- 1The Lyell Centre, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- 2Scottish Marine Animal Stranding Scheme, School of Biodiversity, One Health and Veterinary Medicine, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom

- 3Department of Natural Sciences, National Museums Scotland, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- 4School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

- 5Department of Earth Sciences, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada

- 6National Environmental Isotope Facility, Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre, Glasgow, United Kingdom

- 7Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Dolphins are mobile apex marine predators. Over the past three decades, warm-water adapted dolphin species (short-beaked common and striped) have expanded their ranges northward and become increasingly abundant in British waters. Meanwhile, cold-water adapted dolphins (white-beaked and Atlantic white-sided) abundance trends are decreasing, with evidence of the distribution of white-beaked dolphins shifting from southern to northern British waters. These trends are particularly evident in Scottish waters and ocean warming may be a contributing factor. This mobility increases the likelihood of interspecific dietary overlap for prey among dolphin species previously separated by latitude and thermal gradients. Foraging success is critical to both individual animal health and overall population resilience. However, the degree of dietary overlap and plasticity among these species in the Northeast Atlantic is unknown. Here, we characterise recent (2015-2021) interspecific isotopic niche and niche overlap among six small and medium-sized delphinid species co-occurring in Scottish waters, using skin stable isotope composition (δ13C and δ15N), combined with stomach content records and prey δ13C and δ15N compiled from the literature. Cold-water adapted white-beaked dolphin have a smaller core isotopic niche and lower dietary plasticity than the generalist short-beaked common dolphin. Striped dolphin isotopic niche displayed no interspecific overlap, however short-beaked common dolphin isotopic niche overlapped with white-beaked dolphin by 30% and Atlantic white-sided dolphin by 7%. Increasing abundance of short-beaked common dolphin in British waters could create competition for cold-water adapted dolphin species as a significant portion of their diets comprise the same size Gadiformes and high energy density pelagic schooling fish. These priority prey species are also a valuable component of the local and global fishing industry. Competition for prey from both ecological and anthropogenic sources should be considered when assessing cumulative stressors acting on cold-water adapted dolphin populations with projected decline in available habitat as ocean temperatures continue to rise.

1 Introduction

As apex predators, cetaceans (whales, porpoises, and dolphins) are considered valuable indicators of marine ecosystem health (Bossart, 2011; Williamson et al., 2021; Williams et al., 2023). Their ecology and conservation are currently topics of global concern (Burgener et al., 2012; Penniman et al., 2018). Limited baseline information on these charismatic mammals means that novel monitoring tools and long-term data are crucial to assess cetacean population conservation status and inform marine management decisions. Among a multitude of other anthropogenic stressors (e.g., by-catch, noise pollution, persistent organic pollutants), climate change poses an active threat to cetacean populations in the Northeast Atlantic (Jepson et al., 2016; Erbe et al., 2018; Gordon, 2018; Albouy et al., 2020; Evans and Waggitt, 2020). Warming ocean temperatures since ~1980 are altering marine species distribution around Britain and impact cetacean population health through changes in habitat availability, pathogen exposure, and prey abundance (Robinson et al., 2010; Heath et al., 2012; Evans and Bjørge, 2013; Lambert et al., 2014; Hammond et al., 2017; Simmonds, 2017; IJsseldijk et al., 2018; Evans and Waggitt, 2020). Globally, warming sea surface temperatures actively shrink available habitat of cold-water adapted cetaceans and their prey, while warm-water adapted species can shift their ranges towards the poles (Higdon and Ferguson, 2009; Kovacs et al., 2011; Kerosky et al., 2012; Hastings et al., 2020; Chaudhary et al., 2021). This can result in range overlap and competition among marine species (including cetaceans and their prey) previously separated by habitat or latitude (Milazzo et al., 2013; Albouy et al., 2020; Evans and Waggitt, 2020).

Dolphins are highly mobile and are theoretically able to relocate to pursue preferred prey or seek more favourable habitat and water temperatures (Silva et al., 2008; Pinsky et al., 2020). Their mobility, abundance in British waters, and relevant ecologies (differing thermal tolerances and feeding specialisations) render them excellent “sentinels” for changing marine environmental conditions (Williamson et al., 2021). However, this adaptability has also resulted in increased geographical range overlap among dolphin species previously separated by latitude and thermal gradients (Sunday et al., 2012; Williamson et al., 2021).

Historical stranding and sighting data since ~1800 show that Atlantic white-sided and white-beaked dolphins (Leucopleurus acutus and Lagenorhynchus albirostris) are two of the most common cetaceans in British waters, whereas striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba) were rarely recorded in British waters prior to the 1980s (Reid et al., 1993; Sheldrick et al., 1994; Coombs et al., 2019). short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphis) are historically present in British waters, with evidence of a west-to-east and northward shift in population distribution during the early to mid-twentieth century (Murphy et al., 2013). There is a clear increase over the past three decades (1980 to 2020) in the frequency of both short-beaked common and striped dolphin sighting and stranding events in British waters (Paxton and Thomas, 2010; Evans and Waggitt, 2020; Williamson et al., 2021). This trend is particularly notable in northern regions such as Scotland (Waggitt et al., 2020; Williamson et al., 2021). Meanwhile, white-beaked dolphin abundance in the North Atlantic has decreased over the past three decades, and Atlantic white-sided dolphin abundance has decreased since the early 2000s (Evans and Waggitt, 2020). Future ocean warming predicts severe decline in available habitat and white-beaked dolphin abundance over the next century (Lambert et al., 2014).

In British waters, recent and increasing degrees of range overlap between sentinel cold-water adapted dolphins (Atlantic white-sided and white-beaked) and warm-water adapted dolphins (short-beaked common and striped) increases the likelihood of interspecific dietary overlap and the potential for competition. Foraging success is critical to animal health and fecundity (IJsseldijk et al., 2021). As such, foraging pressure introduced from new sources of dietary overlap may have a negative impact on already stressed populations. Stomach content records from these four sentinel dolphin species indicate overlap in preferred prey (Couperus, 1997; Lahaye et al., 2005; Spitz et al., 2006; Canning et al., 2008; Santos et al., 2008; Brophy et al., 2009; Jansen et al., 2010). However, the degree of dietary overlap and plasticity of these species in the Northeast Atlantic is unknown. In addition, these sentinel dolphin species overlap geographically with two other cosmopolitan medium-sized delphinids, Risso’s and bottlenose dolphins (Grampus griseus and Tursiops truncatus) that potentially utilise the same resources (Clarke and Pascoe, 1985; Santos et al., 2001; Spitz et al., 2011).

Carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes (δ13C and δ15N) are used as a proxy for dietary niche in elusive and highly mobile marine mammals. In an isotopic sense, “you are what/where you eat”, with predictable enrichment factors in both δ13C and δ15N associated with trophic level increase (DeNiro and Epstein, 1978; DeNiro and Epstein, 1981). The spatial distribution of marine habitats (latitude and water depth) also has a strong influence on primary producer δ13C, the effects of which are carried up the food chain by consumers (Magozzi et al., 2017; Espinasse et al., 2022). Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope compositions of consumer proteinaceous tissues (such as skin) are directly correlated with diet, providing proxy evidence of nutrient flow within a marine ecosystem as well as trophic position (Madgett et al., 2019; Parzanini et al., 2019; MacKenzie et al., 2022). The trophic enrichment factor between diet (prey muscle) and dolphin skin is approximately 1 ‰ for δ13C and 1.5 ‰ for δ15N (Browning et al., 2014; Giménez et al., 2016). Cetacean skin is a metabolically active tissue, with a half-life of approximately 24.2 (SD ± 8.2) days for carbon and 47.6 (SD ± 19.0) days for nitrogen as documented in captive bottlenose dolphins fed a controlled diet over a one-year period (Giménez et al., 2016). As in similar odontocete studies (e.g., Samarra et al., 2017; Louis et al., 2018), we assume a similar tissue turn-over rate among all six dolphin species, where skin δ13C and δ15N are representative of the diet assimilated during the last 4 to 6 weeks of life. However, the age of the animal and diet lipid-content also have a significant effect on isotopic turn-over rate in dolphin skin (Browning et al., 2014). In contrast with skin stable isotope composition, stomach content analysis is heavily biased towards the final meal of the animal which may not be wholly representative of the species in by-caught or stranded animals (Barros and Odell, 1990; Gibbs et al., 2011). Stomach content analysis is typically limited to prey species that possess distinguishable hard parts (e.g., otoliths, squid beaks), leading to an underrepresentation of soft-bodied or small prey. Pairing cetacean stomach content records with skin stable isotope data therefore provides a more complete picture of cetacean diet (McCluskey et al., 2021).

This study characterises and visualises current interspecific isotopic overlap among six small and medium-sized delphinid species co-occurring in Northeast Atlantic waters. To do so, we combined dolphin skin stable isotope (δ13C and δ15N) data from stranding events (2015-2021) along the Scottish coastline with published stomach content records of individuals fromthe Northeast Atlantic. Dolphin skin δ13C and δ15N allow us to identify isotopic niche size and position, as well as dietary plasticity and potential sources of overlap (Newsome et al., 2007). Based on current stomach content records, we hypothesise that there will be significant isotopic overlap between the striped and the Atlantic white-sided dolphin, and between the short-beaked common and the white-beaked dolphin. This exploratory work on interspecific isotopic niche overlap will improve our understanding of the ecology, interactions, and conservation requirements of sentinel cetacean species in Scottish waters. Specific calls for further research pertaining to diet composition, threats to current populations, lack of data, and likely impact of projected climate change on cold-water dolphin species in British waters highlight the timeliness of this work (Lambert et al., 2014; Evans, 2018; IJsseldijk et al., 2018; Kiszka and Braulik, 2018).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample collection and preparation

