GM, et al. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2): a review. Front Neurol. (2020) 11:518. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00518

22. Ueha R, Kondo K, Kagoya R, Shichino S, Shichino S, Yamasoba T. ACE2, TMPRSS2, and Furin expression in the nose and olfactory bulb in mice and humans. Rhinology. (2021) 59:105–109. doi: 10.4193/Rhin20.324

23. Meinhardt J, Radke J, Dittmayer C, Mothes R, Franz J, Laue M, et al. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat Neurosci, (2021) 24, 168–75. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00758-5

24. Bilinska K, Jakubowska P, Von Bartheld CS, Butowt R. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 entry proteins, ACE2 and TMPRSS2, in cells of the olfactory epithelium: identification of cell types and trends with age. ACS Chem Neuro. (2020) 11:1555–62. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00210

25. Brann DH, Tsukahara T, Weinreb C, Lipovsek M, Van den Berge K, Gong B, et al. Non-neuronal expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the olfactory system suggests mechanisms underlying COVID-19-associated anosmia. Sci Adv. (2020) 6:eabc5801. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abc5801

26. Ziegler CGK, Allon SJ, Nyquist SK, Mbano IM, Miao VN, Tzouanas CN, et al. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell. (2020) 181:1016–35.e19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.035

27. Butowt R, von Bartheld CS. Anosmia in COVID-19: underlying mechanisms and assessment of an olfactory route to brain infection. Neuroscientist. (2020) 11:1073858420956905. doi: 10.1177/1073858420956905

28. Klingenstein M, Klingenstein S, Neckel PH, Mack AF, Wagner A, Kleger A, et al. Evidence of SARS-CoV2 Entry Protein ACE2 in the Human Nose and Olfactory Bulb. Cells Tissues Organs, (2020) 209:155–64. doi: 10.1159/000513040

29. Chen M, Shen W, Rowan NR, Kulaga H, Hillel A, Ramanathan M, et al. Elevated ACE-2 expression in the olfactory neuroepithelium: implications for anosmia and upper respiratory SARS-CoV-2 entry and replication. Eur Respir J. (2020) 56:2001948. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01948-2020

30. Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, Peng J, Dan H, Zeng X, et al. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci. (2020) 12:8. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x

31. Vaira LA, Salzano G, Fois AG, Piombino P, De Riu G. Potential pathogenesis of ageusia and anosmia in COVID-19 patients. Int Forum Aller Rhinol. (2020) 10:1103–4. doi: 10.1002/alr.22593

32. Abalo-Lojo JM, Pouso-Diz JM, Gonzalez F. Taste and smell dysfunction in COVID-19 patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. (2020) 129:1041–2. doi: 10.1177/0003489420932617

33. Milanetti E, Miotto M, Rienzo LD, Monti M, Gosti G, Ruocco G. In-Silico evidence for two receptors based strategy of SARS-CoV-2. Biorxiv. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.006197

34. Small DM, Prescott J. Odor/taste integration and the perception of flavor. Exp Brain Res. (2005) 166:345–57. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-2376-9

35. Politi LS, Salsano E, Grimaldi M. Magnetic resonance imaging alteration of the brain in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Anosmia. JAMA Neurol. (2020) 77:1028–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2125

36. Laurendon T, Radulesco T, Mugnier J, Gérault M, Chagnaud C, El Ahmadi A-A, et al. Bilateral transient olfactory bulb edema during COVID-19–related anosmia. Neurology. (2020) 95:224–5. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009850

37. Tsivgoulis G, Fragkou PC, Lachanis S, Palaiodimou L, Lambadiari V, Papathanasiou M, et al. Olfactory bulb and mucosa abnormalities in persistent COVID-19-induced anosmia: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Eur J Neurol. (2021) 28:e6–e8. doi: 10.1111/ene.14537

38. Nguyen NN, Hoang VT, Lagier J-C, Raoult D, Gautret P. Long-term persistence of olfactory and gustatory disorders in COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Inf. (2021). doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.12.021

39. Lovato A, Galletti C, Galletti B, de Filippis C. Clinical characteristics associated with persistent olfactory and taste alterations in COVID-19: a preliminary report on 121 patients. Am J Otolaryngol. (2020) 41:102548. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102548

40. Lee Y, Min P, Lee S, Kim S-W. Prevalence and duration of acute loss of smell or taste in COVID-19 patients. J Korean Med Sci. (2020) 35:1–6. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e174

