- Institute of Ocean Technology and Marine Affairs, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan

Taiwan establishes Ocean Affairs Council (OAC) in 2018. Ocean governance has reached a new milestone. In 2019, the Ocean Basic Act was enacted. In 2020, the National Ocean Policy White Paper was published, meaning that Taiwan has specialized ocean authorities, regulations, enforcement units, and relevant mechanisms and policies. The Ocean Conservation Administration (OCA) is also responsible for marine environmental protection and conservation. To ensure good ocean governance, maintain marine resources, and protect the environment, the OCA has recently drafted the Marine Conservation Act for sustainable development. This article mainly reviews, analyzes, and compares Taiwan’s current marine-related laws and regulations and refers to the laws, policies, and mechanisms of other countries to provide suggestions on marine governance and the ongoing draft of the Marine Conservation Act.

1 Introduction

With ocean development and utilization, the proportion of national economic systems and national interests is increasing, and countries have realized the importance of marine resources and national interests. Coastal states have begun rapid ocean development, resulting in the gradual deterioration and damage of the marine and ecological environment (Shih, 2010; Yu D. et al., 2022), and polluted environments have gradually expanded with the development of regions. The development of marine industries, marine pollution, coastal development, and coastal activities are all factors that degrade the marine environment and cause biodiversity loss and a decline in biological resources; at the same time, they directly or indirectly cause many ecological and environmental problems (Derraik, 2002; Thompson et al., 2009a; Thompson et al., 2009b; Shih, 2010; Cole et al., 2011; Carbery et al., 2018; Yu D. et al., 2022).

To maintain a good marine environment and its resources, it is necessary to integrate marine management and ocean governance as support; comprehensive ocean governance is the foundation of marine sustainability, and it involves environmental monitoring programs or environmental indicators as criteria for environmental assessment (Shih, 2010). The twenty-first century revolves around oceans (Xu and Chang, 2017; Shih, 2020). Taiwan is famous for its rich marine biodiversity, ecosystems, and beautiful scenery. (Shao et al., 2008; Adams et al., 2010; Shao, 2020), and it is surrounded by oceans with rich marine resources (Huang and You, 2013; Chung and Jao, 2022); More than one-tenth of the world’s marine species are found in the waters of Taiwan (Shao, 2009). In Taiwan, marine and coastal environmental management have been implemented with a sectoral approach, not paying attention to the local community and private sector interests of the past. Moreover, although the population and consumptive needs for coastal and marine resources are growing, the existing policies and legal institutions have yet to be based on a systematic, comprehensive, and inter-sectoral approach, and special policies on marine environmental protection are rarely implemented (Chiau, 2017). Such monotony of policies and legal institutions can be seen through separation, conflict, overlap, unclear decentralization in policymaking and implementation, low effectiveness, and enforcement. Disputes of interest arise among beneficiaries of natural resources due to the lack of reasonable policies (Shih, 2017).

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in 1982, resolves issues of navigational rights, waters, protection of the marine environment, and dispute procedures. It intended to establish a legal code for the oceans for other international exchange and peaceful purposes and to ensure the effective and fair use and protection of marine resources. Climate change, as well as human exploitation, habitat degradation, and pollution of the marine environment, are reducing the abundance of many marine species, are increasing the potential for extinction of local species, and are impacting many marine ecosystems (Wigley and Raper, 1992; Harley et al., 2006; Hoegh-Guldberg and Bruno, 2010).

Part XII of the UNCLOS specifically provides obligations to protect and preserve the marine environment, and these obligations also give an implementation framework for ocean governance. An example of the good governance elements associated with this part of the treaty is shown below (Chang, 2010). Articles 192 to 196 set out the rights and obligations of states in relation to the protection of the marine environment. Article 192 states that “coastal States have an obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment” (Guo, 2020). This obligation to protect the marine environment has been interpreted and developed by international courts and tribunals, particularly in the South China Sea arbitration (Guo, 2020). Meanwhile, one of the main goals of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) is to guide countries in their pursuit of integrated plans for sustainable development (Molenaar, 1998).

At the same time, the United Nations has supported the implementation of SDG 14, the protection and sustainable use of oceans and marine resources for sustainable development. Environmental protection awareness has been growing partly because SDG targets responsible underwater life (SDG14; United Nations, 2015). Taiwan’s coastal waters have suffered from environmental degradation, loss of habitat and biodiversity, increasing conflict among resource users, and the same marine environmental problems found in other countries. The development of the social economy, the national energy policy, the rise of public awareness of environmental protection, and the utilization of environmental resources have caused massive pressure on the environment in the form of overfishing, pollution, ocean acidification, ecosystem collapse, etc. (Halpern et al., 2008; Huang and You, 2013; Rogers and Laffoley, 2013). To solve this degradation, Taiwan authorities are actively developing regulations and schemes to manage the marine environment (Shih, 2010).

Ocean governance includes many elements, including the rules, policies, laws and institutions established by governmental and/or non-governmental actors at all levels of decision-making that govern any kind of activity related to the ocean (Mondré and Kuhn, 2022; Song et al., 2022). Ocean governance should be different because it has a different definition and scope (Cho, 2006). Moreover, good governance is an integrated decision-making process involving social resources at all levels to achieve the goal of enhancing the common well-being of humankind (Chang, 2010). It is a positive and constructive guideline for sustainable development (Ginther and de Waart, 1995), and it requires inter-ministerial coordination and cooperation. Ocean governance can be defined as the sharing of policymaking capacity and institutional negotiation among the various systems of government (international, supranational, national, regional, and regional) for the effectiveness of the implementation of ocean management and its outcomes (Van Tatenhove, 2008). Ocean governance is the ability to formulate and implement ocean policies (Olsen et al., 1999), and ocean governance can be evaluated through management capacity assessment, i.e., the ability to effectively formulate and implement ocean policies (Cho, 2006). This goal can be achieved by establishing the highest level of executive authority to deal with ocean affairs in a unified manner, such as the Ocean Affairs Council (OAC) in the Executive Yuan, which is an inter-ministerial decision-making or coordination mechanism. At the vertical level, the development of national ocean policy requires the participation of authorities and the public at all levels, which can be achieved by educating the public and making information about the government’s ocean policy publicly available. In 1996, South Korea established the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (MOMAF) based on the elements of ocean governance, such as integrated ocean policy and agencies integration (Chung, 2010; Kim, 2012). These proposals were also made by Jacques and Smith (2003), who defined ocean politics as a competition for values, resources, and rights associated with the oceans. Indeed, the ocean governance system must somehow reflect the complexity and dynamic of the marine social and ecological system.

For a long time, Taiwan lacked a comprehensive investigation of the ocean, and no positive protection measures, coral reef bleaching, loss of marine habitat, increased water pollution, and the gradual loss of ecological balance, making the oceans face a more significant crisis (Shih, 2010). The government and the public have agreed that marine environmental protection and resource conservation are necessary. After the establishment of the OAC, the relevant supporting laws and regulations have been changed, which will improve the legalization of ocean governance.

This paper aims to provide a detailed overview of the current ocean-related regulations and developments in Taiwan. First, the contents of the newly introduced draft Marine Conservation Act are examined at the legislative level, focusing on the analysis of the characteristics of the legal framework. Meanwhile, the relevant supporting laws are proceeding at a snail’s pace. The awareness of marine protection in Taiwan has risen, but the relevant support and legislation have not been synchronized. Therefore, conservation groups and academia appeal to the government to complete the Marine Conservation Act, Marine Spatial Planning Act, and Marine Industry Development Act as soon as possible and accelerate the speed of legislation to legalize and deepen ocean policy and development of ocean governance. Secondly, the focus will be on the development of the OAC and comments on the Taiwan government’s efforts to integrate the functions of the various ocean governance departments. In addition, this paper learns from the experience of other countries, mainly with similar situations or environmental protection purposes, and can provide a reference in the legislative process of the draft Marine Conservation Act. Finally, learning from the experiences of other countries will make Taiwan’s marine environment conservation more efficient.