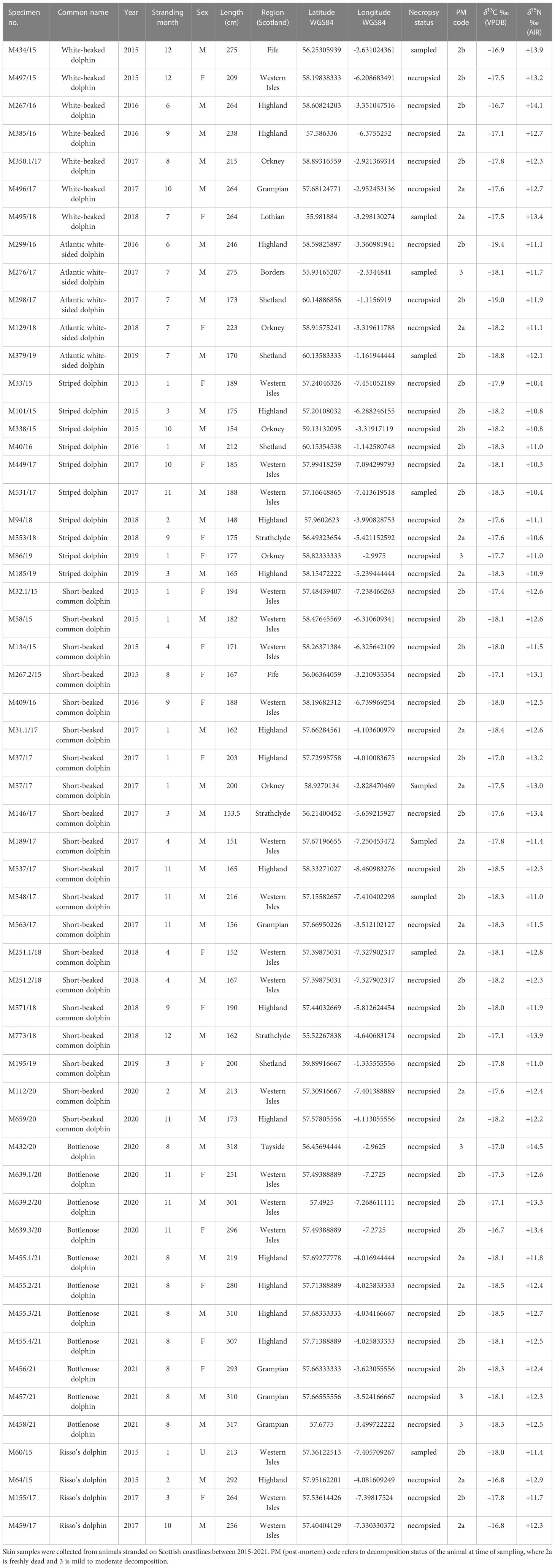

Skin samples were collected from six species of stranded dead dolphins (Atlantic white-sided; white-beaked; short-beaked common; striped; Risso’s; and bottlenose) found on the Scottish coastline between 2015 and 2021. Bottlenose dolphins were assigned a “local” or “non-local” classification based on their presence in photo identification databases for Great Britain and Ireland. Associated stranding event data are reported in Table 1. Skin samples are routinely collected during post-mortem examinations conducted by the Scottish Marine Animal Stranding Scheme (IJsseldijk et al., 2019; Davison and ten Doeschate, 2020) and stored at –20°C in dedicated SMASS and National Museums Scotland (NMS) tissue archives until preparation for analysis. Calves and very young animals primarily reliant on nursing for nutrition were excluded from the analysis based on their body length measurements (Jefferson et al., 1993; Kinze et al., 1997; Kastelein et al., 2003; Jefferson et al., 2008; Meissner et al., 2012; Peters et al., 2020) (Supplementary Material Table 1). Therefore, the animals included in this study are a combination of both adults and nutritionally independent juveniles. Stranding events were selected from the north, east, and west coasts of Scotland, including the Orkney and Shetland Isles. To control for degradation effects, specimens were selected based on carcass condition at time of tissue collection. The majority of samples were classified as 2a to 2b: “freshly dead” to “slight decomposition” (Table 1) (Kuiken, 1991; Payo-Payo et al., 2013; IJsseldijk et al., 2019).

2.2 Lipid extraction and lipid correction for skin δ13C

Lipids have a strong influence on tissue δ13C (DeNiro and Epstein, 1977; Post et al., 2007). Lipids are 13C-depleted relative to protein and should be removed to reduce variability caused by differing lipid content among individuals and species (McConnaughey and McRoy, 1979; Post et al., 2007). While dual analysis of samples is recommended, this can be labour intensive and cost-prohibitive with large sample sets. One aliquot of each sample (n = 57) underwent no lipid extraction to avoid the deleterious effect of chemical extraction on collagen amino acids and its impact onresultant δ15N (Smith et al., 2020). A subset of dolphin skin samples (n = 37) was separated into two aliquots, where one aliquot was chemically lipid extracted to accurately calculate skin lipid content and account for its impact on the proteinaceous component of the remaining non-lipid extracted samples (McConnaughey and McRoy, 1979; Post et al., 2007). Following a modified Bligh and Dyer (1959) method, the lipid extracted aliquot underwent three rinses of 30 minutes each in 10 mL of 2:1 chloroform:methanol, prior to drying at 60°C. Dolphin skin samples were desiccated at 60°C, powdered, and weighed into pressed-tin capsules.

The following equation, adapted to this dataset and following Post et al. (2007), was used to correct the remaining non-lipid extracted (NLE) dolphin δ13C values (Figure 1 and Supplementary Material Table 2):

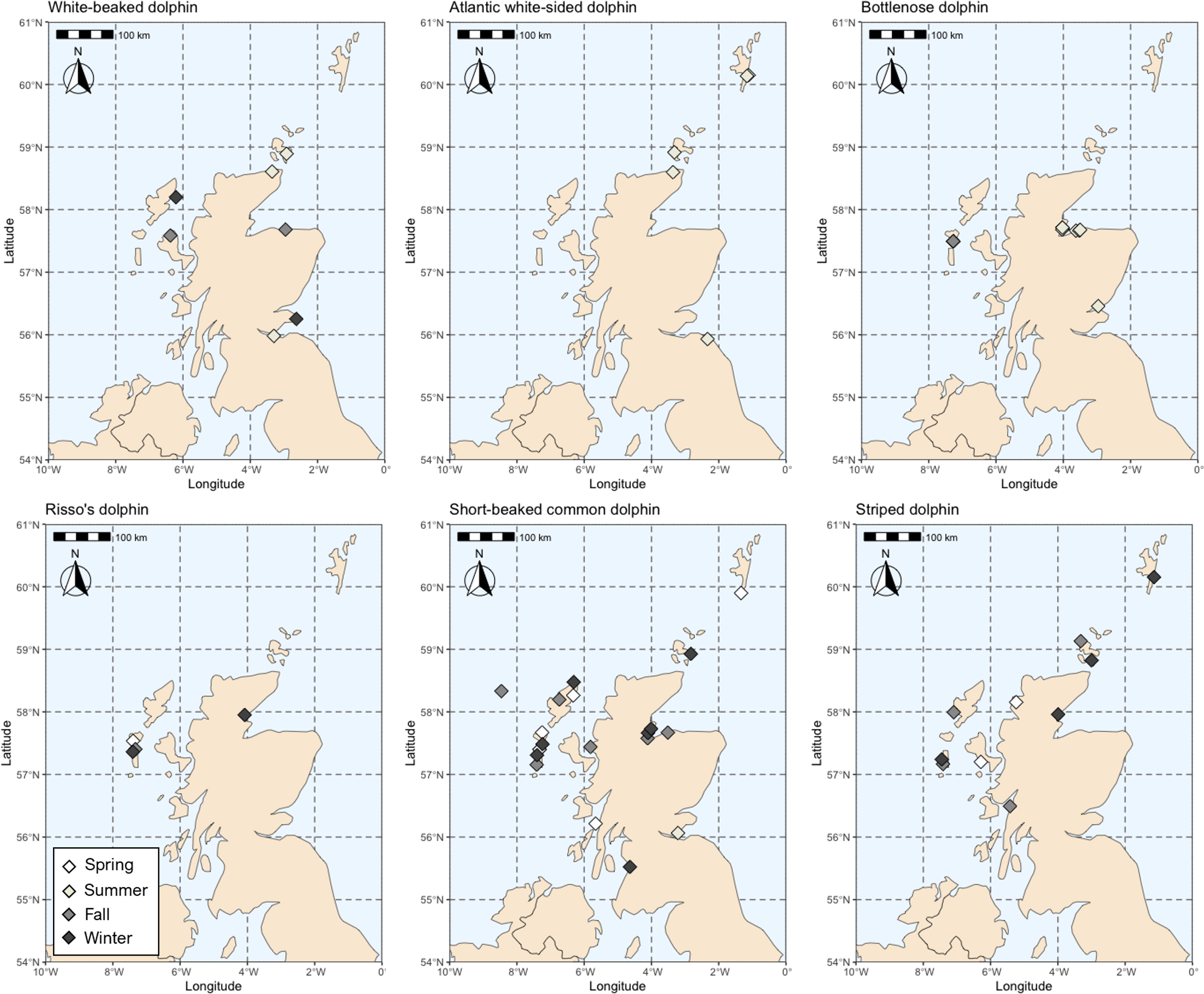

Figure 1 Stranding locations (Scottish coastline) of each dolphin species. Stranding season is also indicated (Spring [March-May], Summer [June-August], Fall [September-November], and Winter [December-February).

where α is the intercept of regression between Δ13CLE-NLE and C:NNLE, and β is the slope (Supplementary Material Table 2):

2.3 Stable isotope analysis

The carbon and nitrogen stable isotope compositions (δ13C and δ15N) of dolphin skin (n = 50) were measured using an Elementar Pyrocube elemental analyser (EA), coupled to a ThermoScientific™ Delta Plus XP isotope mass spectrometer via a ConFlo IV system, using helium as the carrier gas at the National Environmental Isotope Facility (NIEF) isotope ecology laboratory. Additional (n = 7) bottlenose dolphin samples were analysed using a Costech elemental analyser coupled to a ThermoScientific™ Delta V isotope ratio mass spectrometer via a ConFlo IV system, using helium as the carrier gas at the Laboratory for Stable Isotope Science (LSIS) at the University of Western Ontario. Sample duplicates were included for every ten samples. All isotope results are reported in δ-notation in per mil (‰) relative to international standards calibrated to VPDB and AIR, respectively.

At the NEIF laboratory, carbon and nitrogen stable isotope compositions were calibrated using Fluka gel (porcine gelatine; n = 29; 1σ standard deviation [SD] measured δ13C = 0.15 ‰, accepted δ13C = –20.10 ‰ and 1σ SD δ15N = 0.14 ‰, accepted δ15N = +5.73 ‰) and USGS40 (L-glutamic acid; n = 4; 1σ SD δ13C = 0.2 ‰, accepted δ13C = –26.39 ± 0.04 ‰ and 1σ SD δ15N = 0.2 ‰, accepted δ15N = –4.52 ± 0.06 ‰). Fluka gel, Alagel (alanine and gelatine; n = 11; 1σ SD δ13C = 0.09 ‰, accepted δ13C = – 8.98 ‰ and 1σ SD δ15N = 0.12 ‰, accepted δ15N = +2.29 ‰), and Glygel (glycine and gelatine; n = 11; 1σ SD δ13C = 0.07 ‰, accepted δ13C = –38.47 ‰ and 1σ SD δ15N = 0.11 ‰, accepted δ15N = +23.12 ‰) were used to monitor instrument accuracy, precision, and drift. Fluka gel of different weights were used to monitor instrument linearity. Standards were repeated every ten samples. Analytical error was <0.2 ‰ for both δ13C and δ15N.

At LSIS, standards were analysed at the start and end of each analytical session and after every five samples; no instrumental drift was detected in the analytical sessions. The carbon and nitrogen stable isotope compositions were calibrated using USGS40 (L-glutamic acid; n = 4; 1σ SD δ13C = 0.04 ‰, accepted δ13C = –26.39 ± 0.04 ‰; 1σ SD δ15N = 0.04 ‰, accepted δ15N = –4.52 ± 0.06 ‰) and USGS41a (L-glutamic acid; n = 5; 1σ SD δ13C = 0.04 ‰, accepted δ13C = +36.55 ± 0.08 ‰; 1σ SD δ15N = 0.22 ‰, accepted δ15N = +47.55 ± 0.15 ‰). The accuracy of the calibration curve was tested using the LSIS internal standard (keratin, MP Biomedicals Inc., Cat No. 90211, Lot No. 9966H; n = 20) (measured δ13C = –24.09 ± 0.05 ‰ [1σ SD]; measured δ15N = +6.45 ± 0.13 ‰ [1σ SD]; n = 20 for both), which compared well with its accepted values (δ13C = –24.05 ‰; δ15N = +6.40 ‰; n = 1999 for both). Accuracy was also assessed using P. Szpak’s SRM-14 (polar bear bone collagen; measured δ13C = –13.75 ± 0.03 ‰; measured δ15N = +21.65 ± 0.06 ‰; n = 2 for both), which compared well with its accepted values (δ13C = –13.63 ± 0.09 ‰; accepted δ15N = +21.62 ± 0.28 ‰; n = 794 for both). Sample duplicate analyses differed by an average of 0.08 ‰ for δ13C and 0.20 ‰ for δ15N (n = 7 for both).

