- 1Research Centre for Indian Ocean Ecosystem, Tianjin University of Science and Technology, Tianjin, China

- 2Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai), Zhuhai, China

- 3Institute of Marine Science and Technology, Shandong University, Qingdao, China

- 4College of Marine Science and Technology, China University of Geosciences, Wuhan, China

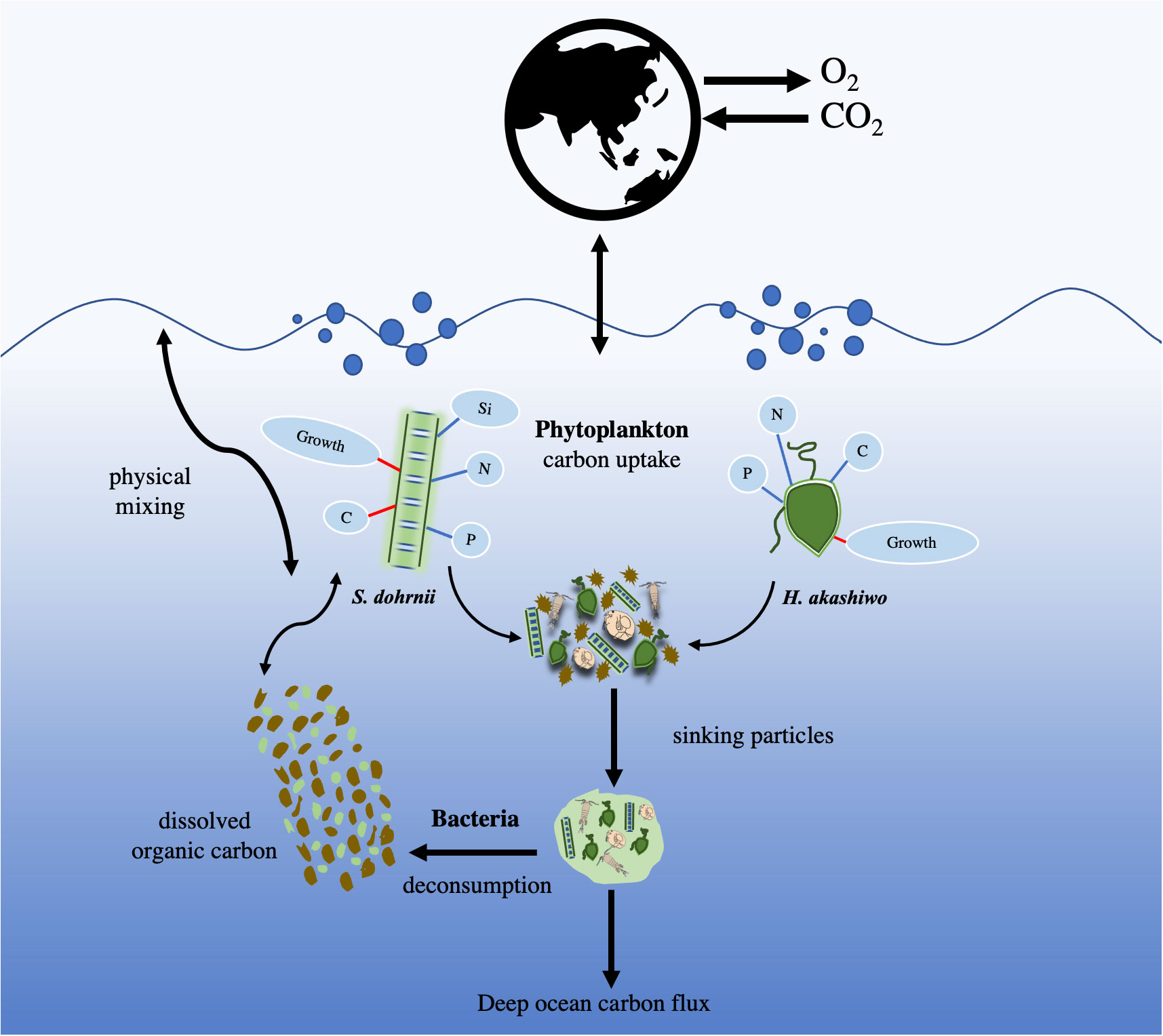

Carbon dioxide (CO2) serves as the primary substrate for the photosynthesis of phytoplankton, forming the foundation of marine food webs and mediating the biogeochemical cycling of C and N. We studied the effects of CO2 variation on the Michaelis-Menten equations and elemental composition of Skeletonema dohrnii and Heterosigma akashiwo. CO2 functional response curves were conducted from 100 to 2000 ppm. The growth of both phytoplankton was significantly affected by CO2, but in different trends. The growth rate of S. dohrnii increased as CO2 levels rose up to 400 ppm before reaching saturation. In contrast to S. dohrnii, the growth rate of H. akashiwo increased with CO2 increasing up to 1000 ppm, and then CO2 saturated. In addition, H. akashiwo showed a slower growth rate than S. dohrnii for all CO2 concentrations, aside from 1000 ppm, and the Michaelis-Menten equations revealed that the half-saturation constant of H. akashiwo was higher than S. dohrnii. An increase in CO2 concentration was seen to significantly affected the POC: Chl-a of both S. dohrnii and H. akashiwo, however, the effects on their elemental composition were minimal. Overall, our findings indicate that H. akashiwo had a more positive reaction to elevated CO2 than S. dohrnii, and with higher nutrient utilization efficiency, while S. dohrnii exhibited higher carbon fixation efficiency, which is in line with their respective carbon concentrating mechanisms. Consequently, elevated CO2, either alone or in combination with other limiting factors, may significantly alter the relative relationships between these two harmful algal blooms (HAB) species over the next century.

1 Introduction

The ocean absorbs about 30% of anthropogenic emissions per year (Gattuso et al., 2015), and the pH of the ocean surface has decreased by 0.1 units since the Industrial Revolution compared to pre-industrial levels due to the accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere brought by human activity, suggesting a 30% rise in acidity (Orr et al., 2005). In addition, the pH of the ocean surface is expected to fall to 7.8 by the end of the century (Gazeau et al., 2013). This would mean a 150-200% increase in acidity. However, microalgae play an extremely important role in ecosystems by using carbon dioxide for photosynthesis to produce carbohydrates, proteins, pigments and lipids, which are powerful consumers of carbon dioxide.

Over the past 70 years, researchers have studied and advanced the cultivation of microalgae. Some factors that impact algal development have been thoroughly researched, such as light irradiation, temperature and nutrient concentration (Fu et al., 2007), while others, such as the effects of pH and CO2 on microalgal growth, still merit more research. Algae thrive in water, where the CO2 concentration is significantly lower than in the air, and the diffusion rate of CO2 in water is only one 10,000th of that in the atmosphere. In order to response to this low CO2 concentration, algae have developed a specialized CO2-concentration mechanism (CCM) to elevate the CO2 concentration inside the cell. The great efficiency of algal photosynthesis relies on CCM at the catalytic site of the carboxylating enzyme Rubisco, thus enhancing CO2 fixation (Burlacot et al., 2021). CCMs have been developed by several algae species, such as diatoms and dinoflagellates to increase the CO2 concentrations close to the Rubisco active site. Among these processes is a bicarbonate uptake active transport system (Huertas and Lubian, 1998). For the main carbon-fixing enzyme Rubisco, CO2 is the preferred carbon substrate in algae. Carbon fixation may be encouraged by increased CO2 for certain species but not for others since Rubisco efficiency can vary between different groups (Beardall et al., 2009).

Microalgae can be cultured in a variety of ways, such as one-off culture, continuous culture and semi-continuous culture, each of which has its advantages and disadvantages (Hofmann et al., 2019). In the semi-continuous culture process, the frequent addition of fresh medium not only increases the nutrients in the medium, but also decreases the biological density and enhances light transmission. This leads to improved photosynthetic efficiency and growth rate of algal cells, ultimately helping to maintain a favorable growth state for the cells. (Guinotte and Fabry, 2008). Regeneration rate and initial density, as important parameters in semi-continuous culture mode, have important effects on the growth and intracellular biochemical components of microalgae.

