- 1Bimini Biological Field Station Foundation, South Bimini, Bahamas

- 2School for Marine Science and Technology, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, New Bedford, MA, United States

- 3Northeast Fishery Science Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Woods Hole, MA, United States

- 4Southeast Fisheries Science Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Panama City, FL, United States

- 5College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, United States

Age and growth estimates are essential for life history modeling in elasmobranchs and are used to inform accurate conservation and management decisions. The nurse shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) is abundant in coastal waters of the Atlantic Ocean, yet many aspects of their life history remain relatively understudied, aside from their reproductive behavior. We used mark-recapture data of 91 individual G. cirratum from Bimini, The Bahamas, from 2003 to 2020, to calculate von Bertalanffy (vB) growth parameters, empirical growth rate, and age derived from the resulting length-at-age estimates. The Fabens method for estimating growth from mark-recapture methods was applied through a Bayesian framework using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods. This provided growth parameters with an asymptotic total length (L∞) of 303.28 cm and a growth coefficient (k) of 0.04 yr-1. The average growth rate for G. cirratum was approximately 8.68 ± 6.00 cm yr-1. This study also suggests that the previous maximum age for G. cirratum is likely underestimated, with the oldest individual predicted to be 43 years old. Our study is the first to present vB growth parameters and a growth curve for G. cirratum. It indicates that this species is slow-growing and long-lived, which improves our understanding of their life history.

1 Introduction

Elasmobranchs (sharks, rays, and skates) have classically been described as relatively long-lived, slow-growing and late-maturing, with long gestation periods and low fecundity (Hoenig and Gruber, 1990; Stevens et al., 2000). Due to these life history strategies, overfishing threatens over one-third of elasmobranchs with extinction (Dulvy et al., 2014; Dulvy et al., 2021). Ascertaining accurate information on life history traits, such as age and growth, can help to classify species’ potential susceptibility to anthropogenic threats (Emmons et al., 2021). Furthermore, accurate age and growth estimates are important when assessing the vulnerability of a population and determining the risk of overexploitation (Hammerschlag and Sulikowski, 2011) because these estimates are often used directly in a variety of assessment models (Hoenig and Gruber, 1990; Baje et al., 2018; Flinn and Midway, 2021).

Extensive age and growth information can be difficult to obtain for many elasmobranchs, as several of the morphometric characteristics traditionally used for aging teleosts are lacking for elasmobranchs (Beal et al., 2022). Methods used in age and growth studies for teleosts rely on counting growth rings in hard parts such as otoliths and scales, which are not present in the cartilaginous skeleton in elasmobranchs (Das, 1994; Cailliet, 2015). Therefore, reliable information is only available for a limited number of species, with research focused primarily on those frequently caught in fisheries or of conservation concern (Cailliet, 2015). Typically, accurate aging of elasmobranchs relies upon dead specimens in order to count growth band pairs in their vertebral centra. However, this method is species and potentially regionally dependent and can result in age underestimation due to uncertainty in the frequency of band formation (Cailliet, 1990; Natanson et al., 2018; Rudd et al., 2019). For instances in which age information is difficult to obtain or not available, length-increment analysis can provide an effective alternative means for determining growth (Frazier et al., 2020). Length-increment analysis involves the collection of length measurements from the same individual over time (i.e., mark-recapture) where original age is often unknown but can be estimated through length and age relationships and known time between measurements (Harry et al., 2022). This can be a preferred method for elasmobranch research because it is not subject to some of the biases and limitations present in other aging methods (Frazier et al., 2020; Dureuil et al., 2022), however the datasets needed for this analysis are rarely available.

A limitation of length-increment analysis is that it requires a fairly large sample size, which are typically small for elasmobranch studies due to the limitation of recaptures. Due to the propensity of limited data sets, methods have been developed to work with the low sample sizes and still provide valuable insight into life history parameters of the focal population (Barker et al., 2005; Harry et al., 2022). For example, Bayesian methods overcome low samples sizes by considering prior knowledge of the species of interest (Pardo et al., 2016; Caltabellotta et al., 2021; Smart and Grammer, 2021; Dureuil et al., 2022). This preceding knowledge is used to form prior distributions of possible values to estimate growth parameters from a model (Gelman et al., 2017), such as the von Bertalanffy (vB) growth function (von Bertalanffy, 1938). Data-limited assessments are further overcome when paired with Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods, which is an iterative procedure to obtain estimated parameter values that ensures sampling across the entire parameter space (Rudd et al., 2019). Applying these methods to growth models has become increasingly popular for overcoming the limited datasets in elasmobranch research (Smart and Grammer, 2021).

Nurse sharks, Ginglymostoma cirratum, are in the order Orectolobiformes (otherwise known as the carpet sharks) and are one of the most abundant shark species in shallow, coastal waters (Castro, 2000). They range from tropical West Africa and the Cape Verde islands in the eastern Atlantic, to southern Brazil and North Carolina in the western Atlantic Ocean (Castro, 2000) and display strong site fidelity (Carrier, 1985; Carrier and Luer, 1990; Chapman et al., 2005; Pratt et al., 2022; van Zinnicq Bergmann et al., 2022). Ginglymostoma cirratum were listed as data deficient by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, before being assessed as vulnerable (Carlson et al., 2021; Garzon et al., 2021). Despite their abundance and the recent focus on their conservation status, general data for the species is lacking aside from research on their reproductive behavior in the Dry Tortugas, Florida, USA (Carrier et al., 1994; Pratt and Carrier, 2001; Whitney et al., 2010; Pratt et al., 2022). Most of the life history data (i.e., maximum size and growth rate) available for G. cirratum come from the Florida Keys, USA and Brazil (Carrier and Luer, 1990; Castro, 2000; Santander-Neto et al., 2011; Ferreira et al., 2012). Castro (2000) provided some limited information for The Bahamas; however, it is the only published life history data to date for this area. Some research has assessed the demographic structure and relative abundance of this species in The Bahamas (Hansell et al., 2018; Shipley et al., 2018; Clementi et al., 2021), but significant data gaps persist. Therefore, additional research on life history traits such as age and growth are needed for the species.

Ginglymostoma cirratum are documented as abundant in the waters around Bimini, The Bahamas, with all size classes present (Hansell et al., 2018), providing an ideal study site to investigate age and growth. In this study, we use a 17-year mark-recapture dataset of G. cirratum from Bimini to (1) provide the first estimates for the vB growth parameters L∞ and k for this species, (2) determine an empirical annual growth rate for the region, and (3) estimate age based on the growth parameters and known information about their length-at-birth, L0.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study site

