- 1College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK, United States

- 2Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute, Seward, AK, United States

An increase in anthropogenic carbon dioxide is driving oceanic chemical shifts resulting in a long-term global decrease in ocean pH, colloquially termed ocean acidification (OA). Previous studies have demonstrated that OA can have negative physiological consequences for calcifying organisms, especially during early life-history stages. However, much of the previous research has focused on static exposure to future OA conditions, rather than variable exposure to elevated pCO2, which is more ecologically relevant for nearshore species. This study examines the effects of OA on embryonic and larval Pacific razor clams (Siliqua patula), a bivalve that produces a concretion during early shell development. Larvae were spawned and cultured over 28 days under three pCO2 treatments: a static high pCO2 of 867 μatm, a variable, diel pCO2 of 357 to 867 μatm, and an ambient pCO2 of 357 μatm. Our results indicate that the calcium carbonate polymorphism of the concretion phase of S. patula was amorphous calcium carbonate which transitioned to vaterite during the advanced D-veliger stage, with a final polymorphic shift to aragonite in adults, suggesting an increased vulnerability to dissolution under OA. However, exposure to elevated pCO2 appeared to accelerate the transition of larval S. patula from the concretion stage of shell development to complete calcification. There was no significant impact of OA exposure to elevated or variable pCO2 conditions on S. patula growth or HSP70 and calmodulin gene expression. This is the first experimental study examining the response of a concretion producing bivalve to future predicted OA conditions and has important implications for experimentation on larval mollusks and bivalve management.

1 Introduction

Since the initiation of the industrial revolution, human activity has dramatically increased atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) levels (Karl and Trenberth, 2003). Consequently, the ocean has absorbed almost one-third of anthropogenically produced CO2, resulting in ocean acidification (OA), an increase in the partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2), and a subsequent decrease in oceanic pH (Sabine et al., 2004). The predicted increase of oceanic pCO2 is expected to further decrease sea surface pH by 0.3-0.4 units by the year 2100 (Stocker et al., 2013). This decrease in pH will be particularly pronounced in arctic and sub-arctic climates, such as Alaska’s oceans, due to the increased solubility of CO2 gas at lower temperatures (Sabine et al., 2004; Orr et al., 2005).

Nearshore marine ecosystems are often characterized as highly dynamic, driven by fluctuations in tidal action, wave activity, freshwater input, and primary production (Carstensen and Duarte, 2019; Miller and Kelley, 2021). Specifically, seasonal booms in primary productivity can drive cyclical, diel variability between photosynthesis and respiration during certain periods of the year, leading to major pH swings over a 12-hour period (Miller and Kelley, 2021). However, OA experimental designs have historically only investigated the effects of static pCO2 on marine organisms. For marine species, habitats characterized by high carbonate chemistry variability have been theorized to increase the potential for adaptive capacity to OA (Kapsenberg and Cyronak, 2019). By designing OA experiments that consider the historic environmental exposure and natural variability in carbonate chemistry parameters a species experiences, we can begin to make more ecologically relevant predictions of species’ resilience or susceptibility to ocean change. This is vital for the effective management of fisheries species inhabiting nearshore environments.

The Pacific razor clam (Siliqua patula; Dina’ina: qiz’in; Sugpiaq: Cingtaataq) is a narrow-shelled bivalve ranging from the Aleutian Islands to Northern California (Alaska Department of Fish and Game, 2020). Razor clams inhabit sandy beaches and can range in size from 15 to 28 cm in length, depending on the region (Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, 2010; Alaska Department of Fish and Game, 2020). In Southcentral Alaska, S. patula are prized as a commercial, recreational and subsistence resource. S. patula is harvested as a subsistence resource by numerous Indigenous communities throughout Lower Cook Inlet (LCI) (Alaska Department of Fish and Game, 2022). In LCI, AK, S. patula has been harvested commercially since 1919, and constitutes the most popular recreational shellfish species in the region (Alaska Department of Fish and Game, 2020). Unfortunately, in 2015 all recreational harvest was closed along the east side of the inlet due to record low numbers in the area, the cause of which is still unclear (Olsen, 2015).

While Siliqua patula follows the typical bivalve developmental process, they deviate during their initial shell formation. S. patula produces a concretion in early shell development (Alcantar et al., in review)1, delaying the formation of more organized calcium carbonate (CaCO3) polymorphs, relative to other bivalves, in favor of a flexible, more elementally diverse shell structure during the early stages of development (Fretter and Pilkington, 1971; Hinzmann et al., 2015). The impact of OA exposure on an organism that produces a concretion during larval development remains unexplored. Given the importance of S. patula as a resource and recent population declines, investigating how S. patula will respond to the effects of OA during its early life-history is critical to understanding how this species will fare in future ocean conditions.

Ocean acidification exerts negative impacts on a variety of marine organisms, including high-latitude, intertidal species (Bacus and Kelley, 2023), and biocalcifiers such as bivalves (Kroeker et al., 2013). While OA results in a decrease in seawater pH, it can also decrease carbonate ion saturation state (Feely et al., 2008), limiting the pool of CaCO3 necessary for biocalcification (Fabry et al., 2008). The negative effects of OA are generally most pervasive during the early life-history stages of bivalves due to the critical series of events that occur during early shell formation (e.g., Kroeker et al., 2013; Kapsenberg et al., 2018). Previous research examining the effects of OA on various larval bivalve species documented shell malformation, alteration to calcification, delays in development and growth, and alterations to elemental composition (Barton et al., 2012; Frieder et al., 2014). Exposure to elevated pCO2 during larval bivalve development has also resulted in smaller shell sizes and reduced survival in Mercenaria mercenaria and Argopecten irradians (Talmage and Gobler, 2010).

Additionally, changes in gene expression under OA conditions have been documented in numerous marine bivalves (Cummings et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2016; Peng et al., 2017). Expression of heat shock protein 70 (HSP70), a known biomarker of organismal environmental stress, is significantly increased under OA exposure in bivalves (Cummings et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2016). Given the established impact of OA during early bivalve shell development (Watson et al., 2009; Bylenga et al., 2017), investigating genes, such as Calmodulin (CaM), important for the generation of calcium binding proteins involved in shell formation (Li et al., 2004) and larval settlement (Chen et al., 2012), may provide some insight into the mechanism that larval bivalves utilize to offset OA exposure.

Our goal was to characterize the response of S. patula to future OA conditions, including daily variability, an ecologically relevant dynamism that is seasonally present in LCI during the key spawning and larval periods of July and August (Southcentral Region Division of Sport Fish, 2017). Here, we provide information about the current and future sensitivity of this species under future conditions of OA, characterizing the response of larval S. patula across levels of biological organization. Our research also represents the first study that examines how a concretion-producing bivalve will respond to OA. This latter point is vital to establish a baseline for future OA work examining bivalves, particularly those with varied life-history traits.

2 Methods

2.1 Animal collection, spawning and husbandry

Adult Siliqua patula were collected from Polly Creek Beach on the West side of LCI (60°16’54.9”N, 152°27’40.5”W) on 28 June 2018. Ethical review and approval were not required for this study in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Adult clams were transported from Pacific Seafood©, Nikiski, AK, to the Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute (APMI) in Seward, AK, the same day of harvest. All individuals were inspected for injury, rubber-banded (following hatchery protocol to mimic in situ, substrate pressure conditions), and held in a 380 L flow-through seawater tank for one week to acclimate to hatchery conditions. Any individuals exhibiting shell damage were removed from the adult broodstock population. Water was pumped into to the hatchery directly from Resurrection Bay, AK, and sand filtered to 20 µm, UV treated, and filtered again using a 1-µm pleated filter before being supplied to experimental system.

After acclimation, three females were strip spawned, and the excised eggs filtered and rinsed using the process described by Alcantar et al. (in review)1. Sperm excised from two males was diluted into 1 ml of seawater, and subsequently mixed with the eggs. The egg to sperm ratio was controlled to prevent polyspermy by titering sperm, and quickly examining subsamples under a light microscope to ensure fertilization of all eggs (> 95% noted by the presence of a polar body) without incidence of polyspermy (Sewell et al., 2014). Small subsamples (40 µl) were examined under a light microscope after 120 minutes to check for the first cell division which was expected to occur at approximately 140 minutes post fertilization (Alcantar et al., in review)1. Once the two-cell stage was reached at a success rate of 75%, the zygotes were stocked at a density of 10 larvae/ml across three treatments with five replicate culture vessels per treatment (n = 5, N = 15).

Culture vessels were composed of a three-vessel structure (Supplementary Figure 1). Larvae were held in 3.78 L vessels with the bottoms replaced with 20-μm mesh and plastic feet attached to elevate the mesh so that seawater flowed throughout the entire vessel. The 3.78 L vessel was then placed inside of 7.57 L vessel with perforations evenly spaced and covered with mesh (60-μm) so that the top of the 3.78 L vessel was above the waterline inside of the vented, 7.57 L vessel. These two vessels were nested inside of a second 7.57 L vessel so that only the topmost vents were exposed above the water line of the external water bath. A lid covered the entire three-vessel structure and was plumbed so that treatment seawater could be pumped through the top of the vessels. Outflow vents on the inner 7.57 L vessel were placed strategically above the external water bath line to ensure no input from the external environment. Culture vessels were then placed inside aquaria to maintain static temperature. Feeding began on the third day post-fertilization, coinciding with hatching of the larvae. The larvae were fed phytoplankton from cultured stocks of locally collected species at APMI three times a day at a level of 150 algal cells per larva per culture vessel.

