- 1Guangxi Key Laboratory of Beibu Gulf Marine Biodiversity Conservation, College of Marine Sciences, Beibu Gulf Ocean Development Research Center, Beibu Gulf University, Qinzhou, China

- 2Guangxi Key Laboratory of Marine Environmental Science, Guangxi Academy of Marine Sciences, Guangxi Academy of Sciences, Nanning, China

- 3Beibu Gulf Marine Industry Research Institute, Fangchenggang, China

- 4Haikou Duotan Wetland Institute, Haikou, China

- 5South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, Guangzhou, China

- 6Fisheries College, Jimei University, Xiamen, China

- 7College of Fisheries and Life Science, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai, China

- 8College of Life Sciences and Oceanography, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China

- 9National Engineering Research Centre for Marine Aquaculture, Zhejiang Ocean University, Zhejiang, China

- 10Ocean College, Tangshan Normal University, Tangshan, China

Introduction: As one of the megadiverse countries, the effectiveness of wildlife protection in China is of great significance to global biodiversity conservation. With continued evolution and revisions, China’s Wildlife Protection Law has listed over 140 marine species; however, it is still inclined toward terrestrial animals.

Methods: To narrow the gap between compliance and enforcement, we collected 1,309 effective responses from various coastal cities of China through an anonymous online questionnaire survey, to investigate their exposure, understanding and attitudes toward Wildlife Protection Law for marine species (mWPL).

Results: Most respondents demonstrated an overall good understanding about the context, necessity and effectiveness of mWPL. The fisher communities were found to be more aware of the dissemination and implementation of mWPL. However, they understood less of the penal system, and exhibited negative attitudes toward the necessity and punishment of the legislation, probably due to the conflicts between resource utilizations and legislative interventions. The participants also indicated that seahorses, horseshoe crabs and corals were commonly subjected to illegal exploitations.

Discussion: While most respondents suggested greater fines, tighter laws and better public enforcement, we advocate the exploration of bottom-up options such as community engagement and environmental education to improve compliance and implementation of mWPL for the benefit of marine wildlife conservation in China.

Introduction

Biodiversity, including taxonomic diversity, phylogenetic diversity and functional diversity in a broad sense (Noss, 1990; Ricklefs and Miller, 2000; Krebs, 2014), is critical in maintaining the stability and resilience of ecosystem functions (Oliver et al., 2015; Xu Q. et al., 2021), meanwhile providing human beings with multiple ecosystem services (Barbier et al., 2011). However, global biodiversity has been reduced throughout human history (Cardinale et al., 2012). Despite the biodiversity crisis is recognized by world leaders and citizens, the international community has failed to slow the loss of the nature world, particularly when all the 20 Aichi biodiversity targets for 2020 were not fully achieved (SCBD (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity), 2020). Therefore, an enhanced understanding of the factors hindering the progress and suggesting possible solutions are required to reverse the tide of biodiversity loss.

As one of the megadiverse countries, China contains a high proportion of terrestrial and marine biodiversity hotspots (Myers et al., 2000; Schipper et al., 2008; Tittensor et al., 2010; Jenkins et al., 2013), with approximately 11% of the world’s total wildlife species, including over 2700 terrestrial vertebrate species and 28000 marine species (Jiang and Luo, 2012; Liu, 2013; Gong et al., 2020). Strengthening wildlife protection in China is thus of great significance to progress toward global biodiversity targets (Gong et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2021). Conservation of its biodiversity, however, has long faced significant obstacles. Wildlife exploitation for consumption and medicinal materials that are rooted in Chinese culture (Yu, 2010; Zhang and Yin, 2014; Fu et al., 2019) has severely impeded the progress of effective wildlife protection in China. The conflict drives continued criminal hunting and trading activities (Shao et al., 2021), especially when the punishments for illegal wildlife uses are considered insufficiently severe (Yang et al., 2020).

The Chinese government has issued relevant laws and continued evolving management strategies to protect biodiversity and threatened wildlife. Initially issued in 1989, the Wildlife Protection Law (WPL) of China has been revised five times in 2004, 2009, 2016, 2018 and 2021 (Feng et al., 2019; Lü and Chen, 2020; You, 2020). While the early versions aimed to protect species that were valuable for human utilizations (Wang et al., 2019; Xu J. et al., 2021; Whitfort, 2021), in the latter updates, the scope of protection has been broadened. After the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic and the following launch of an all-time strict ban on terrestrial wildlife consumption and trade (Huang et al., 2021b; Koh et al., 2021; Xu J. et al., 2021), the most updated WPL version was released in February 2021 (http://www.forestry.gov.cn/main/5461/20210205/122418860831352.html). The currently effective version has expanded its protection to over 140 marine species, which is about 15% of the total listed species. Many globally threatened species such as horseshoe crabs, giant clams and seahorses are now classified as China’s Class II national key protected animals. Sea turtles with higher extinction risks, including green sea turtle Chelonia mydas, hawksbill sea turtle Eretmochelys imbricata, olive ridley sea turtle Lepidochelys olivacea and the Tartaruga marina commune Caretta caretta, have been upgraded from Class II to Class I national key protected animals.

The inclination of legislative protection toward terrestrial animals, however, remains evident (Huang et al., 2021b). To fill the gap between legislative implementation and stakeholders’ perspectives to improve the effectiveness of WPL for marine species (mWPL), we investigated the perceived exposure, understanding and perspectives toward mWPL among inhabitants of the Chinese coastal cities through an anonymous online questionnaire. Popular marine taxa subject to possible illegal wildlife exploitation under the mWPL were also explored. The findings are useful to understand the way China’s wildlife protection laws and regulations are disseminated and perceived by various stakeholders, which could improve compliance and enforcement of WPL, and thereby contribute to effective marine biodiversity conservation in China.

Materials and methods

Survey method

A survey questionnaire (Supplementary Tables 1, 2) written in simplified Chinese was created using the WJX platform (https://wjx.cn/). The final version was disseminated to various stakeholders through collaborators from academic institutions, non-governmental organizations and governmental departments from July 2019 to January 2020. Prior to the start of answering questions, the participants were alerted of the objectives of the study, and informed that the data collection would be anonymous. The respondents were also asked not to provide their names and full addresses in the questionnaire to ensure anonymity.

