- Division of Infectious Diseases and Vaccinology, School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States

Background: Drug-resistance genes found in human bacterial pathogens are increasingly recognized in saprophytic Gram-negative bacteria (GNB) from environmental sources. The clinical implication of such environmental GNBs is unknown.

Objectives: We conducted a systematic review to determine how often such saprophytic GNBs cause human infections.

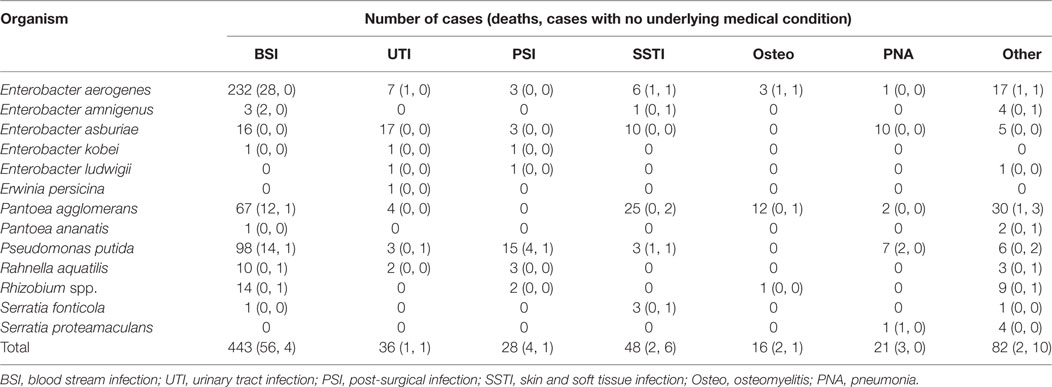

Methods: We queried PubMed for articles published in English, Spanish, and French between January 2006 and July 2014 for 20 common environmental saprophytic GNB species, using search terms “infections,” “human infections,” “hospital infection.” We analyzed 251 of 1,275 non-duplicate publications that satisfied our selection criteria. Saprophytes implicated in blood stream infection (BSI), urinary tract infection (UTI), skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI), post-surgical infection (PSI), osteomyelitis (Osteo), and pneumonia (PNA) were quantitatively assessed.

Results: Thirteen of the 20 queried GNB saprophytic species were implicated in 674 distinct infection episodes from 45 countries. The most common species included Enterobacter aerogenes, Pantoea agglomerans, and Pseudomonas putida. Of these infections, 443 (66%) had BSI, 48 (7%) had SSTI, 36 (5%) had UTI, 28 (4%) had PSI, 21 (3%) had PNA, 16 (3%) had Osteo, and 82 (12%) had other infections. Nearly all infections occurred in subjects with comorbidities. Resistant strains harbored extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL), carbapenemase, and metallo-β-lactamase genes recognized in human pathogens.

Conclusion: These observations show that saprophytic GNB organisms that harbor recognized drug-resistance genes cause a wide spectrum of infections, especially as opportunistic pathogens. Such GNB saprophytes may become increasingly more common in healthcare settings, as has already been observed with other environmental GNBs such as Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Introduction

In 2013, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a report “Antibiotic Resistance in the United States, 2013” that classified groups of drug-resistant microorganisms into “urgent threat,” “serious threat,” and “concerning threat” pathogens (1). Drug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial (GNB) pathogens comprised 2 of the 3 “urgent threat” pathogens and 7 of 12 “serious threat” pathogens (1). GNBs cause about one-third of healthcare-associated (HCA) infections in the United States, and the proportion of multidrug-resistant and non-fermentative organisms (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii) causing these infections has increased dramatically in the last 20 years, according to the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) surveys (2). While still relatively low in most hospitals in the United States, multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, an environmental saprophyte, has become endemic in healthcare settings in several Latin American countries, and has surpassed P. aeruginosa as the most common non-fermentative GNB in such settings (3). The progressive increase in drug resistance and new species of GNBs causing HCA infections may represent an evolution in drug-resistant GNB infections that may profoundly affect the future landscape of epidemiology and clinical management of such infections in the healthcare environment globally.

Most of the new antimicrobial drug-resistance mechanisms discovered during the last 20 years have been those found in GNBs (4–11). In 2011, Raphael et al. reported identification of a variety of saprophytic GNB species on retail spinach that were resistant to antimicrobial agents commonly used in clinical settings (12). Twelve of 20 species found on spinach expressed extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), based on their resistance to ceftazidime and cefotaxime (12). Two strains of Pseudomonas putida and one strain of Pseudomonas teessidea contained blaCTX-M-15, the most common ESBL gene distributed globally and carried frequently by the most common pandemic extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) lineage ST131 (13–17). They suggested that environmental saprophytes may serve as a reservoir for some of the common drug-resistance genes found in human GNB pathogens (12).

Saprophytes are environmental microorganisms that survive on dead organic matter. While no pathogenic GNB organisms were found on spinach in the above study, we were concerned that a large proportion of these saprophytic organisms were drug resistant. We wished to know whether saprophytic GNBs that carry recognized drug-resistance genes cause human infections. After all, pathogenic GNBs, such as K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter spp., are environmental GNB organisms. Here, we conducted a systematic bibliographic search of human infections caused by well-recognized environmental saprophytic GNB species. We present our review results and suggest that these saprophytic GNB may represent a harbinger of the next phase of the evolution of GNB infections, especially in healthcare settings.

Methods

Data Sources and Searches

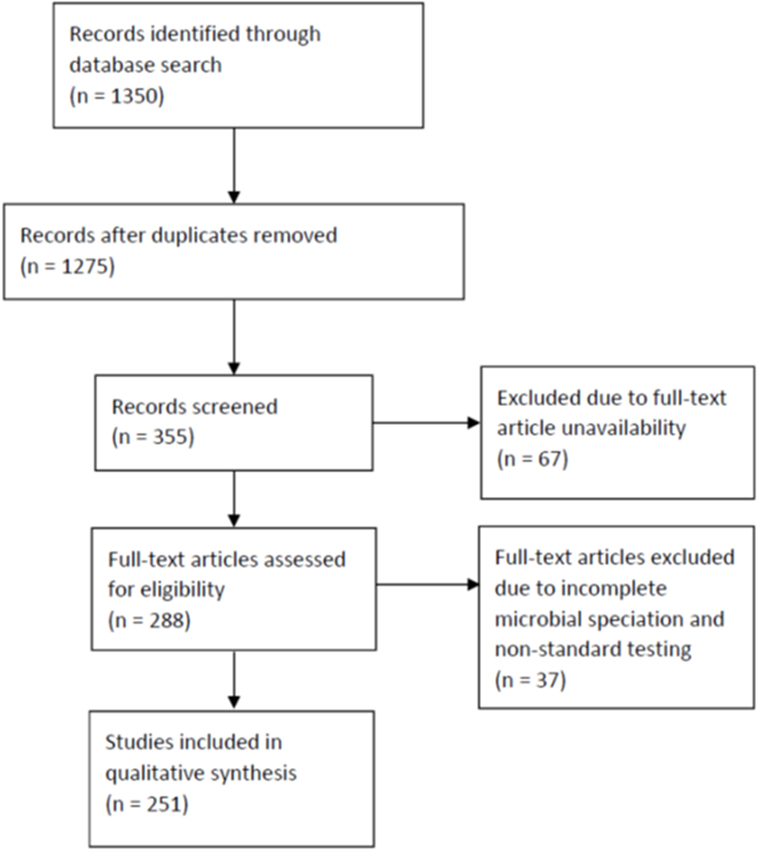

We followed the guideline outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) to conduct this review (Figure 1). Using the names of GNB species listed in Table 1 as search terms, we queried PubMed for abstracts and full-length articles that were published in English, French, and Spanish between January 2006 and July 2014. The selected GNB species were based on those frequently found on retail spinach in a previous report (1). If more than 200 articles appeared for one species, the term “infections” was added to the search. In certain cases, the term “human infections” or “hospital infection” was added. If an organism was not reported as a cause of human infection after 2006, the search was widened to include articles published before 2006.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram for searched articles.

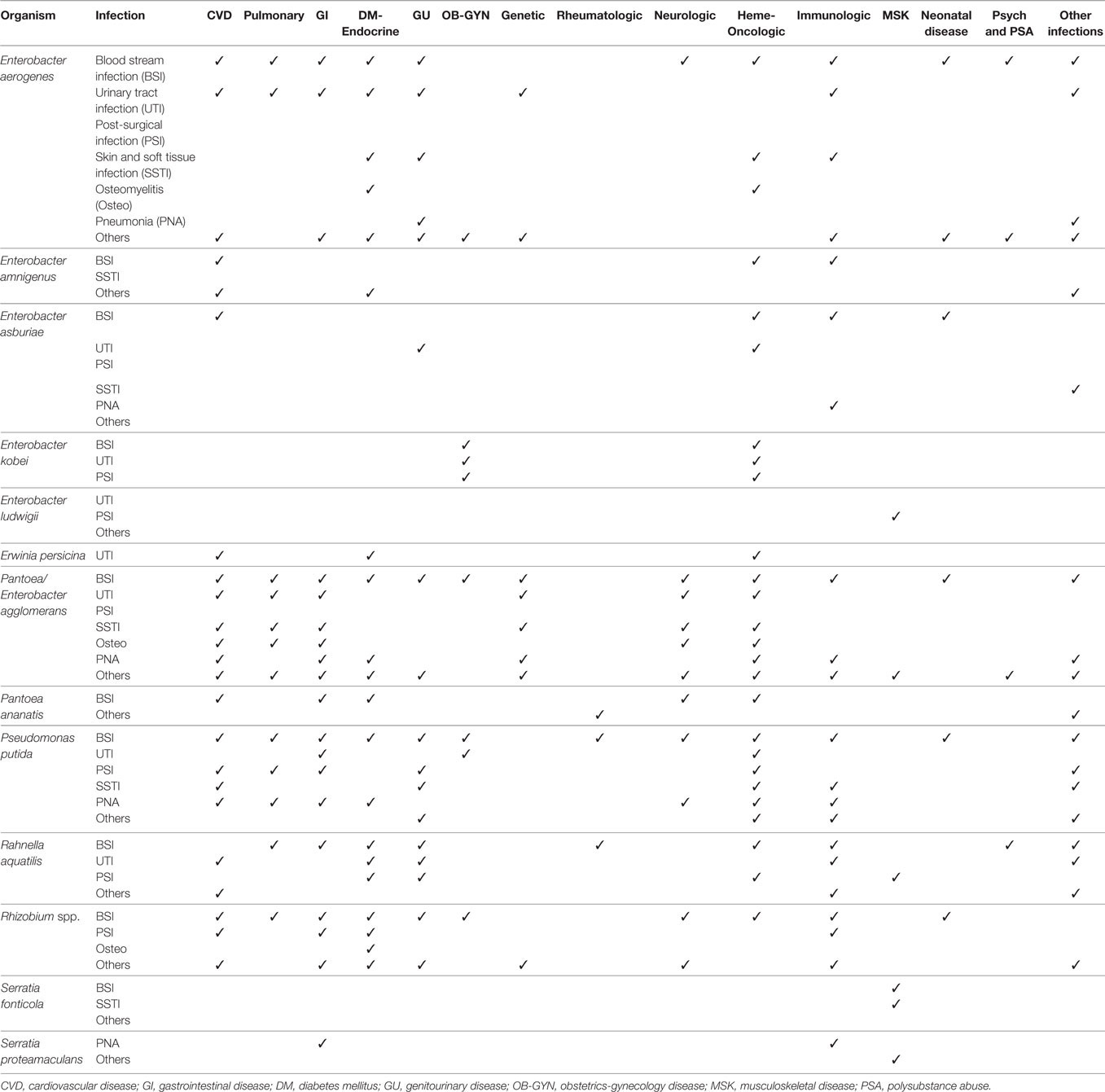

Table 1. Case reports and hospital microbiological surveys reporting infections caused by saprophytic Gram-negative bacteria (GNB) species previously identified on retail spinach [Raphael et al (12)].

