- 1Marine Environmental Research Department, Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology, Busan, Republic of Korea

- 2Frontiers Science Center for Deep Ocean Multispheres and Earth System, and Key Laboratory of Marine Chemistry Theory and Technology, Ministry of Education, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China

- 3Laoshan Laboratory, Qingdao, China

- 4Jeju Marine Research Center, Korea Institute of Ocean Science and Technology, Jeju, Republic of Korea

- 5Department of Ocean Science, University of Science and Technology (UST), Daejeon, Republic of Korea

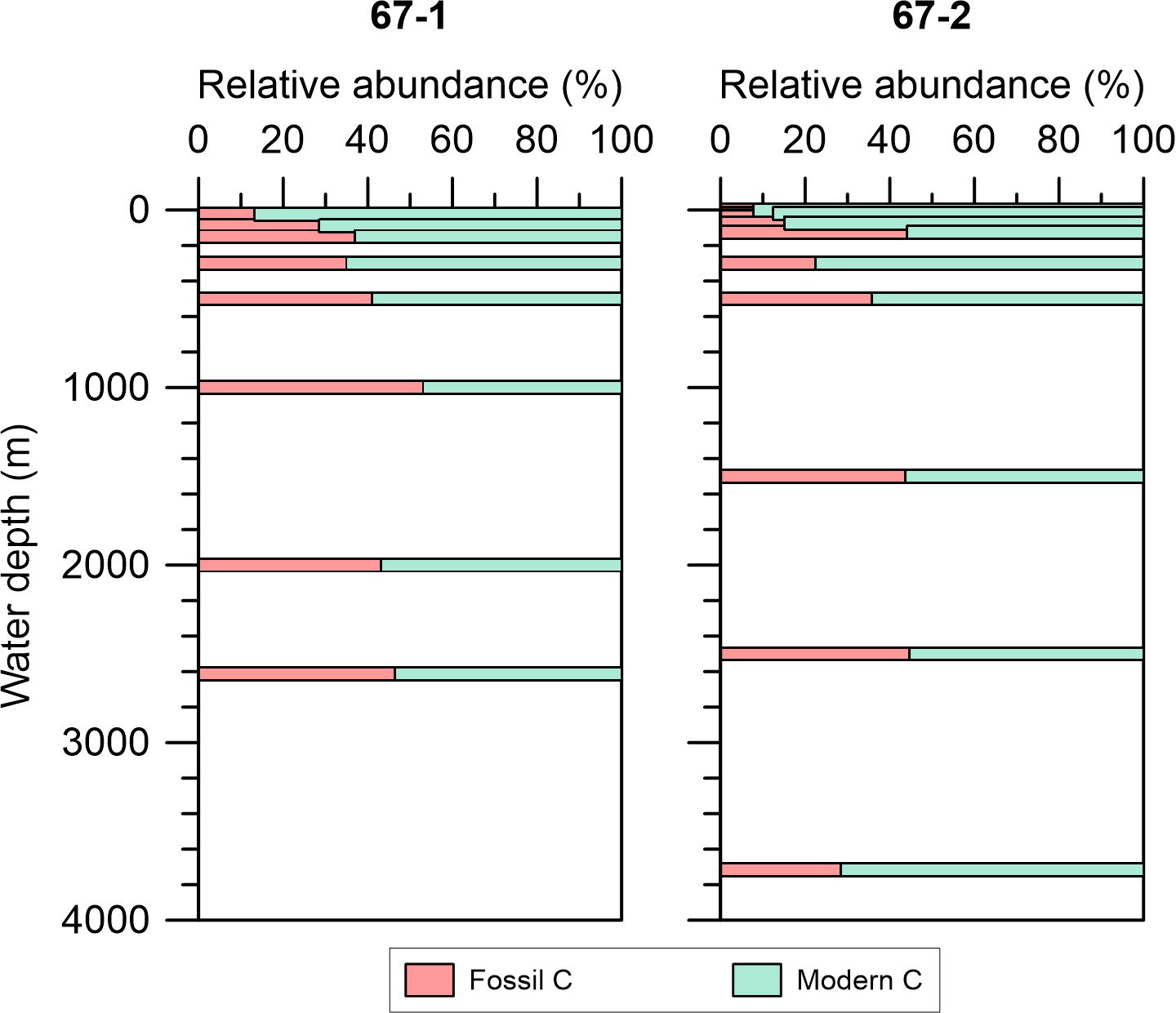

We investigated dual carbon isotopes within the vertical water column at sites 67-1 and 67-2 of the western equatorial Indian Ocean to determine the source and age of particulate organic carbon (POC) and thus evaluated the contributions of modern and fossil (aged) POC. The concentration of POC ranged from 7 to 47.3 μgC L−1, δ13CPOC values ranged from –31.8 to –24.4‰, and Δ14CPOC values ranged from –548 to –111‰. Higher values of δ13CPOC and Δ14CPOC near the surface indicated an influence of autochthonous POC, whereas decreasing trends toward the bottom suggested a contribution of aged OC sources to the total POC pool. The contribution of fossil POC was lower near the surface, accounting for only 12% and 6% of the total POC at sites 67-1 and 67-2, respectively; however, in the deeper layers below 1,000 m, the contribution of fossil POC increased to 52% and 44% of the total POC at the two sites. Mechanisms for the increased contributions of fossil OC within deeper POC include the inflow of aged OC from sediments resuspended near slopes, the adsorption of old dissolved organic carbon in deep water masses, and the impact of aged OC that may originate from hydrothermal sources. This study highlights the importance of aged OC in the carbon cycle of the equatorial Indian Ocean.

1 Introduction

Understanding the ocean’s capacity to absorb and sequester CO2 is crucial for evaluating the impacts of human-driven increases in atmospheric CO2 and is closely linked to the important role of organic carbon (OC) in the marine environment as a key component of the global carbon reservoir (Sabine et al., 2004; Devries, 2022). Atmospheric carbon is fixed by phytoplankton in the surface ocean, with only a small fraction being transported to deep waters and then buried in sediments (Volk and Hoffert, 1985; Honjo et al., 2008). This biological pump drives a variety of oceanic biogeochemical processes, and within this process, marine suspended particulate organic carbon (POC) represents a crucial component of the carbon pool (Volk and Hoffert, 1985; Devries, 2022). It serves as a key link between primary production, carbon export, and subsequent sequestration in the deep ocean. However, interestingly, the majority of the marine POC exported from the surface ocean to the deep ocean shows an older radiocarbon age (low Δ14C value) than that expected when considering freshly produced POC as the sole source (Druffel et al., 1992; Druffel et al., 1998; Hwang et al., 2010). The stable carbon isotope ratio (δ13C) has been used to trace the source of POC, and the radiocarbon isotope provides additional information about the age and reactivity of POC in the marine environment (Druffel et al., 1998; Marwick et al., 2015; Kang et al., 2020; Verwega et al., 2021). Dual carbon isotopes (stable and radiocarbon) are effective tools for investigating the biogeochemical processes of marine POC, providing insights into both its source and reactivity.