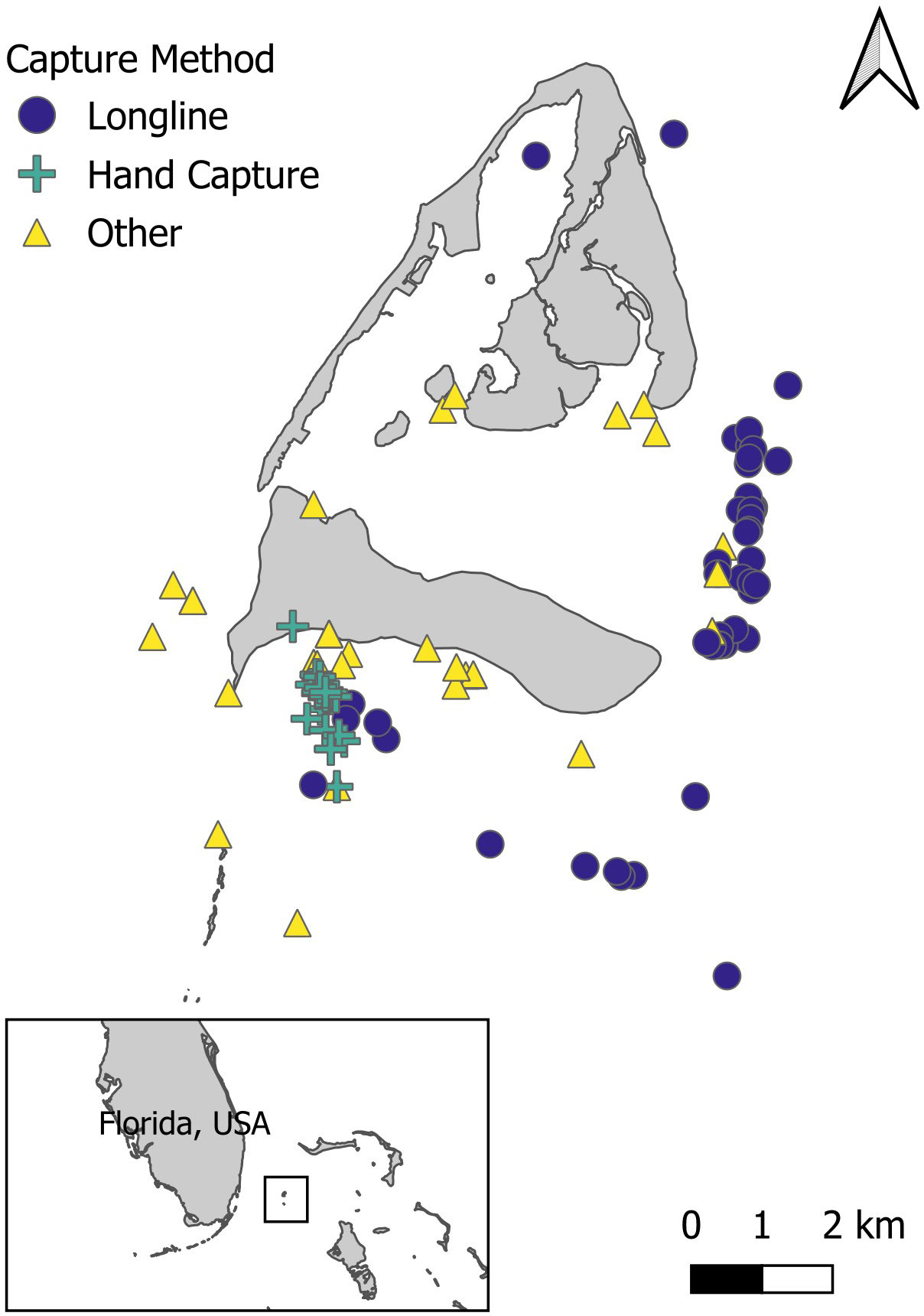

Bimini, The Bahamas, (25°73′N, -79°27′W) is a set of two islands located ~ 85 km east of Miami, Florida, USA (Figure 1). The deep waters of the Gulf Stream to the west of the island separate Bimini from Florida, while the shallow waters of the Great Bahama Bank border the east of the island. A shallow (0–3 m), tidal lagoon lies in between the North and South islands of Bimini (Trave and Sheaves, 2014). The western side of the island consists of sandy flats, reefs, and seagrass habitat (van Zinnicq Bergmann et al., 2022). Bimini’s lagoon and the east side of the island consist of mangrove-fringed and seagrass habitats that serve as nurseries for various juvenile shark species (Feldheim et al., 2002; Jennings et al., 2012; Trave and Sheaves, 2014).

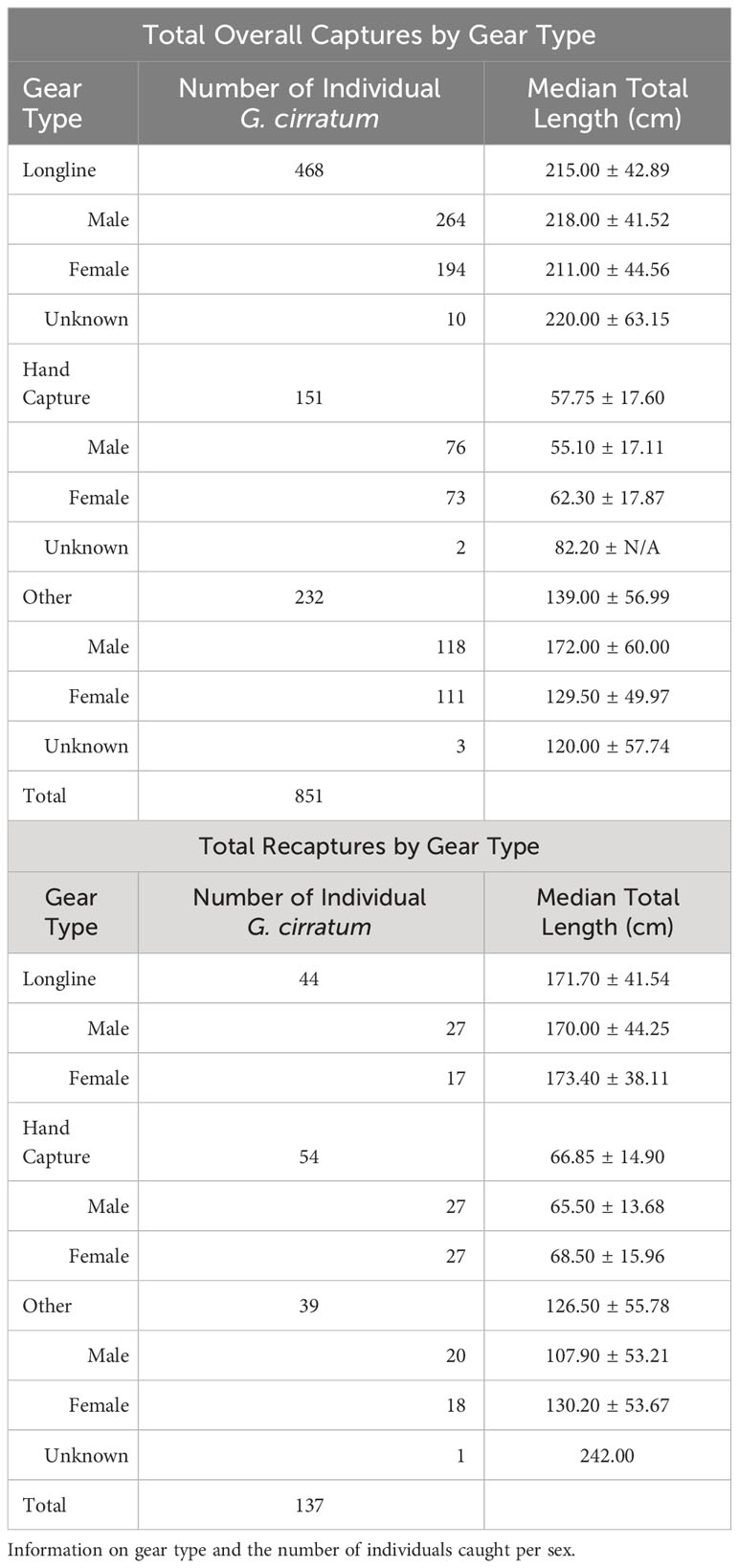

Figure 1 The study site of Bimini, The Bahamas, in proximity to Florida, USA. The colored symbols represent the capture and recapture locations of Ginglymostoma cirratum that were recaptured ≥ 90 days apart, from 2003-2020 from fishery-independent surveys using various capture methods. Captures that appear on land were in mangrove-fringed habitats.

2.2 Capture methods

Ginglymostoma cirratum were caught within a 10 km radius of Bimini from 2003–2020 during fishery-independent surveys (Figure 1). Individuals were caught using a variety of fishing methods including shallow water longline surveys (Hansell et al., 2018; Smukall et al., 2022), hand capture, and other methods consisting mostly of drumline (Gallagher et al., 2014), polyball fishing (Guttridge et al., 2017), traditional rod and reel fishing, and gillnets (Dhellemmes et al., 2021). For safe handling, larger sharks captured using a hook were measured and tagged while secured next to the boat. Hand captures of small G. cirratum were conducted by snorkeling mangrove edges or rocky ledges. They were visually identified and grasped between their gills and pectoral fins with one or two hands and brought to the surface for sampling. At the surface, the shark was placed in a tub (~150 cm diameter; 500 L volume) filled with seawater for data collection and tagging. Precaudal length (PCL) and total length (TL) measurements were recorded. The TL of the sharks was obtained by stretching a measuring tape that followed the curvature, maintaining contact with the animal from the tip of the head along the dorsal side of the body to the tip of the tail. The sex of individuals was based on the presence of claspers. Lengths at maturity for G. cirratum were determined 223–231 cm TL for females and 214 cm TL for males based on Castro (2000) or were determined on the calcification of claspers in males. Sharks were fitted with a passive integrated transponder (PIT, 12.34 mm x 2.04 mm; Destron Fearing Inc.), and/or a dart tag (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Cooperative Shark Tagging Program) placed into the musculature at the base of the first dorsal fin.

