94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mater., 24 February 2021

Sec. Polymeric and Composite Materials

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2021.643428

This article is part of the Research TopicAntimicrobial Nanostructured Polymeric Materials and NanocompositesView all 7 articles

In this study, nanofibers with different ratios of poly(vinyl alcohol) and chitosan incorporated with moxifloxacin hydrochloride (MH/PVA/CS) were fabricated through the blending electrospinning, and the morphological features were tested using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Further characterization of the new nanofiber was accomplished by Thermogravimetric analysis (TG), X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). Antibacterial activity of the MH-loaded nanofibers at different drug loading were tested and compared with the blank group. Experimental results show that the MH/PVA/CS nanofibers exhibited the good antibacterial properties against Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa due to the MH incorporation. Compared with blank nanofibers, MH/PVA/CS nanofibers have significantly better antibacterial properties, and different proportions of PVA and CS have a certain effect on the antibacterial activity of nanofibers. The conclusions in this paper show that MH/PVA/CS composite nanofibers may have great potential in antibacterial materials.

Medical treatment often faces the dilemma of bacterial infection, which delay the cure or even worsen the disease (Fisher et al., 2017). The development of antibacterial nanomaterials has effectively solved this problem, and related studies (Sonkusare et al., 2018; Chouke et al., 2019) have shown that it also has positive effects in inhibit bacterial reproduction, reduce inflammation, wound healing and disease treatment. The current nanomaterials are mainly nanotubes, nanowalls and nanofibers (Zhao et al., 2007; Kakunuri et al., 2017; Han et al., 2019). And the antibacterial nanofibers were widely used in various fields due to high porosity and small pore size (Dinis et al., 2015), especially in tissue engineering, drug delivery and wound dressings of biomedical applications (Lee et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2017).

Electrospinning is a simple and cost-effective method to fabricate nanofibers with diameters ranging from dozens of nanometers to several microns (Luo et al., 2012; Mishra et al., 2019). Chitosan (CS) is a product of natural polysaccharide chitin with acetyl groups removed, and it has a variety of physiological functions including the biodegradability, biocompatibility, non-toxicity and antibacterial ability (Berger et al., 2004; Qin et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020). Therefore, electrospun nanofibers with chitosan have unique advantages in biomedical applications since they mimic the natural extracellular matrix (ECM) as a structure to support and regulate cell behavior (Balagangadharan et al., 2017; Xue et al., 2020). However, CS is a cationic polyelectrolyte that makes it positively charged when only dissolved in solution, which leads to poor electrospinning properties (Arkan et al., 2018). Repulsive interactions between like-charged groups destroy Taylor cone, thus making it difficult for the fiber to form when electrospinning (Sun et al., 2019). Researchers have used different methods to improve the electrospinability of CS. Schiffman et al. used trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) to dissolve chitosan for one-step electrospinning (Schiffman and Schauer, 2007). Anionic polyelectrolyte has been utilized to neutralize cations in chitosan solution, like hyaluronic acid (Ma et al., 2012; Sun et al., 2019). Some researchers also attempted to mixing CS with other polymers with good electrospinability, such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polylactide co-glycolide (PLGA) (Huang et al., 2020), polyethylene oxide (PEO) (Yuan et al., 2016). However, utilization of toxic solvents is not optimal, especially in biomedical applications. As a non-toxic, hydrophilic and biocompatible synthetic polymer, PVA has been used in various biomedical fields (Kamoun et al., 2017). Related studies have reported some examples of nanofibers prepared by electrospinning with PVA and chitosan (Duru Kamaci and Peksel, 2020; Menazea and Ahmed, 2020), and the PVA aqueous solution also eliminates possible organic solvent residues and environmental hazards. Accordingly, the materials composed of PVA and CS is nontoxic, biocompatible and easy to adjust for antibacterial materials.

The application of PVA/CS in antibacterial materials has been studied by researchers (Zhang et al., 2017; Duru Kamaci and Peksel, 2020). However, the antibacterial effect of adding moxifloxacin to electrospun nanofibers prepared from PVA/CS has not been focused on. Moxifloxacin as an example of antibiotic with intrinsic antibacterial activity, have been widely used for respiratory infections, community-acquired pneumonia, skin and soft-tissue infections (Fu et al., 2016; Wan et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2020). It is a broad-spectrum antibiotic and widely used in the research of composite materials(Gong et al., 2019; Wan et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2021), which has strong antibacterial properties and few adverse reactions (Hameed et al., 2020). Therefore, the drug loading and antibacterial activity of moxifloxacin in electrospun nanofibers with different PVA/CS ratios were analyzed in this paper.