Various physical and biogeochemical processes that can affect the global carbon cycle are occurring in the Indian Ocean. The tropical Indian Ocean is influenced by various water masses, including tropical surface waters, Arabian Sea highly saline waters, Bay of Bengal waters, and Indonesian throughflow; and is bounded by the Asian landmass to the north and the African landmass to the west (Talley et al., 2011; Emery, 2015; Kim et al., 2021), which affects its current patterns, nutrient redistribution, productivity, and biogeochemical properties (Sardessai et al., 2010; George et al., 2013). The equatorial Indian Ocean is influenced by the Wyrtki jet, a zonal current system characterized by a narrow, fast-flowing eastward current at the surface, which makes the equatorial Indian Ocean less productive than the equatorial Pacific or Atlantic (Wyrtki, 1973; George et al., 2013). The tropical Indian Ocean also includes the Seychelles Chagos Thermocline Ridge (SCTR), an area between 10° S and 5° S characterized by open ocean upwelling that brings nutrient-rich waters to the surface, resulting in high biological productivity (Hermes and Reason, 2008; Dilmahamod et al., 2016; Kang et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2022). However, only a limited number of investigations have utilized carbon isotopes for carbon cycle studies in the Indian Ocean. Most of the stable carbon isotope composition measurements were conducted in the southern part of the Indian Ocean during the 1990s (Francois et al., 1993; Bentaleb et al., 1998; Riaux-Gobin et al., 2006). Subsequently, during the 2010s, research focusing on the tropical Indian Ocean (Soares et al., 2015; Subha Anand et al., 2018) and the eastern Indian Ocean (Raes et al., 2022) was reported. Nevertheless, the Indian Ocean remains understudied in comparison to other oceans, such as the Pacific and Atlantic (Close and Henderson, 2020; Verwega et al., 2021). Although several studies have been conducted on surface POC, our understanding of deep water POC dynamics remains largely underexplored, particularly in the Indian Ocean. Additionally, a noteworthy gap exists in the investigation of the sources and age characterization of POC within the context of open ocean conditions in the Indian Ocean. In this study, we investigated the vertical variability of both concentrations and stable and radiocarbon isotopes of POC in the western equatorial Indian Ocean. Our main objectives were to report the dual carbon isotope composition in the western equatorial Indian Ocean for the first time, to determine the sources and age of POC, and thus evaluate the contributions of modern and aged OC.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sampling and measurement of environmental properties

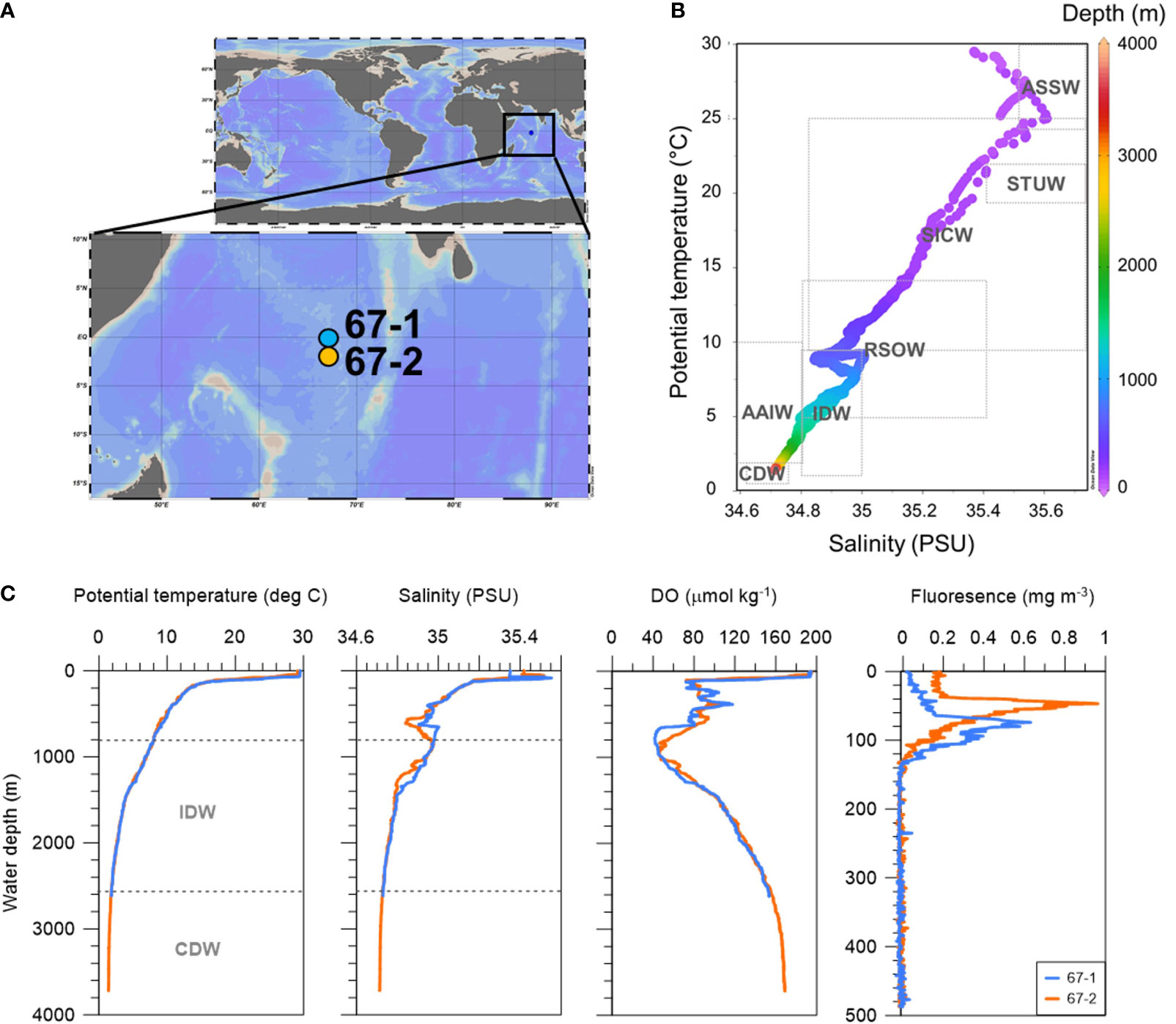

The KIOS22 cruise (23 Jun to 14 Jul, 2022, R/V ISABU) was part of the Korean contribution to the Second International Indian Ocean Expedition (2015–2025) in the southwestern Indian Ocean along the 65° E and 67° E meridions from 7° S to 1° S. Vertical POC samples were collected during the 67° E transect from stations at 1° S (station 67–1; 67.0002°E, –1.0005°S; n=13) and 2° S (station 67–2; 67.0000°E, –1.9992°S; n=13), where it was expected to have the characteristics of an open ocean with low productivity and little influence from SCTR upwelling. (Figure 1A). The vertical environmental parameters were measured using a conductivity–temperature–depth (CTD) profiler (SBE 911plus; Sea-Bird Electronics, USA) mounted on a carousel water sampler. Depth, temperature, conductivity, dissolved oxygen (DO), and fluorescence were measured during the cast. DO concentration measured by SBE 43 calibrated onboard using Winkler titration, with a measurement precision below 1 μmol kg–1. Water column samples were collected at each sampling depth using a Niskin rosette sampler. Duplicate water samples (5 L) were filtered through pre-combusted 25-mm GF/F filters (Whatman, 0.7 μm) for POC concentration and stable and radiocarbon isotope analysis, respectively. All samples were kept in a freezer until analysis.