2.2 Water system, variability, and carbonate chemistry

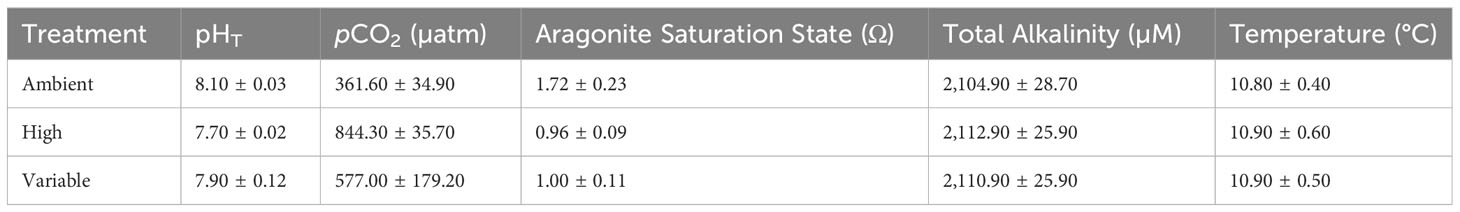

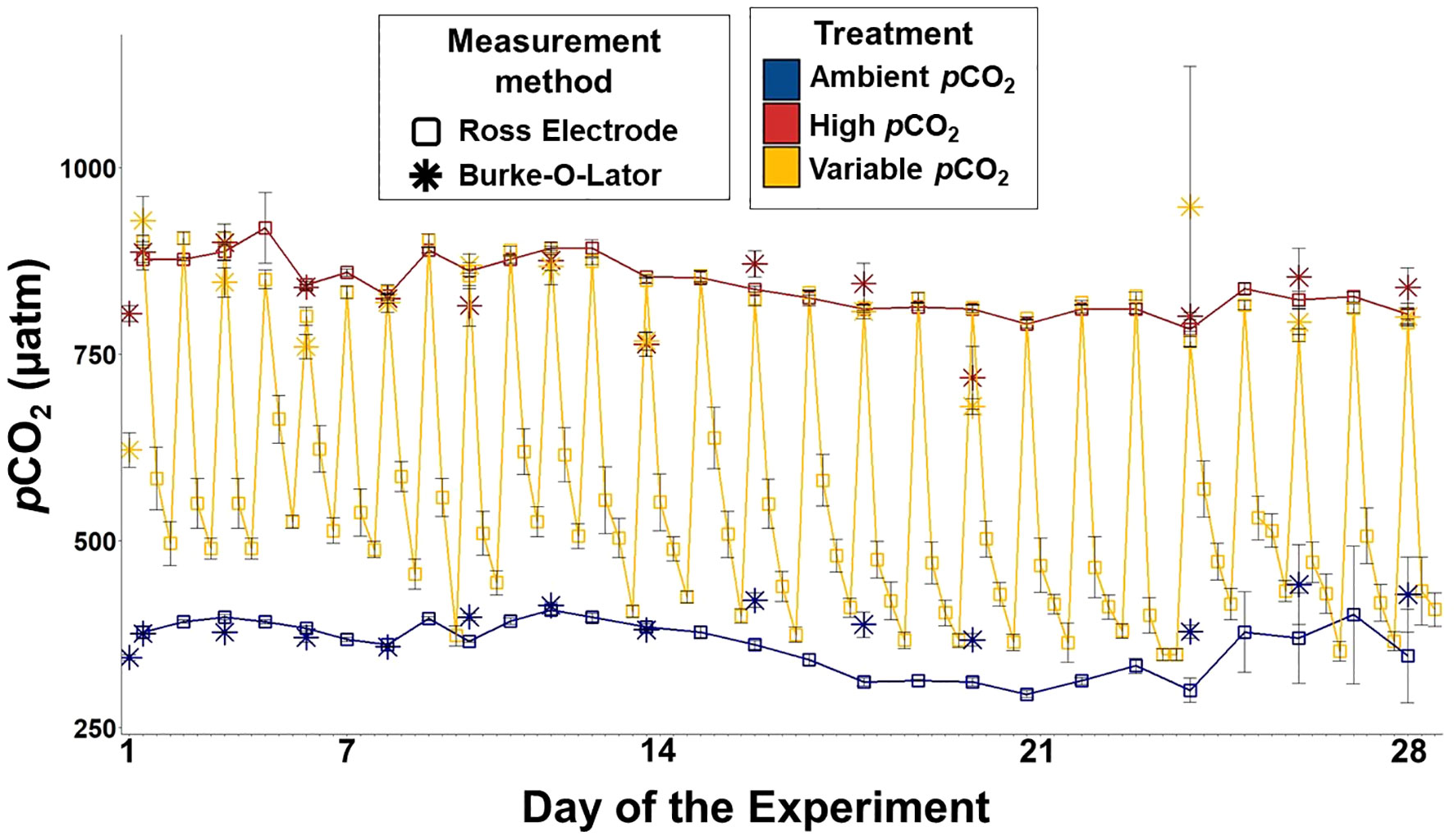

The experimental manipulation of seawater carbonate chemistry in a flowthrough system followed methods from Fangue et al. (2010). Compressed air was fed through a filtering system containing Drierite and Sodasorb to remove water and environmental CO2, respectively. This “scrubbed” air was then mixed with a discrete level of CO2 using mass flow control valves (Sierra® Instruments, Inc.) and distributed to specific reservoir tanks based on the determined ratio of CO2:scrubbed air. The CO2-enriched air was mixed with seawater using a Mazzei® Venturi Injector connected to a Supreme Aqua-Mag® 250 magnetic drive water pump (Danner® Manufacturing, Inc.) to facilitate equilibrium to the desired pCO2 concentration. Two reservoir tanks were used for this study, a target “high” pCO2 treatment of 867 μatm (7.7 pH, n = 5) and a target “ambient” pCO2 treatment of 357 μatm (8.1 pH, n = 5). These treatment levels were based off the current, ambient pCO2 conditions of LCI (Miller and Kelley, 2021) and the IPCC’s predictions for the year 2100, following Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5 (Table 1, Stocker et al., 2013), an offset of -0.4 pH units. The equivalent pCO2 was calculated and the ΔpH applied to estimate future pCO2 conditions. The variable treatment culture vessels (n = 5) were plumbed with water from both reservoir tanks and were exposed to the low pCO2 treatment during the day, from 09:00 to 21:00, and then to the high pCO2 treatment from 21:00 to 09:00 (Figure 1). This scheduled shift in pCO2 was chosen to mimic conditions in S. patula habitat on a ~12-hour cycle during known S. patula larval periods (pCO2 shifts corresponding to a ΔpH of 0.3-0.4 units), however, specific regions of LCI have demonstrated pH shifts of >1 pH unit in a 12- hour period (Miller and Kelley, 2021). Each reservoir tank distributed the treatment water to each culture vessel at a rate of 3.78 L h-1 using a button dripper.

Table 1 Mean pHT, pCO2, Ωarag, AT, and temperature with standard deviation (SD) for all treatments throughout the course of the experiment.

Figure 1 pCO2 data over the course of the experiment. The trendlines follow the Ross Electrode measurements which are represented by the empty squares. The star data points represent Burke-O-Lator measurements. Error bars denote standard deviation.

Water chemistry was measured following best practices for OA research (Dickson et al., 2007). Every other day, 0.35 L of seawater was collected from each culture vessel (N = 15), reservoir tank (n = 2) and incoming water and fixed with 200 µl of mercuric chloride prior for analysis. The dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and pCO2 of each sample was measured using APMI’s in-house Burke-O-Later. The other carbonate system parameters—pH, total alkalinity (AT) and aragonite saturation state (Ωarag) were calculated using the measured DIC and pCO2 values (Hales et al., 2004; Bandstra et al., 2006). Additionally, a Ross electrode calibrated with Tris buffer was used to measure pHT daily in the static treatments and three times daily in the variable treatment–13:00, 16:00 and 20:30 (SOP 6a Dickson et al., 2007).

2.3 Sampling

Embryos were sampled on day 1 at a concentration of approximately 5,000 individuals (n = 5 per treatment), and larvae were sampled on days 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 at a concentration of approximately 2,000, 2,000, 1,000, 1,000, and 1,000 individuals (n = 5 per treatment), respectively, for gene expression analysis. Days 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 correspond with key developmental transitions as described by Alcantar et al. (in review)1, late stage embryonic, early trochophore, onset of valve formation, early D-veliger, maturing D-veliger, and late-stage D-veliger, respectively. Larval density was estimated volumetrically by counting the number of individuals in three 40 µl in three subsamples and calculating the coefficient of variation (α < 0.05). Once larval density was established, the desired number of S. patula was sampled and preserved in 1 ml of TRIzol©, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C for later molecular analysis. It should be noted that at the time of sampling, individuals in variable treatment conditions were exposed to ambient pCO2 treatment conditions (361.60 µatm ± 34 µatm) for at least three hours prior to sampling. One hundred larvae were collected from each culture vessel (n = 5) at each time point and fixed in 70% ethanol for later shell analysis (Williams and Van Syoc, 2007).

2.4 SEM and composition

Individuals sampled from days 7, 14, 21 and 28 were analyzed using Scanning Electron Microscopy to assess larval growth, development, and composition. Individuals were pooled across culture vessels to represent each treatment (sample sizes are denoted for each treatment on growth and composition figures). These analyses were conducted at the Advanced Instrumentation Laboratory at the University of Alaska Fairbanks using an FEI Quanta 200 Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) equipped with iXRF software/hardware and an e2v SSD energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) detector. The shells were cleaned of salt with deionized water, and the periostracum was removed with a 22 minute, 3% hydrogen peroxide rinse (Green et al., 2009), using the density rinsing method described in Alcantar et al. (in review)1. Following cleaning, shells were mounted on SEM sample stubs and coated in 0.02 nm of iridium, permitting imaging under high-vacuum conditions. To measure larval length, width and area of individuals, images were analyzed using Fiji imaging software (Schindelin et al., 2012).

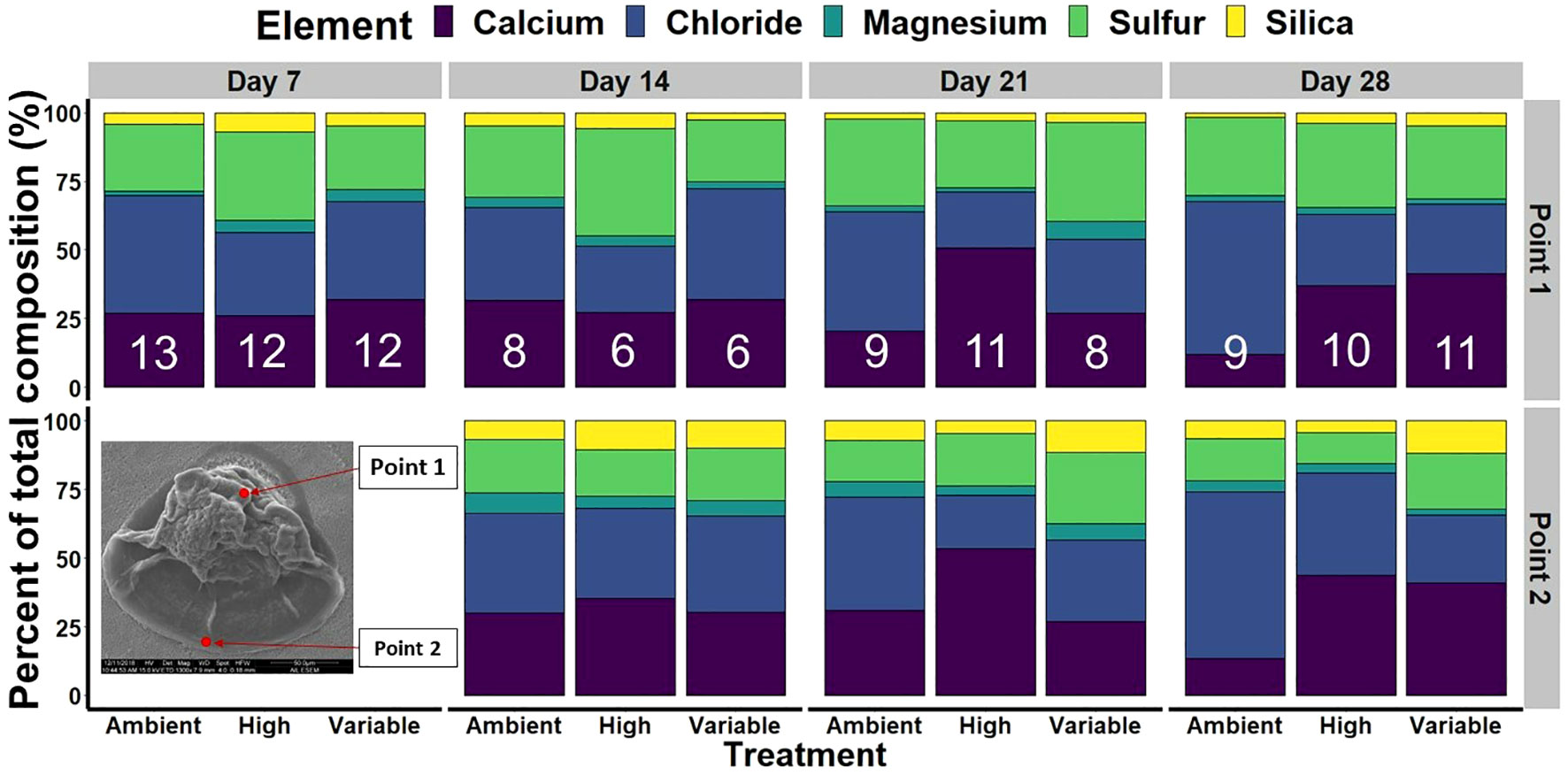

Shell composition was analyzed using the SEM via EDS. Two different locations on each shell were analyzed for composition (Figure 2, inset image). The first location was at the umbo of the shell (known as “Point 1”), and the second point at the leading edge of the shell (known as “Point 2”). Analyzing these two points on each shell allowed for the capture of compositional data from the earliest formed shell (Point 1) and the most recently formed shell (Point 2), creating a biological time-series of shell composition. EDS measurements were captured with the X-ray window set to 30 seconds at 15 kv to allow for standardized measurements at both Point 1 and Point 2. Elemental contribution was then quantified as a percentage of the total composition (Leung et al., 2017; Fitzer et al., 2018).

Figure 2 S. patula elemental composition for both shell locations, Point 1 and Point 2, over the course of the experiment. There is no Point 2 data for day 7 as the presence of a leading shell edge was inconsistent across treatments. Sample size is at the level of individual and is denoted by the white numbers present in each bar and is representative of Point 2 for each treatment at each time point.