2 Materials and methods

This paper analyzes Taiwan’s ocean-related laws and regulations. It uses comparative analysis to identify critical information such as the legislation’s purpose, such as the legislation’s reasons, the legislation’s role, their interaction, and to reveal Taiwan’s ocean-related progress of the ocean protection regulatory framework. The steps of this study are as follows: first, we collected the marine-related laws and regulations over the years and examined the goals and objectives of each law. Second, we examine the related objectives of individual regulations and marine environmental protection to take stock of whether individual laws and regulations are comprehensive and complete in terms of marine environmental protection. Third, we examine the interaction between existing marine environmental protection issues, laws, and regulations. Fourth, this paper addresses the problems in implementing and enforcing marine environmental laws and regulations and the expectations of society and the public and makes targeted suggestions.

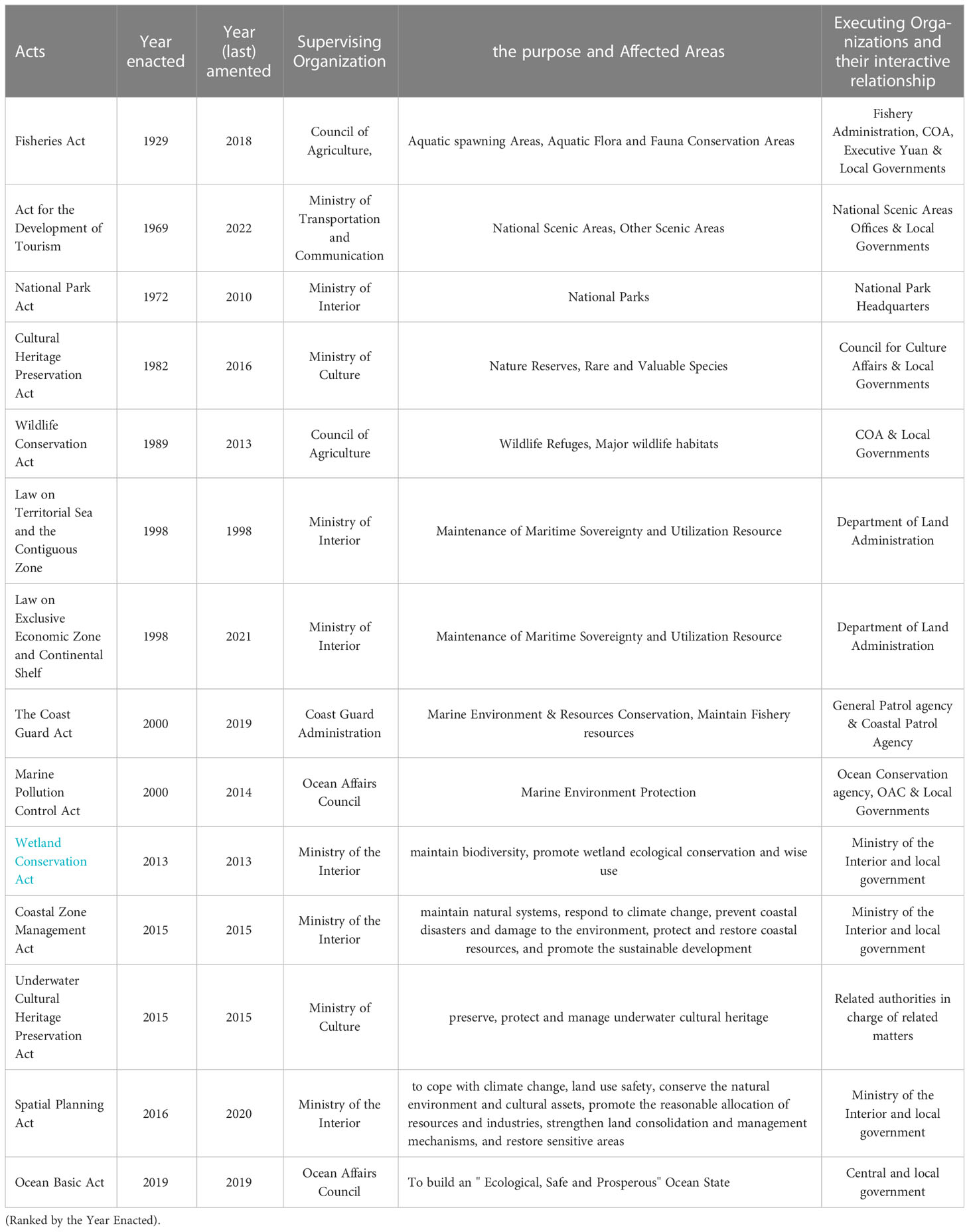

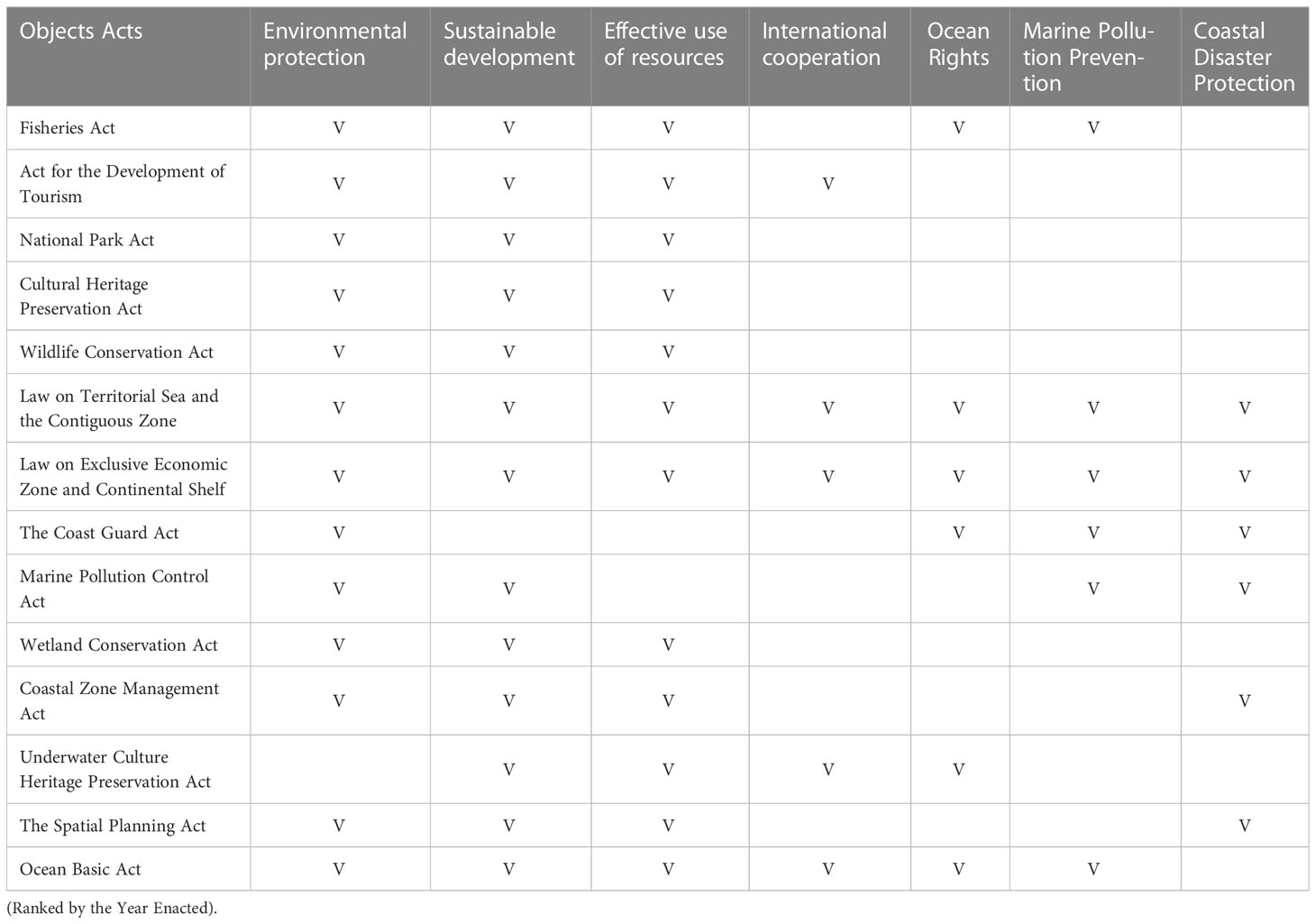

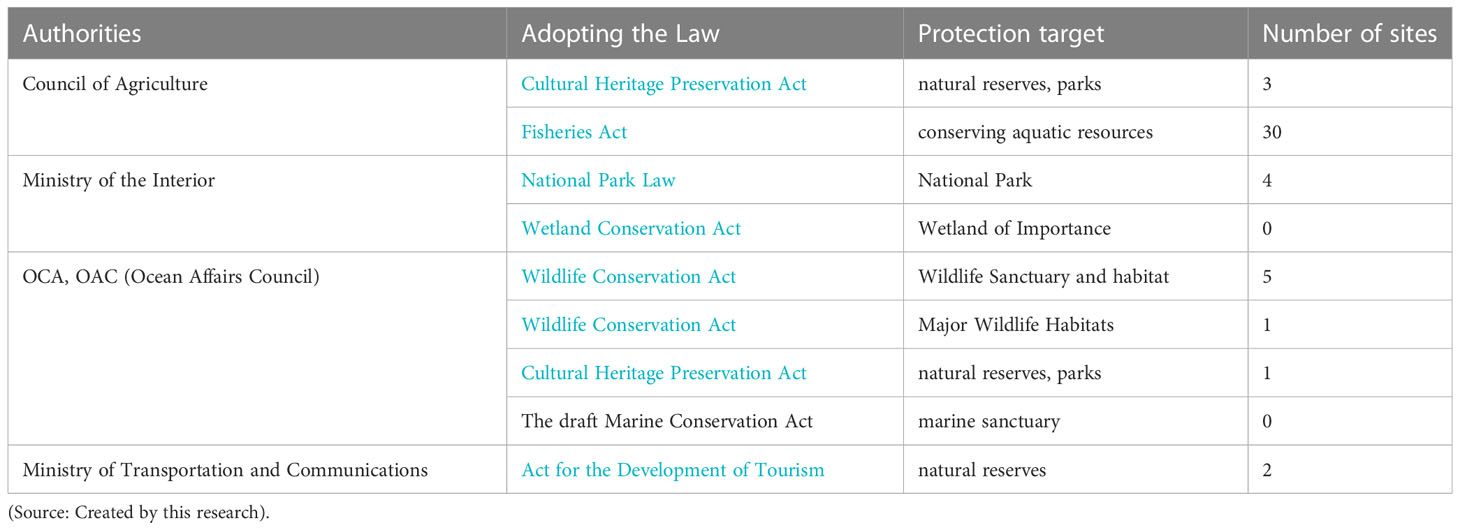

This study collects the relevant laws and regulations (Table 1) on marine environmental protection issues from Taiwan’s current marine authorities, and this paper takes the draft of the Marine Conservation Act as the object of study. The main focus of the analysis in this paper is to discuss and analyze the organizational act of the marine authorities and the regulations related to marine environmental protection, such as the Wetland Conservation Act (2013), Marine Pollution Control Act (MPCA) (2014), Coastal Zone Management Act (2015), Underwater Culture Heritage Preservation Act (2015), the Organization Act of Ocean Affairs Council and its subordinate Organizations Act (2015), the Ocean Basic Act (2019), etc. (Table 2).