Figure 1 (A) A map showing the study area and sampling sites in the Western Indian Ocean. (B) The T-S diagram shows the water masses distribution in the study area: Arabian Sea Surface Water (ASSW), South Indian Subtropical Underwater (STUW), South Indian Central Water (SICW), Red Sea Overflow Water (RSOW), Indian Deep Water (IDW), Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW) and Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW). (C) Vertical profiles of the environmental factors measured in the sampling sites.

2.2 Geochemical analysis

The filter samples for POC concentration and stable carbon isotope analysis were freeze-dried and acid-fumed for decalcification. POC concentrations and stable carbon isotope values were measured using an EA-IRMS system (MAT 253-plus connected with Flash IRMS elemental analyzer, Thermo Fisher, Germany). Stable carbon isotope ratios were expressed in delta notation (δ, ‰). The radiocarbon isotope of the filter samples was decalcified by acid dropping and then measured using a MICADAS AMS system at the Ocean University of China (OUC-CAMS) following their standard routines (Wang et al., 2023). The radiocarbon isotope ratio was expressed as delta notation (Δ, ‰) or Fm. Fm represents the fraction modern, defined by the deviation of the 14C/12C ratio of the sample from the modern (AD 1950) value.

2.3 Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using R. The Pearson correlation test (r) was performed to determine the relationship among the different datasets. Probabilities (p) were determined, and a p value of< 0.05 was considered significant.

2.4 Isotope mixing model

Fossil OC (Ffossil) introduction to the POC pool using a binary isotope mixing model based on the equation as follows:

where Xsample is the Δ14C value of the measured sample and Xmodern and Xfossil are the modern and fossil POC end-member values, respectively.

3 Results

3.1 Environmental parameters

At site 67-1, potential temperature ranged from 1.8 to 29.5°C, salinity ranged from 34.7 to 35.5 psu, and DO ranged from 44.3 to 186.6 μmol L–1. Site 67-2 displayed comparable trends, with potential temperature between 1.4 and 29.2°C, salinity from 34.7 to 35.5 psu, and DO from 48.9 to 187.3 μmol L–1. Both sites showed similar trends of high potential temperature and salinity at the surface and decreasing values to the bottom (Figure 1C). DO exhibited an oxygen minimum zone near 150 m and 1,000 m, respectively (Figure 1C). Fluorescence ranged from 0.0044 to 0.3352 mg m–3 at site 67-1 and from 0.0013 to 0.9413 mg m–3 at site 67-2, with maximum values observed near 75 m and 50 m from the surface due to the high primary productivity at both sites and minimum values observed at the bottom (Figure 1C).

