95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 27 March 2023

Sec. Marine Affairs and Policy

Volume 10 - 2023 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2023.1131919

This article is part of the Research Topic Global Vessel-Source Maritime Pollution Governance—Technical Innovation and Policy Orientation View all 14 articles

The past 15 years have witnessed the rapid development of China’s cruise industry from scratch and the formation of a policy system in the cruise industry, reflecting the shift of the Chinese government’s attitude towards the cruise industry from wait-and-see, recognition and encouragement to active support. The paper conducts a statistical analysis of 128 policies related to the cruise industry issued by China’s administrative departments at all levels. It is found that the release of policies synchronizes with the development of the cruise industry, with each one providing feedback to the other. The policies do not exhibit a time lag with respect to their effects. The evolution of policy types from macro-level guidance to concrete operation is rapid, with the policy structure gradually improving. In line with current characteristics of the development of China’s cruise industry, the themes of the policies concentrate on five areas: cruise tourism services and products, port construction and development, cruise industry chain expansion, cruise industry environment and cruise industry management. However, there is still a lack of adequate policies to support and guide the industrial upgrading of cruise operation and cruise construction and its green and low-carbon development. In addition, the paper points out the main directions of future policy formulation.

From the 1980s to the outbreak of COVID-19, the cruise industry has grown steadily at an average annual rate of 7.6%, becoming one of the most active parts in the world’s tourism industry (Sun et al., 2014). Although the current international cruise tourism market is still predominantly concentrated in North America and Europe, international cruise lines continue to explore new markets and develop new routes and destinations, with more cruise tourism destinations and markets emerging at a rapid pace. Among them, the Asia-Pacific market has become one of the most striking emerging regions, with the development rate surpassing the world average level. The skyrocketing growth of the Chinese cruise market in recent decades has become a miraculous phenomenon in the global cruise economy over the past 40-odd years (Hung et al., 2019).

The year 2006 has generally been regarded as the beginning year in the development of China’s cruise industry, when Allegra of Costa Crociere, owed by Carnival Corporation & plc, launched its first homeport route in Shanghai. Within just a dozen years, China ranked second in the global cruise market, with 2.1 million tourists in 2016 and 4.88 million in 2018(Wang et al., 2020). Increasing Chinese tourists begin to accept and love cruise travel, which is a new means of tourism (Li et al., 2021a). During this period, Carnival Corporation & plc, Royal Caribbean International, Star Cruises and Mediterranean Shipping Company S.A. entered the Chinese market one after another and they deployed 15 ships in the Chinese market, with more than 40,000 beds on board in 2020 (Qian et al., 2021). Meanwhile, several domestic cruise companies have also started to boom by purchasing and leasing international cruise ships, including SkySea Holding International Ltd, Nanhai Cruises, China Taishan Cruises and Diamond Cruise. Under the impact of COVID-19, these cruise ships were suspended temporarily. During the Covid-19 epidemic, cruise epidemic prevention and control, the risks in the cruise supply chain and the impacts of cruise ship anchoring have received great attention and discussion (Li et al., 2021b; Zhang et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2023). This has also contributed to the formation of a new pattern in the cruise industry during the post-epidemic recovery process. With the normalization of the global epidemic, cruise lines in most regions have resumed service on a large scale. Cruise companies will develop more cruise brands and deploy varied routes to provide diversified products and services to cater to the needs of the gradually mature Chinese market.

With the joint efforts of the government, industry organizations, various enterprises and other stakeholders of the cruise industry, China’s cruise industry has developed from scratch, overcoming numerous difficulties in the management as well as the system and achieving remarkable results. What is noteworthy is the springing up of modern cruise terminals (Ma et al., 2018). Although most of the tremendous wharf construction costs have not been recovered and the profits of the wharf operation itself are unstable, the supporting services such as ship supplies and trade services driven by the wharf services have brought generous profits to the port cities and related industries.

China aims at developing a more complete cruise industry chain and gaining more economic benefits. In this process, a series of policies to promote the development of the cruise industry at the national and local levels were issued in succession to bridge the gaps in policies and systems, while trying to solve new problems encountered in such areas as tourism services, transportation, labor, trade, market regulation and so on. While China has gradually established institutional measures in line with the international standards of the cruise industry, it has also innovatively explored the “China model” in the industry.

Related studies have also gradually deepened with the development of the industry and its policies. At the early stage of the development of China’s cruise industry, Li and Yan (2013) and He (2015) analyzed the gaps and obstacles in the policies and laws related to the development of China’s cruise industry, and suggested the implementation of such policies as tax preferences, customs clearance facilitation, cruise finance, foreign investment access, and cruise ship supply. With the further development of the industry, policy studies of industrial elements have also begun to emerge, such as policy research concerning the construction of domestic cruise ships in China (Xie, 2020), and environmental policy response and evolution of pollution problems in cruise shipping (Qin and Wang, 2019). In terms of policy innovation, Sun and Lin (2021) explored the relationship between policy innovation and industrial evolution, arguing that the interaction between cruise industry elements, operational management systems, and macro and auxiliary support systems must be considered holistically in the process of policy formulation.

