95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mater. , 19 September 2023

Sec. Mechanics of Materials

Volume 10 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2023.1264709

This article is part of the Research Topic Recent Advances in the Identification of Stress-Strain States of Materials View all 5 articles

At present, in-situ monitoring of metal cracking and propagation is still a challenge. In this work, we used in-situ tensile tests with precast cracks of selective laser melting (SLM) and conventionally manufactured (CM) 316L stainless steels (SSs) to study crack propagation and strain-induced α′-martensite transformation. During in-situ tensile, cracks initiate at the concentration of slip lines at the precast crack, and the strong stress at the crack tip will tear apart the grain boundaries causing the crack to propagate until the samples are completely fractured. After in-situ tensile, abnormal grain growth was observed in the plastic zone at the crack tip of the SLMed 316L SS sample, while austenite to α′-martensite transformation was appeared at the grain boundaries of the SLMed 316L SS sample, and martensitic patches generated by severe plastic deformation induced in the CM 316L SS were also observed. The SLMed 316L SS shows higher strength and resistance to deformation than CM 316L SS. In addition, the stress concentration at the crack tip in crack propagation has a significant effect on the transformation of strain-induced α′-martensite.

Three-dimensional printing, also known as additive manufacturing (AM), is the process of producing a target three-dimensional object by building successive layers of material under the control of a computer program. Among the AM technologies, selective laser melting (SLM) is a significant technology that has attracted worldwide attention and played an important role in modern industry. Compared with traditional material manufacturing technologies, SLM has many advantages, such as high design freedom, rapid production, and high quality (Wang YM. et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2018). The 316L SSs occupy a vital position in society and industry due to their high strength, excellent corrosion resistance, and high oxidation resistance and are widely used in aerospace, medical devices, and nuclear plants (Almangour et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018; DL Zapata et al., 2019). Recently, several studies on SLM metals have shown that non-equilibrium treatments can spontaneously produce hierarchic metastable microstructures, resulting in higher yield strengths (Boegelein et al., 2015; Han et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). Furthermore, recent studies of SLMed 316L SS point out that it simultaneously enhances strength and ductility, compared with the CM 316L SS, and has significantly higher yield strength, which is mainly attributed to the microstructure refinement and high dislocation density (Griffith et al., 2000; Almangour et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020). Hong et al. reported that the SLM process greatly improved the yield strength but severely suppressed the stain-induced

Conventional 316L SS was annealed at 1,100°C for 1 h and quenched in water as a CM 316L SS. The corresponding chemical composition of the CM 316L SS is shown in Table 1. The initial material used for the SLM was 316L SS spherical powder with a particle size of 15–45 μm. The studied material was manufactured by EOSM290 and the corresponding chemical composition is shown in Table 1. Specifically, the scanning speed was 900 mm/s, the laser power was 275 W, the laser spot was 80 μm, and the shadow line spacing was 110 μm. The powder layer thickness was 40 μm. The layers were scanned in a sawtooth pattern, rotated 67° between each successive layer, and protected by high-purity argon gas. In this study, the characterization plane was perpendicular to the build direction.

The sample size specification in the in situ notched tensile tests in this study is shown in Figure 1. A notch (width × depth = 0.2 mm × 0.5 mm) was cut on the side of the pre-prepared tensile samples using an EDM wire cutter and then polished with 1,000–3,000 grit SiC sandpaper, followed by fine polishing with 9 mm, 3 mm, and 1 mm polishing solution. The polished samples were then electrolytically etched in 10% wt. Oxalic acid solution for 20 s. Finally, the samples were subjected to in situ notched tensile testing using an in situ tensile machine. Samples with precast cracks were stretched at a rate of 0.005 mm/s. The microstructure of the CM and SLMed 316L SSs were analyzed using an optical microscope and electron backscatter diffraction system (EBSD).

Figures 2A, C shows the optical microscopic images of the precast crack of CM 316L SS at 100× and 200×, respectively, while Figures 2B, D shows the optical microscopic images of the precast crack of SLMed 316L SS at the same magnifications after etching. The microstructure and grain boundary are clearly visible in the image. The CM 316L SS samples have larger grains, with sizes ranging from 50 to 70 μm, while the SLMed 316L SS samples have significantly smaller grains, with sizes ranging from 5 μm to 20 μm. The arrow in Figure 2C points to twin boundaries that are not present in the SLMed 316L SS, and the arrow in Figure 2D points to the unique print marks of SLMed 316L SS.