In the present work, MH/chitosan/PVA fibers were prepared by hybrid electrospinning, and the properties of PVA and CS-based composite nanofibers in different ratios were investigated. The morphology of electrospun fibers were characterized by Scanning electron microscope (SEM). The solid-state characterization was analyzed by X-ray Diffraction (XRD), thermal gravimetric analysis (TG), and attenuated total reflectance infrared spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR). In addition, the mechanical properties of electrospun fibers were measured by tensile tests, and the encapsulation efficiency and in vitro antibacterial properties were evaluated. Finally, the application prospects of the new MH/chitosan/PVA fiber were discussed.

PVA(polymerization degree = 1700, alcoholysis degree = 88%) were purchased from Qingdao Pansi Technology Co., Ltd. Powdered chitosan(the deacetylation degree was 80%–95%) and acetic acid (analysis reagent) was obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Lrd. Moxifloxacin hydrochloride (the purity was 98%) were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. The solvents of all solutions are deionized water. All chemicals and solvents were used without further purification.

CS was dissolved in aqueous acetic acid (1% w/w) to obtain clear and homogenous solutions with a concentration of 2.0% w/w. The PVA solution was prepared by dissolving 10 g of PVA in 90 ml deionized water with a concentration of 10% w/w. Blending solutions containing different volume rations (9:1, 8:2, 7:3, 6:4) of 10% PVA and 2% CS were prepared. Then the MH was dissolved in the mixing solution with 36 mg per 10 ml. Each solution was stirred to complete dissolution to ensure all ingredients are dispersed completely.

All prepared solution was placed in a 10 ml plastic syringe separately which were then fixed on a syringe pump (TYD01-01, Lead Fluid Technology Co., Ltd, China). The feeding rate was 0.3 ml/h, and a voltage of 10 kV was applied to the needle. The distance between the needle and the collector was 10 cm. Nanofibers were collected on electrically grounded Al foil, which covered a roller collector placed 10 cm away. The prepared nanofibers were dried in vacuum at 60°C for 24 h to remove the residual solvents.

The surface morphologies of the electrospun fibers were observed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (SU8220, Hitachi, Japan). The diameter distribution of electrospun nanofibers was collected by ImageJ software. The Fourier-transform infrared spectra of the electrospun nanofibers, PVA and chitosan powder were obtained on a Nicolet 8700 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet ltd., United States) to analyze functional groups. Samples were analyzed at operating wavelengths in the range between 4,000 and 400 cm−1. An X’Pert Pro diffractometer (PA Nalytical B.V., Netherlands) was used in the experiment to detect the formation of electrospun nanofibers with the testing condition: Cu-Kα radiation, 40 kV, 2θ range of 5–65°. Thermal gravimetric analysis was collected by using TG 209F1 (NETZSCH-Gerätebau Gmbh, Germany). Electrospun nanofibers were heated from 30°C to 600°C with a heating rate of 10°K/min. The whole process was under nitrogen atmosphere.

Tensile test was carried out by using TMA Q400 (TA Instruments, United States). Before measurements, specimens of each nanofiber were chosen for the tensile test and cut into rectangular pieces with 9 mm length and 8 mm width. The tensile stress-strain curves of each samples were measured precisely.

The drug-loaded nanofiber samples (10 mg) were immersed in 50 ml aqueous acetic acid (1%) precisely to get clear solutions. The concentration with MH in the solution was characterized using a LC-20A high-performance liquid chromatography (SHIMADZU Co., Ltd Japan). Analyses were performed on a Shim-pack VP-ODS (5°μm, 4.6 × 250 mm) at a temperature of 30°C. Methanol/1% triethylamine (45:55, v/v; pH = 3.0) was used as the mobile phase[8]. The effluent was quantified at 280 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer. The encapsulation efficiency of MH loading was calculated by the following equations:

ME = encapsulation efficiency, MA = actual concentration of MH characterized by HPLC, and MT = theoretical concentration of MH calculated from drug/nanofiber ration.

The antibacterial activity of electrospun nanofibers was tested using Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cultures of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa with concentration of 106 CFU/ml were prepared on nutrient agar plates. The samples for the test were prepared by chipping electrospun nanofibers with a mass of 0.001 g to a diameter of 6 mm. PVA/CS nanofiber (PVA:CS = 9:1) was regarded as a control group. Various ratios of PVA/CS nanofibers with MH were kept in plates cultured S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, separately. All plates were incubated for 16 h at 37°C in an incubator. The diameters of the antibacterial zones were measured with a vernier caliper and recorded.