Study Selection

We first identified 1,350 abstracts. After duplicates were removed, we reviewed 1,275 abstracts (Figure 1). We excluded for analysis abstracts, as well as reviews and microbiology papers that did not include human clinical data, or articles that described only episodes of colonization, laboratory contamination, or pseudo-infection (e.g., line or catheter contamination). Full-text articles were not available for 67 of these abstracts. We identified 355 abstracts after exclusion and obtained full-text articles for 288 of them. Of the full-text articles, 37 were excluded further due to incomplete GNB speciation and non-standard microbiologic test procedures reported in the articles. We, thus, included 251 articles for this review (18–76, 78–103, 105–245, 247–246); of these, 124 were case series reports and 127 were hospital microbiologic survey reports.

Data Extraction

We analyzed the selected articles for the GNB species implicated as causative agents of infections that were most commonly reported among the articles—blood stream infection (BSI), urinary tract infection (UTI), skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI), post-surgical infection (PSI), osteomyelitis (Osteo), and pneumonia (PNA). Other reported infections were grouped under the “other” category. The reports were also reviewed for descriptions of mortality, comorbidity, as well as healthcare interventions associated with the above infectious disease episodes. Finally, we reviewed microbiologic reports that accompanied these articles for drug-susceptibility test results as well as genetic analyses of drug-resistance determinants.

Quality Assessment

To assure search completeness and reproducibility of our findings, we conducted the same search described above on three different occasions—in 2011, 2013, and 2015. We included articles only from peer-reviewed journals. We reviewed in detail the descriptions of microbiologic test procedures used to detect and identify the implicated GNB species. We also examined the descriptions of drug-susceptibility test procedures to ascertain their standardization. Both authors ER and LR independently reviewed the quantitative data analysis results obtained from examination of these 251 articles.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

We first quantified the type and number of GNB species implicated in infections reported in the 251 selected articles. We then examined the frequencies of GNB species associated with the six most common infections described in the articles, separated by case series and hospital survey studies, reported from different regions of the world. We compared mortality and comorbidities associated with each of these infections and assessed unusual events that were described to trigger these infectious disease episodes. We then analyzed the microbiologic data, which included antimicrobial drug-susceptibility test results and PCR-based and nucleic acid sequence-based detection of drug-resistance genes.

Results

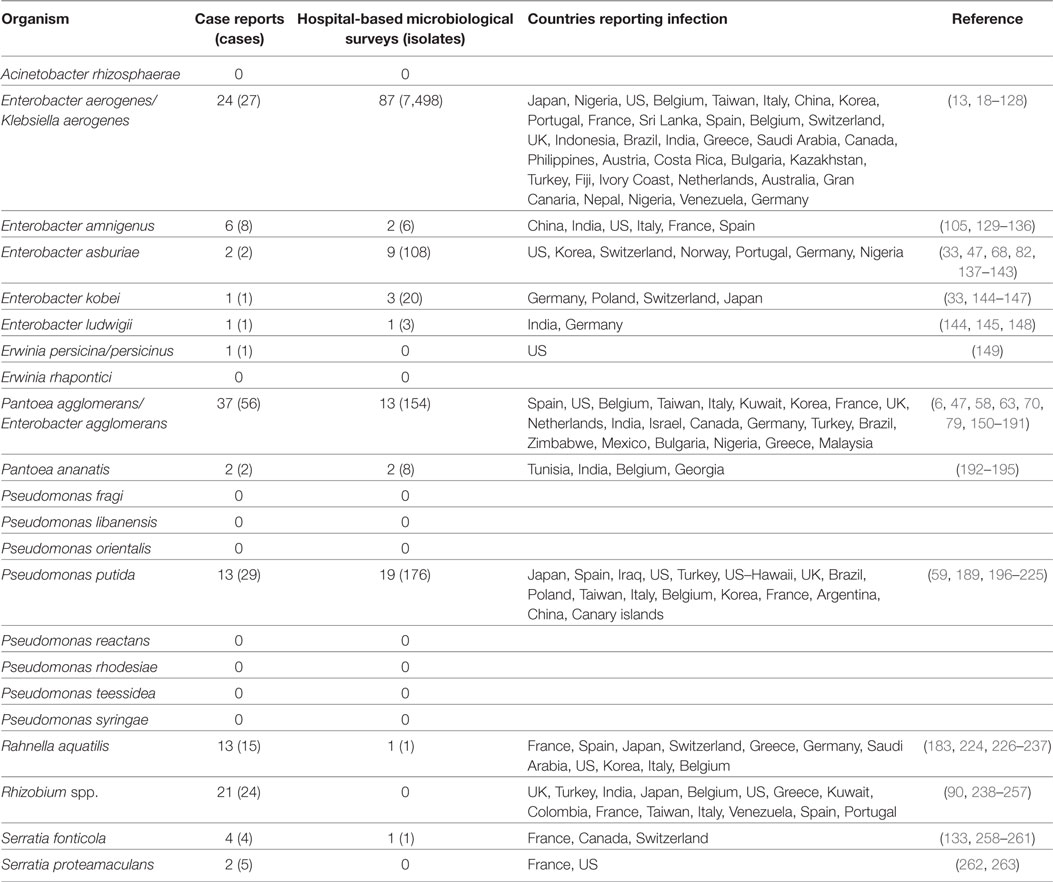

A previous study identified 20 distinct saprophytic GNB species among 231 randomly selected colonies cultured on MacConkey agar plates from 25 batches of retail spinach rinsates (12). Here, these 20 species were queried in the bibliographic search engines. Thirteen of these species were reported to cause human infections in the reviewed literature (Table 1). We identified 175 cases described in 124 separate case report series. From 127 hospital microbiology surveys, 7,671 isolates from infected subjects were reported. These infections were reported from 48 countries. The most commonly reported GNB species was Enterobacter aerogenes. E. aerogenes together with Pantoea agglomerans (formerly Enterobacter agglomerans) and Pseudomonas putida together comprised more than half of the reported cases of infection caused by these saprophytic GNBs.

The most commonly isolated GNB species reported from 127 hospital-based microbiologic surveys was also Enterobacter aerogenes; 7,498 E. aerogenes isolates from 87 separate hospital surveys were reported (Table 1). In both case series and hospital survey reports, the most common GNB species were identical—E. aerogenes, P. putida, P. agglomerans, and E. asburiae.

The bibliographic search identified 674 individuals who were diagnosed with infection caused by the 13 GNB species. These saprophytes caused a wide spectrum of infections (Table 2). They were isolated from 443 patients with BSI, 48 patients with SSTI, 36 patients with UTI, 28 patients with PSI, 21 patients with PNA, 16 patients with Osteo, and 82 with other infections. In addition to blood, urine, skin and soft tissue, surgical wounds, bone, and lungs, these GNB species were isolated from many other body sites such as the peritoneum, eyes, and the central nervous system (Table S1 in Supplemental Material).

The most frequently isolated GNB species cultured from blood were E. aerogenes (232 cases), P. putida (98 cases), and P. agglomerans (67 cases). They were responsible for 89% of the BSI cases caused by the 13 saprophytic GNB species. Mortality from BSI associated with these organisms was 12, 14, and 18%, respectively. All of the patients with BSI, except 4, had comorbidities or underlying medical problems (Table 3 and supplemental table). The most common comorbidities associated with E. aerogenes BSI were cancer (35 cases), biliary disease (21 cases), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (10 cases), premature birth (10 cases), and diabetes (9 cases). Many of these patients had an invasive procedure, chemotherapy, or immunosuppressive drugs within 14 days of the bacteremia. Of these BSI cases, 49 were reported as nosocomial infections.

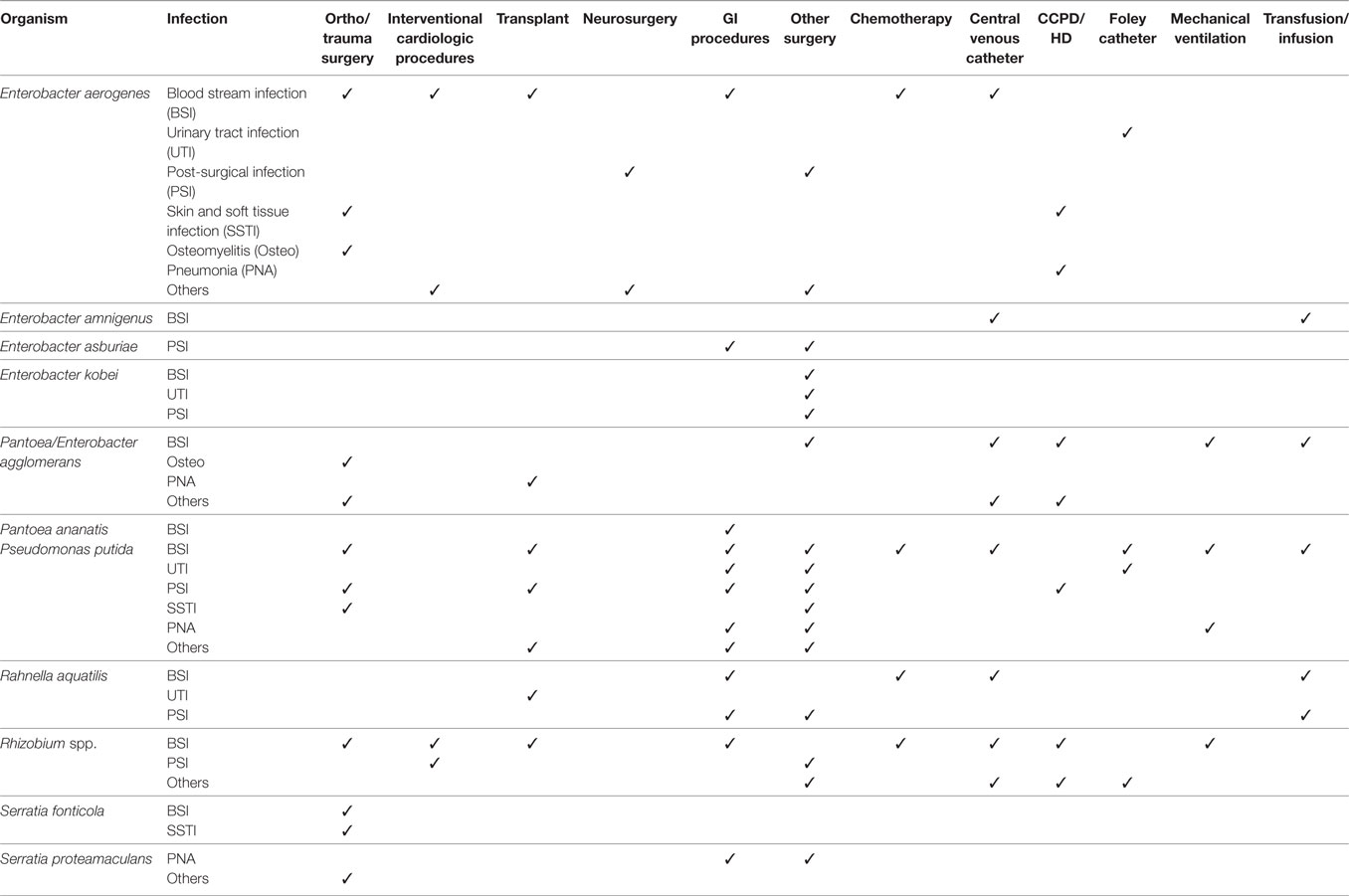

Table 3. Comorbidities associated with infections caused by saprophytic Gram-negative bacteria species.

The most common comorbidity associated with P. putida BSI were solid (31 cases) and hematologic (7 cases) malignancies (Table 3 and supplemental table). Contaminated central venous catheter (CVC), catheter lock infused with heparin, and other short-term intravascular devices were implicated with BSI in a large proportion of these patients (Table 4 and supplemental table).

Table 4. Healthcare-associated interventions associated with infections caused by saprophytic Gram-negative bacteria species.

Patients with P. agglomerans BSI also had a wide variety of underlying medical conditions and comorbidities, but no single group of comorbidity, such as cancer, was predominant, as they were with E. aerogenes and P. putida BSI (Table 3 and supplemental table). Contaminated CVCs, however, were commonly associated with BSI in this group also (Table 4 and supplemental table).