The paper collects 128 cruise-related policy documents issued by Chinese governments at all levels during the 15 years of the initial development of China’s cruise industry, systematically analyzes their themes, contents and characteristics, and seeks to address the following questions: First, does China’s cruise policies reflect the change in the government’s attitude towards the cruise industry in the past 15 years? Second, how effective are the cruise policies? Third, do policies and the market develop synchronously? Do policies drive markets, or vice versa? Fourth, how do the policies affect the development of China’s cruise industrial chain? Are the policies proactive or passive to meet the needs of industrial development and upgrading?

The main contribution of this study lies in two aspects: First, by probing into China’s cruise policies and the development process of China’s cruise industry, we can reveal the evolutionary relationship between the policy and the industry. Second, based on the above-mentioned study, the problems regarding policies in the development and upgrading process of the cruise industry are identified, and future directions for cruise policies are proposed. Therefore, this study will help to provide reference and support for the development of China’s cruise industry from a policy perspective.

Cruise industry is a composite industry with the cruise ship as the core and sea sightseeing as the main content, involving many sectors, from transportation, ship design and manufacturing, homeport construction, port services, tourism services, ship material supply and replenishment, cruise operation, food shopping and business development, finance, insurance, to education and training (Clancy, 2008; Gibson, 2018). The trajectory of the upgrading and development of the cruise industry chain can be summarized as Figure 1 according to industrial value chain.

In terms of supply, international cruise ship industrial chain is basically composed of three parts:

The first is the design and construction of cruise ships, whose main body is the cruise shipyard. Since cruise ship design and manufacturing is a capital and technology intensive industry, it requires a large number of supporting products and technical services, which can drive the common development of related industries with a ratio of 1:44 in business, so it belongs to the upstream industrial chain (Liu et al., 2011). With the advanced design concept and shipbuilding technology, European corporations has dominated the global cruise manufacturing industry, obtaining tens of billions of euros in revenue every year (Kowalczyk, 2018).

The second, the midstream industrial chain, is the operation of the cruise itself, whose main body is the cruise company. At present, cruise companies such as the world’s three largest cruise groups, namely Carnival Corporation & PLC, Royal Caribbean International and Star Cruises, account for virtually 80% of the market share in the world cruise industry (Syriopoulos et al., 2020).

The third is the downstream industry chain, composed of the construction of cruise terminals and supporting facilities and related services. The cruise terminal services mainly provide supporting services such as berthing, towing, marine supplies, tourism services and business services for cruise ships.

With the continuous extension of the international cruise industrial chain, cruise tourism will bring a great flow of people, information and traffic to cruise home ports and port cities, thus effectively driving the formation and development of logistics, communications, real estate, culture, tourism, catering, shopping and other related industries in these regions (Pallis, 2015). Being at the high end of the value chain, Cruise tourism connects cruise ships and multiple cruise destinations, drives the flow of products and services in port cities and surrounding areas, stimulates massive consumption and triggers value-added effects.

From the perspective of industrial chains, China’s cruise industry is still in its infancy. Apart from the exploration of cruise market and port construction, China’s current main industry is centered on cruise port cities, and its main business is the construction and development of tourism services and terminal services. The main characteristics are reflected in the following three aspects:

First, the Chinese cruise market has developed by leaps and bounds. Since the 1980s, modern cruise tourism has entered the stage of rapid development with an average annual growth rate of 7.2% (Qian et al., 2021). The United States is now the world’s largest cruise consumption market, accounting for approximately half of the global cruise market share. Britain, Germany, Italy and Spain are the main sources of passengers in the European cruise market (Dowling and Weeden, 2017). However, in recent years the market share of other emerging regions has been increasing. After a dozen years of rapid growth, China’s cruise market has jumped to the second largest one next only to the United States (Table 1). With a high percentage of about 90%, the travel agency charter model is a unique sales mode in China and a catalyst for the vigorous growth of the Chinese market (Sun et al., 2016; Li et al., 2021a).

Second, there is a new wave of Chinese cruise port construction and a rapid growth of home port voyages. At present, China’s coastal port cities are also competing to develop cruise economy. From 2010 to 2019, port facilities with the function of home ports were built in 13 cities, including Tianjin, Shanghai, Xiamen and Sanya and basic supporting services have been provided through development, thus bringing preliminary economic benefits to port cities and regions. The water depth conditions and terminal facilities of cruise ports have laid a solid foundation for cruise companies to open homeport routes. Figure 2 shows the statistics of homeport voyages and visiting port voyages in Mainland China from 2007 to 2019, and Figure 3 shows the number of cruise trips in various ports in China. Cruise companies in the Chinese market launched a variety of cruise tourism products, among which the more mature lines are distributed in Northeast Asia, Southeast Asia and Taiwan, China.

