94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci., 27 June 2023

Sec. Marine Affairs and Policy

Volume 10 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1179624

Social transformation is an emerging trend and a new phenomenon in the cruise industry in the 21st century. Cruise lines encounter stiff competition with many competitors and face sophisticated and unpredictable challenges from the wave of social transformation. Furthermore, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the social transformation phenomena in the industry. This study investigates how social transformation reshapes the cruise industry to discuss the remarkable social and economic changes in the industry. The study builds upon the 4C descriptive framework to suggest how cruise lines take measures to create resilience against the influence affected by social transformation. The study is conducted through 18 semi-structured and in-depth interviews with cruise terminals, travel agencies, logistics, and tourism associations, researchers, cruise lines and passengers, and airlines. The cruise shipping industry structure has fundamentally shifted from supply-driven to demand-driven. The concept of social transformation becomes vital and is a driving force that is more society specific. Findings are drawn as valuable guidelines for cruise lines to scale up in operations and strategies that create social transformation. Cruise lines can also maintain sustainable development and resilient recovery post-COVID-19

A cruise is “any fare-paying voyage for leisure and pleasure onboard a passenger vessel whose primary objective is the accommodation of guests, normally visiting different destinations with flexible routes” (Sun et al., 2019b, p. 5056). In other words, cruise lines provide a means of passenger transport for leisure and pleasure voyages. Since the 1920s, cruising has been identified as the preferred way of travel for the world’s social elite (Sun et al., 2019b). The cruise industry is a ship that presents itself as the destination, essentially acting as a floating resort with related facilities (Rodrigue and Notteboom, 2013). The industry boosts the growth of tourists, economic prosperity, social mobility, and the linkage of cities across geographical continents. According to the Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA, 2021), cruise passengers had dramatically increased from 17.8 million in 2009 to 30 million in 2019. Demand for cruise shipping had risen by 68.5%. Most passengers came from the United States of America (USA), China, Germany, the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, Canada, Italy, Spain, France, and Brazil. In 2019, the industry contributed more than 1.8 million jobs and US$154 billion in total output.

Designing new cruise ships now adopt energy-saving technologies, innovations, and environmental conservation to generate a higher comfort level (Parnyakov, 2014). To cope with increasing demand, cruise lines improve cruise ships’ capacity and facilities. Cruise ship design had evolved from classic ships to modern ships and eventually new millennium third-generation ships. In the late 2000s, freedom and genesis classes had become the most expensive and largest cruise ships, with a US$1.24 billion building cost and 5,400 passenger capacity (Network W. C, 2020). Classic ships have smaller swimming pools and promenade decks. Modern ships improve facilities with larger swimming pools, theatres, discos, and casinos and enlarge the number of staterooms with a balcony. Third-generation ships have freshwater swimming pools and new and innovative features such as open-air cinemas, aqua-theatres, rock-climbing walls, and ice skating rinks (Lau and Yip, 2020).

In the past decades, cruise shipping has been extensively studied. Most studies focused on cruise passengers’ behavioral and psychological aspects and transport management and economics (Sun et al., 2019a; Lau and Yip, 2020). Studies on cruise shipping are inclined toward exploring the notion of social transformation from different viewpoints. This confirms that economic ambition needs to be complemented to generate positive social transformation and social values (Jørgensen et al., 2021). Social transformation is a notion closely associated with adaptation and is supporting a theoretical framing for investigating how the cruise industry can highlight the call for competitiveness in a post-COVID-19 era. Limited research, notably from the tourism perspective, investigates how social transformation is adopted in the cruise industry. The notion of transformation is ambiguous and unsettled in theory and practice and needs interdisciplinary and explorative cruise industry research (Hovelsrud et al., 2021). Additionally, the industry is closely integrated with the community. The issues relevant to the community recognizing the benefits of underlying factors for social transformation are crucial (Kunjuraman et al., 2022).

Social transformation can be triggered by the new context in notable contrast with the ordinary surroundings (Reisinger, 2015). The cruise industry is experiencing social transformation created by the effect of financial crises, economic, globalization, global environmental change and pandemic, and technological advancement (Yazir et al., 2020; Choe et al., 2021; Sheller, 2021). This reflects the industry is under “a process of change” (Kunjuraman et al., 2022, p. 3), especially changes in consumers’ behaviors and mix generate the social transformation phenomenon in the industry (Jiao et al., 2021). Young people (Gen Z) are the most influenced by the changes since they are the leading players in social transformation. Thus, social transformation in cruise tourism could create better tourism products (López-González, 2018). Social media fosters the importance of social transformation in the industry. The tourists are willing to share contacts and travel experiences from cruise activities via various social platforms. Tourists perform a strong motivation to explore insights and suggestions from others’ shared experiences to decrease uncertainty and risks (Monaco, 2018; Su et al., 2021). This build-ups tourists’ confidence to cruise again after the pandemic. Cruise lines provide Instagramable cruise travel and onboard smart technologies, such as bracelets, apps, necklaces, and key chains to encourage tourists to share their cruising experience. Social innovation and cultural creatives are identified as an emancipatory process inducing social transformation (Hottola, 2014; Jørgensen et al., 2021). Social transformation become a new phenomenon in the industry in the aftermath of COVID-19 (Chua et al., 2019). Based on these, this study illustrates the notion of social transformation to discuss the notable economic and social changes in the cruise industry. With the effect of social transformation, cruise tourism can be initiated by independent travel, a new context, and activities encouraging self-reflection and contemplation (Hottola, 2014). The study conceptualizes the social transformation process underlying the upcoming cruising experience in the post-pandemic. The study also provides valuable guidelines for cruise lines to scale up in directions, operations, and strategies that create social transformation and promote cruise tourism sustainable for communities.

This study is divided into six sections. Section 1 presents the introduction of the key changes and development of the cruise industry, research background, and objectives. Section 2 presents a literature review on the cruise market, cruise operations in the COVID-19 context, and the social transformation concept. Section 3 presents the research methodology, while Section 4 illustrates the 4C descriptive framework. The conclusion and future research directions are provided in Section 5.

The European cruise market is the second biggest globally (Lau and Yip, 2020). Many Asian passengers choose to cruise to European destinations (CLIA, 2020) to explore fun, relaxation, sustainable tourism, and Western cultural significance (Mondou and Taunay, 2012; Di Vaio et al., 2021b). To the best of the author’s knowledge, limited research studies focused on the Asian tourists cruising experience in the European region. Gen Z and millennials seek transformational and personalized travel experiences in Europe, such as Germany, Italy, Spain, France, Switzerland, the UK, and Ireland (CBI, 2021). Table 1 shows the share of Asian passengers per European cruise destination in the years 2019 and 2020. There is an increasing trend of Asian passengers looking for new cruise products (e.g., river cruises, theme cruises) and luxury experiences in cruise tourism (CBI, 2021).