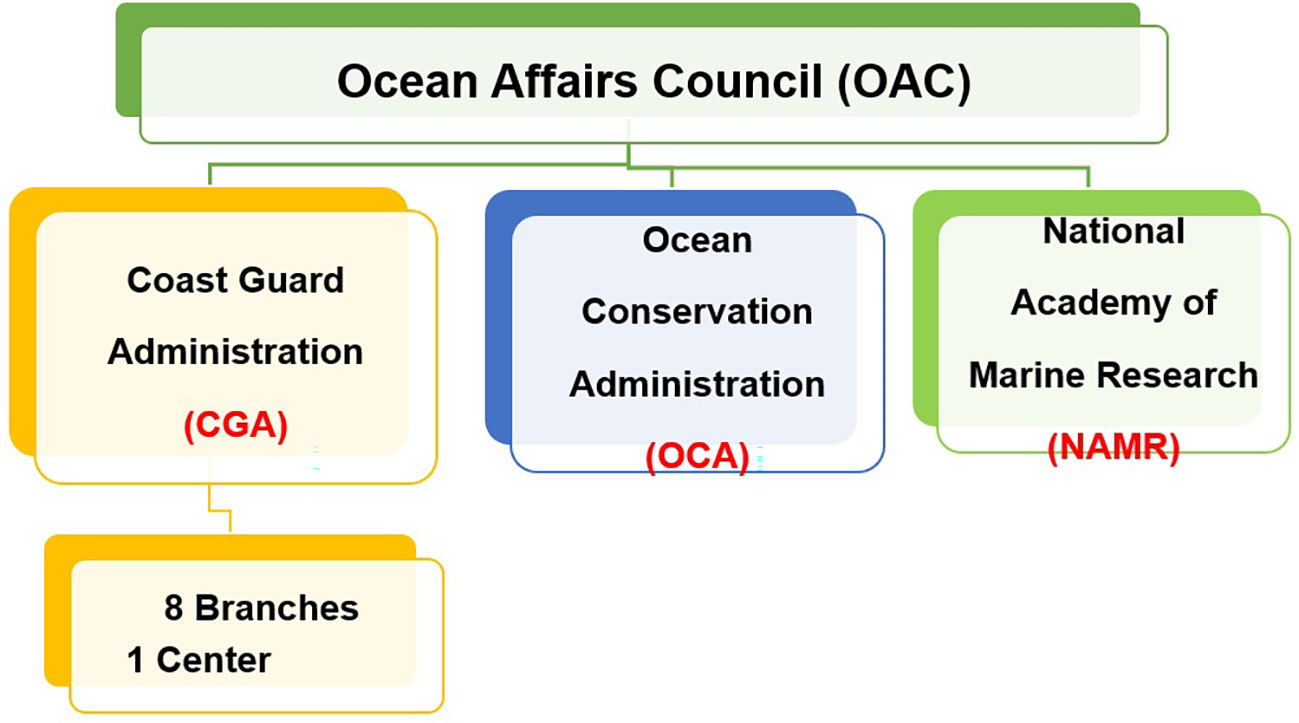

In 2018, Taiwan’s central government (cabinet) established the specialized ocean authorities, the OAC (Figure 1), responsible for ocean affairs and governance, integrates and coordinates all ocean-related matters, as well as the CGA (Coast Guard Administration), OCA and NAMR (National Academy of Marine Research) (Shih, 2020). In 2019, the Ocean Basic Act (OBA) was approved; the purpose of the legislation is to create a healthy marine environment, promote sustainable resources, enhance the development of marine industries, and improve regional and international cooperation on ocean affairs. According to Article 18 of OBA, National Oceans Day is celebrated on June 8 each year, which also echoes World Ocean Day. In addition, the OAC published the National Ocean Policy While Paper (NOPWP), which had to be announced within 1 year of the Ocean Basic Act taking effect in 2019. Moreover, the OAC compiled the NOPWP and has recently formulated the Marine Conservation Act (Draft), Marine Industry Development Act (Draft), and Coast Area Management Act (Draft) for the enforcement of the OBA to achieve the vision of the OAC, which sees Taiwan as an ocean country with ecological sustainability, maritime safety, and prosperous industries. Following the international conservation trend, such as achieving the Aichi Targets related to the sustainable development of the oceans, for example, “habitat loss,” “sustainable fisheries,” “pollution,” “vulnerable ecosystems,” “protected areas,” “species survival,” “ecosystem services,” “ecosystem restoration,” etc., In addition, the 2015 United Nations Sustainable Development Agenda has 17 goals for sustainable development, including SDG 14, “Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Resources to Ensure Sustainable Development.” are all included in the draft marine conservation act.