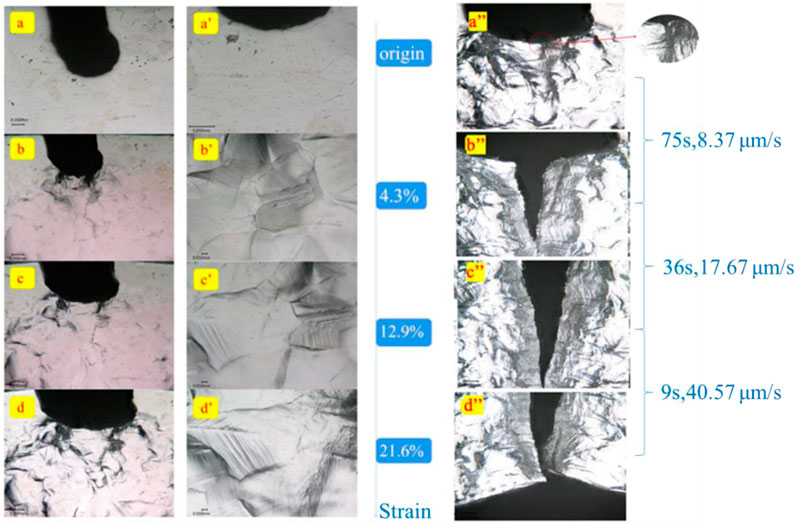

Figures 3a–d shows the in situ tensile of a CM 316L SS with a precast crack at a tensile rate of 0.005 mm/s and under a 250× light microscope. Under the continuous external stress field, the crack mouth gradually widened, and a cobweb-like deformation appeared near the crack. Figures 3a’–d’ shows the surface of the CM 316L SS near the precast crack under a 1,000× light microscope. Hilly undulations appeared on the original surface, there was an obvious aggregation and intersection of slip lines, and there were glide steps at the intersection of multiple slip lines. It is noteworthy that the deformation first appeared at the grain boundaries; with the increase in the external stress field, the deformation gradually spread to the inner part of the grain.

FIGURE 3. The in situ tensile observation of a CM 316L SS with a precast crack. (a–d). The observation of the sample at a tensile rate of 0.005 mm/s and under a 250× light microscope. (a’–d’) Light microscope images (1,000×) of the surface of the sample near the precast crack. (a”–d”) The process from crack initiation to complete fracture crack propagation of the sample.

Figure 3a”–d” shows the process from crack initiation to complete fracture crack propagation of the CM 316L SS, dozens of slip lines gathered near the lowest point of the precast crack, causing the stress concentration. The grain boundaries near the zone of stress concentration could not resist the continuous high stress because they had reached the deformation limit, and the crack initiation occurred. With the continuous change of the external stress field, the crack began to extend. The slip lines of the CM 316L SS at the tip of the crack further gathered and aggregate folds appeared near the crack, which were reflected as a gray field under the optical microscope.

The average crack propagation rate calculated by measuring the crack length was 31.35 μm/s. The crack propagation rate became larger as the crack grew, probably because at the beginning of the crack propagation CM 316L SS samples still retained most of the connections and there was some resistance to crack propagation. However, as the crack propagated, the connected part of the CM 316L SS samples reduced, resulting in a gradual decrease in the resistance to crack propagation; thus, the speed of crack propagation increased.