To improve the validity of the data, responses were included in the analysis only if the participant grew up locally or have stayed for at least two years in any coastal cities of China, except for Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan regions. To lower the chances of survey fraud, all collected data were screened manually to eliminate those who disengaged or responded to the questions mindlessly, for example selecting the same options for most questions. However, they were allowed to skip unwanted questions to avoid providing misleading information. A response was also considered ineffective given that more than half of the questions were left unanswered.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire was divided into five parts, including (1) sociodemographic factors of respondents, (2) exposure to mWPL, (3) understanding of mWPL, (4) perspective toward mWPL, and (5) possible illegal marine wildlife exploitation. Both descriptive and multiple-choice questions were designed to identify individual and situational determinants in shaping the attitudes and behavioral patterns of the coastal community. Questions regarding the sources as well as frequencies of media reporting (e.g., social media feeds, newspapers, television and radio broadcasts) and enforcement activity sightings were asked to understand the public exposures to mWPL (Supplementary Table 1). To test their understandings of mWPL, the participants were allowed to identify the examples of illegality, the appropriate office/departments to report illegality and the possible penalty. For the perspective part, the respondents were asked about their opinions on the necessity and effectiveness of legislation, the extent of themselves or others obeying the law, their perspectives on imposed legal punishment in a previous case, and their willingness to report any possible illegal act and the reasons. The last part of the questionnaire attempted to explore possible illegal marine wildlife exploitation by themselves and their families/peers, and the purpose of use for the animals. Prior to submissions, the respondents were reminded that the collected data would be anonymous and used only for research purposes, and they could leave the last part questions unanswered.

Likert scales were used to calculate the scores of exposure and perspective dimensions of respondents (Supplementary Table 2). For the exposure to mWPL, each response of “often”, “seldom”, “once” and “never” was provided scores of 3, 2, 1 and 0, respectively. For the perspective toward mWPL, scores of 2, 1, 0, -1 and -2 were allocated for options “much agreed”, “agreed”, “no idea”, “disagreed” and “much disagreed”, respectively. The three questions regarding the understanding of mWPL were calculated based on the percentage of correctness, i.e., the number of correct option(s) divided by the total number of options. A correct answer means that a respondent ticked a correct option or unticked a wrong option.

Statistical analysis

The differences in score and percentage of correctness among various occupations were examined by Kruskal-Wallis, followed by Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner post hoc test because the data did not meet the requirement of normal distribution or equal variance. To check whether the response was a result of blind-choosing, one-sample t-test was applied to test the deviation of overall scoring from a given mean value of the score. The deviation of the percentage of correctness from the percentage value of blind-choosing, which we defined as when a respondent ticked all the options for a given question, was also tested by one-sample t-test. Two-sample t-test was used to test the difference in the mean score of the question “extent of obeying the law” between oneself and others. All statistical analyses were performed in STSTAT 13.