2.3 Data preparation

Ginglymostoma cirratum with captures ≥ 90 days apart were used for analysis to ensure sufficient time had passed between captures for notable growth to be detected and limit the influence of human measurement error (Simpfendorfer, 2000; Boggio-Pasqua et al., 2022). Individuals were represented in the analysis only once, despite if there were multiple recaptures, and the difference in TL and time between capture was determined based on first and last capture. We investigated the dataset for outliers and removed any recaptures with unrealistic observation error (e.g., negative growth). Separation of sexes was considered for data analysis, but given the already low sample size, sexual separation was avoided to prevent further reducing our dataset and due to no significant difference in the TLs between sexes (Supplementary Material).

2.4 Data analysis

The von Bertalanffy (vB) growth function using L0 was used as the basis for estimating age and growth from the mark-recapture data:

where Lt represents length at age t, L∞ is the asymptotic maximum length, L0 is the length-at-birth, and k is the Brody coefficient or growth constant determining how fast L∞ is approached as t nears ∞ (Equation 1). When age is unknown, length measurements from mark-recapture studies can be used in an approach called the Fabens (1965) method to solve for the parameters L∞ and k:

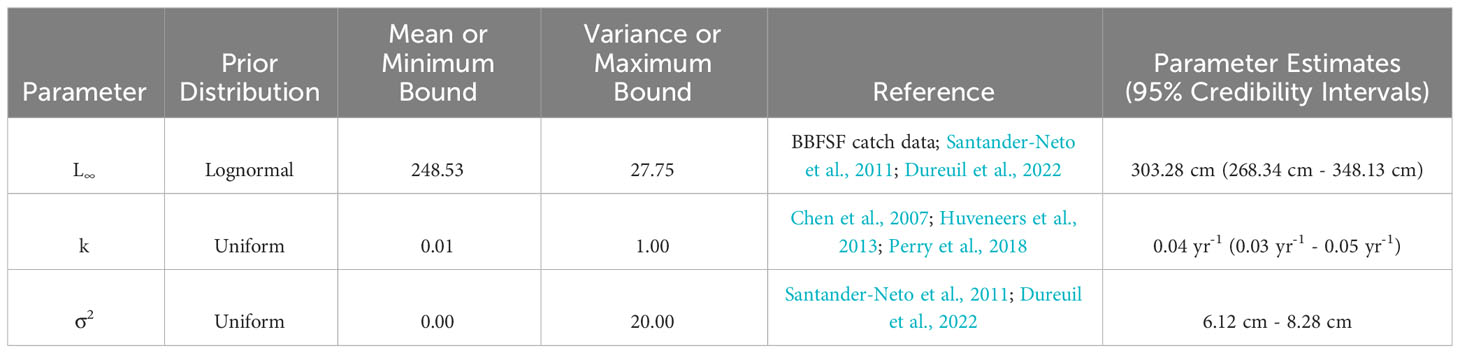

with ΔL as the expected change in length over Δt for an animal with an initial length of Lt (Equation 2; Haddon, 2011). Ginglymostoma cirratum length data was analyzed using a Fabens model with Bayesian methods (“GrowthEstimation” GitHub script; Dureuil et al., 2022 in R version v.4.3.1). The R packages ‘TMB’,’ ‘tmbstan,’ and ‘rstan’ were used to build the model. TMB uses a No-U-Turn Sampling (NUTS) algorithm to estimate the growth parameters, which is an advanced Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method (Hoffman and Gelman, 2014). A prior distribution was given to L∞, k, and σ2 (Table 1) to conduct the Bayesian inference (Gelman et al., 2014). Summary statistics were derived from the posterior distribution of the parameters given the data using the NUTS algorithm.

Table 1 Prior distributions and von Bertlanffy growth parameter estimates of Ginglymostoma cirratum near Bimini, The Bahamas.

A value for L0 was required for fitting the vB growth curve. Based on observed catch data from Bimini G. cirratum and published length-at-birth information, we assigned L0 to be 24 cm TL (Castro, 2000; Carrier et al., 2003). Smaller lengths at birth are recorded in the literature for G. cirratum (Carrier et al., 2003), however it was suggested that these pups were potentially born prematurely. The age estimations were obtained through Equation 3 to plot the vB growth curve:

When analyzing small sample sizes, a lognormal prior distribution can result in more stable MCMC iterations (Dureuil et al., 2022). This was applied to L∞ and uniform prior distributions were assigned to k and σ2. We used a lognormal prior for L∞ because there was previous information available for this parameter. To calculate the lognormal mean and standard deviation for the lognormal prior distribution of L∞, we first supplied the average maximum length (Lmax) for individuals, which was the average of the three largest individuals in our population (Dureuil et al., 2022). We obtained an Lmax of 247 cm TL, represented as the lognormal median. Next, we gave our best determination of L∞ for G. cirratum. We referenced FishBase to find previous L∞ reported for G. cirratum but were unable to confirm the reliability of this data. As a result, we searched the available literature to find an upper limit for Lmax for G. cirratum, which was 316.8 cm TL from Brazil (Santander-Neto et al., 2011). We computed L∞ from this using the upper limit of Lmax = 316.8 cm TL and taking , which resulted in an L∞ of 320 cm TL (Dureuil et al., 2021). The mean was obtained by taking log () and was 248.53 cm TL. The standard deviation was computed such that the lognormal 99th percentile was 1.2 () and was 27.75 cm TL. As there was no available data for k, we used a uniform prior distribution, which defines the lower and upper bounds for the parameter. We improved our confidence in our prior k distribution of 0.01 yr-1 to 1.00 yr-1 by using the lowest and highest published information on k for Orectolobiformes and creating a range that encompasses a realistic set of values (Chen et al., 2007; Huveneers et al., 2013; Perry et al., 2018). The uniform prior distribution used for σ2 was narrow because we had confidence in the TL measurements and was set as 0.00 cm to 20.00 cm TL.

Posterior distributions were determined from the prior distribution of the parameters (L∞, k, and σ2) and the data. Three chains were run in the Fabens model with Bayesian methods applied, each with 10,000 iterations and a burn in period of 5,000 samples. Convergence of the chains was assessed by visualizing trace and pairs plots, and the R-hat and effective sample size criteria (ESS) (Supplementary Material; Vehtari et al., 2021; Dureuil et al., 2022). Autocorrelation was assessed using diagnostic plots from the ‘Bayesplot’ R package (Gabry, 2020).

3 Results

3.1 Capture data

A total of 851 Ginglymostoma cirratum individuals (378 females, 458 males, and 15 sex not recorded) were caught between 2003–2020 in Bimini, The Bahamas (Table 2). There were 137 total individuals that were recaptured at least once for a recapture rate of 16.10%. Longline surveys and hand capture were the primary capture methods, and most individuals were caught on the east and south sides of the island (Table 2, Figure 1).

3.2 Growth analysis

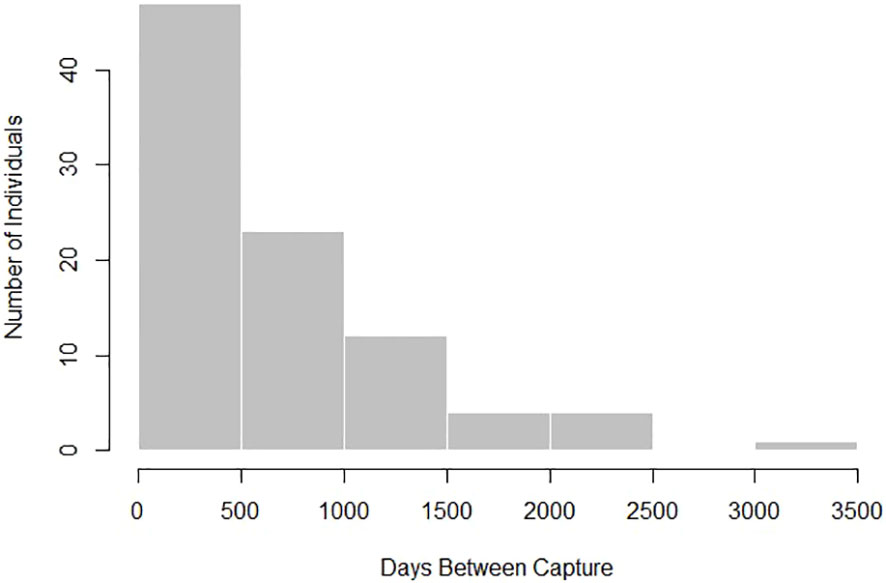

There were 91 Ginglymostoma cirratum recaptured ≥ 90 days apart used for analysis for a recapture rate of 10.69%. We removed 24 recaptures ≥ 90 days apart due to inconclusive or negative growth from human measurement error. Individuals used for analysis ranged from 48–252 cm TL at first capture (Supplementary Material). Time at liberty for the individuals caught ≥ 90 days ranged from 93–3,132 days (0.25–8.58 years, Figure 2) with an average number of days between captures of 702.30 days ± 610.18.

