95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

MINI REVIEW article

Front. Mater. , 12 February 2020

Sec. Energy Materials

Volume 7 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2020.00004

This article is part of the Research Topic Chemistry, Synthesis, and Interaction of Advanced Electrolyte Materials for High-Energy-Density Batteries View all 8 articles

Compared with that of proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs), alkaline anion exchange membrane fuel cells (AEMFCs) with alkaline anion exchange membranes (AEMs) as electrolytes are attracting increased attention due to their potential use as non-precious catalysts. As one of the key components of AEMFCs, an ideal AEM must possess high hydroxide conductivity, good thermal stability, sufficient mechanical stability, and excellent long-term durability at elevated temperatures in an alkaline environment. Until now, a large number of AEMs with various chemical structures and properties have been prepared, and studied in detail, and it has been found that the microphase separation structure greatly affected the performance of AEMs. This minireview provides recent progress made of AEMs with hydrophilic/hydrophobic microphase separation structure. The hydroxide conductivity, alkaline stability, and mechanical properties of AEMs could be improved due to the formation of hydrophilic/hydrophobic microphase separation in the membranes. The relationship among the microphase separation, the chemical structure of the polymers, and the performance of membranes has been discussed in detail. This article attempts to give an overview of some key factors for the future design of novel AEMs with excellent performance such as high conductivity and improved chemical stability.

With the increasing exhaustion of fossil energy and the ever-growing demand for power, environment-friendly power generation technology with high efficiency is urgently needed (Wu et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2016). Fuel cells are electrochemical devices that directly convert the chemical energy of a fuel (such as hydrogen or methanol) into electrical energy (Noonan et al., 2012; Chu et al., 2015; Feng et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019). Compared to that of the fuel cells with liquid electrolytes, polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells, which use solid polymer electrolyte membranes, possess higher power densities, simplified operations, and easier maintenance and have attracted much attention during the last decades (Olsson et al., 2018; Pham et al., 2019). Based on the polymer electrolyte membrane, the polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells could be classified as proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs), and alkaline anion exchange membrane fuel cells (AEMFCs).

Compared with that of PEMFCs with Nafion® membranes (electrolyte), AEMFCs that operated under high pH conditions enable the use of non-precious metal catalysts (such as cobalt, nickel, or silver) instead of Pt-based catalysts (Pan et al., 2010a; Palaniselvam et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2017). Furthermore, AEMFCs with solid anion exchange membranes (AEMs) solved the electrolyte leakage problem (KOH solution) of the traditional alkaline fuel cells. As a key component of AEMFCs, an ideal AEM should possess high hydroxide conductivity, excellent mechanical property, good thermal stability, and robust alkaline stability to play the important role in separating fuels and transporting OH− from anode to cathode of AEMFCs (Lin et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2019). Typically, AEMs are composed of polymer backbone and cationic groups, and are connected by covalent bond (Han et al., 2017; Mayadevi et al., 2019). In an early research, it is thought that the backbone of polymers affects the mechanical strength of AEMs, and the cationic groups influence their hydroxide conductivity, and chemical stability (especial alkaline stability of membranes). However, the intrinsically low mobility of OH− and the degradation of cations in high pH condition severely limited the application of AEMs (Jheng et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2018).

In recent years, various AEMs based on aliphatic or aromatic polymers [such as poly(sulfone)s, poly(arylene ether)s, poly(phenylene)s, poly(styrene)s, polypropylene, poly(phenylene oxide)s, poly(olefin)s, poly(arylene piperidinium), and poly(biphenyl alkylene)s] with different cationic groups (such as quaternary ammonium, guanidinium, imidazolium, pyridinium, tertiary sulfonium, spirocyclic quaternary ammonium, phosphonium, phosphatranium, phosphazenium, metal-cation, benzimidazolium, and pyrrolidinium) have been synthesized to prepare AEMs with high conductivity and excellent alkaline stability (Choi et al., 2005; Gu et al., 2009; Kong et al., 2009; Pan et al., 2010b; Zhang et al., 2010, 2012; Kim et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2011, 2013a; Döbbelin et al., 2012; Zha et al., 2012; Arges et al., 2014; Pham and Jannasch, 2015; Xue et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018; Peng et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Although the performance of AEMs was greatly enhanced during the past few years, the foundational properties of AEMs are not comparable to those of PEMs (such as Nafion) due to the intrinsic low mobility of OH− and the well-known base-induced decomposition of organic cations as well as polymer backbones (Tanaka et al., 2011; Noonan et al., 2012; Qiu et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2017; Hao et al., 2018). The state-of-the-art Nafion membranes possess high conductivity due to their well-defined hydrophilic/hydrophobic phase separation structure caused by its hydrophobic backbone and hydrophilic long side sulfonic groups (Li and Guiver, 2014). Inspired from this, various AEMs with hydrophilic/hydrophobic microphase separation structure were developed and showed improved conductivity and alkaline stability. In this minireview, we briefly introduce the methods for enhancing the performance of AEMs and provide recent progresses of AEMs with hydrophilic/hydrophobic microphase separation structure, and the relationship between microphase separation structure and the performance of membranes has been discussed in detail.