2.4 Data analysis

Data analyses were performed using R version 4.2.1 (R Core Team, 2022). Dolphin data distribution was assessed using a Shapiro-Wilk normality test. A PERMANOVA was used to identify differences in mean δ13C and δ15N among species. A post hoc pair-wise comparison (with Bonferroni correction to produce adjusted significance levels) was used to identify which species differed. Welch’s Two Sample t-test (assuming unequal variance) was used to assess intraspecific differences between local and non-local bottlenose dolphins. Dolphin isotopic niches, as represented by skin carbon and nitrogen stable isotope compositions (lipid-corrected δ13C and δ15N), were evaluated using the package SIBER (Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R [Jackson et al., 2011]). SIBER creates isotopic niche models of consumers using Bayesian multivariate normal distributions, calculating core (ellipses constraining 40% of data per species - Standard Ellipse Area corrected for small sample size [SEAc] and Bayesian Standard Ellipse Area [SEAB]) and total (convex hull containing 100% of data per species - Total Area [TA]) isotopic niches, in addition to interspecific core niche overlap.

2.5 Dietary comparison of prey δ13C and δ15N

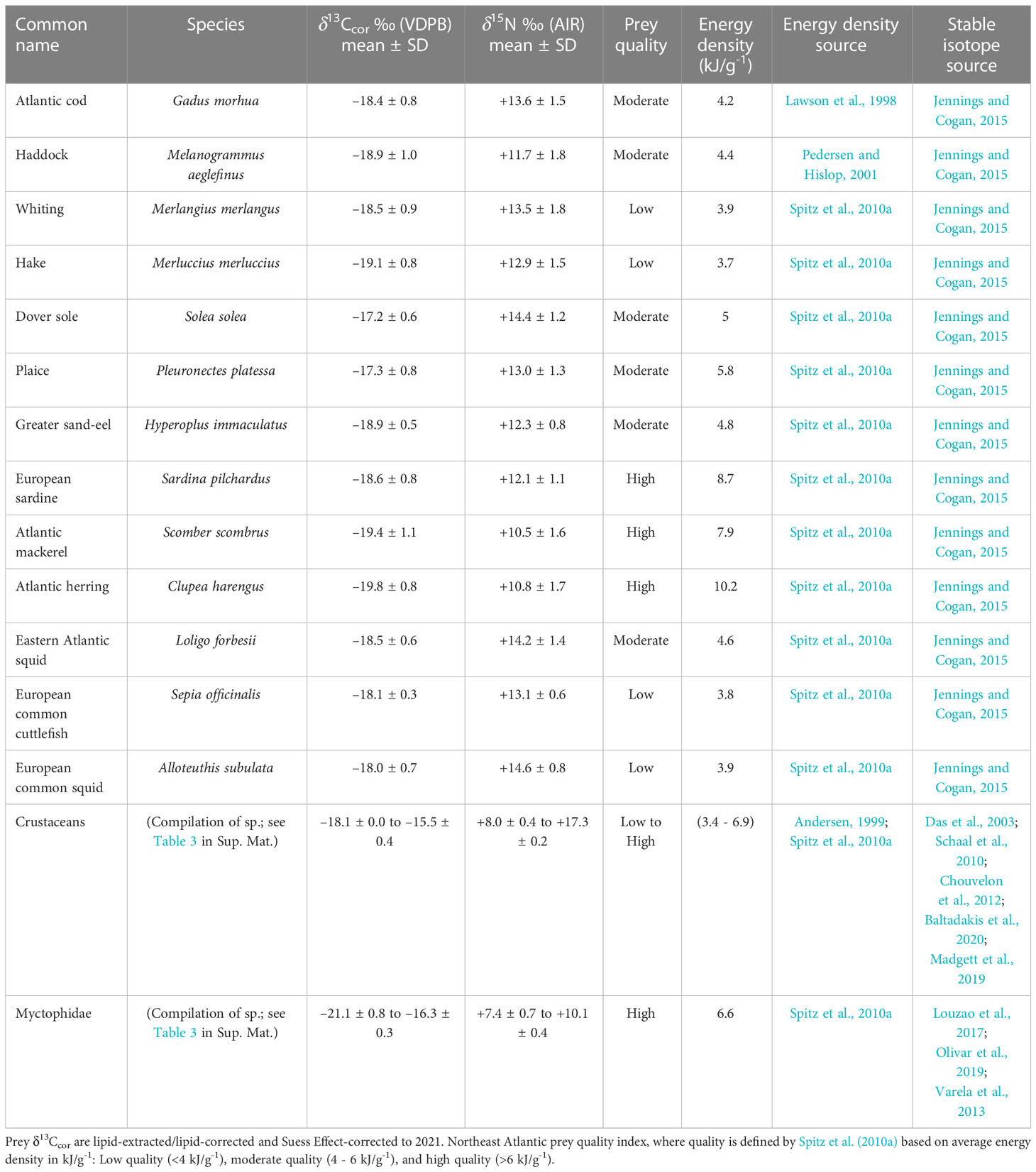

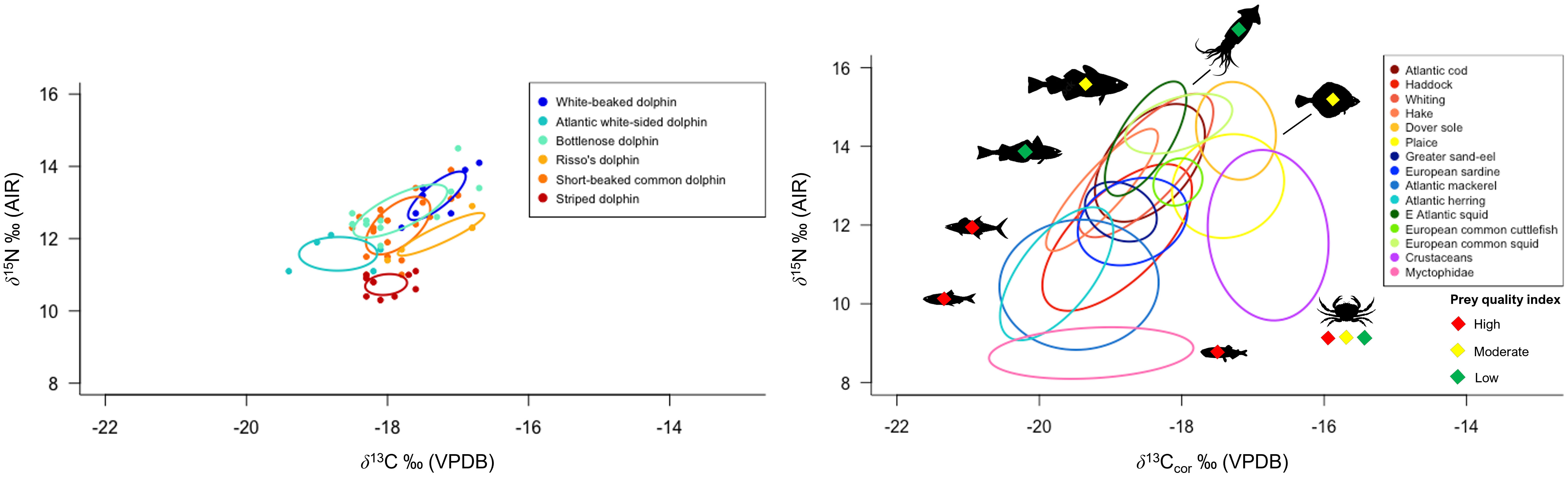

Northeast Atlantic fish, cephalopod, and crustacean muscle δ13C and δ15N (n = 1964 specimens) were compiled to provide additional context for interpreting dolphin diet (Das et al., 2003; Schaal et al., 2010; Chouvelon et al., 2012; Varela et al., 2013; Jennings and Cogan, 2015; Louzao et al., 2017; Madgett et al., 2019; Olivar et al., 2019; Baltadakis et al., 2020) (Figure 2, Table 2; Figure S2 and Supplementary Material Table 3). Prey muscle δ13Ccor has been normalised for lipid content following Post et al. (2007), and Suess Effect-corrected (0.015 ‰ per year) to 2021 (Keeling, 1979; Sonnerup et al., 1999). Information on prey quality (determined by energy density in kJ/g-1) are also presented (Table 2) (Lawson et al., 1998; Andersen, 1999; Pedersen and Hislop, 2001; Spitz et al., 2010a).

Figure 2 Left: Core isotopic feeding niches (as represented by Standard Ellipse Area containing 40% of the data per species, corrected for small sample size [SEAc, ‰2]) of co-occurring dolphin species stranded on Scottish coastlines. Right: Distribution of Northeast Atlantic dolphin prey species δ13Ccor and δ15N. Prey quality (energy density in kJ/g-1) is also indicated. Fish, cephalopod, and crustacean muscle tissue δ13Ccor has been normalised for lipid content following Post et al. (2007) and Suess Effect-corrected to 2021. The trophic enrichment factor between diet (prey muscle) and dolphin skin is approximately 1 ‰ for δ13C and 1.5 ‰ for δ15N.