Figure 2 Distribution of days between first and last capture for Ginglymostoma cirratum recaptured ≥ 90 days apart near Bimini, The Bahamas.

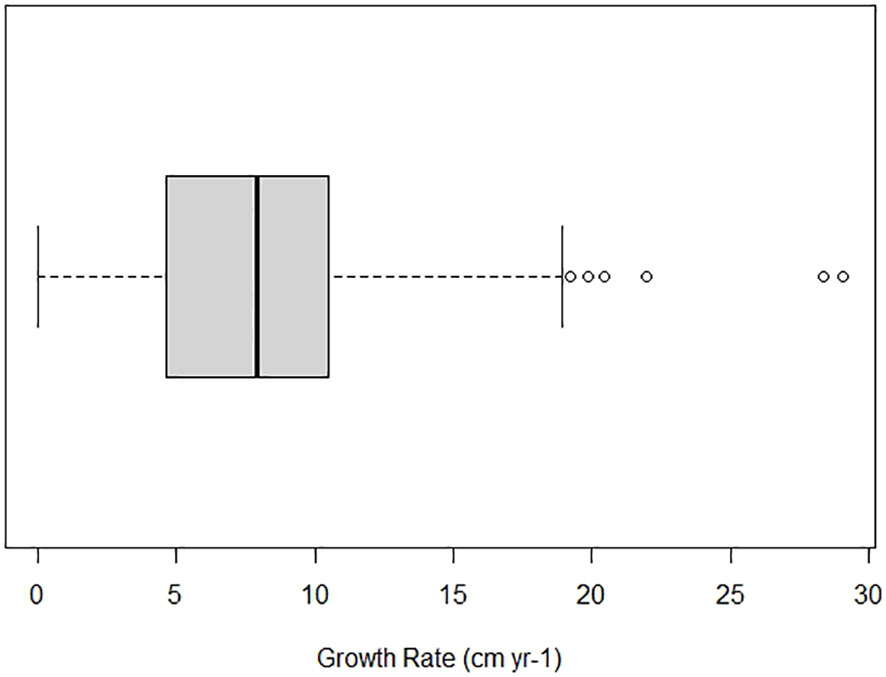

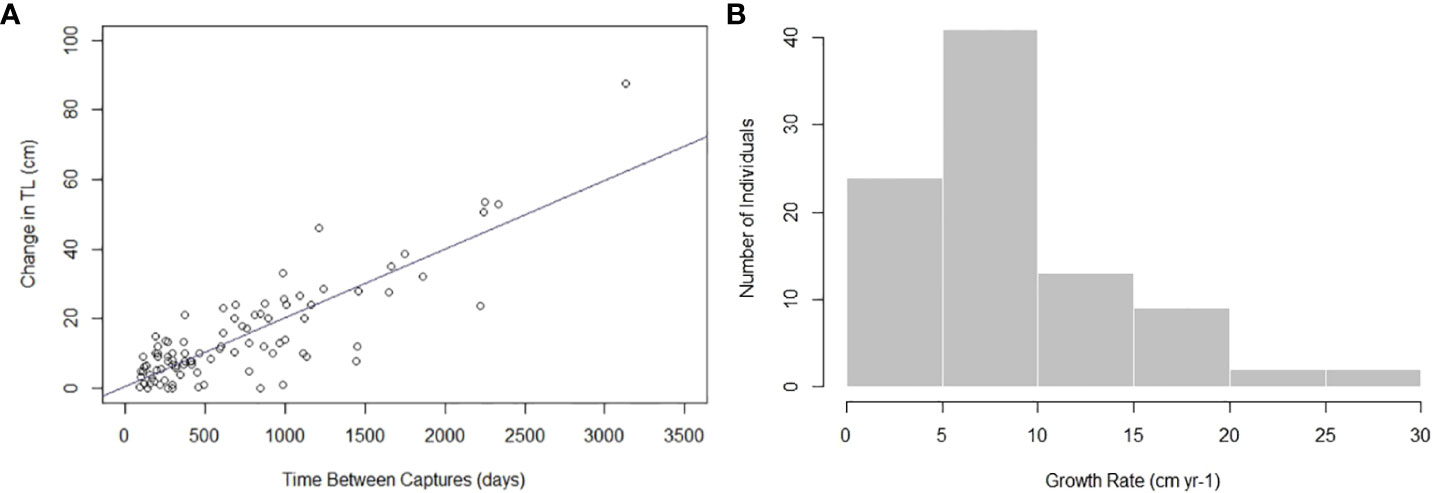

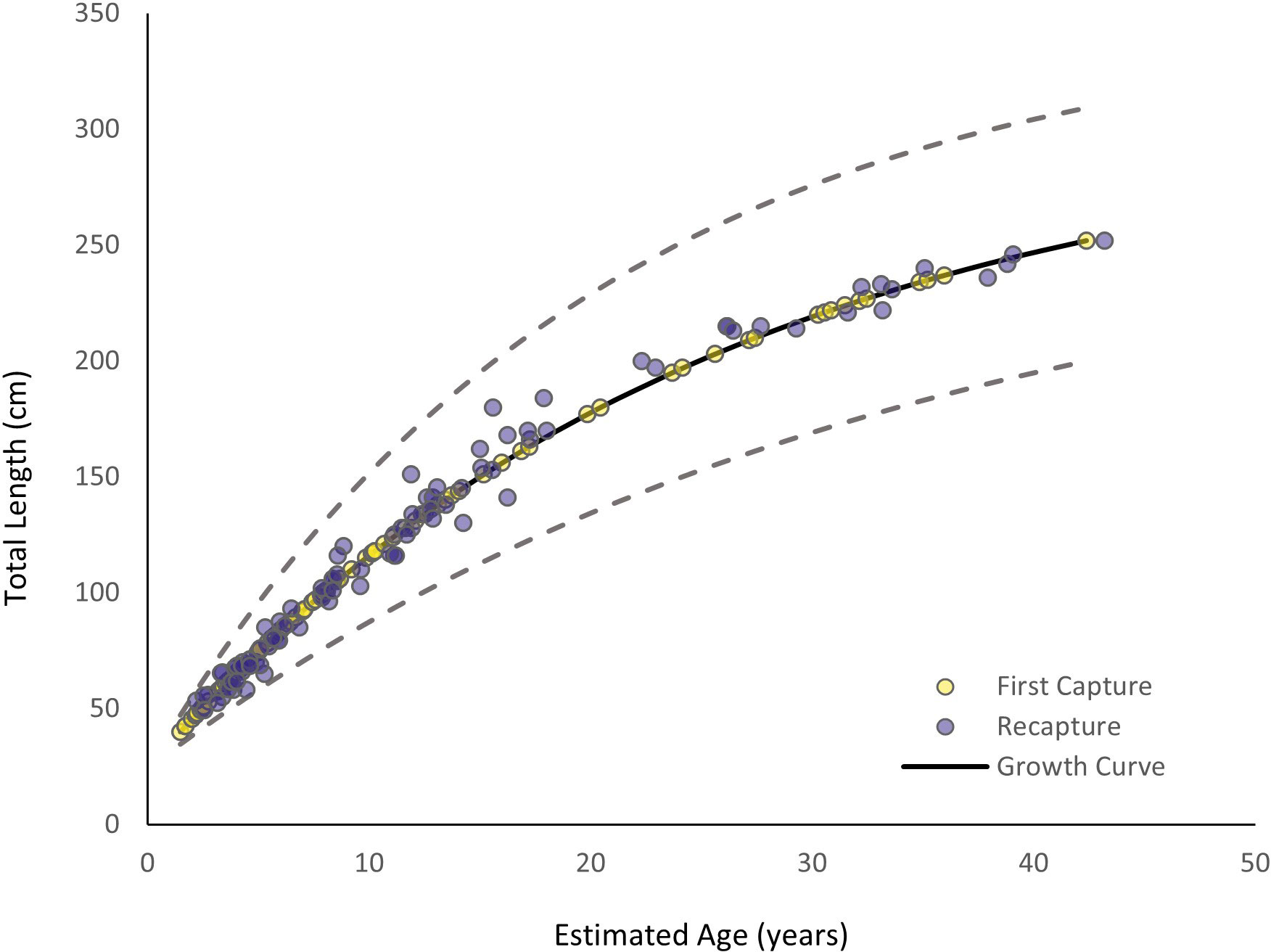

The MCMC chains mixed, indicating the model successfully converged (Supplementary Material). Autocorrelation was not present, so thinning was not applied to the model (Supplementary Material). The estimated vB growth parameters were L∞ = 303.28 cm TL (95% credibility interval [CI]: 268.34 cm TL–348.13 cm TL) and k = 0.04 yr-1 (95% CI: 0.03 yr-1–0.05 yr-1) (Table 1). The 95% CI for σ2 was 6.12 cm–8.28 cm TL (Table 1). The empirical annual growth rate for the 91 individuals was 8.68 ± 6.00 cm yr-1 (Figure 3). The change in length as a function of time at liberty for all 91 Ginglymostoma cirratum is shown in Figure 4A. Six individuals displayed growth rates between 19.21–29.07 cm yr-1 that ranged from 65.20 cm–215 cm TL at recapture. These recaptures occurred 95–375 days (0.26-1.03 years) after initial capture. Figure 4B displays the distribution of growth rates among the individuals. The vB growth curve estimated from the MCMC analysis is shown in Figure 5. Estimated ages for G. cirratum ranged from 1–43 years.

Figure 3 Annual total length (TL) growth rate of Ginglymostoma cirratum caught near Bimini, The Bahamas. The minimum value is 0 cm yr-1 while the maximum value is 18.91 cm yr-1. The first quartile is 4.65 cm yr-1 and the third quartile is 10.46 cm yr-1. The dark vertical line represents the median value at 7.88 cm yr-1.

Figure 4 (A) Change in total length (TL) for Ginglymostoma cirratum caught near Bimini, The Bahamas as a function of the number of days between captures. (B) The distribution of Ginglymostoma cirratum growth rates.

Figure 5 Von Bertalanffy growth curve for Ginglymostoma cirratum near Bimini, The Bahamas. Yellow dots represent the results at first capture while dark purple dots represent the results at recapture. The solid black line represents the overall growth curve. Ages for first capture were based on the model, and ages at recapture were based on ages at first capture plus the time between capture. The dashed lines represent 95% credibility intervals (CI).

4 Discussion

This study used a relatively large sample size of recaptured Ginglymostoma cirratum from Bimini, The Bahamas, to provide the first vB estimates for this species. Previous studies looked at growth in G. cirratum (Carrier and Luer, 1990; Ferreira et al., 2012), but they did not obtain vB estimates and only an empirical growth rate that is not directly informative for fisheries assessment models (Flinn and Midway, 2021). Since their threat level has been reassessed from data deficient to vulnerable only recently (Carlson et al., 2021; Garzon et al., 2021), having vB estimates will provide valuable information for assessing vulnerability. Furthermore, these age and growth parameters for G. cirratum can be used to directly obtain other life history parameters, such as natural mortality (M), which are influential for stock assessments (Dureuil and Froese, 2021; Dureuil et al., 2021).

Our results are indicative of G. cirratum in Bimini being slow-growing and relatively long-lived like many other elasmobranch species. These life history strategies and their large body size would put them at a greater susceptibility to threats like overexploitation and habitat destruction (Dulvy et al., 2021; Wong et al., 2022). Fishing pressure may have affected G. cirratum in the earlier years of this study, but fishing for elasmobranchs is no longer permitted in this region with the establishment of The Bahamas Shark Sanctuary in 2011 (Sherman et al., 2018). They are not afforded these same protections across their range and are a target species in some countries (Garzon et al., 2021), potentially putting their populations at risk. More species-specific life history information is needed for G. cirratum from different regions to ascertain their regional susceptibility to overexploitation. Although overfishing no longer impacts G. cirratum in Bimini, habitat alteration could still affect their life history. Destruction of habitat known to be used by G. cirratum has