3 Current status of Taiwan’s legal framework for ocean governance

3.1 Following the international regulations

The Stockholm Declaration of 1972 is recognized as the benchmark for launching the modern environmental movement (Friedheim, 2000). It consisted of a Preface and 26 principles covering all aspects of environmental protection and degradation (Sohn, 1973). The conference prompted the world to monitor environmental conditions and establish environmental ministries and agencies (Meyer et al., 1997; Selin and Linnér, 2005; Hironaka, 2014). The follow-up United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Earth Summit) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, the Johannesburg World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in 2002, and the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) in 2012 all found their way into the Stockholm Declaration. Ocean sustainability is regarded as essential to the future well-being of the world. This can be seen in 1973 the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL 73/78), which aimed at combating the degradation of water quality caused by pollution related to navigation and maritime transport; the 1992 Rio Declaration, Chapter 17 of Agenda 21; in the 2002 WSSD; and the 1982 UNCLOS. Specifically, Chapter 17 of Agenda 21 makes it evident that UNCED considers UNCLOS to be the essential basis for marine environment law (Cicin-Sain, 1996). The UNCLOS, signed in 1982, is an important legal framework for conserving and protecting the marine environment, maintaining and using living marine resources, and preventing marine pollution. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), also signed in 1992, is the most significant conservation convention. There is considerable international awareness of the need to protect the marine environment and resources.

The United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, the Stockholm United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, and other major international conferences promoted the development of international marine environmental and resource law in many countries. The objective of the CBD is to establish the legal order for the seas and oceans, which will facilitate international communication and promote the peaceful and wide use of the oceans, the equitable and efficient utilization of their resources, the conservation of living resources, and the study, protection, and preservation of the marine environment. The goals of the CBD are to establish a legal regime for the oceans, facilitate international communication, promote the peaceful and wise use of the oceans, the equitable and efficacious use of marine resources, conservation of living resources, and the protection of the oceans. It also studies, protects, and preserves the marine environment. However, this framework needs to be revised, and the effectiveness of international law relies on the implementation of all states. The UNCLOS was adopted by the United Nations in 1982 and entered into force in 1994; 168 countries have signed it so far, and some scholars call it the “Constitution for the Oceans.” Articles 192 to 196 of Part XII of the UNCLOS deal with the rights and obligations of states concerning the protection of the marine environment. Article 192 points out that “States have the obligation to protect and preserve the marine environment” (Guo, 2020). Since 1984, the Secretary-General of the United Nations has submitted an annual report to the United Nations General Assembly on developments relating to the law of the sea. The Secretary-General’s annual report on oceans and the law of the sea provides an overview of the latest ocean issues of concern to the international community (OAC, 2019b).

3.2 Before establishing the OAC

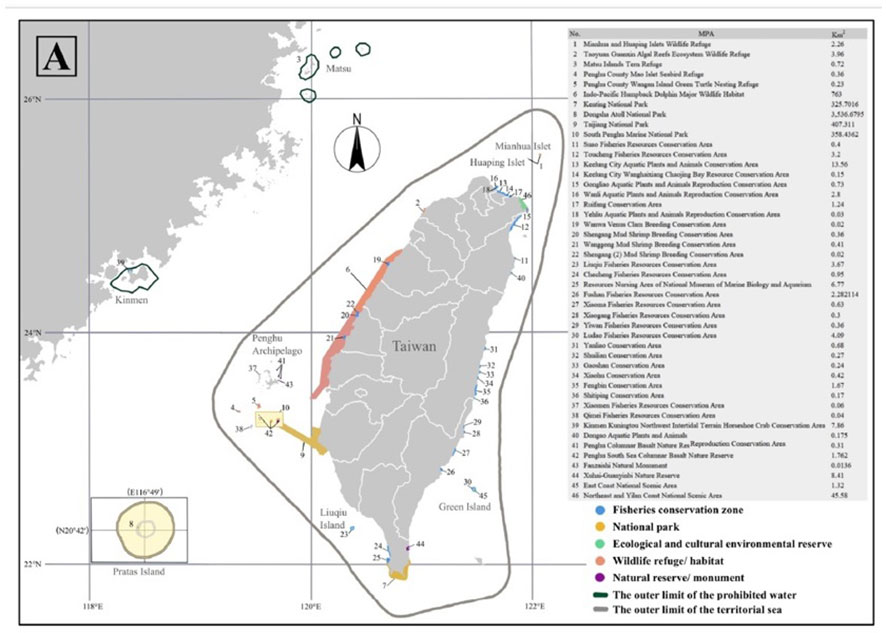

Taiwan has a coastline of around 1,600 km, embracing an abundance of coral reefs, lagoons, wetlands, estuaries, mangroves, barriers, etc. The number of marine species found in Taiwan can exceed one-tenth of that in the oceans globally, which points to the importance of marine resources conservation (MRC) in Taiwan. Meanwhile, according to a survey and report of the problems of MRC in Taiwan waters, the main causes of decreasing marine resources include human activities, marine environmental pollution, overexploitation, habitat destruction, depletion of fishery resources, coastal erosion, and development issues (Shao, 2009; Chiau, 2016). Reduced biodiversity leads to the deterioration of marine ecosystems and decreased fisheries production (Shao, 2000); thus, there is an urgent need for marine environmental protection, and NGOs, scholars, and legislators are working hard to promote the establishment of a specialized ocean authority and to conserve the marine environment and resources. In 2016, the Sustainable Ocean Initiative driven by scholars and legislators passed the Call to Action, which summarized 37 items to appeal, including strengthening internationalization and cooperation, strengthening scientific research, formulating relevant management plans, and formulating ocean governance regulations. The simplest, most economical, and most effective way to protect the marine environment and preserve marine resources is to establish marine protected areas (MPAs) (Shao, 2000; Benedetti-Cecchi et al., 2003; FAO, 2010). Many international conferences have called for establishing MPAs to strengthen marine environmental protection and resource conservation. Taiwan’s government established MPAs with regulations relating to the Acts already in force to protect abundant resources. Recently, the government has worked with conservation organizations and academic institutions to protect resources and establish various protected areas through the National Parks Act, the Cultural Heritage Protection Act, the Wildlife Protection Act of 1994, and the Coast Guard Act. These Acts support the implementation of natural and marine resource conservation in Taiwan. The related regulations and executing organizations are listed in Table 1. In 2010, the Executive Yuan proclaimed that 20% of Taiwan’s waters would be MPAs by 2020 (National Council for Sustainable Development, 2019).

3.3 Current and future development

Currently, Taiwan’s marine environmental protection and resource conservation work is scattered across various acts and regulations, such as the Wildlife Conservation Act, the National Parks Act, the Fisheries Act, and the Underwater Cultural Assets Preservation Act; however, none of them has an ecosystem-based protection policy, leaving the overall marine conservation effort in a predicament. These individual laws have different protection objectives, resulting in different protection standards.

According to Article 13 of the Ocean Basic Act in Taiwan, the government should prioritize the protection of natural coastal areas, landscapes, critical marine habitats, unique and endangered species, vulnerable and sensitive areas, and underwater cultural assets based on an ecosystem approach; protect marine biodiversity; develop relevant preservation, protection, and conservation policies and programs; implement impact mitigation measures, ecological compensation, or other development options; establish marine protected areas to restore marine ecosystems and natural environments; and protecting the rights of original sea users.

Article 1 of the Organization Act of the OCA in 2015 deals with protecting marine resources and ecology and their sustainable management. Further, Article 6 provides that the OCA may establish service units if necessary to protect marine environmental resources and enforcement. This allows the OCA to have the capacity and ability to implement related conservation law enforcement in Taiwan’s waters.