Over the next 50 to 100 years, it is projected that greenhouse warming will cause average sea surface temperatures to increase by as much as 5°C. This rise in temperature, coupled with increased precipitation, runoff and ice melting, will likely result in lower surface salinities in many parts of the ocean (Fu et al., 2012). While CO2, as a major greenhouse gas, gradually increases in air carbon dioxide concentration, leading to a gradual increase in the partial pressure carbon dioxide (pCO2) of seawater, so the potential impact of ocean acidification (OA) on the growth of marine phytoplankton and the rate of biomineralization has attracted attention. Recent evidence demonstrates that some coastal ecosystems and estuaries are already experiencing significant levels of anthropogenic acidification (Landsberg, 2002; Anderson et al., 2008; Jeong et al., 2013). Due to the frequent occurrence of harmful algal blooms (HABs) in these ecosystems, it is crucial to study their response to changing CO2 and/or pH, either individually or in conjunction with other variables. Both Skeletonema spp and flagellate Heterosigma spp are widely distributed in coastal waters globally and have broad range of thermohaline tolerances (Imai and Itakura, 1999). When the temperature and salinity are suitable, it can proliferate in large numbers to create red tides, which can have negative impacts on marine ecosystems. In China, reports of red tide brought on by Skeletonema spp. and flagellate Heterosigma spp. offshore seas exist (Qing-Qing et al., 2017; Li et al., 2021). Meanwhile, these common species of harmful algal blooms have been responsible for red tides in numerous countries, leading to widespread fish deaths and substantial economic repercussions (Khan et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 2006). Although there have been some experimental studies of ocean acidification and nutrient changes on harmful algal blooms (Kempton et al., 2008; Sun et al., 2011; Thangaraj and Sun, 2020), very few studies have explored the impact of seven different CO2 concentrations.

In this experiment, the algae species were taken from Chinese coastal waters. Although it would be more realistic to cultivate them under natural conditions, since these temporal fluctuations are impossible to realistically simulate in laboratory cultures, our experiments used the current temperate offshore summer temperature of 25°C and seven different pCO2 values. The cell physiological and biochemical reposes to these conditions were then compared with the aim of revealing the possible effects of global change on interspecies competition and dominance in harmful algal bloom events.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Alga sources and growth conditions

Skeletonema dohrnii was isolated from the central Yellow Sea (China), and Heterosigma akashiwo was isolated from Qinhuangdao, a nearshore city at the north Bohai Sea (China) (Thangaraj et al., 2019), and both of them were pre-cultured in f/2 seawater medium and then transferred to the Aquil medium. In the experiment, Skeletonema dohrnii were grown in Aquil medium (100 μmol L-1 NO3-, 100 μmol L-1SiO44-, 10 μmol L-1PO43-) (Price et al., 1989). While Heterosigma akashiwo were cultured in an enriched artificial medium to prevent nutrient limitation (500 μmol L-1 NO3-, 100 μmol L-1SiO44-, 50 μmol L-1PO43-). Each experiment had three biological replicates. These two algae were both aerated with CO2 gas and grown under cool white fluorescent light with a 12:12 h light: dark cycle at 25°C and an irradiation of 160 μmol photo m-2s-1.

2.2 Experiment design

To reduce contamination, accurate methods were used in this study. Experiments were performed in triplicate 1 L acid-washed and autoclaved conical bottles. The experiments were conducted using a semi-continuous culture method to measure the effect of CO2 on domestication and steady-state growth (Fu et al., 2008). The pCO2 of the incubators was controlled at seven different partial pressure levels (100 ppm, 200 ppm, 300 ppm, 400 ppm, 500 ppm, 1000 ppm and 2000 ppm) by controlling the inflow of ambient air and pure CO2 filtered by 0.2 μm. The seawater medium was bubbled at the corresponding CO2 concentration for at least 24h before the experiment, with continuous aeration, starting from the first day of the experiment to the end of the last day of the experiment. Daily dilutions were made based on growth rate measured from in vivo chlorophyll fluorescence using a Turner 10AU fluorometer (Turner Designs), and the dilution volume was adjusted to maintain a constant growth rate and to bring the biomass up to pre-dilution levels. Final sampling took place when steady state growth was achieved for each growth condition, which is defined as no significant difference (less than 10%) in growth rates after at least three consecutive dilutions.

2.3 Cell abundance and growth rate

Daily live microscopic cell counts and in vivo fluorescence (measured with a Turner 10AU fluorometer) were used to monitor growth rates. Cell abundance was measured using a hemocytometer counting chamber under an optical microscope. The specific growth rate (μ) was determined as Equation 1:

where μ=growth rate (d-1), X1=cellular density (cells mL-1) at time X1, X2 = cellular density (cells mL-1) at time X2, and Δ t refers to the time period between X1 and X2 (d).

The maximum growth rate was estimated by numerically maximizing the equation (Moorhead and Weintraub, 2018). The growth rates of all the species at all the CO2 levels were fitted to Michaelis–Menten equation as Equation 2:

to estimate maximum growth rates (μmax) and half saturation constants (K1/2) for CO2 concentration (S). In the CO2 curve experiments growth rates for both these autotrophic species were assumed to be zero at 0 ppm CO2 (Zhu et al., 2017).

2.4 Elemental and Chl-a analysis

To analyze particulate organic carbon (POC) and particulate organic nitrogen (PON), 100 ml culture samples from each of the triplicate bottles were filtered onto precomputed (450°C, 4 h) GF/F glass fiber filter (0.7 μm, 25 mm, Whatman) under low vacuum. POC and PON were then analyzed by a Costech ECS4010 Elemental Analyzer (Costech International S. P. A., Milan, Italy) following the protocol of Fu et al. (2007). Samples (50ml) for particulate organic phosphorus (POP) were obtained in the same manner as described above. Each treatment was filtered onto 0.6 μm polycarbonate filters (GE Healthcare, CA) and dried in an oven at 60 °C overnight for biogenic silica (BSi) analysis using a 5 mL aliquot of S. dohrnii culture. POP was measured as Fu et al. (2005). BSi analysis followed Brzezinski and Nelson (1995). The values of cell quota were derived from the measured values divided by manual cell counts on the last day of experiment (when the cultures are harvested).

For chlorophyll-a (Chl-a) determination, the cultures were from each treatment replicate filtered onto GF/F filters (0.7 μm, 25 mm, Whatman) and extracted with 90% acetone at −20°C for 24 h for analysis (Maat et al., 2014). The Chl-a concentration was then determined by using the Turner-Designs Trilogy fluorometer (model 10-AU, TurnerBioSystems, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and calculated based on the formula of Parsons (Welschmeyer, 1994).

2.5 Sinking rate

The sinking rate of phytoplankton was measured using the SETCOL method (Bienfang, 1981), which involves a vertical sedimentation column. Three water outlets were sealed, and the algal liquid was poured into the column, filling it completely. The column was then sealed and placed in the dark at a consistent temperature for 3 hours. The volume of algal liquid in each layer was measured, then filtered onto a GF/F filter and kept at -20°C for the final determination.

2.6 pH and dissolved inorganic carbon measurement

The pH in each bottle was monitored every day using a microprocessor pH-meter (pH S210-K, Switzerland), calibrated with pH 7 and 10 buffer solutions. CO2 equilibration was also verified using dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) measurements. The dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) content was determined using a total organic carbon analyzer (TOC-VCPN, Shimadzu, Japan). The carbon dioxide partial pressure content in solution was calculated with the help of CO2 sys (Pierrot and Lewis, 2011) to verify the carbon dioxide gradient of the experimental treatments (data not shown).