been occurring in Bimini since 1997 (Pratt and Carrier, 2007; Carlson et al., 2021; Bettcher et al., 2023), which includes the construction of an extensive tourist complex (Gruber and Parks, 2002; Jennings et al., 2008; Trave and Sheaves, 2014). This could have detrimental impacts on G. cirratum in Bimini if it removes habitats that are essential to their survival since their life history strategies indicate that they may not have quick recovery potential (Cortés, 2000; Gallagher et al., 2012). The Florida Keys, Florida, USA, where G. cirratum are also abundant, have a similar habitat structure and pressures to Bimini (Castro, 2000; Heithaus et al., 2007). This is notable because the Florida Keys and Bimini are close in proximity. Therefore, research on life history information from G. cirratum in this region could help better inform regional management and their response to anthropogenic disturbances.

The largest G. cirratum recaught in this study for analysis was 252 cm TL, however, a female of 280 cm TL was caught a single time. Ginglymostoma cirratum have been reported at larger TLs in the Florida Keys, USA, at 312 cm and in Brazil at 316.8 cm (Castro, 2000; Santander-Neto et al., 2011). The estimate of L∞ = 303.28 cm TL obtained for the Bimini G. cirratum population indicates that they may reach a smaller theoretical maximum length compared to other areas. Maximum size typically correlates with local habitat structure and latitude (Thorson et al., 2017), potentially contributing to the regional differences seen between the maximum sizes reported, especially since this species has the propensity for strong site fidelity (Carrier, 1985; Carrier and Luer, 1990; Chapman et al., 2005). However, individuals could reach larger lengths in Bimini due to the wide 95% credibility interval for L∞ of 268.34 cm –348.13 cm TL and could have been underrepresented in our dataset.

The previously published maximum lifespan for G. cirratum was 25 years (Clark, 1963), however, a recent study from the Dry Tortugas in the Florida Keys, USA, reported observations of the oldest individual in their population being ~ 43 years and still reproductively active (Pratt et al., 2022). Our vB estimates predict that the oldest individual in our study was 43 years old, thus supporting the age observation from Pratt et al. (2022). Age data can be inconsistent and unreliable for many elasmobranchs, so although the ages are estimates from this study, it will help contribute to a better overall understanding of G. cirratum life history (Rudd et al., 2019). Accurate maximum age estimation is a key component of population modeling and important for effective management of species (Loefer and Sedberry, 2003; Brooks et al., 2016). Castro (2000)’s reported lengths-at-maturity for G. cirratum suggest they could be 20-30 years old at maturity based on our vB growth curve. Further research on age and age at maturity in this species is needed to support this claim.

Comparisons with other species are difficult to make for G. cirratum. They are the only orectolobiform that is a shallow, resident, coastal species in The Bahamas and across the Atlantic Ocean. Furthermore, species in the Orectolobiformes vary drastically in their morphology, with limited life history information available (Goto, 2001) and a great deal of variability for what data is available (Chen et al., 2007; Huveneers et al., 2013; Perry et al., 2018). General species information in their family, Ginglymostomatidae, is also severely lacking. However, based on numerous other age and growth studies, it is well-known that growth estimates can vary widely within orders and families. Because of this, future research must focus on obtaining species-specific life history information for G. cirratum from other regions to gain a more comprehensive understanding of their growth and to make biologically appropriate comparisons (Wong et al., 2022). Since our study is the first to provide age and growth estimates for G. cirratum or for the Ginglymostomatidae family, no comparisons of growth parameters are possible yet. Consequently, the empirical growth rate from our study will be examined below to demonstrate why this measure is not as informative as vB estimates and can be problematic.