2.5 Developmental stage

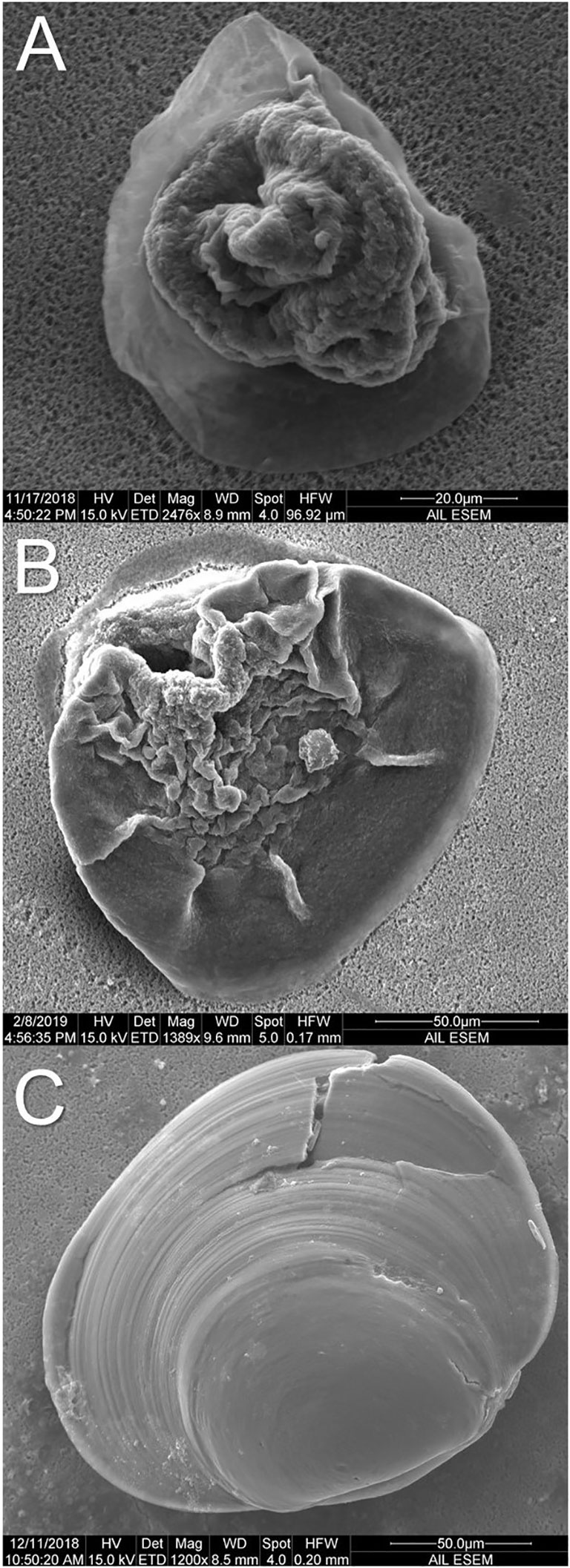

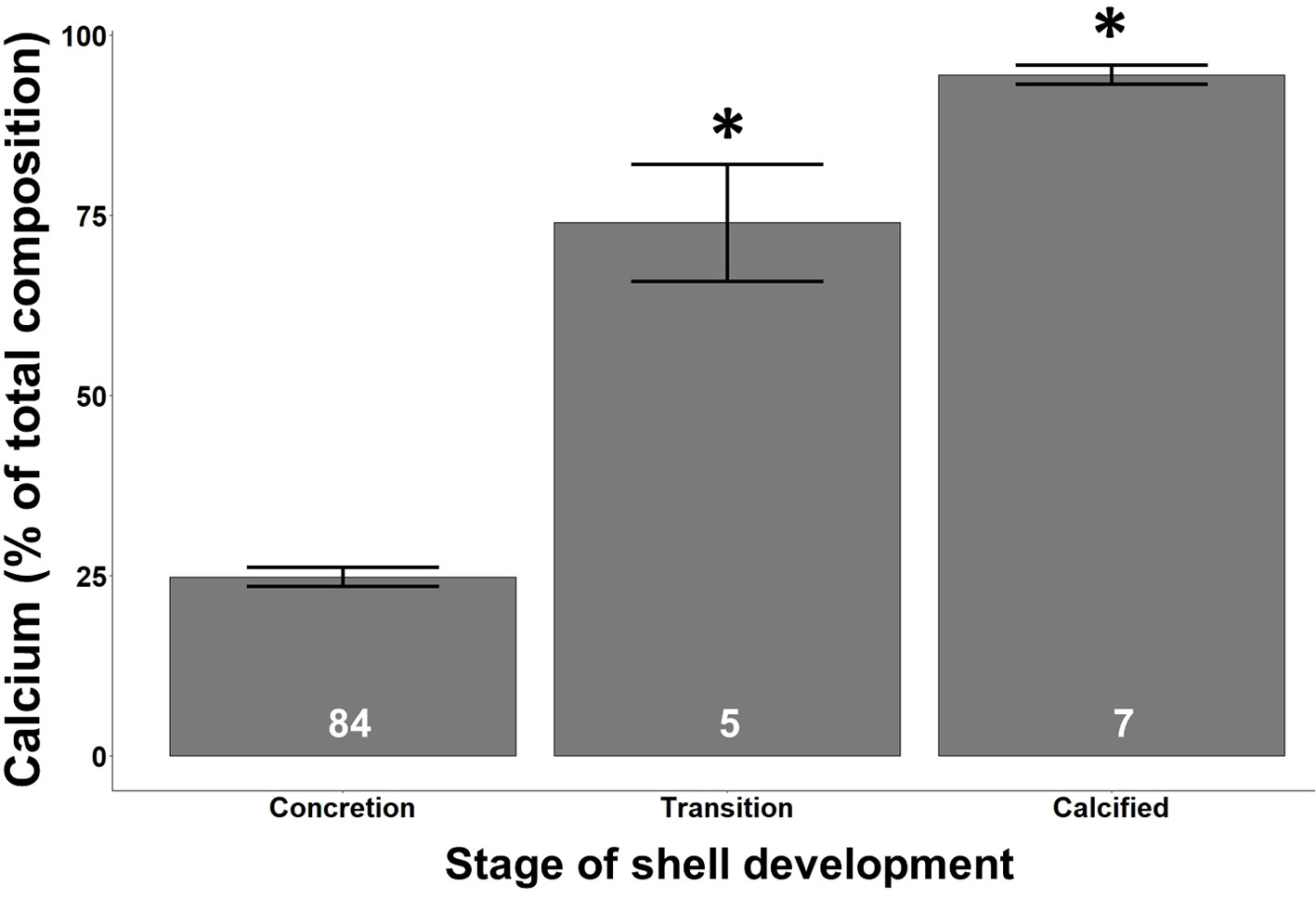

For developmental stage assessment, individuals were assigned to one of three groups: concretion, transition, or calcified individuals (Figure 3). Concretions were categorized as globular, slightly translucent, irregularly shaped individuals (Figure 3A; Alcantar et al., in review)1. Individuals in transition (Figure 3B) were characterized by the presence of opaque mineral edges–growing mineral fronts between the concretion and the shell leading edge, and progression of crystalline lamination along the leading edge. However, these individuals still maintained a globular structure near the umbo, and morphology not typically associated with other bivalve species at the same life-history stage. Fully calcified individuals were characterized by the transition from a globular structure to a more organized opaque mineral matrix and ongoing umbification (Figure 3C). Given that concretions are typically composed of a more diverse constituency of elements compared to fully mineralized shells (Eyster, 1986), the amount of calcium present in each S. patula shell (isolated as a percentage of the overall elemental composition of the individual as identified using EDS) was compared across the three developmental groups as a secondary method to assign overall shell maturity.

Figure 3 Representative micrographs of S. patula shell morphology across development. (A) S. patula using a concretion as the main shell structure (ambient pCO2 treatment, 14 DPF). (B) S. patula in transition from a concretion to a fully mineralized shell (high pCO2 treatment, 21 DPF). (C) S. patula with a fully mineralized shell (variable pCO2 treatment, 28 DPF).

2.6 Calcium carbonate crystalline structure

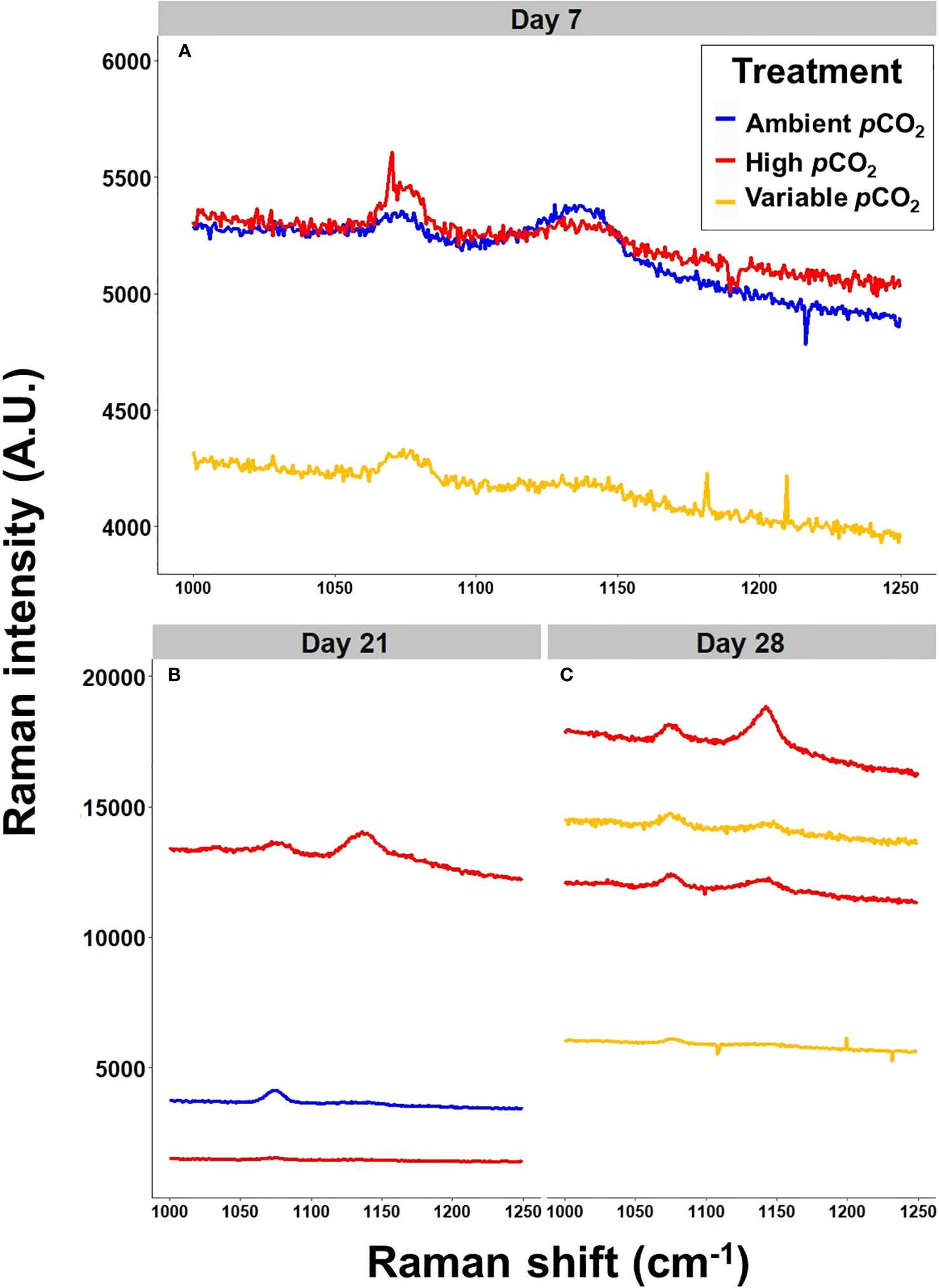

Visual identification of calcium carbonate polymorphs from SEM micrographs prompted additional Raman spectroscopy analysis to definitively identify the CaCO3 polymorphs present over time. Our analysis was limited as several of our sampling timepoints yielded few or no shells. As a result, we were unable to analyze samples from the variable treatment on day 21, nor were we able to analyze samples from the ambient treatment on day 28, as there were no shells present in the samples pulled for those treatments at those timepoints. Further, only one individual from each treatment was present in the 7 days post fertilization (DPF) sample, two high treatment individuals and one ambient treatment individual present in the 21 DPF sample, and two high and two variable individuals present in the 28 DPF sample. A Raman spectroscopy laser system was adapted to analyze the available S. patula shells. This system was only able to measure the Raman shift between 800 and 1,250 cm-1, limiting the measurement of spectra below 800. However, it captured the nature of the peak in the 1,080 cm-1 region, a distinguishing feature of the various CaCO3 polymorphs.

