95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

POLICY AND PRACTICE REVIEWS article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 08 May 2024

Sec. Marine Affairs and Policy

Volume 11 - 2024 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2024.1306386

This article is part of the Research Topic Social Science Perspectives on Marine Biodiversity Governance View all 6 articles

Solomon Sebuliba1,2,3*

Solomon Sebuliba1,2,3*This article examines the multifaceted dimensions of landlockedness within the realm of international discourse, with a particular focus on its implications for managing global commons. Drawing from socio-legal literature and auto-ethnographic experiences during the recent intergovernmental negotiations for the BBNJ agreement under the 1982 Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) as a case study, the paper prompts essential inquiries into the true essence of being landlocked in the face of global environmental challenges. Beyond traditional geographical definitions, the paper reveals the dynamic nature of landlockedness and underscores the intricate interplay of social, economic, cultural, geographical, and political factors in determining who has access to ocean space and resources and who does not. It emphasizes that landlockedness is not a static legal or physical characteristic but an ongoing process shaped by historical and political constructs. Expanding beyond the national level, the article illustrates how individuals, whether coastal or inland, experience isolation from the ocean, influencing their interactions with, perceptions of, and regulatory proposals for the ocean. This approach illuminates existing paradigms in the access, use, and management of space and resources. In conclusion, the article advocates for more inclusive and adaptable approaches in international policy debates. It calls for a departure from rigid classifications, urging for upholding collective action, recognising the intricate connections between geography, politics, law, and the environment.

The implications of being landlocked in international debate and discourses remain relatively underexplored. Landlocked states (LLSs) are defined by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) as states without a sea coast (UNGA, 1982). Coastal proximity not only determines a state’s rights in ocean matters but also influences its identity in international relations (D’Arcy, 2008; Vaha, 2023). The seemingly simple geographic descriptor of landlockedness carries profound legal, economic, and geopolitical implications. LLSs classified as “geographically disadvantaged states” draw special attention due to lack of physical proximity to the ocean and peripherally the ensuing challenges (Uprety, 2006). Coastal states then assume an “advantaged” position, wielding influence along the coast.

However, the recent intergovernmental negotiations for the adoption of the BBNJ agreement under UNCLOS, also known as the High Seas Treaty, highlighted the multifaceted nature of the landlocked predicament even when addressing Areas Beyond National Jurisdictions (ABNJ) and marine biodiversity conservation. Representatives of developing landlocked states expressed grievances about the neglect of the common heritage principle (CHP) (Vadrot et al., 2022), prompting essential questions about what it truly means to be landlocked and the far-reaching implications in international discourse and the management of global commons.

In international discussions, the tendency to categorize countries with simplistic labels such as “coastal” or “landlocked” oversimplifies the intricate ways in which nations access and utilize space and resources (Steinberg, 1999, 2001). These labels fail to capture the multifaceted influences of legal, physical, and cultural factors that shape the evolution of nations over time (Machiavelli et al., 1532/2020; Lenin, 1917/2016; Ball, 2019; Rousseau, 2019).

Geopolitical classifications often fall into the trap of presenting dynamic processes as overly straightforward, leading to the creation of rigid categories (Dahlberg, 2015) and adherence to static and closed modes of thinking (Bedolla, 2005; Steinberg and Peters, 2015). The borders depicted on maps, represented as one-dimensional lines, convey a misleading sense of finality and permanence (Murphy, 2010; Diener and Hagen, 2012; Wimmer, 2013). Seemingly fixed, these borders create divisions in the human mind (Mannov, 2013; Feinberg, 2014; McAllister, 2020), linking value, interests, and influence predominantly to unchanging spatial characteristics (Mathews, 1997; Faye et al., 2004; Elden, 2013a). This perspective obscures the true reasons behind the access and use of space and disregards the dynamic nature of borders over time (Peters, 2014; Sammler, 2020a).

Challenging these fixed and immutable ideas are the oceans, which introduce depth and movement to the conventional geopolitical system of states with roots in the Westphalian system of the 1600s (Elden, 2013a), defying notions built on rigidity (Steinberg and Peters, 2015). Oceans pose challenges in managing migrating organisms (Maxwell et al., 2015; Pinsky et al., 2018; Stahl et al., 2020), interconnected ecosystems (Mahler and Pessar, 2001; Sardar, 2010), and geopolitically charged spaces like ABNJ (Mazza, 2010), requiring adaptive considerations. Legal and practical contradictions arise in addressing “borderless risks” like biodiversity loss and climate change (Goldin and Mariathasan, 2014). Oceans also reveal a disconnect between socio-political borders and the dynamic ecological criteria necessary for effective management (Dallimer and Strange, 2015; Harvey et al., 2017). Island and archipelagic communities face challenges such as ambulatory baselines and disappearing islands due to climate change eroding the physical, biological, and legal foundations of borders (Heidar, 2004, 2020; Mayer, 2020; Sammler, 2020a; Lee and Bautista, 2021). In ocean management, nomadic and indigenous groups often resist established systems (Refisch and Jenson, 2016; Levin, 2020; Nurmi, 2020; Wille et al., 2021), especially in ABNJ, where multiple stakeholders and jurisdictions overlap and the fixed classifications become problematic, necessitating a more flexible and adaptive approach.

Despite the tradition of maritime delineation dating back to ancient times and preceding the formation of many contemporary states (Johnston, 1988), the principles guiding maritime boundaries have consistently been rooted in how we think about land borders between countries. Peters (2020) notes that, “…modes of demarcating space do not ‘belong’ at sea but have been transported there from the land and landed logics … This landed ontology and territorial geo-philosophy is an underlying discourse of ocean governance so powerful it is rarely questioned” (Peters, 2020, p. 4). The formalization of modern maritime borders and zones occurred during the negotiations of UNCLOS I, II, and III, where the influence of rigid terrestrial logics in ocean governance emerged as measurement of linear lines and zones as frontiers (Johnston, 1988; Steinberg and Peters, 2015).

Determining the precise breadth, historical existence, development, and legal status of maritime zones had always been a contentious issue (Treaties, 1958; Noyes, 2015). UNCLOS negotiations managed to establish the Territorial Sea (TS), which extends 12 nautical miles from the coastal states’ baseline (Article 3). The legal rights and responsibilities related to this are outlined in Part II, Sections 1 and 3 of UNCLOS. Based on rights, additional zones like the Contiguous Zone (CZ), Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), and Continental Shelf (CS) were delineated. As summarized by Sammler (2020a), UNCLOS set up a jurisdictional structure where sovereignty decreases farther from the coastline (Sammler, 2020a, p. 71). Coastal states still have significant control in extended zones however, managing resources, the environment, and marine research in the EEZ (UNCLOS Articles 56-68). They also have exclusive rights, ipso facto-ab initio, over non-living and living resources in the continental shelf (McDorman, 2002).

Two crucial aspects deserve emphasis. Firstly, the intentional choice of the 200nm limit for the EEZ was to cover the majority of fish stocks and other resources (FAO, 2007; Schofield, 2018). Secondly, the interpretation of the extent of the continental shelf outlined in Article 76 of UNCLOS, potentially gives coastal states expanded rights over seabed resources farther offshore. As Weil (1989) states, “land dominates the sea and it dominates it by the intermediary of the coastal front” (Weil, 1989).

The High Seas and the Area, defined as legally “free” zones accessible to all states under UNCLOS, constitute ABNJ. Without any specific definition in UNCLOS, Article 86 describes the High Seas as the water column beyond territorial seas, EEZs, internal waters, and archipelagic waters (Oxman, 1989). The Area comprises the seabed, ocean floor, and subsoil beyond national jurisdiction (Article 1(i)), representing the common heritage of humanity (Article 136). Legal interpretation is crucial here due to technical and scientific terms used in defining the outer limits of the continental shelf. The distinction between the scientific and legal Continental Shelf (CS) is crucial (Heidar, 2004). Coastal states can employ various methods to establish CS limits (Article 76), incorporating technological advancements (Hughes Clarke et al., 1996). Further exploration of these methods is encouraged through works like “Legal and Scientific Aspects of Continental Shelf Limits” (Nordquist et al., 2004).

The result is that the true nature of ABNJ where LLS should have equal rights and influence independent of their coastal neighbors, cannot be clearly defined. Moreover, due to geographical proximity and economic prowess, some coastal states persist in asserting their dominance over ocean use and management, creeping their jurisdictions into ABNJ (Davis and Wagner, 2006). They wield control and influence over the maritime domain through baselines along the coast upon which other maritime zones are derived (Jayakumar et al., 2014). Moreover, even local coastal communities and small island populations who directly rely on marine resources and have a long-term interest in their sustainability (Newell and Ommer, 1999), are often overlooked by wealthier countries.