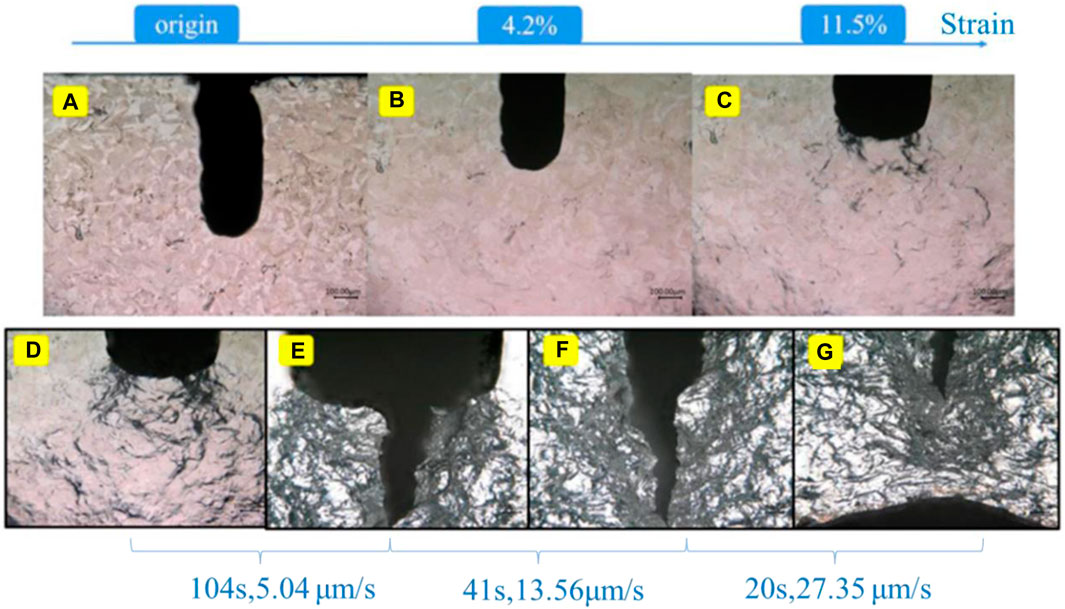

Figures 4A–C shows the SLMed 316L SS in situ tensile with displacement control at a tensile rate of 0.005 mm/s and Figures 4D–G shows the process from crack initiation to complete fracture crack propagation of the SLMed 316L SS. From the beginning of tensile to a strain of 4.2%, the surface of the SLMed 316L SS did not show obvious changes. When the strain reached 11.5%, cobweb-like deformation, hilly undulations, and an accumulation of slip lines appeared near the precast crack. The crack propagation process of CM and SLMed 316L SSs were similar. It was noteworthy that more gray field area appeared near the crack of SLMed 316L SS than with the CM 316L SS, which may be due to the difficulty in dislocation movement of the SLMed 316L SS, which led to more slip line generation and thus more folded gray field. The average crack propagation rate, calculated by measuring the crack length, was 15.45 μm/s. For the SLMed 316L SS, the crack propagation rate also increased as the cracks grew. However, the average crack propagation rate decreased by 50.7% compared with the CM 316L SS.

FIGURE 4. In situ tensile observation of a SLMed 316L SS with a precast crack. (A–C) Observation of the sample at a tensile rate of 0.005 mm/s. (D–G) The process from crack initiation to complete fracture crack propagation of the sample.