3.2 Geochemical parameters

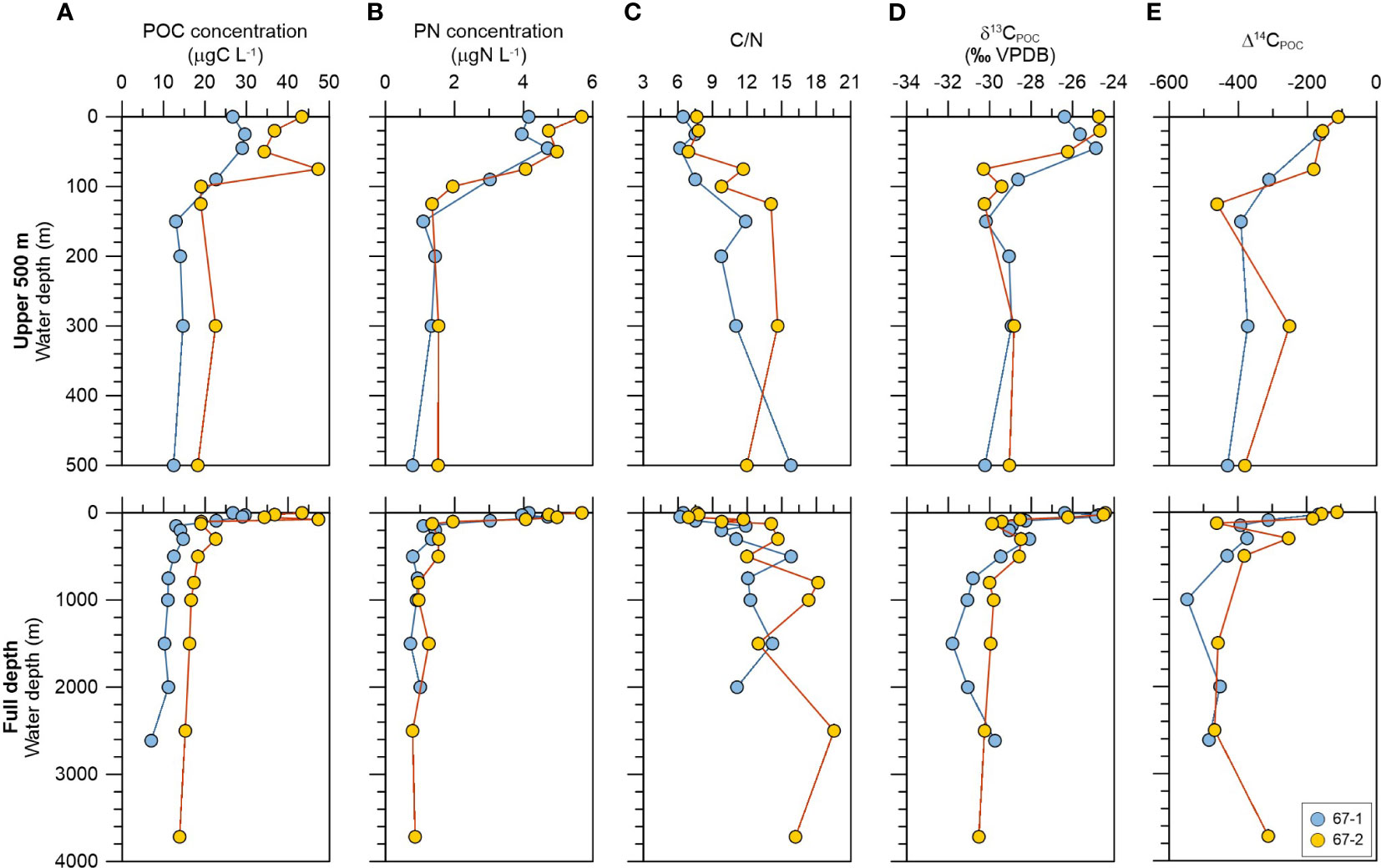

POC concentrations ranged from 7 to 26.7 μgC L−1 and 13.6 to 47.3 μgC L−1 at 67-1 and 67-2, and particulate nitrogen (PN) concentrations ranged from 0.8 to 4.7 μgN L−1 and 0.8 to 5.7 μgN L−1, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). Concentrations of POC and PN were generally higher in the upper water column (~100 m) than at deeper depths, and both POC and PN values exhibited a rapid decreasing trend down to 100 m depth and then decreased slightly toward the bottom (Figure 2). However, the concentration change was relatively rare and almost uniform. The C/N ratio showed an increasing trend with depth, with values of 6.8 to 15.8 at 67-1 and 6.9 to 19.5 at 67-2 (Figure 2). At both sites, the δ13CPOC values were highest at the surface, with values of –25.6 ± 1.2‰ and –24.5 ± 0.1‰ at 67-1 and 67-2 (Figure 2), respectively. The Δ14CPOC values were also high at the surface, with values of –164.5‰ at 67-1 and –133.6 ± 32‰ at 67-2 (Figure 2). Subsequently, a rapid decrease in both stable and radiocarbon isotopes was observed from the surface to approximately 100 m. However, beyond this depth, a slight increase followed by a gradual decrease was noted toward the bottom. Notably, the lowest δ13CPOC values of –30.9 ± 0.9 and –30.1 ± 0.3 and Δ14CPOC values of –494.7 ± 48.9 and –412.4 ± 87.6 in 67-1 and 67-2, respectively, were observed at depths below 1,000 m.

Figure 2 Vertical profiles of the (A) POC concentration (μgC L-1), (B) PN concentration (μgN L-1), (C) C/N ratio, (D) δ13CPOC (‰ VPDB) and (E) Δ14CPOC (‰) in the two sites.

4 Discussion

4.1 Vertical distribution of biophysical and geochemical parameters

The water mass properties at the study sites were identified by potential temperature, salinity, and DO concentration (cf. Kim et al., 2020a; Kim et al., 2021) (Figure 1B). Arabian Sea Surface Water (ASSW; T: 24.0–30.0°C, S: 35.5–36.8; Emery, 2015) and South Indian Subtropical Underwater (STUW; T: 8.2–21.1°C, S: 35.4–35.7, DO: > 150 μmol kg−1; O’Connor et al., 2005) with high salinity were at the upper part of the study sites. South Indian Central Water (SICW; T: 9–25°C, S: 34.6–35.8; Emery, 2001) was in the subsurface (200–300 m) of the study area, and Red Sea Overflow Water (RSOW; T: 5.0–14.0°C, S: 34.8–35.4; Talley et al., 2011) was detected below 300 m. Indian Deep Water (IDW; T: 1.6–9.37°C, S: 34.78–35.01; You, 2000; Sengupta et al., 2013), Antarctic Intermediate Water (AAIW; T: 2.0–10.0°C, S: 33.8–34.8; Emery, 2015), and Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW; T: 1.0–2.0°C, S: 34.62–34.73; Emery, 2015) with lower temperature and salinity values existed in the deeper part of the water column below 1,000 m. The water masses defined in this study were consistent with those of previous research (e.g., Kim et al., 2020a; Kim et al., 2021).

In both 67-1and 67-2, the concentration of POC was high in the upper water column (suface to 100 m), with values of 27.0 ± 3.1 μgC L–1 and 40.5 ± 6.0 μgC L–1. The C/N ratio and δ13C values, indicative of OC sources within this depth were close to the range of typical C/N ratio and δ13C values of marine phytoplankton (6 to 10 and −24‰ to −16‰, respectively) (Peterson and Fry, 1987; Lamb et al., 2006). In upper water column, DO concentration was relatively high, and fluorescence was also elevated within this depth. This suggested the introduction of autochthonous POC into the upper water column by marine phytoplankton. Both high POC concentration and high fluorescence value in upper water column further supports this observation (Figure 1C). However, low R2 values between POC isotopes and fluorescence at most sites (Supplementary Figures 1C, D) suggested that factors other than primary production primarily influenced the vertical distribution of geochemical parameters. Since salinity distributions provide information about the transport and mixing of different water masses (Kim et al., 2020a; Kim et al., 2021), significant positive correlations between salinity the carbon isotopes at both sites (Supplementary Figures 1A, B) suggest that the vertical distribution of POC sources in the water column is likely controlled by hydrological distributions, such as the mixing of different water masses. Indeed, the slopes of the linear regressions were similar at both sites, implying that similar hydrological effects impact both sites (Supplementary Figures 1A, B). Accordingly, the vertical distribution of the carbon-related parameters in the study area is controlled primarily by the mixing of different water masses, but also by the input of autochthonous POC.

To the best of our knowledge, no Δ14CPOC profile has been reported for the water column of the tropical Indian Ocean. A previous study on the suspended POC pool demonstrated a vertical distribution of Δ14CPOC values ranging from 43 to 139‰ in the North Central Pacific and –92 to 162‰ in the Sargasso Sea in the Atlantic Ocean (Druffel et al., 1992), indicated that most of the POC in the water column was derived from recently produced POC by primary production in the surface ocean (McNichol and Aluwihare, 2007). On the other hand, recently reported Δ14CPOC results in an open ocean transect of Cape Blanc (Fm ranging from ~0.6 to 1.0) emphasized the potential presence of POC with low 14C values, which is indicative of sediment resuspension-derived input in the deeper water column (Druffel et al., 2022). Overall, the radiocarbon isotope values in the western equatorial Indian Ocean measured in our study were much lower than those measured in the Pacific and Atlantic Ocean. Since sinking POC contains more material from the surface than suspended POC (McNichol and Aluwihare, 2007), assuming that recently produced POC mainly sinks from the surface, the input of aged POC in our study is likely associated with the inflow of older OC originating from resuspended sediments near continental margins or slopes (Druffel and Williams, 1990; Hwang and Druffel, 2006; Kim et al., 2020b). The Mascarene Plateau is located in the southwestern part of the study area and consists of an arcuate series of wide, shallow banks with small islands (Mart, 1988; Sreejith et al., 2019). These features are bounded by steep scarps that commonly slope to depths exceeding 3,000 m (Mart, 1988). Moreover, the study site is located on the Central Indian mid-ocean ridge, which is steep and the site of many earthquakes (Mart, 1988; Iaffaldano et al., 2018). On these slopes, particles are transported from continental shelves to slopes as nepheloid layers, and earthquake-induced resuspended sediment also plays a role in sediment supply (McCave, 1986; Lorenzoni et al., 2009). On the upper continental slope, ranging from 500 to 1,000 m water depth, resuspended sediment from the shelf/slope break is prominent at shallower depths, and local sediment resuspension and lateral transport along the slope become significant in the 2,000–3,000 m range (Kim et al., 2020b). Accordingly, the decrease in Δ14CPOC values observed in the deep ocean in this study may be associated with the inflow of sediment introduced from the surrounding continental slope, along with the subsequent introduction of aged POC.