Results

Sociodemographic information of the respondents

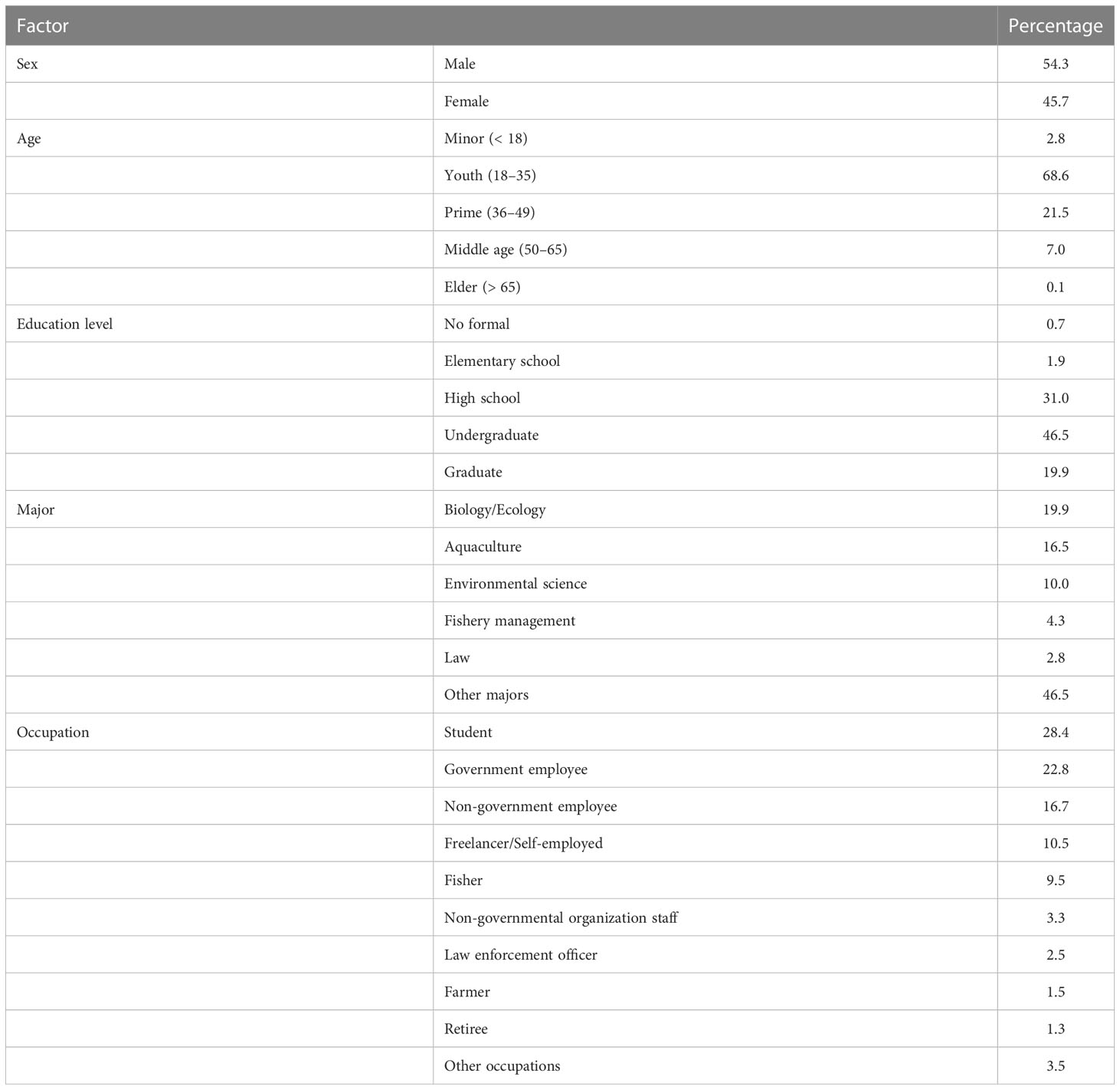

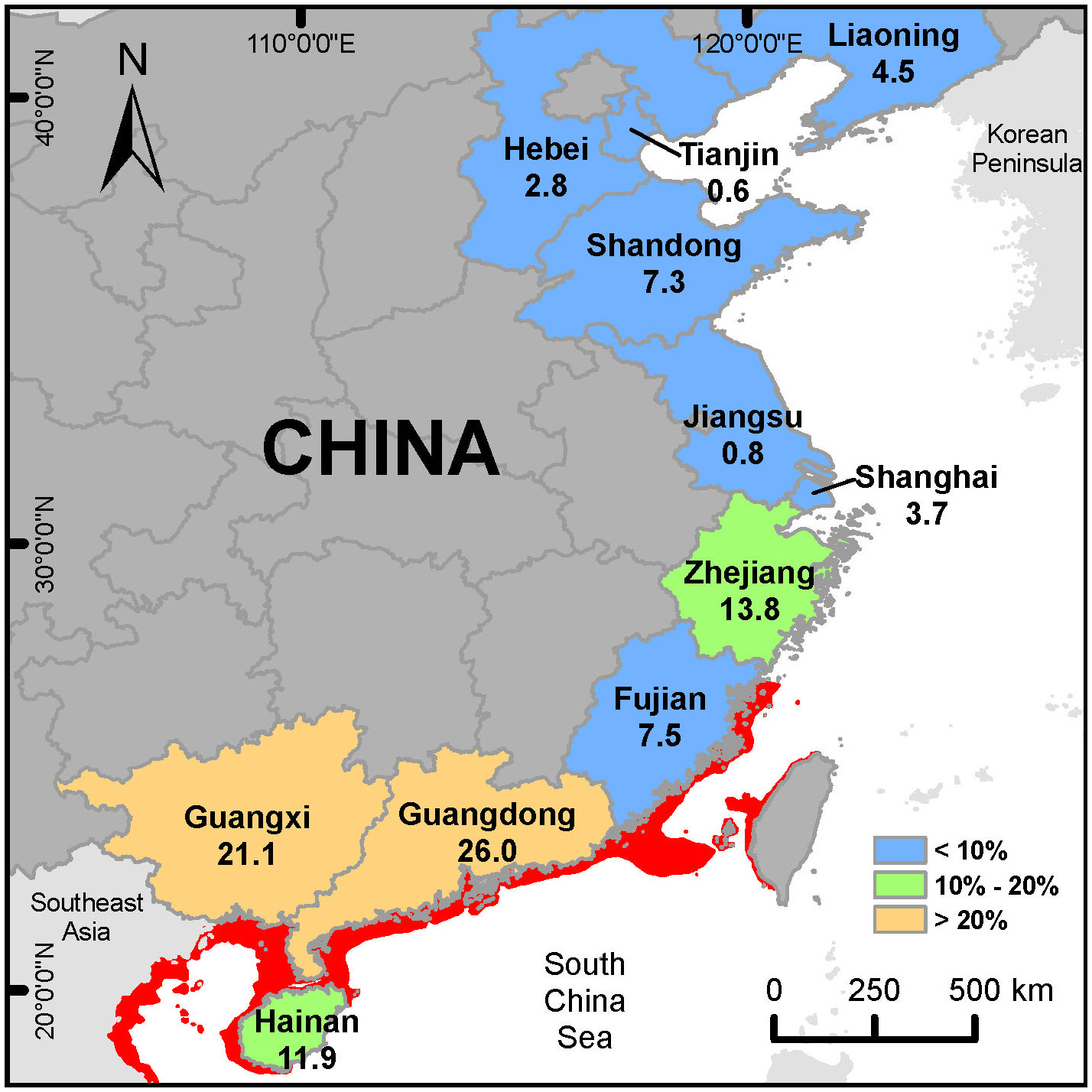

The survey received 1,309 effective responses. A higher proportion of respondents were originated from Southern China (59%), followed by Eastern China (26%) and Northern China (15%, Figure 1). The male-to-female ratio of respondents was 1.2. Most participants (90%) were at their age of youth or prime (18–49 years old), with the education levels of high school, undergraduate or graduate (97%, Table 1). They were mostly students (28%), government employees (23%), non-government employees (17%) and freelancer/self-employed individuals (11%), with certain involvements (17%) of fishers and farmers, law enforcement officers, and non-governmental organization staff (Table 1).

Figure 1 Geographic distribution of respondents (%) from different coastal provinces/regions/municipalities of China (except Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan regions). The red area shows the distribution range of threatened seahorses and horseshoe crabs, which is consistent with the most frequently reported taxa by the respondents subjected to possible illegal marine wildlife exploitation activity. Geographic range data of the taxa are obtained from the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Version 2021-3.

Perceived exposure to wildlife protection law for marine species

Media reports (52%) and official documents (26%) were claimed to be the primary sources of respondents to receive information relevant to mWPL (Figure 2). The number of sources utilized was 1.5 ± 0.8 (mean ± standard error), which was significantly higher than no source (t = 68.6, p < 0.001) and single source (t = 24.0, p < 0.001). The number of sources was significantly different among occupations (chi-square = 32.2, p < 0.001); however, the pairwise comparisons between occupation pairs were found insignificant (p > 0.05).

Figure 2 Perceived primary sources for acquiring information about the implementation of Wildlife Protection Law for marine species. Both media and official documents were reported to be the main sources.

Nearly half of total respondents (48%) claimed that mWPL information was seldom delivered through local news reporting (Table 2). The difference in the perceived frequency score of news reporting among occupations was significant (chi-square = 72.4, p < 0.001). Post hoc tests indicated that fishers reported significantly higher frequencies of local news reporting on mWPL than other occupations. Similarly, 46% of the respondents never witnessed any enforcement activity (Table 2), while fishers claimed significantly higher numbers of sightings than other occupations (chi-square = 147.1, p < 0.001).

Table 2 Percentage distribution of responses for exposure frequency to the Wildlife Protection Law for marine species.

Understanding of wildlife protection law for marine species

Most participants could respond correctly when they were asked to identify the acts of illegality (73%), the appropriate office/departments to report illegality (64%) and the possible penalty of illegality (70%) in accordance with mWPL. The percentages of correctness for these questions were significantly higher than those of blind choosing (p < 0.001). While occupation was found to significantly influence the scores of correctness for all these questions (chi-squares = 18.0, 33.8 and 26.0, respectively; p < 0.05), post hoc tests only detected the statistically lower scores on the penalty question by fishers than other occupations.