The draft Marine Conservation Act has five chapters and 31 articles (Table 3), and the benefits are to enhance the protection of Taiwan’s marine environment, ensure the conservation and restoration of marine biodiversity, and promote the coordinated planning and implementation of marine protected areas, to reduce the conflicts among different users, and to create a healthy marine environment and promote resource sustainability. Indeed, the draft Marine Conservation Act is tasked with integrating the overall marine conservation goals, and its implementation by legislation will establish a coordinated mechanism for marine conservation efforts and promote sustainability in the future. For example, Taiwan’s white dolphins (Sousa chinensis) were designated as a wild species in 2020, but their numbers have decreased over the past few years because of the lack of integrated laws and protections (OCA, 2019b; NAMR, 2020; OAC, 2020). Since the establishment of the OAC in Taiwan in 2018, ocean governance has reached a new milestone. The OCA was established, which is taking over the task of managing marine protection and resource conservation, enforcing relevant laws and regulations to make marine protection work more institutionalized, and which should be able to integrate and coordinating the management of existing planned marine reserves in the future (OCA, 2020).

4 Current and future challenge

4.1 Policy and legislation

As an ocean state, Taiwan has valued its “Blue Territory.” After passing the Ocean Basic Act in 2019, continue to promote the draft Marine Conservation Act, expand the scope of marine life conservation, and integrate the management resources of various protected areas or reserves; however, the draft has been at a standstill for many years. Recently, legislators invited NGOs, experts, scholars, and related authorities to hold a public hearing on “Sustainable Ocean Governance, Formulating the Marine Conservation Act to create a Win-Win Situation”. Taiwan’s current marine conservation regulations ignore protecting the overall marine environment and international trends. For example, the ocean has a vital carbon sink function, which can become a natural solution to climate change. Meanwhile, the OCA has been established for several years but still does not have its administrative effect law. Therefore, all sectors have asked the OCA to include the blue carbon ecosystem in the draft Marine Conservation Act.

According to the draft of Chapter 2, Marine Protected Areas, to date, there are 46 marine protected areas in Taiwan (Chung and Jao, 2022; OAC, 2022) located in the territorial or prohibited waters off the coast of Taiwan (Chung and Jao, 2022) (Figure 2).

The percentage of MPAs in Taiwan depends on the definition of “no-fishing”; academia calculates it at 5.65% and the Fisheries Agency (FA) at 40.65% (Shao and Lai, 2011); the designation of MPAs in Taiwan is 46.15%—a very high percentage far exceeding the target of 10% by 2020 set by the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2010. When examining the areas designated as marine protected areas, it was found that MPAs are mainly zoned for multipurpose use, with up to 40% of the area designated for fishing gear and specific fishing areas. In other words, any area that restricts fisheries laws (including trawl sanctuary, artificial reef area, 6 NM lighted sanctuary, etc.) is classified as MPA (Chen, 2016). However, regulations and enforcement vary in some waters, and some that are not enforced may become paper parks (Edgar et al., 2014; Halpern, 2014).

4.2 Implementation and enforcement

Recently, the production and value of Taiwan’s offshore fisheries have declined significantly, and MPAs are widely recognized as an essential tool for protecting marine biodiversity, habitat, and a variety of ecosystem services, including those related to recreation (Abecasis et al., 2013; Rees et al., 2015). The progression of the MPA concept - at least initially - occurred in the absence of an international legal framework. At the global level, much of the driving force for establishing marine protected areas came from NGO initiatives rather than any obligations under international law (Warner, 2001). Notably, a necessary impetus for the declaration of marine protected areas under international law was the program developed by the IUCN (Freestone, 1996).

Overexploitation, overfishing, and overcapacity have led to severe exploitation of fish stocks (Beddington et al., 2007; Shih, 2010; Chang et al., 2012). Nevertheless, MPAs are considered one of the most appropriate management measures for fish population recovery and sustainable ecosystem maintenance (Agardy, 2000; Stefansson and Rosenberg, 2006; Chang et al., 2012). In 2006, the Ocean Policy White Paper listed MPAs as an essential development policy and proposed detailed proposals to establish Green Island, the three northern islands, and the Penghu Islands as marine national parks. In 2007, the Marine National Park headquarters officially emerged, marking an essential milestone in developing MPAs. There is a global commitment to protect 10% of the oceans by 2020 (e.g., SDG target 14.5 under the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNEP, 2011; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2017)), including many other regional or national conservation goals. The proposal, designation and implementation of marine protected areas have accelerated over the past decade. The OCA’s Strategic Objectives and Actions are clean water, healthy habitat, and sustainable resources. In 2021, 40 marine conservation inspectors were assigned to 13 marine conservation workstations. The inspectors are at marine sites to respond to notifications from the public on marine conservation matters, which will help implement marine patrol and conservation matters. At the same time, Taiwan’s energy policy, offshore wind power, has continued to develop in recent years, but also because the failure to install offshore wind turbines may threaten fishermen, marine life, and habitats. So the NGOs have called on the government to pay attention to it. Therefore, the draft Marine Conservation Act legislation will be significant in the future.

4.3 Equipment and infrastructural requirements

Most of Taiwan’s marine protection zones lack scientific data for long-term monitoring as the basis for policy and decision-making, and it isn’t easy to effectively evaluate the objectives at the time of establishment. As regards the open ocean database, one of the crucial objectives of the daft Marine Conservation Act is that sufficient basic ocean information must be made available to the public, including information on species diversity, the ecological status of critical species, and overall dynamic changes (NAMR, 2020). As for marine conservation enforcement, the OCA needs the equipment capacity of conservation enforcement vessels or law enforcement base stations around Taiwan and must expand its capacity as soon as possible for immediate enforcement in the sea (OAC, 2020).

5 Discussion

The reasons to promote the legislation for the need and urgency of the Marine Conservation Act, such as to complete the legal system of marine conservation; to achieve the missions of establishing the OAC and OCA; to implement Taiwan’s sustainable development goals (SDGs 14); to conserve cetaceans and sea turtles urgent needs of the urgent need; to assist the offshore wind farm restoration projects and assistance with vessel navigation controls; to the response to other marine conservation needs; to meeting national expectations for marine conservation; to satisfy the anticipations for marine conservation of Taiwan people. The management of Taiwan’s ocean affairs is divided into different departments (Chiau, 2016), scattered among many departments of the Taiwan government (Lin et al., 2013; Xu and Chang, 2017). However, in the process of promoting the draft Marine Conservation Act, some issues can be learned from the legislative experience of other countries, as follows:

To improve the zoning management system:

Regarding the management principles of MPAs zones, the international community has divided them into four main categories, such as no-use zones, no-fishing zones, buffer zones, and sustainable-use zones. For example, in the Australian management of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park(GBRMP), the protected area can be divided into four parts: core protected area, fishing area, no-fishing area, and sightseeing area; then, based on respecting the historical habits of the original inhabitants of the Great Barrier Reef, the initial closed management can be changed to integrated open management to ensure that the functional areas of marine ecosystems such as islands, harbors, estuaries, and coasts can be fully protected and the functional areas of the sea can be improved (GBRMPZ Plan, 2003). Critical lessons from their experience focus on placing marine reserves in a broader context, the importance of good public processes, and the advantages of integrating site-specific development with national-level system planning (Sobel et al., 2004). The legislative protection of the GBRMP is a benchmark for countries to learn from, and Taiwan has many rare corals to learn from their experiences. Taiwan has encountered the same problem in the legislative process of protection and conservation. In contrast, Taiwan is currently divided into only three categories, including “no entry or impact zones,” “no-fishing zone,” and “multifunctional use zone,” and lacks “buffer zones” with important functions. The government should refer to international standards and plan a certain percentage of buffer zones. Coupled with the lack of long-term ecological surveys and monitoring and evaluation of management effectiveness, most protected areas are “paper parks” (Shao, 2020). Such as New Zealand could be a leader in MPAs. Despite their small size and slow development, the principles, lessons, and ideas that have emerged from their creation have greatly influenced the development of MPAs throughout New Zealand and the world. Meanwhile, the New Zealand Department of Conservation (NZDOC), established in 1987, has primary management responsibility for MPAs. In 2002, the New Zealand government’s Marine Reserves Act also demonstrated the government’s commitment to conservation and determination. Ballantine (1997) also provides a good perspective on the design principles of marine protected area systems or networks. The current 46 marine protected areas in Taiwan are not yet coordinated by the Marine Conservation Act (Table 4). They are divided into different authorities for designation and management, confusing management laws and policies (Chung and Jao, 2022; OCA, 2022). Meanwhile, Learning from Canada has used the internationally widely accepted definition of MPA developed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Through a comprehensive marine reserve management plan and the development of a complete evaluation and review mechanism, the effectiveness of marine reserve management can be effectively improved.