2.7 Statistical analysis

In this study, SPSS21.0 and Prism9 was used for statistical analysis and one-way ANOVA was carried out to evaluate the effects of pCO2 on various indicators of algae. Tukey HSD multiple comparisons were used to examine differences between treatment groups. The measured data were presented as mean values ± standard deviation (SD). The value of p<0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

3 Results

3.1 Growth profiles of S. dohrnii and H. akashiwo

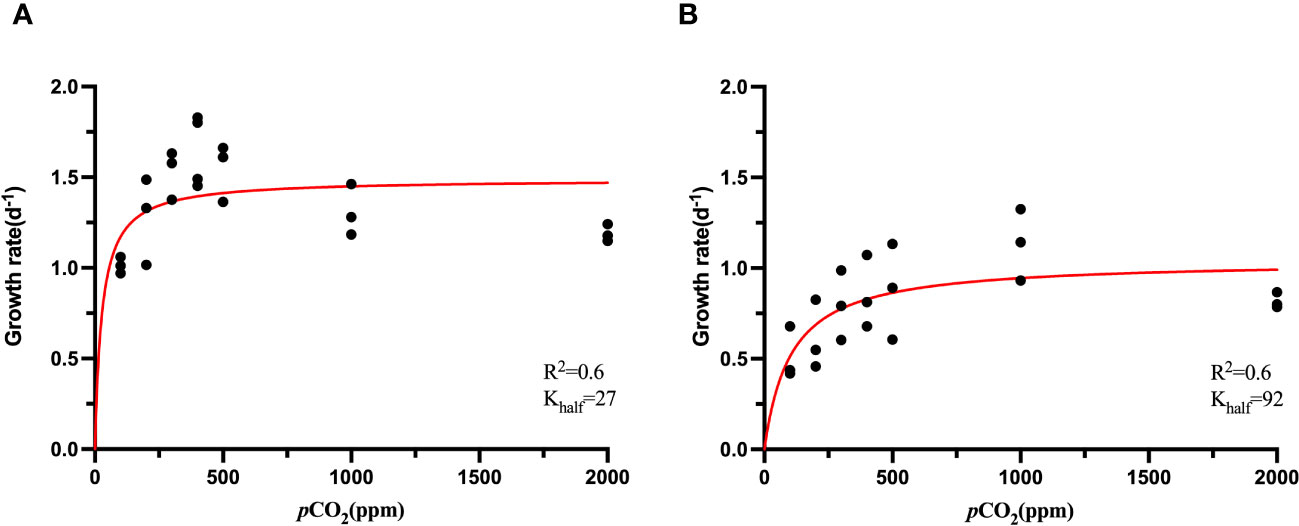

The cell growth of S. dohrnii and H. akashiwo were affected significantly under elevated pCO2 as shown in Figure 1. The growth rate of S. dohrnii increased as CO2 concentration rose from 100 ppm to 400 ppm, achieving saturation at 500 ppm and 1000 ppm and the maximum growth rate was 1.50 d-1 (Figure 1A). However, the growth rate of S. dohrnii at 2000 ppm was decreased when compared to the growth rate at 400 ppm (p<0.05).

Figure 1 CO2 functional response curves of showing specific growth rate (and fitted curves) across a range of CO2 concentration from ~100 to ~2000 ppm of S. dohrnii (A) and H. akashiwo (B) at 25°C. (Confidence interval 95%).

The growth rate of H. akashiwo was considerably impacted by CO2 concentration at 25°C (p<0.05). Similar to the trend of S. dohrnii, the growth rate of H. akashiwo was limited at low CO2 concentrations, and unlike S. dohrnii, H. akashiwo grew continuously as the CO2 concentration climbed from 100 to 1000 ppm until becoming saturated at 1000 ppm and 2000 ppm (Figure 1B). The maximum growth rate was 1.13 ± 0.20 d-1 at 1000 ppm, which was close to the theoretical growth rate of 1.03 d-1 fitted by Michaelis-Menten equation (Table 1). Although the growth rate of S. dohrnii and H. akashiwo both decreased slightly at 2000 ppm, the decrease of S.dornii was more remarkable than H. akashiwo when relative to 400 ppm. This inhibition may be attributed to the decrease in pH at 2000 ppm when the cells require haoadditional energy to maintain intracellular pH homeostasis.

Table 1 Comparison of the curve fitting results for maximum growth rate (d-1) and half-saturation constants (K1/2), calculated from the CO2 functional response curves of S. dohrnii and H. akashiwo at 25°C.

3.2 Cell quotas and elemental ratios

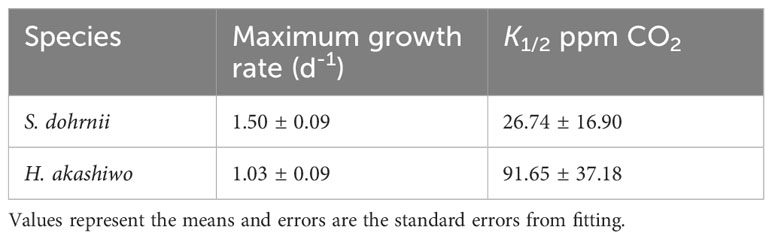

Generally, as is shown in the Figure 2, there was no significant (p>0.05) variation in the values of the cell quota of N (QN) and the cell quota of P (QP) (Figures 2B, C), while increasing CO2 resulted in the cell quota of C (QC) of S. dohrnii varied considerably (p<0.05, Figure 2A). Specifically, QC in S. dohrnii at 100 ppm, 400 ppm, and 500 ppm was significantly lower than that at 200ppm and 1000ppm, and it was also significantly higher at 200 ppm, 300 ppm and 1000 ppm than that at 400 ppm and 2000 ppm(p<0.05).

Figure 2 The effects of CO2 on the C quota (pmol cell-1), N quota (pmol cell-1), P quota (pmol cell-1) of S. dohrnii (A–C) and H. akashiwo (D–F) in each of the seven CO2 treatments. Error bars denote standard deviations of averaged results from three replicate bottles. The scales of the y-axes are very different.

In comparison with S. dohrnii, the QC of H. akashiwo varied under different carbon dioxide settings, and QC, QP and QN of H. akashiwo reached the maximum value at 300 ppm (Figures 2D–F). However, this shift trend was not significant (p>0.05). Besides, with increasing CO2 concentration, the QC in H. akashiwo showed a pattern of increasing, then decreasing, and then increasing again with increasing CO2 concentration. Likewise, QN displayed a trend of increasing, then decreasing, and then increasing again. Variations in CO2 concentration affected QN in much the same manner as QC (Figure 2B).