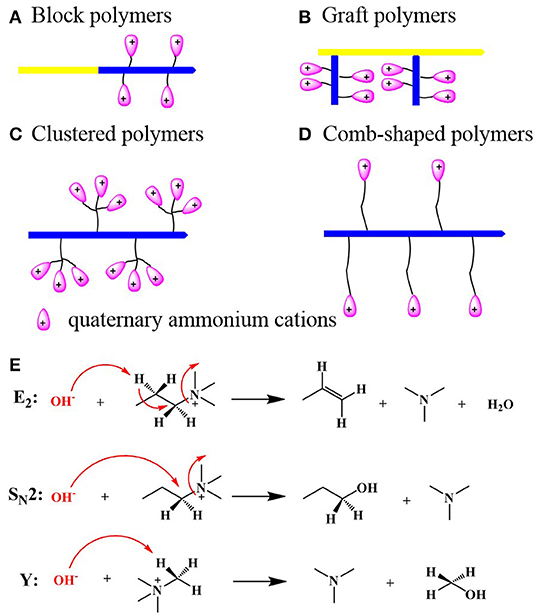

In fact, developing an appropriate hydrophilic/hydrophobic microphase separation structure is an effective way to solve the conductivity and stability limitation of AEMs. During the past few years, a series of AEMs with microphase separation structure have been reported, and most of them possess high conductivity, relatively low swelling ratio, and good alkaline stability. However, not each of the AEMs could develop their microphase separation structure; it is necessary to design the chemical structure of polymer backbone, and its side cationic groups. In recent years, several approaches, including synthesis of block (Tanaka et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2019a), graft (Varcoe et al., 2007), clustered (Zhu et al., 2016), and comb-shaped (Li et al., 2013) polymers with tethered organic cations, have been pursued to obtain AEMs with microphase separation structure (Figures 1A–D). Among various polymers, comb-shaped polymers are the most popular ones that are used to prepare AEMs with microphase separation due to their good designability, and can be obtained both from pre- and postmodification method. Although the AEMs with microphase separation were obtained by different methods, most of them showed high conductivity and robust alkaline stability (Table 1), and they showed obviously higher conductivity than those membranes with similar ion exchange capacity (IEC), and chemical structure but with no microphase separation (Tanaka et al., 2011).

Figure 1. Illustrations of several polymer architectures of AEMs with well-defined microphase separation morphology: block (A), graft (B), clustered (C), and comb-shaped polymers (D) and the possible degradation mechanisms of QA cations in alkaline solutions: Hofmann elimination (E2), nucleophilic substitution (SN2), and ylide formation (Y) (E).

To investigate the micromorphology of AEMs, transmission electron microscope (TEM), atomic force microscope (AFM), and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) are usually used. Among these testing instruments, TEM is an effective method that can directly exhibit the microphase separation of membranes. However, the complex sample preparation process is a big challenge when collecting the TEM images (You et al., 2019). The microphase separation can be proved by the minimal correlations between the AFM phase images and height images (Lin et al., 2017). Unfortunately, the surface of membrane samples for AFM testing should be smooth, and the water uptake of membranes could greatly affect the AFM phase images. SAXS pattern is also a simple and efficient method to investigate the micromorphology of AEMs. Compared with that of AFM and TEM, there is much lower demand on the sample preparation for the SAXS testing. The appearance and the location of an ionomer peak are important parameters of SAXS patterns. The characteristic separation size of ionic clusters (microphase separation) can be calculated from the equation d = 2π/q, and the larger the value of d, the more obvious the microphase separation can be found in the membrane (Niu et al., 2019).