The outbreak of COVID-19 impacted the cruise industry. All governments decreasing series of travel restrictions during the pandemic led to the number of cruise passengers decreasing sharply in 2020. As a result, 1.35 million European cruise passengers decreased from 7.0 million in 2019 (Watch, 2022).

The European cruise market is divided into the Mediterranean and North Europe. Most cruise operations conducted in the Mediterranean are geared toward serving Asian passengers. Carnival, MSC Cruises, Royal Caribbean Cruises (RCC), and Norwegian Cruise Line (NCL) have a high market in Europe. Carnival operates 3 cruise brands, including Costa, AIDA, and P&O Cruises accounting for approximately 45% of the European cruise market. The leading cruise operators in the Mediterranean and global markets are Costa, MSC, and Celestyal Cruises. In peak season, cruise ships are serviced at full capacities. Ports of call are divided into the large principal ports visited by the largest cruise ships and smaller ports less accessible visited by smaller cruise ships (Lau et al., 2014).

The cruise industry is supported by the dense port system, which enables innovative itineraries within a short-sea distance (Sun et al., 2019a). Fly-cruise tourism is significant in Mediterranean cruising on a round-trip basis, supported by the short-sea distance between the Mediterranean and major cruise ports and between the Mediterranean and small cruising ports. Fly-cruise is a combination of cruise and air trips. The tourists fly from the nearest airport or their permanent place of residence to the port from which the ship departs (Diakomihalis et al., 2016). The market in the Baltic Sea has changed radically due to the war in Ukraine and the closure of the port of St. Petersburg.

The expected development of international tourism is one of the critical factors to consider in changes in the cruise industry in the long term. The industry represents a particular and distinct sector of the shipping industry. Cruise passengers can enjoy different in-port experiences and visit various destinations in one trip (Sun et al., 2021). Familiarity, loyalty, and social influences are the key factors for supporting the growth of cruise tourism (Kawasaki and Lau, 2020).

High-income cruise passengers tend to cruise again. The engagement of high-income passengers influences their repeat behavior and stimulates their friends and family members to engage in a cruise trip. The cruising experience often emphasizes the importance of passengers’ satisfaction and perceptions of subjective well-being (Di Vaio et al., 2021a; Sun et al., 2021). This leads to the cruise market being strongly supported by the high-income group and the young generation in the future.

The World Health Organization (WHO, 2023) reported on 21 February 2023 that there were 757,264,511 confirmed cases and 6,850,594 associated deaths globally at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the initial stage, neither specific vaccines nor particular antiviral treatments could restrain the spread of the virus. Geographic separation and mutation or change of the virus’s genes induce the coronavirus to transform and develop progressively (Lau et al., 2020). There are various types of variants diffusing across regions. The typical ‘variant of interest’ is Alpha (B.1.1.7) in the UK, Beta (B.1.351) in South Africa, Gamma (P.1) in Brazil, Delta (B.1.617.2) in India, and Mu (B.1.621) in Colombia. This occurs in almost all countries crossing six WHO regions including Western Pacific, Africa, Eastern Mediterranean, South-East Asia, Europe, and America (WHO, 2022). WHO addresses that the COVID-19 outbreak “poses a very grave threat for the rest of the world and should be viewed as Public Enemy Number 1”.

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic is considered remarkable across the globe. Various public health strategies have been enforced by the related officials to minimize the virus transmission, for instance, migration to remote operations, isolation of citizens, contact tracing, social distancing, decreased public transportation, temporary shutdown of certain businesses (e.g, restaurants, entertainment facilities, shops, and shopping malls), and restrictions on access to public facilities and services. In particular, some countries impose stringent measures like lockdowns and border closures, leading to supply chain disruptions and weak healthcare (Lau et al., 2020; Khorram-Manesh et al., 2021; Siegrist et al., 2021; Swanson and Santamaria, 2021; Chen et al., 2022; Moosavi et al., 2022).

Cruise ships are performed as ‘isolated communities’ with encircled settings and specific characteristics, including crowded and closed public rooms and living accommodations, shared water and food supplies, common hygienic facilities, and a large population from different regions (Li et al., 2021). Cruise ships are often set for infectious disease outbreaks with their closed environment, contact between passengers from different countries, and crew transfers between ships (Moriarty et al., 2020). Weak cruise ships have air circulation that is not from the outdoors and no clean air, closed corridors, and some cabins with no windows. In other words, the ships have an ideal environment for virus spreading (Ilhan, 2020). This leads to COVID-19 being quickly spread onboard through food, infected persons, surface, and contaminated water (Dahl, 2020).