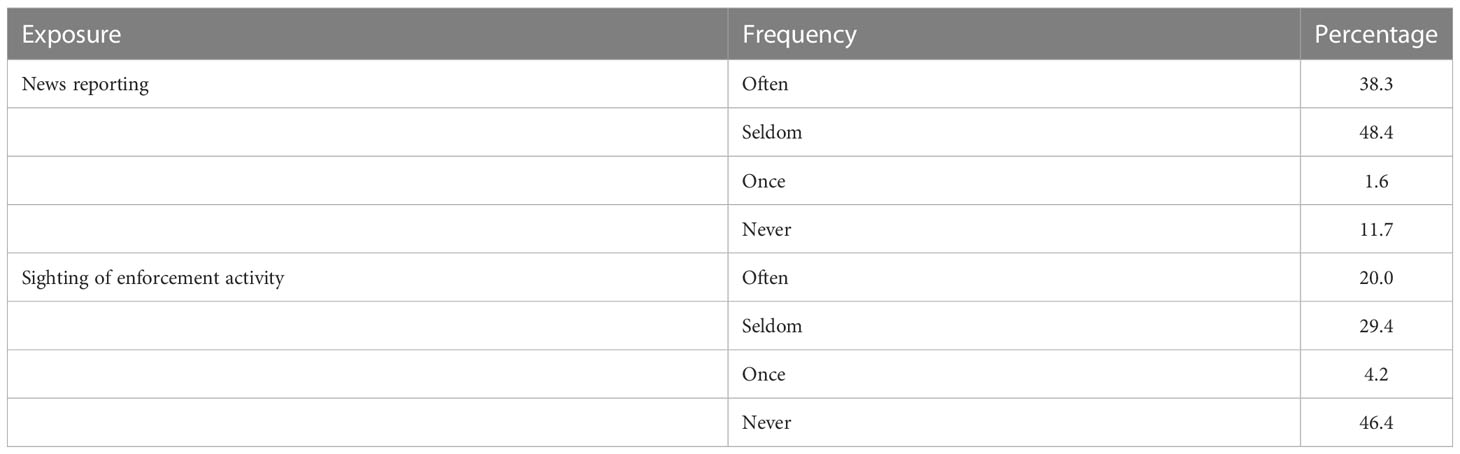

Perspectives toward wildlife protection law for marine species

Almost all respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the necessity (97%) and effectiveness of mWPL (85%, Table 3). While the difference in score of effectiveness was statistically similar among occupations, fishers considered mWPL to be less necessary than other occupations (chi-square = 69.2, p < 0.001). As to the opinion on a case of legal penalty, a high proportion of respondents (80%) thought the level of punishment was appropriate (Table 3). Nevertheless, fishers expressed a significantly lower agreement with the imposed penalty (chi-square = 57.2, p < 0.001).

Table 3 Percentage distribution of responses regarding perspectives toward Wildlife Protection Law for marine species (mWPL).

Most respondents agreed with the statement that themselves (88%) or their families and peers (72%) are obedient to mWPL (Table 3). The obedient scores were statistically lower in non-government employees and fishers when the statement was referred to themselves and others, respectively (chi-squares = 23.2 and 48.7, respectively; p < 0.01).