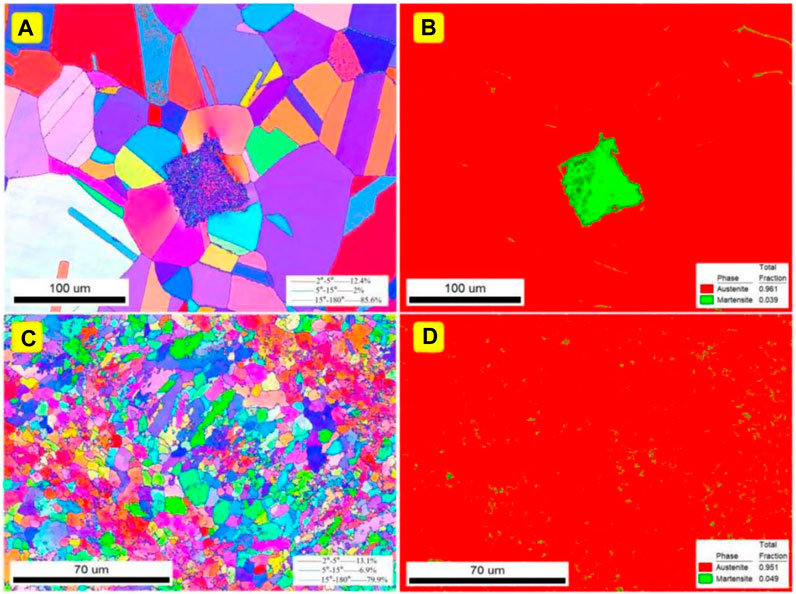

Figures 5A, B shows the EBSD results of the microstructures of CM 316L SS Figures 5A, B and SLMed 316L SS Figures 5C, D before in situ tensile. Through the inverse-pole figure, the grain size of CM 316L SS was larger, in the range of 50–70 μm, while the grain size of SLMed 316L SS was significantly smaller, in the range of 5–20 μm. In the phase diagrams of both samples before in situ tensile, a single austenitic phase was observed.

FIGURE 5. The EBSD results before in situ tensile of the microstructures of the (A,B) CM and (C,D) SLMed 316L SSs.

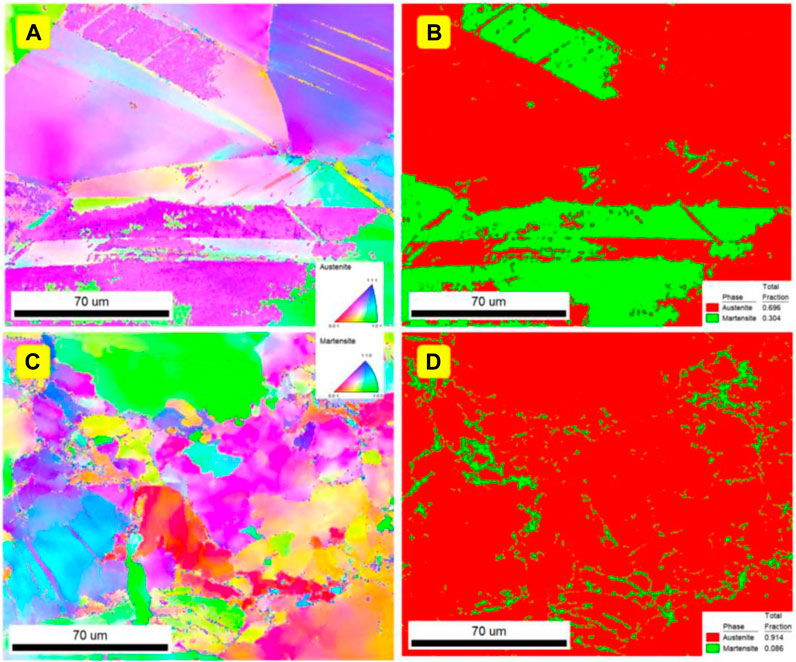

Figure 6 shows the EBSD results of the microstructures near the cracks of CM 316L SS (Figures 6A, B) and SLMed 316L SS (Figures 6C, D) after in situ tensile. Grain size growth was observed in both process samples and compared with the results obtained before in situ tensile. After tensile tests, CM 316L SS grains were between 60 μm and 80 μm, while SLMed 316L SS grains were between 30 μm and 50 μm. For SLMed 316L SS, which has small grains, such obvious grain changes are not simply due to grain deformation but may be caused by the dynamic recrystallization resulting from the intense plastic deformation in the plastic zone at the crack tip during the rapid crack extension process, which induces the abnormal growth of the grains near the crack tip during the crack extension process of SLMed 316L SS.

FIGURE 6. The EBSD results after in situ tensile of microstructures of the (A,B) CM and (C,D) SLMed 316L SSs.

From the phase diagram, a large amount (30.4%) of α’-martensite appeared in CM 316L SS due to the strain-induced martensitic transformation, while a small amount (8.6%) of α’-martensite also appeared in SLMed 316L SS.

A comparison of the propagation of precast cracks in CM and SLMed 316L SSs revealed that the surface of the samples with high elongation in CM changed significantly during the tensile, with cobweb-like patterns and hilly undulations appearing earlier, and the change in the precast crack notch was also greater. For the CM 316L SS, the precast crack was already significantly propagated when the strain reached 21.5%. For the SLM sample, the surface did not change significantly at the beginning of the tensile. Because of the rapid solidification (unbalanced cooling) experienced, a high density of low angle grain boundaries occurs in SLMed 316L SS, which form upon the coalescence of cells or dendrites that accumulate misorientation as they grow (Napolitano and Schaefer, 2000; Newell et al., 2005; Manvatkar et al., 2015; Wang Y. M. et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2020). Owing to the high-density low-angle grain boundaries and fine cellular microstructures, the slip of the dislocation is restricted. When the strain reached 11.5%, only obvious deformation marks appeared.