Another possibility is the absorption of old dissolved organic carbon (DOC). Older OC is incorporated into the POC through the sorption of aged DOC from depth (Druffel and Williams, 1990). It is worth to note that mixing of different water masses may control the vertical distribution of POC sources in this region, as discussed earlier. Bercovici et al. (2018) revealed radiocarbon isotope values of DOC spanning the South Indian Ocean (56°S to 29°S), with deep CDW Δ14CDOC values of –491 ± 13‰ and IDW Δ14CDOC values of −503 ± 8‰ (Bercovici et al., 2018). The water mass properties of the study sites identified by potential temperature, salinity, and DO concentration revealed that the CDW and IDW affect the deep water of the study site (Figure 1). Thus, absorption processes involving aged DOC in deeper water masses might offer a mechanism for diminishing Δ14C values in suspended POC within this region (Druffel and Williams, 1990). To elucidate the increase in aged POC resulting from aged DOC sorption in deeper water column from different water masses, further research on the variation in DOC/POC ratio and stable isotopes of DOC is needed.

4.2 Contribution of fossil POC to suspended particles

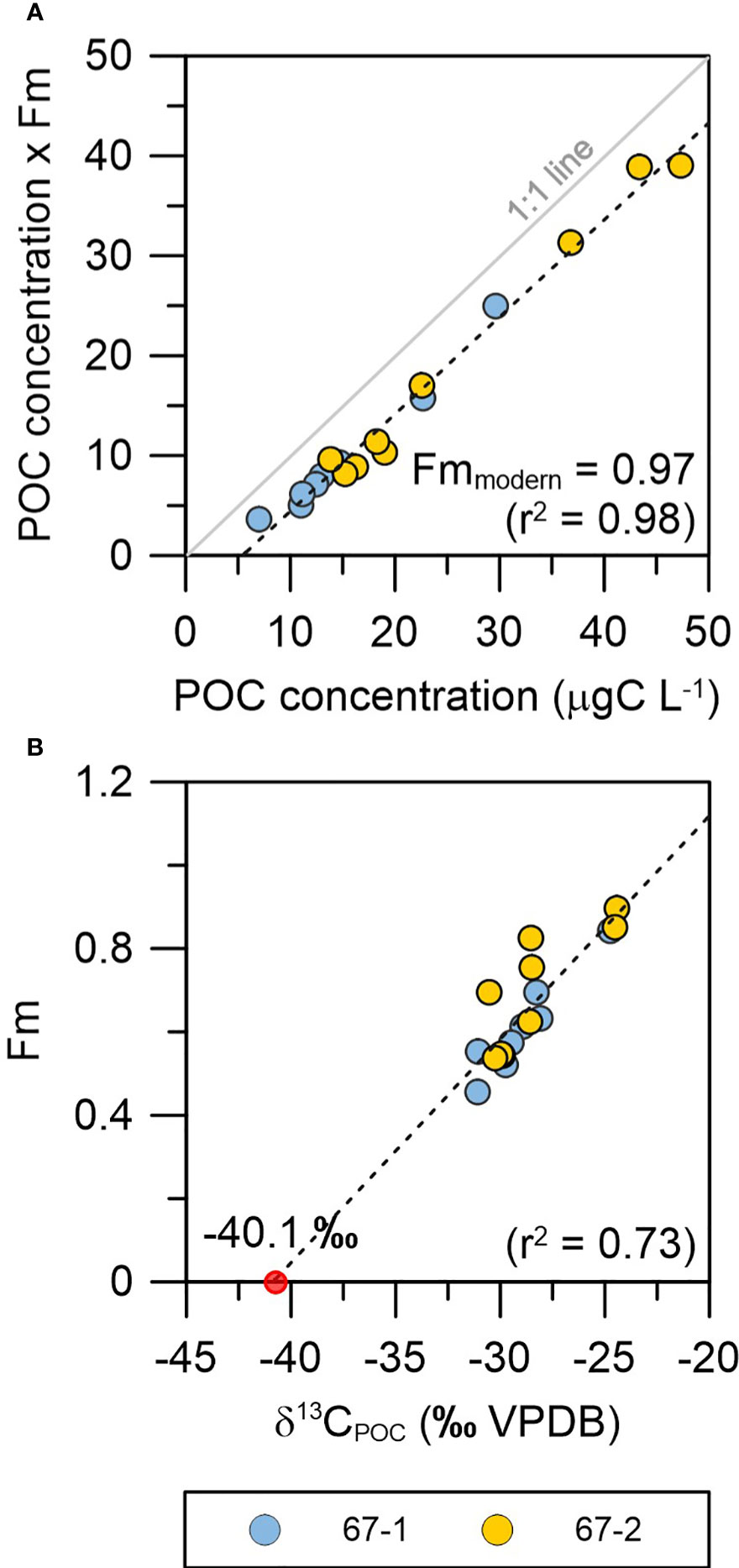

The POC concentrations were positively correlated with δ13CPOC and Δ14CPOC at both 67-1 and 67-2 (r = 0.77, p< 0.05 and r = 0.87, p< 0.05, respectively) (Supplementary Figure 2). As discussed above, high δ13CPOC values and higher concentration of POC in the upper layer of the water column indicate a greater input of in-situ produced POC. It also suggests that the higher POC concentrations in the study area are associated with greater inputs of in-situ produced POC with higher Δ14CPOC values. This correlation can also be explained by a mixing between two components, fossil POC (POCfossil) and recently produced POC (POCmodern), where POCfossil is radiocarbon free with an Fm value of 0 (Δ14C = –1000‰). Given the recent fixation of modern OC with a young radiocarbon age, it becomes possible to estimate the proportion of fossil OC (Ffossil) introduction to the POC pool using a simple mixing model using Equation 1. For this calculation, we assumed Δ14C end-member values of Δ14Cfossil = –1000‰ and Δ14Cmodern = +50‰ (cf. Wang et al., 2012; Yoon et al., 2016). This calculation indicates that the total suspended POC pool is a mixture of approximately 15–57% of fossil OC and 43–85% of modern OC. However, due to the variability in the age of POCmodern (Fm > 0), influenced by its residence time (Galy et al., 2008), the accuracy of a simple mixing model could be compromised. Hence, we also applied a binary mixing model to estimate the proportions of fossil (i.e., petrogenic) and modern (i.e., biospheric, modern biomass, and pre-aged carbon) OC. The end-members of POCmodern and POCfossil can be calculated using a binary mixing model, as follows Equations 2 and 3 (cf. Galy et al., 2008; Li et al., 2015):