Third, China’s cruise products are supplied mainly by foreign cruise companies. In general, cruises operating in China are from corporations with foreign capital. In 2006, Costa Crociere opened its home port in Shanghai for the first time and its huge potential passenger source market is valued by cruise companies. Since then, Costa Crociere of Italy, Royal Caribbean International of the United States and Genting Hong Kong Limited (Star Cruises) have successively opened cruise lines departing from their home ports in China, and the number of beds on international cruises operating in China has increased from 900 in 2006 to 16,000 at present. Figure 4 presents a timeline of cruise ships operating in China. Despite several attempts, local cruise companies haven’t really been established.

As a complex industry, the cruise industry includes, among others, cruise manufacturing, cruise operations, port reception and tourism consumption. It depends on the combined support of the related industries, national strategies, rules, regulations and policies. To solve bottleneck problems, it requires government departments to strengthen guidance in the formulation of policies and the reinforcement of management mechanisms, thereby promoting industrial upgrading and alleviating possible negative effects (Johnson, 2002; Small and Oxenford, 2022). Since international cruise ships are imported goods in China, the original ship and ocean transportation management systems are not necessarily suitable to the Chinese market and therefore after 2006, policies were frequently rolled out in China to promote the growth of the cruise industry.

The policy documents selected by this study are all from public data, including 128 cruise policy documents obtained from official government websites. Overall, the policy-releasing entities exhibit the following three characteristics:

First, there is a large number of policies, at both the national and the local levels, among which 70 documents were from national agencies and 83 from local agencies (the total documents outnumber the policies because some policies are jointly released by multiple departments). Figure 5 shows that at the national level, The State Council, the highest administrative authority in China, is the major policy-issuing body (up to 26) and at the local level, the local authorities are the principal issuing entities (up to 45). This strongly indicates that the national and local government agencies attach great importance to the cruise industry.

Second, the fact that policy-issuing entities include many departments is indicative of the gradual maturity of cruise industry policies in China. According to Figure 5, it can be found that there are more than a dozen policy-issuing departments. Besides the State Council and local governments, the departments involved include the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the National Customs Administration, the Ministry of Transport, the Supreme People’s Court, the State Oceanic Administration, the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of Finance, the National Immigration Bureau, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Commerce, the Ministry of Information Industry. It can be also noted that the Ministry of Transport and the Ministry of Culture and Tourism rank among the top in the number of released policies, showing that China’s cruise industry policies mainly support and serve port construction and tourism services. The number of policies released by the National Development and Reform Commission and local finance bureau is also quite large, demonstrating China’s substantial support of the cruise industry concerning industrial planning layout and local financial policies.

Third, local policies are mostly issued by cities and regions where cruise ports are located (Figure 6), such as Shanghai, Tianjin and Hainan. There is no doubt that these local policies are beneficial to the development of cruise ports and tourism in these cities. Is it the case that there are more cruise lines where more policies are made? Which is more obvious, local policies or national ones? A correlation analysis will be conducted later to address these issues.

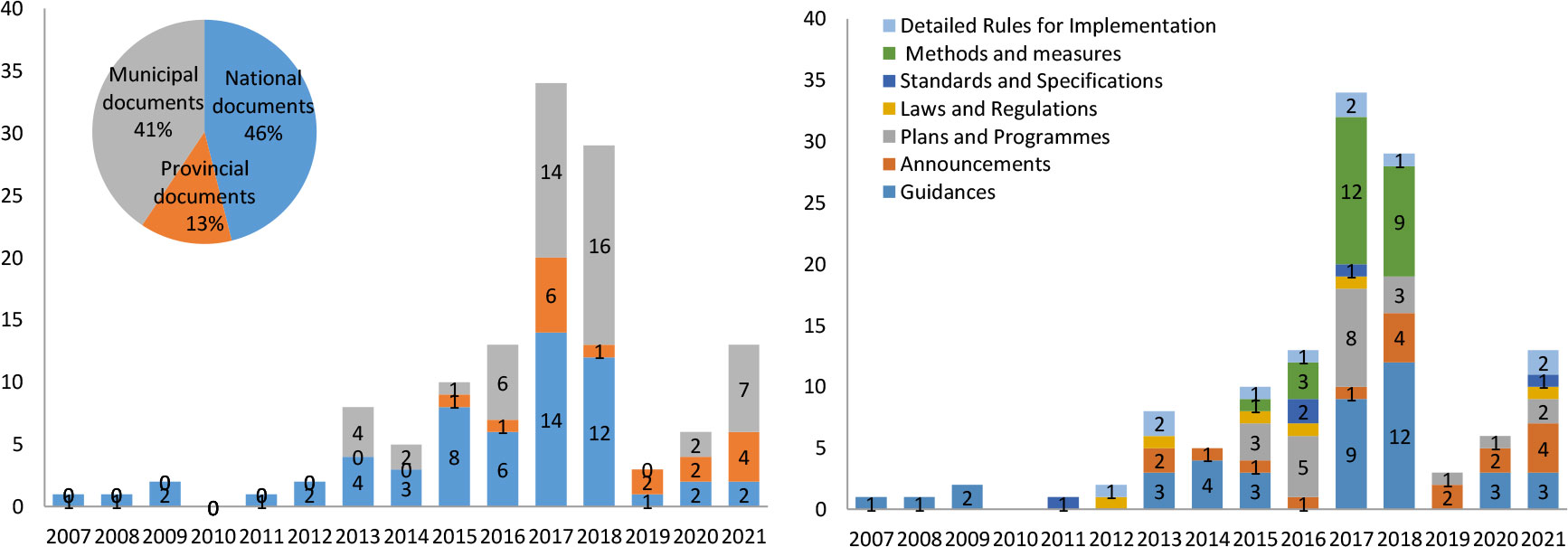

There are 128 cruise policy documents collected and this study analyzes their release time and types. We find that the number of released policies fluctuates greatly during the period from 2007 to 2021(Figure 7), which can be roughly divided into three stages:

Figure 7 Types of released policies. Note: The figure on the left shows statistics of policies issued by administrative bodies at different levels; The figure on the right shows the statistics of the number of different policy types.

In these four years, the number of issued policies was relatively small, totaling only 4. From the perspective of policy types (Figure 7), the policies are all macro-guiding ones at the national level, lacking policies released at the provincial and municipal levels. The themes of the four policies manifest that at this initial stage, the Chinese government recognizes the role of cruise tourism as a new tourism product in enriching the tourism consumption market. However, it has not yet been made explicit how to develop the cruise industry. Therefore, policies at this stage reflects that China takes a positive approach towards the cruise industry but are still on the sideline s.

There were 101 policy documents issued during the seven-year period, with the number of policies rising sharply for each subsequent year. In 2017 alone, there were 34 policies released. The types of released policies are also diversified. The number of provincial and municipal documents increased to a large extent, and especially from 2016 to 2018, the proportion of local policies exceeded that of national policies. Local cruise policies mainly focus on cruise port cities and regions. With national policies as the basis, they have issued more documents on cruise port construction and development, cruise tourism services and market norms to resolve practical issues in local industries.

At this stage, the proportion of guiding documents gradually decreases, and more specific operational documents are put in place, including announcements, plans and programs, laws and regulations, standards and specifications, methods and measures, detailed rules for implementation. This change shows that China’s cruise policies and the development of the industry, to some extent, mutually reinforce each other. Put simply, the policies promote the development of the industry, which in turn calls for new policy requirements. From macro-level guidance documents to micro-level specific operational documents, the cruise policies have been systematically formulated, indicating the gradual process of development in China’s cruise industry.

After the period of policy development, the speed of issuing policies began to slow down, and a total of 22 policy documents were released in three years, which is related to the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the cruise industry. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, China’s tourism industry has ground to a halt and the normal operation has not been resumed yet.

However, it is true that cruise policy documents in the past three years were mainly issued by local documents, and policies are executed more efficiently and operationalized in a more standardized manner, indicating that the policies have penetrated into the specific industry level.

Compared with the previous two phases, the policy themes touch more on deep-rooted and new issues of industrial development, including epidemic prevention and control, safety and hygiene, encouragement of new routes and combined transportation, and planning and development of local cruise ports and tourism services.

Because the cruise policies issued by the state and local governments will actively promote the development in all aspects of the cruise industry, enhance the market attraction of cruise products, and provide cruise enterprises with more convenience and support conditions, international cruise companies will deploy more cruise ships in China to operate more voyages. Therefore, cruise voyage is a very straightforward indicator, and the change can be a good measure of the size of the market and the development of the cruise industry (Dwyer et al., 2004).

To verify the impact and effect of cruise policies, we conducted a correlation analysis between the number of policies and the number of voyages. The following four hypotheses are formulated in this study.

Hypothesis 1: The effects of national and local cruise policies are immediate. The release of the policy directly affects cruise voyages of the year. In other words, the release of the policy is directly related to cruise voyages of the year.

Hypothesis 2: It is generally believed that it takes a certain period of time for a country’s macroeconomic policy to play its role. This is the time-lagging effect of the policy, because it sometimes acts on certain factors and indirectly changes the economy. Therefore, the impact and promotion of policies on the cruise industry may be lagging behind, regardless of national or local policies. This study assumes that the industry is lagging, with a one-year delay.

Hypothesis 3: Cruise policies should promote and influence domestic and international markets in all directions. Therefore, the release of the policy is not only conducive to promoting the development of home port cruise ships, but also to attracting foreign cruise ships touring China.

Hypothesis 4: The China’s soaring cruise market is different from that of other countries and regions. Is it possible that national and local governments passively issue policies to meet and adjust to the needs of the cruise industry because of difficulties or barriers encountered in the development of the cruise industry? The study assumes that the policy is lagging, with a one-year delay.