3 Results

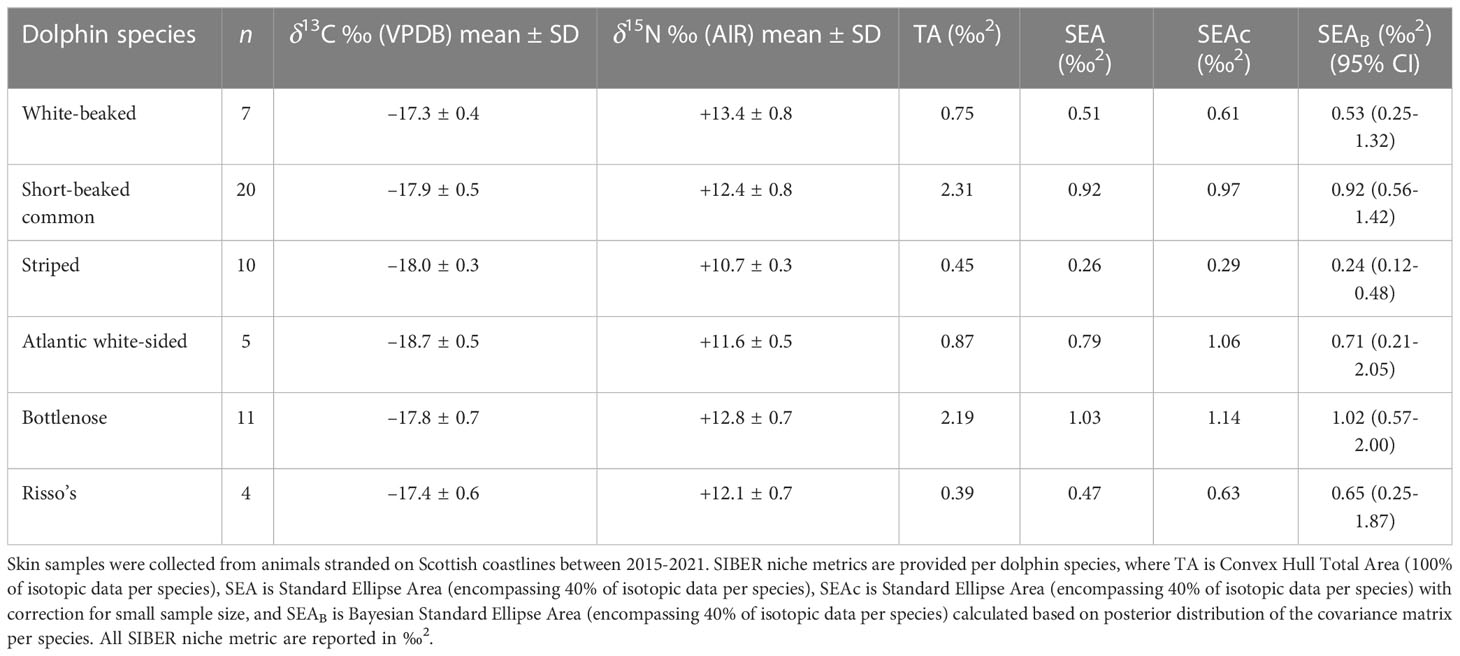

3.1 Dolphin skin stable isotopes

Collectively, dolphin skin δ13C ranged from –19.4 to –16.7 ‰ and δ15N ranged from +10.3 to +14.5 ‰ (Tables 1, 3). White-beaked dolphin (n = 7) had the highest measured δ13C and δ15N, with a mean of –17.3 ± 0.4 ‰ and +13.4 ± 0.8 ‰, respectively. Atlantic white-sided dolphin (n = 5) had the lowest measured δ13C with a mean of –18.7 ± 0.5 ‰, whereas striped dolphin (n = 10) had the lowest δ15N, with a mean of +10.7 ± 0.3 ‰. The data were checked for normality with a Shapiro-Wilk test (δ13C W = 0.96242, p = 0.07395; δ15N W = 0.97528, p = 0.2922). Interspecific variation was identified among dolphin species (PERMANOVA: F = 97.005, p = 0.001) (Supplementary Material Table 4). Pair-wise comparison results with Bonferroni correction are reported in Supplementary Material Table 5. Mean δ13C and δ15N of warm-water adapted species (short-beaked common and striped dolphin) were significantly different from one another (adjusted p-value = 0.015). Likewise, mean δ13C and δ15N of cold-water adapted species (white-beaked and Atlantic white-sided dolphin) were also significantly different (adjusted p-value = 0.03). Striped dolphin mean δ13C and δ15N was significantly different from both white-beaked and Atlantic white-sided dolphin (adjusted p-value = 0.015), whereas common dolphin was not significantly different from either cold-water adapted species due to isotopic overlap.

Table 3 Northeast Atlantic dolphin skin δ13C (lipid-corrected) and δ15N mean and standard deviation (SD).

3.2 Intraspecific isotopic variation

Intraspecific isotopic variation is driven by a number of factors. Within this strandings dataset, there was a higher proportion of male animals for all species. Stranding season also varied by species, where Atlantic white-sided, white-beaked, and bottlenose dolphins stranded most during the summer and autumn months (peak July-September), while striped, short-beaked common, and Risso’s dolphins stranded primarily during the fall and winter months (peak November-March) (Figure 1, Table 1).

Within this dataset, no significant differences (Welch’s Two Sample t-test, short-beaked common dolphin: δ13C t = 1.45, df = 15, p = 0.167, δ15N t = -0.16, df = 16, p = 0.875; bottlenose dolphin: δ13C t = 0.16, df = 8, p = 0.873, δ15N t = -0.44, df = 7, p = 0.671) were found between the δ13C and δ15N of male and female animals for species where n >10. No significant difference (Welch’s Two Sample t-test; t = -0.28, df = 16, p = 0.783; t = -0.65, df = 16, p = 0.522) was observed between δ13C and δ15N of short-beaked common dolphin stranded in the Spring-Summer versus the Fall-Winter periods.

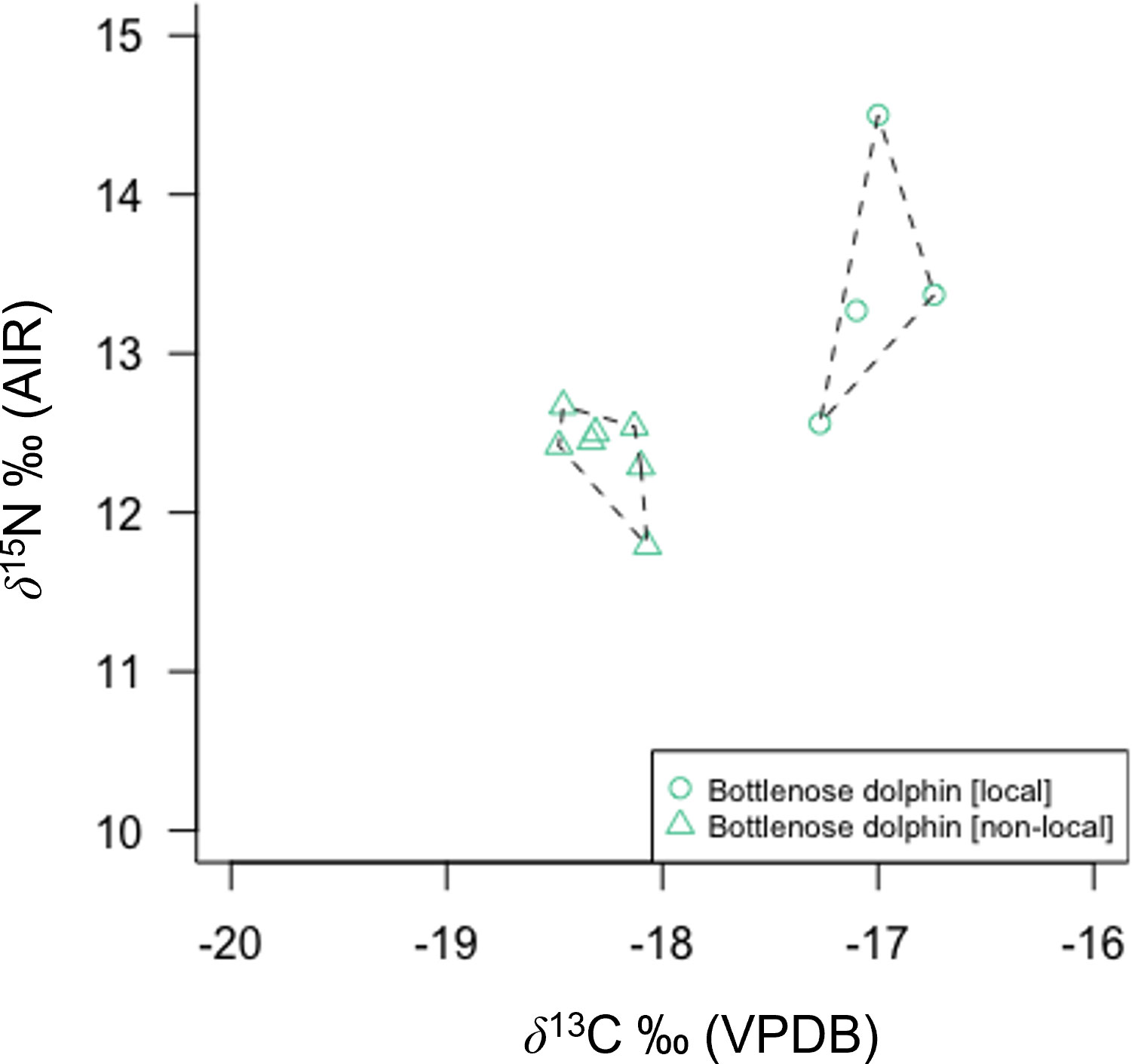

3.3 Isotopic niches and % overlap

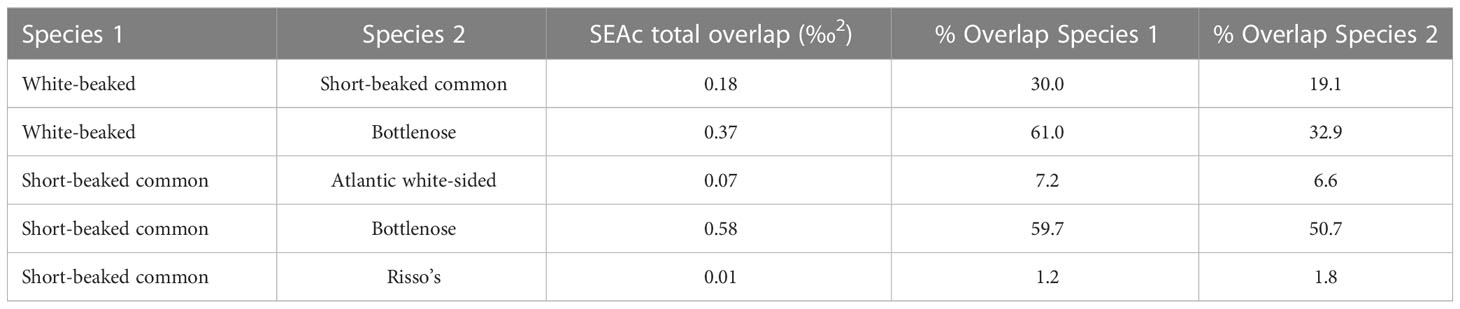

Northeast Atlantic dolphin species stranded in Scottish waters possessed distinct isotopic niches (Figure 2; Supplementary Material Figure 3). Short-beaked common dolphin had the largest total isotopic niche (TA), followed by bottlenose dolphin. Risso’s dolphin had the smallest TA, followed by striped dolphin. Bottlenose dolphin had the largest core isotopic niche (SEAC and SEAB), while striped dolphin had the smallest. Non-local bottlenose dolphins had significantly lower δ13C than known local animals (Welch’s Two Sample t-test; t = 9.68, df = 5.07, p < 0.001) (Figure 3). Five dolphin species displayed some degree of interspecific core niche (SEAc) overlap (Table 4, Figure 2). Short-beaked common dolphin SEAc overlapped with every species, except striped dolphin. Short-beaked common SEAc overlapped with bottlenose dolphin by 51%, with white-beaked dolphin by 30%, and with Atlantic white-sided dolphin by 7%. Striped dolphin was the only species with no interspecific core niche overlap.

Figure 3 Bottlenose dolphin skin δ13C and δ15N from three different stranding events in Scotland show clear regional differences in isotopic composition. Isotopic differentiation is primarily driven by inshore (local pods: Tayside and Western Isles) versus offshore (non-local pod) habitat use.

Table 4 Total (‰2) and per species % overlap of core isotopic niche, as represented by Standard Ellipse Area corrected for small sample size (SEAc).

4 Discussion

4.1 Isotopic niche of dolphins in the Northeast Atlantic

4.1.1 Cold-water adapted species

Of the six Northeast Atlantic dolphin species examined in this study, the white-beaked dolphin occupies the highest isotopic niche. Stomach content records indicate that white-beaked dolphin are food specialists that consume high trophic level fish, although priority prey species vary by region (whiting and cod in the southern North Sea, versus haddock and whiting in northeast Scottish waters). White-beaked dolphin isotopic niche concurs with stomach content records that its diet is dominated by medium to large bodied (20 - 60 cm) pelagic and demersal Gadiformes (e.g., cod, hake, whiting, and haddock) (Kinze et al., 1997; Reeves et al., 1999; Canning et al., 2008; Jansen et al., 2010). Gadiformes are low to moderate quality prey based on energy density (<4 – 6 kJ/g-1) (Table 2) (Spitz et al., 2010a). Squid and high quality (>6 kJ/g-1) pelagic schooling fish (e.g., herring and mackerel) are important secondary prey depending on the region (Reeves et al., 1999; Canning et al., 2008).