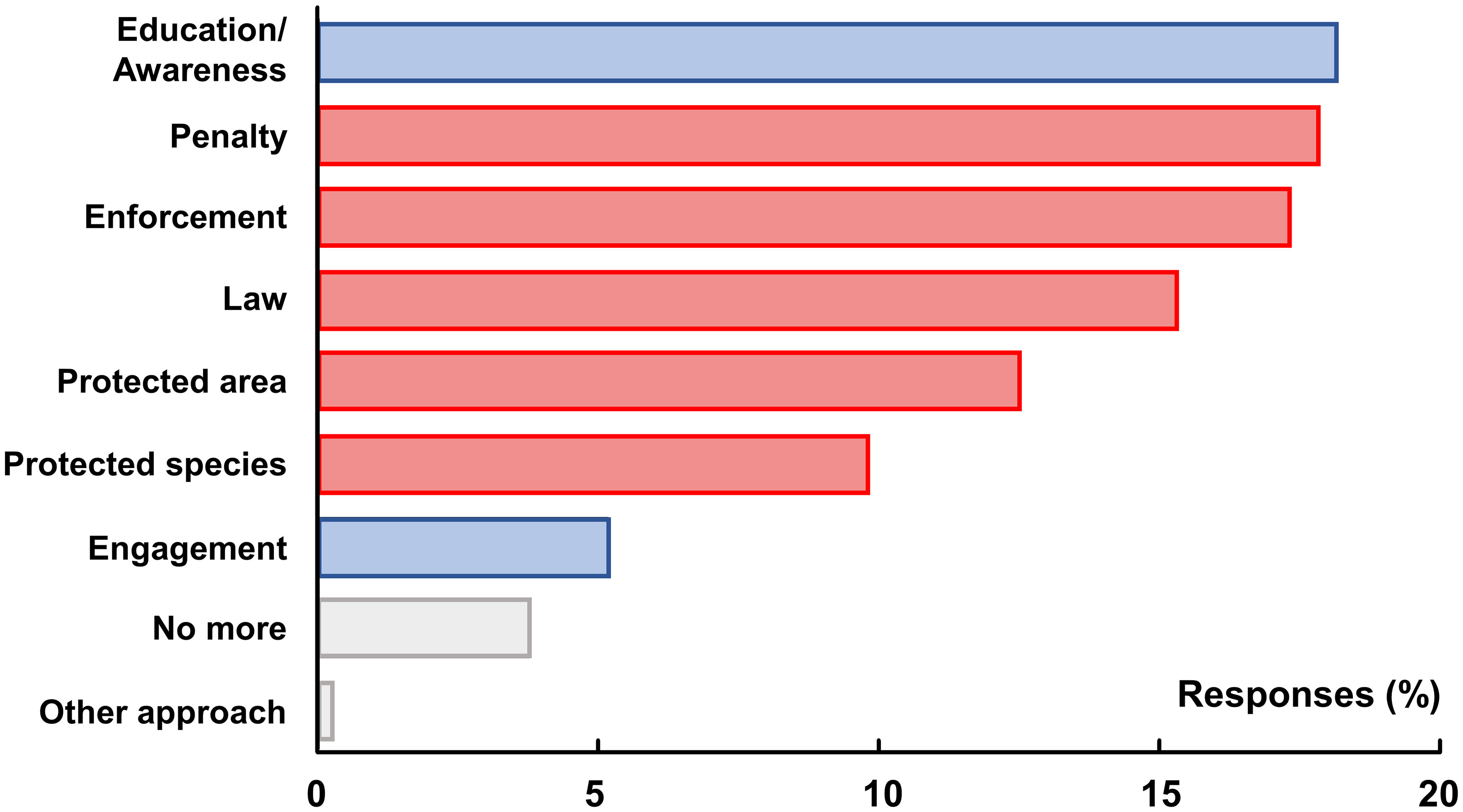

Over half (52%) of the total respondents thought that the stricter enforcement of mWPL had no impact on themselves, while 28% of them perceived a possible impact on their jobs and incomes (Table 3). The participants claimed that they would blow the whistle when they encountered any possible acts of illegality anonymously (47%) or with their names stated (34%; Table 3). Those who refused (n = 68) claimed that they did not want to be in trouble or would not receive feedback from the relevant authorities (32% for both reasons; Table 3). Most respondents (73%) proposed top-down approaches to improve marine wildlife protection in China, which included strengthening law enforcement and punishment, issuing new or more laws and regulations, establishing more protected areas, and including more species on the protection list (Figure 3). Others suggested bottom-up options to improve public education and awareness programs (18%) and local community engagement (5%).

Figure 3 Perceived top-down (red bars) and bottom-up (blue bars) approaches to improve marine wildlife protection. Most respondents preferred top-down approaches over bottom-up options.

Illegal marine wildlife exploitation under wildlife protection law

There were 19% (n = 249) and 34% (n = 448) of participants who claimed that themselves and their families/peers, respectively, were previously involved in possible illegal marine wildlife exploitation activities. Seahorses, horseshoe crabs and corals were the most frequently mentioned taxa, which accounted for over 50% of the responses (Table 4). The animals were primarily used for food (34%), traditional Chinese medicine (23–28%) and pet/ornament (22%, Table 4).

Table 4 Percentage distribution of (A) reported taxa and (B) purpose of use for possible illegal marine wildlife exploitation activity under the Wildlife Protection Law for marine species.

Discussion

Despite the fact that an enhanced understanding of public perspectives toward wildlife law implementation is demanding, a national-wide survey covering a broad range of stakeholders can be labor- and time-intensive. This study preferably utilized online tools to prioritize respondent anonymity, especially when the present study could be sensitive to particular populations. Meanwhile, the survey questions were carefully designed (Supplementary Tables 1, 2) so that manual filtering of irrelevant or disengaged participants was enabled during data analysis to improve data representativeness and accuracy. The current state of responses were mainly obtained from students and government/non-government staff with certain involvement of fishers/farmers and law enforcement officers inhabiting the coastal cities in Southern and Eastern China. The eastern and southeastern coastal water of China is a representative marine biodiversity hotzone (Tittensor et al., 2010), and therefore the results should benefit the future development of effective marine wildlife law and accomplishment of global biodiversity targets.

Leveraging mass media is important in strengthening public awareness and support for wildlife protection. Television news, newspaper stories and the recent booming of social media newsletters can have powerful impacts on public understanding and perspectives toward mWPL, which in turn, influence the levels of concern and engagement in conservation policies and marine wildlife management (Hart et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2018). Our results suggest that most respondents acquired relevant information of mWPL through multiple sources, mainly mass media and official documents, and demonstrated an overall good understanding of the mWPL context. The successful penetration of mWPL may be associated with the rapid development of social media platforms as well as the wide coverage of smartphones and internet networks in China. The fisher communities that have the higher encounter rate of on-site enforcement activities, as indicated in the present study, were more sensitive to media reporting of mWPL. However, they understood less about the penal system, and exhibited negative attitudes toward the necessity and penal system of the legislation. These findings corroborate a previous study that the wider coverage of social media articles not necessarily promoted public perception of wildlife conservation (Wu et al., 2018). Previous studies found that media portrayal of good-looking animals or simplistic descriptions with polarizing language, instead of knowledge about the conservation plight of threatened species can result in public misunderstanding of conservation efforts by the government and scientific communities (Nekaris et al., 2013; Geijer, 2014). The poor correlations between media exposure and conservation attitudes in fisher communities were probably due to the conflicts between resource utilization (livelihood) and legislative interventions (Shi et al., 2020; Cusack et al., 2021) or lower sensitivities toward the actual consequences of illegality.

In contrast to the fisher communities, other stakeholder groups in this study exhibited more positive attitudes toward the necessity and effectiveness of mWPL. They also claimed that themselves and their families/peers are always obedient to mWPL, and would blow the whistle on possible illegal acts. Similar attitude patterns were also documented in another online questionnaire survey regarding the strict ban on terrestrial wildlife consumption and trade during the COVID-19 pandemic in China (Shi et al., 2020). The positive perspectives and stated compliance should be interpreted with great caution since they could be over-reported to “save face” under specific cultural contexts (Pollnac et al., 2010). The findings could also be a consequence of attitude-behavior gap. For example, nearly 20% of the respondents in this study reported their possible illegal exploitation of seahorses, horseshoe crabs and corals, despite the fact that almost all of them (97%) admitted the necessity and effectiveness of mWPL. The similar phenomenon was also reported in previous investigations that a high proportion of respondents expressed their supports toward wildlife protection meanwhile recently consumed wild animals (Zhang et al., 2008; Fu et al., 2019).