The statistical data correlation analysis of policies and all kinds of voyages shows that cruise policies include three indicators: the number of cruise policies released, the total number of words in a policy, and the number of policies in a particular place; cruise voyages include four indicators: annual cruise voyages, visiting cruise voyages, home port cruise voyages and total cruise voyages at each port. The results of correlation analysis (Table 2) reveals some interesting phenomena during the verification of the four hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 is correct. There is a strong positive correlation between the number of policies and total voyages, with correlation coefficient up to 0.8323. An even higher correlation shows up between the number of words in policy documents and total voyages (0.865011). This result can be interpreted as: the policy directly stimulates the number of trips and there is an obvious linear relationship between the two (Figure 8). But is it really that simple? Here arises a question: does the policy affect the voyage or does the voyage affect the release of the policy? This is an issue worth discussing, since as is customary with cruise companies, itineraries and ship deployment plans are usually determined a year, or at least six months, in advance. In this case, if there is a positive correlation between the number of policies and the total voyages of the year, it can be understood that the cruise company’s confidence in the market affects its voyage deployment and thus policy release.

Hypothesis 2 is not correct. The number of policies and total voyages (one-year lag) present a weak positive correlation, and the correlation coefficient is 0.735551. Statistically speaking, the correlation is not low. However, compared with hypothesis 1, the correlation coefficient is reduced by 0.1, proving that China’s cruise policy does not have a significant lag, meaning that the correlation between policy issuance and the number of voyages in the current year is significantly greater than that of a one-year lag. Is the development and policy of China’s cruise industry synchronized?

Hypothesis 3 is partially correct. We analyzed the correlation between the release of cruise policies and homeport voyages and that between the release of cruise policies and visiting cruise voyages. It can be found that the correlation coefficient between cruise policies issued by the central government and local governments and homeport voyages in China is 0.8281, showing a strong positive correlation and an obvious linear relationship (Figure 9). However, the correlation coefficient between policy releases and visiting voyages is -0.5245, demonstrating a weak negative correlation, which is unexpected. Does the release of policy restrict the number of visits? Doesn’t the Chinese government welcome cruise ships to its ports? This is highly unlikely. According to the analysis of policy contents, policies about tourism services, port construction, incentives for cruise stops and visa-free transit are ones China has issued in recent years to encourage cruise visits, but to little effect. What is the reason behind the decrease in cruise visits?

The reason needs to be considered from the source market of cruise visitors. Most cruises to ports of visit in China come from long-haul routes in Europe and the United States, or world voyage cruise lines that extend to the Asia-Pacific region. At present, there are few world voyages in the Asia-Pacific region, and it is hard to attract enough customers in the Asia-pacific region due to consumption habits. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the European economy has continued to decline with fewer round-the-world cruise lines from the United States, so there have been fewer cruise ports of call in recent years. The areas covered by cruise lines of ports of visits are mostly distributed in the tourist destinations around the world-class home ports, such as the Caribbean region and Alaska near the source market of the United States, and the Mediterranean region near the European continent. For cruise ports in China’s coastal areas, they fail to attract sufficient cruise passengers in neighboring areas such as Japan and South Korea, so there are few short-range routes within the region.

Hypothesis 4 is not correct. In the previous analysis, it is found that China’s cruise policy has no time-lagging effect. We might as well make a bold guess. Does the government passively issue policies to meet and adjust to the needs of industrial development? A careful analysis demonstrates that it is not valid, because the correlation coefficient between the number of policies with a one-year lag and the total voyage is 0.731261. Although it presents a weak correlation, this coefficient is lower than the correlation coefficient of the synchronization of the two indicators (0.832277). Therefore, it cannot be concluded that industry promotes the policy release. However, through the analysis and verification of these assumptions, it is confirmed that policies and industrial development are synchronous, and that they provide timely feedback to each other, with a high correlation and no time lag.

In the previous section, we analyzed the number of released Chinese cruise policies and their impact, and we found that the number of release policies and the number of Chinese cruise voyages exhibit a relatively obvious synchronization. Then, the following questions need to be answered: does the release of the policies synchronize with the development of the cruise industry chain? The cruise industry chain is divided into upstream, middle and downstream. Is China’s cruise policy conducive to the upgrading of the industry?

The 128 cruise policies-related policies collected in this paper involve entry-exit, customs, maritime affairs, transportation, tourism, shipping, passenger transport, port, environmental protection, public security, taxation, among others. Following the meticulous reading and analysis of the contents of these policies, they are summarized in the following five themes: cruise tourism services and products, port construction and development, cruise industrial chain expansion, cruise industry environment and cruise industry management. Among them, cruise tourism services and products have the highest percentage (29%), followed by the cruise industry environment (23%) and, the other three (coincidentally 16%). In terms of the classification of cruise industry, the cruise policies issued by China actually shows the evolutionary process and stages of China’s cruise industry. The percentages of various theme policies in the three stages of cruise policy development are schematized in Figure 10. It can be found that the policy themes are becoming more and more diversified, which reflects the development and maturation of China’s cruise industry.

In the initial stage, especially in the first three years, the policies issued were mainly related to the environment of the cruise industry. Industrial environment refers to the development environment created by various supporting policies and measures (Tanaka, 2011), such as policies to promote reform and opening up, as well as the investment in consumption and tourism industry, incentive policies in finance, insurance and law, policies on tax rebates for international tourists, and macro development opportunities brought by China’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative (Chen and Yin, 2018). All of these comprise the supporting environment system for the cruise industry. Macro environment involved in national and local policies and the development direction has created a new opportunity for the development of the cruise industry.