The Atlantic white-sided dolphin occupies a lower isotopic niche than the white-beaked dolphin. Their lack of isotopic overlap indicates spatial and trophic segregation of resources. Atlantic white-sided dolphin stomach content records from Irish waters found that medium to small (~30 cm or less) Gadiformes (poor cod, pouting, blue whiting) are priority prey. High quality species like mackerel and mesopelagic fish (Myctophidae and silver pout) also contribute significantly to their overall diet (Hernandez-Milian et al., 2015). Although the Atlantic white-sided dolphin feeds at a lower trophic level and consumes smaller mesopelagic and pelagic prey, it appears to target higher quality prey species than the white-beaked dolphin in Scottish waters (Spitz et al., 2010a).

4.1.2 Warm-water adapted species

The striped dolphin occupies the lowest isotopic niche of all six Northeast Atlantic species. Striped dolphin isotopic niche in Scottish waters suggest that low trophic level, high quality mesopelagic (e.g., Myctophidae) and pelagic schooling fish (e.g., herring and mackerel) are priority prey. Stomach content records from the Bay of Biscay indicate a similar pattern of low trophic level small-bodied (~10-30 cm) prey, where small schooling fish (e.g., blue whiting, whiting, sand smelt) and vertically migrating cephalopods were primarily consumed (Meissner et al., 2012; Spitz et al., 2006).

The short-beaked common dolphin occupies a higher trophic niche than the striped dolphin. It possesses the largest total isotopic niche (TA) of all six studied dolphin species. A large isotopic niche is indicative of opportunistic foraging at various trophic levels and in a variety of spatially distinct habitats. In Scottish waters, their isotopic niche suggests a diet of Gadiformes, pelagic schooling fish, and cephalopods. The intraspecific isotopic variation may be the result of either individual dolphins with specialised diets, or a generalist population. Regardless of foraging strategy, stomach content records indicate that low trophic level high-fat (high quality) schooling fish (e.g., Myctophidae, sardine, anchovy, sprat, and horse mackerel) are critical to its overall energy intake (Pusineri et al., 2007; Meynier et al., 2008; Spitz et al., 2010b).

4.1.3 Cosmopolitan species

Risso’s dolphin occupies a broad isotopic niche of primarily 13C-enriched prey, corresponding with deep-diving foraging behaviour and a diet predominantly composed of squid and octopus from slope and deep-ocean waters (Clarke and Pascoe, 1985; Fabbri et al., 1992; Cañadas et al., 2002; Pereira, 2008; Jefferson et al., 2013; Benoit-Bird et al., 2019; Luna et al., 2022). However, the isotopic niche of Risso’s dolphin suggest that benthic flatfish and high quality schooling pelagic fish may contribute more significantly to their diet than previously reported from stomach contents.

Bottlenose dolphins’ high mean δ13C and δ15N (Figures 2, 3) combined with large TA and SEAc concur with stomach content records of a variable and high trophic level diet. Large-bodied Gadiformes (e.g., cod, whiting, haddock) and Atlantic salmon are known priority prey, in addition to squid and schooling pelagic fish (e.g., herring and sand-eel) (Santos et al., 2001). A wide range of bottlenose skin δ13C concurs with an opportunistic diet and variable habitat use (Walker et al., 1999; Santos et al., 2001; Fernández et al., 2011; Louis et al., 2014). This is particularly evident in the difference between samples from known individuals (based on photo identification databases) belonging to local Scottish coastal pods and a non-local pod (Figure 3). Non-local animals have significantly lower δ13C than local animals, consistent with feeding in an off-shore environment. Opportunistic feeding and habitat segregation have been documented in sympatric Galician bottlenose dolphin populations, where animals foraging in offshore habitat were characterised by lower δ13C than their coastal inlet counterparts (Fernández et al., 2011). In addition, this study identifies potential specialist feeding behaviour in an old (30+ years) male bottlenose dolphin resident to the Tayside region of Eastern Scotland. The animal (M432/20) exhibited very high δ15N (+14.5 ‰) and stomach contents during post mortem examination revealed extensive salmonoid feeding. Combined, this supports the interpretation of an animal that specialised in feeding on high trophic level fish, potentially targeting seasonally available 15N-enriched salmon returning to spawn annually in rivers along the Eastern coastline of mainland Scotland (Sear et al., 2022). Prey specialisation in individuals or local groups have been identified in other bottlenose dolphin populations (Sargeant et al., 2005; McCabe et al., 2010; Allen et al., 2011; McCluskey et al., 2021).

4.2 Interspecific niche interactions and dietary plasticity

Dolphin species isotopic niche confers information about dietary niche, relative trophic level, and habitat use (Figure 2). The two cold-water adapted species (Atlantic white-sided and white-beaked dolphin) have non-overlapping TA and SEAc (Figure 2, Table 3; Supplementary Material Figure 3). White-beaked dolphins target moderate quality, high trophic level prey, while Atlantic white-sided dolphins target high quality, low trophic level prey. Additionally, there is minimal overlap between TA and no overlap among SEAc of warm-water adapted short-beaked common and striped dolphins.

Short-beaked common and striped dolphin core isotopic niches do not overlap in the Northeast Atlantic (Mèndez-Fernandez et al., 2012; this study). The overlap in δ13C, but separation in δ15N in Scottish waters may indicate that they target similar habitat and species, but feed at different trophic levels. Common dolphins may be feeding on many of the same high quality prey species (e.g., Myctophidae, herring, mackerel) as striped dolphins, but simply targeting larger individuals. In contrast, short-beaked common and striped dolphin populations in the north- and southwest Mediterranean Sea exhibit a high degree of isotopic overlap (Giménez et al., 2017; Borrell et al., 2021). However, spatial segregation (deep water versus coastal water use) was observed between the two species, which allowed them to co-exist while exploiting adjacent habitats to avoid competition for prey (Giménez et al., 2017). This spatial and trophic partitioning presumably decreases competition between cetacean species evolved to occupy similar thermal ranges (see also MacKenzie et al., 2022).

Dolphin isotopic niche size and range are correlated with species foraging strategy. Large TA and SEAc typically indicate a consumer with a generalist diet and a high degree of dietary plasticity, whereas small TA and SEAc indicates specialist feeding with minimal plasticity. Striped, white-beaked, and Risso’s dolphins possess the smallest SEAc, indicating low dietary plasticity. Risso’s dolphins’ small SEAc and lack of interspecific isotopic overlap (Table 3) highlight how their specialisation in cephalopod prey help them avoid competition with the other predominantly piscivorous dolphin species (Pusineri et al., 2007; Meynier et al., 2008; Luna et al., 2022). Likewise, striped dolphin SEAc does not overlap with any other species, indicating their specialisation in small, low trophic level (yet high energy density) mesopelagic and pelagic prey. Short-beaked common dolphins are generalists, and their extensive SEAc overlap with bottlenose, white-beaked, and Atlantic white-sided dolphin is likely driven by interspecific consumption of Gadiformes and high energy density pelagic schooling fish. The range and abundance of prey species (notably pelagic schooling fish and cod) in the North Atlantic are highly reactive to ocean warming and nutrient availability (Rose, 2005; van der Kooij et al., 2016; Olafsdottir et al., 2019), with knockdown effects on predator distribution. The high degree of dietary plasticity and increasing abundance of warm-water adapted short-beaked common dolphins in Scottish waters could create future competition for prey among cold-water adapted white-beaked and Atlantic white-sided dolphins. The white-beaked dolphin is considered a food specialist (Jansen et al., 2010), where increasing dietary overlap may pose future challenges as it faces contracting and displaced habitat.

4.3 Competition with fisheries

Based on combined isotopic niche and stomach content records, medium sized Gadiformes and shoaling pelagic fish are the most highly consumed resources among the six Northeast Atlantic dolphin species, eliciting the highest degree of potential interspecific dietary overlap. White-beaked and Atlantic white-sided dolphin preferred prey are also economically important species to United Kingdom fisheries, where pelagic fish (e.g., herring and mackerel) followed by demersal fish (e.g., Gadidae species such as cod and haddock) are the most frequently landed species by UK fisheries (2008-2018) (Elliott and Holden, 2018). There is heavy commercial fishing in Scotland, with a strong impact on regional prey stocks (sometimes resulting in stock crashes), where the highest takes come from areas with the highest observed abundance of white-beaked and Atlantic white-sided dolphins (west of Scotland and the northern North Sea) (Elliott and Holden, 2018). As such, competition for prey from both ecological and anthropogenic sources should be considered when assessing cumulative stressors acting on cold-water adapted dolphin populations.

4.4 Data source considerations

Isotopic variation exists within the data of each analysed dolphin species. This expected variation is driven by a variety of regional, behavioural, and ontogenetic factors. While no significant difference in δ13C and δ15N was observed based on sex or stranding season for short-beaked common and bottlenose dolphins (where n >10), the small sample size of this exploratory study limits further in-depth analyses of other dolphin species. Strandings in cold-water and warm-water adapted dolphin species peaked during the warmer and colder months, respectively (Figure 1). Water temperature significantly impacts dolphin stress response (Houser et al., 2011). The interaction between dolphin thermal preference and thermal stress may play a role in their overall health, prey choice, and stranding incidence in Scottish waters. Future work with an expanded sample set is required to address intraspecific differences and the impact of sex, age class, stranding season, and prey quality in regional populations.

Most intraspecific isotopic variation is likely due to seasonal differences between cetacean stranding events and seasonal changes in diet or prey δ13C and δ15N (for example, Troina et al., 2020a; Troina et al., 2020b). Dolphin habitat choice and foraging patterns can vary with seasonal changes in prey abundance, body size, and quality (McCluskey et al., 2016). Male-female pod segregation and sex-specific caloric requirements and movement patterns during mating and calving seasons may also produce different diets (Canning et al., 2008). Species that experience large-scale seasonal mobility (as documented in Atlantic white-sided dolphins) or a high degree of dietary plasticity (for example, short-beaked common and bottlenose dolphins) consume a wider variety of prey with differing isotopic compositions (Northridge et al., 1997; Santos et al., 2001; Pusineri et al., 2007; Meynier et al., 2008). Adult and juvenile animals of the same species (e.g., white-beaked dolphin) can also consume different prey (Ringelstein et al., 2006; Hernandez-Milian et al., 2015), or prey size may be correlated with body length (as seen in bottlenose dolphins) resulting in clear ontogenetic shifts in diet (Knoff et al., 2008).

Use of tissue samples obtained from stranded animals is a low-cost and opportunistic way to monitor wild cetacean populations. We acknowledge the caveats associated with utilising these samples and their associated data, where cetacean health frequently plays a role in stranding events (Arbelo et al., 2013). The reporting of stranding cases can be biased by a variety of physical and social factors (for example: coastal geography, direction of ocean currents, human population density in coastal area, ease of reporting) (ten Doeschate et al., 2018). In addition, we assume carcass decomposition has not altered the original skin isotopic composition. Payo-Payo et al. (2013) reported no significant change in dolphin skin δ13C and δ15N after 62 days of non-submerged decomposition, applicable to carcass condition code 4 and above. The pressing demand for cetacean ecological information, however, coupled with the extensive challenges associated with collecting live biopsy samples (or tissue from by-caught animals) highlight the continual utility and importance of opportunistic samples taken from stranded animals.