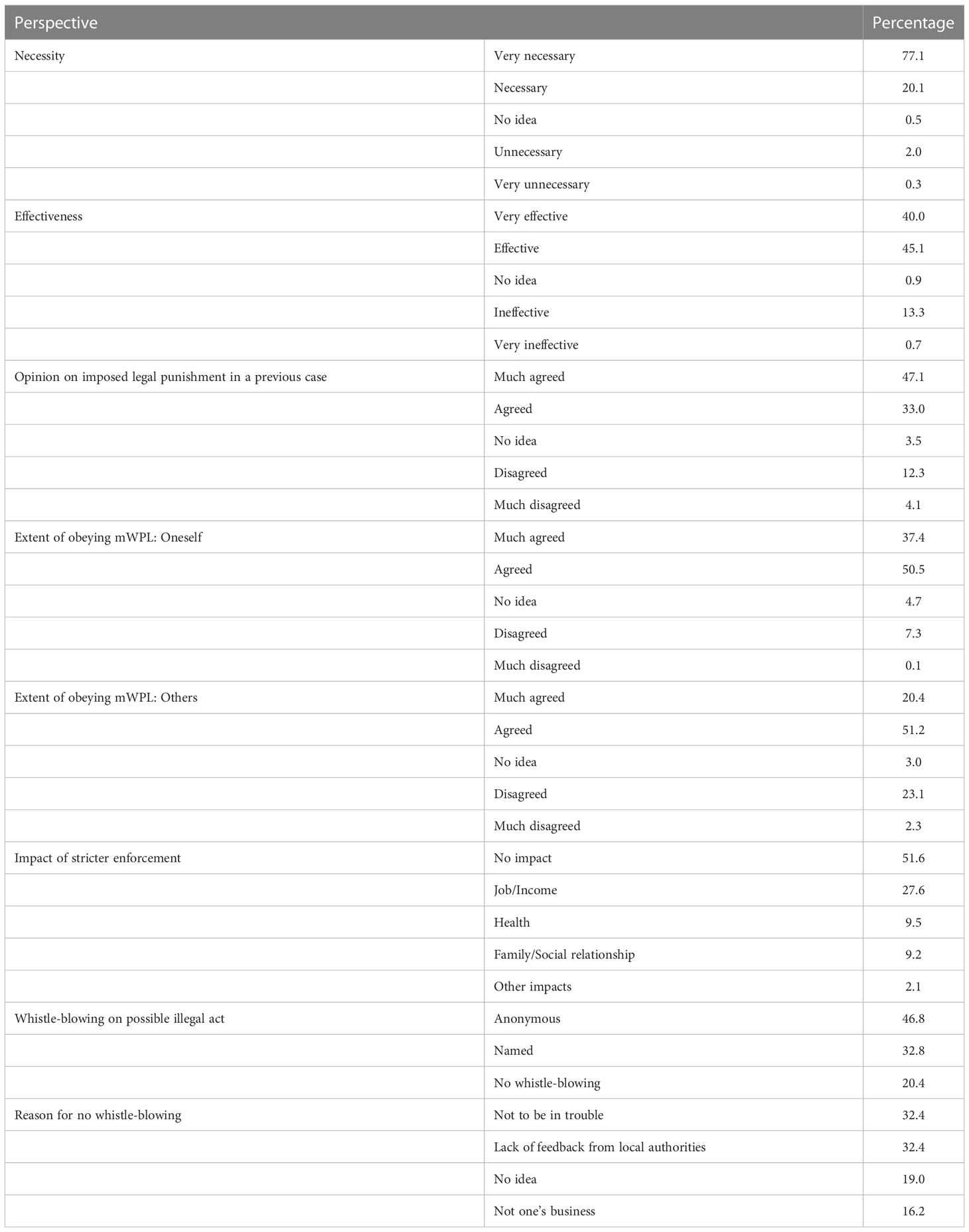

To close the attitude-behavior gap, the respondents suggested introducing greater fines, tighter laws, better public enforcement and other top-down measures. Top-down approaches, which are based solely on legislation and enforced by responsible administrations, are an indivisible part of conservation management in China (Liu et al., 2003), where the coastal areas are highly populated (Neumann et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the efficiency of wildlife legislation remains mostly unknown and questionable. Leader-Williams and Milner-Gulland (1993) revealed that improved detection rates rather than imposing heavier penalties can halt wildlife crimes. Similarly, the protection of critically endangered wolf population in Sierra Morena failed under comprehensive but improperly enforced wildlife laws (López-Bao et al., 2015). Wildlife law enforcement can be further complicated by social interactions. Hu et al. (2022) suggested that intensive law operations can lead to pro-social engagement, as indicated by the increased whistle-blowing activities on illegal wildlife trade after the Chinese government has launched the project of “ecological civilization” since 2012. However, wildlife laws that conflict with social norms could result in reduced whistle-blowing and increased law-breakers (Acemoglu and Jackson, 2017). The conflict intensity can be escalated from latent disagreement to violence, and long-lasting conflicts would have higher chances to involve stakeholder actions (Cusack et al., 2021). The combination of ineffective enforcement and social factors, accompanied by overlapped management and responsibility among different administrative departments (Zhang et al., 2017; Gong et al., 2020; Lü and Chen, 2020), differentiated jurisdiction system between terrestrial and aquatic wildlife (Gong et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2021a), and inconsistent goals among different administrative levels (national/provincial/local), all pose huge challenges to the effective implementation of mWPL in China (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Conceptual framework for achieving an effective Wildlife Protection Law for marine species in China.

In light of more restrictions and regulations on China’s wildlife trade in post COVID-19 pandemic period (Xu J. et al., 2021), we advocate the exploration of bottom-up options in China to alleviate the stakeholder conflicts. Protection of threatened marine species and biodiversity requires long-term understanding, support and participation from stakeholders. A considerable proportion of the world’s marine biodiversity and fishery resources is being led and managed by self-organized indigenous people and local communities (Freed et al., 2016; Metcalfe et al., 2017; Pakiding et al., 2020). Community-based enforcement initiatives, which are driven intrinsically by the community responsibility to develop local rules and regulations, were demonstrated to have higher compliance and more effective resource management (Crawford et al., 2010). Previous studies also indicated that local villagers can become motivated to protect their natural environments given that their participation in conservation management was allowed (Plummer and Taylor, 2004; Menzies, 2007). Therefore, the engagement and empowerment of the local communities in collecting fishery baselines, monitoring destructive exploitation practices and maintaining dialogues and support from local authorities, for instances, could alleviate their heavy reliance on the benefits derived from wildlife exploitation and unsustainable fisheries. Since there is no one-size-fits-all approach in biodiversity conservation, environmental education with localized knowledge, values and needs is critical in the decision-making of local environmental issues under complex social-ecological systems (Brias-Guinart et al., 2022; Figure 4). The involvement of third-party actors, including academic institutions and non-governmental organizations, can also benefit the local community by providing environmental education, enhancing conservation awareness, building capacity and reinforcing communication among stakeholders (Freed et al., 2016; Kwan et al., 2017; Figure 4). Further investigations are needed to understand how mWPL compliance can be interlinked with individual and societal determinants.