Requirements from the Ocean Basic Act:

By Article 13 of the OBA, the government shall give priority to the protection of natural coast, landscape, critical marine habitats, unique and endangered species, fragile and sensitive areas, and underwater cultural assets based on an ecosystem approach, preserve marine biodiversity, formulate relevant preservation, conservation, and protection policies and plans. Therefore, there is a need to pass the Marine Conservation Act. In addition, the legislative objectives of the draft Marine Conservation Act are to gear the international standards of marine conservation; the act will introduce other effective regional conservation measures and expand marine protected areas in the broad sense; the act will pay equal attention to the conservation and rehabilitation of marine organisms and strive to maintain marine biodiversity; to supplement the inadequacies of other existing marine conservation-related laws and regulations and to build a well-organized and hierarchical system of marine conservation laws and regulations. Japan is a maritime country surrounded by the sea. Because of its limited land resources, the effective exploitation of the sea has become a critical strategy for Japan. Compared to other countries, Japan pays more attention to marine resources and protection legislation. The Japanese government promulgated the Basic Act on Ocean Policy in 2007, which stipulates the basic principles of Japan’s ocean policy and the responsibilities of the national government, local governments, businesses, and citizens to promote peaceful and joyous development use of the ocean and protection of the marine environment following the UNCLOS.

Meanwhile, there are many laws, ordinances, provincial ordinances, rules, etc., related to protecting marine living resources, such as laws, ordinances, provincial ordinances, rules, etc. Taiwan has many laws from Japan, and the purpose and spirit of its laws are worth learning and improving.

From the perspective of the Ocean Conservation Administration Organization Act:

Only 40 marine conservation enforcement officers are scattered across Taiwan and its coastal area. They must be sufficient to manage various marine conservation situations or crises. Instead, they seek assistance from friendly military units, such as the CGA, for duty and enforcement support, according to the Organization Act of the OCA, the matters related to maintaining marine resources, ecology, and sustainable management. If necessary, the OCA could set up servicing units to protect marine environmental resources and law enforcement energy more efficiently. The units will allow the OCA to have the capacity and ability to implement related conservation law enforcement in Taiwan’s waters. OCA also can learn from the U.S. Coast Guard that they have two primary responsibilities for marine environmental protection, ensuring timely and effective marine pollution response, enforcing marine environmental protection regulations, and enforcing marine pollution response and environmental protection regulations by the Maritime Safety Manual. Meanwhile, OCA also can learn from the Office of Law Enforcement (OLE) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) enforces the U.S. Marine Resources Act to ensure the sustainability of fish populations and to protect threatened marine species and their habitats.

Response perspective of marine pollution:

The MPCA aims to control marine pollution, protect the marine environment, conserve marine ecology, protect public health, and sustainably use marine resources. The Act applies to intertidal zones, internal waters, territorial waters, contiguous zones, exclusive economic zones, and waters superjacent to the continental shelf under the jurisdiction of Taiwan. Marine pollution is a global problem, and the management of the marine environment through the legal system has been a concern for the last few decades. The MPCA has been implemented for over 20 years in Taiwan and is in the process of revision. In addition, the competent authority has been transferred from the former Environmental Protection Administration to the Ocean Conservation Administration (OCA) of the OAC, which is different from the previous disposal in terms of enforcement, equipment, energy, and system (Churchill and Lowe, 1999; Chang, 2015). Therefore, at the current amendment stage, it is recommended to conform to the international trend and tendency and pay more attention to the response and disposal of significant oil pollution incidents in exclusive economic waters or even on high seas and the cooperation mechanism with neighboring countries.

The related Acts have not been enacted as scheduled:

The Ocean Basic Act was promulgated and implemented on November 20, 2019. It stipulates that the government should enact laws and regulations related to marine spatial planning and ecosystem development within two years. However, the legal deadline has long expired, and the relevant supporting Acts still need to be passed. On the other hand, Japan passed its Basic Act on Ocean Policy in 2007, based on which the Japanese Government has formulated a Basic Plan for Ocean policy and reviews and amends the Act every five years. One of the goals of the Act is to develop and use the oceans to conserve the marine environment. To date, the Basic Act has implemented its third stage basic plan.

There is no update to relevant laws and regulations in Taiwan:

Activities such as whale watching have been conducted for over two decades; however, further updates to relevant laws and regulations have yet to be made, and no effective supervision mechanism arising from the self-governance agreements signed by the operators has been established. As a result, reports of disturbing cetaceans are occasionally heard. Therefore, at this time, the OCA is expected to intervene by society and environmental conservation groups, particularly with the upcoming proposal of the ocean conservation Act that stipulates relevant management regulations targeting marine recreation, leisure activities, and other marine activities. In 2019, the OCA issued the Cetacean Watching Guide in Taiwan (OCA, 2019a); however, this may be a code of conduct that calls on environmentally friendly whale-watching behavior and has no legal effect. Regarding whale watching, the New Zealand Government promulgated the Marine Mammals Protection Act (MMPA) as early as 1978. The rules for interactions between ships and cetaceans, etc., were all regulated before the establishment of the whale-watching industry. That industry provided more output value and many job opportunities, and the Department of Conservation (DoC) and the members of the whale-watching industry signed a self-governance agreement for the protection and a mechanism to ensure sustainable operations and management (Tseng, 2021). In addition, New Zealand needs more and more enormous marine reserves; it also needs a national system or network of marine reserves that people could be free to access and enjoy while ensuring that their natural values are not compromised. At the same time, the public should be involved in establishing and managing marine reserves (Ballantine, 1999; NZDOC, 2022). The same situation as Taiwan’s current efforts to protect and develop.

6 Conclusion

The twenty-first century is a new century for humans’ development of oceans and seas, and oceans have become a significant issue of competition among the world’s States, attracting the research efforts of advanced countries. An increasing number of people are aware that ecosystem changes, environmental degradation, and habitat loss mainly cause a decrease in biodiversity. Despite accelerating and expanding changes to the marine ecosystem and its habitat, awakening the public’s awareness of marine conservation and changes in social values and conservation concepts have brought new hope for oceans. Marine conservation has gradually emerged with the improvement of environmental protection and fisheries management systems and methods. Many conservation groups have advocated various conservation campaigns, such as wetland protection, designated protected areas, zoning, and marine spatial planning.

To date, the number of Taiwan’s MPAs does have a specific meaning, but not equal to management effectively. A specified and integrated MPA law may help clarify the legal and administration chaos; therefore, it is expected that the draft of the Marine Conservation Act will be more complete. Good governance of MPAs requires cooperation among all stakeholders, including governments, enterprises, local people, and NGOs.

Taiwan’s draft Marine Conservation Act is in line with the development of marine environmental protection worldwide, generating great expectations. However, to be more effective, it is also necessary to draw on the experience of countries worldwide. The experience gained should be a reference in planning marine protected areas and conservation targets. The formulation of regulations alone is, however, never enough and still requires the collective participation of the community, public participation, the introduction of natural landscapes and local culture, the self-management and maintenance of ecological resources in the ocean and marine areas, etc.; for instance, the process of establishing MPAs requires careful planning and the support of local communities. Nevertheless, the OAC plays the role of “the guardians of the blue territory and the promoters of maritime affairs,” It can push for more education, training, and research programs on MPAs, which will be critical for Taiwan in the coming future.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Y-CS: Idea, Design, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing-original draft. WC: Methodology, Data curation, Writing-original draft. TC: Methodology, Validation, Writing-review & editing, Supervision. CC: Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - review & editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the reviewers from the Frontiers in Marine Science for their precious comments and my Ocean Affairs Council, National Academy of Marine Research, and Ocean Conservation Administration colleagues for their contributions and a great help.