where Fm, Fmmodern, and Fmfossil are the radiocarbon compositions of bulk POC, POCmodern, and POCfossil, and Ctotal, Cmodern, and Cfossil are the concentration of bulk POC, POCmodern, and POCfossil, respectively. Here, POCfossil is radiocarbon-dead (Fmfossil = 0). The POC collected along the depth profile represented in Figure 3 defines a linear trend between the concentrations of modern POC (Cmodern = POCtotal × Fm) and that of bulk POC. The POC contents from each water depth thus have an identical amount of POCfossil (Galy et al., 2008). The dashed lines show the best fit (Y = 0.9714 X – 5.2648, r2 = 0.98), with the slope revealing an Fmbio value of 0.9714 (Figure 3A). As a result, the fossil OC (i.e., POCfossil) corresponded to 8–53% of the total POC pool (Figure 4).

Figure 3 Scatter plots of (A) POC concentration × Fm and POC concentration, and (B) Fm and δ13CPOC (‰ VPDB). The dashed line shows the linear regression of the two sites.

The mean flux of lithogenic material accounts for 25 ± 20% and 20 ± 19% of the sinking particles globally and in the global abyssal plain, respectively, as reported in a compilation study of the global sediment trap (Kim et al., 2020b). In the global compilation study, values greater than 50% were observed for sinking particles intercepted within 2,000 m above the seafloor, particularly within ~1,000 m of the seafloor. Similarly, in our study, the highest proportion of fossil OC was found at depths between 1,000 and 2,000 m from the seafloor. Unfortunately, no sediment trap studies have been reported for the central Indian Ocean (Kim et al., 2020b), thus direct comparisons between fossil OC and lithogenic input were impossible; however, the proportion of fossil OC in the deep sea was higher than the global average. As discussed previously, older OC can be incorporated into deeper POC through various mechanisms. These mechanisms include the assimilation of older OC derived from sediments resuspended from near margins or slopes and adsorption of aged DOC (Druffel and Williams, 1990; Hwang and Druffel, 2006; McNichol and Aluwihare, 2007).

An additional source includes the production of POC from older OC sources in deeper layers (McNichol and Aluwihare, 2007; Feng et al., 2021). Fm and δ13CPOC demonstrated a best-fit linear relationship of Y = 0.0536 X + 2.192, along with a high correlation (r2 = 0.73) (Figure 3B). Although there is significant variability in the δ13CPOC values of POC samples from the water column (ranging from −31.8 to −24.4‰; see Figures 2D and 3B), the δ13C end-member value of the fossil carbon (δ13Cfossil) trend within the study sites converges toward approximately −40.1‰ (Figure 3B). Interestingly, the δ13C value of this component, which can be adopted as the end-member value of supplied Cfossil in the study area, exhibited the characteristically low δ13C value of deep-sourced carbon, including oil (Feng et al., 2021), methane (Petersen and Dubilier, 2009; Feng et al., 2021), and carbon fixed by a chemosynthetic pathway (Copley et al., 2016; Suh et al., 2022). Thus far, 13 vent fields, located from 41° S to 6° N and 49° E to 79° E, have been confirmed in the Indian mid-ocean ridges (van der Most et al., 2023). Notably, given that the study site is located on the Central Indian mid-oceanic ridge (Mart, 1988; van der Most et al., 2023), there might be an influence of aged OC from hydrothermal vents. However, our data are not sufficient to discern these potential sources of aged OC. Additional efforts using high-resolution POC isotopes are required to constrain the values associated with each of these potential sources more precisely, which will enable a better assessment of the diverse origins of aged OC in the western equatorial Indian Ocean.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we conducted an analysis of dual carbon isotopes of POC within the vertical water column of the western equatorial Indian Ocean for the first time. This analysis allowed us to determine the sources and ages of POC, enabling the evaluation of the contributions of modern and fossil OC. The δ13CPOC and Δ14CPOC values clearly demonstrated vertical variability of carbon sources, with higher values of both carbon isotopes near the surface, indicating autochthonous POC as the main source; and a decreasing trend toward the bottom, suggesting significant contributions of fossil OC to the total POC pool. The results suggest that a significant amount of fossil (aged) POC existed in the deeper water column of the western equatorial Indian Ocean, much greater than those reported from the Pacific or Atlantic. Fossil (aged) OC can be incorporated into deeper POC through various mechanisms, including an influx of old OC derived from resuspended sediments near slopes, adsorption of old DOC, and an influence of aged OC of possible hydrothermal origin. Further high-resolution studies of dual carbon isotopes are needed to accurately assess the contribution of these potential sources.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SK: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. HZ: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. YD: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. MZ: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. YS: Investigation, Writing – review & editing. PS: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. TR: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. D-JK: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was part of the project titled ‘KIOS (Korea Indian Ocean Study): Korea–US Joint Observation Study of the Indian Ocean,’ supported by the Korea Institute of Marine Science & Technology Promotion (KIMST) funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, Korea (20220548, PM63990). This research is also supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42230412).

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive feedback. We thank the crew the R/V ISABU for their assistance during fieldwork, Zicheng Wang and Xiaoyan Ning of OUC-CAMS for radiocarbon analysis. We are also grateful to the Eunhye Cho and the NRF Korea, and Tian Xiaoyi and the CSTEC China for their assistance in carrying out the project amid the pandemic situation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2024.1336132/full#supplementary-material

References

Bentaleb I., Fontugne M., Descolas-Gros C., Girardin C., Mariotti A., Pierre C., et al. (1998). Carbon isotopic fractionation by plankton in the Southern Indian Ocean: Relationship between δ13C of particulate organic carbon and dissolved carbon dioxide. J. Mar. Syst. 17, 39–58. doi: 10.1016/S0924-7963(98)00028-1

Bercovici S. K., McNichol A. P., Xu L., Hansell D. A. (2018). Radiocarbon content of dissolved organic carbon in the south Indian ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 872–879. doi: 10.1002/2017GL076295

Close H. G., Henderson L. C. (2020). Open-ocean minima in δ13C values of particulate organic carbon in the lower euphotic zone. Front. Mar. Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.540165