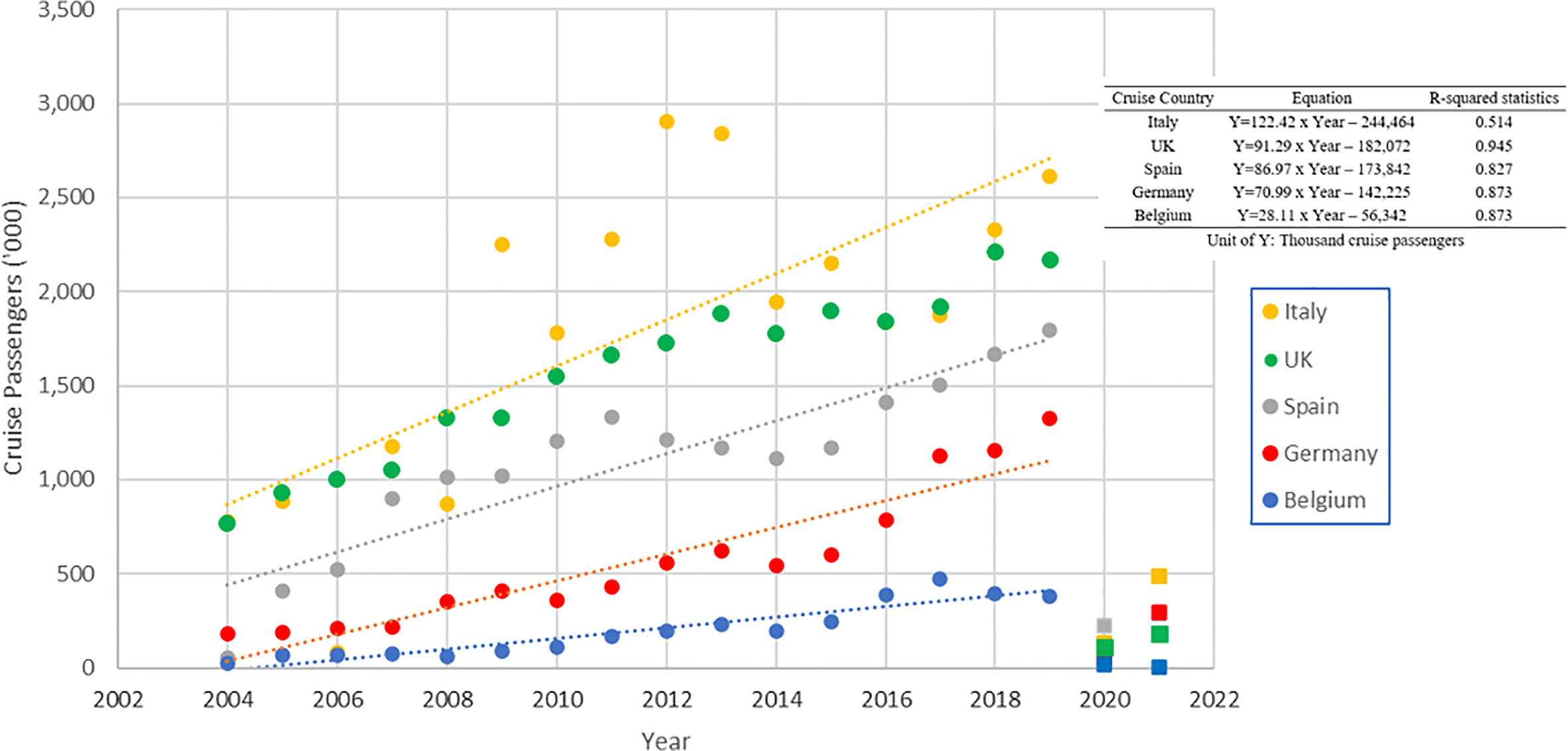

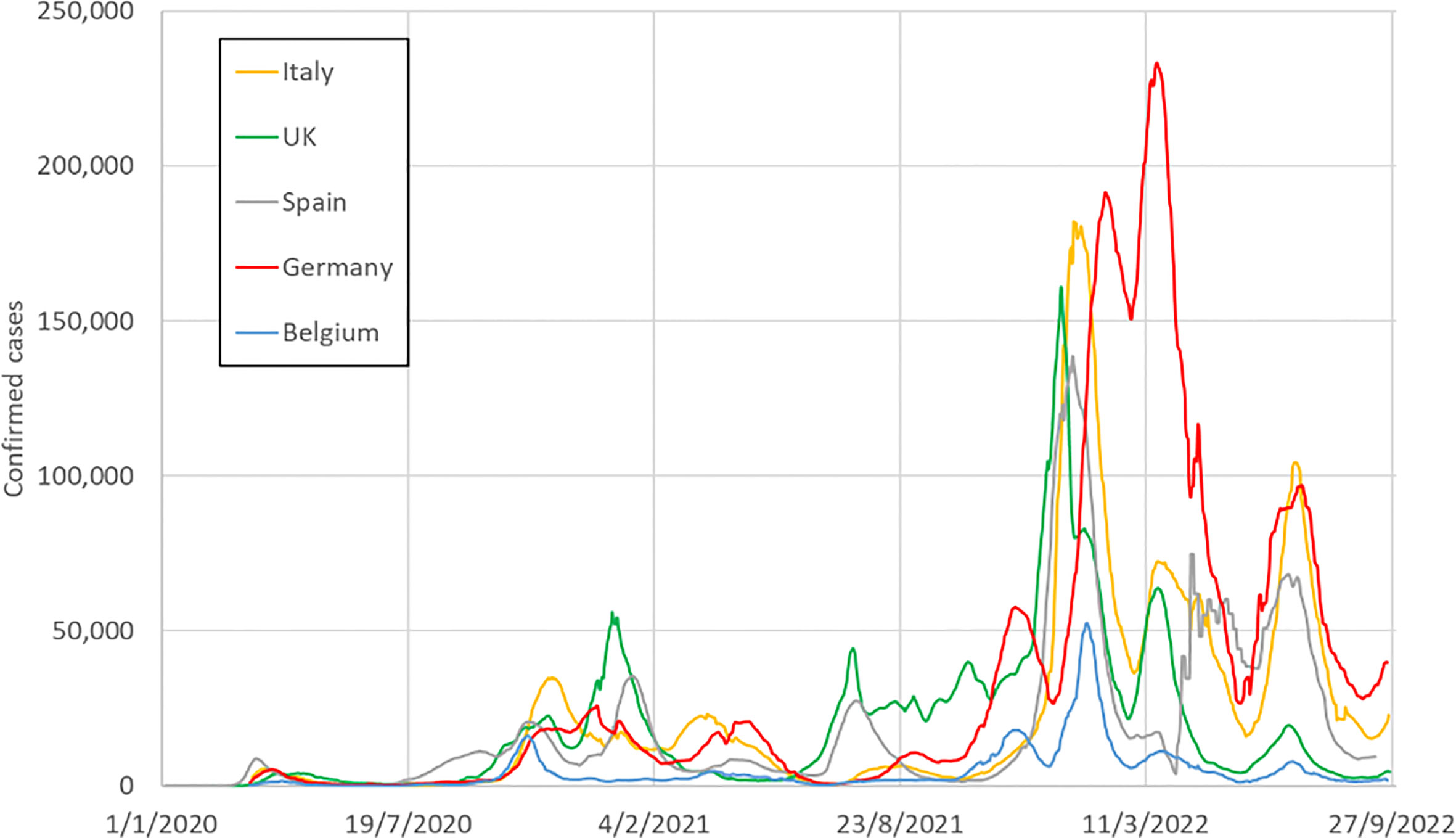

The cruise industry seriously also suffered from this crisis. Crystal Cruises, Cunard Line, Victory Cruises, and Windstar fully cancelled their itineraries on August 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Lau et al., 2022b). The number of cruise passengers in the UK increased from 2010 to 2019 steadily. If COVID-19 did not exist, the number of cruise passengers would reach 2.2 million in 2020 based on our forecasting model (Figure 1). The forecasting model is reliable because the data is collected from the UK Government Digital Service. Many newly confirmed cases in the UK were discovered after mid-March 2021. To this end, the UK government only imposed a strict quarantine policy to control the pandemic. These bring the number of passengers hit rock bottom. Figure 2 shows new confirmed cases in the top five cruise countries in Europe. Different waves of the pandemic affect cruise operations become unpredictable. The data are also reliable as it is collected from the recognized UK government body and the international leading agency of the European Union.

Figure 1 Top five countries in Europe with the largest number of cruise passengers from 2002-2022 Source: Department for Transport, UK (2021) and EUROSTAT (2022).

Figure 2 Confirmed cases (7-day moving average) in Europe from 1 January 2020 to 30 September 2022 Sources: UK Coronavirus Dashboard (2021), and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (2023).

There is a turning point arising in the UK and the USA due to the introduction of large-scale vaccination programmes and social distancing policies to prepare for restarting cruise services in 2021 (Liu and Chang, 2020; Yuen et al., 2021; Kalosh, 2022). The UK government waived quarantine for arrivals fully vaccinated from Europe and USA from 2 August 2021. Domestic cruise lines in the UK resumed their sailings on 13 August 2021, and international cruise lines resume sailings in October 2021. To give a clear background of cruise shipping operations in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, critical cruise incidents are summarized in Table 2.