The average growth rate of 8.68 ± 6.00 cm yr-1 for G. cirratum in Bimini represents a diverse range of length classes, providing a comprehensive growth representation of the population (Haddon, 2011). Previous growth rate determination for G. cirratum only included sexually immature individuals (Carrier and Luer, 1990; Ferreira et al., 2012). The exclusion of adults creates disproportionate growth rates in favor of faster growth associated with early life stages (Francis and Francis, 1992). This could have been due to the different gear types used that can present bias towards certain capture lengths and impact estimates of growth rate (Gwinn et al., 2010; Emmons et al., 2021; Smart and Grammer, 2021; Smukall et al., 2021). Adults were included in our sample size, according to reported lengths-at-maturity from Castro (2000) and observations of calcified claspers from Bimini catch data. Growth rate can also fluctuate and vary regionally depending on changes in food availability, predation, and temperature (Hutchings, 2002; Thorson et al., 2017; Grimmel et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021), even at very small scales (Dibattista et al., 2007), further complicating the validity of empirical growth rates from localized datasets being expanded for describing the overall growth in a population.

Our study included G. cirratum from a variety of length classes and used many gear types and tackles, likely presenting the most representative growth rate for this species to date. However, we advocate for future research to focus on determining vB growth estimates for G. cirratum because of the difficulties present in comparing empirical growth rates within species that was outlined in the previous paragraph. Although also influenced by size ranges and habitat influences (Cailliet and Goldman, 2004), the growth coefficient is a more informative measure than an empirical growth rate because it may be linked to longevity, fecundity, and size at maturity (Mejía-Falla et al., 2014). Obtaining vB growth estimates using Bayesian methods additionally helps reduce biases, such as missing length classes and gear selectivity, because of the use of prior information (Pardo et al., 2016; Smart and Grammer, 2021). We were able to account for neonates in the vB estimates because of the L0 parameter. This was missing for obtaining our empirical growth rate due to no recaptured individuals from this length class. Overall, future research should focus on obtaining vB growth estimates for G. cirratum to allow for more biologically appropriate comparisons.

Without previous life history information available for G. cirratum, their conservation and management were poorly informed before this study, demonstrated by their recent vulnerability status despite being an abundant species. Although afforded protections in The Bahamas, G. cirratum are subject to different anthropogenic threats across their range and accurate age and growth estimates from other regions do not yet exist. We urge future research to obtain species-specific age and growth estimates that can be used to make comparisons between populations from different regions and inform future stock assessments. This information is important since our results demonstrate that this species is slow-growing, large-bodied, and long-lived, characteristics that can make elasmobranch species more susceptible to anthropogenic threats.

4.1 Conclusions

This study presented the first vB estimates for Ginglymostoma cirratum, around Bimini, The Bahamas. It also determined the average growth rate for G. cirratum in this region and estimated ages based on length-increment data. The growth information resulting from this study indicated that G. cirratum are slow-growing, capable of reaching large sizes, and longer lived than previously thought. These results addressed a significant data gap for G. cirratum, contributing to a better understanding of their life history which can be incorporated into conservation and management decisions.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study was over a long duration and across multiple surveys, therefore, beyond the scope of a single IACUC. However, the similar methodology for capture, handling, and data collection has been approved through IACUC protocols. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

BF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft. LB: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AH: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. JC: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. All funding provided through Bimini Biological Field Station Foundation and Save Our Seas Foundation grant #260.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr. Samuel Gruber and the numerous Bimini Biological Field Station Foundation staff and volunteers for their contributions throughout the 17 years that this project spans. We also thank Save Our Seas Foundation for their continued support. Research was carried out under permission of the Commonwealth of The Bahamas Department of Marine Resources. We are grateful for the opportunity to study in The Bahamas. Special thanks also to Dr. Félicie Dhellemmes who provided valuable input on the data analysis and project conceptualization. BBFSF also thanks Mercury Marine and CRI Boats for support of the field work. We also want to thank the reviewers for their valuable insight and attentiveness on greatly improving this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2024.1265150/full#supplementary-material

References

Baje L., Smart J. J., Chin A., White W. T., Simpfendorfer C. A. (2018). Age, growth and maturity of the Australian sharpnose shark Rhizoprionodon taylori from the Gulf of Papua. PLoS One 13 (10), e0206581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206581

Barker M. J., Gruber S. H., Newman S. P., Schluessel V. (2005). Spatial and ontogenetic variation in growth of nursery-bound juvenile lemon sharks, Negaprion brevirostris: a comparison of two age-assigning techniques. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 72, 343–355. doi: 10.1007/s10641-004-2584-3

Beal A. P., Hackerott S., Feldheim K., Gruber S. H., Eirin-Lopez J. M. (2022). Age group DNA methylation differences in lemon sharks (Negaprion brevirostris): Implications for future age estimation tools. Ecol. Evolution. 12 (8), e9226. doi: 10.1002/ece3.9226

Bettcher V. B., Franco A. C. S., Dos Santos L. N. (2023). Habitat-use of the vulnerable Atlantic Nurse Shark: a review. PeerJ 11, e15540. doi: 10.7717/peerj.15540

Boggio-Pasqua A., Bassos-Hull K., Aeberhard W. H., Hoopes L. A., Swider D. A., Wilkinson K. A., et al. (2022). Whitespotted Eagle Ray (Aetobatus Narinari) age and growth in wild (in situ) versus aquarium-housed (ex situ) individuals: Implications for conservation and management. Front. Mar. Science. 9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.960822

Brooks J. L., Guttridge T. L., Franks B. R., Grubbs R. D., Chapman D. D., Gruber S. H., et al. (2016). Using genetic inference to re-evaluate the minimum longevity of the lemon shark Negaprion brevirostris. J. Fish Biol. 88 (5), 2067–2074. doi: 10.1111/jfb.12943

Cailliet G. M. (1990). Elasmobranch age determination and verification: an updated review. NOAA Tech. Rep. NMFS. 90, 157–165.

Cailliet G. M. (2015). Perspectives on elasmobranch life-history studies: a focus on age validation and relevance to fishery management. J. Fish Biol. 87 (6), 1271–1292. doi: 10.1111/jfb.12829

Cailliet G. M., Goldman K. J. (2004). “Age determination and validation in chondrichthyan fishes,” in Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives. Eds. Carrier J., Musick J. A., Heithaus M. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press), 399–447.

Caltabellotta F. P., Siders Z. A., Cailliet G. M., Motta F. S., Gadig O. B. (2021). Preliminary age and growth of the deep-water goblin shark Mitsukurina owstoni (Jordan 1898). Mar. Freshw. Res. 72 (3), 432–438. doi: 10.1071/MF19370

Carlson J., Charvet P., Blanco-Parra M. P., Briones Bell-Lloch A., Cardenosa D., Derrick D., et al. (2021). Ginglymostoma cirratum: The IUCN red list of threatened species 2021. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T144141186A3095153.en

Carrier J. C. (1985). Nurse sharks of Big Pine Key: comparative success of three types of external tags. Florida Scientist. 48 (3), 146–154.

Carrier J. C., Luer C. A. (1990). Growth rates in the nurse shark, Ginglymostoma cirratum. Copeia 1990 (3), 686–692. doi: 10.2307/1446435

Carrier J. C., Murru F. L., Walsh M. T., Pratt J. H.L. (2003). Assessing reproductive potential and gestation in nurse sharks (Ginglymostoma cirratum) using ultrasonography and endoscopy: an example of bridging the gap between field research and captive studies. Zoo Biol. 22 (2), 179–187. doi: 10.1002/zoo.10088

Carrier J. C., Pratt H. L. Jr., Martin L. K. (1994). Group reproductive behaviors in free-living nurse sharks, Ginglymostoma cirratum. Copeia 1994 (3), 646–656. doi: 10.2307/1447180

Castro J. I. (2000). The biology of the nurse shark, Ginglymostoma cirratum, off the Florida east coast and the Bahama Islands. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 58, 1–22. doi: 10.1023/A:1007698017645

Chapman D. D., Pikitch E. K., Babcock E., Shivji M. S. (2005). Marine reserve design and evaluation using automated acoustic telemetry: a case-study involving coral reef-associated sharks in the Mesoamerican Caribbean. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 39 (1), 42–55. doi: 10.4031/002533205787521640

Chen W. K., Chen P. C., Liu K. M., Wang S. B. (2007). Age and growth estimates of the whitespotted bamboo shark, Chiloscyllium plagiosum, in the northern waters of Taiwan. Zoological Stud. 46 (1), 92–102.