Conflict of interest

The authors declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abecasis R. C., Schmidt L., Longnecker N., Clifton J. (2013). Implications of community and stakeholder perceptions of the marine environment and its conservation for MPA management in a small azorean island. Ocean Coast. Manage. 84, 208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.08.009

Adams V. M., Pressey R. L., Naidoo R. (2010). Opportunity costs: who really pays for conservation? Biol. Conserv. 143, 439–448. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.11.011

Agardy T. (2000). Information needs for marine protected areas: Scientific and societal. Bull. Mar. Sci. 66 (3), 875–888.

Ballantine W. J. (1997). ‘No-take’ marine reserve networks support fisheries. In Ed. Hancock D. A., Smith D.C, Grant A., Beumer J.P.. Developing and Sustaining World Fisheries Resources: The State and Management, 2nd World Fisheries Congress Proceedings, (Australia: CSIRO Publishing Collingwood), 702–706.

Ballantine W. J. (1999). Marine reserves in new Zealand: the development of the concept and the principles. In Proceedings of an International Workshop on Marine Conservation for the new Millenium, (Chefu Island, Korea: Korean Ocean Research and Development Institute). pp. 3–38. Available at: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=2f449660f176f40007df319b8f05079f3fa7ccb2.

Beddington J. R., Agnew D. J., Clark C. W. (2007). Current problems in the management of marine fisheries. Science 316 (5832), 1713–1716. doi: 10.1126/science.1137362

Benedetti-Cecchi L., Bertocci I., Micheli F., Maggi E., Fosella T., Vaselli S. (2003). Implications of spatial heterogeneity for management of marine protected areas (MPAs): examples from assemblages of rocky coasts in the northwest Mediterranean. Mar. Environ. Res. 55 (5), 429–458. doi: 10.1016/S0141-1136(02)00310-0

Carbery M., O’Connor W., Palanisami T. (2018). Trophic transfer of microplastics and mixed contaminants in the marine food web and implications for human health. Environ. Int. 115, 400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.03.007

Chang K.-C., Hwungb H.-H., Chuang C.-T. (2012). An exploration of stakeholder conflict over the Taiwanese marine protected area. Ocean Coastal Management 55, 36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.10.008

Chen C.-. L. (2016). The cornerstone of marine conservation - the designation and implementation of marine protected areas, coast guard bulletin bi-monthly, Vol. 82. 47–52. (Taiwan: Caoat Guard Administraion). Available at: https://www.cga.gov.tw/bookcase/CoastGuardBC/NO82/CoastGuard082.html.

Cho D. O (2006). Evaluation of the ocean governance system in Korea. Mar. Policy 30 (5), 570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2005.09.003

Chung S.-Y. (2010). Strengthening regional governance to protect the marine environment in northeast Asia: From a fragmented to an integrated approach. Mar. Policy 34, 549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2009.10.011

Chung H.-S. E., Jao J.-C. (2022). Improving marine protected area governance: Concerns and possible solutions from taiwan’s practice. Mar. Policy 140, 105078. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105078

Churchill R. R., Lowe A. V. (1999). The law of the Sea (Manchester: Manchester University Press), 328–329.

Cicin-Sain B. (1996). Earth summit implementation: progress since Rio. Mar. Policy 20 (2), 123–143. doi: 10.1016/S0308-597X(96)00002-4

Coastal Zone Management Act (2015) (Taiwan: Ministry of the Interior). Available at: https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=D0070222.

Cole M., Lindeque P., Halsband C., Galloway T. S. (2011). Microplastics as contaminants in the marine environment: a review. Mar. pollut. Bull. 62, 2588–2597. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.09.025

Derraik JoséG. B. (2002). The pollution of the marine environment by plastic debris: a review. Mar. pollut. Bull. 44, 842–852. doi: 10.1016/s0025-326x(02)00220-5

Edgar G. J., Stuart-Smith R. D., Willis T. J., Kininmonth S., Baker S. C., Banks S., et al. (2014). Global conservation outcomes depend on marine protected areas with five key features. Nature 506, 216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature13022

Freestone D. (1996). The conservation of marine ecosystems under International Law, International Law and the Conservation of Marine Biodiversity, Kluwer Law International. 1996, 91–107.

Friedheim R. (2000). Designing the ocean policy future: An essay on how I am going to do that. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 31 (1-2), 183–195. doi: 10.1080/009083200276111

GBRMPZ Plan (2003). Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Zoning Plan 2003. Available at: https://elibrary.gbrmpa.gov.au/jspui/handle/11017/382.

Ginther K., de Waart P. J.I.M. (1995). “Sustainable development as a matter of good governance: An introductory view,” in Sustainable development and good governance. Eds. Ginther K., Denters E., de Waart P. J.I.M. (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers), 9.

Guo J. (2020). The developments of marine environmental protection obligation in article 192 of UNCLOS and the operational impact on china’s marine policy – a south China sea fisheries perspective. Mar. Policy 120, 104140. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104140

Halpern B. S., Walbridge S., Selkoe K. A., Kappel C. V., Micheli F., d'Agrosa C., et al. (2008). A global map of human impact on marine ecosystems. Science 319 (5865), 948–952. doi: 10.1126/science.114934

Halpern B. S. (2014). Making marine protected areas work. Nature 506, 167–168. doi: 10.1038/nature13053

Harley C. D.G., Hughes A.R., Hultgren K. M., Miner B. G., Sorte C. J.B., Thornber C. S., et al. (2006). The impacts of climate change in coastal marine systems. Ecol. Lett. 9, 228–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00871.x

Hironaka A. (2014). “The origins of the global environmental regime,” in Greening the globe: World society and environmental change (Cambridge University Press), 24–47. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139381833.003

Hoegh-Guldberg O., Bruno J. F. (2010). The impact of climate change on the world’s marine ecosystems. Science 328 (5985), 1523–1528. doi: 10.1126/science.1189930

Huang H.-W., You M.-H. (2013). Public perception of ocean governance and marine resources management in Taiwan. Coast. Manage. 41, 420–438. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2013.822288

Jacques P., Smith Z. A. (2003). Ocean politics and policy: A reference handbook (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO).

Kim S. G. (2012). The impact of institutional arrangement on ocean governance: International trends and the case of Korea. Ocean Coast. Manage. 64, 47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.04.011

Lin K.-L., Jhan H.-T., Lee M.-T., Liu W.-H., Wang Y.-C., Tsai P.-T. (2013). The Taiwanese institutional arrangements for ocean and coastal management twenty years after the Rio declaration. Coast. Manage. 41, 134–149. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2013.767175

Marine Pollution Control Act, MPCA (2014) (Taiwan: Ocean Affairs Council). Available at: https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=O0040026.

Meyer J. W., Frank D. J., Hironaka A., Schofer E., Tuma N. B. (1997). The structuring of a world environmental regime Vol. 51 (International Organization), 623–651.

Molenaar E. J. (1998). Coastal state jurisdiction over vessel-source pollution (Hague: Kluwer Lawa International), 42.

Mondré A., Kuhn A. (2022). Authority in ocean governance architecture. Politics Governance 10 (3), 5–13. doi: 10.17645/pag.v10i3.5334

NAMR (2020) National academy of marine research 2020 annual report. Available at: https://www.namr.gov.tw/ebook/1100422/index.html.

National Council for Sustainable Development (2019) Taiwan Sustainable development policy guideline. Available at: https://nsdn.iweb6.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/1080920%E8%87%BA%E7%81%A3%E6%B0%B8%E7%BA%8C%E7%99%BC%E5%B1%95%E7%9B%AE%E6%A8%99.pdf.

NZDOC (2022) New Zealand department of conservation web site. Available at: https://www.doc.govt.nz/ (Accessed 11/01/2022).