The cruise journey is divided into five main stages, including pre-embarkation (homeport), embarkation (cruise terminal), cruise (onboard), shoreside (inter-port), and disembarkation (cruise terminal) (Lau and Yip, 2020). To respond to the pandemic, cruise lines strive toward a series of anti-infection measures. Pre-boarding screening is conducted before embarkation. Passengers are screened upon entering the cruise terminal. Questionnaires, visual inspections, and temperature measurements of boarding passengers are also conducted (Lau et al., 2022b).

Further assessment, temperature, and tests may be carried out during the pre-boarding stage. Passengers and crew should practice physical distancing and stay two meters apart, use face masks in areas where physical distancing is impossible, and promote hand hygiene. Social distancing implies that a cruise ship must embark and disembark from three hours (before the pandemic) to ten hours when operating at full capacity. Additional time is needed to sanitize cruise ships. Cruising capacities under longer turnaround times will reduce the number of passengers (Lau et al., 2022b).

The notion of social transformation arose over a half-century ago. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2020) addressed that social transformation emerges from environmental change by identifying the crises like energy and water shortages, urbanization and rapid population growth, natural disasters, and climate change. Social transformation creates new global processes and enhances sustainable development in the globalization process. Therefore, it needs to think globally before acting locally since the social transformation is closely associated with globalization.

Social transformation implies innovative learning to generate new structures, problem formulation, and values in a complicated and complex changing environment (Korten, 1981). Since the 2000s, the availability and adoption of digital information communication technologies (ICTs) have fostered social transformation. Hence, it could introduce new communication channels and enable new media interactivity (Dutton, 2004). Recent innovations in technologies (e.g., artificial intelligence, robotics, virtual reality) are expected to create a remarkable social transformation (Boyd and Holton, 2018).

Most studies on social transformation focused on decolonization, nation-state formation, and political position (Mamdani et al., 1988; Embong, 1996; Law, 2002). Consequently, social transformation is dominated by the political science discipline (Castles, 2001). Mamdani et al. (1988) used social transformation to identify the impact of social movements and democracy in Africa. Embong (1996) examined the relationships between social transformation and post-independence Malaysia. Law (2002) investigated associations between social transformation, education reform, and law in China. The social transformation was also focused on economic issues and sociology (New, 1994; Castles, 2003; Barkin and Sánchez, 2020). However, the concept of social transformation has been neglected from a transport perspective, especially maritime transport. This will be addressed in the present study.

Social transformation in the cruise industry is an urgent demand. The industry is now facing sophisticated, unpredictable, and ever-changing social transformation issues, such as the pandemic, climate change, globalization, consumer mix and behaviors, and technological advancement. Therefore, it is difficult to expect any research theme in the present situation of social transformation that could be sufficiently considered within the limits of a sole academic discipline. This should be enlarged to different disciplinary horizons. As a result, significant insights into the management of particular social and environmental conditions are included. Moreover, the current research adopts an interdisciplinary approach to integrate social transformation and the cruise industry (Castles, 2001).

Social transformation leads to the remarkable transformation of urban, social, and economic conditions (Polanyi, 2001). To understand the key driving forces determining a social transformation of the cruise industry, the 4C’s descriptive framework is designed to categorize different factors for further building a model and comparative case study analysis in the next research.

The 4C descriptive framework is a new descriptive framework in cruise shipping research, which is a representation of reality. The framework consists of four main elements to create the social transformation of the cruise industry and determine the operations and strategies of cruise lines, including consumer, technology and innovation, consumer behavior, consumer experience, and consumer psychology (Figure 3).

The framework and the interview questions are developed from Cruise Trends & Industry Outlook (CLIA, 2021) that highlight eleven cruise trends, including Instagrammable cruise travel, wellness tourism, achievement travel, onboard smart tech, conscious travel, out of reach, Gen Z, off-peak adventures, working nomads, and female and solo travelers. Industrial experts are the focus group of the study to provide valuable insight and constructive advice to categorize the eleven trends into four main elements of the framework. This ensures the validity and correctness of the content. Also, the experts identify appropriate question content and design. The questions were checked by a group of experts before sending them to the interviewees. Hence, fuzzy wordings and double-barreled questions have been fully eliminated (Lau and Yip, 2020). Indeed, a group of experts supported the researcher to understand the main flow of conversation and enhance the skills in interviewing (Majid et al., 2017).

The study conducted 18 in-depth and semi-structured interviews that include cruise terminals, travel agencies, logistics, and tourism associations, researchers, cruise lines and passengers, and airlines to provide research findings. Also, we depended on past contacts via social or personal networks to access key informants employing snowball sampling. The sampling process is cumulative which fosters researchers to give the chance to adopt new participants when other contacts dry up and improve sampling clusters (Noy, 2008). We continue interviewing new participants up to a time a point of data saturation was attained (Morse, 1995). Semi-structured interviews are regarded as more appropriate than adopting chatty, informal interviews, or structured interview guides (Lau et al., 2022a). The interviews start with prearranged questions and then give the interviewers opportunities to revise the questions according to the focus of the responses or to raise probing questions as a follow-up. The interviews also encourage participants to share their experiences and perceptions easily. The interview questions are listed below:

* How are the existing cruise packages reinforced?

* Can new cruise packages be introduced into Instagrammable cruise travel?

* What are the new practices introduced by cruise ports/terminals to facilitate cruise shipping after the pandemic?

* What are the marketing strategies to fulfil the new demand for cruise shipping?

* How do female, solo, and Gen Z passengers change the demand pattern of the cruise market?

* How can cruise lines improve the passengers’ experience?

* How can cruise lines develop a new/innovative cruise itinerary?

* What are the incentive schemes to support the cruise lines develop wellness tourism and changing cruise shipping?

* Under the current social transformation due to the COVID-19 pandemic, what are the government policies introduced to improve the passengers’ confidence in taking cruise trips after the pandemic?

Although most of the interviewees are in Asia, they perform well-experienced in the European cruise market. In addition, cruise passengers repeat their cruise trips in the Asian region. They are the most frequent passengers that take cruises to ports in Europe. Thus, the interview findings can investigate how social transformation reshapes the cruise industry in the European region from Asian stakeholders’ perspectives. The interviewees’ profiles are shown in Table 3. Their profiles are qualified to give valuable insights into this study. Due to confidentiality agreements, all details of the interviews are excluded from this study. The interview findings are summarized, identified, and categorized into the appropriate items of the framework.

In this section, the content analysis is used to present the interview findings. The interview results discuss how cruise lines might take measures to create resilience against the influence affected by the COVID-19 pandemic through using social transformation. Figure 4 shows major interview results per each dimension of the 4C descriptive framework. As such, it may foster the readers with a searchable record of incidents and a structure for interviews in the future (Morse, 1995).

