- 1Department of Periodical Press and National Clinical Research Center for Geriatrics, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 2West China School of Medicine, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 3Department of Medical Administration, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 4Department of Anesthesiology and National Clinical Research Center for Geriatrics, West China Hospital, Sichuan University and The Research Units of West China (2018RU012), Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Chengdu, China

- 5Department of Clinical Medicine, Gansu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Lanzhou, China

- 6Chinese Evidence-based Medicine Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 7Nursing Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, Chengdu, China

Objective: Clinical trials contribute to the development of clinical practice. However, little is known about the current status of trials on artificial intelligence (AI) conducted in emergency department and intensive care unit. The objective of the study was to provide a comprehensive analysis of registered trials in such field based on ClinicalTrials.gov.

Methods: Registered trials on AI conducted in emergency department and intensive care unit were searched on ClinicalTrials.gov up to 12th January 2021. The characteristics were analyzed using SPSS21.0 software.

Results: A total of 146 registered trials were identified, including 61 in emergency department and 85 in intensive care unit. They were registered from 2004 to 2021. Regarding locations, 58 were conducted in Europe, 58 in America, 9 in Asia, 4 in Australia, and 17 did not report locations. The enrollment of participants was from 0 to 18,000,000, with a median of 233. Universities were the primary sponsors, which accounted for 43.15%, followed by hospitals (35.62%), and industries/companies (9.59%). Regarding study designs, 85 trials were interventional trials, while 61 were observational trials. Of the 85 interventional trials, 15.29% were for diagnosis and 38.82% for treatment; of the 84 observational trials, 42 were prospective, 14 were retrospective, 2 were cross-sectional, 2 did not report clear information and 1 was unknown. Regarding the trials' results, 69 trials had been completed, while only 10 had available results on ClinicalTrials.gov.

Conclusions: Our study suggest that more AI trials are needed in emergency department and intensive care unit and sponsors are encouraged to report the results.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI), described as the science and engineering of making intelligent machines (1), is a broad term that implies the use of a computer to model intelligent behavior with minimal human intervention, generally at a speed and scale that exceed human capability (2–5). With the achievement of computer science, AI is involved in clinical practice, including tracking data (6, 7), diagnosis (8), and support of decision making (9, 10). AI has been widely used in clinical practices, such as in prediction, decision support, and the delivery of personalized health care (11–13), especially in diagnosis and treatment of acute events (14) to improve outcomes (15–17).

Emergency and critical care focus on resuscitating unstable patients and allowing time for recovery or the effect of specific therapies (18), and it can be provided in emergency department (ED) or intensive care unit (ICU) (18, 19). Emergency and critical care can be affected by levels of staffs, equipment and knowledge (18, 20). Adverse emergency and critical care will result in burdens and adverse outcomes, including weakness, dysfunction, contractures, pain, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and even death (21–23). Early and fast diagnosis could save lives. Thus, using AI tools to fastly and accurately diagnostic will help a lot (10), especially to assist in uncertainty (24) or to further developing strategies (25). Will AI tools help physicians or patients in ED and ICU (26), there is still limited information and it should be assessed by well-deigned trials.

Well-designed trials can assist clinical practice (27, 28) and transparency is the key characteristic for well-designed trials. Pre-registered in public registries is the most important strategy to ensure transparency (29) and now been required for all trials by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE). Thus, analyzing registered trials will know the progress in such field, and many studies have been published to analyze registered trials in Clinicaltrials.gov, such as acupuncture (30), ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) (31), old populations with infectious diseases (32), and cancer diagnosis (33). However, there is no such study for AI in ED and ICU. Thus, we conducted the current study to provide a comprehensive analysis of the development of AI for ED and ICU.

Materials and Methods

Reporting Guideline

This is a cross-sectional study, and it was reported according to STROBE (34).

Data Source

A cross-sectional study about registered trials for AI in ED and ICU on ClinicalTrials.gov was carried out, and the searched words were as follows: artificial intelligence, AI, computational intelligence, machine intelligence, machine learning, deep learning, algorithms, computer reasoning, computer vision system, knowledge acquisition (computer), knowledge representation (computer), natural language processing, neural networks of computer, robotics. All information was downloaded, and duplicates were removed by Excel (Office 365, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) according to the trials' national clinical trial (NCT) number.

Data Selection and Eligible Trials

We selected trials mainly according to their conditions or study descriptions. Inclusion criteria: Trials on AI and only conducted at ED and ICU. Exclusion criteria: trials not related to artificial intelligence; trials excluded conditions in the ED or ICU; trials conducted in general wards.

Studied Variables

The studied variables included study type, start year, enrollment, participant age, participant gender, status, phase, study results, sponsor, main funding source, number of funding sources, location, number of centers, primary purpose, intervention, allocation, intervention model, masking, observational model, and time perspective.