Interestingly, the frequency of types of infection varied according to GNB species. As described above, more than 80% of BSIs were caused by just three of the saprophytic GNBs—E. aerogenes, P. putida, and P. agglomerans. On the other hand, just two species—P. agglomerans (25 cases) and Enterobacter asburiae (10 cases)—accounted for 73% of the 48 SSTI cases. More than half of the 36 UTI cases were caused by E. asburiae. E. asburiae (10 cases) and P. putida (7 cases) were associated with 81% of the 21 PNA cases, while P. putida accounted for 54% of the 28 PSI patients. The most commonly reported species E. aerogenes was not associated with any PNAs and it was isolated from only three cases of PSI and from seven UTI cases.

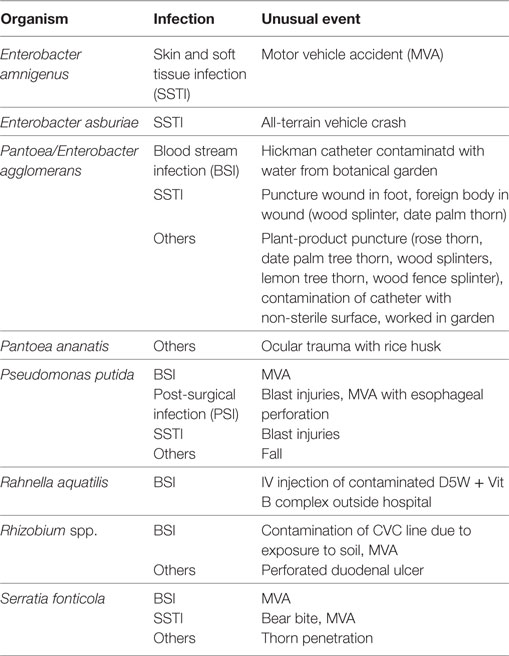

A few of these infections were triggered by accidental or atypical events (Table 5). E. amnigenus, E. asburiae and P. putida, P. agglomerans, Rhizobium spp., and S. fonticola infections were reported from six individuals involved in motor vehicle accidents (MVA) (129, 133, 143, 200, 249, 260). Three cases of P. agglomerans infections were attributed to (1) Hickman catheter contaminated with water from botanical garden (160), (2) puncture wound involving date palm tree thorn (70, 167), and (3) plant-product splinters (70, 167). One case of P. ananatis infection followed an ocular trauma with a rice husk (193). A case of Serratia fonticola infection resulted from a bear bite (258) (Table 5).

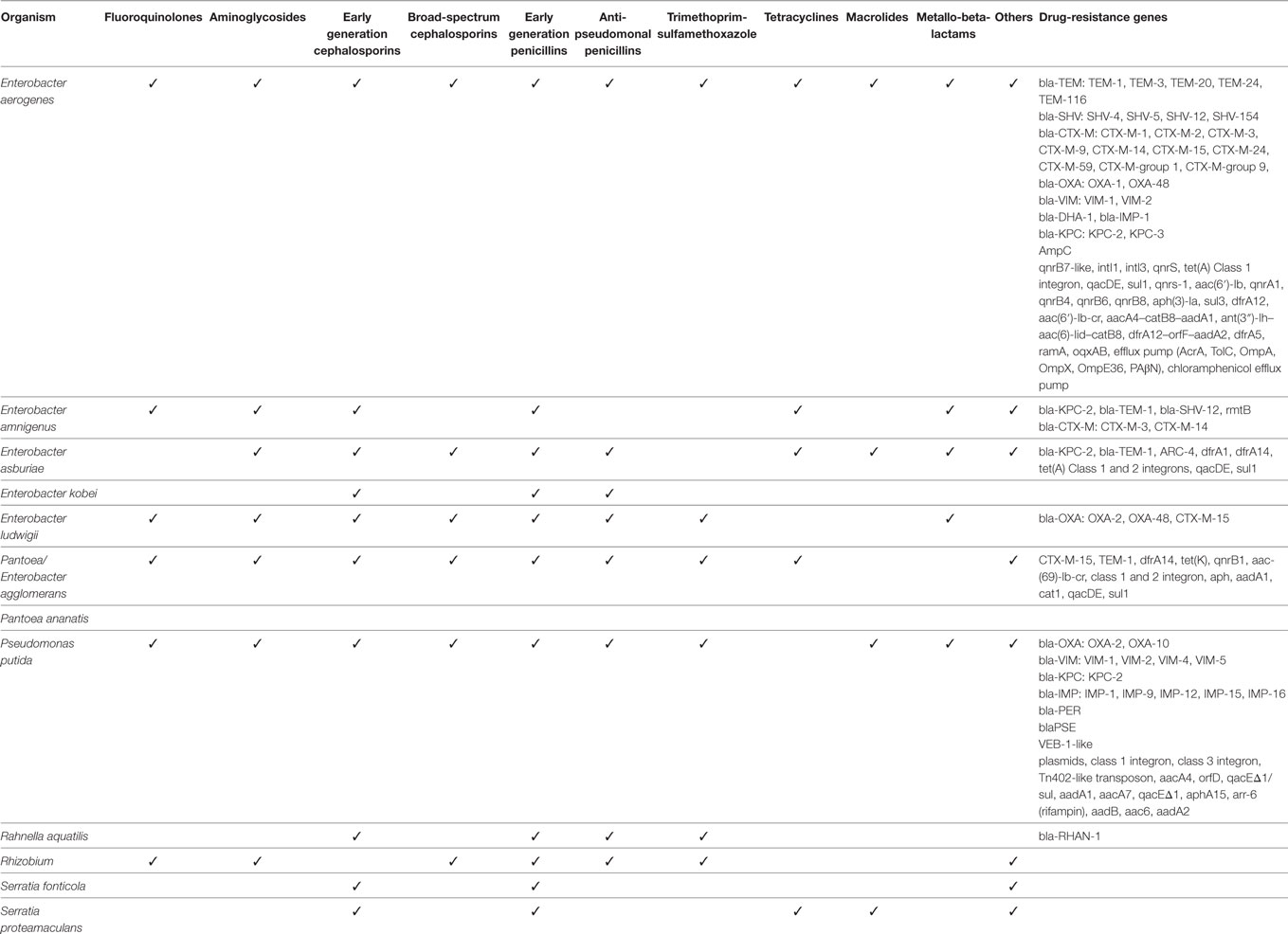

The isolates from the reported human infections exhibited a large repertoire of antimicrobial drug resistance (Table 6). In addition to resistance to earlier generation beta-lactam drugs, there were E. aerogenes, E. amnigenus, E. ludwigii, and P. agglomerans strains that were resistant to extended-spectrum beta-lactam drugs mediated by CTX-M, TEM, SHV, and OXA. Some of the E. aerogenes, E. amnigenus, E. asburiae, and P. putida strains expressed carbapenem resistance encoded by blaKPC and blaVIM. E. aerogenes and P. putida were the only GNB species that expressed IMP-1, a metallo-beta-lactamase, first described in Serratia marcescens in Japan (9), also found in Pseudomonas aeruginosa causing human infections (11).

Table 6. Drug-resistance and resistance genes of saprophytic Gram-negative bacteria species causing infection.

In addition to expressing beta-lactamases, these GNB species expressed resistance to many other classes of antimicrobial agents, including trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, polymyxin, tetracyclines, rifampicin, macrolides, and chloramphenicol. Many of these resistance phenotypes were encoded by genes on mobile elements, including plasmids and integrons (Table 6).

Interestingly, some types of drug resistance co-segregated with GNB species. No ESBLs (CTX-M, SHV, TEM) were reported to be expressed by any of the P. putida strains, while few species other than P. putida expressed IMP metallo-beta-lactamases.

Discussion

The bibliographic search covering a period from the 1990s to 2014 revealed that human infections caused by saprophytic GNB found in the environment are not uncommon. Of course, exact sources of these saprophytes that caused the infections cannot be garnered from this type of review. These 20 GNB species were targeted for this review because they were frequently found on retail spinach, which are exposed to such species environmentally.

This search most likely underestimates the true incidence since such infections are not routinely and easily diagnosed in most hospitals. An isolation of a saprophyte from a clinical sample may be discounted as a contaminant. Nevertheless, the analyses of the reports reveal several common features of these infections: (1) they are distributed worldwide, (2) they occur almost exclusively in people with underlying comorbidities or HCA interventions who come into contact with environmental sources, (3) each GNB species has a distinct predilection for a site of infection, (4) they exhibit a wide spectrum of antimicrobial drug resistance, (5) they harbor drug-resistance genes identical to those commonly carried by recognized or primary human bacterial pathogens, and (6) drug-resistance gene types co-segregate with specific GNB saprophytic species.

Both case series and hospital microbiology surveys have shown that the most commonly reported GNB species was Enterobacter aerogenes (Table 1). It was most frequently associated with BSI. Its high frequency worldwide could classify this bacterial species as an opportunistic pathogen rather than a saprophyte, similar to the way Acinetobacter baumannii, also an environmental GNB, has come to be considered an opportunistic pathogen. It was the 12th most common BSI GNB isolate in a recent study from a public hospital in San Francisco (269).

Another Enterobacter spp., E. absuriae was the most common cause of UTI and PNA among the 13 saprophytic GNB species. The UTI was associated with prostate cancer in one patient (142), and patients with PNA had other underlying medical conditions, including cachexia and possible HIV infection (137). The Enterobacter spp. are environmental saprophytes. Why this particular Enterobacter spp. and not others are associated with UTI and PNA is not known. Furthermore, no infections were reported to be caused by 7 of the 20 saprophytic species (Table 1).

One major concern with these GNB organisms is their association with HCA infections. These organisms carry drug-resistance genes typically found in human primary GNB pathogens. In fact, two of these species—E. aerogenes and Pantoea agglomerans – carried the most common and globally distributed ESBL gene blaCTX-M-15, found in the most common pandemic ExPEC lineage ST131 (17, 270). Other studies have found drug-resistance genes harbored by bacterial pathogens in environmental saprophytic organisms (12, 271, 272). Although we found no evidence that such drug-resistance genes are transferred from these saprophytes to GNB pathogens, they appear to be more ubiquitous across saprophytes than previously recognized.

There are several limitations to this type of bibliographic search. Quantitative comparison of the GNB species and their frequency of infections and associations with comorbidities or medical interventions could not be accurately performed, since not all reports included comparable data. Systematic or population-based surveys of these GNB organisms have not been conducted in many places, so our summary of the frequencies of the species and their association with infections could have been biased by a small number of reports. Nevertheless, the search has shown that these saprophytic GNB do cause infections, particularly in people with comorbidities, and that they harbor a large repertoire of drug-resistance genes.

Acinetobacter baumannii, which first began to appear in hospitals worldwide in the 1970s (273, 274), has recently become the most common non-fermentative HCA pathogen in many hospitals in Latin America, surpassing P. aeruginosa (3). In the United States, it accounts for about 3% of HCA infections, and is currently the second most common non-fermentative organism after P. aeruginosa in most hospitals (2). GNB have been a frequent cause of HCA infections for many decades, but the proportion of such infections caused by multidrug-resistant strains and new species have steadily increased in the last 20 years worldwide. It is possible that the same factors that facilitated the first appearance and subsequent endemicity of A. baumannii in healthcare institutions could contribute to the introduction and establishment of other environmental saprophytic GNB into hospitals. With ever-expanding use of immunosuppressive drugs and biologics, invasive procedures, and increased prevalence of patients with chronic medical conditions as well as advanced age, these saprophytic GNB infections are likely to increase. Hospitals need to be prepared to detect these organisms, especially in infections in which recognized pathogens are not recovered. This work also sheds light on the role of antibiotics used in animal husbandry. Such use can select for antimicrobial drug resistance in commensal bacteria in animal intestines as well as in saprophytes in the environment with ramifications for human health as demonstrated by this study.

Author Contributions

LR conceived the idea for this systematic review, based on previous work performed by ER. ER conducted the literature review, selected the publications for inclusion in the final analyses, and analyzed the data together with LR. ER wrote the first draft, which was reviewed by LR, and both authors reviewed multiple drafts to write the final draft.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This review was partly supported by RB Roberts Fund for drug-resistant bacterial infection research. We thank Arnaud Prusak for assisting with bibliographic retrieval and archiving the retrieved documents for our review.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at http://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmed.2017.00183/full#supplementary-material.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013).