The UNCLOS negotiations introduced principles like the CHP (Noyes, 2015) to move beyond geographical binaries. Ignoring the CHP principle leads to fragmented policies (Dallimer and Strange: Hirsch, 2020), obstructs collective action (Vadrot et al., 2022) and eliminates any international or global contexts (Sentance and Betts, 2012; Liverman, 2016). This perpetuates a state-centric system that struggles to address complex global issues (Tapscott, 2014; Hughes and Vadrot, 2019) and exacerbates the challenges of disadvantaged groups within geographical blocs, whose interests depend on the collective will of the majority within the bloc and beyond (Vihma et al., 2011; Linnell, 2016).

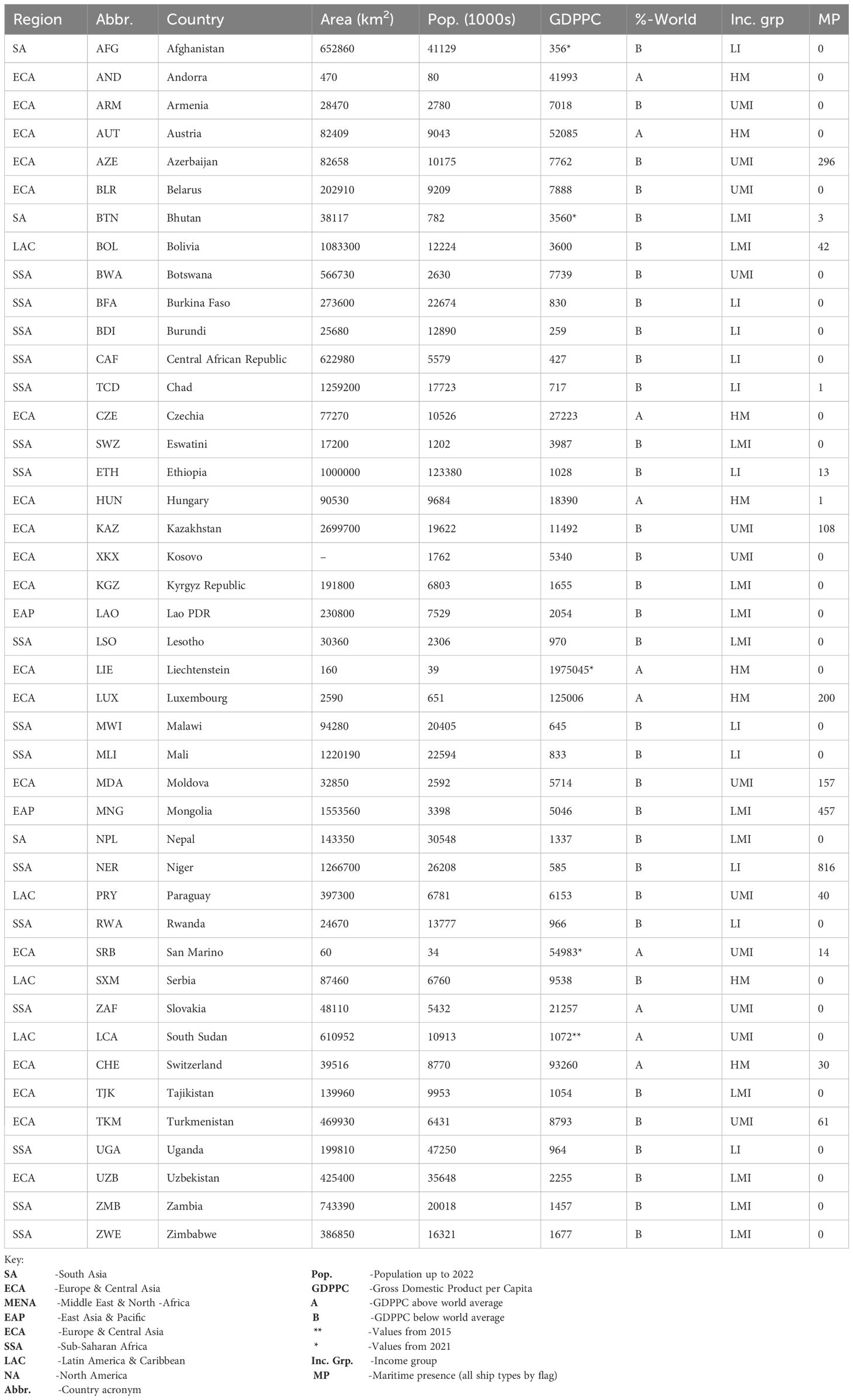

For instance, within the category of LLS, there is a lack of homogeneity on various issues (Table 1). High-income LLSs, especially in Central and Western Europe, have historically shown less interest in access and transit provisions than low-income LLSs. This is partly due to their access and transit interests being regulated in regional or bilateral agreements (Schimmelfennig et al., 2015), along with technological and economic investments that grant them an advantage in ocean negotiations (Lane and Pretes, 2020). These states tend to be more interested in the issue of exploitation of resources. Factors such as cooperation with neighboring states, administrative practices, and infrastructure, rather than geographical distance, critically define the status of states (Faye et al., 2004; Rodrik et al., 2004; Boulhol et al., 2008; Sharma, 2020). This nuanced perspective underscores the complex dimensions of landlockedness, revealing an interplay between geographical, social, economic, and historical factors in defining their interests in international discourse. Therefore, we need to think of landlockedness as not a straightforward (meta)physical or (meta)legal condition, but as a categorization that reproduces ideas about access. These dynamic perspectives are yet to be fully acknowledged and integrated into international policy debates (Peters et al., 2022).

Table 1 Comparison of Landlocked states by region, area, population, and income based on Gross domestic product per capita (GDPPC), and maritime presence based on registered number of all ship types by flag.

This article aims to highlight the nuanced dimensions of landlockedness in international discourse, particularly concerning the management of global commons. Discourses include ways in which ideas, concepts, and perspectives are formulated, debated, and or understood among various stakeholders and in different contexts e.g., diplomatic, political, and or social during negotiations (Potter, 2004). In international contexts, it also encompasses examining underlying assumptions, power dynamics, and the implications for instance in environmental governance (Brand and Vadrot, 2013; Hughes and Vadrot, 2023). Through discourse analysis, the article challenges prevailing notions of landlockedness as a fixed geographical condition, revealing other aspects that influence decision-making processes such as the legitimization of values under historical legal frameworks like UNCLOS. The analysis underscores the importance of challenging the idea of national territorial borders when tackling global oceanic environmental challenges (Agnew, 1994, 2008; Reid et al., 2010; Galaz et al., 2012). Adding to existing social literature (Mathews, 1997; Jones, 2009; Elden, 2013b; Dahlberg, 2015; Sammler, 2020a), it argues against viewing geographical borders as static entities, highlighting their dynamic nature and varying impacts in ocean management. Additionally, it questions the Euclidean legal definition within UNCLOS, proposing a nuanced understanding and a value-based approach (e.g., focusing on human rights), that could account for collective interests during international negotiations and the management of global commons.

In examining these nuances, the analysis goes beyond the traditional two-dimensional view of landlockedness that encompasses only geopolitical and institutional aspects, to uncover other implications at the individual level and the governance of global commons. This perspective underscores the complexity of regarding land-sea relations as fixed, exposing the seeming permanence of being landlocked as a category with multifaceted implications in ocean governance.

The concept of landlockedness is conventionally discussed in literature as a fixed geographical condition, and this perspective is upheld in legal thought and international discussions. It is crucial to re-evaluate and question how the perceived rigidity of land interacts with and is superimposed on the idealized stability of legal frameworks and vice versa (Kennedy, 2002). These perceived fixities influence notions of resource access and management.

To bridge this gap, the paper primarily draws from existing literature on landlockedness in the social sciences, considering both geographical and legal perspectives. It explores the historical evolution of landlockedness and its impact on the development of legal frameworks, with a primary focus on UNCLOS and its negotiations. The UNCLOS regime not only defines LLSs but also serves as a crucial reference point where the category emerged and operates in international discussions. The article then uses the recent BBNJ negotiations as a case study to demonstrate implications within contemporary international discourse. The BBNJ represents the most recent global ocean management regime and the first since the launch of the UN Ocean decade (UNESCO, 2021). It serves as a benchmark to assess progress in the international debate concerning geographical borders, with the potential to improve, overcome, or replicate ideologies built on fixed categories.

Multilateral fora offer invaluable insights into the complex mechanisms of international discourses and global environmental politics (Vadrot, 2020). The convergence of a diverse array of stakeholders, ranging from state representatives to non-governmental observers, academic scholars, local communities, and private sector actors, fosters the exploration of ongoing narratives, ideologies, and frameworks within the global discourse (Hughes and Vadrot, 2019, 2023). Active participation in these forums reveals intricate dynamics that surpass simplistic dichotomies such as north versus south (Vadrot, 2020), illuminating other concepts, inequalities, and power dynamics often overlooked in broad classifications or conventional theories (Hughes and Vadrot, 2023).