Clark E. (1963). “The maintenance of sharks in captivity, with a report on their instrumental conditioning,” in Sharks and Survival. Ed. Gilbert P. W. (Boston, MA, USA: DC Heath and Co), 115–149.

Clementi G. M., Babcock E. A., Valentin-Albanese J., Bond M. E., Flowers K. I., Heithaus M. R., et al. (2021). Anthropogenic pressures on reef-associated sharks in jurisdictions with and without directed shark fishing. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Series. 661, 175–186. doi: 10.3354/meps13607

Cortés E. (2000). Life history patterns and correlations in sharks. Rev. Fisheries Science. 8 (4), 299–344. doi: 10.1080/10408340308951115

Das M. (1994). Age determination and longevity in fishes. Gerontology 40 (2-4), 70–96. doi: 10.1159/000213580

Dhellemmes F., Finger J. S., Smukall M. J., Gruber S. H., Guttridge T. L., Laskowski K. L., et al. (2021). Personality-driven life history trade-offs differ in two subpopulations of free-ranging predators. J. Anim. Ecology. 90 (1), 260–272. doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.13283

Dibattista J. D., Feldheim K. A., Gruber S. H., Hendry A. P. (2007). When bigger is not better: selection against large size, high condition and fast growth in juvenile lemon sharks. J. Evolutionary Biol. 20 (1), 201–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01210.x

Dulvy N. K., Fowler S. L., Musick J. A., Cavanagh R. D., Kyne P. M., Harrison L. R., et al. (2014). Extinction risk and conservation of the world’s sharks and rays. Elife 3, e00590. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00590

Dulvy N. K., Pacoureau N., Rigby C. L., Pollom R. A., Jabado R. W., Ebert D. A., et al. (2021). Overfshing drives over one-third of all sharks and rays toward a global extinction crisis. Curr. Biol. 31 (21), 4773–4787. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.08.062

Dureuil M., Aeberhard W., Burnett K., Hueter R., Tyminski J., Worm B. (2021). Unified natural mortality estimation for teleosts and elasmobranchs. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Series. 667, 113–129. doi: 10.3354/meps13704

Dureuil M., Aeberhard W. H., Dowd M., Pardo S. A., Whoriskey F. G., Worm B. (2022). Reliable growth estimation from mark–recapture tagging data in elasmobranchs. Fisheries Res. 256, 106488. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2022.106488

Dureuil M., Froese R. (2021). A natural constant predicts survival to maximum age. Commun. Biol. 4, 641. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02172-4

Emmons S. M., D’Alberto B. M., Smart J. J., Simpfendorfer C. A. (2021). Age and growth of tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) from Western Australia. Mar. Freshw. Res. 72 (7), 950–963. doi: 10.1071/MF20291

Fabens A. J. (1965). Properties and fitting of the von Bertalanffy growth curve. Growth 29, 265–289.

Feldheim K. A., Gruber S. H., Ashley M. V. (2002). The breeding biology of lemon sharks at a tropical nursery lagoon. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 269 (1501), 1655–1661. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2051

Ferreira L. C., Afonso A. S., Castilho P. C., Hazin F. H. (2012). Habitat use of the nurse shark, Ginglymostoma cirratum, off Recife, Northeast Brazil: a combined survey with longline and acoustic telemetry. Environ. Biol. Fishes 96, 735–745. doi: 10.1007/s10641-012-0067-5

Flinn S. A., Midway S. R. (2021). Trends in growth modeling in fisheries science. Fishes 6 (1), 1. doi: 10.3390/fishes6010001

Francis M. P., Francis R. I. C. C. (1992). Growth rate estimates for New Zealand rig (Mustelus lenticulatus). Mar. Freshw. Res. 43 (5), 1157–1176. doi: 10.1071/MF9921157

Frazier B. S., Bethea D. M., Hueter R. E., McCandless C. T., Tyminski J. P., Driggers W. B. III (2020). Growth rates of bonnetheads (Sphyrna tiburo) estimated from tag-recapture data. Fishery Bulletin. 118 (4), 329–355. doi: 10.7755/FB.118.4.3

Gabry J. ,. T. M. (2020). bayesplot: Plotting for Bayesian Models. R package version 1.7.2. Available at: https://mc-stan.org/bayesplot.

Gallagher A. J., Kyne P. M., Hammerschlag N. (2012). Ecological risk assessment and its application to elasmobranch conservation and management. J. Fish Biol. 80 (5), 1727–1748. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2012.03235.x

Gallagher A. J., Serafy J. E., Cooke S. J., Hammerschlag N. (2014). Physiological stress response, reflex impairment, and survival of five sympatric shark species following experimental capture and release. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Series. 496, 207–218. doi: 10.3354/meps10490

Garzon F., Graham R. T., Baremore I., Castellanos D., Salazar H., Xiu C., et al. (2021). Nation-wide assessment of the distribution and population size of the data-deficient nurse shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum). PLoS One 16 (8), e0256532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256532

Gelman A., Hwang J., Vehtari A. (2014). Understanding predictive information criteria for Bayesian models. Stat Computing. 24, 997–1016. doi: 10.1007/s11222-013-9416-2

Gelman A., Simpson D., Betancourt M. (2017). The prior can often only be understood in the context of the likelihood. Entropy 19 (10), 555. doi: 10.3390/e19100555

Goto T. (2001). Comparative anatomy, phylogeny and cladistic classification of the order Orectolobiformes (Chondrichthyes, Elasmobranchii). Memoirs graduate school fisheries sciences Hokkaido University. 48 (1), 1–100.

Grimmel H. M., Bullock R. W., Dedman S. L., Guttridge T. L., Bond M. E. (2020). Assessment of faunal communities and habitat use within a shallow water system using non-invasive BRUVs methodology. Aquaculture Fisheries. 5 (5), 224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.aaf.2019.12.005

Gruber S. H., Parks W. (2002). Mega-resort development on Bimini: sound economics or environmental disaster? Bahamas J. Science. 9 (2), 2–18.

Guttridge T. L., Van Zinnicq Bergmann M. P., Bolte C., Howey L. A., Finger J. S., Kessel S. T., et al. (2017). Philopatry and regional connectivity of the great hammerhead shark, Sphyrna Mokarran in the U.S. and Bahamas. Front. Mar. Science. 4. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2017.00003

Gwinn D. C., Allen M. S., Rogers M. W. (2010). Evaluation of procedures to reduce bias in fish growth parameter estimates resulting from size-selective sampling. Fisheries Res. 105 (2), 75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2010.03.005

Hammerschlag N., Sulikowski J. (2011). Killing for conservation: The need for alternatives to lethal sampling of apex predatory sharks. Endangered Species Res. 14 (2), 135–140. doi: 10.3354/esr00354

Hansell A. C., Kessel S. T., Brewster L. R., Cadrin S. X., Gruber S. H., Skomal G. B., et al. (2018). Local indicators of abundance and demographics for the coastal shark assemblage of Bimini, Bahamas. Fisheries Res. 197, 34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2017.09.016

Harry A. V., Smart J. J., Pardo S. A. (2022). “Understanding the age and growth of chondrichthyan fishes,” in Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives. Eds. Carrier J., Simpfendorfer C. A., Heithaus M. R., Yopak K. E. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press), 177–202.

Heithaus M. R., Burkholder D., Hueter R. E., Heithaus L. I., Pratt C.OMMAJr. H. L., Carrier J. C. (2007). Spatial and temporal variation in shark communities of the lower Florida Keys and evidence for historical population declines. Can. J. Fisheries Aquat. Sci. 64 (10), 1302–1313. doi: 10.1139/f07-098

Hoenig J., Gruber S. (1990). Life-history patterns in the elasmobranchs: Implications for fisheries management. NOAA Tech. Rep. NMFS. 90, 1–16.

Hoffman M. D., Gelman A. (2014). The No-U-Turn sampler: adaptively setting path lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 1593–1623.

Hutchings J. A. (2002). “Life histories of fish,” in Handbook of Fish Biology and Fisheries, vol. 1 . Eds. Hart P. J. B., Reynolds D. (Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science Ltd), 149–174.