In the pursuit of high-performance AEMs, anion-conductive block copolymers display promising properties for electrochemical devices application, where the unique block architecture induces the phase separation leading to the dramatic improvement of ionic conductivities. As a commercial block copolymer, polystyrene-b-polybutadiene-b-polystyrene (SBS) has been wildly investigated, and its block structure renders it a promising material for the preparation of AEMs with microphase separation structure. Recently, a series of side-chain-type AEMs based on quaternized SBS have been reported by Liu et al. (2018); these AEMs showed exciting alkaline stability and high conductivity. It is no surprise that hydrophilic/hydrophobic microphase separation was observed for the quaternized SBS-based membrane by TEM due to the original triblock structure of SBS. Zhu et al. (2019) prepared a series of side-chain poly(olefin)-based AEMs by Ziegler-Natta polymerization of 4-(4-methylphenyl)-1-butene with 11-bromo-1-undecene. The ionic peak was observed at 0.97 nm−1 for the M20C9NC6NC5N membrane in SAXS profiles, indicating the interdomain spacing of ~6.5 nm. These results proved the obvious microphase separation structure formed in the side-chain poly(olefin)-based membrane. Besides these, AEMs with comb-shaped side chains possess the structure of microphase separation. Ponce-Gonzalez et al. (2016) used SAXS to compare the microstructure of poly (olefin)-based AEMs with different cationic groups prepared by radiation grafting. The location of the ionic peak for the AEMs with pyridinium and pyrrolidinium was 0.22 nm−1, while that for the membrane with benzyltrimethyl quaternary ammonium was 0.16 nm−1 under dry conditions. Under 100% RH, the location of the ionic peak for the AEMs with pyridinium and pyrrolidinium changed to 0.11 nm−1, and there was no obvious change of the location of the ionic peak with these three cationic groups after the treatment of soaking in boiling water. Recently, a novel strategy to improve the performance of AEMs is adopted to build a cross-linked structure by tethering the rigid poly(2, 6-dimethyl-1, 4-phenylene oxide) (PPO) backbone and the flexible poly(4-vinylphenol) (PVP) backbone using an oscillational chain. The incompatibility between the PPO and PVP backbones makes them self-aggregated resulting in the occurrence of distinct microphase separation. The microphase separation of the as-prepared AEMs has been revealed by TEM and AFM (Yang et al., 2019).

It is a huge challenge for developing AEMs that possess high conductivity, low swelling ratio, robust alkaline stability, and excellent mechanical properties at the same time. On the other hand, the formation of hydrophilic/hydrophobic microphase separation structure in the AEMs is probably a promise approach to solve this contradiction.

Hydroxide conductivity is one of the most important parameters of AEMs, which plays a key role in the performance of AEMFCs (Shin et al., 2017). However, the conductivity of the membrane was deeply affected by lots of factors, such as IEC, water uptake, microphase separation, and cationic groups. Compare with that of PEMs, the AEMs show lower conductivity due to the intrinsic lower mobility of OH− than that of H+. Raising their IEC is an efficient and simple way to improve the conductivity of AEMs. Unfortunately, membrane swelling is generally accompanied with high IEC and thus results in poor mechanical strength of AEMs (Pan et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2013; Hou et al., 2016; Shukala and Shahi, 2018; Gao et al., 2019a). The swelling ratio of AEMs could be greatly reduced by introducing cross-linked structures, while the tight structure of membranes hinder the mobility of OH−, which reduces their conductivity (Liang et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2019b).

Recently, it has been found that the formation of microphase separation structure in membranes could improve the conductivity of AEMs (Mohanty et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2017; Han et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019). The microphase separation and the aggregation of ionic channels were driven by the hydrophilic/hydrophobic segment of the polymer, which constructs the ionic highway for OH− conduction, shortens the pathway, and enhances the OH− conducting efficiency in membranes (Pan et al., 2014; Han et al., 2019). In addition, hydrophobic segments control dimensional swelling in water and enhance the mechanical properties that make it possible for AEMs to possess high conductivity and good mechanical strength with relatively low IEC and dimensional swelling. Recently, Gao et al. (2019b) prepared AEMs with rigid-side-chain symmetric piperazinium structures possessing high conductivity, which can be up to 61 mS cm−1 at 20°C due to the formation of microphase separation. By carefully designing and controlling the size of the hydrophobic segment, the swelling ratio of the AEM (Q-PAPip) is lower than 30% at 30°C. Jin et al. (2019) reported poly(arylene piperidine)-based AEMs with microphase separation that resulted by introducing long side heterocyclic ammonium cations onto the backbone, which showed a much higher conductivity (25 mS cm−1 at 20°C) than that of AEMs with similar IEC but without long side cations (9.6 mS cm−1 at 21°C) (Thomas et al., 2012).

The alkaline stability of AEMs also limited the application of AEMFCs. Generally, the chemical structure of cationic groups determined the alkaline stability of AEMs. The most commonly used cationic groups for AEMs are quaternary ammonium (QA) cations. However, as is shown in Figure 1E, QA cations are unstable under high pH conditions especially at elevated temperatures, due to the degradation via Hofmann elimination (E2), nucleophilic substitution (SN2), and (or) ylide formation (Y) (Lin et al., 2010). Though a series of AEMs based on various organic cations that are different from QA cations, such as guanidinium, imidazolium, pyridinium, tertiary sulfonium, spirocyclic quaternary ammonium, phosphonium, phosphatranium, phosphazenium, metal-cation, benzimidazolium, and pyrrolidinium, were developed during the last few years, the alkaline stability of cations could be enhanced by introducing proper groups due to their steric hindrance effect and electron donor effect. However, all organic groups, more or less, will be degraded under alkaline condition at high temperature because of the nucleophilic attack form OH− to organic cations (Lin et al., 2013b; Marino and Kreuer, 2015), and the alkaline stability of AEMs should be further enhanced. More recently, some papers reported that the chemical structure of the backbone also influences the alkaline stability of AEMs, and the polymer backbones with ether bonds degrade quickly under alkaline conditions (Mohanty et al., 2016; Pham et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2018).