Statistical Analysis

The characteristics were analyzed by descriptive methods. The continuous variables were characterized as median and interquartile ranges (IQR), and the categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. The study types included interventional trials and observational trials. The start year was when the trial was first posted on ClinicalTrial.gov, including 2004–2010, 2011–2016, and 2017–2021. Whether the results were available or unavailable was also analyzed. The sponsor included university, hospital, industry/company, or others, including individuals, institutions, or some organizations that cannot be included in other categories. The main funding resources included industry, the federal reserve of United States (U.S. fed), or other resources, such as universities, individuals, and organizations that cannot be divided into subtypes. Data analysis was performed using SPSS21.0 software.

Results

Basic Characteristics

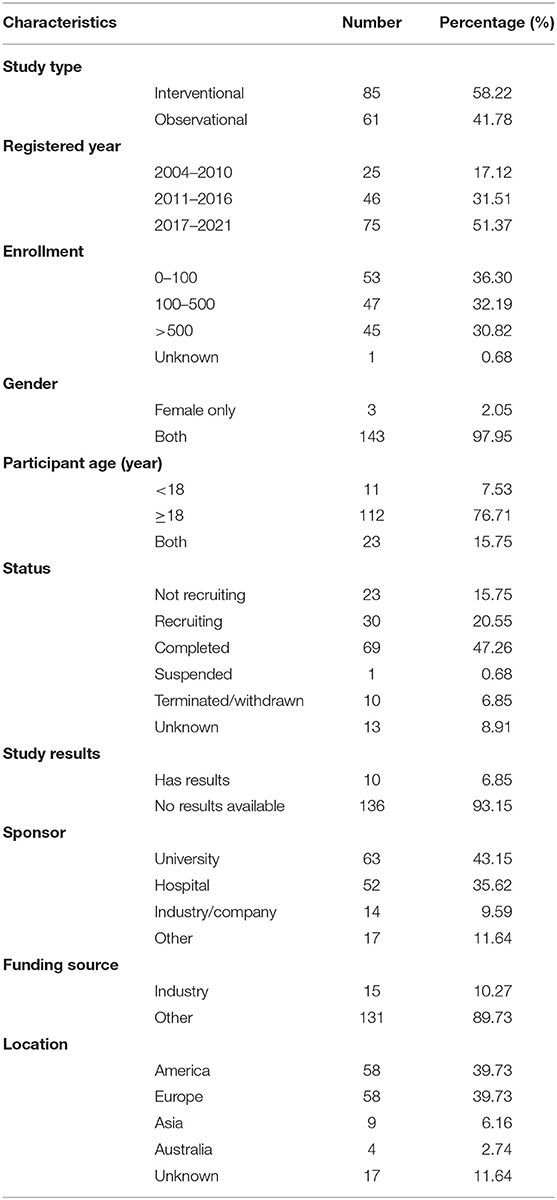

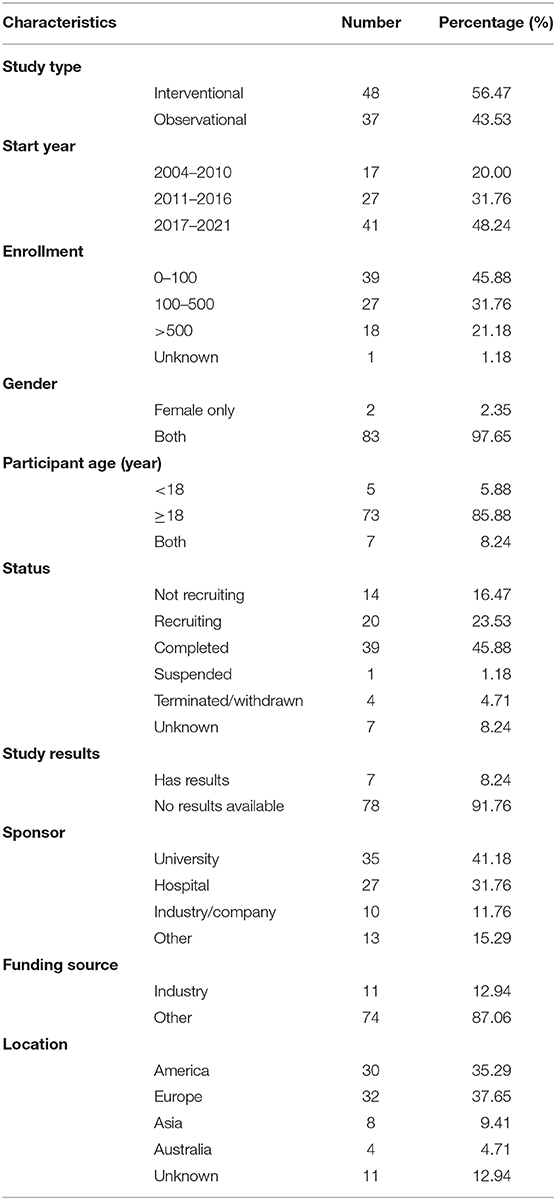

Up to 12th January 2021, 4990 trials were identified after the initial search. After reviewing all information, a total of 146 registered trials were included (Figure 1). The characteristics of the included trials are shown in Table 1. Among the 146 trials, 85 (58.22%) were interventional trials, and 61 (41.78%) were observational trials. Seventy-five (51.37%) trials registered after 2017, while 25 (17.12%) and 46 (31.51%) registered in 2004–2010 and 2011–2016, respectively. Sample sizes were from 0 to 18,000,000, with a median of 233. For genders, 143 (97.95%) trials recruited both male and female participants; however, three trials (2.05%) recruited females only. For age, 112 (76.71%) trials only recruited adults, 11 (7.53%) only recruited children, while 23 (15.75%) recruited both adults and children. For status, 23 (15.75%) trials were not yet recruiting, 30 (20.55%) were recruiting, 69 (47.26%) were completed, 1 was suspended, 10 were terminated or withdrawn and 13 were in unknown status. For results, only 10 (6.85%) trials reported results on ClinicalTrials.gov, while 136 (93.15%) did not report results. For sponsors, 63 (43.15%) were sponsored by universities, 52 (35.62%) were sponsored by hospitals, 14 (9.59%) were sponsored by industries/companies, and 17 (11.64%) were sponsored by other institutions. For funding, 15 (10.27%) were funded by industries, and 131 (89.73%) did not report clear funding sources. For locations, 58 (39.73%) trials were conducted in America, 58 (39.73%) in Europe, 9 (6.16%) in Asia, 4 (2.74%) in Australia, and 17 (11.64%) did not report locations.

Figure 1. Flowchart of recruited trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov up to 12th January 2021.

Table 1. The characteristics of the 146 trials registered on ClinicalTrial.gov.