In the preparation of MH-loaded electrospun nanofibers, PVA was blended with CS due to the rigid chemical nature and bad electrospinability of CS. In the process of nanofibers preparation, it is obvious that the addition of PVA enhances the electrospinning property. Besides, the previous study of Hang et al. indicated that the concentration and conductivity of the prepared solution before electrospinning are key factors which effect the morphological characteristics of electrospun nanofibers (Hang et al., 2010).

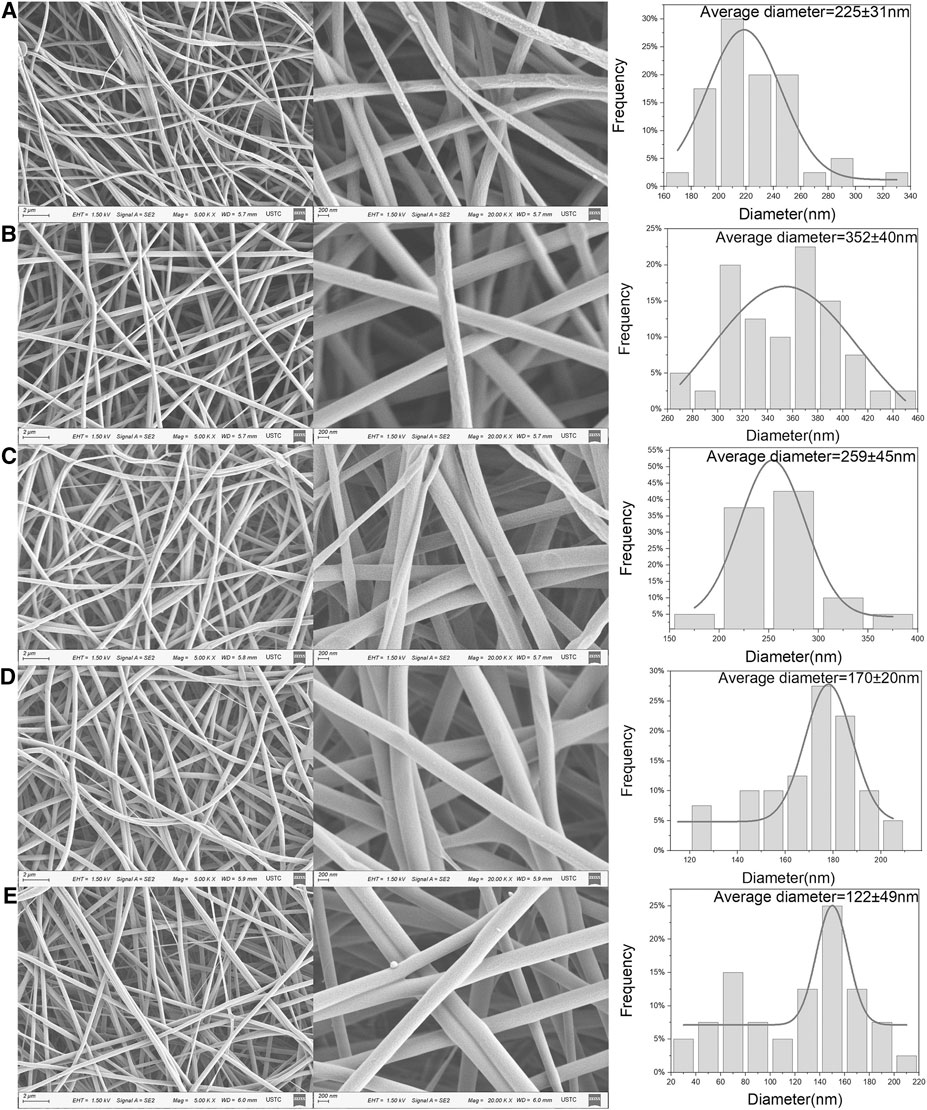

Figure 1 shows the effect of different ratios of PVA and CS on the morphology of nanofibers. It is obvious that the electrospun nanofibers were beadless, continuous and randomly distributed. By comparing Figures 1A,B, it can be seen that the loading of antibiotics resulted in a significant increase in the average nanofiber diameter, morphological changes and an increased random of alignment, which is in good agreement with the conclusions of Karuppuswamy et al. (Karuppuswamy et al., 2015). Among drug loaded samples, the average diameter of nanofibers decreased with the increase of chitosan content. Similar conclusion has been found in previous studies about PVA/CS electrospinning (Hang et al., 2010; Koosha and Mirzadeh, 2015). The presence of CS in the solution increases the surface charge concentration of the jet. More surface charge causes more repulsion on the surface, resulting in the size reduction of electrospun nanofibers. With the addition of CS, the nanofiber diameters were changed from 352 ± 40 nm to 122 ± 49 nm. Different content of chitosan affected the diameter of nanofiber, which indirectly led to the different drug content of the nanofibers. the specific effect was discussed in the Section Drug content and encapsulation efficiency. In addition, it can be seen that the distribution of pore size is uniform, and there is no obvious change among the groups from the results of SEM. The pore size of the nanofibers was observed more than 50 nm, so the nature of the sample is macroporous according to IUPAC nomenclature.