Cruise port construction and port reception services are the main themes in cruise policies from 2011 to 2014. National and local government departments encourage and support the layout of cruise infrastructure in areas with good conditions for development, such as the Bohai Rim, Yangtze River Delta, Southeast Coast, Pearl River Delta and southwest coast, thus providing basic conditions for international cruise companies to deploy cruise ships and open up routes. Meanwhile, the trend of large-scale cruise ships in the world has imposed increasingly higher demands on the berth conditions and service level of cruise terminals (Rodrigue and Notteboom, 2013). The issuing of a series of policies related to the planning of Cruise ports and the development of supporting facilities in China has pushed forward the transformation of Chinese port cities and the rapid construction of several modern large-scale cruise terminals.

The policy themes released from 2015 onwards began to exhibit variation. Most notably, there has been a large number of policies released on cruise tourism services alongside the continued increase of policies on the cruise industry environment and cruise port construction.

Cruise tourism service serves as an important part of cruise policy-making and the process of the domestication of cruise tourism industry. Innovative attempts have been made in various aspects, including cruise route layout, market promotion and channel optimization, product design and brand building, tourism commodities and duty-free shopping, cruise culture and consumer market cultivation(Wang et al., 2018). Thus, China’s cruise industry has completed its layout in the primary stage in ten years, due to the fast-paced advancement of industrial environment, port construction and the tourism market.

It is also found that some polices for industry chain expansion began to be released in later years. The policies involve operating domestic Chinese-funded cruise ships and encouraging Chinese enterprises to establish Chinese-foreign joint venture or wholly owned local cruise companies by means of new construction, purchase or leasing through policy innovation, financing and financial support. The cruise design and construction is adopted in the nationally-encouraged industry list to support the localization of cruise manufacturing, and the development of the cruise industry is encouraged through the combination of technology introduction and independent innovation

Under the guidance of industrial policies, Chinese enterprises together with foreign cruise companies, the Classification Society, cruise manufacturing enterprises have jointly set up cruise manufacturing companies. The policies also cover the development of cruise ship supply, distribution services and supporting facilities, such as developing bonded warehousing for cruise ships, attracting domestic procuring business and so on. All these initiatives have paved the way for the gradual upgrading of China’s cruise industry.

The global cruise industry in 2021 showed a marked improvement over 2020, with more than half of the ships returning to sea and the carrying capacity restored. Although China’s cruise market has yet restarted, the government is still planning the layout of the industry in the years after the suspension. In the past three years, 22 policy documents have been issued in the fields of industrial environment, industrial management and industrial chain expansion to promote the upgrading and acceleration of the cruise industry. A package of policies has been released concerning creating a more open institutional environment, cultivating markets and responding to public security emergencies. For example, local governments have been encouraged to establish comprehensive bonded zones featuring cruise economy to promote the docking and linking of international cruise ports, cruise industrial parks and pilot free trade zones, and explore comprehensive supporting systems suitable for the development of new business forms of cruise economy.

China has issued 128 cruise policies in 15 years, and is unmatched by any other industries in terms of number and speed, showing the change of the Chinese government’s attitude towards the cruise industry from wait-and-see, recognition and encouragement to active support. The analysis of this study has found that:

Firstly, the release of China’s cruise policy is almost synchronous with the development of the cruise industry, and there is no time lag in the effect of the policy. The release of relevant policies in China is closely related to the development of the cruise industry and they provide mutual timely feedback. The issuing of China’s cruise policies in the past 15 years indicates a new round of internationalization and reform and opening up in the tourism industry, port development and other fields. China has made many valuable attempts in policy innovation, such as the policy of innovative cruise industry pilot zones and free trade zones and special support policies related to finance, capital, talent recruitment and route approval for the development of cruise ships with five-star flags.

Secondly, the subjects and types of policies are evolving rapidly. From national governments and relevant departments to local ones, from the macro-level guiding policies to specific program plans, laws and regulations, industry standards and the detailed rules for the implementation, a policy system has been gradually formed with the growing number of policies and the enrichment of structures, which optimizes the industrial development environment and industrial development systems and promotes the development of the cruise industry.

Thirdly, China’s cruise policies focus on five areas: cruise tourism services and products, port construction and development, cruise industry chain expansion, cruise industry environment and cruise industry management, which have accelerated the advancement of the cruise industry. However, the current policies are far from enough to achieve industrial upgrading and a policy system has not been established to meet the development requirements of middle and high-level cruise industries. There is still a long way to go in many fields, especially (Xie, 2022) cruise operation and construction.

Fourthly, given that carbon emissions exert constrains on China’s economic development, the development of the cruise industry requires more explicit policies to guide and regulate emission behaviors, especially in the context of the clear target of carbon peak and carbon neutrality (Xiao and Cui, 2023). Currently, there is a relative lack of relevant policy documents in China and it is by no means enough to have only a guiding document entitled Port and Shore Power Layout Scheme. Policies to promote the green development of the cruise industry need to be perfected at the earliest opportunity and a couple of initiatives shall be introduced, such as the application of various low-carbon and zero-carbon technologies and equipment on cruise ships, and the installation of shore-based power facilities and alternative energy refueling facilities in cruise ports.