OCA (2019a) Cetacean watching guide in Taiwan. Available at: https://www.oca.gov.tw/userfiles/A47020000A/files/6_5%E8%87%BA%E7%81%A3%E6%B5%B7%E5%9F%9F%E8%B3%9E%E9%AF%A8%E6%8C%87%E5%8D%97-%E9%9B%BB%E5%AD%90%E7%89%88.pdf.

OCA (2019b) 2019 Taiwan cetacean population survey plan. Available at: https://www.oca.gov.tw/filedownload?file=research/202002071148450.pdf&filedisplay=108%E5%B9%B4%E5%BA%A6%E5%8F%B0%E7%81%A3%E6%B5%B7%E5%9F%9F%E9%AF%A8%E8%B1%9A%E6%97%8F%E7%BE%A4%E8%AA%BF%E6%9F%A5%E8%A8%88%E7%95%AB%E6%88%90%E6%9E%9C%E5%A0%B1%E5%91%8A%E6%9B%B8.pdf&flag=doc&dataserno=202002070006.

OAC (2020) Salute to the seas- open sea area and development plan. ocean affairs council. Available at: https://english.ey.gov.tw/News3/9E5540D592A5FECD/5159650d-efd7-46ab-9714-656b50f0c39f.

OCA (2020) Ocean mambo- white dolphin topic in Taiwan waters. Available at: https://www.oac.gov.tw/filedownload?file=searesource/202101151624170.pdf&filedisplay=201906%E6%B5%B7%E6%B4%8B%E6%BC%AB%E6%B3%A2.pdf&flag=doc&dataserno=202101150012.

OCA (2022) Introduction to Taiwan marine protected areas. Available at: https://www.oca.gov.tw/ch/home.jsp?id=199&parentpath=0,5,197.

Ocean Basic Act (2019) (Taiwan). Available at: https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=D0090064.

Olsen S. B., Lowry K., Tobey J. (1999). A manual for assessing progress in coastal management (Narragansett: Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island).

Organization Act of Ocean Affairs Council, Organizations Act (2015) (Taiwan: Ocean Affairs Council). Available at: https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=D0090030.

Rees S. E., Mangi S. C., Hattam C., Gall S. C., Rodwell L. D., Peckett F. J., et al. (2015). The socio-economic effects of a marine protected area on the ecosystem service of leisure and recreation. Mar. Pol. 62, 144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.09.011

Rogers A. D., Laffoley D. (2013). Introduction to the special issue: The global state of the ocean; interactions between stresses, impacts and some potential solutions. synthesis papers from the international programme on the state of the ocean 2011 and 2012 workshops. Mar. pollut. Bull. 74 (2), 491–194. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.06.057

Selin H., Linnér Björn-Ola (2005). The quest for global sustainability: international efforts on linking environment and development (Cambridge, MA: Science, Environment and Development Group, Center for International Development, Harvard University).

Shao K.-T. (2000). “Returning marine life to a real safe home, marine protected areas - allowing marine life to have a safe home,” in Manual of the International Symposium on Planning and Promotion of Marine Protected Areas. 5–7 (Academia Sinica Institute of Zoology). https://brmas.openmuseum.tw/muse/digi_object/933a675c68fc2fc0836a161426760a6d

Shao K.-T. (2009). Marine biodiversity and fishery sustainability, Asia pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 18 (4), 528–531.

Shao K.-T. (2020) Marine protected areas–current situation and challenges in Taiwan. Available at: https://e-info.org.tw/node/223513.

Shao K.-T., Ho H.-C., Lin Y.-C., Lin P.-L., Lin H.-H. (2008). Research and status of Taiwan fishes diversity and database (Taiwan: Biodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica). Available at: http://2008checklist.biodiv.tw/disc2008/doc/Kwang-Tsao%20Shao_fishdb.pdf.

Shao K.-T., Lai K.-q. (2011). The current situation and challenges of taiwan's marine protected areas. Mar. Affaird Policy Rev. 1, 65–90. doi: 10.6546/MAPR.2011.0(0)65

Shih Y.-C. (2010). “The study of the ocean governance and environmental monitoring,” in Proceedings of the 17th Maritime Police Symposium. 77–92 (Central Police University). Available at: https://mp.cpu.edu.tw/p/412-1025-3068.php

Shih Y.-C. (2017). Coastal management and implementation in Taiwan. J. Coast. Zone Manag 19, 437. doi: 10.4172/2473-3350.1000437

Shih Y.-C. (2020). Taiwan’s progress towards becoming an ocean country. Mar. Policy 111, 10372. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103725

Sobel J. A., Dalgren C. P. (2004). Marine reserves: A guide to SCIENCE, design, and use (Island Press).

Sohn L. B. (1973). The Stockholm declaration on the human environment, 14 HARVARD j. INT’L l. 413, at 513-515. marine and coastal access act 2009 (Legislation.gov.uk).

Song R., Wu L., Geraci M., Zhong H. (2022). Maritime cooperation and ocean governance 2021: Symposium report, Marine Policy Vol. 146. 105302. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105302

Stefansson G., Rosenberg A. A. (2006). Designing marine protected areas for migrating fish stocks. J. Fish Biol. 69, 66–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8649.2006.01276.x

Thompson R. C., Moore C. J., vom Saal F. S., Swan S. H. (2009a). Plastics, the environment and human health: current consensus and future trends. Philos. Trans. R. Soc Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 364, 2153–2166. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0053

Thompson R. C., Swan S. H., Moore C. J., vom Saal F. S. (2009b). Our plastic age. Philos. Trans. R. Society 364 (1526), 1973–1976. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0054

Tseng C.-T. (2021). System and regulations of new zealand’s whale watching industry. international ocean information Vol. 11 (Ocean Affairs Council), 12–16.

Underwater Culture Heritage Preservation Act (2015) (Taiwan: Ministry of the Culture). Available at: https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=H0170102.

UNEP (2011). Strategic plan for biodiversity 2011-2020: Further information related to the technical rationale for the aichi biodiversity targets. including potential indicators and milestones (New York: United Nations Environment Programme, UNEP).

United Nations (2015) Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available at: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2017). The sustainable development goals report. Available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2017/.

Van Tatenhove J. (2008). Innovative forms of marine governance: a reflection. presentation at the symposium: on science and governance (Wageningen University).

Warner O. (2001). Marine protected areas beyond national jurisdiction- -existing legal principles and future legal frameworks. in m. haward (ed) integrated oceans management: Issues in implementing australia’s ocean policy (Hobart: cooperative research Center for Antarctica and Southern Ocean), 59.

Wetland Conservation Act (2013) (Taiwan: Construction and Planning Agency, Ministry of the Interior). Available at: https://www.cpami.gov.tw/home.html.

Wigley T. M. L., Raper S. C. B. (1992). Implication for climate and sea level of revised IPCC emissions scenarios. Nature 357, 293–300. doi: 10.1038/357293a0

Xu B., Chang Y.-C. (2017). The new development of ocean governance mechanism in Taiwan and its references for China. Ocean Coast. Manage. 136, 56–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2016.11.022

Keywords: marine policy, ocean governance, marine environment protection, Taiwan, marine affairs

Citation: Shih Y-C, Chen WC, Chen T-AP and Chang C-w (2023) The development of ocean governance for marine environment protection: Current legal system in Taiwan. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1106813. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1106813

Received: 24 November 2022; Accepted: 06 March 2023;

Published: 24 March 2023.

Edited by:

David Ong, Nottingham Trent University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Umesh P. A., Helmholtz Centre for Materials and Coastal Research (HZG), GermanyWen-Yan Chiau, National Taiwan Ocean University, Taiwan

Wen-Hong Liu, National Kaohsiung University of Science and Technology, Taiwan

Copyright © 2023 Shih, Chen, Chen and Chang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi-Che Shih, c2hpaEBncy5uY2t1LmVkdS50dw==

Yi-Che Shih

Yi-Che Shih Wei Chung Chen

Wei Chung Chen