Consumer technology and innovation focus on reinforcing the existing cruise packages and introducing new packages into Instagrammable cruise travel (CLIA, 2021). Interviewees agreed that cruise passengers are only concerned about destinations. Thus, cruise lines may collaborate with destination managers or travel agencies to propose new destinations. Destination authorities and local governments may design attractive campaigns to promote destinations’ unique features and attractiveness. There is enough time and sufficient area for tourists to engage in onshore activities. Cruise lines may upgrade their ships’ facilities to attract more passengers. However, interviewees identified that Instagrammable cruise travel is not attractive to the elderly. In this sense, the cruise market now inclines toward the young generation. Young passengers have high purchasing power and join cruise trips at least once a year. They also are eager to participate in Instagrammable cruise travel. To this end, the internet speed and Wi-Fi facilitate the development of Instagrammable cruise travel onboard. The onboard smart tech fosters the creation of a cyber or smart cruise room. This is also found in the study of Buhalis et al. (2022).

Consumer behavior refers to designing and implementing marketing strategies in response to the new demand patterns of female, solo, and Gen Z passengers (CLIA, 2021). This is confirmed by (Jiao et al., 2021; Lau et al., 2022b). Interviewees provided the viewpoint of each pattern as follows.

Female passengers − Cruise lines may organize female activities, such as ladies’ nights, dancing, cooking classes, or spa packages with low prices. Most heads of sales departments are female. In this sense, cruise lines are concerned about the female cruise market.

Solo passengers − This passenger type may need to bear a higher accommodation fee. Cruise lines may convert some existing twin rooms into single rooms and charge a 50% accommodation fee for solo passengers. Alternatively, cruise lines may reserve specific zone areas, such as hostels for passengers to link up with each other. Also, cruise lines may waive port tax and give a discount on designated restaurants or cafes. Cruise lines can also provide social gathering activities for passengers who intend to make new friends during the trip. Interviewees emphasized that solo passengers wish cruise lines to provide personal assistance to accompany them. Compared with female and Gen Z markets, solo passengers only contribute a small proportion of the market share.

Gen Z passengers − Cruise lines may create a variety of outdoor recreational activities rock climbing walls and surf roller coasters. They may also design social network activities, such as reserve zones for dancing, carnival, and bars. Various high technology and digital products onboard should be provided. A funny advertisement with sexy wording helps to stimulate Gen Z to join a cruise trip.

Customer behavior − Interviewees indicated that cruise packages were family orientated in the past. Family members are more advanced planned. In general, these three types of passengers generate niche, unique, and unpredictable demand patterns in the market. They exhibit impulsive purchasing behavior to book their trips at the last minute. In response, cruise lines may use new promotional campaigns via social media, peer effect, and Key Opinion Leader (KOL) to promote their personalized and flexible packages (Sun et al., 2021).

Consumer experience is relevant to improving the passengers’ cruising and onshore experience and developing a new/initiative cruising experience (CLIA, 2021). According to the interview, cruise lines may explore small islands as new destinations. Also, they may focus on itineraries visiting traditional culture, rural areas, top attractions, historical sites, and shopping malls. Passengers are easily accessible to tourist attractions by various transportation modes or nearby cruise terminals. Interviewees also pointed out that cruise lines conduct extensive marketing and research by using big data analysis. This fosters cruise lines to find tourist groups that have a high purchasing power. Accordingly, cruise lines may reinforce the packages to develop a new/innovative cruising experience for passengers. This is also identified by the relevant studies of Whyte et al. (2018) and Sun et al. (2019a).

Interviewees criticized cruise lines may revamp the existing cruise ships, for instance, ship decks covering real grasses, and full glass views. This helps to create enthusiastic consumer groups and build a cruise brand Kang et al. (2020). This also provides passengers get good experiences in cruising. Interviewees revealed that a cruise itinerary design is inappropriate for visiting many cruise ports. This is because passengers feel exhausted from engaging in onshore activities and hence, it will decrease the motivation for passengers to use a cruise ship’s facilities. Interviewees suggested that cruise lines may arrange trips for passengers to investigate cruise ship operations (e.g., engine rooms) or astronomy activities.

Interviewees reflected that cruise lines need to improve the booking system, enlarge ships’ capacity, and implement passenger diversion for tourists who can wait a short time for recreational facilities. In the future, cruise lines may create membership schemes, point systems, mileage reimbursement, and loyalty programmes for passengers to earn points by cruising with cruise lines. These lead to passengers getting a lot of benefits, such as all onboard activities, priority boarding, and amazing gifts. This is also found in the study of (Yoon and Cha, 2020).

Consumer psychology is relevant to developing wellness tourism and improving the passengers’ confidence in taking cruise trips again after the pandemic (CLIA, 2021). Interviewees said that cruise lines and terminals need to take stringent disease prevention measures. All passengers and crew should be completely vaccinated. Passengers must take a COVID-19 PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) nucleic acid test within 48 hours before boarding and get a negative result. If possible, cruise lines should work with the local government to test COVID-19 by giving results within one hour. This could speed up the boarding process. In addition, cruise lines should implement a series of health control protocols, for example, crowd control, social distancing, body temperature detection, and the use of mobile applications to scan the QR code of the ships before boarding. The local government and tourism association can promote cruise trips to be a safe, clean, and hygienic environment so that the public release their worry and anxiety about the risk of cruise trips. This is confirmed by Yazir et al. (2020).

To promote the cruise lines’ brands, interviewees mentioned that cruise lines now provide a variety of wellness activities onboard. Interviewees proposed that cruise lines may allow tourists to cancel or amend their itineraries without much penalty due to COVID-19. Cruise lines or travel agencies may consider offering free health insurance covering the COVID-19 pandemic. Industrial practitioners also look for the government to provide funding schemes or subsidies to support cruise lines in developing wellness tourism, package prices, and revamping cruise ships. The government and tourism association may collaborate with cruise lines to provide a platform for matching between cruise lines and passengers. It is one of the effective ways to deliver the right cruise products to the right passengers. This is also identified by Jiao et al. (2021).

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, growth in cruise shipping was mainly supply-driven and depended on the delivery of new cruise ships and tourism experiences. Introducing new and innovative cruise ships can increase the number of cruise passengers. Cruise packages are a complex combination of itineraries and onboard facilities for entertainment (Law, 2002). After the pandemic, the cruise industry designs its itineraries based on demand (Yuen et al., 2021). Social transformation becomes more critical and is a factor that is more society specific.