Dang reported a series of AEMs with comb-shaped side chain in which the cation groups are separated from the polymer backbone by the long flexible alkyl spacers, and the comb-shaped AEMs showed much higher alkaline stability than the traditional AEMs with benzyltrimethylammonium groups due to the low electro-withdrawing and steric effects on QA groups. Moreover, the introduction of the flexible spacer between QA cations and backbones enhanced the mobility of QA cations, which is favorable for the formation of distinct ionic clusters in membranes and enhanced the water transport in the membranes, thereby creating an environment that is less favorable for ionomer degradation (Hibbs, 2013; Dang and Jannasch, 2015; Dekel et al., 2019). Improved alkaline stability was observed for other AEMs with microphase separation structure based on various polymer backbones and cationic groups (Oh et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2019c; Han et al., 2019). The AEMs with a well-defined microphase separation possess a suppressed swelling ratio and water uptake, and the OH− was located in the hydrophilic phase of membranes. On the other hand, the hydrophobic phase of AEMs in the ordered microphase separation could weaken the nucleophilic attack from OH− in the hydrophilic phase to the backbone and thereby the alkaline stability of the backbone could be maintained (Han et al., 2019). To obtain AEMs possessing high conductivity, low-dimensional swelling, and excellent alkaline stability at the same time, fabrication of hydrophobic/hydrophilic microphase separation structure in AEMs is a promising method.

Among various types of fuel cells, AEMFCs have attracted enormous attention as clean and high-efficient conversion devices. As the key component of AEMFCs, AEMs act both as a barrier to separate the fuel and an electrolyte to transport OH− from the anode and the cathode. In order to meet AEMFCs' practical application and commercialization, AEMs should possess high conductivity, and excellent alkaline stability under alkaline conditions. The micromorphology and chemical structure of backbone and cations have a great impact on the properties of AEMs. Although various AEMs with different chemical structures and micromorphology have been prepared to improve their conductivity, and alkaline stability, AEMs with excellent performance are highly desirable. In this minireview, we provided an up-to-date summary of the AEMs with microphase separation structure and summarized the chemical structure of the polymers that are favorable to forming the hydrophilic/hydrophobic microphase separation in AEMs. Various polymer architectures, including block, graft, clustered, and comb-shaped polymers with tethered organic cations, have been synthesized for the preparation of AEMs with microphase separation structure. The formation of hydrophilic/hydrophobic microphase separation structure in the AEMs has three benefits. Firstly, the OH− conductivity could be greatly improved due to the formation of ion transport channels in the membranes. Secondly, the hydrophobic segments restrict the membranes' dimensional swelling in water and make it possible that AEMs possess good mechanical strength. Thirdly, the alkaline stability of AEMs could be enhanced because the hydrophobic phase weakens the nucleophilic attack from OH− to the backbone. After recent development, the conductivity and alkaline stability of AEMs have been improved greatly. In fact, the fabrication of AEMFCs is a complex procedure; besides the properties of AEMs, there are so many parameters such as gas pressure, catalysts, as well as work temperature that affect the performance of AEMFCs. Therefore, in future work, we should focus more of our attention on the properties of AEMs under the practical working situation of AEMFCs and optimize the preparation process of AEMFCs. This minireview may provide new ideas and approaches for the design and the fabrication of novel AEMs with high performance, crucial for the development of viable AEMFC technology. We believe that, although the commercial application of AEMFCs is multidisciplinary and still faces huge challenges, with the exertion and cooperation of all researchers, AEMFCs will be applied more widely from now on.

FX wrote the submitted mini review. YS revised and communicated the manuscript. BL supervised and wrote the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (51973022), the Natural Science Research of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (18KJA430004 and 17KJA430002) and a Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Arges, C. G., Wang, L. H., and Ramani, V. (2014). Simple and facile synthesis of water-soluble poly(phosphazenium) polymer electrolytes. RSC Adv. 4, 61869–61876. doi: 10.1039/C4RA13101K

Chen, N., Long, C., Li, Y., Lu, C., and Zhu, H. (2018). Ultrastable and high ion-conducting polyelectrolyte based on six-membered N-spirocyclic ammonium for hydroxide exchange membrane fuel cell applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 15720–15732. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b02884

Choi, Y. J., Park, J. M., Yeon, K. H., and Moon, S. H. (2005). Electrochemical characterization of poly(vinyl alcohol)/formyl methyl pyridinium (PVA-FP) anion-exchange membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 250, 295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2004.10.034

Chu, F., Lin, B., Feng, T., Wang, C., Zhang, S., Yuan, N., et al. (2015). Zwitterion coated graphene-oxide-doped composite membranes for proton exchange membrane applications. J. Membr. Sci. 496, 31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2015.09.001