2. Hidron AI, Edwards JR, Patel J, Horan TC, Sievert DM, Pollock DA, et al. NHSN annual update: antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: annual summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006-2007. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol (2008) 29(11):996–1011. doi:10.1086/591861

3. Luna CM, Rodriguez-Noriega E, Bavestrello L, Guzman-Blanco M. Gram-negative infections in adult intensive care units of latin america and the Caribbean. Crit Care Res Pract (2014) 2014:480463. doi:10.1155/2014/480463

4. Woodford N, Tierno PM Jr, Young K, Tysall L, Palepou MF, Ward E, et al. Outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing a new carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A beta-lactamase, KPC-3, in a New York Medical Center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2004) 48(12):4793–9. doi:10.1128/AAC.48.12.4793-4799.2004

5. Nordmann P, Cuzon G, Naas T. The real threat of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis (2009) 9(4):228–36. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70054-4

6. Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, Bagaria J, Butt F, Balakrishnan R, et al. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis (2010) 10(9):597–602. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70143-2

7. Pitout JD, Nordmann P, Laupland KB, Poirel L. Emergence of Enterobacteriaceae producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) in the community. J Antimicrob Chemother (2005) 56(1):52–9. doi:10.1093/jac/dki166

8. Coque TM, Baquero F, Canton R. Increasing prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Euro Surveill (2008) 13(47):19044.

9. Osano E, Arakawa Y, Wacharotayankun R, Ohta M, Horii T, Ito H, et al. Molecular characterization of an enterobacterial metallo beta-lactamase found in a clinical isolate of Serratia marcescens that shows imipenem resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (1994) 38(1):71–8. doi:10.1128/AAC.38.1.71

10. Lauretti L, Riccio ML, Mazzariol A, Cornaglia G, Amicosante G, Fontana R, et al. Cloning and characterization of blaVIM, a new integron-borne metallo-beta-lactamase gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (1999) 43(7):1584–90.

11. Lee K, Lee WG, Uh Y, Ha GY, Cho J, Chong Y. VIM- and IMP-type metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas spp. and Acinetobacter spp. in Korean hospitals. Emerg Infect Dis (2003) 9(7):868–71. doi:10.3201/eid0907.030012

12. Raphael E, Wong LK, Riley LW. Extended-spectrum Beta-lactamase gene sequences in gram-negative saprophytes on retail organic and nonorganic spinach. Appl Environ Microbiol (2011) 77(5):1601–7. doi:10.1128/AEM.02506-10

13. Pitout JD, Laupland KB. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging public-health concern. Lancet Infect Dis (2008) 8(3):159–66. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70041-0

14. Coque TM, Novais A, Carattoli A, Poirel L, Pitout J, Peixe L, et al. Dissemination of clonally related Escherichia coli strains expressing extended-spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-15. Emerg Infect Dis (2008) 14(2):195–200. doi:10.3201/eid1402.070350

15. Johnson JR, Johnston B, Clabots C, Kuskowski MA, Castanheira M. Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 as the major cause of serious multidrug-resistant E. coli infections in the United States. Clin Infect Dis (2010) 51(3):286–94. doi:10.1086/653932

16. Peirano G, Pitout JD. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli producing CTX-M beta-lactamases: the worldwide emergence of clone ST131 O25:H4. Int J Antimicrob Agents (2010) 35(4):316–21. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.11.003

17. Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Blanco J, Leflon-Guibout V, Demarty R, Alonso MP, Canica MM, et al. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J Antimicrob Chemother (2008) 61(2):273–81. doi:10.1093/jac/dkm464

18. Lin TY, Chi HW, Wang NC. Pathological fracture of the right distal radius caused by Enterobacter aerogenes osteomyelitis in an adult. Am J Med Sci (2010) 339(5):493–4. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181d94f90

19. Aschbacher R, Pagani L, Doumith M, Pike R, Woodford N, Spoladore G, et al. Metallo-beta-lactamases among Enterobacteriaceae from routine samples in an Italian tertiary-care hospital and long-term care facilities during 2008. Clin Microbiol Infect (2011) 17(2):181–9. doi:10.1111/j.1198-743X.2010.03225.x

20. Utrup TR, Mueller EW, Healy DP, Callcut RA, Peterson JD, Hurford WE. High-dose ciprofloxacin for serious gram-negative infection in an obese, critically ill patient receiving continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration. Ann Pharmacother (2010) 44(10):1660–4. doi:10.1345/aph.1P234

21. Kasap M, Fashae K, Torol S, Kolayli F, Budak F, Vahaboglu H. Characterization of ESBL (SHV-12) producing clinical isolate of Enterobacter aerogenes from a tertiary care hospital in Nigeria. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob (2010) 9:1. doi:10.1186/1476-0711-9-1

22. Chen H, Zhang Y, Chen YG, Yu YS, Zheng SS, Li LJ. Sepsis resulting from Enterobacter aerogenes resistant to carbapenems after liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int (2009) 8(3):320–2.

23. Lee SJ, Weon YC, Cha HJ, Kim SY, Seo KW, Jegal Y, et al. A case of atypical skull base osteomyelitis with septic pulmonary embolism. J Korean Med Sci (2011) 26(7):962–5. doi:10.3346/jkms.2011.26.7.962

24. Rodrigues L, Neves M, Machado S, Sa H, Macario F, Alves R, et al. Uncommon cause of chest pain in a renal transplantation patient with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: a case report. Transplant Proc (2012) 44(8):2507–9. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.07.014

25. Diene SM, Merhej V, Henry M, El Filali A, Roux V, Robert C, et al. The rhizome of the multidrug-resistant Enterobacter aerogenes genome reveals how new “killer bugs” are created because of a sympatric lifestyle. Mol Biol Evol (2013) 30(2):369–83. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss236

26. Corea EM, Bandara PL. Isolation of inducible amp C beta-lactamase producing Enterobacter aerogenes from a diabetic foot ulcer. Ceylon Med J (2010) 55(3):95. doi:10.4038/cmj.v55i3.2298

27. Torres E, Lopez-Cerero L, Del Toro MD, Pascual A. First detection and characterization of an OXA-48-producing Enterobacter aerogenes isolate. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (2014) 32(7):469–70. doi:10.1016/j.eimc.2013.10.008

28. Zanation A, Fleischman D, Chavala SH. Ptosis, erythema, and rapidly decreasing vision. JAMA (2013) 309(22):2382–3. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.5517

29. Kato M, Kaise M, Obata T, Yonezawa J, Toyoizumi H, Yoshimura N, et al. Bacteremia and endotoxemia after endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasia: pilot study. Gastric Cancer (2012) 15(1):15–20. doi:10.1007/s10120-011-0050-4

30. Iwalokun BA, Oluwadun A, Akinsinde KA, Niemogha MT, Nwaokorie FO. Bacteriologic and plasmid analysis of etiologic agents of conjunctivitis in Lagos, Nigeria. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect (2011) 1(3):95–103. doi:10.1007/s12348-011-0024-z

31. Kava BR, Kanagarajah P, Ayyathurai R. Contemporary revision penile prosthesis surgery is not associated with a high risk of implant colonization or infection: a single-surgeon series. J Sex Med (2011) 8(5):1540–6. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02222.x

32. Rodriguez-Villalobos H, Bogaerts P, Berhin C, Bauraing C, Deplano A, Montesinos I, et al. Trends in production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases among Enterobacteriaceae of clinical interest: results of a nationwide survey in Belgian hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother (2011) 66(1):37–47. doi:10.1093/jac/dkq388

33. Risch M, Radjenovic D, Han JN, Wydler M, Nydegger U, Risch L. Comparison of MALDI TOF with conventional identification of clinically relevant bacteria. Swiss Med Wkly (2010) 140:w13095. doi:10.4414/smw.2010.13095

34. Song EH, Park KH, Jang EY, Lee EJ, Chong YP, Cho OH, et al. Comparison of the clinical and microbiologic characteristics of patients with Enterobacter cloacae and Enterobacter aerogenes bacteremia: a prospective observation study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis (2010) 66(4):436–40. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.11.007

35. Vogelaers D, De Bels D, Foret F, Cran S, Gilbert E, Schoonheydt K, et al. Patterns of antimicrobial therapy in severe nosocomial infections: empiric choices, proportion of appropriate therapy, and adaptation rates – a multicentre, observational survey in critically ill patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents (2010) 35(4):375–81. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.11.015

36. Novais A, Baquero F, Machado E, Canton R, Peixe L, Coque TM. International spread and persistence of TEM-24 is caused by the confluence of highly penetrating enterobacteriaceae clones and an IncA/C2 plasmid containing Tn1696:Tn1 and IS5075-Tn21. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2010) 54(2):825–34. doi:10.1128/AAC.00959-09

37. Cano ME, Rodriguez-Martinez JM, Aguero J, Pascual A, Calvo J, Garcia-Lobo JM, et al. Detection of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes in clinical isolates of Enterobacter spp. in Spain. J Clin Microbiol (2009) 47(7):2033–9. doi:10.1128/JCM.02229-08

38. Deal EN, Micek ST, Reichley RM, Ritchie DJ. Effects of an alternative cefepime dosing strategy in pulmonary and bloodstream infections caused by Enterobacter spp, Citrobacter freundii, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a single-center, open-label, prospective, observational study. Clin Ther (2009) 31(2):299–310. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.02.015

39. Liu W, Chen L, Li H, Duan H, Zhang Y, Liang X, et al. Novel CTX-M {beta}-lactamase genotype distribution and spread into multiple species of Enterobacteriaceae in Changsha, Southern China. J Antimicrob Chemother (2009) 63(5):895–900. doi:10.1093/jac/dkp068

40. Doumith M, Ellington MJ, Livermore DM, Woodford N. Molecular mechanisms disrupting porin expression in ertapenem-resistant Klebsiella and Enterobacter spp. clinical isolates from the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother (2009) 63(4):659–67. doi:10.1093/jac/dkp029

41. Moehario LH, Tjoa E, Kiranasari A, Ningsih I, Rosana Y, Karuniawati A. Trends in antimicrobial susceptibility of gram-negative bacteria isolated from blood in Jakarta from 2002 to 2008. J Infect Dev Ctries (2009) 3(11):843–8.

42. Chang EP, Chiang DH, Lin ML, Chen TL, Wang FD, Liu CY. Clinical characteristics and predictors of mortality in patients with Enterobacter aerogenes bacteremia. J Microbiol Immunol Infect (2009) 42(4):329–35.

43. Dropa M, Balsalobre LC, Lincopan N, Lincopan EM, Murakami TM, Cassettari VC, et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases among Enterobacteriaceae isolated in a public hospital in Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop São Paulo (2009) 29(5):518–27. doi:10.1590/s0036-46652009000400005

44. Taneja N, Rao P, Arora J, Dogra A. Occurrence of ESBL & Amp-C beta-lactamases & susceptibility to newer antimicrobial agents in complicated UTI. Indian J Med Res (2008) 127(1):85–8.