The cruise industry covers numerous sectors, including cruise ship construction, port infrastructure, terminal, waterway and port services, ship replenishment, ship maintenance and renovation, tourism, hotels, transportation, shopping, etc. Those activities are intertwined with each other, producing direct and indirect economic contributions, with the multiplier effect. Statistics reports the European cruise industry’s multiplier effect from 2013 to 2018 was 1:8, but Norway, Finland and France account for almost all the market of cruise design and construction, with actual higher multiplier effect (Braun et al., 2002). Therefore, how policies can better promote the development of China’s cruise industry from the current primary stage of port construction and tourism services to a higher stage is an issue that needs to be addressed.

In general, the cost of building cruise ships is very high. From 2006 to 2021, international cruise lines have deployed 34 cruise ships in China, including 11 new ships specially customized for China, running up to 76.5 billion yuan, with an average cost of 7 billion yuan and 1 billion dollars per ship (Ros Chaos et al., 2021). Because of the lower capital cost, the construction of new ships in Europe and the United States shall not exert great impacts upon the operation of cruise companies (Chang et al., 2017), while the high capital cost of cruise construction in China severely limits the advancement of cruise construction, which requires relevant policy systems to be formulated to lower the costs. To provide continuous financial support for cruise construction, the establishment of cruise industry development or investment fund can be initiated under the guidance of the nation and through the participation of enterprises and private capital.

It is worth noting that Chinese cruise ships spend around 1.4 billion yuan annually on food and consumables, and 1.8 billion yuan on fuel respectively, but they have not made significant economic contributions to China. The main reason for this phenomenon can boil down to the complicated supervision of customs, which renders it difficult for many products to be replenished at Chinese ports due to complicated formalities. Over the years, through innovative policies in pilot free trade zones and cruise development zones, the proportion of replenishing at Chinese ports is increasing. However, since cruises are novelty in China, the government still needs to introduce flexible new policies to attend to the needs of the market, so as to promote the development of the cruise industry chain.

The cruise industry has created a wide variety of job opportunities. Statistically, the total number of people employed by cruise companies, cruise ports, waterways and ports and travel agencies in China has exceeded 35,000. The development of China’s cruise industry and the gradual expansion of the industrial chain require more professionals to work in related fields. Therefore, more policies are required to support talent cultivation and management.

The operation of cruises ports has brought tiny gains with the annual revenue of about 770 million yuan before Covid-19, although 13 cruise ports were built along China’s coast from 2010 to 2019, totaling more than 20 billion yuan (Chen et al., 2019). Therefore, if China’s cruise ports intend to gain more economic benefits in the future, soft services shall be further improved on the basis of a complete infrastructure, such as improving the customs clearance efficiency of cruise tourists and upgrading their experience in cruise ports. All these require the government to further simplify customs clearance procedures, and encourage management innovation of cruise ports so as to enrich the functions of ports and deliver unlimited business opportunities.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

HT: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing. SC: Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis. HL: Supervision, Resources. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Braun B. M., Xander J. A., White K. R. (2002). The impact of the cruise industry on a region’s economy: A case study of port Canaveral, Florida. Tourism Economics 8, 281–288. doi: 10.5367/000000002101298124

Chang Y.-T., Lee S., Park H.(. (2017). Efficiency analysis of major cruise lines. Tourism Manage. 58, 78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.012

Chen J., Fei Y., Lee P. T.-W., Tao X. (2019). Overseas port investment policy for china’s central and local governments in the belt and road initiative. J. Contemp. China 28, 196–215. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2018.1511392

Chen Y., Yin M. (2018). Discussion on the development of china’s cruise industry under the the belt and road initiative. Foreign Trade Pract. 12, 45–48. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-5559.2018.12.011

Clancy M. (2008). Cruisin’ to exclusion: Commodity chains, the cruise industry, and development in the Caribbean. Globalizations 5, 405–418. doi: 10.1080/14747730802252560

Dowling R., Weeden C. (2017). The world of Cruising. In R. Dowling & C. Weeden (Eds.), Cruise Ship Tourism. 1–39. CABI .doi: 10.1079/9781780646084.0001

Dwyer L., Douglas N., Livaic Z. (2004). ESTIMATING THE ECONOMIC CONTRIBUTION OF a CRUISE SHIP VISIT. Tourism Mar. Environments 1, 5–16. doi: 10.3727/154427304774865841

Gibson P. (2018). Cruise operations management: Hospitality perspectives. doi: 10.4324/9781315146485

He H. (2015). Discussion on policy and legal issues of cruise industry development. Law Soc. London: Routledge. 33, 148–149. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-0592.2015.33.075

Hung K., Wang S., Denizci Guillet B., Liu Z. (2019). An overview of cruise tourism research through comparison of cruise studies published in English and Chinese. Int. J. Hospitality Manage. 77, 207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.06.031

Johnson D. (2002). Environmentally sustainable cruise tourism: a reality check. Mar. Policy 26, 261–270. doi: 10.1016/S0308-597X(02)00008-8