Characteristics of Study Design

Interventional Study

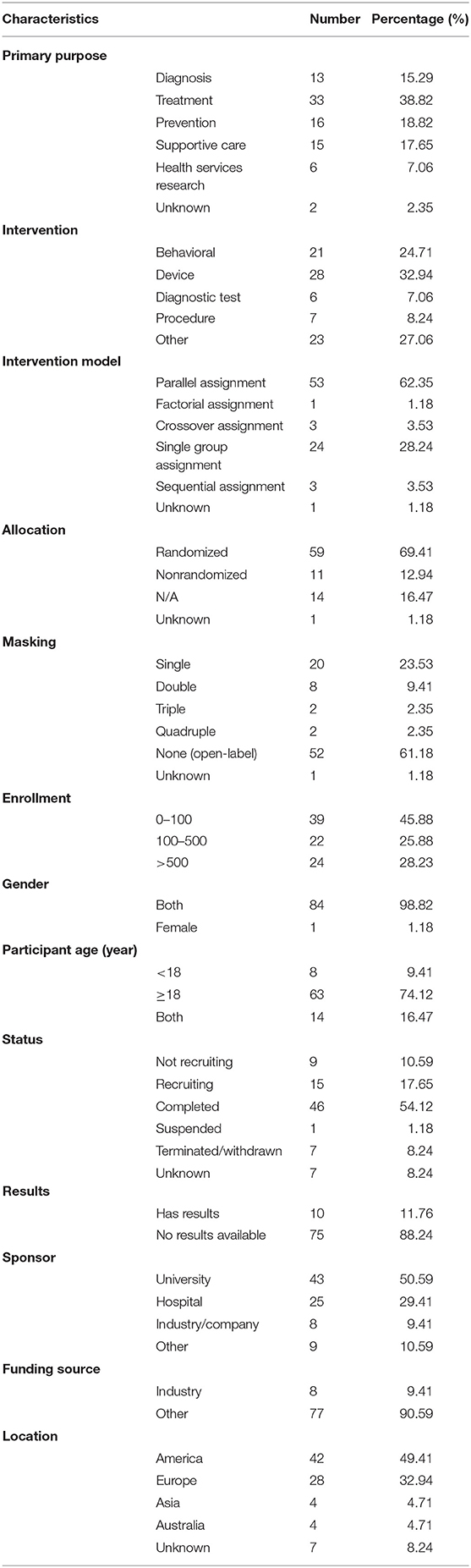

The characteristics of the 85 interventional studies are shown in Table 2. Thirteen (15.29%) trials were for diagnosis, 33 (38.82%) for treatment, 16 (18.82%) for prevention, 15 (17.65%) for supportive care, 6 (7.06%) for health services research and 2 (2.35%) did not report the clear purpose. Twety-one (24.71%) trials were for behavioral intervention, 28 (32.94%) for intervention device, 6 (7.06%) for diagnostic test, 7 (8.24%) for the procedure and 23 (27.06%) did not have clear information on intervention. For the types of assignments, 53 (62.35%) were parallel assignment, 24 (28.24%) were single group assignment, 1 (1.18%) was factorial assignment, 3(3.53%) were crossover assignment, 3(3.6%) were sequential assignment and 1(1.2%) was unknown, respectively. For allocation, 59 (69.41%) were randomized, 11 (12.94%) were nonrandomized, 14 (16.47%) were not applicable and 1 (1.18%) was unknown. For masking, 52 (61.18%) were open-labeled, 20 (23.53%) were single-masked, 8 (9.41%) were double-masked, 2(2.35%) were triple-masked, 2(2.35%) were quadruple-masked and 1 (1.18%) had no information. For sample size, 24 (28.23%) trials recruited more than 500 participants, while 39 (45.88%) recruited <100 participants and 22 (25.88%) recruited 100–500 participants. For gender, 1 (1.18%) trial included female only and 84 (98.82%) recruited both male and female. For age, 63 (74.12%) trials recruited adult only, while 8 (9.41%) trials recruited child only and 14 (16.47%) trials recruited both child and adult. One (1.18%) trial was in phase 2, 1 (1.18%) in phase 2/3, 3(3.53%) in phase 3, 1 (1.18%) in phase 4 and 79 had no clear information. For status, 46 (54.12%) trials were completed, 15 (17.65%) were recruiting, 9 (10.59%) were not recruiting, 7 (8.24%) were terminated or withdrawn, 1 (1.18%) was suspended and 7 (8.24%) had no information. Among all 85 interventional trials, only 10 trials reported results on Clinicaltrials.gov. For sponsors, 43 (50.59%) were sponsored by universities, 25 (29.41%) were sponsored by hospitals, 8 (9.41%) were sponsored by industries/companies, and 9 (10.59) were sponsored by other institutions. For funding, 8 (9.41%) trials were funded by industries and 77 (90.59%) did not report funding sources. For locations, 42 (49.41%) were from America, 28 (32.94%) were from Europe, 4 (4.71%) were from Asia, 4 (4.71%) were from Australia and 7 (8.24%) did not report location information.

Table 2. Designs of 85 interventional trials registered with ClinicalTrial.gov.