5 Conclusions

This exploratory stable isotope analysis of stranded animals is a highly effective tool to identify and visualise isotopic niche and interspecific dietary overlap among complex cetacean communities. Dolphin species with defined thermal tolerances are useful indicator species for climate change. Over the past three decades, warm-water adapted dolphin species (short-beaked common and striped) have expanded their ranges northward and are increasingly abundant in British waters. Striped dolphin isotopic niche did not overlap with any other species in Scottish waters. However, short-beaked common dolphin isotopic niche overlapped with both cold-water adapted dolphin species. Increasing abundance of short-beaked common dolphin in Scottish waters could create further dietary overlap and potential competition for both white-beaked and Atlantic white-sided dolphins, where a significant portion of their diets comprise the same Gadiformes and high energy density pelagic schooling fish. These priority prey species are also important takes for UK fishery industries.

Dietary overlap with species experiencing northward range expansion should be considered when assessing stressors acting on Atlantic white-sided and white-beaked dolphin populations facing projected decline in available habitat.

From a marine ecosystem and resource monitoring perspective, the combined Atlantic white-sided, short-beaked common, and striped dolphin isotopic niches provide a proxy for mesopelagic, pelagic, and continental shelf habitats. White-beaked and Risso’s dolphin isotopic niches are a proxy for pelagic and deep-water habitats. Local bottlenose dolphin isotopic niche is a proxy for regionally specific inshore coastal habitat. Cetacean monitoring programs would benefit from routine carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis of stranded dolphins to track long-term niche utilisation and evolving interspecific dietary overlap. Ideally, these analyses should be paired with contemporary stomach content analysis of by-caught or stranded individuals.

Combining isotopic niche data with evolving species distribution data and in situ observations of dolphin behaviour in British waters would be a valuable exercise. Not only would it inform if instances of isotopic overlap directly translate to dietary overlap or competition, but also patterns of seasonal resource portioning or new behavioural changes intended to minimise interspecific dietary overlap (Shipley and Matich, 2020).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Samples were acquired from dead stranded animals. No ethics approval required.

Author contributions

TP: Conceptualisation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft. MtD: Conceptualisation, Sample Provision, Data Curation, Writing - Review and Editing. AB: Sample Provision, Writing - Review and Editing. ND: Sample Provision, Writing - Review and Editing. GH: Sample Provision, Writing - Review and Editing. AK: Sample Provision, Writing - Review and Editing. FL: Sample Analysis, Writing - Review and Editing. RM: Sample Analysis, Writing - Review and Editing. CS-N: Software, Writing - Review and Editing. CM: Supervision, Writing - Review and Editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was made possible by funding from the following sources: Heriot-Watt University Scholarship for the School of Energy, Geoscience, Infrastructure & Society joint with the British Geological Society (TP), Marine Scotland (SMASS), NSERC Discovery Grant 05904-2019 RGPIN (FJL), Canada Research Chair X1277C01 (FJL), Canada Research Chair (FJL), NERC (NEIF), and The Negaunee Foundation (NMS).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the SMASS volunteers who assisted with dolphin carcass and sample recovery. Thanks to Genyffer Troina for advice on skin lipid correction. Thanks to Kim Law for technical support and Caillan Mitchell for assistance with sample preparation. This is LSIS contribution #401.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2023.1111295/full#supplementary-material

References

Albouy C., Delattre V., Donati G., Frölicher T. L., Albouy-Boyer S., Rufino M., et al. (2020). Global vulnerability of marine mammals to global warming. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57280-3

Allen S. J., Bejder L., Krutzen M. (2011). Why do indo-pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.) carry conch shells (Turbinella sp.) in Shark Bay, Western Australia? Mar. Mamm. Sci. 27, 449–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2010.00409.x

Andersen N. G. (1999). The effects of predator size, temperature, and prey characteristics on gastric evacuation in whiting. J. Fish Biol. 54 (2), 287–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.1999.tb00830.x

Arbelo M., de Los Monteros A. E., Herráez P., Andrada M., Sierra E., Rodríguez F., et al. (2013). Pathology and causes of death of stranded Cetaceans in the Canary Islands (1999–2005). Dis. Aquat. Org. 103 (2), 87–99. doi: 10.3354/dao02558

Baltadakis A., Casserly J., Falconer L., Sprague M., Telfer T. C. (2020). European Lobsters utilise Atlantic salmon wastes in coastal integrated multi-trophic aquaculture systems. Aquac. Environ. Interact. 12, 485–494. doi: 10.3354/aei00378

Barros N. B., Odell D. K. (1990). “Food habits of bottlenose dolphins in the southeastern United States,” in The bottlenose dolphin. Eds. Leatherwood S., Reeves R. (San Diego: Academic Press).

Benoit-Bird K. J., Southall B. L., Moline M. A. (2019). Dynamic foraging by Risso's dolphins revealed in four dimensions. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 632, 221–234. doi: 10.3354/meps13157

Bligh E. G., Dyer W. J. (1959). A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 37 (8), 911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099

Borrell A., Gazo M., Aguilar A., Raga J. A., Degollada E., Gozalbes P., et al. (2021). Niche partitioning amongst northwestern Mediterranean Cetaceans using stable isotopes. Prog. Oceanogr. 193, 102559. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2021.102559

Bossart G. D. (2011). Marine mammals as sentinel species for oceans and human health. Vet. Pathol. 48 (3), 676–690. doi: 10.1177/0300985810388525

Brophy J., Murphy S., Rogan E. (2009). The diet and feeding ecology of the short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphis) in the northeast Atlantic. IWC Sci. Commun. Doc. SC/61/SM, 14, 1–18.

Browning N. E., Dold C., I-Fan J., Worthy G. A. (2014). Isotope turnover rates and diet–tissue discrimination in skin of ex situ bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). J. Exp. Biol. 217 (2), 214–221. doi: 10.1242/jeb.093963

Burgener V., Eliott W., Leslie A. (2012). WWF species action plan: Cetaceans 2012–2020. Switzerland: WWF. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.14699.54567

Cañadas A., Sagarminaga R., García-Tíscar S. (2002). Cetacean distribution related with depth and slope in the Mediterranean waters off southern Spain. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 49 (11), 2053–2073. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0637(02)00123-1

Canning S. J., Santos M. B., Reid R. J., Evans P. G., Sabin R. C., Bailey N., et al. (2008). Seasonal distribution of white-beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) in UK waters with new information on diet and habitat use. J. Mar. Biolog. Assoc. 88 (6), 1159–1166. doi: 10.1017/S0025315408000076

Chaudhary C., Richardson A. J., Schoeman D. S., Costello M. J. (2021). Global warming is causing a more pronounced dip in marine species richness around the equator. PNAS 118 (15), e2015094118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2015094118

Chouvelon T., Spitz J., Caurant F., Mèndez-Fernandez P., Chappuis A., Laugier F., et al. (2012). Revisiting the use of δ15N in meso-scale studies of marine food webs by considering spatio-temporal variations in stable isotopic signatures–the case of an open ecosystem: the Bay of Biscay (North-East Atlantic). Prog. Oceanogr. 101 (1), 92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2012.01.004

Clarke M. R., Pascoe P. L. (1985). The stomach contents of a Risso's dolphin (Grampus griseus) stranded at Thurlestone, south Devon. J. Mar. Biolog. Assoc. U.K 65 (3), 663–665. doi: 10.1017/S0025315400052504

Coombs E. J., Deaville R., Sabin R. C., Allan L., O'Connell M., Berrow S., et al. (2019). What can cetacean stranding records tell us? a study of UK and Irish cetacean diversity over the past 100 years. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 35 (4), 1527–1555. doi: 10.1111/mms.12610

Couperus A. (1997). Interactions between Dutch midwater trawl and Atlantic white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus acutus) southwest of Ireland. J. Northwest Atl. Fish. Sci. 22, 209–218. doi: 10.2960/J.v22.a16

Das K., Beans C., Holsbeek L., Mauger G., Berrow S. D., Rogan E., et al. (2003). Marine mammals from northeast Atlantic: evaluation of their trophic position by δ13C and δ15N and influence on their trace metal concentrations. Mar. Environ. Res. 56, 349–365. doi: 10.3354/meps263287

Davison N., ten Doeschate M. (2020). Annual report 2020 (1 January to 31 December 2020) for Marine Scotland, Scottish government. Scottish Mar. Anim. Stranding Scheme., 1–87.

DeNiro M. J., Epstein S. (1977). Mechanism of carbon isotope fractionation associated with lipid synthesis. Science 197 (4300), 261–263. doi: 10.1126/science.32754

DeNiro M. J., Epstein S. (1978). Influence of diet on the distribution of carbon isotopes in animals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 42 (5), 495–506. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(78)90199-0

DeNiro M. J., Epstein S. (1981). Influence of diet on the distribution of nitrogen isotopes in animals. geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 45 (3), 341–351. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(81)90244-1

Elliott M., Holden J. (2018). UK Sea Fisheries statistics 2018 (London, UK: Marine Management Organization).

Erbe C., Dunlop R., Dolman S. (2018). “Effects of noise on marine mammals,” in Effects of anthropogenic noise on animals. Eds. Slabbekoorn H., Dooling R., Popper A., Fay R. (New York: Springer), 277–309. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8574-6_10

Espinasse B. D., Sturbois A., Basedow S. L., Hélaouët P., Johns D. G., Newton J., et al. (2022). Temporal dynamics in zooplankton δ13C and δ15N isoscapes for the north Atlantic ocean: decadal cycles, seasonality, and implications for predator ecology. Front. Ecol. Evol. 10. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2022.986082

Evans P. G. H. (2018). North Sea cetacean research since the 1960s: advances and gaps. Lutra 61 (1), 3–13.

Evans P. G. H., Bjørge A. (2013). Impacts of climate change on marine mammals, MCCIP. Sci. Rev., 134–148. doi: 10.14465/2013.arc15.134-148

Evans P. G. H., Waggitt J. (2020). Impacts of climate change on marine mammals, relevant to the coastal and marine environment around the UK. MCCIP Sci. Rev., 421–455. doi: 10.14465/2020.arc19.mmm

Fabbri F., Giordano A., Lauriano G. (1992). “A preliminary investigation into the relationship between the distribution of Risso's dolphin and depth,” in European Research on Cetaceans. Ed. Evans P. G. H. (San Remo, Italy: European Cetacean Society), 6, 146–151.

Fernández R., García-Tiscar S., Begoña Santos M., López A., Martínez-Cedeira J. A., Newton J., et al. (2011). Stable isotope analysis in two sympatric populations of bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus: evidence of resource partitioning? Mar. Biol. 158 (5), 1043–1055. doi: 10.1007/s00227-011-1629-3

Gibbs S. E., Harcourt R. G., Kemper C. M. (2011). Niche differentiation of bottlenose dolphin species in south Australia revealed by stable isotopes and stomach contents. Wildl. Res. 38 (4), 261–270. doi: 10.1071/WR10108

Giménez J., Cañadas A., Ramírez F., Afán I., García-Tiscar S., Fernández-Maldonado C., et al. (2017). Intra-and interspecific niche partitioning in striped and common dolphins inhabiting the southwestern Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 567, 199–210. doi: 10.3354/meps12046

Giménez J., Ramírez F., Almunia J., Forero M. G., de Stephanis R. (2016). From the pool to the sea: applicable isotope turnover rates and diet to skin discrimination factors for bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 475, 54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2015.11.001

Gordon C. (2018). “Anthropogenic noise and cetacean interactions in the 21st century: a contemporary review of the impacts of environmental noise pollution on cetacean ecologies,” in Bachelors honors thesis (Portland (OR: Portland State University). doi: 10.15760/honors.636

Hammond P., Lacey C., Gilles A., Viquerat S., Boerjesson P., Herr H., et al. (2017). Estimates of cetacean abundance in European Atlantic waters in summer 2016 from the SCANS-III aerial and shipboard surveys. Wageningen Mar. Res., 1–39.