45. Souli M, Kontopidou FV, Papadomichelakis E, Galani I, Armaganidis A, Giamarellou H. Clinical experience of serious infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae producing VIM-1 metallo-beta-lactamase in a Greek University Hospital. Clin Infect Dis (2008) 46(6):847–54. doi:10.1086/528719

46. Lockhart SR, Abramson MA, Beekmann SE, Gallagher G, Riedel S, Diekema DJ, et al. Antimicrobial resistance among Gram-negative bacilli causing infections in intensive care unit patients in the United States between 1993 and 2004. J Clin Microbiol (2007) 45(10):3352–9. doi:10.1128/JCM.01284-07

47. Aibinu I, Pfeifer Y, Peters F, Ogunsola F, Adenipekun E, Odugbemi T, et al. Emergence of bla(CTX-M-15), qnrB1 and aac(6’)-Ib-cr resistance genes in Pantoea agglomerans and Enterobacter cloacae from Nigeria (sub-Saharan Africa). J Med Microbiol (2012) 61(Pt 1):165–7. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.035238-0

48. Al-Tawfiq JA, Antony A, Abed MS. Antimicrobial resistance rates of Enterobacter spp.: a seven-year surveillance study. Med Princ Pract (2009) 18(2):100–4. doi:10.1159/000189806

49. Anastay M, Lagier E, Blanc V, Chardon H. [Epidemiology of extended spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) Enterobacteriaceae in a General Hospital, South of France, 1999-2007]. Pathol Biol (2013) 61(2):38–43. doi:10.1016/j.patbio.2012.03.001

50. Walkty A, Adam HJ, Laverdiere M, Karlowsky JA, Hoban DJ, Zhanel GG, et al. In vitro activity of ceftobiprole against frequently encountered aerobic and facultative Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial pathogens: results of the CANWARD 2007-2009 study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis (2011) 69(3):348–55. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.10.032

51. Kanamori H, Navarro RB, Yano H, Sombrero LT, Capeding MR, Lupisan SP, et al. Molecular characteristics of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae from the Philippines. Acta Trop (2011) 120(1–2):140–5. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.07.007

52. Zhang R, Cai JC, Zhou HW, Nasu M, Chen GX. Genotypic characterization and in vitro activities of tigecycline and polymyxin B for members of the Enterobacteriaceae with decreased susceptibility to carbapenems. J Med Microbiol (2011) 60(Pt 12):1813–9. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.025668-0

53. Lavigne JP, Sotto A, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Bouziges N, Bourg G, Davin-Regli A, et al. Membrane permeability, a pivotal function involved in antibiotic resistance and virulence in Enterobacter aerogenes clinical isolates. Clin Microbiol Infect (2012) 18(6):539–45. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03607.x

54. Rodriguez-Martinez JM, Fernandez-Echauri P, Fernandez-Cuenca F, Diaz de Alba P, Briales A, Pascual A. Genetic characterization of an extended-spectrum AmpC cephalosporinase with hydrolysing activity against fourth-generation cephalosporins in a clinical isolate of Enterobacter aerogenes selected in vivo. J Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (2012) 67(1):64–8. doi:10.1093/jac/dkr423

55. Jeong HS, Bae IK, Shin JH, Jung HJ, Kim SH, Lee JY, et al. Prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance and its association with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and AmpC beta-lactamase in Enterobacteriaceae. Korean J Lab Med (2011) 31(4):257–64. doi:10.3343/kjlm.2011.31.4.257

56. Ruiz E, Ocampo-Sosa AA, Alcoba-Florez J, Roman E, Arlet G, Torres C, et al. Changes in ciprofloxacin resistance levels in Enterobacter aerogenes isolates associated with variable expression of the aac(6’)-Ib-cr gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2012) 56(2):1097–100. doi:10.1128/AAC.05074-11

57. Heller I, Grif K, Orth D. Emergence of VIM-1-carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter cloacae in Tyrol, Austria. J Med Microbiol (2012) 61(Pt 4):567–71. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.038646-0

58. Cheng NC, Liu CY, Huang YT, Liao CH, Teng LJ, Hsueh PR. In vitro susceptibilities of clinical isolates of ertapenem-non-susceptible Enterobacteriaceae to cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefepime and aztreonam. J Antimicrob Chemother (2012) 67(6):1413–21. doi:10.1093/jac/dks042

59. Wu K, Wang F, Sun J, Wang Q, Chen Q, Yu S, et al. Class 1 integron gene cassettes in multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in southern China. Int J Antimicrob Agents (2012) 40(3):264–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.05.017

60. Carbonne A, Arnaud I, Maugat S, Marty N, Dumartin C, Bertrand X, et al. National multidrug-resistant bacteria (MDRB) surveillance in France through the RAISIN network: a 9 year experience. J Antimicrob Chemother (2013) 68(4):954–9. doi:10.1093/jac/dks464

61. Lavigne JP, Sotto A, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Bouziges N, Pages JM, Davin-Regli A. An adaptive response of Enterobacter aerogenes to imipenem: regulation of porin balance in clinical isolates. Int J Antimicrob Agents (2013) 41(2):130–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.10.010

62. Veleba M, De Majumdar S, Hornsey M, Woodford N, Schneiders T. Genetic characterization of tigecycline resistance in clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae and Enterobacter aerogenes. J Antimicrob Chemother (2013) 68(5):1011–8. doi:10.1093/jac/dks530

63. Trivedi M, Patel V, Soman R, Rodriguez C, Singhal T. The outcome of treating ESBL infections with carbapenems vs. non carbapenem antimicrobials. J Assoc Physicians India (2012) 60:28–30.

64. Nogueira Kda S, Paganini MC, Conte A, Cogo LL, Taborda de Messias Reason I, da Silva MJ, et al. Emergence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacter spp. in patients with bacteremia in a tertiary hospital in southern Brazil. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (2014) 32(2):87–92. doi:10.1016/j.eimc.2013.02.004

65. Sheng WH, Badal RE, Hsueh PR, Program S. Distribution of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases, AmpC beta-lactamases, and carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae isolates causing intra-abdominal infections in the Asia-Pacific region: results of the study for monitoring antimicrobial resistance trends (SMART). Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2013) 57(7):2981–8. doi:10.1128/AAC.00971-12

66. Ghobrial GM, Thakkar V, Andrews E, Lang M, Chitale A, Oppenlander ME, et al. Intraoperative vancomycin use in spinal surgery: single institution experience and microbial trends. Spine (2014) 39(7):550–5. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000241

67. Hoban DJ, Badal R, Bouchillon S, Hackel M, Kazmierczak K, Lascols C, et al. In vitro susceptibility and distribution of beta-lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae causing intra-abdominal infections in North America 2010-2011. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis (2014) 79(3):367–72. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.03.026

68. Huh K, Kang CI, Kim J, Cho SY, Ha YE, Joo EJ, et al. Risk factors and treatment outcomes of bloodstream infection caused by extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacter species in adults with cancer. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis (2014) 78(2):172–7. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.11.002

69. Karlowsky JA, Adam HJ, Baxter MR, Lagace-Wiens PR, Walkty AJ, Hoban DJ, et al. In vitro activity of ceftaroline-avibactam against gram-negative and gram-positive pathogens isolated from patients in Canadian hospitals from 2010 to 2012: results from the CANWARD surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2013) 57(11):5600–11. doi:10.1128/AAC.01485-13

70. Vaiman M, Lazarovich T, Lotan G. Pantoea agglomerans as an indicator of a foreign body of plant origin in cases of wound infection. J Wound Care (2013) 22(4):184–5. doi:10.12968/jowc.2013.22.4.182

71. Chen L, Chavda KD, Melano RG, Jacobs MR, Koll B, Hong T, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of KPC-encoding pKpQIL-like plasmids and their distribution in New Jersey and New York Hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2014) 58(5):2871–7. doi:10.1128/AAC.00120-14

72. Mishra MP, Debata NK, Padhy RN. Surveillance of multidrug resistant uropathogenic bacteria in hospitalized patients in Indian. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed (2013) 3(4):315–24. doi:10.1016/s2221-1691(13)60071-4

73. Ahn C, Syed A, Hu F, O’Hara JA, Rivera JI, Doi Y. Microbiological features of KPC-producing Enterobacter isolates identified in a U.S. hospital system. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis (2014) 80(2):154–8. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.06.010

74. Pena I, Picazo JJ, Rodriguez-Avial C, Rodriguez-Avial I. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a tertiary hospital in Madrid, Spain: high percentage of colistin resistance among VIM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST11 isolates. Int J Antimicrob Agents (2014) 43(5):460–4. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.01.021

75. Kuai S, Shao H, Huang L, Pei H, Lu Z, Wang W, et al. KPC-2 carbapenemase and DHA-1 AmpC determinants carried on the same plasmid in Enterobacter aerogenes. J Med Microbiol (2014) 63(Pt 3):367–70. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.054627-0

76. Luo Y, Yang J, Ye L, Guo L, Zhao Q, Chen R, et al. Characterization of KPC-2-producing Escherichia coli, Citrobacter freundii, Enterobacter cloacae, Enterobacter aerogenes, and Klebsiella oxytoca isolates from a Chinese Hospital. Microb Drug Resist (2014) 20(4):264–9. doi:10.1089/mdr.2013.0150

77. Garbati MA, Bin Abdulhak A, Baba K, Sakkijha H. Infection due to colistin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in critically-ill patients. J Infect Dev Ctries (2013) 7(10):713–9. doi:10.3855/jidc.2851

78. Jain R, Walk ST, Aronoff DM, Young VB, Newton DW, Chenoweth CE, et al. Emergence of Carbapenemaseproducing Klebsiella pneumoniae of sequence type 258 in Michigan, USA. Infect Dis Rep (2013) 5(1):e5. doi:10.4081/idr.2013.e5

79. Markovska RD, Stoeva TJ, Bojkova KD, Mitov IG. Epidemiology and molecular characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacter spp., Pantoea agglomerans, and Serratia marcescens isolates from a Bulgarian hospital. Microb Drug Resist (2014) 20(2):131–7. doi:10.1089/mdr.2013.0102

80. Kangozhinova K, Abentayeva B, Repa A, Baltabayeva A, Erwa W, Stauffer F. Culture proven newborn sepsis with a special emphasis on late onset sepsis caused by Enterobacteriaceae in a level III neonatal care unit in Astana, Kazakhstan. Wien Klin Wochenschr (2013) 125(19–20):611–5. doi:10.1007/s00508-013-0416-1

81. Balkan II, Aygun G, Aydin S, Mutcali SI, Kara Z, Kuskucu M, et al. Blood stream infections due to OXA-48-like carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: treatment and survival. Int J Infect Dis (2014) 26:51–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2014.05.012

82. Novais A, Rodrigues C, Branquinho R, Antunes P, Grosso F, Boaventura L, et al. Spread of an OmpK36-modified ST15 Klebsiella pneumoniae variant during an outbreak involving multiple carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae species and clones. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis (2012) 31(11):3057–63. doi:10.1007/s10096-012-1665-z

83. Narayan SA, Kool JL, Vakololoma M, Steer AC, Mejia A, Drake A, et al. Investigation and control of an outbreak of Enterobacter aerogenes bloodstream infection in a neonatal intensive care unit in Fiji. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol (2009) 30(8):797–800. doi:10.1086/598240

84. Bhat SS, Undrakonda V, Mukhopadhyay C, Parmar PV. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant acute postoperative endophthalmitis due to Enterobacter aerogenes. Ocul Immunol Inflamm (2014) 22(2):121–6. doi:10.3109/09273948.2013.830752

85. Akhtar N, Alqurashi AM, Abu Twibah M. In vitro ciprofloxacin resistance profiles among gram-negative bacteria isolated from clinical specimens in a teaching hospital. J Pak Med Assoc (2010) 60(8):625–7.

86. Anderson B, Nicholas S, Sprague B, Campos J, Short B, Singh N. Molecular and descriptive epidemiologyof multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in hospitalized infants. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol (2008) 29(3):250–5. doi:10.1086/527513

87. Baskin E, Ozcay F, Sakalli H, Agras PI, Karakayali H, Canan O, et al. Frequency of urinary tract infection in pediatric liver transplantation candidates. Pediatr Transplant (2007) 11(4):402–7. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3046.2006.00674.x

88. Biendo M, Canarelli B, Thomas D, Rousseau F, Hamdad F, Adjide C, et al. Successive emergence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter aerogenes isolates in a university hospital. J Clin Microbiol (2008) 46(3):1037–44. doi:10.1128/JCM.00197-07

89. Brasme L, Nordmann P, Fidel F, Lartigue MF, Bajolet O, Poirel L, et al. Incidence of class A extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Champagne-Ardenne (France): a 1 year prospective study. J Antimicrob Chemother (2007) 60(5):956–64. doi:10.1093/jac/dkm319

90. Chen CY, Hansen KS, Hansen LK. Rhizobium radiobacter as an opportunistic pathogen in central venous catheter-associated bloodstream infection: case report and review. J Hosp Infect (2008) 68(3):203–7. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2007.11.021

91. Chen YG, Zhang Y, Yu YS, Qu TT, Wei ZQ, Shen P, et al. In vivo development of carbapenem resistance in clinical isolates of Enterobacter aerogenes producing multiple beta-lactamases. Int J Antimicrob Agents (2008) 32(4):302–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.02.014

92. Chevalier J, Mulfinger C, Garnotel E, Nicolas P, Davin-Regli A, Pages JM. Identification and evolution of drug efflux pump in clinical Enterobacter aerogenes strains isolated in 1995 and 2003. PLoS One (2008) 3(9):e3203. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003203

93. Cohen Stuart J, Mouton JW, Diederen BM, Al Naiemi N, Thijsen S, Vlaminckx BJ, et al. Evaluation of Etest to determine tigecycline MICs for Enterobacter species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2010) 54(6):2746–7. doi:10.1128/AAC.01726-09

94. Deal EN, Micek ST, Ritchie DJ, Reichley RM, Dunne WM Jr, Kollef MH. Predictors of in-hospital mortality for bloodstream infections caused by Enterobacter species or Citrobacter freundii. Pharmacotherapy (2007) 27(2):191–9. doi:10.1592/phco.27.2.191

95. Dhakal S, Manandhar S, Shrestha B, Dhakal R, Pudasaini M. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing multidrug resistant urinary isolates from children visiting Kathmandu Model Hospital. Nepal Med Coll J (2012) 14(2):136–41.