The author draws on auto-ethnographic experiences from the Intergovernmental Conferences (IGCs) on the BBNJ as a valuable source of qualitative data, providing an insider’s perspective. Participating as an observer in the fourth and fifth BBNJ IGCs and serving as a technical advisor to an LLSs delegation during the final IGC, the author gained first-hand data, observations, and insights. These roles uniquely positioned the author to comprehend the dynamics, discussions, and negotiations surrounding the treaty and land-sea borders. Acting as a technical advisor allowed for close engagement with state representatives, including those from geographic blocs, islands, coastal areas, and LLSs, providing insights into their specific concerns and challenges related to marine governance. The author’s auto-ethnographic experiences, coming from a landlocked country while working on marine issues in a coastal state, add a personal lens to the analysis, offering a unique perspective on the implications of landlockedness from both a landlocked and coastal state’s standpoint. To respect confidentiality and diplomatic reasons, specific details about the countries and the geographic bloc are omitted at the request of some crucial diplomats. This omission is made as an ethical consideration of the sensitive nature of international negotiations, ensuring a conducive environment for further constructive engagements.

During the negotiation process, interviews were conducted with various state representatives and observers, both onsite and offsite. However, this article focuses exclusively on perspectives from representatives of landlocked states. In the fourth IGC, participants were approached randomly for interviews, reflecting the need for adaptability and readiness in dynamic negotiation environments (Hughes and Vadrot, 2023). It became apparent that only a few observers were willing to participate in formal interviews and sign ethics consent forms, preferring brief discussions during session breaks. With most country representatives declining to sign consent forms, a shift to informal interviews and casual discussions, such as coffee talks outside negotiation sites, was necessary. During these interactions, respondents were made aware that the author was an observer and a researcher, recording insights for further analysis in a field notebook. Direct quotes were occasionally recorded, with some adjustments for clarity made during or after the interviews. This methodology was replicated in subsequent IGCs, with about 30 respondents interviewed.

Additionally, the author had access to memoirs and minutes from the landlocked state representatives, for which he served as a technical advisor. These documents provided insights into previous negotiation processes, both onsite and offsite. Drawing from these sources, the article presents a critical examination of the challenges faced by landlocked states, incorporating not only geopolitical factors but also individual experiences and perceived identities.

States become geographically landlocked influenced by events such as wars or disputes leading to secession and territorial loss adjacent to the sea. Examples include Ethiopia losing a coastline when Eritrea gained independence resulting in a protracted dispute (Iyob, 1995), South Sudan’s secession from Sudan in 2011 leaving the former without a coastline (Branch, 2013), and Bolivia’s loss of land and sea access to Chile following the War of the Pacific in 1904 (John, 2009). In other cases, imperial border policies imposed by European colonizers such as the Berlin Conference of 1884-85 for predominantly “present day” Africa resulted in inventing new borders and consequent landlockedness for states like Uganda (Yao, 2022).

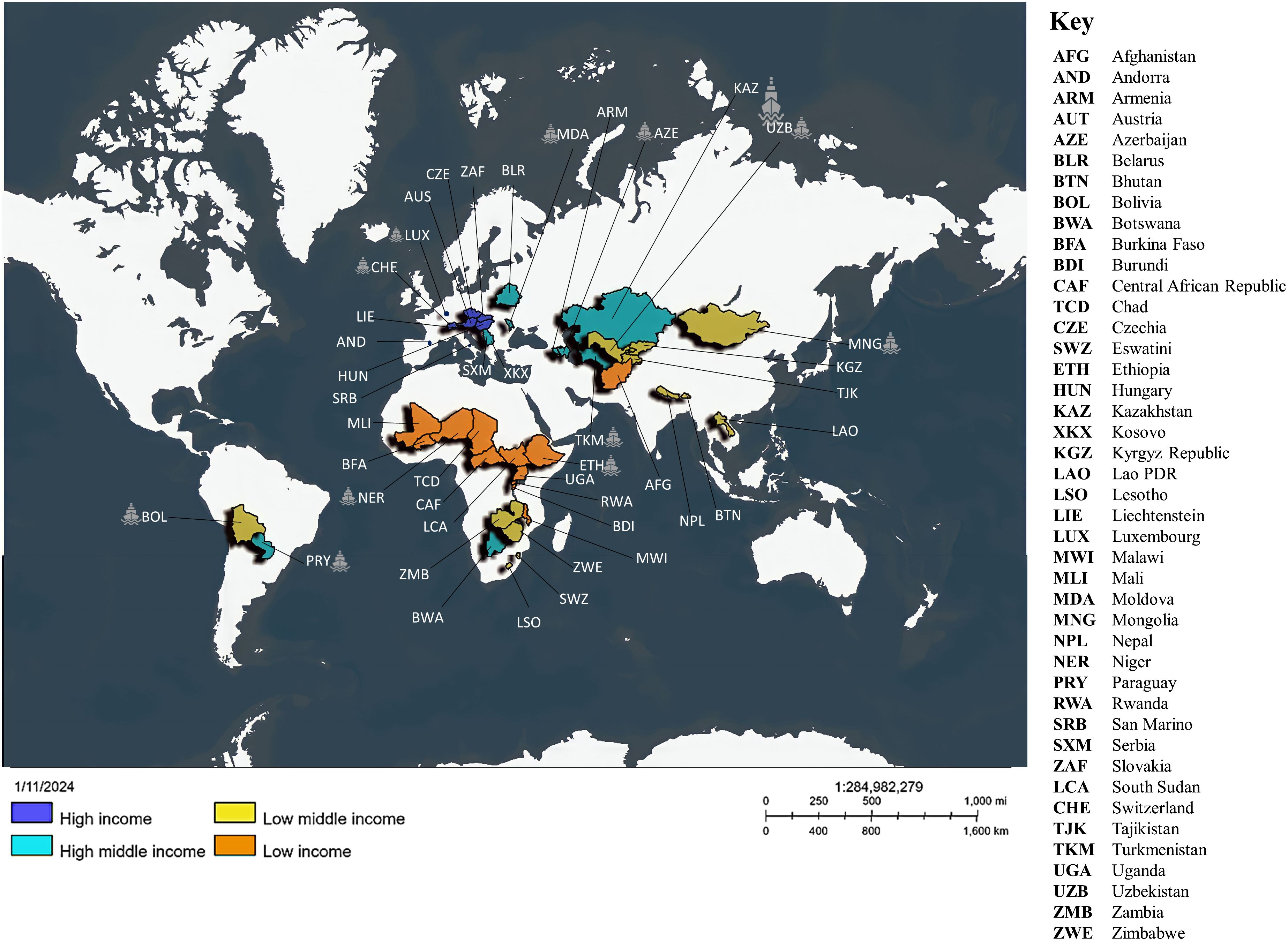

While some countries in the past have taken drastic measures, even resorting to bloodshed, to avoid being geopolitically landlocked (John, 2009), others rely on negotiations. Examples include the “Polish corridor” that Poland acquired from Germany to gain access to the Baltic Sea (Hartwell, 2023). Modern states depend on international negotiations and principles such as the CHP to overcome landlockedness or establish harmony between access dynamics and spatial elements (Vadrot et al., 2022). Several LLSs currently manage ocean-going commercial vessels under their own flags (e.g., Azerbaijan, Bolivia, Czech Republic, Ethiopia, Kazakhstan, Laos, Luxembourg, Moldova, Mongolia, Paraguay, Slovakia, Switzerland, and Turkmenistan (Tuerk, 2020; Figure 1), through access rights negotiated within the framework of UNCLOS (I, II, and III). Others, like Switzerland, leverage technological advancements, participation in global banking and monetary markets, trade agreements, and access to markets both within and beyond neighboring countries to overcome being landlocked (Lane and Pretes, 2020).

Figure 1 Landlocked states categorized by income group. States operating ships are identified with a ship symbol next to their acronym. The ship data source can be found at https://www.marinevesseltraffic.com. Refer to Table 1 for the corresponding acronyms and the respective number of ships.

In other words, becoming and being landlocked represent complex geopolitical situations involving historical, diplomatic, and strategic considerations for affected states to secure access to the sea, overcome challenges associated with geographical landlockedness, or face the full impact of being landlocked.

Being landlocked bears several consequences, which include bargaining with the coastal neighbor(s) to access goods and services across the latter’s territory (Faye et al., 2004). As an easement of access, the LLS is required to collaborate with or compensate the neighbors for necessity of trade or passage and or any damage caused in the process (Bangura, 2012). Such arrangements sometimes result in a “permanent legal servitude of passage,” where rights of innocent passage and transit are restricted and dependent on the coastal state’s will (Wilmore, 1986). This situation can also lead to a “Prisoner’s Dilemma,” where littoral states may choose to deny access to LLSs if cooperation is lacking or if the latter reduce their dependence on their coastal neighbors (Bangura, 2012).

This was the case for the Nepalese in the fall of 2015, and Afghans in 2011, who faced blockades and access restrictions, triggering fuel and humanitarian emergencies, as a result of strained relations with their coastal neighbors (Jones, 2007; Budhathoki and Gelband, 2016). The presence of “super-giant” states with significant overseas territories and control over ocean resources and trade, creates further barriers for disadvantaged states without similar influence (Cawley, 2015; Krause and Bruns, 2016).