The system and elements of the organizational function of the cruise industry interact with each other along the social transformation process. Inputs are resources and suppliers from the industry’s external environment. Passengers receive outputs back into the external environment. The outputs can be thought of as the reason for the industry’s existence. The outbreak of COVID-19 is an important input to the industry. It is not feasible to think that the industry can constantly restructure as its external environment changes. The industry has existing structures, societal relationships, and existing practices. Nevertheless, social transformation may occur as a response to the outbreak because the business has to be sustained (Hottola, 2014; Chua et al., 2019; Renaud, 2020; Jørgensen et al., 2021).

The findings from this study imply some important implications for marine policy. Firstly, a social transformation that is largely transforming society is inevitably extending the cruise travel behaviors for all marine cities. The implementation of a large-scale social transformation demands policymakers to revamp the image of the cruise community and improve the hygiene conditions around cruise terminals. Social transformation brings a dilemma to the marine community. The COVID-19 outbreak has suppressed the travel of marine cruises, resulting in the cruise industry earning little revenue. The industry cannot earn revenues and is suffering financial constraints. Most cruise lines pay a lot of money in refunds for cancellations and high operational costs, maintenance, and docking fees, even if not sailing. Besides, various small island nations and food suppliers highly depend on cruise tourism. The interruption of the cruise industry is seriously affecting nations and suppliers’ income, as well as the vendors in the maritime supply chain.

To re-build cruise travelling, the government should consider the following measures, which are under the 4C descriptive framework of social transformation. The government should offer incentives or subsidies to cruise travelers. For instance, the government of the passenger source market or the government of the port of embarkation of the itinerary. Also, government of the country of origin of the cruise line. Cruise lines develop their vessels globally with different itinerary options. Policymakers should encourage the cruise industry to serve itself as a new mode of travel experience. In general, cruise passengers suffer a higher price in the forthcoming months. This forces the industry to offer cheaper packages or huge discounts. Cruise packages may mitigate the sighting and activities around cruise ports. Cruise travelers become more concerned about hygiene conditions and infection risks. Similar to the International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS) developed for security risks, policymakers should provide an international code of practice or guidelines for cruise service providers. This can decrease the infection risk. Guidelines for cruise travel rely on each cruise line and are less effective on a global scale. Overall, policymakers should seek more available resources for re-developing cruise travel, which is the most important and useful method to raise the general public’s concerns about the marine environment. This is crucial for convincing potential or first-time cruise passengers to rejoin cruise trips in the future.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the cruise market was moving to the mass market for general tourists. After the pandemic, the market is recovering towards the niche market. The number of cruise passengers in Europe is forecasted to recover at a moderate rate. This study integrates the reshaping of the cruise industry using a social transformation concept and the 4C descriptive framework consisting of four elements including consumer technology and innovation, consumer behavior, consumer experience, and consumer psychology.

In consumer technology and innovation, instagrammable cruise travel is not attractive to the elderly but more attractive to young people. Cruise lines should provide onboard smart tech. In consumer behavior, cruise passengers are divided into female, solo, and Gen Z demand patterns. Female passengers become a powerful market. Cruise lines should organize specific activities or trip them. Solo passengers need to bear a higher accommodation fee. They also wish cruise lines to provide personal assistance. However, this type has a small market share. Gen Z is a young passenger who wants a variety of outdoor activities. Cruise lines should design social network activities. A funny advertisement helps to stimulate them to join a cruise trip. Based on these, cruise lines should offer campaigns via social media, peer effect, and Key Opinion Leaders to promote their personalized and flexible packages. In consumer experience, cruise lines should find new islands as new destinations, bringing passengers getting new experiences. Itineraries must be redesigned to consist of traditional culture, rural areas, top attractions, historical sites, and shopping malls. In terms of consumer psychology, cruise lines must organize wellness trips to make passengers feel safe from infection. This can be done by taking stringent disease prevention measures. All passengers and crew must be fully vaccinated and take a COVID-19 test before boarding.

The findings from the above results may be helpful for cruise lines and relevant sectors to design operations for preparing their revitalization after the pandemic. The study is useful to segment cruise passenger types based on socioeconomic and demographic features and attitudinal and motivational variables to foster. This helps to do a cluster analysis. The study encourages cruise lines to design and implement a target marketing strategy to attract more potential, repeated, and young tourists. Additionally, the findings also help cruise lines to design new innovative cruise packages and deliver images of cruise products to encourage passengers to cruise again.

This study is subject to some limitations that may be considered in future research.

* First, the study focused only on the qualitative approach by interview. The main weakness of qualitative research is subjective which leads to data that is erroneous or oversimplified. To offset the weaknesses of the qualitative approach, future research may carry out a large-scale survey questionnaire to generalize the study and improve the validity of the investigation via the triangulation of the outcomes from various approaches. Also, the researchers can capture the complexity and diversity of the research circumstance via the comprehensive data set.

* Second, the present study did not take into account the notion of organizational behavior and institutional approaches, such as recovery strategies, innovative policies for the resilience cruise industry, and the effect of social transformation on the cruise sector’s sustainability. These should be considered in future research for designing and implementing strategies in the post-COVID-19 pandemic.

* Third, we have selected most of the interviewees from the Asian region, as well as the research area is concentrated on the European cruise market. In the next research, we may enlarge the interviewees from European and North American regions to investigate their perceptions of the Asian, European, North American, and Arctic regions. As expected, it may help the cruise lines, cruise port operators, and destination managers to design and implement appropriate strategies for different market segments and from different cruisers’ perspectives.

* Fourth, some emerging cruise ship tourism research topics are excluded in this current study including the application of technology in cruise tourism, the cultural effects of cruise tourism in destination, pre-consumption behavior of tourists, information sharing and socialization of cruise tourism experiences adopting social media, and environmental issues (Wondirad, 2019). As such, we may consider integrating the concept of social transformation into the aforementioned emerging topic in the future.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Research Committee at the College of Professional and Continuing Education, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (RC/ETH/H/0115). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

TY contributes to the conceptualization, methodology, data collection, formal analysis, and manuscript writing. YL contributes to methodology, data collection, formal analysis, and manuscript writing. MK contributes to formal analysis, manuscript writing, and manuscript reviewing and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was partially supported by a grant from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Project ID: P0039898 or project No: G-UAN9).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ajamil B., Partners (2020) The impact of social separation and other protocols on homeport / inter-port terminal operations. Available at: https://Www.Cruiseeurope.Com/Site/Assets/Files/35272/Impact_Of_Social_Separation_V_5_4_08_19_20_Europe.Pdf.