96. DiPersio JR, Dowzicky MJ. Regional variations in multidrug resistance among Enterobacteriaceae in the USA and comparative activity of tigecycline, a new glycylcycline antimicrobial. Int J Antimicrob Agents (2007) 29(5):518–27. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.10.019

97. Galas M, Decousser JW, Breton N, Godard T, Allouch PY, Pina P, et al. Nationwide study of the prevalence, characteristics, and molecular epidemiology of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2008) 52(2):786–9. doi:10.1128/AAC.00906-07

98. Ghisalberti D, Mahamoud A, Chevalier J, Baitiche M, Martino M, Pages JM, et al. Chloroquinolines block antibiotic efflux pumps in antibiotic-resistant Enterobacter aerogenes isolates. Int J Antimicrob Agents (2006) 27(6):565–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.03.010

99. Giraud-Morin C, Fosse T. [Recent evolution and characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing enterobacteria in the CHU of Nice (2005-2007)]. Pathol Biol (2008) 56(7–8):417–23. doi:10.1016/j.patbio.2008.07.003

100. Goethaert K, Van Looveren M, Lammens C, Jansens H, Baraniak A, Gniadkowski M, et al. High-dose cefepime as an alternative treatment for infections caused by TEM-24 ESBL-producing Enterobacter aerogenes in severely-ill patients. Clin Microbiol Infect (2006) 12(1):56–62. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2005.01290.x

101. Horianopoulou M, Legakis NJ, Kanellopoulou M, Lambropoulos S, Tsakris A, Falagas ME. Frequency and predictors of colonization of the respiratory tract by VIM-2-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in patients of a newly established intensive care unit. J Med Microbiol (2006) 55(Pt 10):1435–9. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.46713-0

102. Wang JH, Lee BJ, Jang YJ. Bacterial coinfection and antimicrobial resistance in patients with paranasal sinus fungus balls. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol (2010) 119(6):406–11. doi:10.1177/000348941011900608

103. Lang PO, Jehl F, Berthel M, Kaltenbach G. [Microbial description of bacteriuria in long-term care facilities: a prospective study in the French Teaching Hospital of Strasbourg]. Med Mal Infect (2006) 36(5):280–4. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2005.12.010

104. Khatri B, Basnyat S, Karki A, Poudel A, Shrestha B. Etiology and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of bacterial pathogens from urinary tract infection. Nepal Med Coll J (2012) 14(2):129–32.

105. Pina P, Pangon B, Rio Y, Chardon H, Lallali AK, Allouch PY. [Antibiotic sensitivity of enterobacteria in intensive care units]. Pathol Biol (2000) 48(5):485–9.

106. Park YJ, Yu JK, Lee S, Oh EJ, Woo GJ. Prevalence and diversity of qnr alleles in AmpC-producing Enterobacter cloacae, Enterobacter aerogenes, Citrobacter freundii and Serratia marcescens: a multicentre study from Korea. J Antimicrob Chemother (2007) 60(4):868–71. doi:10.1093/jac/dkm266

107. Otajevwo FD. Urinary tract infection among symptomatic outpatients visiting a tertiary hospital based in midwestern Nigeria. Glob J Health Sci (2013) 5(2):187–99. doi:10.5539/gjhs.v5n2p187

108. Martinez D, Rodulfo HE, Rodriguez L, Cana LE, Medina B, Guzman M, et al. First report of metallo-beta-lactamases producing Enterobacter spp. strains from Venezuela. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo (2014) 56(1):67–9. doi:10.1590/S0036-46652014000100010

109. Machado E, Coque TM, Canton R, Novais A, Sousa JC, Baquero F, et al. High diversity of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases among clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae from Portugal. J Antimicrob Chemother (2007) 60(6):1370–4. doi:10.1093/jac/dkm381

110. Vonberg RP, Wolter A, Kola A, Ziesing S, Gastmeier P. The endemic situation of Enterobacter aerogenes and Enterobacter cloacae: you will only discover what you are looking for. J Hosp Infect (2007) 65(4):372–4. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2006.12.010

111. Tsakris A, Poulou A, Themeli-Digalaki K, Voulgari E, Pittaras T, Sofianou D, et al. Use of boronic acid disk tests to detect extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in clinical isolates of KPC carbapenemase-possessing enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol (2009) 47(11):3420–6. doi:10.1128/JCM.01314-09

112. Schumacher A, Steinke P, Bohnert JA, Akova M, Jonas D, Kern WV. Effect of 1-(1-naphthylmethyl)-piperazine, a novel putative efflux pump inhibitor, on antimicrobial drug susceptibility in clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae other than Escherichia coli. J Antimicrob Chemother (2006) 57(2):344–8. doi:10.1093/jac/dki446

113. Sundaram V, Kumar P, Dutta S, Mukhopadhyay K, Ray P, Gautam V, et al. Blood culture confirmed bacterial sepsis in neonates in a North Indian tertiary care center: changes over the last decade. Jpn J Infect Dis (2009) 62(1):46–50.

114. Ryan RJ, Lindsell C, Sheehan P. Fluoroquinolone resistance during 2000-2005: an observational study. BMC Infect Dis (2008) 8:71. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-8-71

115. Wong MR, Del Rosso P, Heine L, Volpe V, Lee L, Kornblum J, et al. An outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter aerogenes bacteremia after interventional pain management procedures, New York City, 2008. Reg Anesth Pain Med (2010) 35(6):496–9. doi:10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181fa1163

116. Bilgen H, Ozek E, Unver T, Biyikli N, Alpay H, Cebeci D. Urinary tract infection and hyperbilirubinemia. Turk J Pediatr (2006) 48(1):51–5.

117. Cunha BA, McDermott B, Nausheen S. Single daily high-dose tigecycline therapy of a multidrug-resistant (MDR) Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter aerogenes nosocomial urinary tract infection. J Chemother (2007) 19(6):753–4. doi:10.1179/joc.2007.19.6.753

118. Edouard S, Sailler L, Sagot C, Munsch C, Astudillo L, Arlet P. [A painful thumb]. La Revue de Médecine Interne (2010) 31(10):712–3. doi:10.1016/j.revmed.2009.12.015

119. Ghosh J, Murray D, Khwaja N, Murphy MO, Halka A, Walker MG. Late infection of an endovascular stent graft with septic embolization, colonic perforation, and aortoduodenal fistula. Ann Vasc Surg (2006) 20(2):263–6. doi:10.1007/s10016-006-9006-2

120. Laguna-del Estal P, Garcia-Montero P, Agud-Fernandez M, Lopez-Cano Gomez M, Castaneda-Pastor A, Garcia-Zubiri C. [Bacterial meningitis due to gram-negative bacilli in adults]. Rev Neurol (2010) 50(8):458–62.

121. Parker R, Gul R, Bucknall V, Bowley D, Karandikar S. Double jeopardy: pyogenic liver abscess and massive secondary rectal haemorrhage after rubber band ligation of haemorrhoids. Colorectal Dis (2011) 13(7):e184. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02387.x

122. Ondounda M, Tanon A, Ehui E, Ouattara I, Kassi A, Aba YT, et al. [Two cases of Fanconi’s syndrome induced by tenofovir in the Ivory Coast]. Med Mal Infect (2011) 41(2):105–7. doi:10.1016/j.medmal.2010.07.009

123. Wunderlich CA, Krach LE. Gram-negative meningitis and infections in individuals treated with intrathecal baclofen for spasticity: a retrospective study. Dev Med Child Neurol (2006) 48(6):450–5. doi:10.1017/S0012162206000971

124. Van Ende C, Tintillier M, Cuvelier C, Migali G, Pochet JM. Intraperitoneal meropenem administration: a possible alternative to the intravenous route. Perit Dial Int (2010) 30(2):250–1. doi:10.3747/pdi.2009.00052

125. van der Meer W, Stephen Scott C, Verlaat C, Gunnewiek JK, Warris A. Measurement of neutrophil membrane CD64 and HLA-Dr in a patient with abdominal sepsis. J Infect (2006) 53(1):e43–6. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2005.09.003

126. Smith T, Goldschlager T, Mott N, Robertson T, Campbell S. Optic atrophy due to Curvularia lunata mucocoele. Pituitary (2007) 10(3):295–7. doi:10.1007/s11102-007-0012-3

127. Santana L, Caceres JJ, Sanchez-Palacios M, Casamitjana A. [Acute renal failure associated with severe falciparum malaria]. Nefrologia (2006) 26(6):751–2.

128. Rondina MT, Raphael K, Pendleton R, Sande MA. Abdominal aortitis due to Streptococcus pneumoniae and Enterobacter aerogenes: a case report and review. J Gen Intern Med (2006) 21(7):C1–3. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00455.x

129. Corti G, Mondanelli N, Losco M, Bartolini L, Fontanelli A, Paradisi F. Post-traumatic infection of the lower limb caused by rare Enterobacteriaceae and Mucorales in a young healthy male. Int J Infect Dis (2009) 13(2):e57–60. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2008.06.029

130. Westerfeld C, Papaliodis GN, Behlau I, Durand ML, Sobrin L. Enterobacter amnigenus endophthalmitis. Retin Cases Brief Rep (2009) 3(4):409–11. doi:10.1097/ICB.0b013e31818a46c0

131. Sheng JF, Li JJ, Tu S, Sheng ZK, Bi S, Zhu MH, et al. blaKPC and rmtB on a single plasmid in Enterobacter amnigenus and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from the same patient. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis (2012) 31(7):1585–91. doi:10.1007/s10096-011-1481-x

132. Korah S, Braganza A, Jacob P, Balaji V. An “epidemic” of post cataract surgery endophthalmitis by a new organism. Indian J Ophthalmol (2007) 55(6):464–6. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.36486

133. Bollet C, Elkouby A, Pietri P, de Micco P. Isolation of Enterobacter amnigenus from a heart transplant recipient. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis (1991) 10(12):1071–3. doi:10.1007/BF01984933

134. Bollet C, Gainnier M, Sainty JM, Orhesser P, De Micco P. Serratia fonticola isolated from a leg abscess. J Clin Microbiol (1991) 29(4):834–5.

135. Jan D, Berlie C, Babin G. [Fatal posttransfusion Enterobacter amnigenus septicemia]. Presse Med (1999) 28(18):965.

136. Capdevila JA, Bisbe V, Gasser I, Zuazu J, Olive T, Fernandez F, et al. [Enterobacter amnigenus. An unusual human pathogen]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (1998) 16(8):364–6.

137. Stewart JM, Quirk JR. Community-acquired pneumonia caused by Enterobacter asburiae. Am J Med (2001) 111(1):82–3. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(01)00791-4

138. Kang CI, Kim SH, Park WB, Lee KD, Kim HB, Oh MD, et al. Bloodstream infections caused by Enterobacter species: predictors of 30-day mortality rate and impact of broad-spectrum cephalosporin resistance on outcome. Clin Infect Dis (2004) 39(6):812–8. doi:10.1086/423382

139. Tofteland S, Naseer U, Lislevand JH, Sundsfjord A, Samuelsen O. A long-term low-frequency hospital outbreak of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae involving intergenus plasmid diffusion and a persisting environmental reservoir. PLoS One (2013) 8(3):e59015. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059015

140. Stock I, Gruger T, Wiedemann B. Natural antibiotic susceptibility of strains of the Enterobacter cloacae complex. Int J Antimicrob Agents (2001) 18(6):537–45. doi:10.1016/S0924-8579(01)00463-0

141. Pitout JD, Moland ES, Sanders CC, Thomson KS, Fitzsimmons SR. Beta-lactamases and detection of beta-lactam resistance in Enterobacter spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (1997) 41(1):35–9.