Hastings R. A., Rutterford L. A., Freer J. J., Collins R. A., Simpson S. D., Genner M. J. (2020). Climate change drives poleward increases and equatorward declines in Marine species. Curr. Biol. 30 (8), 1572–1577. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.02.043

Heath M. R., Neat F. C., Pinnegar J. K., Reid D. G., Sims D. W., Wright P. J. (2012). Review of climate change impacts on marine fish and shellfish around the UK and Ireland. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 22, 337–367. doi: 10.1002/aqc.2244

Hernandez-Milian G., Begoña Santos M., Reid D., Rogan E. (2015). Insights into the diet of Atlantic white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus acutus) in the northeast Atlantic. Mar. Mammal Sci. 10, 1–8. doi: 10.1111/mms.12272

Higdon J. W., Ferguson S. H. (2009). Loss of Arctic sea ice causing punctuated change in sightings of killer whales (Orcinus orca) over the past century. Ecol. Appl. 19 (5), 1365–1375. doi: 10.1890/07-1941.1

Houser D. S., Yeates L. C., Crocker D. E. (2011). Cold stress induces an adrenocortical response in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). JZWM 42 (4), 565–571. doi: 10.1638/2010-0121.1

IJsseldijk L. L., Brownlow A., Davison N., Deaville R., Haelters J., Keijl G., et al. (2018). Spatiotemporal analysis in white-beaked dolphin strandings along the North Sea coast from 1991-2017. Lutra 61 (1), 153–163.

IJsseldijk L. L., Brownlow A. C., Mazzariol S. (2019). “Best practice on cetacean post-mortem investigation and tissue sampling,” in Joint ACCOBAMS and ASCOBANS document. 1–73. doi: 10.31219/osf.io/zh4ra

IJsseldijk L. L., Hessing S., Mairo A., ten Doeschate M. T., Treep J., van den Broek J., et al. (2021). Nutritional status and prey energy density govern reproductive success in a small cetacean. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-98629-x

Jackson A. L., Inger R., Parnell A. C., Bearhop S. (2011). Comparing isotopic niche widths among and within communities: SIBER–stable isotope Bayesian ellipses in r. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 595–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01806.x

Jansen O. E., Leopold M. F., Meesters E. H., Smeenk C. (2010). Are white-beaked dolphins Lagenorhynchus albirostris food specialists? Their diet in the southern North Sea. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U.K. 90, 1501–1508. doi: 10.1017/S0025315410001190

Jefferson T. A., Leatherwood S., Webber M. A. (1993). Food and agriculture organization of the United Nations identification guide: marine mammals of the world (Rome: FAO).

Jefferson T. A., Webber M. A., Pitman R. L. (2008). Marine mammals of the world: a comprehensive guide to their identification (London: Academic Press).

Jefferson T. A., Weir C. R., Anderson R. C., Ballance L. T., Kenney R. D., Kiszka J. J. (2013). Global distribution of Risso's dolphin Grampus griseus: a review and critical evaluation. Mamm. Rev. 44 (1), 56–68. doi: 10.1111/mam.12008

Jennings S., Cogan S. M. (2015). Nitrogen and carbon stable isotope variation in northeast Atlantic fishes and squids. Ecology 96 (9), 2568. doi: 10.1890/15-0299.1

Jepson P. D., Deaville R., Barber J. L., Aguilar À., Borrell A., Murphy S., et al. (2016). PCB Pollution continues to impact populations of orcas and other dolphins in European waters. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 1–17. doi: 10.1038/srep18573

Kastelein R. A., Staal C., Wiepkema P. R. (2003). Food consumption, food passage time, and body measurements of captive Atlantic bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Aquat. Mamm. 29 (1), 53–66. doi: 10.1578/016754203101024077

Keeling C. D. (1979). The Suess effect: 13Carbon-14Carbon interrelations. Environ. Int. 2, 229–300. doi: 10.1016/0160-4120(79)90005-9

Kerosky S. M., Širović A., Roche L. K., Baumann-Pickering S., Wiggins S. M., Hildebrand J. A. (2012). Bryde's whale seasonal range expansion and increasing presence in the southern California bight from 2000 to 2010. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 65, 125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2012.03.013

Kinze C. C., Addink M., Smeenk C., Hartmann M. G., Richards H. W., Sonntag R. P., et al. (1997). The white-beaked dolphin (Lagenorhynchus albirostris) and the white-sided dolphin (Lagenorhynchus acutus) in the north and Baltic seas: review of available information. Rep. IWC 47, 675–681.

Kiszka J. J., Braulik G. (2018). Lagenorhynchus albirostris - the IUCN red list of threatened species, ISSN 2307-8235.

Knoff A., Hohn A., Macko S. (2008). Ontogenetic diet changes in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) reflected through stable isotopes. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 24 (1), 128–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2007.00174.x

Kovacs K. M., Lydersen C., Overland J. E., Moore S. E. (2011). Impacts of changing sea-ice conditions on Arctic marine mammals. Mar. Biodivers. 41, 181–194. doi: 10.1007/s12526-010-0061-0

Kuiken T. (1991). Proceedings of the first European cetacean society workshop on cetacean pathology: dissection techniques and tissue sampling, Leiden, the Netherlands, 13-14 September 1991 (Stralsund: European Cetacean Society).

Lahaye V., Bustamante P., Spitz J., Dabin W., Das K., Pierce G. J., et al. (2005). Long-term dietary segregation of common dolphins Delphinus delphis in the Bay of Biscay, determined using cadmium as an ecological tracer. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 305, 275–285. doi: 10.3354/meps305275

Lambert E., Pierce G. J., Hall K., Brereton T., Dunn T. E., Wall D., et al. (2014). Cetacean range and climate in the eastern north Atlantic: future predictions and implications for conservation. Glob. Change Biol. 20 (6), 1782–1793. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12560

Lawson J. W., Magalhães A. M., Miller E. H. (1998). Important prey species of marine vertebrate predators in the northwest Atlantic: proximate composition and energy density. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 164, 13–20. doi: 10.3354/meps164013

Louis M., Simon-Bouhet B., Viricel A., Lucas T., Gally F., Cherel Y., et al. (2018). Evaluating the influence of ecology, sex and kinship on the social structure of resident coastal bottlenose dolphins. Mar. Biol. 165 (5), 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00227-018-3341-z

Louis M., Viricel A., Lucas T., Peltier H., Alfonsi E., Berrow S., et al. (2014). Habitat-driven population structure of bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncatus, in the north-East Atlantic. Mol. Ecol. 23 (4), 857–874. doi: 10.1111/mec.12653

Louzao M., Navarro J., Delgado-Huertas A., de Sola L. G., Forero M. G. (2017). Surface oceanographic fronts influencing deep-sea biological activity: using fish stable isotopes as ecological tracers. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 140, 117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2016.10.012

Luna A., Sánchez P., Chicote C., Gazo M. (2022). Cephalopods in the diet of Risso's dolphin (Grampus griseus) from the Mediterranean Sea: a review. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 38 (2), 725–741. doi: 10.1111/mms.12869

MacKenzie K. M., Lydersen C., Haug T., Routti H., Aars J., Andvik C. M., et al. (2022). Niches of marine mammals in the European Arctic. Ecol. Indic. 136, 108661. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.108661

Madgett A. S., Yates K., Webster L., McKenzie C., Moffat C. F. (2019). Understanding marine food web dynamics using fatty acid signatures and stable isotope ratios: improving contaminant impacts assessments across trophic levels. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 227, 106327. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2019.106327

Magozzi S., Yool A., Vander Zanden H. B., Wunder M. B., Trueman C. N. (2017). Using ocean models to predict spatial and temporal variation in marine carbon isotopes. Ecosphere 8 (5), e01763. doi: 10.1002/ecs2.1763

McCabe E. J. B., Gannon D. P., Barros N. B., Wells R. S. (2010). Prey selection by resident common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in Sarasota Bay, Florida. Mar. Biol. 157, 931–942. doi: 10.1007/s00227-009-1371-2

McCluskey S. M., Bejder L., Loneragan N. R. (2016). Dolphin prey availability and calorific value in an estuarine and coastal environment. Front. Mar. Sci. 3. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00030

McCluskey S. M., Sprogis K. R., London J. M., Bejder L., Loneragan N. R. (2021). Foraging preferences of an apex marine predator revealed through stomach content and stable isotope analyses. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 25, e01396. doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01396

McConnaughey T., McRoy C. P. (1979). Food-web structure and the fractionation of carbon isotopes in the Bering Sea. Mar. Biol. 53 (3), 257–262. doi: 10.1007/BF00952434

McMahon K. W., Hamady L. L., Thorrold S. R. (2013). A review of ecogeochemistry approaches to estimating movements of marine animals. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58 (2), 697–714. doi: 10.4319/lo.2013.58.2.0697

Meissner A. M., MacLeod C. D., Richard P., Ridoux V., Pierce G. (2012). Feeding ecology of striped dolphins, Stenella coeruleoalba, in the north-western Mediterranean Sea based on stable isotope analyses. J. Mar. Biolog. Assoc. U.K. 92 (8), 1677–1687. doi: 10.1017/S0025315411001457

Mèndez-Fernandez P., Bustamante P., Bode A., Chouvelon T., Ferreira M., Lopez A., et al. (2012). Foraging ecology of five toothed whale species in the Northwest Iberian peninsula, inferred using carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 413, 150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2011.12.007

Meynier L., Pusineri C., Spitz J., Santos M. B., Pierce G. J., Ridoux V. (2008). Intraspecific dietary variation in the short beaked common dolphin Delphinus delphis in the Bay of Biscay: importance of fat fish. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 354, 277–287. doi: 10.3354/meps07246

Milazzo M., Mirto S., Domenici P., Gristina M. (2013). Climate change exacerbates interspecific interactions in sympatric coastal fishes. J. Anim. Ecol. 82 (2), 468–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2012.02034.x

Murphy S., Pinn E. H., Jepson P. D. (2013). “The short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphis) in the north-East Atlantic: distribution, ecology, management and conservation status,” in Oceanography and marine biology: an annual review. Eds. Hughes N., Hughes D. J., Smith I. P. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press), 193–280. doi: 10.1201/b15406

Newsome S. D., Martinez del Rio C., Bearhop S., Phillips D. L. (2007). A niche for isotopic ecology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 5 (8), 429–436. doi: 10.1890/060150.1

Northridge S., Tasker M., Webb A., Camphuysen K., Leopold M. (1997). White-beaked Lagenorhynchus albirostris and Atlantic white-sided dolphin L. acutus distributions in northwest European and US north Atlantic waters. Rep. ICW 47, 797–805.

Olafsdottir A. H., Utne K. R., Jacobsen J. A., Jansen T., Óskarsson G. J., Nøttestad L., et al. (2019). Geographical expansion of northeast Atlantic mackerel (Scomber scombrus) in the Nordic seas from 2007 to 2016 was primarily driven by stock size and constrained by low temperatures. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 159, 152–168. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2018.05.023

Olivar M. P., Bode A., López-Pérez C., Hulley P. A., Hernández-León S. (2019). Trophic position of lanternfishes (Pisces: myctophidae) of the tropical and equatorial Atlantic estimated using stable isotopes. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 76 (3), 649–661. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsx243

Parzanini C., Parrish C. C., Hamel J. F., Mercier A. (2019). Reviews and syntheses: insights into deep-sea food webs and global environmental gradients revealed by stable isotope (δ15N, δ13C) and fatty acid trophic biomarkers. Biogeosciences 16 (14), 2837–2856. doi: 10.5194/bg-16-2837-2019

Paxton C. G. M., Thomas L. (2010). Phase I data analysis of joint cetacean protocol data. report to joint nature conservation committee on JNCC contract no. C09-0207-0216 (St. Andrews, UK: Centre for Research into Ecological and Environmental Modelling, University of St. Andrews).