41. Mullol J, Alobid I, Mariño-Sánchez F, Izquierdo-Domínguez A, Marin C, Klimek L, et al. The loss of smell and taste in the COVID-19 outbreak: a tale of many countries. Cur Aller Asthma Rep. (2020) 20:61. doi: 10.1007/s11882-020-00961-1

42. Lovato A, de Filippis C. Clinical presentation of COVID-19: A systematic review focusing on upper airway symptoms. Ear Nose Throat J. (2020) 99:569–76. doi: 10.1177/0145561320920762

43. Meng X, Deng Y, Dai Z, Meng Z. COVID-19 and anosmia: a review based on up-to-date knowledge. Am J Otolaryngol. (2020) 41:102581. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102581

44. von Bartheld CS, Hagen MM, Butowt R. Prevalence of chemosensory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis reveals significant ethnic differences. ACS Chem Neuro. (2020) 11:2944–61. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00460

45. Wee LE, Chan YFZ, Teo NWY, Cherng BPZ, Thien SY, Wong HM, et al. The role of self-reported olfactory and gustatory dysfunction as a screening criterion for suspected COVID-19. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. (2020) 277:2389–90. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-05999-5

46. Chua AJ, Charn TC, Chan EC, Loh J. Acute olfactory loss is specific for COVID-19 at the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. (2020) 76:550–1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.05.015

47. Qiu C, Cui C, Hautefort C, Haehner A, Zhao J, Yao Q, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunction as an early identifier of COVID-19 in adults and children: an international multicenter study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. (2020) 163:714–21. doi: 10.1177/0194599820934376

48. Kim GU, Kim MJ, Ra SH, Lee J, Bae S, Jung J, et al. Clinical characteristics of asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with mild COVID-19. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2020) 26:948.e1-.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.040

49. Komagamine J, Yabuki T. Initial symptoms of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Japan: a descriptive study. J Gen Family Med. (2021) 1:61–64. doi: 10.1002/jgf2.378

50. Mishra P, Gowda V, Dixit S, Kaushik M. Prevalence of New Onset Anosmia in COVID-19 Patients: Is The Trend Different Between European and Indian Population? Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2020) 72:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s12070-020-01986-8

51. Tham AC, Thein T-L, Lee CS, Tan GSE, Manauis CM, Siow JK, et al. Olfactory taste disorder as a presenting symptom of COVID-19: a large single-center Singapore study. Eur Archiv Otorhinolaryngol. (2020) 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00405-020-06455-0. [Epub ahead of print].

52. Giacomelli A, Pezzati L, Conti F, Bernacchia D, Siano M, Oreni L, et al. Self-reported olfactory and taste disorders in patients with severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 infection: a cross-sectional study. Clin Inf Dis. (2020) 71:889–90. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa330

53. Yan CH, Faraji F, Prajapati DP, Boone CE, DeConde AS. Association of chemosensory dysfunction and COVID-19 in patients presenting with influenza-like symptoms. Int Forum AllerRhinol. (2020) 10:806–13. doi: 10.1002/alr.22579

54. Levinson R, Elbaz M, Ben-Ami R, Shasha D, Levinson T, Choshen G, et al. Time course of anosmia and dysgeusia in patients with mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Infect Dis (Lond). (2020) 52:600–2. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2020.1772992

55. Menni C, Valdes A, Freydin MB, Ganesh S, El-Sayed Moustafa J, Visconti A, et al. Loss of smell and taste in combination with other symptoms is a strong predictor of COVID-19 infection. Medrxiv. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.04.05.20048421

56. Spinato G, Fabbris C, Polesel J, Cazzador D, Borsetto D, Hopkins C, et al. Alterations in smell or taste in mildly symptomatic outpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA. (2020) 323:2089–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6771

57. Klopfenstein T, Toko L, Royer P-Y, Lepiller Q, Gendrin V, Zayet S. Features of anosmia in COVID-19. Méd Malad Infect. (2020) 50:436–9. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.04.006

58. Beltrán-Corbellini Á, Chico-García JL, Martínez-Poles J, Rodríguez-Jorge F, Natera-Villalba E, Gómez-Corral J, et al. Acute-onset smell and taste disorders in the context of COVID-19: a pilot multicentre polymerase chain reaction based case-control study. Eur J Neurol. (2020) 27:e34. doi: 10.1111/ene.14359