142. Brenner DJ, McWhorter AC, Kai A, Steigerwalt AG, Farmer JJ III. Enterobacter asburiae sp. nov., a new species found in clinical specimens, and reassignment of Erwinia dissolvens and Erwinia nimipressuralis to the genus Enterobacter as Enterobacter dissolvens comb. nov. and Enterobacter nimipressuralis comb. nov. J Clin Microbiol (1986) 23(6):1114–20.

143. Koth K, Boniface J, Chance EA, Hanes MC. Enterobacter asburiae and Aeromonas hydrophila: soft tissue infection requiring debridement. Orthopedics (2012) 35(6):e996–9. doi:10.3928/01477447-20120525-52

144. Hoffmann H, Schmoldt S, Trulzsch K, Stumpf A, Bengsch S, Blankenstein T, et al. Nosocomial urosepsis caused by Enterobacter kobei with aberrant phenotype. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis (2005) 53(2):143–7. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2005.06.008

145. Hoffmann H, Stindl S, Stumpf A, Mehlen A, Monget D, Heesemann J, et al. Description of Enterobacter ludwigii sp. nov., a novel Enterobacter species of clinical relevance. Syst Appl Microbiol (2005) 28(3):206–12. doi:10.1016/j.syapm.2004.12.009

146. Mokracka J, Koczura R, Pawlowski K, Kaznowski A. Resistance patterns and integron cassette arrays of Enterobacter cloacae complex strains of human origin. J Med Microbiol (2011) 60(Pt 6):737–43. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.027979-0

147. Kosako Y, Tamura K, Sakazaki R, Miki K. Enterobacter kobei sp. nov., a new species of the family Enterobacteriaceae resembling Enterobacter cloacae. Curr Microbiol (1996) 33(4):261–5. doi:10.1007/s002849900110

148. Khajuria A, Praharaj AK, Grover N, Kumar M. First report of an Enterobacter ludwigii isolate coharboring NDM-1 and OXA-48 carbapenemases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2013) 57(10):5189–90. doi:10.1128/AAC.00789-13

149. O’Hara CM, Steigerwalt AG, Hill BC, Miller JM, Brenner DJ. First report of a human isolate of Erwinia persicinus. J Clin Microbiol (1998) 36(1):248–50.

150. Morales Ruiz J, Espinosa Aguilar MD, Lopez Garrido MA, Nogueras Lopez F, Vinolo Ubina C. [Pantoea agglomerans bacteriemia in a liver transplant patient]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig (2010) 102(1):61–2.

151. Harris EJ. Retained Hawthorn fragment in a child’s foot complicated by infection: diagnosis and excision aided by localization with ultrasound. J Foot Ankle Surg (2010) 49(2):161–5. doi:10.1053/j.jfas.2009.08.012

152. Borras M, Roig J, Garcia M, Fernandez E. Adverse effects of pantoea peritonitis on peritoneal transport. Perit Dial Int (2009) 29(2):234–5.

153. Duerinckx JF. Case report: subacute synovitis of the knee after a rose thorn injury: unusual clinical picture. Clin Orthop Relat Res (2008) 466(12):3138–42. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0482-2

154. Lim PS, Chen SL, Tsai CY, Pai MA. Pantoea peritonitis in a patient receiving chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Nephrology (2006) 11(2):97–9. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1797.2006.00552.x

155. Cicchetti R, Iacobini M, Midulla F, Papoff P, Mancuso M, Moretti C. Pantoea agglomerans sepsis after rotavirus gastroenteritis. Pediatr Infect Dis J (2006) 25(3):280–1. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000202211.64017.c6

156. Lalas KM, Erichsen D. Sporadic Pantoea agglomerans bacteremia in a near-term female: case report and review of literature. Jpn J Infect Dis (2010) 63(4):290–1.

157. Aly NY, Salmeen HN, Lila RA, Nagaraja PA. Pantoea agglomerans bloodstream infection in preterm neonates. Med Princ Pract (2008) 17(6):500–3. doi:10.1159/000151575

158. Seok S, Jang YJ, Lee SW, Kim HC, Ha GY. A case of bilateral endogenous Pantoea agglomerans endophthalmitis with interstitial lung disease. Korean J Ophthalmol (2010) 24(4):249–51. doi:10.3341/kjo.2010.24.4.249

159. Bachmeyer C, Entressengle H, Gibeault M, Nedellec G, M’Bappe P, Delisle F, et al. Bilateral tibial chronic osteomyelitis due to Pantoea agglomerans in a patient with sickle cell disease. Rheumatology (2007) 46(8):1247. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kem127

160. Russell K, Waghorn D, Devi R. The potential perils of a visit to botanical gardens in a patient with a central intravascular device. J Hosp Infect (2007) 66(4):402–4. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2007.05.003

161. Bergman KA, Arends JP, Scholvinck EH. Pantoea agglomerans septicemia in three newborn infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J (2007) 26(5):453–4. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000261200.83869.92

162. Fullerton DG, Lwin AA, Lal S. Pantoea agglomerans liver abscess presenting with a painful thigh. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol (2007) 19(5):433–5. doi:10.1097/MEG.0b013e3280ad4414

163. Hsieh CT, Liang JS, Peng SS, Lee WT. Seizure associated with total parenteral nutrition-related hypermanganesemia. Pediatr Neurol (2007) 36(3):181–3. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.10.005

164. Uche A. Pantoea agglomerans bacteremia in a 65-year-old man with acute myeloid leukemia: case report and review. South Med J (2008) 101(1):102–3. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31815d3ca6

165. Magnette C, Tintillier M, Horlait G, Cuvelier C, Pochet JM. Severe peritonitis due to Pantoea agglomerans in a CCPD patient. Perit Dial Int (2008) 28(2):207–8.

166. Naha K, Ramamoorthi, Prabhu M. Spontaneous septicaemia with multi – organ dysfunction – a new face for Pantoe agglomerans? Asian Pac J Trop Med (2012) 5(1):83–4. doi:10.1016/s1995-7645(11)60252-6

167. Rave O, Assous MV, Hashkes PJ, Lebel E, Hadas-Halpern I, Megged O. Pantoea agglomerans foreign body-induced septic arthritis. Pediatr Infect Dis J (2012) 31(12):1311–2. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e31826fd434

168. Ferrantino M, Navaneethan SD, Sloand JA. Pantoea agglomerans: an unusual inciting agent in peritonitis. Perit Dial Int (2008) 28(4):428–30.

169. Habhab W, Blake PG. Pantoea peritonitis: not just a “thorny” problem. Perit Dial Int (2008) 28(4):430.

170. Shubov A, Jagannathan P, Chin-Hong PV. Pantoea agglomerans pneumonia in a heart-lung transplant recipient: case report and a review of an emerging pathogen in immunocompromised hosts. Transpl Infect Dis (2011) 13(5):536–9. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00630.x

171. Grangl G, Gallistl S, Leschnik B, Muntean W. Port-A-Cath infection causes inhibitor recurrence after initial successful ITI. Haemophilia (2013) 19(3):e174–5. doi:10.1111/hae.12103

172. Kazancioglu R, Buyukaydin B, Iraz M, Alay M, Erkoc R. An unusual cause of peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis patients: Pantoea agglomerans. J Infect Dev Ctries (2014) 8(7):919–22. doi:10.3855/jidc.3785

173. Kletke SN, Brissette AR, Gale J. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis caused by Pantoea species: a case report. Can J Ophthalmol (2014) 49(1):e1–2. doi:10.1016/j.jcjo.2013.09.004

174. Fernandez-Munoz H, Lassaletta A, Gonzalez MJ, Andion M, Madero L. Pantoea agglomerans bacteremia in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia during induction therapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol (2015) 37(4):328. doi:10.1097/MPH.0000000000000190

175. Hischebeth GT, Kohlhof H, Wimmer MD, Randau TM, Bekeredjian-Ding I, Gravius S. Detection of Pantoea agglomerans in hip prosthetic infection by sonication of the removed prosthesis: the first reported case. Technol Health Care (2013) 21(6):613–8. doi:10.3233/THC-130757

176. Kahveci A, Asicioglu E, Tigen E, Ari E, Arikan H, Odabasi Z, et al. Unusual causes of peritonitis in a peritoneal dialysis patient: Alcaligenes faecalis and Pantoea agglomerans. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob (2011) 10:12. doi:10.1186/1476-0711-10-12

177. Deps PD. Scalp abscess due to Enterobacter agglomerans. Int J Dermatol (2006) 45(4):482–3. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02618.x

178. Volksch B, Thon S, Jacobsen ID, Gube M. Polyphasic study of plant- and clinic-associated Pantoea agglomerans strains reveals indistinguishable virulence potential. Infect Genet Evol (2009) 9(6):1381–91. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2009.09.016

179. Kenchappa P, Rao KR, Ahmed N, Joshi S, Ghousunnissa S, Vijayalakshmi V, et al. Fluorescent amplified fragment length polymorphism (FAFLP) based molecular epidemiology of hospital infections in a tertiary care setting in Hyderabad, India. Infect Genet Evol (2006) 6(3):220–7. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2005.05.003

180. Goncalves MO, Coutinho-Filho WP, Pimenta FP, Pereira GA, Pereira JA, Mattos-Guaraldi AL, et al. Periodontal disease as reservoir for multi-resistant and hydrolytic enterobacterial species. Lett Appl Microbiol (2007) 44(5):488–94. doi:10.1111/j.1472-765X.2007.02111.x

181. Cruz AT, Cazacu AC, Allen CH. Pantoea agglomerans, a plant pathogen causing human disease. J Clin Microbiol (2007) 45(6):1989–92. doi:10.1128/JCM.00632-07

182. Flores Popoca EO, Miranda Garcia M, Romero Figueroa S, Mendoza Medellin A, Sandoval Trujillo H, Silva Rojas HV, et al. Pantoea agglomerans in immunodeficient patients with different respiratory symptoms. ScientificWorldJournal (2012) 2012:156827. doi:10.1100/2012/156827

183. Liberto MC, Matera G, Puccio R, Lo Russo T, Colosimo E, Foca E. Six cases of sepsis caused by Pantoea agglomerans in a teaching hospital. New Microbiol (2009) 32(1):119–23.

184. Bicudo EL, Macedo VO, Carrara MA, Castro FF, Rage RI. Nosocomial outbreak of Pantoea agglomerans in a pediatric urgent care center. Braz J Infect Dis (2007) 11(2):281–4. doi:10.1590/S1413-86702007000200023

185. Boszczowski I, Nobrega de Almeida J Jr, Peixoto de Miranda EJ, Pinheiro Freire M, Guimaraes T, Chaves CE, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of Pantoea agglomerans bacteraemia associated with contaminated anticoagulant citrate dextrose solution: new name, old bug? J Hosp Infect (2012) 80(3):255–8. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2011.12.006

186. Chen KJ, Chen TH, Sue YM. Citrobacter youngae and Pantoea agglomerans peritonitis in a peritoneal dialysis patient. Perit Dial Int (2013) 33(3):336–7. doi:10.3747/pdi.2012.00151

187. Labianca L, Montanaro A, Turturro F, Calderaro C, Ferretti A. Osteomyelitis caused by Pantoea agglomerans in a closed fracture in a child. Orthopedics (2013) 36(2):e252–6. doi:10.3928/01477447-20130122-32

188. Moreiras-Plaza M, Blanco-Garcia R, Romero-Jung P, Feijoo-Pineiro D, Fernandez-Fernandez C, Ammari I. Pantoea agglomerans: the gardener’s peritonitis? Clin Nephrol (2009) 72(2):159–61. doi:10.5414/CNP72159

189. Marcos Sanchez F, Munoz Ruiz AI, Martin Barranco MJ, Viana Alonso A. [Bacteremia caused by Pantoea agglomerans]. An Med Interna (2006) 23(5):250–1.