These test results indicate that SLMed 316L SS has higher strength and resistance to deformation than CM 316L SS. In addition, the nucleation of microcracks is preceded by the emission, multiplication, and movement of dislocations. In SLMed 316L SS, because of cellular structures and the presence of precipitates, high-density lower-angle grain boundaries and stacking faults can strengthen the cell walls; therefore, the movement of dislocations was restricted, thus the formation of the plastic deformation zone at the crack tip is slower. Therefore, the SLM sample had a lower crack propagation rate than CM 316L SS.

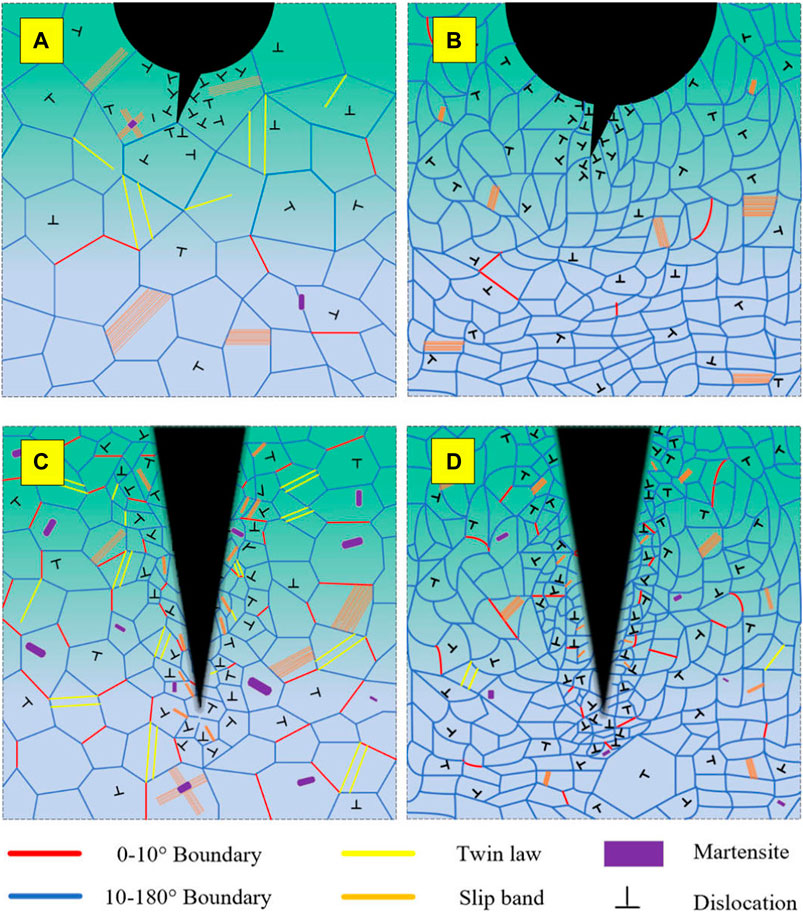

Figure 7 shows a schematic illustration of the crack initiation and propagation for the two samples. As shown in Figures 7A, C, before tensile there were some twinning boundaries in CM 316L SS, and when the deformation occurred, α′-martensite mainly nucleated and grew at the intersections of shear bands and partly along the boundaries, which caused a large amount of α′-martensite in CM 316L SS after tensile. In addition, in Figures 7B, D, owing to the high density of low-angle grain boundaries in SLM 316L stainless steel, the nucleation sites of strain-induced α’-martensite were significantly reduced, which restricted the formation of α’-martensite (only 8.6% after tensile). However, a small amount of deformation twins was formed after tensile. The SLMed 316L sample contains fine cellular structures and a high density of dislocations, and these structures could restrict the formation and growth of deformation twins. A large stress concentration is induced at the crack tip during crack propagation, resulting in a large plastic deformation at the crack tip. This also promotes the appearance of a small amount of deformation twins, so the formation of α’-martensite was inhibited.