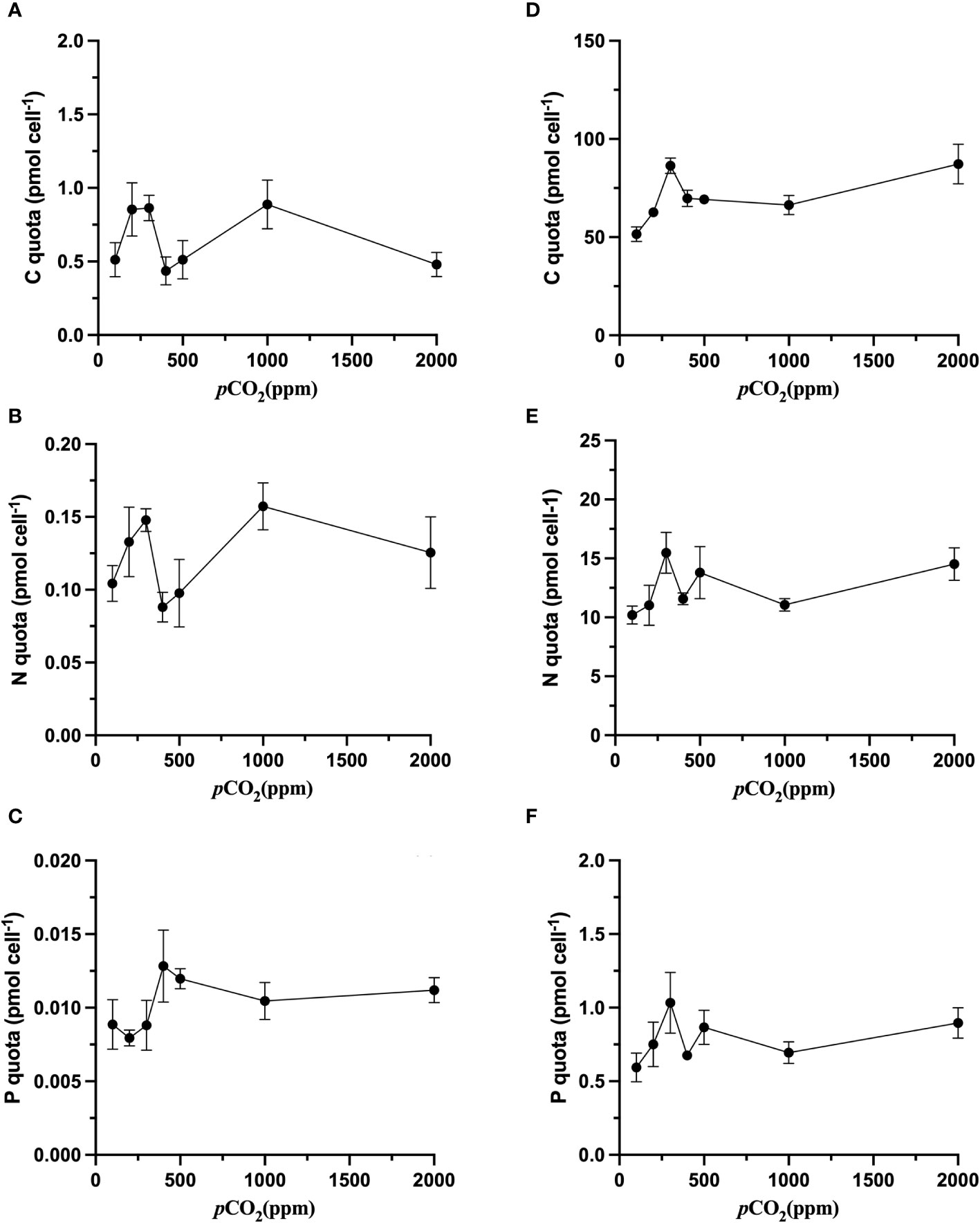

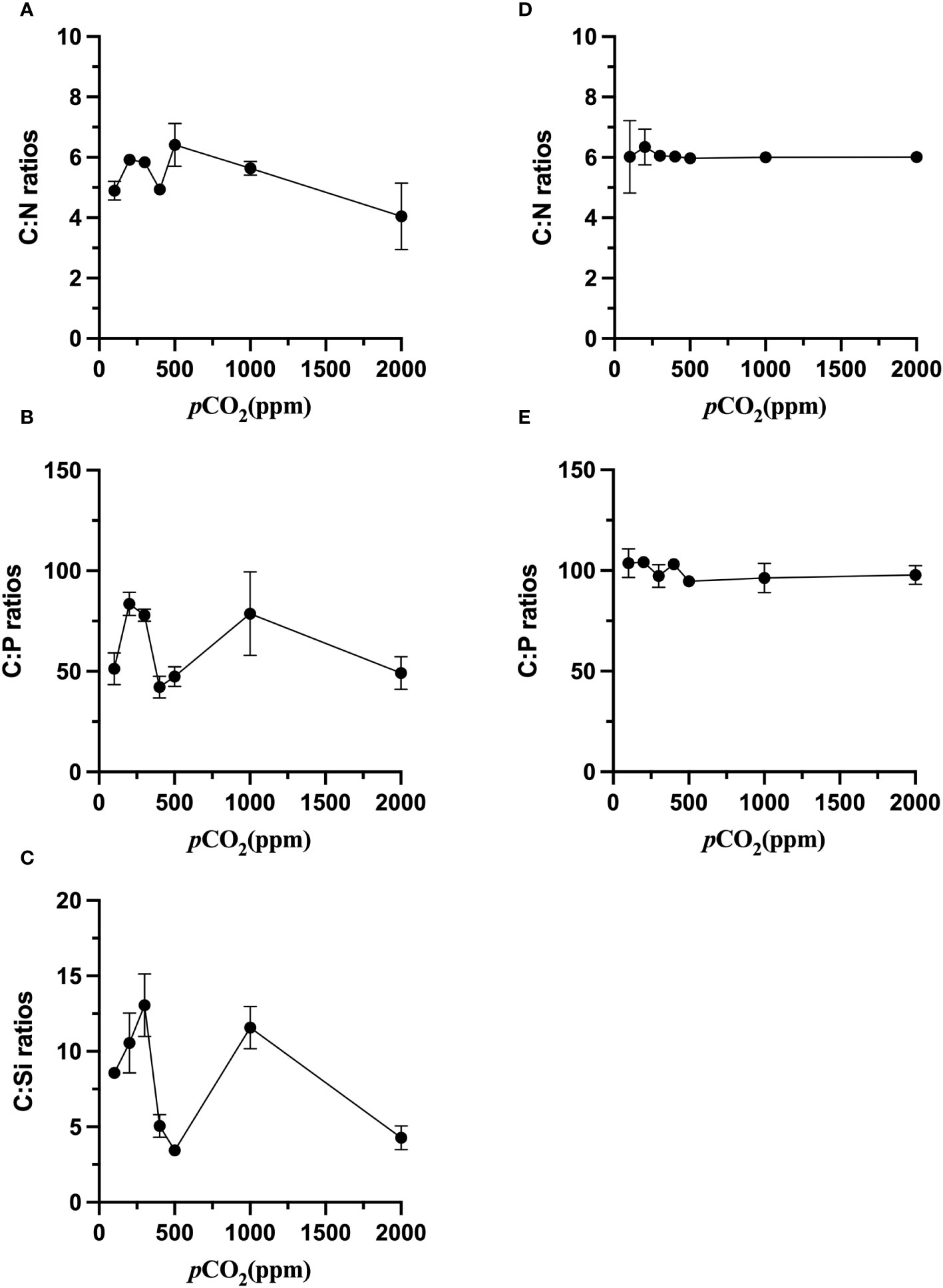

The response of cellular elemental composition to carbon dioxide is analyzed at four levels: low carbon dioxide partial pressures (100 ppm, 200 ppm, 300 ppm), current carbon dioxide partial pressures (400 ppm and 500 ppm), end-of-century carbon dioxide partial pressure (1000 ppm), and a very high partial pressure (2000 ppm). The C: N of S. dohrnii was not substantially altered when the carbon dioxide concentration increased (p>0.05, Figure 3A). However, the C: P and C: Si ratios were altered considerably (p<0.05, Figures 3B, C). The C: N of S. dohrnii at 200, 300 and 1000 ppm were significantly higher than that at 400, 500 and 2000 ppm (p<0.05). The ratio of C: Si of S. dohrnii were lower at present air pressure and very high carbon dioxide levels, but no significant difference compared to low pCO2.

Figure 3 Elemental ratios of S. dohrnii (A–C) and H. akashiwo (D, E) in the seven CO2 treatments. Error bars denote standard deviations of averaged results from three replicate bottles.

Contrary to the S. dohrnii, the C: N ratios of H. akashiwo were not significantly changed in different CO2 treatments (p>0.05, Figure 3D). The C: P of the cells of H. akashiwo were significantly higher (p<0.05) than those of S. dohrnii at 100 ppm, 400 ppm, 500 ppm and 2000ppm (Figure 3E). Higher C: P was founded in the cells of H. akashiwo compared to S. dohrnii, implying that their contributions to the oceanic carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles are different.