Dang, H. S., and Jannasch, P. (2015). Exploring different cationic alkyl side chain designs for enhanced alkaline stability and hydroxide ion conductivity of anion-exchange membranes. Macromolecules 48, 5742–5751. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b01302

Dekel, D. R., Rasin, I. R., and Brandon, S. (2019). Predicting performance stability of anion exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 420, 118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.02.069

Döbbelin, M., Azcune, I., Bedu, M. L., Luzuriaga, A. R. D., Genua, A., and Jovanovski, V. (2012). Synthesis of pyrrolidinium-based poly(ionic liquid) electrolytes with poly(ethylene glycol) side chains. Chem. Mater. 24, 1583–1590. doi: 10.1021/cm203790z

Feng, T., Lin, B., Zhang, S., Yuan, N., Chu, F., Hickner, M. A., et al. (2016). Imidazolium-based organic-inorganic hybrid anion exchange membranes for fuel cell applications. J. Membr. Sci. 508, 7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.02.019

Gao, L., Wang, Y., Cui, C. Y., Zheng, W. J., Yan, X. M., and Zhang, P. (2019b). Anion exchange membranes with “rigid-side-chain” symmetric piperazinium structures for fuel cell exceeding 1.2 W cm−2 at 60°C. J. Power Sources 438:227021. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.227021

Gao, X. L., Yang, Q., Wu, H. Y., Sun, Q. H., Zhu, Z. Y., Zhang, Q. G., et al. (2019c). Orderly branched anion exchange membranes bearing long flexible multication side chain for alkaline fuel cells. J. Membr. Sci. 589, 117247–117255. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2019.117247

Gao, X. Q., Yu, H. M., Qin, B. W., Jia, J., Hao, J. K., and Xie, F., et al. (2019a). Enhanced water transport in AEMs based on poly (styreneethylene-butylene-styrene) triblock copolymer for high fuel cells performance. Polym. Chem. 10, 1894–1903. doi: 10.1039/C8PY01618F

Gu, S., Cai, R., Luo, T., Chen, Z., Sun, M., and Liu, Y., et al. (2009). A soluble and highly conductive ionomer for high-performance hydroxide exchange membrane fuel cells. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 6499–6502. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806299

Han, J. J., Pan, J., Chen, C., Wei, L., Wang, Y., and Pan, Q. Y., et al. (2019). Effect of micromorphology on alkaline polymer electrolyte stability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 469–477. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b09481

Han, J. J., Zhu, L., Pan, J., Zimudzi, T. J., Wang, Y., and Peng, Y. Q., et al. (2017). Elastic long-chain multication cross-linked anion exchange membranes. Macromolecules 50, 3323–3332. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01140

Hao, J. K., Jiang, Y. Y., Gao, X. Q., Lu, W. T., Xiao, Y., and Shao, Z. G., et al. (2018). Functionalization of polybenzimidazole crosslinked poly(vinylbenzyl chloride) with two cyclic quaternary ammonium cations for anion exchange membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 548, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.10.062

Hibbs, M. R. (2013). Alkaline stability of poly (phenylene)-based anion exchange membranes with various cations. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 51, 1736–1742. doi: 10.1002/polb.23149

Hou, J. Q., Wang, X. Y., Liu, Y. Z., Ge, Q. Q., Yang, Z. J., and Wu, L., et al. (2016). Wittig reaction constructed an alkaline stable anion exchange membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 518, 282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2016.07.020

Jheng, L. C., Hsu, S, L., Lin, B. Y., and Hsu, Y. L. (2014). Quaternized polybenzimidazoles with imidazolium cation moieties for anion exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Membr. Sci. 460, 160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2014.02.043

Jin, C. H., Zhang, S., Cong, Y. Y., and Zhu, X. L. (2019). Highly durable and conductive poly(arylene piperidine) with a long heterocyclic ammonium side-chain for hydroxide exchange membranes. Int. J. Hydr. Energy 44, 24954–24964. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.07.184

Kim, D. S., Labouriau, A., Guiver, M. D., and Kim, Y. S. (2011). Guanidinium-functionalized anion exchange polymer electrolytes via activated fluorophenyl-amine reaction. Chem. Mater. 23, 3795–3797. doi: 10.1021/cm2016164

Kim, Y., Moh, L. C. H., and Swager, T. M. (2017). Anion exchange membranes: enhancement by addition of unfunctionalized triptycene poly(ether sulfone)s. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 42409–42414. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b13058

Kong, X. Q., Wadhwa, K., Verkade, J. G., and Schmidt-Rohr, K. (2009). Determination of the structure of a novel anion exchange fuel cell membrane by solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Macromolecules 42, 1659–1664. doi: 10.1021/ma802613k

Li, N., Leng, Y., Hickner, M. A., and Wang, C.-Y. (2013). Highly stable, anion conductive, combshaped copolymers for alkaline fuel cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 10124–10133. doi: 10.1021/ja403671u