FIGURE 7. Schematic illustration of crack initiation and propagation for (A,B) CM and (C,D) SLMed 316L SSs.

When comparing the microstructure of the non-crack samples after tensile (not show here), it was observed that almost no strain-induced α’-martensite appeared in the SLM non-crack sample after tensile and fracture, while for CM 316L SS, the strain-induced α’-martensite in the non-crack sample was much less than that in the precast crack sample. This indicates that the stress concentration at the crack tip in crack propagation has a significant effect on the transformation of strain-induced α′-martensite in the samples.

In summary, crack propagation and strain-induced α′-martensite transformation of SLM and CM 316L SSs were studied in detail through in situ tensile tests with a precast crack. SLM 316L SS had a lower crack propagation rate than CM 316L SS. Furthermore, the stress concentration at the crack tip in crack propagation has a significant effect on the transformation of strain-induced α′-martensite in the samples. This study provides a new direction for the study of SLM 316L stainless steel.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

TZ: Writing–original draft. MG: Writing–review and editing. ZZ: Writing–review and editing. JL: Writing–original draft. SZ: Writing–original draft.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFE0205300) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A20128). This study was also supported by the Chengdu Xianhe Semiconductor Technology Co., Ltd., China (45000-71020047) and the Chengdu Rihe Xianrui Technology Co., Ltd., China (45000-71020048). These funders was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Almangour, B., Grzesiak, D., and Yang, J. M. (2017). In-situ formation of novel TiC-particle-reinforced 316L stainless steel bulk-form composites by selective laser melting. J. Alloys Compd. 706, 409–418. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.01.149

Boegelein, T., Dryepondt, S. N., Pandey, A., Dawson, K., and Tatlock, G. J. (2015). Mechanical response and deformation mechanisms of ferritic oxide dispersion strengthened steel structures produced by selective laser melting. Acta Mater. 87, 201–215. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2014.12.047

Brenne, F., and Niendorf, T. (2019). Damage tolerant design by microstructural gradation – influence of processing parameters and build orientation on crack growth within additively processed 316L. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 764, 138186. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2019.138186

Dl Zapata, K. Saeidi., Lofaj, F., Kvetkova, L., Olsen, J., Shen, Z. J., et al. (2019). Ultra-high strength martensitic 420 stainless steel with high ductility. Addit. Manuf. 29, 100803. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2019.100803

FerganiWoldBerto, O. A. B. F., Brotan, V., and Bambach, M. (2018). Study of the effect of heat treatment on fatigue crack growth behaviour of 316L stainless steel produced by selective laser melting. Fatigue & Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 41 (5), 1102–1119. doi:10.1111/ffe.12755

Gao, S. B., Hu, Z. H., Duchamp, M., Sankara Rama Krishnan, P. S., Tekumalla, S., Song, X., et al. (2020). Recrystallization-based grain boundary engineering of 316L stainless steel produced via selective laser melting. Acta Mater. 200, 366–377. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2020.09.015

Griffith, M. L., Ensz, M. T., Puskar, J. D., Brooks, J. A., Philliber, J. A., Smugeresky, J. E., et al. (2000). Understanding the microstructure and properties of components fabricated by laser engineered net shaping (LENS). MRS Online Proceeding Libr. Arch. 625. doi:10.1557/PROC-625-9

Han, Y. D., Zhang, Y. K., Jing, H. Y., Lin, D. Y., Zhao, L., Xu, L. Y., et al. (2020). Selective laser melting of low-content graphene nanoplatelets reinforced 316l austenitic stainless steel matrix: strength enhancement without affecting ductility. Addit. Manuf. 34, 101381. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2020.101381

He, F., Wang, C., Han, B., Yeli, G. M., Wang, Z. J., Wang, L. L., et al. (2022). Deformation faulting and dislocation-cell refinement in a selective laser melted 316L stainless steel. Int. J. Plasticity 56, 103346. doi:10.1016/j.ijplas.2022.103346