FIGURE 1. FE-SEM micrographs, average diameter and diameter distribution of PVA/CS 9/1 nanofiber (A), MH/PVA/CS nanofiber with different PVA to CS rations: (B) 9/1, (C) 8/2, (D) 7/3, (E) 6/4.

The FTIR spectra of the MH, PVA, CS, PVA/CS fibers and MH/PVA/CS fibers are showed in Figure 2. The characteristic peaks of MH were assigned as follows: 3,524 cm−1 (stretching vibration of O-H groups) (Tanna et al., 2016), 3,435 cm−1 (stretching vibration of N-H groups), 1,709 cm−1 (stretching vibration of C-O groups), 1,623 cm−1 (skeleton vibration of C-O groups), 1,455 cm−1 (skeleton vibration of C-C groups), 1,354 and 1,323 cm−1 (stretching vibration of C-F groups). Most of peaks disappeared in the electrospun nanofibers indicates interaction between MH and carrier materials (Fu et al., 2016). The absorption peak of 1,620 cm−1 was visible in the drug loaded fiber but not in the blank fiber, suggesting the successful incorporation of MH. The similarity of the pure PVA, CS and electrospun nanofibers spectra demonstrated that the process of electrospinning didn’t change the chemical structure of PVA and CS (Li et al., 2020).

To analysis the crystallinities of pure PVA, CS, MH and electrospun nanofibers, XRD was carried out and exhibited in Figure 3. From the spectra of the PVA before electrospinning, crystalline peaks were seen at 2θ of 11.41°, 19.26°. A strong absorption peak at 2θ = 20.32° of CS was characterized [JCPDS File No. 35-1974] (Karthikeyan et al., 2019), indicating a typical semi-crystalline polymer. The spectrum of MH powder featured crystalline peaks at 14.41°, 15.57°, 16.95°, 17.37°, 19.06°, 19.63°, 20.37°, 23.61°, 24.07°, 24.47°, 26.71°, 27.49°, 29.17°, 31.61°, 35.13°, 38.67° (Hameed et al., 2020). However, the absorption peaks of PVA and CS diminished in spectra of PVA/CS electrospun nanofiber, demonstrating that the inter and intramolecular hydrogen bonding between PVA and CS were formed during electrospinning (Zhang et al., 2017). The spectra of drug loaded electrospun nanofiber didn’t show any characteristic peaks similarly, indicating the MH had been wrapped up. The results suggested that the electrospinning process leads the materials to become amorphous.

The TG curves of different P/C electrospun nanofibers were exhibited in Figure 4. Two regions of weight loss were showed. The weight loss around 300°C reflected to the breakage of side chain of PVA. Up to 400°C, the mass changes were −76.44%, −72.07%, −70.47% and −68.11% from P/C 9/1 to P/C 6/4, respectively. With the increase of chitosan content, the mass left increased after the thermal decomposition. The weight loss process of samples is mainly due to the thermal degradation of PVA and CS. According to previous studies (Fu et al., 2016; Chaudhary et al., 2019; Hameed et al., 2020), the degradation temperature of PVA and CS was similar before 370°C, and the quality loss after 370°C is mainly caused by CS. TG results indicated that the thermal stability of electrospun nanofibers was improved by the addition of the CS.

The temperatures at the peaks of DTG curves corresponding to the maximum weight loss rate were 313.74°C, 322.07°C, 321.52°C, 324.80°C for P/C 9/1, P/C 8/2, P/C 7/3, P/C 6/4 electrospun nanofiber, separately. The increase of temperature resulted in the linkages between PVA chains and CS chains.