Huveneers C., Stead J., Bennett M. B., Lee K. A., Harcourt R. G. (2013). Age and growth determination of three sympatric wobbegong sharks: how reliable is growth band periodicity in Orectolobidae? Fisheries Res. 147, 413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2013.03.014

Jennings D. E., DiBattista J. D., Stump K. L., Hussey N. E., Franks B. R., Grubbs R. D., et al. (2012). Assessment of the aquatic biodiversity of a threatened coastal lagoon at Bimini, Bahamas. J. Coast. Conserv. 16, 405–428. doi: 10.1007/s11852-012-0211-6

Jennings D. E., Gruber S. H., Franks B. R., Kessel S. T., Robertson A. L. (2008). Effects of large-scale anthropogenic development on juvenile lemon shark (Negaprion brevirostris) populations of Bimini, Bahamas. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 83, 369–377. doi: 10.1007/s10641-008-9357-3

Liu K. M., Wu C. B., Joung S. J., Tsai W. P., Su K. Y. (2021). Multi-model approach on growth estimation and association with life history trait for elasmobranchs. Front. Mar. Science. 8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.591692

Loefer J. K., Sedberry G. R. (2003). Life history of the Atlantic sharpnose shark (Rhizoprionodon terraenovae) (Richardson 1836) off the southeastern United States. Fishery Bulletin. 101 (1), 75–88.

Mejía-Falla P. A., Cortés E., Navia A. F., Zapata F. A. (2014). Age and growth of the round stingray Urotrygon rogersi, a particularly fast-growing and short-lived elasmobranch. PLoS One 9 (4), e96077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096077

Natanson L. J., Skomal G. B., Hoffmann S. L., Porter M. E., Goldman K. J., Serra D. (2018). Age and growth of sharks: Do vertebral band pairs record age? Mar. Freshw. Res. 69 (9), 1440–1452. doi: 10.1071/MF17279

Pardo S. A., Kindsvater H. K., Cuevas-Zimbrón E., Sosa-Nishizaki O., Pérez-Jiménez J. C., Dulvy N. K. (2016). Growth, productivity and relative extinction risk of a data-sparse devil ray. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 33745. doi: 10.1038/srep33745

Perry C. T., Figueiredo J., Vaudo J. J., Hancock J., Rees R., Shivji M. (2018). Comparing length-measurement methods and estimating growth parameters of free-swimming whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) near the South Ari Atoll, Maldives. Mar. Freshw. Res. 69 (10), 1487–1495. doi: 10.1071/MF17393

Pratt H. L., Carrier J. C. (2001). A review of elasmobranch reproductive behavior with a case study on the nurse shark, Ginglymostoma cirratum. Environ. Biol. Fishes. 60, 157–1188. doi: 10.1023/A:1007656126281

Pratt H. L., Carrier J. C. (2007). The nurse shark, mating and nursery habitat in the Dry Tortugas, Florida. Am. Fisheries Soc. Symposium. 50, 225.

Pratt J. H. L., Pratt T. C., Knotek R. J., Carrier J. C., Whitney N. M. (2022). Long-term use of a shark breeding ground: Three decades of mating site fidelity in the nurse shark, Ginglymostoma cirratum. PLoS One 17 (10), e0275323. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275323

Rudd M. B., Thorson J. T., Sagarese S. R. (2019). Ensemble models for data-poor assessment: accounting for uncertainty in life-history information. ICES J. Mar. Science. 76 (4), 870–883. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsz012

Santander-Neto J., Shinozaki-Mendes R. A., Silveira L. M., Jucá-Queiroz B., Furtado-Neto M. A., Faria V. V. (2011). Population structure of nurse sharks, Ginglymostoma cirratum (Orectolobiformes), caught off Ceará State, Brazil, south-western Equatorial Atlantic. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom. 91 (6), 1193–1196. doi: 10.1017/S0025315410001293

Sherman K. D., Shultz A. D., Dahlgren C. P., Thomas C., Brooks E., Brooks A., et al. (2018). Contemporary and emerging fisheries in The Bahamas:Conservation and management challenges ,achievements and future directions. Fisheries Manage. Ecology. 25 (5), 319–331. doi: 10.1111/fme.12299

Shipley O. N., Murchie K. J., Frisk M. G., O’Shea O. R., Winchester M. M., Brooks E. J., et al. (2018). Trophic niche dynamics of three nearshore benthic predators in The Bahamas. Hydrobiologia 813, 177–188. doi: 10.1007/s10750-018-3523-1

Simpfendorfer C. A. (2000). Growth rates of juvenile dusky sharks Carcharhinus obscurus (Lesueur 1818) from southwestern Australia estimated from tag-recapture data. Fishery Bulletin. 98 (4), 811–822.

Smart J. J., Grammer G. L. (2021). Modernising fish and shark growth curves with Bayesian length-at-age models. PLoS One 16 (2), e0246734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246734

Smukall M. J., Carlson J., Kessel S. T., Guttridge T. L., Dhellemmes F., Seitz A. C., et al. (2022). Thirty-five years of tiger shark Galeocerdo cuvier relative abundance near Bimini, The Bahamas, and the Southeastern United States with a comparison across jurisdictional bounds. J. Fish Biol. 101 (1), 13–25. doi: 10.1111/jfb.15067

Smukall M. J., Guttridge T. L., Dhellemmes F., Seitz A. C., Gruber S. H. (2021). Effects of leader type and gear strength on catches of coastal sharks in a longline survey around Bimini, The Bahamas. Fisheries Res. 240, 105989. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2021.105989

Stevens J. D., Bonfil R., Dulvy N. K., Walker P. A. (2000). The effects of fishing on sharks, rays, and chimaeras (chondrichthyans), and the implications for marine ecosystems. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 57 (3), 476–494. doi: 10.1006/jmsc.2000.0724

Thorson J. T., Munch S. B., Cope J. M., Gao J. (2017). Predicting life history parameters for all fishes worldwide. Ecol. Applications. 27 (8), 2262–2276. doi: 10.1002/eap.1606

Trave C., Sheaves M. (2014). Bimini Islands: a characterization of the two major nursery areas; status and perspectives. SpringerPlus 3 (1), 1–9. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-270

van Zinnicq Bergmann M. P., Guttridge T. L., Smukall M. J., Adams V. M., Bond M. E., Burke P. J., et al. (2022). Using movement models and systematic conservation planning to inform marine protected area design for a multi-species predator community. Biol. Conserv. 266, 109469. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109469

Vehtari A., Gelman A., Simpson D., Carpenter B., Bürkner P. C. (2021). Rank-normalization, folding, and localization: An improved R ˆ for assessing convergence of MCMC (with discussion). Bayesian analysis. 16 (2), 667–718. doi: 10.1214/20-BA1221

von Bertalanffy L. (1938). A quantitative theory of organic growth (inquiries on growth laws. II). Hum. Biol. 10, 181–213.

Whitney N. M., Pratt J. H. L., Pratt T. C., Carrier J. C. (2010). Identifying shark mating behaviour using three-dimensional acceleration loggers. Endangered Species Res. 10, 71–82. doi: 10.3354/esr00247

Keywords: life history, elasmobranch, conservation, management, von Bertalanffy, mark-recapture

Citation: Fadool BA, Bostick KG, Brewster LR, Hansell AC, Carlson JK and Smukall MJ (2024) Age and growth estimates for the nurse shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) over 17 years in Bimini, The Bahamas. Front. Mar. Sci. 11:1265150. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1265150

Received: 22 July 2023; Accepted: 15 January 2024;

Published: 02 February 2024.

Edited by:

Elizabeth Grace Tunka Bengil, University of Kyrenia, CyprusReviewed by:

Jones Santander-Neto, Federal Institute of Espírito Santo (IFES), BrazilJonathan Smart, Queensland Government, Australia

Copyright © 2024 Fadool, Bostick, Brewster, Hansell, Carlson and Smukall. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Baylie A. Fadool, YmF5bGllLmZhZG9vbEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Baylie A. Fadool

Baylie A. Fadool Kylie G. Bostick

Kylie G. Bostick Lauran R. Brewster

Lauran R. Brewster Alexander C. Hansell

Alexander C. Hansell John K. Carlson

John K. Carlson Matthew J. Smukall

Matthew J. Smukall