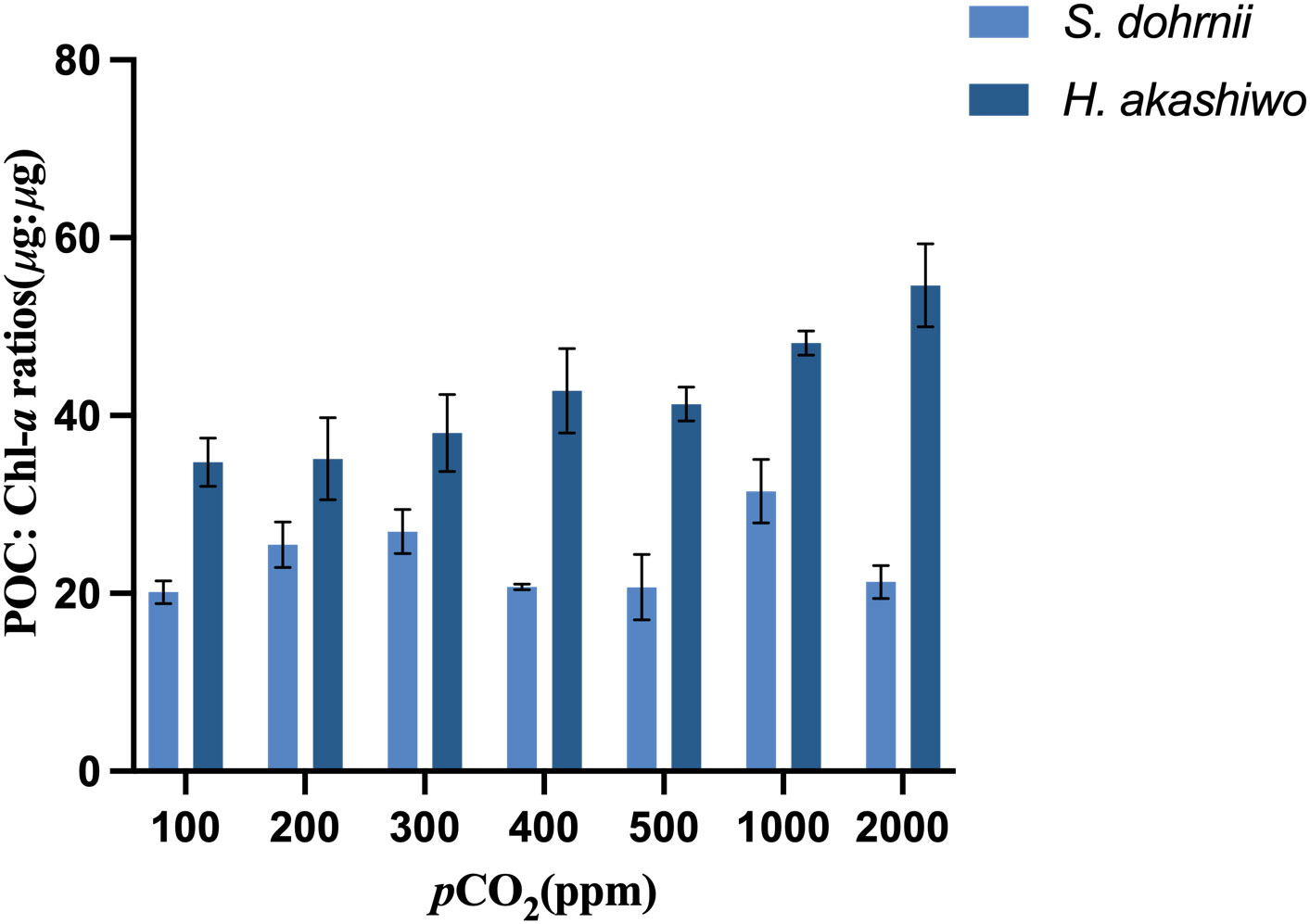

3.3 POC: Chl-a ratios

The POC: Chl-a ratios of S. dohrnii were influenced by changing carbon dioxide concentration (Figure 4). The POC: Chl-a ratios of S. dohrnii were significantly higher at 1000 ppm than 100 ppm, 400 ppm, 500 ppm and 2000 ppm(p<0.05). Carbon dioxide concentration also had a significant effect (p<0.05) on POC: Chl-a ratios of H. akashiwo. The POC: Chl-a of H. akashiwo tended to increase with increasing carbon dioxide and was significantly higher at a very high carbon dioxide partial pressure (2000 ppm) than at low carbon dioxide partial pressures (100, 200, 300 ppm) and current carbon dioxide partial pressures (400 ppm and 500 ppm). Besides, the POC: Chl-a ratios of H. akashiwo were higher than S. dohrnii at all the CO2 levels tested.

Figure 4 POC: Chl-a ratios of S. dohrnii and H. akashiwo in each of the seven CO2 treatments. Error bars denote standard deviations of averaged results from three replicate bottles.

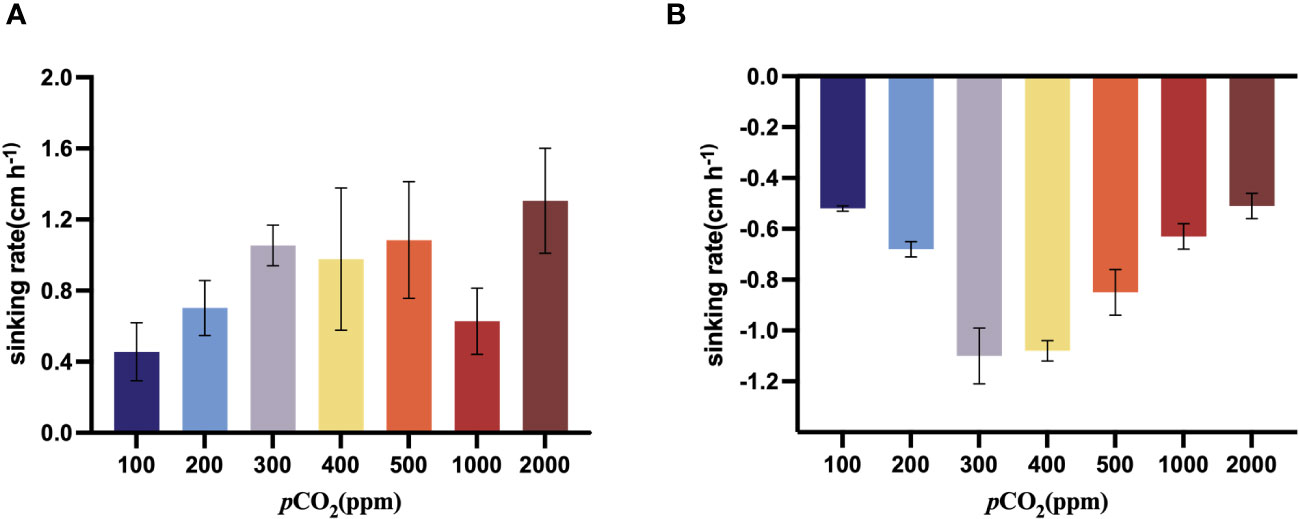

3.4 Sinking rate

As the CO2 concentration increased from 100 ppm to 500 ppm, the sinking rate of S. dohrnii tended to increase, when it came to 1000 ppm, the sinking rate began to decrease. The sinking rate of S. dohrnii at 2000 ppm was significantly (p<0.05) higher than that at 100ppm (Figure 5A). The sinking rate of H. akashiwo was negative at all carbon dioxide concentration gradients from 100 ppm to 2000 ppm, which indicated that H. akashiwo did not sink but ascend under the experimental conditions. Furthermore, as the carbon dioxide concentration increases from 100 ppm to 400 ppm, the ascent rate of H. akashiwo gradually increases. However, as the carbon dioxide concentration rises from 400 ppm to 2000 ppm, the ascent rate of H. akashiwo decreases continuously (Figure 5B). The ascent rate of H. akashiwo exhibits a pattern of initially increasing and then decreasing with the carbon dioxide concentration, reaching its maximum value of 4.67cm h-1 at then carbon dioxide concentration of 400ppm. The ascent of this algal species is significantly lower at both low carbon dioxide concentration of 100 ppm and high carbon dioxide concentration of 2000ppm compared to the ascent rate at 400ppm (p<0.05).

Figure 5 Sinking rate (cm/h) of S. dohrnii (A) and H. akashiwo (B) in the seven CO2 treatments. Error bars denote standard deviations of averaged results from three replicate bottles.

4 Discussion

Our research showed that S. dohrnii and H. akashiwo reacted in different ways when exposed to different CO2 levels, as indicated by their growth rate and elemental composition.

According to the study, the growth rate of S. dohrnii was limited when the CO2 concentration decreased to below 400 ppm, which is crucial due to the fact that CO2 levels usually drop to extremely low levels during algal blooms in coastal waters (Jef et al., 2018). S. dohrnii may benefit from higher summertime water temperature, particularly during later algal blooms when the pCO2 of the water is low. Under the current atmospheric CO2 level, the growth rate of S. dohrnii has reached a saturation point. According to our findings, the growth rates of H. akashiwo will likely be stimulated by elevated CO2 within the range predicted for the next century, while the growth rate of S. dohrnii will remain unchanged. As ocean acidification (OA) continues, it is possible that the current advantage of S. dohrnii will diminish and H. akashiwo will begin to benefit more in the future. This could result in an increase in the frequency and severity of red tides caused by H. akashiwo. It is possible that the red tide is shifting from being mainly diatom dominated to being mainly dinoflagellate dominated. In turn, this could alter the phytoplankton community composition off the coast of China, which could have an effect on the food web and the carbon and nutrient biogeochemical cycling.