Copley J. T., Marsh L., Glover A. G., Hühnerbach V., Nye V. E., Reid W. D. K., et al. (2016). Ecology and biogeography of megafauna and macrofauna at the first known deep-sea hydrothermal vents on the ultraslow-spreading Southwest Indian Ridge. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep39158

Devries T. (2022). The ocean carbon cycle. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 47, 317–341. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-120920-111307

Dilmahamod A. F., Hermes J. C., Reason C. J. C. (2016). Chlorophyll-a variability in the Seychelles-Chagos Thermocline Ridge: Analysis of a coupled biophysical model. J. Mar. Syst. 154, 220–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2015.10.011

Druffel E. R. M., Beaupré S. R., Grotheer H., Lewis C. B., McNichol A. P., Mollenhauer G., et al. (2022). Marine organic carbon and radiocarbon - present and future challenges. Radiocarbon 64, 705–721. doi: 10.1017/RDC.2021.105

Druffel E. R. M., Griffin S., Honjo S., Manganini S. J. (1998). Evidence of old carbon in the deep water column of the Panama Basin from natural radiocarbon measurements. Geophys. Res. Lett. 25, 1733–1736. doi: 10.1029/98GL01157

Druffel E. R. M., Williams P. M. (1990). Identification of a deep marine source of particulate organic carbon using bomb 14C. Nature 347, 172–174. doi: 10.1038/347172a0

Druffel E. R. M., Williams P. M., Bauer J. E., Ertel J. R. (1992). Cycling of dissolved and particulate organic matter in the open ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 97(C10), 15639–15659. doi: 10.1029/92jc01511

Emery W. J. (2001). Water types and water masses. Encycl. Ocean Sci., 3179–3187. doi: 10.1006/rwos.2001.0108

Emery W. J. (2015). “Oceanographic topics: water types and water masses,” in. Encyclopedia Atmospheric Sci. (Second Edition), 329–337. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-382225-3.00279-6

Feng D., Pohlman J. W., Peckmann J., Sun Y., Hu Y., Roberts H. H., et al. (2021). Contribution of deep-sourced carbon from hydrocarbon seeps to sedimentary organic carbon: Evidence from radiocarbon and stable isotope geochemistry. Chem. Geol. 585, 120572. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2021.120572

Francois R., Altabet M. A., Goericke R., McCorkle D. C., Brunet C., Poisson A. (1993). Changes in the δ13C of surface water particulate organic matter across the subtropical convergence in the SW Indian Ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 7, 627–644. doi: 10.1029/93GB01277

Galy V., Beyssac O., France-Lanord C., Eglinton T. (2008). Recycling of graphite during Himalayan erosion: A geological stabilization of carbon in the crust. Sci. (80-. ). 322, 943–945. doi: 10.1126/science.1161408

George J. V., Nuncio M., Chacko R., Anilkumar N., Noronha S. B., Patil S. M., et al. (2013). Role of physical processes in chlorophyll distribution in the western tropical Indian Ocean. J. Mar. Syst. 113–114, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2012.12.001

Hermes J. C., Reason C. J. C. (2008). Annual cycle of the South Indian Ocean (Seychelles-Chagos) thermocline ridge in a regional ocean model. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 113, 1–10. doi: 10.1029/2007JC004363

Honjo S., Manganini S. J., Krishfield R. A., Francois R. (2008). Particulate organic carbon fluxes to the ocean interior and factors controlling the biological pump: A synthesis of global sediment trap programs since 1983. Prog. Oceanogr. 76, 217–285. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2007.11.003

Hwang J., Druffel E. R. M. (2006). Carbon isotope ratios of organic compound fractions in oceanic suspended particles. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33. doi: 10.1029/2006GL027928

Hwang J., Druffel E. R. M., Eglinton T. I. (2010). Widespread influence of resuspended sediments on oceanic particulate organic carbon: Insights from radiocarbon and aluminum contents in sinking particles. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 24, 1–10. doi: 10.1029/2010GB003802

Iaffaldano G., Davies D. R., Demets C. (2018). Indian Ocean floor deformation induced by the Reunion plume rather than the Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Geosci. 11, 362–366. doi: 10.1038/s41561-018-0110-z

Kang M., Kang J. H., Kim M., Nam S. H., Choi Y., Kang D. J. (2021). Sound scattering layers within and beyond the Seychelles-chagos thermocline ridge in the southwest Indian ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.769414

Kang S., Kim J. H., Hwang J. H., Bong Y. S., Ryu J. S., Shin K. H. (2020). Seasonal contrast of particulate organic carbon (POC) characteristics in the Geum and Seomjin estuary systems (South Korea) revealed by carbon isotope (δ13C and Δ14C) analyses. Water Res. 187, 116442. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116442

Kim J., Kim Y., Kang H. W., Kim S. H., Rho T. K., Kang D. J. (2020a). Tracing water mass fractions in the deep western Indian Ocean using fluorescent dissolved organic matter. Mar. Chem. 218, 103720. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2019.103720

Kim M., Hwang J., Eglinton T. I., Druffel E. R. M. (2020b). Lateral particle supply as a key vector in the oceanic carbon cycle. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 34, 1–14. doi: 10.1029/2020GB006544

Kim M., Kang J. H., Rho T. K., Kang H. W., Kang D. J., Park J. H., et al. (2022). Mesozooplankton community variability in the Seychelles–Chagos Thermocline Ridge in the western Indian Ocean. J. Mar. Syst. 225, 103649. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2021.103649

Kim Y., Rho T. K., Kang D. J. (2021). Oxygen isotope composition of seawater and salinity in the western Indian Ocean: Implications for water mass mixing. Mar. Chem. 237, 104035. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2021.104035

Lamb A. L., Wilson G. P., Leng M. J. (2006). A review of coastal palaeoclimate and relative sea-level reconstructions using δ13C and C/N ratios in organic material. Earth-Science Rev. 75, 29–57. doi: 10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.10.003

Lee E., Kim C., Na H. (2022). Suppressed upwelling events in the Seychelles–chagos thermocline ridge of the southwestern tropical Indian ocean. Ocean Sci. J. 57, 305–313. doi: 10.1007/s12601-022-00075-x

Li G., Wang X. T., Yang Z., Mao C., West A. J., Ji J. (2015). Dam-triggered organic carbon sequestration makes the Changjing (Yangtze) river basin (China) a significant carbon sink. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 120, 39–53. doi: 10.1002/2014JG002646.Received

Lorenzoni L., Thunell R. C., Benitez-Nelson C. R., Hollander D., Martinez N., Tappa E., et al. (2009). The importance of subsurface nepheloid layers in transport and delivery of sediments to the eastern Cariaco Basin, Venezuela. Deep. Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 56, 2249–2262. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2009.08.001

Mart Y. (1988). The tectonic setting of the Seychelles, Mascarene and Amirante plateaus in the western equatorial Indian Ocean. Mar. Geol. 79, 261–274. doi: 10.1016/0025-3227(88)90042-4