59. Menni C, Valdes AM, Freidin MB, Sudre CH, Nguyen LH, Drew DA, et al. Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential COVID-19. Nat Med. (2020) 26:1037–40. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0916-2

60. Zens M, Brammertz A, Herpich J, Südkamp N, Hinterseer M. App-based tracking of self-reported COVID-19 symptoms: analysis of questionnaire data. J Med Internet Res. (2020) 22:e21956. doi: 10.2196/21956

61. Patel A, Charani E, Ariyanayagam D, Abdulaal A, Denny SJ, Mughal N, et al. New-onset anosmia and ageusia in adult patients diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2020) 26:1236–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.05.026

62. Luers JC, Rokohl AC, Loreck N, Wawer Matos PA, Augustin M, Dewald F, et al. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19). Clin Infect Dis. (2020) 71:2262–64. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa525

63. Bertlich M, Stihl C, Weiss BG, Canis M, Haubner F, Ihler F. Characteristics of impaired chemosensory function in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. SSRN Electr J. (2020). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3576889

64. Haehner A, Draf J, Draeger S, Hummel T. Predictive value of sudden olfactory loss in the diagnosis of COVID-19. ORL. (2020) 82:175–80. doi: 10.1159/000509143

65. Borobia AM, Carcas AJ, Arnalich F, Álvarez-Sala R, Montserrat J, Quintana M, et al. A cohort of patients with COVID-19 in a major teaching hospital in Europe. J. Clin Medi. (2020) 9:1733. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061733

66. Tudrej B, Sebo P, Lourdaux J, Cuzin C, Floquet M, Haller DM, et al. Self-reported loss of smell and taste in SARS-CoV-2 patients: primary care data to guide future early detection strategies. J Gener Int Med. (2020) 35:2502–4. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05933-9

67. Gelardi M, Trecca E, Cassano M, Ciprandi G. Smell and taste dysfunction during the COVID-19 outbreak: a preliminary report. Acta Biomed. (2020) 91:230–1. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9524

68. Speth MM, Singer-Cornelius T, Oberle M, Gengler I, Brockmeier SJ, Sedaghat AR. Olfactory dysfunction and sinonasal symptomatology in COVID-19: prevalence, severity, timing, and associated characteristics. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. (2020) 163:114–20. doi: 10.1177/0194599820929185

69. Carignan A, Valiquette L, Grenier C, Musonera JB, Nkengurutse D, Marcil-Héguy A, et al. Anosmia and dysgeusia associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: an age-matched case–control study. Can Med Assoc J. (2020) 192:E702–7. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200869

70. Lee DJ, Lockwood J, Das P, Wang R, Grinspun E, Lee JM. Self-reported anosmia and dysgeusia as key symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019. CJEM. (2020) 22:595–602. doi: 10.1017/cem.2020.420

71. Kaye R, Chang CWD, Kazahaya K, Brereton J, Denneny JC 3rd. COVID-19 anosmia reporting tool: initial findings. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2020) 163:132–4. doi: 10.1177/0194599820922992

72. Moein ST, Hashemian SM, Mansourafshar B, Khorram-Tousi A, Tabarsi P, Doty RL. Smell dysfunction: a biomarker for COVID-19. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. (2020) 10:944–50. doi: 10.1002/alr.22587

73. Hornuss D, Lange B, Schroeter N, Rieg S, Kern WV, Wagner D. Anosmia in COVID-19 patients. Medrxiv. (2020) 26, P1426–1427. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.28.20083311

74. Vaira LA, Deiana G, Fois AG, Pirina P, Madeddu G, De Vito A, et al. Objective evaluation of anosmia and ageusia in COVID-19 patients: single-center experience on 72 cases. Head Neck. (2020) 42:1252–8. doi: 10.1002/hed.26204

75. Tsivgoulis G, Fragkou PC, Delides A, Karofylakis E, Dimopoulou D, Sfikakis PP, et al. Quantitative evaluation of olfactory dysfunction in hospitalized patients with coronavirus [2] (COVID-19). J Neurol. (2020) 267:2193–5. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09935-9

76. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. (2020) 323:1061–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585

77. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. (2020) 395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

78. Forster P, Forster L, Renfrew C, Forster M. Phylogenetic network analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Proc Nat Acad Sci. (2020) 117:9241–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004999117