In practice, experimental evolution often uses growth rate or competitive ability as a measure of fitness for selection experiments conducted in semi-continuous (batch) culture settings, or population carrying capacity as a measure of fitness in continuous culture (Collins et al., 2014). Consistent with earlier research, the results show that CO2 from current levels to end-of-century levels has minimal effects on various phytoplankton species (Joel, 1999; Wu et al., 2014; Hutchins and Fu, 2017). According to our study, the growth rate of S. dohrnii was not raised at 400 ppm, and our experimental results agreed fairly well with the notion that the growth and photosynthesis of Skeletonema costatum in the current atmospheric CO2 concentrations have reached saturation state (Gao et al., 2019). As per the model, the growth rate of H. akashiwo is predicted to increase by 40% as the CO2 levels transition from the current level to 700 ppm (Schippers et al., 2004). This hypothesis was also well supported by our experimental findings which showed that raising CO2 to 1000 ppm would result in a 32.6% increase in H. akashiwo growth rate compared to the current CO2 levels.

Growth limitation by CO2 in marine cyanobacteria, green algae and diatoms has been reported from both field and lab work (Ashida et al., 2003: Fu et al., 2007). As numerous species of the phytoplankton community have an effective carbon-concentrating mechanism that allows them to evade the CO2 limit in lower levels of pCO2, changes in carbon dioxide levels have minimal effect on them (Reinfelder, 2011). Phytoplankton utilize ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase (Rubisco) in order to fix CO2. The half-saturation constant of Rubisco for CO2 is approximately 20~70μM (Badger et al., 1998), while the soluble CO2 in seawater is only 10~15μM. To overcome this, phytoplankton have developed strategies such as the use of HCO3- and Carbon-Concentrating Mechanisms (CCMs) to deal with the insufficient CO2 levels (Giordano et al., 2005). The CCMs consist of an active transport system for bicarbonate uptake and bicarbonate dehydration catalyzed by intracellular carbonic anhydrase (CA) to form CO2 (Fu et al., 2008; Garcia et al., 2011). When the CO2 concentration in the environment increases, the inorganic carbon uptake mechanism of algae is activated, and the CCMs are down-regulated, leading to a decrease in the ability of algal cells to utilize HCO3-, so that the energy originally used for the transfer and utilization of HCO3- is reduced and converted to photosynthesis, thus improving photosynthetic efficiency and promoting the growth of algae (Qiu and Gao, 2002; Ashida et al., 2003).

Variations in Rubisco efficiencies can be seen between different microalgae (Tortell, 2000). H. akashiwo does not possess the CCMs making it highly dependent on CO2 for inorganic carbon (Badger et al., 1998). The lack of CCMs in H. akashiwo would prevent it from directly or indirectly absorbing HCO3-, so the ability to uptake CO2 is the only source of energy may help to explain why increased CO2 stimulates the growth of this alga (Hansen, 2002).

Through photosynthesis, algae synthesize organic matter, and this can cause a shift in the C, N and P composition and content of the algal cell. Our findings demonstrate that a rise in CO2 levels had an effect on the cell quota of C (QC) and N (QN) of S. dohrnii and H. akashiwo. The cell quota of C of S. dohrnii was 80% lower at 2000ppm than that at 1000ppm and there were no significant differences in QN. While the QC, QN of H. akashiwo were more sensitive to the changes of pCO2. One explainable reason is that the disturbance of seawater can dramatically alter the partial pressure of CO2, but causes only relatively small changes in HCO3- availability, and H. akashiwo does not have the potential to take up HCO3- directly or to utilize it indirectly by using extracellular carbonic anhydrase (Nimer et al., 1999; Hansen, 2002). Thus, it may be reasonable that cell number and elemental composition are affected by changes in CO2 in H. akashiwo. A future increase in atmospheric pCO2 concentration would have the same effect. The QC and QN of H akashiwo were both increased by elevated CO2. Although the biochemical composition of both species was not determined in this study, it is not clear whether the changes in QC and QN in H. akashiwo under CO2 enrichment was caused by an increase in carbohydrate or protein synthesis. Consequently, if the red tides transition from S. dohrnii to H akashiwo, there will be an elevated presence of carbon and nitrogen in biogeochemical cycling. Besides, it is noteworthy that S. dohrnii but not H akashiwo, had an increased QN under elevated CO2 over 400ppm.This finding may suggest that the S. dohrnii may be more vulnerable to nitrogen limitation under future environmental conditions. Thus, the current competitive advantage that S. dohrnii enjoys under elevated CO2 could potentially be negated in estuaries where N is the limiting nutrient for bloom development.

Current study reveals that phytoplankton are quite are variable. Changes in growth rate and CO2 availability can occur with no change in elemental composition (both strains of T. weissflogii and T. oceanica), or with large differences in elemental stoichiometry (T. pseudonana, D. salina) (King et al., 2015). The effects of pCO2 variation on the elemental ratios of H. akashiwo were minimal relative to those of S. dohrnii. In this experiment, the effect of CO2 concentration changes on the elemental composition of the cells of H. akashiwo was slight, but there was a significant difference on C: Chl-a. In general, a lower POC: Chl-a ratio indicates higher carbon fixation efficiency in plants (McGrath and Lobell, 2013). This implies that plants more effectively convert photosynthetic products (such as glucose) into organic carbon compounds, rather than wasting energy in the photosynthesis process. This high-efficiency carbon fixation enables plants to be more productive in terms of growth and production. In the case of H. akashiwo, a higher ratio suggests higher nutrient utilization efficiency, while S. dohrnii exhibits higher carbon fixation efficiency. The fluctuating POC: Chl-a ratio in S. dohrnii might imply a more complex or variable physiological response to CO2 levels, which might be influenced by other environmental or internal factors not represented in this data. Some results showed that elevated CO2 concentration increases the C: N ratio or C: P ratio of planktonic algae (Engel et al., 2005), especially in the low trophic state (Li et al., 2012). However, it has also been shown that changes in CO2 concentration did not affect elemental chemical composition (Qiu and Gao, 2002). Olischlaeger et al. (2014) previously studied the changes in C: N of algae in response to high CO2 concentrations, and the results showed that at the same temperature, the changes in algal C: N caused by high CO2 concentrations were not significant. The increased carbon and nitrogen contents for H. akashiwo grown under elevated CO2 could be due to increased carbon fixation and a higher uptake of NO3- (Bi et al., 2012). In the future, the effect of CO2 on phytoplankton elemental composition must be taken into account together with other environmental parameters, such as nutrition and light availability, which can also have a significant impact on stoichiometry (Finkel et al., 2010).

The study of phytoplankton sinking rate is crucial for a thorough understanding of the effectiveness of carbon sinks since direct carbon sedimentation by phytoplankton is an essential pathway for oceanic carbon sinks (Sun, 2011). The rate of sedimentation of marine phytoplankton is affected by a variety of factors, including the physiological condition of the phytoplankton, lack of nutrients, and disruption of the ocean.

When the algae are in good physiological condition, the cells are active and the sinking rate is slow, and vice versa (Wang et al., 2022). Diatoms are a class of unicellular or multicellular algae rich in silicon, and as an important structural protein, the silicophilic proteins play an important role in the silicification process (Martin-Jézéquel et al., 2000). The high sedimentation rate of S. dohrnii at 500 ppm may be attributed to the high content of Si in the algal cells at this time, and the pro-silica proteins on the surface of the algal cells are able to combine with the silicate in the environment to promote the deposition and polymerization of silicate, which ultimately causes the diatom cells to form a hard siliceous shell on their exterior, thus accelerating its sedimentation rate. Research has revealed that a decrease in pH values will slow down the dissolution of silicon (Si) in sinking particulate matter and ocean acidification will cause a 17 ± 6% increase in the silicon (Si) to nitrogen (N) elemental ratio in sinking biogenic material (Taucher et al., 2022). Moreover, the silicophilic proteins in diatoms may also be involved in a variety of other biological processes, such as cell adhesion, signaling, and so on (Martin-Jézéquel et al., 2000). Phytoplankton with spines and horns in their cell structure or with flagella generally typically have a lower sinking rate, whereas H. akashiwo has two unequal flagella with some swimming ability, which explains why H. akashiwo prefers to ascent rather than sink(Tobin et al., 2013).