Marwick T. R., Tamooh F., Teodoru C. R., Borges A. V., Darchambeau F., Boillon S. (2015). The age of river-transported carbon: A global perspective. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 29, 122–137. doi: 10.1002/2014GB004911.Received

McCave I. N. (1986). Local and global aspects of the bottom nepheloid layers in the world ocean. J. Sea Res. 20, 167–181. doi: 10.1016/0077-7579(86)90040-2

McNichol A. P., Aluwihare L. I. (2007). The power of radiocarbon in biogeochemical studies of the marine carbon cycle: Insights from studies of dissolved and particulate organic carbon (DOC and POC). Chem. Rev. 107, 443–466. doi: 10.1021/cr050374g

O’Connor B. M., Fine R. A., Olson D. B. (2005). A global comparison of subtropical underwater formation rates. Deep. Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 52(9), 1569–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2005.01.011

Petersen J. M., Dubilier N. (2009). Methanotrophic symbioses in marine invertebrates. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 1, 319–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00081.x

Peterson B. J., Fry B. (1987). Stable isotopes in ecosystem studies. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 18, 293–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.001453

Raes E. J., Hörstmann C., Landry M. R., Beckley L. E., Marin M., Thompson P., et al. (2022). Dynamic change in an ocean desert: Microbial diversity and trophic transfer along the 110 °E meridional in the Indian Ocean. Deep. Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 201, 105097. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2022.105097

Riaux-Gobin C., Fontugne M., Jensen K. G., Bentaleb I., Cauwet G., Chrétiennot-Dinet M. J., et al. (2006). Surficial deep-sea sediments across the polar frontal system (Southern Ocean, Indian sector): Particulate carbon content and microphyte signatures. Mar. Geol. 230, 147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.margeo.2006.04.005

Sabine C. L., Feely R. A., Gruber N., Key R. M., Lee K., Bullister J. L., et al. (2004). The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2. Rios Source Sci. New Ser. 305, 367–371. doi: 10.1126/science.1097403

Sardessai S., Shetye S., Maya M. V., Mangala K. R., Prasanna Kumar S. (2010). Nutrient characteristics of the water masses and their seasonal variability in the eastern equatorial Indian Ocean. Mar. Environ. Res. 70, 272–282. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2010.05.009

Sengupta S., Parekh A., Chakraborty S., Ravi Kumar K., Bose T. (2013). Vertical variation of oxygen isotope in bay of Bengal and its relationships with water masses. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 118, 6411–6424. doi: 10.1002/2013JC008973

Soares M. A., Bhaskar P. V., Naik R. K., Dessai D., George J., Tiwari M., et al. (2015). Latitudinal δ13C and δ15N variations in particulate organic matter (POM) in surface waters from the Indian ocean sector of Southern Ocean and the Tropical Indian Ocean in 2012. Deep. Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 118, 186–196. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2015.06.009

Sreejith K. M., Unnikrishnan P., Radhakrishna M. (2019). Isostasy and crustal structure of the Chagos–Laccadive Ridge, Western Indian Ocean: Geodynamic implications. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 128, 1–13. doi: 10.1007/s12040-019-1161-2

Subha Anand S., Rengarajan R., Sarma V. V. S. S. (2018). 234Th-based carbon export flux along the Indian GEOTRACES GI02 section in the arabian sea and the Indian ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 32, 417–436. doi: 10.1002/2017GB005847

Suh Y. J., Kim M. S., Kim S. J., Kim D., Ju S. J. (2022). Carbon sources and trophic interactions of vent fauna in the Onnuri Vent Field, Indian Ocean, inferred from stable isotopes. Deep. Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 182, 103683. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2021.103683

Talley L. D., Pickard G. L., Emery W. J., Swift J. H. (2011). “Chapter S11 - Indian ocean: supplementary materials,” in Descriptive physical oceanography (Sixth edition), 1–14. Elsevier, Boston

van der Most N., Qian P. Y., Gao Y., Gollner S. (2023). Active hydrothermal vent ecosystems in the Indian Ocean are in need of protection. Front. Mar. Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.1067912

Verwega M. T., Somes C. J., Schartau M., Tuerena R. E., Lorrain A., Oschlies A., et al. (2021). Description of a global marine particulate organic carbon-13 isotope data set. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4861–4880. doi: 10.5194/essd-13-4861-2021

Volk T., Hoffert M. I. (1985). “Ocean carbon pumps: analysis of relative strengths and efficiencies in ocean-driven atmospheric CO2 changes,” in The carbon cycle and atmospheric CO2: natural variations archean to present. Eds. Sundquist E. T., Broecker W. S. (Washington, DC: Americal geophysical union), 99–110. doi: 10.1029/GM032

Wang X., Ma H., Li R., Song Z., Wu J. (2012). Seasonal fluxes and source variation of organic carbon transported by two major Chinese Rivers: The Yellow River and Changjiang (Yangtze) River. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 26, 1–10. doi: 10.1029/2011GB004130

Wang Z., Zhang H., Ning X., Xu X., Zhao M. (2023). Performance report of the MICADAS at the Ocean University of China. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms 543, 165087. doi: 10.1016/j.nimb.2023.165087

Wyrtki K. (1973). An equatorial jet in the Indian ocean. Science 181, 262–264. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4096.262

Yoon S. H., Kim J. H., Yi H., Yamamoto M., Gal J. K., Kang S., et al. (2016). Source, composition and reactivity of sedimentary organic carbon in the river-dominated marginal seas: A study of the eastern Yellow Sea (the northwestern Pacific). Cont. Shelf Res. 125, 114–126. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2016.07.010

Keywords: Indian Ocean, particulate organic carbon, stable carbon isotope, radiocarbon isotope, fossil organic carbon

Citation: Kang S, Zhang H, Ding Y, Zhao M, Son YB, Son P, Rho TK and Kang D-J (2024) Contribution of aged organic carbon to suspended particulate organic carbon in the western equatorial Indian Ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 11:1336132. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1336132

Received: 10 November 2023; Accepted: 10 January 2024;

Published: 31 January 2024.

Edited by:

Liyang Yang, Fuzhou University, ChinaReviewed by:

Min-Seob Kim, National Institute of Environmental Research (NIER), Republic of KoreaDewang Li, Ministry of Natural Resources, China

Copyright © 2024 Kang, Zhang, Ding, Zhao, Son, Son, Rho and Kang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dong-Jin Kang, ZGpvY2VhbkBraW9zdC5hYy5rcg==

Sujin Kang1

Sujin Kang1 Hailong Zhang

Hailong Zhang Yang Ding

Yang Ding Meixun Zhao

Meixun Zhao Yeong Baek Son

Yeong Baek Son Tae Keun Rho

Tae Keun Rho Dong-Jin Kang

Dong-Jin Kang