In international discussions, this designation reinforces the dominance of ‘advantaged’ states in maritime affairs. For instance, prior to 1900, many LLSs could not operate vessels flying their flag because some coastal states had refused to recognize this right (Sohn et al., 2014). France, Britain, and Prussia, in particular, argued that LLSs lacked seaports and warships and couldn’t effectively control their merchant vessels (Churchill et al., 2022). Although UNCLOS provisions, especially those related to general rights of access, innocent passage, freedom of transit and navigation, and exploitation of marine resources (Articles 124-132), granted LLSs access to the sea, obtaining approval from coastal states remained a formidable challenge (Churchill et al., 2022). The same geographical considerations from the UNCLOS negotiations persist in international talks, limiting the participation of representatives from LLSs. The access provisions of UNCLOS become less practical for states without clear access to coastal ports or the right to access the territories between LLSs and the sea.

Moreover, the UNCLOS negotiations would predominantly focus on the use of the oceans by coastal states within their Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) and Continental Shelves (CS) (Roach, 2021). Provisions for other states like LLSs to exploit “surplus” resources in coastal states’ EEZs under UNCLOS Article 69 are complicated, relying on the economic and geographic circumstances of all states involved under Articles 61 and 62. Generally, the provisions of access were aimed to maintain peace among states but also served as a diplomatic ploy for disadvantaged LLSs, particularly those from the Global South, to feel included in ocean management (Wani, 1982; Kaye, 2006).

In contrast to prior international discussions on oceans, the BBNJ specifically centered on ABNJ, expected to offer a more balanced platform for all states, including low-income LLSs. Despite shared responsibility of ABNJ, low-income LLSs hold a unique position due to their developmental needs, understanding of other developing nations’ needs, and limited capacity to access economic benefits in these areas. This position allows them to present balanced views on ocean development while exercising caution regarding environmental impacts in ABNJ. Affluent counterparts, like Switzerland, have greater capacity to access these spaces and often adopt a critical stance, especially towards similarly affluent states seeking to extend influence in ABNJ based on geographical advantage. The BBNJ negotiations, however, encountered a “joint-decision trap” (Scharpf, 1988), where the pursuit of unanimous agreement or consensus was over-taken by individual national interests. Consequently, the distinctive voices envisioned for LLSs gradually diminished. Initially, all states expressed environmental concerns, particularly those vulnerable to sea-level rise, such as small island states and disadvantaged states like LLSs. As negotiations progressed, enthusiasm for environmental issues waned, shifting towards benefit-sharing. This shift reflected an extractive perspective perceiving the High Seas as empty spaces with untapped resources (Lambach, 2021), as each state sought a share in this perceived wealth.

Further examination and interviews revealed additional factors at play, including a lack of trust in high-income states. These states sought a reduced burden in environmental protection, despite their history of overexploitation and environmental degradation. For LLSs, the neglect of the CHP emerged as a significant concern, seen by many representatives as the only means to establish a level playing field during the negotiations as also emphasized by Vadrot et al. (2022). This perspective was particularly evident during negotiations for the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) provisions outlined in Part IV of the BBNJ. There was a heightened demand for a reduced burden and autonomy by affluent states in the EIA process. Consequently, the state proposing an activity would have authority over determining the necessity of a thorough EIA, conducting the assessment, deciding on the activity’s continuation, implementing precautionary measures, monitoring impacts, and reporting to involved parties or the public (Articles 27-39 of the BBNJ).

While collective monitoring mechanisms like the Clearing-House Mechanism (CHM), the Scientific and Technical Body (STB), and adherence to legal frameworks (Article 29 of the BBNJ) were outlined, they rely heavily on national processes. Some states expressed concerns that involving specialized bodies like the STB after a national EIA process could lead to politicization and create a hierarchical structure (United Nations, 2023), making it challenging to establish trust in any meaningful collective mechanism. This reliance on individual state policies mirrors UNCLOS’ negotiations, which tended to favor certain states.

Paradoxically, most coastal states, whether developing or high-income, sought their own autonomy, leading to a decrease in environmental concerns and arguments related to the CHP. This left developing LLSs without agency. During the general exchange of views at the 5th BBNJ IGC, Mr. Udaya Raj Sapkota, representing the Nepal delegation, emphasized the need for an inclusive international regime for the conservation and sustainable use of biological resources, advocating for the CHP (Sapkota, 2022). Interviews with representatives from various low-income LLSs revealed that the neglect of environmental protection and CHP left benefit-sharing as the primary element for establishing a level field. Representatives expressed pressure to participate despite limited interest due to perceived lack of “legitimate interest” (pers. comm). As recorded in the author’s field notes (some responses paraphrased for clarity), one delegate articulated,

“We are generally not expected to participate in ocean discussions. Other states claim that they have more legitimate interests than we do.”

Another simply stated, “We are expected to just show up.”

Despite the author’s persistent assertion that BBNJ discussions pertained to ABNJ, and therefore all states have a legitimate interest and should voice their concerns, one respondent provided an interesting response:

“It all begins in the geographical bloc. There are a lot of interests, and ours are of least concern to other members.”

The respondent further explained that the blocs are interconnected on many levels, giving an example of the African group, which generally aligns with the Group of 77 (G77) and China. In essence, the respondent conveyed that,

“You have to understand that most landlocked states are just developing and are located in Africa and Asia. If other states (in the bloc) were to address some of our crucial interests, they may need to make compromises at the expense of their own priorities, all while other Western powers assert their own interests.”

Exploring the dynamics of negotiation blocs revealed additional factors that contribute to divisions, further isolating developing states and impeding collective action. Similar to other international negotiations like on climate change (UNFCC, 2023), participants can be categorized into five arbitral geographical groups. These include African States, Asian States, Eastern European States, Latin American and Caribbean States, and Western European States (Volger, 2010). Additionally, there is a category labelled ‘Other States,’ which encompasses Australia, Canada, Iceland, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, and the United States of America (UNFCC, 2023). These groups or states may participate either individually or in combination with various regions. Despite this division, countries often collaborate within other blocs, with the dominant ones in the context of the BBNJ being the Group of 77 and China (G77), African Group (AG), Least Developed Countries (LDCs), Landlocked States (LLSs), Small Island Developing States (SIDS), Like-Minded Group of Developing Countries (LMDC), Caribbean Community (CARICOM) and its associates, Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), European Union (EU), the Environmental Integrity Group (EIG) and the ‘Other States’. Countries may also have reservations and intervene independently when their interests are not adequately represented by their respective blocs as observed during the negotiations and other settings (e.g., Plantey and Meadows, 2007).

This practice is widespread across various states, notable with the United States of America (USA) that often acts as an individual state despite ties with several other countries (Gelfand and Dyer, 2000). The dynamics of negotiation processes, influenced by internal and external events preceding or occurring during negotiations, can also foster individualistic stances (Crump, 2011). For example, Russia’s isolation from Western blocs and allies due to the war in Ukraine resulted in a more solitary position during the BBNJ IGCs, characterized by empathetic support toward AG, G77, and China. Countries such as the United Kingdom, Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Indonesia, Korea, Japan, and China also asserted specific interests from their respective blocs, with a varying mix of cooperative and competitive approaches. China, for instance, consistently and cautiously advocated for unique interests, such as a more focused EIA process, in contrast to the G77’s push for a broader focus. This dichotomy of negotiating outgroups and in-groups (Gelfand and Dyer, 2000), further diminishes the influence and agency of representatives from disadvantaged states.

As one respondent pointed out, the blocs hierarchies and dynamics lead to some leaders, others as followers, spectators, givers, or takers. The marginalization of certain states leads to “self-landlocking,” where delegates feel isolated or constrained, hindering their full participation in international ocean negotiations. The proximity to the sea is used as a crucial determinant of who holds a significant voice, underscoring the impact of fixed geographical considerations in international negotiations.

Two major categories emerge: interest groups, consisting of representatives from powerful nations, institutions, and regional blocs that drive discussions and exert influence over decisions and expressions of solidarity. While all states and blocs represent a spectrum of interests, representatives of many landlocked states often find themselves confined to the role of expressions of solidarity, constrained by dynamics within their respective blocs or broader negotiations.

In response to a query about whether this dynamic is specific to being a small developing landlocked state or merely a landlocked state, one respondent articulated,

“…does that matter … the key idea here is that our views do not really matter. You have that label [of being landlocked] and it sticks with you”

They felt they were forced to carry the border with them (Carter and Goemans, 2011; Shachar, 2020).

When asked why do you participate in the negotiations, one respondent replied,

“…we all came for environmental protection in ABNJ, isn’t that the main focus? “.

Another implied that it was about diplomacy.

“We support their needs [referring to other members of the bloc], and we hope they will support ours on another occasion.”

Another delegate expressed:

“While we lack a coastline and the economic influence to voice our concerns as effectively as counterparts like Switzerland can, we know our shared responsibility for the oceans. As responsible global citizens, the situation is frustrating.”