Li, N. W., and Guiver, M. D. (2014). Ion transport by nanochannels in ion-containing aromatic copolymers. Macromolecules 47, 2175–2198. doi: 10.1021/ma402254h

Liang, X., Shehzad, M. A., Zhu, Y., Wang, L. Q., Ge, X. L., and Zhang, J. J. (2019). Ionomer cross-linking immobilization of catalyst nanoparticles for high performance alkaline membrane fuel cell. Chem. Mater. 31, 7812–7820. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b00999

Lin, B. C., Dong, H. L., Li, Y. Y., Si, Z. H., Gu, F. L., and Yan, F. (2013b). Alkaline stable C2-substituted imidazolium-based anion exchange membranes. Chem. Mater. 25,1858–1867. doi: 10.1021/cm400468u

Lin, B. C., Qiao, G., Chu, F. Q., Wang, J., Feng, T. Y., and Yuan, N. Y., et al. (2017). Preparation and characterization of imidazoliumbased membranes for anion exchange membrane fuel cell applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 42, 6988–6992. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.11.169

Lin, B. C., Qiu, L. H., Lu, J. M., and Yan, F. (2010). Cross-linked alkaline ionic liquid-based polymer electrolytes for alkaline fuel cell applications. Chem. Mater. 22, 6718–6725. doi: 10.1021/cm102957g

Lin, B. C., Qiu, L. H., Qiu, B., Peng, Y., and Yan, F. (2011). A soluble and conductive polyfluorene ionomer with pendant imidazolium groups for alkaline fuel cell applications. Macromolecules 44, 9642–9649. doi: 10.1021/ma202159d

Lin, B. C., Xu, F., Chu, F. Q., Ren, Y. R., Ding, J. N., and Yan, F. (2019b). Bis-imidazolium based poly(phenylene oxide) anion exchange membranes for fuel cells: the effect of cross-linking. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 13275–13283. doi: 10.1039/C9TA00028C

Lin, B. C., Xu, F., Su, Y., Zhu, Z. J., Ren, Y. R., Ding, J. N., et al. (2019a). Facile preparation of anion exchange membrane based on polystyreneb-polybutadiene-b-polystyrene for the application of alkaline fuel cells. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 58, 22299–22305. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.9b05314

Lin, B. C., Yuan, W. S., Xu, F., Chen, Q., Zhu, H. H., and Li, X. X., et al. (2018). Protic ionic liquid/functionalized graphene oxide hybrid membranes for high temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cell applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 455, 295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.05.205

Lin, X. C., Liang, X. H., Poynton, S. D., Varcoe, J. R., Ong, A. L., and Ran, J., et al. (2013a). Novel alkaline anion exchange membranes containing pendant benzimidazolium groups for alkaline fuel cells. J. Membr. Sci. 443, 193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2013.04.059

Liu, L., Chu, X. M., and Li, N. W. (2019). Recent development in polyolefin-based anion exchange membrane for fuel cell application. Chin. Sci. Bull. 64, 123–133. doi: 10.1360/N972018-00880

Liu, L., Li, D. F., Xing, Y., and Li, N. W. (2018). Mid-block quaternized polystyrene-b-polybutadiene-b-polystyrene triblock copolymers as anion exchange membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 564, 428–435. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2018.07.055

Lu, W. T., Shao, Z. G., Zhang, G., Li, J., Zhao, Y., and Yi, B. L. (2013). Preparation of anion exchange membranes by an efficient chloromethylation method and homogeneous quaternization/crosslinking strategy. Solid State Ion. 245–246, 8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ssi.2013.05.005

Marino, M. G., and Kreuer, K. D. (2015). Alkaline stability of quaternary ammonium cations for alkaline fuel cell membranes and ionic liquids. Chem. Sus. Chem. 8, 513–523. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201403022

Mayadevi, T. S., Sung, S., Chae, J. E., Kim, H. J., and Kim, T. H. (2019). Quaternary ammonium-functionalized poly(ether sulfone ketone) anion exchange membranes: the effect of block ratios. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 44, 18403–18414. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.05.061

Mohanty, A. D., Tignor, S. E., Krause, J. A., Choe, Y. K., and Bae, C. (2016). Systematic alkaline stability study of polymer backbones for anion exchange membrane applications. Macromolecules 49, 3361–3372. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b02550

Niu, M. Y., Zhang, C. M., He, G. H., Zhang, F. X., and Wu, X. M. (2019). Pendent piperidinium-functionalized blend anion exchange membrane for fuel cell application. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 44, 15482–15493. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.04.172

Noonan, K. J. T., Hugar, K. M., Kostalik, H. A., Lobkovsky, E. B., Abruna, H. D., and Coates, G. W. (2012). Phosphonium-functionalized polyethylene: a new class of base stable alkaline anion exchange membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 18161–18164. doi: 10.1021/ja307466s

Oh, B. H., Kim, A. R., and Yoo, D. J. (2018). Profile of extended chemical stability and mechanical integrity and high hydroxide ion conductivity of poly(ether imide) based membranes for anion exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 12, 177–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2018.12.177