Observational Study

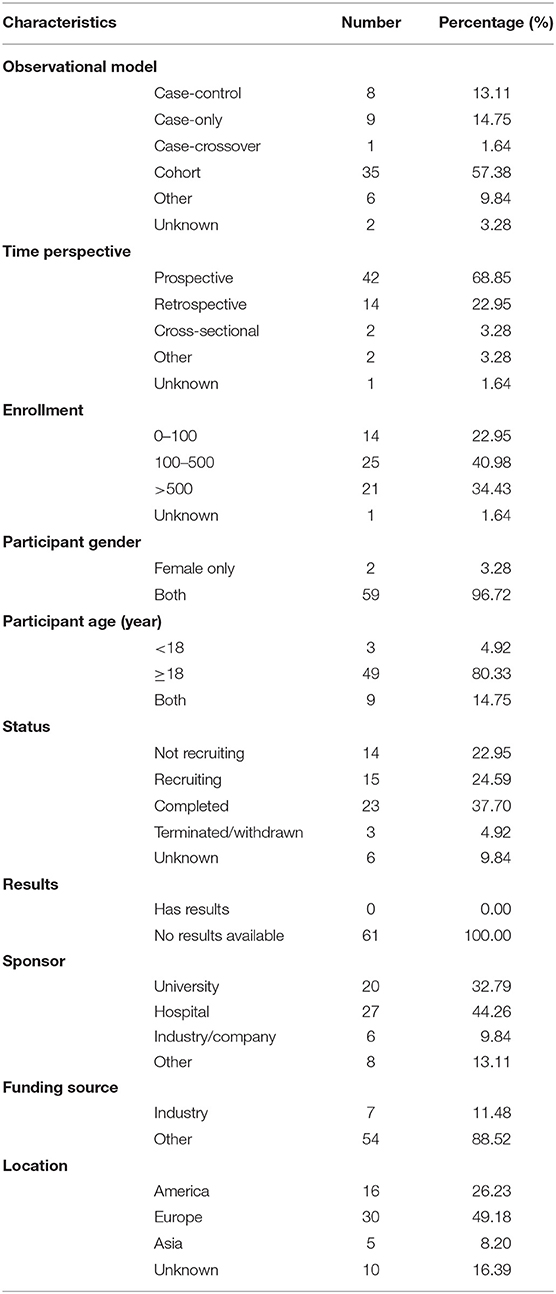

The characteristics of the 61 observational studies are shown in Table 3. Among them, 35 (57.38%) were cohort studies, 9 (14.75%) were case-only studies, 8 (13.11%) were case-control studies and one was case-crossover study, while 6 (9.84%) had no clear information and 2 (3.28%) did not provide information. Forty-two (68.85%) were prospective studies, 14 (22.95%) were retrospective studies, 2 (3.28%) were cross-sectional studies, 2 (3.28%) were other designed studies and one did not report related information. For sample size, 21 (34.43%) recruited more than 500 participants, while 14 (22.95%) recruited <100 participants and 25 (40.98%) recruited 100–500 participants. For gender, only 2 studies included female only and 59 (96.72%) recruited both male and female. For age, 49 (80.33%) recruited adult only, while 3 (4.92%) recruited child only and 9 (14.75%) recruited both child and adult. For status, 23 (37.70%) were completed, 15 (24.59%) were recruiting, 14 (22.95%) were not recruiting, 3 (4.92%) were terminated or withdrawn and 6 (9.84%) had no information. Among all 61 observational studies, none of them reported results on Clinicaltrials.gov. For sponsors, 20 (32.79%) were sponsored by universities, 27 (44.26%) were sponsored by hospitals, 6 (9.84%) were sponsored by industries/companies, and 8 (13.11%) were sponsored by other institutions. For funding, 7 (11.48%) were funded by industries, and 54 (88.52%) did not report clear funding sources. For locations, 30 (49.18%) were from Europe, 16 (26.23%) were from America, 5 (8.20%) were from Asia and 10 (16.39%) did not report locations.