The two species of harmful algal blooms inhabiting the same environment reacted differently to predicted global changes, suggesting that the impact of increasing CO2 levels will be specific to certain taxa or even individual species. It is likely that H. akashiwo will grow more quickly than S. dohrnii in the coming decades, providing it with an advantage in interspecific competition. Larger diatoms (diameter >40 μm) were more likely to be stimulated by future increases in CO2 availability, and the increase in growth rate by pCO2 was size-dependent. Smaller diatom species showed a 5% increase in growth rate, while the largest diatom species showed a 30% increase in growth rate (Wu et al., 2014). Changes in cell nutrition ratios and quotas caused by CO2 further point to a connection between continuous eutrophication, which has already been linked to HAB blooms and global change variables.

The assimilation of inorganic carbon by phytoplankton through light energy is an important basis of the ocean’s material cycle and energy flow, and their conversion of dissolved CO2 to the particulate state is a vital biological process of the “biological pump”. The amount of CO2 that is taken up by the oceans from the atmosphere depends on the biological pump, as well as on the effects of ocean acidification. The reaction of phytoplankton to ocean acidification and other environmental factors is determined by species characteristics, cell size and adaptability to the environment; hence, differences in the impacts of ocean acidification on the physiological processes of phytoplankton will inevitably lead to changes in the composition of the phytoplankton community. Therefore, in order to accurately predict the effects of future alterations in temperature and CO2 levels, the interactive effects of other variables such as precipitation, stratification, light, and nutrient inputs on the physiology of phytoplankton.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The manuscript presents research on animals that do not require ethical approval for their study.

Author contributions

JQ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. MJ: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. JS: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was financially supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China grants (41876134), and the Changjiang Scholar Program of Chinese Ministry of Education (T2014253) awarded to JS.

Acknowledgments

JS also acknowledges support by Projects of Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (SMI2021SP204, SML2022005).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Anderson D. M., Burkholder J. M., Cochlan W. P., Glibert P. M., Gobler C. J., Heil C. A., et al. (2008). Harmful algal blooms and eutrophication: Examining linkages from selected coastal regions of the United States. Harmful Algae 8, 39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2008.08.017

Ashida H., Saito Y., Kojima C., Kobayashi K., Ogasawara N., Yokota A. (2003). A functional link between RuBisCO-like protein of Bacillus and photosynthetic RuBisCO. Science 302, 286–290. doi: 10.1126/science.1086997

Badger M. R., Andrews T. J., Whitney S. M., Ludwig M., Yellowlees D. C., Leggat W., et al. (1998). The diversity and coevolution of Rubisco, plastids, pyrenoids, and chloroplast-based CO2-concentrating mechanisms in algae. Can. J. Bot.-Rev. Can. Bot. 76, 1052–1071. doi: 10.1139/b98-074

Beardall J., Stojkovic S., Larsen S. (2009). Living in a high CO2 world: impacts of global climate change on marine phytoplankton. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2, 191–205. doi: 10.1080/17550870903271363

Bi R., Arndt C., Sommer U. (2012). Stoichiometric responses of phytoplankton species to the interactive effect of nutrient supply ratios and growth rates. J. Phycol. 48, 539–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2012.01163.x

Bienfang P. K. (1981). SETCOL — A technologically simple and reliable method for measuring phytoplankton sinking rates. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 38, 1289–1294. doi: 10.1139/f81-173

Brzezinski M. A., Nelson D. M. (1995). The annual silica cycle in the Sargasso Sea near Bermuda. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 42, 1215–1237. doi: 10.1016/0967-0637(95)93592-3

Burlacot A., Dao O., Auroy P., Cuiné S., Li-Beisson Y., Peltier G. (2021). Alternative electron pathways of photosynthesis drive the algal CO2 concentrating mechanism. Plant Biol. 605(7909):366–371. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04662-9

Collins S., Rost B., Rynearson T. A. (2014). Evolutionary potential of marine phytoplankton under ocean acidification. Evol. Appl. 7, 140–155. doi: 10.1111/eva.12120

Engel A., Zondervan I., Aerts K., Beaufort L., Benthien A., Chou L., et al. (2005). Testing the direct effect of CO2 concentration on a bloom of the coccolithophorid Emiliania huxleyi in mesocosm experiments. Limnol. Oceanogr. 50, 493–507. doi: 10.4319/lo.2005.50.2.0493

Finkel Z. V., Beardall J., Flynn K. J., Quigg A., Rees T. A. V., Raven J. A. (2010). Phytoplankton in a changing world: cell size and elemental stoichiometry. J. Plankton Res. 32, 119–137. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbp098

Fu F., Warner M. E., Zhang Y., Feng Y., Hutchins D. A. (2007). Effects of increased temperature and CO2 on photosynthesis, growth, and elemental ratios in marine Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus (Cyanobacteria). J. Phycol. 43, 485–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2007.00355.x

Fu F. X., Tatters A. O., Hutchins D. A. (2012). Global change and the future of harmful algal blooms in the ocean. Mar. Ecol.-Prog. Ser. 470, 207–233. doi: 10.3354/meps10047

Fu F. X., Zhang Y., Leblanc K., San Udo-Wilhelmy S. A., Hutchins D. A. (2005). The biological and biogeochemical consequences of phosphate scavenging onto phytoplankton cell surfaces. Limnol. Oceanography 50, 1459–1472. doi: 10.4319/lo.2005.50.5.1459

Fu F.-X., Zhang Y., Warner M. E., Feng Y., Sun J., Hutchins D. A. (2008). A comparison of future increased CO2 and temperature effects on sympatric Heterosigma akashiwo and Prorocentrum minimum. Harmful Algae 7, 76–90. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2007.05.006

Gao G., Fu Q., Beardall J., Wu M., Xu J. (2019). Combination of ocean acidification and warming enhances the competitive advantage of Skeletonema costatum over a green tide alga, Ulva linza. Harmful Algae 85, 101698. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2019.101698

Garcia N. S., Fu F.-X., Breene C. L., Bernhardt P. W., Mulholland M. R., Sohm J. A., et al. (2011). Interactive effects of irradiance and CO2 on CO2 fixation and N-2 fixation in the diazotroph trichodesmium erythraeum (cyanobacteria). J. Phycol. 47, 1292–1303. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2011.01078.x

Gattuso J.-P., Magnan A., Bille R., Cheung W. W. L., Howes E. L., Joos F., et al. (2015). Contrasting futures for ocean and society from different anthropogenic CO2 emissions scenarios. Science 349, aac4722. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4722

Gazeau F., Parker L. M., Comeau S., Gattuso J.-P., O’Connor W. A., Martin S., et al. (2013). Impacts of ocean acidification on marine shelled molluscs. Mar. Biol. 160, 2207–2245. doi: 10.1007/s00227-013-2219-3

Giordano M., Beardall J., Raven J. A. (2005). CO2 concentrating mechanisms in algae: Mechanisms, environmental modulation, and evolution. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 56, 99–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144052

Guinotte J. M., Fabry V. J. (2008). “Ocean acidification and its potential effects on marine ecosystems,” in Year in Ecology and Conservation Biology 2008. Eds. Ostfeld R. S., Schlesinger W. H. (Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell), 320–342. doi: 10.1196/annals.1439.013

Hansen P. J. (2002). Effect of high pH on the growth and survival of marine phytoplankton: implications for species succession. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 28, 279–288. doi: 10.3354/ame028279

Hofmann M., Mathesius S., Kriegler E., van Vuuren D. P., Schellnhuber H. J. (2019). Strong time dependence of ocean acidification mitigation by atmospheric carbon dioxide removal. Nat. Commun. 10, 5592. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13586-4

Huertas I. E., Lubian L. M. (1998). Comparative study of dissolved inorganic carbon utilization and photosynthetic responses in Nannochloris (Chlorophyceae) and Nannochloropsis (Eustigmatophyceae) species. Can. J. Bot.-Rev. Can. Bot. 76, 1104–1108. doi: 10.1139/b98-068

Hutchins D. A., Fu F. (2017). Microorganisms and ocean global change. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17058. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.58