Olsson, J. S., Pham, T. H., and Jannasch, P. (2018). Poly(arylene piperidinium) hydroxide ion exchange membranes: synthesis, alkaline stability, and conductivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28:1702758. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201702758

Palaniselvam, T., Kashyap, V., Bhange, S. N., Baek, J. B., and Kurungot, S. (2016). Nanoporous graphene enriched Fe/Co-N active sites as a promising oxygen reduction electrocatalyst for anion exchange membrane fuel cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26:2150. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201504765

Pan, J., Chen, C., Li, Y., Wang, L., Tan, L. S., Li, G. W., et al. (2014). Constructing ionic highway in alkaline polymer electrolytes. Energy. Environ. Sci. 7, 354–360. doi: 10.1039/C3EE43275K

Pan, J., Chen, C., Zhuang, L., and Lu, J. T. (2012). Designing advanced alkaline polymer electrolytes for fuel cell applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 473–481. doi: 10.1021/ar200201x

Pan, J., Li, Y., Zhuang, L., and Lu, J. T. (2010b). Self-crosslinked alkaline polymer electrolyte exceptionally stable at 90°C. Chem. Commun. 46, 8597–8599. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03618h

Pan, J., Lu, S. F., Li, Y., Huang, A. B., Zhuang, L., and Lu, J. T. (2010a). High-performance alkaline polymer electrolyte for fuel cell applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 20, 312–319. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200901314

Peng, H. Q., Li, Q. H., Hu, M. X., Xiao, L., Lu, J. T., and Zhuang, L. (2018). Alkaline polymer electrolyte fuel cells stably working at 80°C. J. Power Sources 390, 165–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2018.04.047

Pham, T. H., and Jannasch, P. (2015). Aromatic polymers incorporating bis-n-spirocyclic quaternary ammonium moieties for anion-exchange membranes. ACS Macro Lett. 4, 1370–1375. doi: 10.1021/acsmacrolett.5b00690

Pham, T. H., Olsson, J. S., and Jannasch, P. (2017). N-spirocyclic quaternary ammonium ionenes for anion-exchange membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 2888–2891. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12944

Pham, T. H., Olsson, J. S., and Jannasch, P. (2019). Effects of alicyclic anion and backbone structure on the performance of poly(terphenyl)-based hydroxide exchange membranes. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 15895–15906. doi: 10.1039/C9TA05531B

Ponce-Gonzalez, J., Whelligan, D. K., Wang, L. Q., Bance-Soualhi, R., Wang, Y., and Peng, Y. Q. (2016). High performance aliphatic-heterocyclic benzyl-quaternary ammonium radiation-grafter anion-exchange membranes. Energy Environ. Sci. 9, 3724–3735. doi: 10.1039/C6EE01958G

Qiu, B., Lin, B. C., Si, Z. H., Qiu, L. H., Chu, F. Q., and Zhao, J., et al. (2012). Bis-imidazolium-based anion-exchange membranes for alkaline fuel cells. J. Power Sources 217, 329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.06.041

Ren, R., Zhang, S. M., Miller, H. A., Vizza, F., Varcoe, J. R., and He, Q. G. (2019). Facile preparation of an ether-free anion exchange membrane with pendant cyclic quaternary ammonium groups. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2, 4576–4581. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.9b00674

Shin, D. W., Guiver, M. D., and Lee, Y. M. (2017). Hydrocarbon-based polymer electrolyte membranes: importance of morphology on ion transport and membrane stability. Chem. Rev. 117, 4759–4805. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00586

Shukala, G., and Shahi, V. K. (2018). Poly (arylene ether ketone) copolymer grafted with amine groups containing long alkyl chain by chloroacetylation for improved alkaline stability and conductivity of anion exchange membrane. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 1, 1175–1182. doi: 10.1021/acsaem.7b00282

Sun, Z., Lin, B. C., and Yan, F. (2017). Anion exchange membranes for alkaline fuel cell applications: the effects of cations. Chem. Sus. Chem. 11, 58–70. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201701600

Sun, Z., Pan, J., Guo, J. N., and Yan, F. (2018). The alkaline stability of anion exchange membrane for fuel cell applications: the effects of alkaline media. Adv. Sci. 5:1800065. doi: 10.1002/advs.201800065

Tanaka, M., Fukasawa, K., Nishino, E., Yamaguchi, S., Yamada, K., and Tanaka, H., et al. (2011). Anion conductive block poly(arylene ether)s: synthesis, properties, and application in alkaline fuel cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 10646–10654. doi: 10.1021/ja204166e

Thomas, O. D., Soo, K. J. W. Y., Peckham, T. J., Kulkarni, M. P., and Holdcroft, S. (2012). A stable hydroxide-conducting polymer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 10753–10756. doi: 10.1021/ja303067t