Table 3. Designs of 61 observational trials registered on ClinicalTrial.gov.

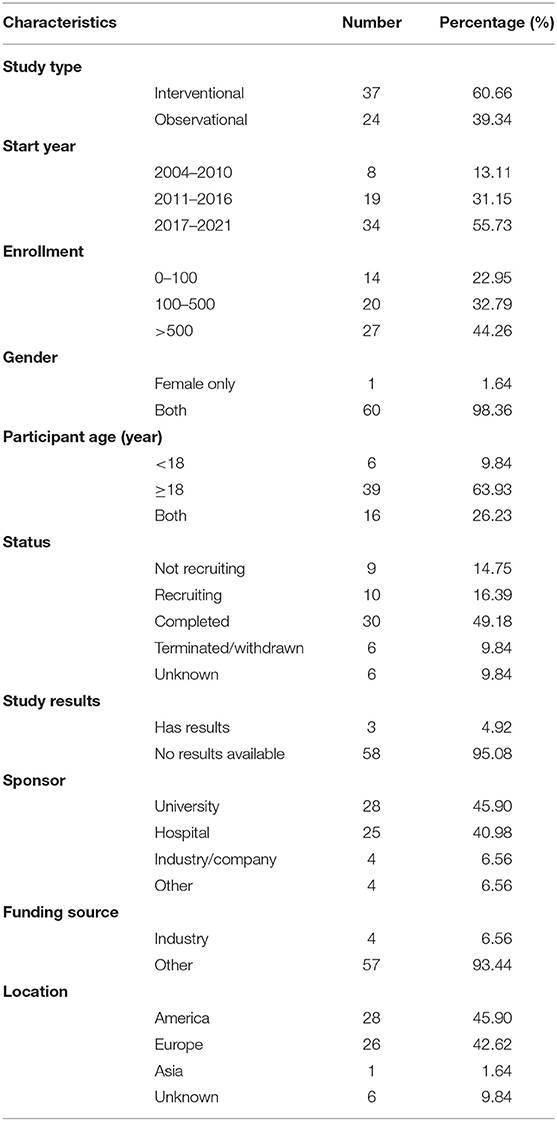

Characteristics of Trials at Emergency Department

Table 4 shows the characteristics of trials conducted in ED. Among the 61 trials, 37 (60.66%) were interventional trials, and 24 (39.34%) were observational trials. Thirty-four (55.73%) trials registered after 2017, while 8 (13.11%) and 19 (31.15%) were registered in 2004–2010 and 2011–2016, respectively. For sample size, 27 (44.26%) trials recruited more than 500 participants, while 14 (22.95%) recruited <100 participants and 20 (32.79%) recruited 100 to 500 participants. For genders, 60 trials (98.36%) recruited both male and female participants; however, 1 (1.64%) recruited females only. For age, 39 trials (63.93%) only recruited adults, 6 (9.84%) only recruited children, while 16 (26.23%) recruited both adults and children. For status, 9 (14.75%) were not yet recruiting, 10 (16.39%) were recruiting, 30 (49.18%) were completed, six were terminated or withdrawn and six were in unknown status. For results, only three trials reported results on Clinicaltrials.gov, while 58 (95.08%) did not report results. For sponsors, 28 (45.90%) were sponsored by universities, 25 (40.98%) were sponsored by hospitals, 4 (6.56%) were sponsored by industries/companies, and 4 (6.56%) were sponsored by other institutions. For funding, 4 trials (6.56%) were funded by industries and 57 (93.44%) did not report clear funding sources. For locations, 28 (45.90%) were in America, 26 (42.62%) in Europe, 1 (1.64%) in Asia and 6 (9.84%) did not report locations.

Table 4. The characteristics of the 61 trials in ED registered on ClinicalTrial.gov.