Barkin D., Sánchez A. (2020). The communitarian revolutionary subject: new forms of social transformation. Third World Q. 41, 1421–1441. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2019.1636370

Boyd R., Holton R. J. (2018). Technology, innovation, employment, and power: do robotics and artificial intelligence really mean social transformation? J. Of Sociology 54, 331–345. doi: 10.1177/1440783317726591

Buhalis D., Papathanassis A., Vafeidou M. (2022). Smart cruising: smart technology applications and their diffusion in cruise tourism. J. Of Hospitality And Tourism Technol. 13, 626–649. doi: 10.1108/JHTT-05-2021-0155

Castles S. (2001). Studying social transformation. Int. Political Sci. Rev. 22, 13–32. doi: 10.1177/0192512101221002

Castles S. (2003). Towards a sociology of forced migration and social transformation. Sociology 37, 13–34. doi: 10.1177/0038038503037001384

CBI (2021) The European market potential for cruise tourism. Available at: https://Www.Cbi.Eu/Market-Information/Tourism/Cruise-Tourism/Market-Potential#What-Makes-Europe-An-Interesting-Market-For-Cruise-Tourism.

Chen Q., Ge Y. E., Lau Y. Y., Dulebenets M. A., Sun X., Kawasaki T., et al. (2022). Effects of covid-19 on passenger shipping activities and emissions: empirical analysis of passenger ships in Danish waters. Maritime Policy Manage. 50, 776–796. doi: 10.1080/03088839.2021.2021595

Choe Y., Wang J., Song H. (2021). The impact of the middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus on inbound tourism in south Korea toward sustainable tourism. J. Of Sustain. Tourism 29, 1117–1133. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1797057

Chua B.-L., Lee S., Kim H.-C., Han H. (2019). Investigation of cruise vacationers’ behavioral intention formation in the fast-growing cruise industry: the moderating impact of gender and age. J. Of Vacation Marketing 25, 51–70. doi: 10.1177/1356766717750419

CLIA (2020) 2019 Asia cruise deployment & capacity report. Available at: https://Cruising.Org/-/Media/Research-Updates/Research/2019-Asia-Deployment-And-Capacity—Cruise-Industry-Report.Pdf.

CLIA (2021) State of the cruise industry outlook. Available at: https://Cruising.Org/En/News-And-Research/Research/2019/December/State-Of-The-Cruise-Industry-Outlook-2020.

Dahl E. (2020). Coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak on the cruise ship diamond princess. Int. Maritime Health 71, 5–8. doi: 10.5603/MH.2020.0003

Department For Transport, Uk. (2021). Sea passenger statistics: data tables (SPAS). Available at: https://Www.Gov.Uk/Government/Statistical-Data-Sets/Sea-Passenger-Statistics-Spas.

Diakomihalis M. N., Stefanidaki E., Chytis E. (2016). Cruise ship cost analysis: an ahp study on cost components. 6, 265–280. doi: 10.1504/IJDSRM.2016.079792

Di Vaio A., López-Ojeda A., Manrique-De-Lara-Peñate C., Trujillo L. (2021a). The measurement of sustainable behaviour and satisfaction with services in cruise tourism experiences. an empirical analysis. Res. In Transportation Business Manage. 45, 100619. doi: 10.1016/j.rtbm.2021.100619

Di Vaio A., Varriale L., Lekakou M., Stefanidaki E. (2021b). Cruise and container shipping companies: a comparative analysis of sustainable development goals through environmental sustainability disclosure. Maritime Policy Manage. 48, 184–212. doi: 10.1080/03088839.2020.1754480

Dutton W. H. (2004). Social transformation in an information society: rethinking access to you and the world (Paris: Unesco Paris).

Embong A. R. (1996). Social transformation, the state and the middle classes in post-independence Malaysia. Japanese J. Of Southeast Asian Stud. 34, 524–547.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. (2023). Geographical distribution of confirmed cases of MERS-CoV, by reporting country. Available at: https://Www.Ecdc.Europa.Eu/En.

EUROSTAT (2022). Available at: https://Ec.Europa.Eu/Eurostat/Web/Products-Eurostat-News/-/Ddn-20190816-1.

Hottola P. (2014). Somewhat empty meeting grounds: travelers in south India. Ann. Of Tourism Res. 44, 270–282. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2013.10.007

Hovelsrud G. K., Veland S., Kaltenborn B., Olsen J., Dannevig H. (2021). Sustainable tourism in Svalbard: balancing economic growth, sustainability, and environmental governance. Polar Rec. 57, 1–7. doi: 10.1017/S0032247421000668

Ilhan E. (2020). The impact of coronavirus disease (Covid-19) pandemic on cruise industry: case of diamond princess cruise ship. Mersin Univ. J. Of Maritime Faculty 2, 32–37. Available at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/meujmaf/issue/55687/738940.

Jiao Y., Hou Y., Lau Y.-Y. (2021). Segmenting cruise consumers by motivation for an emerging market: a case of China. Front. In Psychol. 12, 606785. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.606785

Jørgensen M. T., Hansen A. V., Sørensen F., Fuglsang L., Sundbo J., Jensen J. F. (2021). Collective tourism social entrepreneurship: a means for community mobilization and social transformation. Ann. Of Tourism Res. 88, 103171. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2021.103171

Kalosh A. (2022) Msc virtuosa maiden voyage marks uk cruise industry restart. Available at: https://Www.Seatrade-Cruise.Com/Ship-Operations/Msc-Virtuosa-Maiden-Voyage-Marks-Uk-Cruise-Industry-Restart.

Kang J., Kwun D. J., Hahm J. J. (2020). Turning your customers into brand evangelists: evidence from cruise travelers. J. Of Qual. Assur. In Hospitality Tourism 21, 617–643. doi: 10.1080/1528008X.2020.1721039

Kawasaki T., Lau Y.-Y. (2020). Exploring potential cruisers behavior based on a preference model: the Japanese cruise market. Maritime Business Rev. 5, 391–407. doi: 10.1108/MABR-03-2020-0011

Khorram-Manesh A., Dulebenets M. A., Goniewicz K. (2021). Implementing public health strategies - the need for educational initiatives: a systematic review. Int. J. Of Environ. Res. And Public Health 18, 5888. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115888

Korten D. C. (1981). The management of social transformation. Public Administration Review 41 (6), 609–618.

Kunjuraman V., Hussin R., Aziz R. C. (2022). Community-based ecotourism as a social transformation tool for rural community: a victory or a quagmire? J Outdoor Recreat Tour 39, 100524. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2022.100524

Lau Y.-Y., Tam K.-C., Ng A. K., Pallis A. A. (2014). Cruise terminals site selection process: an institutional analysis of the kai tak cruise terminal in Hong Kong. Res. In Transportation Business Manage. 13, 16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.rtbm.2014.10.003

Lau Y.-Y., Tang Y. M., Yiu N. S., Ho C. S. W., Kwok W. Y. Y., Cheung K. (2022a). Perceptions and challenges of engineering and science transfer students from community college to university in a Chinese educational context. Front. In Psychol. 12, 797888. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.797888

Lau Y.-Y., Yip T. L. (2020). The Asia cruise tourism industry: current trend and future outlook. Asian J. Of Shipping And Logistics 36, 202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ajsl.2020.03.003

Lau Y.-Y., Yip T. L., Kanrak M. (2022b). Fundamental shifts of cruise shipping in the post-Covid-19 era. Sustainability 14, 14990. doi: 10.3390/su142214990