The tensile strength is the resistance to the maximum uniform deformation of the material. The deformation of the sample is uniform before the maximum tensile stress, but the necking phenomenon of the material begins to appear after exceeding the maximum tensile stress. Young’s modulus is the ratio of stress to strain within the elastic limit of the material, which is used to characterize mechanical property. The mechanical properties of the electrospun nanofibers were investigated by the tensile stress-strain testing method and showed by Figure 5. CS is a kind of linear polysaccharide with positive charge. Due to strong hydrogen bond between the molecules, CS is brittle and rigid. In the electrospinning process of PVA, the hydrogen bond association formed by hydroxyl side groups between chains can form winding structure. Therefore, increasing the PVA content and decreasing the CS ratio of electrospun nanofiber were expected to increase the flexibility but decrease the strength of the blended electrospun nanofiber.

The Young’s modulus was increased by incorporation of CS. Maximum Young’s modulus reached 189.6 ± 1.3 MPa, which is shown in PVA/CS 7/3 nanofiber. Excessive addition of CS could not produce further enhancement. As shown in Table 1, Young’s modulus start falling down with the ratio of PVA and CS from 7/3 to 6/4. The respective tensile strength of the electrospun nanofiber increased from 5.07 to 5.67 MPa with increasing PVA concentrations. PVA/CS 9/1 nanofiber had a higher tensile strength and strain at break compared to samples with higher proportion of CS.

The encapsulation efficiency of MH from the electrospun nanofibers was studied (Table 2). With the increase of CS content, the encapsulation efficiency of different groups was 83.02%, 95.38%, 87.40% and 93.04%, respectively. The high encapsulation efficiency is due to the high solubility of MH in solution. The MH were directly mixed into the electrospinning solution, the solubility and ionization state of the drug led to the increase of drug loading and release. The initial burst release is required in some specific cases (Amiri et al., 2020). The result of SEM showed that no drug was found on the surface of the electrospun nanofiber. It can be inferred that the drug was completely encapsulated in PVA/CS nanofiber.

MH is a broad-spectrum antibiotic that includes Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. In this work, S. aureus and P. aeruginosa were employed to investigate the antibacterial activity of electrospun nanofibers. Table 3 listed every size of zone of inhibition. Chitosan has some antibacterial effect, which can accelerate wound healing. Researchers have found that positively charged chitosan molecules can bind to negatively charged microbial cell membranes (Mahmoudi et al., 2011). Cell membrane is destroyed to achieve antibacterial effect. Besides, it provides anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and hemostatic effects (Kim, 2018). Therefore, the blank PVA/CS nanofiber were characterized for antibacterial activity. However, zone of inhibition didn’t show in the blank PVA/CS nanofiber by Figure 6A. The reason is that CS could not diffuse in agar diffusion method, which is similar with a previous research (Amiri et al., 2020). In other related research, the antibacterial property of chitosan was tested by vibration method (Hameed et al., 2020).

FIGURE 6. Inhibition zones of different nanofibers against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. PVA/CS 9/1 nanofiber (A), MH/PVA/CS nanofiber with different PVA to CS rations: (B) 9/1, (C) 8/2, (D) 7/3, (E) 6/4

The activity of antibiotic after incorporation is significant factor for antibacterial materials. Due to the higher surface area to volume ratio of nanofibers, the affinity for bacteria is increased and leads to greater antibacterial activity (Amiri et al., 2020). Figures 6B–E shows the antibacterial activity studies of the drug loaded PVA/CS nanofibers against S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. Compared to blank PVA/CS nanofiber, drug loaded nanofibers exhibited obvious zone of inhibition, which showed good performance of MH. There is no significant difference among each sample, which was related to the release of MH and diffusion in the agar. According to the text of drug content, different nanofibers contained different amount of MH. Different diameters of each samples might affect the amount of MH in contact with bacteria. The results showed that the addition of MH enhanced the antibacterial activity of the PVA/CS electrospun nanofiber, and the change of proportion had no obvious effect on the antibacterial activity.

The mechanism of antibacterial activity can be explained as follows. The MH released from the nanofibers induces production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Wan et al., 2020). ROS are strong oxidants with strong oxidative ability, which destroys antioxidant defense and leads to protein and lipid damage (Bagade et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020). Rupture of membrane results in cell injury or death. These results indicated that moxifloxacin loaded nanofibers could be a great carrier for antibiotic delivery especially to the wound dressing. In the next work, we will focus on the model of drug release from MH/PVA/CS nanofibers and the performance in animal experiments.