Characteristics of Trials at ICU

Table 5 shows the characteristics of trials on AI conducted in emergency department. Among the 85 trials, 48 (56.47%) were interventional trials, and 37 (43.53%) were observational trials. Forty-one (48.24%) trials registered after 2017, while 17 (20.00%) and 27 (31.76%) registered in 2004–2010 and 2011–2016, respectively. For sample size, 18 (21.18%) trials recruited more than 500 participants, 39 (45.88%) recruited <100 participants, 27 (31.76%) recruited 100–500 participants and 1 was unknown. For genders, 83 trials (97.65%) recruited both male and female participants; however, 2 (2.35%) trials recruited females only. For age, 73 trials (85.88%) only recruited adults, 5 (5.88%) trials only recruited children, while 7 (8.24%) recruited both adults and children. For status, 14 (16.47%) were not yet recruiting, 20 (23.53%) were recruiting, 39 (45.88%) were completed, while one was suspended, four were terminated or withdrawn and seven were in unknown status. For results, only seven trials reported results on Clinicaltrials.gov, while 78 (91.76%) did not report results. For sponsors, 35 (41.18%) trials were sponsored by universities, 27 (31.76%) were sponsored by hospitals, 10 (11.76%) were sponsored by industries/companies, and 13 (15.29%) were sponsored by other institutions. For funding, 11 trials (12.94%) were funded by industries and 74 (87.06%) did not report clear funding sources. For locations, 30 (35.29%) were in America, 32 (37.65%) were in Europe, 8 (9.41%) in Asia, 4 (4.71%) in Australia and 11 (12.94%) did not report locations.

Table 5. The characteristics of the 85 trials in ICU registered on ClinicalTrial.gov.

Discussion

Clinical trials have played important roles in changing clinical practice (19, 35, 36). Analyzing registered trials could provide a comprehensive analysis of progress in a specific field; thus, numerous studies have been published to analyze registered trials on Clinicaltrials.gov. Considering AI is important tool and have been applied in ED and ICU, we performed the current study to analyze registered trials on AI conducted in ED and ICU.

A total of 146 registered trials were identified, including 61 trials in ED and 85 in ICU, which is similar with our previous study for cancer (33). Over half trials registered after 2017, and it was consistent with the development of industry 4.0, which depended on AI to empower medicine (37). Research in children was often challenging due to scientific, ethical, and practical factors, so only 23.29% trials enrolled children, and 17% enrolled children from 2007 to 2010 (38). More work is needed to ensure that children are equally involved in trials on AI in ED and ICU. In our study, most registered trials included relatively large samples, which would help to reduce the potential risk of statistical error (39). It is interesting to know that no trials were funded by NIH, which did not mean NIH did not fund trials in such field, because academic institutions/medical centers might have been funded by NIH to perform the trials, and they did not report it clearly in the website of Clinicaltrials.gov (30).

Reporting trials' results is very important. In our study, 47.26% trials had been completed, but only 6.85% reported results on ClinicalTrials.gov, suggesting a lack of transparency (40). Although the completion rate was higher than all trials from 2007 to 2010 (38), but reported results was significantly lower than other study (31). The possible explanation might be positive results were submitted more rapidly after completion, and studies sponsored by industries or companies were not likely to report negative results (41, 42). As a public registry platform, ClinicalTrials.gov is expected to make research more transparent and to reduce reporting bias, and sponsors are encouraged to publish their outcomes on ClinicalTrials.gov with no delay (31). Feasibility, lacking funding, unforeseen issues, poor recruitment and change project will also affect the progress of trials. In our study, 6.85% trials were suspended, terminated, or withdrawn, which was not high than previous study (38), suggesting supporting are good for such field.

In our study, a total of 37.64% trials were blinded, and 61.18% were open-labeled, the results were lower than all trials in Clinicaltrials.gov from 2007 to 2010 (38). Randomization is a hallmark of trials, and randomization with blinding can help reduce bias (43). Most trials were observational designs. Observational studies are subjected to a number of potential problems that might cause bias in the results; however, the main methodological issues can be avoided by using specific study designs (44). Therefore, more well-designed trials on AI in ED and ICU are needed to help the progress of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of emergency and critical illness.

Trials increased a lot in the past several years. With the assistant of AI, the management of patients in ED and ICU will be greatly improved (45). In spite of advantages, we found some deficiencies of trials in this field, such as lack of results reporting, clear information losing and short of trials quantities. Thus, more efforts are needed to help registered trials in this field.

The limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, ClinicalTrials.gov does not include all trials because some investigators and sponsors may register on other registry platforms. Secondly, our study provided only the characteristics of the registered trials. The actual strengths and weaknesses of the trials were not assessed, and some missing data may bring bias to this study. Thirdly, we did not check whether the registered trials have been published in journals. These results should be analyzed in future.