In an effort to echo some of the sentiments from landlocked participants, the author gave an oral submission(s) on behalf of a delegate from an LLS which was part of a geographical bloc (both removed in this final version on request) (Sebuliba personal communication, 2023). The author emphasized the challenge of restricting the ocean when states repeatedly refused to leave the EIA scoping (now Article 31(b) of the BBNJ) open to unforeseeable impacts.

“We’re not landlocked by our own choosing. It is history that bestowed favor upon some while overlooking others. For us, it played out in the corridors of Berlin, where certain nations etched borders without considering our perspective. We’ve adapted to this reality, grappling with the uncertainty of a scenario where our coastal companions, once friendly, can turn indifferent. Living at the mercy of those who stretch their dominion to pursue their own agendas within our shared legacy. We’re restricted in access and influence over these realms. We come to these global negotiations with a sense of solidarity, to address matters that touch us all, in one way or another. The degradation of the High Seas will undoubtedly reverberate across us all.

Throughout this BBNJ process, it became evident that the marine environment and its non-human inhabitants are confronting a paradox of becoming imprisoned by their own waters. Their boundaries have been defined; their fate left in the hands of states—some of which have a track record of environmental negligence. The destiny of the High Seas hinges on whether these nations choose to mend their ways and take essential measures to safeguard these realms, or if they persist in safeguarding their self-expanding interests, regardless of environmental concerns.

The scope of an open EIA, adaptable to encompass unforeseen impacts, serves as a precautionary stance toward an uncertain future for the High Seas under state governance. Those nations with limited capacities, entertaining the notion that allowing high-income countries to oversee the High Seas as per their domestic policies and conditions will benefit them, should brace for impact. We may all be witnesses to an unparalleled environmental catastrophe” (Sebuliba, 2023).

After the submission, participants, including representatives from affluent states, were willing to further discuss the clauses. Some members within the geographic bloc internally opposed the submission, not due to concerns about the EIA scope but rather questioning why the landlocked state was now expressing its views. The statement was perceived as representing the entire bloc, despite the fact that the landlocked state (LLS) was entitled to its own opinion. The head of the LLS delegation, satisfied with the submission, cautioned against subsequent submissions without consulting the bloc. The delegate emphasized that low-income LLSs encounter challenges in expressing their opinions on oceanic matters.

“Landlocked states within the bloc are not expected to have a voice and speaking may raise concerns about whose interests you represent. Other members may believe you have been influenced by external states pushing their agendas,” the delegate explained.

Meeting another delegate at the consulate, they shared why they were not attending negotiations, pointing out empty seats without any attendees.

“I led the delegation and participated in the last three negotiations. I quickly realized it wasn’t about protecting marine biodiversity in shared space. I doubt the BBNJ is about common heritage; it is every state for itself. If you’re landlocked and developing, there’s little for you in these negotiations, maybe benefit-sharing, which I doubt works. In fact, our foreign ministry no longer wants to send delegations or technical support,” expressed the delegate (some paraphrasing may have been included for clarity).

This frustration is evident in the generally low participation or absence of many LLSs during ocean negotiations and the formulation of their national policies. For instance, in 2017, Gallo et al., in evaluating ocean commitments to the 2015 Paris Agreement, used a quantitative Marine Focus Factor (MFF) to assess how governments address marine issues in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) (Gallo et al., 2017). Predictably, LLSs scored the lowest in terms of including specific marine topics in their NDCs compared to their coastal counterparts. Coastal states, however, also displayed varying levels of commitment to ocean-related issues, influenced by historical and political factors. Many countries, even those heavily dependent on the ocean for food, jobs, and revenue, overlook critical marine aspects (Gallo et al., 2017) as well as critical marine treaties. In this specific context, it seems that many countries with low income have limited influence and typically have low participation in ocean governance.

With limited contributions to offer and much at stake, a new international principle, —use it or lose it—, appears to drive negotiations and policies regarding the marine environment. Similar to the BBNJ negotiations, states increasingly focus on and debate benefit-sharing arrangements and are less concerned about the provisions aimed at protecting the marine environment. Without addressing such issues, new forms of Flags of Convenience (Lillie, 2004) will emerge.

The BBNJ negotiations revealed nuanced perspectives on landlockedness that go beyond mere physical conditions. It can be seen as a state of separation or isolation from the ocean, indicating the inability to access it, especially in remote areas like the ABNJ. Interestingly, some lacking this ability may not be labelled as landlocked but are treated as such, while others physically landlocked may not be treated as such (Antón et al., 2014; Vrancken and Tsamenyi, 2017).

The Palestinian Gaza Strip is an example where despite having a coast and a river connecting to the sea, Israeli border blockades often force Palestinians into a “landlocked” state, limiting their access to the sea and its economic opportunities (Drysdale, 1987; Isaac, 2010; al-Shalalfeh et al., 2018). Landlockedness, therefore, manifests in both coastal and inland regions, affecting mobility, access rights, and socioeconomic factors, transcending national boundaries. In the BBNJ negotiations, low-income LLS representatives highlighted this, but in reality, it affects people in both coastal and inland areas.

This perspective emphasizes that borders, distance, and mobility are not just about Euclidean measurements but are influenced by various factors, including access (Birtchnell et al., 2019), international connectivity (Khanna, 2016; Pécoud, 2020), and technological advancements (Williams and Durrance, 2009; Ting, 2015). It challenges the notion that proximity to the sea guarantees access rights or relationships with the ocean (Foley, 2022). Governments increasingly regulate coastal resource access, justifying it for biodiversity protection (Clark, 1997; McClanahan et al., 2005). Other forms of access, such as through beaches or ocean education, are limited for certain groups (Caldwell and Segall, 2007; Chen and Tsai, 2016). Privatization of beaches (Welby, 1986; Alterman and Pellach, 2022) and limited accessibility to ocean knowledge through education further contribute to this disparity (Koulouri et al., 2019; Worm et al., 2021).

Although oceans are recognized as “global commons” (Buck, 1998) intricately woven into daily lives, they remain largely unseen and unexplored by many (Levin et al., 2019). While nearly 60 million people globally are directly engaged in fisheries and up to 600 million livelihoods depend on fish/aquaculture (FAO, 2022), the oceans remain elusive to most. Even scientists, equipped with advanced technology, are limited in their exploration to coastal areas, the ocean surface, and some parts of the deep sea (Rock et al., 2020). The vast expanses beyond the coasts, such as the High Seas, remain a mysterious realm accessible to very few (Urbina, 2019).

Despite physical distance, individuals can maintain a connection to the ocean through various means (Peters and Steinberg, 2019), such as rivers, historical associations, memories of maritime journeys, stories, visual impressions from past encounters, media portrayals, imagination, education-derived knowledge, a sense of global citizenship, or legal rights like those provided by CHP (Peters and Steinberg, 2019; Mohulatsi, 2023). The ocean holds different meanings for different people, ranging from its predominant perception as a resource in policy circles (Steinberg, 1999) to island identities, waves for surfing, and an endlessly beautiful blue world (D’Arcy, 2008; Braverman and Johnson, 2020). Physical isolation is not necessarily permanent and even species previously considered “landlocked” can come into secondary contact (Vanhove et al., 2011; Tulp et al., 2013).

States are not abstract entities but are composed of individuals (Jackman et al., 2020), who can share common experiences and connections despite geographical disparities. Viewing states as all-encompassing fixed entities overlooks a larger set of interconnected values and benefits. To address global challenges, solutions should surpass conventional approaches and consider diverse perspectives arising from these varied connections. Rather than focusing on rigid state boundaries and identities, negotiations in common spaces like ABNJ should revolve around common issues. For instance, identifying potential violations of universally agreed-upon human rights through specific management options can be a focal point. Given that the UN and international law require the existence of statehood and its elements (ex facto jus oritur) (Kunz, 1956), the negotiating states could then align themselves with the rights they believe should not be undermined and justify management options based on those rights. This approach encourages a shift towards a more interconnected, value-based methodology and the establishment of a more trustworthy system that protects shared values rather than solely relying on individual state interests that evolve over time. Moreover, this aligns with contemporary understandings of international relations. Such an approach should be established in intergovernmental negotiating committees before resolutions, as these committees lay the framework upon which negotiations proceed. In essence, addressing ocean challenges on a global scale requires prioritizing collective interests (Nguitragool, 2014; Benzie and Persson, 2019; TFDD, 2023), embracing alternative perspectives (Smith, 2012; Sammler, 2020b), and transcending static political ideologies that favor the dominance of some while marginalizing others (Titley et al., 2021; Weber et al., 2021; Jost et al., 2022).

Landlockedness is not solely about geographical distance; it is a dynamic relationship that involves social, economic, and geopolitical factors. In practice, it is a state of mind that permeates the lives and daily experiences of individuals. It affects relationships with the sea—shaping the ways in which states and individuals understand, care for, communicate with, or even manage the oceans. New forms of landlockedness can emerge, even causing the ocean itself to appear landlocked due to static boundaries. The current focus on geographical distance overlooks the complexity of this concept. As countries are marginalized by way of being physically landlocked, focus shifts away from collective action and environmental goals, and they advocate for their own economic interests. By recognizing that states are dynamic compositions of individuals with shared experiences, and establishing a value-based framework for negotiations from the outset, states can focus on contributing to common issues rather than being constrained by traditional state boundaries and interests.