Composite MH-loaded nanofibers of different formulation consisting of PVA/CS and MH/PVA/CS were successfully fabricated by the blending electrospinning method. PVA had good electrospinnability and was dissolved with CS, which cannot be electrospun alone. The incorporation of MH and crystallinity were investigated via XRD, FTIR and TG. The results indicated the MH was loaded on the nanofibers and formed hydrogen bonding with PVA and CS. And the CS in the PVA/CS nanofibers resulted in a reduction in the diameter and an increase in the Young’s Modulus, the encapsulation efficiency reached 95.38% with the nanofiber of PVA/CS 8/2. Furthermore, the antibacterial experiment indicated that the MH/PVA/CS nanofibers had good antibacterial activity against strains of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conceptualization, QL, W-CO, TJ and Z-WW.; methodology, QL, W-CO, TJ and Z-WW.; software, QL; validation, QL and X-HZ and Z-WW; formal analysis, QL and X-HZ.; investigation QL; resources, QL, W-CO, TJ, X-HZ and Z-WW; data curation, QL, W-CO and XZ; writing—original draft preparation, QL, W-CO, TJ; writing—review and editing, QL, W-CO and Z-WW; visualization, QL, W-CO, and Z-WW; supervision, Z-WW; project administration, Z-WW.; funding acquisition, Z-WW. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by the Key Research and Development Plan of Anhui Province under Grant 201904a07020013.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and editors for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of this paper.

Amiri, N., Ajami, S., Shahroodi, A., Jannatabadi, N., Amiri Darban, S., Fazly Bazzaz, B. S., et al. (2020). Teicoplanin-loaded chitosan-PEO nanofibers for local antibiotic delivery and wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 162, 645–656. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.06.195

Arkan, E., Azandaryani, A. H., Moradipour, P., and Behbood, L. (2018). Biomacromolecular based fibers in nanomedicine: a combination of drug delivery and tissue engineering. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 18, 909–924. doi:10.2174/1389201019666180112144759

Bagade, R., Chaudhary, R. G., Potbhare, A., Mondal, A., Desimone, M., Dadure, K., et al. (2019). Microspheres/custard-apples copper (II) chelate polymer: characterization, docking, antioxidant and antibacterial assay. ChemistrySelect 4, 6233–6244. doi:10.1002/slct.201901115

Balagangadharan, K., Dhivya, S., and Selvamurugan, N. (2017). Chitosan based nanofibers in bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 104, 1372–1382. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.12.046

Berger, J., Reist, M., Mayer, J. M., Felt, O., and Gurny, R. (2004). Structure and interactions in chitosan hydrogels formed by complexation or aggregation for biomedical applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 57, 35–52. doi:10.1016/S0939-6411(03)00160-7

Chaudhary, R. G., Ali, P., Gandhare, N. V., Tanna, J. A., and Juneja, H. D. (2019). Thermal decomposition kinetics of some transition metal coordination polymers of fumaroyl bis (paramethoxyphenylcarbamide) using DTG/DTA techniques. Arab. J. Chem. 12, 1070–1082. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2016.03.008

Chouke, B., Potbhare, P., K., Bhusari, A., S., Subhash, G., Somkuwar, S., Shaik, P. M. D., et al. (2019). Green fabrication of zinc oxide nanospheres by aspidopterys cordata for effective antioxidant and antibacterial activity. Adv. Mater. Lett. 10, 355–360. doi:10.5185/amlett.2019.2235

Dinis, T. M., Elia, R., Vidal, G., Dermigny, Q., Denoeud, C., Kaplan, D. L., et al. (2015). 3D multi-channel bi-functionalized silk electrospun conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 41, 43–55. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.09.029

Duru Kamaci, U., and Peksel, A. (2020). Fabrication of PVA-chitosan-based nanofibers for phytase immobilization to enhance enzymatic activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 164, 3315–3322. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.226

Fisher, R. A., Gollan, B., and Helaine, S. (2017). Persistent bacterial infections and persister cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 15, 453–464. doi:10.1038/nrmicro.2017.42

Fu, R., Li, C., Yu, C., Xie, H., Shi, S., Li, Z., et al. (2016). A novel electrospun membrane based on moxifloxacin hydrochloride/poly(vinyl alcohol)/sodium alginate for antibacterial wound dressings in practical application. Drug Deliv. 23, 828–839. doi:10.3109/10717544.2014.918676

Gong, M., Huang, C., Huang, Y., Li, G., Chi, C., Ye, J., et al. (2019). Core-sheath micro/nano fiber membrane with antibacterial and osteogenic dual functions as biomimetic artificial periosteum for bone regeneration applications. Nanomed. Nanotechno. Biol. Med. 17, 124–136. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2019.01.002

Hameed, M., Rasul, A., Nazir, A., Yousaf, A. M., Hussain, T., Khan, I. U., et al. (2020). Moxifloxacin-loaded electrospun polymeric composite nanofibers-based wound dressing for enhanced antibacterial activity and healing efficacy. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomater., 1–9. doi:10.1080/00914037.2020.1785464