In conclusion, the current study is the first study to study registered AI trilas in ED and ICU, more trials are needed and sponsors are encouraged to report the results.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

YZ and NL visualized the presented idea and supervised the project, YZ and GL contributed to manuscript writing, GL and YZ contributed to trial searches and preparing the manuscript draft, NL, LC, and YY revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The study was supported by Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology (Nos. 20GJHZ0222, 2020YFS0186).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The paper has been carefully revised by native English speakers and scientific editors of Enliven LLC to improve grammar and readability.

References

1. Hamet P, Tremblay J. Artificial intelligence in medicine. Metab Clin Exp. (2017) 69s:S36–s40. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2017.01.011

2. Maddox TM, Rumsfeld JS, Payne PRO. Questions for artificial intelligence in health care. JAMA. (2019) 321:31–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.18932

3. Miller DD, Brown EW. Artificial intelligence in medical practice: the question to the answer? Am J Med. (2018) 131:129–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.10.035

4. Goldhahn J, Rampton V, Spinas GA. Could artificial intelligence make doctors obsolete? BMJ (Clinical research ed). (2018) 363:k4563. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4563

5. Rampton V. Artificial intelligence versus clinicians. BMJ (Clinical research ed). (2020) 369:m1326. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1326

6. Vaishya R, Javaid M, Khan IH, Haleem A. Artificial Intelligence (AI) applications for COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab Syndrome. (2020) 14:337–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.012

7. Schwalbe N, Wahl B. Artificial intelligence and the future of global health. Lancet. (2020) 395:1579–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30226-9

8. Bi WL, Hosny A, Schabath MB, Giger ML, Birkbak NJ, Mehrtash A, et al. Artificial intelligence in cancer imaging: clinical challenges and applications. CA Cancer J Clin. (2019) 69:127–57. doi: 10.3322/caac.21552

9. Stead WW. Clinical implications and challenges of artificial intelligence and deep learning. JAMA. (2018) 320:1107–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.11029

10. Liang H, Tsui BY, Ni H, Valentim CCS, Baxter SL, Liu G, et al. Evaluation and accurate diagnoses of pediatric diseases using artificial intelligence. Nat Med. (2019) 25:433–8. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0335-9

11. Abbasi J. Artificial intelligence tools for sepsis and cancer. JAMA. (2018) 320:2303. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19383

12. Knaus WA, Marks RD. New phenotypes for sepsis: the promise and problem of applying machine learning and artificial intelligence in clinical research. JAMA. (2019) 321:1981–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.5794

13. Matheny ME, Whicher D, Thadaney Israni S. artificial intelligence in health care: a report from the national academy of medicine. JAMA. (2020) 323:509–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21579

14. Zhang Z, Navarese EP, Zheng B, Meng Q, Liu N, Ge H, et al. Analytics with artificial intelligence to advance the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Evid Based Med. (2020) 13:301–12. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12418

15. Lynch CJ, Liston C. New machine-learning technologies for computer-aided diagnosis. Nat Med. (2018) 24:1304–5. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0178-4

16. Goto S, Kimura M, Katsumata Y, Goto S, Kamatani T, Ichihara G, et al. Artificial intelligence to predict needs for urgent revascularization from 12-leads electrocardiography in emergency patients. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0210103. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210103

17. Mao Q, Jay M, Hoffman JL, Calvert J, Barton C, Shimabukuro D, et al. Multicentre validation of a sepsis prediction algorithm using only vital sign data in the emergency department, general ward and ICU. BMJ open. (2018) 8:e017833. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017833

18. Schell CO, Gerdin Wärnberg M, Hvarfner A, Höög A, Baker U, Castegren M, et al. The global need for essential emergency and critical care. Crit Care (London, England). (2018) 22:284. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2219-2

19. Vincent JL. Critical care–where have we been and where are we going? Critical Care (London, England). (2013) 17(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/cc11500

20. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. (2016) 315:801–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287

21. Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD. Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults. Lancet. (2010) 376:1339–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60446-1

22. Hensley MK, Prescott HC. Bad brains, bad outcomes: acute neurologic dysfunction and late death after sepsis. Crit Care Med. (2018) 46:1001–2. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003097

23. Vincent JL, Marshall JC, Namendys-Silva SA, François B, Martin-Loeches I, Lipman J, et al. Assessment of the worldwide burden of critical illness: the intensive care over nations (ICON) audit. Lancet Respir Med. (2014) 2:380–6. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70061-X

24. Patel VL, Shortliffe EH, Stefanelli M, Szolovits P, Berthold MR, Bellazzi R, et al. The coming of age of artificial intelligence in medicine. Artif Intell Med. (2009) 46:5–17. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2008.07.017

25. Loftus TJ, Tighe PJ, Filiberto AC, Efron PA, Brakenridge SC, Mohr AM, et al. Artificial intelligence and surgical decision-making. JAMA Surg. (2020) 155:148–58. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.4917

26. Sanchez-Pinto LN, Luo Y, Churpek MM. Big data and data science in critical care. Chest. (2018) 154:1239–48. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.04.037