79. Shang J, Ye G, Shi K, Wan Y, Luo C, Aihara H, et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. (2020) 581:221–4. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y

80. Ou J, Zhou Z, Dai R, Zhao S, Wu X, Zhang J, et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD mutants that enhance viral infectivity through increased human ACE2 receptor binding affinity. Biorxiv. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.03.15.991844

81. Jia Y, Shen G, Zhang Y, Huang K-S, Ho H-Y, Hor W-S, et al. Analysis of the mutation dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 reveals the spread history and emergence of RBD mutant with lower ACE2 binding affinity. Biorxiv. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.04.09.034942

82. Yao H, Lu X, Chen Q, Xu K, Chen Y, Cheng L, et al. Patient-derived mutations impact pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2. Medrxiv. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.04.14.20060160

83. Ali F, Elserafy M, Alkordi MH, Amin M. ACE2 coding variants in different populations and their potential impact on SARS-CoV-2 binding affinity. Bio Biop Rep. (2020) 24:100798. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrep.2020.100798

84. Tang JW, Tambyah PA, Hui DSC. Emergence of a new SARS-CoV-2 variant in the UK. J Infect. (2021) 82:e27–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.12.024

85. Tang JW, Toovey OTR, Harvey KN, Hui DDS. Introduction of the South African SARS-CoV-2 variant 501Y.V2 into the UK. J Infect. (2021) 82:e8–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.01.007

86. Benetti E, Tita R, Spiga O, Ciolfi A, Birolo G, Bruselles A, et al. ACE2 gene variants may underlie interindividual variability and susceptibility to COVID-19 in the Italian population. Eur J Hum Genet. (2020) 28:1602–14. doi: 10.1038/s41431-020-0691-z

87. Strafella C, Caputo V, Termine A, Barati S, Gambardella S, Borgiani P, et al. Analysis of ACE2 genetic variability among populations highlights a possible link with COVID-19-related neurological complications. Genes. (2020) 11:741. doi: 10.3390/genes11070741

88. Cao Y, Li L, Feng Z, Wan S, Huang P, Sun X, et al. Comparative genetic analysis of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2) receptor ACE2 in different populations. Cell Dis. (2020) 6:11. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0147-1

89. Li Q, Wu J, Nie J, Zhang L, Hao H, Liu S, et al. The impact of mutations in SARS-CoV-2 spike on viral infectivity and antigenicity. Cell. (2020) 182:1284–94.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.012

90. Pezzini A, Padovani A. Lifting the mask on neurological manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Rev Neurol. (2020) 16:636–44. doi: 10.1038/s41582-020-0398-3

91. Ellul M, Varatharaj A, Nicholson TR, Pollak TA, Thomas N, Easton A, et al. Defining causality in COVID-19 and neurological disorders. J Neurol Neuro Psychiatry. (2020) 91:811–2. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323667

92. Romero-Sánchez CM, Díaz-Maroto I, Fernández-Díaz E, Sánchez-Larsen Á, Layos-Romero A, García-García J, et al. Neurologic manifestations in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. The ALBACOVID registry. Neurology. (2020) 95:e1060–70. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009937

93. Koh JS, De Silva DA, Quek AML, Chiew HJ, Tu TM, Seet CYH, et al. Neurology of COVID-19 in Singapore. J Neurol Sci. (2020) 418:117118. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.117118

94. Agyeman AA, Chin KL, Landersdorfer CB, Liew D, Ofori-Asenso R. Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. (2020) 95:1621–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.05.030

95. Bhattacharyya N, Kepnes LJ. Contemporary assessment of the prevalence of smell and taste problems in adults. Laryngoscope. (2015) 125:1102–6. doi: 10.1002/lary.24999

96. Mattos JL, Schlosser RJ, DeConde AS, Hyer M, Mace JC, Smith TL, et al. Factor analysis of the questionnaire of olfactory disorders in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. (2018) 8:777–82. doi: 10.1002/alr.22112

97. Cho JH, Jeong YS, Lee YJ, Hong SC, Yoon JH, Kim JK. The Korean version of the Sniffin' stick (KVSS) test and its validity in comparison with the cross-cultural smell identification test (CC-SIT). Auris Nasus Larynx. (2009) 36:280–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2008.07.005

98. Tong JY, Wong A, Zhu D, Fastenberg JH, Tham T. The prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surgery. (2020) 163:3–11. doi: 10.1177/0194599820926473