Shells were mounted on Raman slides and exposed to a laser beam with a 785 nm wavelength. The photon response was then measured to create an absorbed light spectrum. This spectrum is indicative of the crystalline structure, and therefore polymorph, of the calcium carbonate present (Fochesatto and Sloan, 2009). A mathematical adjustment was then applied to the generated spectrum to convert the light wavelength to the Raman spectrum, which was compared to known calcium carbonate spectra (Weiner et al., 2003; Wehrmeister et al., 2011).

In addition to the analysis of larval S. patula, we conducted an X-ray diffraction examination of the calcium carbonate polymorphism of five, LCI, S. patula adults. These individuals were collected by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game during population surveys conducted in 2017. The mid portion of a single valve from each individual was isolated from the overall shell, and the periostracum physically removed from the surface of the shell portion. The excised shell samples were then mounted on glass slides for analysis using the PANalytical X’Pert MRD Material Research Diffractometer (Malvern Panalytical, Malvern, Worcestershire, United Kingdom).

2.7 qPCR

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was used to analyze the gene expression of S. patula to elevated and variable pCO2 on days 1, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28. RNA from S. patula embryos and larvae preserved in TRIzol© was extracted using hybrid TRIzol©/Qiagen RNeasy RNA extraction protocol (all centrifuge steps were conducted at 0°C, Poole et al., 2016). First, samples were homogenized in 1 ml of TRIzol© using a micro pestle and prolonged vortexing. Following homogenization, chloroform (200 µl) was added to the sample. After vortexing briefly and a 3-minute incubation period (at room temperature), the sample was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 18 minutes. Once centrifuged, the supernatant was isolated and mixed gently with an equal volume of 100% RNA-free ethanol. This supernatant/ethanol mixture was then added to an RNeasy Mini Spin Column (RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and RNA was extracted following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Using the primer sequences identified by Bowen et al. (2020) for HSP70, CaM, and 18S (housekeeping gene), qualitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was conducted to ensure compatibility with S. patula embryos and larvae collected throughout this study. Following successful PCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed to ascertain the relative expression (ΔCT) of HSP70 and CaM, with 18S used as the housekeeping gene. These primers, built with ThermoFisher Scientific Custom DNA Oligos Synthesis Services (Waltham, Massachusetts) were combined with cDNA and Applied Biosystems™ PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix, following the manufacturer protocol (Waltham, Massachusetts) and the qPCR reaction was performed in the qTOWER3 84 G (Analytik-Jena, Jena, Germany) and included two technical replicated for each qPCR reaction. The expression of HSP70 and CaM were normalized to the 18S expression from the same sample to generate the ΔCT value for that sample. Following methodology from Livak and Schmittgen (2001), the ΔCT value for both the high and variable treatments were then normalized against the mean ambient treatment for each time point to generate the ΔΔCT value, and the data was transformed under the standard 2-ΔΔCT calculation. The 2-ΔΔCT was then divided by the number of expected individuals in the sample to produce the 2-ΔΔCT/individual.

2.8 Statistics

All statistical analyses were conducted using R (The R Development Core Team, 2013) through the Rstudio interface (version 2022.07.2). Shapiro-Wilk tests determined that the shell area, width and length, shell composition and calcium presence between the three developmental stages, HSP70 expression, and CaM expression data were non-normally distributed. As a result, Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to determine if there was a significant effect of treatment on the response variables. Statistically significant results from a Kruskal-Wallis test (p < 0.05) were subjected to a pairwise Wilcoxon post-hoc test.

3 Results

3.1 Culturing conditions

The target carbonate chemistry treatment conditions were steady and maintained throughout the duration of the experiment (Figure 1, Table 1). The ambient treatment group had a mean pCO2 of 361.60 µatm ± 34 µatm, and a pH of 8.1 ± 0.03, and the high treatment group had a mean pCO2 of 844.30 µatm ± 35 µatm, and a pH of 7.7 ± 0.02. The variable treatment group had a mean pCO2 of 577.00 µatm ± 179.20 µatm, and a pH of 7.90 ± 0.12. Salinity was 31.24 ± 0.27 and AT was invariable at 2,110.23 µM ± 4.16 µM. Temperature was kept constant at 10.5°C ± 1°C.

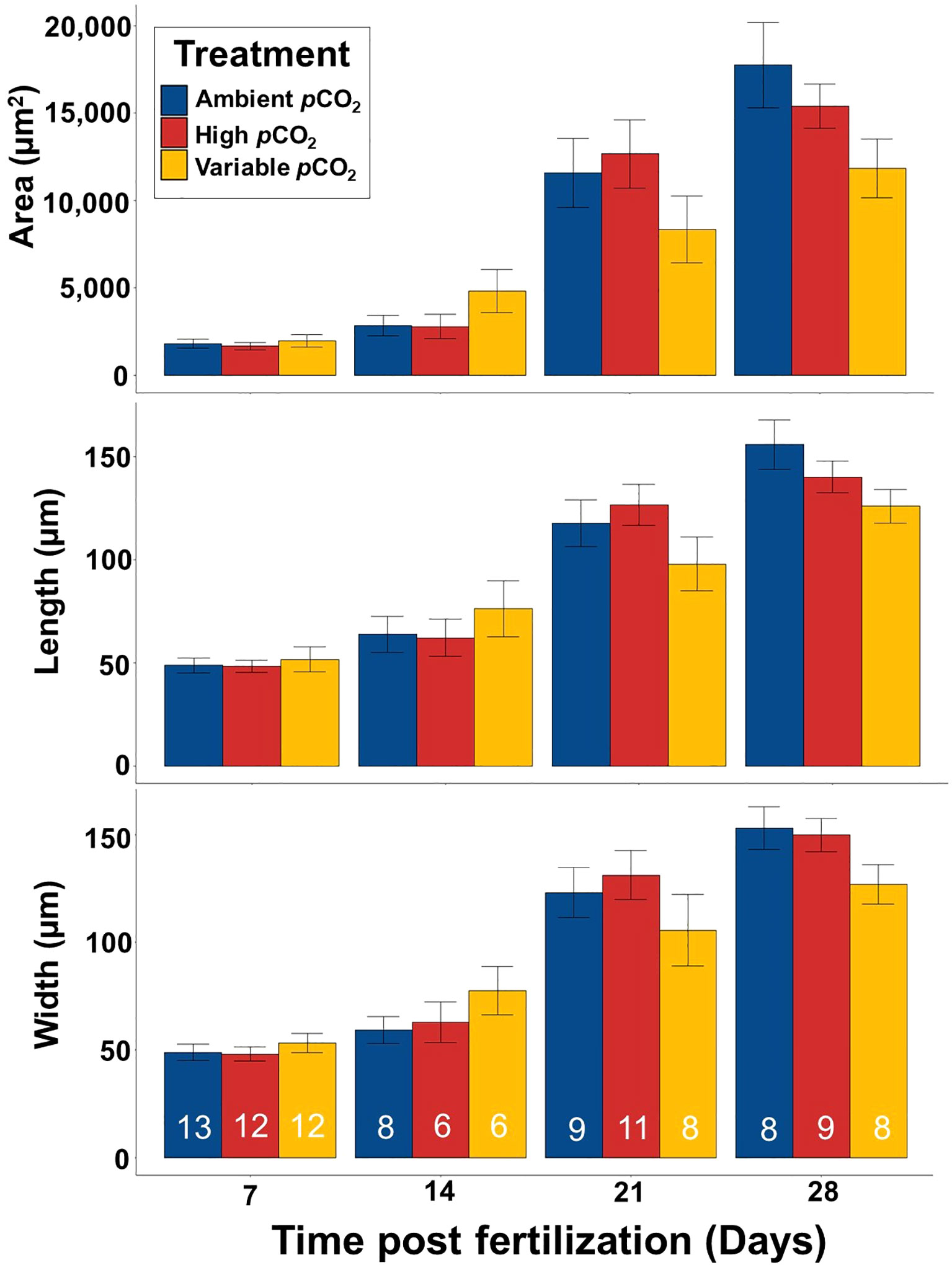

3.2 Larva size

Larval morphometrics were measured on days 7, 14, 21 and 28 using Fiji Imaging software (Figure 4; Supplementary Table 1). Unsurprisingly, larva size increased significantly between each measurement day (Kruskal Wallis, p < 0.001), with individuals increasing in area from 1,816.7 µm2 ± 961.2 µm2 on day 7 to 15,012.0 µm2 ± 5,590.6 µm2 on day 28. However, there was no significant effect of treatment on larval area (Kruskal Wallis, p = 0.67), width (Kruskal Wallis, p = 0.64), or length (Kruskal Wallis, p = 0.69).

Figure 4 Mean larval size of S. patula over the course of the experiment. Error bars denote standard error (SE). Sample size is at the level of individual and is denoted by the white numbers present in each bar.