Conclusion

Our questionnaire survey provided valuable insights from various stakeholder groups to improve compliance and implementation of wildlife laws to protect threatened marine species and biodiversity in China. Fisher communities, the principal stakeholders who actively participated in marine resource acquisition and use, perceived the higher frequencies of local news reporting and enforcement activity sightings relevant to mWPL. However, more exposure to mWPL, as noted among fisher communities, seemed not to result in enhanced understanding and more positive attitudes toward the wildlife law. Our findings demonstrated that the fishers (1) understood less about the penal system, (2) exhibited negative attitudes toward the necessity and penal system of the legislation, and (3) thought their families and peers had higher degree of compliance with wildlife laws than themselves. Seahorses, horseshoe crabs and corals, as indicated by the survey participants, were more vulnerable to illegal exploitation. While most respondents suggested increasing severity of punishment and other top-down approaches, the increasingly intensified conflicts between legislative interventions and social norms of wildlife exploitation in China may result in lower public compliance and support toward mWPL. We advocate the exploration of bottom-up measures, in supplement to wildlife law enforcement framework, to promote more effective marine wildlife conservation in China. Implementation of more community empowerment and environmental education programs by building capacity, reshaping motivation and providing opportunity to engage in wildlife conservation management was worth attempted.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

KYK and RC conceptualized the study framework and prepared the original draft. KYK and C-CW acquired funding and supervised the study. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (32060129), Basic Research Fund of Guangxi Academy of Sciences (2020YBJ706), Guangxi Science and Technology Base and Talents Special Project (2021AC19355), Marine Science Program for Guangxi First-Class Discipline, Beibu Gulf University (DRA002, TRA001), and Beibu Gulf Ocean Development Research Center under Key Research Base of Humanities and Social Sciences in Guangxi Universities.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2023.1055634/full#supplementary-material

References

Acemoglu D., Jackson M. P. (2017). Social norms and the enforcement of laws. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 15, 245–295. doi: 10.1093/jeea/jvw006

Barbier E. B., Hacker S. D., Kennedy C., Koch E. W., Stier A. C., Silliman B. R. (2011). The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecol. Monogr. 81, 169–193. doi: 10.1890/10-1510.1

Brias-Guinart A., Korhonen-Kurki K., Cabeza M. (2022). Typifying conservation practitioners' views on the role of education. Conserv. Biol. 36, e13893. doi: 10.1111/cobi.13893

Cardinale B. J., Duffy J. E., Gonzalez A., Hooper D. U., Perrings C., Venail P., et al. (2012). Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 486, 59–67. doi: 10.1038/nature11148

Crawford B. R., Siahainenia A., Rotinsulu C., Sukmara A. (2010). Compliance and enforcement of community-based coastal resource management regulations in north sulawesi, Indonesia. Coast. Manage 32, 39–50. doi: 10.1080/08920750490247481

Cusack J. J., Bradfer-Lawrence T., Baynham-Herd Z., Tickell S. C., Hegre I. D. H., Zárate L. M., et al. (2021). Measuring the intensity of conflicts in conservation. Conserv. Lett. 14, e12783. doi: 10.1111/conl.12783

Feng L., Liao W., Hu J. (2019). Towards a more sustainable human-animal relationship: the legal protection of wildlife in China. Sustainability 11, 3112. doi: 10.3390/su11113112

Freed S., Dujon V., Granek E. F., Mouhhidine J. (2016). Enhancing small-scale fisheries management through community engagement and multi-community partnerships: Comoros case study. Mar. Policy 63, 81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.10.004

Fu Y., Huang S., Wu Z., Wang C.-C., Su M., Wang X., et al. (2019). Socio-demographic drivers and public perceptions of consumption and conservation of Asian horseshoe crabs in northern beibu gulf, China. Aquat. Conserv. 29, 1268–1277. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3125

Geijer A. (2014). The social construction of the wolf: A case study of news media’s role in sustainability wildlife conservation in regards to the wolf in Sweden (Sweden: Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies).

Gong S., Wu J., Gao Y., Fong J. J., Parham J. F., Shi H. (2020). Integrating and updating wildlife conservation in China. Curr. Biol. 30, R915–R919. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.080

Hart P. S., Nisbet E. C., Shanahan J. E. (2011). Environmental values and the social amplification of risk: an examination of how environmental values and media use influence predispositions for public engagement in wildlife management decision making. Soc Nat. Resour. 24, 276–291. doi: 10.1080/08941920802676464

Huang G., Ping X., Xu W., Hu Y., Chang J., Swaisgood R. R., et al. (2021a). Wildlife conservation and management in China: achievements, challenges and perspectives. Natl. Sci. Rev. 8, nwab042. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwab042

Huang Q., Wang F., Yang H., Valitutto M., Songer M. (2021b). Will the COVID-19 outbreak be a turning point for china's wildlife protection: new developments and challenges of wildlife conservation in China. Biol. Conserv. 254, 108937. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108937

Hu S., Cheng Y., Pan R., Zou F., Lee T. M. (2022). Understanding the social impacts of enforcement activities on illegal wildlife trade in China. Ambio 51, 1643–1657. doi: 10.1007/s13280-021-01686-9

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) (2021) The IUCN red list of threatened species, version 2021-3. Available at: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (Accessed 15, 2022).

Jenkins C. N., Pimm S. L., Joppa L. N. (2013). Global patterns of terrestrial vertebrate diversity and conservation. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E2602–E2610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130225111

Jiang Z. G., Luo Z. H. (2012). Assessing species endangerment status: progress in research and an example from China. Biodivers. Sci. 20, 612–622. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1003.2012.11145

Koh L. P., Li Y., Lee J. S. H. (2021). The value of china's ban on wildlife trade and consumption. Nat. Sustain 4, 2–4. doi: 10.1038/s41893-020-00677-0

Krebs C. J. (2014). “Community structure in space: biodiversity,” in Ecology: The experimental analysis of distribution and abundance. Ed. Krebs C. J. (London: Pearson Education Limited), 363–387.

Kwan B. K. Y., Cheung J. H., Law A. C., Cheung S. G., Shin P. K. S. (2017). Conservation education program for threatened Asian horseshoe crabs: A step towards reducing community apathy to environmental conservation. J. Nat. Conserv. 35, 53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2016.12.002

Leader-Williams N., Milner-Gulland E. J. (1993). Policies for the enforcement of wildlife laws: The balance between detection and penalties in Luangwa Valley, Zambia. Conserv. Biol. 7, 611–617. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1993.07030611.x

Liu J. Y. (2013). Status of marine biodiversity of the China seas. PloS One 8, e50719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050719

Liu J., Ouyang Z., Pimm S. L., Raven P. H., Wang X., Miao H., et al. (2003). Protecting china's biodiversity. Science 300, 1240–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.1078868

López-Bao J. V., Blanco J. C., Rodríguez A., Godinho R., Sazatornil V., Alvares F., et al. (2015). Toothless wildlife protection laws. Biodivers. Conserv. 24, 2105–2108. doi: 10.1007/s10531-015-0914-8

Lü Z., Chen Z. (2020). Revision of the law of the people's republic of China on the protection of wildlife: background, issues and suggestions. Biodivers. Sci. 28, 550–557. doi: 10.17520/biods.2020120

Ma T., Hu Y., Wang M., Yu L., Wei F. (2021). Unity of nature and man: a new vision and conceptual framework for post-2020 strategic plan for biodiversity. Natl. Sci. Rev. 8, nwaa265. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa265

Menzies N. (2007). Our forest, your ecosystem, their timber. communities, conservation, and the state in community-based forest management (New York: Columbia University Press).