27. Faraoni D, Schaefer ST. Randomized controlled trials vs. observational studies: why not just live together? BMC Anesthesiol. (2016) 16:102. doi: 10.1186/s12871-016-0265-3

28. Feizabadi M, Fahimnia F, Mosavi Jarrahi A, Naghshineh N, Tofighi S. Iranian clinical trials: an analysis of registered trials in International Clinical Trial Registry Platform (ICTRP). J Evid Based Med. (2017) 10:91–6. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12248

29. DeAngelis CD, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, Haug C, Hoey J, Horton R, et al. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. (2005) 131:479–80. doi: 10.1001/archotol.131.6.479

30. Chen J, Huang J, Li JV, Lv Y, He Y, Zheng Q. The Characteristics of TCM Clinical Trials: a systematic review of ClinicalTrials.gov. Evid Based Complem Altern Med. (2017) 2017:9461415. doi: 10.1155/2017/9461415

31. Chen L, Su Y, Quan L, Zhang Y, Du L. Clinical trials focusing on drug control and prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a comprehensive analysis of trials registered on ClinicalTrials.gov. Front Pharmacol. (2018) 9:1574. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01574

32. Chen L, Wang M, Yang Y, Shen J, Zhang Y. Registered interventional clinical trials for old populations with infectious diseases on ClinicalTrials.gov: a cross-sectional study. Front Pharmacol. (2020) 11:942. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00942

33. Dong J, Geng Y, Lu D, Li B, Tian L, Lin D, et al. Clinical trials for artificial intelligence in cancer diagnosis: a cross-sectional study of registered trials in ClinicalTrials.gov. Front Oncol. (2020) 10:1629. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01629

34. Yao X, Florez ID, Zhang P, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Wang C, et al. Clinical research methods for treatment, diagnosis, prognosis, etiology, screening, and prevention: a narrative review. J Evid Based Med. (2020) 13:130–6. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12384

35. Tiguman GMB. Characteristics of Brazilian clinical studies registered in ClinicalTrials.gov between 2010 and 2020. J Evid Based Med. (2020) 13:261–4. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12415

36. Heredia P, Alarcon-Ruiz CA, Roque-Roque JS, De La Cruz-Vargas JA, Quispe AM. Publication and associated factors of clinical trials registered in Peru. J Evid Based Med. (2020) 13:284–91. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12413

37. Jha S, Topol EJ. Adapting to artificial intelligence: radiologists and pathologists as information specialists. JAMA. (2016) 316:2353–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17438

38. Califf RM, Zarin DA, Kramer JM, Sherman RE, Aberle LH, Tasneem A. Characteristics of clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, 2007-2010. Jama. (2012) 307:1838–47. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3424

39. Inrig JK, Califf RM, Tasneem A, Vegunta RK, Molina C, Stanifer JW, et al. The landscape of clinical trials in nephrology: a systematic review of Clinicaltrials.gov. Am J Kidney Dis. (2014) 63:771–80. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.10.043

40. Roberto A, Radrezza S, Mosconi P. Transparency in ovarian cancer clinical trial results: ClinicalTrials.gov versus PubMed, Embase and Google scholar. J Ovarian Res. (2018) 11:28. doi: 10.1186/s13048-018-0404-1

41. Ioannidis JP. Effect of the statistical significance of results on the time to completion and publication of randomized efficacy trials. JAMA. (1998) 279:281–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.4.281

42. Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, Schroll JB, Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2017) 2:Mr000033. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub3

43. Berger VW, Alperson SY. A general framework for the evaluation of clinical trial quality. Rev Recent Clin Trials. (2009) 4:79–88. doi: 10.2174/157488709788186021

44. Hammer GP, du Prel JB, Blettner M. Avoiding bias in observational studies: part 8 in a series of articles on evaluation of scientific publications. Dtsch Arztebl Int. (2009) 106:664–8. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0664

Keywords: artificial intelligence, emergency department, intensive care unit, ClinicalTrials.gov, cross-sectional, trial

Citation: Liu G, Li N, Chen L, Yang Y and Zhang Y (2021) Registered Trials on Artificial Intelligence Conducted in Emergency Department and Intensive Care Unit: A Cross-Sectional Study on ClinicalTrials.gov. Front. Med. 8:634197. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.634197

Received: 27 November 2020; Accepted: 19 February 2021;

Published: 24 March 2021.

Edited by:

Zhongheng Zhang, Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, ChinaReviewed by:

Qilin Yang, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, ChinaYingli He, Xi'an Jiaotong University, China

Copyright © 2021 Liu, Li, Chen, Yang and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nian Li, bGluaWFuQHdjaHNjdS5jbg==; Yonggang Zhang, amVibV96aGFuZ0B5YWhvby5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Guina Liu

Guina Liu Nian Li

Nian Li Lingmin Chen4

Lingmin Chen4 Yi Yang

Yi Yang Yonggang Zhang

Yonggang Zhang