3.3 Shell composition

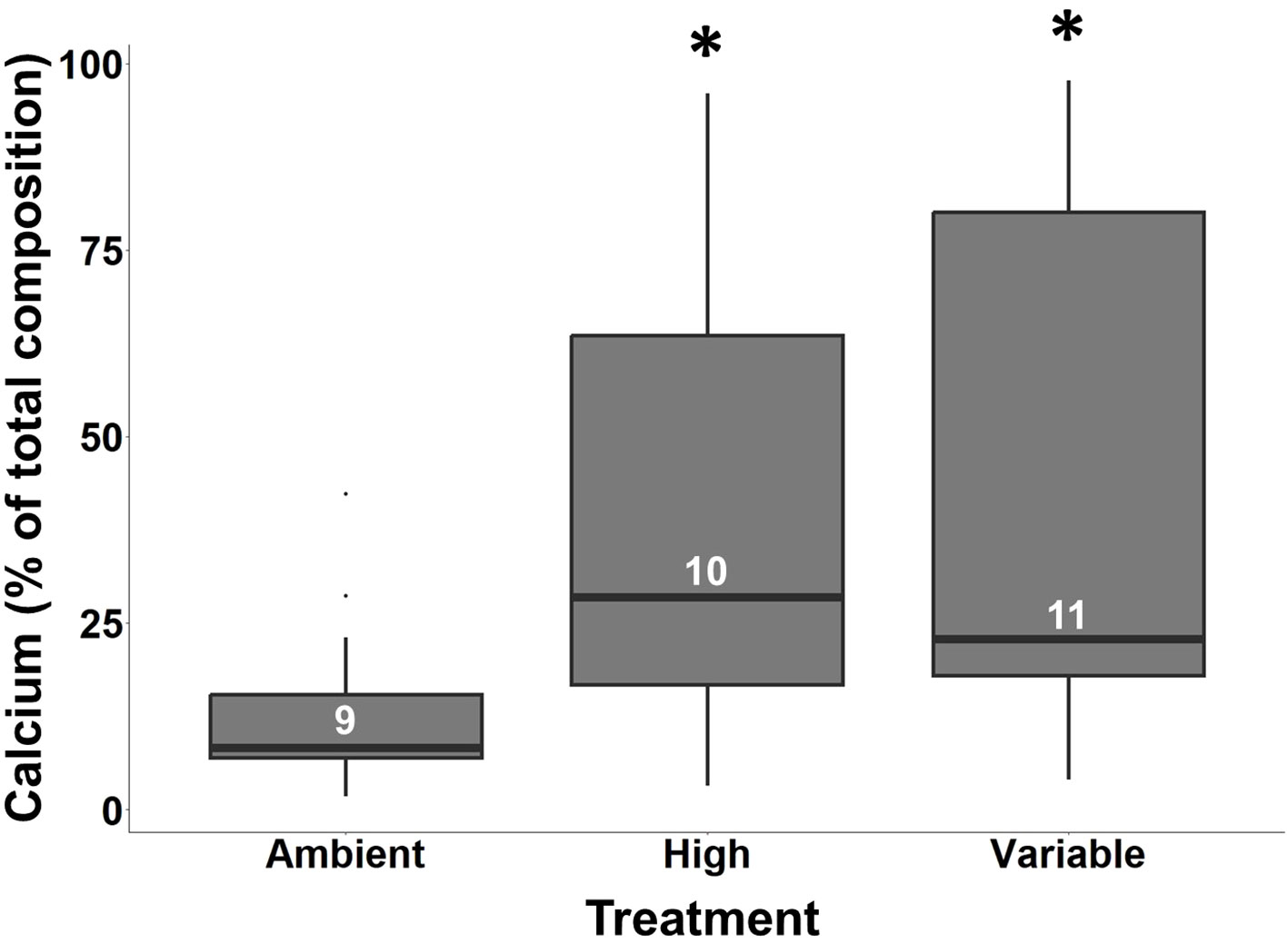

X-ray spectroscopy captured a diverse elemental constituency of larval S. patula over time for both shell points (Supplementary Table 2; Figure 2). Overall, there were no significant differences in the presence of chloride, magnesium, sulfur, or silica as a result of time or treatment (Kruskal Wallis, p > 0.05). There were significant differences in the amount of sulfur and silica present between Point 1 and Point 2 on a shell with significantly more silica present at Point 2 (Kruskal Wallis, p < 0.001), and significantly more sulfur at Point 1, overall (Kruskall Wallis, p < 0.001). The contribution of calcium varied significantly between the treatments over time with insignificant differences in calcium levels between treatments at 7, 14 and 21 DPF (Kruskal Wallis, p > 0.05). However, S. patula in the elevated and variable pCO2 treatments had significantly more calcium present than individuals from the ambient treatment at 28 DPF (Figure 5, Wilcoxon, p = 0.001, p < 0.001, respectively). There was no significant difference in calcium presence between Point 1 and Point 2 (Kruskal Wallis, p = 0.355).

Figure 5 Boxplots showing the contribution of calcium (% of total composition) to shell composition at 28 DPF. Asterisks denote a significant difference from the ambient pCO2 treatment. Sample size is at the level of individual and is denoted by the white numbers present in each bar. Note: Point 1 and Point 2 have been pooled for this analysis.

3.4 Shell development

Photographic assemblages of all sample individuals from days 7, 14, 21 and 28 were generated (Supplementary Figures 2-5). At 14 DPF, all individuals across treatments had a concretion as the main shell structure (Figure 3A). By 21 DPF, shells in both the ambient and variable treatments were captured in transition from a concretion to a fully mineralized shell (Figure 3B), while several individuals from the high pCO2 treatment possessed fully mineralized shells (Figure 3C). These individuals had completely lost the flexible, globular concretion, and resembled a shell similar to Laternula elliptica and other more evolutionarily derived bivalves (Watson et al., 2009; Bylenga et al., 2017). By day 28 (DPF), the variable treatment also contained individuals that had transitioned to a fully mineralized shell. By the conclusion of the experiment, none of the ambient shells had reached the fully calcified state (Supplementary Figure 5).

There was a significant difference in calcium contribution to overall shell composition between the three different developmental groups (Figure 6, Kruskal Wallis, p < 0.001). S. patula individuals in transition and those that were considered fully calcified had significantly more calcium present than those individuals still in the concretion phase (Wilcoxon, p < 0.001). Additionally, calcified individuals had significantly more calcium than transitioning individuals (Wilcoxon, p = 0.036).

Figure 6 The amount of calcium (% of total composition) present across the different stages of shell development. Asterisks denote a significant difference from the concretion shell developmental stage. Error bars denote standard error. White numbers present in each bar represent the number of individuals in that shell developmental stage across all experimental treatments at all-time points.

3.5 Minerology

Raman Spectroscopy identified two calcium carbonate polymorphs present in larval S. patula individuals (Figure 7). At 7 DPF, three S. patula individuals were detected using Raman spectroscopy (N = 3), one individual from each treatment. All detected individuals exhibited Raman spectra consistent with amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC), characterized by the presence of disordered and broad peaks at the Raman shift location of 1080 cm-1 (Wehrmeister et al., 2011), in addition to the visually ropey topology of the shell. At 21 DPF, three S. patula individuals (N = 3) were detectable using Raman spectroscopy, two individuals from the high pCO2 treatment and one from the ambient pCO2 treatment. A Raman peak consistent with vaterite (Jacob et al., 2008) was detected in a high treatment individual, while the other high treatment individual and the ambient individual still exhibited ACC. At 28 DPF, four S. patula individuals were detected (N = 4), two from the high pCO2 treatment and two from the variable pCO2 treatment. Both individuals from the high treatment produced Raman peaks identified as vaterite, and one individual from the variable treatment indicated vaterite as the polymorph present, while the other variable individual was composed of ACC. The combination of visual identification of ACC and vaterite from SEM micrographs, and the limited Raman spectroscopy data collectively support our assessment that vaterite is the CaCO3 polymorph present in S. patula shells during their advanced larval stage. The X-ray diffraction analysis of adult, LCI S. patula (N = 5) revealed aragonite as the CaCO3 polymorph present in all individuals. Despite the limited number of samples analyzed from each treatment, our results suggest that LCI S. patula undergo a CaCO3 transition from ACC to vaterite to aragonite during shell development.

Figure 7 Raman Spectroscopy results for S. patula. Each line represents an individual from that specific treatment. (A) Raman spectra for individuals at 7 DPF. The shape of the spectra indicates the presence of ACC. (B) Raman spectra for individuals at 21 DPF. The shape of the spectra indicates vaterite in the topmost high pCO2 individual, and ACC in the other two individuals. (C) Raman spectra for individuals at 28 DPF. The spectra indicate the presence of vaterite in both high pCO2 individuals, vaterite in one of the two variable pCO2 individuals, and ACC in the additional variable pCO2 individual.