Hong, Y. J., Zhou, C. S., Zheng, Y. Y., Zhang, L., Zheng, J. Y., Chen, X. Y., et al. (2019). Formation of strain-induced martensite in selective laser melting austenitic stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 740-741 (7), 420–426. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2018.10.121

Kang, N., Ma, W. Y., Heraud, L., Mansori, M. E., Li, F. H., Liu, M., et al. (2018). Selective laser melting of tungsten carbide reinforced maraging steel composite. Addit. Manuf. 22, 104–110. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2018.04.031

Li, Z., Cui, Y., Yan, W. T., Zhang, D., Fang, Y., Chen, Y. J., et al. (2021). Enhanced strengthening and hardening via self-stabilized dislocation network in additively manufactured metals. Mater. Today 50, 79–88. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2021.06.002

Liu, L. F., Ding, Q. Q., Zhong, Y., Zou, J., Wu, J., Chiu, Y. L., et al. (2018). Dislocation network in additive manufactured steel breaks strength–ductility trade-off. Mater. Today 21 (4), 354–361. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2017.11.004

Manvatkar, V., De, A., and DebRoy, T. (2015). Spatial variation of melt pool geometry, peak temperature and solidification parameters during laser assisted additive manufacturing process. Mater. Sci. Technol. 31 (8), 924–930. doi:10.1179/1743284714Y.0000000701

Napolitano, R. E., and Schaefer, R. J. (2000). The convergence-fault mechanism for low-angle boundary formation in single-crystal castings. J. Mater Sci. 35 (7), 1641–1659. doi:10.1023/A:1004747612160

Newell, M., Devendra, K., Jennings, P. A., and D’Souza, N. (2005). Role of dendrite branching and growth kinetics in the formation of low angle boundaries in Ni–base superalloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 412 (1), 307–315. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2005.09.030

RiemerLeudersThöNe, A. S. M., Richard, H., Tröster, T., and Niendorf, T. (2014). On the fatigue crack growth behavior in 316L stainless steel manufactured by selective laser melting. Eng. Fract. Mech. 120, 15–25. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2014.03.008

Sun, Z. J., Tan, X. P., Tor, S. B., and Chua, C. K. (2018). Simultaneously enhanced strength and ductility for 3D-printed stainless steel 316L by selective laser melting. NPG Asia Mater. 10, 127–136. doi:10.1038/s41427-018-0018-5

SuryawanshiPrashanthRamamurty, J. K. G. U. (2017). Mechanical behavior of selective laser melted 316L stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 696, 113–121. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2017.04.058

Wang, Y. M., Voisin, T., McKeown, J. T., Ye, J. C., Calta, N. P., Li, Z., et al. (2018a). Additively manufactured hierarchical stainless steels with high strength and ductility. Nat. Mater. 17 (1), 63–71. doi:10.1038/nmat5021

Wang, Y. M., Voisin, T., McKeown, J. T., Ye, J., Calta, N. P., Li, Z., et al. (2018b). Additively manufactured hierarchical stainless steels with high strength and ductility. Nat. Mater 17 (1), 63–71. doi:10.1038/nmat5021

Wang, Z. Q., Palmer, T. A., and Beese, A. M. (2020). Effect of processing parameters on microstructure and tensile properties of austenitic stainless steel 304L made by directed energy deposition additive manufacturing. Acta Mater. 110, 226–235. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2016.03.019

Keywords: in-situ tensile, crack propagation, 316L stainless steel, selective laser melting, martensite

Citation: Tan Z, Gui M, Zhou Z, Lv J, Zhang S and Wang Z (2023) Crack propagation and strain-induced α’-martensite transformation in selective laser melting 316L stainless steels. Front. Mater. 10:1264709. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2023.1264709

Received: 21 July 2023; Accepted: 28 August 2023;

Published: 19 September 2023.

Edited by:

Vincent Ji, Université Paris-Saclay, FranceReviewed by:

Lakshmi Narayan Ramasubramanian, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, IndiaCopyright © 2023 Tan, Gui, Zhou, Lv, Zhang and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinlong Lv, bGpsdHNpbmdodWFAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Shuye Zhang, c3l6aGFuZ0BoaXQuZWR1LmNu; Zhuqing Wang, d3podXFpbmdAc2N1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.