Metcalfe K., Collins T., Abernethy K. E., Boumba R., Dengui J. C., Miyalou R., et al. (2017). Addressing uncertainty in marine resource management: combining community engagement and tracking technology to characterize human behavior. Conserv. Lett. 10, 460–469. doi: 10.1111/conl.12293

Myers N., Mittermeier R. A., Mittermeier C. G., da Fonseca G. A. B., Kent J. (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403, 853–858. doi: 10.1038/35002501

Nekaris B. K. A. I., Campbell N., Coggins T. G., Rode E. J., Nijman V. (2013). Tickled to death: analysing public perceptions of ‘cute’ videos of threatened species (slow lorises–nycticebus spp.) on web 2.0 sites. PloS One 8, e69215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069215

Neumann B., Vafeidis A. T., Zimmermann J., Nicholls R. J. (2015). Future coastal population growth and exposure to sea-level rise and coastal flooding - a global assessment. PloS One 10, e0131375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118571

Noss R. F. (1990). Indicators for monitoring biodiversity: a hierarchical approach. Conserv. Biol. 4, 355–364. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2385928 doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.1990.tb00309.x

Oliver T. H., Heard M. S., Isaac N. J. B., Roy D. B., Procter D., Eigenbrod F., et al. (2015). Biodiversity and resilience of ecosystem functions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 30, 673–684. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2015.08.009

Pakiding F., Zohar K., Allo A. Y., Keroman S., Lontoh D., Dutton P. H., et al. (2020). Community engagement: an integral component of a multifaceted conservation approach for the transboundary western pacific leatherback. Front. Mar. Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.549570

Plummer J., Taylor J. (2004). Community participation in china. issues and processes for capacity building (London: Earthscan).

Pollnac R., Christie P., Cinner J. E., Dalton T., Daw T. M., Forrester G. E., et al. (2010). Marine reserves as linked social-ecological systems. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 18262–18265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908266107

Ricklefs R. E., Miller G. L. (2000). “Biodiversity,” in Ecology. Eds. Ricklefs R. E., Miller G. L. (New York: W. H. Freeman and Company), 588–618.

SCBD (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity) (2020) Global biodiversity outlook 5. Available at: https://www.cbd.int/gbo5 (Accessed 19, 2020).

Schipper J., Chanson J. S., Chiozza F., Cox N. A., Hoffmann V., Katariya J., et al. (2008). The status of the world's land and marine mammals: diversity, threat, and knowledge. Science 322, 225–230. doi: 10.1126/science.1165115

Shao M.-L., Newman C., Buesching C. D., Macdonald D. W., Zhou Z.-M. (2021). Understanding wildlife crime in China: socio-demographic profiling and motivation of offenders. PloS One 16, e0246081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246081

Shi X., Zhang X., Xiao L., Li B. V., Liu J., Yang F., et al. (2020). Public perception of wildlife consumption and trade during the COVID-19 outbreak. Biodivers. Sci. 28, 630–643. doi: 10.17520/biods.2020134

Tittensor D. P., Mora C., Jetz W., Lotze H. K., Ricard D., Berghe E. V., et al. (2010). Global patterns and predictors of marine biodiversity across taxa. Nature 466, 1098–1101. doi: 10.1038/nature09329

Wang W., Yang L., Wronski T., Chen S., Hu Y., Huang S. (2019). Captive breeding of wildlife resources-china's revised supply-side approach to conservation. Wildlife Soc B. 43, 425–435. doi: 10.1002/wsb.988

Whitfort A. (2021). COVID-19 and wildlife farming in China: legislating to protect wild animal health and welfare in the wake of a global pandemic. J. Environ. Law 33, 57–84. doi: 10.1093/jel/eqaa030

Wu Y., Xie L., Huang S.-L., Li P., Yuan Z., Liu W. (2018). Using social media to strengthen public awareness of wildlife conservation. Ocean Coast. Manage. 153, 76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.12.010

Xu J., Mei F., Lu C. (2021). COVID-19, a critical juncture in china's wildlife protection? Hist. Phil. Life Sci. 43, 46. doi: 10.1007/s40656-021-00406-6

Xu Q., Yang X., Yan Y., Wang S., Loreau M., Jiang L. (2021). Consistently positive effect of species diversity on ecosystem, but not population, temporal stability. Ecol. Lett. 24, 2256–2266. doi: 10.1111/ele.13777

Yang N., Liu P., Li W., Zhang L. (2020). Permanently ban wildlife consumption. Science 367, 1434. doi: 10.1126/science.abb1938

You M. (2020). Changes of china's regulatory regime on commercial artificial breeding of terrestrial wildlife in time of COVID-19 outbreak and impacts on the future. Biol. Conserv. 250, 108756. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108756

Yu X. (2010). Biodiversity conservation in China: barriers and future actions. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 67, 117–126. doi: 10.1080/00207231003683457

Zhang L., Hua N., Sun S. (2008). Wildlife trade, consumption and conservation awareness in southwest China. Biodivers. Conserv. 17, 1493–1516. doi: 10.1007/s10531-008-9358-8

Zhang L., Luo Z., Mallon D., Li C., Jiang Z. (2017). Biodiversity conservation status in china's growing protected areas. Biol. Conserv. 210, 89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.005

Keywords: biodiversity conservation, biological resources, bottom-up approach, fisher, legislative intervention

Citation: Kwan KY, Chen R, Wang C-C, Lin S, Wu L, Xie X, Weng Z, Hu M, Zhou H, Wu Z, Fu Y, Zhen W, Yang X and Wen Y (2023) Towards effective wildlife protection law for marine species in China: A stakeholders’ perspective. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1055634. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1055634

Received: 28 September 2022; Accepted: 10 February 2023;

Published: 20 February 2023.

Edited by:

Hui Zhang, Institute of Oceanology (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Athanasios Mogias, Democritus University of Thrace, GreeceLusita Meilana, Xiamen University, China

Copyright © 2023 Kwan, Chen, Wang, Lin, Wu, Xie, Weng, Hu, Zhou, Wu, Fu, Zhen, Yang and Wen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chun-Chieh Wang, chunchiehwang@gxas.cn

†These authors share first authorship

Kit Yue Kwan

Kit Yue Kwan