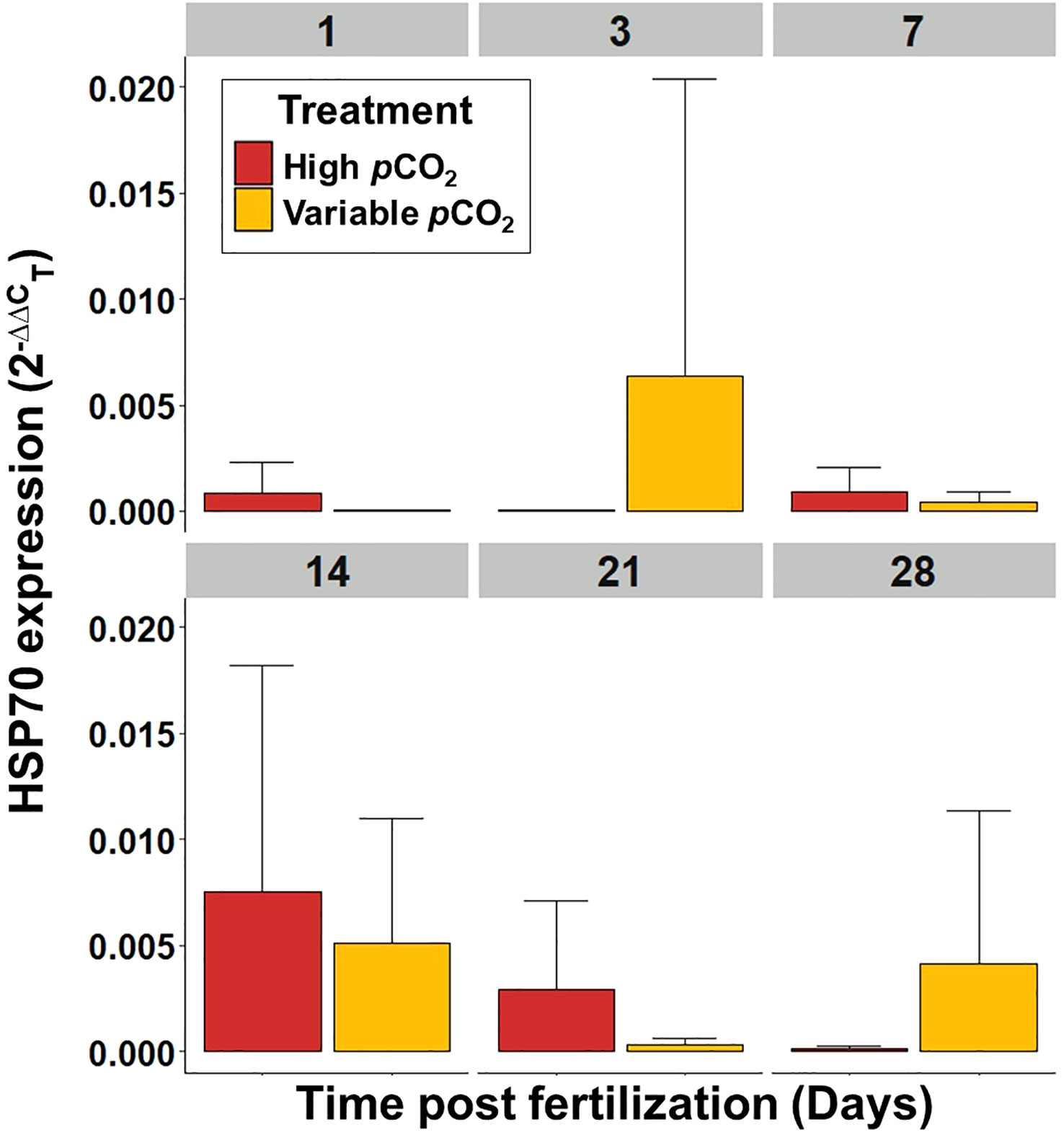

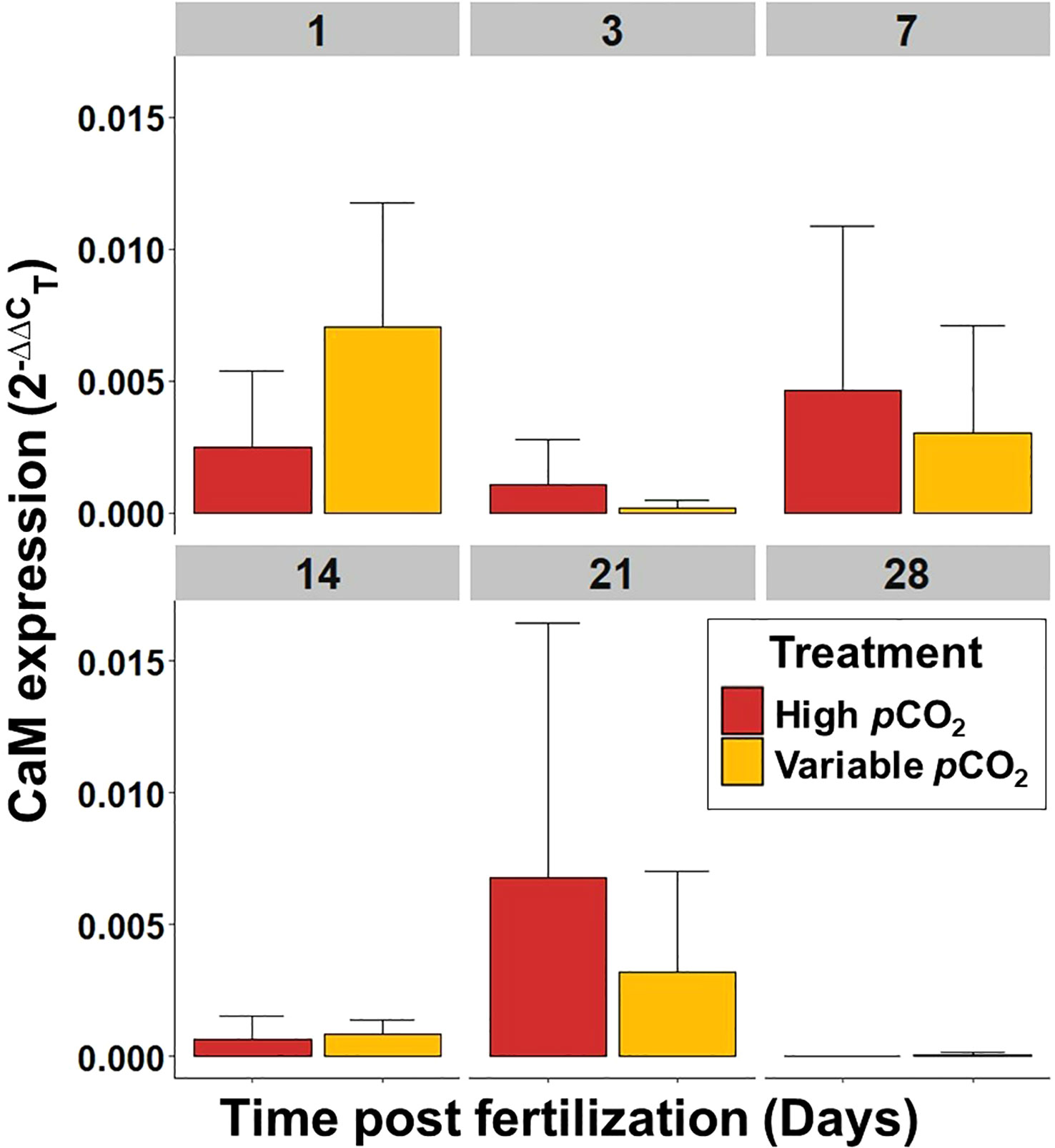

3.6 Gene expression

Gene expression (ΔCT) for the elevated and variable pCO2 treatments was normalized against the ambient pCO2 treatment gene expression (ΔCT, Supplementary Figure 6) to generate the 2(-ΔΔCT) value for HSP70 and CaM. Overall, there was no significant effect of elevated or variable pCO2 on HSP70 or CaM expression in larval S. patula at any point during the experiment (p ≥ 0.05; see Supplementary Table 3 for all p-values). There was, however, a difference in overall HSP70 expression over time (Kruskal Wallis, p = 0.005), with expression at 14 DPF being significantly higher than all other time points (Wilcoxon, p ≤ 0.049, Figure 8). There was also a difference in overall CaM expression over time (Kruskal Wallis, p = 0.005), with expression at 28 DPF being significantly lower than all other time points (Wilcoxon, p ≤ 0.045, Figure 9).

Figure 8 Mean HSP70 expression, per embryo or larvae, of S. patula through time. Error bars denote standard error. Sample size (n = 5) is representative of culture vessel for each treatment.

Figure 9 Mean CaM expression, per embryo or larvae, of S. patula through time. Error bars denote standard error. Sample size (n = 5) is representative of culture vessel for each treatment.

4 Discussion

While the Raman spectroscopy results were limited, we believe that ACC and vaterite are the CaCO3 polymorphs present during the biomineralogical transitions of larval S. patula. Firstly, the persistence of ACC and vaterite was evident in the visual assessment of SEM micrographs. Secondly, the diverse elemental constituency of larval S. patula shells is in line with known compositional diversity seen in both ACC and vaterite (Nebel et al., 2008; Soldati et al., 2008). Finally, the Raman spectra presented are consistent with known ACC (Wehrmeister et al., 2011) and vaterite (Jacob et al., 2008), with potential shift of the vateritic dual peak due to alternative mineral inclusion (as seen in the compositional data, Seknazi et al., 2019). ACC was the polymorph present in larval S. patula concretions, while vaterite was evident in fully calcified larval S. patula shells. Aragonite was the final CaCO3 polymorph present in adult S. patula. This biomineralogical journey, from ACC to vaterite to aragonite, while relatively unique, is not necessarily unprecedented (Hasse et al., 2000). However, it does raise some concerns regarding the sensitivity to dissolution of S. patula under future OA conditions as ACC, vaterite and aragonite represent three of the most soluble polymorphs of biogenic CaCO3 (Gal et al., 1996).

ACC is a known precursor for other polymorphs of CaCO3; however, ACC typically only persists for several hours (Raz et al., 2003; Politi et al., 2008), likely due to its relatively unstable structure (Weiner et al., 2003). Unfortunately, there are a dearth of studies examining the direct effects of OA on organisms that possess ACC as a polymorphic precursor to other forms of calcium carbonate. Previous research on Mytilus edulis suggests that ACC production is increased under future OA conditions as a shell repair mechanism (Fitzer et al., 2016); however, the implications of persistent use of ACC by larval bivalves has yet to be investigated. Given established knowledge regarding the thermodynamics of ACC (Gal et al., 1996), it is possible to infer that prolonged use of this form of CaCO3 increases a biocalcifier’s vulnerability to dissolution under future OA conditions.

While ACC is a known precursor of aragonite (Weiss et al., 2002), and aragonite is a common CaCO3 polymorph found in marine bivalves (Sonak, 2017), biogenic vaterite is not well understood. Biogenic vaterite has been found in fish otoliths (McConnell et al., 2019), pearls (Jacob et al., 2008), juvenile freshwater snail shells (Hasse et al., 2000), bird egg shells (Portugal et al., 2018), and even in a species of alpine plant (Wightman et al., 2018). However, in light of vaterite’s less organized crystalline structure, there is uncertainty regarding whether vaterite exists as a typical, transitional CaCO3 polymorph, or as result of stress-induced, deficient mineralization from ACC to calcite (Hasse et al., 2000; Melancon et al., 2005). Moreover, if the presence of biogenic vaterite is not a result of malformation, its benefit over another, more stable polymorph of CaCO3 is unknown (Portugal et al., 2018), and should be further investigated. Unfortunately, there were no ambient individuals present in the 28 DPF Raman spectroscopy sample from this study, so we are unable to make a direct comparison to the presence of vaterite in S. patula reared under ambient pCO2 conditions to those exposed to elevated and variable pCO2. Meaning, we cannot definitively state that the use of vaterite as a precursor phase is common across all LCI S. patula, or if it is present due to maladaptive mineralization.

While the transition from vaterite to aragonite constitutes a reduction of the potential solubility of S. patula shells, it is unclear (based on the scope of this study) at what point during development this transition occurs, and therefore how long this more vulnerable vaterite phase persists. Further, it is important to note that while less soluble than vaterite, aragonite is still a more soluble polymorph of CaCO3 and is also vulnerable to dissolution under OA (Gal et al., 1996). Exposure to future OA conditions has resulted in external, aragonitic shell dissolution in various marine mollusks (Green et al., 2004; Watson et al., 2009; Busch et al., 2014), as well as increased dissolution of the aragonitic, nacreous layer of Mytilus edulis (Melzner et al., 2011). While S. patula may also prove vulnerable to future OA conditions due to dissolution, future research is needed to establish the response of aragonitic individuals.

ACC and vaterite are the two of the most soluble polymorphs of CaCO3 (Gal et al., 1996; Weiner et al., 2003) due to disordered crystallography (Rodriguez-Blanco et al., 2011). ACC is composed of disorganized, scattered molecules so that the overall surface area of an ACC aggregate is larger than a more ordered polymorph of CaCO3, with more interstitial space between molecules (Weiner et al., 2003). Vaterite is similar in nature to ACC in that it has a more disordered molecular structure than other CaCO3 polymorphs, but the overall structure is tighter (less inter-molecular space) than that of ACC (Christy, 2017). The increased porosity of ACC and vaterite polymorphs permits greater solvent access along the crystalline interface (Ogino et al., 1987), which is one of the mechanism that increases the overall solubility of these polymorphs.

In addition to the increased vulnerability to dissolution, the greater interstitial space present in these polymorphs allows for the intrusion of organic molecules within the CaCO3 amalgamation (Addadi et al., 2003), leading to the potential for increased elemental diversity within overall CaCO3 composition in ACC aggregates, which is supported by the compositional data from the concretion stage of S. patula presented here (Figure 2). The tighter lamination of CaCO3 molecules in vaterite results in a reduction of organic molecule intrusion compared to ACC, and therefore an increase in the relative calcium presence. However, the interstitial space present in vaterite, while less than ACC, still allows for the intrusion of organic molecules within the CaCO3 crystalline matrix (Fernández-Díaz et al., 2010). This reduction in organic molecule intrusion due to tighter crystal lamination between ACC and vaterite is further supported by the significant difference in the relative calcium contribution to overall composition between concretion-stage individuals (using ACC) and fully calcified individuals in our study (using vaterite, Figure 6).

Although we expected alterations of CaM expression due to the observed treatment-related differences in the timing of biomineralogical transition given the prior expression of CaM in shell building and preparation for settlement (Li et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2012), there was no significant effect of elevated or variable pCO2 exposure on CaM expression. This further contradicts previous studies which have shown upregulation under OA conditions, likely intended to maintain shell calcification under acidic conditions (Dineshram et al., 2013; Dineshram et al., 2015). It is possible that the lack of upregulation of CaM was due to the concretion development technique used by S. patula, and the subsequent delay in overall calcification. A prolonged exposure beyond our experimental duration may have resulted in CaM upregulation as described in Dineshram et al. (2013); Dineshram et al., (2015). There was no significant alteration to HSP70 expression as a result of exposure to elevated or variable pCO2. This contradicts results described in Cummings et al. (2011) which reported HSP70 upregulation in Laternula elliptica under OA conditions, and Lardies et al. (2014), which identified similar upregulation of HSP70 family genes in juvenile Concholepas concholepas. As with CaM, perhaps HSP70 expression was not significantly upregulated in the present study as stress effects due to exposure to acidic conditions were not observed within this experimental timeframe. It should be noted that individuals were sampled from the variable pCO2 treatment during the day, when pCO2 was low. Subsequently, the HSP70 and CaM expression results may not fully represent the spectrum of gene expression experienced by S. patula in the variable treatment, as was documented by Podrabsky and Somero (2004) where gene expression varied with daily, cyclical temperature fluctuations.

While this study was unable to capture any potential dissolution or malformation as a result of ACC and vaterite presence during initial shell formation, or altered gene expression, individuals who were reared under elevated and variable pCO2 did appear to transition from ACC to vaterite at an accelerated rate. Furthermore, this relationship between shell calcification and exposure to future OA conditions appears to be directly correlated to the time spent to elevated pCO2. Larvae reared in consistently high pCO2 conditions first exhibited fully calcified individuals at 21 DPF (although not all individuals had calcified), whereas larvae exposed to intermittently elevated pCO2 (the variable treatment) demonstrated individuals with complete calcification at 28 DPF. Conversely, not a single individual reared under ambient pCO2 conditions displayed complete calcification at any time during the experiment.

The elevated calcium presence in transitional shells and fully calcified shells, compared to the calcium levels found in a concretion, also suggests an increase in the developmental rate of S. patula larvae exposed to consistent and intermittently high pCO2. Calcium contribution to overall shell composition was significantly higher in these two treatments compared to the ambient shells at 28 DPF (Figure 5). While calcification had begun at 21 DPF, the maximum mean percentage of calcium present was only 41% at 28 DPF. An analysis of adult LCI S. patula composition showed a mean calcium contribution of 96.2% ± 2.31% (N = 5, Alcantar & Severin2, unpublished data), indicating that by 28 DPF, the majority of calcification is yet to occur.

Contrary to the results of this study, previous research looking at the response of larval mollusks under OA conditions has typically produced an overall decrease in developmental rate. A study examining the impact of OA on the early development of abalones Haliotis diversicolor, and Haliotis discus hannai demonstrated that both species experienced a decrease in developmental rate under elevated pCO2 conditions, and that this was directly correlated to the concentration of pCO2 experienced (Guo et al., 2015). The abalone, Haliotis tuberculata, presented a similar pattern to Guo et al. (2015), with the timing of different developmental stages being pH dependent (Wessel et al., 2018). Bivalves have also responded to elevated pCO2 exposure by altering normal developmental timelines. Both Mercenaria mercenaria and Argopecten irradians exhibited decreasing developmental rates with increasing pCO2 conditions across veliger, pediveliger and metamorphosed transitions (Talmage and Gobler, 2010).