Varcoe, J. R., Slade, R. C. T., Yee, E. L. H., Poynton, S. D., Driscoll, D. J., and Apperley, D. C. (2007). Poly(ethylene-co-tetrafluoroethylene)-derived radiation-grafted anion-exchange membrane with properties specifically tailored for application in metal-cation-free alkaline polymer electrolyte fuel cells. Chem. Mater. 19, 2686–2693. doi: 10.1021/cm062407u

Wang, J. H., Zhao, Y., Setzler, B. P., Rojas-Carbonell, S., Yehuda, C. B., Amel, A., et al. (2019). Poly (aryl piperidinium) membranes and ionomers for hydroxide exchange membrane fuel cells. Nat. Energy 4, 392–398. doi: 10.1038/s41560-019-0372-8

Wang, L. Q., Brink, J. J., and Varceo, J. R. (2017). The first anion-exchange membrane fuel cell to exceed 1 W cm−2 at 70°C with a non-Pt-group (O2) cathode. Chem. Commun. 53, 11771–11773. doi: 10.1039/c7cc06392j

Wu, W., Li, Y., Chen, P., Liu, J., Wang, J., and Zhang, H. (2016). Constructing ionic liquid-filled proton transfer channels within nanocomposite membrane by using functionalized graphene oxide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interface 8, 588–599. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b09642

Xu, F., Yuan, W. S., Zhu, Y. Y., Chu, X. F., Lin, B. C., and Chu, F. Q., et al. (2019). Preparation and properties of anion exchange membranes based on spirocyclic quaternary ammonium salts. Chin. Sci. Bull. 64, 165–171. doi: 10.1360/N972018-00665

Xue, J. D., Liu, L., Liao, J. Y., Shen, J. H., and Li, N. W. (2017). UV-crosslinking of polystyrene anion exchange membranes by azidated macromolecular crosslinker for alkaline fuel cells. J. Membr. Sci. 535, 322–330. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.04.049

Yang, C., Liu, L., Han, X. J., Huang, Z. G., Dong, J. P., and Li, N. W. (2017). Highly anion conductive, alkyl-chain-grafted copolymers as anion exchange membranes for operable alkaline H2/O2fuel cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 5, 10301–10310. doi: 10.1039/C7TA00481H

Yang, Q., Gang, X. L., Wu, H. Y., Cai, Y. Y., Zhang, Q. G., and Zhu, A. M., et al. (2019). Anion conductive membrane performance facilitation via tethering flexible with rigid backbones using oscillational chain. J. Power Sources 436:226856. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.226856

You, W., Padgett, E., Macmillan, S. N., Muller, D. A., and Coates, G. W. (2019). Highly conductive and chemically stable alkaline anion exchange membranes via ROMP of trans-cyclooctene derivatives. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 9729–9734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1900988116

Zha, Y. P., Disabb-Miller, M. L., Johnson, Z. D., Hickner, M. A., and Tew, G. N. (2012). Metal-cation-based anion exchange membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 4493–4496. doi: 10.1021/ja211365r

Zhang, B. Z., Gu, S., Wang, J. H., Liu, Y., Herring, Y. M., and Yan, Y. S. (2012). Tertiary sulfonium as a cationic functional group for hydroxide exchange membranes. RSC Adv. 2, 12683–12685. doi: 10.1039/c2ra21402d

Zhang, H., Shi, B., Ding, R., Chen, H., Wang, J., and Liu, J. (2016). Composite anion exchange membrane from quaternized polymer spheres with tunable and enhanced hydroxide conduction property. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 55, 9064–9076. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.6b01741

Zhang, Q., Li, S. H., and Zhang, S. B. (2010). A novel guanidinium grafted poly(aryl ether sulfone) for high-performance hydroxide exchange membranes. Chem. Commun. 46, 7495–7497. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01834a

Zhu, L., Pan, J., Wang, Y., Han, J., Zhuang, L., and Hickner, M. A. (2016). Multication side chain anion exchange membranes. Macromolecules 49, 815–824. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b02671

Zhu, L., Yu, X. D., Peng, X., Zimudzi, T. J., Saikia, N., and Kwasny, M. T., et al. (2019). Poly (olefin)-based anion exchange membranes prepared using Ziegler-Natta polymerization. Macromolecules 52, 4030–4041. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b02756

Keywords: anion exchange membrane, microphase separation, hydroxide conductivity, alkaline stability, fuel cell

Citation: Xu F, Su Y and Lin B (2020) Progress of Alkaline Anion Exchange Membranes for Fuel Cells: The Effects of Micro-Phase Separation. Front. Mater. 7:4. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2020.00004

Received: 25 November 2019; Accepted: 07 January 2020;

Published: 12 February 2020.

Edited by:

Shuhui Sun, Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique (INRS), CanadaReviewed by:

Zhao-Qing Liu, Guangzhou University, ChinaCopyright © 2020 Xu, Su and Lin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bencai Lin, bGluYmVuY2FpQGNjenUuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.