99. Boesveldt S, Postma EM, Boak D, Welge-Luessen A, Schöpf V, Mainland JD, et al. Anosmia—a clinical review. Chem Senses. (2017) 42:513–23. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjx025

100. Landis BN, Stow NW, Lacroix J-S, Hugentobler M, Hummel T. Olfactory disorders: the patients' view. Rhinology. (2009) 47:454–9. doi: 10.4193/Rhin08.174

102. Baqui P, Bica I, Marra V, Ercole A, van Der Schaar M. Ethnic and regional variations in hospital mortality from COVID-19 in Brazil: a cross-sectional observational study. Lancet Global Health. (2020) 8, E1018–E1026. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.19.20107094

103. Golestaneh L, Neugarten J, Fisher M, Billett HH, Gil MR, Johns T, et al. The association of race and COVID-19 mortality. EClin Med. (2020) 25:100455. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100455

104. Kirby T. Evidence mounts on the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on ethnic minorities. Lancet Res Med. (2020) 8:547–8. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30228-9

105. Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. (2020) 323:2466–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598

106. Azar KMJ, Shen Z, Romanelli RJ, Lockhart SH, Smits K, Robinson S, et al. Disparities in outcomes among COVID-19 patients in a large health care system in california. Health Affairs. (2020) 39:1253–62. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00598

107. Dong J, Pinto JM, Guo X, Alonso A, Tranah G, Cauley JA, et al. The prevalence of anosmia and associated factors among US black and white older adults. J Gerontol Series A Bio Sci Med Sci. (2017) 72:1080–6. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx081

108. Cohall D, Ojeh N, Ferrario CM, Adams OP, Nunez-Smith M. Is hypertension in African-descent populations contributed to by an imbalance in the activities of the ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/Mas and the ACE/Ang II/AT1 axes? J Renin Angio Aldoster System. (2020) 21:1–7. doi: 10.1177/1470320320908186

109. Vinciguerra M, Greco E. Sars-CoV-2 and black population: ACE2 as shield or blade? Infect Genet Evol. (2020) 84:104361. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104361

110. Yuan J, Kensler KH, Hu Z, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Jiang J, et al. Integrative comparison of the genomic and transcriptomic landscape between prostate cancer patients of predominantly African or European genetic ancestry. PLoS Genet. (2020) 16:e1008641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008641

111. Bunyavanich S, Grant C, Vicencio A. Racial/ethnic variation in nasal gene expression of transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2). JAMA. (2020) 324:1567–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17386

112. Sanyaolu A, Okorie C, Marinkovic A, Patidar R, Younis K, Desai P, et al. Comorbidity and its impact on patients with COVID-19. SN Compr Clin Med. (2020) 2:1069–76. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00363-4

113. Kabarriti R, Brodin NP, Maron MI, Guha C, Kalnicki S, Garg MK, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with comorbidities and survival among patients with COVID-19 at an Urban Medical Center in New York. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2019795. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19795

114. Trivedy C, Mills I, Dhanoya O. The impact of the risk of COVID-19 on black, asian and minority ethnic (BAME) members of the UK dental profession. Bri Dental J. (2020) 228:919–22. doi: 10.1038/s41415-020-1781-6

116. Yehia BR, Winegar A, Fogel R, Fakih M, Ottenbacher A, Jesser C, et al. Association of race with mortality among patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at 92 US hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 3:e2018039. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18039

117. Muñoz-Price LS, Nattinger AB, Rivera F, Hanson R, Gmehlin CG, Perez A, et al. Racial disparities in incidence and outcomes among patients with COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. (2020) 3:e2021892. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21892

118. Lone NI, McPeake J, Stewart NI, Blayney MC, Seem RC, Donaldson L, et al. Influence of Socioeconomic Deprivation on Interventions and Outcomes for Patients Admitted With COVID-19 to Critical Care Units in Scotland: A National Cohort Study. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. (2021) 1:100005. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2020.100005

119. Kang JW, Lee YC, Han K, Kim SW, Lee KH. Epidemiology of anosmia in South Korea: a nationwide population-based study. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60678-z

120. Foster KJ, Jauregui E, Tajudeen B, Bishehsari F, Mahdavinia M. Smell loss is a prognostic factor for lower severity of coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. (2020) 125:481–3. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.07.023