Given the results from previous molluscan studies, the question arises as to what an accelerated developmental timeline means for larval S. patula. Past research on the fish species Lates calcarifer has revealed that exposure to future OA conditions results in an increase in developmental rate (Rossi et al., 2015). However, this acceleration of development led to negative timing mismatches of vital settlement cues in larval individuals (Rossi et al., 2015). In light of the negative consequences associated with accelerated development highlighted by Rossi et al. (2015), it is vital to consider the implications of accelerated shell development in LCI S. patula, as the energy needed to maintain an accelerated development rate is likely to come at a metabolic cost.

Bivalves have displayed varied metabolic responses to future OA conditions (Waldbusser et al., 2015a; Kelley and Lunden, 2017; Bacus and Kelley, 2023), mandating the need for further metabolic examination of S. patula under elevated pCO2 conditions. However, if larval S. patula are deviating from the normal shell developmental strategy (like that seen in the ambient pCO2 treatment group), and do not demonstrate an upregulation in overall metabolism, like 58% of other bivalve species (Kelley and Lunden, 2017), larvae may need to divert the energy that would otherwise be devoted to growth, or other important developmental processes. In fact, although it was not statistically significant, the size data of S. patula 28 DPF demonstrates that despite being further along in the calcification process, individuals in the high and variable pCO2 treatments were smaller overall than individuals from ambient pCO2 conditions (Figure 4). It is possible that the cost of an earlier mineralogical transition from ACC to vaterite, with a faster increase in overall calcium contribution (possibly at the expense of overall size), may have been more pronounced had the experiment been carried out longer, or had the pH been reduced by more than 0.4 units, as noted in Waldbusser et al. (2015b). Additional research is needed to determine if accelerated calcification comes at a cost to overall size of LCI S. patula, a possibility that has substantial implications for commercial, recreational and subsistence harvest.

There was an expectation that variable pCO2 treatment larvae would exhibit fewer negative effects than the static, elevated pCO2 treatment larvae given the variable carbonate chemistry conditions experienced by LCI S. patula, however, our results did not bear this out. With respect to the CaCO3 polymorphs present and shell development, the variable pCO2 treatment larvae were somewhat aligned the elevated pCO2 treatment larvae, although temporally delayed, with both ACC and vaterite present as CaCO3 polymorphs, and shell development appearing to be accelerated compared to the ambient pCO2 S. patula. The relationship between variability and growth is not straightforward. Although not statistically significant, S. patula reared under variable pCO2 conditions were larger overall than both ambient and elevated pCO2 S. patula at 7 and 14 DPF. However, at both 21 and 28 DPF, variable pCO2 individuals were smaller overall than both ambient pCO2 treatment S. patula and elevated pCO2 treatment S. patula. While these results do not provide a clear understanding of S. patula from LCI, and future research is needed to explore potential population specific responses to variable carbonate chemistry conditions, these results do highlight the importance of including variable conditions for relevant species.

5 Conclusions

This study suggests that one possible response of LCI S. patula to future OA conditions is an increase in shell developmental rate. These rates are proportional to the amount of time exposed to elevated pCO2, with high treatment individuals fully calcifying first, and individuals from the variable treatment following. Furthermore, this study has characterized the calcium carbonate polymorphism of S. patula for the first time, identifying a potential OA vulnerability present in the form of vaterite during the initial calcification phase.

While this study did not find any other impacts of elevated pCO2 on LCI S. patula, the alteration of shell developmental rate was contradictory to that documented in previous mollusca studies (Talmage and Gobler, 2010; Guo et al., 2015; Wessel et al., 2018). This deviation of developmental rate could prove detrimental to overall S. patula fitness if individuals divert energy from other processes to increase their developmental rate. Moreover, alterations to developmental rate could result in detrimental timing mismatches of vital processes during S. patula life-history stages (Rossi et al., 2015).

Given that S. patula’s biomineralogical response to elevated pCO2 contradicts the current research regarding mollusk development under OA conditions, it is evident that there is still a lot of work to be done to lay the baseline of knowledge about the response of early life-history stage bivalves to future OA conditions. Furthermore, the presence of vaterite as a transitional calcium carbonate polymorph, or as an artifact of mineral malformation remains unresolved. Overall, this study highlights the need for multivariate, species and population specific experimental evaluations to be conducted in order to better inform bivalve management decisions, and mariculture practices in a future acidified ocean.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The requirement of ethical approval was waived by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Alaska Fairbanks for the studies involving animals because current U.S. regulations do not apply to work with invertebrate species. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

MA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JH: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JR: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The facilities, water chemistry analysis, and supplies were provided by the Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute. Graduate student funding was provided for MA by the Alaska EPSCoR Fire and Ice Project, NSF award number OIA-1757348, and the Rasmuson Fisheries Research Center. Funding for laboratory analysis supplied was provided by the Cooperative Institute for Alaska Research, and funding for the scanning electron microscopy work was funded by the Robert and Kathleen Byrd award at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to recognize that this study was conducted by researchers living and working on the unceded traditional homelands of the Lower Tanana Dené. Furthermore, this research was conducted on the unceded traditional homelands of the Sugpiaq/Alutiiq people in their community of Qutalleq. The authors are grateful to the staff of the Alutiiq Pride Marine Institute, and the Chugach Regional Resources Commission, as well as Dr. Javier Fochesatto of the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, and Dr. Ken Severin and Nathan Graham of the Advanced Instrumentation Laboratory at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The authors thank Dr. Cale Miller, Shelby Bacus, Josianne Haag and Jonah Jossart of the Kelley lab.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2024.1253702/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ Alcantar, M.W., Hetrick, J., Ramsay, J., and Kelley, A.L. Embryonic and early larval development of the Pacific razor clam (Siliqua patula). Biol. Bull. (in review).

- ^ Alcantar, M.W., and Severin, K. Calcium carbonate polymorphism of Siliqua patula using X-ray Diffraction. (Unpublished).

References

Addadi L., Raz S., Weiner S. (2003). Taking advantage of disorder: Amorphous calcium carbonate and its roles in biomineralization. Adv. Mater. 15, 959–970. doi: 10.1002/adma.200300381

Alaska Department of Fish and Game (2020) Razor Clam Species Profile, Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Available at: https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=razorclam.main (Accessed June 19, 2022).

Alaska Department of Fish and Game (2022) ADF&G, Subsistence, Community Subsistence Information System. Available at: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/sb/CSIS/index.cfm?ADFG=harvInfo.resourceRegionData (Accessed June 9, 2019).

Bacus S., Kelley A. (2023). Effects of ocean acidification and ocean warming on the behavior and physiology of a subarctic, intertidal grazer. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 711, 31–45. doi: 10.3354/meps14308

Bandstra L., Hales B., Takahashi T. (2006). High-frequency measurements of total CO2: Method development and first oceanographic observations. Mar. Chem. 100, 24–38. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2005.10.009

Barton A., Hales B., Waldbusser G. G., Langdon C., Feely R. A. (2012). The Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, shows negative correlation to naturally elevated carbon dioxide levels: Implications for near-term ocean acidification effects. Limnol. Oceanogr. 57, 698–710. doi: 10.4319/lo.2012.57.3.0698

Bowen L., Counihan K. L., Ballachey B., Coletti H., Hollmen T., Pister B., et al. (2020). Monitoring nearshore ecosystem health using Pacific razor clams (Siliqua patula) as an indicator species. PeerJ 8, e8761. doi: 10.7717/peerj.8761

Busch D. S., Maher M., Thibodeau P., McElhany P. (2014). Shell condition and survival of Puget Sound pteropods are impaired by ocean acidification conditions. PloS One 9, e105884. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105884

Bylenga C. H., Cummings V. J., Ryan K. G. (2017). High resolution microscopy reveals significant impacts of ocean acidification and warming on larval shell development in Laternula elliptica. PloS One 12, e0175706. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175706

Carstensen J., Duarte C. M. (2019). Drivers of pH variability in coastal ecosystems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 4020–4029. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b03655

Chen Z.-F., Wang H., Matsumura K., Qian P.-Y. (2012). Expression of Calmodulin and Myosin Light Chain Kinase during Larval Settlement of the Barnacle Balanus amphitrite. PloS One 7, e31337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031337

Christy A. G. (2017). A review of the structures of vaterite: The impossible, the possible, and the likely. Crystal Growth Des. 17, 3567–3578. doi: 10.1021/acs.cgd.7b00481

Cummings V., Hewitt J., Rooyen A. V., Currie K., Beard S., Thrush S., et al. (2011). Ocean acidification at high latitudes: potential effects on functioning of the Antarctic bivalve Laternula elliptica. PloS One 6, e16069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016069

Dickson A. G., Sabine C. L., Christian J. R., Bargeron C. P., North Pacific Marine Science Organization (2007). Guide to best practices for ocean CO2 measurements (Sidney, BC: North Pacific Marine Science Organization).

Dineshram R., Q. Q., Sharma R., Chandramouli K., Yalamanchili H. K., Chu I., et al. (2015). Comparative and quantitative proteomics reveal the adaptive strategies of oyster larvae to ocean acidification. Proteomics 15, 4120–4134. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201500198

Dineshram R., Thiyagarajan V., Lane A., Ziniu Y., Xiao S., Leung P. T. Y. (2013). Elevated CO2 alters larval proteome and its phosphorylation status in the commercial oyster, Crassostrea hongkongensis. Mar. Biol. 160, 2189–2205. doi: 10.1007/s00227-013-2176-x

Eyster L. S. (1986). Shell inorganic composition and onset of shell mineralization during bivalve and gastropod embryogenesis. Biol. Bull. 170, 211–231. doi: 10.2307/1541804

Fabry V. J., Seibel B. A., Feely R. A., Orr J. C. (2008). Impacts of ocean acidification on marine fauna and ecosystem processes. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 65, 414–432. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsn048

Fangue N. A., O’Donnell M. J., Sewell M. A., Matson P. G., MacPherson A. C., Hofmann G. E. (2010). A laboratory-based, experimental system for the study of ocean acidification effects on marine invertebrate larvae: CO2 controlled larval culture system. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 8, 441–452. doi: 10.4319/lom.2010.8.441

Feely R. A., Fabry V. J., Guinotte J. M. (2008). Ocean acidification of the North Pacific Ocean. PICES Press 16, 22–26.