SS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Financial support for the fieldwork was generously provided by the Helmholtz Institute for Functional Marine Biodiversity at the University of Oldenburg and the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research (AWI). Open access publication of this article was made possible through funding from the AWI Publication Fund.

The author expresses gratitude to Katherine G. Sammler, Kimberley Peters, Tom Nurmi, the editors and anonymous reviewers that contributed valuable comments on the drafts shaping the final version of this article. Thanks to the International Studies Association for providing access to the BBNJ negotiations and to the participants from landlocked states who provided insights during the interviews.

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Agnew J. (1994). The territorial trap: The geographical assumptions of international relations theory. Rev. Int. Political Economy 1, 53–80. doi: 10.1080/09692299408434268

Agnew J. (2008). Borders on the mind: re-framing border thinking. Ethics Global Politics 1, 175–191. doi: 10.3402/egp.v1i4.1892

al-Shalalfeh Z., Napier F., Scandrett E. (2018). Water Nakba in Palestine: Sustainable Development Goal 6 versus Israeli hydro-hegemony. Local Environ. 23, 117–124. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2017.1363728

Alterman R., Pellach C. (2022). Beach access, property rights, and social-distributive questions: A cross-national legal perspective of fifteen countries. Sustainability 14, 4237. doi: 10.3390/su14074237

Antón S. C., Potts R., Aiello L. C. (2014). Human evolution. Evolution of early Homo: an integrated biological perspective. Sci. (New York N.Y.) 345, 1236828. doi: 10.1126/science.1236828

Ball T. (2019). Ideals and Ideologies: A Reader (New York, US: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9780429286827

Bangura A. K. (2012). Strengthening ties among landlocked countries in Eastern Africa: making Prisoner’s Dilemma a strategy of collaboration. Ubuntu: Journal of Conflict and Social Transformation. 1, 1–2.

Bedolla G. L. (2005). Fluid borders: Latino power, identity, and politics in Los Angeles (Berkeley, Calif., London: University of California Press). doi: 10.1525/9780520938496

Benzie M., Persson Å. (2019). Governing borderless climate risks: moving beyond the territorial framing of adaptation. Int. Environ. Agreements 19, 369–393. doi: 10.1007/s10784-019-09441-y

Birtchnell T., Savitzky S., Urry J. (2019). Cargomobilities: Moving materials in a global age (London, UK: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9781315866673

Boulhol H., de Serres A., Molnar M. (2008). The contribution of economic geography to GDP per capita. SSRN J., 1–55. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1258222

Brand U., Vadrot A. B. M. (2013). Epistemic selectivities and the valorisation of nature: The cases of the Nagoya protocol and the intergovernmental science-policy platform for biodiversity and ecosystem services (IPBES). Law, Environment & Development Journal.

Branch A. (2013). South Sudan: From Revolution to Independence by M. LeRiche and M. Arnold London: Hurst & Company 2012. Pp. 256. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X13000451

Braverman I., Johnson E. R. (2020). Blue legalities: The life and laws of the sea (Durham: Duke University Press). doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1131dk7

Budhathoki S. S., Gelband H. (2016). Manmade earthquake: the hidden health effects of a blockade-induced fuel crisis in Nepal. BMJ Global Health 1, e000116. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000116

Caldwell M., Segall C. H. (2007). No Day at the Beach: Sea Level Rise, Ecosystem Loss, and Public Access along the California Coast. Ecol. Law Q. 34, 533–578. doi: 10.15779/Z387C3V

Carter D. B., Goemans H. E. (2011). The making of the territorial order: new borders and the emergence of interstate conflict. Int. Org. 65 (2), 275–309. doi: 10.1017/S0020818311000051

Cawley C. (2015). Colonies in conflict: The history of the British Overseas Territories (Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing).

Chen C.-L., Tsai C.-H. (2016). Marine environmental awareness among university students in Taiwan: a potential signal for sustainability of the oceans. Environ. Educ. Res. 22, 958–977. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2015.1054266

Churchill R., Lowe V., Sander A. (2022). The law of the sea (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press). doi: 10.7765/9781526159038

Clark J. R. (1997). Coastal zone management for the new century. Ocean Coast. Manage. 37, 191–216. doi: 10.1016/S0964-5691(97)00052-5

Crump L. (2011). Negotiation process and negotiation context. In Int. Negot 16, 197–227. doi: 10.1163/138234011X573011

Dahlberg A. (2015). Categories are all around us: Towards more porous, flexible, and negotiable boundaries in conservation-production landscapes. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian J. Geogr. 69, 207–218. doi: 10.1080/00291951.2015.1060258

Dallimer M., Strange N. (2015). Why socio-political borders and boundaries matter in conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 30, 132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2014.12.004

D’Arcy P. (2008). The people of the sea: Environment, identity, and history in Oceania (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press).

Davis A., Wagner J. (2006). A right to fish for a living? The case for coastal fishing people’s determination of access and participation. Ocean Coast. Manage. 49, 476–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2006.04.007

Diener A. C., Hagen J. (2012). “The practice of bordering,” in Borders. Eds. Diener A. C., Hagen J. (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press), 59–81. doi: 10.1093/actrade/9780199731503.003.0004

Drysdale A. (1987). Political conflict and Jordanian access to the sea. Geographical Rev. 77, 86. doi: 10.2307/214678

Elden S. (2013a). Secure the volume: Vertical geopolitics and the depth of power. Political Geogr. 34, 35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.12.009

FAO. (2007). The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2006 (Rome: Fisheries and Aquaculture Department).

Faye M. L., McArthur J. W., Sachs J. D., Snow T. (2004). The challenges facing landlocked developing countries. J. Hum. Dev. 5, 31–68. doi: 10.1080/14649880310001660201

Feinberg R. (2014). Multiple models of space and movement on Taumako, a Polynesian Island in the Southeastern Solomons. Ethos 42, 302–331. doi: 10.1111/etho.12055

Foley P. (2022). Proximity politics in changing oceans. Maritime Stud. 21, 53–64. doi: 10.1007/s40152-021-00253-y

Galaz V., Biermann F., Folke C., Nilsson M., Olsson P. (2012). Global environmental governance and planetary boundaries: An introduction. Ecol. Economics 81, 1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.02.023

Gallo N. D., Victor D. G., Levin L. A. (2017). Ocean commitments under the Paris Agreement. Nat. Clim Change 7, 833–838. doi: 10.1038/nclimate3422

Gelfand M., Dyer N. (2000). A cultural perspective on negotiation: progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Appl. Psychol. 49, 62–99. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00006

Goldin I., Mariathasan M. (2014). The butterfly defect: How globalization creates systemic risks, and what to do about it (Princeton: Princeton University Press). doi: 10.1515/9781400850204

Hartwell C. A. (2023). In our (frozen) backyard: the Eurasian Union and regional environmental governance in the Arctic. Climatic Change 176, 45–67. doi: 10.1007/s10584-023-03491-7

Harvey E., Gounand I., Ward C. L., Altermatt F. (2017). Bridging ecology and conservation: from ecological networks to ecosystem function. J. Appl. Ecol. 54, 371–379. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12769

Heidar T. H. (2004). “Legal Aspects of Continental Shelf Limits,” in Legal and Scientific Aspects of Continental Shelf Limits. Eds. Nordquist M. H., Moore J. N., Heidar T. (Brill | Nijhoff), 8, 19–39. Center for Oceans Law and Policy. doi: 10.1163/9789047413530_009

Heidar T. (2020). New Knowledge and Changing Circumstances in the Law of the Sea (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill | Nijhoff). 92, 1–476. doi: 10.1163/9789004437753

Hirsch P. (2020). Scaling the environmental commons: Broadening our frame of reference for transboundary governance in Southeast Asia. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 61, 190–202. doi: 10.1111/apv.12253

Hughes H., Vadrot A. B. M. (2019). Weighting the world: IPBES and the struggle over Biocultural diversity. Global Environ. Politics 19, 14–37. doi: 10.1162/glep_a_00503

Hughes H., Vadrot A. B. M. (2023). Conducting Research on Global Environmental Agreement-Making (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press). doi: 10.1017/9781009179454

Hughes Clarke J. E., Mayer L. A., Wells D. E. (1996). Shallow-water imaging multibeam sonars: A new tool for investigating seafloor processes in the coastal zone and on the continental shelf. Mar. Geophysical Res. 18, 607–629. doi: 10.1007/BF00313877

Isaac R. K. (2010). Moving from pilgrimage to responsible tourism: the case of Palestine. Curr. Issues Tourism 13, 579–590. doi: 10.1080/13683500903464218

Iyob R. (1995). The Eritrean struggle for independence: Domination, resistance, nationalism 1941-1993/Ruth Iyob (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press).