Lau Y. Y., Zhang J., Ng A. K., Roozbeh P. (2020). Implications of a pandemic outbreak risk: a discussion on china's emergency logistics in the era of coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19). J. Of Int. Logistics And Trade 18, 127–135. doi: 10.24006/jilt.2020.18.3.127

Law W.-W. (2002). Legislation, education reform and social transformation: the people's republic of china's experience. Int. J. Of Educ. Dev. 22, 579–602. doi: 10.1016/S0738-0593(01)00029-3

Li H., Meng S., Tong H. (2021). How to control cruise ship disease risk? inspiration from the research literature. Mar. Policy 132, 104652. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104652

Liu X., Chang Y.-C. (2020). An emergency responding mechanism for cruise epidemic prevention–taking covid-19 as an example. Mar. Policy 119, 104093. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104093

López-González J. L. (2018). Exploring discourse ethics for tourism transformation. Tourism: Int. Interdiscip. J. 66, 269–281.

Majid M. A. A., Othman M., Mohamad S. F., Lim S. A. H., Yusof A. (2017). Piloting for interviews in qualitative research: operationalization and lessons learnt. Int. J. Of Acad. Res. In Business And Soc. Sci. 7 (4), 1073–1080. doi: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i4/2916

Mamdani M., Mkandawire T., Wamba-Dia-Wamba (1988). Social movements, social transformation and struggle for democracy in Africa. Economic And Political Weekly, 973–981.

Monaco S. (2018). Tourism and the new generations: emerging trends and social implications in Italy. J. Of Tourism Futures 4, 7–15. doi: 10.1108/JTF-12-2017-0053

Mondou V., Taunay B. (2012). The adaptation strategies of the cruise lines to the Chinese tourists. Tourism: Int. Interdiscip. J. 60, 43–54.

Moosavi J., Fathollahi-Fard A. M., Dulebenets M. A. (2022). Supply chain disruption during the covid-19 pandemic: recognizing potential disruption management strategies. Int. J. Of Disaster Risk Reduction 75, 102983. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.102983

Moriarty L. F., Plucinski M. M., Marston B. J., Kurbatova E. V., Knust B., Murray E. L., et al. (2020). Public health responses to covid-19 outbreaks on cruise ships–worldwide, February–march 2020. Morbidity And Mortality Weekly Rep. 69, 347. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e3

Morse J. M. (1995). The significance of saturation. Qual. Health Res. 5, 147–149. doi: 10.1177/104973239500500201

Network, W. C (2020). Available at: https://Www.Worldcruise-Network.Com/Projects/Genesis-Class/.

New C. (1994). Structure, agency and social transformation. J. For Theory Of Soc. Behav. 24, 187–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5914.1994.tb00252.x

Noy C. (2008). Sampling knowledge: the hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. Int. J. Of Soc. Res. Method. 11, 327–344. doi: 10.1080/13645570701401305

Parnyakov A. V. (2014). Innovation and design of cruise ships. Pacific Sci. Rev. 16, 280–282. doi: 10.1016/j.pscr.2015.02.001

Polanyi K. (2001). The great transformation: the political and economic origins of our time (Boston: Beacon Press).

Renaud L. (2020). Reconsidering global mobility–distancing from mass cruise tourism in the aftermath of covid-19. Tourism Geographies 22, 679–689. doi: 10.1080/14616688.2020.1762116

Rodrigue J.-P., Notteboom T. (2013). The geography of cruises: itineraries, not destinations. Appl. Geogr. 38, 31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.11.011

Sheller M. (2021). Reconstructing tourism in the Caribbean: connecting pandemic recovery, climate resilience and sustainable tourism through mobility justice. J. Of Sustain. Tourism 29, 1436–1449. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1791141

Siegrist M., Luchsinger L., Bearth A. (2021). The impact of trust and risk perception on the acceptance of measures to reduce covid-19 cases. Risk Anal. 41 (5), 787–800. doi: 10.1111/risa.13675

Su L., Tang B., Nawijn J. (2021). How tourism activity shapes travel experience sharing: tourist well-being and social context. Ann. Of Tourism Res. 91, 103316. doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2021.103316

Sun X., Kwortnik R., Xu M., Lau Y.-Y., Ni R. (2021). Shore excursions of cruise destinations: product categories, resource allocation, and regional differentiation. J. Of Destination Marketing Manage. 22, 100660. doi: 10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100660

Sun X., Xu M., Lau Y.-Y., Gauri D. K. (2019a). Cruisers’ satisfaction with shore experience: an empirical study on a China-Japan itinerary. Ocean Coast. Manage. 181, 104867. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.104867

Sun X., Yip T. L., Lau Y.-Y. (2019b). Location characteristics of cruise terminals in China: a lesson from Hong Kong and shanghai. Sustainability 11, 5056. doi: 10.3390/su11185056

Swanson D., Santamaria L. (2021). Pandemic supply chain research: a structured literature review and bibliometric network analysis. Logistics 5, 7. doi: 10.3390/logistics5010007

UK Coronavirus Dashboard (2021). Download data. Available at: https://Coronavirus.Data.Gov.Uk/Details/Download.

UNESCO (2020). Available at: https://En.Unesco.Org/Themes/Social-Transformations.

Watch C. M. (2022). Available at: https://Cruisemarketwatch.Com/Market-Share/.

WHO. (2023). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available at: https://Covid19.Who.Int/.

Whyte L. J., Packer J., Ballantyne R. (2018). Cruise destination attributes: measuring the relative importance of the onboard and onshore aspects of cruising. Tourism Recreation Res. 43, 470–482. doi: 10.1080/02508281.2018.1470148

Wondirad A. (2019). Retracing the past, comprehending the present, and contemplating the future of cruise tourism through a meta-analysis of journal publications. Mar. Policy 108, 103618. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103618

Yazir D., Şahin B., Yip T. L., Tseng P.-H. (2020). Effects of covid-19 on maritime industry: a review. Int. Maritime Health 71, 253–264. doi: 10.5603/IMH.2020.0044

Yoon Y., Cha K. C. (2020). A qualitative review of cruise service quality: case studies from Asia. Sustainability 12, 8073. doi: 10.3390/su12198073

Keywords: social transformation, cruise industry, COVID-19 pandemic, 4C descriptive framework, cruise shipping

Citation: Yip TL, Lau Y-y and Kanrak M (2023) Social transformation in the cruise industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1179624. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1179624

Received: 04 March 2023; Accepted: 08 June 2023;

Published: 27 June 2023.

Edited by:

Di Jin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, United StatesReviewed by:

Yi-Che Shih, National Cheng Kung University, TaiwanCopyright © 2023 Yip, Lau and Kanrak. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maneerat Kanrak, bWFuZWVyYXRAa2t1LmFjLnRo

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.