190. Wong KW. Pantoea agglomerans as a rare cause of catheter-related infection in hemodialysis patients. J Vasc Access (2013) 14(3):306. doi:10.5301/jva.5000139

191. Rodrigues AL, Lima IK, Koury A Jr, de Sousa RM, Meguins LC. Pantoea agglomerans liver abscess in a resident of Brazilian Amazonia. Trop Gastroenterol (2009) 30(3):154–5.

192. De Baere T, Verhelst R, Labit C, Verschraegen G, Wauters G, Claeys G, et al. Bacteremic infection with Pantoea ananatis. J Clin Microbiol (2004) 42(9):4393–5. doi:10.1128/JCM.42.9.4393-4395.2004

193. Manoharan G, Lalitha P, Jeganathan LP, Dsilva SS, Prajna NV. Pantoea ananatis as a cause of corneal infiltrate after rice husk injury. J Clin Microbiol (2012) 50(6):2163–4. doi:10.1128/JCM.06743-11

194. Siala M, Gdoura R, Fourati H, Rihl M, Jaulhac B, Younes M, et al. Broad-range PCR, cloning and sequencing of the full 16S rRNA gene for detection of bacterial DNA in synovial fluid samples of Tunisian patients with reactive and undifferentiated arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther (2009) 11(4):R102. doi:10.1186/ar2748

195. De Maayer P, Chan WY, Rezzonico F, Buhlmann A, Venter SN, Blom J, et al. Complete genome sequence of clinical isolate Pantoea ananatis LMG 5342. J Bacteriol (2012) 194(6):1615–6. doi:10.1128/JB.06715-11

196. Yoshino Y, Kitazawa T, Kamimura M, Tatsuno K, Ota Y, Yotsuyanagi H. Pseudomonas putida bacteremia in adult patients: five case reports and a review of the literature. J Infect Chemother (2011) 17(2):278–82. doi:10.1007/s10156-010-0114-0

197. Trevino M, Moldes L, Hernandez M, Martinez-Lamas L, Garcia-Riestra C, Regueiro BJ. Nosocomial infection by VIM-2 metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas putida. J Med Microbiol (2010) 59(Pt 7):853–5. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.018036-0

198. Carpenter RJ, Hartzell JD, Forsberg JA, Babel BS, Ganesan A. Pseudomonas putida war wound infection in a US Marine: a case report and review of the literature. J Infect (2008) 56(4):234–40. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2008.01.004

199. Dervisoglu E, Dundar DO, Yegenaga I, Willke A. Peritonitis due to Pseudomonas putida in a patient receiving automated peritoneal dialysis. Infection (2008) 36(4):379–80. doi:10.1007/s15010-007-6349-8

200. Poirel L, Yakupogullari Y, Kizirgil A, Dogukan M, Nordmann P. VIM-5 metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas putida from Turkey. Int J Antimicrob Agents (2009) 33(3):287. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.07.018

201. Toru S, Maruyama T, Hori T, Gocho N, Kobayashi T. Pseudomonous putida meningitis in a healthy adult. J Neurol (2008) 255(10):1605–6. doi:10.1007/s00415-008-0987-3

202. Thomas BS, Okamoto K, Bankowski MJ, Seto TB. A lethal case of bacteremia due to soft tissue infection. Infect Dis Clin Prac (2013) 21(3):147–213. doi:10.1097/IPC.0b013e318276956b

203. Zuberbuhler B, Carifi G. Pseudomonas putida infection of the conjunctiva. Infection (2012) 40(5):579–80. doi:10.1007/s15010-012-0248-3

204. Almeida AC, Vilela MA, Cavalcanti FL, Martins WM, Morais MA Jr, Morais MM. First description of KPC-2-producing Pseudomonas putida in Brazil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2012) 56(4):2205–6. doi:10.1128/AAC.05268-11

205. Rokicka M. AmBisome treatment of fungal sinusitis in severe immunocompromised patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia relapsed after autologous peripheral blood transplantation. Acta Biomed (2006) 77(Suppl 2):26–7.

206. Ying-Cheng L, Chao-Kung L, Ko-Hua C, Wen-Ming H. Daytime orthokeratology associated with infectious keratitis by multiple gram-negative bacilli: Burkholderia cepacia, Pseudomonas putida, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Eye Contact Lens (2006) 32(1):19–20. doi:10.1097/01.icl.0000167714.53847.8c

207. Patzer JA, Walsh TR, Weeks J, Dzierzanowska D, Toleman MA. Emergence and persistence of integron structures harbouring VIM genes in the Children’s Memorial Health Institute, Warsaw, Poland, 1998-2006. J Antimicrob Chemother (2009) 63(2):269–73. doi:10.1093/jac/dkn512

208. Juan C, Zamorano L, Mena A, Alberti S, Perez JL, Oliver A. Metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas putida as a reservoir of multidrug resistance elements that can be transferred to successful Pseudomonas aeruginosa clones. J Antimicrob Chemother (2010) 65(3):474–8. doi:10.1093/jac/dkp491

209. Mendes RE, Castanheira M, Toleman MA, Sader HS, Jones RN, Walsh TR. Characterization of an integron carrying blaIMP-1 and a new aminoglycoside resistance gene, aac(6’)-31, and its dissemination among genetically unrelated clinical isolates in a Brazilian hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2007) 51(7):2611–4. doi:10.1128/AAC.00838-06

210. Shah SS, Kagen J, Lautenbach E, Bilker WB, Matro J, Dominguez TE, et al. Bloodstream infections after median sternotomy at a children’s hospital. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg (2007) 133(2):435–40. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.09.026

211. Rossolini GM, Luzzaro F, Migliavacca R, Mugnaioli C, Pini B, De Luca F, et al. First countrywide survey of acquired metallo-beta-lactamases in gram-negative pathogens in Italy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2008) 52(11):4023–9. doi:10.1128/AAC.00707-08

212. Lee K, Park AJ, Kim MY, Lee HJ, Cho JH, Kang JO, et al. Metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas spp. in Korea: high prevalence of isolates with VIM-2 type and emergence of isolates with IMP-1 type. Yonsei Med J (2009) 50(3):335–9. doi:10.3349/ymj.2009.50.3.335

213. Mitsuda Y, Takeshima Y, Mori T, Yanai T, Hayakawa A, Matsuo M. Utility of multiplex PCR in detecting the causative pathogens for pediatric febrile neutropenia. Kobe J Med Sci (2011) 57(2):E32–7.

214. Jacquier H, Carbonnelle E, Corvec S, Illiaquer M, Le Monnier A, Bille E, et al. Revisited distribution of nonfermenting Gram-negative bacilli clinical isolates. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis (2011) 30(12):1579–86. doi:10.1007/s10096-011-1263-5

215. Bogaerts P, Huang TD, Rodriguez-Villalobos H, Bauraing C, Deplano A, Struelens MJ, et al. Nosocomial infections caused by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas putida isolates producing VIM-2 and VIM-4 metallo-beta-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother (2008) 61(3):749–51. doi:10.1093/jac/dkm529

216. Carvalho-Assef AP, Gomes MZ, Silva AR, Werneck L, Rodrigues CA, Souza MJ, et al. IMP-16 in Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas stutzeri: potential reservoirs of multidrug resistance. J Med Microbiol (2010) 59(Pt 9):1130–1. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.020487-0

217. Almuzara M, Radice M, de Garate N, Kossman A, Cuirolo A, Santella G, et al. VIM-2-producing Pseudomonas putida, Buenos Aires. Emerg Infect Dis (2007) 13(4):668–9. doi:10.3201/eid1304.061083

218. Kim SE, Park SH, Park HB, Park KH, Kim SH, Jung SI, et al. Nosocomial Pseudomonas putida bacteremia: high rates of carbapenem resistance and mortality. Chonnam Med J (2012) 48(2):91–5. doi:10.4068/cmj.2012.48.2.91

219. Gilarranz R, Juan C, Castillo-Vera J, Chamizo FJ, Artiles F, Alamo I, et al. First detection in Europe of the metallo-beta-lactamase IMP-15 in clinical strains of Pseudomonas putida and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Microbiol Infect (2013) 19(9):E424–7. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12248

220. Oguz SS, Unlu S, Saygan S, Dilli D, Erdogan B, Dilmen U. Rapid control of an outbreak of Pseudomonas putida in a tertiary neonatal intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect (2010) 76(4):361–2. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2010.07.013

221. Souza Dias MB, Habert AB, Borrasca V, Stempliuk V, Ciolli A, Araujo MR, et al. Salvage of long-term central venous catheters during an outbreak of Pseudomonas putida and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections associated with contaminated heparin catheter-lock solution. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol (2008) 29(2):125–30. doi:10.1086/526440

222. Aumeran C, Paillard C, Robin F, Kanold J, Baud O, Bonnet R, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas putida outbreak associated with contaminated water outlets in an oncohaematology paediatric unit. J Hosp Infect (2007) 65(1):47–53. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2006.08.009

223. Liu Y, Liu K, Yu X, Li B, Cao B. Identification and control of a Pseudomonas spp (P. fulva and P. putida) bloodstream infection outbreak in a teaching hospital in Beijing, China. Int J Infect Dis (2014) 23:105–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2014.02.013

224. Carinder JE, Chua JD, Corales RB, Taege AJ, Procop GW. Rahnella aquatilis bacteremia in a patient with relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Scand J Infect Dis (2001) 33(6):471–3. doi:10.1080/00365540152029972

225. Erol S, Zenciroglu A, Dilli D, Okumus N, Aydin M, Gol N, et al. Evaluation of nosocomial blood stream infections caused by Pseudomonas species in newborns. Clin Lab (2014) 60(4):615–20. doi:10.7754/Clin.Lab.2013.130325

226. Caroff N, Chamoux C, Le Gallou F, Espaze E, Gavini F, Gautreau D, et al. Two epidemiologically related cases of Rahnella aquatilis bacteremia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis (1998) 17(5):349–52. doi:10.1007/s100960050080

227. Reina J, Lopez A. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of Rahnella aquatilis strains isolated from children. J Infect (1996) 33(2):135–7. doi:10.1016/S0163-4453(96)93138-2

228. Matsukura H, Katayama K, Kitano N, Kobayashi K, Kanegane C, Higuchi A, et al. Infective endocarditis caused by an unusual gram-negative rod, Rahnella aquatilis. Pediatr Cardiol (1996) 17(2):108–11. doi:10.1007/BF02505093

229. Funke G, Rosner H. Rahnella aquatilis bacteremia in an HIV-infected intravenous drug abuser. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis (1995) 22(3):293–6. doi:10.1016/0732-8893(95)00100-O

230. Maraki S, Samonis G, Marnelakis E, Tselentis Y. Surgical wound infection caused by Rahnella aquatilis. J Clin Microbiol (1994) 32(11):2706–8.

231. Hoppe JE, Herter M, Aleksic S, Klingebiel T, Niethammer D. Catheter-related Rahnella aquatilis bacteremia in a pediatric bone marrow transplant recipient. J Clin Microbiol (1993) 31(7):1911–2.

232. Alballaa SR, Qadri SM, al-Furayh O, al-Qatary K. Urinary tract infection due to Rahnella aquatilis in a renal transplant patient. J Clin Microbiol (1992) 30(11):2948–50.

233. Tash K. Rahnella aquatilis bacteremia from a suspected urinary source. J Clin Microbiol (2005) 43(5):2526–8. doi:10.1128/JCM.43.5.2526-2528.2005

234. Gaitan JI, Bronze MS. Infection caused by Rahnella aquatilis. Am J Med Sci (2010) 339(6):577–9. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181dd0cca

235. Chang CL, Jeong J, Shin JH, Lee EY, Son HC. Rahnella aquatilis sepsis in an immunocompetent adult. J Clin Microbiol (1999) 37(12):4161–2.

236. Bellais S, Poirel L, Fortineau N, Decousser JW, Nordmann P. Biochemical-genetic characterization of the chromosomally encoded extended-spectrum class A beta-lactamase from Rahnella aquatilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother (2001) 45(10):2965–8. doi:10.1128/AAC.45.10.2965-2968.2001

237. Goubau P, Van Aelst F, Verhaegen J, Boogaerts M. Septicaemia caused by Rahnella aquatilis in an immunocompromised patient. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis (1988) 7(5):697–9. doi:10.1007/BF01964261