Jackman A., Squire R., Bruun J., Thornton P. (2020). Unearthing feminist territories and terrains. Political Geogr. 80, 102180. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102180

Jayakumar S., Koh T. T. B., Beckman R. C. (2014). The South China Sea disputes and law of the sea (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar). doi: 10.4337/9781783477272

John S. S. (2009). “Bolivia, war of the pacific to the national revolution 1879-1952,” in The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest. Ed. Ness I. (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Oxford, UK), 1–10.

Johnston D. M. (1988). The theory and history of ocean boundary-making (Montreal, Quebec: McGill-Queen’s Press - MQUP). doi: 10.1515/9780773561489

Jones R. (2009). Categories, borders and boundaries. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 33, 174–189. doi: 10.1177/0309132508089828

Jost J. T., Baldassarri D. S., Druckman J. N. (2022). Cognitive-motivational mechanisms of political polarization in social-communicative contexts. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1, 560–576. doi: 10.1038/s44159-022-00093-5

Kaye S. (2006). “Freedom of navigation in a post 9/11 World: Security and creeping jurisdiction,” in The Law of the Sea. Eds. Freestone D., Barnes R., Ong D. (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press), 347–364.

Kennedy D. (2002). “When renewal repeats: Thinking against the box,” in Left Legalism/Left Critique. Eds. Brown W., Halley J., Ford R. T., Berlant L., Kelman M., Lester G. (Durham, North Carolina, US: Duke University Press), 373–419.

Khanna P. (2016). Connectography: Mapping the future of global civilization (New York: Random House).

Koulouri P., Mogias A., Mokos M., Cheimonopoulou M., Realdon G., Boubonari T., et al. (2019). Ocean Literacy across the Mediterranean Sea basin: Evaluating Middle School Students’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviour towards Ocean Sciences Issues. Medit. Mar. Sci. 23, 289–301. doi: 10.12681/mms.26797

Krause J., Bruns S. (2016). Routledge handbook of naval strategy and security (London, New York NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group).

Kunz J. L. (1956). Identity and continuity of states in public international law. Am. J. Int. Law 50, 65–166. doi: 10.2307/2194610

Lambach D. (2021). The functional territorialization of the high seas. Mar. Policy 130, 104579. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104579

Lane J. M., Pretes M. (2020). Maritime dependency and economic prosperity: Why access to oceanic trade matters. Mar. Policy 121, 104180. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104180

Lee S., Bautista L. (2021). “Climate change and sea level rise,” in Frontiers in International Environmental Law: Oceans and Climate Challenges. Eds. Barnes R., Long R. (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill | Nijhoff), 194–214. doi: 10.1163/9789004372887_008

Lenin V. I. (2016). “52. The state and revolution,” in Democracy. Eds. Blaug R., Schwarzmantel J. (New York, US: Columbia University Press), 278–281.

Levin J. (2020). Nomad-State relationships in international relations (Cham: Springer International Publishing). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-28053-6

Levin L. A., Bett B. J., Gates A. R., Heimbach P., Howe B. M., Janssen F., et al. (2019). Global observing needs in the deep ocean. Front. Mar. Sci. 6. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00241

Lillie N. (2004). Global collective bargaining on flag of convenience shipping. Br. J. Ind. Relations 42, 47–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8543.2004.00304.x

Linnell J. D. C. (2016). Border controls: Refugee fences fragment wildlife. Nature 529, 156. doi: 10.1038/529156a

Liverman D. (2016). U.S. National climate assessment gaps and research needs: overview, the economy and the international context. Climatic Change 135, 173–186. doi: 10.1007/s10584-015-1464-5

Machiavelli N., Skinner Q., Price R. (2020). Machiavelli: The Prince (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press). doi: 10.1017/9781316536223

Mahler S. J., Pessar P. R. (2001). Gendered geographies of power: Analyzing gender across transnational spaces. Identities 7, 441–459. doi: 10.1080/1070289X.2001.9962675

Maxwell S. M., Hazen E. L., Lewison R. L., Dunn D. C., Bailey H., Bograd S. J., et al. (2015). Dynamic ocean management: Defining and conceptualizing real-time management of the ocean. Mar. Policy 58, 42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.03.014

Mayer L. (2020). “Climate change and the legal effects of sea level rise: An introduction to the science,” in New knowledge and changing circumstances in the Law of the Sea. Ed. Heidar T. (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill | Nijhoff), 343–357. doi: 10.1163/9789004437753_019

Mazza M. (2010). Chess on the High Seas: Dangerous times for US-China relations. American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, no. 3 (Aug 2010), 1–8. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep03095.

McAllister C. (2020). Borders inscribed on the body: Geopolitics and the everyday in the work of Martín Kohan. Bull. Lat Am. Res. 39, 453–465. doi: 10.1111/blar.13089

McClanahan T. R., Mwaguni S., Muthiga N. A. (2005). Management of the Kenyan coast. Ocean Coast. Manage. 48, 901–931. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2005.03.005

McDorman T. L. (2002). The role of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf: A technical body in a political world. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 17, 301–324. doi: 10.1163/157180802X00099

Mohulatsi M. (2023). Black aesthetics and deep water: Fish-people, mermaid art and slave memory in South Africa. J. Afr. Cultural Stud. 35, 121–133. doi: 10.1080/13696815.2023.2169909

Murphy A. B. (2010). “Intersecting geographies of institutions and sovereignty,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of International Studies. Ed. Murphy A. B. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.409

Newell D., Ommer R. E. (1999). Fishing places, fishing people: Traditions and issues in Canadian small-scale fisheries. Eds. Newell D., Ommer R. E. (Toronto, London: University of Toronto Press). doi: 10.3138/9781442674936

Nguitragool P. (2014). Environmental cooperation in Southeast Asia: ASEAN’s regime for transboundary haze pollution (London: Routledge).

Nordquist M. H., Moore J. N., Heidar T. (2004). Legal and Scientific Aspects of Continental Shelf Limits. (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill | Nijhoff) Center for Oceans Law and Policy, 8, 3-467. doi: 10.1163/9789047413530

Noyes J. (2015). “The Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Law of the Sea. Eds. Rothwell D., Elferink A.O., Scott K., Stephens T. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 91–113. doi: 10.1093/law/9780198715481.003.0005

Nurmi T. (2020). Magnificent decay: Melville and ecology (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press). doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1bhg22v

Oxman B. H. (1989). The High Seas and the International Seabed Area. 10, 526–542. Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol10/iss2/8/ (Accessed 20 January 2024).

Pécoud A. (2020). Death at the border: Revisiting the debate in light of the euro-mediterranean migration crisis. Am. Behav. Scientist 64, 379–388. doi: 10.1177/0002764219882987

Peters K. (2014). Tracking (Im)mobilities at sea: Ships, boats and surveillance strategies. Mobilities 9, 414–431. doi: 10.1080/17450101.2014.946775

Peters K. (2020). The territories of governance: unpacking the ontologies and geophilosophies of fixed to flexible ocean management, and beyond. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 375, 20190458. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2019.0458

Peters K. A., Anderson J., Davies A., Steinberg P. E. (2022). The Routledge handbook of ocean space (London: Routledge). doi: 10.4324/9781315111643

Peters K. A., Steinberg P. E. (2019). The ocean in excess: towards a more-than-wet ontology. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 9, 293–307. doi: 10.1177/2043820619872886

Pinsky M. L., Reygondeau G., Caddell R., Palacios-Abrantes J., Spijkers J., Cheung W. W. L. (2018). Preparing ocean governance for species on the move. Sci. (New York N.Y.) 360, 1189–1191. doi: 10.1126/science.aat2360

Plantey A., Meadows F. (2007). International negotiation in the twenty-first century (New York: Routledge-Cavendish (UT Austin Studies in Foreign and Transnational Law, v.5).

Potter J. (2004). “Discourse Analysis,” in Handbook of Data Analysis (SAGE Publications, Ltd, 1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road, London England EC1Y 1SP United Kingdom), 607–624.

Refisch J., Jenson J. (2016). “Transboundary collaboration in the Greater Virunga Landscape: From gorilla conservation to conflict-sensitive transboundary landscape management,” in Governance, natural resources and post-conflict peacebuilding. Eds. Bruch C., Muffett C. (Earthscan, Abingdon Oxon, New York NY), 825–842.

Reid W. V., Chen D., Goldfarb L., Hackmann H., Lee Y. T., Mokhele K., et al. (2010). Environment and development. Earth system science for global sustainability: grand challenges. Sci. (New York N.Y.) 330, 916–917. doi: 10.1126/science.1196263

Roach A. J. (2021). “Evolution of the modern Law of the Sea,” in Excessive Maritime Claims. Ed. Roach J. A. (Brill | Nijhoff), 783–810.