Kowalczyk U. (2018). Growth perspectives for the europe’s shipbuilding industry in the context of world economy trends and competition from Asian shipyards. Biuletyn Instytutu Morskiego w Gdańsku 33, 159–171. doi: 10.5604/01.3001.0012.8065

Li H., Meng S., Tong H. (2021b). How to control cruise ship disease risk? inspiration from the research literature. Mar. Policy 132. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104652

Li X., Yan C. (2013). Several policy and legal issues on the development of china’s cruise industry. Chin. J. Maritime Law 24, 48–53. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-7659.2013.03.007

Li H., Zhang P., Tong H. (2021a). The dilemma of charter sales in the Chinese cruise market: Formation mechanisms and countermeasures. Maritime Technol. Res. 3, 223–236. doi: 10.33175/mtr.2021.247707

Liu W., Liu H., Wang N. (2011). The development of international cruise industry in zhoushan islands – based on the perspective of industrial chain. Port Economy 5, 48–51.

Ma M.-Z., Fan H.-M., Zhang E.-Y. (2018). Cruise homeport location selection evaluation based on grey-cloud clustering model. Curr. Issues Tourism 21, 328–354. doi: 10.1080/13683500.2015.1083951

Pallis T. (2015). Cruise shipping and urban development: State of the art of the industry and cruise ports (Paris: OECD). doi: 10.1787/5jrvzrlw74nv-en

Qian Y., Wang H., Ye X. (2021). Beijing: China Cruise industry development report. Soc. Sci. Literature Press.

Qin X., Wang L. (2019). Environmental protection policy response and evolution of cruise shipping pollution. Logistics Sci-Tech 42, 29–31. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-3100.2019.04.009

Rodrigue J.-P., Notteboom T. (2013). The geography of cruises: Itineraries, not destinations. Appl. Geogr. 38, 31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2012.11.011

Ros Chaos S., Pallis A. A., Saurí Marchán S., Pino Roca D., Sánchez-Arcilla Conejo A. (2021). Economies of scale in cruise shipping. Marit Econ Logist 23, 674–696. doi: 10.1057/s41278-020-00158-3

Small M., Oxenford H. (2022). Impacts of cruise ship anchoring during COVID-19: Management failures and lessons learnt. Ocean Coast. Manage. 229. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2022.106332

Sun X., Feng X., Gauri D. K. (2014). The cruise industry in China: Efforts, progress and challenges. Int. J. Hospitality Manage. 42, 71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.05.009

Sun X., Lin B. (2021). The tangible hand of china’s cruise industry: policy innovation and industrial evolution. Tourism Sci. 35 (6), 67–91. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-575X.2021.6.lvykx202106005

Sun R., Xinliang Y. E., Hong X. U., Management, S. O (2016). Low price dilemma”in China cruise market : Analysis on the price formation mechanism. tourism tribune 31, 107–116. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-5006.2016.11.016

Syriopoulos T., Tsatsaronis M., Gorila M. (2020). The global cruise industry: Financial performance evaluation. Res. Transportation Business Manage. 45, 100558. doi: 10.1016/j.rtbm.2020.100558

Tanaka K. (2011). Review of policies and measures for energy efficiency in industry sector. Energy Policy 39, 6532–6550. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2011.07.058

Wang H., Shi J., Ye X., Wang Y., Mei J. (2018). China’s cruise industry in 2016–2017: Transformation, upgrading and steady development. Rep. China’s Cruise Industry, 1–47. doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-8165-1_1

Wang H., Su P., Ye X., Mei J. (2020). Research on the developments in china’s cruise industry in 2018–2019: The development of whole industry chain of the cruise economy has substantially taken off. Rep. Dev. Cruise Industry China (2019), 29–79. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-4661-7_2

Xiao G., Cui W. (2023). Evolutionary game between government and shipping companies based on shipping cycle and carbon quota. Front. Mar. Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1132174

Xie. X. (2020). Routes and countermeasures for cruise Lines to respond to outbreak epidemics. China Ocean Shipping 3, 48–52. doi: Cnki:sun:yyhw.0.2020-03-024

Xie X. (2022). How to create a “rooted” business environment for the cruise industry. China Ocean Shipping 8, 68–71. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-6664.2022.08.018

Zhang H., Wang Q., Chen J., Rangel-Buitrago N., Shu Y. (2022). Cruise tourism in the context of COVID-19: Dilemmas and solutions. Ocean Coast. Manage. 228. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2022.106321

Keywords: cruise tourism, industrial upgrading, policy, evolution, cruise industry

Citation: Tong H, Chen S and Li H (2023) Policy-driven or market-driven? A new perspective on the development of China’s cruise industry. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1131919. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1131919

Received: 26 December 2022; Accepted: 17 March 2023;

Published: 27 March 2023.

Edited by:

Jihong Chen, Shenzhen University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yusheng Zhou, Nanyang Technological University, SingaporeCopyright © 2023 Tong, Chen and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Helong Tong, aGx0b25nQHNobXR1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.