Payo-Payo A., Ruiz B., Cardona L., Borrell A. (2013). Effect of tissue decomposition on stable isotope signatures of striped dolphins Stenella coeruleoalba and loggerhead sea turtles Caretta caretta. Aquat. Biol. 18 (2), 141–147. doi: 10.3354/ab00497

Pedersen J., Hislop J. R. G. (2001). Seasonal variations in the energy density of fishes in the North Sea. J. Fish Biol. 59 (2), 380–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2001.tb00137.x

Penniman T., Jackson L. C., Nyingi D. W. (2018). Nineteenth meeting of the United Nations open ended informal consultative process on oceans and the law of the Sea: 18-22 June 2018 Vol. 25 (New York: United Nations headquarters), 1–12.

Pereira J. N. D. (2008). Field notes on Risso's dolphin (Grampus griseus) distribution, social ecology, behaviour, and occurrence in the Azores. Aquat. Mamm. 34 (4), 426. doi: 10.1578/AM.34.4.2008.426

Peters K. J., Bury S. J., Betty E. L., Parra G. J., Tezanos-Pinto G., Stockin K. A. (2020). Foraging ecology of the common dolphin Delphinus delphis revealed by stable isotope analysis. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 652, 173–186. doi: 10.3354/meps13482

Pinsky M. L., Selden R. L., Kitchel Z. J. (2020). Climate-driven shifts in marine species ranges: scaling from organisms to communities. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 12, 153–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-010419-010916

Post D. M., Layman C. A., Arrington D. A., Takimoto G., Quattrochi J., Montana C. G. (2007). Getting to the fat of the matter: models, methods and assumptions for dealing with lipids in stable isotope analyses. Oecologia 152 (1), 179–189. doi: 10.1007/s00442-006-0630-x

Pusineri C., Magnin V., Meynier L., Spitz J., Hassani S., Ridoux V. (2007). Food and feeding ecology of the common dolphin (Delphinus delphis) in the oceanic northeast Atlantic and comparison with its diet in neritic areas. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 23, 30–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00088.x

R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/

Reeves R. R., Smeenk C., Kinze C. C., Brownell R. L., Lien J., Ridgway S. H., et al. (1999). “White-beaked dolphin Lagenorhynchus albirostris,” in Handbook of marine mammals: the second book of dolphins and the porpoises. Eds. Ridgway S. H., Harrison R. J. (London: Academic Press), 1–30.

Reid R. J., Kitchener A., Ross H. M., Herman J. (1993). First records of the striped dolphin, Stenella coeruleoalba, in Scottish waters. Glasg. Nat. 22, 243–245.

Ringelstein J., Pusineri C., Hassani S., Meynier L., Nicolas R., Ridoux V. (2006). Food and feeding ecology of the striped dolphin, Stenella coeruleoalba, in the oceanic waters of the north-east Atlantic. J. Mar. Biolog. Assoc. U.K. 86 (4), 909–918. doi: 10.1017/S0025315406013865

Robinson K. P., Eisfeld S. M., Costa M., Simmonds M. P. (2010). Short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphis) occurrence in the Moray Firth, north-east Scotland. Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 3, e55. doi: 10.1017/S1755267210000448

Rose G. A. (2005). On distributional responses of north Atlantic fish to climate change. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 62 (7), 1360–1374. doi: 10.1016/j.icesjms.2005.05.007

Samarra F. I., Vighi M., Aguilar A., Víkingsson G. A. (2017). Intra-population variation in isotopic niche in herring-eating killer whales off Iceland. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 564, 199–210. doi: 10.3354/meps11998

Santos M. B., Pierce G., Learmonth J., Reid R., Sacau M., Patterson I., et al. (2008). Strandings of striped dolphin Stenella coeruleoalba in Scottish waters (1992–2003) with notes on the diet of this species. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U.K. 88, 1175–1183. doi: 10.1017/S0025315408000155

Santos M. B., Pierce G. J., Reid R. J., Patterson I. A. P., Ross H. M., Mente E. (2001). Stomach contents of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in Scottish waters. J. Mar. Biolog. Assoc. U.K. 81 (5), 873–878. doi: 10.1017/S0025315401004714

Sargeant B. L., Mann J., Berggren P., Krutzen M. (2005). Specialization and development of beach hunting, a rare foraging behavior, by wild bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.). Can. J. Zool. Rev. Can. Zool. 83, 1400–1410. doi: 10.1139/z05-136

Schaal G., Riera P., Leroux C., Grall J. (2010). A seasonal stable isotope survey of the food web associated to a peri-urban rocky shore. Mar. Biol. 157 (2), 283–294. doi: 10.1007/s00227-009-1316-9

Sear D., Langdon P., Leng M., Edwards M., Heaton T., Langdon C., et al. (2022). Climate and human exploitation have regulated Atlantic salmon populations in the river spey, Scotland, over the last 2000 years. Holocene 32 (8), 780–793. doi: 10.1177/09596836221095983

Sheldrick M. C., Chimonides P. J., Muir A. I., George J. D., Reid R. J., Kuiken T, et al. (1994). Stranded cetacean records for England, Scotland and Wales 1987–1992. Investigations on Cetacea 25, 259–283.

Shipley O. N., Matich P. (2020). Studying animal niches using bulk stable isotope ratios: an updated synthesis. Oecologia 193 (1), 27–51. doi: 10.1007/s00442-020-04654-4

Silva M. A., Prieto R., Magalhães S., Seabra M. I., Santos R. S., Hammond P. S. (2008). Ranging patterns of bottlenose dolphins living in oceanic waters: implications for population structure. Mar. Biol. 156 (2), 179–192. doi: 10.1007/s00227-008-1075-z

Simmonds M. P. (2017). “Evaluating the welfare implications of climate change for Cetaceans,” in Marine mammal welfare. Ed. Butterworth A. (Cham: Springer), 125–135. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-46994-2_8

Smith K. J., Trueman C. N., France C. A., Peterson M. J. (2020). Evaluation of two lipid removal methods for stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis in whale tissue. RCM 34 (18), e8851. doi: 10.1002/rcm.8851

Sonnerup R. E., Quay P. D., McNichol A. P., Bullister J. L., Westby T. A., Anderson H. L. (1999). Reconstructing the oceanic 13C suess effect. Global Biogeochem. Cy 13, 857–872. doi: 10.1029/1999GB900027

Spitz J., Cherel Y., Bertin S., Kiszka J., Dewez A., Ridoux V. (2011). Prey preferences among the community of deep-diving odontocetes from the Bay of Biscay, northeast Atlantic. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 58 (3), 273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2010.12.009

Spitz J., Mourocq E., Leauté J. P., Quéro J. C., Ridoux V. (2010b). Prey selection by the common dolphin: fulfilling high energy requirements with high quality food. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 390 (2), 73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2010.05.010

Spitz J., Mourocq E., Schoen V., Ridoux V. (2010a). Proximate composition and energy content of forage species from the Bay of Biscay: high-or low-quality food? ICES J. Mar. Sci. 67 (5), 909–915. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsq008

Spitz J., Richard E., Meynier L., Pusineri C., Ridoux V. (2006). Dietary plasticity of the oceanic striped dolphin, Stenella coeruleoalba, in the neritic waters of the Bay of Biscay. J. Sea Res. 55 (4), 309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2006.02.001

Sunday J. M., Bates A. E., Dulvy N. K. (2012). Thermal tolerance and the global redistribution of animals. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 686–690. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1539

ten Doeschate M. T., Brownlow A. C., Davison N. J., Thompson P. M. (2018). Dead useful; methods for quantifying baseline variability in stranding rates to improve the ecological value of the strandings record as a monitoring tool. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U.K. 98 (5), 1205–1209. doi: 10.1017/S0025315417000698

Troina G. C., Botta S., Dehairs F., Di Tullio J. C., Elskens M., Secchi E. R. (2020b). Skin δ13C and δ15N reveal spatial and temporal patterns of habitat and resource use by free-ranging odontocetes from the southwestern Atlantic ocean. Mar. Biol. 167 (12), 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s00227-020-03805-8

Troina G. C., Dehairs F., Botta S., Di Tullio J. C., Elskens M., Secchi E. R. (2020a). Zooplankton-based δ13C and δ15N isoscapes from the outer continental shelf and slope in the subtropical western south Atlantic. Deep-Sea Res. I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 159, 103235. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2020.103235

van der Kooij J., Engelhard G. H., Righton D. A. (2016). Climate change and squid range expansion in the North Sea. J. Biogeogr. 43 (11), 2285–2298. doi: 10.1111/jbi.12847

Varela J. L., Rodríguez-Marín E., Medina A. (2013). Estimating diets of pre-spawning Atlantic bluefin tuna from stomach content and stable isotope analyses. J. Sea Res. 76, 187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.seares.2012.09.002

Waggitt J. J., Evans P. G., Andrade J., Banks A. N., Boisseau O., Bolton M., et al. (2020). Distribution maps of cetacean and seabird populations in the North-East Atlantic. J. Appl. Ecol. 57 (2), 253–269. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.13525

Walker J. L., Potter C. W., Macko S. A. (1999). The diets of modern and historic bottlenose dolphin populations reflected through stable isotopes. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 15 (2), 335–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00805.x

Williams R. S., Brownlow A., Baillie A., Barber J. L., Barnett J., Davison N. J., et al. (2023). Evaluation of a marine mammal status and trends contaminants indicator for European waters. Sci. Total Environ. 866, 161301. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.161301

Keywords: dolphin, stable isotope, Scotland, Northeast Atlantic, niche, dietary overlap

Citation: Plint T, ten Doeschate MTI, Brownlow AC, Davison NJ, Hantke G, Kitchener AC, Longstaffe FJ, McGill RAR, Simon-Nutbrown C and Magill CR (2023) Stable isotope ecology and interspecific dietary overlap among dolphins in the Northeast Atlantic. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1111295. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1111295

Received: 29 November 2022; Accepted: 29 May 2023;

Published: 15 June 2023.

Edited by:

Yonat B. Swimmer, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United StatesReviewed by:

Maelle Connan, Nelson Mandela University, South AfricaShannon Marie McCluskey, Murdoch University, Australia

Joan Giménez, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), Spain

Copyright © 2023 Plint, ten Doeschate, Brownlow, Davison, Hantke, Kitchener, Longstaffe, McGill, Simon-Nutbrown and Magill. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tessa Plint, dHA0NkBody5hYy51aw==

Tessa Plint

Tessa Plint Mariel T.I. ten Doeschate

Mariel T.I. ten Doeschate Andrew C. Brownlow

Andrew C. Brownlow Nicholas J. Davison2

Nicholas J. Davison2 Georg Hantke

Georg Hantke Andrew C. Kitchener

Andrew C. Kitchener Fred J. Longstaffe

Fred J. Longstaffe Rona A. R. McGill

Rona A. R. McGill Cornelia Simon-Nutbrown

Cornelia Simon-Nutbrown Clayton R. Magill

Clayton R. Magill