Rock J., Sima E., Knapen M. (2020). What is the ocean: A sea-change in our perceptions and values? Aquat. Conserv: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 30, 532–539. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3257

Rodrik D., Subramanian A., Trebbi F. (2004). Institutions rule: The primacy of institutions over geography and integration in economic development. J. Economic Growth 9, 131–165. doi: 10.1023/B:JOEG.0000031425.72248.85

United Nations (2023). Russian Federation (A/CONF.232/2023/INF.5) [Compilation of statements made by delegations under item 5, “General exchange of views”, at the further resumed fifth session of the Intergovernmental conference on an international legally binding instrument under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction, as submitted by 30 June 2023]. United Nations. Available at: https://www.un.org/bbnj/.

Sammler K. G. (2020a). “Kauri and the Whale: Oceanic matter and meaning in New Zealand,” in Blue Legalities. Eds. Braverman I., Johnson E. R. (Durham, North Carolina, US: Duke University Press), 63–84. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1131dk7

Sammler K. G. (2020b). The rising politics of sea level: demarcating territory in a vertically relative world. Territory Politics Governance 8, 604–620. doi: 10.1080/21622671.2019.1632219

Sapkota U. R. (2022). Statement delivered during the General Exchange of Views at the BBNJ IGC-V. Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, Nepal (New York: United Nations). Available at: https://www.un.org/bbnj/node/1005. (Accessed June 4, 2023).

Sardar Z. (2010). Welcome to post normal times. Futures 42, 435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2009.11.028

Scharpf F. W. (1988). The joint-decision trap: Lessons from german federalism and european integration. Public administration 66, 239–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.1988.tb00694.x

Schimmelfennig F., Leuffen D., Rittberger B. (2015). The European Union as a system of differentiated integration: interdependence, politicization and differentiation. J. Eur. Public Policy 22, 764–782. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2015.1020835

Schofield C. (2018). “Exploring the Deep Frontier,” in Global Commons and the Law of the Sea. Ed. Zou K. (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill | Nijhoff), 151–167. doi: 10.1163/9789004373334_010

Sentance A., Betts R. (2012). International dimensions of climate change. Climate Policy 12, S1–S5. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2012.735804

Shachar A. (2020). Shifting borders: Invisible, but very real. UNESCO Courier 2020, 32–33. doi: 10.18356/265d6889-en

Sharma K. (2020). Landlocked or policy-locked? The WTO review of Nepal’s trade policy. Global Business Rev. 13, 19615–19634. doi: 10.1177/0972150920976238

Smith L. T. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples/Linda Tuhiwai Smith (London: Zed Books).

Sohn L. B., Noyes J. E., Franckx E., Juras K. G. (2014). Cases and materials on the law of the sea (Leiden: Brill Nijhoff). doi: 10.1163/9789004203563

Stahl A. T., Fremier A. K., Cosens B. A. (2020). Mapping legal authority for terrestrial conservation corridors along streams. Conserv. biol.: J. Soc. Conserv. Biol. 34, 943–955. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13484

Steinberg P. E. (1999). The maritime mystique: Sustainable development, capital mobility, and nostalgia in the world ocean. Environ. Plan D 17, 403–426. doi: 10.1068/d170403

Steinberg P. E. (2001). The social construction of the ocean (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Steinberg P., Peters K. (2015). Wet ontologies, fluid spaces: Giving depth to volume through oceanic thinking. Environ. Plan D 33, 247–264. doi: 10.1068/d14148p

Tapscott D. (2014). Introducing global solution networks: Understanding the new multi-stakeholder models for global cooperation, problem solving and governance. Innovations: Technol. Governance Globalization 9, 3–46. doi: 10.1162/inov_a_00200

TFDD. (2023). Transboundary Freshwater Dispute Database. Available online at: http://transboundarywaters.science.oregonstate.edu/ (Accessed June 4, 2023).

Ting T.-Y. (2015). DIY citizenship: Critical making and social media. Eds. Ratto M., Boler M. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 294–295. doi: 10.1080/01972243.2015.1020215

Titley M. A., Butchart S. H. M., Jones V. R., Whittingham M. J., Willis S. G. (2021). Global inequities and political borders challenge nature conservation under climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, 1–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2011204118

Treaties U. S. (1958). Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone. In US foreign policy and the law of the sea (Hollick, New York, US) 15, 1606–1614.

Tuerk H. (2020). “The Rights of Land-locked States in the Law of the Sea,” in The Belt and Road Initiative and the law of the sea. Ed. Zou K. (Brill Nijhoff, Leiden, Boston), 181–199.

Tulp I., Keller M., Navez J., Winter H. V., de Graaf M., Baeyens W. (2013). Connectivity between migrating and landlocked populations of a diadromous fish species investigated using otolith microchemistry. PloS One 8, e69796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069796

UNESCO. (2021). United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development, (2021-2030). Available online at: https://oceandecade.org/ (Accessed June 4, 2023).

UNFCC. (2023). Party groupings UN member states flags. COP28 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC), Unfccc.int. Available online at: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/parties-non-party-stakeholders/parties/party-groupings (Accessed 20 January 2024).

UNGA. (1982). United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Montego Bay, Jamaica: United Nations General Assembly (UNGA)).

Uprety K. (2006). The transit regime for landlocked states: International law and development perspectives/Kishor Uprety (Washington, D.C: World Bank).

Urbina I. (2019). The outlaw ocean: Journeys across the last untamed frontier (New York: Alfred A. Knopf).

Vadrot A. B. M. (2020). Multilateralism as a ‘site’ of struggle over environmental knowledge: the North-South divide. Crit. Policy Stud. 14, 233–245. doi: 10.1080/19460171.2020.1768131

Vadrot A., Langlet A., Tessnow-von Wysocki I. (2022). Who owns marine biodiversity? Contesting the world order through the ‘common heritage of humankind’ principle. Environ. Politics 31, 226–250. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2021.1911442

Vaha M. (2023). The sea and international relations. Int. Affairs 99, 838–840. doi: 10.1093/ia/iiad023

Vanhove M. P., Kovačić M., Koutsikos N. E., Zogaris S., Vardakas L. E., Huyse T., et al. (2011). First record of a landlocked population of marine Millerigobius macrocephalus (Perciformes: Gobiidae): Observations from a unique spring-fed karstic lake (Lake Vouliagmeni, Greece) and phylogenetic positioning. Zoologischer Anzeiger - A J. Comp. Zool. 250, 195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jcz.2011.03.002

Vihma A., Mulugetta Y., Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen S. (2011). Negotiating solidarity? The G77 through the prism of climate change negotiations. Global Change Peace Secur. 23, 315–334. doi: 10.1080/14781158.2011.601853

Volger H. (2010). A concise encyclopedia of the United Nations (Leiden: Nijhoff). doi: 10.1163/ej.9789004180048.i-962

Vrancken P. H., Tsamenyi M. (2017). Landlocked States: The Law of the Sea: The African Union and its Member States (Lansdowne, South Africa: Juta, limited).

Wani I. J. (1982). An evaluation of the Convention on the Law of the Sea from the perspective of the Landlocked States. Virginia Journal of International Law 22(4), 627–666.

Weber T. J., Hydock C., Ding W., Gardner M., Jacob P., Mandel N., et al. (2021). Political polarization: Challenges, opportunities, and hope for consumer welfare, marketers, and public policy. J. Public Policy Marketing 40, 184–205. doi: 10.1177/0743915621991103

Weil P. (1989). The law of maritime delimitation: Reflections/by Prosper Weil; translated from the French by Maureen MacGlashan (Cambridge: Grotius).

Welby L. (1986). Public access to private beaches: A tidal necessity. UCLA J. Environ. Law Policy 6, 69–104. doi: 10.5070/L561018720

Wille C., Gerst D., Krämer H. (2021). Identities and methodologies of border studies. Borders Perspective 6, 1–126. doi: 10.25353/ubtr-xxxx-e930-87fc

Williams K., Durrance J. C. (2009). Social networks and social capital: Rethinking theory in community informatics. JoCI 4, 1–30. doi: 10.15353/joci.v4i3.2946

Wilmore R. L. (1986). The right of passage for the benefit of an enclosed estate. La. L. Rev. 47, 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol47/iss1/11

Wimmer A. (2013). Ethnic boundary making (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199927371.001.0001

Worm B., Elliff C., Fonseca J. G., Gell F. R., Serra-Gonçalves C., Helder N. K., et al. (2021). Making ocean literacy inclusive and accessible. Ethics. Sci. Environ. Polit. 21, 1–9. doi: 10.3354/esep00196

Keywords: landlocked states, borders, high seas, ABNJ, UNCLOS, international policy, biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ), intergovernmental negotiations

Citation: Sebuliba S (2024) The landlocked ocean: landlocked states in BBNJ negotiations and the impact of fixed land-sea relations in global ocean governance. Front. Mar. Sci. 11:1306386. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1306386

Received: 03 October 2023; Accepted: 22 April 2024;

Published: 08 May 2024.

Edited by:

Di Jin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, United StatesReviewed by:

Philip Steinberg, Durham University, United KingdomCopyright © 2024 Sebuliba. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Solomon Sebuliba, bnNheG9uOTlAZ21haWwuY29t

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.