121. Talavera B, García-Azorín D, Martínez-Pías E, Trigo J, Hernández-Pérez I, Valle-Peñacoba G, et al. Anosmia is associated with lower in-hospital mortality in COVID-19. J Neurol Sci. (2020) 419:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.117163

122. Lefèvre N, Corazza F, Valsamis J, Delbaere A, De Maertelaer V, Duchateau J, et al. The number of X chromosomes influences inflammatory cytokine production following toll-like receptor stimulation. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:1052. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01052

123. Hewagama A, Patel D, Yarlagadda S, Strickland FM, Richardson BC. Stronger inflammatory/cytotoxic T-cell response in women identified by microarray analysis. Genes Immunity. (2009) 10:509–16. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.12

124. Jaillon S, Berthenet K, Garlanda C. Sexual dimorphism in innate immunity. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. (2019) 56:308–21. doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8648-x

125. Marriott I, Huet-Hudson YM. Sexual dimorphism in innate immune responses to infectious organisms. Immunol Res. (2006) 34:177–92. doi: 10.1385/IR:34:3:177

126. Bwire GM. Coronavirus: why men are more vulnerable to covid-19 than women? SN Compr Clin Med. (2020) 1:874–6. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00341-w

127. Kopel J, Perisetti A, Roghani A, Aziz M, Gajendran M, Goyal H. Racial and gender-based differences in COVID-19. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:418. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00418

128. Drew DA, Nguyen LH, Steves CJ, Menni C, Freydin M, Varsavsky T, et al. Rapid implementation of mobile technology for real-time epidemiology of COVID-19. Science. (2020) 368:1362–7. doi: 10.1126/science.abc0473

129. Walker A, Hopkins C, Surda P. Use of google trends to investigate loss-of-smell–related searches during the COVID-19 outbreak. Int Forum AllerRhinol. (2020) 10:839–47. doi: 10.1002/alr.22580

130. Cherry G, Rocke J, Chu M, Liu J, Lechner M, Lund VJ, et al. Loss of smell and taste: a new marker of COVID-19? Tracking reduced sense of smell during the coronavirus pandemic using search trends. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. (2020) 18:1165–70. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2020.1792289

131. Flaxman A, Henning D, Duber H. The relative incidence of COVID-19 in healthcare workers versus non-healthcare workers: evidence from a web-based survey of facebook users in the United States [version 1; peer review: 1 approved with reservations]. Gates Open Res. (2020) 4:174. doi: 10.12688/gatesopenres.13202.1

132. Rossman H, Keshet A, Shilo S, Gavrieli A, Bauman T, Cohen O, et al. A framework for identifying regional outbreak and spread of COVID-19 from one-minute population-wide surveys. Nat Med. (2020) 26:634–8. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0857-9

133. Segal E, Zhang F, Lin X, King G, Shalem O, Shilo S, et al. Building an international consortium for tracking coronavirus health status. Nat Med. (2020) 26:1161–5. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0929-x

134. The Sex G and COVID-19 Project. The COVID-19 Sex-Disaggregated Data Tracker (2020). Available online at: https://globalhealth5050.org/covid19/ (accessed February 01, 2021).

135. CoEpi. CoEpi: Community Epidemiology in Action: CoEpi (2020). Available online at: https://www.coepi.org/ (accessed February 01, 2021).

136. Technology SUo. Beat COVID-19 Now (2020). Available online at: https://beatcovid19now.org/ (accessed February 01, 2021).

Keywords: anosmia, ageusia, olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions, COVID-19, geographical variations, socio-economic variations, ethnic variations

Citation: Kumar AA, Lee SWY, Lock C and Keong NC (2021) Geographical Variations in Host Predisposition to COVID-19 Related Anosmia, Ageusia, and Neurological Syndromes. Front. Med. 8:661359. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.661359

Received: 30 January 2021; Accepted: 29 March 2021;

Published: 29 April 2021.

Edited by:

Fabrizio Ricci, University of Studies G. d'Annunzio Chieti and Pescara, ItalyReviewed by:

Aiping Wu, Suzhou Institute of Systems Medicine (ISM), ChinaLina Palaiodimou, University General Hospital Attikon, Greece

Copyright © 2021 Kumar, Lee, Lock and Keong. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nicole CH Keong, nchkeong@cantab.net

A Aravin Kumar

A Aravin Kumar Sean Wei Yee Lee

Sean Wei Yee Lee Christine Lock

Christine Lock Nicole CH Keong

Nicole CH Keong