Han, W., Wu, Z., Li, Y., and Wang, Y. (2019). Graphene family nanomaterials (GFNs)—promising materials for antimicrobial coating and film: a review. Chem. Eng. J. 358, 1022–1037. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2018.10.106

Hang, A. T., Tae, B., and Park, J. S. (2010). Non-woven mats of poly(vinyl alcohol)/chitosan blends containing silver nanoparticles: fabrication and characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 82, 472–479. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2010.05.016

Huang, J., Zhou, X., Shen, Y., Li, H., Zhou, G., Zhang, W., et al. (2020). Asiaticoside loading into polylactic-co-glycolic acid electrospun nanofibers attenuates host inflammatory response and promotes M2 macrophage polarization. J. Biomed. Mater. Res.-Part. A. 108, 69–80. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.36793

Kakunuri, M., Wanasekara, N. D., Sharma, C. S., Khandelwal, M., and Eichhorn, S. J. (2017). Three-dimensional electrospun micropatterned cellulose acetate nanofiber surfaces with tunable wettability. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 134, 44709(1-7). doi:10.1002/app.44709

Kamoun, E. A., Kenawy, E. S., and Chen, X. (2017). A review on polymeric hydrogel membranes for wound dressing applications: PVA-based hydrogel dressings. J. Adv. Res. 8, 217–233. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2017.01.005

Karthikeyan, P., Banu, H. A. T., and Meenakshi, S. (2019). Synthesis and characterization of metal loaded chitosan-alginate biopolymeric hybrid beads for the efficient removal of phosphate and nitrate ions from aqueous solution. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 130, 407–418. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.02.059

Karuppuswamy, P., Reddy Venugopal, J., Navaneethan, B., Luwang Laiva, A., and Ramakrishna, S. (2015). Polycaprolactone nanofibers for the controlled release of tetracycline hydrochloride. Mater. Lett. 141, 180–186. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2014.11.044

Kim, S. (2018). Competitive biological activities of chitosan and its derivatives: antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory activities. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2018, 1–13. doi:10.1155/2018/1708172

Koosha, M., and Mirzadeh, H. (2015). Electrospinning, mechanical properties, and cell behavior study of chitosan/PVA nanofibers. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 103, 3081–3093. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.35443

Lee, D. J., Fontaine, A., Meng, X., and Park, D. (2016). Biomimetic nerve guidance conduit containing intraluminal microchannels with aligned nanofibers markedly facilitates in nerve regeneration. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2, 1403–1410. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.6b00344

Li, S., Zhang, R., Xie, J., Sameen, D. E., Ahmed, S., Dai, J., et al. (2020). Electrospun antibacterial poly(vinyl alcohol)/Ag nanoparticles membrane grafted with 3,3′,4,4′-benzophenone tetracarboxylic acid for efficient air filtration. Appl. Surf. Sci. 533, 147516. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.147516

Luo, C. J., Stoyanov, S. D., Stride, E., Pelan, E., and Edirisinghe, M. (2012). Electrospinning versus fibre production methods: from specifics to technological convergence. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 4708–4735. doi:10.1039/c2cs35083a

Ma, G., Liu, Y., Fang, D., Chen, J., Peng, C., Fei, X., et al. (2012). Hyaluronic acid/chitosan polyelectrolyte complexes nanofibers prepared by electrospinning. Mater. Lett. 74, 78–80. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2012.01.012

Mahmoudi, M., Sant, S., Wang, B., Laurent, S., and Sen, T. (2011). Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs): development, surface modification and applications in chemotherapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 63, 24–46. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2010.05.006

Menazea, A. A., and Ahmed, M. K. (2020). Wound healing activity of Chitosan/Polyvinyl Alcohol embedded by gold nanoparticles prepared by nanosecond laser ablation. J. Mol. Struct. 1217, 128401. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128401

Mishra, R. K., Mishra, P., Verma, K., Mondal, A., Chaudhary, R. G., Abolhasani, M. M., et al. (2019). Electrospinning production of nanofibrous membranes. Envi. Chem. Lett. 17, 767–800. doi:10.1007/s10311-018-00838-w

Qin, Z. Y., Jia, X. W., Liu, Q., Kong, B. H., and Wang, H. (2019). Fast dissolving oral films for drug delivery prepared from chitosan/pullulan electrospinning nanofibers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 137, 224–231. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.06.224

Schiffman, J. D., and Schauer, C. L. (2007). One-step electrospinning of cross-linked Chitosan fibers. Biomacromolecules 8, 2665–2667. doi:10.1021/bm7006983