Imai I., Itakura S. (1999). Importance of cysts in the population dynamics of the red tide flagellate Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae). Mar. Biol., 755–762. doi: 10.1007/s002270050517

Jef H., Geoffrey A. C., Hans W. P., Bes W. I., Jolanda M. H. V., Petra M. V. (2018). Cyanobacterial blooms. Nature Reviews Microbiology 16, 471–483. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0040-1

Jeong H. J., Du Yoo Y., Lim A. S., Kim T.-W., Lee K., Kang C. K. (2013). Raphidophyte red tides in Korean waters. Harmful Algae 30, S41–S52. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2013.10.005

Joel C. (1999). Inorganic carbon availability and the growth of large marine diatoms. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 180, 81–91. doi: 10.3354/meps180081

Kempton J., Keppler C. J., Lewitus A., Shuler A., Wilde S. (2008). A novel Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae) bloom extending from a South Carolina bay to offshore waters. Harmful Algae 7, 235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2007.08.003

Khan S., Arakawa O., Onoue Y. (1997). Neurotoxins in a toxic red tide of Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae) in Kagoshima Bay, Japan. Aquacult. Res. 28, 9–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.1997.tb01309.x

King A. L., Jenkins B. D., Wallace J. R., Liu Y., Wikfors G. H., Milke L. M., et al. (2015). Effects of CO2 on growth rate, C: N: P, and fatty acid composition of seven marine phytoplankton species. Mar. Ecol.-Prog. Ser. 537, 59–69. doi: 10.3354/meps11458

Landsberg J. H. (2002). The effects of harmful algal blooms on aquatic organisms. Rev. Fish. Sci. 10, 113–390. doi: 10.1080/20026491051695

Li W., Gao K., Beardall J. (2012). Interactive effects of ocean acidification and nitrogen-limitation on the Diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. PloS One 7, e51590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051590

Li X.-Y., Yu R.-C., Geng H.-X., Li Y.-F. (2021). Increasing dominance of dinoflagellate red tides in the coastal waters of Yellow Sea, China. Mar. pollut. Bull. 168, 112439. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112439

Maat D. S., Crawfurd K. J., Timmermans K. R., Brussaard C. P. D. (2014). Elevated CO2 and phosphate limitation favor micromonas pusilla through stimulated growth and reduced viral impact. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 3119–3127. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03639-13

Martin-Jézéquel V., Hildebrand M., Brzezinski M. A. (2000). Silicon metabolism in diatoms: Implications for growth. J. Phycol. 36, 821–840. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2000.00019.x

McGrath J. M., Lobell D. B. (2013). Reduction of transpiration and altered nutrient allocation contribute to nutrient decline of crops grown in elevated CO2 concentrations. Plant Cell Environ. 36, 697–705. doi: 10.1111/pce.12007

Moorhead D. L., Weintraub M. N. (2018). The evolution and application of the reverse Michaelis-Menten equation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 125, 261–262. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.07.021

Nimer N. A., Brownlee C., Merrett M. J. (1999). Extracellular carbonic anhydrase facilitates carbon dioxide availability for photosynthesis in the marine dinoflagellate Prorocentrum micans. Plant Physiol. 120, 105–111. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.1.105

Olischlaeger M., Iniguez C., Lopez Gordillo F. J., Wiencke C. (2014). Biochemical composition of temperate and Arctic populations of Saccharina latissima after exposure to increased pCO2 and temperature reveals ecotypic variation. Planta 240, 1213–1224. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2143-x

Orr J. C., Fabry V. J., Aumont O., Bopp L., Doney S. C., Feely R. A., et al. (2005). Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms. Nature 437, 681–686. doi: 10.1038/nature04095

Price N. M., Harrison G. I., Hering J. G., Hudson R. J., Nirel P. M., Palenik B., et al. (1989). Preparation and chemistry of the artificial algal culture medium Aquil. Biol. Oceanography 6 (5–6), 443–461. doi: 10.1080/01965581.1988.10749544

Qing-Qing G., Bing C., Bo Y., Chao W., Xu-Yu Z., Xian X. U. (2017). Characteristics of the red tide in the sea area of Jiangsu (Accessed September 12, 2023).

Qiu B. S., Gao K. S. (2002). Effects of CO2 enrichment on the bloom-forming cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa (Cyanophyceae): Physiological responses and relationships with the availability of dissolved inorganic carbon. J. Phycol. 38, 721–729. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2002.01180.x

Reinfelder J. R. (2011). “Carbon concentrating mechanisms in eukaryotic marine phytoplankton,” in annual review of marine science, vol. 3 . Eds. Carlson C. A., Giovannoni S. J. (Palo Alto: Annual Reviews), 291–315. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142720

Schippers P., Lurling M., Scheffer M. (2004). Increase of atmospheric CO2 promotes phytoplankton productivity. Ecol. Lett. 7, 446–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00597.x

Sun J., Hutchins D. A., Feng Y., Seubert E. L., Caron D. A., Fu F.-X. (2011). Effects of changing pCO2 and phosphate availability on domoic acid production and physiology of the marine harmful bloom diatom Pseudo-nitzschia multiseries. Limnol. Oceanogr. 56, 829–840. doi: 10.4319/lo.2011.56.3.0829

Taucher J., Bach L. T., Prowe A. E. F., Boxhammer T., Kvale K., Riebesell U. (2022). Enhanced silica export in a future ocean triggers global diatom decline. Nature 605, 696–700. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04687-0

Thangaraj S., Shang X., Sun J., Liu H. (2019). Quantitative proteomic analysis reveals novel insights into intracellular silicate stress-responsive mechanisms in the Diatom Skeletonema dohrnii. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 2540. doi: 10.3390/ijms20102540

Thangaraj S., Sun J. (2020). The biotechnological potential of the marine diatom Skeletonema dohrnii to the elevated temperature and pCO2. Mar. Drugs 18, 259. doi: 10.3390/md18050259

Tobin E. D., Gruenbaum D., Patterson J., Cattolico R. A. (2013). Behavioral and physiological changes during Benthic-Pelagic transition in the Harmful Alga, Heterosigma akashiwo: Potential for Rapid Bloom Formation. PloS One 8, e76663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076663

Tortell P. D. (2000). Evolutionary and ecological perspectives on carbon acquisition in phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 45, 744–750. doi: 10.4319/lo.2000.45.3.0744

Wang X., Sun J., Wei Y., Wu X. (2022). Response of the phytoplankton sinking rate to community structure and environmental factors in the Eastern Indian Ocean. Plants (Basel) 11, 1534. doi: 10.3390/plants11121534

Welschmeyer N. A. (1994). Fluorometric analysis of chlorophyll a in the presence of chlorophyll b and pheopigments. Limnol. Oceanography 39, 1985–1992. doi: 10.4319/lo.1994.39.8.1985

Wu Y., Campbell D. A., Irwin A. J., Suggett D. J., Finkel Z. V. (2014). Ocean acidification enhances the growth rate of larger diatoms. Limnol. Oceanogr. 59, 1027–1034. doi: 10.4319/lo.2014.59.3.1027

Zhang Y. H., Fu F. X., Whereat E., Coyne K. J., Hutchins D. A. (2006). Bottom-up controls on a mixed-species HAB assemblage: A comparison of sympatric Chattonella subsalsa and Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae) isolates from the Delaware Inland Bays, USA. Harmful Algae 5, 310–320. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2005.09.001

Keywords: CO2, Skeletonema dohrnii, Heterosigma akashiwo, Michaelis-Menten equations, half saturated constant, carbon fixation

Citation: Qin J, Jia M and Sun J (2024) Examining the effects of elevated CO2 on the growth kinetics of two microalgae, Skeletonema dohrnii (Bacillariophyceae) and Heterosigma akashiwo (Raphidophyceae). Front. Mar. Sci. 11:1347029. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1347029

Received: 30 November 2023; Accepted: 29 January 2024;

Published: 13 February 2024.

Edited by:

Wangbiao Seven Guo, Yale University, United StatesReviewed by:

Wanchun Guan, Wenzhou Medical University, ChinaAlison Webb, University of York, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2024 Qin, Jia and Sun. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jun Sun, cGh5dG9wbGFua3RvbkAxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Jiahui Qin1,2†

Jiahui Qin1,2† Jun Sun

Jun Sun