Fernández-Díaz L., Fernández-González Á., Prieto M. (2010). The role of sulfate groups in controlling CaCO3 polymorphism. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 74, 6064–6076. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2010.08.010

Fitzer S. C., Chung P., Maccherozzi F., Dhesi S. S., Kamenos N. A., Phoenix V. R., et al. (2016). Biomineral shell formation under ocean acidification: a shift from order to chaos. Sci. Rep. 6, 21076. doi: 10.1038/srep21076

Fitzer S. C., Gabarda S. T., Daly L., Hughes B., Dove M., O’Connor W., et al. (2018). Coastal acidification impacts on shell mineral structure of bivalve mollusks. Ecol. Evol. 8, 8973–8984. doi: 10.1002/ece3.4416

Fochesatto J., Sloan J. (2009). Signal processing of multicomponent raman spectra of particulate matter. IJHSES 18, 277–294. doi: 10.1142/9789812835925_0004

Fretter V., Pilkington M. C. (1971). The larval shell of some prosobranch gastropods. J. Mar. Biolog. Assoc. U.K. 51, 49–62. doi: 10.1017/S0025315400006445

Frieder C. A., Gonzalez J. P., Bockmon E. E., Navarro M. O., Levin L. A. (2014). Can variable pH and low oxygen moderate ocean acidification outcomes for mussel larvae? Glob. Change Biol. 20, 754–764. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12485

Gal J., Bollinger J., Tolosa H., Gache N. (1996). Calcium carbonate solubility: a reappraisal of scale formation and inhibition. Talanta 43, 1497–1509. doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(96)01925-X

Green M. A., Jones M. E., Boudreau C. L., Moore R. L., Westman B. A. (2004). Dissolution mortality of juvenile bivalves in coastal marine deposits. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49, 727–734. doi: 10.4319/lo.2004.49.3.0727

Green M. A., Waldbusser G. G., Reilly S. L., Emerson K., O’Donnell S. (2009). Death by dissolution: Sediment saturation state as a mortality factor for juvenile bivalves. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 1037–1047. doi: 10.4319/lo.2009.54.4.1037

Guo X., Huang M., Pu F., You W., Ke C. (2015). Effects of ocean acidification caused by rising CO2 on the early development of three mollusks. Aquat. Biol. 23, 147–157. doi: 10.3354/ab00615

Hales B., Chipman D., Takahashi T. (2004). High-frequency measurement of partial pressure and total concentration of carbon dioxide in seawater using microporous hydrophobic membrane contactors: High-frequency CO2 measurement. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2, 356–364. doi: 10.4319/lom.2004.2.356

Hasse B., Ehrenberg H., Marxen J. C., Becker W., Epple M. (2000). Calcium carbonate modifications in the mineralized shell of the freshwater snail biomphalaria glabrata. Chem. Eur. J. 6, 3679–3685. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20001016)6:20<3679::AID-CHEM3679>3.0.CO;2-#

Hinzmann M. F., Lopes-Lima M., Bobos I., Ferreira J., Domingues B., MaChado J. (2015). Morphological and chemical characterization of mineral concretions in the freshwater bivalve Anodonta cygnea (Unionidae). J. Morphol 276, 65–76. doi: 10.1002/jmor.20320

Jacob D. E., Soldati A. L., Wirth R., Huth J., Wehrmeister U., Hofmeister W. (2008). Nanostructure, composition and mechanisms of bivalve shell growth. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 72, 5401–5415. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2008.08.019

Kapsenberg L., Cyronak T. (2019). Ocean acidification refugia in variable environments. Glob. Chang. Biol. 25, 3201–3214. doi: 10.1111/gcb.14730

Kapsenberg L., Miglioli A., Bitter M. C., Tambutté E., Dumollard R., Gattuso J.-P. (2018). Ocean pH fluctuations affect mussel larvae at key developmental transitions. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 285, 20182381. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2018.2381

Karl T. R., Trenberth K. E. (2003). Modern global climate change. Science 302, 1719–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1090228

Kelley A. L., Lunden J. (2017). Meta-analysis identifies metabolic sensitivities to ocean acidification. AIMS Environ. Sci. 4, 709–729. doi: 10.3934/environsci.2017.5.709

Kroeker K. J., Kordas R. L., Crim R., Hendriks I. E., Ramajo L., Singh G. S., et al. (2013). Impacts of ocean acidification on marine organisms: quantifying sensitivities and interaction with warming. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 1884–1896. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12179

Lardies M. A., Arias M. B., Poupin M. J., Manríquez P. H., Torres R., Vargas C. A., et al. (2014). Differential response to ocean acidification in physiological traits of Concholepas concholepas populations. J. Sea Res. 90, 127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2014.03.010

Leung J. Y. S., Russell B. D., Connell S. D. (2017). Minerological plasticity acts as a compensatory mechanism to the impacts of ocean acidification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 2652–2659. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b04709

Li S., Xie L., Zhang C., Zhang Y., Gu M., Zhang R. (2004). Cloning and expression of a pivotal calcium metabolism regulator: calmodulin involved in shell formation from pearl oyster (Pinctada fucata). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B: Biochem. Mol. Biol. 138, 235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2004.03.012

Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2–ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

McConnell C. J., Atkinson S., Oxman D., Peter A. H. (2019). Is blood cortisol or vateritic otolith composition associated with natal dispersal or reproductive performance on the spawning grounds of straying and homing hatchery-produced chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) in Southeast Alaska? Biol. Open 8, bio.042853. doi: 10.1242/bio.042853

Melancon S., Fryer B. J., Ludsin S. A., Gagnon J. E., Yang Z. (2005). Effects of crystal structure on the uptake of metals by lake trout (Salvelinus namaycush) otoliths. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 62, 2609–2619. doi: 10.1139/f05-161

Melzner F., Stange P., Trübenbach K., Thomsen J., Casties I., Panknin U., et al. (2011). Food supply and seawater pCO2 impact calcification and internal shell dissolution in the blue mussel Mytilus edulis. PloS One 6, e24223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024223

Miller C. A., Kelley A. L. (2021). Seasonality and biological forcing modify the diel frequency of nearshore pH extremes in a subarctic Alaskan estuary. Limnol. Oceanogr. 66, 1475–1491. doi: 10.1002/lno.11698

Nebel H., Neumann M., Mayer C., Epple M. (2008). On the structure of amorphous calcium carbonate—a detailed study by solid-state NMR spectroscopy. Inorg. Chem. 47, 7874–7879. doi: 10.1021/ic8007409

Ogino T., Suzuki T., Sawada K. (1987). The formation and transformation mechanism of calcium carbonate in water. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 51, 2757–2767. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(87)90155-4

Olsen L. (2015). Cause of razor clam decline remains mystery. Available at: https://www.homernews.com/news/cause-of-razor-clam-decline-remains-mystery/ (Accessed June 9, 2019).

Orr J. C., Fabry V. J., Aumont O., Bopp L., Doney S. C., Feely R. A., et al. (2005). Anthropogenic ocean acidification over the twenty-first century and its impact on calcifying organisms. Nature 437, 681. doi: 10.1038/nature04095

Peng C., Zhao X., Liu S., Shi W., Han Y., Guo C., et al. (2017). Ocean acidification alters the burrowing behaviour, Ca2+/Mg2+-ATPase activity, metabolism, and gene expression of a bivalve species, Sinonovacula constricta. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 575, 107–117. doi: 10.3354/meps12224

Podrabsky J. E., Somero G. N. (2004). Changes in gene expression associated with acclimation to constant temperatures and fluctuating daily temperatures in an annual killifish Austrofundulus limnaeus. J. Exp. Biol. 207, 2237–2254. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01016

Politi Y., Metzler R. A., Abrecht M., Gilbert B., Wilt F. H., Sagi I., et al. (2008). Transformation mechanism of amorphous calcium carbonate into calcite in the sea urchin larval spicule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 17362–17366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806604105

Poole A. Z., Kitchen S. A., Weis V. M. (2016). The role of complement in cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis and immune challenge in the sea anemone aiptasia pallida. Front. Microbiol. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00519

Portugal S. J., Bowen J., Riehl C. (2018). A rare mineral, vaterite, acts as a shock absorber in the eggshell of a communally nesting bird. Ibis 160, 173–178. doi: 10.1111/ibi.12527

Raz S., Hamilton P. C., Wilt F. H., Weiner S., Addadi L. (2003). The transient phase of amorphous calcium carbonate in sea urchin larval spicules: the involvement of proteins and magnesium ions in its formation and stabilization. Adv. Funct. Mater. 13, 480–486. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200304285

Rodriguez-Blanco J. D., Shaw S., Benning L. G. (2011). The kinetics and mechanisms of amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) crystallization to calcite, via vaterite. Nanoscale 3, 265–271. doi: 10.1039/C0NR00589D

Rossi T., Nagelkerken I., Simpson S. D., Pistevos J. C. A., Watson S.-A., Merillet L., et al. (2015). Ocean acidification boosts larval fish development but reduces the window of opportunity for successful settlement. Proc. R. Soc B. 282, 20151954. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1954

Sabine C. L., Feely R. A., Gruber N., Key R. M., Lee K., Bullister J. L., et al. (2004). The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2. Science 305, 367–371. doi: 10.1126/science.1097403

Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., et al. (2012). Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019

Seknazi E., Mijowska S., Polishchuk I., Pokroy B. (2019). Incorporation of organic and inorganic impurities into the lattice of metastable vaterite. Inorg. Chem. Front. 6, 2696–2703. doi: 10.1039/C9QI00849G

Sewell M. A., Millar R. B., Yu P. C., Kapsenberg L., Hofmann, G E. (2014). Ocean acidification and fertilization in the antarctic sea urchin sterechinus neumayeri: the importance of polyspermy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 713–722. doi: 10.1021/es402815s

Soldati A. L., Jacob D. E., Wehrmeister U., Hofmeister W. (2008). Structural characterization and chemical composition of aragonite and vaterite in freshwater cultured pearls. Mineral. mag. 72, 579–592. doi: 10.1180/minmag.2008.072.2.579

Sonak S. M. (2017). Marine Shells of Goa (Cham: Springer International Publishing). doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-55099-2

Southcentral Region Division of Sport Fish (2017). Cook inlet razor clams. (Anchorage, AK: Alaska Department of Fish and Game).

Stocker T. F., Qin D., Plattner G. -K., Tignor M. M. B., Allen S. K., Boschung J., et al (2013). Climate Change 2013 The Physical Science Basis. (Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press).

Talmage S. C., Gobler C. J. (2010). Effects of past, present, and future ocean carbon dioxide concentrations on the growth and survival of larval shellfish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 17246–17251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913804107

The R Development Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Waldbusser G. G., Hales B., Langdon C. J., Haley B. A., Schrader P., Brunner E. L., et al. (2015a). Ocean acidification has multiple modes of action on bivalve larvae. PloS One 10, e0128376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128376

Waldbusser G. G., Hales B., Langdon C. J., Haley B. A., Schrader P., Brunner E. L., et al. (2015b). Saturation-state sensitivity of marine bivalve larvae to ocean acidification. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 273–280. doi: 10.1038/nclimate2479

Wang Q., Cao R., Ning X., You L., Mu C., Wang C., et al. (2016). Effects of ocean acidification on immune responses of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 49, 24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2015.12.025

Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (2010) Razor Clamming in Washington State. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20100806022545/http://wdfw.wa.gov/fish/shelfish/razorclm/razorclm.htm (Accessed June 2, 2020).

Watson S.-A., Southgate P. C., Tyler P. A., Peck L. S. (2009). Early larval development of the Sydney Rock oyster Saccostrea glomerata under near-future predictions of CO2-driven ocean acidification. J. Shellfish Res. 28, 431–437. doi: 10.2983/035.028.0302

Wehrmeister U., Jacob D. E., Soldati A. L., Loges N., Häger T., Hofmeister W. (2011). Amorphous, nanocrystalline and crystalline calcium carbonates in biological materials. J. Raman Spectrosc. 42, 926–935. doi: 10.1002/jrs.2835

Weiner S., Levi-Kalisman Y., Raz S., Addadi L. (2003). Biologically formed amorphous calcium carbonate. Connect. Tissue Res. 44, 214–218. doi: 10.1080/03008200390181681

Weiss I. M., Tuross N., Addadi L., Weiner S. (2002). Mollusc larval shell formation: amorphous calcium carbonate is a precursor phase for aragonite. J. Exp. Zoology 293, 478–491. doi: 10.1002/jez.90004

Wessel N., Martin S., Badou A., Dubois P., Huchette S., Julia V., et al. (2018). Effect of CO2–induced ocean acidification on the early development and shell mineralization of the European abalone (Haliotis tuberculata). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 508, 52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2018.08.005

Wightman R., Wallis S., Aston P. (2018). Leaf margin organisation and the existence of vaterite-producing hydathodes in the alpine plant Saxifraga scardica. Flora 241, 27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.flora.2018.02.006

Keywords: ocean acidification, vaterite, biomineralogy, Siliqua patula, variability, larval response, amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC)

Citation: Alcantar MW, Hetrick J, Ramsay J and Kelley AL (2024) Examining the impacts of elevated, variable pCO2 on larval Pacific razor clams (Siliqua patula) in Alaska. Front. Mar. Sci. 11:1253702. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1253702

Received: 28 July 2023; Accepted: 02 January 2024;

Published: 24 January 2024.

Edited by:

Sm Sharifuzzaman, University of Chittagong, BangladeshReviewed by:

Pauline Yu, The Evergreen State College, United StatesJuliet Wong, Duke University, United States

Copyright © 2024 Alcantar, Hetrick, Ramsay and Kelley. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marina W. Alcantar, bXdhbGNhbnRhckBhbGFza2EuZWR1

Marina W. Alcantar

Marina W. Alcantar Jeff Hetrick2

Jeff Hetrick2 Jacqueline Ramsay

Jacqueline Ramsay Amanda L. Kelley

Amanda L. Kelley