Silva, D., de Sousa, H. C., Gil, M. H., Santos, L. F., Oom, M. S., Alvarez-Lorenzo, C., et al. (2021). Moxifloxacin-imprinted silicone-based hydrogels as contact lens materials for extended drug release. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 156, 105591. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2020.105591

Sonkusare, V. N., Chaudhary, R. G., Bhusari, G. S., Rai, A. R., and Juneja, H. D. (2018). Microwave-mediated synthesis, photocatalytic degradation and antibacterial activity of α-Bi2O3 microflowers/novel γ-Bi2O3 microspindles. Nano-Struc. and Nano-Objects 13, 121–131. doi:10.1016/j.nanoso.2018.01.002

Sun, B., Zhou, Z., Wu, T., Chen, W., Li, D., Zheng, H., et al. (2017). Development of nanofiber sponges-containing nerve guidance conduit for peripheral nerve regeneration in vivo. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 9, 26684–26696. doi:10.1021/acsami.7b06707

Sun, J., Perry, S. L., and Schiffman, J. D. (2019). Electrospinning nanofibers from chitosan/hyaluronic acid complex coacervates. Biomacromolecules 20, 4191–4198. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.9b01072

Tanna, J. A., Chaudhary, R. G., Gandhare, N. V., and Juneja, H. D. (2016). Alumina nanoparticles: a new and reusable catalyst for synthesis of dihydropyrimidinones derivatives. Adv. Mater. Lett. 7, 933–938. doi:10.5185/amlett.2016.6245

Wan, L., Wu, Y., Zhang, B., Yang, W., Ding, H., and Zhang, W. (2020). Effects of moxifloxacin and gatifloxacin stress on growth, photosynthesis, antioxidant responses, and microcystin release in Microcystis aeruginosa. J. Hazard. Mater. 9, 124518. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124518

Wang, S., Yan, F., Ren, P., Li, Y., Wu, Q., Fang, X., et al. (2020). Incorporation of metal-organic frameworks into electrospun chitosan/poly (vinyl alcohol) nanofibrous membrane with enhanced antibacterial activity for wound dressing application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 158, 9–17. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.04.116

Wu, Y., Wan, L., Zhang, W., Ding, H., and Yang, W. (2020). Resistance of cyanobacteria Microcystis aeruginosa to erythromycin with multiple exposure. Chemosphere 249, 126147. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126147

Xue, J., Pisignano, D., and Xia, Y. (2020). Maneuvering the migration and differentiation of stem cells with electrospun nanofibers. Adv. Sci. 7, 1–17. doi:10.1002/advs.202000735

Yuan, T. T., Jenkins, P. M., Digeorge Foushee, A. M., Jockheck-Clark, A. R., and Stahl, J. M. (2016). Electrospun chitosan/polyethylene oxide nanofibrous scaffolds with potential antibacterial wound dressing applications. J. Nanomater. 2016, 6231040. doi:10.1155/2016/6231040

Zhang, W., Zhao, L., Ma, J., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Ran, F., et al. (2017). Electrospinning of fucoidan/chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol) scaffolds for vascular tissue engineering. Fibers Polym. 18, 922–932. doi:10.1007/s12221-017-1197-3

Zhao, Y., Cao, X., and Jiang, L. (2007). Bio-mimic multichannel microtubes by a facile method. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 764–765. doi:10.1021/ja068165g |

Zheng, X., Jongedijk, E. M., Hu, Y., Kuhlin, J., Zheng, R., Niward, K., et al. (2020). Development and validation of a simple LC-MS/MS method for simultaneous determination of moxifloxacin, levofloxacin, prothionamide, pyrazinamide and ethambutol in human plasma. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 1158, 122397. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2020.122397

Keywords: nanofiber, antibacterial, electrospinning, moxifloxacin, poly(vinyl alcohol), chitosan

Citation: Liu Q, Ouyang W-C, Zhou X-H, Jin T and Wu Z-W (2021) Antibacterial Activity and Drug Loading of Moxifloxacin-Loaded Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)/Chitosan Electrospun Nanofibers. Front. Mater. 8:643428. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2021.643428

Received: 18 December 2020; Accepted: 25 January 2021;

Published: 24 February 2021.

Edited by:

Magdalena M. Stevanović, Institute of Technical Sciences (SASA), SerbiaReviewed by:

Sanjay Mavinkere Rangappa, King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok, ThailandCopyright © 2021 Liu, Ouyang, Zhou, Jin and Wu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zheng-wei Wu, d3V6d0B1c3RjLmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.